Submitted:

23 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

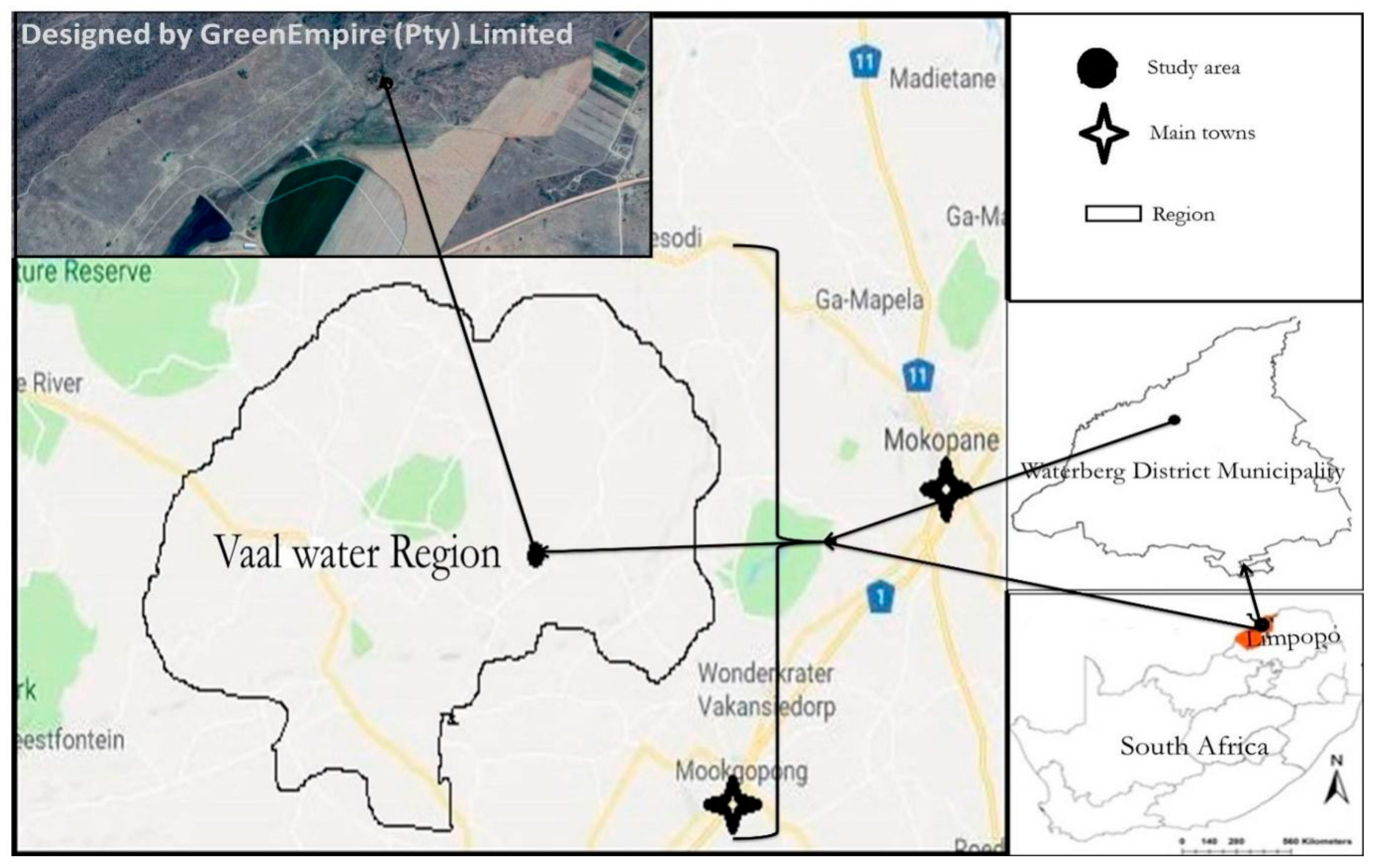

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Species Selection

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

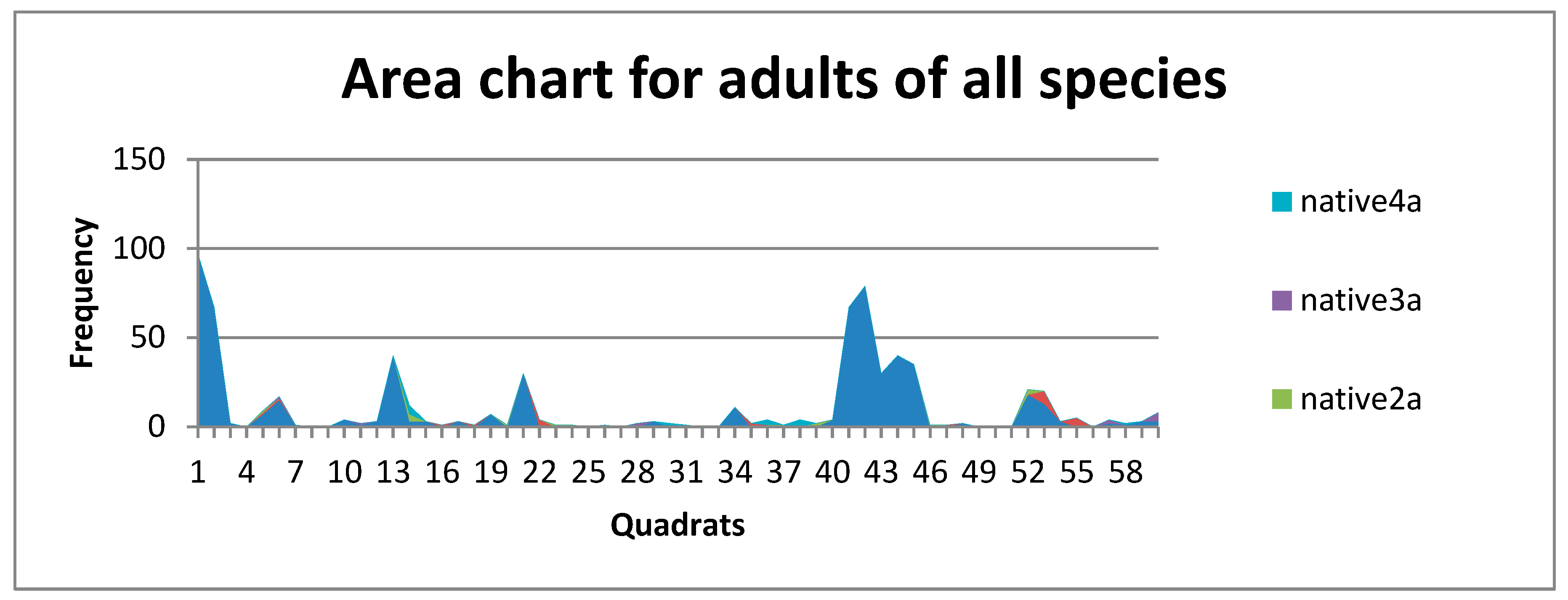

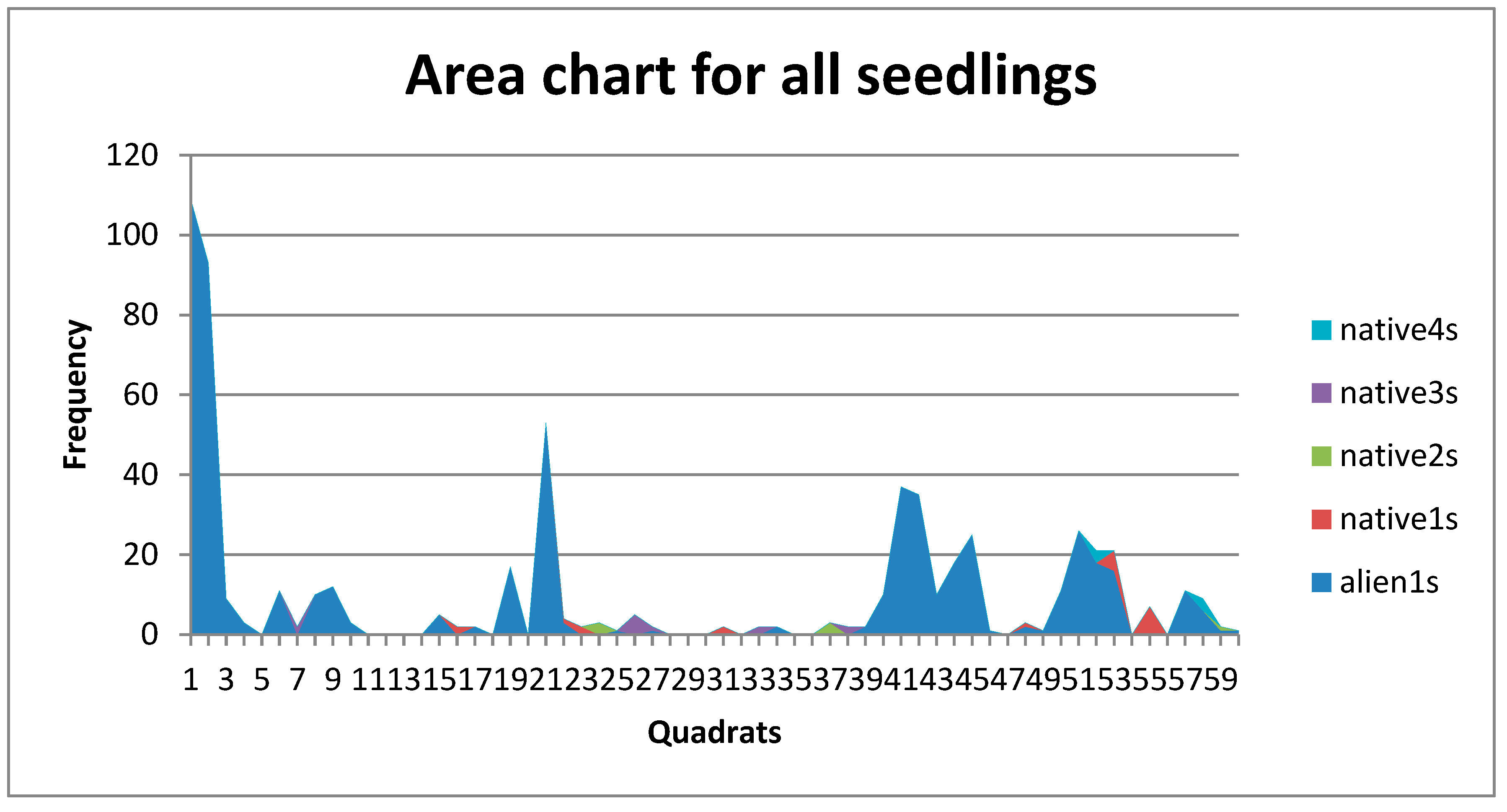

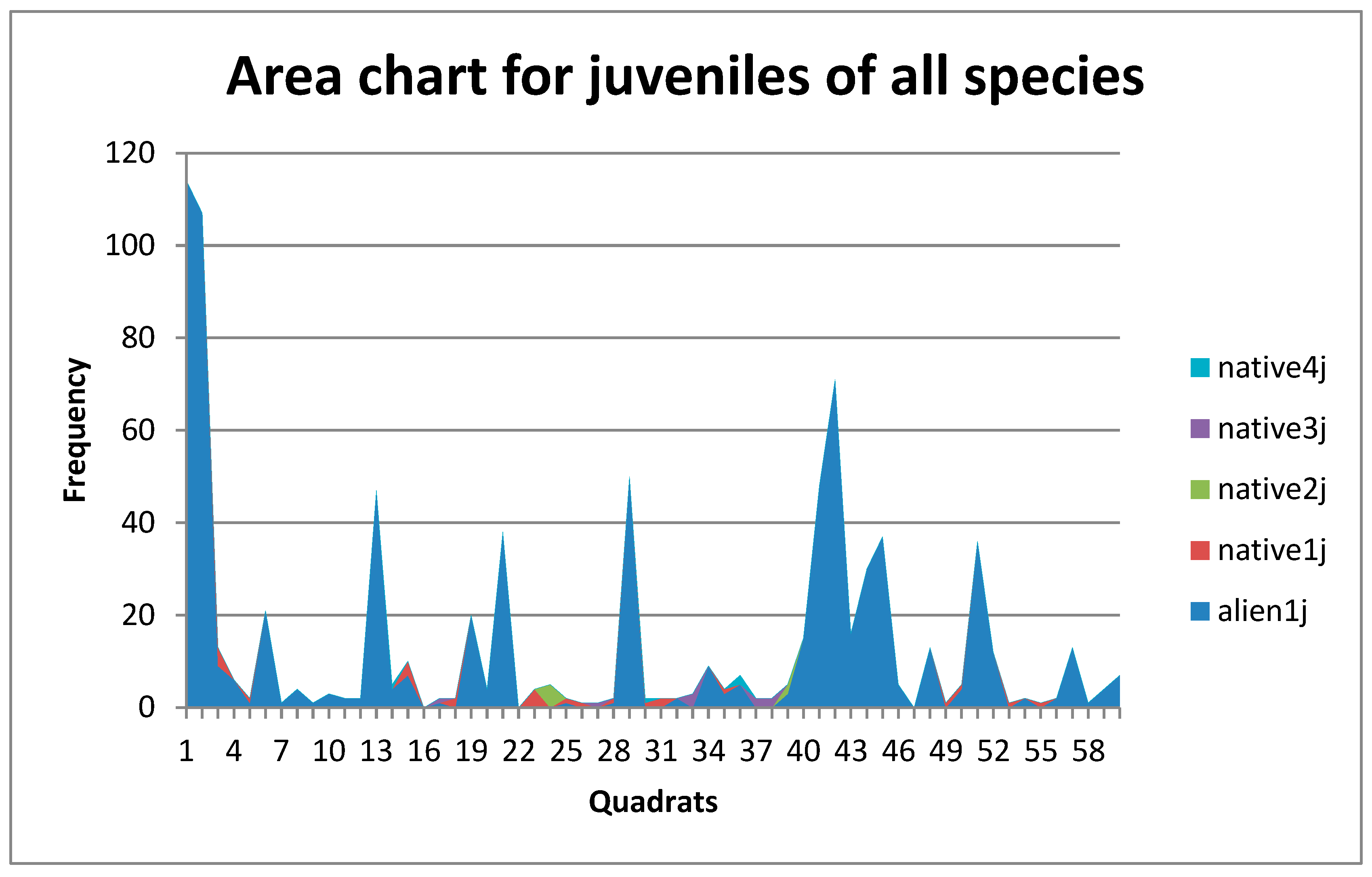

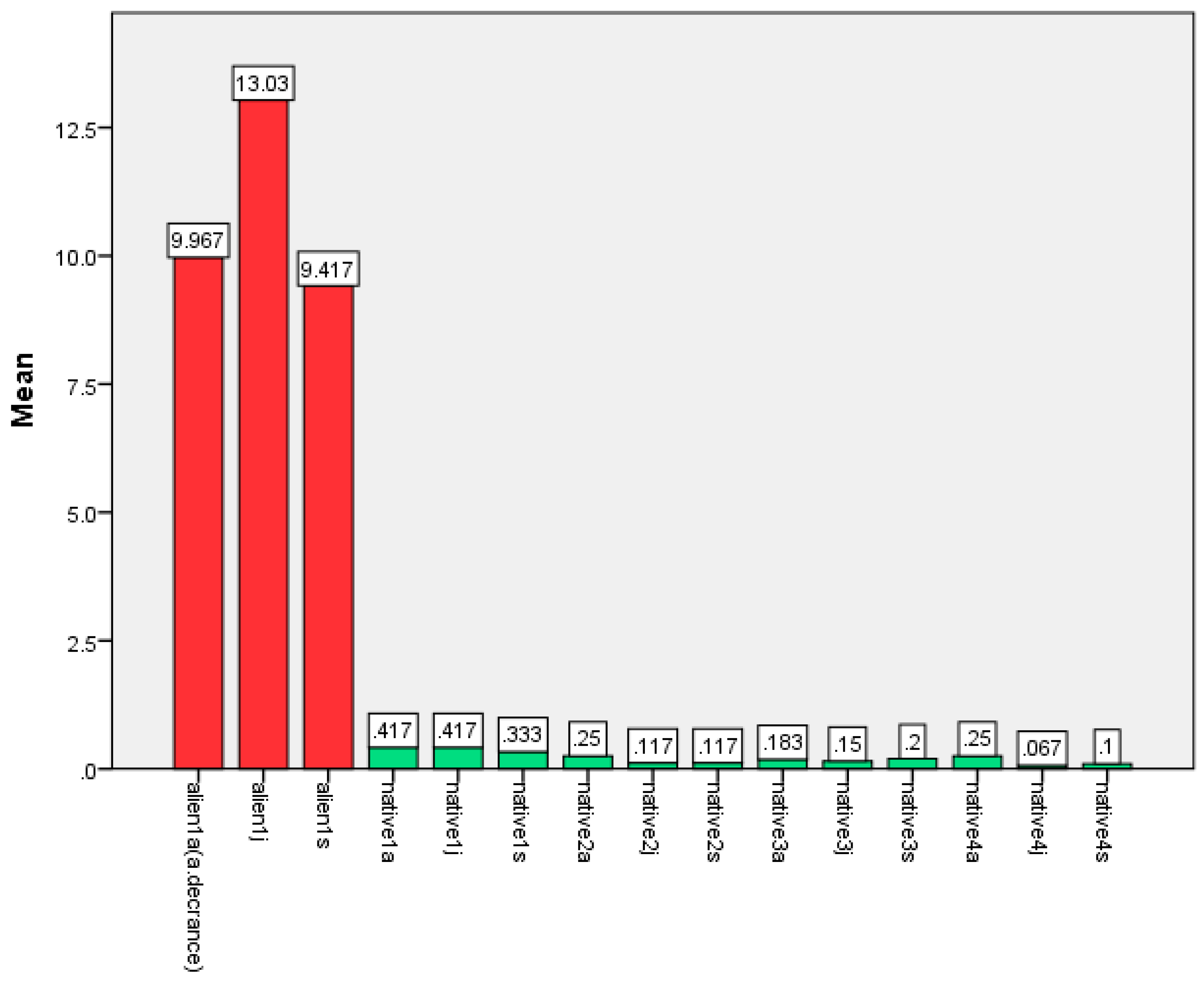

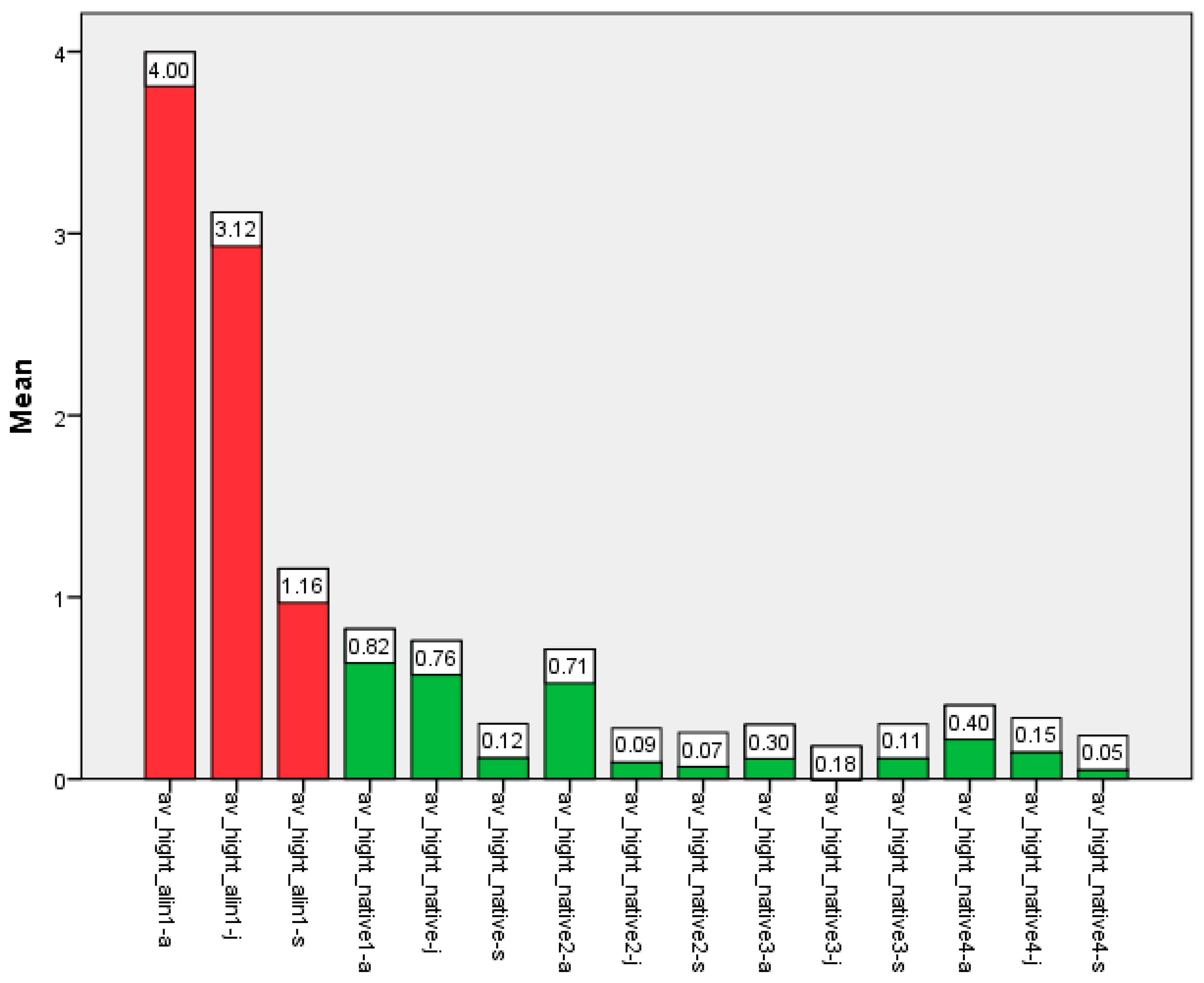

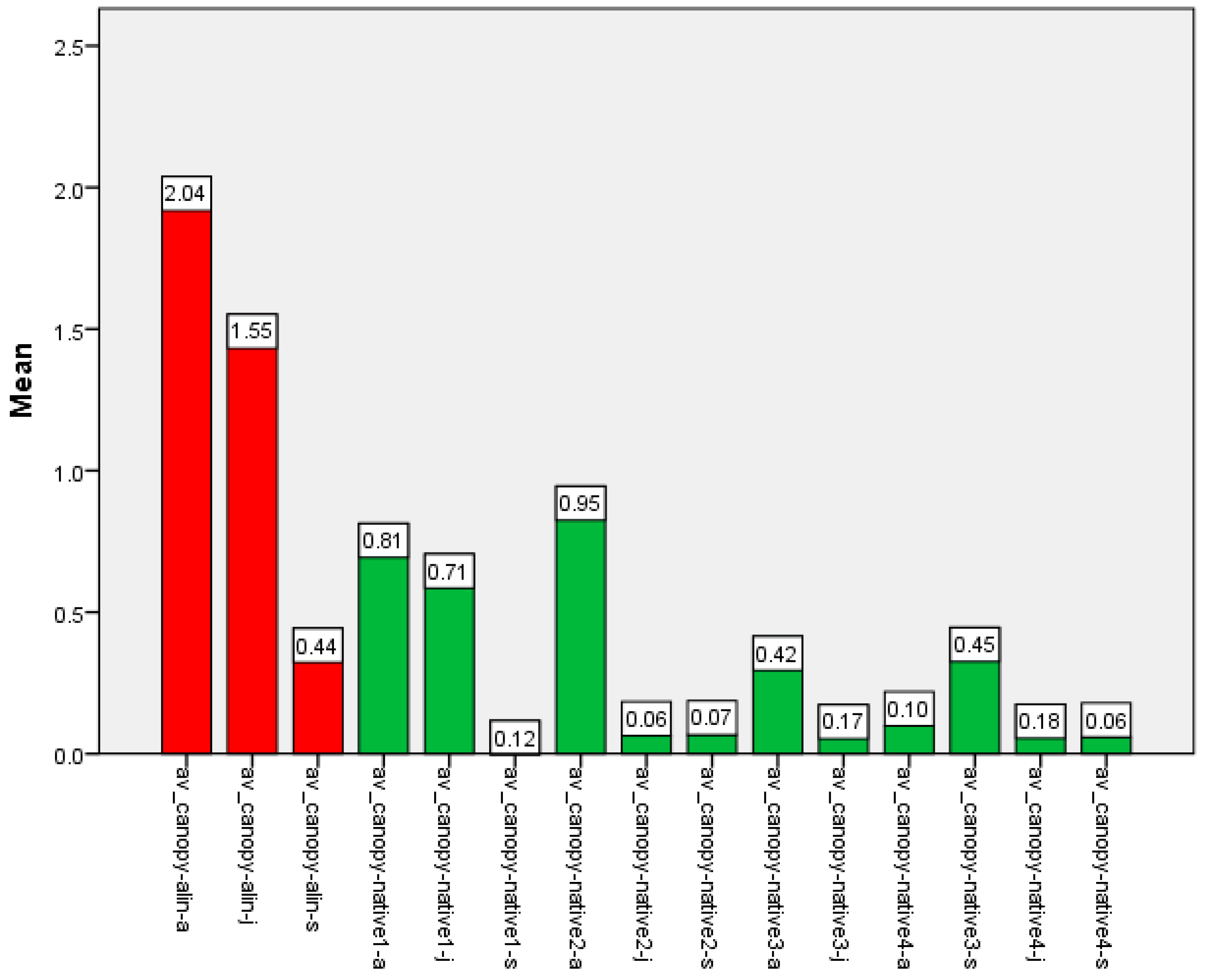

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects on Water Levels of the Rivers

4.2. Propagation Methods

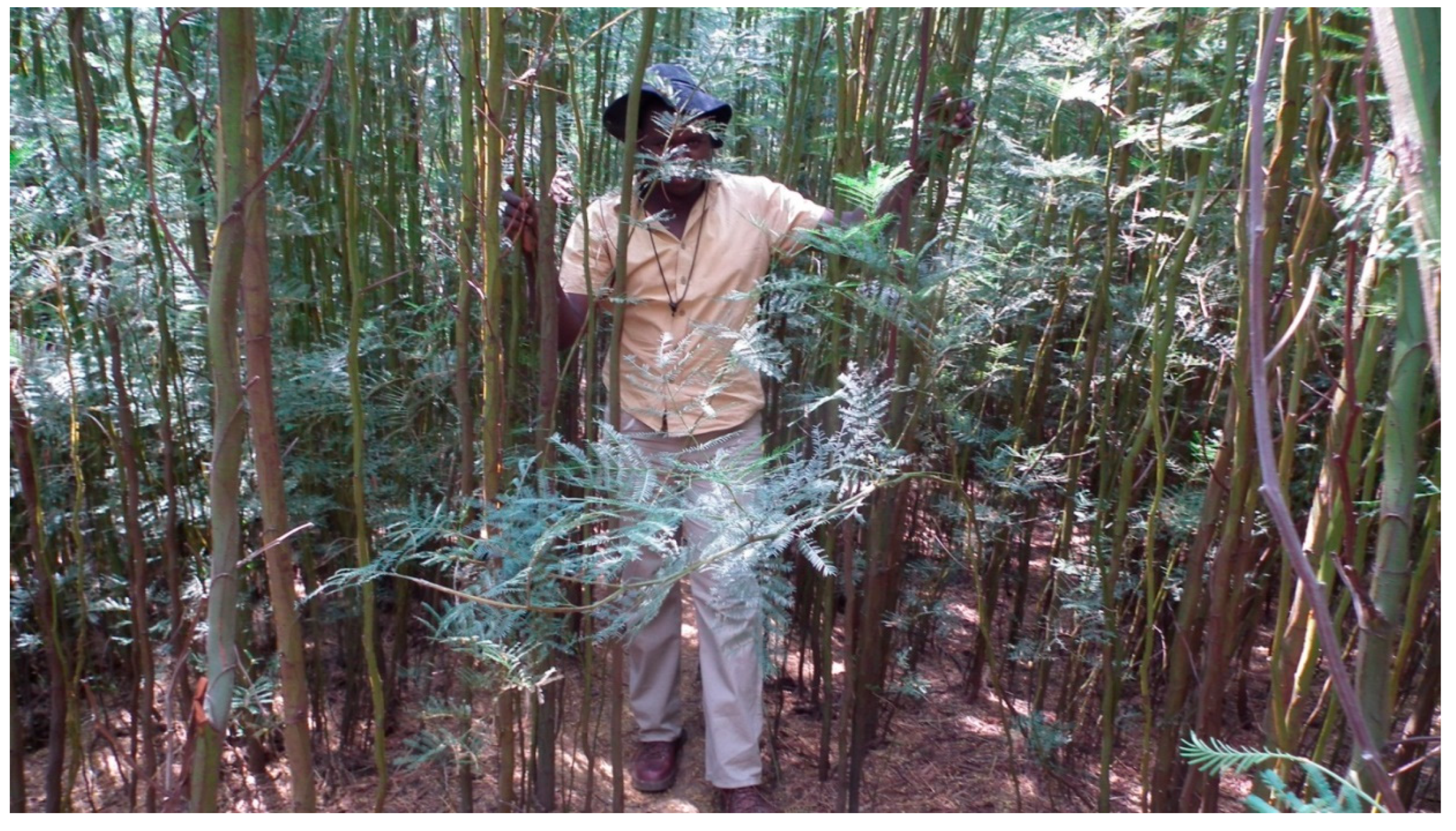

4.3. Leaf Type and Flowers Found in Acacia decurrens

4.4. Seed Dispersal

4.5. The Associations and Interactions of Acacia decurrens and the Native Species

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

References

- Mayfield, A.E. , Seybold, S.J., Haag, W.R., Johnson, M.T., Kerns, B.K., Kilgo, J.C., Larkin, D.J., Lucardi, R.D., Moltzan, B.D., Pearson, D.E. and Rothlisberger, J.D., 2021. Impacts of invasive species in terrestrial and aquatic systems in the United States. Invasive species in forests and rangelands of the United States: A comprehensive science synthesis for the United States forest sector, pp.5-39.

- Clout, M.N. and Veitch, C.R., 2002. Turning the tide of biological invasion: The potential for eradicating invasive species. Pages 1-3 in C R Veitch and M N Clout, editors. Turning the tide: The eradication of invasive species. World Conservation Union Species Survival Commission, Invasive Species Specialist Group, Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- Pearce, F. , 2016. The new wild: why invasive species will be nature's salvation. Beacon press.

- Gorgens, A.H.M. , and van Wilgen, B.W., 2004. Invasive alien plants and water resources in South Africa: Current understanding predictive ability and research challenges. South African Journal of Science. 100: 27–33.

- Samways, M.J. and Taylor, S.T., 2004. Impacts of invasive plants on red-listed South African dragonflies (Odonata) South African Journal of Science 100: 78 – 80.

- Richardson, D.M. and van Wilgen, B.W., 2004. Invasive alien plants in South Africa: How well do we understand the ecological impacts? South African Journal of Science. 100: 45 – 52.

- Myers, N. , Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C.G., da Fonseca, G.A.B. and Kent, J., 2000. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403: 853 – 858.

- Modiba, R.V. , Joseph, G.S., Seymour, C.L., Fouché, P. and Foord, S.H., 2017. Restoration of riparian systems through clearing of invasive plant species improves functional diversity of Odonate assemblages. Biological conservation, 214, pp.46-54.

- Tallamy, D.W. , 2004. Do alien plants reduce insect biomass? Conservation Biology 18: 1689 - 1692.

- Pyšek, P. , Hulme, P.E., Simberloff, D., Bacher, S., Blackburn, T.M., Carlton, J.T., Dawson, W., Essl, F., Foxcroft, L.C., Genovesi, P. and Jeschke, J.M., 2020. Scientists' warning on invasive alien species. Biological Reviews, 95(6), pp.1511-1534.

- Cassey, P. , Blackburn, T.M., Duncan, R.P. and Chown, S.L., 2005. Concerning invasive species: reply to Brown and Sax. Austral Ecology, 30(4), pp.475-480.

- Chesson, P. , 2012. Species competition and predation. In Ecological systems: Selected entries from the encyclopedia of sustainability science and technology (pp. 223-256). New York, NY: Springer New York.

- Huenneke, L. , Hamburg, S., Koide, R., Mooney, H. and Vitousek, P., 1990. Effects of soil resources on plant invasion and community structure in California (USA) serpentine grassland” Ecology (Ecology, Vol. 71, No. 2) 71 (2): 478 - 491.

- FAO., 2000b. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2000. Rome. Available at: www.fao.org/DOCREP/004/Y1997E/y1997e00.HTM.

- Rai, R.K. , Shrestha, L., Joshi, S. and Clements, D.R., 2022. Biotic and economic impacts of plant invasions. In Global plant invasions (pp. 301-315). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- FAO., 2000a. Alien species harmful to North American forests. Document to the twentieth session of the North American Forest Commission (NAFC), St. Andrews, New Bruinswick, Canada, 12-16 June 2000. Rome. Available at: www.fao.org/docrep/meeting/X7000E.htm.

- Loehle, C. , 2003. Competitive displacement of trees in response to environmental change or introduction of exotics. Environmental Management 32(1): 106 - 115.

- Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). 2003.The ecological and socio-economic impact of invasive alien species on island ecosystems. Document to the ninth meeting of the Subsidiary Body on Scientific, Technical and Technological Advice, Montreal, Canada, 10 - 14 www.biodiv.org/doc/ref/alien/ias-inland-en.pdf.

- McNeely, J.A. , Mooney, H.A., Neville, L.E., Schei, P. and Waage, J.K., 2001. A global strategy on invasive alien species. Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK, World Conservation Union (IUCN).

- Eriksen, T.H. , 2021. The loss of diversity in the Anthropocene biological and cultural dimensions. Frontiers in Political Science, 3, p.743610.

- Simberloff, D. , 2013. Invasive species: what everyone needs to know. OUP Us.

- Le Maitre, D. , Görgens, A., Howard, G. and Walker, N., 2019. Impacts of alien plant invasions on water resources and yields from the Western Cape Water Supply System (WCWSS). Water SA. 45(4), pp.568-579.

- Hardy, N.G., Kuebbing, S.E., Duguid, M.C., Ashton, M.S., Sheban, K.C., Inman, S.E. and Martin, M.P., 2025. Non-native invasive plants in tropical dry forests: a global review of presence, impacts, and management. Restoration Ecology, 33(1), p.e14288.

- Killian, S. and McMichael., 2004. The human allergens of mesquite (Prosopis Juliflora). Clinical and Molecular Allergy, 2(1): 8. Available at: www.clinicalmolecularallergy.com/content/2/18.

- Mullen, G.R. and Zaspel, J.M., 2019. Moths and butterflies (Lepidoptera). In Medical and veterinary entomology (pp. 439-458). Academic Press.

- Van Wilgen, B.W. , Richardson, D.M., le Maitre, D.C., Marais, C. and Magadlela, D., 2001. The economic consequences of alien plant invasions: examples of impacts and approaches to sustainable management in South Africa. Environment, Development and Sustainability 3: 145 - 168.

- Cowling, R.M. , Pressey, R.L., Lombard, A.T., Heijnis, C.E., Richardson, D.M. and Cole, N., 1999. Framework for a conservation plan for the cape Floristic Region. Institute for Plant Conservation, University of Cape Town.

- Cock, M.J.W. , 2003. Biosecurity and forests: an introduction with particular emphasis on forest pests. Forest Health and Biosecurity Working Paper FBS/2E. Rome, FAO (unpublished). Available at: www.fao.org/DOCREP/006/j1467/j1467E00.HTM.

- Schulz, A.N. , Lucardi, R.D. and Marsico, T.D., 2019. Successful invasions and failed biocontrol: The role of antagonistic species interactions. BioScience, 69(9), pp.711-724.

- Crawley, M.J. , 1986. The population biology of invaders. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B314: 711 - 731.

- Richardson, D.M. and Rejmanek, M., 2004. Conifers as invasive alien a global survey and predictive framework. Diversity and Distributions 10:321 - 331.

- Le Maitre, D.C., van Wilgen, C., Chapman, R.A., and Mckelly, D.H., 1996. Invasive plants and water resources in Western Cape Province, South Africa: modelling the consequences of lack of management. Journal of Applied Ecology 33: 161 - 172.

| Species | Chi-squared | p |

| Alien adult Native 1 adult |

79.329 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 1 juvenile |

33.944 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 1 seedling |

74.239 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 2 adult |

75.405 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 2 juvenile |

2.365 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 2 seedling |

8.910 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 3 adult |

32.519 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 3 juvenile |

6.555 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 3 seedling |

7.584 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 4 adult |

37.714 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 4 juvenile |

17.096 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 4 seedling |

36.724 | ** |

| Alien juvenile Native 1 adult |

47.675 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 1 juvenile |

63.756 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 1 seedling |

30.814 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 2 adult |

99.393 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 2 juvenile |

22.091 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 2 seedling |

16.816 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 3 adult |

8.387 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 3 juvenile |

13.203 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 3 seedling |

11.149 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 4 adult |

53.809 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 4 juvenile |

35.520 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 4 seedling |

33.399 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 1 adult |

90.926 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 1 juvenile |

105.564 | ** |

| Alien seedling Native 1 seedling |

81.295 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 2 adult |

50.709 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 2 juvenile |

15.537 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 2 seedling |

11.795 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 3 adult |

28.657 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 3 juvenile |

14.801 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 3 seedling |

14.629 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 4 adult |

65.538 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 4 juvenile |

4.130 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 4 seedling |

44.483 | ** |

| Species | X2 | P |

| Alien adult Native 1 adult |

127.811 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 1 juvenile |

313.448 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 1 seedling |

65.747 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 2 adult |

186.815 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 2 juvenile |

2.212 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 2 seedling |

62.178 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 3 adult |

181.034 | ** |

| Alien adult Native 3 juvenile |

33.969 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 3 seedling |

5.831 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 4 adult |

242.069 | ** |

| Alien adult Native a juvenile |

121.053 | ** |

| Alien adult Native 4 seedling |

120.000 | ** |

| Alien juvenile Native 1 adult |

127.003 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 1 juvenile |

272.500 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 1 seedling |

18.333 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 2 adult |

297.010 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 2 juvenile |

62.780 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 2 seedling |

35.132 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 3 adult |

128.750 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 3 juvenile |

71.727 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 3 seedling |

71.727 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 4 adult |

184.444 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 4 juvenile |

122.763 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 4 seedling |

89.483 | * |

| Alien seedling Native 1 adult |

192.539 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 1 juvenile |

300.100 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 1 seedling |

125.867 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 2 adult |

158.447 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 2 juvenile |

61.407 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 2 seedling |

62.863 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 3 adult |

61.757 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 3 juvenile |

124.320 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 3 seedling |

124.320 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 4 adult |

95.311 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 4 juvenile |

4.421 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 4 seedling |

120.000 | ** |

| Species | X2 | P |

| Alien adult Native 1 adult |

128.960 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 1 juvenile |

252.711 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 1 seedling |

125.283 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 2 adult |

186.353 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 2 juvenile |

2.069 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 2 seedling |

62.035 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 3 adult |

150.429 | ** |

| Alien adult Native 3 juvenile |

64.218 | ns |

| Alien adult Native 3 seedling |

181.964 | * |

| Alien adult Native 4 adult |

5.455 | ns |

| Alien adult Native a juvenile |

120.982 | ** |

| Alien adult Native 4 seedling |

120.000 | ** |

| Alien juvenile Native 1 adult |

112.553 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 1 juvenile |

305.922 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 1 seedling |

76.781 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 2 adult |

235.721 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 2 juvenile |

16.780 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 2 seedling |

65.201 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 3 adult |

133.125 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 3 juvenile |

70.781 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 3 seedling |

185.134 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 4 adult |

30.053 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 4 juvenile |

122.539 | ns |

| Alien juvenile Native 4 seedling |

120.000 | ** |

| Alien seedling Native 1 adult |

101.215 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 1 juvenile |

301.368 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 1 seedling |

154.833 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 2 adult |

157.828 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 2 juvenile |

30.796 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 2 seedling |

21.970 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 3 adult |

81.923 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 3 juvenile |

62.937 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 3 seedling |

24.811 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 4 adult |

62.937 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 4 juvenile |

4.130 | ns |

| Alien seedling Native 4 seedling |

79.310 | ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).