1. Introduction

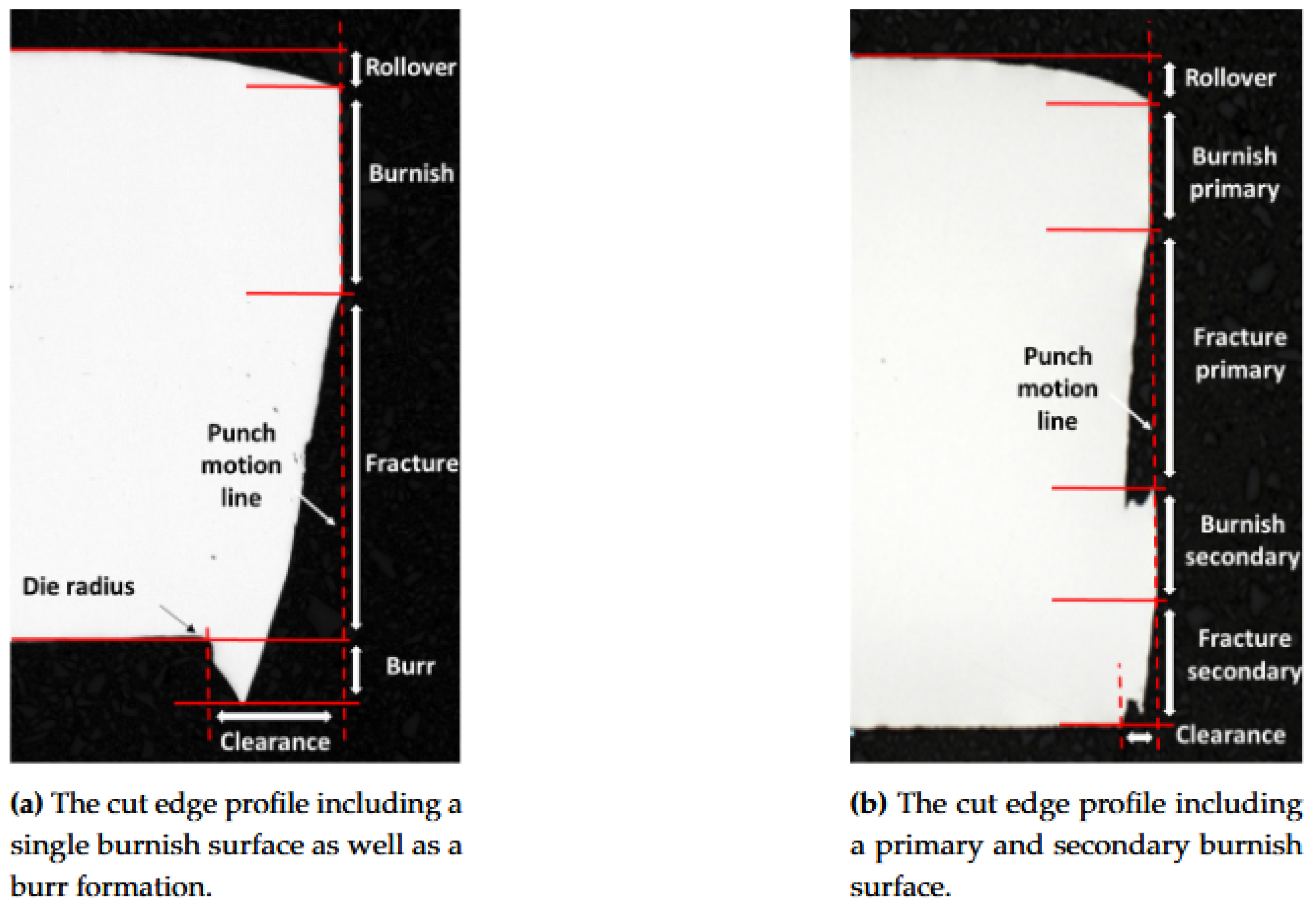

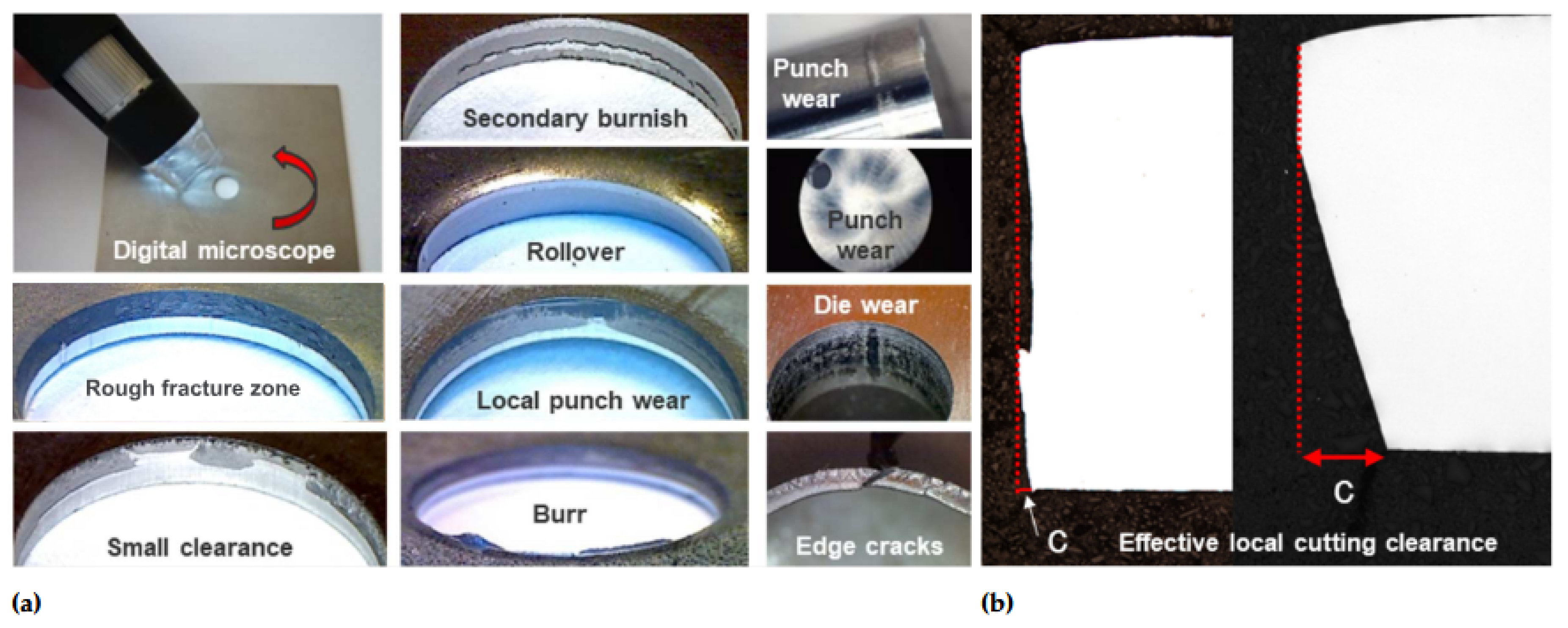

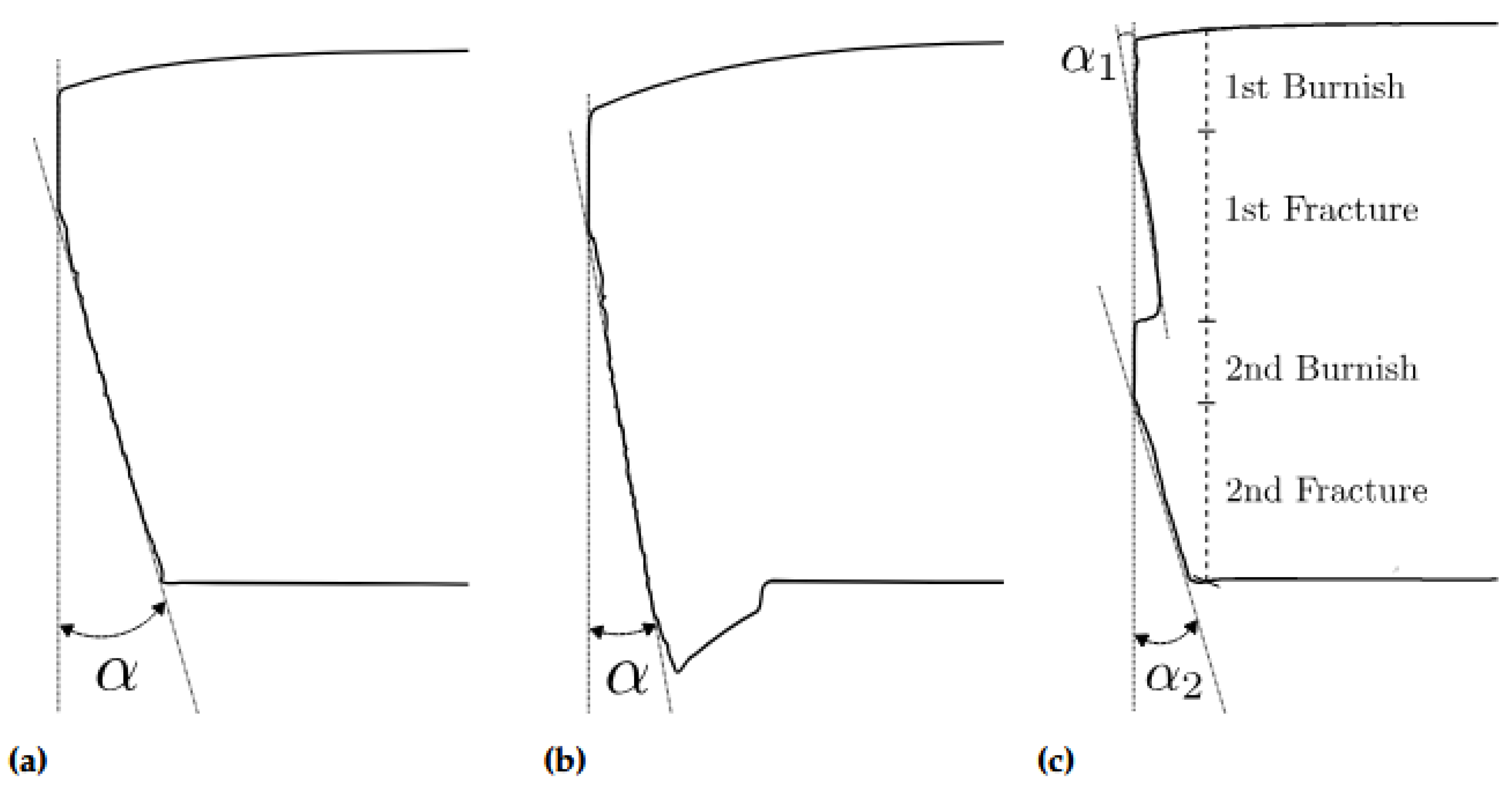

Shear cutting remains the most common cutting technique in the cold sheet forming process, due to automation possibilities and cost-efficiency. This technique involves a shearing process where the sheet metal is separated by a moving punch, pushing the workpiece against the fixed die. This process typically results in the formation of a cut edge with a characteristic profile, consisting of the rollover formation, the burnish zone, the fracture zone, and the burr formation, as seen in

Figure 1 (a).

Figure 1 (b) shows the distinction between primary and secondary burnish and fracture, features that might appear at low cutting clearances.

While shear cutting offers efficiency and precision, the nature of the operation inevitably causes localized deformation and damage to the material, which can manifest as burrs, micro-cracks, and strain hardening near the cut edge [

1]. This region, often referred to as the Shear Affected Zone (SAZ), is known for affecting the formability of sheared parts and triggering edge cracking, especially for Advanced High Strength Steels (AHSS) [

2]. This has been experimentally shown for both close cuts [

3] and open cuts [

4], varying cutting clearance and material grade [

5] and with varying punch tool design [

6]. The sheared edge damage is also known to affect the fatigue properties of high strength sheets since the cutting process induces microcracks and notches [

7,

8,

9] and residual stresses to the cut edge [

10,

11]. Sheared edge damage is also a factor in hydrogen embrittlement of AHSS [

12,

13]. Factors influencing the characteristics of the SAZ include the material mechanical properties and cutting conditions (such as cutting clearance, cutting speed and tool wear) [

14]. For instance, AHSS grades with ultimate tensile strength (UTS) of 1000 MPa and above, now increasingly used in lightweight construction and safety-critical applications, are particularly susceptible to localized sheared edge damage due to their higher strength and reduced ductility compared to lower strength conventional AHSS sheets. As a result, understanding and controlling the residual state of the SAZ, introduced by shear cutting, is important for ensuring product reliability and optimizing performance during the manufacturing process.

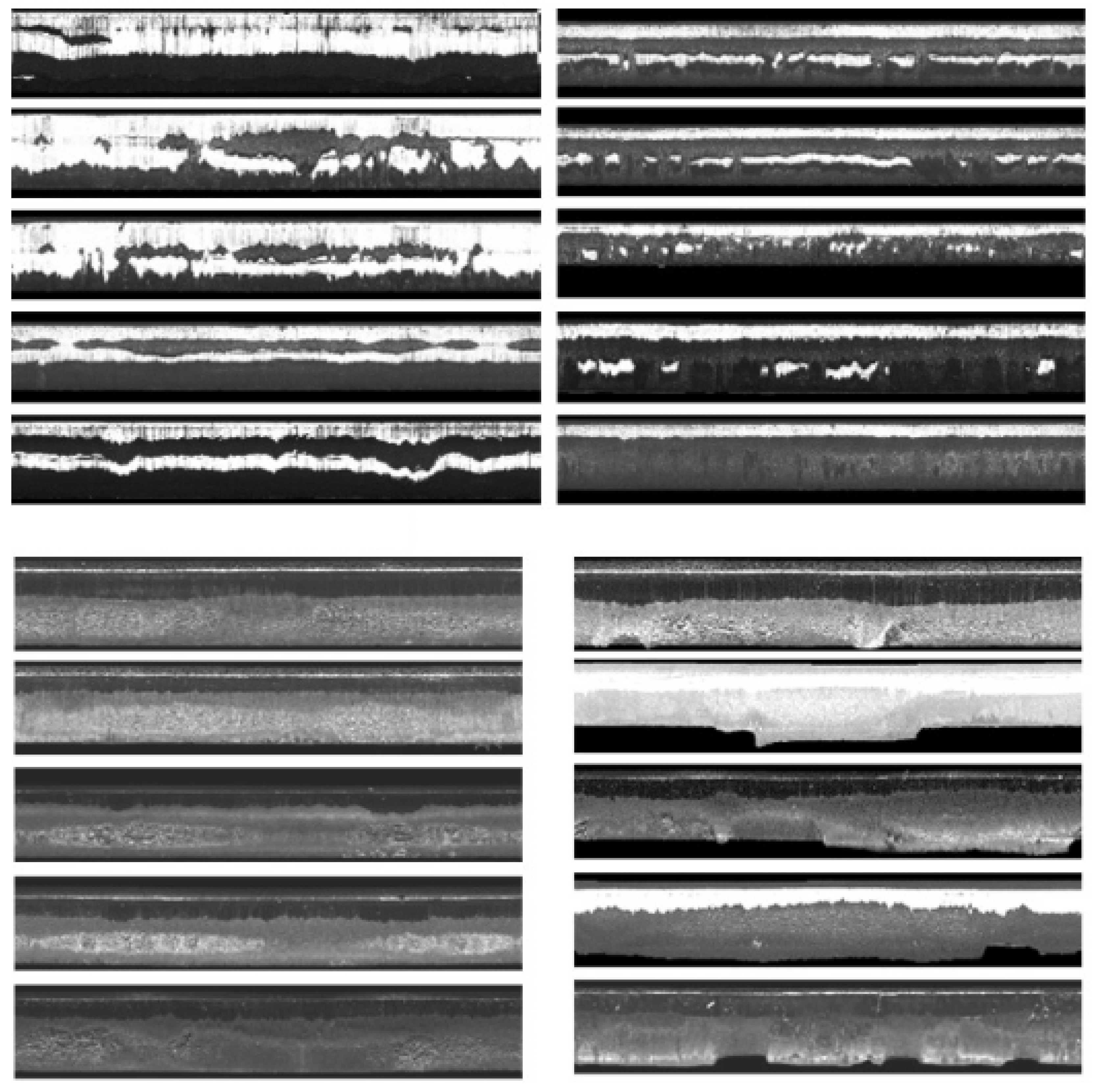

Traditionally, sheared edge damage investigation has been performed at different magnification levels, starting from naked eye observation, to microscopic investigation and using metallographic techniques for detailed analysis.

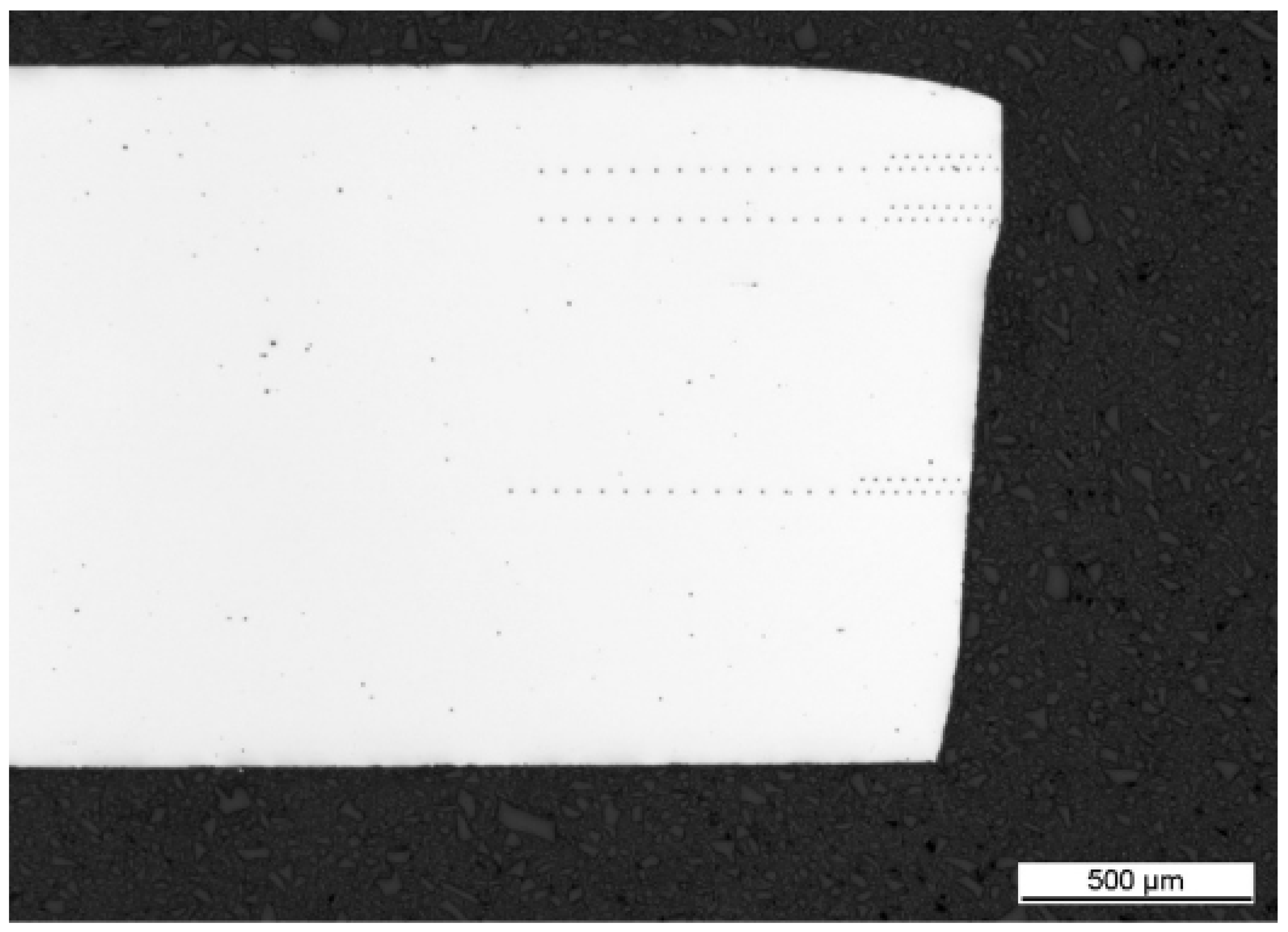

Figure 2 shows conventional cut edge inspection techniques and presents typical appearance of secondary burnish in close cut hole edge, as well as burr and fracture surface roughness.

Figure 3 shows the open cut secondary burnish formation in different proportion, from little to strongly manifested secondary burnish merging with primary burnish. Some irregular burr and rough cut edge fracture surface are also displayed.

Detailed investigations of sheared edge damage are conventionally performed using destructive techniques, such as cross-sectional analysis through metallography and microhardness tests. These methods provide valuable insights into the extent of SAZ damage, allowing quantification of the degree of deformation and identify defects like cracks, voids, or brittle phases. However, the destructive nature of these methods limits their applicability, especially in cases where circumferential heterogeneity and spatial variations in sheared edge damage need to be assessed. Such circumferential heterogeneities typically appear in punched sheet holes in industrial forming lines and reduce the stretch-flangeability of the edge [

15], due to unavoidable tool wear or tool misalignment during part production. In contrast, the use non-destructive cut edge assessment methods does allow for repeated use of the shear cutting specimens and are required for in-line measurements. In this work, the main focus is laid on conventional readily and widely available non-destructive testing methods using light optical microscopy (LOM) which is part of the standard equipment in industrial laboratory environments. Therefore, expensive, time consuming and punctual detailed non-destructive methods such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM) or electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) are disregarded, although their use in laboratory SAZ damage identification is well proven [

16,

17,

18].

This study investigates the sheared edge damage in a 1.5 mm complex-phase advanced high-strength steel (AHSS) with UTS

MPa, which is characterized by highly localized shear deformation and a narrow shear-affected zone (SAZ). Such localization challenges the assessment of edge quality and its influence on subsequent forming and fatigue performance. The experimental work presented in this article is based on hole punching using varying process parameters, where the resulting damage was analyzed across macro, meso, and micro length scales. Conventional SAZ characterization methods, including Vickers hardness (DIN ISO 6507) [

19], which is frequently used in conventional cutting [

20,

21], two-stage shear cutting [

22], and post-cutting fatigue studies [

10], and grain shear angle measurements [

12,

23,

24,

25], are evaluated for their suitability in large-sample investigations. In addition, the study explores the use of 2D panoramic and 3D profile microscopy as efficient, non-destructive techniques for detailed cut edge assessment, particularly for small, close-cut geometries. The overall objective is to improve the reliability of SAZ characterization and propose practical, scalable methods to address the heterogeneous edges typical of high-strength steels. The methods developed in this work make use of cost-effective microscopy instruments with minimal image processing, providing both research and industry with valuable tools to enhance shear cutting processes and improve the formability and fatigue resistance of AHSS components.

3. Results

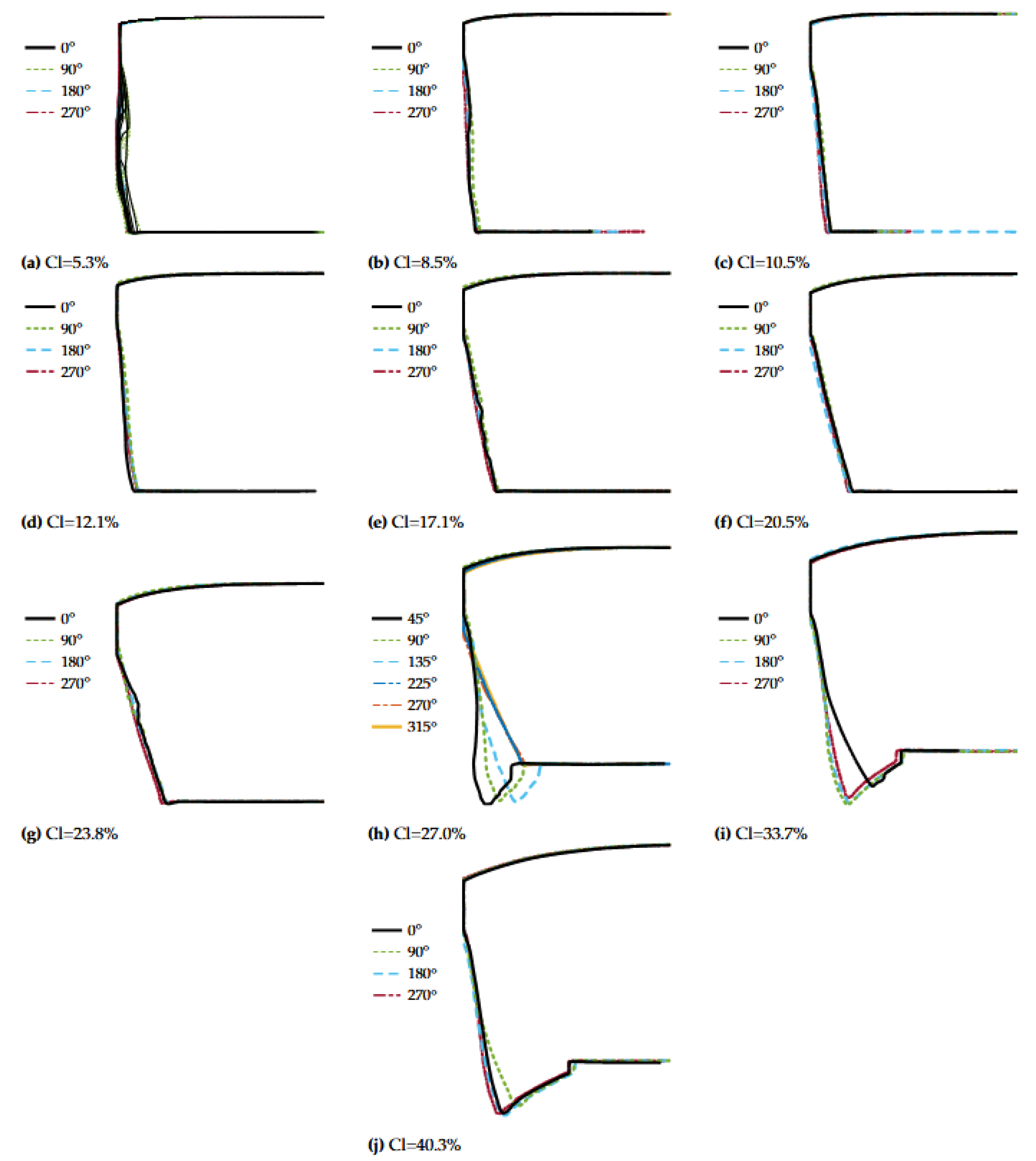

Using the 3D stereo optical cut edge methodology presented in

Section 2.2.2, the cut edge profiles for at least four different positions along the hole perimeter were extracted. These profiles are shown in

Figure 16. Due to the appearance of partial burr at around

and

rotation for the 27% cutting clearance case, several additional profiles were extracted.

The 5% cutting clearance case involved significant circumferential heterogeneity, causing the appearance of secondary burnish islands within the fracture zone and uneven distribution of burnish/fracture surface heights. This heterogeneity is displayed in

Figure 17, showing for different positions along the hole perimeter how the cut edge profile varies locally.

Figure 18 shows a superposition of 3D optical profiles from

Figure 16 and

Figure 17 in all directions along hole perimeter versus metallographic cross sections sampled longitudinal to rolling direction. For 5% cutting clearance, only the 3D optical profiles longitudinal to the rolling direction from

Figure 17 (a) are shown for clarity. For 27% cutting clearance the 0° metallographic section direction also coincided with the progressive burr-no burr transition zone along hole perimeter, leading to some more ambiguous comparison results with optical profiles.

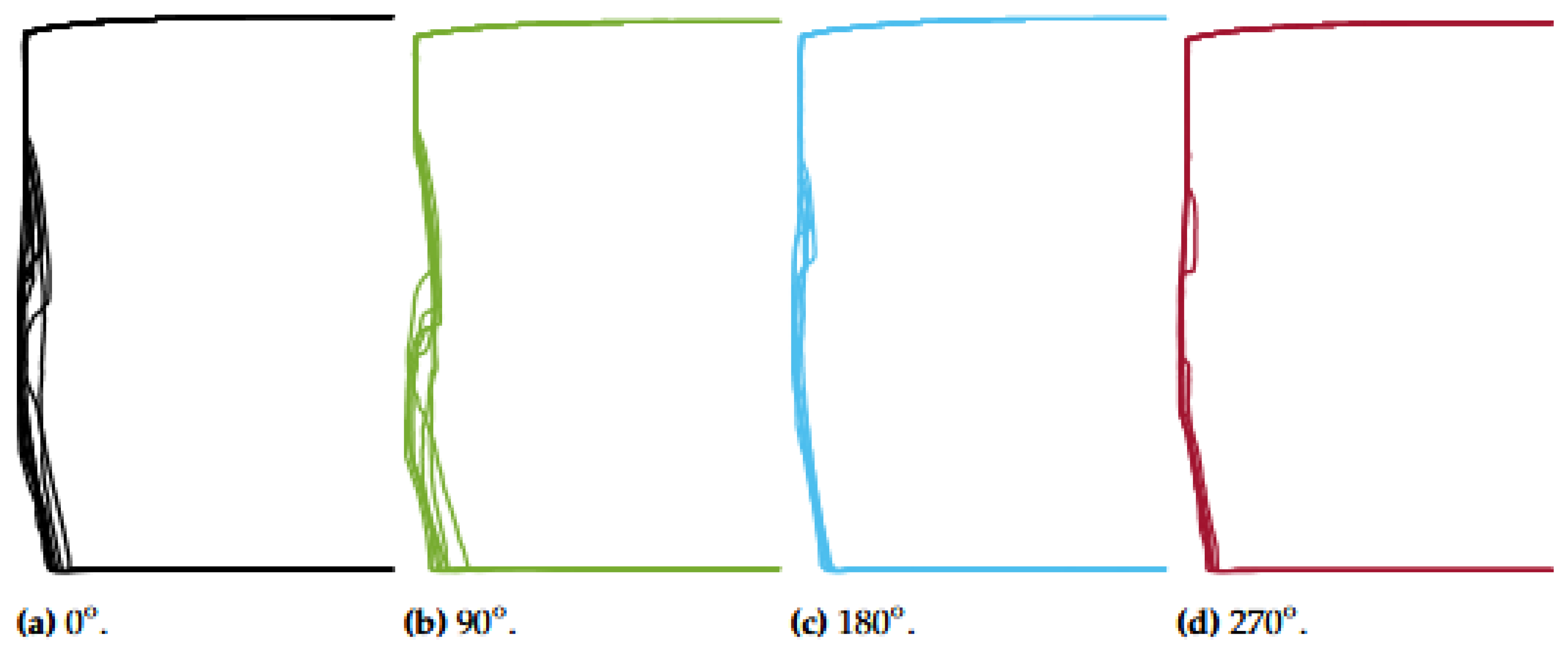

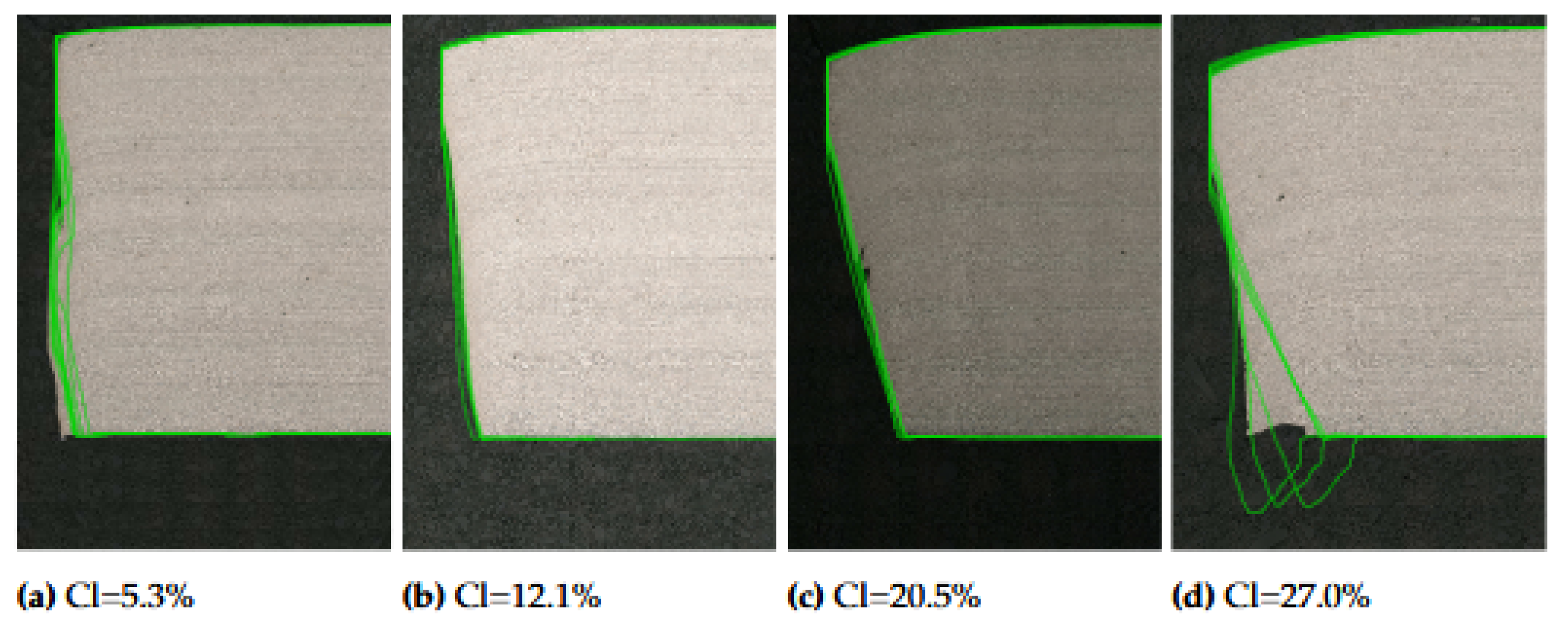

Similarly, the 2D optical EISYS methodology was compared to metallographic cut edge cross section, as presented in

Figure 19.

Figure 19 shows the cut edge cross section extracted longitudinal to the rolling direction and the EISYS results at 0

to the rolling direction, where the outer blank edges and the characteristic cut edge parameters are compared with red lines.

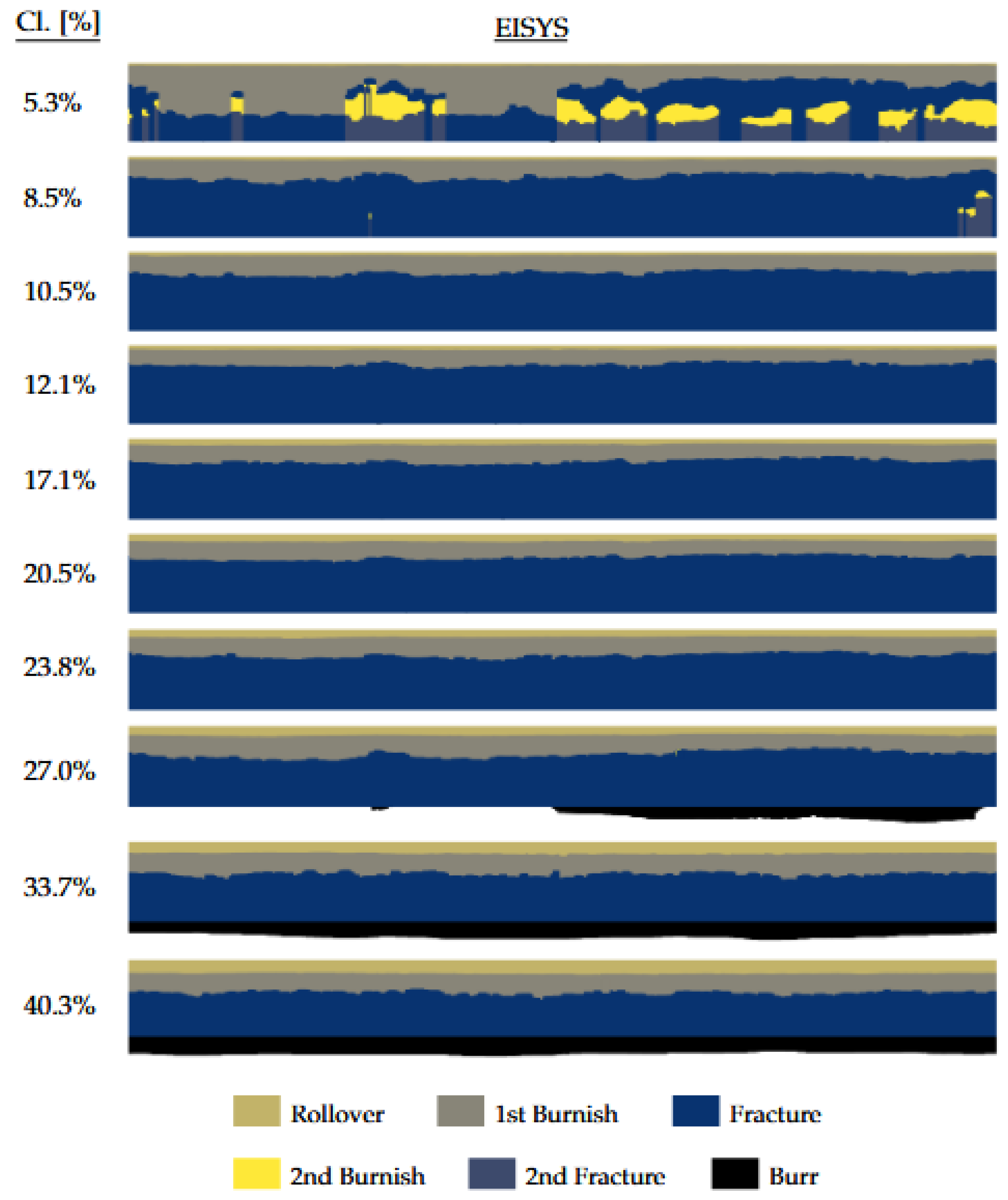

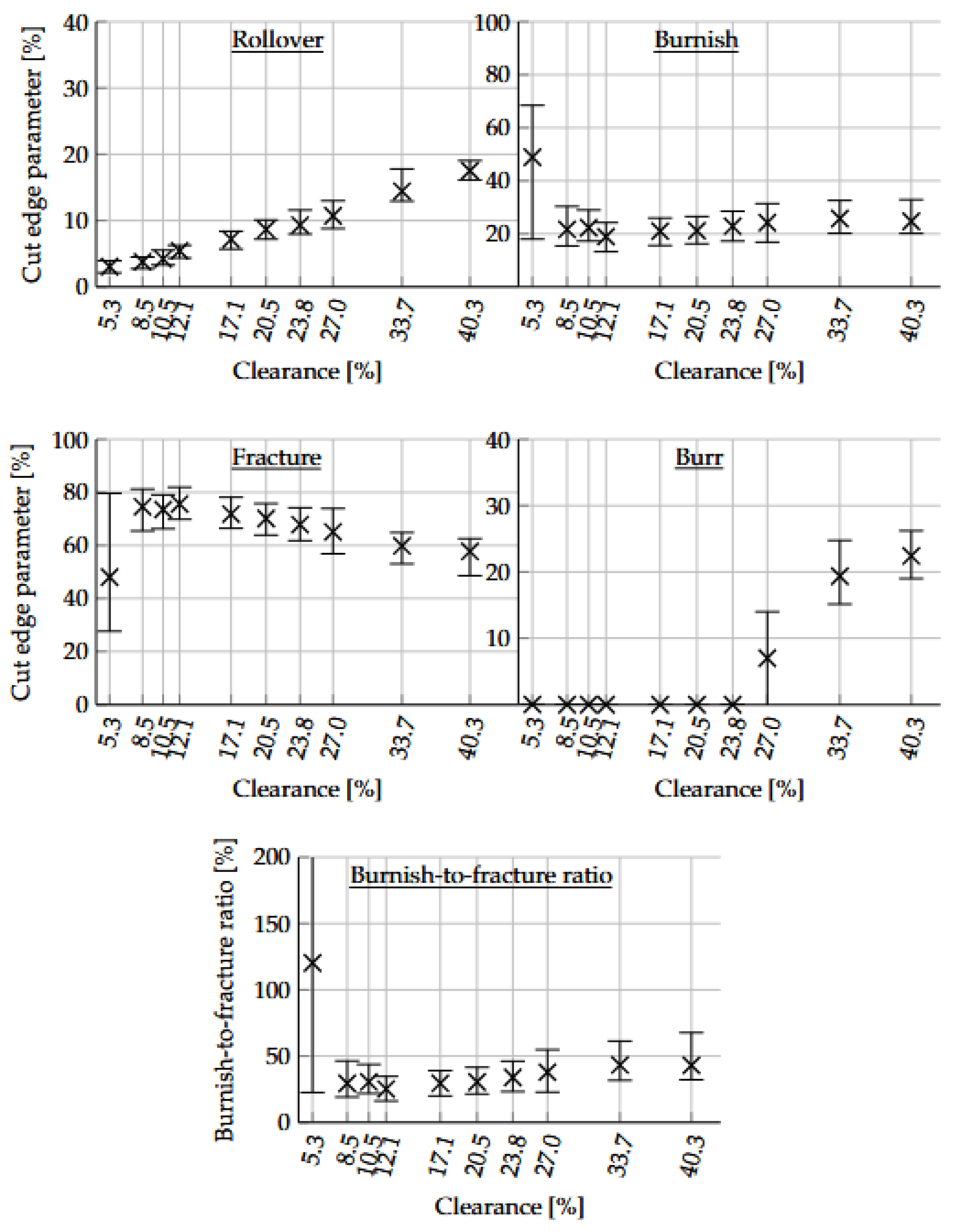

The final cut edge results were also defined in terms of rollover, burnish, fracture and burr height, i.e. the cut edge parameters and their respective distribution over the blank thickness, in accordance to

Figure 9. The results were obtained for the entire range of cutting clearances presented in

Table 2 using the 2D optical EISYS method described in

Section 2.2.1. The results shown in

Figure 20 describe the average cut edge parameters as black crosses and the circumferential variations as error bars (standard deviation).

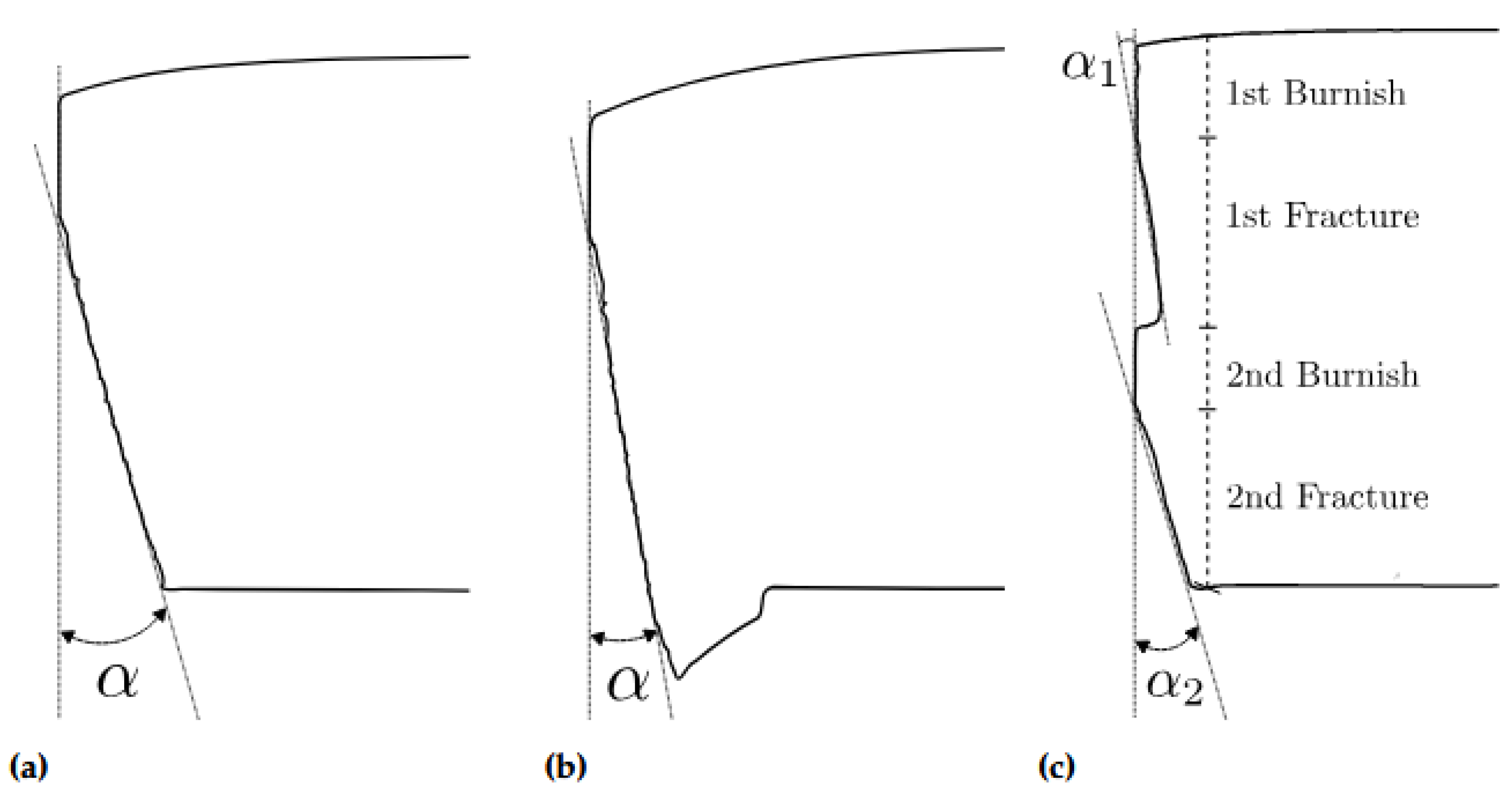

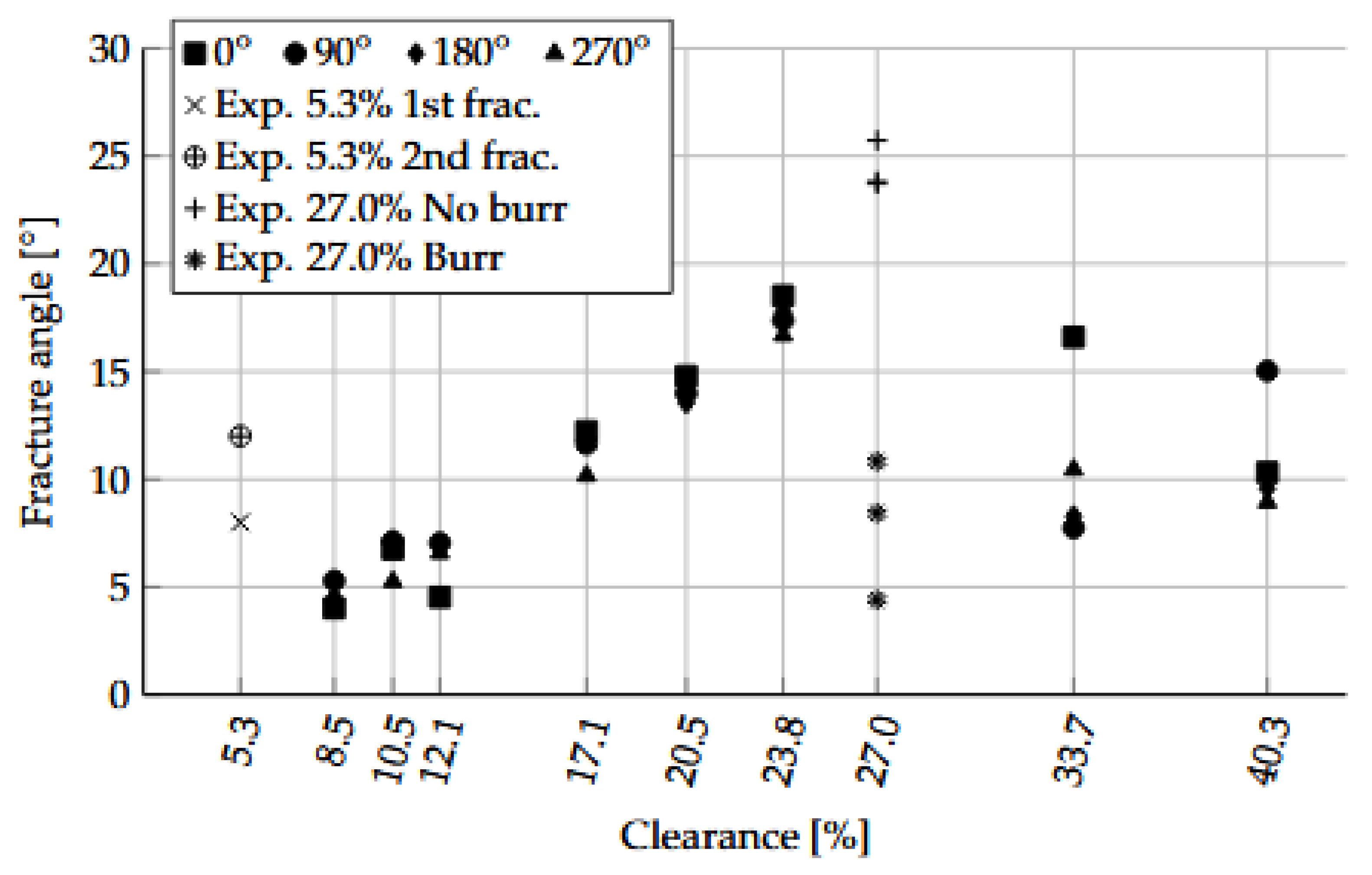

Similarly, fracture angles (defined in

Figure 12) are displayed in

Figure 21, measured from the cut edge cross profiles in

Figure 16 and

Figure 17. Due to the slight and unavoidable non-coaxiality of the tools, marginal clearance deviation occurred which caused variations of cut edge morphology and consequently, the fracture angles. Here, the results showed an increase in fracture angle until burr appeared at 27% cutting clearance, which caused the fracture angle to decrease. At higher clearances ≥27%, it can be assumed that the burr width increases in some extent at the expense of the fracture angle. For 27% cutting clearance, partial burr formation occurred which caused one part of the hole to have burr, while the other was left without. Therefore, the no-burr/burr fracture angles are displayed distinctly in

Figure 21.

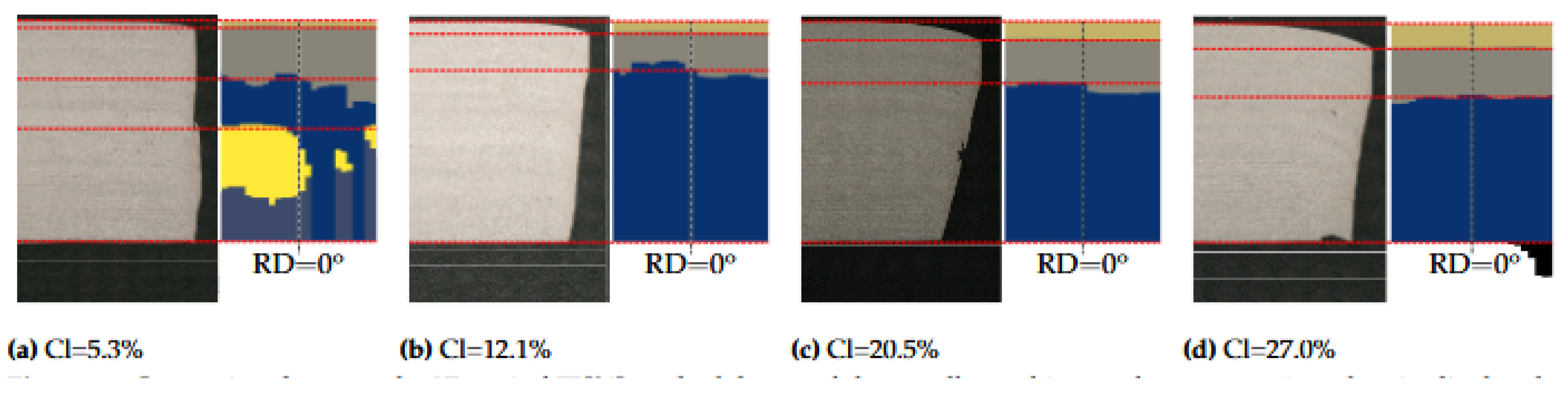

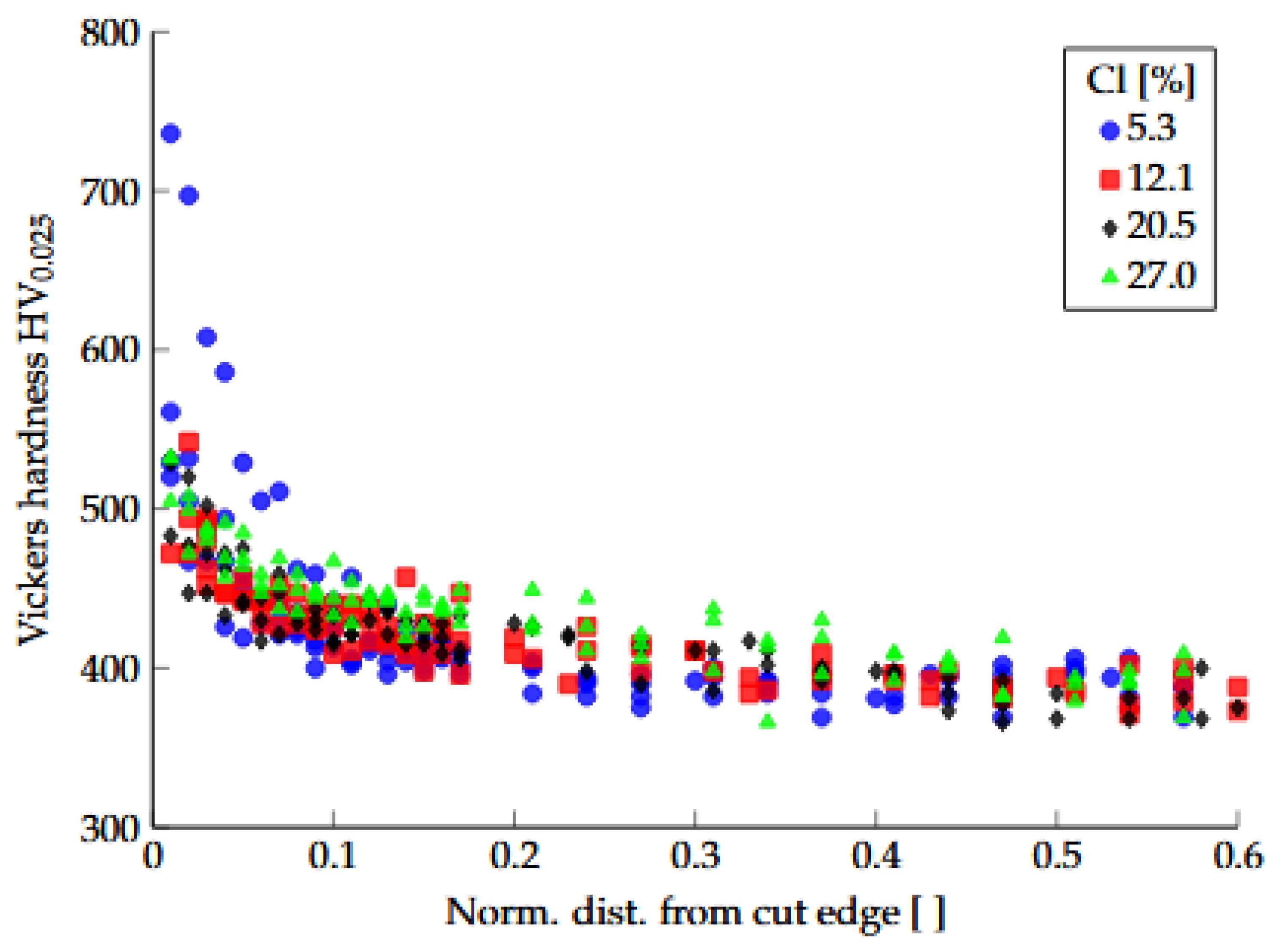

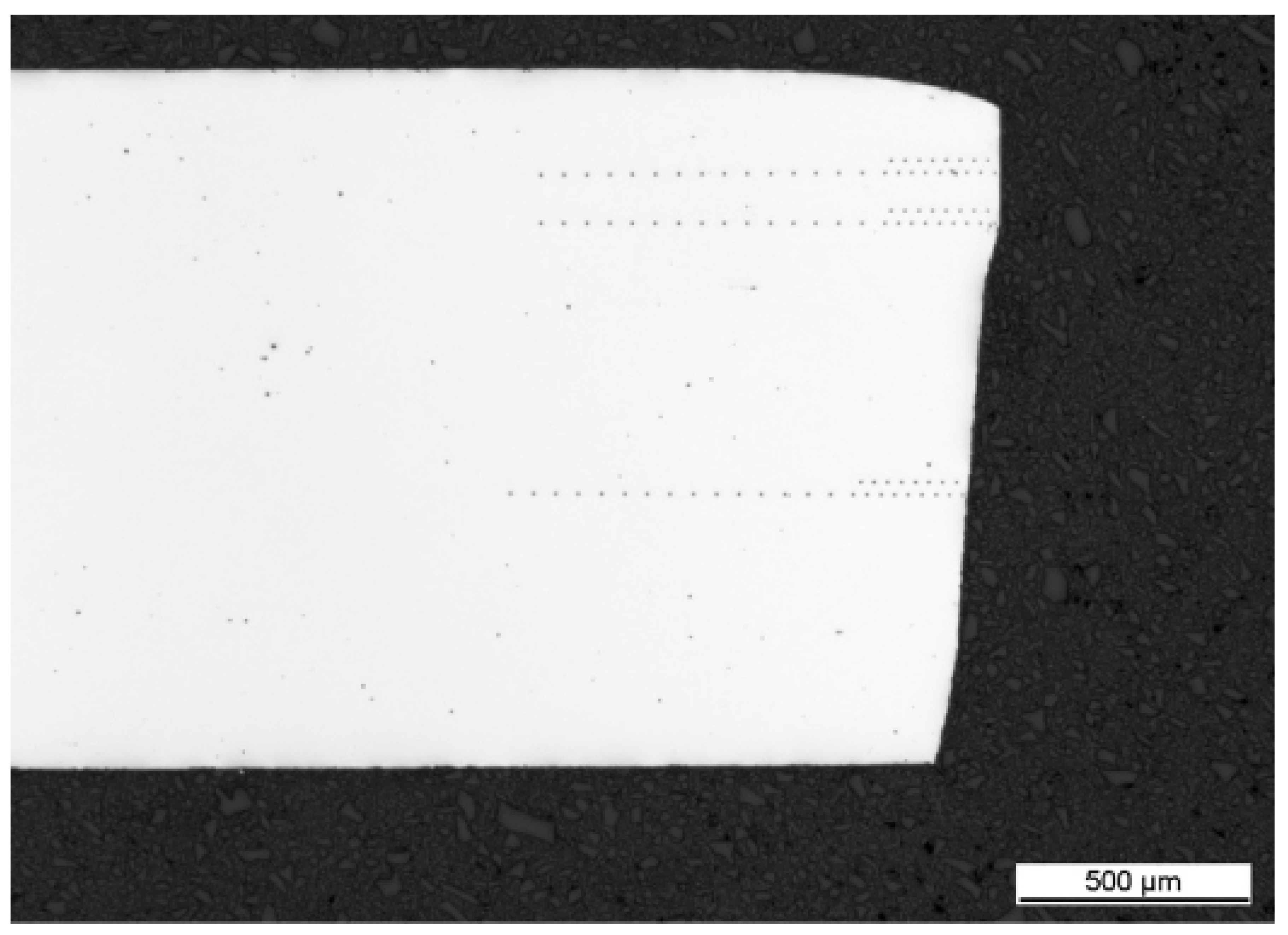

The hardness indentation results are shown in

Figure 22 for each cutting clearance, combining the three paths in burnish, burnish/fracture and fracture zones as illustrated in

Figure 13.

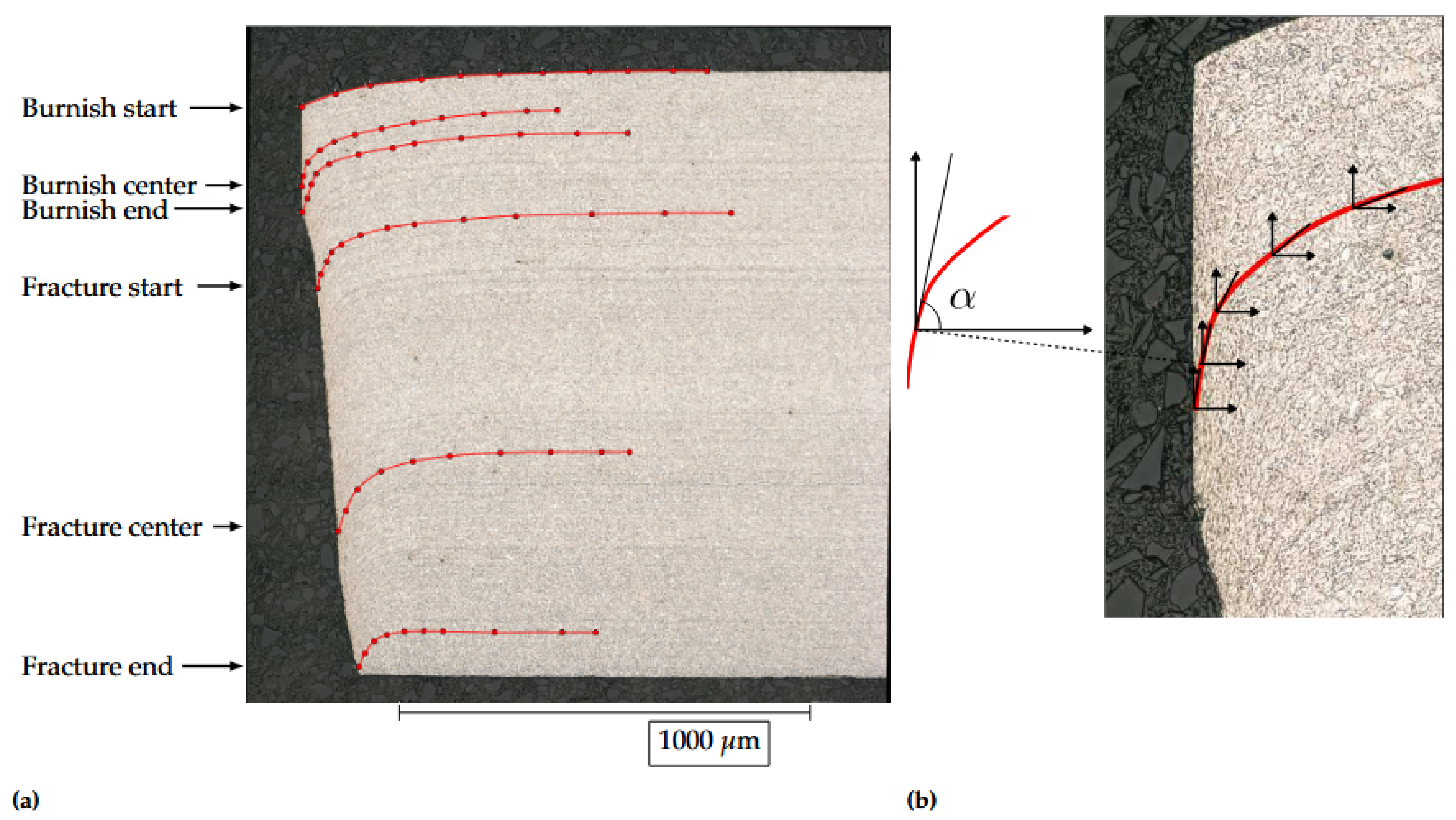

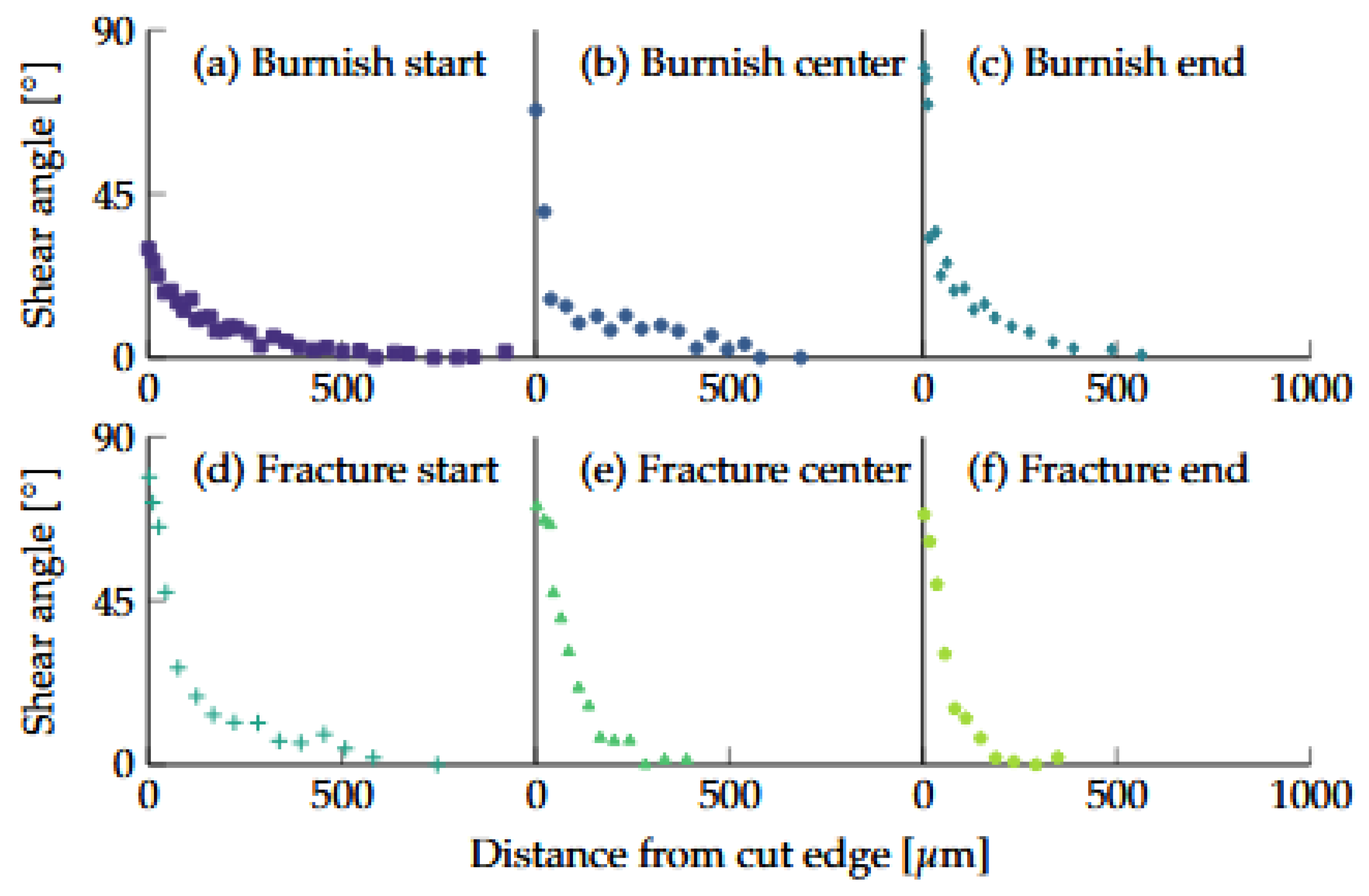

By investigating the material orientation of the SAZ, it was possible to determine the SAZ width and level of deformation in the cut edge vicinity. The grain shear angle results were obtained by the method described in

Section 2.2.4 according to the six paths shown in

Figure 14. The combined grain shear angle results from each path were gathered and plotted for each cutting clearance case, as shown in

Figure 23. As for the indentation results, the dimensionless normalized cut edge distance with respect to the blank thickness was introduced. In this figure, the piece-wise linear fitted lines determining the point of localized shear deformation and total SAZ width are shown.

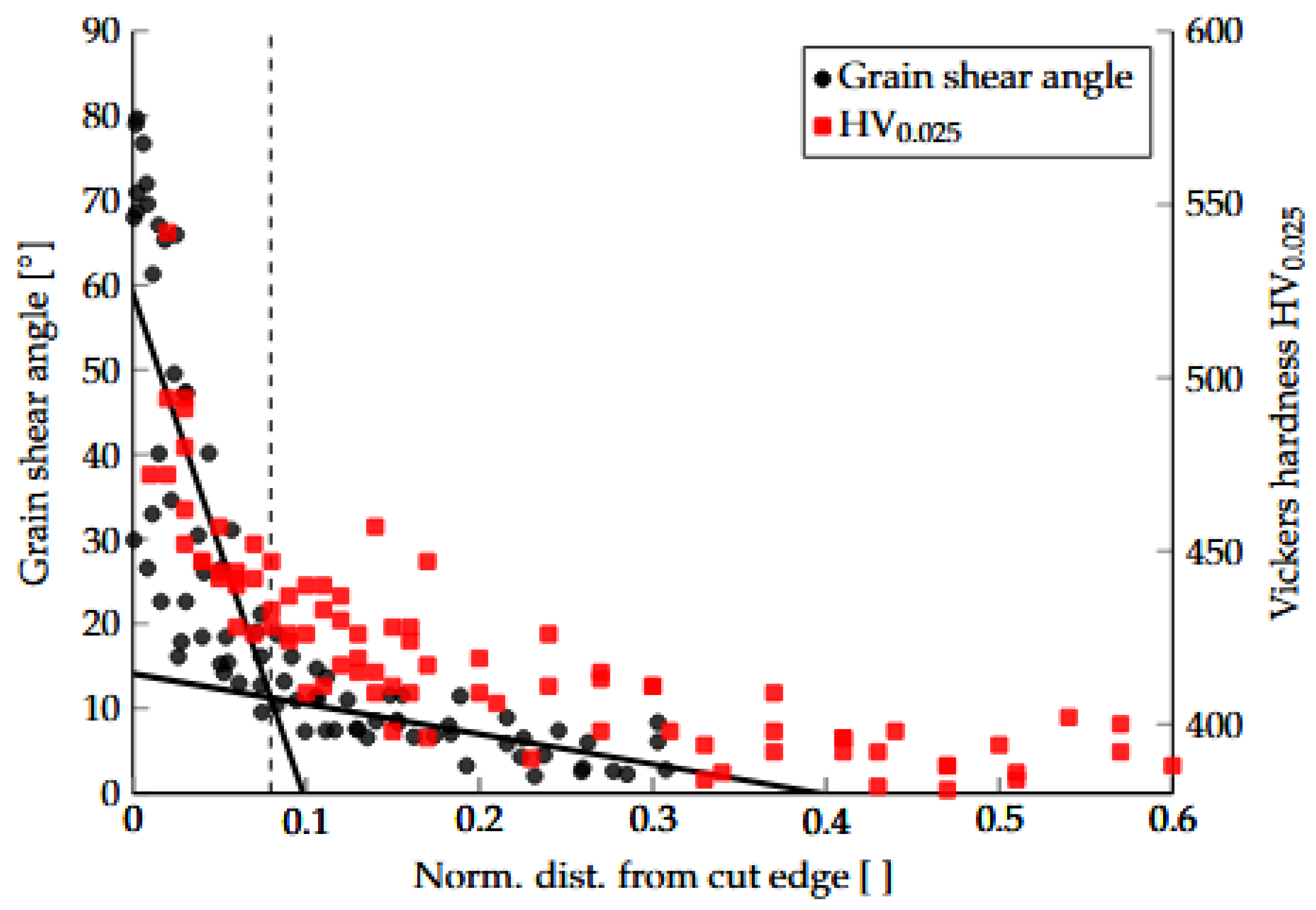

For comparison between the Vickers hardness measurements and the grain shear angle results, the respective results are shown in

Figure 24 for 12% cutting clearance.

Figure 25 shows the grain shear angle measurements at 12% cutting clearance for each of the paths mentioned in

Section 2.2.4. These results combined form the plot shown in

Figure 23 (b) and

Figure 24.

4. Discussion

Figure 16 shows how the non-destructive 3D Keyence cut edge assessment technique developed within the present work could produce reliable results of cut edge profiles around the hole perimeter. The use of such technique is straightforward, as it enables identification and measurement of local profiles, possibly involving unusual features such as secondary burnish formation and partial burrs. Similarly, the 2D panoramic EISYS cut edge investigation technique enabled an effective separation of each characteristic cut edge feature, as shown in

Figure 20. The present cutting clearance results for the CP1000HD grade fit well in the body of work with AHSS sheets found in the literature [

14]. With increasing clearance a steady rollover increase was seen, along with a moderate burnish decrease and strong fracture height decrease. Also, a burr increase was expected with increasing clearance. There seems to be a minimum value for burnish and burnish-to-fracture ratio around 15-20% clearance for AHSS grades, as also observed for other 1000-1200 MPa tensile strength steel grades by [

28]. Burr was triggered around 20-30% clearance as also observed in [

14]. The present CP1000HD punching clearance investigation showed partial burr formation starting at 27% and homogeneous burr formation at 34% and 40% cutting clearance around cut hole edge. Partial burr formation was possibly caused by the slight tool misalignment presented in

Section 2.1. The specific cut edge feature such as uneven burr along cut hole perimeter has been reported in similar investigations as a relevant issue impacting the further material cut edge stretch flangeability [

15,

30,

34].

On the opposite lower side of the cutting clearance spectra, the experimental cut edge results show islands of secondary burnish formation. The secondary burnish formations are shown in the circumferential representation of cut edge parameter distribution in

Figure A1, whereas

Figure 17 shows the various resulting shapes of the experimental cut edge profiles took along the hole perimeter. As for the case of 27% cutting clearance, the significant circumferential variation of the experimental cut edge morphology was caused due to the slight tool non-coaxiality shown in

Figure 5. The secondary burnish zones were formed due to mismatching fracture angles from the punch and the die edges. As shown in

Figure 21 in the low 5% clearance part, the fracture angles are higher compared to 8-10% clearance level. This is due to a higher total punch penetration depth up to secondary burnish end. This is true especially when considering the significantly higher secondary fracture angle

as compared to lower primary fracture angle

, as defined in

Figure 12 (c).

The comparison between metallographic cut edge cross section and the 3D Keyence profile technique in

Figure 18 clearly validates the use of such non-destructive edge profile method. Similarly, comparison between the cut edge cross sections and the 2D EISYS technique also confirms this approach, as shown in

Figure 19. The strength of the non-destructive 2D/3D high-resolution stereo optical methods were apparent as the circumferential variations of the cut edge were detectable.

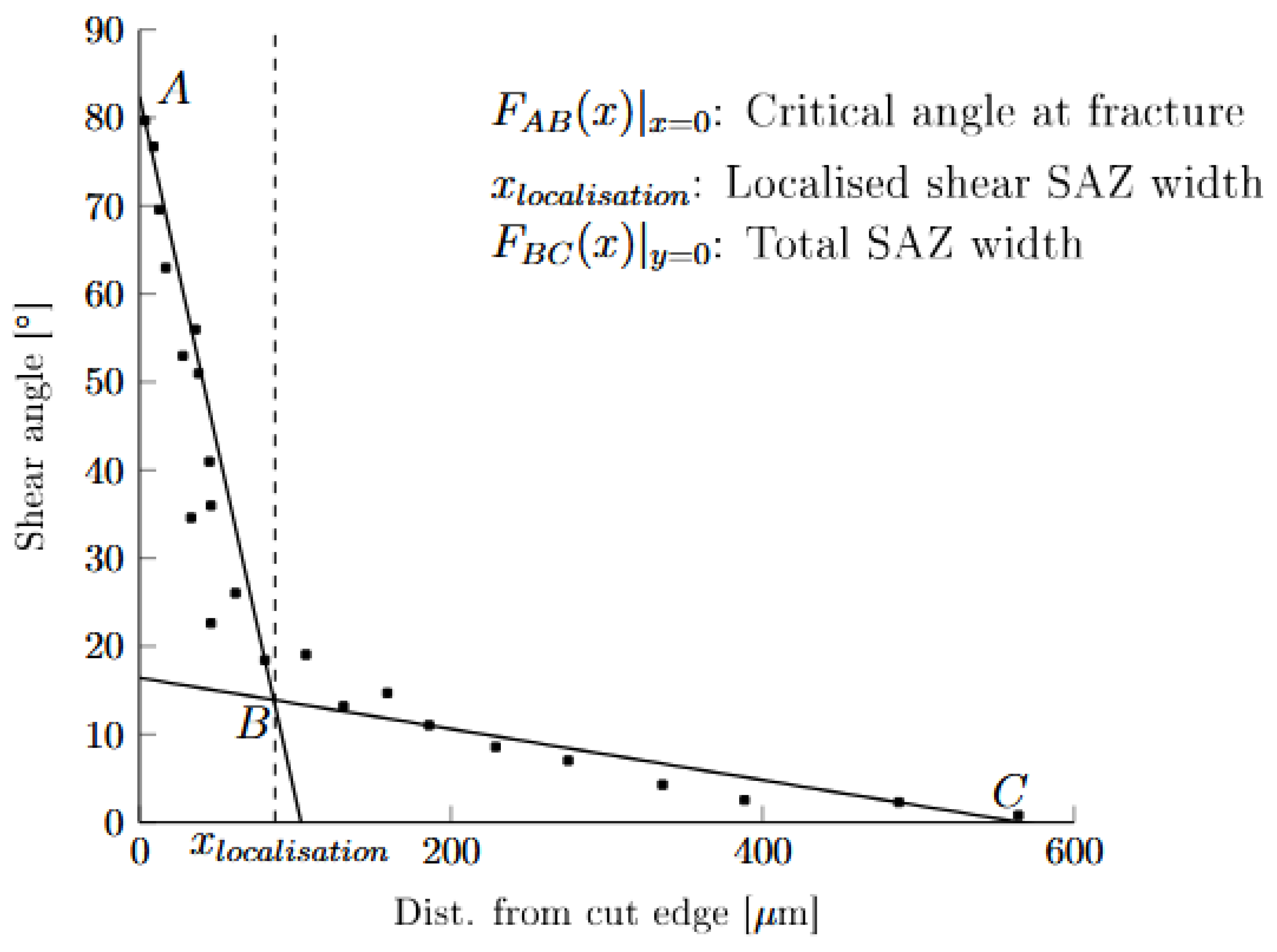

When investigating the SAZ in more detail by means of grain shear angle analysis method, a few observations can be made from

Figure 23 to

Figure 25. Firstly, grain shear angles reached approximately

in cut edge vicinity, which implies that the material undergoes extreme deformations in mixed compressive/shear stress states without fracturing (

Figure 23 and

Figure 24). Secondly, the total SAZ width appeared to be non-uniform in thickness direction and steadily decreasing close to the die. As an example,

Figure 25 shows the extent of the SAZ width derived from grain shear angle at different locations across cut edge from burnish start to fracture end zones. It becomes then apparent that the width of the plastically deformed overall SAZ zone decreases from cutting punch to die side. The localized deformation however remains confined around 0.1 normalized thickness level, whatever cut edge zone considered. This behavior is also confirmed in a similar grain shear angle experimental investigation for DP/CP800 grades [

23]. The width of the total SAZ had also an obvious clearance dependency (

Figure 23) as the bending of the blank structure increased with larger clearances, while the work hardening of the material was also considered to affect the total SAZ width. Accordingly, shear angle measurements may provide additional and relevant information to better understand sheared edge damage.

By comparison between Vickers hardness measurement and grain shear angle results in

Figure 24, it is apparent that grain shear angle measurements can better capture the sharp shear deformation localization tendency of the CP1000HD grade. Even though a small indentation weight (HV0.025) and parallel offset indentation tracks were used for increased resolution, it was still insufficient and resulted in a significant scatter (

Figure 22 and

Figure 24). Compared to the grain shear angle measurement, the point of

is rather vague from the hardness measurement. For open cut configurations, digital image correlation (DIC) may serve as a useful tool in determining the SAZ strain field [

35,

36,

37]. Such technique enables a step-by-step tracing of the SAZ strain field along the shear cutting process and investigation of individual strain components. However, there is no feasible way of performing DIC analysis of closed cut shear cutting due to the obvious reason that the deformation zone is within the material. In this case, assessment of the SAZ deformation needs to be done on post-cutting cross sections. In [

1,

23,

38], different approaches of calculating the effective and shear strain based on grain shear angles are presented, providing possibilities of strain mapping of the SAZ without the use of stepwise DIC monitoring. This grain shear angle technique can even be used postmortem for industrial components sheared edge analysis, whereas DIC online punch monitoring is also not feasible in a press shop environment. Additionally, nano-indentation is a powerful tool for local hardness evaluation [

39] and could give more accurate results near the edge [

40]. The use of nano-indentation is out of the scope of the present paper, but should be considered in future works. One noticeable experimental method consists in a probe arm with two needles [

32], such mechanical scanning device being able to record 3D profiles of the whole shear cut edge at once with an even better accuracy (0.5 µm) than for optical Keyence system (1-2 µm). This testing method is non-destructive but would still require multiple scans around hole perimeter and is rather used for more accessible open cut trimmed edges [

32].

In addition, grain shear angle results may be translated to physically relevant failure strain parameters [

1,

23,

38], while conversion of Vickers hardness values into material properties is less direct [

23,

41]. These results stated that grain shear angle measurement should be the preferred choice when it comes to metallographic SAZ investigations of materials with a high tendency to strain localization, as AHSS with UTS>1000 MPa. An additional benefit of this method is the automation possibility using image analysis and measurements with similar methodologies as used in [

42].

To meet Industry 4.0 demands, there is a growing need for stringent in-line monitoring of cut edge parameters and overall edge quality, especially for materials with tensile strengths of 800 MPa and above. For such high-strength materials, the relationship between cut edge quality and forming characteristics, such as stretch flangeability, sensitivity to hydrogen embrittlement, as well as low- and high-cycle fatigue performance, is crucial. The optical testing methods presented are already part of a comprehensive database linking edge crack sensitivity to cut edge conditions. To this topic, so-called 2.5D optical photometric stereo technology is on the rise for industrial tool wear monitoring for example [

43]. This is an extension of the 3D Keyence technique presented in this paper. Internal work is also pursued in this direction based on a own patented shape from shading reconstruction technique with multiple sequential lightning at different known angles of a fixed sample and camera [

44]. Additionally, Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning techniques are increasingly used to model hole expansion ability in relation to cut edge quality, addressing the numerous parameters and complex interactions between cut edge and material properties [

45,

46]. When combined with ML algorithms or other AI applications, this in-line monitoring can effectively prevent downstream production issues, thus reducing scrap in production of lightweight AHSS components.

Figure 1.

Cut edge cross section showing two kinds of characteristic cut edge profiles.

Figure 1.

Cut edge cross section showing two kinds of characteristic cut edge profiles.

Figure 2.

Low/high magnification 2D/3D microscopy and metallographic cross sections of closed cut edges of AHSS sheets, showing formation of secondary burnish (left) and burr formation as well as rough fracture surface (right)

Figure 2.

Low/high magnification 2D/3D microscopy and metallographic cross sections of closed cut edges of AHSS sheets, showing formation of secondary burnish (left) and burr formation as well as rough fracture surface (right)

Figure 3.

Panoramic cut edges of open cut configurations using conventional cut edge investigation techniques, showing secondary burnish formation as well as full and partial burr formation of AHSS sheets.

Figure 3.

Panoramic cut edges of open cut configurations using conventional cut edge investigation techniques, showing secondary burnish formation as well as full and partial burr formation of AHSS sheets.

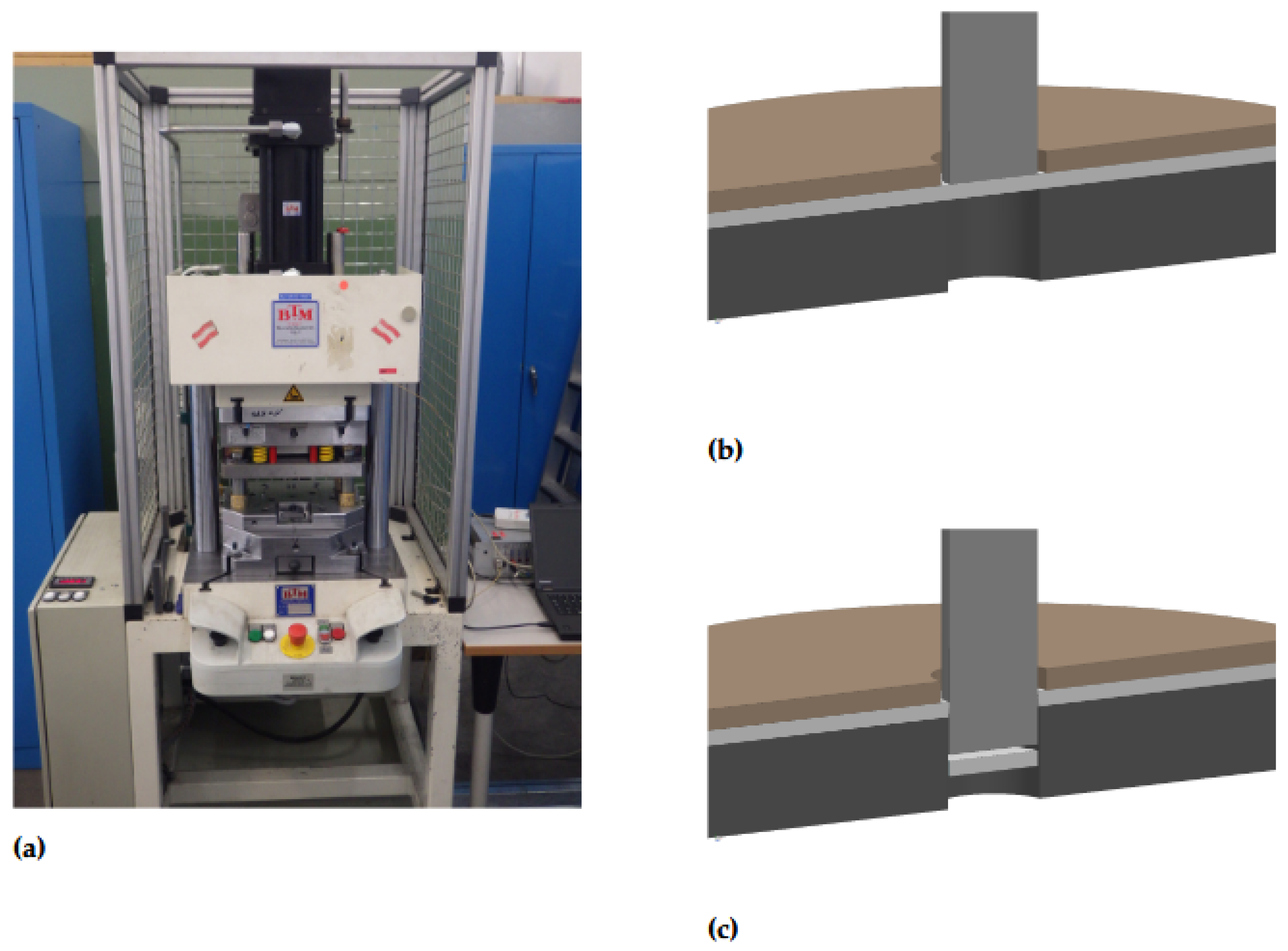

Figure 4.

In (a) the servo-hydraulic machine equipped with an ISO16630 dedicated hole punching tool. In (b) a schematic image of initial cutting configuration and in (c) a schematic image of finalized cutting.

Figure 4.

In (a) the servo-hydraulic machine equipped with an ISO16630 dedicated hole punching tool. In (b) a schematic image of initial cutting configuration and in (c) a schematic image of finalized cutting.

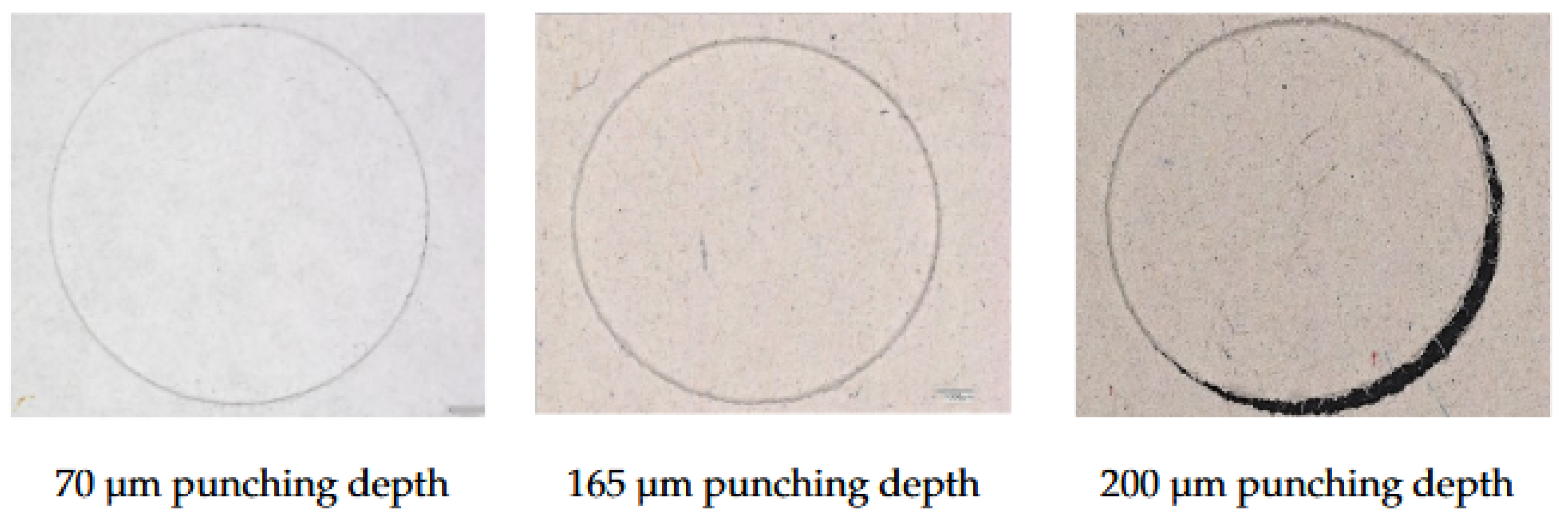

Figure 5.

Coaxiality test by paper punching, which shows the punch imprint at increasing punch displacement and a slight non-coaxiality through uneven cutting depth at 200 µm punch displacement.

Figure 5.

Coaxiality test by paper punching, which shows the punch imprint at increasing punch displacement and a slight non-coaxiality through uneven cutting depth at 200 µm punch displacement.

Figure 6.

Conventional cut edge investigation by (a) using x40-50 magnification USB digital microscope for qualitative cut edge and tools investigations and (b) metallographic cross section for cutting clearance determination.

Figure 6.

Conventional cut edge investigation by (a) using x40-50 magnification USB digital microscope for qualitative cut edge and tools investigations and (b) metallographic cross section for cutting clearance determination.

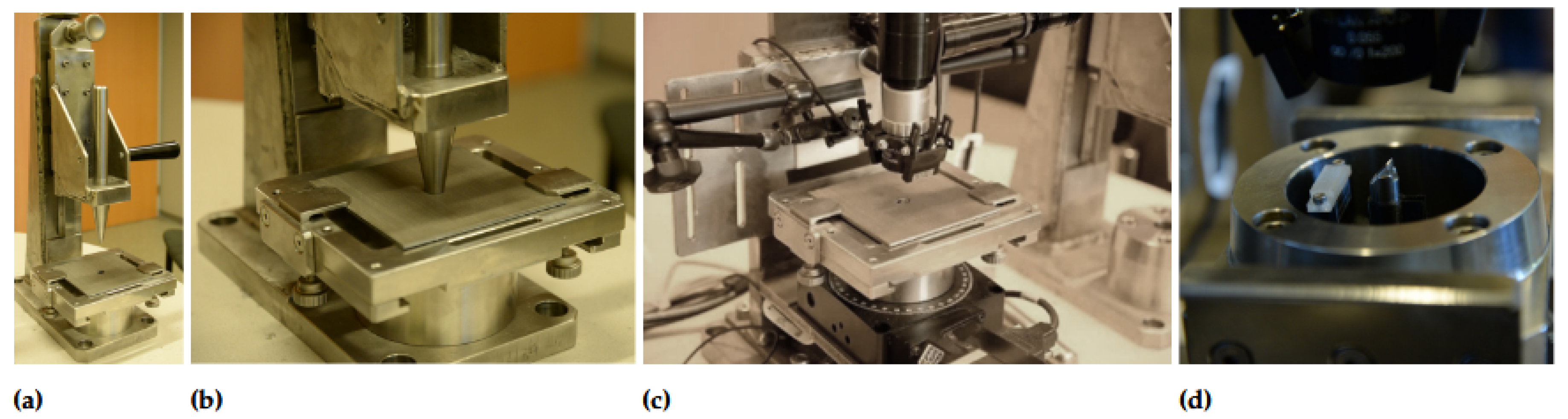

Figure 7.

The Edge Inspection System (EISYS) test set up, showing the pre-centring device in (a) and (b) used for positioning the punched sample. (c) shows the rotation table and (d) mirror at hole center.

Figure 7.

The Edge Inspection System (EISYS) test set up, showing the pre-centring device in (a) and (b) used for positioning the punched sample. (c) shows the rotation table and (d) mirror at hole center.

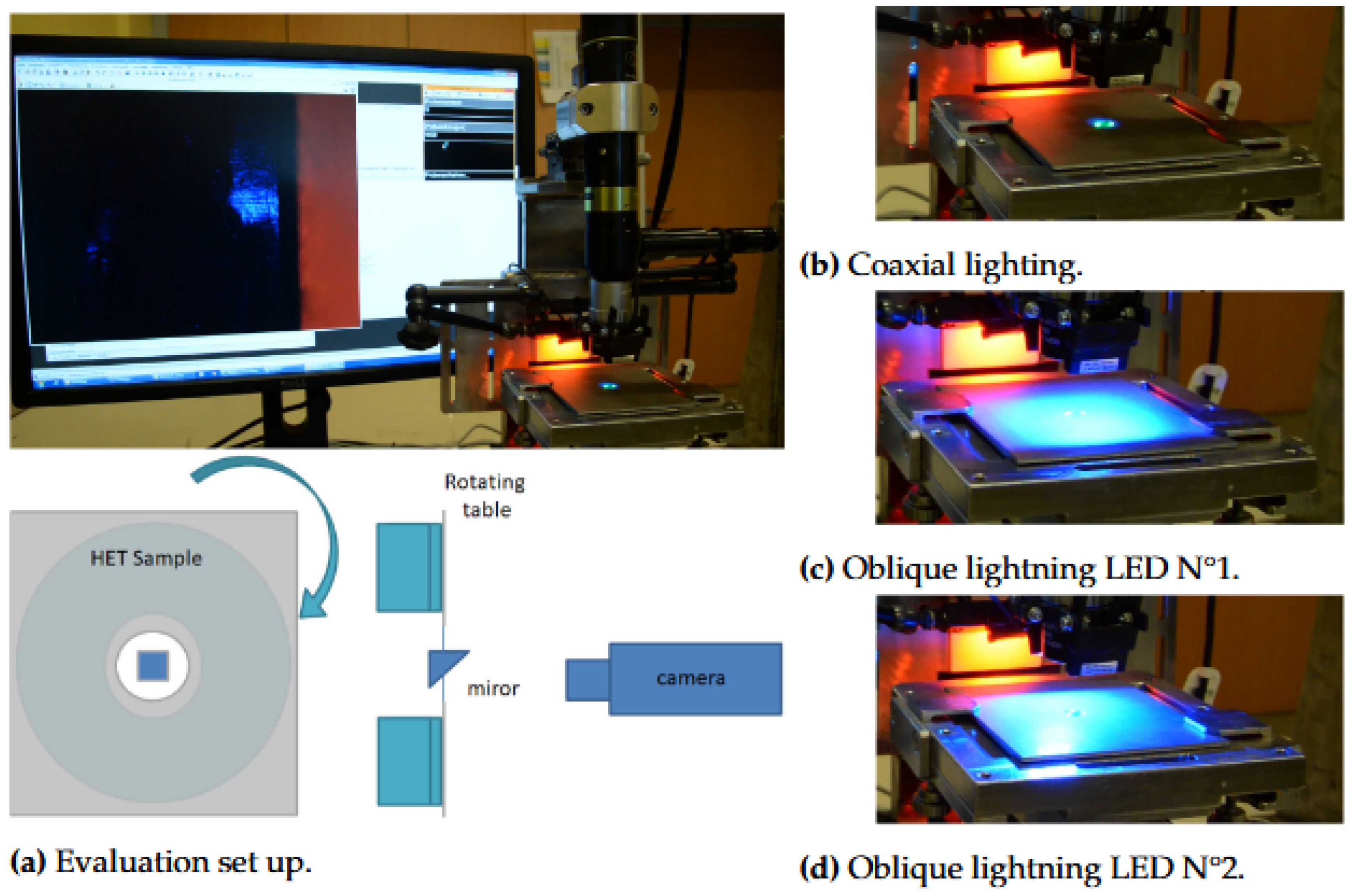

Figure 8.

The Edge Inspection System (EISYS) test set up in (a), showing the digitalization of the cut edge using the lightning concepts in (b)-(d).

Figure 8.

The Edge Inspection System (EISYS) test set up in (a), showing the digitalization of the cut edge using the lightning concepts in (b)-(d).

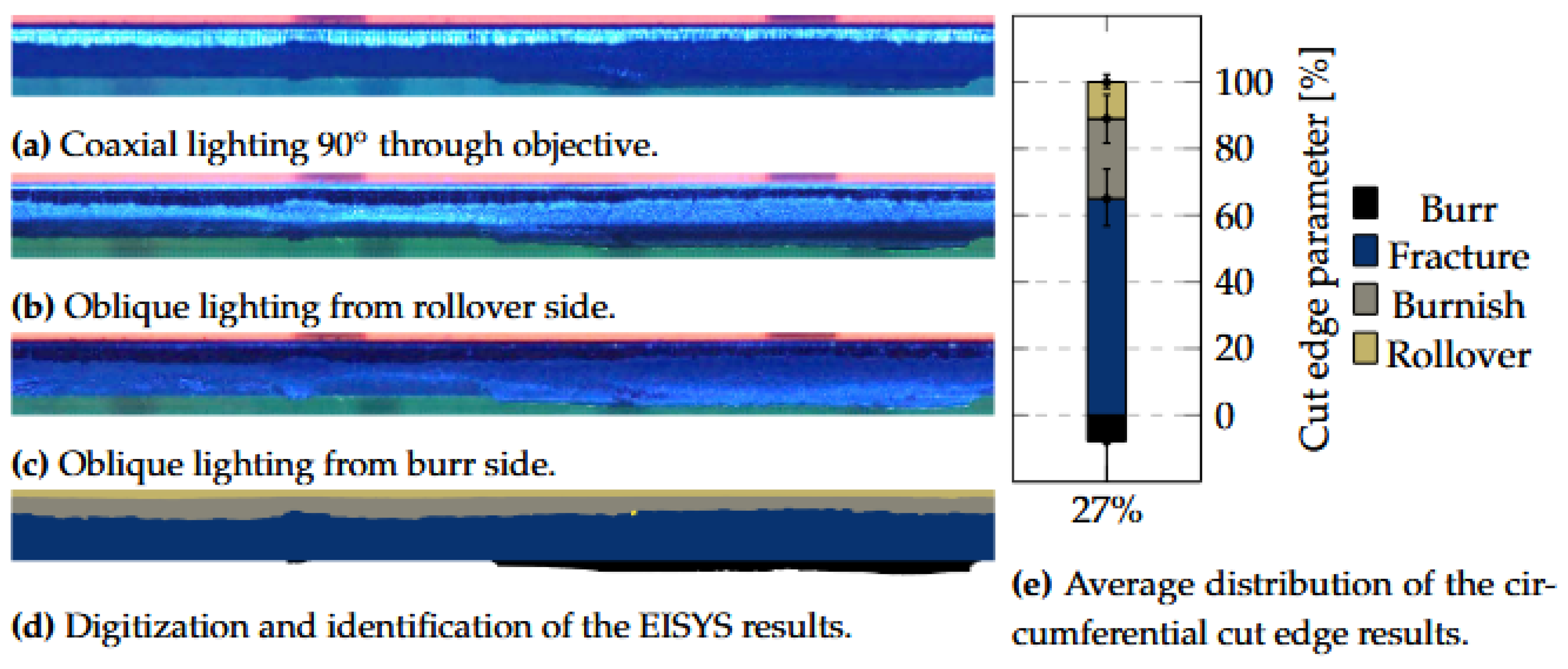

Figure 9.

panorama picture and cut edge parameter identification for 27% cutting clearance. After applying the EISYS approach, the panoramic images with varying lighting concepts in (a)-(c) were digitalized in (d). This enabled computation of the average distribution of the circumferential cut edge results in (e), along with the circumferential variation (standard deviation) as error bars.

Figure 9.

panorama picture and cut edge parameter identification for 27% cutting clearance. After applying the EISYS approach, the panoramic images with varying lighting concepts in (a)-(c) were digitalized in (d). This enabled computation of the average distribution of the circumferential cut edge results in (e), along with the circumferential variation (standard deviation) as error bars.

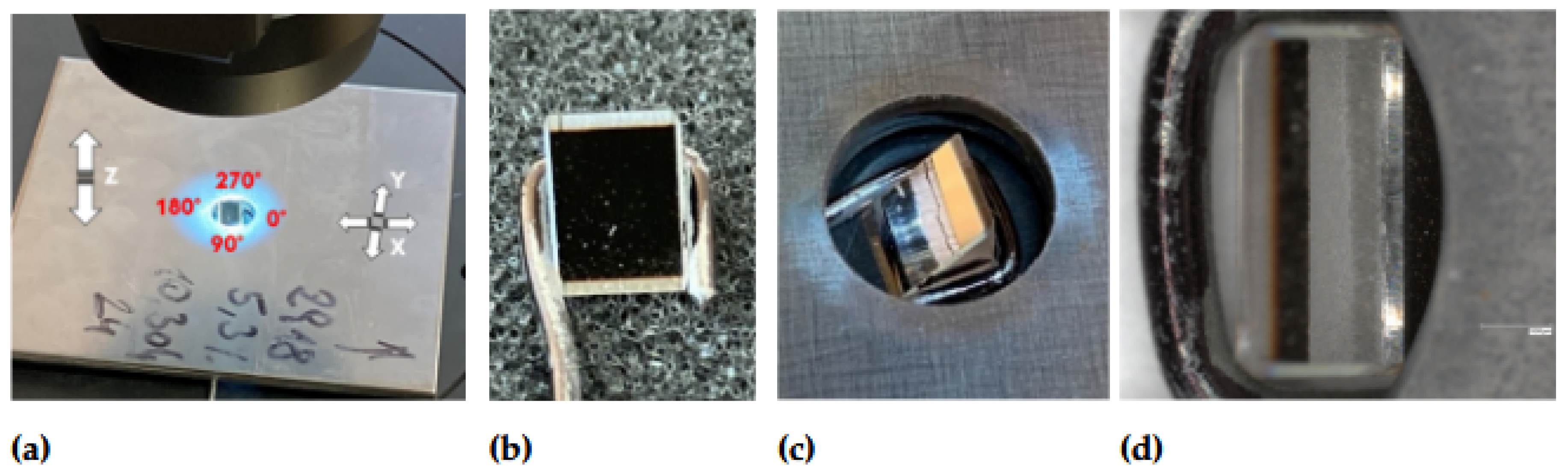

Figure 10.

The setup and and ingoing components used for the 45° mirror technique for stereo 3D microscopy. (a) shows the punched sample and the microscopy positioning, while (b) shows the 45° mirror and in (c) its placement in the punched sample. (d) shows the 45° view of the burnish- fracture edge profile during experimental investigation.

Figure 10.

The setup and and ingoing components used for the 45° mirror technique for stereo 3D microscopy. (a) shows the punched sample and the microscopy positioning, while (b) shows the 45° mirror and in (c) its placement in the punched sample. (d) shows the 45° view of the burnish- fracture edge profile during experimental investigation.

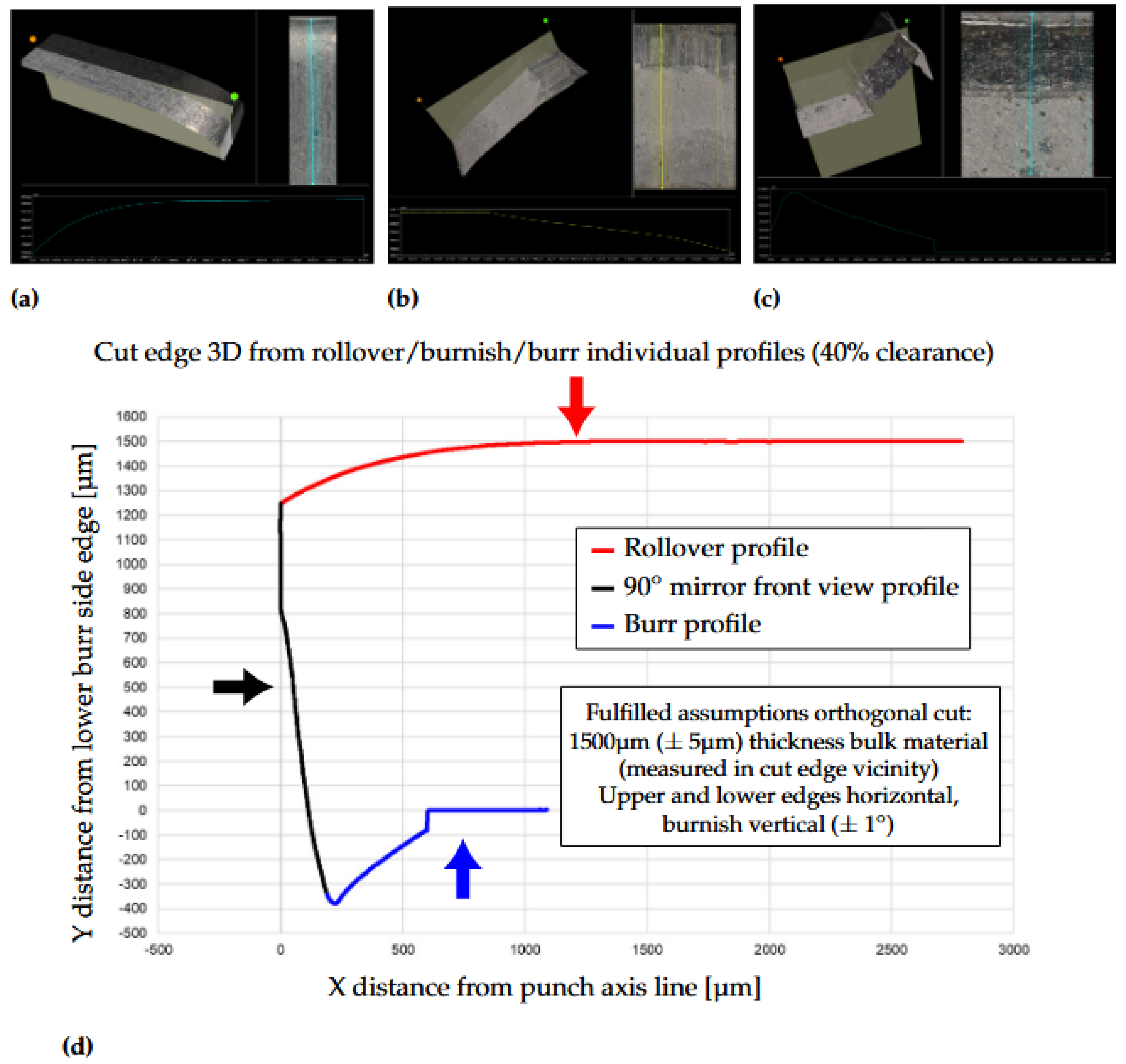

Figure 11.

In (a) the creation of rollover profile at the upper sample side. In (b) is the mirrored burnish-fracture profile of the cut edge front view and in (c) is the burr profile from the lower sample side. (d) shows the whole cut edge profile built by combining the individual top, down and front views.

Figure 11.

In (a) the creation of rollover profile at the upper sample side. In (b) is the mirrored burnish-fracture profile of the cut edge front view and in (c) is the burr profile from the lower sample side. (d) shows the whole cut edge profile built by combining the individual top, down and front views.

Figure 12.

The definitions of the fracture angles from (a) no burr condition, (b) with burr formation and in (c) with secondary burnish formation.

Figure 12.

The definitions of the fracture angles from (a) no burr condition, (b) with burr formation and in (c) with secondary burnish formation.

Figure 13.

The parallel indentation tracks used for Vickers hardness measurements of the 12% cutting clearance cut edge.

Figure 13.

The parallel indentation tracks used for Vickers hardness measurements of the 12% cutting clearance cut edge.

Figure 14.

The grain shear angle paths for the 12% cutting clearance cross section and the definition of the grain shear angle calculation along one of the defined paths. In (a) the etched cross section of a 12% cutting clearance cut edge, where six paths are highlighted with red lines along which the grain shear angles are determined. The red points show the measurement points where grain shear angle measurements were performed. In (b) a schematic image of the grain shear angle measurement following the burnish center path (red line) for the 12% cutting clearance cross section

Figure 14.

The grain shear angle paths for the 12% cutting clearance cross section and the definition of the grain shear angle calculation along one of the defined paths. In (a) the etched cross section of a 12% cutting clearance cut edge, where six paths are highlighted with red lines along which the grain shear angles are determined. The red points show the measurement points where grain shear angle measurements were performed. In (b) a schematic image of the grain shear angle measurement following the burnish center path (red line) for the 12% cutting clearance cross section

Figure 15.

A schematic image of grain shear angle results, where the scatter points represent the measured grain shear angles along an arbitrary path and the linear curves ( and ) show the linear fitting for distinguishing between localized shear deformation and global bending. The point shows the x-coordinate where the curves intersect, thus the width of the localized SAZ, the point of shows the critical angle at fracture and the point states the width of the total shear affected zone.

Figure 15.

A schematic image of grain shear angle results, where the scatter points represent the measured grain shear angles along an arbitrary path and the linear curves ( and ) show the linear fitting for distinguishing between localized shear deformation and global bending. The point shows the x-coordinate where the curves intersect, thus the width of the localized SAZ, the point of shows the critical angle at fracture and the point states the width of the total shear affected zone.

Figure 16.

Experimental cut edge profiles for different cutting clearances (Cl). The cut edge profiles were determined at , , and around the punched hole circumference. For 27%, additional cut edge profiles were extracted for providing information at no-burr and burr sections.

Figure 16.

Experimental cut edge profiles for different cutting clearances (Cl). The cut edge profiles were determined at , , and around the punched hole circumference. For 27%, additional cut edge profiles were extracted for providing information at no-burr and burr sections.

Figure 17.

Variation of cut edge profile at different positions along the hole perimeter produced by 5% cutting clearance. Each curve was extracted within degrees from the assigned position.

Figure 17.

Variation of cut edge profile at different positions along the hole perimeter produced by 5% cutting clearance. Each curve was extracted within degrees from the assigned position.

Figure 18.

Comparison of the cut edge profiles from the non-destructive 3D optical cut edge methodology (green lines) to destructive metallographic cut edge cross sections (images).

Figure 18.

Comparison of the cut edge profiles from the non-destructive 3D optical cut edge methodology (green lines) to destructive metallographic cut edge cross sections (images).

Figure 19.

Comparison between the 2D optical EISYS methodology and the metallographic cut edge cross sections, longitudinal to the rolling direction. The outer blank perimeters and the transition between the characteristic cut edge parameters are highlighted with red dashed lines.

Figure 19.

Comparison between the 2D optical EISYS methodology and the metallographic cut edge cross sections, longitudinal to the rolling direction. The outer blank perimeters and the transition between the characteristic cut edge parameters are highlighted with red dashed lines.

Figure 20.

Cut edge parameters versus cutting clearance, determined through the EISYS technique presented in

Section 2.2.1.

Figure 20.

Cut edge parameters versus cutting clearance, determined through the EISYS technique presented in

Section 2.2.1.

Figure 21.

Fracture angle measurements for varying cutting clearance at different positions around the hole perimeter.

Figure 21.

Fracture angle measurements for varying cutting clearance at different positions around the hole perimeter.

Figure 22.

Vickers hardness indentation results () plotted for each cutting clearance versus normalized distance from cut edge, combining three horizontal cut edge cross sections paths.

Figure 22.

Vickers hardness indentation results () plotted for each cutting clearance versus normalized distance from cut edge, combining three horizontal cut edge cross sections paths.

Figure 23.

Combined grain shear angle results from six extraction paths for 5%, 12%, 20% and 27% cutting clearances versus normalized cut edge distance.

Figure 23.

Combined grain shear angle results from six extraction paths for 5%, 12%, 20% and 27% cutting clearances versus normalized cut edge distance.

Figure 24.

Comparison between Vickers hardness (right vertical axis) and grain shear angle (left vertical axis) experimental results versus normalized cut edge distance for 12% cutting clearance.

Figure 24.

Comparison between Vickers hardness (right vertical axis) and grain shear angle (left vertical axis) experimental results versus normalized cut edge distance for 12% cutting clearance.

Figure 25.

Grain shear angle measurements for each individual path versus cut edge distance for 12% cutting clearance.

Figure 25.

Grain shear angle measurements for each individual path versus cut edge distance for 12% cutting clearance.

Table 1.

Mechanical tensile properties in different material directions relative to the rolling direction (RD) for CP1000HD with a thickness of mm, yield strength (), tensile strength (), uniform elongation (), total elongation () for 80 mm gauge length, n-value at uniform elongation () and r-value determined at 4% elongation ().

Table 1.

Mechanical tensile properties in different material directions relative to the rolling direction (RD) for CP1000HD with a thickness of mm, yield strength (), tensile strength (), uniform elongation (), total elongation () for 80 mm gauge length, n-value at uniform elongation () and r-value determined at 4% elongation ().

| RD |

[MPa] |

[MPa] |

[%] |

[%] |

[-] |

[-] |

|

893 |

1052 |

7.3 |

11.1 |

0.071 |

0.91 |

|

905 |

1052 |

7.0 |

10.6 |

0.068 |

1.02 |

|

909 |

1062 |

7.1 |

10.7 |

0.068 |

0.96 |

Table 2.

The geometric hole punching parameters used in experiments for clearances (Cl) 5-40%, where is the die diameter, is the punch diameter, is the die edge radius, is the punch edge radius and is the blank thickness.

Table 2.

The geometric hole punching parameters used in experiments for clearances (Cl) 5-40%, where is the die diameter, is the punch diameter, is the die edge radius, is the punch edge radius and is the blank thickness.

| Cl [%] |

5.3 |

8.5 |

10.5 |

12.1 |

17.1 |

20.5 |

23.8 |

27.0 |

33.7 |

40.3 |

|

[mm] |

10.16 |

10.25 |

10.31 |

10.36 |

10.51 |

10.61 |

10.71 |

10.81 |

11.01 |

11.21 |

|

[mm] |

9.998 |

|

[µm] |

30 |

|

[µm] |

30 |

|

[mm] |

1.5 |