Submitted:

22 May 2025

Posted:

23 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

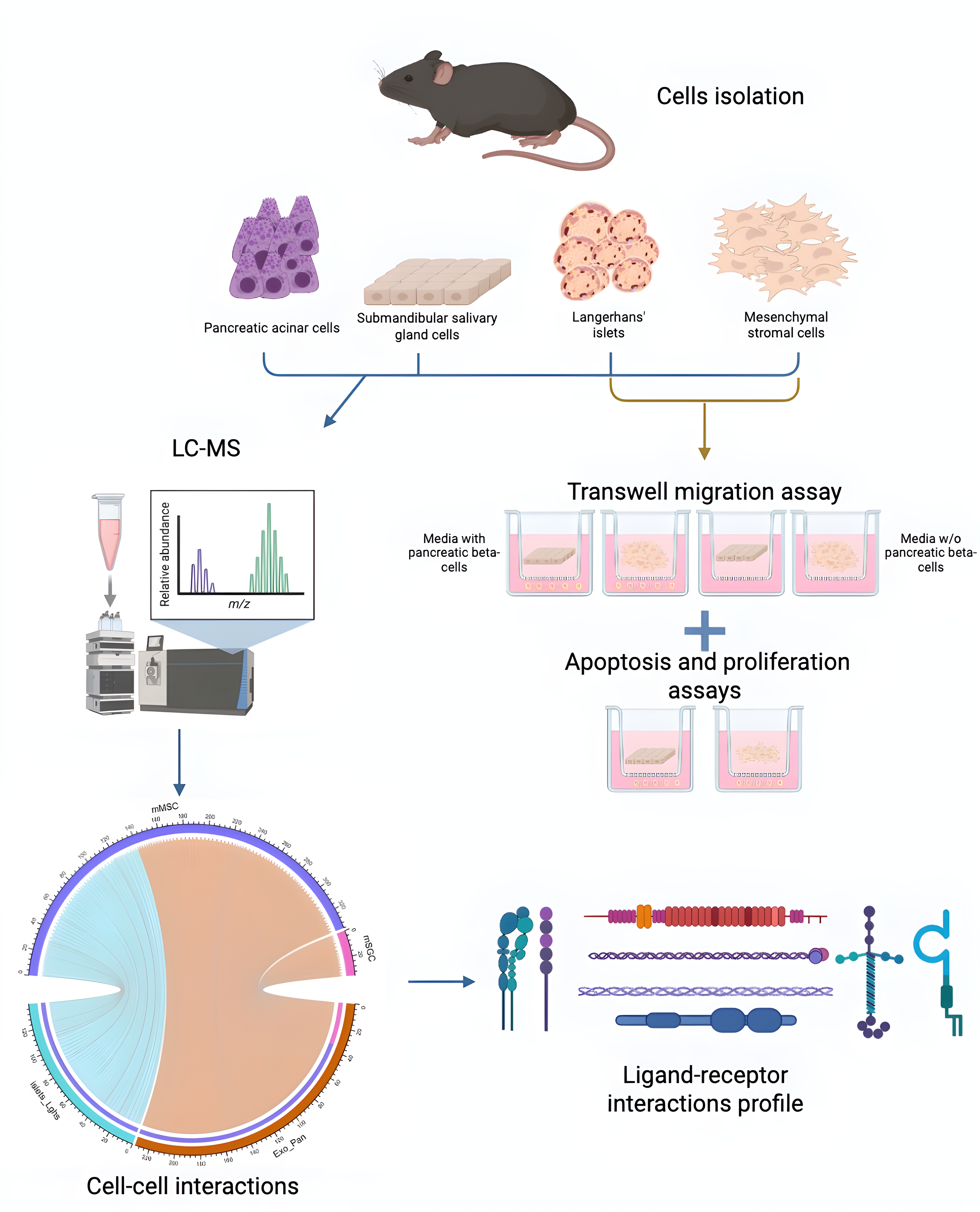

1. Introduction

- Analysis of the migration potential of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) and salivary gland cells (SGCs) towards pancreatic cells;

- Evaluation of proliferation and apoptosis levels in pancreatic cells under the influence of MSCs and SGCs;

- Identification of ligand-receptor interaction patterns involved in the formation of interactions between MSCs and pancreatic cells, and between SGCs and pancreatic cells;

- Identification of key signaling pathways involved in ligand-receptor interactions between MSCs, SGCs, and pancreatic cells.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Experimental Procedures

2.2. Isolation and Cultivation of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells from Mouse Adipose Tissue

2.3. Isolation and Culture of Mouse SGCs

2.4. Passaging of MSCs and SGCs

2.5. Boyden Chamber Assay

2.6. Analysis of the Effects of MSCs and SGCs on Proliferation

2.7. Immunocytochemical Analysis

2.8. Determination of DNA Fragmentation by Labeling DNA Fragments Using Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase and dUTP

2.9. Proteomic Analysis

2.10. Bioinformatics Analysis of Proteome Data

3. Results

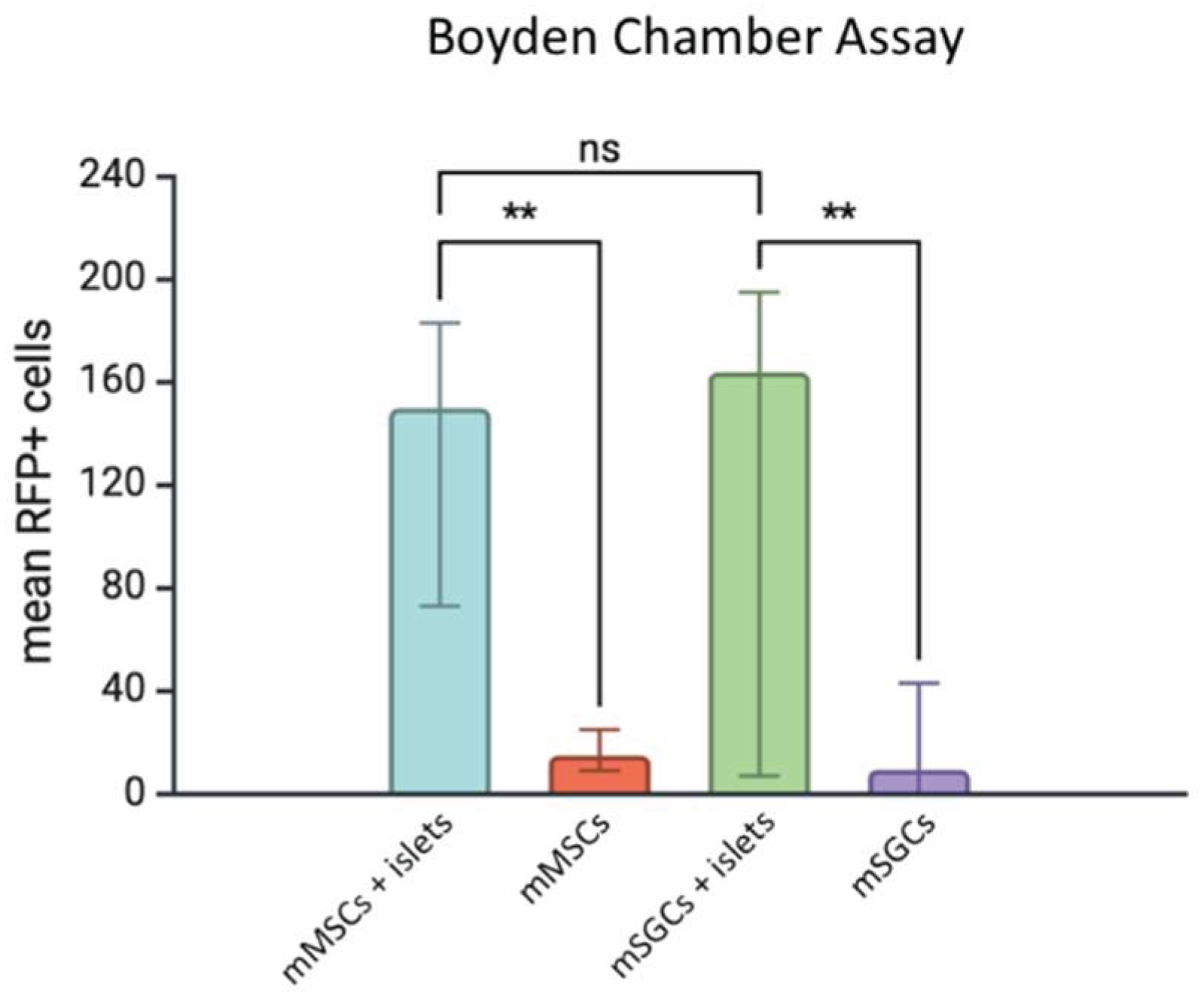

3.1. Analysis of SGC and MSC Migration Under the Influence of the Langerhans Islet Secretome

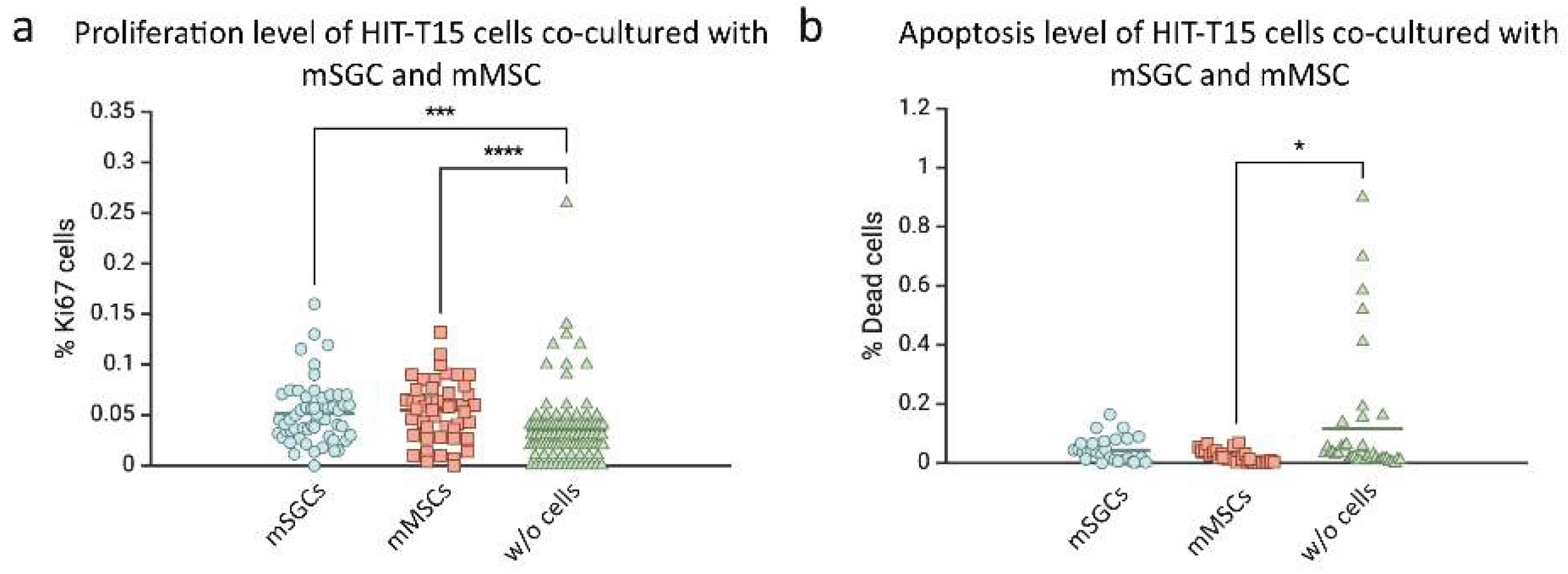

3.2. Influence of SGCs and mMSCs on the Proliferation and Apoptosis of HIT-T15 β-Cells

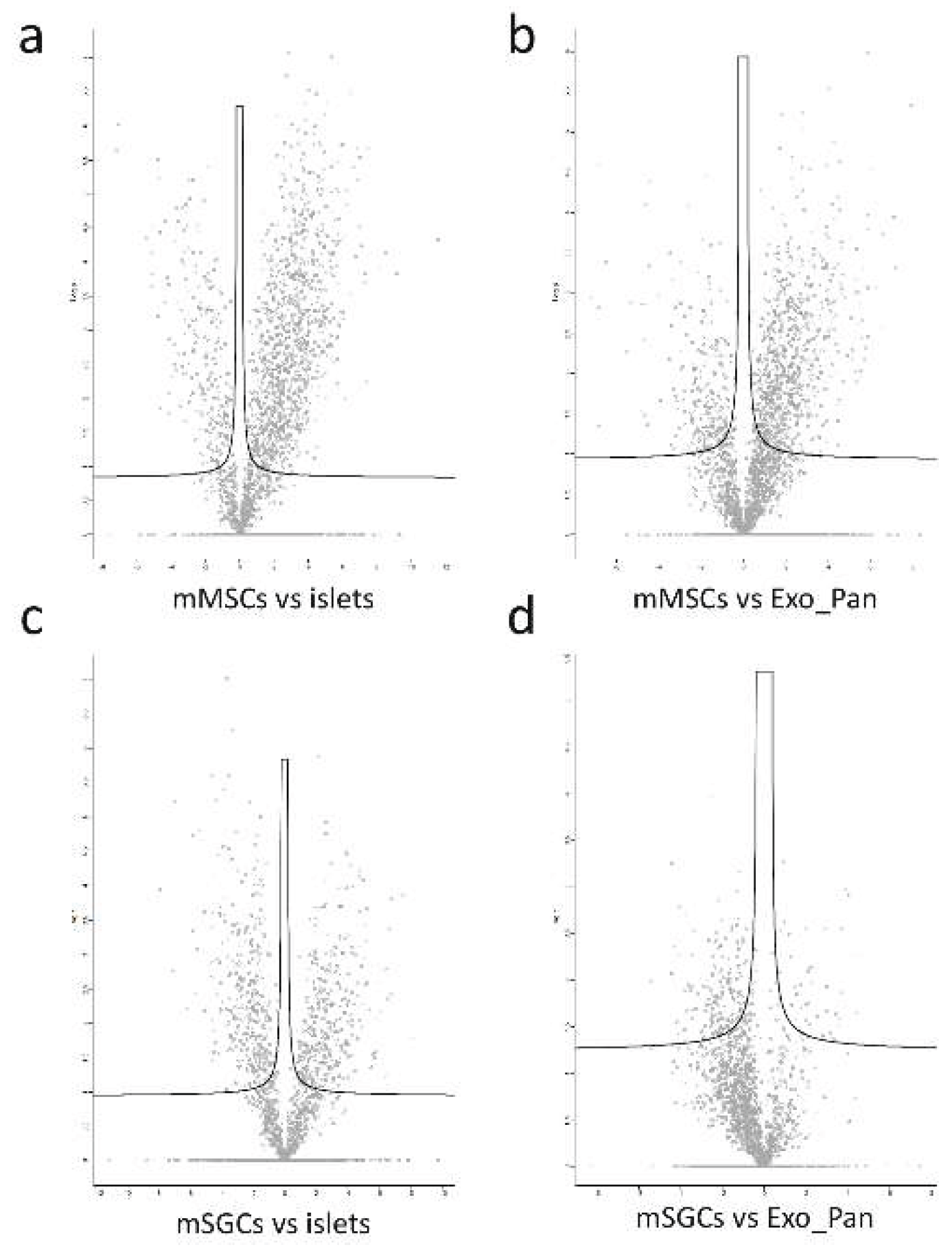

3.3. Proteomic Analysis of Intercellular Interactions Between SGCs, MSCs, and Pancreatic Cells

3.3.1. Volcano Plots and Functional Enrichment Analysis

3.3.2. Identification of Key Proteins Involved in Intercellular Communication

3.3.3. Functional Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) of mMSCs

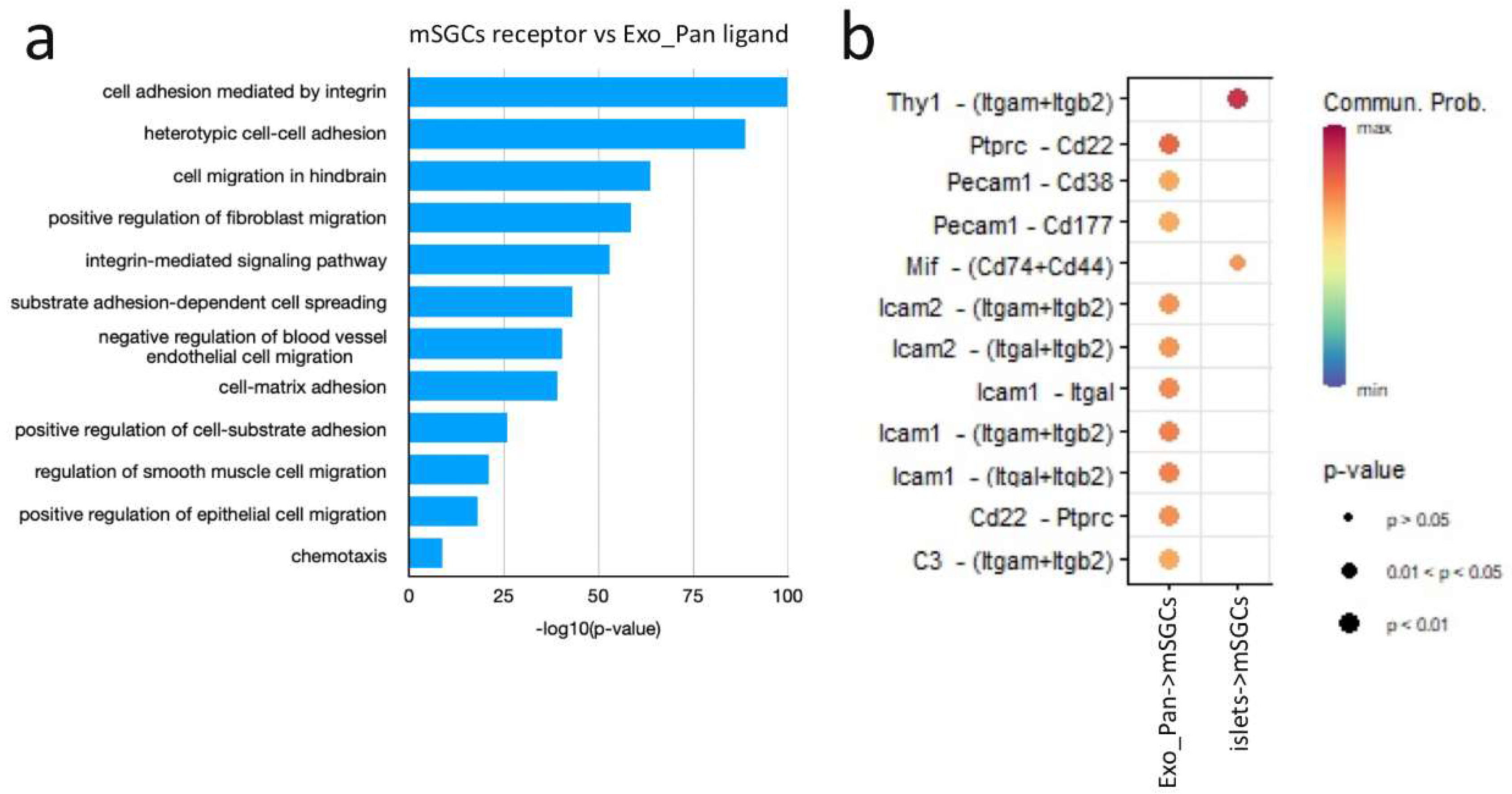

3.4. Functional Enrichment Analysis of mSGCs

3.4.1. Similarities and Differences in mMSC and mSGC Protein Patterns

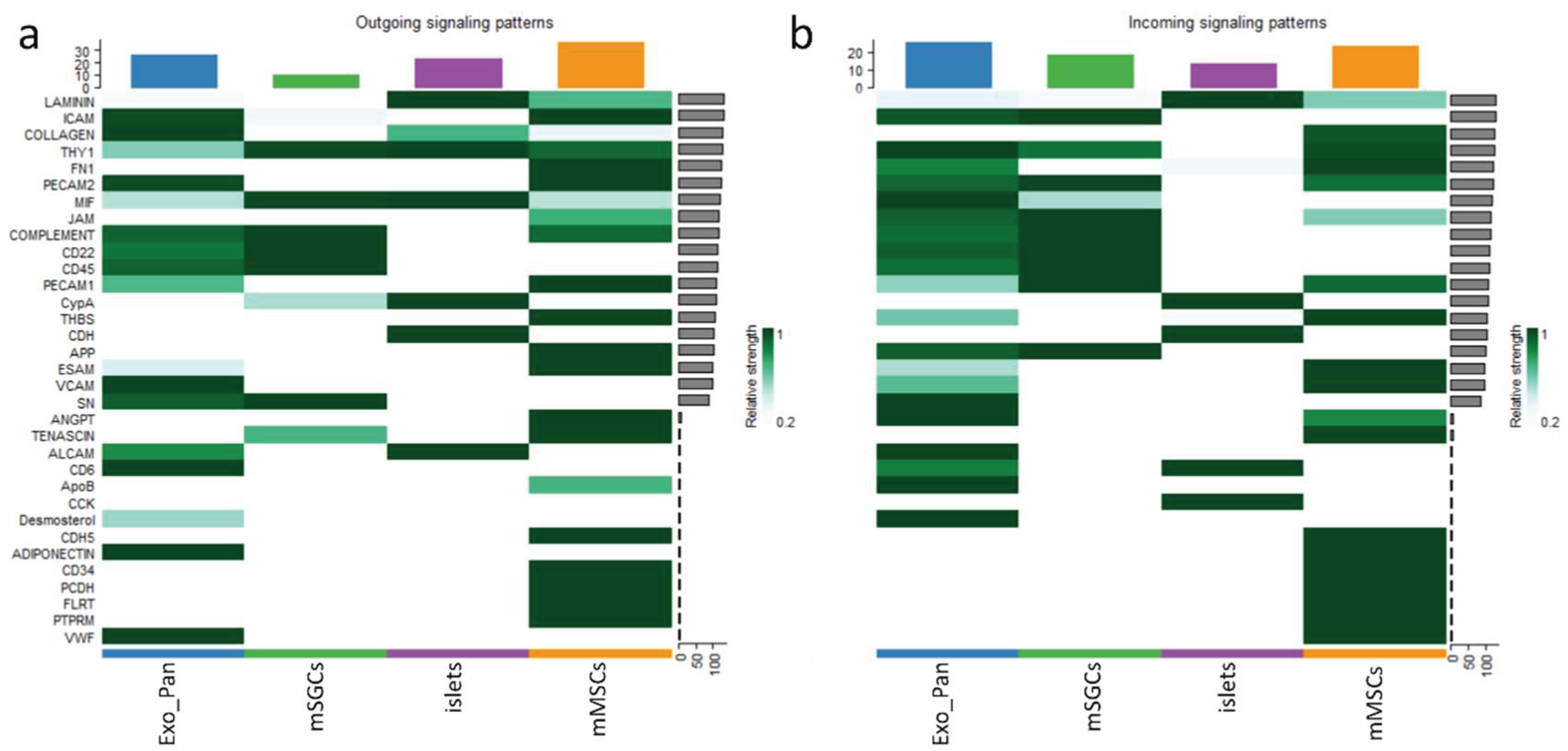

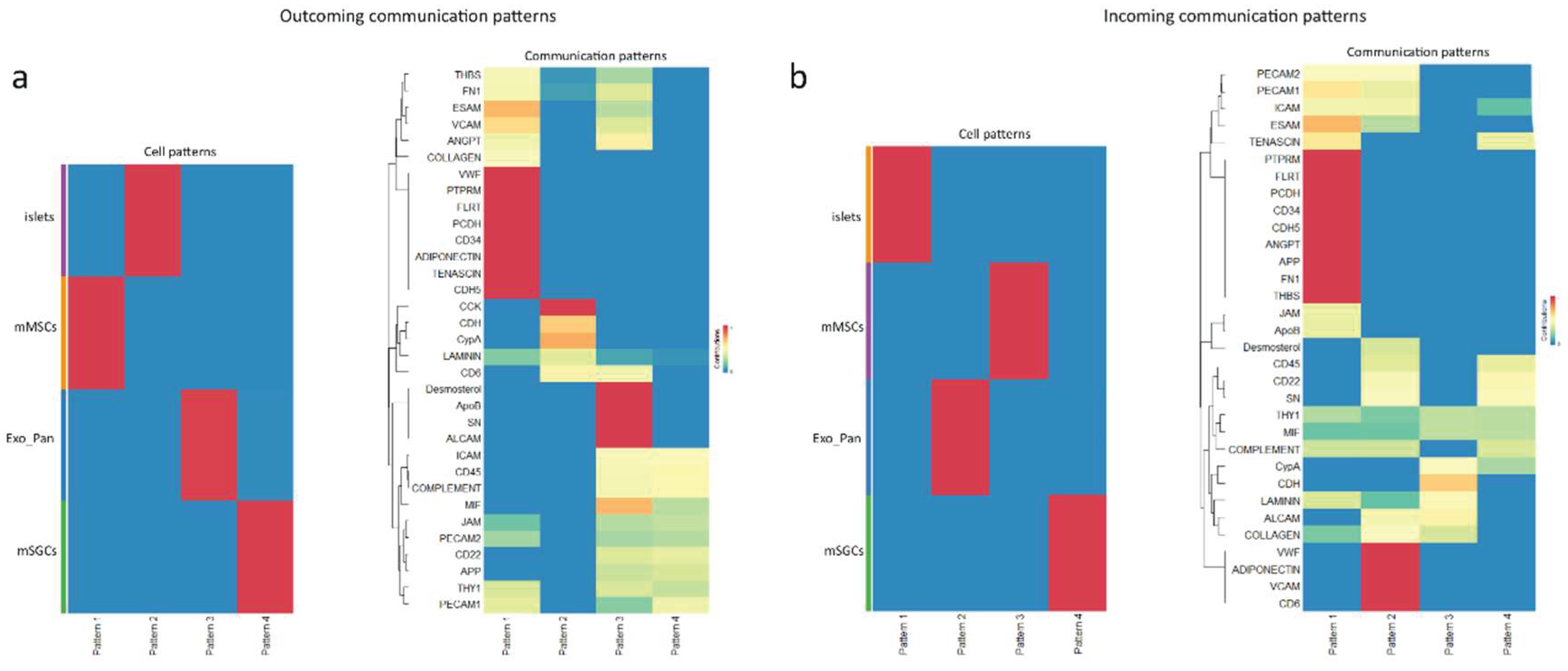

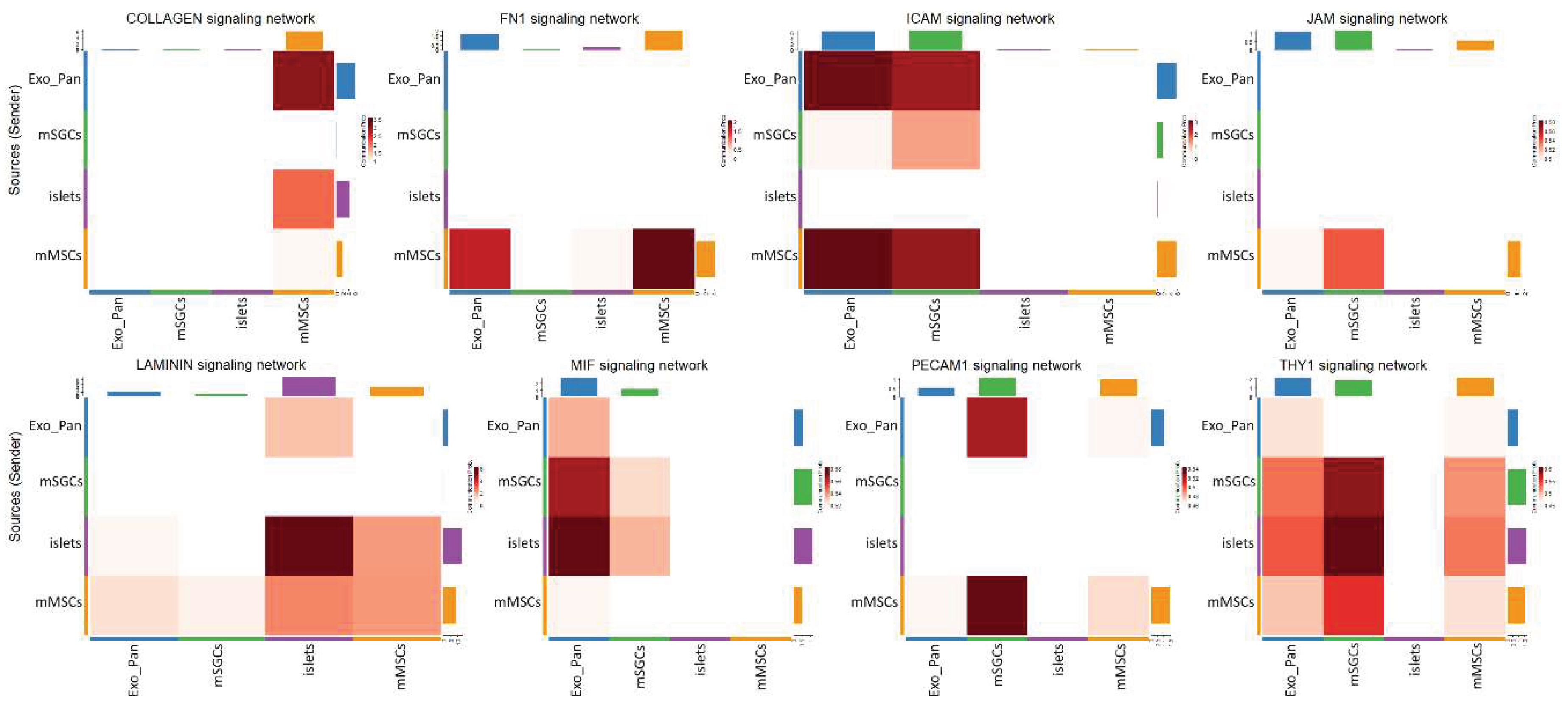

3.4.2. Cell-Cell Interaction Patterns Across Different Roles

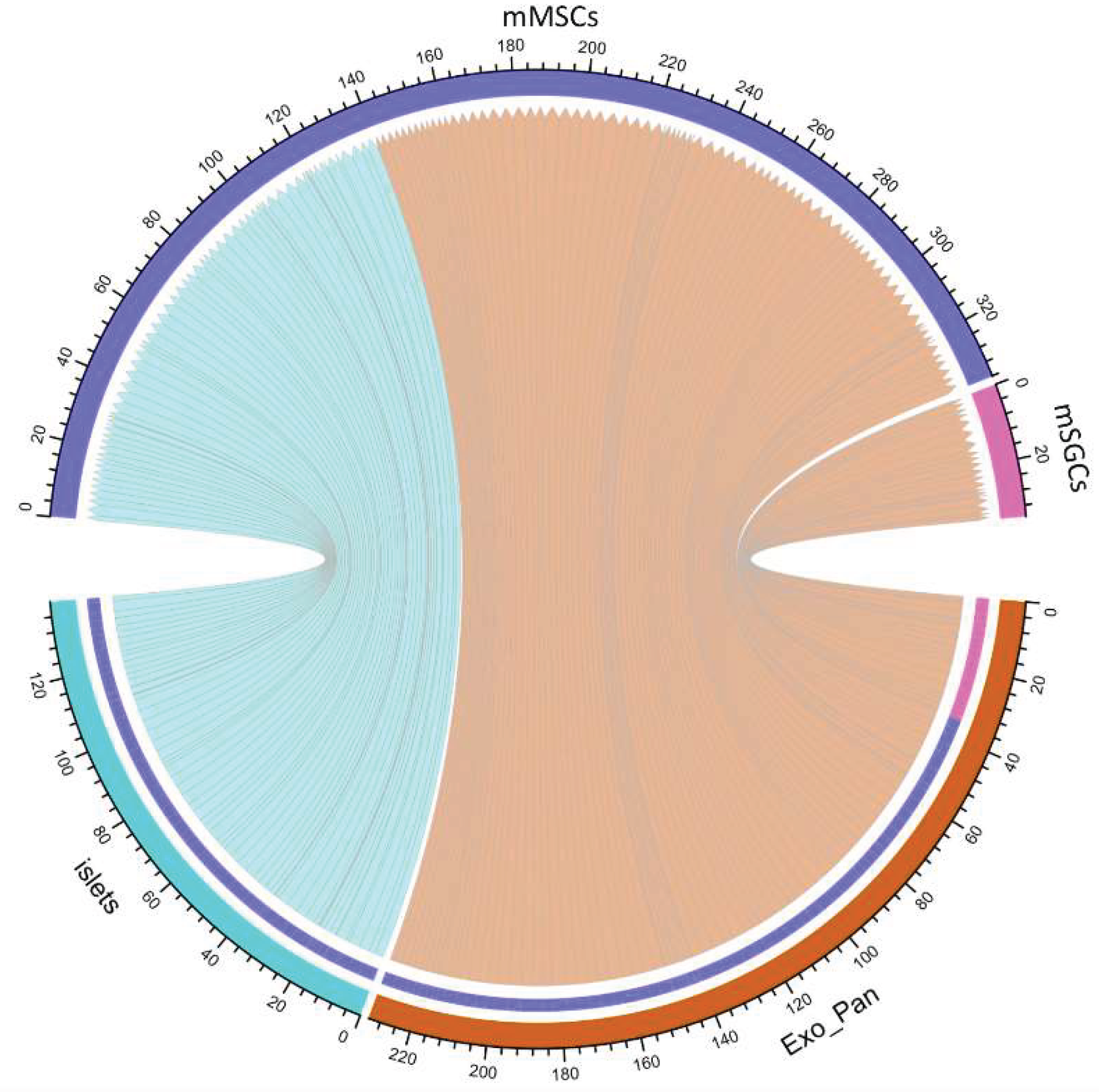

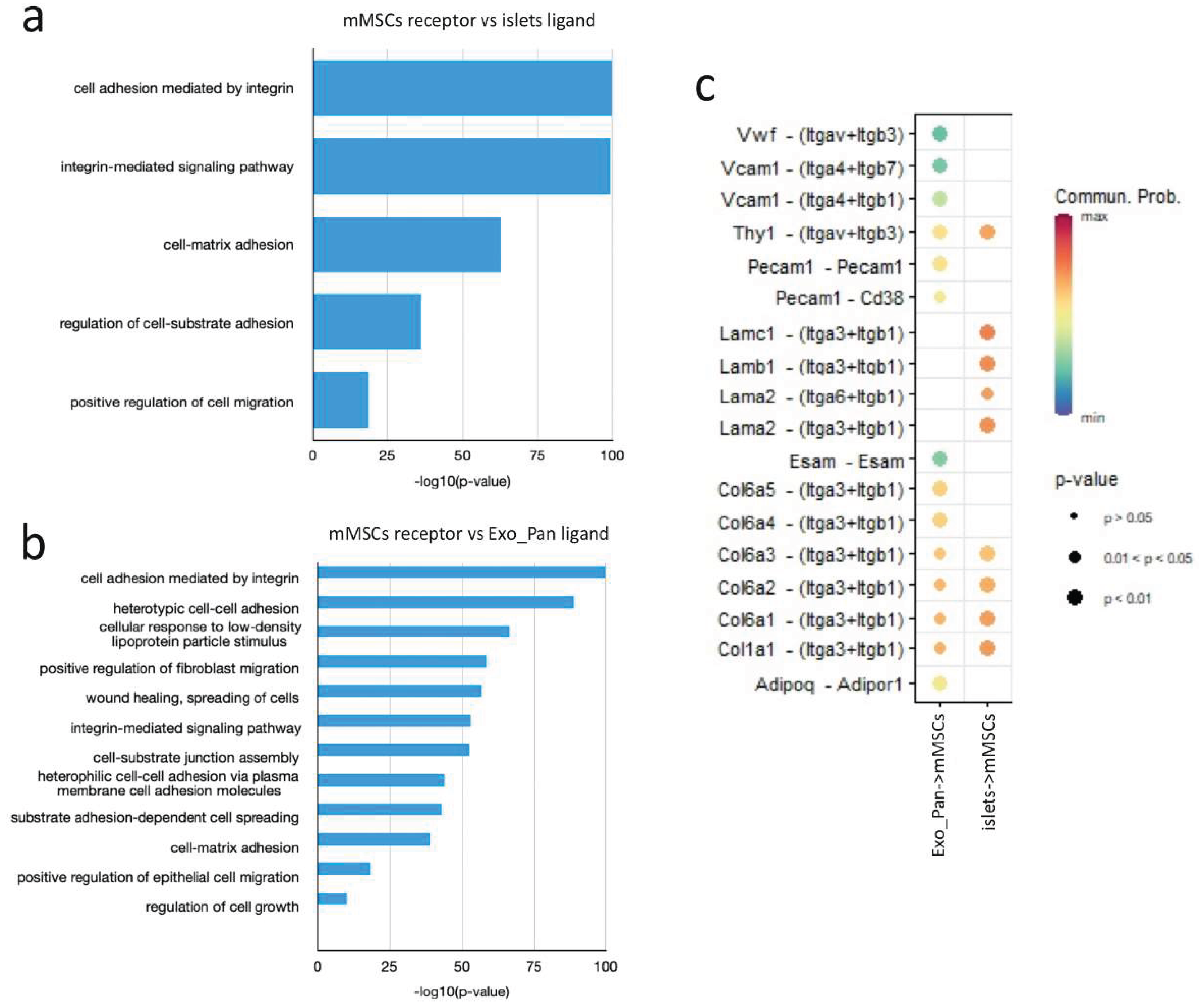

3.4.3. The Role of mMSCs in Intercellular Interactions

4. Discussion

4.1. Migration Properties of SGCs and MSCs Under the Influence of the Langerhans Islet Secretome

4.1.1. Effect of SGCs and MSCs on the Proliferation and Apoptosis of HIT-T15 β-Cells

4.2. Proteomic Analysis

4.2.1. Protein Patterns Involved in the Interaction Between MSCs and Islets of Langerhans

4.2.2. Key Proteins Involved in the Interactions Between MSCs and Exocrine Cells of the Pancreas

4.2.3. Interactions Between SGCs and Islets of Langerhans

4.2.4. SGC Interaction with the Exocrine Pancreas

4.2.5. Signaling Pathways

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

| MSCs | Mesenchymal stromal cells |

| SGCs | Salivary gland cells |

| iPSCs | Induced pluripotent stem cells |

| MODY | Maturity-onset diabetes of the young |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| GSEA | Gene Set Enrichment Analysis |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| FC | Flow cytometry |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| Exo_Pan | Exocrine pancreas |

| FN1 | Fibronectin-1 |

References

- Katsarou, A.; Gudbjörnsdottir, S.; Rawshani, A.; Dabelea, D.; Bonifacio, E.; Anderson, B.J.; Jacobsen, L.M.; Schatz, D.A.; Lernmark, Å. Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017, 3, 17016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, N. Disease Pathways: An Atlas of Human Disease Signaling Pathways by Anastasia Nesterova, Anton Yuryev, Eugene Klimov, Maria Zharkova, Maria Shkrob, Natalia Ivanikova, Sergey Sozin and Vladimir Sobolev. The Biochemist 2020, 42, 140–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, F.; Liu, W.; Ren, Y.; Tian, Y.; Shi, W.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Qian, L. β-Cell Neogenesis: A Rising Star to Rescue Diabetes Mellitus. Journal of Advanced Research 2024, 62, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spears, E.; Serafimidis, I.; Powers, A.C.; Gavalas, A. Debates in Pancreatic Beta Cell Biology: Proliferation Versus Progenitor Differentiation and Transdifferentiation in Restoring β Cell Mass. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 722250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guney, M.A.; Lorberbaum, D.S.; Sussel, L. Pancreatic β Cell Regeneration: To β or Not to β. Current Opinion in Physiology 2020, 14, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldovieri, L.; Di Giuseppe, G.; Ciccarelli, G.; Quero, G.; Cinti, F.; Brunetti, M.; Nista, E.C.; Gasbarrini, A.; Alfieri, S.; Pontecorvi, A.; et al. An Update on Pancreatic Regeneration Mechanisms: Searching for Paths to a Cure for Type 2 Diabetes. Molecular Metabolism 2023, 74, 101754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Huang, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhao, X.; Sun, Y.; Mao, X.; Li, S. Pancreatic Islet Transplantation: Current Advances and Challenges. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1391504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parums, D.V. Editorial: First Regulatory Approval for Allogeneic Pancreatic Islet Beta Cell Infusion for Adult Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Med Sci Monit 2023, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.S.; Shim, S.; Kudo, Y.; Stabler, C.L.; O’Cearbhaill, E.D.; Karp, J.M.; Yang, K. Encapsulated Islet Transplantation. Nat Rev Bioeng 2024, 3, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Gao, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. The Progress of Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Pancreatic β-Cells Regeneration for Diabetic Therapy. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 927324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Zhang, T.; Lu, A.; Shiota, C.; Huard, M.; Whitney, K.E.; Huard, J. Specific Reprogramming of Alpha Cells to Insulin-Producing Cells by Short Glucagon Promoter-Driven Pdx1 and MafA. Molecular Therapy - Methods & Clinical Development 2023, 28, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Sugiyama, T.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Gu, X.; Lei, J.; Markmann, J.F.; Miyazaki, S.; Miyazaki, J.; Szot, G.L.; et al. Expansion and Conversion of Human Pancreatic Ductal Cells into Insulin-Secreting Endocrine Cells. eLife 2013, 2, e00940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontcuberta-PiSunyer, M.; García-Alamán, A.; Prades, È.; Téllez, N.; Alves-Figueiredo, H.; Ramos-Rodríguez, M.; Enrich, C.; Fernandez-Ruiz, R.; Cervantes, S.; Clua, L.; et al. Direct Reprogramming of Human Fibroblasts into Insulin-Producing Cells Using Transcription Factors. Commun Biol 2023, 6, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, N.H.J.; Ghosh, S.; Bok, C.M.; Ching, C.; Low, B.S.J.; Chen, J.T.; Lim, E.; Miserendino, M.C.; Tan, Y.S.; Hoon, S.; et al. HNF4A and HNF1A Exhibit Tissue Specific Target Gene Regulation in Pancreatic Beta Cells and Hepatocytes. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Cherkaoui, I.; Misra, S.; Rutter, G.A. Functional Genomics in Pancreatic β Cells: Recent Advances in Gene Deletion and Genome Editing Technologies for Diabetes Research. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 576632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berishvili, E.; Peloso, A.; Tomei, A.A.; Pepper, A.R. The Future of Beta Cells Replacement in the Era of Regenerative Medicine and Organ Bioengineering. Transpl Int 2024, 37, 12885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, S.; Coenen, S.; Degroote, L.; Willems, L.; Van Mulders, A.; Pierreux, J.; Heremans, Y.; De Leu, N.; Staels, W. Harnessing Beta Cell Regeneration Biology for Diabetes Therapy. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 2024, 35, 951–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrojo E Drigo, R.; Ali, Y.; Diez, J.; Srinivasan, D.K.; Berggren, P.-O.; Boehm, B.O. New Insights into the Architecture of the Islet of Langerhans: A Focused Cross-Species Assessment. Diabetologia 2015, 58, 2218–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottet Dumoulin, D.; Fonseca, L.M.; Bignard, J.; Hanna, R.; Parnaud, G.; Lebreton, F.; Bellofatto, K.; Berishvili, E.; Berney, T.; Bosco, D. Identification of Newly Synthetized Proteins by Mass Spectrometry to Understand Palmitate-Induced Early Cellular Changes in Pancreatic Islets. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, 0019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieland, F.C.; Van Blitterswijk, C.A.; Van Apeldoorn, A.; LaPointe, V.L.S. The Functional Importance of the Cellular and Extracellular Composition of the Islets of Langerhans. Journal of Immunology and Regenerative Medicine 2021, 13, 100048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibly, A.M.; Aure, M.H.; Patel, V.N.; Hoffman, M.P. Salivary Gland Function, Development, and Regeneration. Physiological Reviews 2022, 102, 1495–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.F.; Shen, Y.Y.; Zhang, M.C.; Lv, M.C.; Wang, T.Y.; Chen, X.Q.; Lin, J. Progress in Salivary Glands: Endocrine Glands with Immune Functions. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1061235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiffon, C. Defining Parallels between the Salivary Glands and Pancreas to Better Understand Pancreatic Carcinogenesis. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangsuriyothai, P.; Watari, I.; Serirukchutarungsee, S.; Satrawaha, S.; Podyma-Inoue, K.A.; Ono, T. Expression of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 and Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide in the Rat Submandibular Gland Is Influenced by Pre- and Post-Natal High-Fat Diet Exposure. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1357730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.-B.; Chen, Z.-B.; Li, B.-C.; Lin, Q.; Li, X.-X.; Li, S.-L.; Ding, C.; Wu, L.-L.; Yu, G.-Y. Expression of Ghrelin in Human Salivary Glands and Its Levels in Saliva and Serum in Chinese Obese Children and Adolescents. Archives of Oral Biology 2011, 56, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahakian, B.J.; Lean, M.E.J.; Robbins, T.W.; James, W.P.T. Salivation and Insulin Secretion in Response to Food in Non-Obese Men and Women. Appetite 1981, 2, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pasquale, G.; Dicembrini, I.; Raimondi, L.; Pagano, C.; Egan, J.M.; Cozzi, A.; Cinci, L.; Loreto, A.; Manni, M.E.; Berretti, S.; et al. Sustained Exendin-4 Secretion through Gene Therapy Targeting Salivary Glands in Two Different Rodent Models of Obesity/Type 2 Diabetes. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowzee, A.M.; Perez-Riveros, P.J.; Zheng, C.; Krygowski, S.; Baum, B.J.; Cawley, N.X. Expression and Secretion of Human Proinsulin-B10 from Mouse Salivary Glands: Implications for the Treatment of Type I Diabetes Mellitus. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beucler, M.J.; Miller, W.E. Isolation of Salivary Epithelial Cells from Human Salivary Glands for In Vitro Growth as Salispheres or Monolayers. JoVE 2019, 59868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouani, M.; Basset, C.A.; Jurjus, A.R.; Leone, L.G.; Tomasello, G.; Leone, A. Salivary Gland Proteins Alterations in the Diabetic Milieu. J Mol Histol 2021, 52, 893–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Sun, Y.; Wu, F.; Xu, W.; Qian, H. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: A Potential Therapy for Diabetes Mellitus and Diabetic Complications. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, O.I.; Kamal, M.M.; El-Maraghy, S.A.; Ghaiad, H.R. The Effect of Diabetes Mellitus on Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells into Insulin-Producing Cells. Biol Res 2024, 57, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habiba, U.E.; Khan, N.; Greene, D.L.; Ahmad, K.; Shamim, S.; Umer, A. Meta-Analysis Shows That Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy Can Be a Possible Treatment for Diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1380443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z.T.; Zain Al-Abeden, M.S.; Al Abdin, M.G.; Muqresh, M.A.; Al Jowf, G.I.; Eijssen, L.M.T.; Haider, K.H. Dose-Response Relationship of MSCs as Living Bio-Drugs in HFrEF Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of RCTs. Stem Cell Res Ther 2024, 15, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Zhang, M.; Tao, E.; Wang, J.; Wei, N.; Lu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Hao, K.; Zhou, F.; Wang, G. Pharmacokinetic Characteristics of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Translational Challenges. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Yang, J.; Fang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Candi, E.; Wang, J.; Hua, D.; Shao, C.; Shi, Y. The Secretion Profile of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Potential Applications in Treating Human Diseases. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Song, L.; Strange, C.; Dong, X.; Wang, H. Therapeutic Effects of Adipose Stem Cells from Diabetic Mice for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes. Molecular Therapy 2018, 26, 1921–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawada-Horitani, E.; Kita, S.; Okita, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Nishida, H.; Honma, Y.; Fukuda, S.; Tsugawa-Shimizu, Y.; Kozawa, J.; Sakaue, T.; et al. Human Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Prevent Type 1 Diabetes Induced by Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Diabetologia 2022, 65, 1185–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Liu, J.; Li, X. Therapeutic Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) in Diabetic Kidney Disease (DKD). Endocr J 2022, 69, 1159–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, R.; Mazurek, S.; Petry, S.F.; Linn, T. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promote Pancreatic β-Cell Regeneration through Downregulation of FoxO1 Pathway. Stem Cell Res Ther 2020, 11, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; He, Z.; Huang, D.; Gao, J.; Gong, Y.; Wu, H.; Xu, A.; Meng, X.; Li, Z. Infusion of Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells Attenuates Experimental Severe Acute Pancreatitis in Rats. Stem Cells International 2016, 2016, 7174319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, R.; Wan, Z.; Yang, C.; Shen, X.; Wang, R.; Zhang, H.; Yang, R.; Li, J.; Song, Y.; Su, H. Advances and Clinical Challenges of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1421854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, O.; Kuai, R.; Siren, E.M.J.; Bhere, D.; Milton, Y.; Nissar, N.; De Biasio, M.; Heinelt, M.; Reeve, B.; Abdi, R.; et al. Shattering Barriers toward Clinically Meaningful MSC Therapies. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba6884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, L.; Wang, T.B.; Wang, X.; Pu, Z. Advancing Diabetes Treatment: The Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Islet Transplantation. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1389134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, A.; Pawlick, R.; Pepper, A.R.; Bruni, A.; Adesida, A.; Senior, P.A.; Korbutt, G.S.; Shapiro, A.M.J. Improved Islet Recovery and Efficacy through Co-Culture and Co-Transplantation of Islets with Human Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, N.; Buhler, L.; Egger, B.; Gonelle-Gispert, C. Multipotent Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Interact and Support Islet of Langerhans Viability and Function. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 822191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawal, S.; Williams, S.J.; Ramachandran, K.; Stehno-Bittel, L. Integration of Mesenchymal Stem Cells into Islet Cell Spheroids Improves Long-Term Viability, but Not Islet Function. Islets 2017, 9, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari, E.; Meier, R.P.H.; Mahou, R.; Seebach, J.D.; Wandrey, C.; Gerber-Lemaire, S.; Buhler, L.H.; Gonelle-Gispert, C. Multipotent Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Enhance Insulin Secretion from Human Islets via N-Cadherin Interaction and Prolong Function of Transplanted Encapsulated Islets in Mice. Stem Cell Res Ther 2017, 8, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, B.M.; Bouças, A.P.; Oliveira, F.D.S.D.; Reis, K.P.; Ziegelmann, P.; Bauer, A.C.; Crispim, D. Effect of Co-Culture of Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells with Pancreatic Islets on Viability and Function Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Islets 2017, 9, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannasi, C.; Niada, S.; Della Morte, E.; Casati, S.; Orioli, M.; Gualerzi, A.; Brini, A.T. Towards Secretome Standardization: Identifying Key Ingredients of MSC-Derived Therapeutic Cocktail. Stem Cells International 2021, 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liang, B.; Xu, J. Unveiling Heterogeneity in MSCs: Exploring Marker-Based Strategies for Defining MSC Subpopulations. J Transl Med 2024, 22, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouaib, B.; Haack-Sørensen, M.; Chaubron, F.; Cuisinier, F.; Collart-Dutilleul, P.-Y. Towards the Standardization of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome-Derived Product Manufacturing for Tissue Regeneration. IJMS 2023, 24, 12594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Mack, R.; Breslin, P.; Zhang, J. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Aging in Hematopoietic Stem Cells and Their Niches. J Hematol Oncol 2020, 13, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preda, M.B.; Neculachi, C.A.; Fenyo, I.M.; Vacaru, A.-M.; Publik, M.A.; Simionescu, M.; Burlacu, A. Short Lifespan of Syngeneic Transplanted MSC Is a Consequence of in Vivo Apoptosis and Immune Cell Recruitment in Mice. Cell Death Dis 2021, 12, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zeng, F.; He, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, D. Alteration of the Immune Status of Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells Stimulated by TLR1/2 Agonist, Pam3Csk. Molecular Medicine Reports 2016, 14, 2206–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Click-ITTM Plus TUNEL Assay Kit for In Situ Apoptosis Detection Available Online:. Available online: Https://Assets.Fishersci.Com/TFS-Assets/BID/Manuals/MAN0010877_Click_iT_Plus_TUNEL_Assay_UG.Pdf (accessed on day month year).

- Deskins, D.L.; Bastakoty, D.; Saraswati, S.; Shinar, A.; Holt, G.E.; Young, P.P. Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: Identifying Assays to Predict Potency for Therapeutic Selection. Stem Cells Translational Medicine 2013, 2, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Liu, N.; Bao, C.; Yang, D.; Ma, G.; Yi, W.; Xiao, G.; Cao, H. Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Fibrotic Diseases—the Two Sides of the Same Coin. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2023, 44, 268–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshmi, B.; Cheshomi, H. Salivary Exosomes: Properties, Medical Applications, and Isolation Methods. Mol Biol Rep 2020, 47, 6295–6307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Hefley, B.; Escandon, P.; Nicholas, S.E.; Karamichos, D. Salivary Exosomes in Health and Disease: Future Prospects in the Eye. IJMS 2023, 24, 6363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reseco, L.; Molina-Crespo, A.; Atienza, M.; Gonzalez, E.; Falcon-Perez, J.M.; Cantero, J.L. Characterization of Extracellular Vesicles from Human Saliva: Effects of Age and Isolation Techniques. Cells 2024, 13, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, S.J.; Larsen, M.; DeVine, T. Extracellular Matrix and Growth Factors in Salivary Gland Development. In Frontiers of Oral Biology; Tucker, A.S., Miletich, I., Eds.; S. Karger AG, 2010; Vol. 14, pp. 48–77 ISBN 978-3-8055-9406-6.

- Pellegrini, M.; Pulicari, F.; Zampetti, P.; Scribante, A.; Spadari, F. Current Salivary Glands Biopsy Techniques: A Comprehensive Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaferia, G.R.; Jimenez-Caliani, A.J.; Ranjitkar, P.; Yang, W.; Hardiman, G.; Rhodes, C.J.; Crisa, L.; Cirulli, V. Β1 Integrin Is a Crucial Regulator of Pancreatic β-Cell Expansion. Development 2013, 140, 3360–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. Targeting Ceramides and Adiponectin Receptors in the Islet of Langerhans for Treating Diabetes. Molecules 2022, 27, 6117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilani, A.; Stoll, L.; Homan, E.A.; Lo, J.C. Adipose Signals Regulating Distal Organ Health and Disease. Diabetes 2024, 73, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, G.A.; Moore, M.J.; El-Nakeep, S. Physiology, Von Willebrand Factor. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Valdivia, A.; Avalos, A.M.; Leyton, L. Thy-1 (CD90)-Regulated Cell Adhesion and Migration of Mesenchymal Cells: Insights into Adhesomes, Mechanical Forces, and Signaling Pathways. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1221306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Mitsuhashi, N.; Klein, A.; Barsky, L.W.; Weinberg, K.; Barr, M.L.; Demetriou, A.; Wu, G.D. The Role of the Hyaluronan Receptor CD44 in Mesenchymal Stem Cell Migration in the Extracellular Matrix. Stem Cells 2006, 24, 928–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alborzian Deh Sheikh, A.; Akatsu, C.; Abdu-Allah, H.H.M.; Suganuma, Y.; Imamura, A.; Ando, H.; Takematsu, H.; Ishida, H.; Tsubata, T. The Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase SHP-1 (PTPN6) but Not CD45 (PTPRC) Is Essential for the Ligand-Mediated Regulation of CD22 in BCR-Ligated B Cells. The Journal of Immunology 2021, 206, 2544–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sionov, R.V.; Ahdut-HaCohen, R. A Supportive Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cells on Insulin-Producing Langerhans Islets with a Specific Emphasis on The Secretome. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Signaling pathway | Dominant role of mMSCs (Importance) |

Dominant role of mSGCs (Importance) |

Dominant interaction of mMSCs (Communication. Prob.) |

Dominant interaction of mSGCs (Communication. Prob.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COLLAGEN | Mediator (100%) | Influencer (30%) | mMSC+Exo_Pan (3.25) | - |

| FN1 | Sender (90%) | Influencer (30%) | mMSC+Exo_Pan (1.5) | - |

| ICAM | Influencer (100%) | Receiver (90%) | mMSC+Exo_Pan (3) | mSGC+Exo_Pan (2.5) |

| JAM | Influencer (80%) | Receiver (70%) | mMSC+Exo_Pan (0.5) | - |

| Laminin | Influencer (70%) | Influencer (40%) | mMSC+islets (3) | - |

| MIF | Influencer (50%) | Mediator (80%) | mMSC+Exo_Pan (0.52) | mSGC+islets (0.54) |

| PECAM1 | Sender (80%) | Receiver (90%) | mMSC+Exo_Pan (0.46) | mSGC+islets (0.52) |

| THY1 | Mediator (90%) | Influencer (70%) | mMSC+islets (0.55) | mSGC+islets (0.6) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).