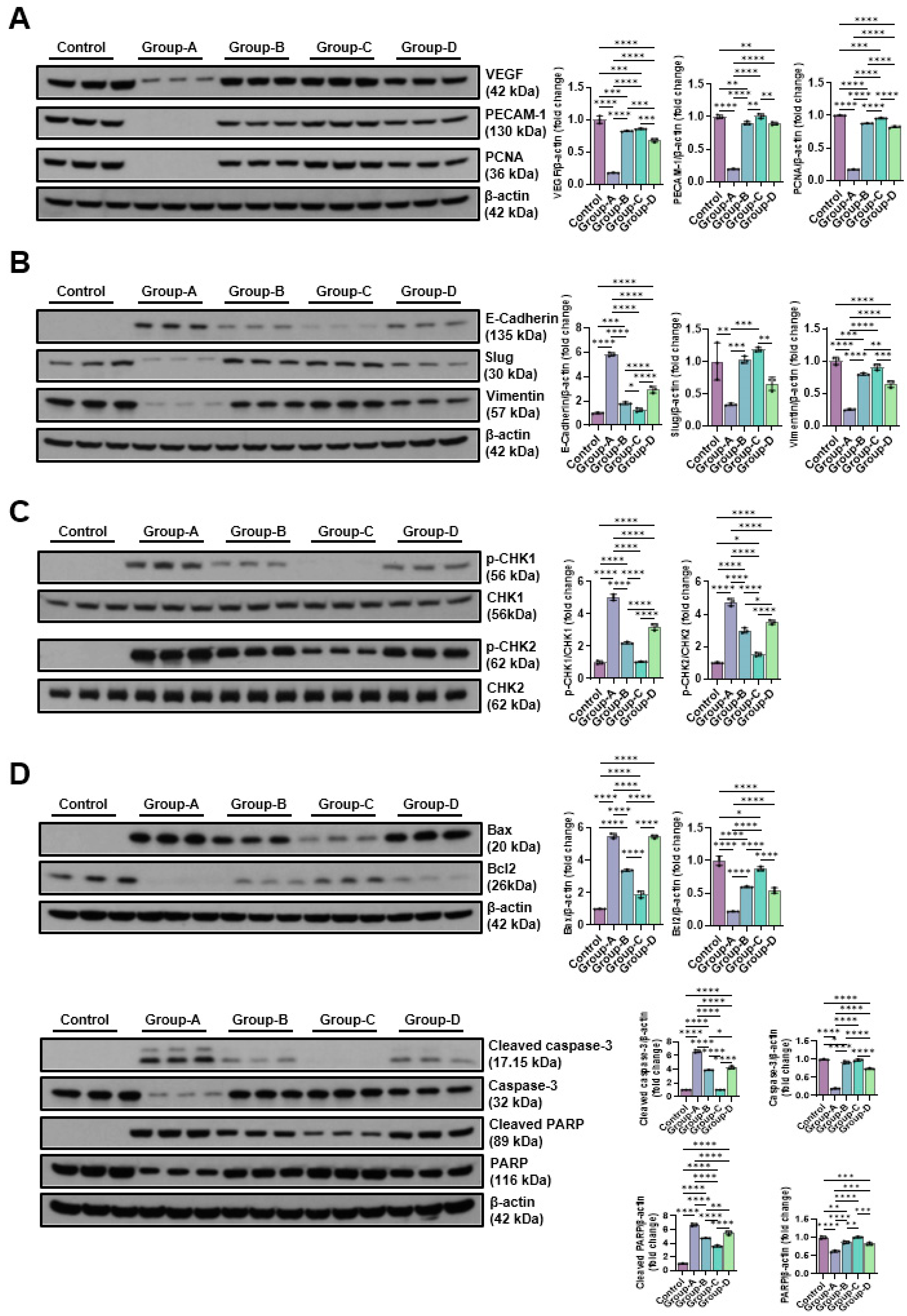

1. Introduction

Skeletal muscle plays a crucial role in human life, contributing to mobility, posture, and metabolic homeostasis. When its normal function is compromised, it can lead to musculoskeletal disorders, characterized by muscle weakening, size reduction, and reduced muscle mass and fiber cross-sectional area that are revealed histologically, significantly reducing overall quality of life [

1,

2]. Moreover, these conditions contribute to increased morbidity and mortality rates, imposing substantial socioeconomic burdens on families and communities.1 As a result, there is a strong drive to develop therapeutic approaches that can regenerate muscles and counteract muscle atrophy.

Microcurrent stimulation therapy is a treatment technique that delivers currents below 1,000 μA, a level that is barely perceptible to the human body [

3]. Factors influencing the muscle-regenerative effects of microcurrent include intensity, waveform, current type (direct [DC] or alternating current [AC]), and treatment duration, etc. Previous studies have demonstrated that low-intensity electrical stimulation (25–500 μA) significantly increases VEGF levels and enhances muscle and skin regeneration following injury and cast-induced atrophy. These effects were shown to be superior to those of high-intensity electrical stimulation (2.5–5.0 mA) in promoting wound and muscle healing [

4,

5]. Thus, these findings confirm that lower-intensity currents are more effective for regeneration.

The waveform of the electrical current has also been shown to influence muscle regeneration.6 Among various waveforms, the sine wave (SW) was found to be more effective than the rectangular wave (RW) in rat models due to its higher conductivity in the deeper portions of muscles [

6]. Furthermore, SW stimulation generated significantly greater muscle strength and caused less pain compared to RW, suggesting that the sine wave may be more efficient for muscle regeneration [

7].

In addition, a prior study revealed that direct current (DC) passing through a capacitor undergoes distortion and reduction, whereas alternating current (AC) remains unaffected under similar conditions [

6]. This finding highlights the superior conductivity of AC in deeper muscle tissues, making it more effective than DC in stimulating muscle regeneration in rats.

Based on this evidence, we hypothesize that sine wave microcurrent is the most effective form of microcurrent for muscle regeneration. While former studies have revealed the efficacy of microcurrent therapy in treating muscle atrophy in rat models [

6], no research has specifically investigated the impact of different microcurrent waveforms with alternative current on muscle regeneration in a rabbit model with cast-induced muscle atrophy. Thus, the aim of our research is to analyze the impact of different microcurrent waveforms on regenerative processes in atrophied calf muscles of immobilized rabbits.

3. Discussion

The most noteworthy outcome of this investigation is the enhanced recovery effect observed in atrophied GCMs muscle tissues following sine wave electrical stimulation, as compared to treatments using square or triangular waveforms. Among the various stimulation types applied after immobilization-induced muscle wasting, the sine waveform yielded the most favorable improvements in both structural and functional indicators of muscle regeneration. These findings were consistently demonstrated across multiple assessment modalities, including ultrasound-based muscle thickness measurements, tibial nerve compound muscle action potentials, and histological analysis of muscle fiber cross-sectional area.

Moreover, this regenerative advantage of sine wave stimulation was corroborated in an in vitro model of dexamethasone-induced atrophy using C2C12 myotubes, where sine wave-treated groups exhibited superior preservation of myotube diameter and morphology relative to other waveform conditions. These outcomes collectively suggest that sine wave stimulation can offer a more efficacious approach for mitigating muscle atrophy in both in vivo and cellular models.

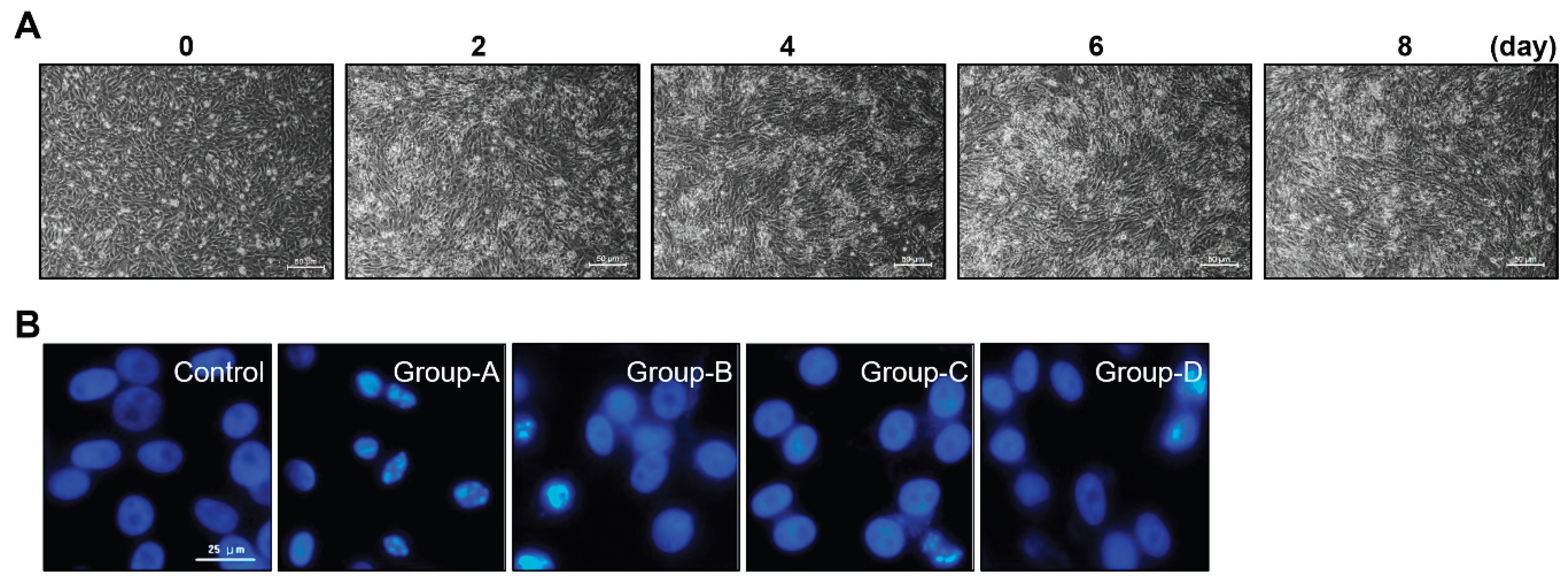

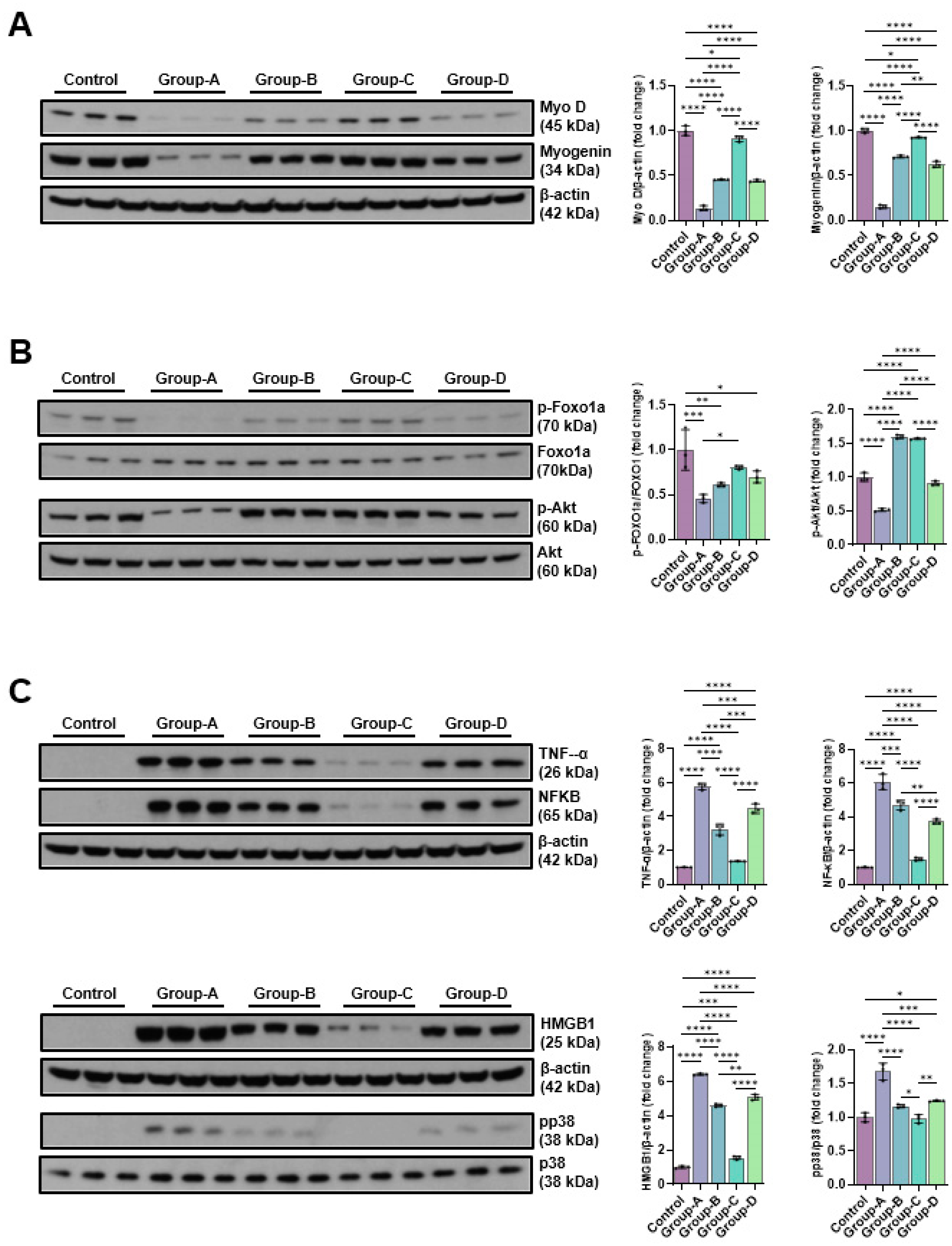

In both in vitro and in vivo models of muscle atrophy, sine wave stimulation consistently produced superior outcomes compared to square and triangular waveforms. Western blot analysis of myogenic regulatory factors revealed that sine wave treatment significantly upregulated MyoD and myogenin expression, which are the key drivers of myoblast differentiation and muscle regeneration. Simultaneously, it attenuated apoptosis by decreasing levels of cleaved caspase-3, cleaved PARP, and BAX, while increasing the expression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 and full-length caspase-3, and PARP. These outcomes indicate that sine wave stimulation can promote muscle cell survival and regeneration by modulating apoptotic pathways [

9].

In addition, the expression of angiogenesis-associated proteins, including VEGF, PECAM-1, and PCNA, was markedly elevated in the sine wave group. Notably, VEGF plays a vital role in endothelial proliferation and neovascularization, while PECAM-1 contributes to capillary density and tissue repair [

10,

11]. Sine wave stimulation was also shown to enhance p-Akt and p-Foxo1a expression, suggesting its involvement in muscle-preserving signaling cascades that are known to counteract atrophy-associated pathways [

12].

Immunohistochemical analysis performed in vivo further supported these findings, revealing group-specific enhancements in BrdU, PCNA, VEGF, and PECAM-1 expression in the sine wave-treated animals. These markers collectively indicate increased cellular proliferation, angiogenic activity, and tissue regeneration.

Moreover, sine wave therapy effectively suppressed pro-inflammatory signaling molecules, including TNF-α, NF-κB, HMGB1, and phosphorylated p38 MAPK. These mediators are known to exacerbate muscle degradation and impair regeneration [

13,

14]. Furthermore, sine wave-treated groups showed reduced expression of DNA damage-related proteins p-CHK1 and p-CHK2, implicating its protective effects on genomic integrity during recovery. Finally, EMT-related protein analysis revealed decreased expression of mesenchymal markers slug and vimentin, alongside preserved E-cadherin levels, suggesting that sine wave therapy can help maintain epithelial phenotype and reduce fibrotic transition in regenerating tissues.

Taken together, these outcomes indicate that sine wave stimulation confers a broad spectrum of therapeutic effects, including pro-regenerative, anti-apoptotic, anti-inflammatory, angiogenic, and genomic protective benefits. Its multifactorial action profile highlights sine wave as a promising modality for mitigating muscle atrophy and enhancing recovery in both cellular and animal models.

In a previous study [

15], triangular, sine, and square waveforms were comparatively analyzed during functional electrical stimulation (FES) of the upper extremity. The triangular waveform was found to require the least average current to produce the same movement and was associated with less discomfort compared to the square. These findings suggest that gradual increase and decrease in current amplitude inherent to triangular waveform may help reduce abrupt changes in stimulation, thereby minimizing patient discomfort.

In contrast, our study found the sine waveform to be the most effective. This discrepancy may be attributed to the differences in current intensity. While conventional FES typically uses stimulation intensities in the mA range to induce muscle contraction, our study had a 50 µA. This substantial difference in current levels may have contributed to the differing responses observed between the triangular and sine waveforms.

Compared to the widely used hindlimb unloading (HU) model in rodents, the cast-induced immobilization model employed in this study offers distinct advantages for studying skeletal muscle atrophy. A HU model, while effective in mimicking microgravity or reduced weight-bearing conditions, does not replicate joint fixation or localized neuromuscular inactivity as seen in clinical settings [

16]. In contrast, cast-induced immobilization results in more pronounced and site-specific muscle disuse, which better reflects clinical conditions, such as casting or post-operative immobilization [

17,

18].

Furthermore, the use of rabbits allows for higher-resolution ultrasound imaging and electrophysiological assessment due to their larger muscle mass, thereby enhancing translational relevance. These features make a cast-induced immobilization model a more physiologically and clinically representative system for evaluating anti-atrophic interventions.

Collectively, these features suggest that the rabbit cast-immobilization model provides a more clinically relevant and physiologically accurate platform for evaluating therapeutic strategies aimed at mitigating disuse-induced muscle atrophy.

This research has some limitations that warrant consideration. Firstly, the total experimental period was restricted to four weeks, including baseline assessments, two weeks of immobilization, and a two-week intervention phase. As such, the long-term regenerative effects of different microcurrent electrical waveforms remain widely unclear. Extended observation periods are needed to determine whether the observed benefits persist over time.

Secondly, only the single current intensity (50 μA) was applied in our study. The study did not examine the effects of varying microcurrent amplitudes, and it is possible that different intensities may elicit distinct physiological responses. Future research should explore a range of stimulation intensities to establish optimal parameters for muscle recovery.

Thirdly, the duration of daily stimulation was fixed at one hour, which may not represent the most effective treatment schedule. Investigating different session lengths and frequencies can provide more insight into dose-dependent therapeutic effects.

Moreover, while molecular and histological markers were analyzed, the functional assessments, such as those on muscle strength, endurance, or behavioral outcomes were not included. These evaluations are critical for translating experimental findings into clinically meaningful applications.

Lastly, the study was conducted using a limited sample size and only one animal species. Further investigations involving larger cohorts and multiple animal models are essential to improve the generalizability and translational relevance of the outcomes.

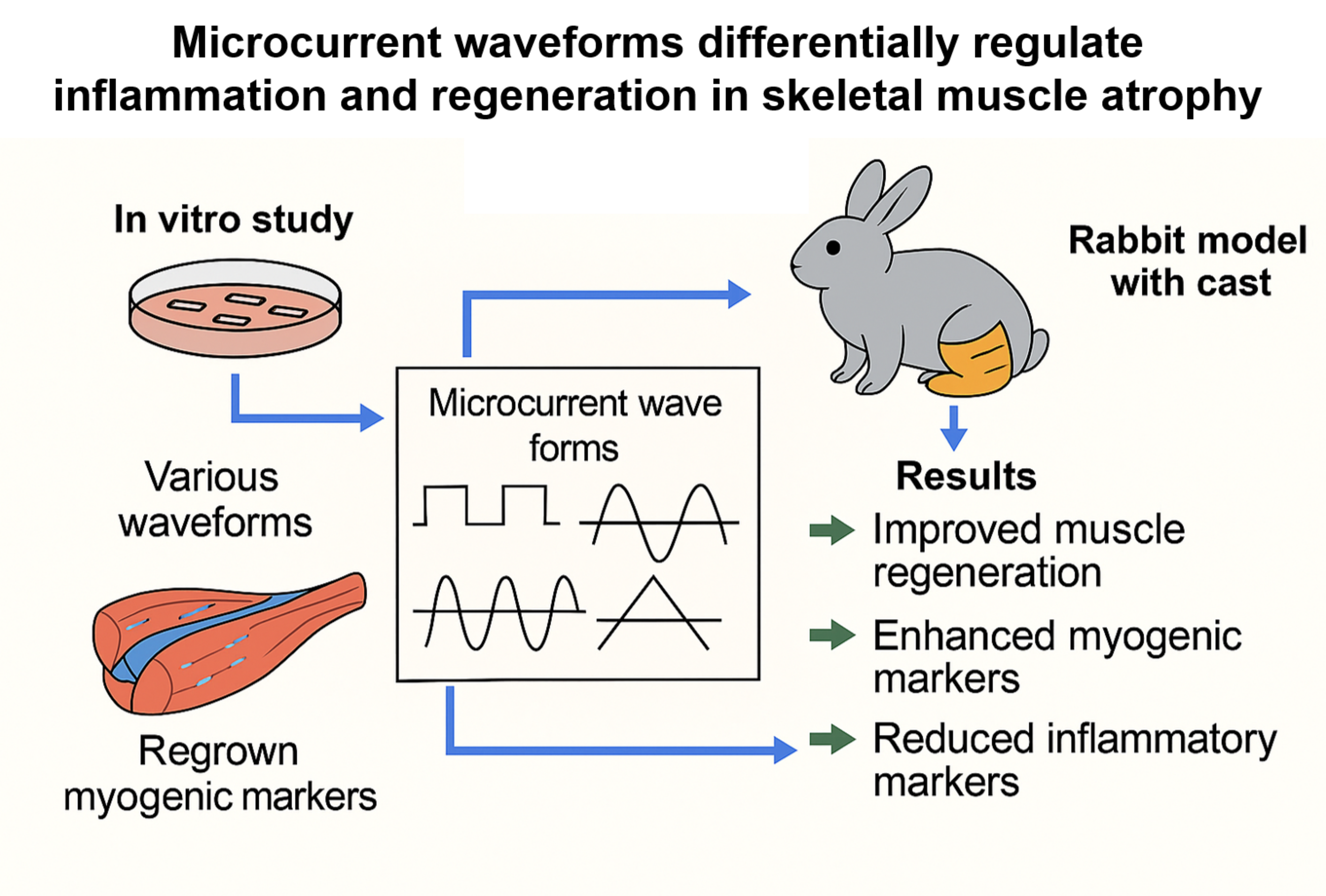

Figure 1.

C2Cl2 myoblats were incubated with 2% horse serum to induce myotube differentiation for different day periods (A) and nuclear morphology by DAPI staining (scale bar, 25μm) (B). Group 1 (control): C2C12 myoblasts with no treatment; group-A: C2C12 myoblasts with 10 µM dexamethasone; group-B: C2C12 myoblasts with 10 µM dexamethasone and microcurrent with square waveform for 1 day; group-C: C2C12 myoblasts with 10 µM dexamethasone and microcurrent with sine waveform for 1 day; and group-D: C2C12 myoblasts with 10 µM dexamethasone and microcurrent with triangle waveform for 1 day.

Figure 1.

C2Cl2 myoblats were incubated with 2% horse serum to induce myotube differentiation for different day periods (A) and nuclear morphology by DAPI staining (scale bar, 25μm) (B). Group 1 (control): C2C12 myoblasts with no treatment; group-A: C2C12 myoblasts with 10 µM dexamethasone; group-B: C2C12 myoblasts with 10 µM dexamethasone and microcurrent with square waveform for 1 day; group-C: C2C12 myoblasts with 10 µM dexamethasone and microcurrent with sine waveform for 1 day; and group-D: C2C12 myoblasts with 10 µM dexamethasone and microcurrent with triangle waveform for 1 day.

Figure 2.

The Western blotting outcomes of muscle prodution-related proteins (Myo D and myogenin) (A), muscle atrophy suppression signaling pathway-related proteins (p-Foxo1a and p-Akt) (B) and pro-inflammatory expression-related proteins(TNF-α, NFκB, HMGB1 and pp38) (C). Group 1 (control): C2C12 myoblasts with no treatment; group-A: C2C12 myoblasts with 10 µM dexamethasone; group-B: C2C12 myoblasts with 10 µM dexamethasone and microcurrent with square waveform for 1 day; group-C: C2C12 myoblasts with 10 µM dexamethasone and microcurrent with sine waveform for 1 day; and group-D: C2C12 myoblasts with 10 µM dexamethasone and microcurrent with triangle waveform for 1 day. *p indicates <0.05, ** p reflects <0.01, *** p shows <0.001, and **** p displays <0.0001 (post-hoc intergroup tests).

Figure 2.

The Western blotting outcomes of muscle prodution-related proteins (Myo D and myogenin) (A), muscle atrophy suppression signaling pathway-related proteins (p-Foxo1a and p-Akt) (B) and pro-inflammatory expression-related proteins(TNF-α, NFκB, HMGB1 and pp38) (C). Group 1 (control): C2C12 myoblasts with no treatment; group-A: C2C12 myoblasts with 10 µM dexamethasone; group-B: C2C12 myoblasts with 10 µM dexamethasone and microcurrent with square waveform for 1 day; group-C: C2C12 myoblasts with 10 µM dexamethasone and microcurrent with sine waveform for 1 day; and group-D: C2C12 myoblasts with 10 µM dexamethasone and microcurrent with triangle waveform for 1 day. *p indicates <0.05, ** p reflects <0.01, *** p shows <0.001, and **** p displays <0.0001 (post-hoc intergroup tests).

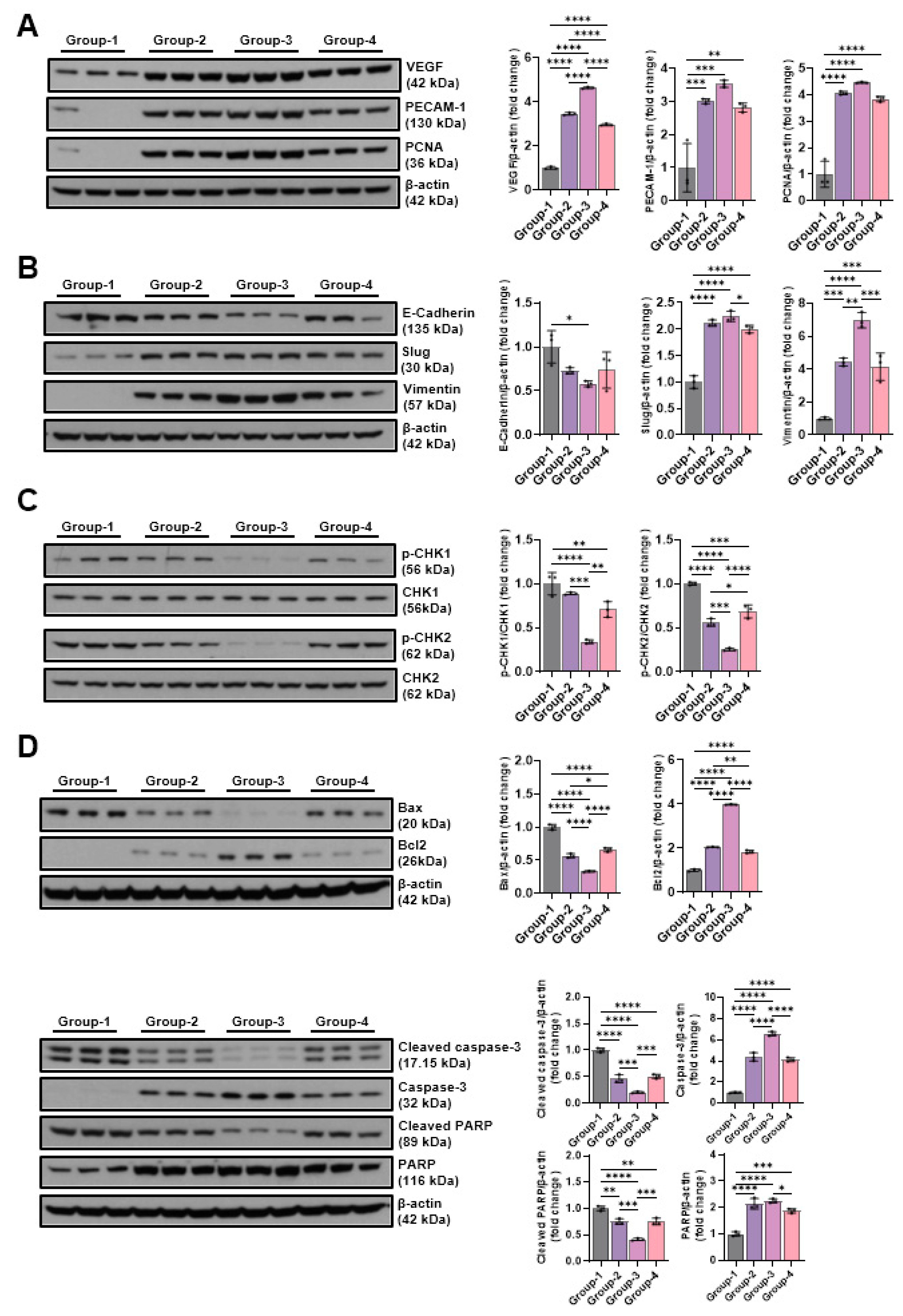

Figure 3.

The Western blot results of angiogenic factors-related proteins (VEGF, PECAM-1 and PCNA) (A), EMT expression-related proteins (E-cadherin, slug, and vimentin) (B), DNA damage-indicative proteins (p-CHK1 and p-CHK2) (C) and apoptosis-related proteins(BAX, Bcl-2, cleaved caspase-3, caspase-3, cleaved-PARP, and PARP) (D). Group 1 (control): C2C12 myoblasts with no treatment; group-A: C2C12 myoblasts with 10 µM dexamethasone; group-B: C2C12 myoblasts with 10 µM dexamethasone and microcurrent with square waveform for 1 day; group-C: C2C12 myoblasts with 10 µM dexamethasone and microcurrent with sine waveform for 1 day; and group-D: C2C12 myoblasts with 10 µM dexamethasone and microcurrent with triangle waveform for 1 day. *p indicates <0.05, ** p reflects <0.01, *** p shows <0.001, and **** p displays <0.0001 (post-hoc intergroup tests).

Figure 3.

The Western blot results of angiogenic factors-related proteins (VEGF, PECAM-1 and PCNA) (A), EMT expression-related proteins (E-cadherin, slug, and vimentin) (B), DNA damage-indicative proteins (p-CHK1 and p-CHK2) (C) and apoptosis-related proteins(BAX, Bcl-2, cleaved caspase-3, caspase-3, cleaved-PARP, and PARP) (D). Group 1 (control): C2C12 myoblasts with no treatment; group-A: C2C12 myoblasts with 10 µM dexamethasone; group-B: C2C12 myoblasts with 10 µM dexamethasone and microcurrent with square waveform for 1 day; group-C: C2C12 myoblasts with 10 µM dexamethasone and microcurrent with sine waveform for 1 day; and group-D: C2C12 myoblasts with 10 µM dexamethasone and microcurrent with triangle waveform for 1 day. *p indicates <0.05, ** p reflects <0.01, *** p shows <0.001, and **** p displays <0.0001 (post-hoc intergroup tests).

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical analysis of GCM (gastrocnemius muscle) fibers was conducted among the four groups, focusing on immobilized GCM muscles stained with monoclonal anti-myosin type II antibodies. The cross-sectional areas of type I and type II gastrocnemius muscle fibers, highlighted by red circles, were measured using an image morphometry program.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical analysis of GCM (gastrocnemius muscle) fibers was conducted among the four groups, focusing on immobilized GCM muscles stained with monoclonal anti-myosin type II antibodies. The cross-sectional areas of type I and type II gastrocnemius muscle fibers, highlighted by red circles, were measured using an image morphometry program.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical analysis of GCM (gastrocnemius muscle) fibers was conducted across the four groups, focusing specifically on immobilized GCM muscles stained with anti-BrdU and anti-PCNA antibodies. Cells or nuclei positive for BrdU and PCNA were counted along with the total number of muscle fibers within each image.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical analysis of GCM (gastrocnemius muscle) fibers was conducted across the four groups, focusing specifically on immobilized GCM muscles stained with anti-BrdU and anti-PCNA antibodies. Cells or nuclei positive for BrdU and PCNA were counted along with the total number of muscle fibers within each image.

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemical analysis of GCM (gastrocnemius muscle) fibers across the four groups involved examining immobilized GCM muscles stained with anti-VEGF and anti-PECAM-1 antibodies. The number of cells or nuclei that were positive for VEGF and PECAM-1 was counted, along with the total number of muscle fibers present in each image.

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemical analysis of GCM (gastrocnemius muscle) fibers across the four groups involved examining immobilized GCM muscles stained with anti-VEGF and anti-PECAM-1 antibodies. The number of cells or nuclei that were positive for VEGF and PECAM-1 was counted, along with the total number of muscle fibers present in each image.

Figure 7.

The Western blot results of muscle production-linked proteins(Myo D and myogenin), muscle atrophy suppression signaling pathway-related proteins (p-Foxo1a and p-Akt), and pro-inflammatory expression-indicative proteins (TNF-α, NFκB, HMGB1, and pp38). Group 1 (control): IC and sham MC after CR for 2 weeks; group 2: IC and MC after CR with square waveform for 2 weeks; group 3: IC and MC after CR with sine waveform for 2 weeks; group 4: IC and MC after CR with triangle waveform for 2 weeks. β-actin, and p38 were applied as a loading control. *p demonstrates <0.05, ** p shows <0.01, *** p stands for <0.001, and **** p reflects <0.0001 (intergroup post-hoc tests).

Figure 7.

The Western blot results of muscle production-linked proteins(Myo D and myogenin), muscle atrophy suppression signaling pathway-related proteins (p-Foxo1a and p-Akt), and pro-inflammatory expression-indicative proteins (TNF-α, NFκB, HMGB1, and pp38). Group 1 (control): IC and sham MC after CR for 2 weeks; group 2: IC and MC after CR with square waveform for 2 weeks; group 3: IC and MC after CR with sine waveform for 2 weeks; group 4: IC and MC after CR with triangle waveform for 2 weeks. β-actin, and p38 were applied as a loading control. *p demonstrates <0.05, ** p shows <0.01, *** p stands for <0.001, and **** p reflects <0.0001 (intergroup post-hoc tests).

Figure 8.

The Western blotting outcomes of angiogenic factors-related proteins(VEGF, PECAM-1, and PCNA), EMT expression-indicative proteins (E-cadherin, slug, and vimentin), DNA damage-indicative proteins (p-CHK1 and p-CHK2), and apoptosis-indicative proteins (BAX, Bcl-2, cleaved caspase-3, caspase-3, cleaved-PARP, and PARP). Group-1 (control): IC and sham microcurrent (MC) after cast removal (CR) for 2 weeks; group-2: IC and MC with square waveform after CR for 2 weeks; group-3: IC and MC with sine waveform after CR for 2 weeks; group-4: IC and MC with triangle waveform after CR for 2 weeks. β-actin was applied as a loading control. *p shows <0.05, ** p indicates <0.01, *** p reflects <0.001, and **** p stands for <0.0001 (post-hoc tests between groups).

Figure 8.

The Western blotting outcomes of angiogenic factors-related proteins(VEGF, PECAM-1, and PCNA), EMT expression-indicative proteins (E-cadherin, slug, and vimentin), DNA damage-indicative proteins (p-CHK1 and p-CHK2), and apoptosis-indicative proteins (BAX, Bcl-2, cleaved caspase-3, caspase-3, cleaved-PARP, and PARP). Group-1 (control): IC and sham microcurrent (MC) after cast removal (CR) for 2 weeks; group-2: IC and MC with square waveform after CR for 2 weeks; group-3: IC and MC with sine waveform after CR for 2 weeks; group-4: IC and MC with triangle waveform after CR for 2 weeks. β-actin was applied as a loading control. *p shows <0.05, ** p indicates <0.01, *** p reflects <0.001, and **** p stands for <0.0001 (post-hoc tests between groups).

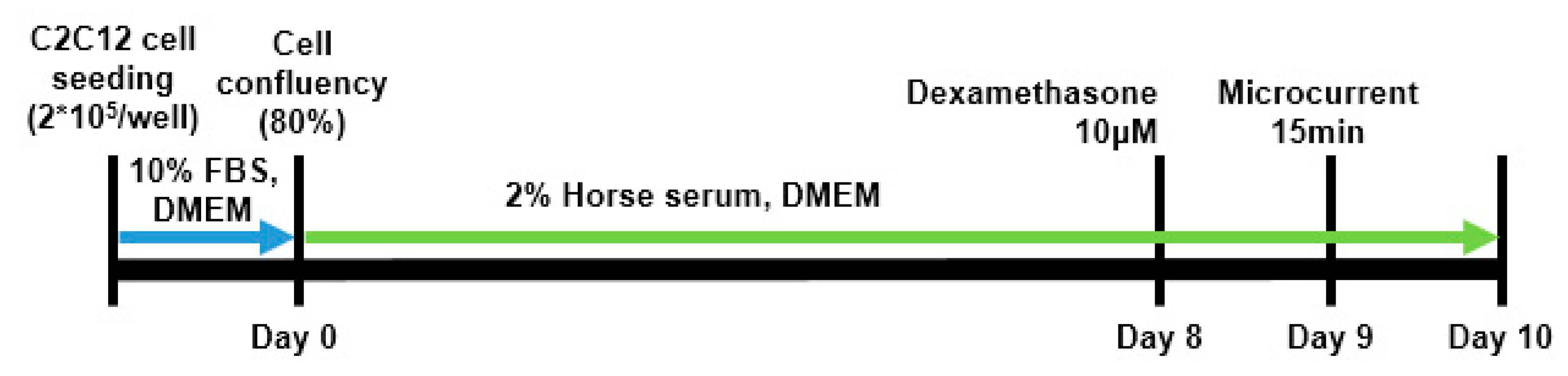

Figure 9.

Schematic diagram of C2C12 cell culture.

Figure 9.

Schematic diagram of C2C12 cell culture.

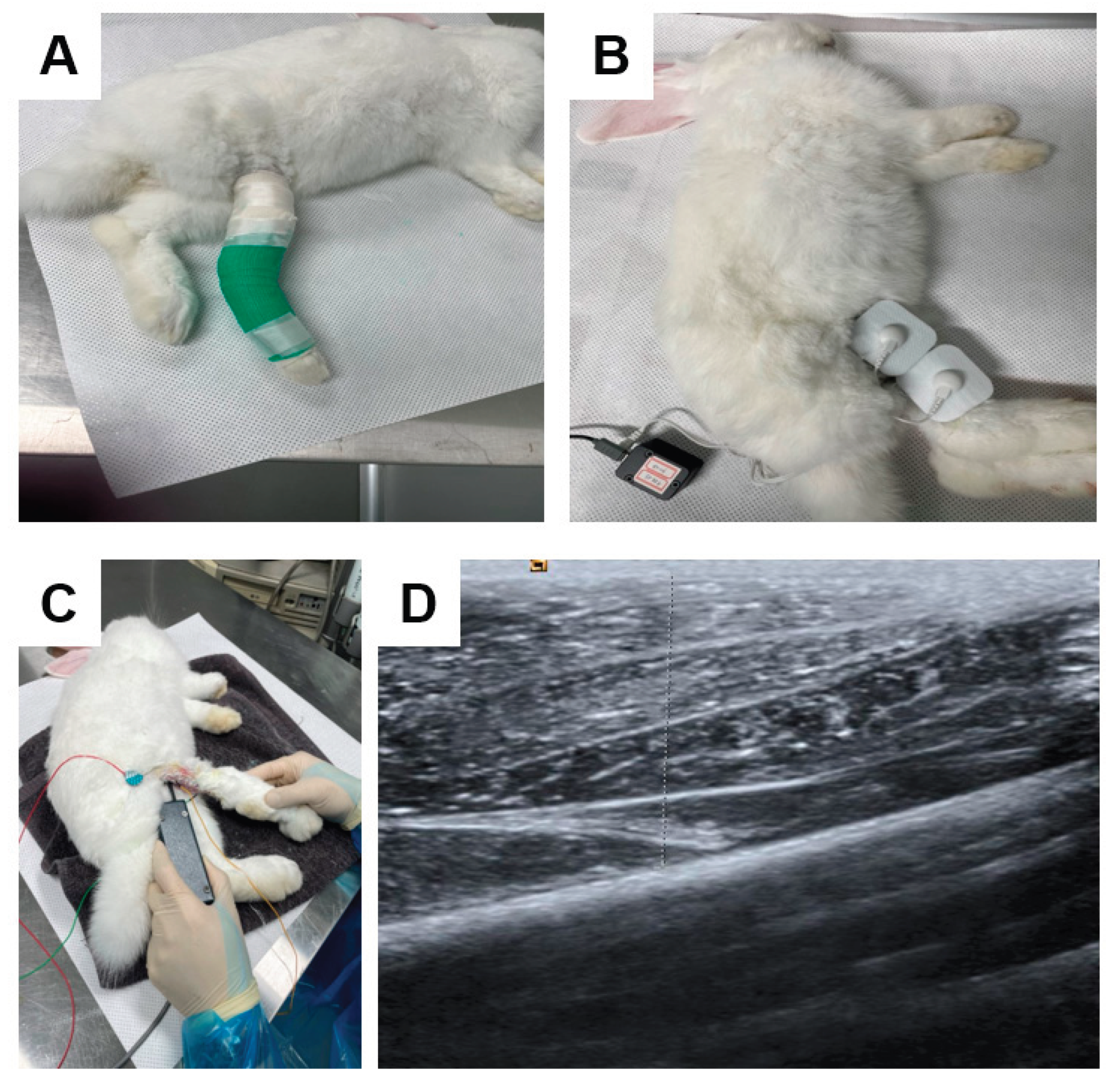

Figure 10.

d calf muscle in cast-immobilized rabbit model (B). The amplitude of the CMAP in a tibial nerve, a motor nerve conduction study was carried out (C). The thickness of the GCM (gastrocnemius muscle) was measured using ultrasound, defined as the distance between the superficial and deep aponeuroses of the GCM muscle, indicated by up–down arrows (D).

Figure 10.

d calf muscle in cast-immobilized rabbit model (B). The amplitude of the CMAP in a tibial nerve, a motor nerve conduction study was carried out (C). The thickness of the GCM (gastrocnemius muscle) was measured using ultrasound, defined as the distance between the superficial and deep aponeuroses of the GCM muscle, indicated by up–down arrows (D).

Table 1.

Atrophic changes in four groups.

Table 1.

Atrophic changes in four groups.

| Atrophic change (%) |

| Groups |

Circumference on Rt calf (cm) |

CMAP on Rt. Tibial nerve (mV) |

Rt. GCM thickness (mm) |

| Medial |

Lateral |

| G1 (Control) |

11.1 ± 4.1 |

37.7 ± 4.6 |

24.2 ± 5.7 |

21.1 ± 4.9 |

| G2 (square 50uA) |

10.6 ± 2.3 |

35.8 ± 4.4 |

26.1 ± 7.2 |

21.5 ± 7.8 |

| G3 (sine 50uA) |

11.0 ± 3.4 |

30.2 ± 7.6 |

26.7 ± 7.4 |

23.2 ± 7.4 |

| G4 (triangle 50uA) |

11.7 ± 1.6 |

35.0 ± 3.6 |

24.1 ± 4.7 |

21.8 ± 7.5 |

Table 2.

Comparison of regenerative effect in four groups.

Table 2.

Comparison of regenerative effect in four groups.

| Regenerative change (%) |

| Groups |

Circumference on Rt calf (cm) |

CMAP on Rt. Tibial nerve (mV) |

Rt. GCM thickness (mm) |

| Medial |

Lateral |

| G1 (Control) |

3.8 ± 2.5a

|

14.7 ± 5.4a

|

6.8 ± 2.3a

|

4.5 ± 2.9a

|

| G2 (square 50uA) |

10.9 ± 2.3b

|

27.8 ± 5.3b

|

16.9 ± 2.4b

|

13.4 ± 3.3b

|

| G3 (sine 50uA) |

16.1 ± 1.6c

|

43.2 ± 6.4c

|

21.8 ± 2.7c

|

19.0 ± 3.0c

|

| G4 (triangle 50uA) |

10.6 ± 1.5b

|

25.8 ± 7.8b

|

14.2 ± 3.3b

|

10.6 ± 3.4b

|

Table 3.

Comparison of motion analysis data in four groups.

Table 3.

Comparison of motion analysis data in four groups.

| Motion Analysis |

| Groups |

Total Distance (cm) |

Mean Speed (cm/sec) |

| G1 (Control) |

1275.1 ± 276.2a

|

4.3 ± 1.0a

|

| G2 (square 50uA) |

3479.8 ± 531.4b

|

11.6 ± 1.8b

|

| G3 (sine 50uA) |

3734.1 ± 1077.0b

|

12.4 ± 3.6b

|

| G4 (triangle 50uA) |

2922.1 ± 358.9b

|

9.2 ± 1.7b

|