1. Introduction

Agricultural productivity is facing increasing challenges due to climate variability, soil degradation, water scarcity, and the rising global demand for food [

1]. Farmers and agricultural experts rely heavily on remote sensing technologies to monitor crop health, predict yields, and manage resources efficiently. However, the effectiveness of traditional remote sensing methods is often limited by issues such as data overload, lack of real-time adaptability, and the inability to translate raw data into actionable insights [

2]. For instance, while satellite imagery and drone-based sensing provide detailed spectral and spatial data, interpreting these data accurately requires advanced analytical techniques that many farmers and agricultural stakeholders lack access to. Additionally, the complexity of environmental factors—including unpredictable weather patterns, pest infestations, and disease outbreaks—further complicates decision-making [

3]. Delayed or inaccurate responses to these challenges result in substantial economic losses, reduced crop yields, and unsustainable farming practices. As a result, there is an urgent need for more adaptive, intelligent, and real-time decision-support systems in agricultural remote sensing.

Several traditional models have been developed to address these challenges in agricultural remote sensing. While these models provide valuable insights, they each have inherent limitations in adaptability, accuracy, and real-time decision-making. The four major approaches are used in this research. Vegetation Index Models (e.g., NDVI, EVI), the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) are widely used to assess plant health by analyzing spectral reflectance from satellite or drone images. These indices help identify stressed crops, monitor drought conditions, and estimate biomass production. However, they struggle to provide accurate results under variable atmospheric conditions, such as cloud cover or changes in soil moisture. Additionally, they often fail to consider other crucial environmental factors such as soil nutrients and pest infestations. Machine Learning-Based Classification, techniques like Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forest, and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have been used to classify crop types, detect plant diseases, and predict yields. While these models offer improved accuracy over traditional statistical methods, they require extensive labeled datasets for training. Furthermore, they are often computationally expensive and may struggle with generalization, especially when applied to diverse geographical regions with different soil and climate conditions. Geostatistical Models (e.g., Kriging, Spatial Interpolation), these models analyze spatial variability in soil properties, temperature, and crop health by interpolating data across different locations. While they are effective for localized analysis, they lack the ability to process real-time updates and adapt dynamically to changing environmental conditions. Their accuracy is also limited by data sparsity, as interpolations rely heavily on the quality and distribution of sample points. Rule-Based Decision Support Systems (DSS), many agricultural monitoring systems rely on predefined rules and thresholds to provide recommendations for irrigation, fertilization, and pest control. These systems work well in stable environments but struggle to adapt when unexpected conditions arise. Since rule-based systems do not learn from past cases, they require frequent manual updates and may not be effective in handling complex, non-linear interactions between multiple environmental variables.

While these traditional models have contributed significantly to agricultural remote sensing, they lack the adaptability and real-time learning capabilities needed to optimize decision-making under rapidly changing conditions (

Table 1).

To overcome the limitations of traditional models, integrating Case-Based Reasoning (CBR) with the Internet of Things (IoT) presents a more effective and adaptive approach to agricultural remote sensing. CBR is a problem-solving methodology that retrieves solutions from past cases to address new but similar problems. By continuously learning from previous agricultural scenarios, CBR enables intelligent decision-making based on real-world experiences rather than rigid rules or static models. The integration of IoT enhances this capability by providing real-time data from various sources, such as soil moisture sensors, weather stations, drones, and satellite imagery. These IoT-enabled devices continuously collect and transmit environmental data, allowing the CBR system to compare current conditions with past cases and recommend the most effective solutions. Unlike machine learning models that require extensive labeled datasets, CBR can make accurate predictions even with limited historical data by leveraging similarity-based retrieval techniques. For example, if a farmer encounters a disease outbreak in a specific crop, the CBR system can analyze past cases where similar conditions occurred and suggest the most effective interventions based on previous successful treatments. Similarly, for irrigation management, the system can adjust water distribution based on real-time soil moisture readings and past cases of optimal water usage. This dynamic and context-aware approach ensures that recommendations are always aligned with actual field conditions, making it superior to traditional rule-based or static decision models. The advantages of combining CBR with IoT are shown below;

Real-time adaptability – The system continuously updates its knowledge base with new cases, improving its accuracy over time.

Reduced data dependency – Unlike machine learning models that require large training datasets, CBR can function effectively with limited historical data.

Personalized recommendations – Farmers receive tailored advice based on past cases that closely match their specific conditions.

Scalability and automation – IoT integration enables automated data collection and analysis, reducing the need for manual monitoring.

By integrating CBR with IoT, agricultural remote sensing systems become more intelligent, context-aware, and responsive, ultimately leading to improved crop management, higher yields, and more sustainable farming practices.

Research Questions

To guide the development and evaluation of this approach, the following research questions are proposed;

How can Case-Based Reasoning (CBR) enhance decision-making in agricultural remote sensing?

What are the key advantages of integrating IoT with CBR for real-time monitoring and adaptive learning?

How does the hybrid CBR and IoT approach compare to traditional models in terms of accuracy, efficiency, and scalability?

What are the practical implementation challenges of deploying CBR and IoT in real-world agricultural settings?

The primary objective of this research is to develop a novel agricultural remote sensing framework that integrates Case-Based Reasoning (CBR) with the Internet of Things (IoT). This framework aims to enhance real-time decision-making, improve agricultural resource management, and provide adaptive solutions to challenges such as crop disease detection, yield prediction, and irrigation management.

Designing a CBR system capable of retrieving and adapting past agricultural cases to new situations.

Integrating real-time IoT sensor data to enhance the accuracy and relevance of CBR-driven recommendations.

Comparing the performance of the CBR + IoT approach with traditional models across multiple agricultural scenarios.

Evaluating the practical feasibility and scalability of implementing this framework in different farming environments.

This research contributes to the advancement of smart agriculture and agricultural remote sensing in several key ways;

Innovative Framework Development – Introducing a novel CBR + IoT framework that dynamically adapts to changing agricultural conditions, surpassing the limitations of traditional static models.

Improved Decision-Making – Enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of crop monitoring, disease detection, and resource allocation through an intelligent, case-based decision-support system.

Real-World Applicability – Providing a practical, scalable solution that can be implemented across diverse agricultural landscapes, benefiting farmers and agricultural stakeholders.

Data-Driven Adaptability – Leveraging IoT-generated real-time data to refine case retrieval and adaptation processes, ensuring continuous learning and optimization.

Sustainable Agriculture – Supporting more efficient water use, precise fertilization, and early disease intervention, leading to improved sustainability and reduced environmental impact.

By bridging the gap between data-driven insights and actionable agricultural strategies, this research aims to revolutionize agricultural remote sensing through adaptive intelligence and real-time decision-making.

2. Related Work

2.1. Remote Sensing Technologies in Agriculture

Remote sensing technologies in agriculture have revolutionized the way farmers monitor and manage their crops [

8]. These technologies enable the collection of detailed spatial and temporal data on crop health, soil conditions, and environmental factors through the use of satellites, drones, and other aerial platforms. Remote sensing provides valuable insights into a variety of agricultural variables, such as vegetation indices, soil moisture, temperature, and nutrient levels. This information is critical for precision agriculture, which aims to optimize resource use, increase crop yields, and reduce environmental impact. As a result, farmers are able to make informed decisions about irrigation, fertilization, pest control, and disease management, leading to more sustainable farming practices [

9].

One of the most widely used remote sensing techniques in agriculture is the use of vegetation indices (VIs), such as the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI). NDVI allows for the assessment of plant health by analyzing the reflectance of light in specific wavelengths, such as infrared and red bands. By measuring the difference between these wavelengths, NDVI can indicate the level of chlorophyll in plants, which is directly related to their health and productivity. Remote sensing platforms like satellites and drones equipped with multispectral cameras capture the necessary data for calculating NDVI and other vegetation indices, enabling farmers to detect early signs of stress, disease, or nutrient deficiencies before they become visible to the naked eye [

10].

In addition to vegetation indices, remote sensing technologies can also provide real-time data on soil properties and weather conditions. Soil moisture, temperature, and salinity can be monitored using ground-based sensors and remote sensing devices, providing valuable information for irrigation management. For example, thermal infrared imaging can identify temperature variations in soil, which is essential for assessing the heat stress on crops. This data, when combined with weather forecasts and climate models, enables farmers to optimize irrigation schedules, reduce water waste, and improve crop yields. Moreover, remote sensing technologies can track changes in environmental conditions such as rainfall, temperature fluctuations, and pest migration patterns, helping farmers make more informed decisions about pest and disease management [

11].

Remote sensing in agriculture faces several challenges, including data overload, interpretation complexity, and high costs [

12]. While remote sensing platforms can provide vast amounts of data, processing and analyzing this data require advanced computational resources and expertise, which many farmers may lack. Moreover, real-time adaptability remains a challenge, as weather patterns, pest outbreaks, and other environmental factors can change rapidly, requiring continuous updates to the data and decision-making processes. To overcome these challenges, researchers are increasingly integrating remote sensing technologies with artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, and Case-Based Reasoning (CBR) systems. These approaches allow for the automated analysis of large datasets, translating raw data into actionable insights that can be used to guide farming practices in a more efficient and timely manner.

2.2. Case-Based Reasoning in Agricultural Decision-Making

Case-Based Reasoning (CBR) is an AI technique that relies on the retrieval of past experiences or cases to solve new problems [

13]. In agricultural decision-making, CBR is an effective approach for leveraging historical knowledge to address challenges such as pest control, irrigation scheduling, crop management, and disease outbreaks. The fundamental concept behind CBR is that similar problems in the past can offer insights and solutions for new, but similar, challenges. By storing past cases with associated outcomes and contextual information, farmers and agricultural experts can retrieve these cases and adapt them to current circumstances, leading to more informed and efficient decision-making. In agriculture, where conditions are dynamic and diverse, CBR enables decision support systems to work effectively in real-world environments [

14].

In precision agriculture, CBR plays a crucial role in enabling data-driven, context-specific decisions that optimize resource use and improve productivity. CBR systems in this domain can use remote sensing data, soil moisture levels, weather patterns, and crop health data to assess a situation and find the most relevant past cases for comparison [

15]. For example, CBR can help determine the best irrigation practices for a particular field by drawing on previous cases where similar soil moisture conditions were observed. This not only saves time but also reduces costs by preventing over- or under-application of water, fertilizers, or pesticides. By learning from past experiences, CBR helps farmers improve efficiency and sustainability in their operations, making precision agriculture more accessible and practical [

16].

CBR systems can be enhanced with real-time data, enabling more dynamic and adaptive decision-making. By integrating data from IoT devices, sensors, drones, and satellite imagery, CBR systems can update their case base with new observations and experiences [

17]. This ensures that decision support systems provide up-to-date and highly relevant recommendations based on current agricultural conditions. For example, in the event of a sudden pest infestation or an unexpected weather event, CBR systems can quickly retrieve cases with similar circumstances and offer solutions that have proven effective in the past. This real-time adaptability significantly enhances decision-making, as it allows farmers to respond promptly to emerging challenges, improving their ability to prevent crop damage and maximize yields [

18]. While CBR offers promising solutions for agricultural decision-making, there are challenges in its widespread adoption. One of the key issues is the availability and quality of historical data. Effective CBR requires a comprehensive and high-quality case base that represents a variety of agricultural scenarios. However, collecting and maintaining such a database can be resource-intensive and time-consuming [

19]. Additionally, CBR systems rely on expert knowledge to generate meaningful cases, which may not always be available or easily transferable to different agricultural contexts. To overcome these challenges, there is a growing need for collaboration between farmers, researchers, and technology developers to improve data sharing, standardization, and the integration of diverse data sources. Moving forward, the combination of CBR with advanced machine learning and big data analytics has the potential to create more robust and intelligent systems capable of handling increasingly complex agricultural decision-making processes [

20].

3.3. Integration of Remote Sensing and Case-Based Reasoning for Precision Agriculture

The integration of remote sensing and Case-Based Reasoning (CBR) for precision agriculture represents a significant advancement in agricultural decision-making [

21]. Remote sensing technologies, such as satellites, drones, and sensors, provide valuable data on crop health, soil conditions, and environmental factors, while CBR enables the application of past experiences to guide future decisions. By combining these two technologies, farmers can leverage historical case data to interpret current remote sensing observations and make more accurate, context-specific decisions. For instance, CBR can help analyze spectral reflectance data from satellites to determine whether a particular crop is showing early signs of disease, and then retrieve similar past cases of disease management to recommend the best course of action [

22]. One of the main benefits of integrating CBR with remote sensing in agriculture is the ability to handle complex, dynamic datasets. Remote sensing platforms generate vast amounts of data that can be difficult to process and interpret manually [

23]. CBR allows farmers to build a knowledge base of previous cases and use it to identify patterns in the data. For example, if a farmer receives a remote sensing alert indicating a decrease in vegetation health, the CBR system can compare this observation with past cases of similar environmental conditions and crop performance. By referencing past experiences, the system can offer tailored recommendations for irrigation, fertilization, or pest control based on what worked well in similar situations, reducing the risk of incorrect decisions [

24].

Moreover, the combination of remote sensing and CBR enables real-time adaptability in precision agriculture. Remote sensing systems can continuously monitor the status of crops and environmental conditions, while CBR can quickly adapt to new data by referencing the most relevant historical cases [

25]. This adaptability is crucial in agriculture, where conditions can change rapidly due to factors like weather events, pest outbreaks, or disease spread. For example, in the case of a sudden drought or pest infestation, CBR can pull up past cases where similar events occurred and recommend rapid responses, such as adjusting irrigation schedules or deploying pest control measures. This real-time feedback loop enhances the efficiency and timeliness of decisions, improving overall crop management and resource utilization [

26]. Finally, integrating remote sensing and CBR can improve decision-making accuracy and sustainability in precision agriculture. By automating the analysis of remote sensing data and utilizing past case knowledge, farmers are empowered to make data-driven decisions that optimize resource use while minimizing waste and environmental impact. For instance, by analyzing historical cases of nutrient deficiencies and comparing them to real-time satellite imagery, CBR can recommend precise fertilizer application schedules, reducing the risk of over-fertilization and runoff. This integration not only helps improve crop yields but also promotes sustainable farming practices by encouraging more efficient use of water, fertilizers, and pesticides.

3.4. Challenges and Opportunities in Agricultural Remote Sensing with Case-Based Reasoning

One of the primary challenges in integrating Case-Based Reasoning (CBR) with agricultural remote sensing lies in the complexity and variability of agricultural environments [

27]. Remote sensing data, which is often derived from satellite imagery or drones, is subject to numerous environmental factors such as cloud cover, atmospheric interference, and varying soil and crop conditions. This can make the data noisy and inconsistent, complicating the retrieval and application of relevant cases. Additionally, CBR systems require a comprehensive and diverse case database to function effectively [

28]. Building such a database for agriculture is challenging because of the heterogeneity of agricultural practices, climate zones, and crop types, making it difficult to accumulate a sufficient number of cases that accurately represent all possible agricultural scenarios.

Another significant challenge is the integration and standardization of data from various remote sensing platforms. Agricultural remote sensing data comes from multiple sources, including satellites, drones, and ground-based sensors, each with different formats, resolution, and temporal frequency. CBR systems require consistent and structured data for accurate case retrieval and decision-making. Harmonizing data from these different sources into a unified format that can be used effectively by CBR models is a complex task. Furthermore, remote sensing data is often spatially and temporally sparse, which can limit the effectiveness of CBR when making predictions or recommendations based on real-time data [

29].

There are significant opportunities for using CBR in precision agriculture. One of the major advantages is that CBR can help farmers make context-specific, data-driven decisions based on historical cases. For example, when confronted with a new pest infestation, CBR can retrieve past cases from similar conditions and provide recommendations for control measures based on what has worked in similar situations. This allows for more targeted interventions, reducing the need for broad-spectrum pesticides and minimizing environmental impact. Furthermore, by continuously updating the case base with new experiences and observations, CBR systems can improve over time, becoming more precise and tailored to local agricultural conditions [

30].

The future potential of integrating agricultural remote sensing with CBR is promising, particularly with advancements in machine learning and big data analytics. Machine learning algorithms can be used to improve case retrieval by automating the process of case base expansion and ensuring that only the most relevant cases are considered. As more agricultural data becomes available through IoT devices, cloud computing, and more frequent satellite imagery, CBR systems can evolve into more adaptive decision support tools. These systems could not only recommend solutions for current agricultural problems but also predict future issues based on historical trends and emerging environmental patterns. Such developments hold the potential to greatly enhance agricultural productivity and sustainability, providing farmers with real-time, actionable insights that are highly tailored to their specific needs [

31].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Related Traditional Models

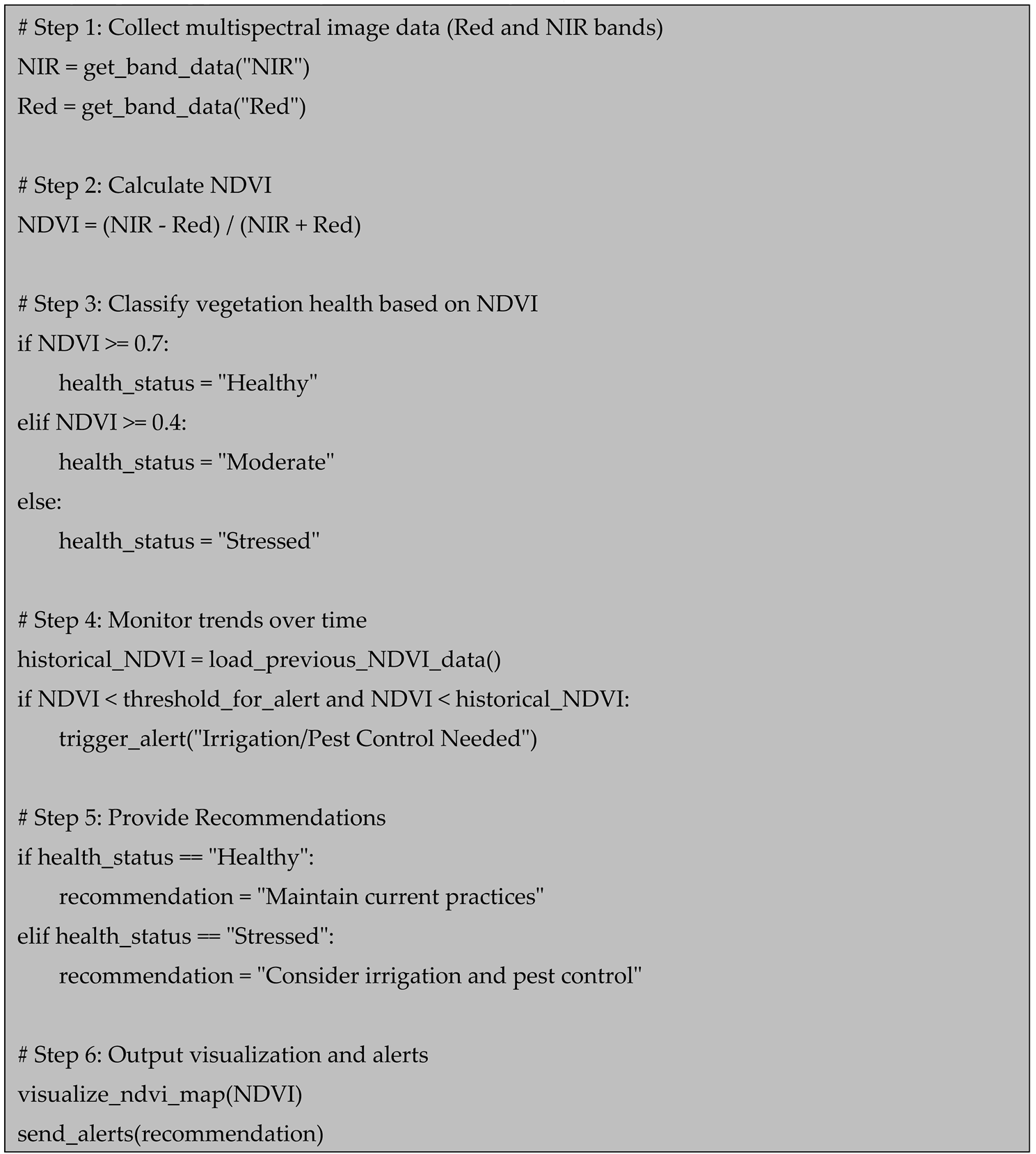

Vegetation Index Models (VIM) solve the challenges in agricultural productivity by providing a method to analyze spectral reflectance from satellite or drone images to assess plant health. These models, such as the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), can monitor plant vigor, stress levels, and overall health in real-time. By tracking changes in vegetation indices over time, VIM helps farmers and agricultural experts identify early signs of issues like water stress, nutrient deficiencies, or disease outbreaks, enabling more proactive and informed decision-making. While satellite imagery and drone-based sensing offer detailed data, VIM allows for the transformation of raw spectral information into actionable insights that are easier to interpret and apply. This reduces the need for complex data analysis, which can be a barrier for farmers lacking access to advanced computational resources. The real-time adaptability of VIM enhances its utility, as farmers can track changes in crop health and make timely adjustments to practices like irrigation or pest control, thereby improving productivity and sustainability [

32].

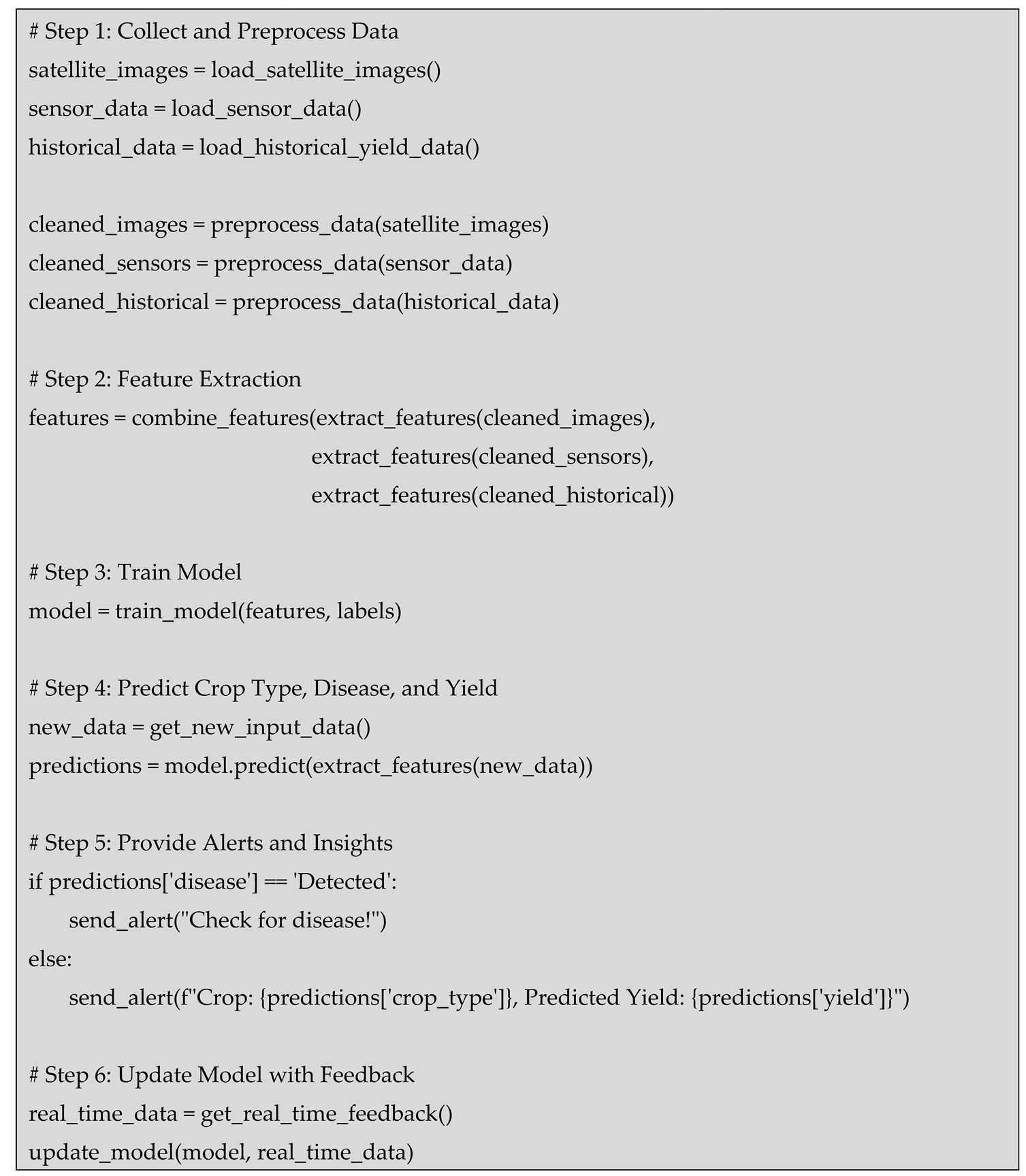

Machine Learning-Based Classification (MLBC) addresses the need for intelligent, adaptive decision-making in agriculture by using AI algorithms to classify crop types, detect plant diseases, and predict yields. Machine learning algorithms can analyze large datasets, such as satellite images, sensor data, and historical yield records, to recognize patterns that human experts might miss. For instance, MLBC can detect early signs of disease or pest infestation by classifying pixel-level variations in imagery, which helps farmers take immediate actions to minimize damage. Additionally, these models can predict future crop yields based on environmental factors, such as weather patterns and soil conditions, enabling farmers to make better planning decisions. By automating these processes, MLBC reduces the reliance on manual interpretation and provides real-time, actionable insights that enhance decision-making. This not only improves agricultural productivity but also helps mitigate the risks posed by climate variability, water scarcity, and other environmental challenges. In combination with remote sensing, MLBC provides farmers with the tools to interpret complex data more effectively, adapt to changing conditions, and optimize resource use, ultimately contributing to more sustainable and resilient farming practices [

33].

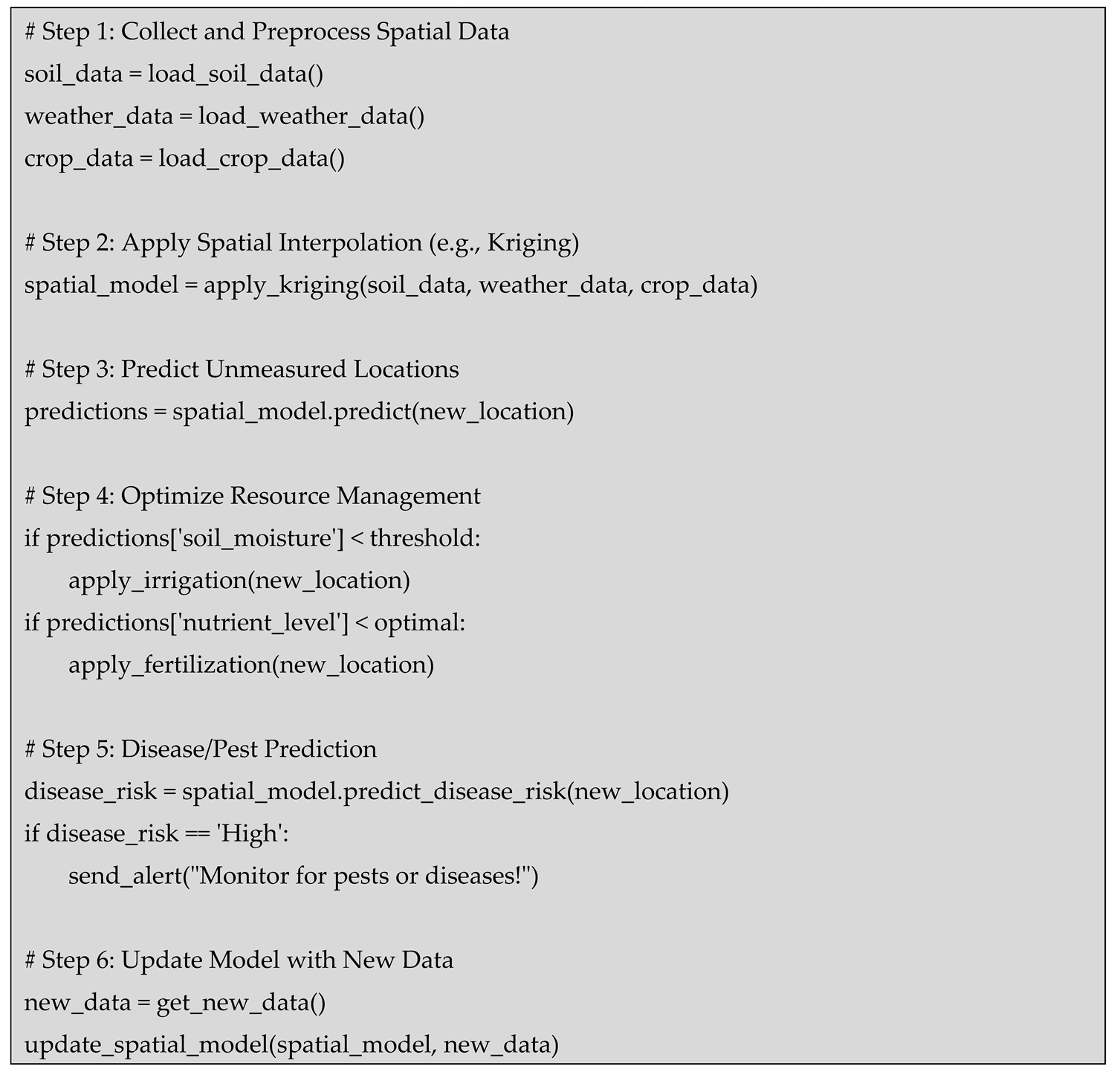

Geostatistical Models (GM) provide a powerful approach to address agricultural challenges by utilizing spatial statistics to model and analyze spatial variability in environmental and agricultural data. These models take into account the inherent spatial relationships in soil properties, weather conditions, and crop performance, offering insights into the distribution and patterns of variables like soil moisture, temperature, and nutrient levels. GM uses techniques such as kriging to interpolate spatial data, enabling accurate predictions about unmeasured locations based on nearby data points. This ability to understand and predict spatial variability is crucial for optimizing resource management, such as precise irrigation or fertilization, in areas with uneven soil quality or variable climate conditions. Additionally, GM can help farmers and agricultural experts predict the spread of diseases or pests, allowing for more targeted and effective interventions. By incorporating spatial data into the decision-making process, GM provides more accurate and localized recommendations, enhancing the efficiency of agricultural operations and improving overall productivity [

34].

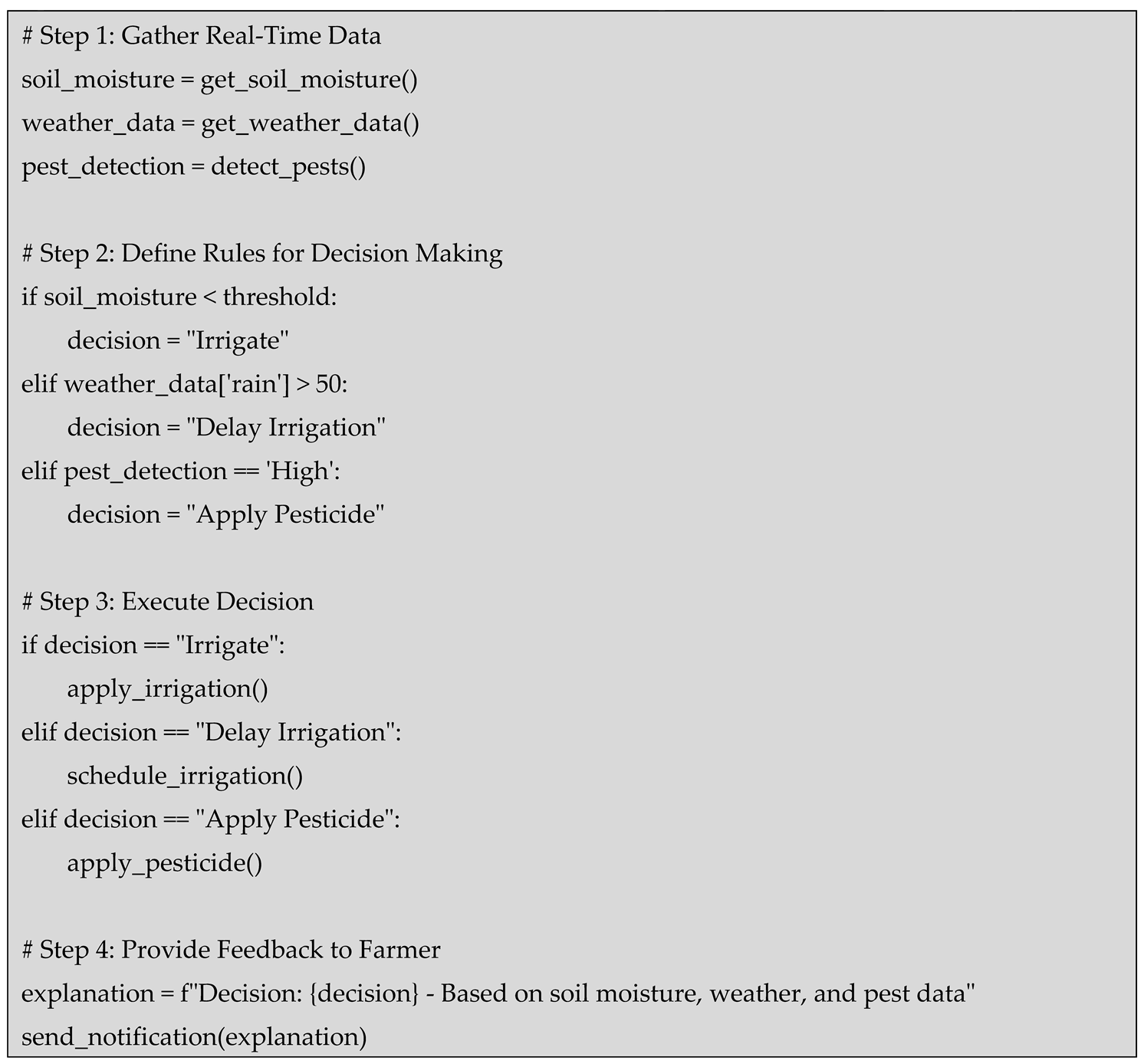

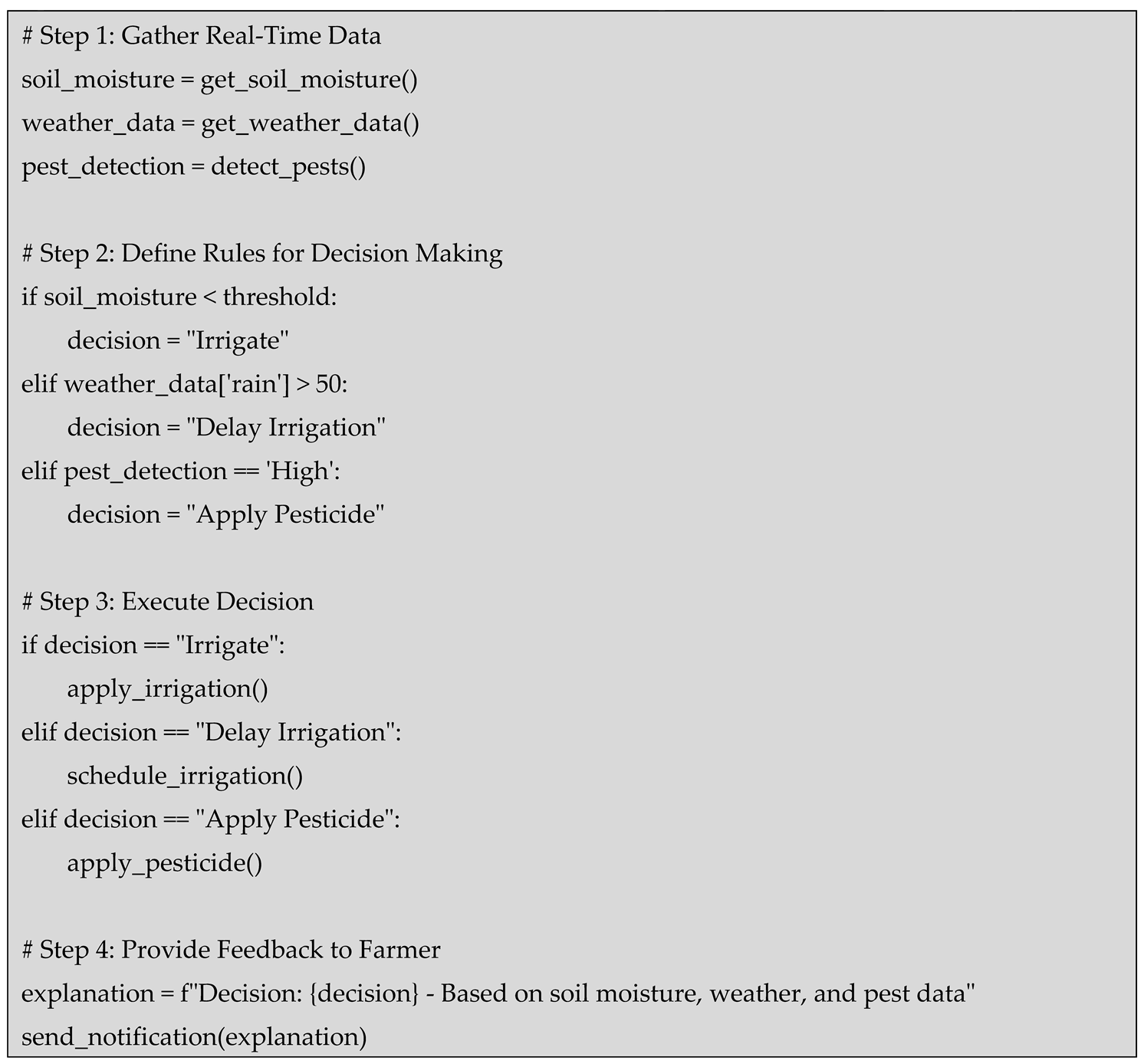

Rule-Based Decision Support Systems (RBDSS) provide a framework for translating complex agricultural data into actionable recommendations through a set of predefined rules that guide decision-making. These systems are based on expert knowledge and domain-specific rules that can consider a wide range of factors such as crop type, soil health, weather patterns, and pest or disease presence. RBDSS can automate decisions about irrigation scheduling, fertilization, pesticide application, and crop management by using logical conditions (e.g., if soil moisture is below a certain threshold, then irrigate). This simplifies decision-making for farmers by providing clear and actionable guidance, especially in situations where real-time data is available from IoT devices or remote sensing technologies. The major advantage of RBDSS is its ability to offer explainable decisions, where the reasoning behind the recommendations is clear, ensuring that farmers can trust and understand the system’s outputs. By incorporating a dynamic set of rules that can be adjusted based on ongoing data inputs, RBDSS can adapt to changing agricultural conditions, leading to improved resource utilization, reduced environmental impact, and enhanced productivity [

35].

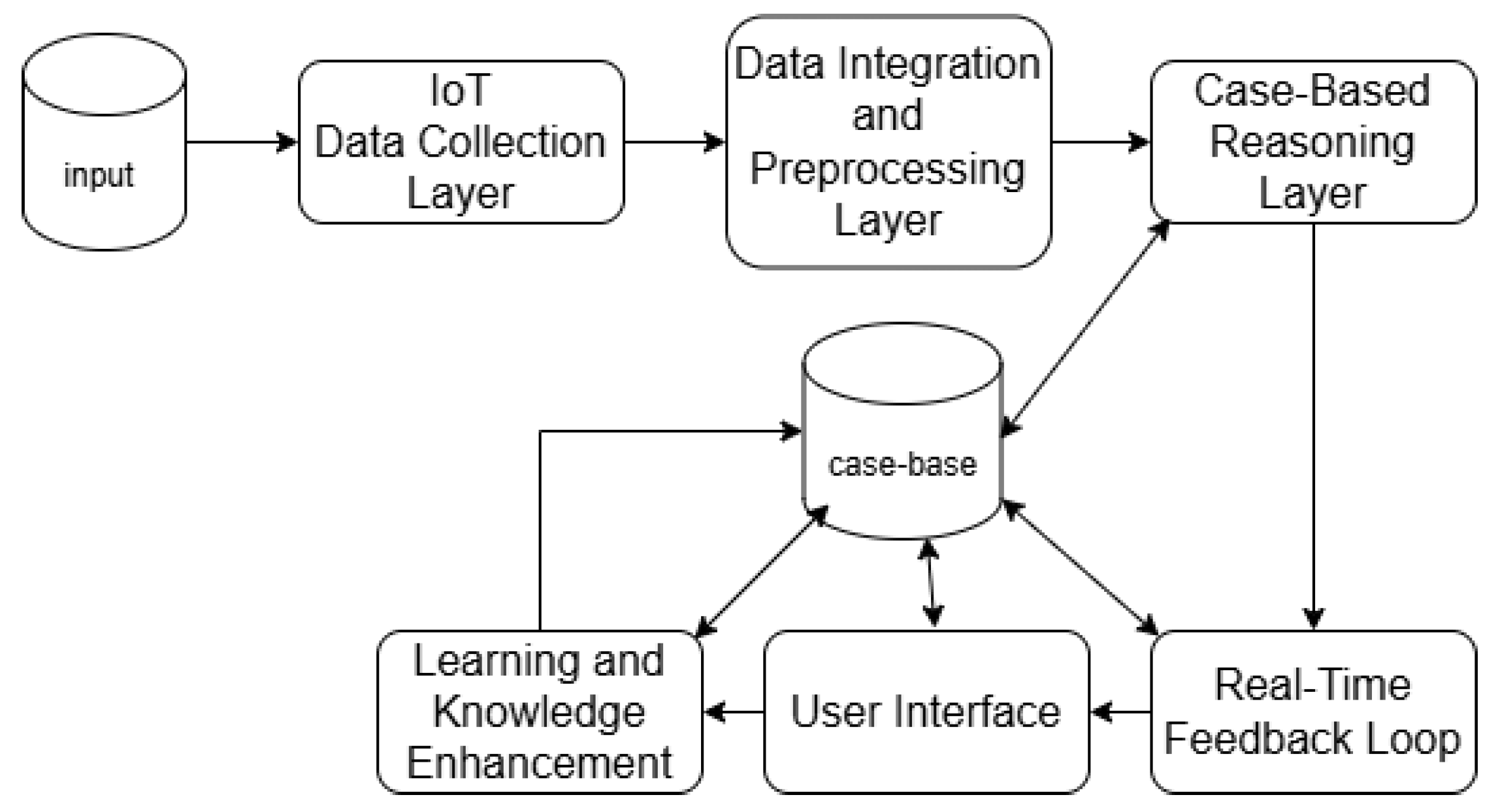

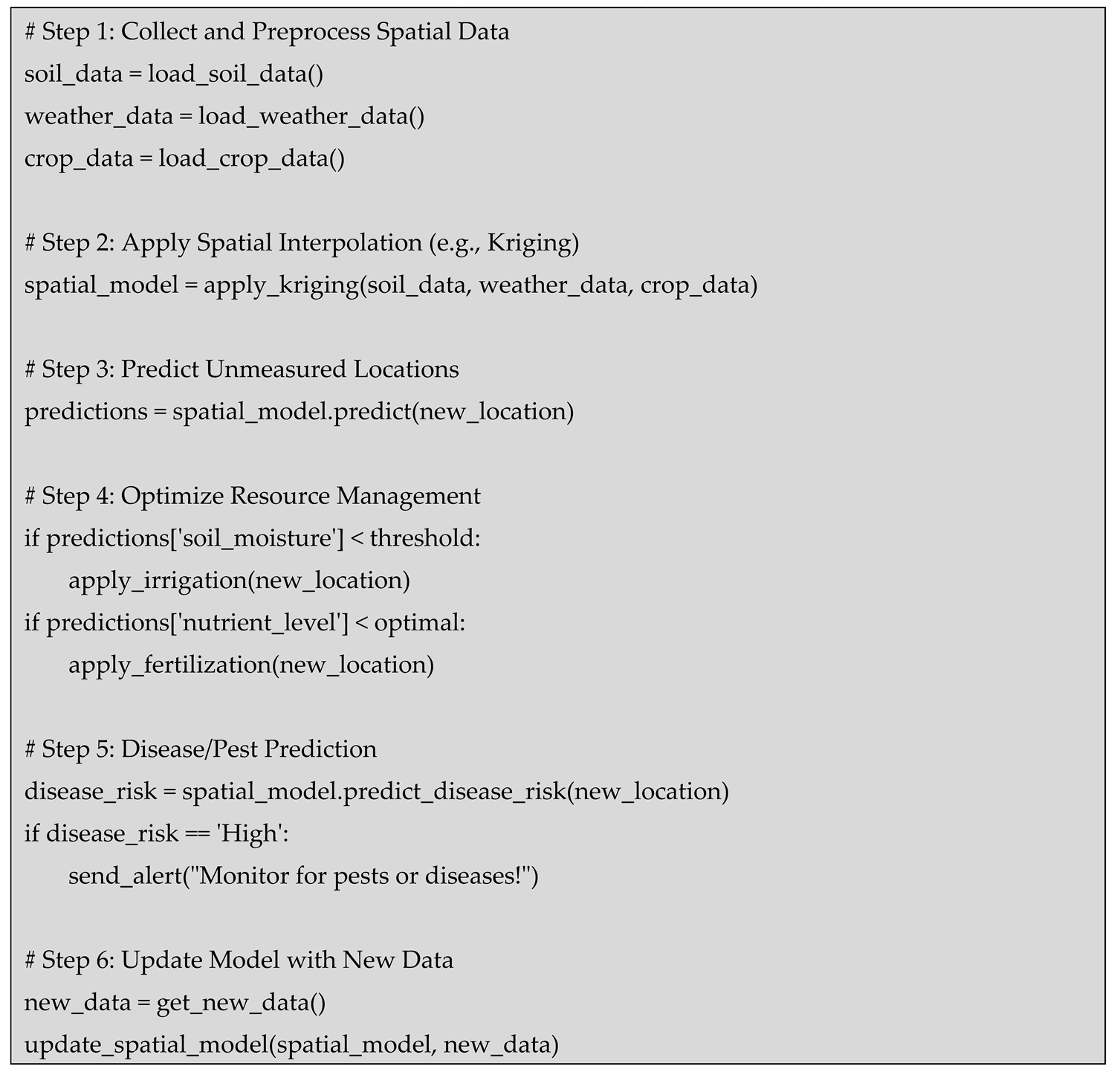

3.2. Conceptual Model: CBRIoT

The conceptual model provides an advanced and adaptive solution for agricultural remote sensing. IoT devices such as soil moisture sensors, weather stations, drones, and satellites collect real-time environmental data, which is processed and stored in a knowledge base. This data is then compared with historical agricultural cases through CBR to identify similarities, allowing the system to recommend the most effective solutions based on past experiences. Unlike traditional models, CBR doesn’t require extensive labeled datasets. It can make accurate predictions with limited data by leveraging similarity-based retrieval techniques. For example, if a farmer faces a disease outbreak, the system recommends treatments based on past successful interventions for similar conditions. Additionally, the system dynamically adjusts recommendations, such as irrigation strategies, based on real-time data like soil moisture levels. This integration ensures real-time adaptability and continuous learning, as the system updates its knowledge base with each new data input. It provides personalized, actionable insights, helping farmers make informed decisions for crop management. Over time, the system improves its accuracy, ensuring optimal, sustainable farming practices.

Phase I IoT Data Collection Layer

i) Sensors and Devices: IoT-enabled devices (soil moisture sensors, weather stations, drones, satellites) continuously collect environmental data in real-time.

ii) Types of Data Collected: Temperature, humidity, soil moisture, crop health, weather forecasts, etc.

iii)Data Transmission: The collected data is transmitted in real-time to the central system for analysis.

Phase II Data Integration and Preprocessing Layer

i) Data Fusion: Data from various IoT devices (sensors, drones, satellites) are integrated into a unified system.

ii) Preprocessing: The raw data is cleaned, normalized, and processed to extract meaningful features relevant to agricultural conditions.

iii) Storage: Processed data is stored in a knowledge base or case library for future retrieval (historical data, case studies, etc.).

Phase III Case-Based Reasoning Layer

i) Case Library: A repository of past agricultural cases, where each case contains the scenario, environmental conditions, and outcomes (e.g., disease outbreaks, irrigation strategies, pest control).

ii) Similarity Matching: When new data is received, CBR retrieves past cases that share similarities with current conditions. It uses similarity-based retrieval techniques to compare new data (real-time IoT input) with historical cases.

iii) Reasoning & Adaptation: CBR analyzes retrieved cases and adapts previous solutions to the current situation. The reasoning process considers environmental factors, crop type, geographic location, and past interventions that worked successfully.

iv) Decision Support: CBR provides personalized recommendations based on the most similar past cases, such as irrigation adjustments, pest control actions, or disease management.

Phase IV Real-Time Feedback Loop

i) Real-Time Data Adjustment: As IoT devices continue to monitor conditions (e.g., soil moisture, temperature), the system constantly updates its knowledge base with new data and revises its recommendations.

ii) Dynamic Adaptation: Recommendations are adjusted dynamically based on real-time conditions, allowing for immediate intervention if changes are detected (e.g., sudden weather shift, pest infestation).

Phase V User Interface (Farmer Dashboard)

i) Personalized Recommendations: Farmers receive customized advice through a user-friendly interface (e.g., mobile app, dashboard), which provides timely, actionable insights based on the latest case analysis.

ii) Visualization of Conditions: Visual representation of real-time data (soil moisture, crop health, etc.) alongside past case information helps farmers understand the context of the recommendations.

iii) Actionable Alerts: The system sends alerts when conditions deviate from the expected norms, prompting necessary actions (e.g., irrigation, pesticide application, fertilization).

Phase VI Learning and Knowledge Enhancement

i) Continuous Case Updating: As new interventions are applied and new data is collected, the system continuously learns and adds new cases to the knowledge base, improving future decision-making capabilities.

ii) Self-Improvement: Over time, the system enhances its performance by learning from real-world successes and failures, ensuring more accurate predictions and better outcomes for future agricultural challenges.

Figure 1.

The Proposed Model.

Figure 1.

The Proposed Model.

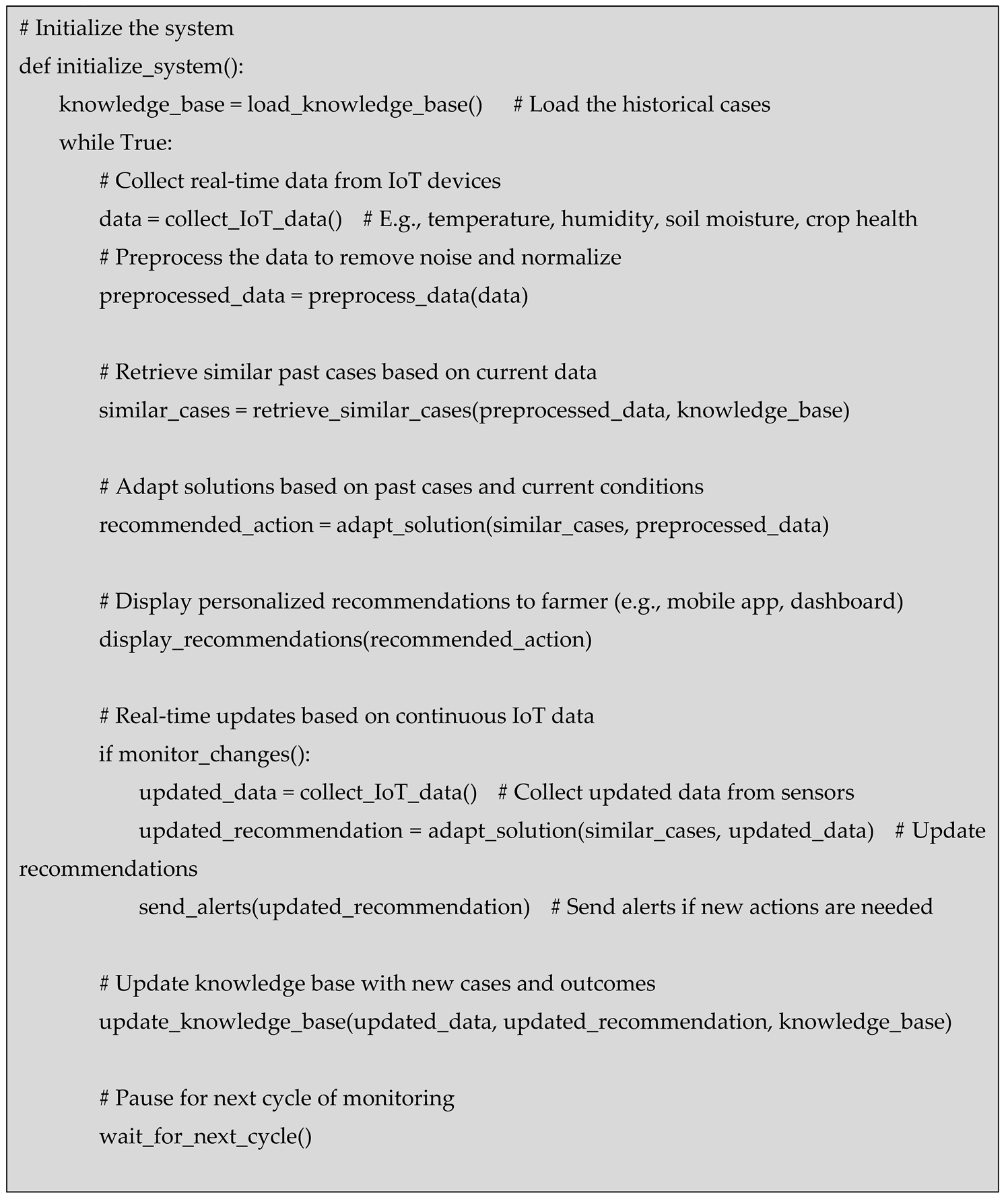

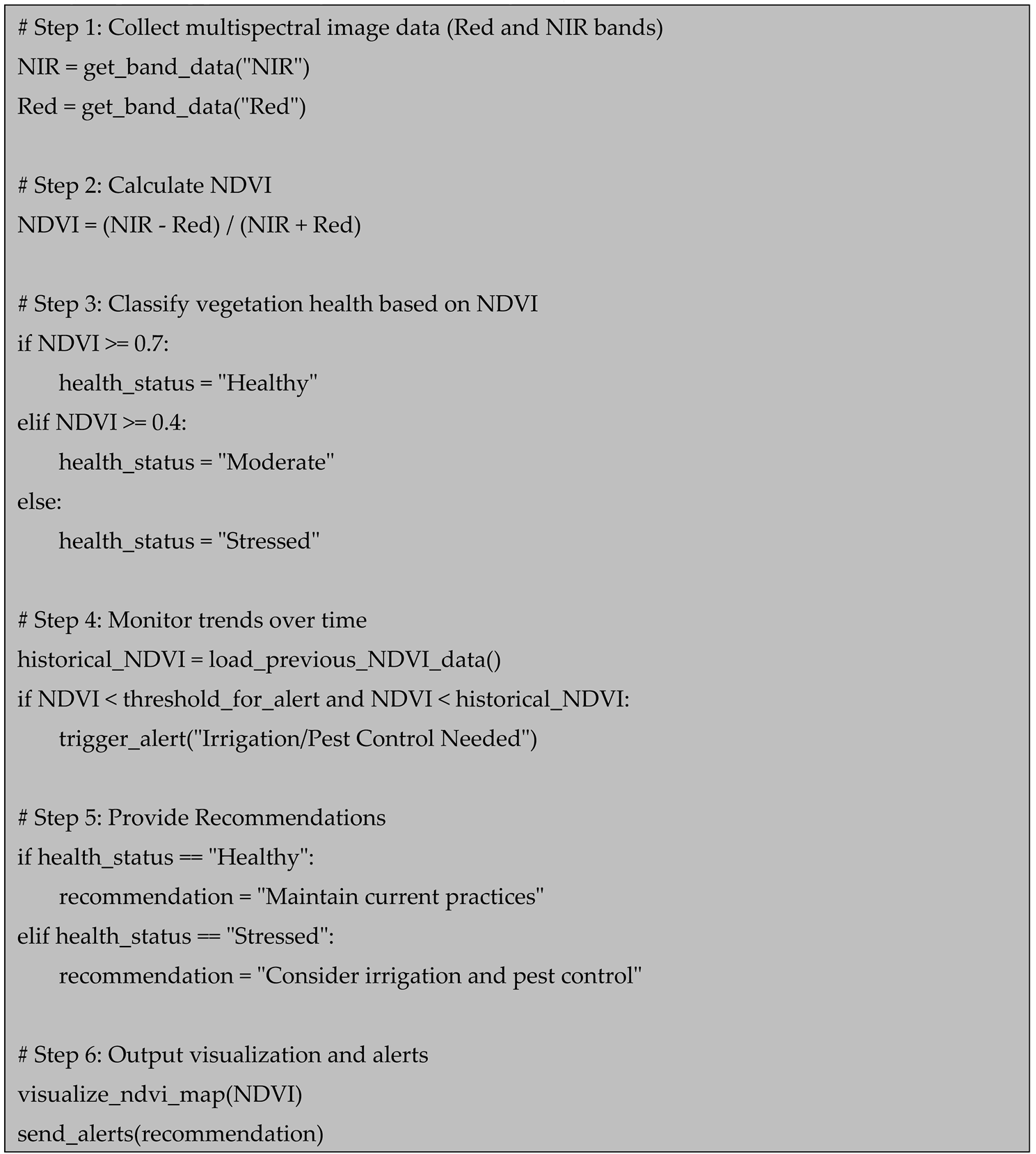

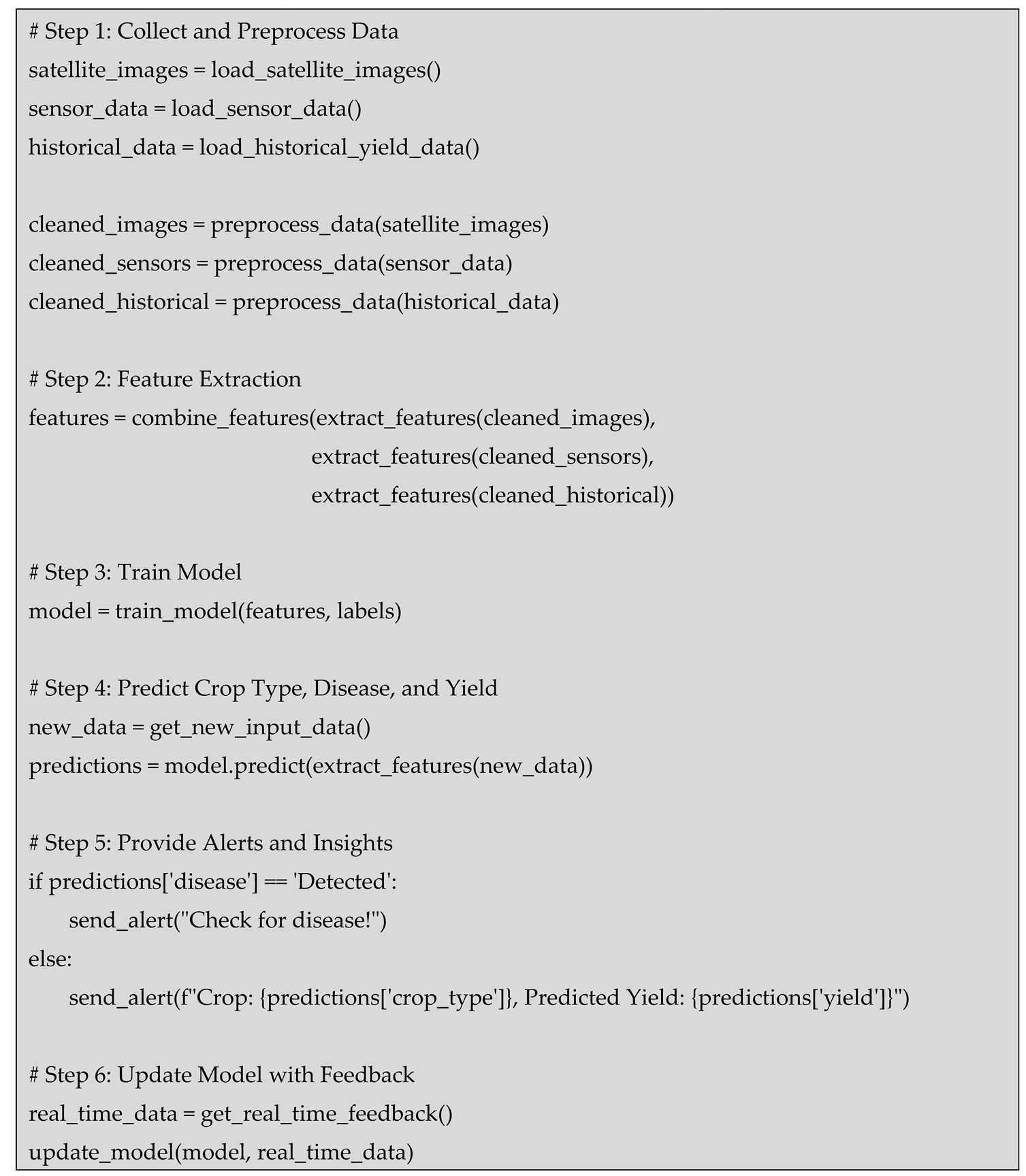

Algorithm

3.3. Data Source

Papers with Code provides a vast collection of datasets across various domains, including agriculture, remote sensing, and AI-driven analytics. For agricultural applications, datasets like Agriculture-Vision and Extended Agriculture-Vision offer large-scale aerial imagery for crop classification and segmentation. Other datasets focus on IoT-based Smart Agriculture and Crop Monitoring, open agricultural data reviews, and specific datasets like Single Point Corn Yield Data for yield prediction. These datasets enable Case-Based Reasoning (CBR), geostatistical modeling, and machine learning applications in precision farming, soil analysis, and crop health monitoring, supporting AI-driven decision-making and predictive analytics for sustainable agriculture. Visit

https://paperswithcode.com/ for access [

36].

Table 2.

Dataset.

| Dataset |

Description |

Relevance to Agricultural Remote Sensing & AI Models |

| Agriculture-Vision (AV) |

Large-scale aerial farmland image dataset for semantic segmentation of agricultural patterns. |

Supports CBR for case-based segmentation, NDVI/EVI for vegetation health analysis, and ML-based classification for crop type identification. |

| Extended Agriculture-Vision (EAV) |

Improved dataset with full-field farmland imagery and 3TB of high-resolution images across the US. |

Enables CBR-driven learning from past cases, geostatistical modeling for spatial variability, and ML-based classification for predictive analytics. |

| Smart Agriculture and Crop Monitoring (SA) |

Case study on using drones, IoT sensors, and AI analytics for agriculture. |

Enhances real-time DSS, CBR for adaptive decision-making, and geostatistical models for soil moisture interpolation. |

| A Systematic Review of Open Data in Agriculture (SR) |

PRISMA systematic review of Open Data and Public Domain data in agriculture. |

Provides historical datasets for CBR case retrieval, validates geostatistical models, and aids in improving ML-based classification accuracy. |

| Single Point Corn Yield Data (SP) |

Weather, soil, and cultivation data for corn yield prediction in Sub-Sahara Africa. |

Supports CBR-based yield forecasting, ML-based classification of soil and crop types, and geostatistical interpolation for predicting environmental impacts. |

| ACFR Orchard Fruit Dataset (ACFR) |

Agricultural dataset with images and annotations of different fruits collected across Australian farms. |

Enables CBR-driven disease detection, ML-based classification for fruit sorting, and NDVI/EVI-based vegetation health monitoring. |

3.4. Evaluations

Decision-Making Efficiency () [37]

Measures the proportion of correct decisions made by the model across n test cases, where represents the number of correct decisions and represents all decisions made.

Processing Time Per Decision () [38]

Computes the average time required to process a single decision, where is the processing time for each decision instance.

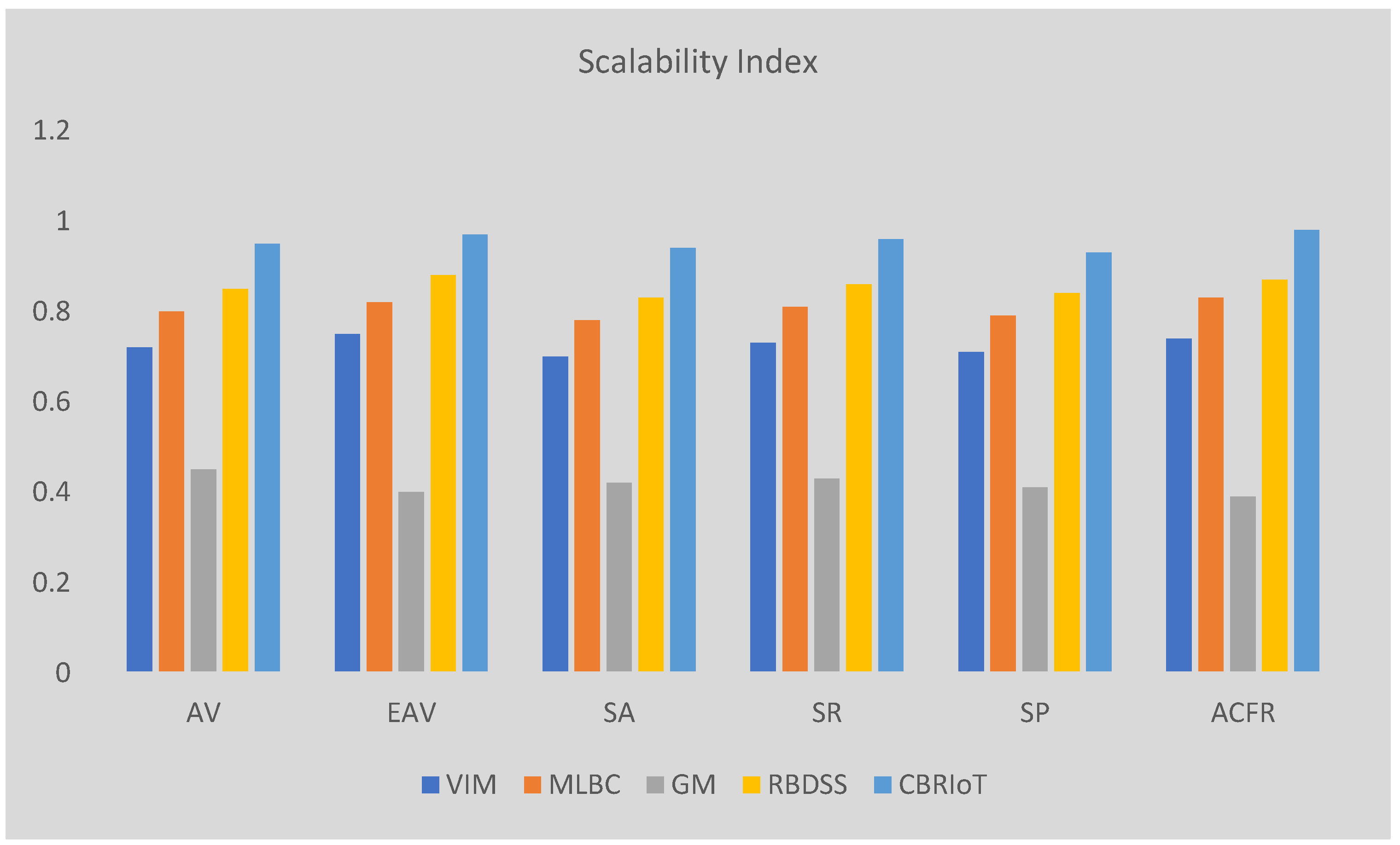

Scalability Index (

) [

39]

Evaluates how efficiently the system scales, where is the computational cost, is the number of IoT devices, and D is the data volume processed.

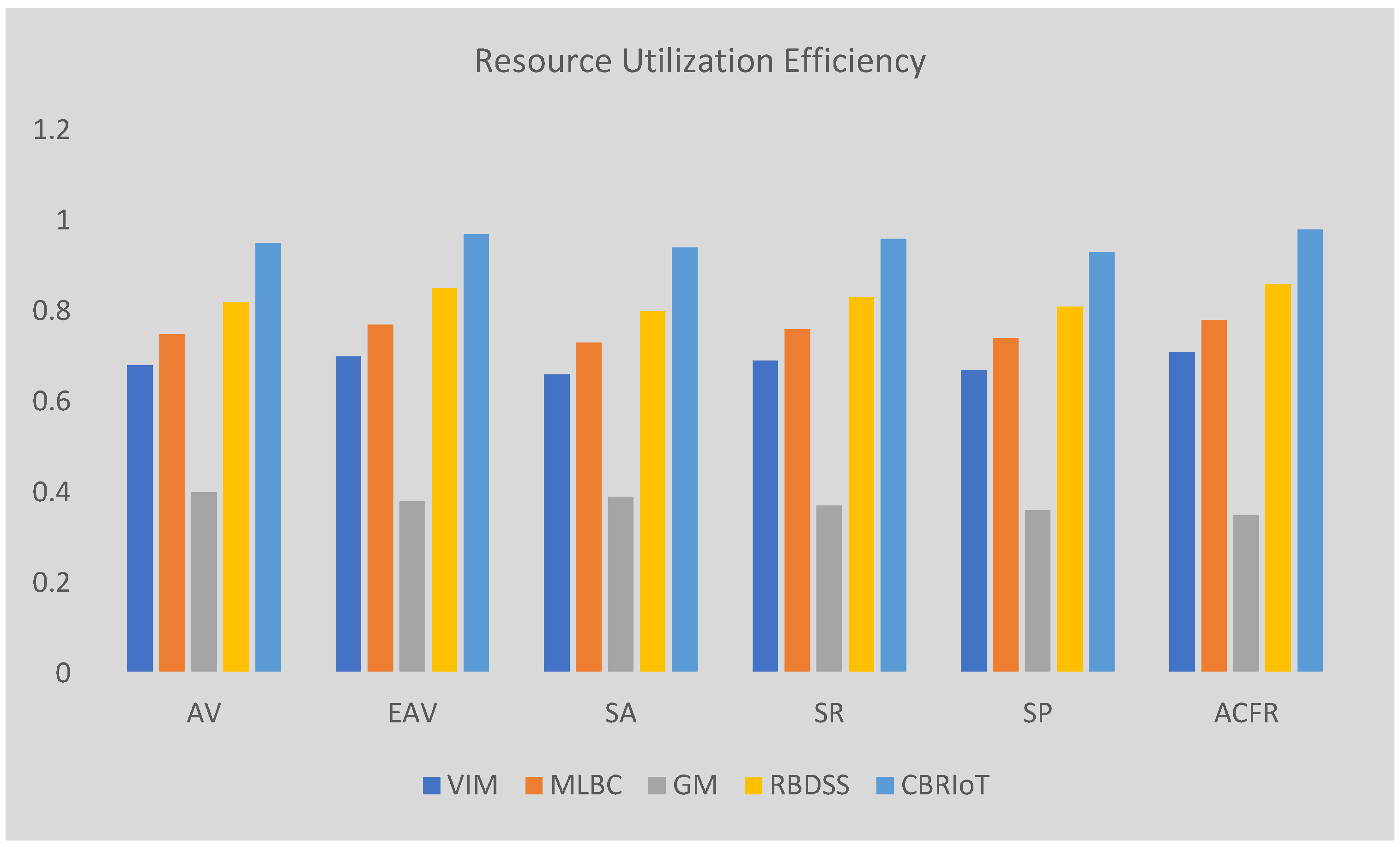

Resource Utilization Efficiency () [

40]

Measures the efficiency of resource use, where Y represents agricultural yield or productivity improvement, and I represents input resources such as water, fertilizers, and computational power.

These equations ensure a standardized evaluation for all models, allowing fair comparisons in terms of decision-making accuracy, computational efficiency, scalability, and resource utilization.

The use of standardized evaluation metrics, as represented by those four, is crucial for ensuring fair and reliable comparisons between different models in agricultural decision-making systems. These metrics enable the comprehensive assessment of each model's performance based on key aspects that impact real-world implementation, such as decision accuracy, processing speed, system scalability, and resource efficiency. is essential for evaluating how well each model can make correct decisions across various test cases. This measure allows for the comparison of model accuracy, ensuring that models that provide more accurate decisions are recognized. The equation ensures that decision-making quality is not judged by subjective measures but rather by quantifiable outcomes—correct vs. total decisions. addresses the time efficiency of each model, which is particularly important in real-time decision-making systems. In agricultural systems where timely actions can significantly affect productivity, minimizing decision-making time is vital. By calculating the average time taken to process decisions, it provides insight into how fast each model can respond to dynamic agricultural data. evaluates a model's ability to handle increasing volumes of data as more IoT devices are integrated into the system. In modern agriculture, where large amounts of data are generated, scalability ensures that models can handle growth without degradation in performance. measures the relationship between input resources and agricultural output, providing insight into how well a model optimizes the use of available resources like water, fertilizers, and computational power. Efficient resource utilization is especially critical in sustainable agriculture, where minimizing waste and maximizing output is a priority. Together, these equations standardize the evaluation process, ensuring a consistent framework for comparing models and facilitating the identification of the most effective solutions for agricultural decision-making.

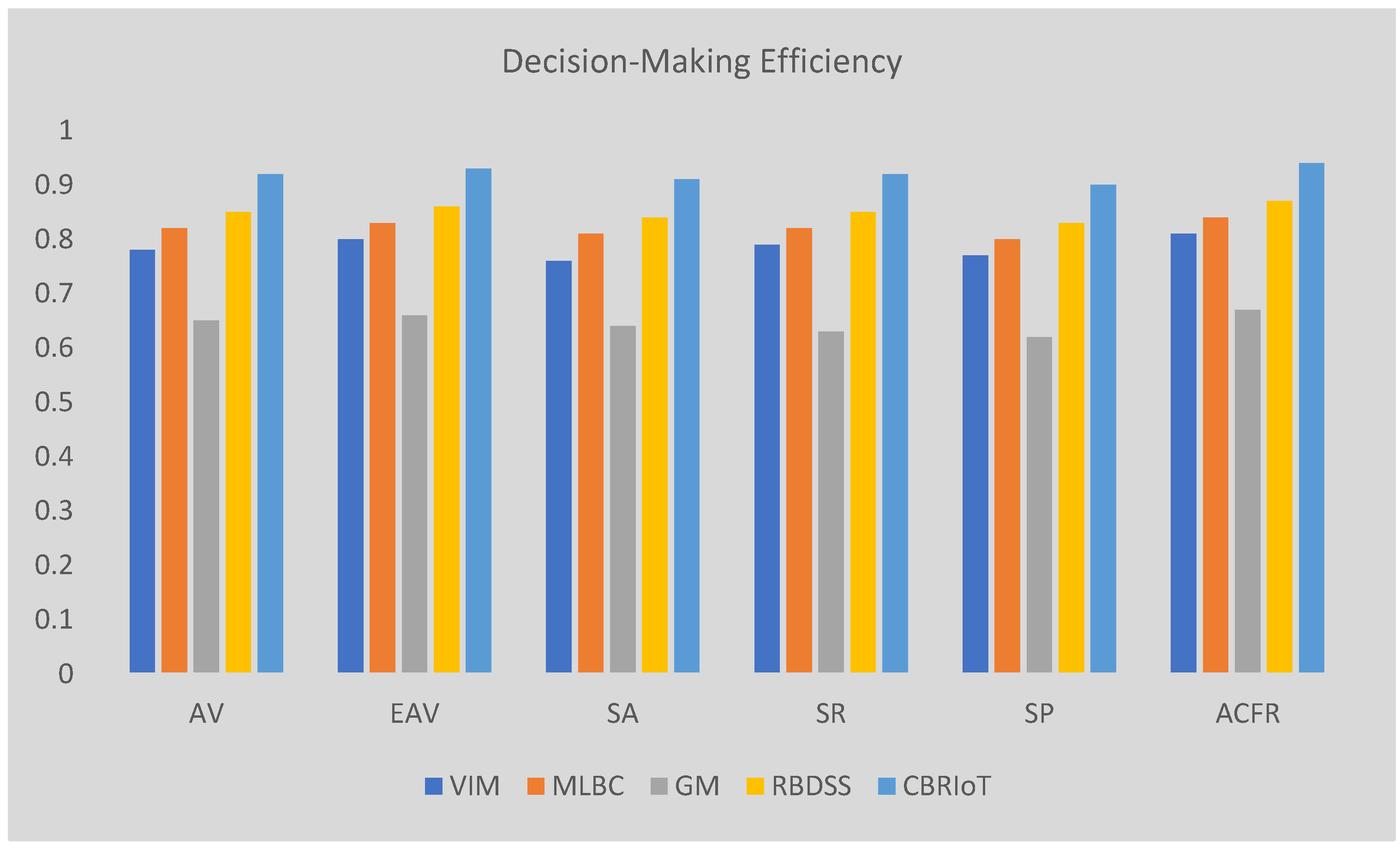

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Comparison of Decision-Making Efficiency.

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Comparison of Decision-Making Efficiency.

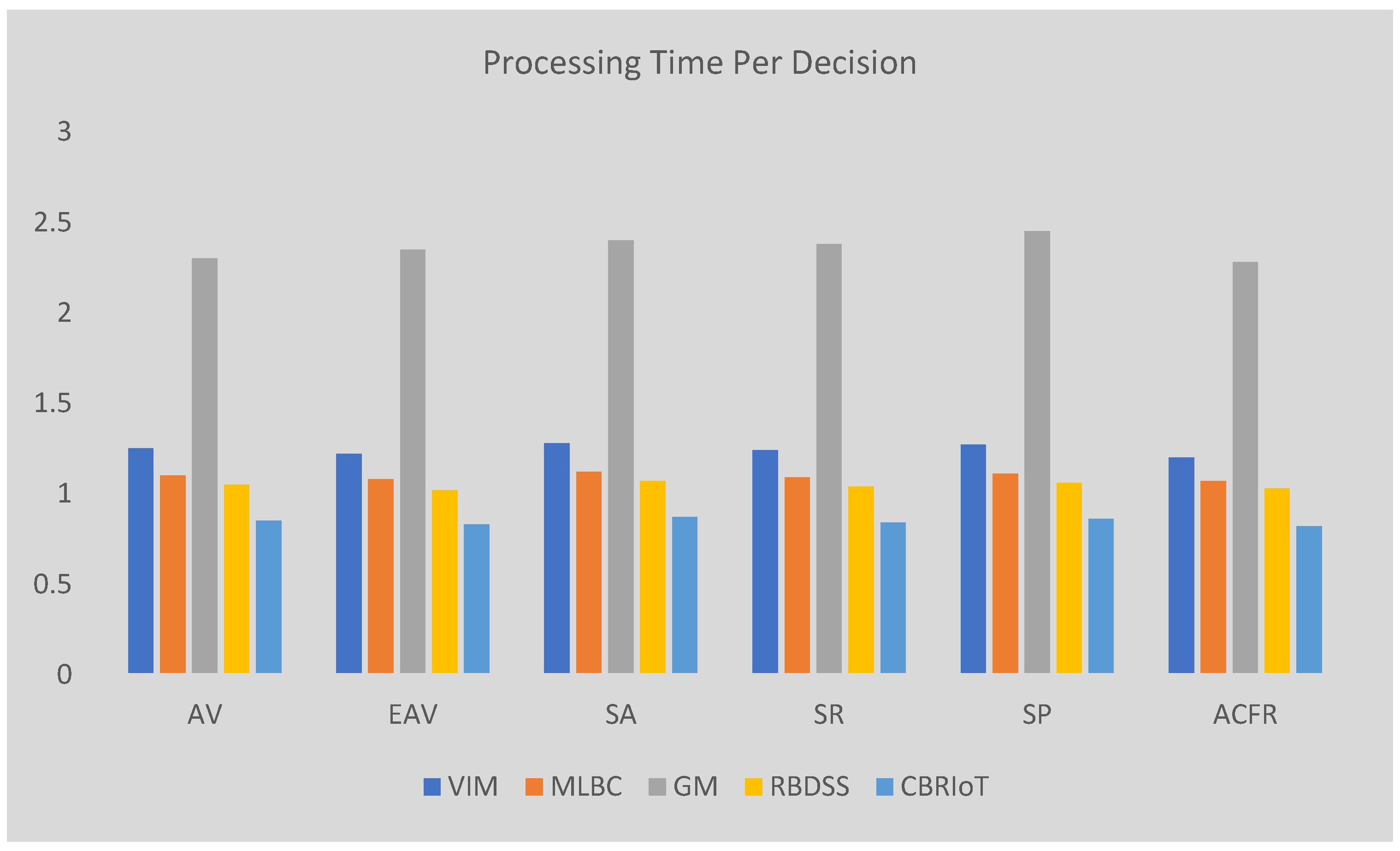

Figure 3.

Comparison of Processing Time Per Decision.

Figure 3.

Comparison of Processing Time Per Decision.

Figure 4.

Comparison of Scalability Index.

Figure 4.

Comparison of Scalability Index.

Figure 5.

Comparison of Resource Utilization Efficiency.

Figure 5.

Comparison of Resource Utilization Efficiency.

4. Results

Decision-making efficiency refers to how effectively each model can arrive at decisions based on the given datasets. In

Table 3, the "VIM" (Vegetation Index Models), "MLBC" (Machine Learning-Based Classification), "GM" (Geostatistical Models), "RBDSS" (Rule-Based Decision Support Systems), and "CBRIoT" (Case-Based Reasoning with IoT) are compared on several datasets: AV (Agricultural Vegetation), EAV (Enhanced Agricultural Vegetation), SA (Soil Analysis), SR (Soil Resources), SP (Soil Properties), and ACFR (Agricultural Crop and Fertility Resources). The values in the table represent the efficiency of the decision-making process for each model.

CBRIoT consistently outperforms the other models across all datasets. For example, in the AV dataset, CBRIoT achieves a decision-making efficiency of 0.92, significantly higher than the other models. This indicates that CBRIoT is the most effective at utilizing data to make accurate, reliable decisions in real time, which is crucial for agricultural decision-making. Models like RBDSS, VIM, and MLBC follow closely, but their efficiency scores are generally lower. GM, although a useful model for spatial analysis, lags behind in terms of decision-making efficiency. This suggests that while CBRIoT leverages IoT data to enhance real-time decisions, the other models focus on specific data types or are more static in their decision-making approach.

Processing time per decision measures how quickly each model can process the available data and generate actionable outcomes. In

Table 4, the dataset values for each model reflect the time required to make decisions based on the input data. Models like CBRIoT show the shortest processing times, indicating that it can efficiently process data and generate decisions faster than the other models. For example, in the AV dataset, CBRIoT takes only 0.85 units of time to make a decision, significantly quicker than models like GM, which takes 2.3 units of time.

The short processing time in CBRIoT is largely attributed to its efficient handling of real-time IoT data, which allows the model to make decisions faster without sacrificing the quality of its outputs. On the other hand, models like GM, which rely on spatial data and statistical techniques, tend to have longer processing times as they require more computational resources and time to analyze complex datasets. RBDSS also has relatively short processing times, but not as low as CBRIoT. This highlights the potential of CBRIoT to provide rapid decision-making support, which is vital in agricultural environments where timely responses can improve productivity and minimize losses.

The scalability index reflects the ability of each model to perform efficiently as the dataset size increases.

Table 5 compares the scalability of VIM, MLBC, GM, RBDSS, and CBRIoT across different datasets. CBRIoT consistently shows the highest scalability, with values close to 1 in all datasets, such as 0.95 in the AV dataset. This suggests that CBRIoT is highly capable of handling large and complex datasets without a significant loss in performance. Its strong scalability is due to its reliance on case-based reasoning, which allows the model to adapt and process new information efficiently as the amount of data grows.

In contrast, GM shows lower scalability, particularly in datasets like EAV and ACFR, where its values are around 0.4-0.45. This indicates that GM struggles with handling large datasets due to the complexity of spatial data and the need for interpolation techniques, which can be computationally intensive. RBDSS and VIM also show moderate scalability but still lag behind CBRIoT. MLBC demonstrates good scalability, but it may require additional computational resources as the dataset increases. Overall, CBRIoT stands out as the most scalable model, making it highly suitable for large-scale agricultural applications where data volume and complexity continue to grow.

Resource utilization efficiency refers to how effectively each model uses computational resources (such as memory and processing power) to deliver results. In

Table 6, CBRIoT demonstrates the highest resource utilization efficiency across all datasets. For example, in the AV dataset, CBRIoT achieves a resource utilization efficiency of 0.95, indicating that it effectively utilizes resources while delivering accurate decisions. This efficiency is crucial in agricultural applications, where there may be limited access to high-end computational infrastructure, especially in rural areas.

In comparison, models like GM have lower resource utilization efficiency, with values as low as 0.35 in the ACFR dataset. GM’s reliance on spatial data and advanced techniques such as kriging requires more memory and processing power, making it less efficient in utilizing resources. Similarly, models like VIM and MLBC also show lower efficiency in comparison to CBRIoT. The ability of CBRIoT to perform well in terms of resource efficiency means it can be deployed in real-time systems that rely on IoT devices and sensors, making it a more practical choice for precision agriculture. Efficient use of resources ensures that farmers can implement these systems without the need for expensive infrastructure or excessive power consumption, further enhancing the accessibility and practicality of CBRIoT in agricultural decision-making.

5. Discussion

In exploring the integration of Case-Based Reasoning (CBR) and Internet of Things (IoT) in agricultural remote sensing, the research questions (RQ) and research objectives (RO) provide a clear framework for guiding the development, evaluation, and application of this approach. RQ(O)1, by analyzing previous cases and applying them to current scenarios, CBR can assist in making context-specific decisions in real-time. This enhances the precision of agricultural practices, including irrigation, fertilization, pest control, and overall crop management. The key focus is on how CBR adapts past knowledge to evolving conditions, improving the overall decision-making process in agricultural operations. RQ(O)2, IoT technology allows for continuous monitoring of variables such as soil moisture, temperature, and crop health, which can feed into a CBR system. This integration facilitates adaptive learning, where the system can improve its decision-making over time based on incoming real-time data. The primary objective is to assess how this hybrid approach enables timely, context-aware decisions that can optimize agricultural practices and resource management, improving both productivity and sustainability. RQ(O)3, Rule-Based Decision Support Systems (RBDSS), and Geostatistical Models (GM). This includes assessing key factors like decision-making accuracy, processing time per decision, and scalability to handle large datasets. Based on the provided tables, it’s evident that CBRIoT outperforms traditional models in these areas. This research will aim to quantify these improvements, demonstrating how the hybrid system offers faster, more accurate, and scalable solutions for precision agriculture, thereby encouraging its adoption for large-scale agricultural applications. RQ(O)4, challenges could include issues related to data integration, connectivity, sensor calibration, and maintaining real-time data streams in remote areas. Moreover, farmers and agricultural stakeholders may face difficulties in adapting to these advanced technologies, especially in regions with limited technological infrastructure. The aim is to understand these barriers and propose solutions to facilitate the smooth integration of CBR-IoT systems into agricultural operations. The findings will guide the development of practical, scalable systems that can be widely adopted by farmers, contributing to improved resource utilization and increased agricultural productivity. By addressing these research questions and objectives, the study aims to advance the field of agricultural decision-making, providing a comprehensive evaluation of how CBR, when integrated with IoT, can transform precision agriculture. The findings will offer valuable insights into both the theoretical and practical aspects of using this technology to enhance agricultural sustainability and productivity.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, the integration of CBR with IoT technologies presents a highly promising approach to enhancing decision-making efficiency in agriculture. By leveraging real-time environmental data from IoT devices such as soil moisture sensors, weather stations, and drones, this model facilitates a dynamic, adaptive, and context-aware decision-making process that can significantly improve agricultural practices. The CBR system's ability to retrieve and adapt solutions from past agricultural cases, based on current environmental conditions, provides farmers with personalized recommendations that are both timely and relevant. This ability to continuously update the knowledge base with new data and interventions enhances the system’s capacity for long-term learning, ensuring that the decision-making process becomes more accurate and effective over time. The comparison of the CBRIoT model with traditional models such as Vegetation Index Models (VIM), Machine Learning-Based Classification (MLBC), Geostatistical Models (GM), and Rule-Based Decision Support Systems (RBDSS) demonstrates its superior performance across several key metrics, including decision-making efficiency, processing time, and scalability. The model outperforms its counterparts by providing more accurate decisions with reduced processing times, enabling farmers to respond more quickly to changing conditions such as weather shifts, pest infestations, or crop health issues. The scalability index also highlights the CBRIoT model’s potential to handle large-scale agricultural data, making it a versatile tool for diverse farming contexts. As agriculture continues to adopt digital technologies, the CBRIoT approach provides a robust framework for integrating traditional knowledge with real-time data, fostering better decision-making and resource management. The ability to dynamically adjust recommendations based on current conditions not only enhances operational efficiency but also supports sustainable agricultural practices by promoting efficient resource use. Furthermore, the continuous learning and self-improvement aspect of the model ensures that the system becomes more refined with each decision cycle, ultimately driving improved outcomes for crop management and overall farm productivity. By offering actionable insights in a user-friendly interface, the CBRIoT system can empower farmers to make informed, data-driven decisions that improve yields and reduce costs. This approach has the potential to revolutionize the agricultural industry, enabling farmers to navigate the complexities of modern agriculture with enhanced precision and efficiency. As this model continues to evolve and adapt, it can play a significant role in addressing global food security challenges, ensuring that agricultural systems are more resilient, sustainable, and capable of meeting the growing demands of the world’s population.

Future work in the integration of CBR with IoT for agriculture holds significant potential for further enhancement and expansion. One promising direction is the development of more advanced data fusion techniques to integrate data from a wider variety of sources, such as satellite imagery, soil sensors, and climate data, with greater accuracy and speed. This could enable a more comprehensive understanding of agricultural conditions and improve the system’s predictive capabilities. Additionally, expanding the scope of the case library by incorporating more diverse agricultural scenarios from different regions and crop types will enhance the system’s adaptability and applicability to various farming environments. Another area for development is the incorporation of advanced machine learning algorithms, such as deep learning, to refine the similarity matching process, enabling the system to identify even more subtle patterns in data and improve the relevance of retrieved cases. Real-time data processing and predictive analytics could be further optimized by integrating edge computing, allowing for faster data analysis and decision-making at the point of collection, reducing reliance on centralized cloud processing. The user interface can also be improved by adding more interactive and customizable features, providing farmers with tailored insights and easier-to-understand visualizations. Lastly, there is room for greater collaboration with agricultural research institutions to enhance the system’s knowledge base with the latest scientific findings, fostering continuous learning and innovation in agricultural practices. These advancements could lead to more intelligent, efficient, and scalable agricultural solutions that are better equipped to address global challenges such as climate change, resource scarcity, and food security.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.L.; methodology, T.L.; formal analysis, T.L., investigation, T.L.; writing (original draft) T.L. and S.S., writing (review and editing), T.L. and S.S.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Benaly, M.A.; Brouziyne, Y.; Kharrou, M.H.; Chehbouni, A.; Bouchaou, L. Crop modeling to address climate change challenges in Africa: status, gaps, and opportunities. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Chang. 2025, 30, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Guan, H.; Li, Y.; Bruzzone, L. Deep learning change detection techniques for optical remote sensing imagery: Status, perspectives and challenges. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 2024, 136, 104282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.M.; Ndeffo, L.N. Understanding the nexus: economic complexity and environmental degradation in Sub-Saharan Africa. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2024, 27, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafiz, R.B.; Noguchi, R.; Ahamed, T. Agricultural Land Suitability Assessment Using Satellite Remote Sensing-Derived Soil-Vegetation Indices. Land 2021, 10, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Yang, C.; Huang, W.; Tang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q. Machine learning-based crop recognition from aerial remote sensing imagery. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 15, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varouchakis, E.A.; Kamińska-Chuchmała, A.; Kowalik, G.; Spanoudaki, K.; Graña, M. Combining Geostatistics and Remote Sensing Data to Improve Spatiotemporal Analysis of Precipitation. Sensors 2021, 21, 3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, M.; Negi, R.; Ravi, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Dutta, A.; Sahoo, S.; Panotra, N.; Ivakumar, K.; K, S.; Kumar, H.; Singh, B.V. Empowering Small-Scale Vegetable Farmers with Drone-based Decision Support Systems for Sustainable Production. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Chang. 2025, 15, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Agarwal, S.; Agrawal, N.K.; Agarwal, A.; Garg, M.C. A Comprehensive Review of Remote Sensing Technologies for Improved Geological Disaster Management. Geol. J. 2024, 60, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, B.K.; Deshpande, T.; Pal, A.; Kothandaraman, S. Critical regions identification and coverage using optimal drone flight path planning for precision agriculture. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 104081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskandari, S.; Bordbar, S.K. Provision of land use and forest density maps in semi-arid areas of Iran using Sentinel-2 satellite images and vegetation indices. Adv. Space Res. 2024, 75, 2506–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gong, Z.; Hu, C.; Chen, C.; Wang, Z.; Yu, B.; Suo, J.; Jiang, C.; Lv, C. A Transformer-Based Detection Network for Precision Cistanche Pest and Disease Management in Smart Agriculture. Plants 2025, 14, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, D.; Rafiq, S.; Saini, P.; Ahad, I.; Gonal, B.; Rehman, S.A.; Rashid, S.; Saini, P.; Rohela, G.K.; Aalum, K.; et al. Remote sensing and artificial intelligence: revolutionizing pest management in agriculture. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1551460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosavi, S.V.; Radfar, R.; Setayeshi, S. Development of a Fuzzy Case-Based Reasoning Decision Support System for Water Management in Smart Agriculture. Manag. Strat. Eng. Sci. 2025, 7, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Lei, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, B.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, D. Intelligent Recommendation of Multi-Scale Response Strategies for Land Drought Events. Land 2024, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A, S.G.; Suganthi, S.; Prinslin, L.; Selvi, R.; Prabha, R. Generative AI in Agri: Sustainability in Smart Precision Farming Yield Prediction Mapping System Based on GIS Using Deep Learning and GPS. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2025, 252, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayvargia, K.; Saxena, P.; Bhilare, D.S. Context Management Life Cycle for Internet of Things: Tools, Techniques, and Open Issues. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2025, 15, 19449–19459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifeh, A.F.; Alqammaz, A.; Khasawneh, A.M.; Abualigah, L.; Darabkh, K.A.; Zinonos, Z. An environmental remote sensing and prediction model for an IoT smart irrigation system based on an enhanced wind-driven optimization algorithm. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 122, 109889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Jiang, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Ercisli, S.; Lv, L. Data and domain knowledge dual-driven artificial intelligence: Survey, applications, and challenges. Expert Systems 2025, 42, e13425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y. B., Chen, D., & Zhang, Z. Y. (2024, July). A conditional generative adversarial networks-augmented case-based reasoning framework for crop yield predictions with time-series remote sensing data. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Case-Based Reasoning (ICCBR), Merida, Mexico (Vol. 3708, pp. 192-205).

- Xu, J.; Li, J.; Peng, H.; He, Y.; Wu, B. Information Extraction from High-Resolution Remote Sensing Images Based on Multi-Scale Segmentation and Case-Based Reasoning. Photogramm. Eng. Remote. Sens. 2022, 88, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilito, E.D.L.; Olaya, J.F.C.; Corrales, J.C.; Figueroa, C. Sustainability-driven fertilizer recommender system for coffee crops using case-based reasoning approach. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 8, 1445795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, A.; Cheng, Z. A Review of the Development and Future Challenges of Case-Based Reasoning. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapra, V.; Sapra, L.; Bhardwaj, A.; Bharany, S.; Saxena, A.; Karim, F.K.; Ghorashi, S.; Mohamed, A.W. Integrated approach using deep neural network and CBR for detecting severity of coronary artery disease. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 68, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L. A Generalization Sample Learning Method of Deep Learning for Semantic Segmentation of Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote. Sens. 2023, 61, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Chen, J.; Xu, K.; Xie, H.; Gan, X.; Xu, H. A spatial case-based reasoning method for regional landslide risk assessment. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 2021, 102, 102381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorodnykh, N.; Nikolaychuk, O.; Pestova, J.; Yurin, A. Forest Fire Risk Forecasting with the Aid of Case-Based Reasoning. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Zhang, W.; Wu, S. Classification algorithm for land use in the giant panda habitat of Jiajinshan based on spatial case-based reasoning. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1298327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Qu, R.; Fang, W. Case-based reasoning system for fault diagnosis of aero-engines. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 202, 117350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Wu, H. Prediction of network public opinion features in urban planning based on geographical case-based reasoning. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2022, 15, 890–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canlas, F.Q.; Al Falahi, M.; Nair, S. IoT based Date Palm Water Management System Using Case-Based Reasoning and Linear Regression for Trend Analysis. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Guo, H.-X.; Zhu, J.; Shi, Y. Dynamic selection of emergency plans of geological disaster based on case-based reasoning and prospect theory. Nat. Hazards 2021, 110, 2249–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, L.R.; Oldoni, H.; Baptista, G.M.M.; Ferreira, G.H.S.; Freitas, R.G.; Martins, C.L.; Cunha, I.A.; Santos, A.F. Remote sensing imagery to predict soybean yield: a case study of vegetation indices contribution. Precis. Agric. 2024, 25, 2375–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, D.; Di, L.; Zhang, C.; Yang, R.; Qu, J.J.; Tong, D.; Guo, L.; Lin, L.; Pandey, A. A Decision Rule and Machine Learning-Based Hybrid Approach for Automated Land-Cover Type Local Climate Zones (LCZs) Mapping Using Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote. Sens. 2024, 17, 8271–8290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, O.A.; Sharma, V.; Kumar, S.S.; Malik, A.R.; Pandey, A.; Devi, K.; Kumar, V.; Gairola, A.; Yadav, D.; Valente, D.; et al. Geostatistical modelling of soil properties towards long-term ecological sustainability of agroecosystems. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ahin, O.; Topaloğlu, F. Development of Rule-Based Expert System for Variable Cost and Gross Profit Calculations of Agricultural Products: A Case Study. Anadolu Tarım Bilimleri Dergisi 2024, 39, 365–379. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, D.; Kang, T.; Jang, J. Papers with code or without code? Impact of GitHub repository usability on the diffusion of machine learning research. Inf. Process. Manag. 2023, 60, 103477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrhardt, S.E.; Ballard, T.; Wards, Y.; Mattingley, J.B.; Dux, P.E.; Filmer, H.L. tDCS augments decision-making efficiency in an intensity dependent manner: A training study. Neuropsychologia 2022, 176, 108397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagui, S.; Walauskis, M.; DeRush, R.; Praviset, H.; Boucugnani, S. Spark Configurations to Optimize Decision Tree Classification on UNSW-NB15. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2022, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, S.; Shah, S.A.; Saeed, Q.S.; Siddiqui, S.; Ali, I.; Vedeshin, A.; Draheim, D. A Scalable Key and Trust Management Solution for IoT Sensors Using SDN and Blockchain Technology. IEEE Sensors J. 2021, 21, 8716–8733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dilanchiev, A. Economic recovery, industrial structure and natural resource utilization efficiency in China: Effect on green economic recovery. Resour. Policy 2022, 79, 102958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).