1. Introduction

The HEPiX (High Energy Physics Unix Interest Group) Benchmarking Working Group has developed a framework for testing computational server performance using software applications from the high-energy physics (HEP) community. This framework consists of two main components: HEP-Workloads and HEPscore [

1]. HEPscore manages the execution of benchmark sets based on individual containers - Docker or Singularity. It runs the specified workloads in a sequence, collects their results, which include general system information, configuration, and a final performance score. After this, the results can be automatically sent to a remote data center.

The main purpose of HEPscore is to serve as a performance indicator for the Worldwide LHC Computing Grid (WLCG) community to evaluate server computational power. It is actively used by WLCG for resource planning, equipment procurement, future resource allocation, and accounting of experiment usage [

1]. This standardized approach for measuring computational performance ensures consistency across the diverse computing infrastructure supporting high-energy physics research.

While HEPscore addresses performance measurement requirements, the scientific community faces growing responsibility regarding energy consumption and carbon footprint [

2]. This concern is particularly relevant as computing facilities across different countries have various acquisition and operational cost structures, complicating resource sharing agreements among experimental collaborations [

3]. The issue of power consumption and environmental impact of computing resources has become a critical area of interest, directly affecting operational costs and sustainability of large-scale computing infrastructures.

Recent research has introduced the HEPscore/Watt metric as a way to quantify energy efficiency in HEP computing [

2]. This metric represents the number of events processed per unit of energy, expressed as events/Joule, since HEPscore is directly proportional to the number of processed events per second [

4]. The inclusion of power measurements during HEPscore benchmark execution adds an important dimension to hardware characterization for WLCG, with researchers advocating for using HEPscore/Watt as a key performance indicator when acquiring new hardware [

4].

Studies investigating solutions to reduce operational costs of the WLCG have demonstrated that ARM processors consume less power while maintaining high performance for HEP workloads [

3,

4]. When considering system power dissipation, ARM systems can outperform x86 servers in terms of HEPscore/Watt [

4]. Additional optimization approaches include frequency throttling as another method to reduce power consumption [

4]. These findings show significant potential for maximizing HEPscore/Watt through hardware selection and configuration adjustments.

Energy efficiency considerations extend beyond immediate operational concerns. Research on data center energy and carbon performance indicates that extending hardware lifecycle beyond optimal replacement periods can be financially and environmentally counterproductive [

5]. Retaining outdated hardware often leads to significant hidden energy and emissions costs compared to hardware replacement [

5]. By addressing these factors, operational costs related to energy purchases and environmental emissions can be reduced while simultaneously increasing research productivity [

5].

HEPscore is part of the broader HEP Benchmarks project that includes additional benchmarking tools for high-energy physics computing [

1]. The HEP Benchmark Suite functions as an orchestrator capable of running HEPscore and non-HEP benchmarks such as HS06, SPEC2017, and DB12 [

1]. This Suite is designed as a lightweight Python 3 package with minimal dependencies to ensure portability and ease of installation [

1,

6]. A key requirement for the framework is simplicity of installation and use, with provisions for long-term support [

1].

To enhance functionality, the HEP Benchmark Suite incorporates plugins that operate independently of benchmarks to collect additional metrics including machine load, power consumption, and memory usage [

2,

7]. These plugins provide a flexible and extensible mechanism for adding capabilities to the Suite [

8]. Results from benchmark runs and plugin measurements can be published to dedicated databases for analysis and comparison [

2].

For power consumption assessment, current implementations rely on utilities such as IPMItools [

4]. In validation studies, IPMI power measurements were verified against external power meters connected between servers and power sources, confirming their accuracy [

4]. However, this approach presents significant limitations for widespread deployment. The IPMItools utility requires administrative privileges, which prevents automatic power measurements on grid computing resources [

2,

7]. As noted in the documentation, "due to the permissions needed for ipmitools, power measurements cannot be automatically performed on the grid" [

2].

This limitation is particularly problematic considering that WLCG and HPC sites encompass diverse computing environments including both bare-metal servers and large virtual machines [

1]. The HEP Benchmark Suite was designed with adaptability for both Grid and HPC facilities, with potential for expansion into heterogeneous environments [

9]. However, the requirement for administrative privileges to access power measurement capabilities restricts the comprehensive energy efficiency assessment across this heterogeneous infrastructure.

The need for an alternative energy measurement approach that is hardware-independent becomes evident when examining recent advances in energy monitoring technologies. Intel's Running Average Power Limit (RAPL) interface, introduced in the Sandy Bridge architecture and refined in subsequent generations, offers a potential solution for HPC environments [

10]. RAPL provides fine-grained power and energy measurements across multiple CPU domains, with Haswell and later generations offering improved measurement granularity compared to previous implementations [

11,

12]. Before RAPL, energy estimation relied solely on performance monitoring counters, whereas newer implementations incorporate actual hardware sensors through embedded voltage regulators [

11].

Despite these advantages, RAPL implementation presents limitations for deployment in distributed computing environments. RAPL is available only on Intel and AMD processors, excluding systems with ARM or other architectures [

10]. Additionally, RAPL measurements are affected by environmental factors including CPU temperature, cross-core thermal exchange, multithreading, and system power management settings [

10]. These factors compromise measurement accuracy in uncontrolled grid computing environments. Furthermore, virtualization, which is common in grid computing infrastructures, typically restricts direct hardware access, limiting or completely preventing the use of RAPL, though recent kernel implementations do provide mechanisms to access RAPL data without strict root privileges.

The main aim of this work is to develop and implement a user-level energy measurement capability integrated directly into the HEPscore application. This implementation addresses the critical need for energy consumption measurement across the heterogeneous WLCG computing infrastructure while maintaining compatibility with HEPscore's requirements for simplicity of installation and use. The novelty of the work is the development of an automatic selection algorithm that adapts to available measurement interfaces without requiring administrative privileges, enabling energy monitoring across the diverse computing environments that comprise the WLCG infrastructure.

Our approach utilizes system-provided energy interfaces when available on supported hardware. We validate this approach against external hardware measurements to establish accuracy and reliability. The implementation integrates directly with the HEPscore application, providing energy consumption data during benchmark execution.

The principal conclusions from this work include: (1) confirmation that user-level energy monitoring provides accurate measurements; (2) demonstration of full integration with the HEPscore application; and (3) validation of the approach through comparison with external power measurement hardware. The architecture allows for future expansion to support alternative measurement methods such as performance monitoring counter-based energy models [

11] or IPMI-based monitoring [

4] on systems where RAPL is unavailable.

This research directly supports the WLCG community's need for energy efficiency metrics across its distributed infrastructure by removing hardware compatibility barriers to energy measurement. The implementation enables energy consumption tracking during benchmark execution, supporting operational cost optimization and sustainability initiatives within the high-energy physics computing community.

2. Materials and Methods

The object of this research is the software methods for measuring energy consumption of computing systems during execution of the HEPscore benchmark without requiring administrative privileges.

The research hypothesis states that software-based energy measurement methods, particularly those based on RAPL (Running Average Power Limit) technology, can provide sufficiently accurate relative measurements of computing systems' energy consumption without requiring administrative privileges or specialized hardware. This approach enables energy efficiency measurements in the distributed WLCG environment with limited access rights.

The study adopted the following assumptions:

the primary sources of energy consumption during HEP tasks are the processor (CPU) and RAM, therefore RAPL metrics measuring these components are representative for evaluating the system's overall energy consumption;

the ratio of processor energy consumption to total system energy consumption remains relatively stable for typical HEPscore workloads, allowing the use of a conversion coefficient to estimate total energy consumption;

all necessary software components for the measurement methods are already installed in the target system.

Accepted simplifications include:

environmental temperature effects on system energy consumption are not considered;

voltage fluctuations in the electrical network that may affect external measurements are not accounted for;

energy consumption of additional system components such as network adapters and disks during their active use during benchmark execution is not considered;

the research was conducted on a single hardware platform, limiting the generalizability of results across all types of computing systems.

2.1. Hardware and Software Setup

For experimental validation of the proposed measurement method, we used an HP laptop with an Intel Core i7-8565U @ 1.80GHz processor and 16GB RAM running Ubuntu 20.04. This platform was selected as an accessible representative of modern computing systems with RAPL support.

The study employed two primary methods of energy consumption measurement: an external physical meter based on PZEM-004 (reference method) and software methods based on RAPL integrated into HEPscore.

Table 1 presents a comparison of these methods' characteristics.

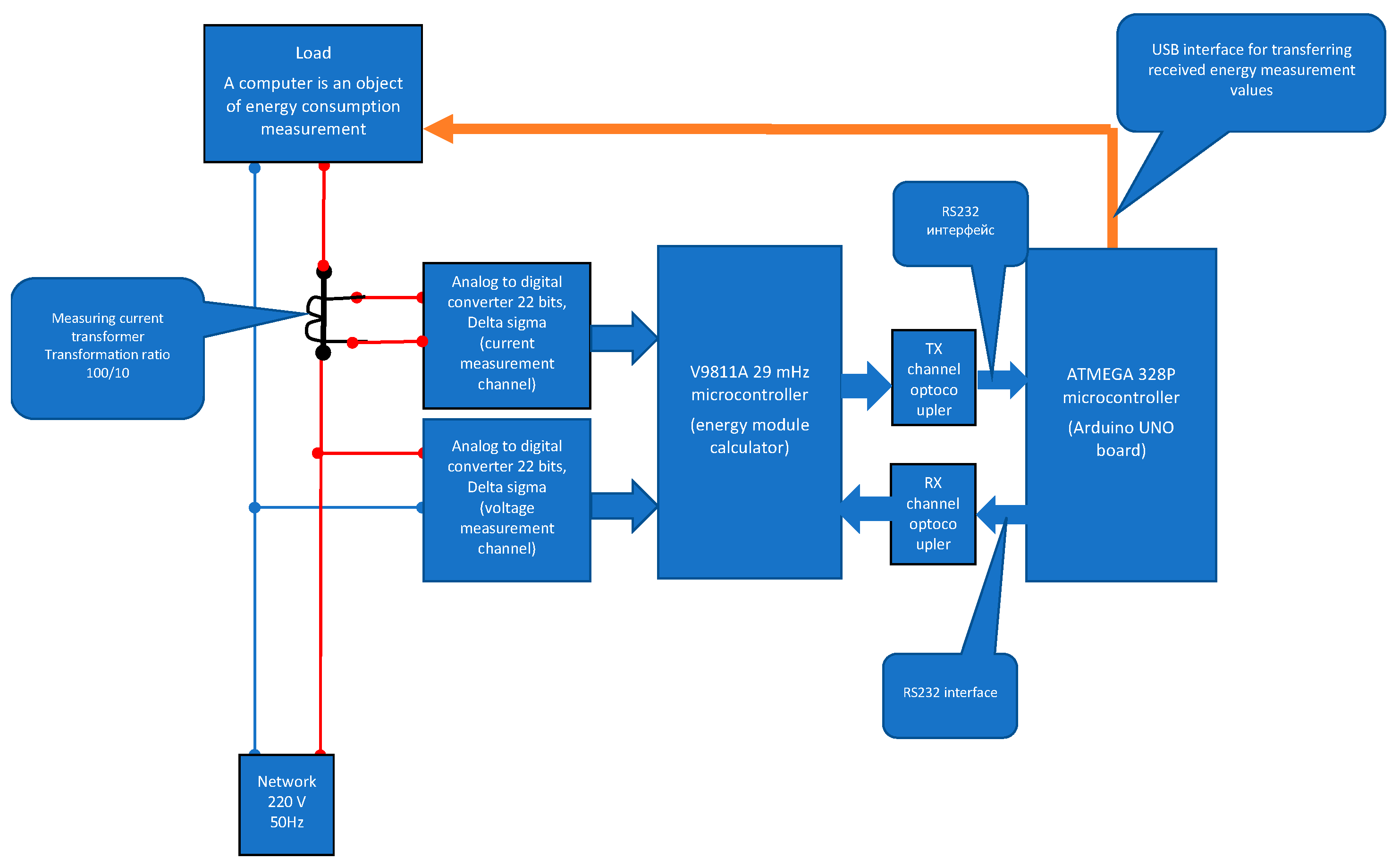

Figure 1 shows the measurement system architecture used in this study. The external PZEM-004 measurement device is connected to the power supply line between the wall outlet and the computer system under test. This configuration allows for direct measurement of the total power consumption of the entire system. The Arduino UNO serves as a data acquisition interface, collecting measurements from the PZEM-004 module and transmitting them to the computer through a USB connection. The computer simultaneously runs the HEPscore benchmark and the RAPL-based measurement software, enabling concurrent data collection from both measurement methods for comparative analysis.

The software components include the HEPscore benchmark suite, modified to incorporate energy measurement capabilities, and custom Python modules for accessing RAPL data and processing PZEM-004 measurements. Data collection occurs at one-second intervals from both measurement sources to ensure temporal alignment of the measurements for accurate comparison.

2.2. Reference Measurement System

For reference energy consumption measurements, we developed a system based on the PZEM-004 module that measures electrical network parameters, including power consumption and energy.

The system consists of the following components:

PZEM-004 module with built-in V9811A (29 MHz) microcontroller for computing energy parameters;

Two 22-bit delta-sigma ADCs for voltage and current measurement;

Current transformer with 100/10 conversion ratio;

Arduino UNO board for data collection and transmission;

Optocouplers for UART interface galvanic isolation;

USB interface for computer connection.

The external meter's operating principle: the current transformer converts load current into a proportional signal processed by the ADC. The PZEM-004 module also measures supply voltage. The V9811A microcontroller calculates instantaneous power and accumulated energy. Data is transmitted through the UART interface and optocoupler isolation to the Arduino UNO, which sends the data via USB to a computer for further analysis. This method provides reference measurements of the system's total energy consumption.

2.3. Software Implementation

For integration with HEPscore, we developed three software methods for measuring energy consumption that use different interfaces to access RAPL data:

MSR method — uses direct access to Model-Specific Registers (MSR) of the processor to obtain energy consumption data. This method requires administrative privileges (root access) but provides the most accurate data directly from hardware counters;

Powercap method — uses the Linux powercap interface, which provides access to RAPL data through the virtual file system (powercap). This method does not require administrative privileges but may need appropriate system configurations;

Perf method — uses the Linux perf software interface to access the energy-pkg counter via /sys/bus/event_source/devices/power/events/. This method also does not require administrative privileges under certain system configurations and allows obtaining processor energy consumption data.

The developed system automatically determines the availability of each method and selects the most accurate one available in the current environment. The implementation of these methods is organized in separate Python modules:

msr_power.py: Implements direct MSR access;

pcap_power.py: Implements the powercap interface approach;

perf_power.py: Implements the perf events interface approach.

These modules are managed by an EnergyMeasurement class that provides a unified interface for HEPscore integration. The class automatically selects the most appropriate measurement method based on availability and user preferences. The complete implementation is available in a public repository [

12], which contains all the source code for the energy measurement modules and their integration with HEPscore.

2.4. Integration with HEPscore

To integrate energy measurement methods with the HEPscore benchmark, we developed a specialized software extension that implements the following functions:

Automatic detection of available energy consumption measurement methods;

Collection of energy consumption data during benchmark execution;

Storage and analysis of measurement results.

The integration with HEPscore was implemented while maintaining the existing framework architecture without disrupting core functionality. The integration required modifications to the main HEPscore execution logic to start and stop energy measurements at appropriate points in the benchmark lifecycle.

2.5. Experimental Methodology

To validate the accuracy of software methods for measuring energy consumption, we conducted a series of experiments comparing RAPL indicators (software solution) with PZEM (external meter). The experimental methodology included running five typical HEPscore workloads: atlas-gen-bmk, atlas-kv-bmk, belle2-gen-sim-reco-ma-bmk, cms-reco-bmk, lhcb-sim-run3-ma-bm.

Simultaneous measurement of energy consumption was performed using the external PZEM meter and the RAPL-based software solution for all experiments. For each workload, at least 15 repeated measurements were conducted to ensure statistical reliability of the results.

Statistical analysis of the obtained results included:

Calculation of mean difference between measurement methods;

Determination of Pearson correlation coefficient;

Analysis of differences distribution using the Bland-Altman method;

Calculation of relative measurement error.

The obtained data was analyzed using Python software with pandas libraries for data processing, numpy for statistical calculations, and matplotlib for results visualization.

3. Results

This section presents the experimental findings from our research on software-based energy measurement methods for HEPscore benchmarks. We provide detailed analysis of the measurement techniques, their validation against external hardware measurements, and statistical assessment of their reliability:

3.1. Evaluation of RAPL-Based Energy Measurement Methods

Three RAPL interface access methods were tested: MSR, Powercap, and Perf. All methods provided identical measurements as they access the same underlying hardware counters. The key differences between these methods lie in the required privileges:

MSR method requires root access;

Powercap method works with regular user privileges on properly configured systems;

Perf method works with regular user privileges under certain system configura-tions;

Testing confirmed that both Powercap and Perf methods successfully operate without administrative privileges, making them suitable for deployment in grid environments with limited user permissions. The automatic detection mechanism correctly identified available measurement interfaces in all test cases, selecting the most appropriate method based on system configuration.

3.2. Comparison of RAPL and PZEM-004 Measurements

To validate the accuracy of RAPL measurements, we conducted comparative measurements with the external PZEM-004 meter.

Table 2 presents the energy consumption measurements from both methods for five HEPscore workloads.

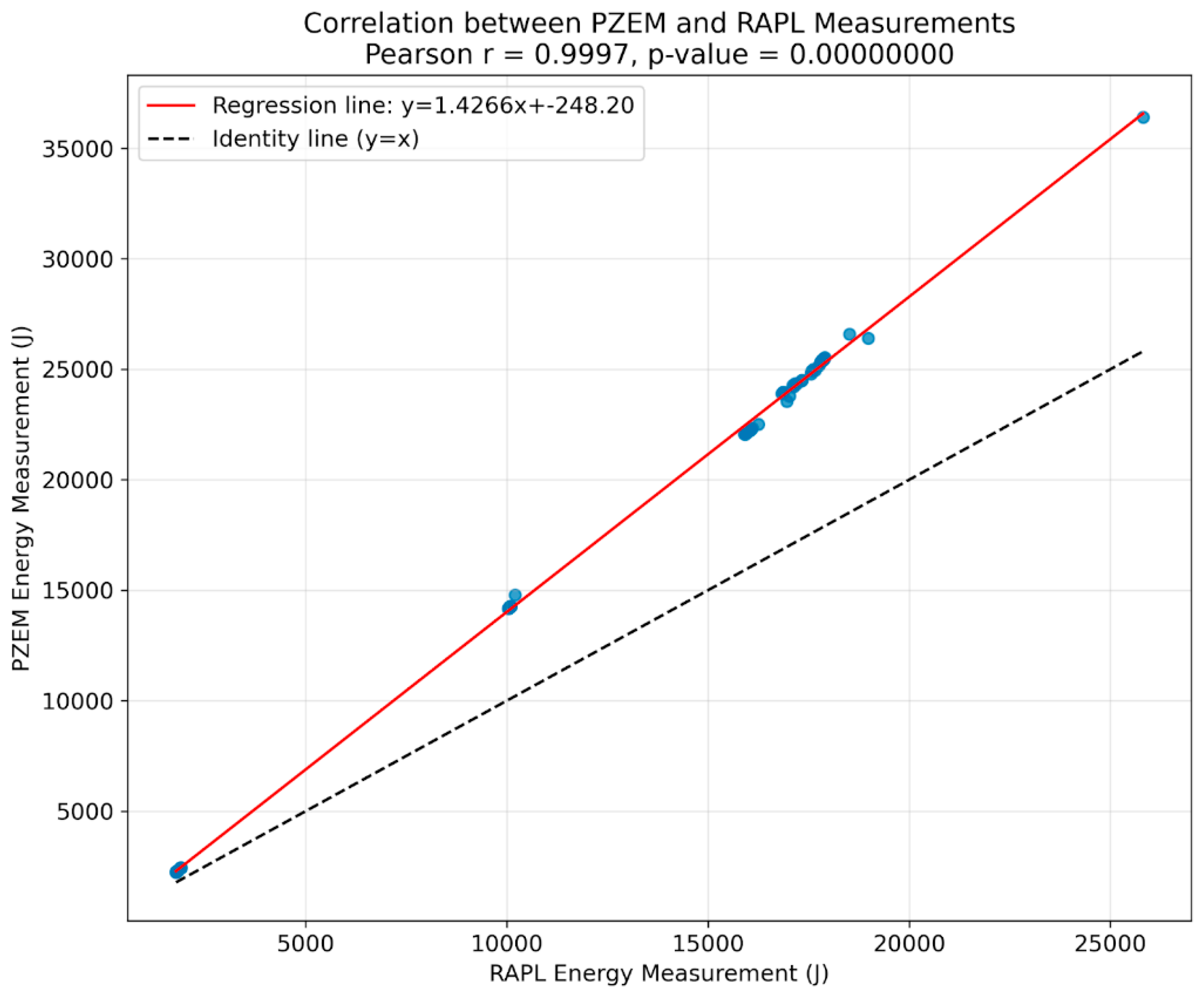

Statistical analysis of the measurement differences (

Table 3) shows a strong correlation between PZEM and RAPL data, confirming the reliability of RAPL for relative energy consumption measurements.

The Pearson correlation coefficient (r = 0.9997) indicates an extremely strong linear relationship between RAPL and PZEM measurements. Regression analysis established the following equation describing the relationship between these measurements:

where PZEM represents total system energy consumption in Joules, and RAPL represents processor and memory energy consumption in Joules.

3.3. Analysis of Measurement Consistency

Figure 2 illustrates the correlation between PZEM and RAPL measurements across all benchmark runs. The linear relationship is evident, confirming that RAPL provides consistent relative measurements despite the absolute differences in values.

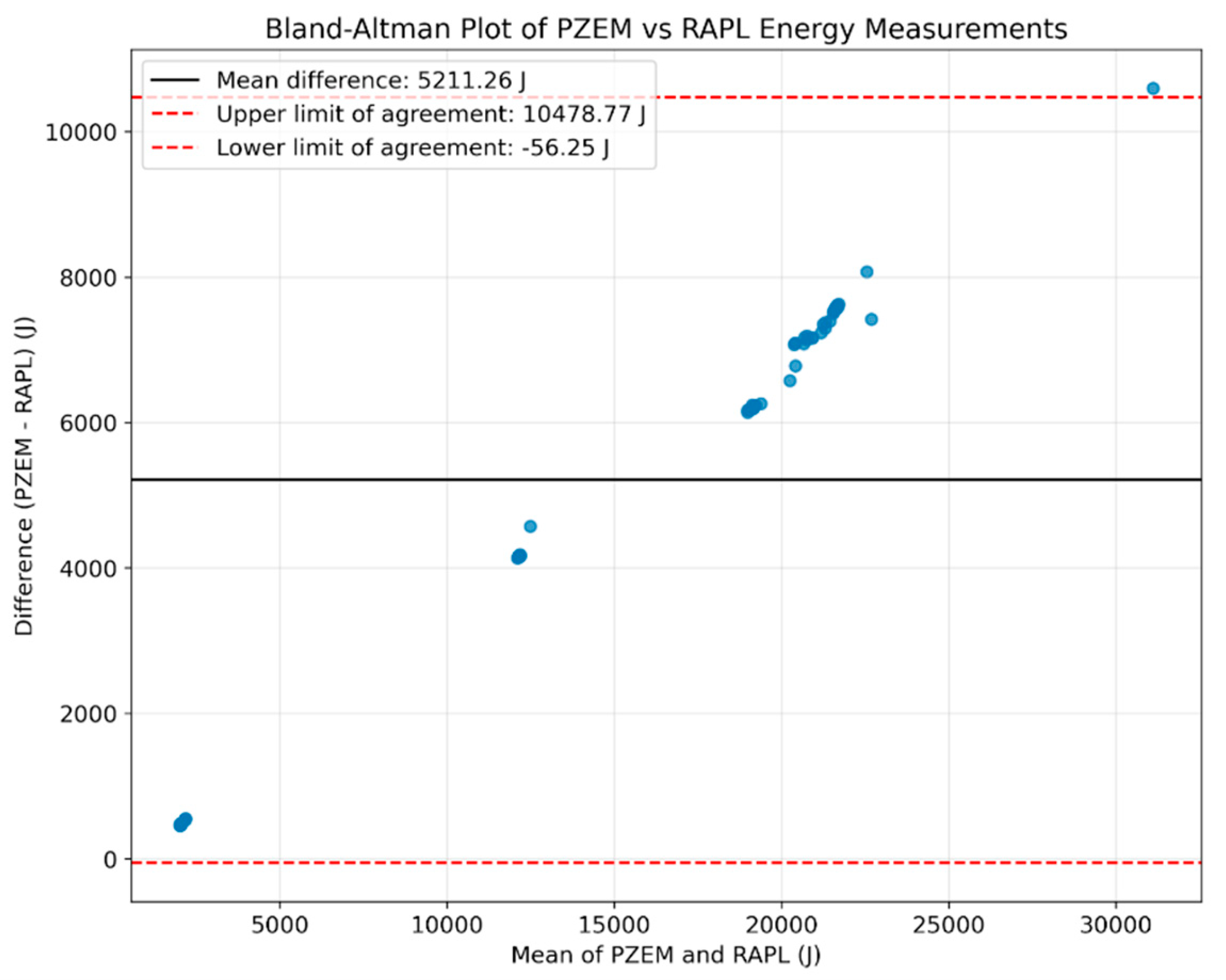

To evaluate the systematic differences between measurement methods, we constructed a Bland-Altman plot (

Figure 3). Most data points fall between the upper limit of agreement (10478 J) and lower limit (-56 J), with the majority positioned above the mean difference of 5211.25 J. This pattern indicates a systematic difference between PZEM and RAPL measurements.

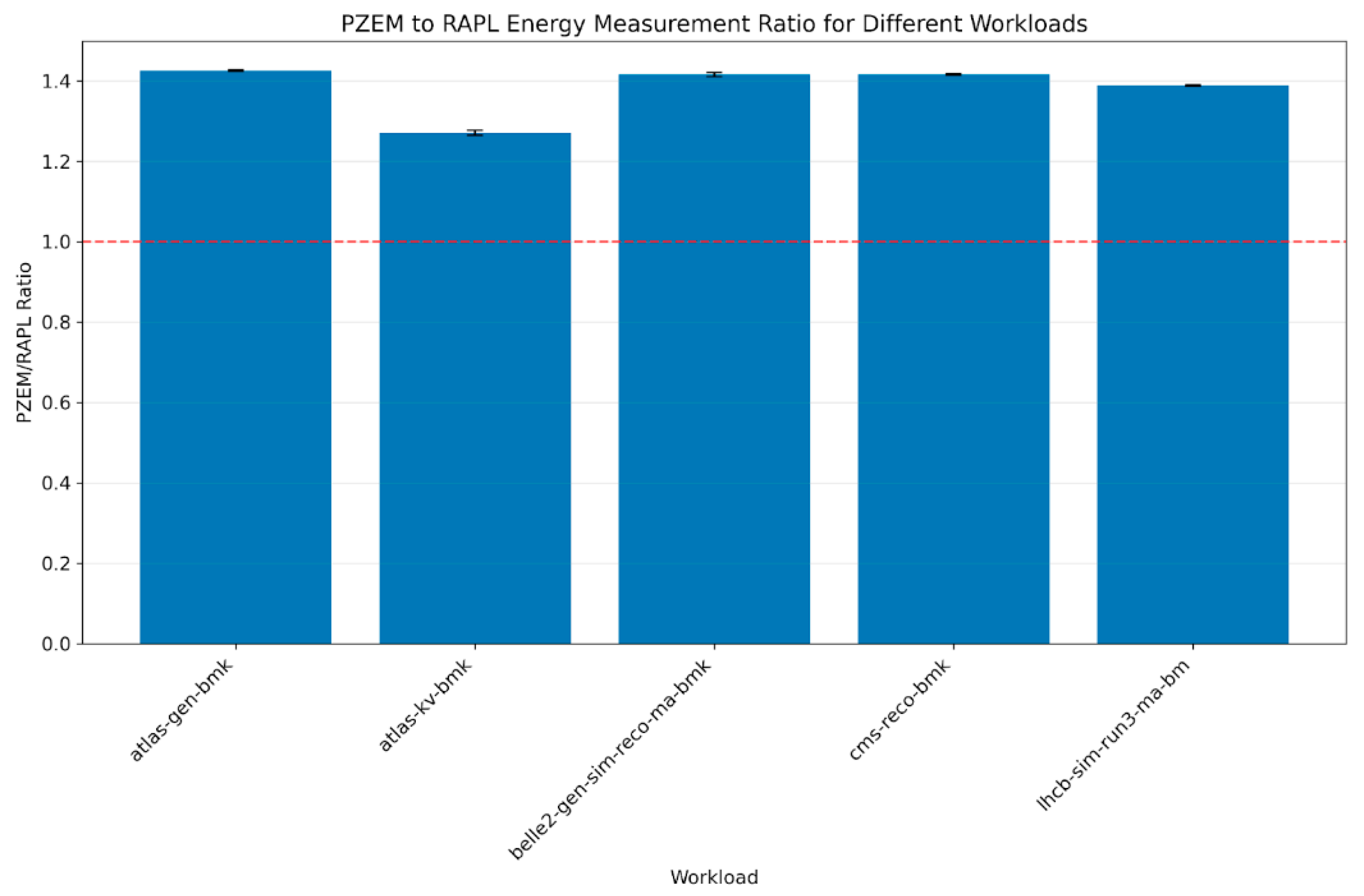

Analysis of the PZEM/RAPL ratio for different workloads (

Figure 4) shows remarkable consistency across most benchmarks, with ratios clustering around 1.4. One exception is the atlas-kv-bmk workload, which exhibits a lower ratio of approximately 1.27.

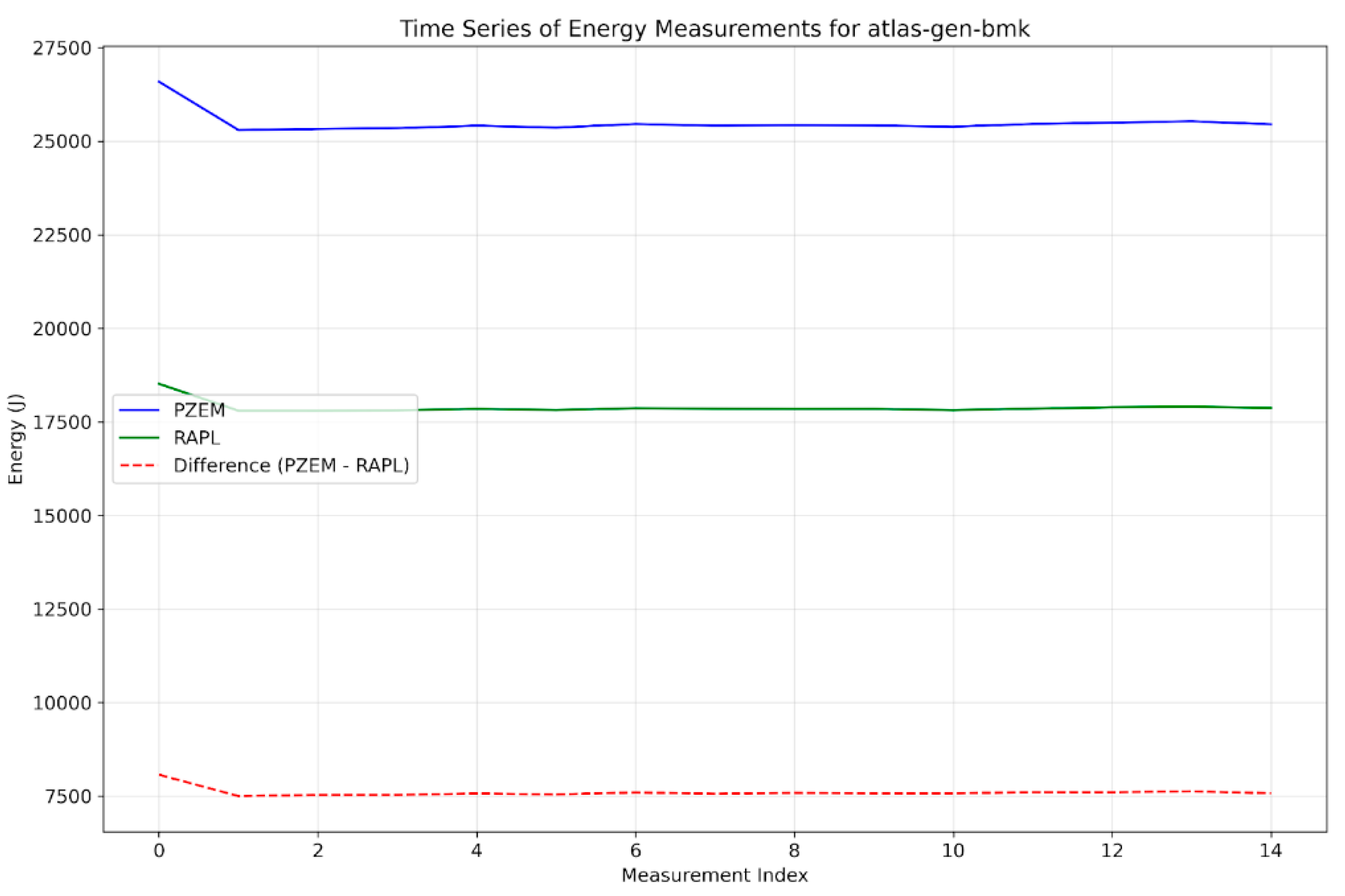

For the atlas-gen-bmk benchmark, we analyzed the time series of measurements (

Figure 5). The results demonstrate stability in both measurement methods across repeated experiments. The difference between measurements (indicated by a red dashed line) remains relatively constant, further confirming the systematic nature of differences between PZEM and RAPL.

3.4. Implementation of Automatic Transition Algorithm

The automatic method selection algorithm was tested on various system configurations. The algorithm successfully identified available interfaces in all test cases and selected the appropriate measurement method based on available system privileges.

The algorithm performs sequential checks in descending order of preference:

Checks for MSR interface availability through /msr file access;

If MSR is unavailable, checks for powercap interface availability;

If powercap is unavailable, checks for perf interface availability.

This approach ensures automatic adaptation to different user privilege levels and system configurations, enabling energy consumption measurement across diverse computing environments without manual configuration.

3.5. Integration with HEPscore

The developed energy measurement module was successfully integrated into the standard HEPscore workflow without disrupting its core functionality. The integration enhances standard HEPscore reports with the following information:

Energy consumption of each individual benchmark based on RAPL data;

Estimated total system energy consumption based on the established conversion factors;

Graphs and diagrams for visual comparison of energy characteristics across systems.

The integration maintains compatibility with existing scripts and processes, seamlessly adding energy monitoring capabilities to the standard benchmarking process. This approach allows HEPscore users to obtain energy efficiency information alongside performance data, which is crucial for optimizing hardware configuration choices for the WLCG infrastructure.

4. Discussion

The development of a novel user-level energy measurement capability integrated into HEPscore addresses a critical gap in energy efficiency assessment across heterogeneous computing infrastructures. Our findings demonstrate significant correlations between RAPL-based software measurements and external PZEM-004 hardware measurements (r = 0.9997, p < 0.001), validating the reliability of the developed approach for tracking relative changes in system energy consumption during HEP workload execution.

The correlation between RAPL and PZEM-004 measurements confirms the viability of software-based methods for energy consumption monitoring in HEP benchmarking. As shown in

Table 2, the ratio between PZEM and RAPL measurements maintains relative stability (approximately 1.4) across most tested benchmarks, enabling the application of a conversion factor for estimating total system energy consumption. This stability is particularly important for WLCG environments where direct hardware measurements may not be feasible.

The observed difference between PZEM and RAPL measurements (

Figure 3 and

Figure 5) is expected and can be attributed to the fundamental difference in measurement scope. RAPL measures energy consumption of the processor and memory subsystems only, whereas PZEM accounts for total system energy consumption including auxiliary components such as storage devices, network interfaces, and power supply inefficiency. The regression equation established in our results quantifies this relationship, providing a basis for estimating total system energy from RAPL measurements.

Our implementation differs substantially from previous approaches to energy measurement in HEP computing environments. The methodology described by Menéndez Borge [

9] relies on IPMItools and requires administrative privileges, which presents a fundamental barrier to deployment across the WLCG infrastructure. As explicitly noted in the HEP Benchmark Suite documentation: "due to the permissions needed for ipmitools, power measurements cannot be automatically performed on the grid" [

2].

Unlike the approach presented by Simili et al. [

4], which employs measurement methods optimized for controlled research environments, our solution implements an automatic selection algorithm that adapts to diverse system configurations. This adaptability is crucial for the heterogeneous WLCG infrastructure, which encompasses various hardware platforms, operating systems, and security constraints.

The integration directly into the HEPscore application aligns with the HEP Benchmark Suite's design principles of simplicity and portability [

1]. By eliminating the requirement for external hardware or administrative privileges, our implementation enables widespread adoption across the distributed computing infrastructure supporting high-energy physics research.

The architecture of our novel implementation offers several advantages over existing solutions:

User-level operation without administrative privileges, enabling deployment across grid computing environments with restricted access policies;

Automatic adaptation to available measurement interfaces on the target system;

Direct integration with HEPscore, providing energy metrics alongside performance measurements;

Validation against external hardware measurements to establish accuracy and reliability;

Compatibility with the HEP Benchmark Suite plugin system for data collection and analysis.

These features address the limitations identified in previous energy measurement approaches while maintaining compatibility with existing benchmarking workflows. The implementation supports the HEPscore/Watt metric proposed by Simili et al. [

4], providing a standardized approach to quantifying energy efficiency across the WLCG infrastructure.

Several limitations of the current implementation must be acknowledged. The primary limitation is the dependence on RAPL technology, which is predominantly available on Intel processors and some AMD processors. While our implementation includes fallback mechanisms for systems without RAPL support, the accuracy of these alternative methods may vary.

The conversion factor between RAPL and total system energy consumption may differ across hardware configurations, particularly for systems with significantly different component distributions (e.g., storage-intensive versus compute-intensive servers). Additional validation across diverse hardware platforms is necessary to establish the stability of this relationship.

Environmental factors such as ambient temperature, cross-core thermal exchange, and system power management settings can influence measurement accuracy, as noted by Alqurashi and Al-Hashimi [

10]. While our methodology accounts for some of these factors, complete isolation from environmental variables is not possible in production environments.

The accuracy of RAPL measurements compared to external physical measurements has been questioned in some research. Fahad et al. [

11] reported average errors between RAPL and external power meters ranging from 8% to 73% depending on the workload. However, our validation shows substantially better correlation for HEP workloads, suggesting that the nature of these applications may lead to more consistent energy consumption patterns.

This research establishes a foundation for several future developments in energy-efficient computing for high-energy physics:

Extension of support to additional processor architectures, particularly ARM-based systems which have demonstrated superior energy efficiency for HEP workloads [

3,

4];

Integration with performance monitoring counter (PMC) based energy models for systems without direct hardware energy measurement interfaces;

Development of dynamic energy optimization techniques based on real-time energy consumption monitoring;

These directions align with the growing emphasis on sustainability in scientific computing infrastructures and support the WLCG community's need for comprehensive resource planning that incorporates both performance and energy efficiency metrics.

The implementation of our novel user-level energy measurement capability in HEPscore represents a significant advancement in the assessment of energy efficiency across the distributed computing infrastructure supporting high-energy physics research. By removing barriers to energy measurement, this work enables the WLCG community to incorporate energy consumption as a standard metric in resource planning, hardware procurement, and operational optimization decisions.