Submitted:

23 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Chlorine Dioxide: Properties and Mechanism of Action

2.1. Chemical Properties

2.2. Antimicrobial Mechanism of Action

2.3. Antiviral Properties

3. Comparative Evaluation of Chlorine Dioxide and Alternative Disinfectants

4. Products by Chlorine Dioxide Production Methods

4.1. Sodium Chlorite-Based Methods

4.2. Sodium Chlorate-Based Methods

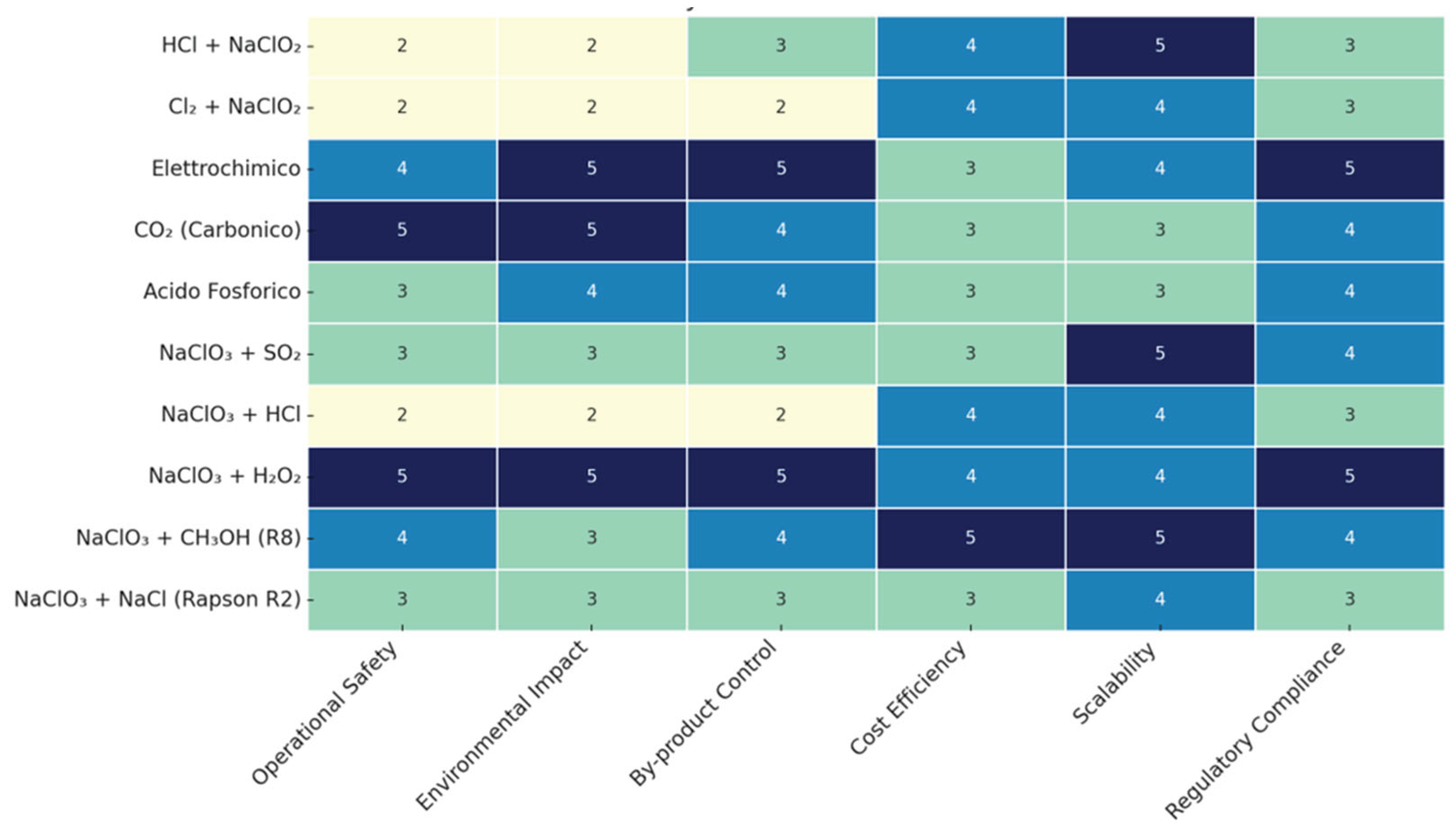

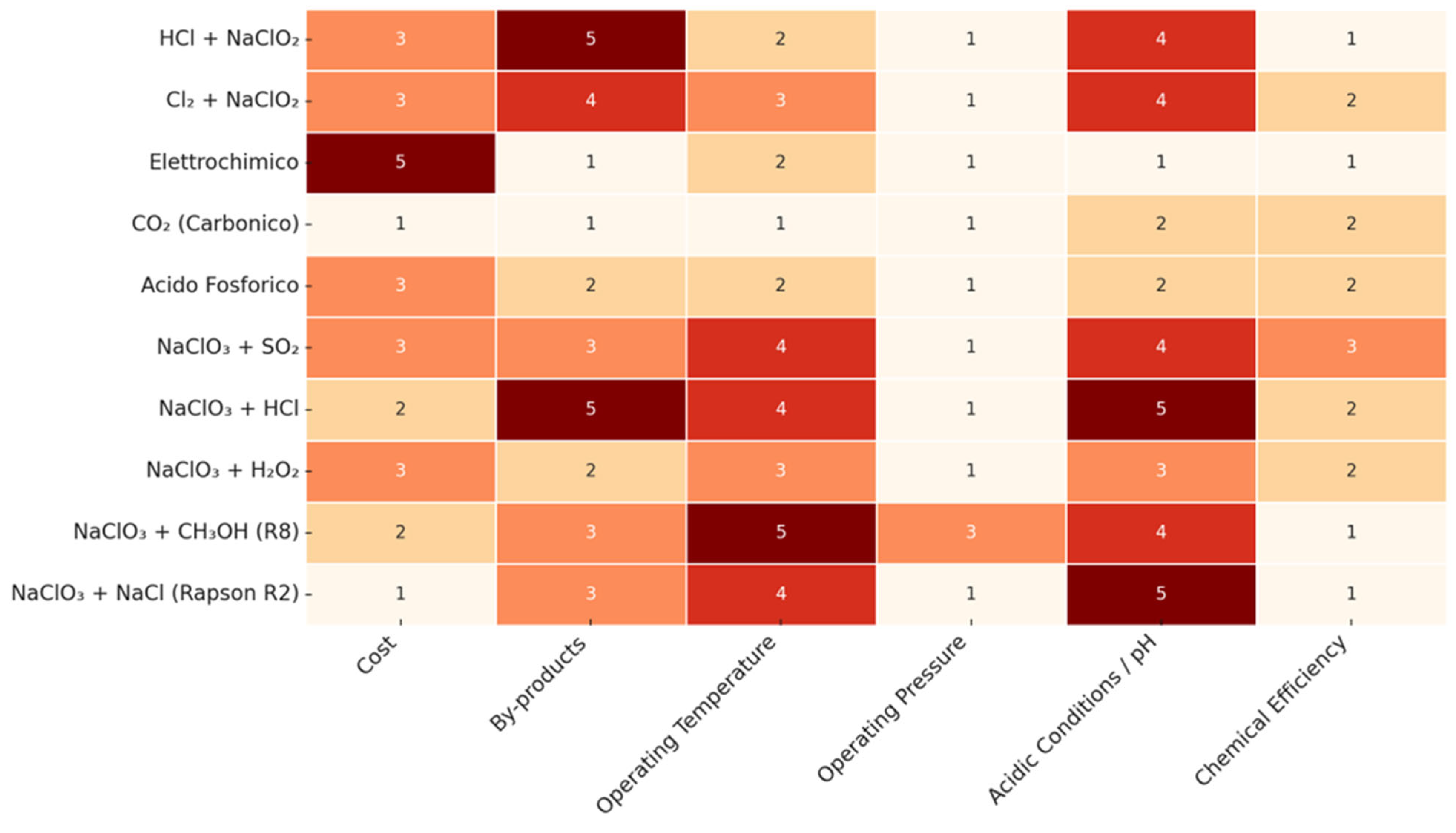

5. Comparative Evaluation Framework

6. Industrial Methods and Recent Advances

6.1. Proprietary Vacuum-Based Systems

6.2. Emerging Technologies and Research Directions

6.3. Outlook and Industry Trends

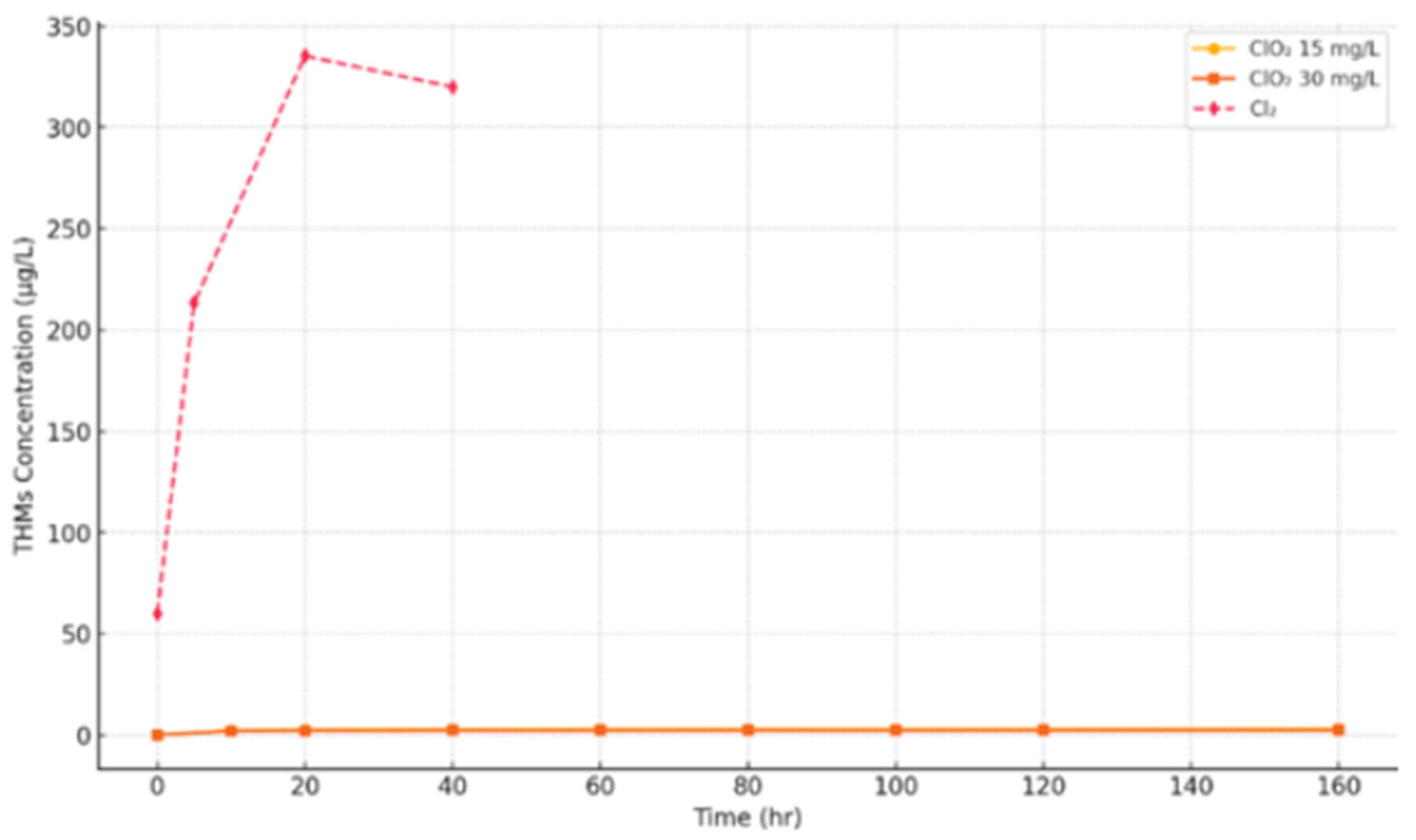

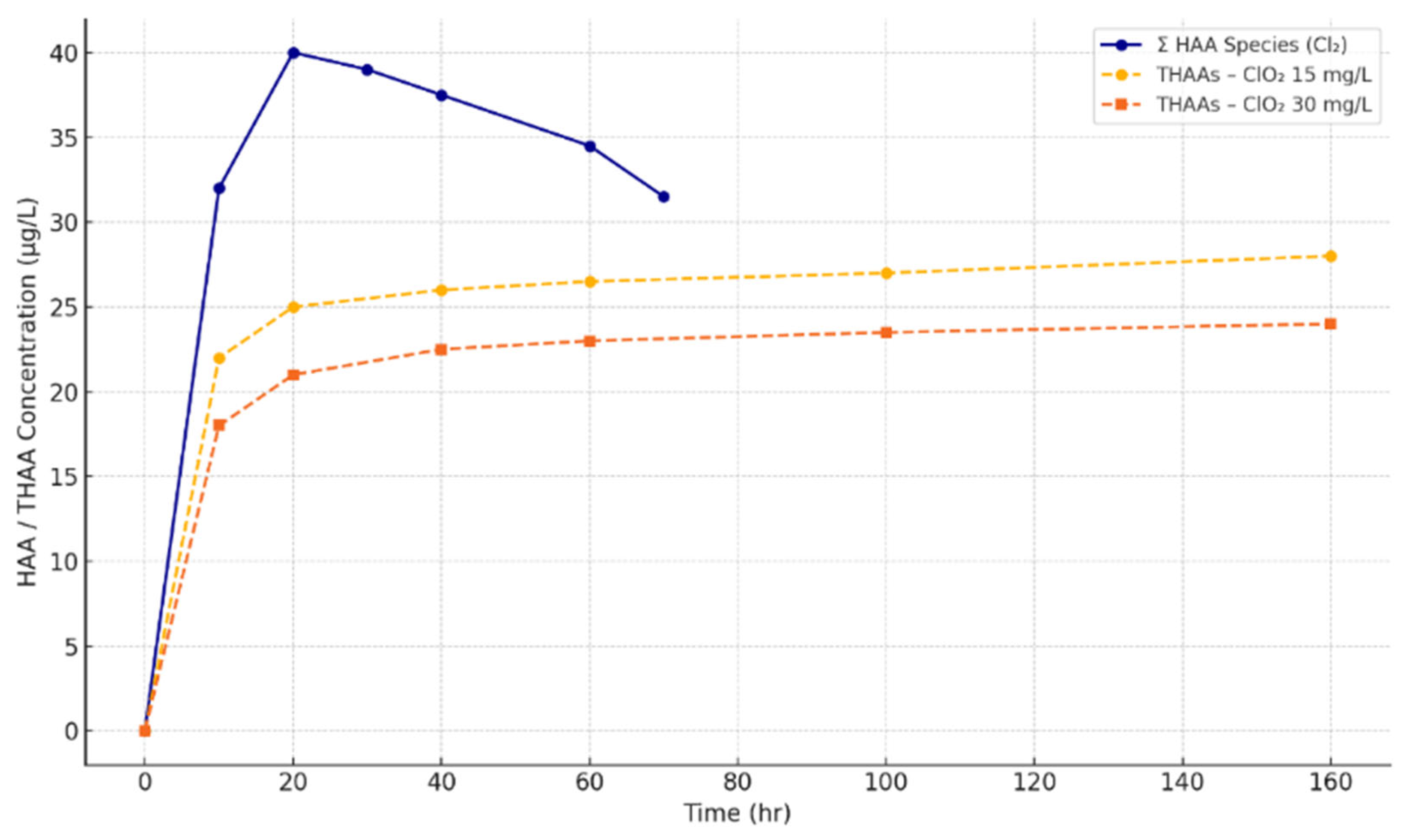

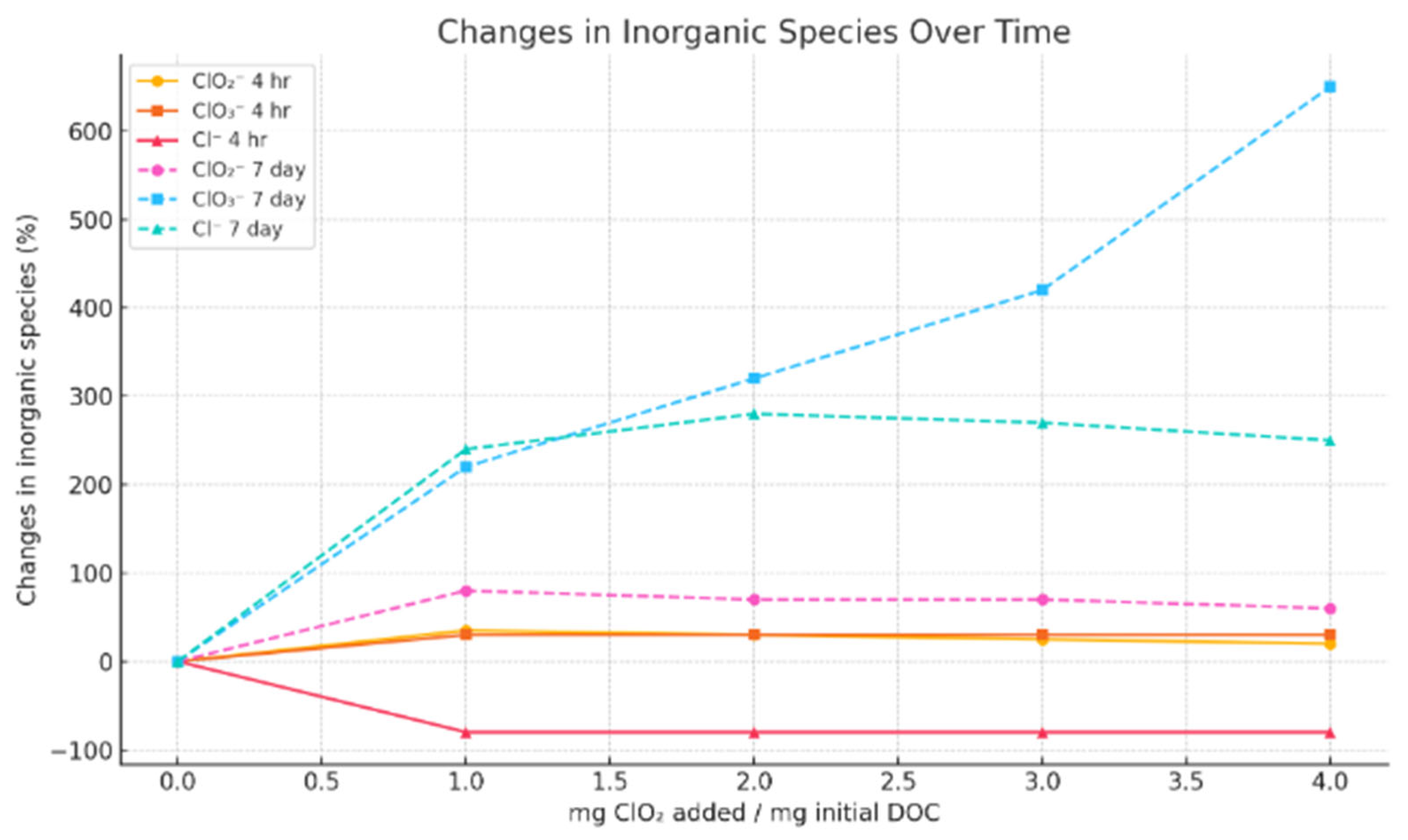

7. Disinfection By-Products

7.1. Health and Environmental Effects

7.2. Regulatory Aspects

8. Strategies for Mitigating the Formation of Disinfection By-Products from Chlorine Dioxide Application

8.1. Toxicological Characterization of Chlorine Dioxide and Its By-products

8.2. Strategies

9. Research Gaps and Future Outlook

Discussion

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gagnon, G. A.; Rand, J. L.; O’Leary, K. C.; Rygel, A. C.; Chauret, C.; Andrews, R. C. Disinfectant Efficacy of Chlorite and Chlorine Dioxide in Drinking Water Biofilms. Water Res 2005, 39(9), 1809–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorlini, S.; Gialdini, F.; Biasibetti, M.; Collivignarelli, C. Influence of Drinking Water Treatments on Chlorine Dioxide Consumption and Chlorite/Chlorate Formation. Water Res 2014, 54, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casini, B.; Buzzigoli, A.; Cristina, M. L.; Spagnolo, A. M.; Del Giudice, P.; Brusaferro, S.; Poscia, A.; Moscato, U.; Valentini, P.; Baggiani, A. Long-Term Effects of Hospital Water Network Disinfection on Legionella and Other Waterborne Bacteria in an Italian University Hospital. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 2014, 35(3), 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogata, N. Denaturation of Protein by Chlorine Dioxide: Oxidative Modification of Tryptophan and Tyrosine Residues. Biochemistry 2007, 46(16), 4898–4911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, G. Is All Chlorine Dioxide Created Equal? Journal of the American Water Works Association 2001, 93(4), 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, S. D.; Plewa, M. J.; Wagner, E. D.; Schoeny, R.; DeMarini, D. M. Occurrence, Genotoxicity, and Carcinogenicity of Regulated and Emerging Disinfection by-Products in Drinking Water: A Review and Roadmap for Research. Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research 2007, 636(1–3), 178–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, G.; Xu, X.; Huang, T.; Zhu, H.; Ma, J. Inactivation of Three Genera of Dominant Fungal Spores in Groundwater Using Chlorine Dioxide: Effectiveness, Influencing Factors, and Mechanisms. Water Res 2017, 125, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalakannan, Y.; Devi, K.M. A Review of Chlorine Dioxide: Efficacy, Applications and Health Implications in Disinfection. Journal of Chemical Health Risks 2024, 14(6), 2598–2604. [Google Scholar]

- Herczegh, A.; Ghidan, Á.; Friedreich, D.; Gyurkovics, M.; Bendő, Z.; Lohinai, Z. Effectiveness of a High Purity Chlorine Dioxide Solution in Eliminating Intracanal Enterococcus Faecalis Biofilm. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung 2013, 60(1), 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, G.; Reckhow, D. A. Comparison of Disinfection Byproduct Formation from Chlorine and Alternative Disinfectants. Water Res 2007, 41(8), 1667–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Chlorite and Chlorate in Drinking-Water: Background Document for Development of WHO Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 2005.

- Lubbers, J. R.; Chauan, S.; Bianchine, J. R. Controlled Clinical Evaluations of Chlorine Dioxide, Chlorite and Chlorate in Man. Environ Health Perspect 1982, 46, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon G, K. R. R. D. The Chemistry of Chlorine Dioxide. In Progress in Inorganic Chemistry; Lippard, SJ, Ed.; Wiley and Sons: New York, 1972; Vol. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, S. D.; Thruston, A. D.; Collette, T. W.; Patterson, K. S.; Lykins, B. W.; Majetich, G.; Zhang, Y. Multispectral Identification of Chlorine Dioxide Disinfection Byproducts in Drinking Water. Environ Sci Technol 1994, 28(4), 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.-F.; Mitch, W. A. Drinking Water Disinfection Byproducts (DBPs) and Human Health Effects: Multidisciplinary Challenges and Opportunities. Environ Sci Technol 2018, 52(4), 1681–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, S. D.; Thruston Jr, A. D.; Krasner, S. W.; Weinberg, H. S.; Miltner, R. J.; Schenck, K. M.; Narotsky, M. G.; McKague, A. B.; Simmons, J. E. Integrated Disinfection By-Products Mixtures Research: Comprehensive Characterization of Water Concentrates Prepared from Chlorinated and Ozonated/Postchlorinated Drinking Water. J Toxicol Environ Health A 2008, 71(17), 1165–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastidas-Ortiz. Chlorine Dioxide: Does It Contribute to Human Health? A Brief Review. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, G. D. Biofilm: Removal and Prevention with Chlorine Dioxide. Proc., 3rd Int. Symp. on chlorine dioxide, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ogata, N.; Shibata, T. Effect of Chlorine Dioxide Gas of Extremely Low Concentration on Absenteeism of Schoolchildren. Int J Med Med Sci 2009, 1(7), 288–289. https://doi.org/https://www.seirogan.co.jp/medical/pdf/report24.pdf.

- Driver, J; Lichterman, J; Lukasik, G; Jones, S; Bourgeois, M; Harbison, R. Bactericidal and Fungicidal Efficacy of Chlorine Dioxide in Various Workspaces. Occupational Diseases and Environmental Medicine 2022, 10, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, G; Rosenblatt, DH; Kuo, J. Chlorine Dioxide: Chemistry and Environmental Impact of Its Use in Water Treatment. In Water Chlorination: Chemistry, Environmental Impact and Health Effects; Jolley RL, B. R. D. W. K. S. R. M. J. V., Ed.; Lewis Publishers, 1990; Vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R. H.; Falkinham III, J. O.; Norton, C. D.; LeChevallier, M. W. Chlorine, Chloramine, Chlorine Dioxide, and Ozone Susceptibility of Mycobacterium Avium. Appl Environ Microbiol 2000, 66(4), 1702–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Protection, Agency. Toxicological Review of Chlorine Dioxide and Chlorite, 2000.

- Bercz, J. P.; Jones, L.; Garner, L.; Murray, D.; Ludwig, D.; Boston, J. Subchronic Toxicity of Chlorine Dioxide and Related Compounds in Drinking Water in the Nonhuman Primate. Environmental Health Perspectives 1982, 46, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aieta, E. M.; Berg, J. D. A Review of Chlorine Dioxide in Drinking Water Treatment. Journal of the American Water Works Association 1986, 78(6), 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wijk, D. J.; Kroon, S. G. M.; Garttener-Arends, I. C. M. Toxicity of Chlorate and Chlorite to Selected Species of Algae, Bacteria, and Fungi. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 1998, 40(3), 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Lavín, S; Irabien, A. Formation of Chlorate and Perchlorate during Electrochemical Production of Chlorine Dioxide Using Sodium Chlorite. Chemosphere 2019, 230, 460–468. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhu, X.; Gong, T. Characterization of Halogenated DBPs and Identification of New DBPs Trihalomethanols in Chlorine Dioxide Treated Drinking Water with Multiple Extractions. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2017, 58, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettlitz, B.; Gabriella, K.; Nigel, T.; Nele, C.; Ludovica, V.; Yves, L. B.-C.; Farai, M.; Aurélie, P.; Birgit, C.; and Stadler, R. H. Why Chlorate Occurs in Potable Water and Processed Foods: A Critical Assessment and Challenges Faced by the Food Industry. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part A 2016, 33(6), 968–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Shang, C.; Zhang, X.; Yang, X.; Yin, R. The Multiple Roles of Chlorite on the Concentrations of Radicals and Ozone and Formation of Chlorate during UV Photolysis of Free Chlorine. Water Res 2021, 190, 116680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Protection Agency. Reregistration Eligibility Decision (RED) for Chlorine Dioxide and Sodium Chlorite, 2006.

- Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Xie, Y.; Ni, T.; Liu, G. Oxidative Removal of Diclofenac by Chlorine Dioxide: Reaction Kinetics and Mechanism. Chemical Engineering Journal 2015, 279, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Bu, L.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, S.; Gao, N. Simultaneous Removal of Chlorite and Contaminants of Emerging Concern under UV Photolysis: Hydroxyl Radicals vs. Chlorate Formation. Water Res 2021, 190, 116708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, D.; Valdivia-Garcia, M.; Weir, P.; Haffey, M. Trihalomethanes Formation in Point of Use Surface Water Disinfection with Chlorine or Chlorine Dioxide Tablets. Water and Environment Journal 2016, 30(3–4), 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalvi, A.G.I.; Al-Rasheed, R.; Javeed, M.A. Haloacetic Acids (HAAs) Formation in Desalination Processes from Disinfectants. Desalination 2000, 129(3), 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C. Y.; Hsieh, Y. H.; Hsu, S. S.; Hu, P. Y.; Wang, K. H. The Formation of Disinfection By-Products in Water Treated with Chlorine Dioxide. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2000, 79(1–2), 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noszticzius, Z.; Wittmann, M.; Kály-Kullai, K.; Beregvári, Z.; Kiss, I.; Rosivall, L.; Szegedi, J. Chlorine Dioxide Is a Size-Selective Antimicrobial Agent. PLoS One 2013, 8(11), e79157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ison, A.; Odeh, I. N.; Margerum, D. W. Kinetics and Mechanisms of Chlorine Dioxide and Chlorite Oxidations of Cysteine and Glutathione. Inorg Chem 2006, 45(21), 8768–8775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napolitano, M. J.; Green, B. J.; Nicoson, J. S.; Margerum, D. W. Chlorine Dioxide Oxidations of Tyrosine, N-Acetyltyrosine, and Dopa. Chem Res Toxicol 2005, 18(3), 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, D. J.; Napolitano, M. J.; Bakhmutova-Albert, E. V; Margerum, D. W. Kinetics and Mechanisms of Chlorine Dioxide Oxidation of Tryptophan. Inorg Chem 2008, 47(5), 1639–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loginova, I. V; Rubtsova, S. A.; Kuchin, A. V. Oxidation by Chlorine Dioxide of Methionine and Cysteine Derivatives to Sulfoxides. Chem Nat Compd 2008, 44, 752–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, T.; Shibata, T. Antiviral Effect of Chlorine Dioxide against Influenza Virus and Its Application for Infection Control. The Open Antimicrobial Agents Journal 2010, 2(1), 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, RF. Biochemistry, 2nd ed. D. Voet and J.G. Voet., Ed. 1996.

- Rubio-Casillas, A.; Campra-Madrid, P. Farmacocinética y Farmacodinamia Del Dióxido de Cloro. e-CUCBA 2021, No. 16. 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Guo, Y.; Yu, P.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Dong, W.; Liu, X.; Guo, C. Chlorine Dioxide Inhibits the Replication of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus by Blocking Viral Attachment. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2019, 67, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesney, J. A.; Eaton, J. W.; Mahoney, J. R. Bacterial Glutathione: A Sacrificial Defense against Chlorine Compounds. Journal of Bacteriology 1996, 178, 2131–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, D. H.; Abdel-Rahman, M. S.; Bull, R. J. Effect of Chlorine Dioxide and Its Metabolites in Drinking Water on Fetal Development in Rats. Journal of applied toxicology 1983, 3(2), 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saguti, F.; Kjellberg, I.; Churqui, M. P.; Wang, H.; Tunovic, T.; Ottoson, J.; Bergstedt, O.; Norder, H.; Nyström, K. The Virucidal Effect of the Chlorination of Water at the Initial Phase of Disinfection May Be Underestimated If Contact Time Calculations Are Used. Pathogens 2023, 12(10), 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadota, C.; Miyaoka, Y.; Kabir, M. H.; Hakim, H.; Hasan, M. A.; Shoham, D.; Murakami, H.; Takehara, K. Evaluation of Chlorine Dioxide in Liquid State and in Gaseous State as Virucidal Agent against Avian Influenza Virus and Infectious Bronchitis Virus. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 2023, 85(10), 1040–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peredo-Lovillo, A.; Romero-Luna, H. E.; Juárez-Trujillo, N.; Jiménez-Fernández, M. Antimicrobial Efficiency of Chlorine Dioxide and Its Potential Use as Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Agent: Mechanisms of Action and Interactions with Gut Microbiota. J Appl Microbiol 2023, 134(7), lxad133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benarde, M. A.; Snow, W. B.; Olivieri, V. P.; Davidson, B. Kinetics and Mechanism of Bacterial Disinfection by Chlorine Dioxide. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1967, 15, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watamoto, T.; Egusa, H.; Sawase, T.; Yatani, H. Clinical Evaluation of Chlorine Dioxide for Disinfection of Dental Instruments. International Journal of Prosthodontics 2013, 26(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, B.; Jin, M.; Yang, D.; Guo, X.; Chen, Z.; Shen, Z.; Wang, X.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, B. Effects of Chlorine and Chlorine Dioxide on Human Rotavirus Infectivity and Genome Stability. Water Res 2013, 47(10), 3329–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, M.; Mattison, K.; Fliss, I.; Jean, J. Efficacy of Oxidizing Disinfectants at Inactivating Murine Norovirus on Ready-to-Eat Foods. Int J Food Microbiol 2016, 219, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefri, UHN; Khan, A; Lim, YC; Lee, KS; Liew, KB; Kassab, YW; Choo, CY; Al-Worafi, YM; Ming, LC; Kalusalingam, A. A Systematic Review on Chlorine Dioxide as a Disinfectant. J Med Life 2022, 15(3), 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Chen, X.; Luo, J.; Shi, P.; Zhou, Q.; Li, A.; Pan, Y. Comparison of Chlorine and Chlorine Dioxide Disinfection in Drinking Water: Evaluation of Disinfection Byproduct Formation under Equal Disinfection Efficiency. Water Res 2024, 260, 121932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G. W. An Assessment of Ozone and Chlorine Dioxide Technologies for Treatment of Municipal Water Supplies, Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development, 1978; Vol. 1.

- Richardson, S. D.; Thruston, A. D.; Rav-Acha, C.; Groisman, L.; Popilevsky, I.; Juraev, O.; Glezer, V.; McKague, A. B.; Plewa, M. J.; Wagner, E. D. Tribromopyrrole, Brominated Acids, and Other Disinfection Byproducts Produced by Disinfection of Drinking Water Rich in Bromide. Environ Sci Technol 2003, 37(17), 3782–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Gunten, U. Ozonation of Drinking Water: Part II. Disinfection and by-Product Formation in Presence of Bromide, Iodide or Chlorine. Water Res 2003, 37(7), 1469–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasner, S. W.; Weinberg, H. S.; Richardson, S. D.; Pastor, S. J.; Chinn, R.; Sclimenti, M. J.; Onstad, G. D.; Thruston, A. D. Occurrence of a New Generation of Disinfection Byproducts. Environ Sci Technol 2006, 40(23), 7175–7185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Shang, C.; Westerhoff, P. Factors Affecting Formation of Haloacetonitriles, Haloketones, Chloropicrin and Cyanogen Halides during Chloramination. Water Res 2007, 41(6), 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasi, E. M.; Wohlsen, T. D.; Stratton, H. M.; Katouli, M. Survival of Escherichia Coli in Two Sewage Treatment Plants Using UV Irradiation and Chlorination for Disinfection. Water Res 2013, 47, 6670–6679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Jiang, J. Low Chlorine Impurity Might Be Beneficial in Chlorine Dioxide Disinfection. Water Res 2021, 188, 116520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Peng, J.; Yin, R.; Fan, M.; Yang, X.; Shang, C. Multi-Angle Comparison of UV/Chlorine, UV/Monochloramine, and UV/Chlorine Dioxide Processes for Water Treatment and Reuse. Water Res 2022, 217, 118414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberti, L.; Notarnicola, M. Advanced Treatment and Disinfection for Municipal Wastewater Reuse in Agriculture. Water Science and technology 1999, 40(4–5), 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, S. S. Disinfection, Sterilization, and Preservation. , 4th ed.; Lea and Febiger, Ed.; Philadelphia, USA, 1991.

- Monarca, S.; Feretti, D.; Zerbini, I.; Zani, C.; Alberti, A.; Richardson, S. D.; Thruston Jr, A. D.; Ragazzo, P.; Guzzella, L. Studies on Mutagenicity and Disinfection By-Products in River Drinking Water Disinfected with Peracetic Acid or Sodium Hypochlorite. Water Sci Technol Water Supply 2002, 2(3), 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Boyd, J. M.; Zhou, W.; Li, X. A Toxic Disinfection By-product, 2, 6-dichloro-1, 4-benzoquinone, Identified in Drinking Water. Angewandte Chemie 2010, 122(4), 802–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, X. Four Groups of New Aromatic Halogenated Disinfection Byproducts: Effect of Bromide Concentration on Their Formation and Speciation in Chlorinated Drinking Water. Environ Sci Technol 2013, 47(3), 1265–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, J.; Laha, S. Water Purification Systems: A Comparative Analysis Based on the Occurrence of Disinfection by-Products. Environmental Pollution 1999, 106(3), 425–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, S.; Kumar, A. Chlorination Disinfection By-Products and Comparative Cost Analysis of Chlorination and UV Disinfection in Sewage Treatment Plants: Indian Scenario. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2017, 24, 26269–26278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardi M; Giugni M; De Paola F. Formation of Trihalomethanes in Water Systems. A Case Study: The Serino Aqueduct. , University of Naples “Federico II", Naples, 2016.

- Beltrán, F. J.; Rey, A.; Gimeno, O. The Role of Catalytic Ozonation Processes on the Elimination of DBPs and Their Precursors in Drinking Water Treatment. Catalysts 2021, 11, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doré, M. Chemistry of Oxydants and Treatment of Water.; Techniques et Documentation: Paris, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Langlais, B.; Reckhow, D. A.; Brink, D. R. Ozone in Water Treatment. Application and engineering 1991, 558. [Google Scholar]

- Han, G. D.; Kwon, H.; Kim, B. H.; Kum, H. J.; Kwon, K.; Kim, W. Effect of Gaseous Chlorine Dioxide Treatment on the Quality of Rice and Wheat Grain. J Stored Prod Res 2018, 76, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, L; Forrest, H; Fakis, A; Craig, J; Claxton, L; Khare, M. Clinical and Cost Effectiveness of Eight Disinfection Methods for Terminal Disinfection of Hospital Isolation Rooms Contaminated with Clostridium Difficile 027. Journal of Hospital infection 2012, 82(2), 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcon, J.; Mortha, G.; Marlin, N.; Molton, F.; Duboc, C.; Burnet, A. New Insights into the Decomposition Mechanism of Chlorine Dioxide at Alkaline PH. Holzforschung 2017, 71(7–8), 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svenson, D. R.; Kadla, J. F.; Chang, H.; Jameel, H. Effect of PH on the Inorganic Species Involved in a Chlorine Dioxide Reaction System. Ind Eng Chem Res 2002, 41(24), 5927–5933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, W. G. Handbook of Chlorination and Alternative Disinfectants. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold 1992.

- Jaszka DJ; Partridge HD. Production of Chlorine Dioxide Having Low Chlorine Content. . 4216195A, 1980. https://patents.google.com/patent/US4216195A/en (accessed 2025-05-20).

- Cornelius, S. E. Manufacture of Chlorine Dioxide. 2332181A, 1993. https://patents.google.com/patent/US2332181A/en (accessed 2025-05-20).

- Marc L. Method and Device for the Treatment of a Fluid Using Chlorine Dioxide Produced in Situ. . 2855167, 2004.

- Pillai, K. C.; Kwon, T. O.; Park, B. B.; Moon, I. S. Studies on Process Parameters for Chlorine Dioxide Production Using IrO2 Anode in an Un-Divided Electrochemical Cell. J Hazard Mater 2009, 164(2–3), 812–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.-T.; Chang, C.-Y.; Hsieh, Y.-H. The Generation of Chlorine Dioxide by Electrochemistry Technology. Adv Sci Lett 2013, 19(11), 3285–3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadlec LJ; Kilawee PH. Electrochemical Generation of Chlorine Dioxide. . 6869518B2, 2005. https://patents.google.com/patent/US6869518B2/en (accessed 2025-05-20).

- Brito, C. N.; Araújo, D. M.; Martínez-Huitle, C. A. A.; Rodrigo, M. A. Understanding Active Chlorine Species Production Using Boron Doped Diamond Films with Lower and Higher Sp3/Sp2 Ratio. Elecrochemistry Communications 2015, 55, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, E.; Reinsberg, P.; Garcia-Segura, S.; Baltruschat, H. Chlorine Species Evolution during Electrochlorination on Boron-Doped Diamond Anodes: In-Situ Electrogeneration of Cl2, Cl2O and ClO2. Electrochim Acta 2018, 281, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, F. de L.; Saéz, C.; Lanza, M. R. de V.; Cañizares, P.; Rodrigo, M. A. The Effect of the Sp3/Sp2 Carbon Ratio on the Electrochemical Oxidation of 2, 4-D with p-Si BDD Anodes. Electrochim Acta 2016, 187, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roensch LF; Tribble RH; Hilliard D. Method for Generating Chlorine Dioxide. 6436345B1, 2004. https://patents.google.com/patent/US6436345B1/en (accessed 2025-05-20).

- Shirasaki, Y.; Matsuura, A.; Uekusa, M.; Ito, Y.; Hayashi, T. A Study of the Properties of Chlorine Dioxide Gas as a Fumigant. Exp Anim 2016, 65(3), 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, JE; Battisti, DL. Chlorine Dioxide. Disinfection, Sterilization and Preservation 2001, 5, 215–228. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.; Deng, J.; Cai, A.; Ye, C.; Ma, X.; Li, Q.; Zhou, S.; Li, X. Synergistic Effects of UVC and Oxidants (PS vs. Chlorine) on Carbamazepine Attenuation: Mechanism, Pathways, DBPs Yield and Toxicity Assessment. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 413, 127533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang S; Qin C; Song X; Li X; Nie S; Liang C. Method and System for the Integral Chlorine Dioxide Production with Relatively Independent Sodium Chlorate Electrolytic Production and Chlorine Dioxide Production. 9776163B1, 2017. https://patents.google.com/patent/US9776163B1/en (accessed 2025-05-20).

- Chen, T.; Wu, Y.; Xiao, S. Method of Producing Chlorine Dioxide Employs Alkaline Chlorate in a Mineral Acid Medium and Urea as a Reducing Agent. . 6921521B2, 2005. https://patents.google.com/patent/US6921521B2/en (accessed 2025-05-20).

- Romero-Fierro, D.; Bustamante-Torres, M.; Hidalgo-Bonilla, S.; Bucio, E. Microbial Degradation of Disinfectants. Recent advances in microbial degradation 2021, 91–130. [Google Scholar]

- Wickström P. Procedure for Production of Chlorine Dioxide. 5145660A, 1993. https://patents.google.com/patent/US5145660A/en (accessed 2025-05-20).

- Qi, M.; Yi, T.; Mo, Q.; Huang, L.; Zhao, H.; Xu, H.; Huang, C.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Hui, Z. Preparation of High-Purity Chlorine Dioxide by Combined Reduction. Chem Eng Technol 2020, 43(9), 1850–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, M. K. S.; Moratalla, Á.; Sáez, C.; Dos Santos, E. V; Rodrigo, M. A. Production of Chlorine Dioxide Using Hydrogen Peroxide and Chlorates. Catalysts 2021, 11(12), 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, M. K. S.; Monteiro, M. M. S.; de Melo Henrique, A. M.; Llanos, J.; Saez, C.; Dos Santos, E. V.; Rodrigo, M. A. A Review on the Electrochemical Production of Chlorine Dioxide from Chlorates and Hydrogen Peroxide. Curr Opin Electrochem 2021, 27, 100685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.; Tenney, J.; Indu, B.; Hoq, M. F.; Carr, S.; Ernst, W. R. Kinetics of Hydrogen Peroxide-Chlorate Reaction in the Formation of Chlorine Dioxide. Industrial and Engineering Chemistry Research 1993, 32(7), 1449–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, J. F.; Llanos, J.; Sáez, C.; López, C.; Cañizares, P.; Rodrigo, M. A. The Jet Aerator as Oxygen Supplier for the Electrochemical Generation of H2O2. Electrochim Acta 2017, 246, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, J. F.; Llanos, J.; Sáez, C.; López, C.; Cañizares, P.; Rodrigo, M. A. The Pressurized Jet Aerator: A New Aeration System for High-Performance H2O2 Electrolyzers. Electrochem commun 2018, 89, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, J. F.; Galia, A.; Rodrigo, M. A.; Llanos, J.; Sabatino, S.; Sáez, C.; Schiavo, B.; Scialdone, O. Effect of Pressure on the Electrochemical Generation of Hydrogen Peroxide in Undivided Cells on Carbon Felt Electrodes. Electrochim Acta 2017, 248, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Wang, X. Mechanism and Kinetics of Chlorine Dioxide Reaction with Hydrogen Peroxide under Acidic Conditions. Can J Chem Eng 1997, 75(1), 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indu B; Bhart; Ernst WR; William R. Kinetics and Mechanism of Methanol–Chlorate in the Formation of Chlorine Dioxide. , Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, 1993.

- Indu, B.; Hoq, M. F.; Ernst, W. R.; Neumann, H. M. Kinetics of the Reaction of Chlorine with Formaldehyde in Aqueous Sulfuric Acid. Ind Eng Chem Res 1991, 30(6), 1077–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoq, M. F.; Indu, B.; Ernst, W. R.; Gelbaum, L. T. Oxidation Products of Methanol in Chlorine Dioxide Production. Ind Eng Chem Res 1992, 31(7), 1807–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoq, M. F.; Indu, B.; Ernst, W. R.; Neumann, H. M. Kinetics of the Reaction of Chlorine with Formic Acid in Aqueous Sulfuric Acid. J Phys Chem 1991, 95(2), 681–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoq, M. F.; Indu, B.; Neumann, H. M.; Ernst, W. R. Influence of Chloride on the Chlorine-Formic Acid Reaction in Sulfuric Acid. J Phys Chem 1991, 95(22), 9023–9024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredette MCJ; Bigauskas TD; Bechberger EJ. Methanol-Based Chlorine Dioxide Process. . 0535113A1, 1995. https://patents.google.com/patent/EP0535113A1/de (accessed 2025-05-20).

- McIlwaine D; Richardson J. Reducing Agents for Producing Chlorine Dioxide. 9567216B2, 2017. https://patents.google.com/patent/US9567216B2/en (accessed 2025-05-20).

- Rapson, W. H. From Laboratory Curiosity to Heavy Chemical. Chemistry Canada 1966, 18(1), 2531. [Google Scholar]

- Rapson WH; Fredette MCJ. Small Scale Generation of Chlorine-Dioxide for Water Treatment. 4534952A, 1985. https://patents.google.com/patent/US4534952A/en (accessed 2025-05-20).

- Fredette M.C.J.; Cowley G. Production of Chlorine-Dioxide on a Small Scale. . 4414193A, 1983. https://patents.google.com/patent/US4414193A/en (accessed 2025-05-20).

- Tenney, J.; Shoaei, M.; Obijeski, T.; Ernst, W. R.; Lindstroem, R.; Sundblad, B.; Wanngard, J. Experimental Investigation of a Continuous Chlorine Dioxide Reactor. Ind Eng Chem Res 1990, 29(5), 912–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, WR; Shoaei, M; Forney, L. Selectivity Behaviour of the Chloride–Chlorate Reaction in Various Reactor Types. AIChE Journal 1998, 34, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshwal, B. R.; Lee, H. K. Kinetics and Mechanism of Chloride-Based Chlorine Dioxide Generation Process from Acidic Sodium Chlorate. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2004, 108, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbottle, G. The Hammett Acidity Function in 6 Formal Perchloric Acid—Sodium Perchlorate Mixtures. J Am Chem Soc 1951, 73(8), 4024–4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. G.; Stewart, R. H 0 Acidity Functions for Nitric and Phosphoric Acid Solutions containing added Sodium Perhlorate. Can J Chem 1964, 42(2), 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, J. S.; Wyatt, P. A. H. H₀ Measurements in Some Salt–Acid Mixtures of Fixed Total Anion Concentration. Journal of the American Society B: Physical Organic 1966, 343–345. [Google Scholar]

- Rochester, C. H. Acidity Functions. Academic Press, L. 1970.

- Holm TC. The Hidden Cost of Chlorine Dioxide.

- Gordon, G; Rosenblatt, AA. Chlorine Dioxide: The Current State of the Art. Ozone Sci Eng 2005, 27(3), 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, N. F. Chapter Thirty-Two - Chlorine Dioxide. In Microbiology of Waterborne Diseases (Second Edition); Percival, S. L., Yates, M. V, Williams, D. M., Chalmers, R. M., Gray, N. F., Eds.; Academic Press: London, 2014; pp. 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhongren N; Yuping Z. Process for Producing Chlorine Dioxide by Carbon Dioxide and Sodium Chlorite. 1295142C, 2007. https://patents.google.com/patent/CN1295142C/en (accessed 2025-05-20).

- Anfruns-Estrada, E.; Bottaro, M.; Pintó, R. M.; Guix, S.; Bosch, A. Effectiveness of Consumers Washing with Sanitizers to Reduce Human Norovirus on Mixed Salad. Foods 2019, 8(12), 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouryon. Chlorine Dioxide Technologies: Best Available Techniques (BAT) for ClO₂ Production. ; 2021.

- Min, Z. H. U.; Zhang, L.-S.; Xiao-Fang, P. E. I.; Xin, X. U. Preparation and Evaluation of Novel Solid Chlorine Dioxide-Based Disinfectant Powder in Single-Pack. Biomedical and Environmental Sciences 2008, 21(2), 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, X. Comparative Toxicity of New Halophenolic DBPs in Chlorinated Saline Wastewater Effluents against a Marine Alga: Halophenolic DBPs Are Generally More Toxic than Haloaliphatic Ones. Water Res 2014, 65, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terhalle, J.; Kaiser, P.; Jütte, M.; Buss, J.; Yasar, S.; Marks, R.; Uhlmann, H.; Schmidt, T. C.; Lutze, H. V. Chlorine Dioxide—Pollutant Transformation and Formation of Hypochlorous Acid as a Secondary Oxidant. Environ Sci Technol 2018, 52(17), 9964–9971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y.; Gan, W.; Du, Y.; Huang, H.; Wu, Q.; Xiang, Y.; Shang, C.; Yang, X. Disinfection Byproducts and Their Toxicity in Wastewater Effluents Treated by the Mixing Oxidant of ClO2/Cl2. Water Res 2019, 162, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Shang, C.; Xiang, Y.; Yin, R.; Pan, Y.; Fan, M.; Yang, X. ClO2 Pre-Oxidation Changes Dissolved Organic Matter at the Molecular Level and Reduces Chloro-Organic Byproducts and Toxicity of Water Treated by the UV/Chlorine Process. Water Res 2022, 216, 118341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Otoum, F.; Al-Ghouti, M. A.; Ahmed, T. A.; Abu-Dieyeh, M.; Ali, M. Disinfection By-Products of Chlorine Dioxide (Chlorite, Chlorate, and Trihalomethanes): Occurrence in Drinking Water in Qatar. Chemosphere 2016, 164, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werdehoff, K. S.; Singer, P. C. Chlorine Dioxide Effects on THMFP, TOXFP, and the Formation of Inorganic By-products. Journal-American Water Works Association 1987, 79(9), 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, D. The Chlorine Dioxide Handbook; AWWA: Washington, DC, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Griese, M. H.; Kaczur, J. J.; Gordon, G. Combining Methods for the Reduction of Oxychlorine Residuals in Drinking Water. Journal AWWA 1992, 84(11), 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison J; Mole N; Fielding M. Bromate and Chlorate in Water: The Role of Hypochlorite. . In Proceedings of the First International Research Symposium on Water Treatment By-products. ; Poitiers, 1994.

- World Health Organization. Chlorine Dioxide, Chlorite and Chlorate in Drinking-Water. WHO/SDE/WSH/05.08/86; 2016.

- Adam, L. C.; Suzuki, K.; Gordon, G.; Fábián, I. Hypochlorous Acid Decomposition in the PH 5-8 Region. Inorg Chem 1992, 31(17), 3534–3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford, B. D.; Pisarenko, A. N.; Snyder, S. A.; Gordon, G. Perchlorate, Bromate, and Chlorate in Hypochlorite Solutions: Guidelines for Utilities. Journal-American Water Works Association 2011, 103(6), 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Yang, X.; Kong, Q.; Lei, Y.; Zhang, X.; Aghdam, E.; Yin, R.; Shang, C. Sequential ClO2-UV/Chlorine Process for Micropollutant Removal and Disinfection Byproduct Control. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 806, 150354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés, C. M. C.; Lastra, J. M. P.; Andrés Juan, C.; Plou, F. J.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. Chlorine Dioxide : Friend or Foe for Cell Biomolecules? A Chemical Approach. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23(24), 15660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulman, D. M.; Mezyk, S. P.; Remucal, C. K. The Impact of PH and Irradiation Wavelength on the Production of Reactive Oxidants during Chlorine Photolysis. Environmental Science and Technology 2019, 53(8), 4450–4459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fábián, I; Gordon, G. The Kinetics and Mechanism of the Chlorine Dioxide–Iodide Ion Reaction. Inorg Chem 1997, 2494–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukutomi, Hiroshi.; Gordon, Gilbert. Kinetic Study of the Reaction between Chlorine Dioxide and Potassium Iodide in Aqueous Solution. J Am Chem Soc 1967, 89(6), 1362–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, D. M.; Kim, C.-H. Iodine Catalysis in the Chlorite-Iodide Reaction1. J Am Chem Soc 1965, 87(23), 5309–5313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huie, R. E.; Neta, P. Kinetics of One-Electron Transfer Reactions Involving Chlorine Dioxide and Nitrogen Dioxide. J Phys Chem 1986, 90(6), 1193–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanbury, D. M.; Martinez, R.; Tseng, E.; Miller, C. E. Slow Electron Transfer between Main-Group Species: Oxidation of Nitrite by Chlorine Dioxide. Inorg Chem 1988, 27(23), 4277–4280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rougè VR. Chlorine Dioxide Oxidation in Water Treatment: Impact on Natural Organic Matter Characteristics, Disinfection Byproducts and Comparison with Other Oxidants, Curtin University, Bentley, WA, Australia, 2018.

- Lengyel, I.; Li, J.; Kustin, K.; Epstein, I. R. Rate Constants for Reactions between Iodine-and Chlorine-Containing Species: A Detailed Mechanism of the Chlorine Dioxide/Chlorite-Iodide Reaction. J Am Chem Soc 1996, 118(15), 3708–3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorlini, S.; Collivignarelli, C. Chlorite Removal with Granular Activated Carbon. Desalination 2005, 176(1–3), 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfredo, K.; Stanford, B.; Roberson, J. A.; Eaton, A. Chlorate Challenges for Water Systems. Journal of the American Water Works Association 2015, 107, E187–E196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubbers, J. R.; Chauhan, S.; Bianchine, J. R. Controlled Clinical Evaluations of Chlorine Dioxide, Chlorite and Chlorate in Man. Fundamental and applied Toxicology 1981, 1(4), 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orme, J.; Taylor, D. H.; Laurie, R. D.; Bull, R. J. Effects of Chlorine Dioxide on Thyroid Function in Neonatal Rats. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A Current Issues 1985, 15(2), 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, D. H.; Pfohl, R. J. Effects of Chlorine Dioxide on Neurobehavioral Development of Rats. Water chlorination 1985, 5, 355–364. [Google Scholar]

- Toth, G. P.; Long, R. E.; Mills, T. S.; Smith, M. K. Effects of Chlorine Dioxide on the Developing Rat Brain. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A Current Issues 1990, 31(1), 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haag, HB. The Effect on Rats of Chronic Administration of Sodium Chlorite and Chlorine Dioxide in the Drinking Water. Report to the Mathieson Alkali Works from the Medical College of Virginia 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Gauss, W. Physiological and Histological Criteria of Thyroid Gland Function during a Single or Longer Treatment of Potassium Perchlorate in Adult Mice (Mus Musculus). Z Mikrosk Anat Forsch 1999, 85(1), 469–500. [Google Scholar]

- York, R. G.; Brown, W. R.; Girard, M. F.; Dollarhide, J. S. Two-Generation Reproduction Study of Ammonium Perchlorate in Drinking Water in Rats Evaluates Thyroid Toxicity. Int J Toxicol 2001, 20(4), 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.-W.; Huang, B.-S.; Hsu, C.-W.; Peng, C.-W.; Cheng, M.-L.; Kao, J.-Y.; Way, T.-D.; Yin, H.-C.; Wang, S.-S. Efficacy and Safety Evaluation of a Chlorine Dioxide Solution. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017, 14(3), 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, MA; Goodman, G; Pleus, RC. Health Effects Assessment for Environmental Perchlorate Contamination: The Dose Response for Inhibition of Thyroidal Radioiodine Uptake in Humans. Environ Health Perspect 2002, 110(9), 927–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon K.L.; Lee R.G. Disinfection By-Products Control: A Survey of American System Treatment Plants. . In AWWA Conference; Philadelphia, 1991.

- Katz, A.; Narkis, N. Removal of Chlorine Dioxide Disinfection By-Products by Ferrous Salts. Water Res 2001, 35(1), 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonce, N.; Voudrias, E. A. Removal of Chlorite and Chlorate Ions from Water Using Granular Activated Carbon. Water Res 1994, 28(5), 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, T. F.; Bommaraju, T. V; Hine, F. Handbook of Chlor-Alkali Technology: Volume I: Fundamentals, Volume II: Brine Treatment and Cell Operation, Volume III: Facility Design and Product Handling, Volume IV: Plant Commissioning and Support Systems, Volume V: Corrosion, Environmental Issues, and Future Development; Springer, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Cassol, G. S.; Shang, C.; Li, J.; Ling, L.; Yang, X.; Yin, R. Dosing Low-Level Ferrous Iron in Coagulation Enhances the Removal of Micropollutants, Chlorite and Chlorate during Advanced Water Treatment. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2022, 117, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phougat, N.; Vasudevan, P.; Jha, N. K.; Bandhopadhyay, D. K. Metal Porphyrins as Electrocatalysts for Commercially Important Reactions. Transition metal chemistry 2003, 28, 838–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.; Bonnesen, P. V; Sloop, F. V; Brown, G. M. Titanium Catalyzed Perchlorate Reduction and Applications. In Perchlorate: Environmental Occurrence, Interactions and Treatment; Gu, B., Coates, J. D., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2006; pp. 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girenko, D. V; Velichenko, A. B. Selection of the Optimal Cathode Material to Synthesize Medical Sodium Hypochlorite Solutions in a Membraneless Electrolyzer. Surface Engineering and Applied Electrochemistry 2018, 54(1), 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manivel, A.; Sivakumar, R.; Anandan, S.; Ashokkumar, M. Ultrasound-Assisted Synthesis of Hybrid Phosphomolybdate–Polybenzidine Containing Silver Nanoparticles for Electrocatalytic Detection of Chlorate, Bromate and Iodate Ions in Aqueous Solutions. Electrocatalysis 2012, 3, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, A. M.; Awad, M. I.; Ohsaka, T. Study of the Autocatalytic Chlorate–Triiodide Reaction in Acidic and Neutral Media. J Adv Res 2010, 1(3), 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, C. N.; Araujo, D. M.; Martinez-Huitle, C. A.; Rodrigo, M. A. Application of Advanced Oxidative Methods for Water Disinfection. Revista Virtual de Química 2015, 55, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Das, T. N. Reactivity and Role of SO₅˙− Radical in Aqueous Medium Chain Oxidation of Sulfite to Sulfate and Atmospheric Sulfuric Acid Generation. Journal of Physical Chemistry 2001, 105(40), 9142–9155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Tang, M.; Chen, C.; Chen, M.; Luo, K.; Xu, J.; Zhou, D.; Wu, F. Efficient Bacterial Inactivation by Transition Metal Catalyzed Auto-Oxidation of Sulfite. Environmental Science and Technology 2017, 51(21), 12663–12671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badea, G. E.; Aleya, L.; Mustatea, P.; Tit, D. M.; Endres, L; Bungau, S; Cioca, G. Chlorate Electrochemical Removal from Aqueous Media Based on a Possible Autocatalytic Mechanism. Polarization. polarization 2019, 23, 1oC. [Google Scholar]

- Qiangwei, L.; Lidong, W.; Yi, Z.; Yongliang, M.; Shuai, C.; Shuang, L.; Peiyao, X.; Jiming, H. Oxidation Rate of Magnesium Sulfite Catalyzed by Cobalt Ions. Environ Sci Technol 2014, 48(7), 4145–4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, J.; Tan, M.; Wang, Z.; Wu, M. Synergetic Transformations of Multiple Pollutants Driven by Cr(VI)–Sulfite Reactions. Environ Sci Technol 2015, 49(20), 12363–12371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, B.; Dong, H.; Sun, B.; Guan, X. Role of Ferrate (IV) and Ferrate (V) in Activating Ferrate (VI) by Calcium Sulfite for Enhanced Oxidation of Organic Contaminants. Environ Sci Technol 2018, 53(2), 894–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, J.; Feng, L.; Dong, H.; Zhao, Z.; Guan, X. Overlooked Role of Sulfur-Centered Radicals during Bromate Reduction by Sulfite. Environ Sci Technol 2019, 53(17), 10320–10328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.; Guan, X.; Fang, J.; Tratnyek, P. G. Activation of Manganese Oxidants with Bisulfite for Enhanced Oxidation of Organic Contaminants: The Involvement of Mn (III). Environ Sci Technol 2015, 49(20), 12414–12421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ma, J.; Liu, G.; Fang, J.; Yue, S.; Guan, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, X. Efficient Reductive Dechlorination of Monochloroacetic Acid by Sulfite/UV Process. Environ Sci Technol 2012, 46(13), 7342–7349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Peng, Y.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Wu, F.; Zhou, D. Metal-Free Electro-Activated Sulfite Process for As (III) Oxidation in Water Using Graphite Electrodes. Environ Sci Technol 2020, 54(16), 10261–10269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Shao, B.; Dong, H.; Guan, X. Simultaneous Removal of Chlorite and Coexisting Emerging Organic Contaminants by Sulfite: Kinetics and Mechanisms. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 463, 142429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, B. P.; Reinhard, M.; Schneider, W. F.; Schüth, C.; Shapley, J. R.; Strathmann, T. J.; Werth, C. J. Critical Review of Pd-Based Catalytic Treatment of Priority Contaminants in Water. Environmental Science and Technology 2012, 46, 3655–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, E.; Muránszky, G.; Kristály, F.; Fiser, B.; Farkas, L.; Viskolcz, B.; Vanyorek, L. Development of Palladium and Platinum Decorated Granulated Carbón Nanocomposites for Catalytic Chlorate Elimination. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23(18), 10514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plá-Hernandez, A.; Rey, F.; Palomares, A. E. Pt-Zeolites as Active Catalysts for the Removal of Chlorate in Water by Hydrogenation Reactions. Catal Today 2024, 429, 114461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, R. A.; Achenbach, I. A.; Coates, J. D. Reduction of (per)Chlorate by a Novel Organism Isolated from Paper Mill Waste. Environmental Microbiology 1999, 1(4), 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, J. D.; Michaelidou, U.; Bruce, R. A.; O’Connor, S. M.; Crespi, J. N.; Achenbach, L. A. Ubiquity and Diversity of Dissimilatory (per)Chlorate-Reducing Bacteria. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1999, 65, 5234–5241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, I. C.; Melnyk, R. A.; Engelbrektson, A.; Coates, J. D. Structure and Evolution of Chlorate Reduction Composite Transposons. mBio 2013, 2013, e00144-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolterink, A. F. W. M.; Schiltz, E.; Hagedoorn, P.-L.; Hagen, W. R.; Kengen, S. W. M.; Stams, A. J. M. Characterization of the Chlorate Reductase from Pseudomonas Chloritidismutans. J Bacteriol 2003, 185(10), 3210–3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, O.; Coates, J. D. Biotechnological Applications of Microbial (per) Chlorate Reduction. Microorganisms 2017, 5(4), 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, K. N.; Garcia-Segura, S.; Westerhoff, P.; Wong, M. S. Catalytic Converters for Water Treatment. Acc Chem Res 2019, 52(4), 906–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Rojas, F.; Muñoz, D.; Tapia, N.; Canales, C.; Vargas, I. T. Bioelectrochemical Chlorate Reduction by Dechloromonas Agitata CKB. Bioresour Technol 2020, 315, 123818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroon, A. G. M.; van Ginkel, C. G. Biological Reduction of Chlorate in a Gas-Lift Reactor Using Hydrogen as an Energy Source. J Environ Qual 2004, 33(6), 2026–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. P.; Logan, B. E. Sustained Perchlorate Degradation in an Autotrophic, Gas-Phase, Packed-Bed Bioreactor. Environ Sci Technol 2000, 34(14), 3018–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Kong, C.; Heo, J.; Yoon, Y.; Lee, H.; Her, N. Removal of Perchlorate Using Reverse Osmosis and Nanofiltration Membranes. Environmental Engineering Research 2012, 17(4), 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, W. P.; Blais, H. N.; O’Callaghan, T. F.; Hossain, M.; Moloney, M.; Danaher, M.; O’Connor, C.; Tobin, J. T. Application of Nanofiltration for the Removal of Chlorate from Skim Milk. Int Dairy J 2022, 128, 105321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Amy, G.; Cho, J.; Pellegrino, J. Systematic Bench-Scale Assessment of Perchlorate (ClO4−) Rejection Mechanisms by Nanofiltration and Ultrafiltration Membranes. Sep Sci Technol 2005, 39(9), 2105–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roquebert, V.; Booth, S.; Cushing, R. S.; Crozes, G.; Hansen, E. Electrodialysis Reversal (EDR) and Ion Exchange as Polishing Treatment for Perchlorate Treatment. Desalination 2000, 131(1–3), 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo, A. M. S.; Lopez-Peñalver, J. J.; Rivera-Utrilla, J.; Von Gunten, U.; Sánchez-Polo, M. Halide Removal from Waters by Silver Nanoparticles and Hydrogen Peroxide. Science of the Total Environment 2017, 607, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Li, Z. Q. Study on Reaction Equilibriums of Removing Chloride by Cuprous Chloride Precipitation. Hydrometall. China 2001, 3, 152–155. [Google Scholar]

- Polo, A. M. S.; Lopez-Peñalver, J. J.; Sánchez-Polo, M.; Rivera-Utrilla, J.; López-Ramón, M. V; Rozalén, M. Halide Removal from Water Using Silver Doped Magnetic-Microparticles. J Environ Manage 2020, 253, 109731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X. Chloride Ion Removal from Zinc Sulfate Aqueous Solution by Electrochemical Method. Hydrometallurgy 2013, 134, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Dou, W.; Kong, L.; Hu, X.; Wang, X. Removal of Chloride Ions from Strongly Acidic Wastewater Using Cu (0)/Cu (II): Efficiency Enhancement by UV Irradiation and the Mechanism for Chloride Ions Removal. Environ Sci Technol 2018, 53(1), 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Lei, X.; Westerhoff, P.; Zhang, X.; Yang, X. Reactivity of Chlorine Radicals (Cl• and Cl2•–) with Dissolved Organic Matter and the Formation of Chlorinated Byproducts. Environ Sci Technol 2020, 55(1), 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Wu, Z.; Shang, C.; Yao, B.; Hou, S.; Yang, X.; Song, W.; Fang, J. Radical Chemistry and Structural Relationships of PPCP Degradation by UV/Chlorine Treatment in Simulated Drinking Water. Environ Sci Technol 2017, 51(18), 10431–10439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilca, A. F.; Teodosiu, C.; Fiore, S.; Musteret, C. P. Emerging Disinfection Byproducts: A Review on Their Occurrence and Control in Drinking Water Treatment Processes. Chemosphere 2020, 259, 127476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanovski, V.; Claesson, P. M.; Hedberg, Y. S. Comparison of Different Surface Disinfection Treatments of Drinking Water Facilities from a Corrosion and Environmental Perspective. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2020, 27(11), 12704–12716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO. Environmental Management - Life Cycle Assessment - Principles and Framework; 2006.

- Mo, W.; Cornejo, P. K.; Malley, J. P.; Kane, T. E.; Collins, M. R. Life Cycle Environmental and Economic Implications of Small Drinking Water System Upgrades to Reduce Disinfection Byproducts. Water Res 2018, 143, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jachimowski, A; Nitkiewicz, T. Comparative Analysis of Selected Water Disinfection Technologies with the Use of Life Cycle Assessment. Archives of Environmental Protection 2019, 45, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, M. M.; Hawes, J. K.; Blatchley, E. R. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Water Disinfection Processes Applicable in Low-Income Settings. Environmental Science and Technology 2022, 56, 16336–16346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabet, H.; Moghaddam, S. S.; Ehteshami, M. A Comparative Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Analysis of Innovative Methods Employing Cutting-Edge Technology to Improve Sludge Reduction Directly in Wastewater Handling Units. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2023, 51, 103354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Rong, S.; Wang, R.; Yu, S. Recent Advances in Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Nonlinear Relationship Analysis and Process Control in Drinking Water Treatment: A Review. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 405, 126673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleato, N. M.; Legge, R. L.; Andrews, R. C. Neural Networks for Dimensionality Reduction of Fluorescence Spectra and Prediction of Drinking Water Disinfection By-Products. Water Res 2018, 136, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, Y. H.; Chen, S.; Chinn, C. J.; Mitch, W. A. Comparing the UV/Monochloramine and UV/Free Chlorine Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) to the UV/Hydrogen Peroxide AOP under Scenarios Relevant to Potable Reuse. Environmental Science and Technology 2017, 51, 13859–13868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishimoto, N. State of the Art of UV/Chlorine Advanced Oxidation Processes: Their Mechanism, Byproducts Formation, Process Variation, and Applications. J Water Environ Technol 2019, 17(5), 302–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Ji, H.; Qin, W.; Chen, C.; Wu, Z.; Guo, K.; Wei, W.; Guo, W.; Fang, J. Production of Reactive Species during UV Photolysis of Chlorite for the Transformation of Micropollutants in Simulated Drinking Water. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 470, 144076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Chew, Y. M. J.; Hofman, J. A. M. H.; Lutze, H. V; Wenk, J. UV-Induced Reactive Species Dynamics and Product Formation by Chlorite. Water Res 2024, 264, 122218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, S.; Wu, Y.; Sheng, D.; Bu, L.; Zhou, S. Insights into the Wavelength-Dependent Photolysis of Chlorite: Elimination of Carbamazepine and Formation of Chlorate. Chemosphere 2022, 288, 132505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disinfectant | Organohalogenic Disinfection Byproducts | Inorganic Disinfection Byproducts | Non-Halogenic Disinfection Byproducts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorine (Cl2) / Hypochlorous Acid (HOCl) | Trihalomethanes, halogenic acetic acids, haloacetonitriles, hydrated chlorine, chloropicrin, chlorophenol, N-chloramines, haloform, bromonitromethane | Chlorates (mainly from hypochlorite application) | Aldehydes, alkanes, benzene, carboxylic acids |

| Chlorine Dioxide (ClO2) | Haloacetonitriles, cyanogen chloride, organic chloramines, acids, chlorohydrins, haloketones | Chlorite, chlorate | Not known |

| Chloramines (NH2Cl, etc.) | Haloacetonitriles, cyanogen chloride, organic chloramines, acids, chlorohydrins, haloketones | Nitrite, nitrate, chlorate, hydrazine | Aldehydes, ketones |

| Ozone (O3) | Bromoform, monobromoacetic acid, dibromoacetic acid, dibromoacetone, cyanogen bromide | Chlorate, iodate, bromate, hydrogen peroxide, iodoacetic acid, iodobromoacetic acid, peroxides, ozonates | Aldehydes, ketones, ketoacids, carboxylic acids |

| Ultraviolet (UV) Rays | None | Nitrite, nitrate (from nitrate photolysis) | Aldehydes, organic acids |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2) | None | Peroxides, oxygen radicals | Aldehydes, organic acids |

| Peracetic Acid (PAA) | None | None | Carboxylic acids |

| By products | EPA (2003) | WHO (2004) | Europe (98/83/EC) | Italy (D. Lgs. 31/01) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| THMs | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.03 | |

| Chloroform | 0.2 | (0.15 until 11/08) | ||

| Bromoform | 0.1 | |||

| Dibromochloromethane | 0.1 | |||

| Dichlorobromomethane | 0.06 |

| Oxidant-Disinfectant | Oxidation Potential, V |

|---|---|

| Ozone | 2.07 |

| Hydrogen peroxide | 1.77 |

| Hypochlorous acid | 1.49 |

| Chlorine Dioxide | 1.28 |

| Monochloramine | 1.16 |

| Chlorine | Chlorine Dioxide | Chloramine | Ozone | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. Coli | 0.034–0.05 | 0.4–0.75 | 95–180 | 0.02 |

| Rotavirus | 0.01–0.05 | 0.2–2.1 | 3810–6480 | 0.006–0.05 |

| G. Lambia Cyst | 47–150 | - | - | 0.5–0.6 |

| G. Muris | 30–630 | 7.2–18.5 | 1400 | 1.8–2.0 |

| Parameter | Chlorine Dioxide (ClO2) | Ozone (O3) | Ultraviolet (UV) | Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2) | Peracetic Acid (PAA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobial efficacy | Broad-spectrum (bacteria, viruses, protozoa); effective against biofilms | Very high; rapidly inactivates most pathogens | Effective for bacteria and viruses; limited for protozoa and turbid water | Moderate; often used in combination with other agents | Highly effective against a broad spectrum of microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and spores. |

| Operational costs | Moderate; on-site generation required | High; energy-intensive, complex systems | Moderate; dependent on water quality and lamp maintenance | Variable; combined use increases total costs | Generally higher than chlorine or chlorine dioxide but can be cost-effective in certain applications due to its effectiveness at lower concentrations. |

| Environmental footprint | Relatively low; by-products degrade over time | Potential bromate risk; ozone is a greenhouse gas if released | Minimal; no chemical residue | Low; breaks down into non-toxic compounds | Biodegradable and breaks down into acetic acid and water, with minimal long-term environmental impact when used properly. |

| Application notes | Stable across wide pH range; does not react with ammonia | Must be generated in situ; unstable | Effectiveness reduced by turbidity and suspended solids | Sensitive to light and heat; used in advanced oxidation processes | Often used in food processing, water treatment, and sanitation; effective in both cold and hot water applications; requires careful handling due to its corrosive nature. |

| Criterion | Score 1 (Optimal) | Score 5 (Least Favorable) |

|---|---|---|

| Operational Safety | No corrosive agents, no gas release | Toxic reagents (Cl2), exothermic risks, strong acids |

| Environmental Impact | Low emissions, low energy, benign by-products | High waste load, VOCs, persistent by-products |

| By-product Control | Minimal ClO2-, ClO3-, ClO4- | High or unstable by-product formation |

| Cost Efficiency | Low-cost reagents, minimal system complexity | Expensive inputs, intensive infrastructure |

| Scalability | Modular, adaptable to multiple scales | Suitable only for large, fixed systems |

| Regulatory Compliance | Intrinsically within legal thresholds | Exceeds MCLs without further treatment |

| Cost (Tech Matrix) | Widely available, low-cost chemicals | Specialized or costly reagents |

| By-products (Tech Matrix) | Low reactivity with NOM, minimal secondary species | Persistent or hazardous residuals |

| Operating Temperature | Ambient (20–30°C) | High (>50°C) |

| Operating Pressure | Atmospheric | Requires pressurization |

| Acidic Conditions / pH | Neutral to mildly acidic (pH > 4) | Highly acidic (pH < 2), corrosive |

| Chemical Efficiency | >90% ClO₂ yield, low side products | Low conversion, unstable intermediates |

| Technology | Process condition | Reducing agent | ClO2 by-product | Process by-product |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVP-LITE® | Vacuum | Methanol | Formic acid | Sodium Sulfate |

| SVP-SCW | Vacuum | Methanol | Formic acid | Sodium Sulfate |

| SVP-HP | Vacuum | Hydrogen Peroxide | Oxygen | Sodium Sulfate |

| HP-A® | Atmospheric | Hydrogen Peroxide | Oxygen | Sodium Sulfate |

| Technology / Process | Operational Safety | Targeted By-Products | Mechanism | Operational Complexity | Removal Efficiency | Typical Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH and Reagent Optimization | High | Chlorite, Chlorate, Perchlorate | Controls stoichiometry and pH to prevent side reactions | Low | Moderate | ClO2 generation in municipal treatment systems |

| Granular Activated Carbon (GAC) Adsorption | Medium | Chlorite, Chlorate | Adsorption + catalytic surface reduction (enhanced with modified GAC) | Medium | High (especially modified GAC) | Post-treatment for potable water |

| Ferrous Iron (Fe2+) Reduction | High | Chlorite | Direct chemical reduction to chloride | Low | High | Integrated with coagulation in drinking water treatment |

| Electrochemical Systems | Variable (depending on design) | Chlorate, Perchlorate | Cathodic reduction via high surface area electrodes | Medium–High | High | Decentralized or high-tech treatment facilities |

| Advanced Oxidation/Reduction Processes (AOPs/ARPs) | Medium | Chlorate, Chlorite | Radical generation (SO4·-, OH·, etc.) for selective degradation | High | Very High | Industrial effluents, complex wastewater |

| Heterogeneous Catalysis (Pt/Pd on zeolites) | High | Chlorate | Catalytic reduction via proton-coupled electron transfer | Medium | Very High (>99%) | Advanced municipal and industrial treatment systems |

| Anaerobic Biological Treatment | High | Chlorate, Perchlorate | Microbial respiration (e.g., Dechloromonas) | Medium | High (but slow kinetics) | Groundwater remediation, agricultural runoff |

| Membrane Techniques (RO, NF, ED) | High | Chlorite, Chlorate | Physical separation using semi-permeable membranes | High | Very High (>90%) | Ultrapure water, pharmaceutical or high-end applications |

| Chemical Precipitation (AgCl, CuCl) | Medium | Chloride | Formation of insoluble salts under controlled chemical conditions | High | High (niche efficiency) | Point-of-use systems, lab-scale or experimental processes |

| ClO2 + Ozone Combination | Medium | Reduced Chlorite, but increased Chlorate | O3 oxidizes ClO2-, regenerating ClO2 | Medium | Moderate | Surface waters with high organic content |

| Integrated Strategy | Combined Components | Synergistic Benefit | Application Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| ClO2 + GAC + UV/Cl₂ AOP | ClO2 for disinfection, GAC for DBP removal, UV/ Cl2 for residuals | Reduces chlorite + chlorate + organic DBPs | Surface water, high NOM content |

| ClO2 pre-oxidation + Fe2+ dosing + filtration | Pre-disinfection + chemical reduction + particle removal | Enhanced pathogen control + DBP mitigation | Drinking water with moderate turbidity |

| Electrochemical ClO2 generation + membrane filtration | On-site ClO2 + NF/RO for polishing | Residual control + high-quality effluent | Industrial or pharmaceutical water production |

| Bioreactor + ClO2 residual disinfection | Biological reduction of DBPs + final disinfection | Reduces perchlorate/chlorate + ensures microbial safety | Decentralized systems, groundwater reuse |

| PS- ClO2 hybrid + real-time monitoring | ClO2 + activated persulfate + automated controls | Optimized dosing, minimized DBP formation | Smart water networks, energy-intensive facilities |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).