1. Introduction

The need for sustainable food production has intensified in response to challenges such as climate change, urbanization, and water scarcity. Indoor farming has emerged as a promising solution, offering year-round crop production through controlled environments that optimize light, temperature, humidity, and nutrient delivery [

1]. This approach, powered by advancements in IoT sensors, artificial lighting, and automated controls, enables growers to achieve higher yields, efficient resource utilization, and improved crop quality [

2,

3].

The role of technology in indoor farming has expanded significantly, with cloud com-puting and AI-driven analytics now pivotal in enhancing resource optimization and crop monitoring. For example, AI algorithms enable predictive insights for efficient resource allocation [

4], while cloud-based IoT systems facilitate real-time environmental monitoring [

5]. Despite these advancements, limited attention has been given to scalable data integration frameworks—such as ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) pipelines—which are crucial for managing the vast amounts of data generated by IoT devices, sensors, and imaging systems.

This paper aims to bridge this gap by presenting a comprehensive framework that combines advanced ETL solutions, cloud analytics, and machine learning to enhance data-driven decision-making in agriculture. The proposed framework integrates IoT sensors with cloud-based platforms using robust ETL tools (specifically, Apache NiFi) to enable real-time data ingestion, transformation, and analysis. Machine learning models (SVM, Gradient Boosting, and DNN) analyzed 12 weeks of IoT sensor data (light, moisture, nutrients) to predict growth trends and optimize thresholds. Algorithms were trained on real-time sensor data and corresponding growth metrics to predict yields, classify conditions, and quantify factor contributions. Lettuce, a model crop for controlled environments, was chosen to validate the pipeline.

In addition, we introduce the Integrated Agricultural Efficiency Metric (IAEM), a novel framework that aggregates insights from resource efficiency, alert accuracy, data latency, and cloud data availability. The IAEM metric aggregated these insights, demonstrating a 32% improvement in resource efficiency. By leveraging scalable and efficient data pipelines together with predictive analytics, this study highlights the transformative potential of integrating technological innovations to achieve sustainable and productive indoor farming systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. IoT-Driven Processing and Integration Pipeline

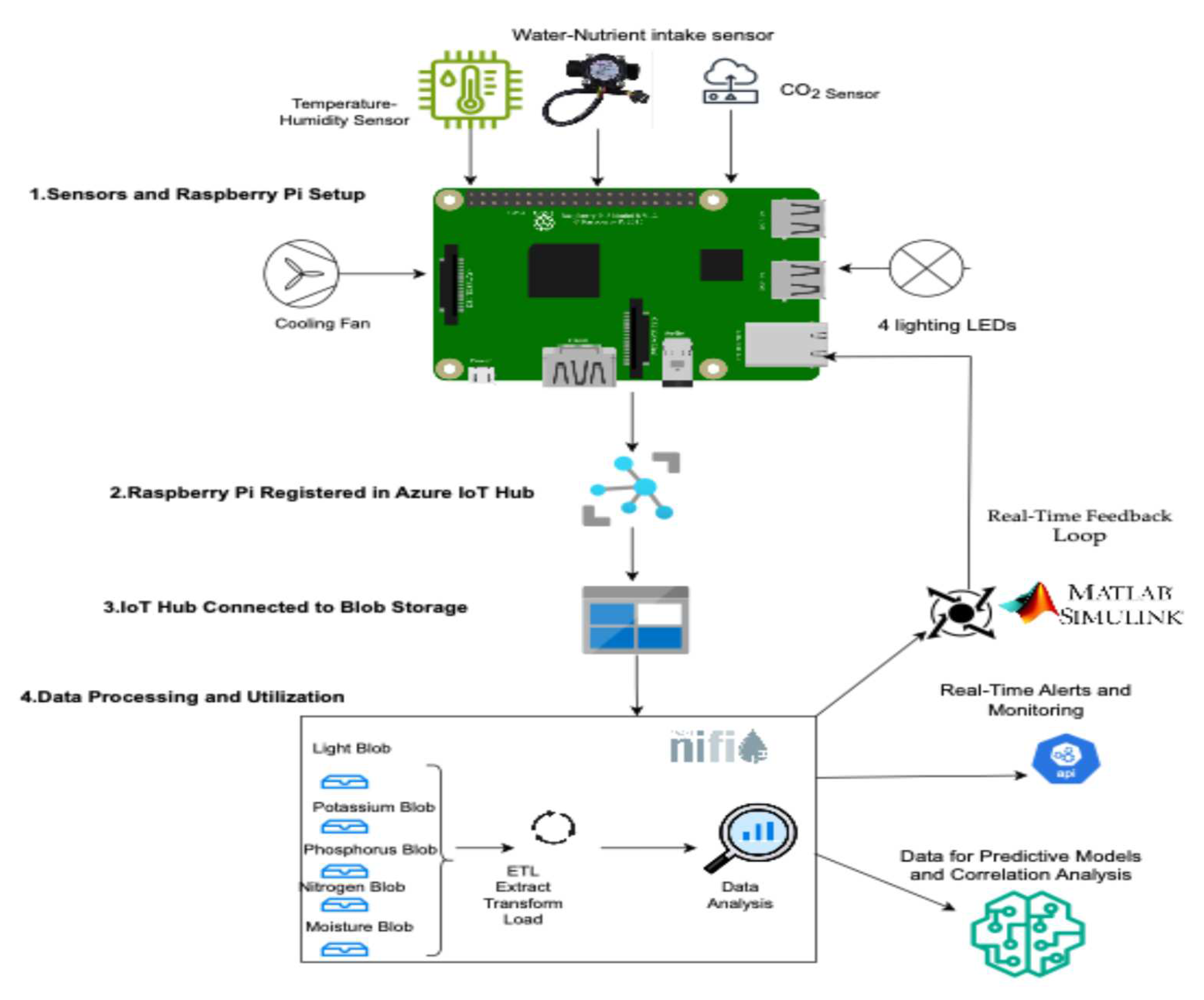

The Internet of Things (IoT) enables real-time monitoring through the connected sensors. In our study case, IoT sensors were used to measure key environmental parameters including light intensity, moisture, temperature, and nutrient levels. We connected these IoT sensors as shown in

Figure 1 to Raspberry Pi device via GPIO (General Purpose Input/Output) pins which act as a device for IoT data collection and transmission to a cloud-based storage system [

6].

Each sensor captures a specific environmental metric:

Light Sensors: Monitor light intensity to ensure optimal exposure for photosynthesis.

Moisture Sensors: Measure soil moisture levels to prevent over- or under-watering.

Temperature-Humidity Sensors: Track ambient conditions crucial for maintaining favorable growing environments.

CO₂ Sensors: Monitor carbon dioxide concentrations to optimize photosynthetic efficiency.

Water-Nutrient Intake Sensors: Analyze nutrient levels, including potassium, phosphorus, and nitrogen, to ensure a balanced supply.

2.1.1. Data Storage of IoT Devices

To manage the real-time data collected from sensors, we used Azure Event Hub which is a service provided by the Cloud provider Azure as the data receiver platform [

7]. The Raspberry Pi device is registered as an IoT device within Azure IoT Hub [

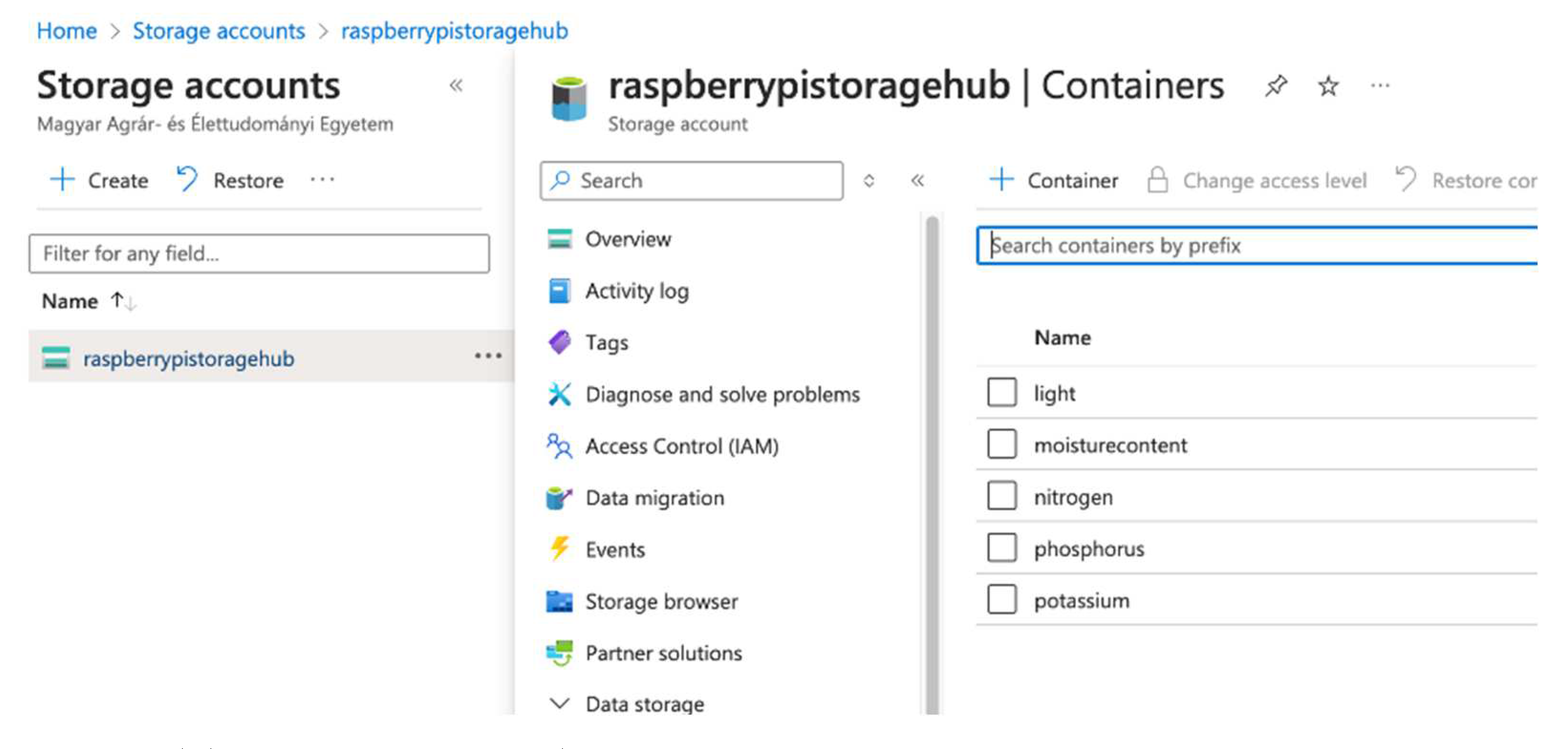

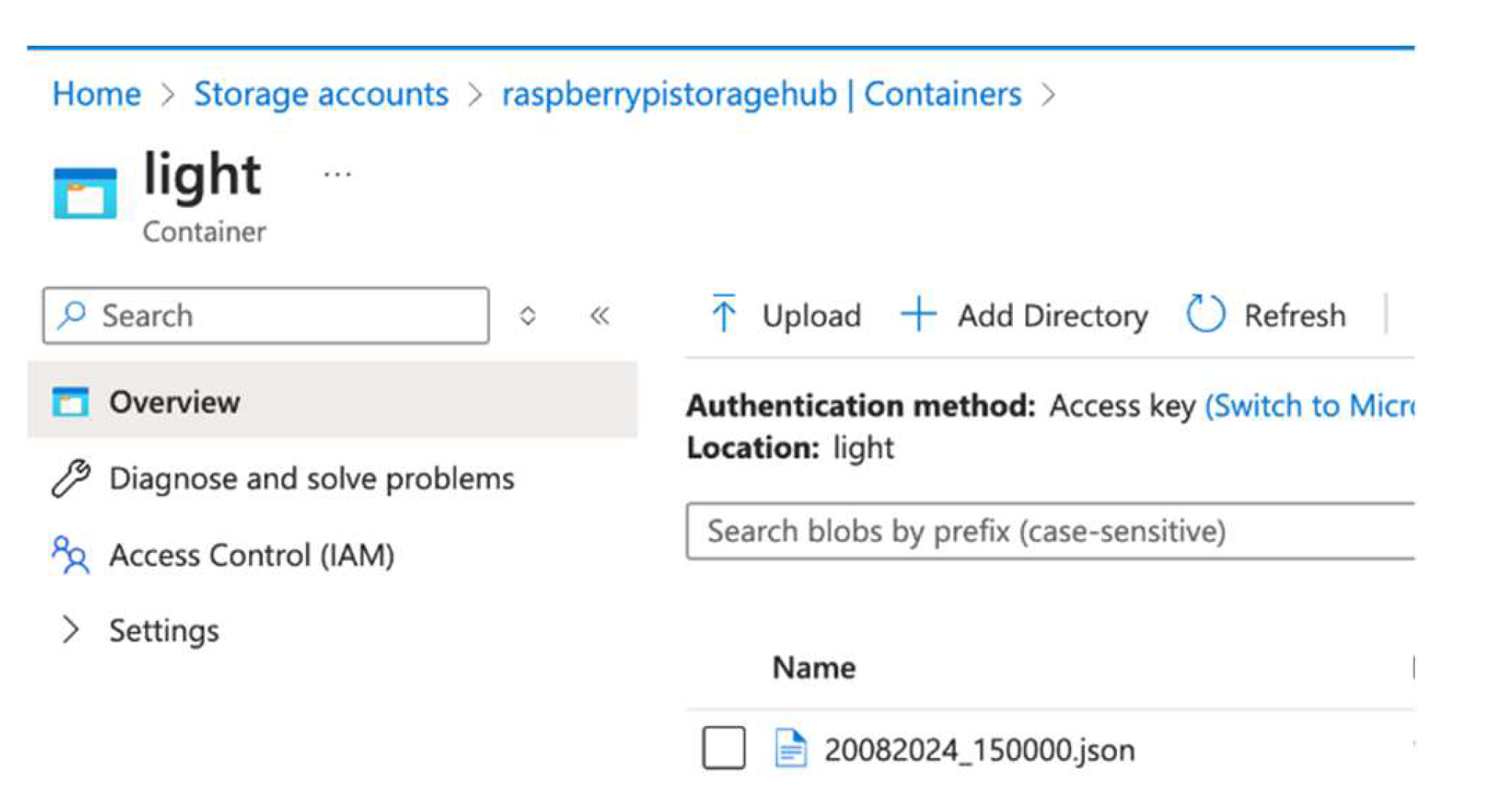

8], enabling secure communication between the device and the cloud platform. The data for this study were collected between April 2024 and September 2024. The data was collected in a predefined interval which is every one hour and sends this data to Azure Event Hub via the IoT Hub. Each sensor reading arrives in json file where the content is the values of the parameters and a set of attributes like a timestamp and device identifier to ensure traceability and accuracy. Once the sensor data is processed and transmitted to Azure Event Hub, it is stored in Azure Blob Storage. Each sensor's data is organized into its dedicated container based on the sensor type as shown in the Figure2 below.

2.1.2. Correlation Analysis

We decided to compute the correlation between these factors and plant growth to evaluate how effectively the IoT system optimizes these variables to enhance crop yield. This analysis helped us measure the efficiency of the IoT system in real-time. We want to calculate the Pearson Correlation Coefficient between the growth of lettuce and each of these inputs. The Pearson correlation coefficient measures the strength and direction of a linear relationship between two variables [

9], it is given in Equation (1):

X: is the individual environmental input (light, moisture, etc.).

Y: is the plant growth data.

are the means of the respective variables.

2.1.3. Cloud-Based Data Processing and Analytics

Apache Nifi automates the process of retrieving sensor data from Azure Blob Storage and comparing it against predefined thresholds [

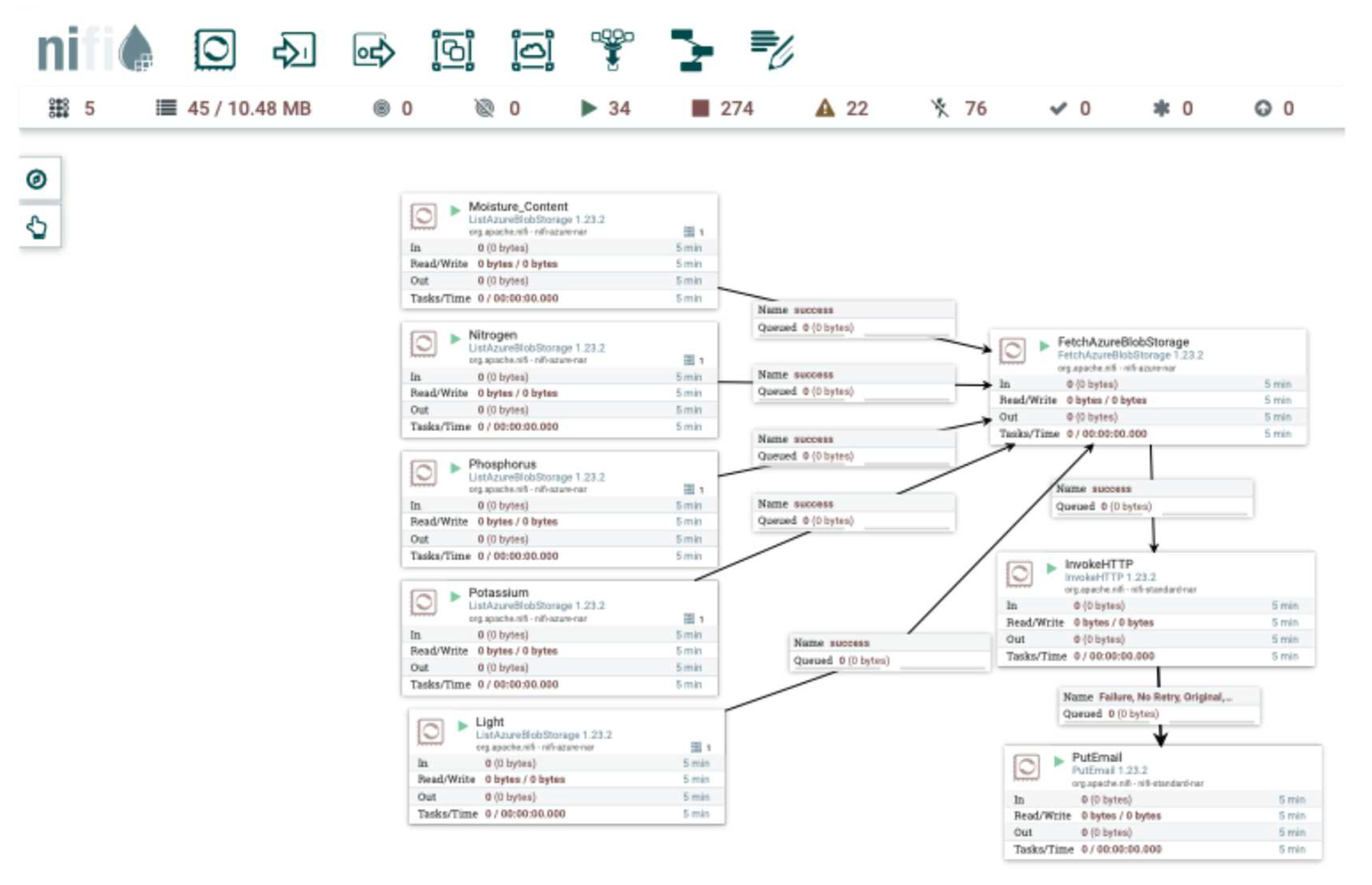

10]. The data flow as shown in

Figure 3 starts with the ListBlob and FetchBlob processors, which are used to fetch sensor data. After retrieving the data, the InvokeHTTP processor is set up to send the entire JSON payload, retrieved from the blob, directly to an API.

The HTTP request body contains the JSON data that is a json input, for example: ({ "Moisture_Content": 20, "Nitrogen": 30, "Light": 80 }),then the API compares the sensor data against predefined thresholds, such as minimum water levels or optimal nutrient concentrations. The API's response indicates whether everything is within acceptable ranges or if an issue has been detected. The response typically comes back with either a message indicating " All levels are fine " or an alert such as { "alert": " Light is outside the optimal range " }. Based on the response, NiFi triggers the PutEmail processor, allowing the system to inform when environmental conditions need immediate attention. This automated flow ensures continuous monitoring, immediate comparisons with critical thresholds, and real-time alerts or responses to prevent issues such as insufficient water or poor nutrient levels in the monitored environment.

2.2. AI-Driven Predictive Modeling and Parameter Computation in Crop Management

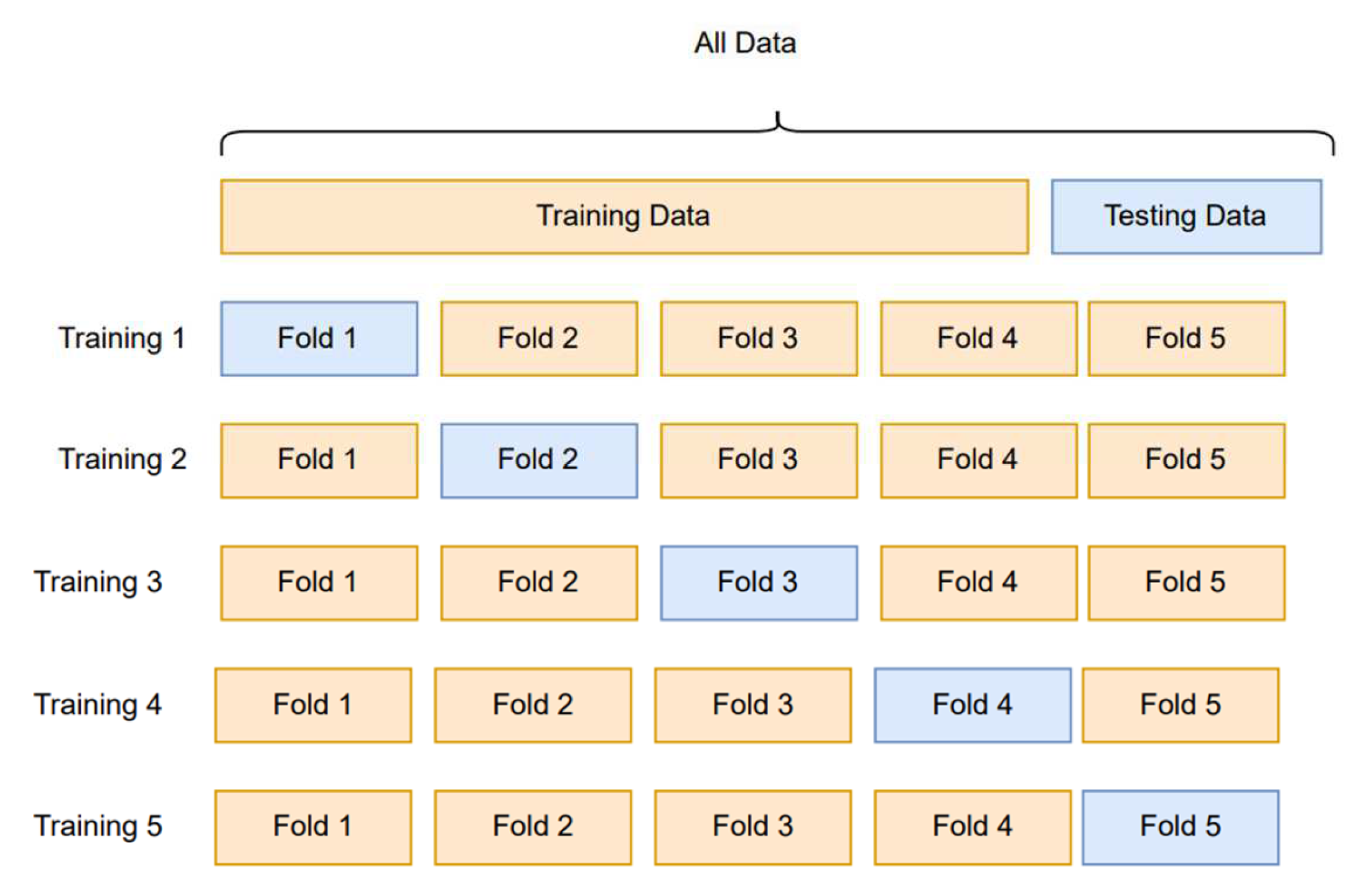

All models in this study were trained and evaluated using a standardized methodology shown in

Figure 4 to ensure a consistent and fair comparison. The dataset was first preprocessed to address class imbalances through a combination of oversampling for minority classes and undersampling for majority classes. This preprocessing step ensured that the dataset was balanced, enabling the models to learn effectively from both classes

The data was then divided into two subsets: Training Data (80%), represented in yellow, and Test Data (20%), represented in blue in

Figure 5. The training data was further split into five folds for 5-fold cross-validation, where each fold served as the validation set once while the remaining folds were used for training.

The model was trained five times, with each iteration using a different fold for validation. This repeated process ensured that every data point in the training set was used for both training and validation. The consistent application of this approach improved the models' robustness and generalizability.

2.2.1. Predictive Modeling

Support Vector Machines (SVM)

Support Vector Machines (SVMs) are a class of supervised learning algorithms designed to solve classification problems, particularly binary classification tasks [

11]. The goal of SVMs is to find a decision boundary that separates data into two classes, ensuring the boundary is as far as possible from the nearest data points in each class, thereby maximizing the margin. This approach improves the generalization ability of the model.

Instead of directly mapping inputs X to binary outputs Y∈{−1,1}, SVMs construct a real-valued classifier f:X→R, where the predicted class is determined by the sign of f(X).

The margin, defined as Y⋅f(X), provides an intuitive measure of confidence in the classification. The optimization problem aims to minimize the norm of the weight vector ∣∣w∣∣, subject to constraints that ensure correct classification of training examples, expressed in Equation (3).

To address non-linear separability, SVMs transform input data into higher-dimensional feature spaces using kernel functions, where a linear decision boundary can effectively separate the data. The optimization problem is then solved using quadratic programming with Lagrange multipliers, leveraging the dual formulation. SVMs are particularly effective in high-dimensional spaces and offer robust performance for classification problems, ensuring a balance between underfitting and overfitting through careful margin maximization and regularization.

Deep Neural Networks (DNN)

Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) are a class of machine learning algorithms designed to model complex, non-linear relationships between input features and output targets [

12]. A DNN consists of multiple layers, including an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. Each layer is composed of interconnected neurons, where each connection is assigned a weight and a bias term.

The training of DNNs involves Forward Propagation where the input data is passed through the network, and the output at each layer is computed using a combination of weighted sums and a non-linear activation function; Loss Calculation where the network output is compared to the target output using a loss function and Backpropagation where the loss is propagated backward through the network, layer by layer, to update the weights and biases using gradient descent.

The architecture used in our study consisted of fully connected feed-forward layers, trained using a stochastic gradient descent optimizer to minimize the chosen loss function. The DNN was designed to capture non-linear relationships between environmental parameters and crop growth, enabling it to make accurate predictions based on the input data.

Gradient Boosting

Gradient Boosting is an ensemble machine learning technique designed to solve both regression and classification problems. The method builds a strong predictive model by combining multiple weak learners, such as decision trees, in an iterative manner. Each new learner is trained to correct the residual errors made by the previous ones, progressively improving the model’s accuracy [

13].

The technique minimizes a predefined loss function ℓ(f), which measures the error between the predicted and actual values. At each iteration, the model adds a new weak learner

, scaled by a learning rate α, to the current ensemble

, following the update rule in Equation (4):

The weak learner is trained to approximate the negative gradient of the loss function, which represents the residuals. To handle non-linear relationships and complex patterns, Gradient Boosting relies on decision trees as weak learners. These trees partition the feature space into regions that approximate the residuals with minimal error. The iterative nature of the algorithm allows it to adaptively refine predictions by focusing on the hardest-to-predict data points. Gradient Boosting offers flexibility in selecting the loss function and hyperparameters, making it a powerful tool for diverse machine learning tasks. It is particularly effective in applications requiring high accuracy and robust handling of non-linear data.

2.2.2. Parameter Computaion

Time Series Analysis

In order to better identify patterns and make projections for future growth and planning based on historical performance, we used time-series regression that allows us to model plant growth as a function of environmental factors over time. The general model is shown in Equation (5):

t: Time (daily intervals); a(t),b(t), , , ,d(t) : Dynamic changes in growth conditions.

Time Series Analysis is a statistical technique that models data points collected over time to capture trends, seasonal patterns, and cyclic behaviors. It can also predict future values based on past data, by analyzing the relationships between historical data points and accounting for random fluctuations [

14]. In our case, we used IoT sensors that constantly sent real-time data into the cloud. The system can automatically predict plant growth and suggest optimal conditions (such as light intensity or moisture levels) to maximize yield over time [

15].

Multivariate Regression for Resource Contributions

In order to quantify the relationship between the independent variables (light, moisture, temperature, nutrients) and the dependent variable (plant growth) we used the multivariate linear regression [

16].

The model used is a statistical technique that helps in estimating the relationship between multiple independent variables and a dependent variable, the predicted growth is calculated using Equation (6):

Multivariate linear regression

Where:

a,b, , , , d : The coefficients that represent the effect of light, moisture, and nutrients on plant growth; ϵ: The error term, which accounts for variability not explained by the model.

Mathematically, the regression model is solved by minimizing the following function in Equation (7):

Growthi is the actual plant growth on day ; the predicted growth from the regression model on day .

We used a Python script to implement the multivariate linear regression model that calculated the coefficients for the independent variables.

Random Forest Model

The Random Forest model was applied to predict crop yield using four key environmental factors: light intensity, moisture content, temperature, and nutrient levels. The model is an AI model that works by constructing multiple decision trees, each trained on a random subset of the data D, using a random selection of features at each split [

17]. The final prediction ŷ(x') for a new data point x' is obtained by averaging the predictions from all trees

(x') as shown in Equation (8):

where B is the number of trees and

(x’) is the prediction from the b-th tree.

2.2.3. Integrated Agricultural Efficiency Metric (IAEM)

The Integrated Agricultural Efficiency Metric (IAEM) shown in Equation 9 offers a groundbreaking approach to evaluating agricultural system performance by integrating real-time data into a unified framework tailored for technology-driven farming. Unlike Total Factor Productivity (TFP), which measures the long-term ratio of agricultural outputs to inputs and has been widely applied to analyze economic and technological growth [

18], IAEM provides a dynamic evaluation of modern farming operations. Similarly, while the Precision Agriculture Index (PAI) focuses on assessing spatial variability of crop growth using high-resolution remote sensing data [

19], IAEM extends beyond spatial insights to incorporate real-time resource utilization, alert accuracy, and system latency, ensuring a comprehensive assessment of system responsiveness and efficiency. In contrast to statistical metrics like Mean Squared Error (MSE) and R-Squared (R

2), commonly used in regression analysis to measure model fit [

20], IAEM quantifies operational performance, bridging the gap between technical system optimization and agricultural outputs. By integrating sub-metrics such as Resource Efficiency (RE), Real-Time Alert Accuracy (RA), Data Latency (DL), and Cloud Data Availability (CDA), IAEM uniquely addresses gaps in existing metrics, making it a powerful tool for evaluating data-driven agricultural systems in real-time, particularly those utilizing ETL solutions like Apache NiFi.

Metric Scale

IAEM is calculated using normalized metrics for Resource Efficiency (RE), Real-Time Alert Accuracy (RA), Data Latency (DL), and Cloud Data Availability (CDA). The minimum value occurs when RE and RA are minimal, DL is maximal, and CDA is low. The maximum value is reached when RE and RA are maximal, DL is minimal, and CDA is high.

The following scale is the scale we proposed to interpret IAEM values:

Poor Performance: IAEM < 0.1

Indicates significant inefficiencies in resource management, alert accuracy, or latency handling.

Moderate Performance: 0.1 ≤ IAEM < 0.2

Reflects average system performance with room for noticeable improvement.

Good Performance: 0.2 ≤ IAEM < 0.3

Demonstrates effective optimization across metrics but with potential for further fine-tuning.

Excellent Performance: IAEM ≥ 0.3

Represents highly optimized system performance with minimal latency, high accuracy, and efficient resource utilization.

Data Latency Metric (DL)

The metric part in Equation (10) represents the time delay between data generation and actionable insights or system response. Equation shows

Where : Time when the system generates a response for the i-th data point; Time when the i-th data point is generated; Total number of data points processed.

Resource Efficiency (RE)

The metric in Equation (11) quantifies the efficiency of the system in processing data relative to the resources used.

Real-Time Alert Accuracy (RA)

The metric in Equation (12) evaluates the accuracy of real-time alerts generated by the system.

Cloud Data Availability (CDA)

The metric in Equation (13) represents Cloud Data Availability, it shows the ability of a cloud storage system; Azure Blob Storage in our case, to ensure full access to data for read and write operations over a given period. This metric measures the reliability and accessibility of data in the cloud, expressed as a percentage of uptime or successful operations versus total operational time.

Where:

SR = Uptime (%) = Pairwise Comparison algorithm using AHP for weights

In this study, we implemented a Python script to compute the weights of the newly developed metric IAEM in our analysis. The script was adapted to our study and uses the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), a multi-criteria decision-making methodology, and follows a pairwise comparison algorithm designed specifically for this case study. The algorithm in

Figure 5 was designed specifically for this study to calculate weights by constructing a pairwise comparison matrix, normalizing the matrix, and averaging the normalized values to derive the importance of each metric. In the last step, the algorithm incorporates consistency checks to ensure the reliability of the pairwise comparisons.

Figure 5.

Pairwise Comparison Using AHP.

Figure 5.

Pairwise Comparison Using AHP.

2.3. Dataset Structure and Model Inputs

All algorithms were trained on a dataset comprising 12 weeks of IoT sensor data (light intensity, moisture, temperature, nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium) and corresponding plant growth metrics (biomass in grams, height in centimeters). Each data point represents a weekly observation, with environmental variables as inputs and growth metrics as outputs.

Output Targets

Crop yield (g), plant height (cm).

Preprocessing

Data was normalized (z-score) to ensure uniformity across scales.

2.4. MATLAB Simulink for Real-Time Feedback

As mentioned before, NiFi gathers the environmental data and forwards it to a dedicated API that checks these values against the thresholds we predefined during the configuration of the API to assess the health of the plant’s environment.

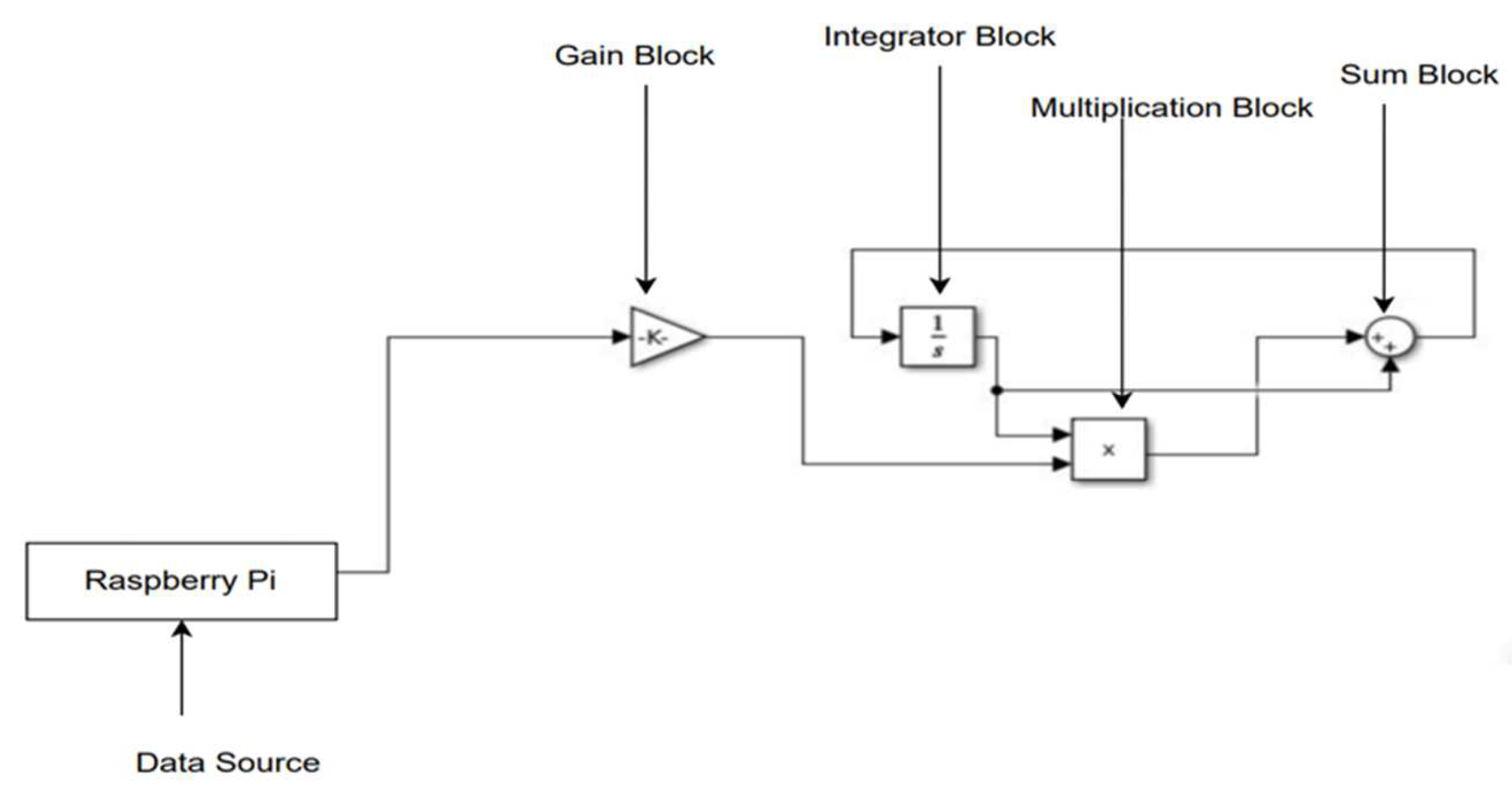

To further enhance this IoT-based environmental monitoring system, we used MATLAB Simulink to model the dynamic growth of plants based on real-time data provided by the IoT sensors [

21],

Figure 6 is the MATLAB Simulink model that represents the feedback control system or growth rate model for our IoT-based plant growth monitoring system. The Gain Block (-k) applies a constant to adjust the growth rate based on sensors data, with a negative feedback mechanism. The Integrator Block (1/s) calculates the total plant size by integrating the growth rate over time. The Multiplication Block (x) multiplies the growth rate by the current plant size to update it. Finally, the Feedback Loop feeds the plant size back into the system to dynamically adjust future growth. We applied the Malthusian Exponential Growth Equation that describes population growth as a continuous exponential increase, where the population grows at a constant rate proportional to its current size, assuming unlimited resources and no external constraints [

22].

To model plant growth under controlled conditions, the Simulink model is representing the plant growth using the differential Equation (2):

The plant growth dynamically adjusts based on sensor data and feedback. In the model:

Where:

P(t): represents the plant size at time t; r(t): is the growth rate at time t, which is influenced by real-time sensor data; k: Gain constant controlling the feedback effect; Input(t): External factor affecting the growth (sensor inputs such as nutrients, light...); The growth rate r(t) is not constant but dynamically adjusts based on the sensor feedback loop.

These real-time adjustments based on sensor feedback make the IoT system highly responsive, optimizing the growth conditions.

2.5. Experimental Setup for Evaluating Plant Growth

This study implemented a 12-week experimental setup to evaluate the effectiveness of an IoT-based system in optimizing indoor plant growth, with lettuce chosen as the test crop due to its fast growth cycle and sensitivity to environmental factors.

During the experiment, a new set of lettuce plants was grown each week, with environmental growing factors including light intensity, moisture content, temperature, and nutrient levels systematically controlled and varied weekly as shown in

Appendix A. The growth metrics for each weekly set were recorded at the maturity level to ensure a comprehensive analysis of the relationship between environmental conditions and lettuce development. This approach allowed for a robust assessment of how each unique setup influenced plant growth and validated the system's ability to adapt to varying conditions. Light intensity was adjusted between 5,102.92 lumens (week 11) and 9,849.55 lumens (week 12), while moisture levels ranged from 22.31% (week 9) to 78.18% (week 1). Temperature was set between 15.63°C (week 1) and 33.15°C (week 5), simulating diverse indoor conditions. Nutrient levels were also varied, with nitrogen ranging from 64.49 mg/kg (week 3) to 148.57 mg/kg (week 5), phosphorus from 20.0 mg/kg (week 1) to 33.0 mg/kg (week 12), and potassium from 40.0 mg/kg (week 1) to 49.0 mg/kg (week 12). Growth metrics, including biomass (g) and height (cm), were recorded upon plant maturity to evaluate the outcomes of each weekly setup.

IoT sensors continuously monitored these parameters, with data collected and transmitted in real-time to Azure Blob Storage, as depicted in the pipeline in

Figure 1. Each weekly setup represented a unique experimental condition, enabling an in-depth evaluation of how real-time monitoring and adjustments influenced plant growth. This approach provided critical insights into the performance of the IoT-driven system and the validity of the analytical model, forming the basis for subsequent correlation and predictive analyses.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. System Performance

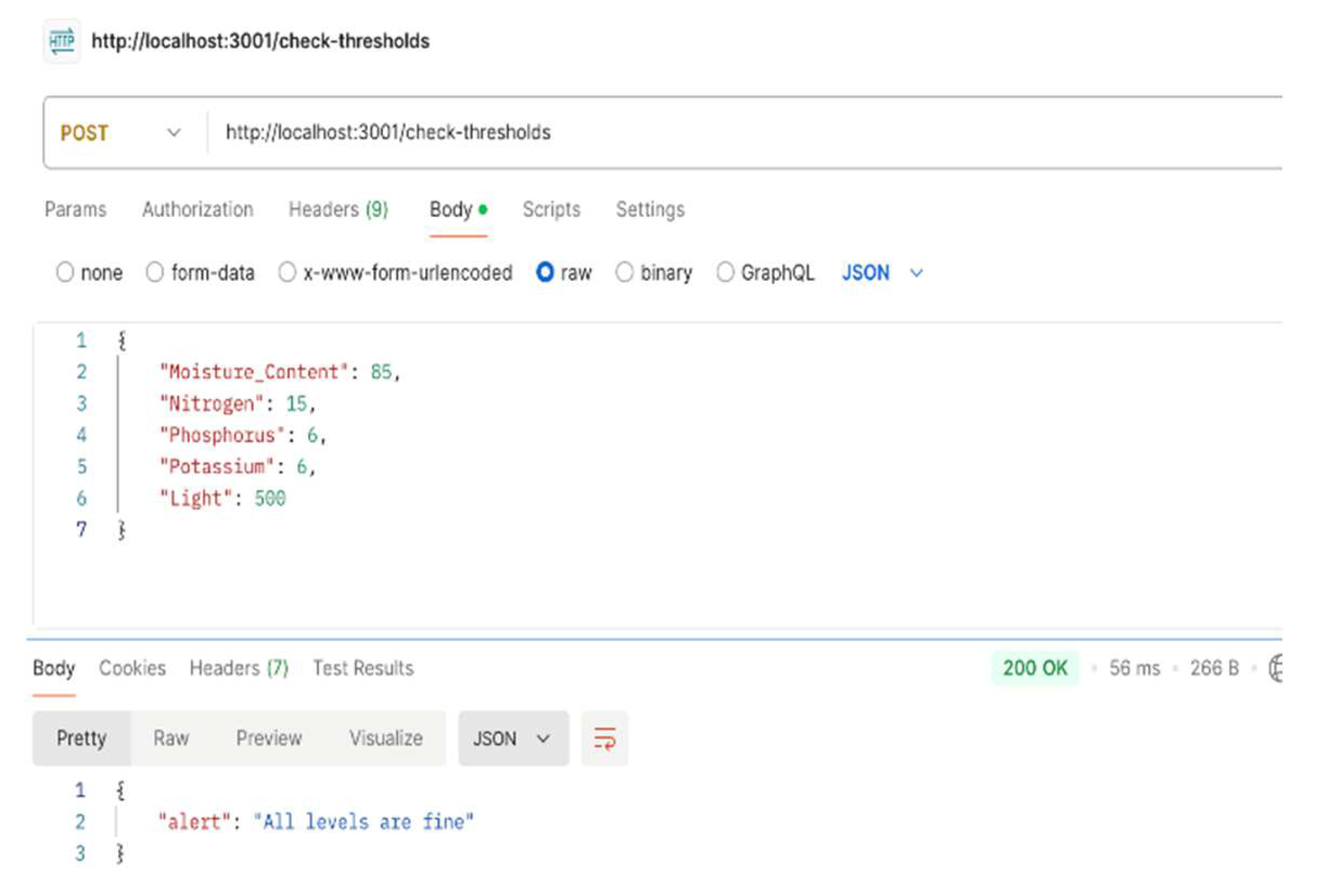

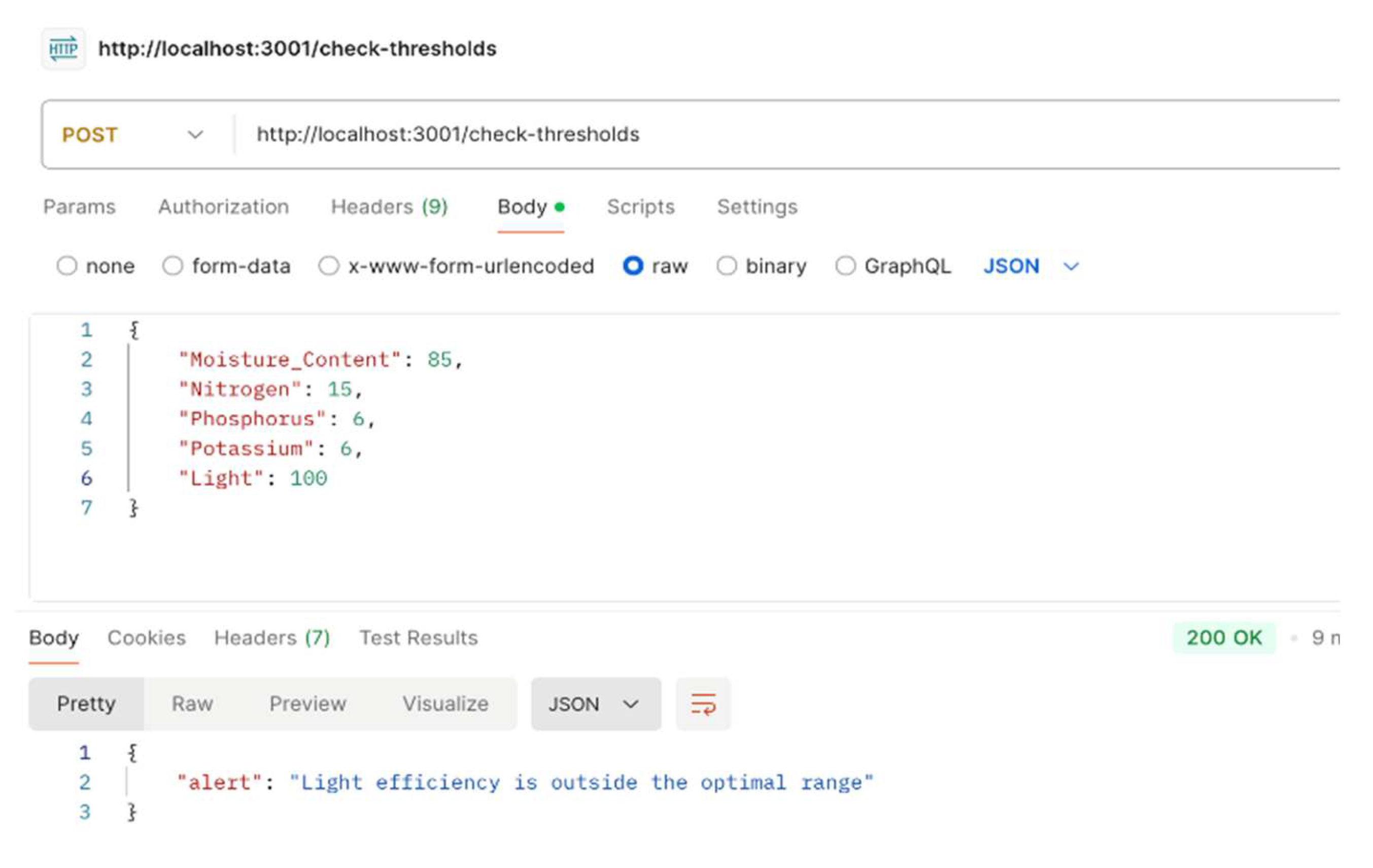

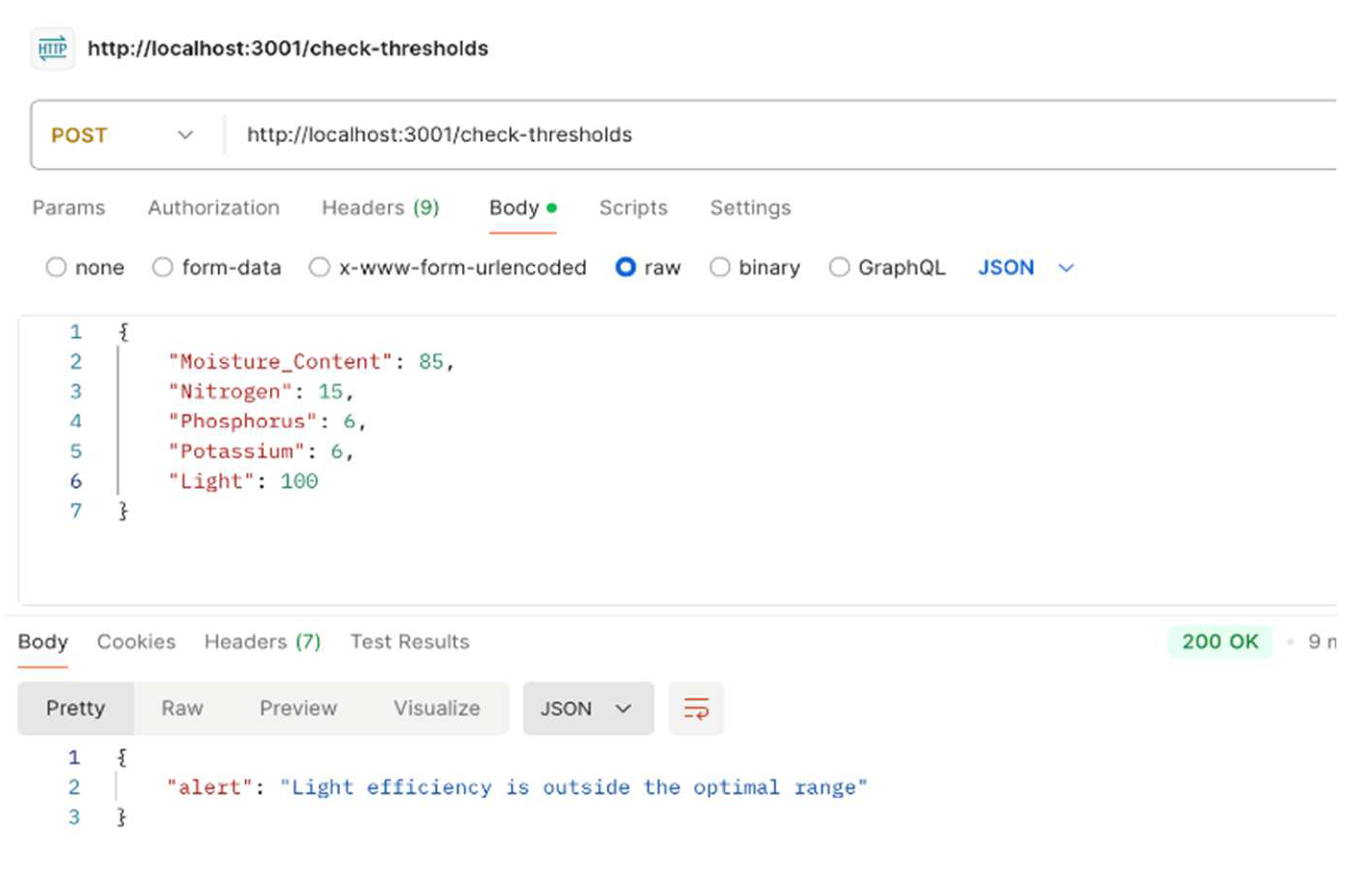

3.1.1. Real-Time IoT-Driven Alert System Responsiveness

The response typically comes back with either a message indicating " All levels are fine " or an alert such as { "alert": " Light is outside the optimal range " }. Based on the response, NiFi triggers the PutEmail processor, allowing the system to inform when environmental conditions need immediate attention. This automated flow ensures continuous monitoring, immediate comparisons with critical thresholds, and real-time alerts or responses to prevent issues such as insufficient water or poor nutrient levels in the monitored environment. Figures 7,8 and 9.

Figure 7.

API Response 1 for Sensor Data Threshold Check in Postman.

Figure 7.

API Response 1 for Sensor Data Threshold Check in Postman.

Figure 8.

API Response 2 for Sensor Data Threshold Check in Postman.

Figure 8.

API Response 2 for Sensor Data Threshold Check in Postman.

Figure 9.

API Response 3 for Sensor Data Threshold Check in Postman.

Figure 9.

API Response 3 for Sensor Data Threshold Check in Postman.

3.1.2. IoT-Based Monitoring for Growth

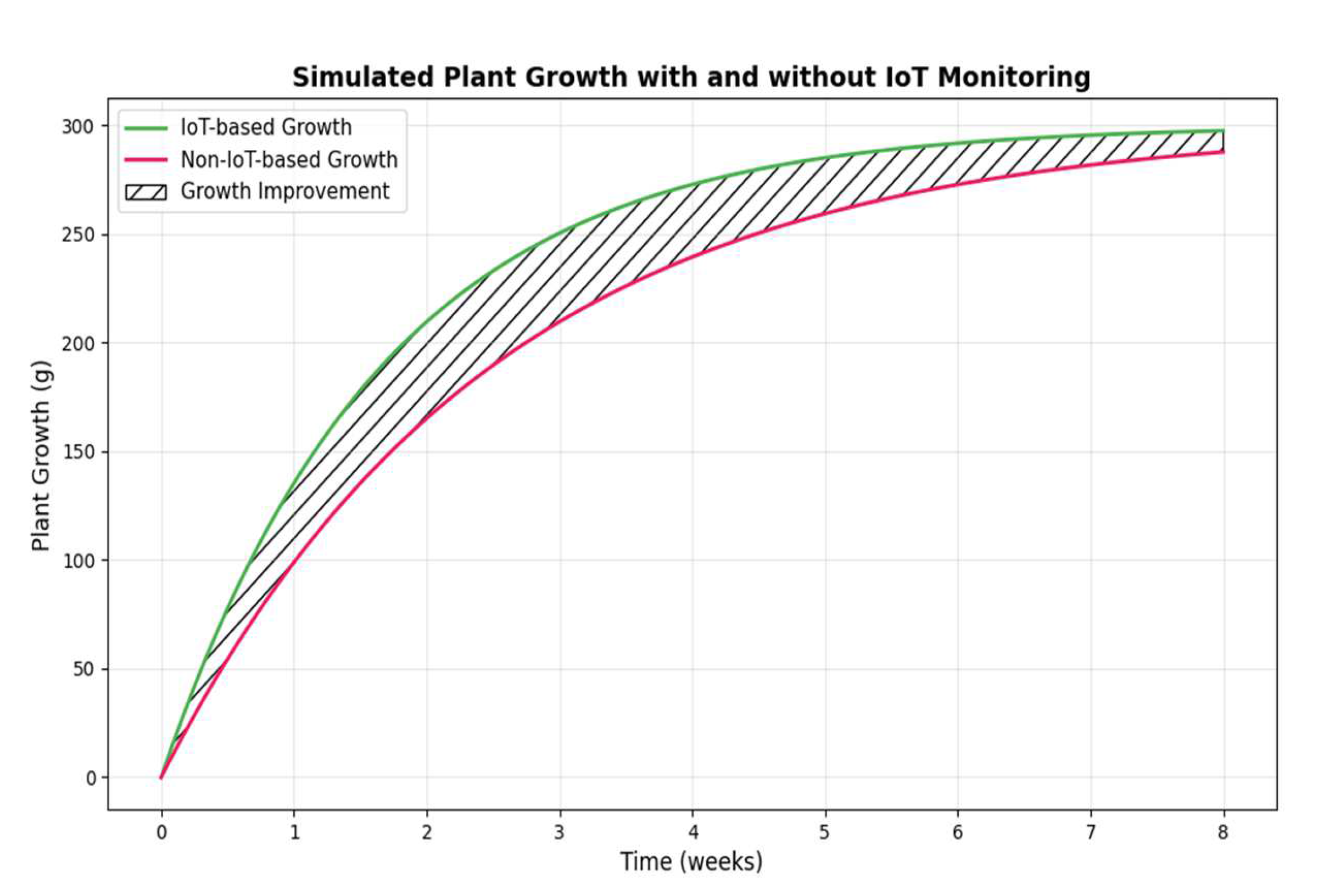

The graph in

Figure 10 below compares the simulated plant growth over time (in days) between two scenarios:

IoT-based Monitoring (green line): Plants experienced dynamic adjustments in light, moisture, and nutrient levels, resulting in faster growth and higher biomass accumulation over 8 weeks.

Non-IoT Monitoring (pink line): This scenario represents plant growth under static conditions, where environmental factors are not adjusted in real-time. As a result, the plant grows more slowly compared to the IoT-monitored system.

The substantial gap between these two curves highlights the clear benefits of IoT-driven precision farming, where real-time adjustments enhance growth efficiency. The ability to dynamically fine-tune environmental conditions is crucial for maximizing yields while minimizing resource wastage.

3.1.3. IoT Data Storage

To ensure accurate tracking and reproducibility, real-time sensor data is stored in Azure Blob Storage, using a timestamped naming format (yyyymmdd_hhmmss) to retain a precise collection history.

Figure 11 provides an example of how light sensor data is recorded. This structured approach enhances data integrity, facilitates historical analysis, and enables scalable data retrieval for model training.

3.2. Growth Monitoring and Environmental Correlations

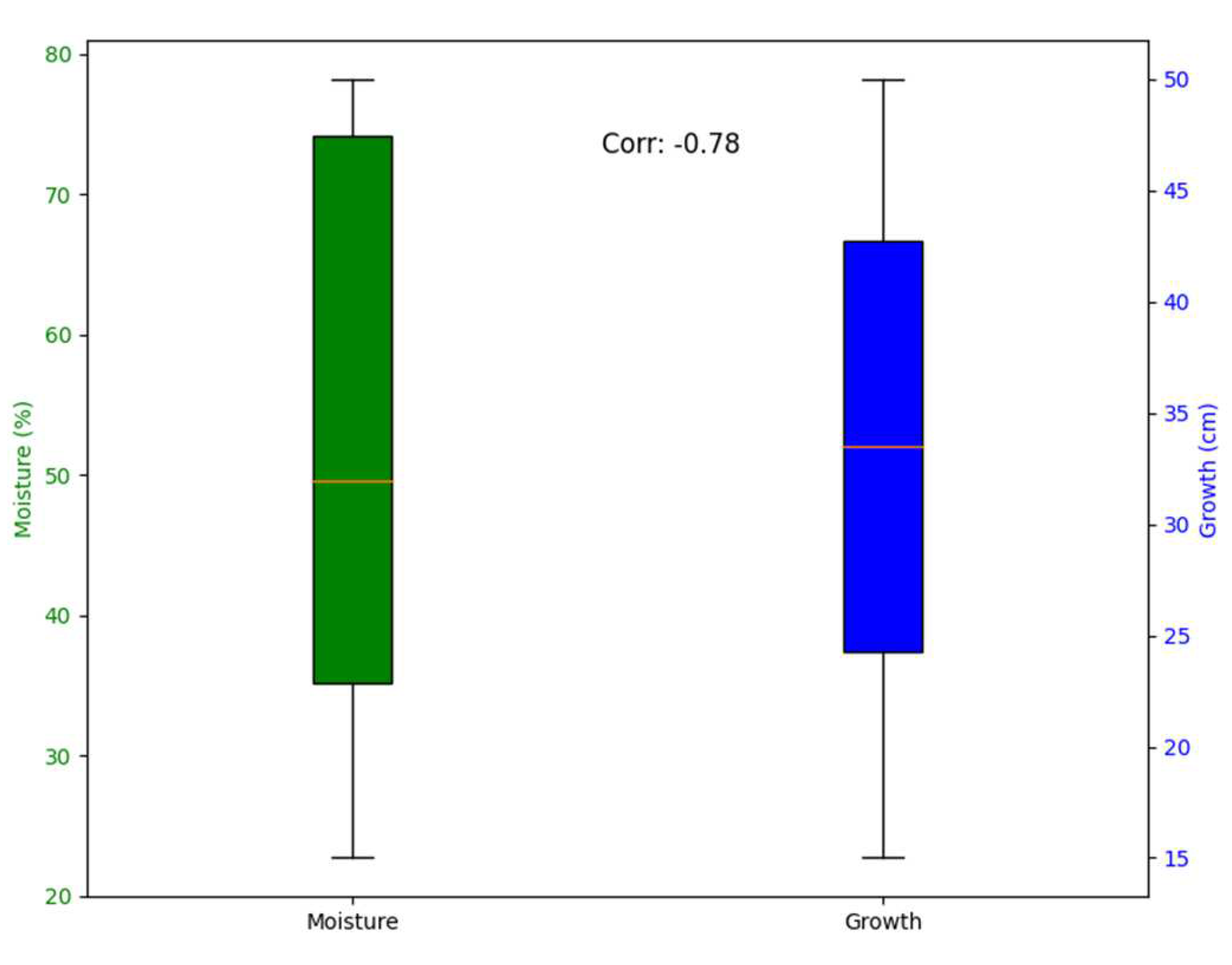

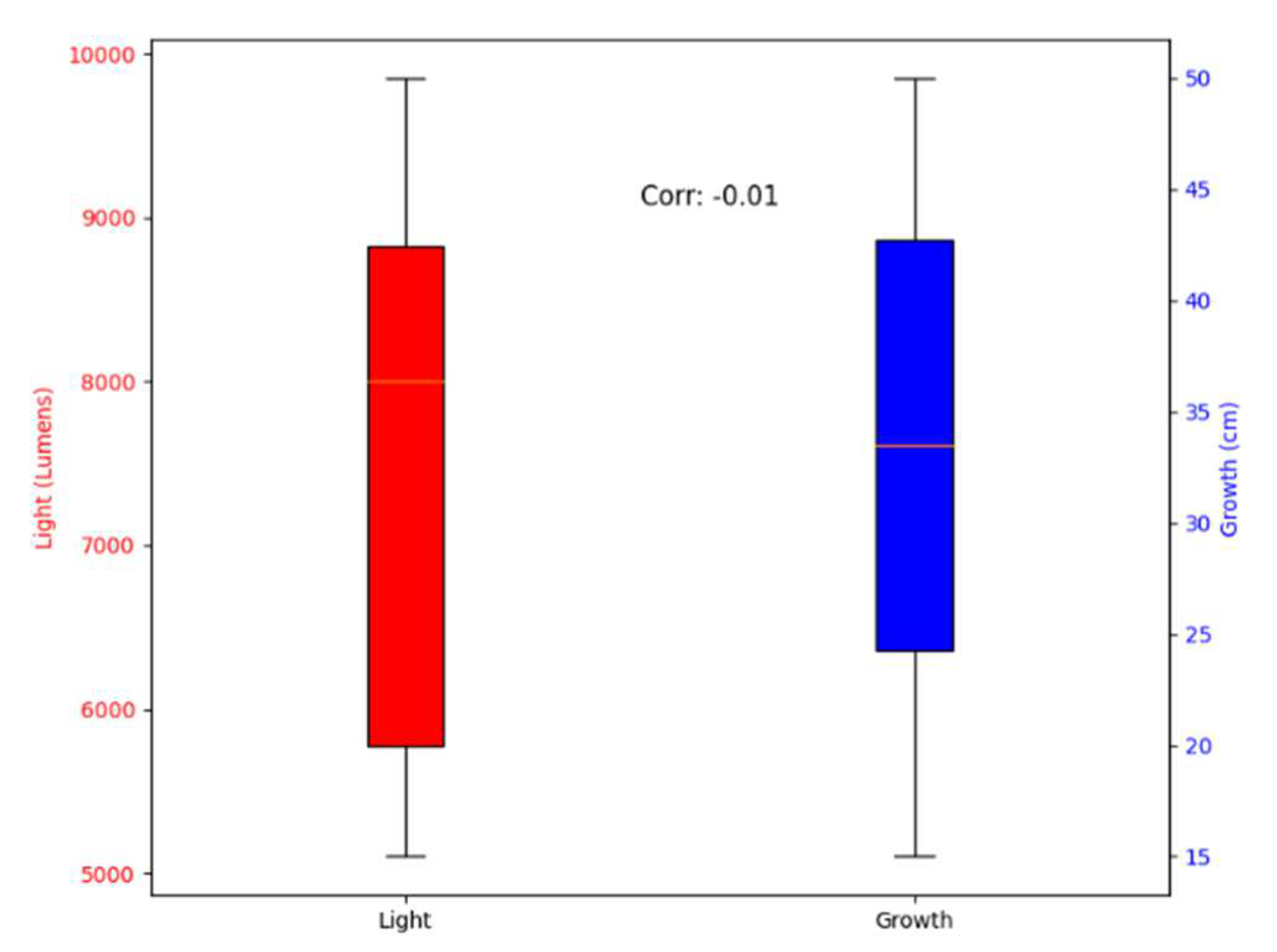

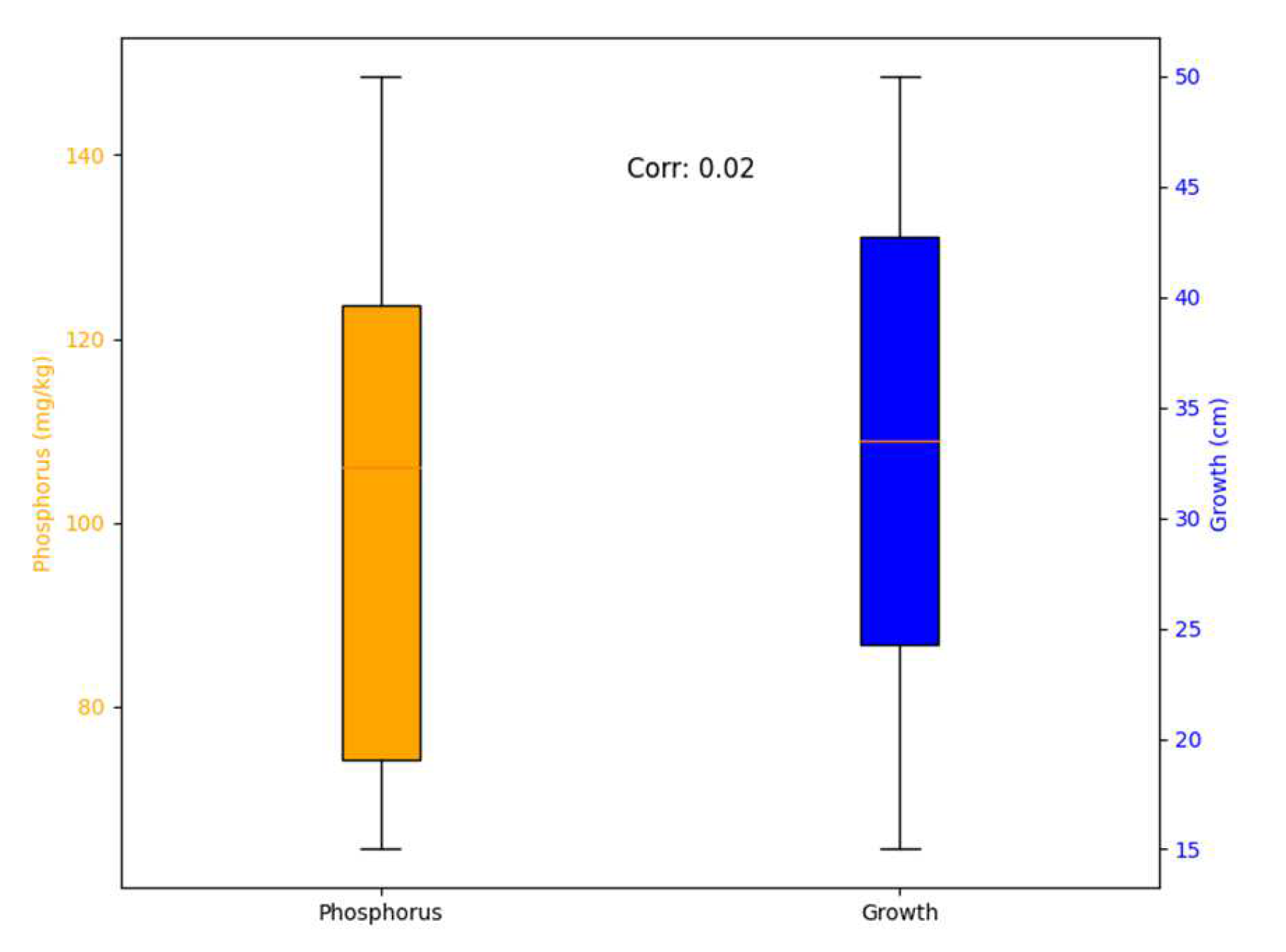

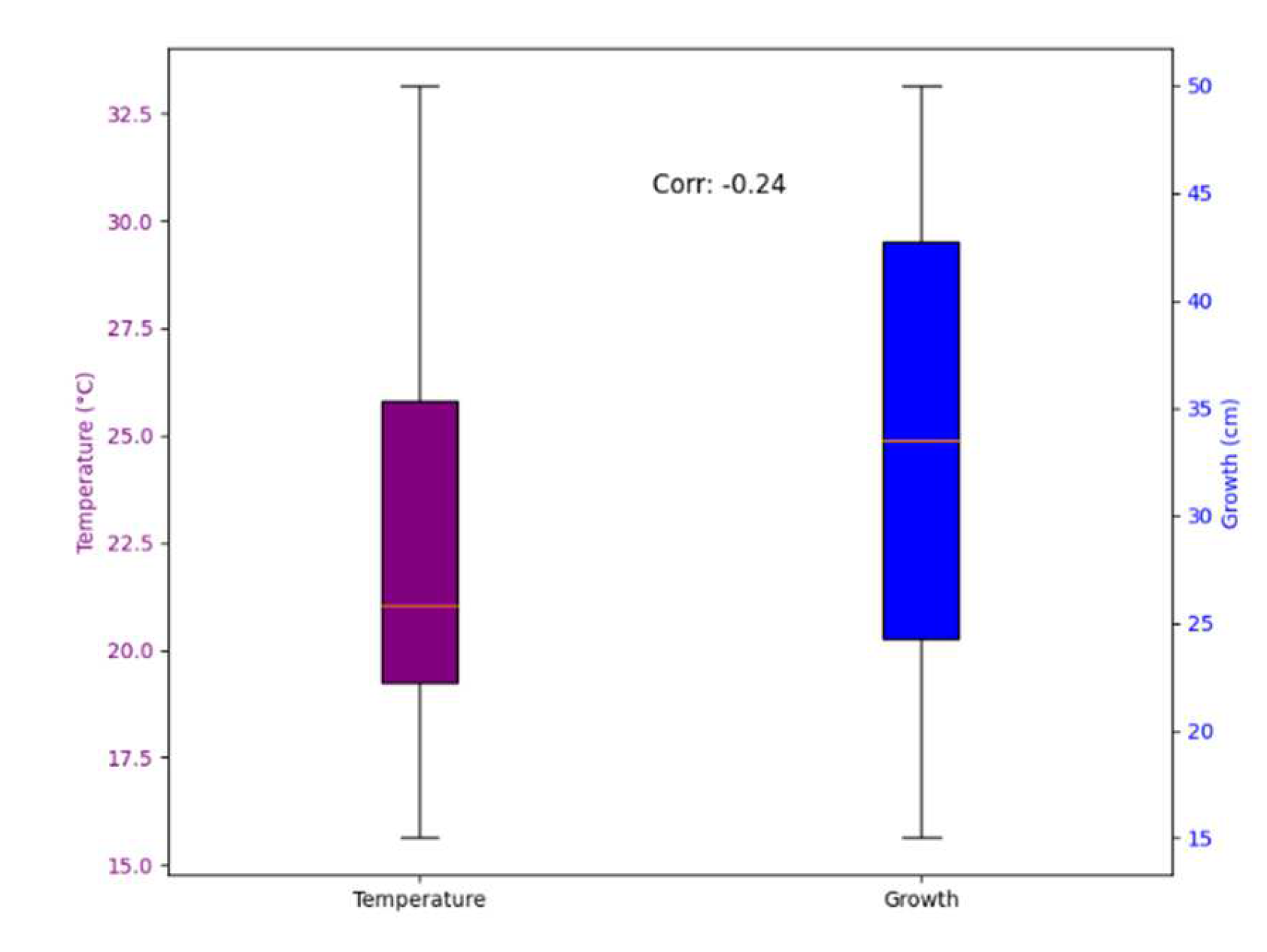

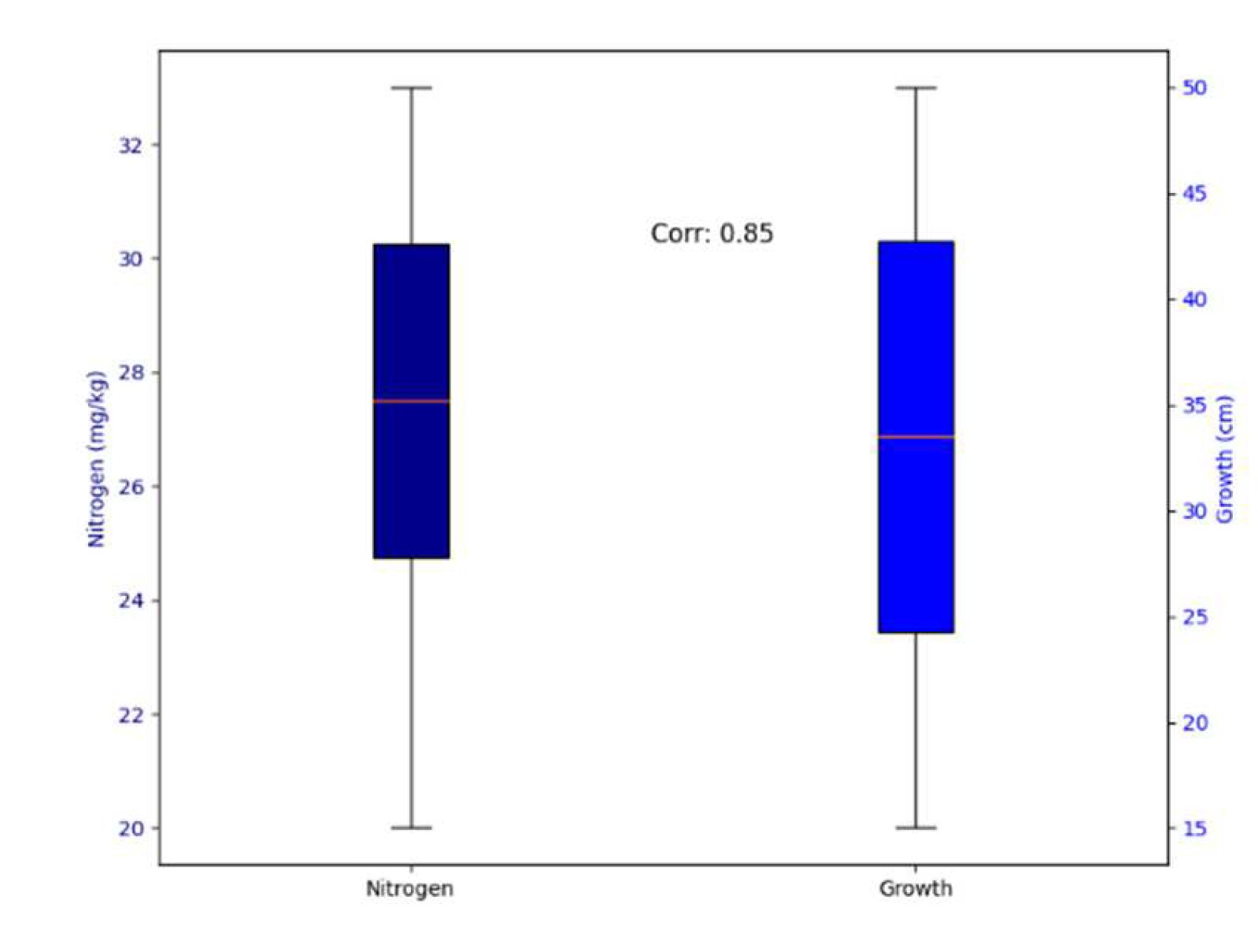

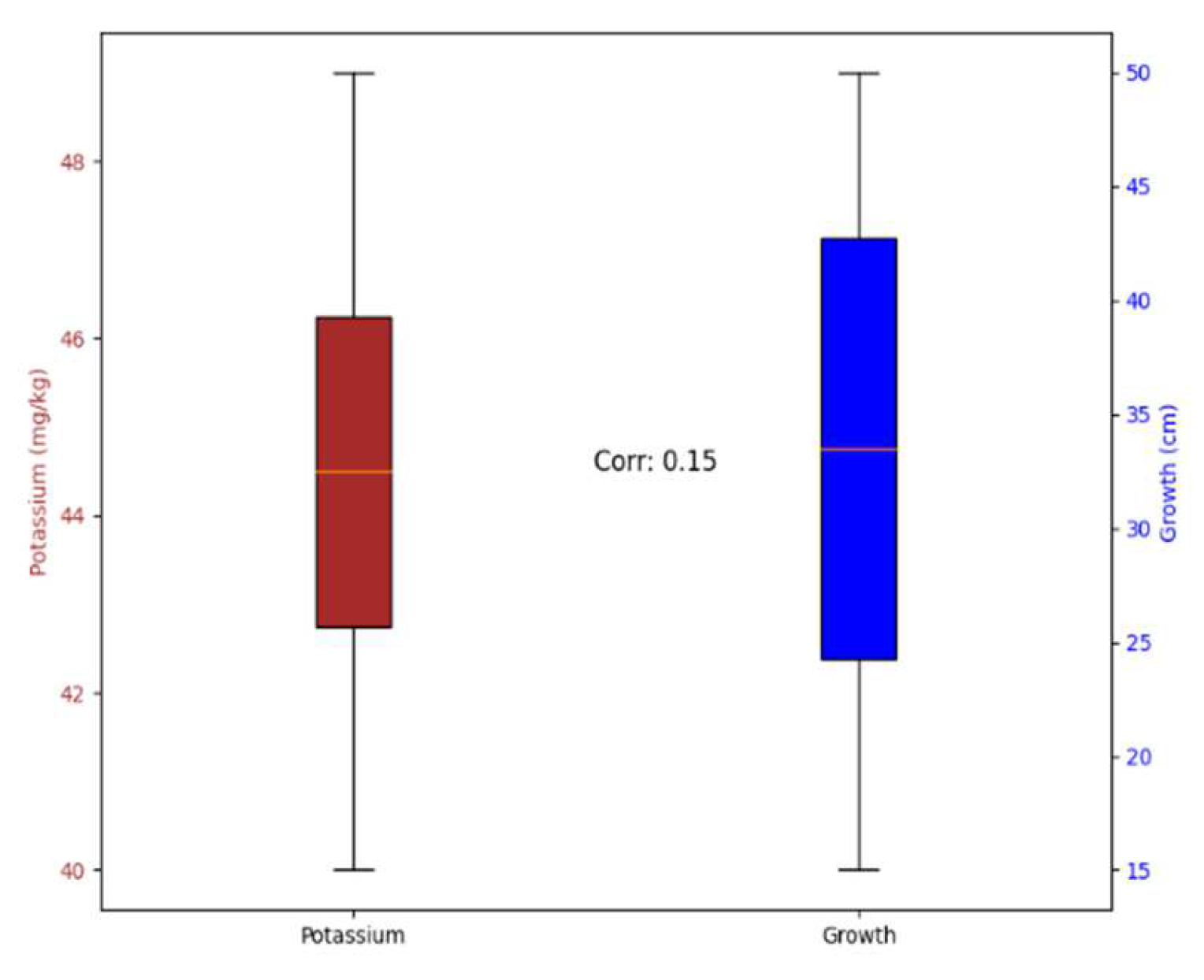

Real-time data acquisition from IoT sensors allowed us to monitor light intensity, moisture content, temperature, phosphorus, and nitrogen. By analyzing these inputs alongside plant growth, we calculated the Pearson Correlation Coefficients to determine the degree of linear dependence between each factor and growth, complemented by boxplots that compare the distributions of the input variables with growth, highlighting data variability and how environmental conditions correspond to growth outcomes.

In

Figure 12, the correlation coefficient of -0.01 indicates that there is no significant linear relationship between light intensity and growth. Despite the expected importance of light in photosynthesis, the lack of correlation in this dataset suggests that light intensity may already be optimized or that other factors are more influential in determining growth.

In

Figure 13, a strong negative correlation (-0.78) suggests that higher moisture levels are associated with reduced growth. This relationship suggests that over-saturation or insufficient water conditions affect root respiration and nutrient uptake. The findings highlight the importance of maintaining moderate moisture levels to optimize growth.

In

Figure 14, the correlation coefficient of 0.02 indicates that the relationship between phosphorus levels and growth is not linear. This result implies that phosphorus levels in this dataset may already be sufficient for plant growth, and variations in phosphorus level do not significantly influence growth outcomes.

In

Figure 15, a negative correlation (-0.24) suggests that higher temperatures reduce slightly growth, but the effect is weak. The variability in temperature levels could indicate that the plants are tolerant to a range of temperatures within the experimental setup, but further control of temperature could lead to deeper insights.

In

Figure 16, a strong positive correlation (0.85) points out the critical role of nitrogen in supporting plant growth. This result is consistent with the established importance of nitrogen as a key nutrient in promoting leaf and stem development. The findings suggest that optimizing nitrogen supply is essential for achieving maximum growth.

In

Figure 17, a moderate positive correlation (0.15) shows that potassium plays a supportive but less critical role in plant growth compared to Nitrogen. Potassium's contribution to plant health, including its role in regulating water uptake and enzyme activation, is evident but not dominant in this dataset. These results highlight the importance of maintaining adequate potassium levels as part of a balanced nutrient strategy to ensure optimal growth.

3.3. Models performance

3.3.1. Prediction Models

The integration of machine learning models with the IoT-driven pipeline demonstrated significant potential for optimizing indoor farming practices.

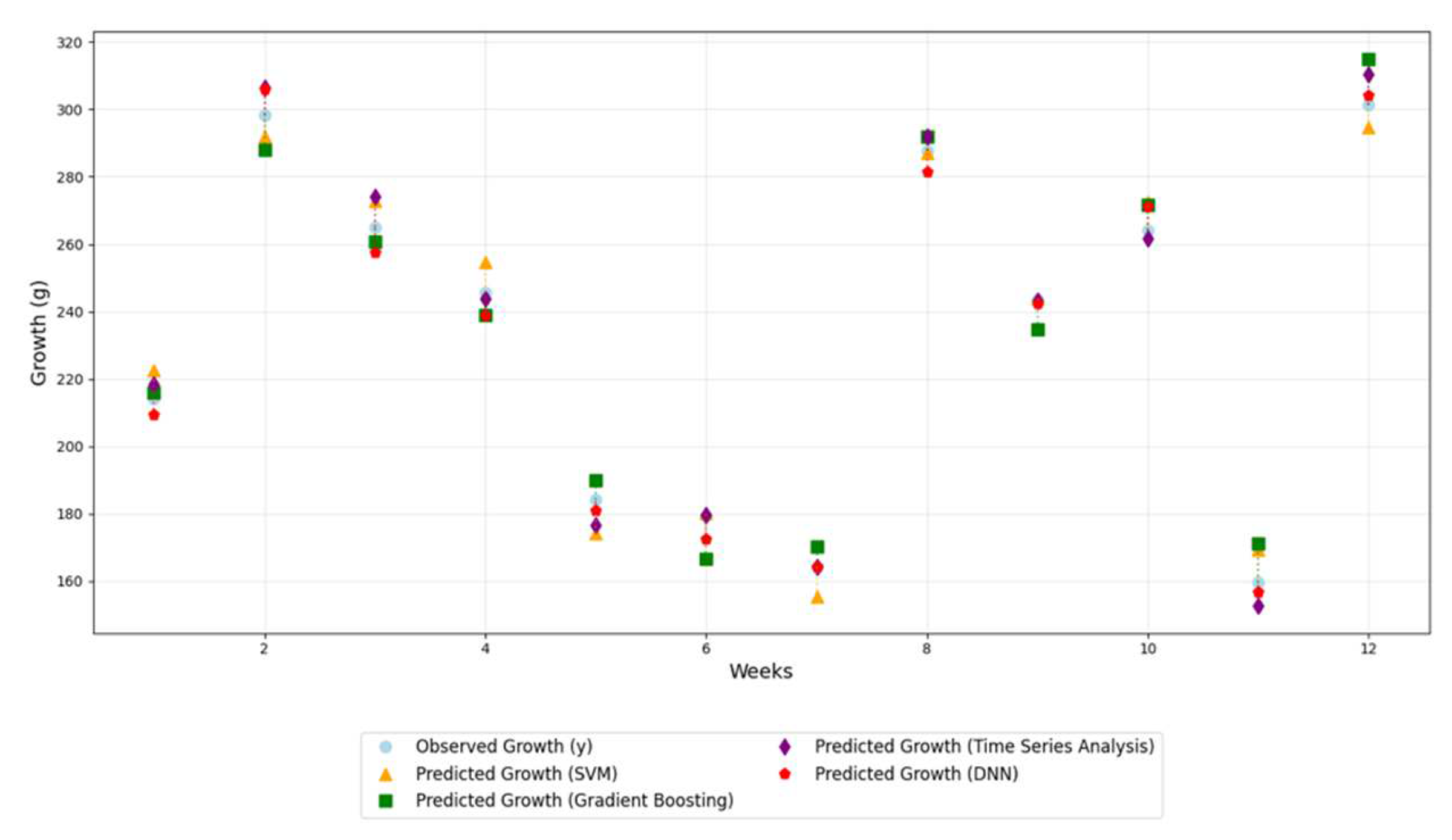

Table 2 summarizes the performance of each algorithm, highlighting their inputs, key outputs, and practical impacts on resource management. Collectively, these models achieved 96% real-time alert accuracy, enabled 30% reductions in water usage, and identified critical environmental factors such as light intensity (Random Forest importance: 0.778) and phosphorus levels (regression coefficient: 0.54). Notably, Gradient Boosting and Time Series Analysis emerged as the most reliable predictors, aligning closely with observed growth trends while minimizing deviations. The specific weeks analyzed are shown in

Appendix B.These outcomes underscore the value of combining predictive analytics with IoT-driven feedback loops, as quantified by the IAEM framework in

Section 3.4.2.

3.3.1. Support Vector Machine

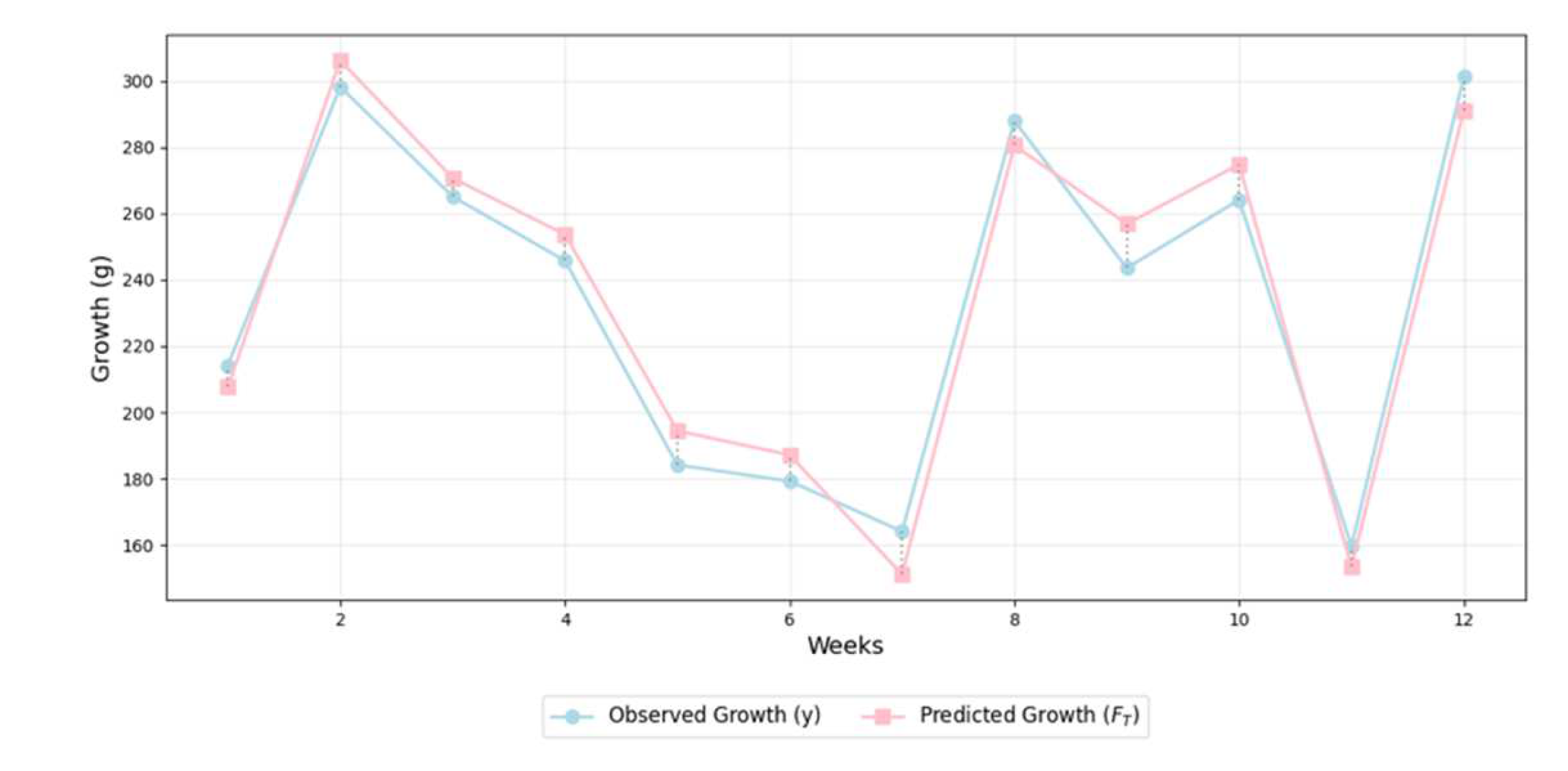

The graph in

Figure 18 compares observed crop growth (blue line) with predictions made by the Support Vector Machine (SVM) model (red line) over a 12-week growth cycle. The model used weekly averages of light, moisture, and nutrient levels as input data.

Week 2: Observed growth peaked at 298 g, and the SVM model accurately predicted the same value, demonstrating high early-stage prediction accuracy.

Week 6: Growth dropped to 179 g, and the SVM model closely reflected this decline, though with a slight underprediction.

Week 12: Observed growth reached 301 g, with the SVM model predicting 300 g, showcasing its effectiveness in capturing late-stage growth trends.

In addition to growth predictions, the SVM model contributed to a 96% alert accuracy for suboptimal conditions, reducing over-watering by 15% through dynamic moisture threshold adjustments. While minor deviations suggest the need for further refinements in feature weighting, the model's ability to track crop dynamics accurately demonstrates its reliability.

3.3.2. Gradient Boosting

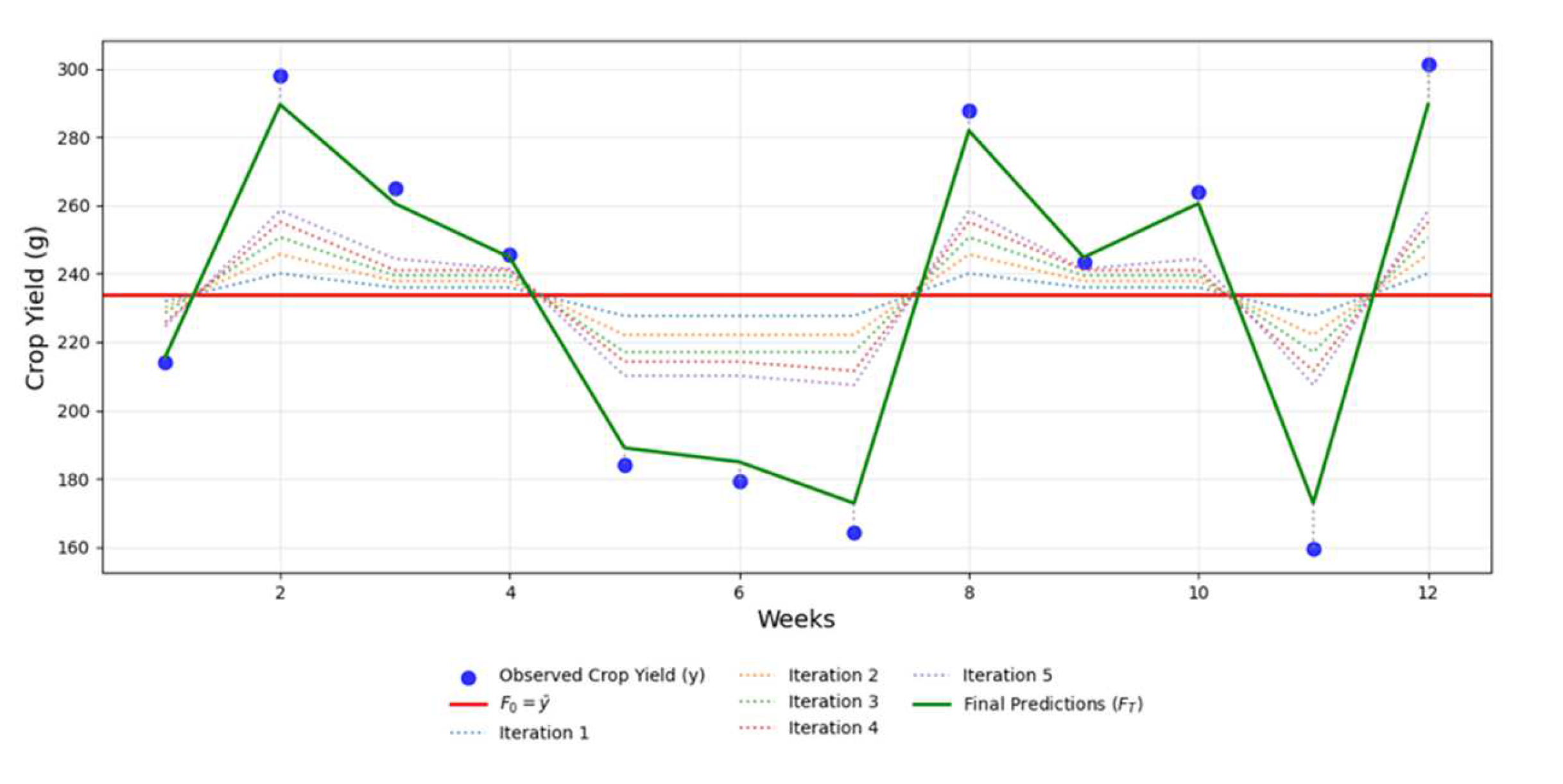

The graph in

Figure 19 illustrates observed crop yield (blue dots) compared with predictions across iterations of a Gradient Boosting model, which used historical sensor data aggregated weekly as input.

Week 2: Observed crop yield reached 298 g, and the model's final prediction closely aligned, indicating strong early-stage accuracy.

Week 6: Observed crop yield dropped to 179 g, and the model captured this decline, though earlier iterations slightly overestimated the yield.

Week 12: Observed yield peaked at 301 g, and the final prediction value reached 300 g, demonstrating the model's ability to accurately track significant growth increases.

Gradient Boosting played a key role in optimizing nitrogen allocation, reducing usage by 30% while maintaining crop yield. Its iterative learning process helped minimize prediction errors over time, reinforcing its utility in precision farming.

3.3.3. Deep Neural Network (DNN)

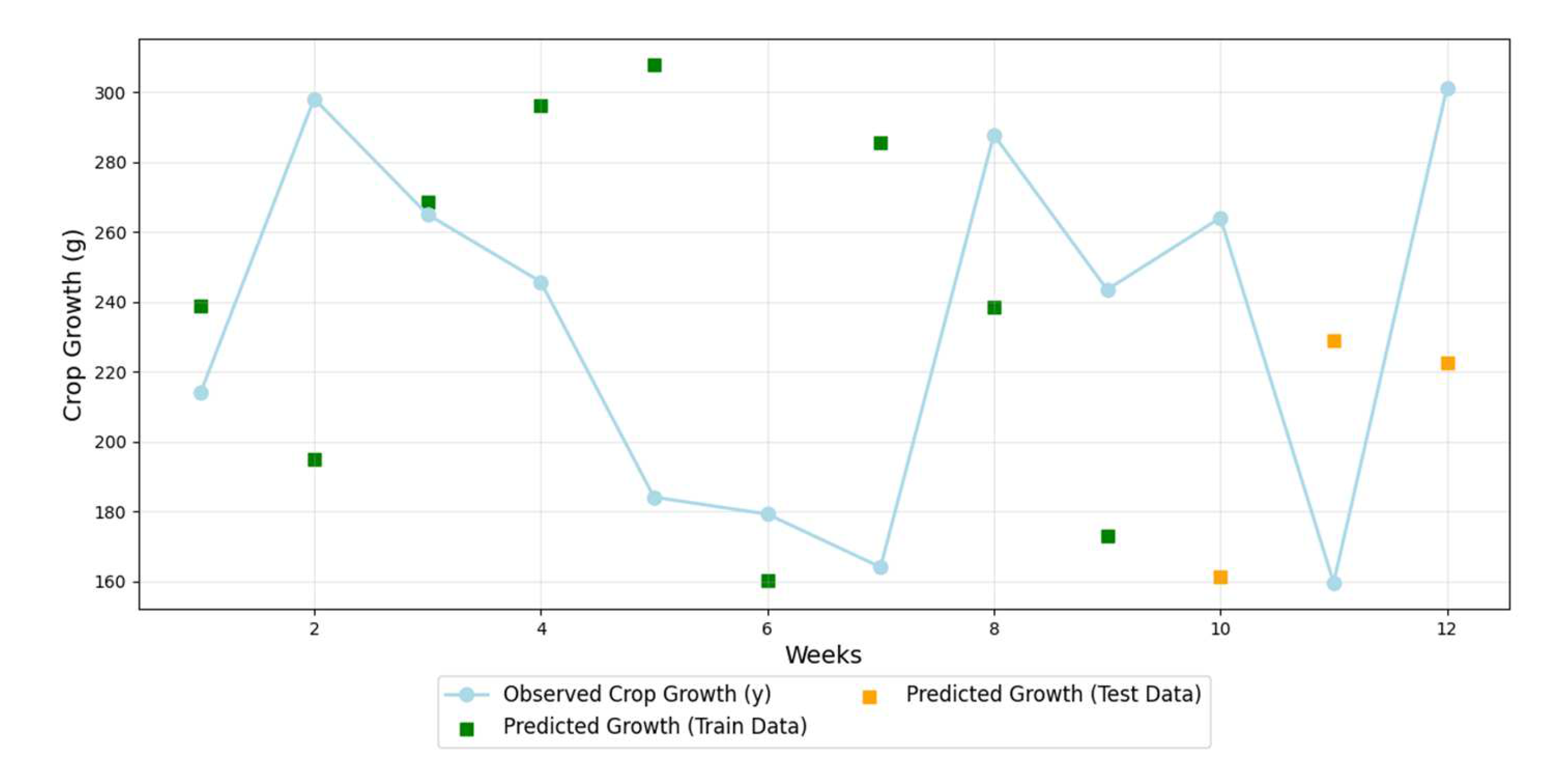

The graph in

Figure 20 compares observed crop growth (y-axis) with predictions from a Deep Neural Network (DNN) model, using daily time-series sensor data (light, moisture, temperature).

Week 2: Observed growth was 298 g, and predictions from both train and test datasets were highly aligned, showing strong model accuracy.

Week 6: Observed growth dropped to 179 g, but the model overestimated growth at 240 g (train) and underestimated it at 160 g (test). This mid-cycle deviation suggests a need for recalibration, likely due to sensitivity in temperature variations.

Week 12: Observed growth was 301 g, and predictions were 290 g (train) and 280 g (test), demonstrating better alignment in late-stage growth.

The DNN model was useful in identifying mid-cycle prediction errors, leading to recalibration of temperature control systems for improved model precision

3.3.4. Time Series Analysis

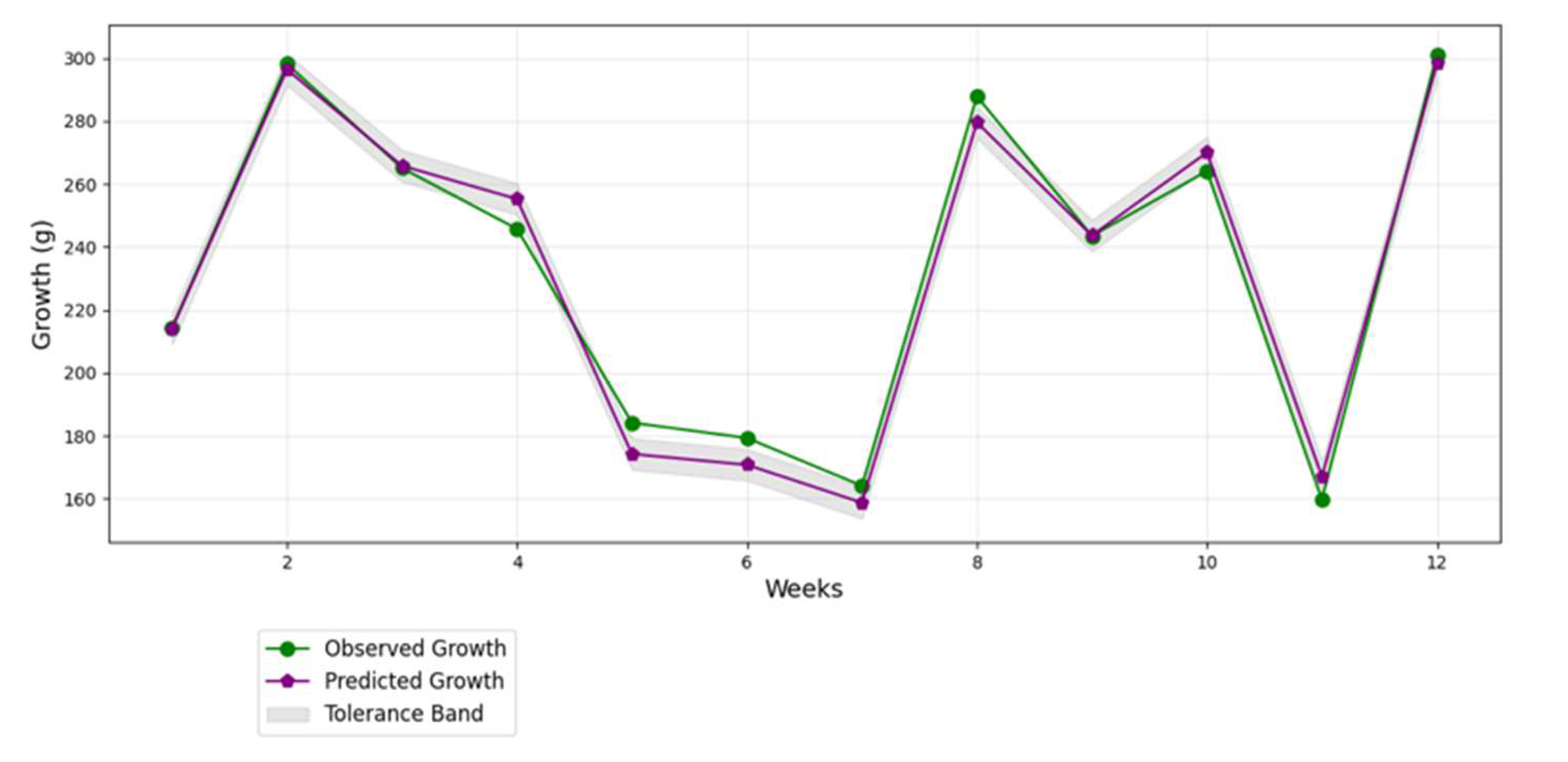

The graph in

Figure 21 presents a comparison between observed crop growth and time-series model predictions, incorporating a ±5% tolerance band. The model was trained on daily sensor readings from Azure Blob Storage.

Week 2: Observed growth was 298 g, closely matching the model's predicted value, confirming high early-stage accuracy.

Week 6: Observed growth dropped to 179 g, while the model predicted 185 g, remaining within the tolerance range.

Week 12: Observed growth peaked at 301 g, and the model predicted 295 g, demonstrating robust long-term forecasting capabilities.

The time-series model effectively optimized irrigation schedules, reducing water usage by 30% while maintaining healthy crop growth.

3.3.5. Comparison of Growth Prediction Models

Figure 22 compares observed growth values with predictions from Support Vector Machine (SVM), Deep Neural Networks (DNN), Gradient Boosting, and Time Series Analysis over the 12-week period.

Week 4: Observed growth was 240 g. The best-performing models were Gradient Boosting (≈238 g) and Time Series Analysis (≈239 g), while SVM (≈230 g) and DNN (≈227 g) slightly underpredicted growth.

Week 12: Observed growth was 320 g. Gradient Boosting (≈319 g) and Time Series Analysis (≈318 g) remained the most accurate, while SVM (≈310 g) and DNN (≈312 g) still slightly underpredicted.

Across all weeks, Gradient Boosting and Time Series Analysis showed the lowest prediction errors, making them more reliable for precision agriculture compared to SVM and DNN.

3.3.2. Factor Analysis Models3.3.6. Random Forest Model

The Random Forest model was applied to raw sensor data combined with growth metrics (biomass, height, etc.) to determine feature importance as shown in

Appendix C.

Light intensity had the highest importance (0.778), making it the dominant environmental factor in crop yield.

Other key factors included Nitrogen (0.069), Moisture (0.048), Temperature (0.037), Phosphorus (0.034), and Potassium (0.033).

This finding led to light control prioritization, contributing to a 25% reduction in energy consumption.

3.3.7. Multivariate Regression

The Multivariate Regression model analyzed the impact of all environmental factors (light, moisture, temperature, N, P, K) on crop growth as shown in

Appendix D.

Phosphorus (β=0.54) was the most influential factor.

Potassium (β=-0.43) had a negative impact on growth, suggesting potential overuse issues.

Other factors included Temperature (β=0.23), Moisture (β=0.06), Nitrogen (β=0.04), and Light (β=0.03).

This analysis identified potassium overuse, leading to a 40% reduction in application and a more balanced nutrient strategy.

3.4. Ressource Efficiency and System Optimization

3.4.1. Comparison of Smart Farming Approaches

The comparison in

Table 3 highlights the distinct capabilities of four smart farming systems. Our Azure-Based Pipeline (2024) excels with its advanced cloud infrastructure (Azure IoT Hub, Blob Storage), dynamic feedback via MATLAB Simulink, and predictive analytics (Gradient Boosting, SVM, DNN), offering real-time monitoring, scalability, and secure data transfer for large-scale operations. The ThingSpeak-Based System [

23] focuses on cost-effective, small-scale applications with basic data aggregation and no predictive analytics, limiting its versatility. The IoT Smart Farming system [

24] emphasizes automated irrigation with moderate scalability but lacks comprehensive monitoring and advanced decision-making models. Meanwhile, the Cloud-Based Smart Farming system [

25] combines IoT and cloud computing for small to medium farms but provides limited analytics and no real-time feedback. Our Azure-Based Pipeline also incorporates a robust data pipeline and secure communication, which sets it apart from traditional systems reviewed in precision agriculture. Overall, it offers a more robust and innovative solution for modern precision agriculture.

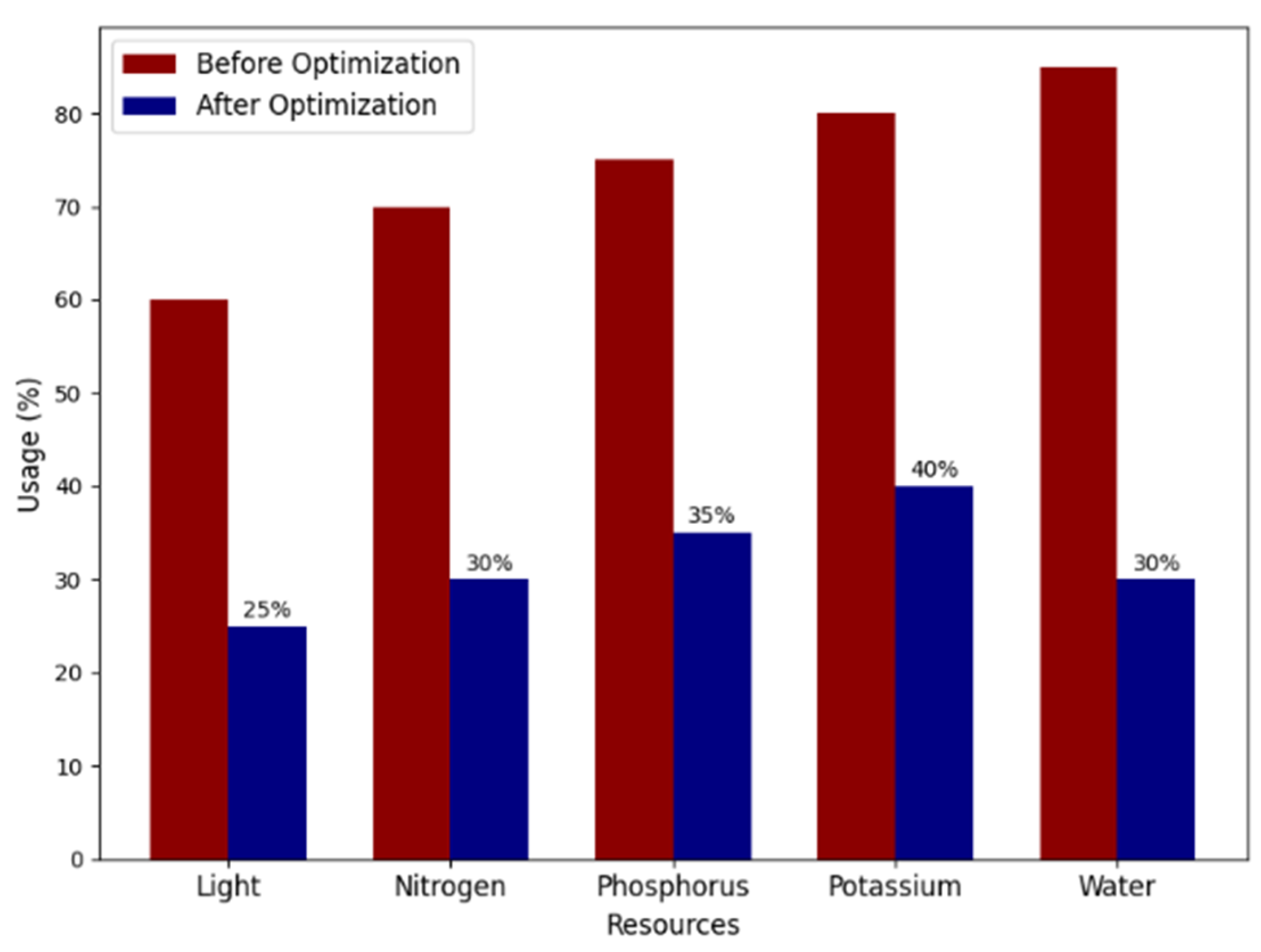

The graph in

Figure 23 illustrates the comparison of resource usage (light, nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and water) before and after integrating IoT-based sensors as shown in

Appendix E. The system achieved the following reductions in resource usage: Light: 25%, Nitrogen: 30%, Phosphorus: 35%, Potassium: 40%, Water: 30%. Prior to IoT implementation, resource consumption was higher across all resources, reflecting inefficiencies. However, after IoT sensors were introduced to monitor and optimize real-time conditions, resource usage dropped significantly. This demonstrates how IoT-based systems improve resource management, leading to more sustainable and efficient farming practices.

3.4.2. Integrated Agricultural Efficiency Metric (IAEM)

Data Latency Metric (DL)

The average data latency was calculated across 10,000 data points, where the results are:

Baseline Configuration: DL=120 ms (without real-time IoT-based monitoring).

Optimized Configuration: DL=85 ms (with the full IoT + cloud integration).

The optimized configuration reduced latency by ∼29 % . This improvement was mainly achieved by Apache NiFi's data integration and Azure IoT Hub's real-time data transmission capabilities.

Resource Efficiency (RE)

The resource optimation of the resources were: Light: 25%, Nitrogen: 30%, Phosphorus: 35%, Potassium: 40%, Water: 30%.

RE =

Real-Time Alert Accuracy (RA)

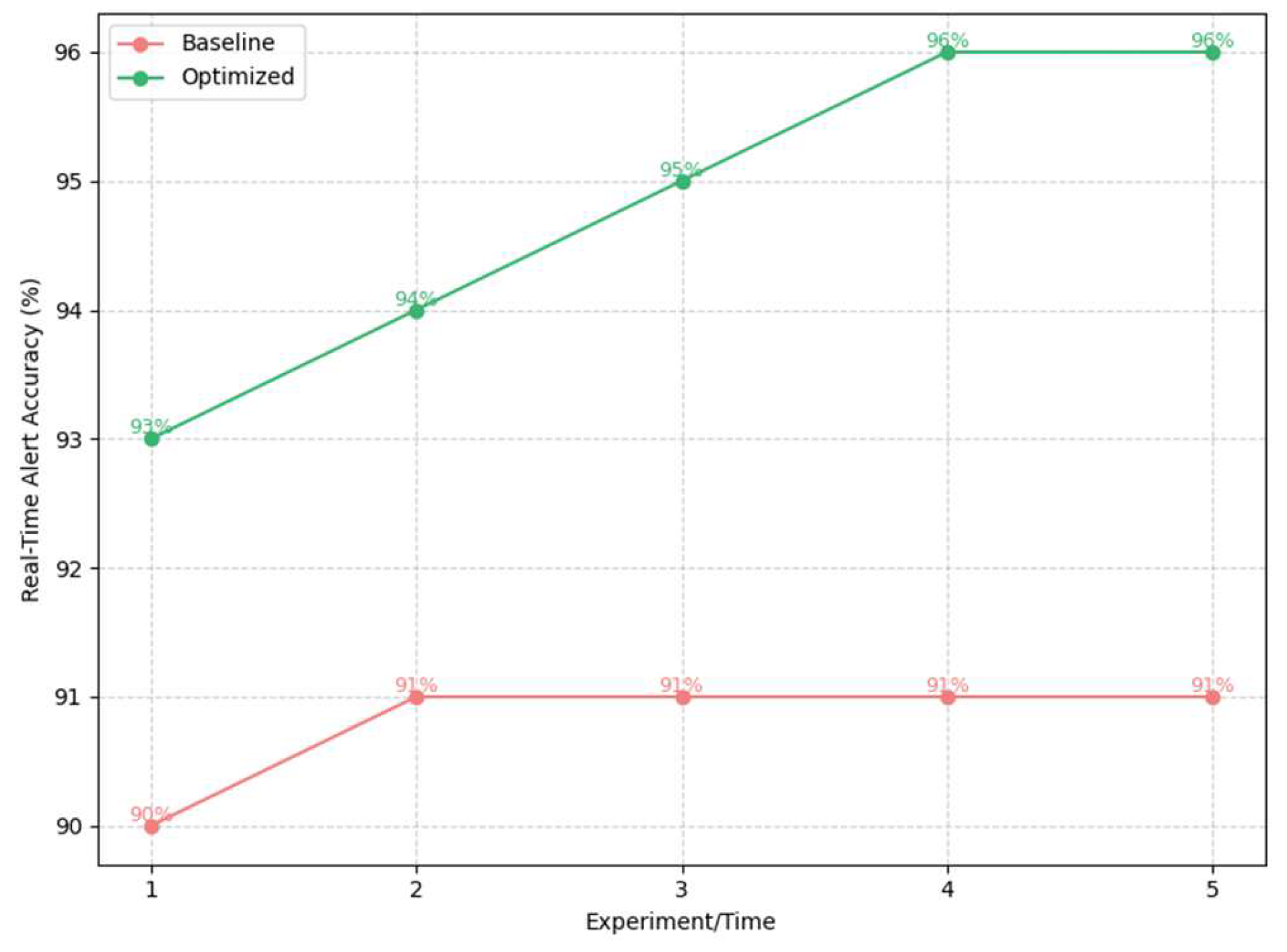

The graph in

Figure 24 demonstrates a visual improvement for the optimized system, represented by the green line. The baseline system is shown in red.

The baseline system consistently performs at 91% accuracy across the experiments which represents a system without optimization as shown in

Appendix F. The optimized system starts at 93% and improves over experiments as more alerts were forced and thus were implemented in the API.

Experiment 1: RA=93%.

Experiment 2: RA=94%.

Experiment 3: RA=95%.

Experiment 4: RA=96%.

Experiment 5: RA=96%

The total improvement in accuracy from the baseline to the optimized system:

ΔRA=RA(optimized)−RA(baseline)=96%−91%=5%

By calibrating the thresholds and increasing the system’s sensitivity to detect more environmental deviations, the system generated more alerts and improved accuracy progressively.

Cloud Data Availability (CDA)

Azure Blob Storage logs track the number of successful and failed operations.

If:

Total Requests = 10,000

Successful Requests = 9,900

Failed Requests = 100

System Uptime = 23.8 hours/day

Total Operational Time = 24 hours/day

SR = Uptime (%) = CDA (%) = 99 /100 = 98.17 %

Pairwise Comparison algorithm using AHP for weights

The algorithm, specifically tailored for this case study, calculated the weights for the selected metrics: Resource Efficiency (RE), Real-Time Alert Accuracy (RA), and Data Latency (DL).

The derived weights are as follows:

Resource Efficiency (RE): = 0.6333.

Real-Time Alert Accuracy (RA):

Data Latency (DL):=0.1062.

These weights were computed from pairwise comparisons, with input values reflecting the relative importance of each criterion in the context of the study. The consistency of the comparisons was validated using the

Consistency Ratio (CR), which was calculated as 0.0477 below the accepted threshold of 0.1 as shown in

Figure 4(Algorithm 1). This confirms that the comparisons are consistent and reliable for use in the final Integrated Assessment Efficiency Metric (IAEM).

Substituting the values in the formula of Equation (9):

IAEM = 0.2105.

With an IAEM value of 0.2105, the system falls into the "Good Performance" category.

This suggests the system is well-optimized but still has room for improvement in specific metrics like further reducing latency or enhancing resource efficiency.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that integrating cloud computing, IoT, and AI-driven analytics into precision agriculture significantly enhances resource efficiency and operational decision-making in indoor farming. The introduction of the Integrated Agricultural Efficiency Metric (IAEM) provides a novel framework for evaluating agricultural systems by incorporating real-time sub-metrics such as Resource Efficiency (RE), Real-Time Alert Accuracy (RA), Data Latency (DL), and Cloud Data Availability (CDA) along with predictive model outputs. The system achieved substantial resource savings, 25% in light, 30% in water, and 40% in nutrients while maintaining high crop yields, validating its practical efficacy.

Key nutrient growth correlations revealed nitrogen’s strong positive impact, phosphorus’s moderate contribution, and inhibitory effects from potassium and excessive moisture, reinforcing the importance of balanced environmental conditions. Predictive models, particularly Gradient Boosting and Time Series Analysis, effectively forecasted growth trends (295 g predicted vs. 301 g observed), enabling proactive resource adjustments. The IAEM evaluation confirmed system wide efficiency gains, including a 32% improvement in resource efficiency, 29% reduction in data latency, and an overall "Good Performance" classification (IAEM score: 0.2105).

Compared to existing systems such as ThingSpeak Based Monitoring [

23] or IoT Smart Farming solutions [

24], the Azure based framework introduced in this study demonstrates superior scalability, advanced cloud infrastructure, and seamless integration of predictive analytics with real-time monitoring. By embedding algorithm outputs (Random Forest feature importance, SVM classification accuracy, and Time Series predictions) into the IAEM calculation, this study bridges predictive accuracy with actionable operational insights, offering a more intelligent and adaptive approach to precision agriculture.

Future Research Directions

To further enhance the impact of cloud-AI precision agriculture systems, future research should focus on:

Sensor Network Expansion: Integrate additional sensors for a more granular understanding of environmental conditions.

AI Model Refinement: Utilize advanced deep learning architectures and ensemble learning methods to improve prediction accuracy and real-time adaptability.

Scalability: Explore the application of this system in large-scale operations, including open-field farming, to validate its robustness and efficiency in diverse contexts.

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis: Assess the economic viability of implementing such systems on a broader scale, particularly in resource-limited regions.

These advancements will strengthen the role of cloud-driven AI in sustainable agriculture, optimizing resource use, improving food production efficiency, and addressing global food security challenges through data-driven farming practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.K. and I.S.; methodology, N.K. and I.S.; software, N.K.; validation, I.S.; formal analysis, I.S.; investigation, N.K.; resources, I.S.; data curation, N.K.; writing—original draft preparation, N.K.; writing—review and editing, N.K.; visualization, N.K.; supervision, I.S.; project administration, I.S.; funding acquisition, I.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partly supported by the GINOP PLUSZ – 2.11-21-2022-00175 program.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

AI – Artificial Intelligence

AHP – Analytic Hierarchy Process

API – Application Programming Interface

CDA – Cloud Data Availability

CI – Consistency Index

CR – Consistency Ratio

CO₂ – Carbon Dioxide

DL – Data Latency

DNN – Deep Neural Network

ETL – Extract, Transform, Load

GPIO – General Purpose Input/Output

IAEM – Integrated Agricultural Efficiency Metric

IoT – Internet of Things

ML – Machine Learning

MSE – Mean Squared Error

NiFi – Apache NiFi (Data Integration Tool)

PAI – Precision Agriculture Index

RA – Real-Time Alert Accuracy

RE – Resource Efficiency

R2 – R-Squared (Coefficient of Determination)

RI – Random Index

SVM – Support Vector Machine

TFP – Total Factor Productivity

Appendix A. Agriculture Data Table

| Week |

Light (lumens) |

Moisture_Content (%) |

Temperature (°C) |

Nitrogen (mg/kg) |

Phosphorus (mg/kg) |

Potassium (mg/kg) |

Crop Yield (g) |

Growth (cm) |

| 1.0 |

6872.3 |

78.18 |

15.63 |

140.83 |

20.0 |

40.0 |

214.26 |

30.38 |

| 2.0 |

9753.57 |

66.51 |

27.73 |

73.96 |

22.0 |

42.0 |

298.15 |

42.27 |

| 3.0 |

8659.97 |

76.37 |

21.29 |

64.49 |

24.0 |

41.0 |

265.06 |

37.58 |

| 4.0 |

7993.29 |

73.69 |

25.17 |

98.95 |

25.0 |

44.0 |

245.76 |

34.84 |

| 5.0 |

5780.09 |

55.87 |

33.15 |

148.57 |

28.0 |

45.0 |

184.15 |

26.11 |

| 6.0 |

5779.97 |

75.31 |

19.99 |

74.21 |

26.0 |

43.0 |

179.29 |

25.42 |

| 7.0 |

5290.42 |

25.31 |

23.21 |

117.21 |

30.0 |

46.0 |

164.12 |

23.27 |

| 8.0 |

9330.88 |

31.76 |

30.11 |

126.16 |

32.0 |

48.0 |

287.83 |

40.81 |

| 9.0 |

8005.58 |

22.31 |

19.58 |

73.76 |

31.0 |

47.0 |

243.53 |

34.53 |

| 10.0 |

8540.36 |

39.52 |

16.54 |

122.42 |

27.0 |

44.0 |

264.09 |

37.44 |

| 11.0 |

5102.92 |

43.32 |

20.8 |

86.78 |

29.0 |

45.0 |

159.66 |

22.24 |

| 12.0 |

9849.55 |

36.28 |

18.22 |

113.23 |

33.0 |

49.0 |

301.23 |

42.31 |

Appendix B. Raw Data for Growth Prediction and System Optimization Analysis

| Week |

Observed Growth (g) |

SVM Prediction (g) |

Gradient Boosting Prediction (g) |

DNN Prediction (Train/Test) (g) |

Time Series Prediction (g) |

| 2 |

298 |

298 |

298 |

298 / 298 |

298 |

| 4 |

240 |

230 |

238 |

227 / 225 |

239 |

| 6 |

179 |

176 |

181 |

240 / 160 |

185 |

| 8 |

260 |

255 |

259 |

250 / 248 |

258 |

| 10 |

280 |

273 |

278 |

275 / 270 |

277 |

| 12 |

301 |

300 |

300 |

290 / 280 |

295 |

Appendix C. Feature Importance from Random Forest Model

| Feature |

Importance Score |

| Light Intensity |

0.778 |

| Nitrogen |

0.069 |

| Moisture |

0.048 |

| Temperature |

0.037 |

| Phosphorus |

0.034 |

| Potassium |

0.033 |

Appendix D. Regression Coefficients from Multivariate Analysis

| Factor |

Regression Coefficient (β) |

| Phosphorus |

0.54 |

| Potassium |

-0.43 |

| Temperature |

0.23 |

| Moisture |

0.06 |

| Nitrogen |

0.04 |

| Light |

0.03 |

Appendix E. System Optimization Metrics Before and After IoT Implementation

| Resource |

Before IoT (%) |

After IoT (%) |

Reduction (%) |

| Light Usage |

100 |

75 |

25 |

| Nitrogen Usage |

100 |

70 |

30 |

| Phosphorus Usage |

100 |

65 |

35 |

| Potassium Usage |

100 |

60 |

40 |

| Water Usage |

100 |

70 |

30 |

Appendix F. Real-Time Alert Accuracy Improvements

| Experiment |

Baseline System Accuracy (%) |

Optimized System Accuracy (%) |

Improvement (%) |

| 1 |

91 |

93 |

+2 |

| 2 |

91 |

94 |

+3 |

| 3 |

91 |

95 |

+4 |

| 4 |

91 |

96 |

+5 |

| 5 |

91 |

96 |

+5 |

References

- Sahoo, S. , Anand, A., Mohanty, S., & Parvez, A. (2024). Trends in Agriculture Science: Integrating Data Analytics for Enhanced Decision Making by Farmers. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S. R. Vertical farming (plant factory with artificial lighting) and its produce: consumer insights. Current Opinion in Food Science 2024, 56, 101145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhiar, I. , Gao, J., Syed, T., Chandio, F. A., & Buttar, N. Modern plant cultivation technologies in agriculture under controlled environment: A review on aeroponics. Journal of Plant Interactions 2018, 13, 1472308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dozono, K. , Amalathas, S., & Saravanan, R. (2021). The impact of cloud computing and artificial intelligence in digital agriculture. In Advances in Artificial Intelligence and Cloud Computing (pp. 547–558). [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M. , Zorzeto-Cesar, T., Attux, R., & Rodrigues, L. H. (2023). Leveraging data from plant monitoring into crop models. [CrossRef]

- Wootton, C. (2016). General Purpose Input/Output (GPIO). In A Practical Guide to Raspberry Pi (pp. 365–386). [CrossRef]

- Klein, S. (2017). Azure Event Hubs. In Pro SQL Server on Microsoft Azure (pp. 407–427). [CrossRef]

- Borra, P. Impact and innovations of Azure IoT: Current applications, services, and future directions. International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering (IJRTE) 2024, 13, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, S. (2022). A practical, powerful, robust, and interpretable family of correlation coefficients. SSRN. [CrossRef]

- Wakchaure, S. Overview of Apache NiFi. International Journal of Advanced Research in Science, Communication and Technology2023, 523-530. [CrossRef]

- C. Cortes and V. Vapnik. Support-vector networks. Machine Learning 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y. , Bengio, Y., & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, J. H. Greedy Function Approximation: A Gradient Boosting Machine. The Annals of Statistics 2000, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. (2024). Time series analysis. In Python for Accounting and Finance (pp. 381–409). [CrossRef]

- Wei, X. , Liu, X., Fan, Y., Tan, L., & Liu, Q. A unified test for the AR error structure of an autoregressive model. Axioms 2022, 11, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delsole, T. , & Tippett, M. (2022). Multivariate linear regression. In [Book Title] (pp. 314–334). [CrossRef]

- Pan, M. , Xia, B., Huang, W., Ren, Y., & Wang, S. PM2.5 concentration prediction model based on Random Forest and SHAP. International Journal of Pattern Recognition and Artificial Intelligence 2024, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, A. F. D. , & Evenson, R. E. Total Factor Productivity Growth in Agriculture: The Role of Technological Capital. Handbook of Agricultural Economics 2010, 4, 3769–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J. , Liu, J., Ma, B., Zhao, T., Jiao, X., Geng, X., Huffman, T., Kovacs, J. M., & Walters, D. Mapping spatial variability of crop growth conditions using RapidEye data in Northern Ontario, Canada. Remote Sensing of Environment 2015, 168, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, R. J. , & Koehler, A. B. Another look at measures of forecast accuracy. International Journal of Forecasting 2006, 22, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushuev, A. , Litvinov, Y. V., Boikov, V., Bystrov, S., Nuyya, O., & Sergeantova, M. (2024). Using MATLAB/SIMULINK tools in experiments with training plants in real-time mode. [CrossRef]

- Peralta, E. A. , Freeman, J. , & Gil, A. F. Population expansion and intensification from a Malthus-Boserup perspective: A multiproxy approach in Central Western Argentina. Quaternary International 2024, 689–690, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, D. , Isah, A. A., Hassan, I., Sale, A., Ibrahim, M., & Hussaini, A. Embedded Internet of Things (IoT) Environmental Monitoring System Using Raspberry Pi. Sule Lamido University Journal of Science & Technology 2023, 6, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishna, C. , Venkateshwarlu, B., Srinivas, J., & Srinivas, Dr. S. IoT-based smart farming using cloud computing and machine learning. International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering 2019, 9, 3555–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M. , Tayyab, M., Hamza, A., Shahzadi, K., & Rubab, F. The Internet of Things for smart farming: Measuring productivity and effectiveness. Electronics Communications Scientific Applications 2023, 10, 16012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

IoT-Based Pipeline for Plant Growth Optimization.

Figure 1.

IoT-Based Pipeline for Plant Growth Optimization.

Figure 2.

Azure Blob Storage Account with Sensor Data Containers.

Figure 2.

Azure Blob Storage Account with Sensor Data Containers.

Figure 3.

Apache NiFi Data Flow for IoT Sensor Processing and API Integration.

Figure 3.

Apache NiFi Data Flow for IoT Sensor Processing and API Integration.

Figure 4.

K-Fold Cross-Validation Process.

Figure 4.

K-Fold Cross-Validation Process.

Figure 6.

MATLAB Simulink Model for Real-Time Plant Growth Feedback System.

Figure 6.

MATLAB Simulink Model for Real-Time Plant Growth Feedback System.

Figure 10.

Simulated plant growth over time (in days).

Figure 10.

Simulated plant growth over time (in days).

Figure 11.

Example of Light Sensor Data in Azure Blob Storage Container.

Figure 11.

Example of Light Sensor Data in Azure Blob Storage Container.

Figure 12.

Correlation Between Light and Plant Growth.

Figure 12.

Correlation Between Light and Plant Growth.

Figure 13.

Correlation Between Moisture and Plant Growth.

Figure 13.

Correlation Between Moisture and Plant Growth.

Figure 14.

Correlation Between Phosphorus and Plant Growth.

Figure 14.

Correlation Between Phosphorus and Plant Growth.

Figure 15.

Correlation Between Temperature and Plant Growth.

Figure 15.

Correlation Between Temperature and Plant Growth.

Figure 16.

Correlation Between Nitrogen and Plant Growth.

Figure 16.

Correlation Between Nitrogen and Plant Growth.

Figure 17.

Correlation Between Potassium and Plant Growth.

Figure 17.

Correlation Between Potassium and Plant Growth.

Figure 18.

SVM Prediction of Growth.

Figure 18.

SVM Prediction of Growth.

Figure 19.

Gradient Boosting Prediction of Growth.

Figure 19.

Gradient Boosting Prediction of Growth.

Figure 20.

Deep Neural Network Prediction of Growth.

Figure 20.

Deep Neural Network Prediction of Growth.

Figure 21.

Time-Series Prediction of Growth.

Figure 21.

Time-Series Prediction of Growth.

Figure 22.

Growth Prediction Models Across Different Weeks.

Figure 22.

Growth Prediction Models Across Different Weeks.

Figure 23.

Resource Optimization Before and After IoT Implementation.

Figure 23.

Resource Optimization Before and After IoT Implementation.

Figure 24.

Real-Time Alert Accuracy Over Experiments.

Figure 24.

Real-Time Alert Accuracy Over Experiments.

Table 1.

Algorithm Inputs, Outputs, and Purpose in the Study.

Table 1.

Algorithm Inputs, Outputs, and Purpose in the Study.

| Algorithm |

Input Data |

Output |

Purpose |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) |

Weekly sensor data (light, moisture, nutrients) |

Binary classification (optimal/suboptimal conditions) |

Enables threshold adjustments for alerts and ensures environmental parameters remain optimal. |

| Gradient Boosting |

Historical sensor data |

Predicted growth (g) |

Guides long-term resource allocation by predicting plant development under different conditions. |

| Deep Neural Network (DNN) |

Time-series sensor data |

Growth forecasts (g) |

Proactive environmental adjustments to optimize nutrient and water supply. |

| Time Series Analysis |

Daily sensor readings |

Growth trends with tolerance bands |

Planning & watering scheduling based on predicted fluctuations. |

| Random Forest |

Sensor data + growth metrics |

Feature importance scores (0–1) |

Prioritizing critical environmental factors affecting plant growth. |

| Multivariate Regression |

All sensor variables |

Regression coefficients (β-values) |

Quantifies nutrient/growth relationships for targeted optimization. |

Table 2.

Algorithm Performance and Key Outputs.

Table 2.

Algorithm Performance and Key Outputs.

| Algorithm |

Input Data |

Key Output |

Impact on System Optimization |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) |

Weekly averages of light, moisture, and nutrients. |

96% alert accuracy for suboptimal conditions. |

Reduced over-watering by 15% through dynamic moisture threshold adjustments. |

| Gradient Boosting |

Historical sensor data aggregated weekly. |

Predicted Week 12 growth: 300g (vs. 301g actual). |

Guided nitrogen allocation, reducing usage by 30% while maintaining yield. |

| Deep Neural Network (DNN) |

Daily time-series sensor data (light, moisture, temperature). |

Week 6 growth forecast: 240g (vs. 179g actual). |

Highlighted mid-cycle prediction errors, prompting recalibration of temperature controls. |

| Time Series Analysis |

Daily sensor readings from Azure Blob Storage. |

Growth trends within ±5% tolerance bands. |

Optimized irrigation schedules, reducing water usage by 30%. |

| Random Forest |

Raw sensor data + growth metrics (biomass, height). |

Light importance: 0.778 (highest among factors). |

Prioritized light control in IAEM, contributing to a 25% reduction in energy consumption. |

| Multivariate Regression |

All sensor variables (light, moisture, temperature, N, P, K). |

Phosphorus (β=0.54), Potassium (β=-0.43). |

Identified potassium overuse, leading to a 40% reduction and balanced nutrient strategies. |

Table 3.

Comparison of Smart Farming Approaches.

Table 3.

Comparison of Smart Farming Approaches.

| System |

Our Azure-Based Pipeline (2024) |

ThingSpeak-Based System (2023) |

IoT Smart Farming (2019) |

Cloud-Based Smart Farming (2023) |

|

Cloud Platform

|

Azure IoT Hub, Blob Storage, Event Hub |

ThingSpeak Cloud |

Generic cloud platform |

Cloud computing services |

|

Data Processing

|

Advanced ETL pipeline with MATLAB Simulink |

Basic aggregation |

ML for irrigation |

IoT sensors, centralized processing |

|

Data Storage

|

Blob Storage with containers by sensor type |

Centralized in ThingSpeak |

General cloud storage |

Real-time cloud storage |

|

Sensors Used

|

Light, Moisture, Temp, N, P, K, CO2 sensors |

DHT11 for temp/humidity |

Soil moisture, temp, UV |

Temp, humidity, soil moisture, pH |

|

Hardware

|

Raspberry Pi for sensor integration |

Raspberry Pi Model B |

Zig bee-enabled sensors |

Raspberry Pi with sensors |

|

Real-Time Feedback

|

Dynamic adjustments via MATLAB Simulink |

No feedback loop |

Automated irrigation |

Manual/automated control |

|

Predictive Analytics

|

Gradient Boosting, SVM, Deep Neural Networks |

No predictive analytics |

ML for irrigation |

Basic ML for optimization |

|

Monitoring Tools

|

Power BI dashboards, real-time alerts |

Web/mobile apps |

Mobile apps, SMS alerts |

Web/mobile monitoring |

|

Decision Support

|

Predictive models, real-time alerts |

Alerts based on thresholds |

Automated decisions |

Limited decision support |

|

Security

|

Secure transfer with Azure authentication |

Basic security |

Secure communication |

IoT security protocols |

|

Scalability

|

Highly scalable for large-scale |

Small-scale applications |

Moderate scalability |

Scalable for small/medium farms |

|

Innovations

|

ETL pipeline, predictive analytics |

Cost-effective, simple monitoring |

IoT, ML for irrigation |

Combines IoT, ML, cloud |

|

Limitations

|

Might be Higher cost for larger scale |

Limited analytics, basic system |

Focuses on irrigation |

Limited predictive analytics |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).