1. Introduction

Textile printing, an ancient technique, traditionally uses thick pastes of dyes or pigments to create patterns on fabrics. Among recent innovations, digital textile printing stands out for its high precision, excellent print fastness, and ability to reproduce a vast range of colours [

1,

2,

3]. However, conventional textile printing is associated with high consumption of chemicals such as dyes, binders, solvents, and surfactants, many of which are considered environmentally hazardous. Additionally, traditional processes require substantial water and energy inputs, generating large volumes of effluents loaded with harmful substances [

4]. Digital textile printing has emerged as a more sustainable solution, integrating software, advanced hardware, and optimized treatments to enable high-quality, customized production with reduced environmental impacts [

1,

4,

5,

6].

Water-based inks are gaining attention due to their eco-friendly profile. These inks are less toxic, reduce atmospheric pollution through lower volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions, pose fewer fire risks, and simplify cleaning operations [

4,

7]. Within this category, pigment-based inkjet inks are especially promising, offering good stability and improved fastness properties, such as wash and light fastness [

1,

5].

Pigments, unlike dyes, are insoluble molecules that do not form chemical bonds with textile fibres, and they are deposited on the fabric surface. Consequently, the success of pigment ink formulations relies not only on the pigment itself but also on the performance of various auxiliary compounds. These include pH adjusters, humectants, polymeric binders, defoamers, surfactants, biocides, and rheology modifiers, all of which influence ink stability, application, and print quality. Although synthetic pigments currently dominate the market due to their reproducibility, affordability, and wide colour range, concerns related to their environmental footprint are increasingly being raised. The production of synthetic dyes and pigments often involves harsh chemicals, high temperatures, and non-renewable resources such as petroleum, raising issues related to waste generation, energy consumption, and toxicity [

5,

8].

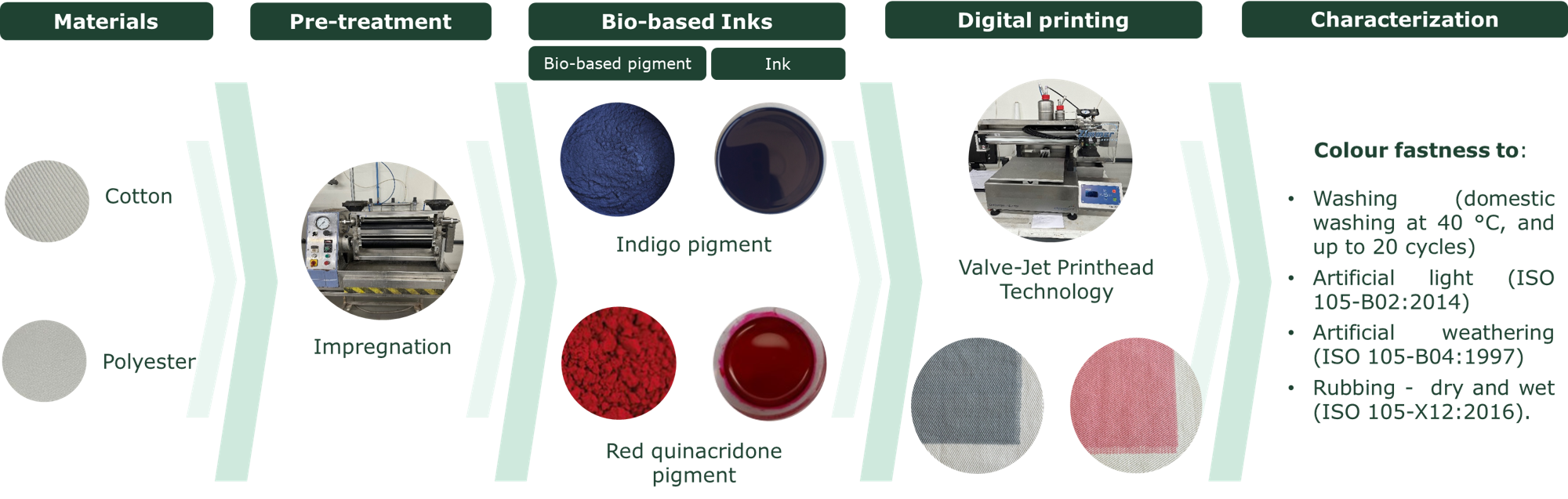

To address these concerns, there is growing interest in bio-based alternatives that align with circular economy principles and reduce environmental burdens. This study focuses on the development and evaluation of water-based pigment inks formulated with bio-based pigments. By assessing parameters such as physical properties, print quality, and colour fastness properties, the study aims to contribute to the advancement of greener digital textile printing technologies.

2. Materials and Methods

Materials

The textiles used were a cotton-based (99% cotton, 1% elastane, 370 g/m2, reference TRUE) and a polyester-based (100% polyester, 295 g/m2, reference DORSET) fabrics, supplied by RIOPELE (Portugal).

The polymers used in the pre-treatments were a biopolymer based on a cationic polysaccharide (Biopolymer), and a polymer dispersion based on non-ionic aliphatic polycarbonate-polyether polyurethane (Binder A).

The pigments used included indigo (blue) and quinacridone (red) pigments in powder form, supplied by PILI (France) and produced via bacterial fermentation.

Methods

Pre-Treatment:

Textiles were pre-treated using foulard impregnation with the Biopolymer or Binder A, followed by a drying process at 100 °C for 3-5 minutes.

Characterization

The physical properties of the ink were analysed as follows - viscosity (smart series rotational viscosimeter by Fungilab, Spain), density (calculated dividing the mass by volume), surface tension (pendant drop method in the optical tensiometer Theta Flex by Biolin Scientific, Finland), particle size (Zetasizer NanoSeries Nano ZS90 by Malvern, UK).

Printing

The pre-treated and untreated textile fabrics were printed using inkjet printing technology, with valve-jet printhead (ChromoJet from Zimmer). After printing, the samples were dried at 100 °C for 3-5 minutes, followed by thermofixation at 150 °C for 5 minutes.

Printing Characterization

The printed fabrics were characterized regarding their colour fastness to washing (domestic washing at 40 °C, and up to 20 cycles), to artificial light (ISO 105-B02:2014), to artificial weathering (ISO 105-B04:1997) and to rubbing, dry and wet (ISO 105-X12:2016).

3. Results

This study aimed to determine the viability of bio-based pigments as sustainable alternatives to conventional synthetic pigments in digital textile printing. This section presents the experimental results concerning the physical characterization of the inks, printing performance on different substrates, and the evaluation of colour fastness under washing, rubbing, and artificial light and weathering exposure.

3.1. Physical Properties of the Inks

Table 1 summarizes the key physical parameters of the inks formulated with 0.5% bio-based indigo and quinacridone pigments. Both inks presented viscosity, density, surface tension, and particle sizes that fall within acceptable ranges for valve-jet inkjet printing technology.

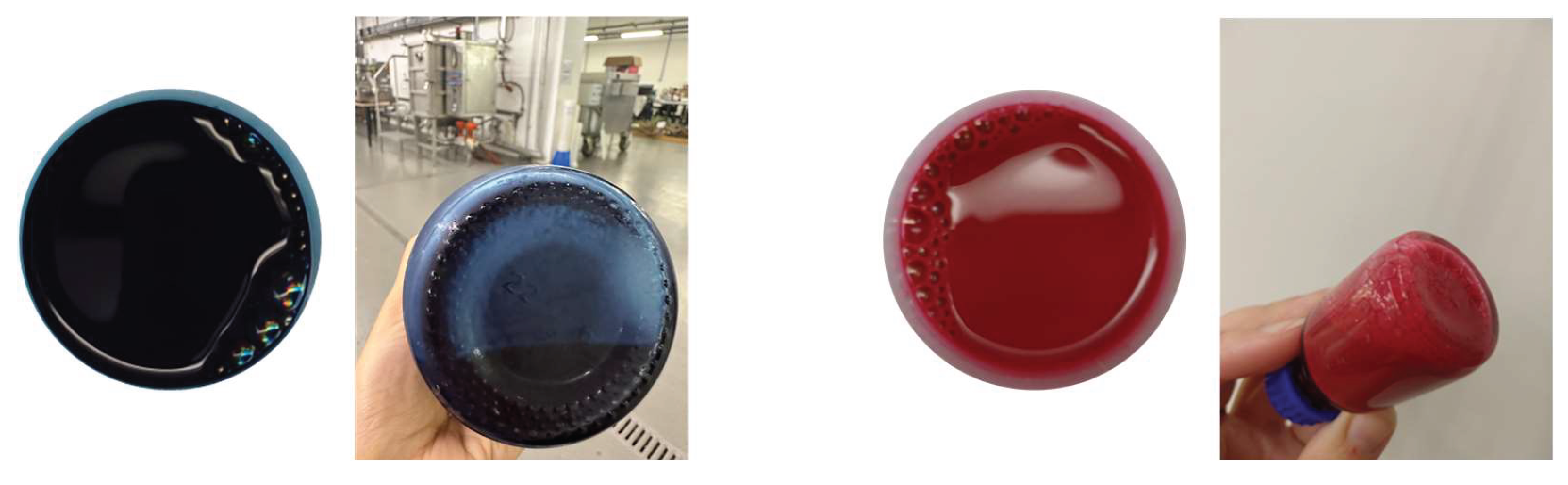

The indigo-based ink showed a viscosity of 5.29 cP and a surface tension of 34.6 mN/m, with particle sizes between 320–350 nm. The quinacridone-based ink exhibited slightly higher viscosity (6.81 cP) and lower density (0.93 g/cm³), with particle sizes below 5 µm. Although both inks were considered suitable for use with ChromoJet equipment, the pigment dispersion stability differed significantly between them. The indigo ink showed visible sedimentation and pigment agglomeration after resting. In contrast, the quinacridone ink demonstrated excellent dispersion stability and homogeneity, with no visible signs of sedimentation over time (

Figure 1).

3.2. Printability and Fabric Interaction

Printing trials were conducted on untreated and pre-treated cotton and polyester fabrics.

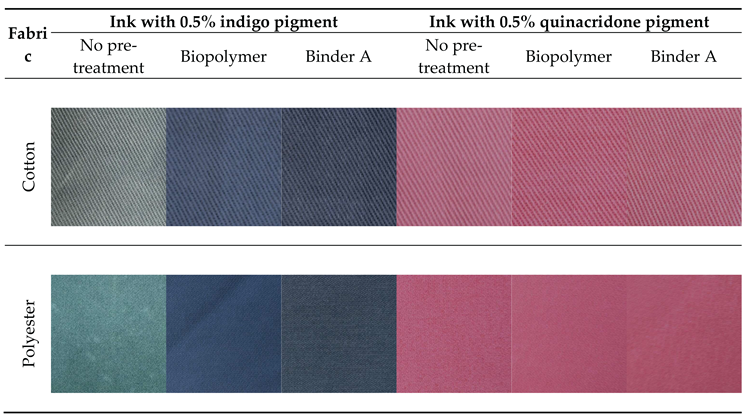

Figure 2 shows examples of the printed samples.

Table 2 shows photographs of each printed sample, demonstrating that colour intensity and uniformity are significantly influenced by both the type of substrate and the pre-treatment applied.

The indigo pigment produced different visual outcomes depending on the substrate. On untreated cotton, the colour appeared as a greyish, while on polyester, especially without pre-treatment, a greenish shift was observed. Best results in terms of visual intensity were achieved on cotton treated with Biopolymer and polyester treated with Binder A. On the other hand, the quinacridone ink yielded a strong and uniform red coloration, particularly on biopolymer-treated cotton and untreated polyester. These results indicate that pigment–substrate interactions, as well the pre-treatments play an important role in the fixation and appearance of the bio-based pigments.

3.3. Printing Characterization

Colour fastness tests were conducted following standardized methods to evaluate the performance of the printed fabrics.

3.3.1. Indigo Pigment

The results of the fastness tests carried out on the samples printed with indigo ink are shown in

Table 3.

For the indigo-based ink, wash fastness results on cotton ranged from grade 3 (untreated and Binder A) to 3–4 (biopolymer-treated), with a gradual decline in performance after 10 to 20 cycles. The polyester pre-treated with Binder A showed better resistance to washing, with a rating of 4-5 up to 5 cycles and a rating of 4 up to 10 cycles. In rubbing tests, both cotton and polyester achieved good dry rubbing resistance (grade 4–5), while wet rubbing results were slightly lower (grade 3–4). Light fastness was performed only in one sample, to assess the performance of the pigment, and the result was acceptable for most textile applications (3-4), while the colour fastness to weathering gave slightly better result (4), indicating the good behaviour of this pigment / ink even under high humidity conditions.

3.3.2. Quinacridone Pigment

The results of the fastness tests carried out on the samples printed with the quinacridone ink are shown in

Table 4.

The quinacridone ink exhibited excellent colour fastness to weathering across all pre-treatments used, consistently achieving ratings exceeding 5. In terms of wash fastness, cotton samples demonstrated superior resistance, maintaining ratings of 5 to 4–5 for up to 10 washing cycles, with a slight reduction to 3–4 after 20 cycles. Rubbing fastness values, under both dry and wet conditions, followed a comparable trend. Among the cotton substrates, untreated samples exhibited enhanced pigment fixation and superior fastness performance.

For polyester substrates, overall wash fastness performance was also high, with ratings ranging from 5 to 4 up to 10 washing cycles. Samples treated with Binder A exhibited the highest fastness values in both washing and rubbing tests. In contrast, untreated samples showed better wash fastness but lower wet rubbing resistance. Meanwhile, samples pre-treated with Biopolymer showed a slight decline in wash fastness, suggesting that Binder A may be the most effective auxiliary to improved durability.

4. Discussion

The development of water-based pigment inks using bio-based pigments derived from bacterial fermentation presents a promising step towards sustainable digital textile printing. The results of this study confirmed the viability of incorporating such pigments in powder form directly in inkjet formulations, particularly when applied through valve-jet technology (ChromoJet), which is typically more tolerant to pigment particle sizes than piezoelectric print heads.

Regarding ink stability and formulation, the indigo-based ink demonstrated some limitations in terms of dispersion stability. The pigment’s particle size (320–350 nm) approached the upper limit for inkjet applications and led to visible sedimentation after short periods of rest. These observations suggest the need to optimize the pigment dispersion, possibly through the incorporation of additional dispersing agents or the use of milling techniques to reduce particle size and prevent agglomeration. In contrast, the quinacridone-based ink showed excellent dispersion and did not exhibit sedimentation, highlighting its superior compatibility with aqueous inkjet systems.

The results clearly show that the fabric pre-treatment significantly influences print quality and fastness properties. In the case of cotton substrates, pre-treatment with Biopolymer enhanced pigment fixation, especially for the quinacridone ink, while for the indigo ink higher colour intensity was observed without pre-treatment. This suggests that the pre-treatment influences the surface of the textile, affecting the levelling and spreading of the ink. Given the chemical nature of the indigo pigment, which can exist in its oxidized or reduced form, presenting different colours, the prints obtained with this ink also reflected this colour change, which further confirms the need to stabilize the indigo ink in future works.

For polyester substrates, the Binder A (polycarbonate-polyether polyurethane) pre-treatment showed superior results with the indigo ink, indicating good pigment–polymer interactions and potential film formation aiding in the fixation of the pigment. However, for the quinacridone ink, the untreated polyester surprisingly outperformed pre-treated ones, possibly due to the pigment’s intrinsic affinity to hydrophobic surfaces or reduced interference from the binder matrix.

In terms of colour fastness, both inks performed exceptionally well, especially considering their bio-based origin. The quinacridone ink showed outstanding weathering fastness (grade >5), exceeding typical values reported for natural pigments, which are often prone to photodegradation. . The indigo ink also achieved strong light and weathering fastness (grades 3-4 and 4), suggesting potential for long-term exposure applications.

Wash and rub fastness results were within acceptable industrial ranges, particularly for fashion applications, and improved with the use of appropriate pre-treatments. While the indigo ink requires further formulation refinement to enhance stability and performance consistency, the quinacridone ink already meets key performance indicators for textile printing.

5. Conclusions

This work demonstrates the successful formulation and application of water-based digital inks using bio-based pigments produced through bacterial fermentation. The inks were effectively applied to cotton and polyester fabrics using valve-jet technology and evaluated for colour fastness to washing, rubbing, and artificial light and weathering.

The quinacridone ink showed excellent dispersion and overall superior performance, particularly in weathering fastness and uniformity of the printed fabrics. The indigo ink, while slightly less stable, also achieved good results, especially in polyester fabrics pre-treated with a synthetic binder.

Notably, the use of a biopolymer pre-treatment on cotton improved pigment adhesion and wash resistance for both pigment types, aligning with the objective of increasing sustainability through bio-based auxiliaries. The findings indicate that bio-based pigments can match or even exceed the performance of some commercial synthetic pigments, particularly in fastness to light, a common drawback in many natural pigment systems.

Overall, these findings support the integration of biotechnologically derived pigments into water-based digital printing processes and paves the way for greener alternatives in textile surface design. They also reinforce the importance of a holistic approach to ink development, encompassing pigment properties, formulation additives, textile substrate characteristics, and pre-treatment chemistry. Further research is encouraged to refine pigment dispersion, expand the colour palette, and optimize ink formulations for a broader range of printing heads, including piezoelectric systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A. and H.V.; methodology, J.A, M.L., and B.M.; investigation, J.A, M.L., B.M. and A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A, M.L., and B.M.; writing—review and editing, H.V.; supervision, A.S. and C.J.S.; project administration, H.V. and C.J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was carried out under the Waste2BioComp project - Converting organic waste into sustainable bio-based components, GA 101058654, funded under the topic HORIZON-CL4- 2021-TWIN-TRANSITION-01-05 of the Horizon Europe 2021 – 2027 program.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ragab, M. M.; Othman, H. A.; Hassabo, A. G. An Overview of Printing Textile Techniques. Egypt. J. Chem. 2022, 65, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodyashkin, A. A.; Makeev, M. O.; Mikhalev, P. A. Inkjet Printing Is a Promising Method of Dyeing Polymer Textile Materials. Polymers 2025, 17, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Zhendong, W.; Chuanxiong, Z.; Ruobai, X.; Wenliang, X. A Study on the Applicability of Pigment Digital Printing on Cotton Fabrics. Tex. Res. J. 2021, 91, 2283–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkalec, M.; Glogar, M. I.; Sutlovic, A. Ecological sustainability of digital textile printing. Econ. Soc. Dev. 2022, 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Hassabo, A.; Abd El-Salam, N.; Mohamed, N.; Gouda, N.; Khaleed, N.; Shaker, S.; Abd El-Aziz, E. Naturally Extracted Inks for Digital Printing of Natural Fabrics. J. Tex., Color. Polym. Sci. 2024, 21, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y. Inkjet Printing Quality Improvement Research Progress: A Review. Heliyon 2024, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, Y.; Shin, Y. Inkjet Printing of Textiles Using Biodegradable Natural Dyes. Fibers Polym. 2023, 24, 1695–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawiah, B.; Howard, E. K.; Asinyo, B. K. The chemistry of inkjet inks for digital textile printing-review. BEST J. 2016, 4, 61–78. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).