1. Introduction

Sex hormones—primarily estrogen, progesterone, and androgens—are integral to the regulation of various physiological processes in the human body [

1]: beyond their well-documented roles in reproductive and metabolic functions, emerging evidence underscores their significant influence on connective tissues [

2].

Recent studies have also demonstrated that sex hormones directly influence the composition and mechanical properties of fasciae [

3]. Research indicates that human fascia express estrogen receptor-alpha (ERα) and relaxin receptor 1 (RXFP1), suggesting a direct hormonal effect on fascial cells [

4]. These receptors are predominantly localized in fibroblasts, with reduced expression observed in postmenopausal women compared to premenopausal counterparts, highlighting a potential link between hormonal fluctuations and fascial tissue characteristics [

4]. In vitro studies have further elucidated this relationship: exposure of fascial fibroblasts to β-estradiol resulted in significant alterations in extracellular matrix (ECM) components. Collagen-I expression decreased from 6% in the follicular phase to 1.9% in the periovulatory phase, while collagen-III and fibrillin levels increased, reflecting a shift towards a more elastic ECM composition during ovulation [

3]. These changes are consistent with the physiological requirements during periods of increased joint mobility, such as ovulation and pregnancy. The opposite situation happens during menopause, in which the fascia becomes more stiff and less elastic. Moreover, the addition of relaxin-1 consistently promoted a more antifibrotic ECM profile (1.7% of collagen-I) [

3].

A study employing shear wave elastography revealed that non-users of hormonal contraceptives exhibited greater stiffness in the thoracolumbar fascia compared to users, suggesting that hormonal contraceptives may influence fascial mechanical properties, including stiffness and elasticity [

5]. Additionally, the use of aromatase inhibitors, which lower estrogen levels, has been associated with increased joint pain and musculoskeletal discomfort, further implicating estrogen's role in maintaining connective tissue integrity [

6]. In general, musculoskeletal pain and fibrosis are common adverse effects encountered in patients receiving antihormonal treatments, like tamoxifen for breast cancer patients [

7,

8].

Testosterone, the primary male sex hormone, also influence connective tissues. It plays a crucial role in the development and maintenance of male secondary sexual characteristics, as well as muscle mass and bone density [

9]. While the direct effects of testosterone on human fascia were never studied, its effects on connective tissue remodeling and ECM production are deeply demonstrated: a study demonstrated that testosterone treatment reduced the expression of collagen types I and III in vascular smooth muscle cells through the Gas6/Axl signaling pathway [

10]. This pathway leads to decreased collagen hyperexpression synthesis age-related and decreased matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) activity. The inhibition of MMP-2 activity by testosterone contributes to the attenuation of ECM remodeling, which is crucial for maintaining tissue integrity and preventing fibrosis [

10]. Conversely, testosterone deficiency, common in aging men, is associated with increased incidence of musculoskeletal disorders, including sarcopenia and osteoarthritis [

11,

12].

In cardiac fibroblasts, physiological levels of testosterone have been shown to attenuate profibrotic activities: specifically, testosterone enhances nitic oxide (NO) production, which in turn decreases calcium entry through the inositol trisphosphate (IP3) receptor, leading to reduced activation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII). This cascade results in diminished collagen synthesis and overall attenuation of fibrosis in cardiac tissue [

13]. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that physiological levels of testosterone attenuates the phosphorylation of Akt and Smad2/3, mediated by the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and angiotensin II (Ang II) respectively, thereby reducing cardiac fibroblast activation, migration, and collagen production and potentially contributing to beneficial effects in heart failure [

14]. In the dermal fibroblats, androgens can suppress collagen deposition and modulate inflammatory responses, thereby affecting the ECM's composition during the healing process [

15]. Collectively, these findings underscore the multifaceted role of testosterone in regulating ECM remodeling across different tissues, highlighting its potential therapeutic implications in conditions characterized by fibrosis.

The biological effects exterted by testosterone is mediated by the androgen receptor (AR): once bound, it can either act directly or be converted via the enzyme 5α-reductase to dihydrotestosterone (DHT), which has a 2–3 times greater affinity for AR and produces more potent biological effects, especially in non-gonadal tissues: it contributes to differentiation of chondrocytes and maturation of connective tissues during puberty [

16]. Furthermore, DHT influences ECM remodeling by modulating the synthesis of collagen and proteoglycans, as well as the activity of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their inhibitors (TIMPs). These actions are crucial for tissue homeostasis and repair processes [

17]. In the context of pathological conditions such as prostatic fibrosis and desmoid-type fibromatosis, DHT has been shown to promote fibrotic responses in connective tissues through androgen-dependent mechanisms [

18].

Collectively, these findings underscore the multifaceted role of DHT in connective tissue biology. Furthermore, several authors have demonstrated that male and female chondrocytes exhibit differential responsiveness to testosterone: specifically, female chondrocytes display a higher aromatase activity in favor of the conversion of testosterone into estradiol rather than DHT, whereas in male chondrocytes, DHT mediates sex-specific rapid membrane effects in male growth plate chondrocytes, that are absent in female cells [

19,

20]. These evidence highlight the importance of a better comprehension of sex differences in connective tissue homeostasis. A deeper comprehension of how sex hormones fluctuations modulate fascial and connective tissue properties is crucial for elucidating gender differences in musculoskeletal health, in particular in women [

21]: for example, variations in fascial stiffness and collagen composition during the menstrual cycle may influence injury risk and recovery outcomes. Moreover, hormonal therapies, including hormone replacement therapy and oral contraceptives, may offer therapeutic avenues to modulate fascial properties and alleviate associated symptoms.

Men typically exhibit greater fascial thickness and tissue stiffness compared to women, likely due to higher basal testosterone levels and increased androgen receptor activity. This sexual dimorphism in connective tissue properties may have biomechanical implications; for instance, males might possess enhanced force transmission capacity through fascia, but potentially reduced elasticity, which could influence susceptibility to certain musculoskeletal injuries or pain syndromes [

17]. Furthermore, age-related androgen decline (i.e., andropause) is associated with increased risk of muscle wasting and joint degeneration, suggesting a protective, maintenance role for testosterone in connective tissue homeostasis [

12].

On the other hand, testosterone in women, though present in lower concentrations compared to men, contributes to the ECM regulation: for instance, studies have shown that testosterone administration can induce muscle fiber hypertrophy and improve capillarization in young women, particularly affecting type II muscle fibers [

22]. Furthermore, testosterone inhibits the production of matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) in human endometrial stromal cells, suggesting a role in reducing collagen degradation [

23].

However, the effects of testosterone are not uniform across all tissues. In the vascular system, for example, testosterone's influence on endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activation differs between men and women [

24]. In males, it promotes eNOS activation and NO release via androgen receptor-mediated mechanisms, contributing to vascular relaxation and homeostasis. In contrast, in females, the response to testosterone is more variable and appears to depend on the local hormonal environment, including estrogen levels, which may modulate androgen receptor sensitivity or downstream signaling. These differences contribute to sex-specific vascular responses, and may partially explain the divergent cardiovascular effects observed between men and women in both physiological and pathological contexts [

24].

Collectively, these findings underscore the importance of testosterone in men and women's health, particularly concerning connective tissue integrity and musculoskeletal function. Understanding the nuanced roles of testosterone can inform therapeutic strategies aimed at addressing musculoskeletal disorders and age-related changes in connective tissue.

In this work, we propose to understand if the androgen receptor is expressed in human deep fascia and how the DHT, a potent steroid agonist for the androgen receptor can influence ECM production by the fascial fibroblast. By this way we can understand if male hormones affect the fascia, with the aim to elucidate better gender differences in musculoskeletal health. Continued research is essential to further elucidate how sex hormones affect fasciae and translate findings into effective clinical strategies for managing connective tissue-related disorders.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

This study was approved by the Ethic Committee of the Hospital of University of Padova (approval no. AOP2648) whose ethical regulations regarding research conducted on human tissues were carefully followed. Written informed consent was obtained from all the volunteer donors.

Samples of fascia approximately 0.5cm × 0.5cm were collected from 4 volunteers, 2 males and 2 females patients, average age 64 (range 50-76 y), who were undergoing elective surgical procedures at the Orthopedic Clinic of Padua University. The samples were collected from two fascia lata of the thigh and two thoracolumbar fascia and transported to the laboratory in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) within a few hours of their collection and used fresh for cell isolation or formalin-fixed for histology.

2.2. Cell Isolation and Culture

Fresh samples were washed in PBS containing 1% penicillin and streptomycin, within a few hours of collection, then cut with a surgical scalpel and transferred to tissue flasks with DMEM 1 g/L glucose, 10% FBS, and 1% penicillin–streptomycin antibiotic. Isolated fibroblasts were characterized by anti-Fibroblast Surface Protein (1B10) antibody as previously described in one of our previous works [

25]. Cell cultures were maintained at 37 °C, 95% humidity and 5% CO

2, and used from passage 2nd to 9th.

2.3. Immunohistochemistry and Immunocytochemistry for Androgen Receptor

Human fascia specimens were fixed in 10% formalin solution, dehydrated in graded ethanol, embedded in paraffin and cut into 5 μm-thick sections. To detect AR, dewaxed sections were treated with 1% H2O2 in PBS for 10 min at room temperature and then washed in PBS. Samples were pre-incubated with a blocking and permeabilizing buffer (1% bovine serum albumin, BSA, and 0.5% Triton-X 0.5%, in PBS) and then incubated in mouse monoclonal anti-androgen receptor antibody, diluted 1:100 in PBS-BSA 0.5% (BioCare Medical, CA, USA), overnight at 4°C. After repeated PBS washings, samples were incubated with anti-mouse IgG, Biotinylated Antibody, 1:600, for 1h at room temperature, and then in HRP-conjugated Streptavidin (Jackson ImmunoResearch, Cambridgeshire, UK, dilution 1:250) for 30 min and then washed 3 times in PBS. After washing in PBS, the reaction was developed with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Liquid DAB + Substrate Chromogen System kit Dako, CA, USA), stopped with distilled water and counterstained with hematoxylin. Negative controls were similarly treated omitting the primary antibody, confirming the specificity of the immunostaining. Slides were then dehydrated and mounted using Eukitt (Agar Scientific).

Isolated cells from fascia were plated (150 cells/mm2 in 24-multiwells containing a glass coverslip) and allowed to attach for 48 h at 37°C. Cells were then fixed adding in each well 200 µL of 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS, pH 7.4, without washing away the medium, in order to allow a gentle fixation. After 10 min at room temperature, the cells underwent a second fixation for 10 min with 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS, pH 7.4 and then washed three times in PBS and eventually stored at 4 °C before the staining protocols were carried out. After treatment with 0.5% H2O2 in PBS for 10 min at room temperature and repeated washings in PBS, the samples were pre-incubated with a blocking and permeabilizing buffer (1% bovine serum albumin, BSA, and 0.2% Triton-X 0.5%, in PBS). Afterwards, the same protocol described above was used.

2.4. Preparation of DHT Solution

DHT (4,5α-Dihydrotestosterone or 5α-Androstan-17β-ol-3-one) was purchased as an anabolic steroid and AR agonist, derived from testosterone (by Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). According to indications, 50 mg powder of DHT were diluted in 1 mL Ethanol solution to prepare a 50mg/mL stock solution, mantained at 4°C before use.

2.5. Cell Treatment with Hormone

Isolated cells from fascia lata and thoracolumbar fascia were plated (150 cells/mm

2 in 24-multiwells containing a glass coverslip) and allowed to attach for 48 h at 37°C. The cells were then treated for 24 h with DHT in DMEM without serum, so as not to interfere with the treatment: endogenous hormone-binding proteins are present in varying concentrations in all serum and plasma samples and may markedly influence hormone treatments and assay results [

26]. Various hormone concentration were used according to the average hormone levels in the blood of males and females:

Table 1 reports the mean blood levels of testosterone and DHT in male and females (adolescent vs. adult, and pre- vs. post-menopause, respectively). The mean value for testosterone in males is equal to 4 ng/mL, with the maximum reported value equal to 10 ng/mL, whereas in females the mean level before menopause is 0.4 ng/mL, at least 10 times less with respect to males [

27,

28,

29]. DHT values are usually lower than testosterone, with different values in the peripheral tissues, but plasma levels of the two hormones are highly correlated [

30]. Being the DHT a more potent agonist for AR receptor and more used in bioassays [

31], in this work it was tested in fascial fibroblasts, at the following concentrations which reflect the testosterone levels: 0.4 ng/mL (mean female levels), 4 ng/mL (mean male levels) and 10 ng/mL (high male levels).

In each experiment, one control sample underwent the same processing steps, but did not receive hormones. After treatment, cells were washed in PBS, gentle fixed adding in the medium 200 µL of 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS, pH 7.4, and then fixed for 10 min with 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS. After repeated washings in PBS, samples were stored at 4 °C before to perform the staining protocols described below.

2.6. Collagen Staining

Picrosirius red staining was first applied to visualize collagen: Picro-Sirius Red solution (0.1 g of Sirius Red- Sigma Aldrich per 100 mL of saturated aqueous solution of picric acid) was applied to fixed cells for 20 min, and then washed out with acidified water (5 mL acetic acid, glacial, to 1 liter of water).

The immunocytochemistry procedure included the blocking of endogen peroxidase by 0.5% H2O2 in PBS for 10 min at room temperature, the pre-incubation with a blocking buffer (0.1% bovine serum albumin, BSA, in PBS) for 60 min at room temperature, and the incubation with the primary antibodies in the same pre-incubation buffer. The antibodies used were: goat anti-collagen I (Southern-Biotech (Birmingham, AL, USA), 1:300), mouse anti-collagen III (Abcam (Cambridge, UK), 1:100). After incubation overnight at 4°C and repeated PBS washings, samples were incubated with rabbit anti-goat (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 1:300, 1h) for detection of collagen-I or with anti-mouse IgG, Biotinylated Antibody, 1:600, 1h and then HRP-conjugated Streptavidin for 30 min (Jackson ImmunoResearch, Cambridgeshire, UK, 1:250), for collagen-III. After 3 washings in PBS, the reaction was developed with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (Liquid DAB + substrate Chromogen System kit Dako Corp.) and stopped with distilled water, before to counterstain nuclei with hematoxylin.

2.7. Image Analysis

In all samples nuclei were counterstained with ready-to-use hematoxylin (Dako Corp.). Images were acquired with the Leica DMR microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Computerized image analysis was performed with ImageJ software to quantify anti-androgen receptor antibody positivity in tissue samples, and Picrosirius Red, anti-collagen-I and anti-collagen-III antibody positivity in cells (staining was repeated at least 2 times, and for each sample at least 20 images were analysed, magnification 20X). The analysis were performed in cells isolated from both fascia lata and thoracolumbar fascia and expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Data of percentage of positive area following different doses of DHT were analyzed by One-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons to the control (untreated) condition. p < 0.05 was always considered as the limit for statistical significance.

3. Results

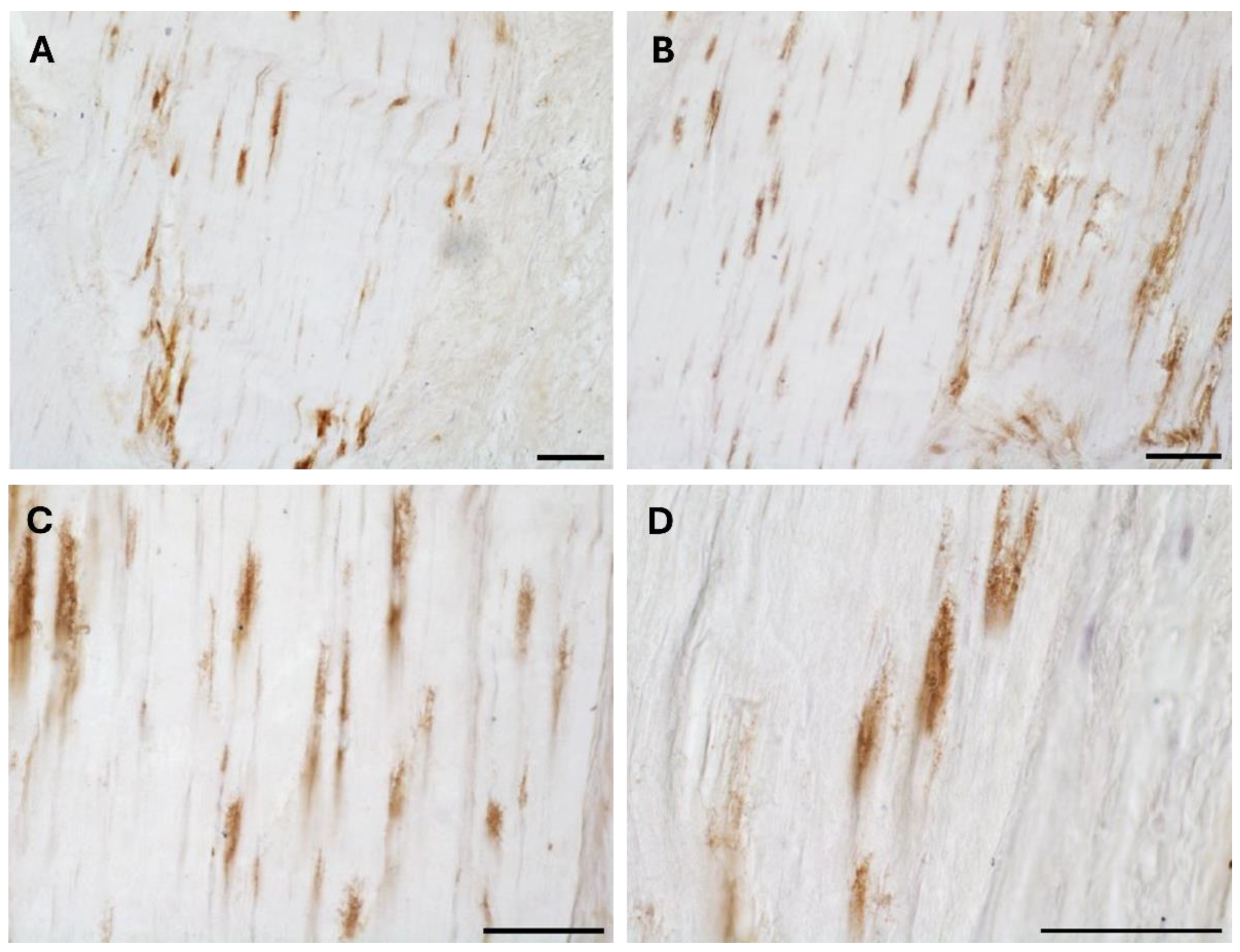

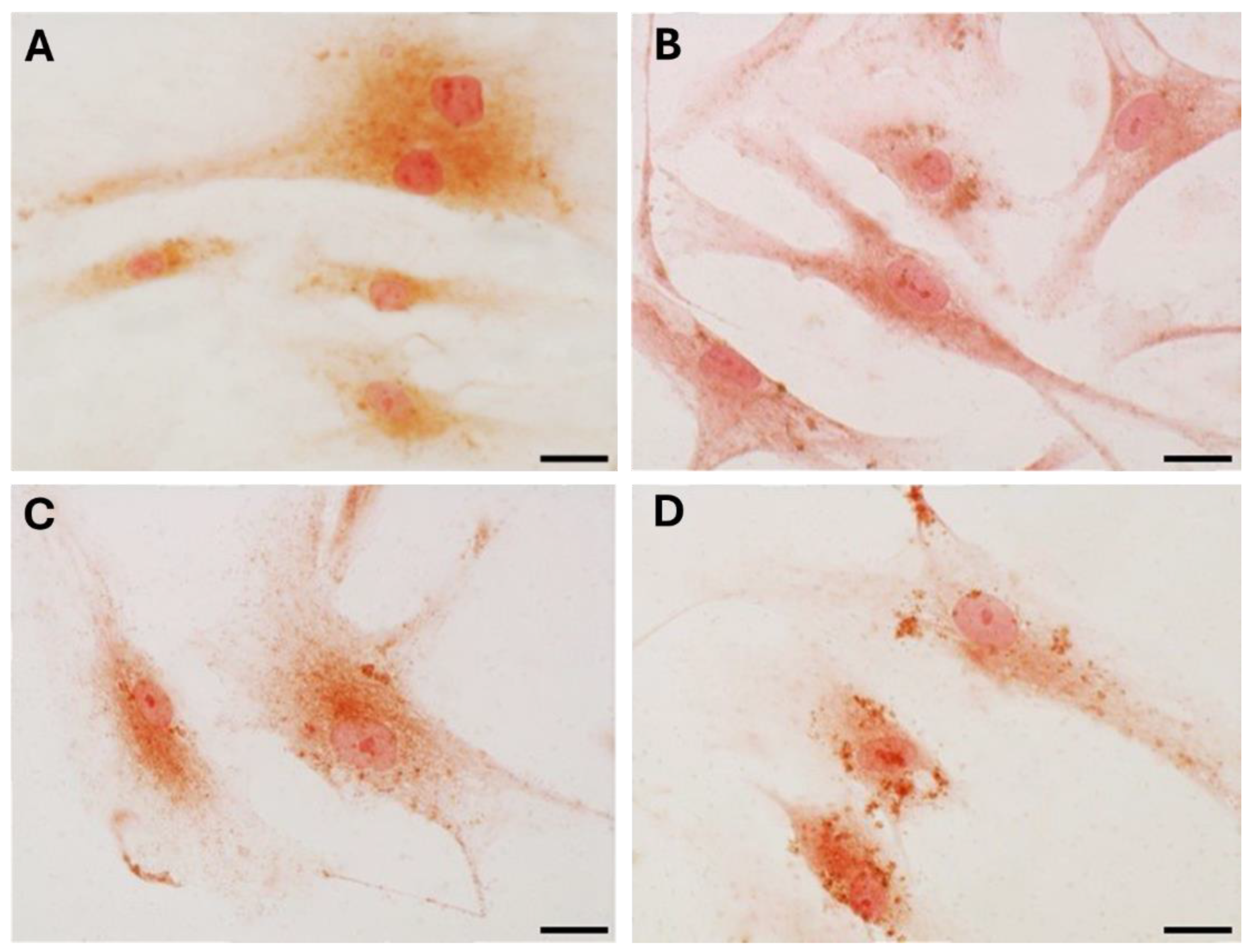

The typical fascial organization of longitudinally oriented collagen fibers and elongated fibroblasts was evident in all the samples (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). AR was expressed in the fascial fibroblasts of both the districts analyzed (thoracolumbar fascia and fascia lata) and in all the samples (both males and females) (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The positivity was expressed by the fascial fibroblasts (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2), with a degree of reactivity not statistically different between the two tissues: it was equal to 4.8 ± 2.6 % in the fascia lata and 5.2 ± 2.2 % in the thoracolumbar fascia. Not all the fibroblasts were positive for the AR receptor: some cells remained not stained, as evident especially at higher magnification (Figures 1D and 2D). No significative differences gender-related were evident by immunohistochemistry in both fascia lata (

Figure 1B,C) and thoracolumbar fascia (

Figure 2A,B).

The specificity of the staining was confirmed by the negative control with the omission of the primary antibody (

Figure 1A).

These results were also confirmed in the cells isolated from the same fascial tissues (

Figure 3), that we characterized as fibroblasts [

25], that were all positive for the hormone receptor (

Figure 3C,F). Cells showed a slightly different morphology depending on the fascial district of origin: the cells isolated from fascia lata (

Figure 3A–C) were less elongated and with less cytoplasmic extensions with respect to the fibroblasts of the thoracolumbar fascia (

Figure 3D–F). The reaction to the androgen receptor antibody showed no statistically significant differences: the positive area was 3.3 ± 1.1 % and 3.6 ± 2.1 % in the cells of fascia lata and thoracolumbar fascia, respectively. Positivity was nevertheless localized in the cytoplasm of all the cells and also in several nuclei (

Figure 3F).

Staining with Picrosirius red (

Figure 4) was used for histological visualization of collagen fibers synthesized by the cells after the exposure to various levels of DHT hormone (

Figure 4B–D). The quantification of collagen production by analysis of positive area percentage revealed modifications, statistically significant from control cells (

Table 2): after treatment with 4 ng/mL (mean male levels,

Figure 4C) and 10 ng/mL (high male levels,

Figure 4D) the staining decreased from 14.06 ± 3.58 % of the control to 11.02 ± 2.7 % and 9.77 ± 2.53 %, respectively (

Table 2). The main difference in collagen production was revealed after stimulation with low concentrations of DHT (0.4 ng/mL, female levels) (

Figure 4B): the positive area was equal to 9.43 ± 2.29 % (

Table 2). Neither the treatment nor the absence of serum affected cell density or morphology in the in vitro culture.

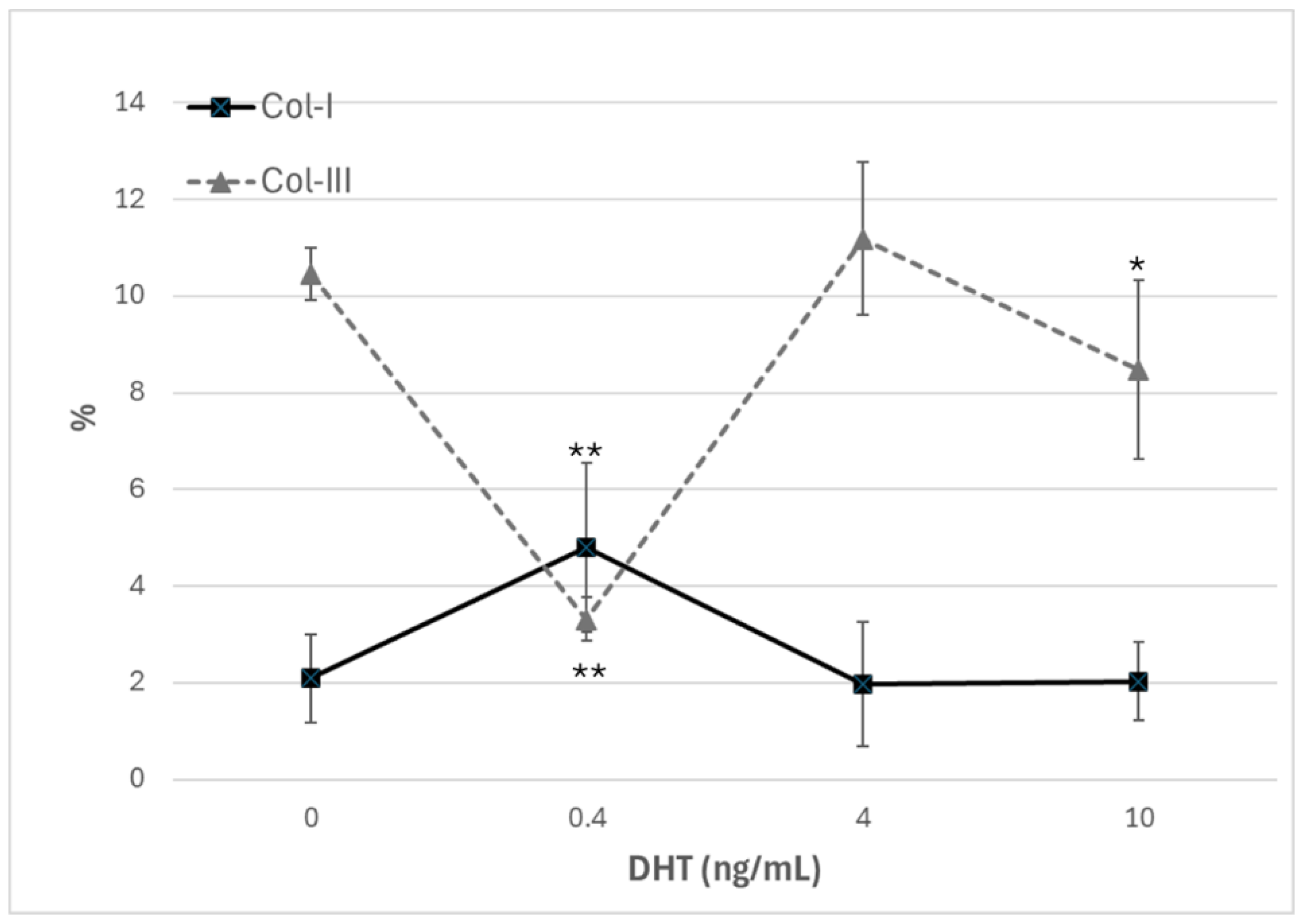

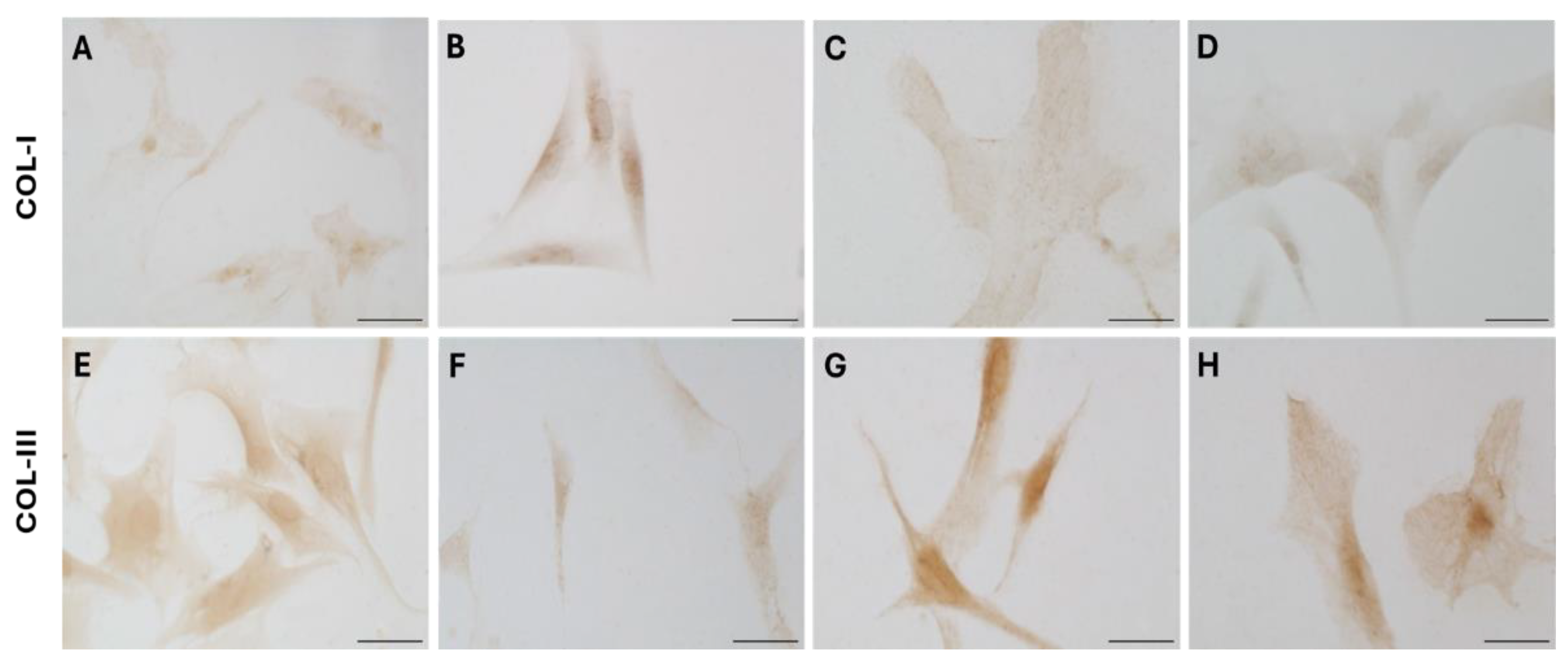

Immunocytochemical analysis was performed to explore and quantify the levels of Col-I and Col-III. All results are shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. Fascial cells modulate the production of the extracellular matrix in response to hormonal stimulation: when treated with a low female-equivalent level of DHT (~0.4 ng/mL,

Figure 6B,F) the amount of Col-I significantly increased to 4.80 ± 1.75 %, compared to 2.09 ± 0.91 % in control cells (

Figure 5). Conversely, Col-III levels were significantly reduced compared with the control (3.32 ± 0.46 % of positivity, with respect to 10.46 ± 0.53 % of the control cells,

Figure 5). In contrast, treatment with male DHT concentration (4 and 10 pg/mL,

Figure 6C,G,D,H) induced less marked changes in collagen production. Specifically, Col-I levels remain similar to those in control cells (respectively 1.98 ± 1.29 % for DHT 4 ng/mL, and 2.03 ± 0.81 % for DHT 10 ng/mL,

Figure 5). Col-III did not undergo significant changes at 4 ng/mL (11.19 ± 1.57 %) and slightly decreased with the higher dose of 10 ng/mL (8.49 ± 1.85 %), compared to control levels (10.46 ± 0.53 %) (

Figure 5). In summary, the levels of collagen, both type I and III, remained comparable to control following exposure of the cells to male doses of DHT. However, exposure to female dose of DHT significantly altered extracellular matrix synthesis by fascial fibroblast, leading to a decrease of Col-III and an increase of Col-I production.

4. Discussion

This study provides novel insights into the role of androgens in human fascia, demonstrating for the first time the expression of the AR in fibroblasts derived from both thoracolumbar fascia and fascia lata. This suggests that fascia is a hormonally responsive tissue, capable of modulating extracellular matrix remodeling in response to androgenic signals, as already documented by our previous works on female hormones effects, particularly estrogen and relaxin [

3,

4,

5]. In those previous studies, fascial fibroblasts exhibited significant changes in collagen composition and fibrillin production depending on the menstrual cycle phase and estrogen levels, highlighting the dynamic nature of fascia in women and its sensitivity to hormonal fluctuations. Specifically, estrogen peaks of ovulation or pregnancy reduced collagen type I while increasing collagen type III and fibrillin and promoting a more elastic matrix, whereas the estrogens levels of menopause promote a more fibrotic fascial tissue [

3]. However, until now, the direct role of androgens remained poorly understood.

In this study we demonstrated for the first time that human deep fascia is sensitive also to male hormones. Interestingly, we did not observe differences in androgen receptor expression or in the cellular response to hormone treatment based on either the anatomical origin of the tissue (fascia lata vs. thoracolumbar fascia) or the sex of the donor. Both male and female fibroblasts, regardless of their fascial district, expressed the receptor and responded to dihydrotestosterone in a comparable, dose-dependent manner. Our in vitro experiments revealed a dose-dependent modulation of collagen synthesis following DHT treatment. At low (female-equivalent) DHT concentrations, we observed a shift toward a stiffer matrix, characterized by an increase in Col-I (4.80±1.75%) and a decrease in Col-III (3.32±0.46%). At male-equivalent concentrations (4 and 10 ng/mL) it was revealed an overall reduction in total collagen content, decreasing from 14.06% in the control to 11.02% and 9.77%, respectively at 4 and 10 ng/mL. However, the specific levels of Col-I and Col-III, determined by immunohistichemistry, appeared less sensitive at male-equivalent concentrations, with no significant variations compared to the control, with the only exception of Col-III at 10 ng/mL (8.49±1.85 vs. 10.46±0.53% of the control). These findings align with previous reports in vascular and dermal fibroblasts, where testosterone and DHT attenuate fibrotic responses by downregulating profibrotic genes and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) via AR-mediated signaling pathways [

10,

13,

15,

33]. Cutolo and Straub (2020) demonstrated that androgens and progesterone have predominantly anti-inflammatory effects, whereas androgen-to-estrogen conversion is enhanced in inflamed tissues and in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases [

33]. Moreover, DHT has been shown to modulate fibroblast phenotype by suppressing TGF-β-induced Smad2/3 phosphorylation, a driver of fibrosis in multiple tissues [

14,

34].

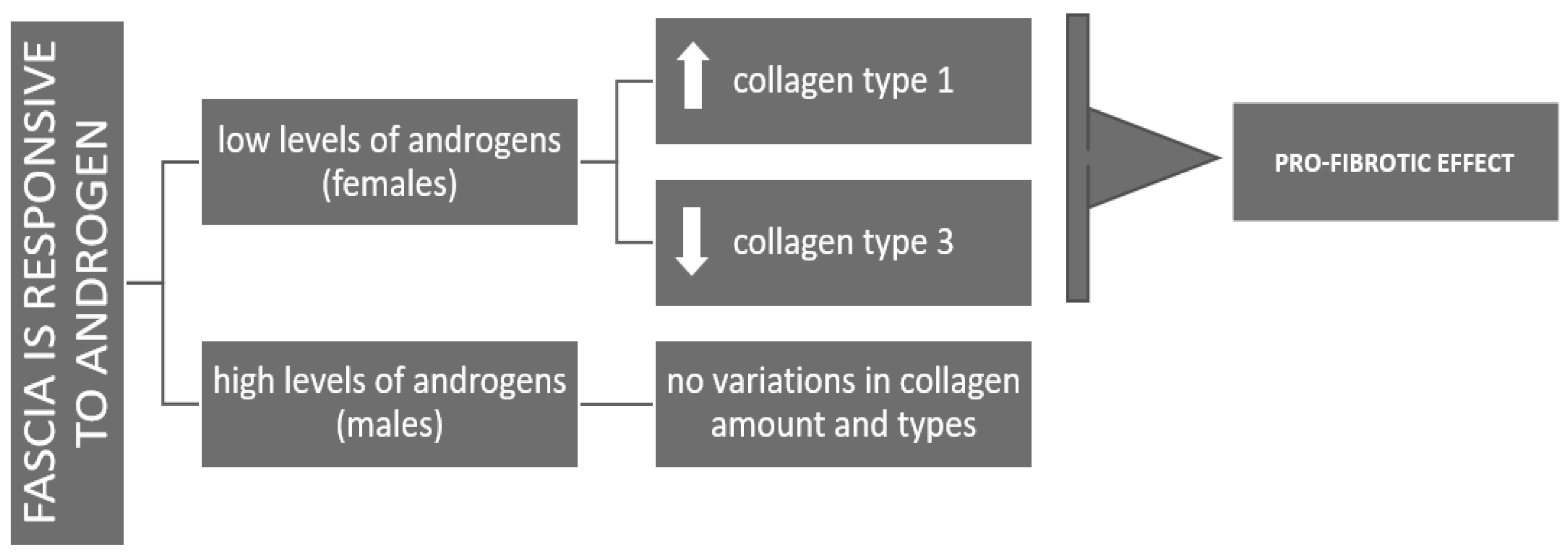

The distinct response observed at lower androgen concentrations, female-equivalent, with enhanced type I collagen production, may reflect a gender difference: in females DHT may promote ECM stiffening, potentially contributing to injury susceptibility across the menstrual cycle. In contrast, male-range androgen levels appear to support ECM homeostasis by maintaining a balance between collagen synthesis and degradation, thus preventing excessive stiffening (

Figure 7).

Interestingly, testosterone deficiency in aging men is associated with increased incidence of sarcopenia, ligament laxity, and joint instability, supporting the hypothesis of a protective role for androgens in connective tissue maintenance [

11,

12,

35,

36]. In postmenopausal women, reduced estrogen and androgen levels have been correlated with increased stiffness of fascial tissues, which may contribute to the high prevalence of chronic pain syndromes such as myofascial pain in this population [

6,

7,

21].

The identification of androgen responsiveness in fasciae of both sexes has potential clinical implications, for instance in the role of androgens as modulators in fascia remodeling, in sports injuries or in surgical recovery. Recent studies in regenerative medicine suggest that testosterone supplementation may enhance tendon and ligament healing by promoting tenocyte proliferation and ECM organization [

37]. Additionally, androgen therapies have shown beneficial effects in increasing muscle morphology in young women, resulting in type II fiber hypertrophy and improved capillarization [

22], as well as in hypogonadal men, gender-diverse people and women undergoing gender-affirming hormone therapy [

38].

Furthermore, aromatase inhibitors, which suppress estrogen conversion from androgens, have been associated with musculoskeletal side effects in breast cancer patients [

6,

7,

8]. Similarly, anabolic steroid abuse—characterized by supraphysiologic androgen levels—may dysregulate ECM homeostasis and contribute to connective tissue fragility and injury [

39].

These findings highlight the complex, dose-dependent role of androgens in regulating fascial tissue properties and may help explain sex-based variations in musculoskeletal health, by considering hormonal stability across the lifespan. Unlike women, who experience marked fluctuations in sex hormone levels during the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and menopause, men typically maintain more stable androgen levels throughout adulthood, with a gradual decline during aging. This continuous hormonal fluctuations in female population have more clinical relevance leading to cyclic modulation of fascial tension according to the periodic hormones variations.

Future investigations involving a broader range of donor ages, sexes, and hormonal backgrounds may help to clarify specific variations under different physiological or pathological conditions. Moreover, our in vitro experiments cannot fully replicate the complex hormonal and mechanical environment of fascia in vivo. However, this study underscores the importance of androgens in fascial biology and opens new persepctives for research and clinics in the field of musculoskeletal health, with the goal of finding personalized strategies in sports medicine, rehabilitation, and chronic pain management.

Figure 1.

Negative control (A) with the omission of primary antibody, and AR positive expression of paraffin sections of human fascia lata of male (B) and female (C,D). Nuclei are counterstained with hematoxylin. Scale bars: 50 µm.

Figure 1.

Negative control (A) with the omission of primary antibody, and AR positive expression of paraffin sections of human fascia lata of male (B) and female (C,D). Nuclei are counterstained with hematoxylin. Scale bars: 50 µm.

Figure 2.

AR positive expression of paraffin sections of human thoracolumbar fascia in male (A,C) and female (B,D). Nuclei are counterstained with hematoxylin. Scale bars: 50 µm.

Figure 2.

AR positive expression of paraffin sections of human thoracolumbar fascia in male (A,C) and female (B,D). Nuclei are counterstained with hematoxylin. Scale bars: 50 µm.

Figure 3.

AR expression in fibroblasts isolated from the fascia lata of the thigh (A–C), and the thoracolumbar fascia (D–F). Higher magnification images are shown in the insets. Bright-field images are shown in (A,B,D,E). Scale bars: 50 μm. (a-b-d-e). (C–F) and insets 10 um.

Figure 3.

AR expression in fibroblasts isolated from the fascia lata of the thigh (A–C), and the thoracolumbar fascia (D–F). Higher magnification images are shown in the insets. Bright-field images are shown in (A,B,D,E). Scale bars: 50 μm. (a-b-d-e). (C–F) and insets 10 um.

Figure 4.

Picrosirius red staining of fascial fibroblast after 24 h of treatment with DHT: control cells (A), 0.4 ng/mL (B), 4 ng/mL (C), 10 ng/mL (D). Scale bars: 10 μm.

Figure 4.

Picrosirius red staining of fascial fibroblast after 24 h of treatment with DHT: control cells (A), 0.4 ng/mL (B), 4 ng/mL (C), 10 ng/mL (D). Scale bars: 10 μm.

Figure 5.

Trend of positivity to anti-collagen-I and anti-collagen-III, according to the dose of DHT (ng/mL). *p < 0.05 (statistically significant) and **p < 0.01 (very statistically significant) with respect to control, untreated with hormone.

Figure 5.

Trend of positivity to anti-collagen-I and anti-collagen-III, according to the dose of DHT (ng/mL). *p < 0.05 (statistically significant) and **p < 0.01 (very statistically significant) with respect to control, untreated with hormone.

Figure 6.

Collagen-I (A–D) and Collagen-III (E–H) expression in fascial fibroblasts treated with DHT 0.4 ng/mL (B,F), 4 ng/mL (C,G), or 10 ng/mL (D,H). Control cells (A,E): cells not incubated with DHT. Scale bars: 50 µm.

Figure 6.

Collagen-I (A–D) and Collagen-III (E–H) expression in fascial fibroblasts treated with DHT 0.4 ng/mL (B,F), 4 ng/mL (C,G), or 10 ng/mL (D,H). Control cells (A,E): cells not incubated with DHT. Scale bars: 50 µm.

Figure 7.

Scheme representing the different answer of fascia to androgens in females (pro-fibrotic effects) and males (homeostasis of the ECM production).

Figure 7.

Scheme representing the different answer of fascia to androgens in females (pro-fibrotic effects) and males (homeostasis of the ECM production).

Table 1.

Average hormones serum levels in males and females [

30,

31]. Data are expressed in ng/mL.

Table 1.

Average hormones serum levels in males and females [

30,

31]. Data are expressed in ng/mL.

| |

Testosterone |

DHT |

| Male adolescent |

~ 3 - 10 (mean levels 4) |

~ 0.25 – 1 (1)

|

| Male adult |

~ 1 - 6 |

~ 0.25 – 1 (1)

|

Female pre-menopause

Female post-menopause

|

~ 0.3 - 0.5 (mean levels 0.4)

~ 0.25 |

~ 0.025 - 0.4

~ 0.01 - 0.2 |

Table 2.

Analysis of collagen content: percentage of positive area after Picrosirius red staining. .

Table 2.

Analysis of collagen content: percentage of positive area after Picrosirius red staining. .

| DHT amount (ng/mL) |

%area (mean ± SD) |

| 0 |

14.06 ± 3.58 |

0.4

4

10

|

9.43 ± 2.29 *

11.02 ± 2.7 *

± 2.53 * |