Submitted:

22 May 2025

Posted:

23 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

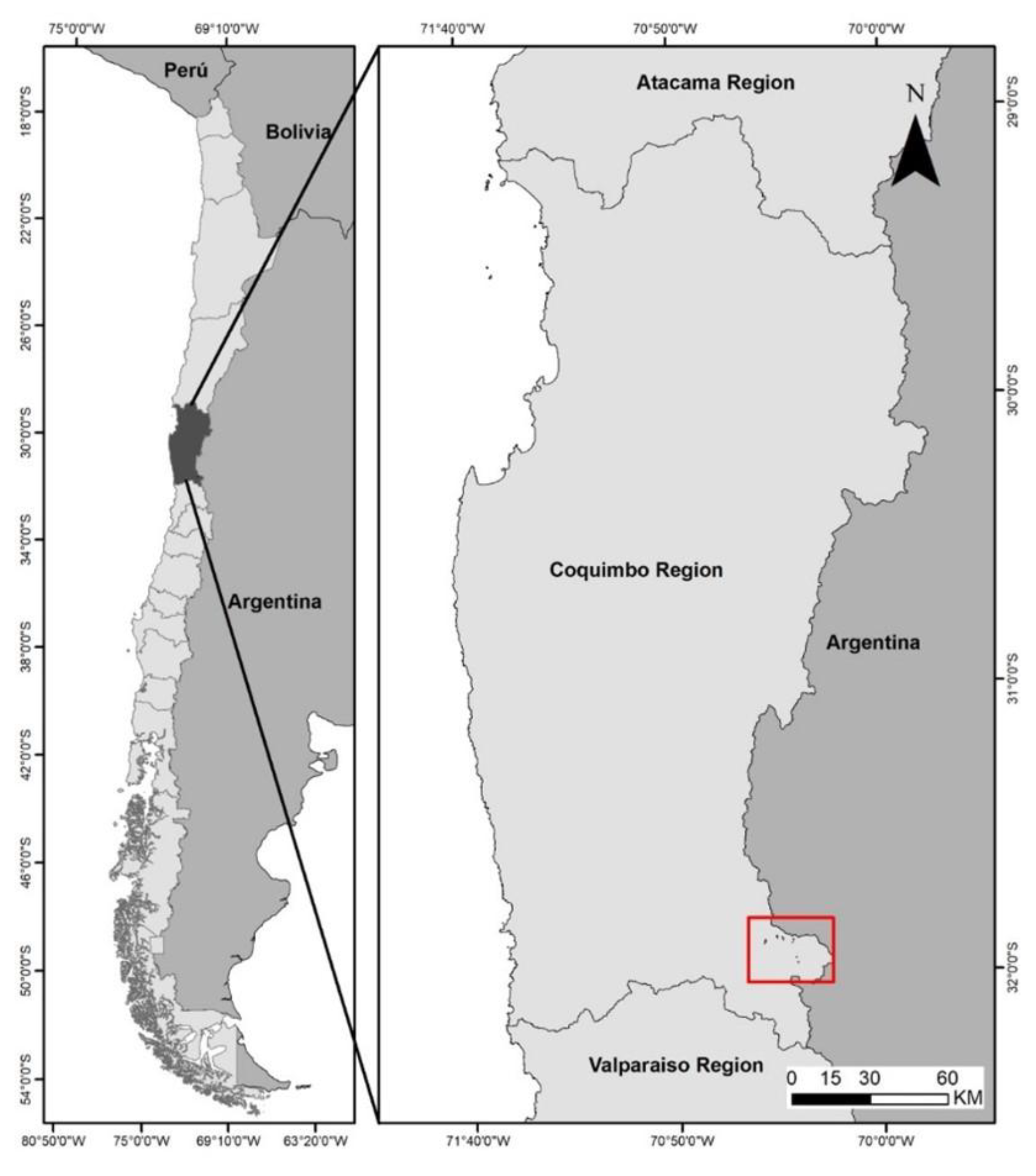

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Dry Matter Production in the Grassland

2.3. Evenness of Plant Species in the Grassland

2.3. Evenness of the Diet

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

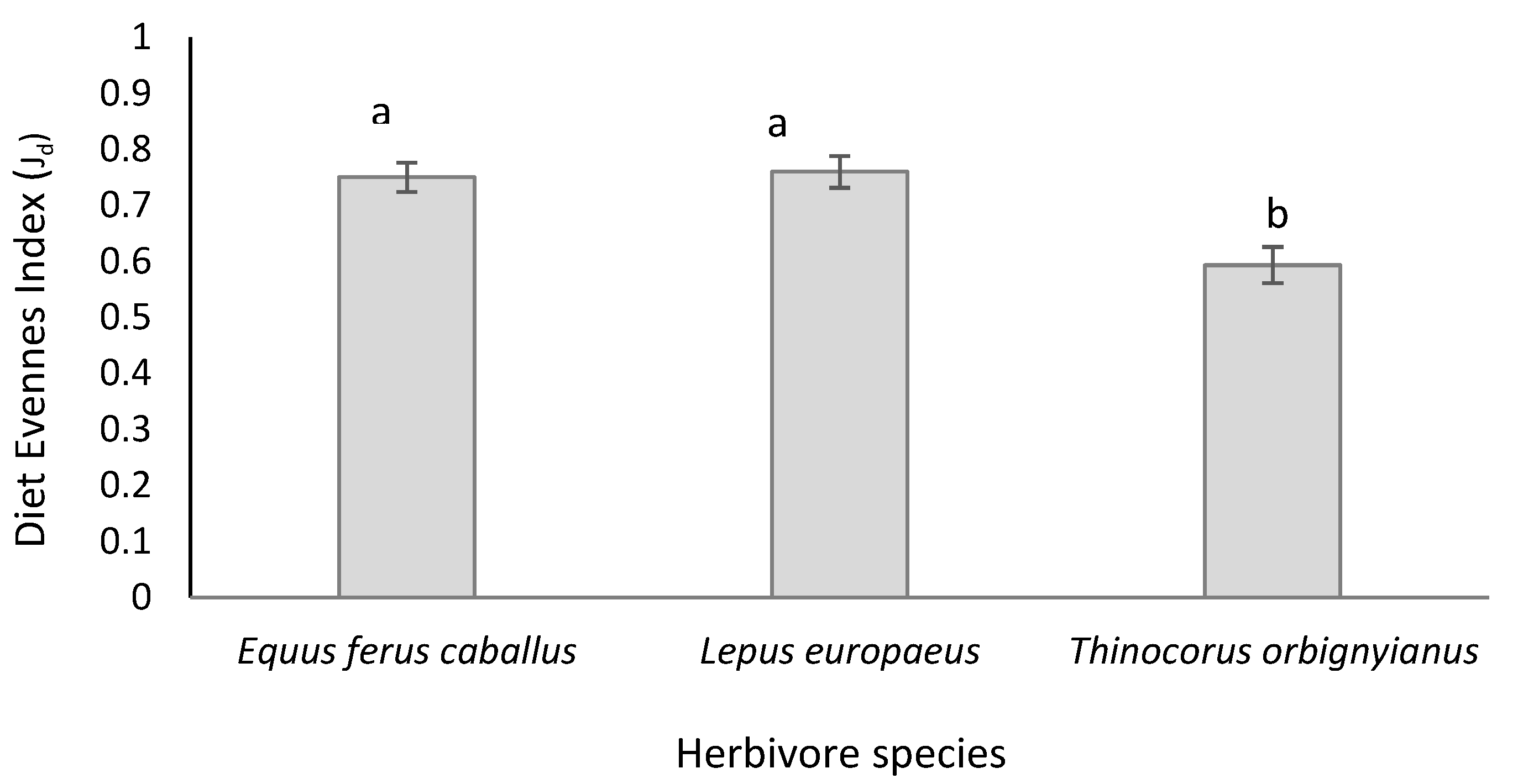

3.1. Evenness of the Diet

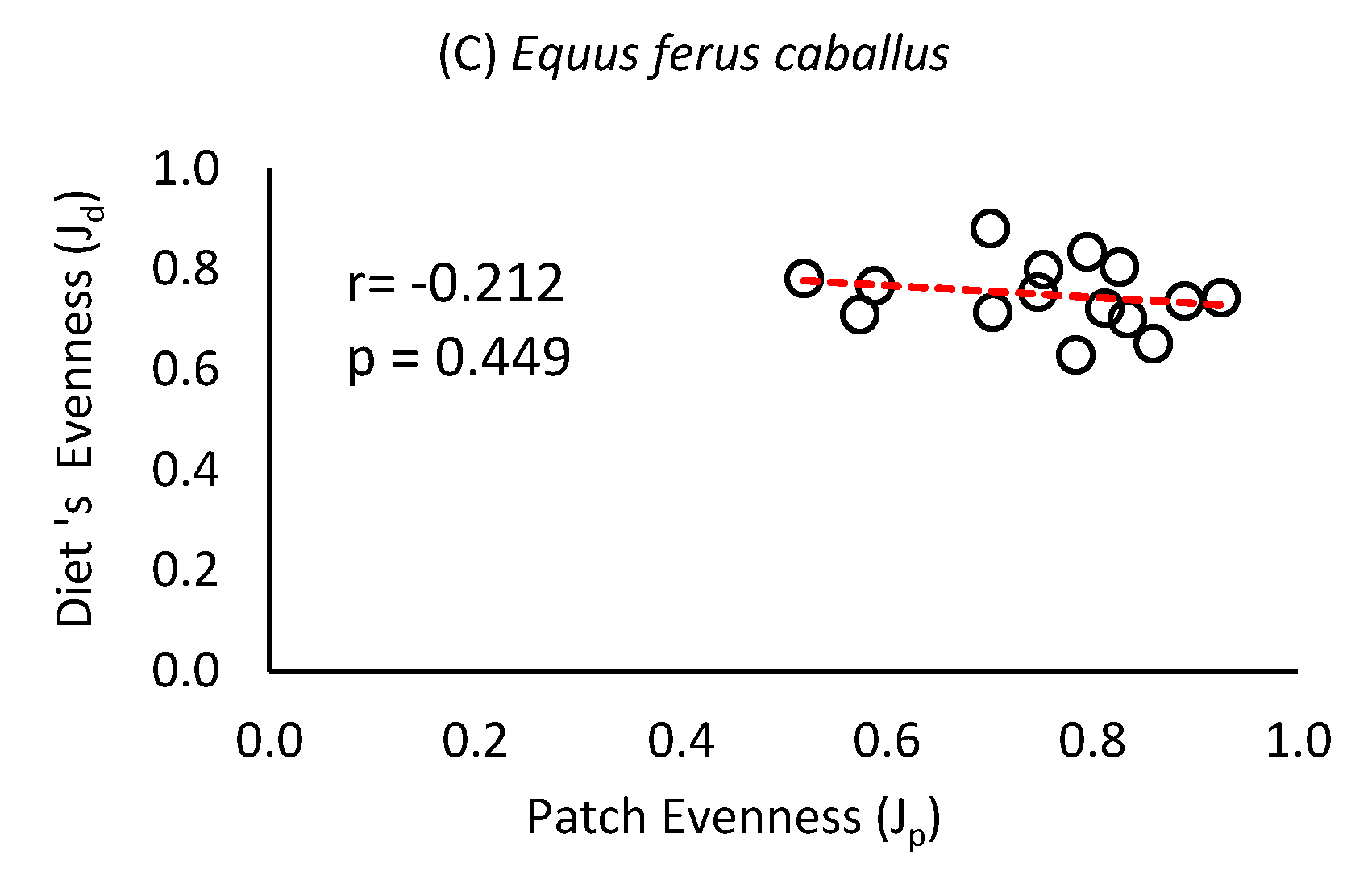

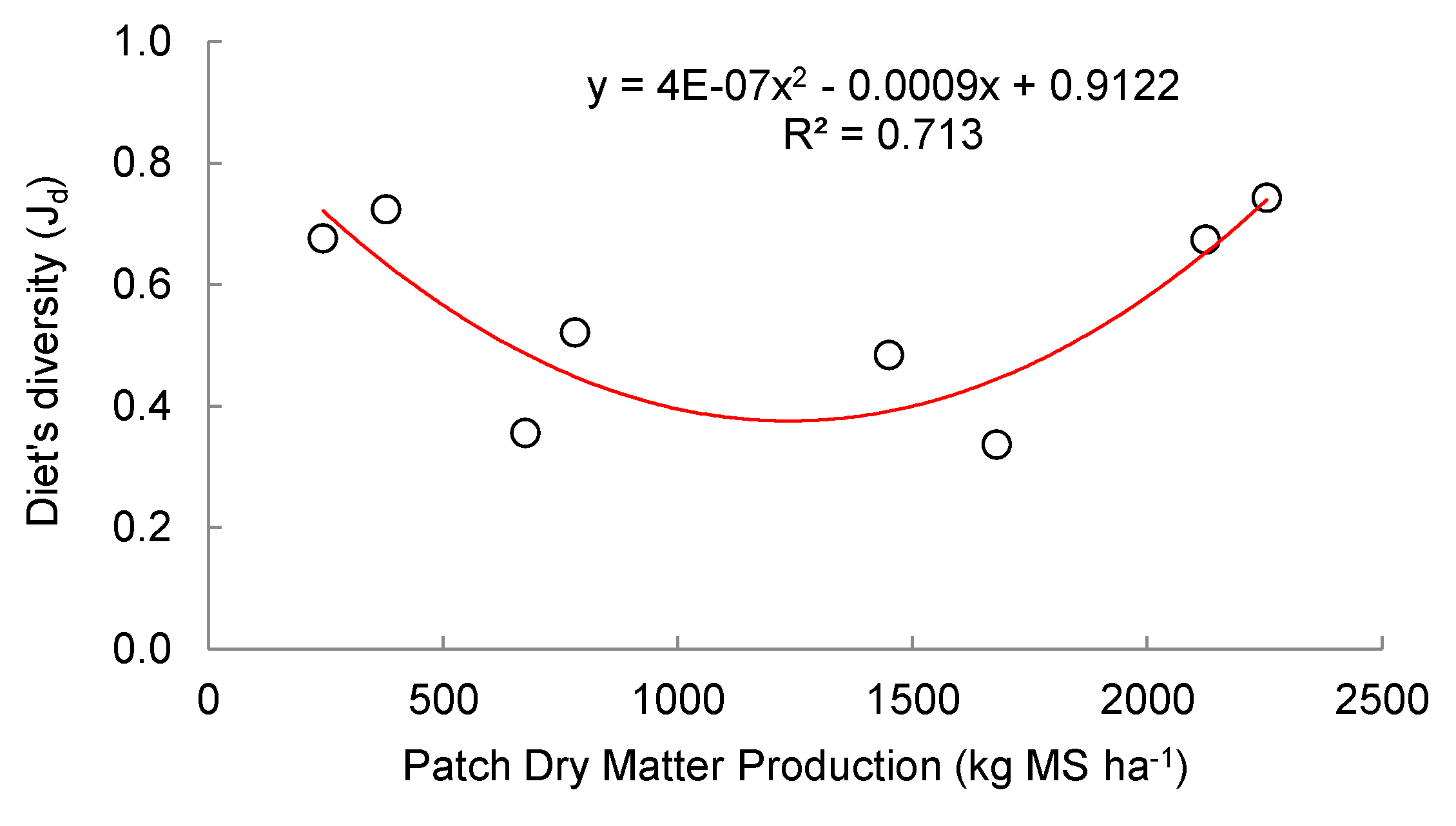

3.2. Diet Evenness and Its Relationship with Grassland Patch Evenness and Dry Matter Production

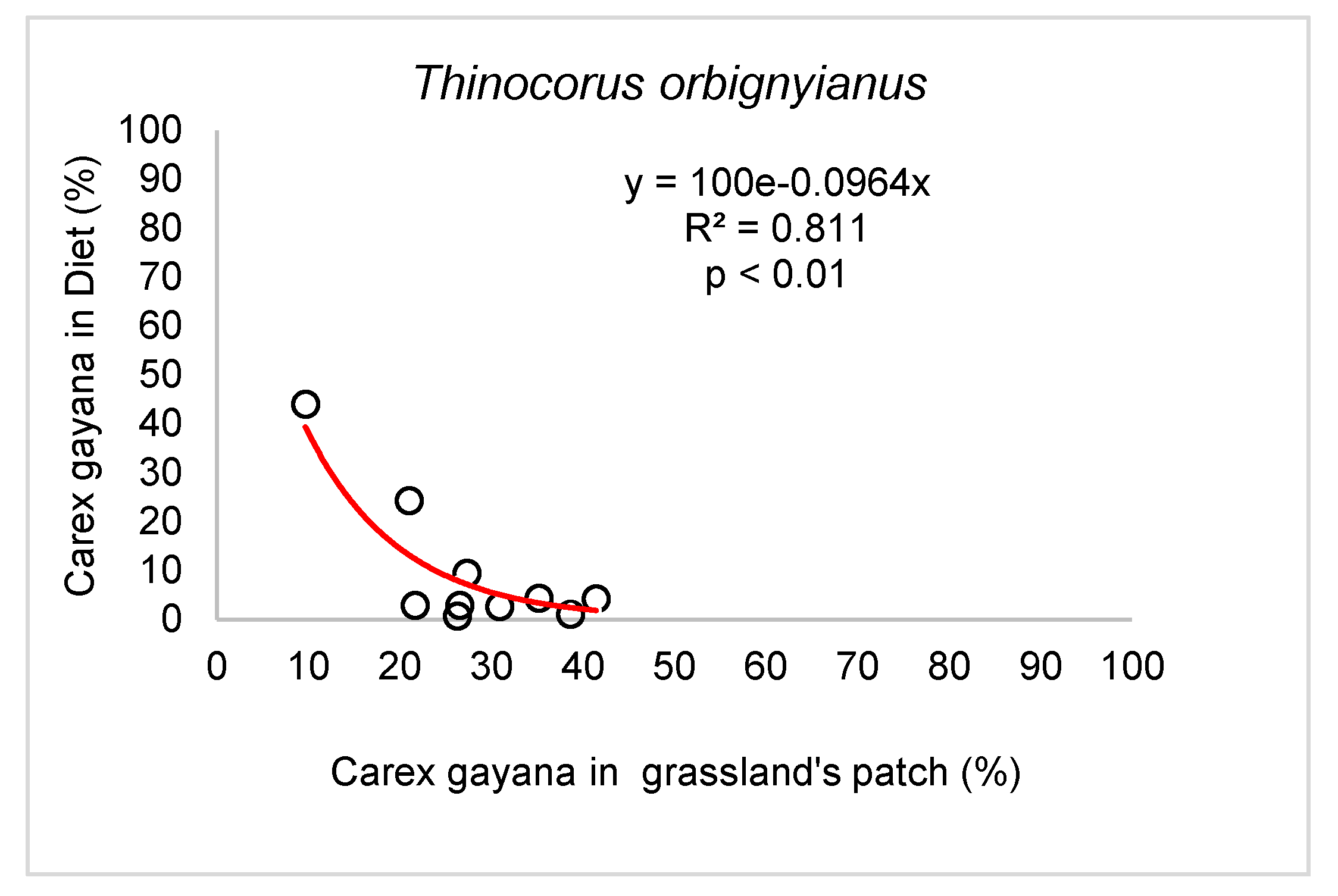

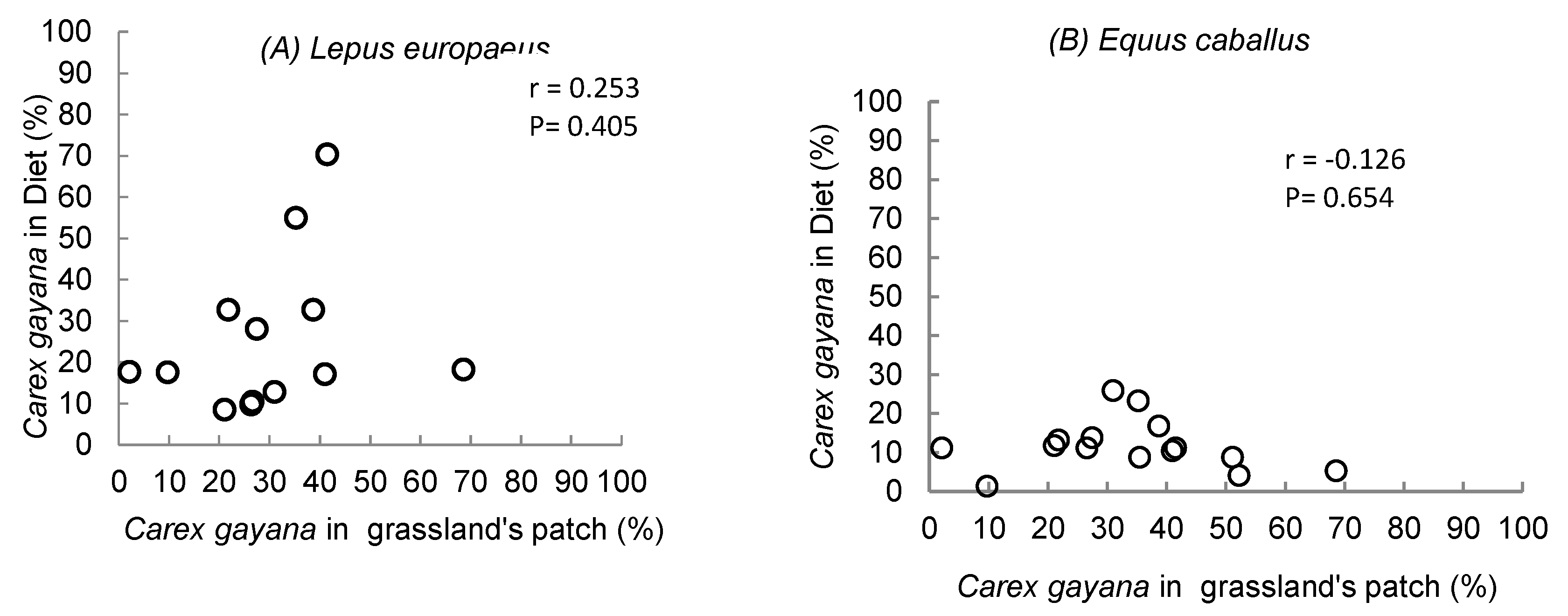

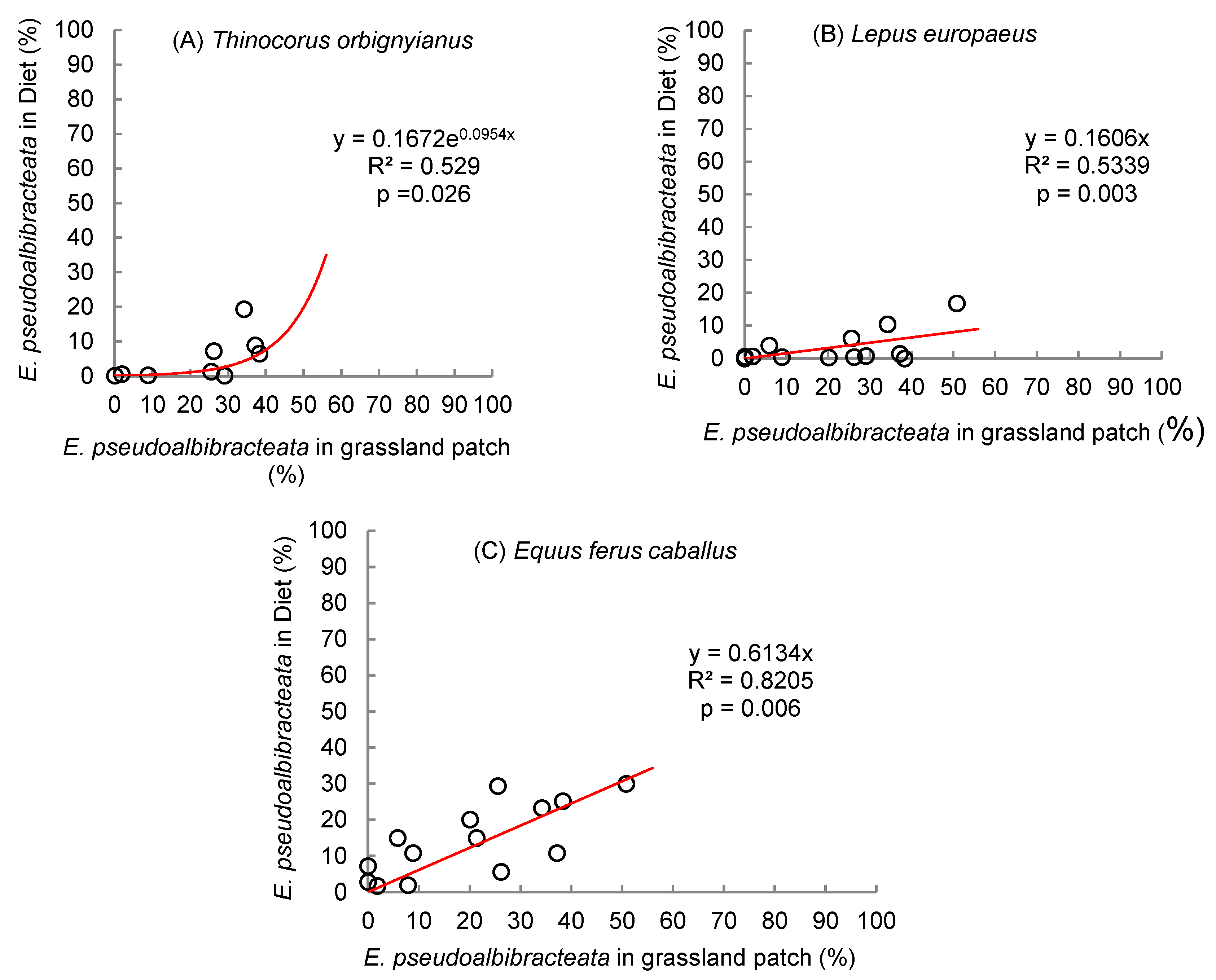

3.3. Presence of Indicator Plant Species in the Diet

3.4. Dietary Overlap

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahumada, M. y F m & l Faúndez (2001) Guía descriptiva de las praderas naturales de Chile. Ministerio de Agricultura, Servicio Agrícola y Ganadero, Santiago, Chile. 98 p.2.

- Chesson, P. and N. Huntly. The roles of harsh and fluctuating conditions in the dynamics of ecological communities. Am. Nat. 1997, 150, 519–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellaro, G.; Orellana, C.L.; Escanilla, J.P. 2021. Summer Diet of Horses (Equus ferus caballus Linn.) Guanacos (Lama guanicoe Müller), and European Brown Hares (Lepus europaeus Pallas) in the High Andean Range of the Coquimbo Region, Chile. Animals 2021, 11, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonino, N. Interacción trófica entre el conejo silvestre europeo y el ganado doméstico en el noroeste de la Patagonia Argentina. Ecol. Austral 2006, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Iranzo, E. 2011. Abundancia y selección de hábitat del guanaco (Lama guanicoe) en Torres del Paine (Chile): coexistencia con el ganado en el entorno de un espacio natural protegido. Tesis de Maestría en Ecología. Facultad de Biología. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, España.

- Guzmán, C. 1984. Estado actual de las veranadas de un sector de la comuna de San José de Maipo (Región Metropolitana) y su relación con el manejo histórico de la masa animal. Memoria para optar al título profesional de Ingeniero Agrónomo. Santiago, Universidad de Chile, Facultad de Ciencias Agronómicas. 95 p.

- García, J. and B. Arroyo. 2005. Food-niche differentiation in sympatric Hen Circus cyaneus and Montagu’s Harriers Circus pygargus. Ibis 2005, 147, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayneiro, R. 2000. Análisis del nicho trófico de tres especies de anfibios en un grupo de cuerpos de agua lénticos. Tesis de maestría en biología. Facultad de Ciencias. Universidad de la República, Montevideo. Uruguay.

- Fedriani, J. Fuller, R. Sauvajot and E. York. Competition and intraguild predation among three sympatric carnivores. Oecologia 2000, 125, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, W. 1984. A review of ecological studies relevant to management of the common brushtail possum. In Possums and gliders, ed. A. P. Smith & I. D. Hume. Surrey Beatty & Sons, Chipping Norton, NSW, pp. 483-99.

- Linares, L. Linares, G. Mendoza, F. Pelaez, E. Rodriguez y A. Phum. 2010. Preferencias alimenticias del guanaco (Lama guanicoe cacsilensis) y su competencia con el ganado doméstico en la Reserva Nacional de Calipuy, Perú. Scientia Agropecuaria 2010, 1, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köeppen, W. Climatología; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Carretera Picacho-Ajusco, Mexico, 1948; p. 478. [Google Scholar]

- Passera, C. B. , Dalmasso, A. D. and O. Borsetto. 1983. Método de “Point Quadrat Modificado”. In Taller de Arbustos Forrajeros para Zonas Áridas y Semiáridas, 2nd ed. Subcomité Asesor del Árido Subtropical Argentino. Amawald. S. A.: Buenos Aires, Argentina, p. 107.

- Daget, PH. et J. Poissonet. Une méthode d’analyse phytologique des prairies, critères d’application. Ann. Agron 1971, 22, 5–41. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R. y T. Smith. 2012. Elements of Ecology., 8th Ed. Pearson Educación. Boston, USA. 612 p.

- Pielou, 1974. Population and community ecology: principles and methods. New York (NY): Gordon and Breach.

- Spark, D. and J. Malechek. Estimating percentage dry weight in diets using a microscope technique. J. Range Management 1968, 21, 264–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holechek, J. L. , Pieper, R.D. and C. H. Herbel. 2011. Range Management, Principles and Practices. 6th Edition. Prentice Hall, New Jersey. 444 p.

- Garnick, S. S. Barboza, and J. W Walker. 2018. Assessment of Animal-Based Methods Used for Estimating and Monitoring Rangeland Herbivore Diet Composition. Rangeland Ecology & Management 2018, 71, 449–457. [Google Scholar]

- Castellaro, G. Squella, T. Ullrich, F. Leon y A Raggi. Algunas técnicas microhistológicas utilizadas en la determinación de la composición botánica de la dieta de herbívoros. Agricultura Técnica (CHILE) 2007, 67, 86–93. [Google Scholar]

- Catán, A., C. Degano y L. Larcher. 2003. Modificaciones a la técnica microhistológica de Peña-Neira para especies forrajeras del Chaco Argentino. Quebracho. Revista de Ciencias Forestales. Diciembre Nº 010. Universidad Nacional de Santiago del Estero. Santiago del Estero, Argentina, pp. 71-75.

- Holechek, J. and B. Gross. Evaluation of different calculation procedures for microhistological analysis. J. Range Management 1982, 35, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, I., M. Berger y M. Flores. 1993. Manual de técnica microhistológica. 48 p. IBTA 113/Textos y Manuales 04/Rumiantes Menores (SR-CRSP) 05/ 1993. La Paz, Bolivia.

- Krebs, C. 1999. Ecologycal methodology. Addison Wesley Longman, Inc., CA., USA. 620 pp.

- Román-Palacios, C. and C. Román-Valencia. Hábitos tróficos de dos especies sintópicas de carácidos en una quebrada de alta montaña en los Andes colombianos. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 2015, 86, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianka, E. R. The structure of lizard communities. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 1973, 4, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaps, M.; Lamberson, Y.W. Biostatistics for Animal Science; CABI Publishing: Oxfordshire, UK, 2004; 445p. [Google Scholar]

- Schoener, T. Field experiments on interspecific competition. The American Naturalist. 1983, 122, 240–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, D. y M. Dacar. Composición de la dieta de la mara (Dolichotis patagonum) en el sudeste del monte pampeano (La Pampa, Argentina). Mastozoología Neotropical 2008, 15, 215–220. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, I. and W. Lindsay. Could mammalian herbivores “manage” their resources. Oikos 1990, 59, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzun, L. , Érard, C. , Gasc, J. P. and Dzerzhinsky, F. Adaptation of seedsnipes (Aves, Charadriiformes, Thinocoridae) to browsing: a study of their feeding apparatus. Zoosystema 2009, 31, 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loiselle, A. and J. Blake. Diets of understory fruit-eating birds in Costa Rica: Seasonality and resource abundance. Vegetatio 1990, 107/108, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, C. , Castellaro, G. and Escanilla, J. Dieta estival del piuquén (Chloephaga melanoptera Eyton, 1838) en praderas hidromórficas de la Cordillera Andina de la Región de Coquimbo, Chile. IDESIA (Chile). 2021, 39, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, D. 1993. El rumiante: fisiología digestiva y nutrición de los rumiantes. Zaragoza, España: Editorial Acribia.

- Cheeke, P.R.; Dierendfeld, E.S. Comparative Animal Nutrition and Metabolism; CABI: Carson, CA, USA, 2010; 339p. [Google Scholar]

- Granado-Lorecio, C. 2002. Ecología de peces. Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, España.

- Abrams P Some comments on meosuring niche overlap. Ecology 1980, 61, 44–49. [CrossRef]

- Allen, J. Raison and M. Weale. The influence ofdensity on frequency-dependent selection by wild birds feeding on artificial prey. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 1998, 265, 1031–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J. and M. Weale. Anti-apostatic selection by wild birds on quasi-natural morphs of the land snail Cepaea hortensis: a generalised linear mixed models approach. 2005, 108, 335–343. [Google Scholar]

- DeCesare, N. Hebblewhite, H. Robinson and M. Musiani. Endangered, apparently: the role of apparent competition in endangered species conservation. 2010, 13, 353–362. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth, D. Coomes, G. Nugentg and M. Hall. Diet and diet references of introduced ungulates (Order: Artiodactyla) in New Zealand. 2000, 29, 323–343. [Google Scholar]

- Endler, J.A. Frequency-dependent predation, crypsis andaposematic colorations. Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. Lond. B 1988, 319, 505–523. [Google Scholar]

| Plant species |

NDF (%) |

ADF (%) |

CP (%) |

DMD (%) |

ME (MJ kg-1) |

| C. gayana | 55.89 | 26.52 | 8.89 | 68.24 | 10.03 |

| E. pseudoalbibracteata | 50.48 | 30.70 | 8.63 | 64.98 | 9.47 |

| Herbivore species | Thinocorum orbignyianus | Lepus europaeus | Equus ferus caballus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thinocorus orbignyianus | --- | 0.397 | 0.328 |

| Lepus europaeus | 0.397 | --- | 0.303 |

| Equus ferus caballus | 0.328 | 0.303 | --- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).