This systematic review aimed to evaluate whether co-supplementation with creatine and β-alanine provides greater improvements in exercise performance and body composition compared to either supplement alone. The findings from RCTs suggest that co-supplementation is an effective strategy for enhancing certain performance outcomes, particularly strength and high-intensity power output, and for augmenting lean mass gains induced by training. However, these benefits appear to be primarily driven by the well-established ergogenic effects of creatine. True synergistic effects—where the combination of creatine and β-alanine leads to performance enhancements beyond what either supplement achieves alone—were observed more frequently in anaerobic power and high-intensity performance, with lower probability of additive effects in maximal strength and body composition.

4.1. Strength and Power

It is well established that creatine supplementation enhances strength and power, and all RCTs reviewed in this study confirmed that groups receiving creatine (either alone or in combination) exhibited substantial improvements in strength and anaerobic power relative to placebo [

6,

7]. These findings are consistent with decades of research demonstrating that creatine is one of the most effective supplements for increasing muscular strength, primarily by enhancing training capacity, phosphocreatine resynthesis, and neuromuscular function.

One of the primary mechanisms by which β-alanine is hypothesized to enhance strength and power performance is through its buffering effect on intramuscular acidity. The accumulation of H⁺ during high-intensity exercise has been shown to impair phosphocreatine resynthesis [

11], inhibit glycolytic metabolism [

12], and negatively affect muscle contractile function. Thus, it is theoretically plausible that combining creatine with β-alanine could provide additional benefits by simultaneously supporting ATP production (creatine) and buffering metabolic acidosis (β-alanine). However, the question remains whether this combination meaningfully enhances strength and power outcomes beyond what creatine alone achieves.

The evidence from RCTs suggests that any additional benefit of β-alanine in maximal strength gains is minimal. Hoffman et al. found no significant differences in 1RM strength gains (bench press and squat) between the creatine-only and creatine + β-alanine groups, indicating that β-alanine did not further enhance maximal strength beyond the effects of creatine [

6]. Other studies that assessed strength outcomes similarly reported that creatine alone was superior to placebo, but did not specifically compare creatine-only vs. creatine + β-alanine for 1RM gains. These results suggest that creatine’s mechanism (increasing phosphocreatine availability) is already sufficient to maximize strength adaptations in a resistance training context, and that additional buffering from β-alanine does not provide a substantial advantage for maximal strength performance.

In contrast, β-alanine may offer greater benefits in scenarios where repeated maximal efforts are required, such as high-intensity interval training, sprinting, or repeated sets of resistance exercise. This is evident in studies where muscle acidosis is a key limiting factor. For example, Okudan et al. examined repeated Wingate sprint performance in untrained men and found that while creatine improved peak power, only the groups receiving β-alanine (β-alanine alone or β-alanine + creatine) were able to sustain power output across multiple sprints and resist fatigue [

9]. This suggests that β-alanine’s buffering effect translated into reduced performance decrements over successive high-intensity efforts, whereas creatine alone was primarily effective for increasing peak power output. The physiological basis for this synergy is logical: Creatine supplementation enhances ATP-PCr system efficiency, providing energy for short-duration, high-intensity efforts. β-Alanine, via its role in carnosine synthesis, buffers H⁺ accumulation, mitigating the decline in PH associated with anaerobic glycolysis and thereby delaying fatigue in subsequent efforts. This complementary interaction likely explains why β-alanine’s effects are more apparent in repeated-bout performance rather than in single maximal lifts (e.g., 1RM strength testing).

A recent study by Li et al. (2025) in competitive male basketball players provides further insights into the potential benefits of co-supplementation for explosive performance. This 4-week RCT included placebo, creatine-only, β-alanine-only, L-citrulline-only, or a combination of all three supplements, alongside a sprint interval training program [

13]. The study reported that all supplement groups outperformed placebo in physical performance tests (e.g., vertical jump, 20-m sprint, and change-of-direction speed), and that the combination of multiple supplements provided the broadest performance enhancements. However, because the co-supplementation group in this study included L-citrulline, these results were not included in the current systematic review due to the predefined inclusion criteria.

Despite this limitation, the findings reinforce that creatine and β-alanine—either alone or in combination—are beneficial for power-related outcomes. Additionally, no negative interactions were observed between multiple supplements, suggesting that co-supplementation strategies may provide broad ergogenic benefits without interference.

It is important to note that not all studies demonstrated a clear differentiation in the roles of creatine and β-alanine. For instance, in Kresta et al.'s study on female participants, even repeated Wingate tests did not reveal a distinct advantage of co-supplementation over single-supplement conditions [

3]. Several factors may contribute to these findings. One potential explanation is the influence of training status and sex-related differences. The female participants in Kresta’s study, despite being recreationally active, likely had lower baseline power outputs and muscle mass compared to male athletes. Consequently, the absolute physiological stress and accumulation of metabolic byproducts (e.g., hydrogen ions) during repeated sprints may have been lower, reducing the potential ergogenic effects of β-alanine. Additionally, the dosing strategy (relative to body weight) and the supplementation duration (4 weeks) may have been insufficient for smaller female participants to achieve a meaningful increase in muscle carnosine levels, thereby limiting the impact of β-alanine on performance.

Another relevant consideration is that creatine’s effects on lean mass and power output in women are often less pronounced than in men, potentially due to hormonal differences, muscle fiber composition, or lower total muscle creatine stores [

3]. Moreover, Kresta et al. incorporated concurrent endurance training across all study groups, which may have attenuated strength and power adaptations and masked potential supplement effects. This contrasts with Okudan et al.'s study in untrained men, which specifically targeted anaerobic performance (Wingate sprint tests) without endurance training [

9]. The differences in training modality and population characteristics suggest that the presence of synergy between creatine and β-alanine may be more evident in anaerobic-focused interventions (e.g., Okudan et al.) but less pronounced in endurance-based or mixed-training contexts (e.g., Kresta et al.).

Another possible reason for inconsistent findings is the presence of ceiling effects [

14]. In highly trained populations, such as Hoffman et al.'s collegiate football players, substantial improvements in strength and power are already achieved through training and creatine supplementation alone. In such cases, β-alanine’s ability to further enhance performance may be limited, particularly over a relatively short intervention period (e.g., 10 weeks), where creatine and structured training have already maximized neuromuscular adaptations.

Conversely, in less-trained individuals, the potential for improvement may be greater, and a supplement that allows for even marginal increases in training capacity (e.g., an additional repetition or a slight delay in fatigue) could lead to measurable performance differences. This may explain why β-alanine's effects were more evident in studies involving untrained participants engaging in repeated high-intensity efforts but less pronounced in well-trained athletes undergoing structured resistance training.

The cumulative evidence from RCTs indicates that co-supplementation with creatine and β-alanine enhances strength and power performance relative to placebo, particularly when combined with structured training programs. However, these improvements are primarily attributed to creatine’s well-established effects on muscular strength and power output. In settings where creatine alone already optimizes neuromuscular performance, β-alanine does not appear to provide additional benefits for maximal strength (e.g., 1RM gains). However, β-alanine may offer advantages in high-intensity, repeated-effort scenarios, where it can delay fatigue and sustain power output over successive efforts.

From a practical standpoint, athletes engaged in strength and power training can expect substantial performance enhancements from creatine alone. Adding β-alanine may be beneficial in scenarios requiring sustained power output over multiple sets or repeated bouts of high-intensity exercise, but its contribution to absolute strength gains appears to be minimal. Future research should explore the long-term effects of co-supplementation across different training populations, with a particular focus on sex-based differences, training status, and sport-specific demands.

4.2. Endurance and High-Intensity Exercise Capacity

The findings of this review provide limited evidence supporting the efficacy of co-supplementation with creatine and β-alanine in enhancing traditional endurance performance metrics, such as VO₂max or prolonged aerobic exercise capacity, beyond the effects of training alone. This outcome is expected, as creatine supplementation does not inherently improve oxidative metabolism and may even be detrimental to endurance performance if it leads to rapid weight gain without direct benefits to aerobic energy production [

15]. Conversely, β-alanine’s primary ergogenic role is observed in high-intensity exercise lasting approximately 1–4 minutes, such as an 800–1500 m run or a 1000 m rowing effort, rather than in prolonged endurance events such as marathons [

16]. The current body of evidence confirms that VO₂max remains unaffected by β-alanine or creatine supplementation [

3,

5]. However, for efforts occurring at the metabolic "crossover" between anaerobic and aerobic energy systems, there is some indication of potential benefit. Stout et al. reported that β-alanine supplementation increased the PWCFT, suggesting an improvement in fatigue resistance [

8]. However, the addition of creatine did not further amplify this effect, indicating that β-alanine alone was responsible for the observed improvements. Similarly, Zoeller et al. reported modest improvements in TTE at high intensity in the combined supplementation group, though these improvements were not significantly greater than those observed with β-alanine alone [

5]. These findings suggest that β-alanine may provide a slight advantage in events involving sustained high-intensity efforts, such as 2–3-minute maximal exertion bouts or sports requiring repeated bursts of high-intensity activity (e.g., boxing rounds, middle-distance track races, or 100–200 m swimming sprints). However, direct evidence from studies specifically targeting such performance scenarios remains lacking.

The findings from Li et al. in competitive basketball players further support the limited impact of co-supplementation on aerobic endurance [

13]. In this 4-week study, athletes received creatine, β-alanine, a combination of both, or an additional L-citrulline supplementation regimen alongside their training program. Aerobic fitness was assessed (likely via a shuttle run or VO₂max test), and while all groups improved due to training, the supplemented groups (including the combined group) outperformed placebo in general. However, the co-supplementation group did not demonstrate a clear advantage over the single-supplement groups for aerobic performance, suggesting that creatine and β-alanine do not synergistically enhance aerobic endurance when combined.

Another intriguing finding comes from Samadi et al., who observed improved cognitive performance (measured via mathematical processing tasks) in participants receiving β-alanine + creatine supplementation [

7]. Given that creatine is well-documented to support cognitive function, particularly in sleep-deprived or hypoxic conditions, and that β-alanine may mitigate central fatigue contributors, the combined supplementation may offer benefits for maintaining cognitive performance under conditions of physical and mental stress. This finding has potential practical applications for military personnel, endurance athletes, and individuals performing high-cognitive-demand tasks under fatigue, warranting further investigation into the neuromuscular and cognitive effects of co-supplementation.

Overall, the current RCT evidence does not strongly support a meaningful synergistic effect of combined creatine and β-alanine on traditional endurance performance. While β-alanine has demonstrated efficacy in delaying fatigue by improving work at fatigue threshold and extending time-to-exhaustion, co-supplementation with creatine has not consistently yielded additive benefits in VO₂max, lactate threshold, or exercise duration to fatigue beyond what β-alanine or endurance training alone can achieve. Creatine supplementation, on its own, has minimal direct impact on classical endurance metrics and does not appear to synergize with β-alanine for these outcomes. There is some evidence that combined supplementation may slightly improve high-intensity endurance thresholds and capacity, but such effects have been inconsistent across studies and generally not statistically superior to single-supplement interventions.

From a practical standpoint, endurance athletes are unlikely to derive substantial additional benefits from creatine + β-alanine supplementation beyond those obtained through structured endurance training alone. However, individuals engaged in mixed metabolic events (e.g., high-intensity interval training, combat sports, middle-distance races, or team sports requiring repeated sprint efforts) may experience minor improvements in high-intensity endurance capacity with β-alanine alone, although the contribution of creatine in this context remains limited. Future research should explore the effects of co-supplementation in sport-specific endurance applications, particularly in hybrid aerobic-anaerobic sports where sustained high-intensity efforts play a critical role in performance outcomes.

4.3. Body Composition

Creatine supplementation is well established for its role in increasing LBM, primarily through enhanced intracellular water retention, improved strength, and greater progressive overload during resistance training. In contrast, β-alanine’s potential effects on body composition are more indirect, hypothesized to occur through increased training volume and higher-intensity efforts, leading to greater hypertrophic adaptation. The proposed synergy between these two supplements is that creatine enhances maximal strength, while β-alanine delays fatigue, allowing for a higher training volume—thereby providing both a heavier and a slightly prolonged training stimulus.

Findings from this review suggest that co-supplementation with creatine and β-alanine may enhance body composition adaptations, as observed in Hoffman et al.’s 10-week study, where the creatine + β-alanine group gained approximately 1 kg more lean mass than the creatine-only group and also experienced greater reductions in body fat [

6]. These results suggest a potential recomposition effect, where greater muscle mass is accrued without additional fat gain. For athletes, this could imply an improved lean mass-to-fat ratio over a training cycle, thereby optimizing performance and body composition simultaneously.

The underlying mechanism by which β-alanine might contribute to these improvements remains speculative. One hypothesis is that β-alanine’s buffering effect on muscle acidosis allows athletes to sustain higher training volumes or intensities over time, resulting in greater hypertrophic stimulus and potentially increased caloric expenditure [

17]. If an athlete can perform additional repetitions before muscular failure or execute high-intensity intervals at a slightly higher power output, these incremental training improvements may accumulate over several weeks, contributing to enhanced lean mass gains and fat loss. Supporting this theory, previous studies have reported that β-alanine supplementation improved training volume in resistance exercise and promoted lean mass gains when combined with high-intensity interval training (HIIT).

Notably, Hoffman et al. observed higher weekly training volume in the squat exercise in the creatine + β-alanine group, potentially explaining the higher lean mass gains in this cohort. However, it is important to acknowledge that not all studies have observed this effect, as some research has failed to find a significant impact of β-alanine on training volume [

18,

19]. Furthermore, Hoffman et al.’s study design did not include a β-alanine–only group, making it difficult to determine whether the observed benefits were due to a true synergistic effect or simply a larger effect of creatine alone.

Not all studies have demonstrated a significant benefit of co-supplementation with creatine and β-alanine on body composition. A particularly notable finding is the null results reported by Kresta et al., who found that the combination of creatine and β-alanine was not superior to either supplement alone in terms of lean mass or fat mass changes [

3]. Several factors may explain these findings, including shorter study duration, lower relative dosage per body weight, and potential sex-specific differences in physiological responses.

Kresta et al. noted that females generally experience smaller increases in lean mass following creatine supplementation compared to males, a trend that was evident in their study, where the creatine-only group exhibited smaller lean mass gains than those typically observed in male-based studies. When juxtaposed with Hoffman et al.’s findings in male participants, it appears plausible that creatine primarily supports muscle energetics, while β-alanine may facilitate greater training volume and quality, potentially maximizing hypertrophic adaptations over time. However, given that Hoffman et al. is the only study to report a significant synergistic effect of co-supplementation on lean mass, these findings should be interpreted with caution.

Some studies suggest that women do not gain as much muscle mass or retain as much water from creatine supplementation as men, potentially due to lower absolute muscle mass, greater baseline intramuscular creatine stores, or hormonal differences [

20,

21]. For example, a meta-analysis by Pashayee-Khamene et al. reported that men gained more than twice the amount of lean mass compared to women following creatine supplementation (1.2 kg vs. 0.54 kg)[

2].

Additionally, study duration may have influenced the observed outcomes. While Hoffman et al. (2006) conducted a 10-week trial, which allowed for more cumulative training adaptations, Kresta et al.’s study lasted only 4 weeks, which may have been insufficient to detect meaningful differences in body composition.

Another important factor is statistical power. Hoffman et al. included 33 participants, and even with this sample size, the between-group differences were only barely significant (p < 0.05). In contrast, Kresta et al. divided 32 participants across four groups (~8 per group), significantly reducing statistical power. As a result, the study may have been underpowered to detect modest but potentially meaningful effects of supplementation.

A meta-analysis of 20 RCTs by Ashtary-Larky et al. concluded that, regardless of exercise program, supplementation dose, or study duration, β-alanine supplementation does not significantly increase lean mass or reduce fat mass. This suggests that β-alanine does not have a direct impact on muscle hypertrophy, and that the hypertrophic effects observed in creatine + β-alanine co-supplementation studies are primarily attributable to creatine.

Thus, existing evidence does not strongly support the hypothesis that β-alanine enhances the body composition benefits of creatine supplementation. The observed improvements in lean mass in some studies may simply reflect creatine’s well-established role in improving muscle energetics and increasing training capacity, rather than a true synergistic effect with β-alanine.

The current body of evidence regarding the benefits of co-supplementation with creatine and β-alanine for body composition remains limited and inconclusive. Given that previous research has not demonstrated a significant effect of β-alanine on lean mass or fat loss, it is unlikely that β-alanine enhances the body composition benefits of creatine supplementation.

Future studies should focus on longer-duration trials with larger sample sizes to determine whether β-alanine contributes to hypertrophic adaptations when combined with creatine. Additionally, research should explore sex-specific responses and variations in training protocols, as current findings suggest that the potential benefits of co-supplementation may be population-dependent.

In practical terms, athletes seeking to optimize muscle hypertrophy and body composition should prioritize creatine supplementation, as its effects on lean mass and strength are well established. While β-alanine may provide ergogenic benefits for sustained high-intensity efforts, its direct role in body composition improvements remains uncertain. Future research is necessary to clarify whether co-supplementation provides advantages over creatine alone, particularly in specific athletic populations or training contexts.

4.4. Limitations

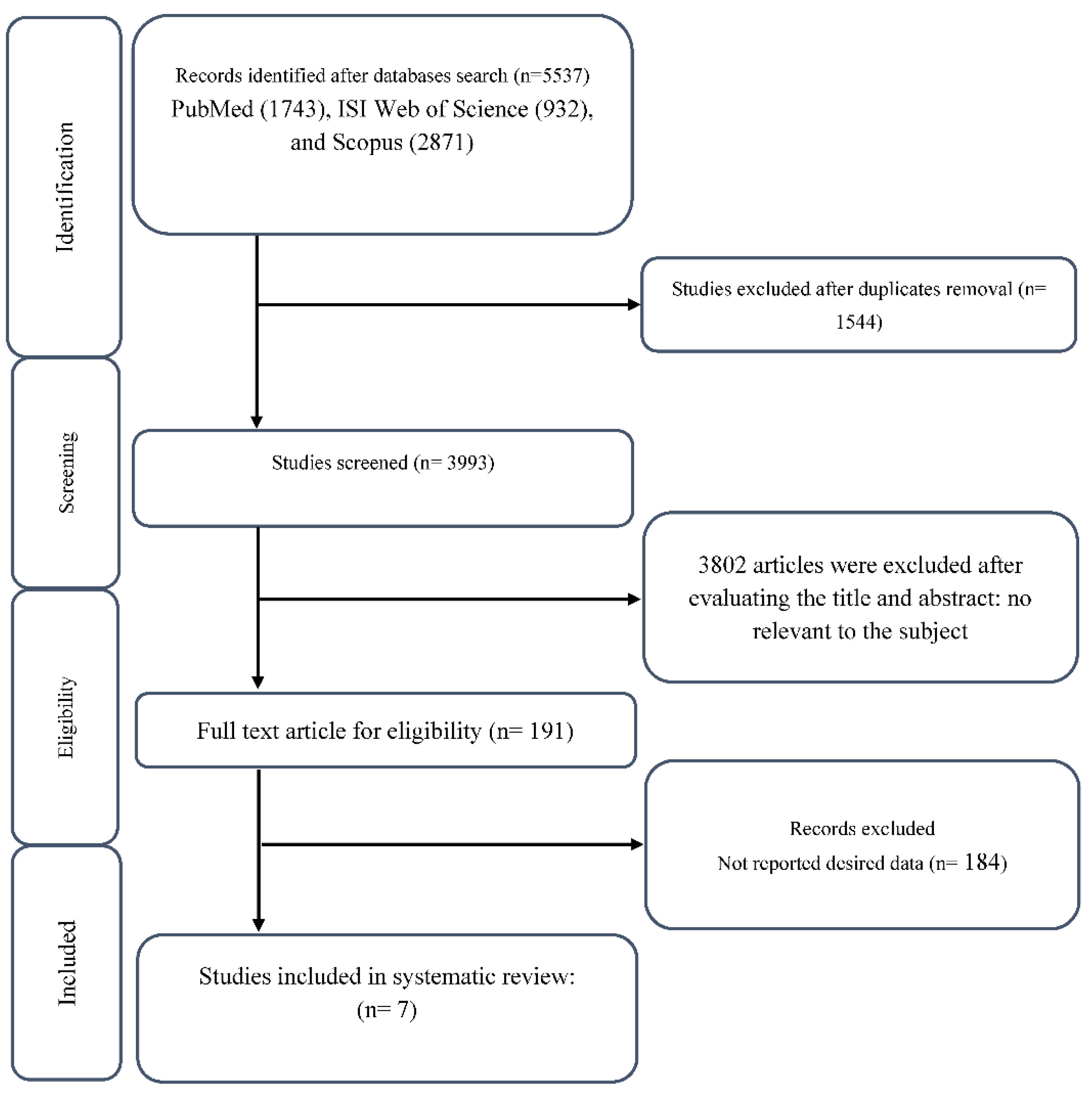

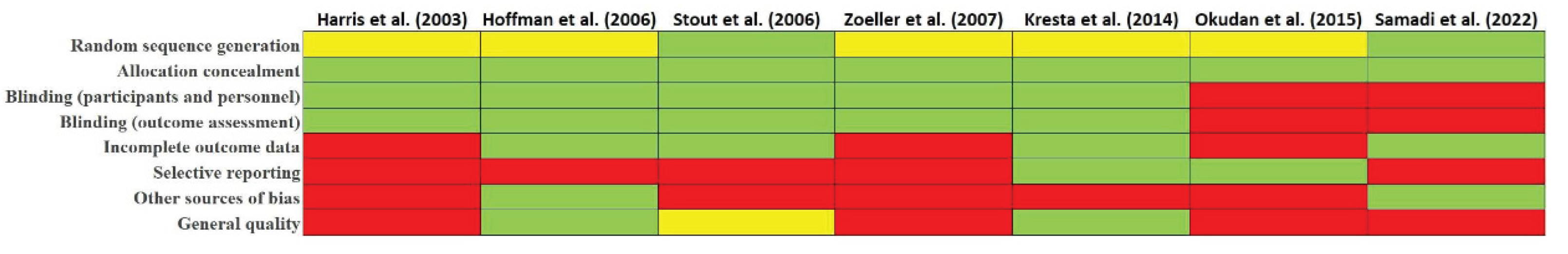

This systematic review has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the total number of included studies (n = 7) is relatively small, limiting the ability to draw definitive conclusions regarding the effects of creatine and β-alanine co-supplementation. Additionally, for some key performance and body composition outcomes, only a few studies were available, reducing the reliability and generalizability of the findings. The limited number of studies also precludes the possibility of conducting a meta-analysis, which would have provided a more robust quantitative assessment of the combined effects of these supplements.

Second, the duration of most included studies was relatively short, with intervention periods typically ranging from 4 to 5 weeks, except for one longer trial lasting 10 weeks. Given that muscle hypertrophy, body recomposition, and chronic adaptations to training require extended periods, the short intervention durations may have limited the ability to detect meaningful long-term effects of creatine and β-alanine co-supplementation. Future research should focus on longer-duration trials to determine whether the potential synergistic effects of these supplements become more pronounced over time.

Despite these limitations, this review provides valuable insights into the effects of creatine and β-alanine co-supplementation on strength, power, endurance, and body composition. However, future studies with larger sample sizes, longer intervention periods, and more standardized outcome measures are needed to further clarify the efficacy and applicability of co-supplementation in different athletic populations.