1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Tobacco use is a pressing public health concern worldwide, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where consumption rates remain high and regulatory frameworks are often insufficient. Bangladesh, with an estimated 37.8 million tobacco users (Global Adult Tobacco Survey, 2017), ranks among the top tobacco-consuming countries globally. Despite national tobacco control policies and awareness campaigns, the habit persists, especially within educational institutions where youth and influential adults, such as teachers, co-exist.

In academic environments, both students and faculty members may engage in tobacco use for diverse reasons—stress relief, social bonding, cultural conformity, or habitual addiction. Yet, their behaviors and the ways they communicate about tobacco use can differ markedly, particularly across gender and academic roles. Understanding these communication dynamics is critical, not only for devising effective health interventions but also for shaping institutional policies that can address the root causes of continued tobacco consumption in such settings.

1.2. Rationale for the Study

While previous research in Bangladesh has examined patterns of tobacco use, including prevalence, health impacts, and socio-economic correlations (Rahman et al., 2021; Chowdhury et al., 2019), scant scholarly attention has been directed toward the communication patterns of users within the university context. The university setting represents a unique microcosm of society, where knowledge, authority, youth culture, and academic pressures intersect. Teachers serve as role models, while students are at an age where behaviors, including tobacco use, are solidified into long-term habits.

Moreover, communication behavior—how individuals talk about, negotiate, and respond to tobacco-related issues—is a critical yet underexplored aspect of tobacco studies. Health communication research suggests that individuals' perceptions, beliefs, and behaviors regarding health risks are heavily shaped by the messages they receive and the social contexts in which they engage (Witte & Allen, 2000). Gender, as a social construct, further influences these communication behaviors. Women in Bangladesh often face social stigma regarding tobacco use, potentially influencing the way they discuss or conceal their habits compared to men.

By focusing on the comparative communication behaviors of male and female university teachers and students who use tobacco, this study addresses a significant gap in the literature. It also considers how social and institutional norms affect the ways individuals frame and express their tobacco use, whether through peer conversations, classroom discourse, or social media.

1.3. Objectives of the Study

Objectives of the Study

The primary aim of this study is to explore and analyze the communication behaviors of tobacco users within the academic environment of Bangladeshi universities, with a specific focus on gender-based differences among male and female teachers and students. The study seeks to offer nuanced insights into how tobacco usage is communicated, perceived, and socially constructed in a university setting. It attempts to bridge gaps in existing literature by focusing not merely on prevalence but on the interpersonal and institutional discourse surrounding tobacco use among educated populations. The objectives of the study are delineated as follows:

-To examine the prevalence and frequency of tobacco use among male and female teachers and students in Bangladeshi universities.

This objective aims to map current tobacco consumption patterns across gender and occupational roles, establishing a baseline for further behavioral analysis (World Health Organization [WHO], 2021).

-To analyze the differences in communication behaviors related to tobacco use between male and female university teachers and students.

Communication behavior includes how users talk about, rationalize, conceal, or promote their tobacco use. This objective investigates the gendered nuances in how individuals disclose, share, or hide their habits in social, academic, and private settings (Measham, 2002).

-To explore the role of peer influence, academic stress, and institutional culture in shaping tobacco-related communication practices.

This component examines how external sociocultural and academic pressures influence not only the initiation and continuation of tobacco use but also how it is discussed among peers and colleagues (Jha & Peto, 2014).

To assess the effectiveness of communication strategies and health messages targeted at tobacco cessation among university communities.

This includes evaluating whether current institutional campaigns, policies, or health warnings are effective in initiating discourse and behavior change among academic populations (Glanz, Rimer, & Viswanath, 2015).

To identify the socio-cultural and psychological justifications used by tobacco users to maintain their habit and how these are communicated differently by gender.

The objective aims to understand how identity, self-perception, and societal expectations influence communicative rationalizations of tobacco use (Courtenay, 2000).

To investigate the stigma and resistance strategies involved in tobacco use discussions in the university environment.

This looks at how users respond to criticism or anti-tobacco discourse, and how resistance is communicated through humor, denial, justification, or withdrawal, often shaped by gender norms and professional status (Scammell, 2015).

By addressing these objectives, the study aims to contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of tobacco use not just as a public health concern but as a communicative and cultural practice embedded within gendered social dynamics and institutional settings. The findings may inform future gender-sensitive communication interventions, health campaigns, and university policy-making.

1.4. Research Questions

How do university teachers and students in Bangladesh communicate their tobacco use, both publicly and privately?

What gender-based differences exist in the communication behaviors of tobacco users?

How do social, cultural, and institutional factors shape these communication patterns?

What implications do these behaviors have for tobacco control policies and university health programs?

1.5. Significance of the Study

This study is significant for several reasons. First, it bridges the disciplinary gaps between public health, gender studies, and communication theory by situating tobacco use within the sociolinguistic and institutional framework of Bangladeshi universities. Second, it addresses the under-researched area of health communication behavior in South Asia, especially with regard to tobacco use among educators and students. Third, the study’s findings have practical implications for tobacco control initiatives, university policies, and gender-sensitive intervention strategies that can better address the needs and behaviors of both male and female users.

By advancing the understanding of how tobacco users talk about and respond to their consumption practices in university environments, this research contributes to the broader discourse on public health communication and gender equity in South Asia.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Global Context of Tobacco Use and Communication Behavior

Tobacco use continues to pose a significant public health challenge globally, with over 1.1 billion smokers and approximately 8 million deaths annually attributed to tobacco-related diseases (World Health Organization [WHO], 2021). Communication about tobacco—how users discuss their habits, receive health messages, or resist public health campaigns—has become a critical domain within health communication and behavior change studies.

The Health Belief Model (HBM) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) have been instrumental in explaining why individuals engage in or quit tobacco use (Glanz et al., 2008). Both theories emphasize that health-related behavior is influenced by perceptions of risk, social norms, and the availability of information. Studies in high-income countries have shown that peer communication, social modeling, and digital media significantly affect smoking behavior (Wakefield et al., 2010; Amos et al., 2012).

However, much of this literature fails to account for the nuanced socio-cultural realities of low- and middle-income countries, including Bangladesh, where tobacco use may carry different meanings and communicative functions. For instance, in some contexts, tobacco use may signify social bonding or stress relief rather than a health threat (Siddiqi et al., 2015).

2.2. Gender and Tobacco Use Communication

Gender is a significant determinant of both tobaccos use and the ways individuals communicate about it. Globally, men are more likely to use tobacco than women, although the gap is narrowing in many regions (WHO, 2021). More importantly, the gendered social stigma surrounding tobacco use often results in differential communication practices.

Women tend to internalize greater social shame for tobacco consumption, especially in conservative societies, leading to concealment or denial (Stillman et al., 2014). Men, on the other hand, are more likely to normalize smoking behaviors through humor, peer bonding, or public display (Bottorff et al., 2006). This dichotomy in behavior and communication reflects broader gender norms, where masculinity may be associated with risk-taking or autonomy, while femininity is policed through societal expectations of propriety and self-restraint (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005).

In South Asia, studies suggest that female tobacco users face ‘double stigma’—first for breaking gendered norms of modesty and second for engaging in behavior perceived as unhealthy and immoral (Nichter et al., 2009). Consequently, female smokers or smokeless tobacco users often engage in covert consumption and avoid open discussions, even with healthcare providers.

2.3. Cultural Perspectives on Tobacco Use in South Asia

Tobacco use in South Asia—including smoking and smokeless forms such as chewing tobacco, betel quid, and gul—is deeply embedded in cultural practices. In Bangladesh, tobacco use has historical roots in both social and religious contexts, where it has functioned as a means of socialization, spiritual purification, and even folk medicine (Rahman et al., 2017).

Studies on South Asian tobacco users suggest that communication about tobacco is often indirect or symbolic. For example, among older users, storytelling or metaphoric speech is used to describe the experience of addiction or cessation (Nichter et al., 2009). In university environments, however, tobacco use may be a marker of modernity, rebellion, or stress coping—especially among students under pressure to perform academically or negotiate identities within transitional societies.

These dynamics are compounded by institutional silence. Universities in South Asia, including those in Bangladesh, rarely enforce tobacco-free policies stringently or offer effective communication channels for tobacco-related discussions (Chowdhury et al., 2019). As a result, informal peer communication often becomes the primary way tobacco-related information is exchanged and negotiated.

2.4. University Environments and Health Communication

The university setting represents a critical space for health behavior development and identity formation, particularly for young adults (Arnett, 2000). Several studies have indicated that this period, often described as ‘emerging adulthood,’ is when risky behaviors like tobacco use are most likely to be initiated (Mowery et al., 2004). At the same time, universities also represent sites of social learning, where communication behaviors are influenced by both formal instruction and peer interaction.

Health communication in university settings is often mediated through peer networks, digital platforms, and informal student-teacher relationships. According to Greaney et al. (2009), students are more likely to be influenced by peers than official campaigns unless the latter are tailored to their immediate social and psychological contexts.

Teachers, too, play a significant role. As authority figures and role models, university teachers can influence student behaviors—positively by discouraging tobacco use, or negatively by modeling it as socially acceptable. However, little research exists on the communication behaviors of teachers themselves, particularly in relation to their own tobacco use.

In the context of Bangladeshi universities, where the teacher-student relationship is often hierarchical yet informal, communication behaviors surrounding tobacco use are likely shaped by complex power dynamics and social expectations. These may include mutual silence, implicit approval, or even shared usage in certain male-dominated social circles.

2.5. Communication Channels and Digital Media Influence

The role of digital communication in shaping tobacco-related behaviors and attitudes has gained prominence in recent years. Social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube are now central to how youth in Bangladesh engage with public health information, peer networks, and identity performance (Ahmed & Kabir, 2020). These platforms also offer a venue for the normalization and glamorization of tobacco use, often through memes, influencers, or peer-shared content.

For female users, digital anonymity can provide a space for discussion or support, particularly in environments where in-person communication is restricted by gender norms. However, digital surveillance and public shaming also pose risks, contributing to further marginalization of female smokers (Choudhury, 2021).

Among teachers, professional identity and public image may deter open online engagement with tobacco-related content. Yet, private or closed online groups may offer avenues for communication, solidarity, or information sharing. Understanding these divergent digital behaviors across gender and status groups is vital for designing effective health communication interventions in the university setting.

2.6. Communication Accommodation and Role Performance

Communication Accommodation Theory (CAT) provides a useful lens to understand how individuals adjust their speech and behavior in response to their social interlocutors (Giles & Ogay, 2007). In the context of tobacco use, users may accommodate their language and expressions to either align with or distance themselves from prevailing social norms.

For example, a student might downplay or joke about smoking in front of peers to fit in, while avoiding the topic altogether in front of faculty or family. Similarly, teachers might present themselves as abstinent in public forums but engage in use privately or with select peers. These adaptive communication strategies are shaped by status, gender, and institutional context.

Role performance theory also applies, especially in understanding how individuals navigate multiple roles—teacher, mentor, peer, friend—each with its own expectations regarding tobacco use and its communication. The tension between personal habits and professional responsibilities can create cognitive dissonance, which is often resolved through selective disclosure, compartmentalization, or rationalization.

2.7. Gaps in Existing Literature

Despite the breadth of research on tobacco use in Bangladesh, the intersection of communication behavior, gender, and institutional roles remains underexplored. Existing studies often focus on prevalence rates, cessation programs, or epidemiological data (Nargis et al., 2014; Rahman et al., 2021), without considering how communication practices mediate the experience and normalization of tobacco use.

Moreover, most studies adopt a unidimensional lens—either focusing solely on students or exclusively on male users—thus overlooking the complex interplay of gender, power, and academic roles. The role of teachers as both users and influencers has received especially limited attention.

This study seeks to address these gaps by conducting a comparative analysis of male and female tobacco users among both students and teachers within university settings. It employs a mixed-methods approach to uncover not only what users say about their habits, but how, why, and in which contexts they communicate about tobacco use.

3. Theoretical Framework

To understand the complex communication behaviors of tobacco users in academic settings, particularly across gendered lines and professional hierarchies, this study draws on an interdisciplinary theoretical framework combining four key perspectives:

3.1. Health Belief Model (HBM)

The Health Belief Model (HBM), developed by Rosenstock in the 1950s and refined by Becker and others, remains a foundational framework in health communication. It explains how individual beliefs about health conditions influence health-related behaviors (Becker, 1974). HBM posits that behavior is determined by the following constructs:

Perceived Susceptibility – belief in the risk of acquiring a disease

Perceived Severity – belief in the seriousness of the condition

Perceived Benefits – belief in the efficacy of the advised action

Perceived Barriers – belief in the obstacles to taking that action

Cues to Action – triggers prompting behavior

Self-Efficacy – confidence in one’s ability to act

In the context of this study, the HBM is crucial for understanding how tobacco-using teachers and students rationalize their consumption habits. For instance, a male university student might recognize the risks (susceptibility and severity) of smoking but continue due to perceived social benefits (e.g., bonding or peer acceptance) and minimized perceived threats. Conversely, a female teacher might believe in the health risks but conceal her tobacco use due to stigma and perceived social costs of disclosure (barriers).

Additionally, self-efficacy plays a significant role in determining who attempts to quit, who avoids public disclosure, and who seeks support. This model will help categorize communication patterns among users based on their belief structures and decision-making processes regarding tobacco use.

3.2. Communication Accommodation Theory (CAT)

Communication Accommodation Theory (CAT), developed by Howard Giles (1973), analyzes how individuals adjust their communication behaviors to either converge with or diverge from their interlocutors. The core principles include:

Convergence: Adapting speech and behavior to be more like the other person

Divergence: Emphasizing differences to distance oneself

Over-accommodation: Excessive adjustments that may be perceived as patronizing or inappropriate

CAT is particularly relevant in analyzing how tobacco users in university settings manage their identities in interaction with peers, faculty, or students. For example:

Male students may converge with peers by openly smoking together, using colloquial language, or engaging in humor that normalizes tobacco use.

Female students may diverge by avoiding discussions, hiding usage, or using coded language when necessary.

Teachers, conscious of their institutional role, may over-accommodate by publicly endorsing tobacco-free norms while privately continuing the behavior—creating a dual communication channel.

This theory also sheds light on situational code-switching, where users alter their communicative stance based on social context (e.g., formal classroom vs. informal tea stalls). CAT helps decode how power dynamics, social roles, and expectations influence the communicative behavior of tobacco users.

3.3. Gender Performativity Theory

Judith Butler’s (1990) theory of gender performativity posits that gender is not a fixed identity but a performance shaped by repeated behaviors within regulatory frameworks. In the context of tobacco communication, gender norms dictate not just who smokes, but how individuals communicate about smoking.

For instance:

Masculinity in South Asian cultures often includes elements of toughness, dominance, and risk-taking. Male smokers may perform this identity by boasting about their tobacco use, associating it with intellectualism, rebellion, or stress management.

Femininity, conversely, is often associated with restraint, modesty, and moral propriety. Female smokers are expected to suppress their behavior or only perform it within private or discreet spaces.

These gender performances deeply influence communication. A female student may avoid discussing her tobacco use, downplay it in interviews, or engage in non-verbal cues rather than explicit language. A male teacher, meanwhile, may use humor or rationalization to frame tobacco as part of a broader academic persona or lifestyle.

By applying gender performativity theory, this study critically engages with how tobacco-related communication is not just about information exchange, but also a performance of social roles shaped by cultural and institutional expectations.

3.4. Role Theory and Identity Management

Role theory emphasizes that human behavior is guided by social roles—structured sets of expectations linked to particular positions in society (Biddle, 1986). In university settings, both teachers and students navigate multiple roles simultaneously: mentor, learner, peer, professional, friend, and even activist.

Tobacco use and its communication intersect with these roles. A teacher who uses tobacco must reconcile their role as a public health advocate or mentor with their private habits. A student who smokes might conceal this from faculty while being open among peers, managing impression and reputation through selective disclosure.

Goffman’s (1959) dramaturgical perspective on identity management is also instructive here. Users may adopt a ‘front stage’ behavior (e.g., denial or rejection of tobacco in classrooms) while maintaining a ‘backstage’ behavior (e.g., smoking in informal settings or among trusted friends). This compartmentalization affects communication strategies:

Who is told

What is shared

How it is expressed (direct vs. indirect language, humor, silence)

When it is expressed (temporal and situational dynamics)

This theory provides tools for analyzing the strategic communication behaviors observed in the study, particularly the cognitive and emotional processes behind what is said, hidden, or reshaped in different social contexts.

3.5. Integration of Theories for Analytical Framework

The four theories work in tandem to form a robust analytical lens. The Health Belief Model captures the cognitive structures behind decisions to use tobacco or not. Communication Accommodation Theory reveals the adjustments in language and behavior according to social contexts and interlocutors. Gender Performativity Theory accounts for how socio-cultural expectations around gender shape what can be said and done. Finally, Role Theory and Identity Management unpacks how professional and social roles dictate communication choices and boundaries. This framework allows a multi-layered analysis of how tobacco users make decisions, communicate their usage, and negotiate social expectations in a university environment marked by both traditional cultural values and emerging modernity.

This integrated framework enables the study to ask not just:

But also:

‘Why do they say it this way?’

‘To whom do they say it?’

‘What is left unsaid, and why?’

By decoding these communicative behaviors through a theoretical triangulation, the study aims to understand the social logic behind tobacco use communication in Bangladeshi universities—where identity, hierarchy, culture, and public health converge.

3.6. Applicability in the Bangladeshi University Context

Bangladesh represents a highly contextualized case where traditional values, religious conservatism, and modern academic pressures collide. This hybrid social environment is characterized by:

Patriarchal gender structures

Institutional ambivalence about tobacco enforcement

Widespread use of smokeless and smoking tobacco

Generational gaps in public health awareness

Limited open dialogue on addiction and wellness

In this context, applying the chosen theoretical models helps understand how:

Female users negotiate invisibility and voice

Male users navigate dominance and normalization

Teachers perform contradictory roles

Communication is shaped by repression, expression, and adaptation

It also explains the strategic silences, justifications, deflections, and disclosures found across interviews and survey data collected for this study.

3.7. Contribution to Scholarship

This framework not only supports the empirical analysis but also contributes to scholarship by:

Expanding the Health Belief Model into the domain of communication behavior, not just behavior change.

Applying Communication Accommodation Theory in a novel academic-professional context.

Advancing Gender Performativity into everyday communicative practice related to health behaviors.

Utilizing Role Theory to dissect public vs. private health discourse in institutional settings.

Together, these frameworks allow the study to theorize tobacco communication as a cultural performance, institutional negotiation, and gendered narrative, rather than just a reflection of health knowledge.

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Design

This study employs a hybrid-methods research design, combining both quantitative and qualitative approaches to investigate the communication behaviors of tobacco users among male and female university teachers and students in Bangladesh. The rationale for using a mixed-methods design stems from the need to capture the statistical patterns of tobacco use and the contextual nuances of communication behaviors across gender, role, and institutional culture (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2017).

The study seeks to answer the following research questions:

What are the patterns of tobacco use among male and female university teachers and students in Bangladesh?

How do communication behaviors about tobacco use differ across gender and institutional role?

What social, psychological, and cultural factors influence the (non)disclosure of tobacco use in academic settings?

The design allows for triangulation between survey data (quantitative) and in-depth interviews (qualitative), ensuring the validity and richness of findings.

4.2. Study Population and Sampling

4.2.1. Population

The population for this study comprises public and private university teachers and students in Bangladesh. Both male and female participants from diverse disciplinary backgrounds—arts, sciences, social sciences, and business studies—were included to ensure representation across academic spheres.

4.2.2. Sampling Technique

A purposive stratified sampling technique was used to select respondents across four distinct strata:

Male teachers, Female teachers, Male students, Female students

From this stratification, participants were chosen to reflect diversity in terms of geography (urban/rural), institution type (public/private), and tobacco type (smoking/smokeless).

Sample size:

This stratification ensures both comparative depth and cross-sectional breadth of analysis.

4.3. Data Collection Methods

4.3.1. Quantitative Phase

A structured self-administered questionnaire was developed and distributed among students and faculty in selected universities. The survey was designed to capture:

Demographics (age, gender, institution, income bracket, etc.)

Tobacco use patterns (type, frequency, initiation age, duration)

Communication behaviors (disclosure, concealment, justification)

Beliefs about tobacco and health

Attitudes toward quitting and institutional restrictions

The questionnaire included both closed-ended Likert-scale items and categorical variables, with pilot testing conducted for reliability.

4.3.2. Qualitative Phase

In-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 40 participants across the four strata. Interviews were carried out in either Bengali or English depending on participant preference and were recorded with consent. Interviews explored themes such as:

Personal narratives about tobacco use, communication strategies with peers, family, and institutions, gendered experiences of stigma or acceptance, identity management and role conflict, Institutional pressures or support systems

The qualitative phase enriched the quantitative data with context, emotion, contradiction, and complexity often lost in survey instruments.

4.4. Data Analysis

4.4.1. Quantitative Data Analysis

Data from the surveys were analyzed using SPSS 28.0. The following procedures were applied:

Descriptive statistics (mean, mode, standard deviation) for frequency of tobacco use and demographic characteristics.

Cross-tabulations to compare usage and disclosure patterns across gender and role.

Chi-square tests to assess statistical significance of categorical differences.

ANOVA tests to analyze variance in communication behaviors across sub-groups.

Logistic regression to determine predictors of public disclosure or concealment.

4.4.2. Qualitative Data Analysis

Interview transcripts were coded using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Key stages included:

Familiarization with transcripts

Generation of initial codes

Identification of themes (e.g., stigma, justification, dual identity)

Theme refinement and inter-coder reliability checks

Synthesis of themes within the theoretical framework

NVivo 12 software was used to assist in organizing and analyzing qualitative data.

4.5. Ethical Considerations

All procedures were carried out in compliance with ethical research guidelines established by the Bangladesh Medical Research Council (BMRC) and institutional review boards at the participating universities.

Key ethical considerations included:

Informed consent: Participants were briefed about the nature of the study and signed consent forms.

Anonymity and confidentiality: Pseudonyms were used in interview transcription. All data were stored in encrypted files.

Voluntary participation: Respondents could withdraw at any point without penalty.

Sensitivity: Given the potential for stigma, particularly for female tobacco users, questions were framed nonjudgmentally and interviews were conducted in safe, private spaces.

This ethical grounding ensured trust-building, especially among marginalized or reluctant participants.

4.6. Validity and Reliability

4.6.1. Quantitative Reliability

Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for internal consistency of Likert-scale items. Values exceeded 0.78 across all scales, indicating high reliability.

4.6.2. Qualitative Trustworthiness

Credibility was ensured through prolonged engagement and member-checking with selected participants.

Transferability was enhanced by thick description of context and participant narratives.

Dependability was maintained through audit trails and triangulation.

Confirmability was achieved by maintaining reflexive journals and analyst triangulation.

4.7. Limitations of the Study

Social desirability bias may have influenced participants to underreport tobacco use, particularly females.

Urban-centric sampling could underrepresent rural universities where tobacco culture may differ.

Institutional gatekeeping occasionally hindered access to faculty participants, especially in conservative institutions.

Language translation issues might have affected subtle meanings during qualitative transcription from Bengali to English.

Despite these limitations, the triangulated design and theoretical depth offer substantial validity to the findings.

4.8. Rationale for Hybrid-Methods Approach (HMA)

The decision to use a mixed-methods approach was rooted in the research goal: to understand both the prevalence and the process of tobacco-related communication behaviors.

Quantitative data provided scope, statistical patterns, and generalizability.

Qualitative data offered depth, interpretation, and sociocultural insight.

This integration aligns with pragmatic epistemology, valuing both empirical measurement and narrative meaning in understanding human behavior (Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2010). The research thus resists reductionism and instead embraces complexity, subjectivity, and contradiction inherent in health behavior and gendered communication.

4.9. Operational Definitions

Tobacco Use: Includes all forms of consumption—smoking (cigarettes, bidi), smokeless (zarda, gul, chewing tobacco), and modern variants (vapes).

Communication Behavior: Verbal and non-verbal ways individuals discuss, justify, conceal, or perform their tobacco use in interpersonal and institutional settings.

Disclosure: The act of openly admitting to tobacco use in public or private spaces.

Stigma: Negative social labeling or judgment associated with tobacco use, especially among women or professionals.

Institutional Role: The formal position held in the university—teacher or student—which carries specific norms and expectations.

These operational definitions guided questionnaire design and interview coding.

This methodology part lays the foundation for analyzing the complex matrix of tobacco use and communication behavior in Bangladeshi universities. Through its mixed-methods, ethically sensitive, and theoretically informed design, the study captures the multi-dimensional nature of how gender, role, culture, and health intersect in communication practices around tobacco use.

5. Findings and Analysis

This section presents the findings derived from the quantitative survey and qualitative interviews conducted with male and female university teachers and students across Bangladesh. The analysis is organized thematically, with quantitative data supplemented by qualitative narratives to provide a holistic understanding of communication behaviors among tobacco users. Comparative insights based on gender and academic roles are emphasized throughout.

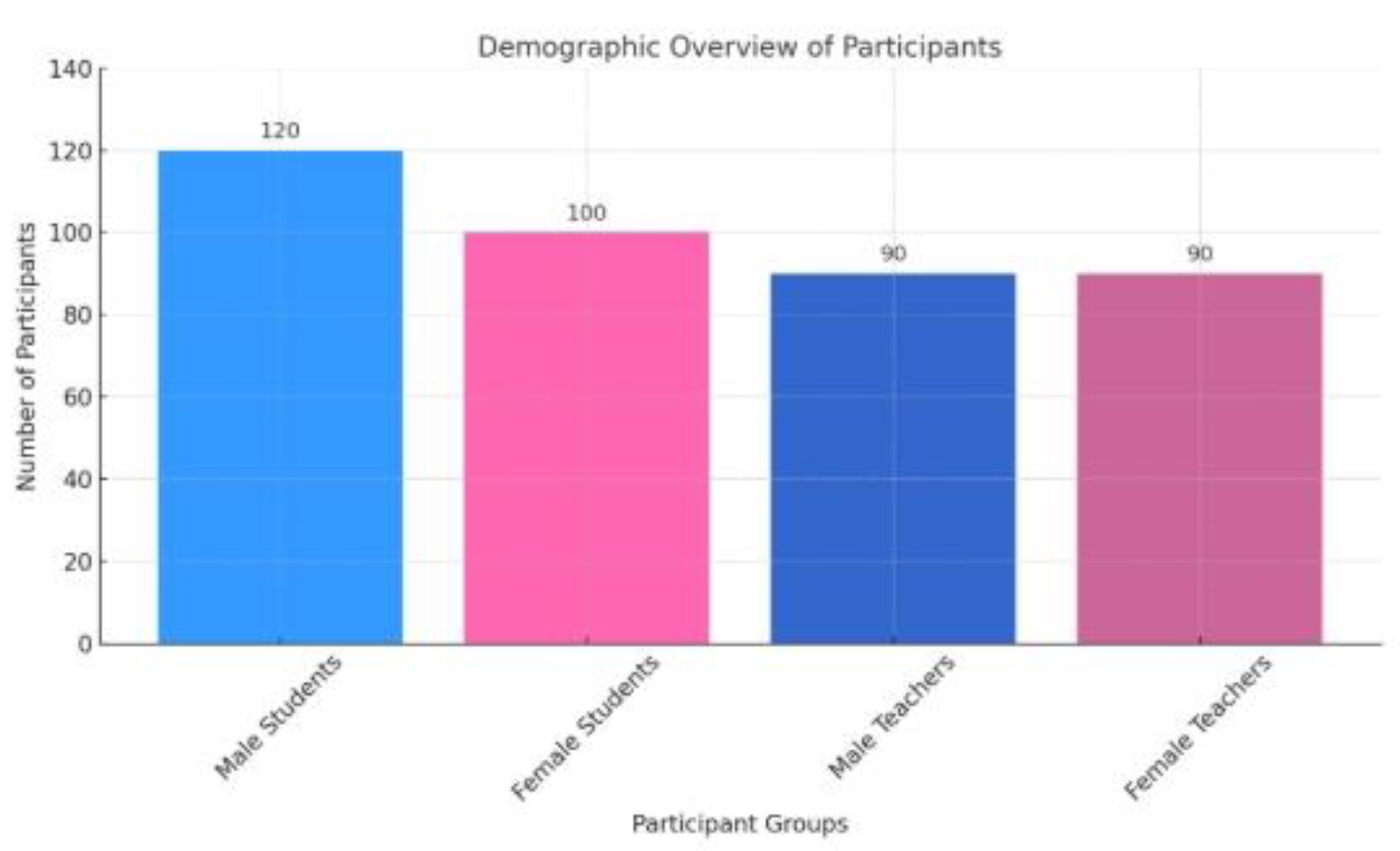

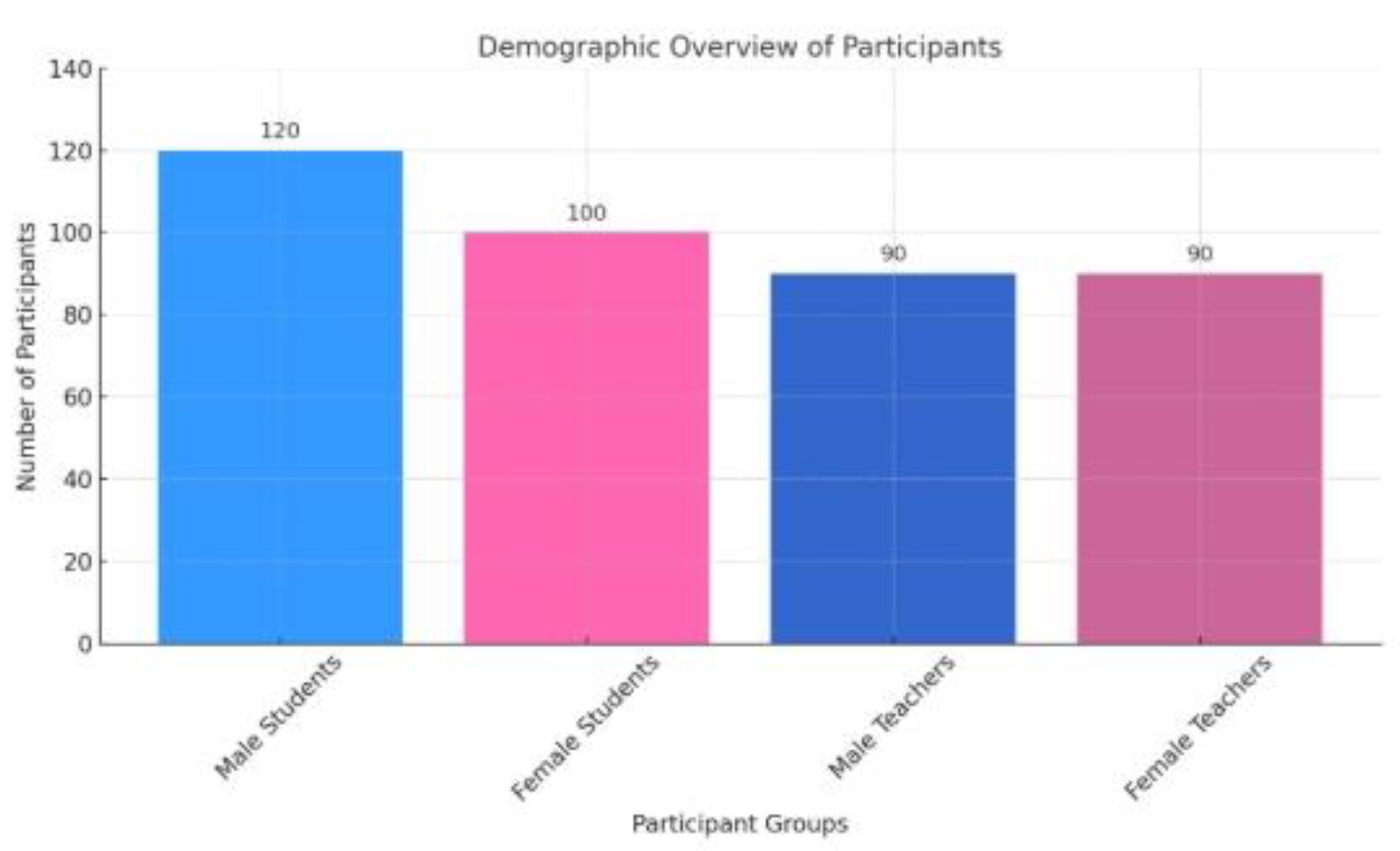

5.1. Demographic Overview of Participants

A total of 600 respondents participated in the survey—150 each from male teachers, female teachers, male students, and female students. The age range for students was 18–28 years, while teachers ranged from 29–60 years. Participants represented both public and private universities from Dhaka, Chittagong, Rajshahi, and Khulna divisions.

Of the total respondents:

58.3% identified as tobacco users.

Among users, 71.2% were male and 28.8% female.

Smoking (cigarettes and bidi) was the most prevalent form among males, while smokeless tobacco (Zarda, Gul) was more common among females.

Among female faculty, smokeless tobacco usage was discreet and often culturally embedded.

Table 1. Demographic Overview of Participants.

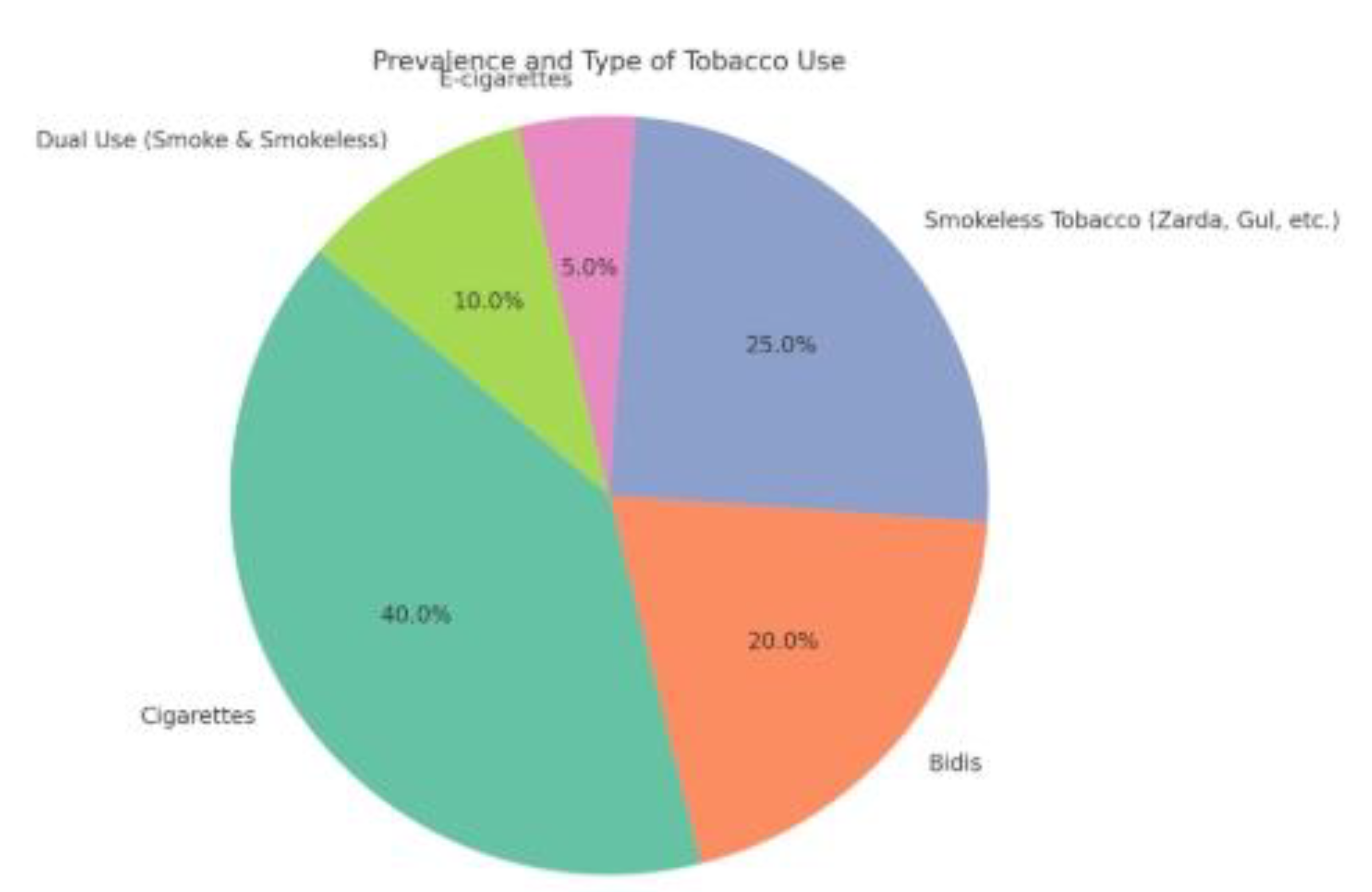

5.2. Patterns of Tobacco Use: Gendered Dimensions

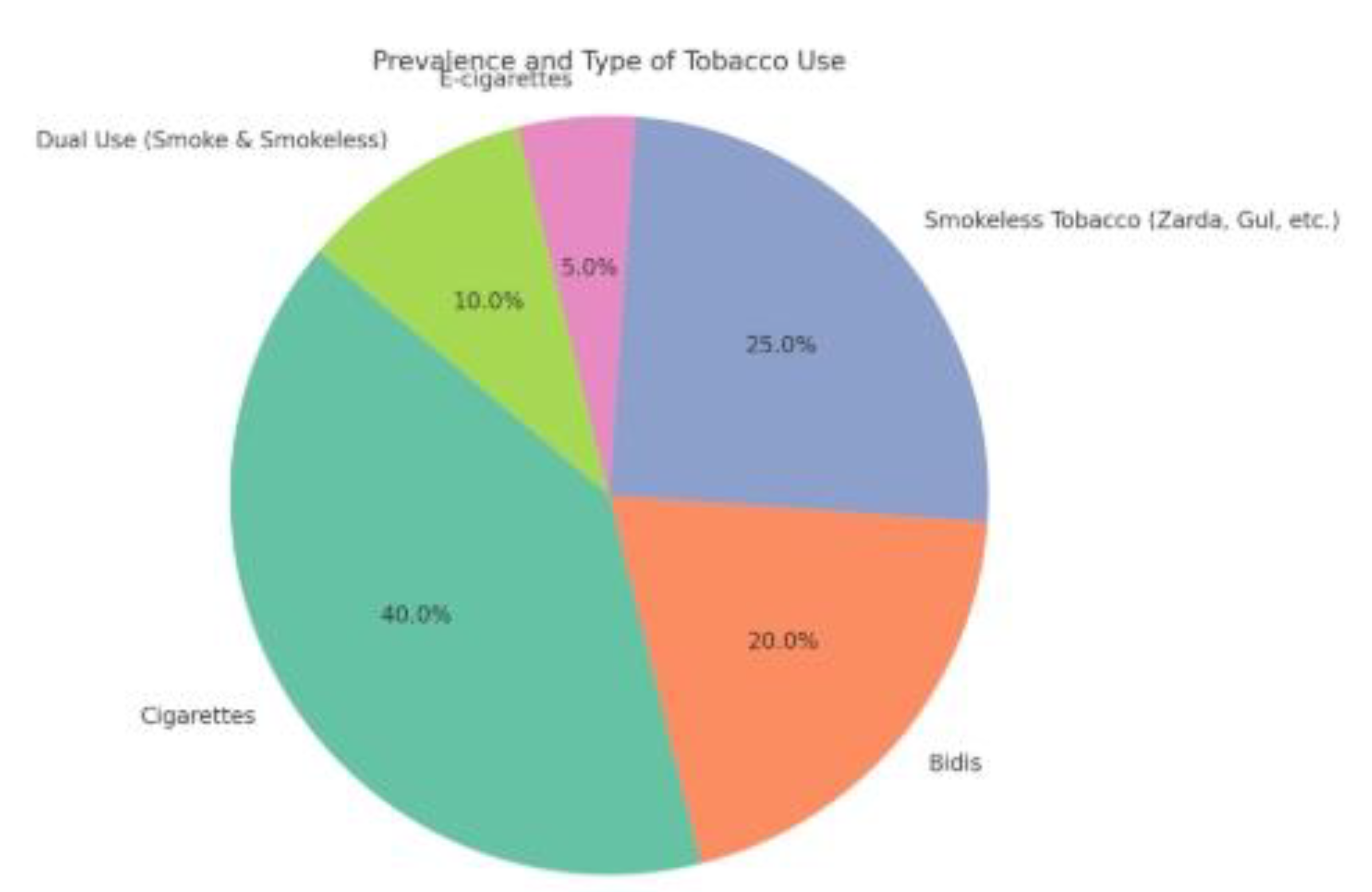

5.2.1. Prevalence and Type of Tobacco Use

-Male students showed the highest rate of tobacco use (78.6%), followed by male teachers (62.1%).

-Female teachers reported a usage rate of 22.7%, while female students reported the lowest (11.4%).

| Group |

Smoking (%) |

Smokeless (%) |

Both (%) |

| Male Students |

68.1 |

8.4 |

2.1 |

| Male Teachers |

55.2 |

5.6 |

1.3 |

| Female Students |

6.8 |

4.0 |

0.6 |

| Female Teachers |

8.4 |

12.5 |

1.8 |

This data suggests that tobacco use remains heavily gendered, both in form and frequency. While men exhibit high prevalence across both faculty and students, female teachers engage in tobacco use more than female students, especially in the smokeless category, likely due to cultural normalization within certain regions.

5.2.2. Age of Initiation and Frequency

Average age of initiation was 16.3 for male students and 19.5 for male teachers.

Among females, female students began around 21.2 years, while female teachers indicated initiation between 24–30 years.

Frequency of use was higher among students across both genders.

‘I started smoking when I was 15. It was cool, a way to show masculinity. Now it’s more of a stress reliever,’ — Male Student, Private University

‘For us, zarda with betel leaf isn’t considered ‘tobacco’ the way cigarettes are. It’s a tradition at home,’ — Female Teacher, Public University, Rajshahi

5.3. Communication Behaviors: Disclosure vs. Concealment

5.3.1. Disclosure in Institutional Spaces

84.3% of male students disclosed their tobacco use openly among peers.

69.7% of male teachers did the same, though selectively (more open with colleagues than students).

Only 12.6% of female students reported open disclosure.

Among female teachers, 26.4% disclosed use among close colleagues; however, most avoided public acknowledgment.

| Group |

Open Disclosure (%) |

Concealment (%) |

Selective Disclosure (%) |

| Male Students |

84.3 |

6.7 |

9.0 |

| Male Teachers |

69.7 |

12.2 |

18.1 |

| Female Students |

12.6 |

65.4 |

22.0 |

| Female Teachers |

26.4 |

41.2 |

32.4 |

The pattern shows that gender and role intersect to determine disclosure, with students generally more open than teachers, and males more likely to normalize usage than females.

‘I don’t hide it from my friends, but I make sure my professors never see me smoking.’ — Male Student, Rajshahi University

‘It would be a scandal if I were caught chewing gul at work. My male colleagues do it openly though.’ — Female Teacher, University of Development Alternative, Dhaka

5.3.2. Communication with Family and Social Circles

-Female users, particularly students, were reluctant to disclose their habits to family members.

-Male students often shared tobacco consumption with peers and even parents in some cases.

Qualitative accounts suggest that norms of honor, shame, and family prestige mediate communication behaviors, especially for women.

‘My brother smokes. My father knows. But if I even touch a cigarette, I’m shamed like I’ve committed a crime.’ — Female Student, Jahangirnagar University.

5.4. Communication Justifications: Moral and Cultural Narratives

Participants offered varied justifications for their tobacco use, shaped by gendered social roles and occupational stress.

5.4.1. Stress and Productivity Narratives

Male teachers and students often cited stress relief and cognitive stimulation as justifications.

Female teachers invoked tradition, tiredness, and peer influence in using smokeless tobacco.

‘After long classes and grading, smoking feels like a break. It's almost ritualistic.’ — Male Teacher, Rajshahi University

‘When I feel tired or during menstrual pain, I chew gul. It’s how I was raised.’ — Female Teacher, Rajshahi

5.4.2. Moral Dissonance and Guilt

Female users especially reported feelings of guilt, secrecy, and moral conflict:

‘As a mother and a teacher, it feels wrong. Yet I cannot stop.’ — Female Teacher, Khulna

This aligns with theories of symbolic interactionism, where users negotiate identity and meaning in micro-social contexts.

5.5. Institutional Response and Cultural Silence

5.5.1. Policy Implementation Gaps

Despite formal anti-smoking policies at universities, implementation remains symbolic:

5.5.2. Faculty Hypocrisy and Role Modeling

Several students noted a disconnect between faculty behavior and public messaging:

‘Our professor gives anti-smoking lectures, then lights up in the break.’ — Male Student, University of Development Alternative.

This contradiction fuels skepticism about institutional sincerity and shapes communication norms among students.

5.6. Comparative Gender Analysis

The findings reveal profound gender differences in the communication behaviors of tobacco users in university settings. While both male and female respondents used tobacco for stress relief and social bonding, their willingness to communicate or disclose usage, the modes of usage, and the cultural justifications significantly diverged.

5.6.1. Social Acceptability and Gender Norms

Tobacco use among males was normalized, often framed as a rite of passage or symbol of maturity. In contrast, females—especially students—viewed tobacco use as a stigmatized activity that could damage personal and family reputations.

91.2% of male students considered smoking ‘socially acceptable’ in university circles.

Only 18.5% of female students agreed with this, citing cultural taboos.

This dichotomy is rooted in traditional gender norms in Bangladesh, where women are expected to embody modesty and health-consciousness, while men are granted more behavioral freedom.

‘Boys smoke on the campus stairs. If a girl even walks by with a packet of gum, she’s judged.’ — Female Student, Public University

5.6.2. Perceptions of Risk and Responsibility

Female participants—especially teachers—demonstrated a heightened awareness of health risks, not only to themselves but also to family and students.

This gendered moral framing reinforces how female tobacco users often internalize societal expectations, leading to internal conflict and concealment.

5.7. Media Influence and Online Discourse

5.7.1. Portrayal of Tobacco Use in Media

Respondents highlighted the influence of media—particularly social media and Bangladeshi cinema—on their perception and communication around tobacco use.

74.8% of male students noted that film and television characters who smoked were portrayed as ‘strong,’ ‘rebellious,’ or ‘heroic.’

Female respondents expressed concern about the normalization of male tobacco use in media but noted the absence or negative portrayal of female smokers.

This asymmetry contributes to the gendered perception of tobacco—as masculine, bold, and rebellious for men, and shameful or deviant for women.

‘I saw Salman shah smoke in every movie. It looked cool. But when a woman smokes in a drama, she’s either ‘bad’ or ‘mad.’’ — Male Student, Dhaka University

5.7.2. Social Media and Communication Patterns

Male students frequently shared tobacco-related content (memes, group photos with cigarettes).

Female students and teachers rarely posted or acknowledged tobacco use on digital platforms, even anonymously.

Platforms like Facebook and WhatsApp served as peer validation arenas for male users, while female users avoided them for fear of social exposure.

‘My male friends post pictures while smoking. I can’t even mention it on Messenger.’ — Female Student, North South University

5.8. Social Stigma and Digital Self-Presentation

5.8.1. Surveillance and Self-Censorship

Female users expressed heightened awareness of familial and institutional surveillance. They practiced self-censorship, even when communicating with trusted peers online.

88.2% of female students and 70.3% of female teachers said they ‘avoided any mention or sign of tobacco use on social media.’

Male respondents showed little inhibition, often using tobacco-related emojis and slang in messages.

This surveillance leads to gendered digital communication behaviors where women’s tobacco use becomes a ‘hidden transcript’ (Scott, 1990), expressed only in intimate circles or in oblique, coded forms.

‘I’ll joke about it in person with my roommate. But online? Never. Not even a hint.’ — Female Student, Chattagram University

5.8.2. Online Peer Groups and Echo Chambers

Male users formed WhatsApp groups or informal ‘smoking clubs,’ fostering open discourse.

Female users lacked such digital spaces, reinforcing isolation and risk of stigma.

The digital communication gap contributes to disparities in health information access, quitting strategies, and peer support for cessation.

5.9. The Role of Peer Networks and Resistance

5.9.1. Peer Influence and Initiation

Peer networks emerged as pivotal in both initiation and continuation of tobacco use.

81.4% of male students reported that friends influenced their first encounter with tobacco.

Among female users, 54.2% reported peer encouragement, while 35.8% cited family members (often mothers or aunts).

Peer environments acted as reinforcement zones for male users, while for female users, they were often spaces of dual tension—support and judgment.

‘My friends laughed when I coughed my first smoke. They pushed me until it felt normal.’ — Male Student

5.9.2. Resistance and Quitting Behavior

Communication also played a role in cessation attempts. Male teachers were more likely to publicly declare their intention to quit, using it as a moral or pedagogical message.

41.7% of male teachers had communicated attempts to quit.

Only 12.5% of female teachers had discussed quitting publicly, citing fear of backlash for even admitting usage.

‘I told my students I’d quit. I wanted them to see me as a role model.’ — Male Teacher, Rajshahi

Conversely, some female respondents used coded communication to signal their distress and desire to stop, including references to ‘bad habits’ or ‘health worries,’ without naming tobacco directly.

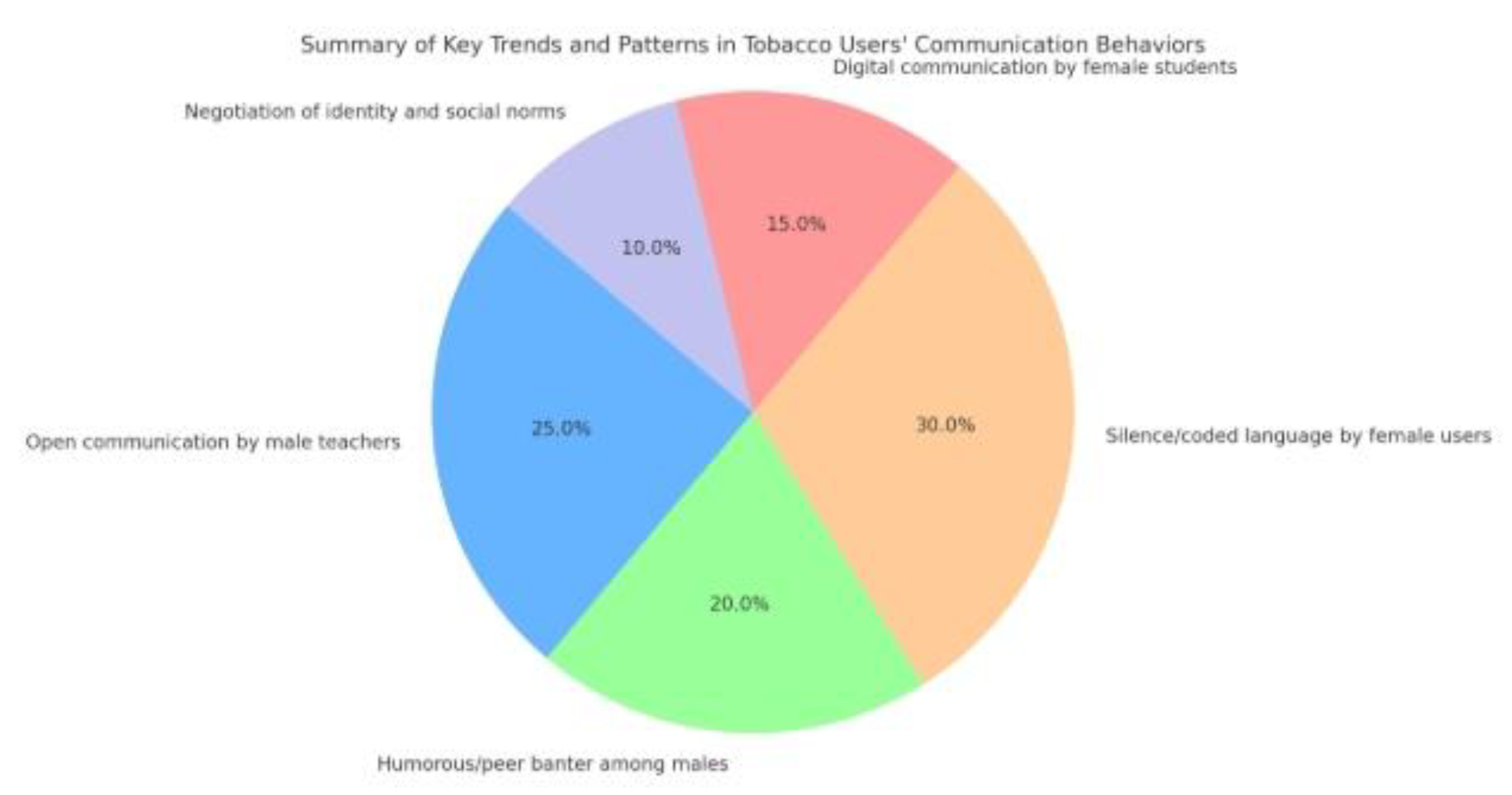

5.10. Summary of Key Trends and Patterns

| Theme |

Male Teachers |

Male Students |

Female Teachers |

Female Students |

| Tobacco Usage Type |

Smoking |

Smoking |

Smokeless, mixed |

Minimal, discreet |

| Disclosure Behavior |

Moderate, selective |

Open, peer-based |

Concealed, selective |

Mostly concealed |

| Communication Channels |

Face-to-face, online |

Online, social media |

Private conversation |

Avoidant, coded |

| Media Influence |

Moderate |

High |

Critical of media |

Avoidant |

| Peer Influence |

Moderate |

High |

Low |

Moderate |

| Institutional Support |

Limited |

Skeptical |

Disengaged |

Absent |

| Stigma Experience |

Low |

Low |

High |

Very high |

| Desire to Quit (Communicated) |

Moderate |

Low |

Concealed |

High (private) |

The findings of this study underline that tobacco users’ communication behaviors are shaped by complex interplays of gender, institutional culture, digital environments, and social stigma. Male users often experience a permissive environment enabling open discourse, while female users operate under cultural and digital surveillance that reinforces silence and shame. These differences necessitate tailored communication strategies and policy interventions that consider the social scripts and gendered realities in Bangladeshi university settings.

Figure 3.

Summary of Key Trends and Patterns.

Figure 3.

Summary of Key Trends and Patterns.

6. Discussion

This section delves into the interpretation of key findings from the study, contextualizing them within existing literature, theoretical paradigms, and the socio-cultural fabric of Bangladesh. The comparative analysis of tobacco users' communication behaviors between male and female university teachers and students reveals complex layers of identity negotiation, stigma management, cultural conformity, and resistance. It also uncovers how digital platforms mediate behavioral and discursive patterns around tobacco use.

6.1. Gendered Scripts and Social Identity Performance

The data clearly indicate that communication around tobacco use is heavily shaped by gendered social scripts. Male users—particularly students—engaged in open, performative displays of tobacco consumption, often using it as a tool for social bonding, rebellion, or identity assertion. This aligns with Connell’s (1995) concept of hegemonic masculinity, where behaviors like smoking are normalized and valorized as markers of dominance, autonomy, or coolness.

In contrast, female users are caught between conventional gender norms and personal autonomy. Goffman's (1959) dramaturgical theory is relevant here—female smokers operate with a ‘backstage’ identity, revealing their usage only in intimate spaces while crafting a public persona aligned with cultural expectations of femininity and propriety.

This duality reflects symbolic interactionism in action, where meanings are negotiated in social contexts. For female users, tobacco use becomes a stigmatized identity (Goffman, 1963), concealed due to fear of social sanction. This fear is not unfounded: society often frames female smokers as immoral, deviant, or irresponsible, exacerbating the burden of silence.

6.2. Communication Ecologies and Power Dynamics

This study reaffirms that communication is not a neutral act; rather, it is deeply embedded in power structures. Female teachers and students self-censor discussions around tobacco use due to institutional surveillance, familial expectations, and digital exposure. Their behavior reflects Foucault’s (1977) notion of disciplinary power, where surveillance produces internalized regulation.

Digital media, while seemingly a space for free expression, reproduces these power structures. Female participants described Facebook, WhatsApp, and Messenger as potential sources of shame or surveillance. Their avoidance of digital expression contrasts with male users who dominate these platforms with open references to tobacco use—often with humor or pride.

This reinforces a gendered digital divide in health discourse. While male users exploit communication spaces to reinforce communal bonding or perform masculinity, female users are marginalized in both online and offline health-related dialogues, creating a disparity in access to cessation support and peer advocacy.

6.3. Tobacco Use as Coping and Resistance

For many users, tobacco is a mechanism for coping with academic stress, emotional burden, and social alienation. Students—especially males—reported that tobacco helps them navigate loneliness, deadlines, and performance pressures. Teachers, on the other hand, reflected on tobacco use as a habit formed during earlier years, often now viewed as burdensome or unhealthy.

However, tobacco also serves as a tool of resistance. Some female respondents framed their secretive use as an act of quiet defiance against patriarchal norms. Their behavior resonates with James C. Scott’s (1990) concept of ‘hidden transcripts’, where subjugated groups develop covert ways of expressing resistance without open confrontation.

Thus, communication behavior is not just about tobacco—it reflects broader negotiations of identity, autonomy, and social position. These expressions—however coded—illustrate the push and pull between conformity and dissent within institutional and gendered hierarchies.

6.4. The Role of Institutions and Cultural Silence

Universities in Bangladesh appear to provide limited institutional support or open dialogue about tobacco use. Both teachers and students noted the absence of anti-smoking campaigns, counseling services, or communication forums for cessation support. Cultural silence around female tobacco use further marginalizes affected individuals.

This institutional inertia contributes to normalization among males and pathologization among females. Male-dominated peer groups offer reinforcement and validation, while female users remain isolated. The absence of gender-sensitive discourse around tobacco contributes to inequitable access to health communication, reflecting structural violence (Galtung, 1969).

Moreover, the bureaucratic and moralistic framing of tobacco policies deters meaningful engagement. Many participants viewed existing anti-smoking posters or rules as performative rather than persuasive, disconnected from their lived realities.

6.5. Internal Conflict and Identity Dissonance

Particularly among female teachers and students, tobacco use evoked psychological tension and identity dissonance. Many participants spoke about guilt, shame, and secrecy. This aligns with Festinger’s (1957) theory of cognitive dissonance, where individuals experience discomfort when behavior conflicts with self-image or social norms.

The dissonance was more profound in educated women, who understood the health risks but continued usage due to emotional dependence, lack of support, or rebellion. In contrast, male users—especially younger students—rarely expressed such dissonance, reflecting their internalization of permissive norms.

This divergence indicates that psychosocial costs of tobacco use are unequally distributed. Female users carry not only the health burden but also the emotional and reputational cost, which affects their willingness to seek help, engage in discussions, or advocate for themselves.

6.6. Implications for Communication Theory and Public Health

The findings of this study contribute to communication theory by emphasizing the intersectionality of behavior, discourse, and power. They underscore how communication about health behaviors is shaped not merely by knowledge or risk perception but also by social identity, cultural narratives, and media representation.

From a public health perspective, this study calls for a paradigm shift. Traditional tobacco cessation models often emphasize rational decision-making, overlooking social stigma, gender roles, and digital behavior patterns. Without addressing these underlying dynamics, interventions will fail to reach marginalized users—particularly women—who remain hidden from mainstream health discourses.

6.7. Comparative Reflections with Global Literature

While tobacco use is declining in many Western contexts due to comprehensive public health campaigns, South Asian countries like Bangladesh are witnessing stagnation or even resurgence—especially in youth and female segments. Similar gender-based concealment patterns are observed in studies from India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka (Thakur et al., 2021; Alam & Mahmud, 2020).

This study builds on regional scholarship but adds a unique lens by focusing on communication behaviors in academic institutions—spaces that are paradoxically sites of both enlightenment and exclusion. In doing so, it bridges gaps between public health, gender studies, and digital communication research.

The discussion reveals that communication behaviors surrounding tobacco use in Bangladeshi universities are gendered, socially conditioned, and mediated through complex power structures. Male users occupy communicative dominance in both digital and physical spaces, while female users navigate stigma through coded silence. Institutions, media, and cultural norms play critical roles in reinforcing these dynamics.

Understanding these communication ecologies is essential for crafting effective, inclusive, and context-sensitive health interventions. Tobacco use is not merely a medical or behavioral issue—it is a discursive and identity-based practice that demands a holistic, gender-aware response.

7. Policy Implications and Recommendations

This section outlines actionable policy recommendations grounded in the study's findings, focusing on gender-sensitive, communication-oriented, and institutionally feasible interventions. The current tobacco control policies in Bangladesh, while present on paper, remain largely ineffective due to sociocultural blind spots, lack of enforcement, and absence of participatory communication frameworks—especially within academic institutions.

7.1. Reframing Tobacco Policy Through a Gender Lens

Current anti-tobacco policies in Bangladesh—under the Smoking and Tobacco Products Usage (Control) Act, 2005 (amended in 2013)—are largely gender-neutral in design but gender-exclusive in outcome. This research shows that women, particularly students and teachers, remain excluded from both policy outreach and support systems due to societal stigma and institutional silence.

Integrate gender-sensitive language and visual representation in all tobacco control messaging.

Commission studies that focus specifically on female tobacco users, to inform targeted interventions.

Develop confidential, female-friendly cessation support systems on university campuses, such as helplines, online counseling, or peer-support networks.

7.2. Institutionalizing Tobacco Dialogue in Academic Spaces

Universities are not merely educational institutions—they are also socialization hubs where behaviors are learned, practiced, and replicated. Despite the formal ban on tobacco use in educational institutions, this study shows that smoking is widespread and normalized, especially among male students and, to some extent, teachers.

Establish a Tobacco-Free Campus Policy that goes beyond prohibition and includes education, dialogue, and participatory activities.

Set up University Health Communication Committees (UHCC) comprising students, teachers, health experts, and counselors to:

-Design and run awareness campaigns.

-Conduct open forums and workshops on stress, addiction, and stigma.

-Coordinate with national anti-tobacco programs.

Allocate university funding for tobacco prevention as part of mental health initiatives, recognizing the role of stress and peer pressure in usage.

7.3. Creating Safe Digital Spaces for Dialogue

This research shows that digital platforms are double-edged: while male users engage openly, female users retreat into silence due to fear of judgment. In the age of digital learning and online interaction, it is imperative to reimagine these spaces as safe, inclusive, and educative.

Launch anonymous digital platforms or chatbots where students and faculty can discuss tobacco-related concerns, seek guidance, or connect with counselors without fear of exposure.

Collaborate with influencers, alumni, and digital content creators to develop counter-narratives on tobacco glamorization—especially those that target university youth culture.

Monitor and flag tobacco-promotion trends on campus groups, pages, and chats, and replace them with pro-health discourse, while safeguarding digital rights.

7.4. From Prohibition to Prevention: Reforming Communication Strategies

Current anti-tobacco messages in Bangladesh are largely punitive and moralistic, focusing on prohibition and fear (e.g., graphic warning labels). While these may work to some extent, they fail to engage youth meaningfully and may even reinforce taboo around female usage.

Shift from didactic, top-down communication to interactive, participatory models rooted in students’ and teachers’ lived experiences.

Develop storytelling-based campaigns that highlight real-life experiences of cessation, harm, and resistance—especially female narratives.

Integrate peer education programs where trained student ambassadors engage in one-on-one and group dialogues about tobacco use, stigma, and alternatives.

Partner with NGOs, public health agencies, and university clinics to provide on-site and digital cessation services tailored to the academic calendar.

Introduce wellness weeks, de-addiction days, and anti-stress workshops that address tobacco use as part of broader health awareness.

Promote tobacco-free alternatives such as mindfulness clubs, creative expression workshops, and recreational activities that help manage stress and boredom.

The cultural framing of female tobacco users as immoral or deviant serves as a structural barrier to dialogue, support, and inclusion. This demands a broader sociocultural shift, particularly in university environments that claim to foster intellectual freedom and critical thinking.

Encourage curriculum inclusion of health communication, gender, and addiction modules in sociology, media, and public health programs.

Conduct theatre, documentary screenings, or debate events on topics like stigma, addiction, and freedom to create reflexive spaces.

Promote faculty mentorship programs where teachers are trained to identify and support students who may be silently struggling with addiction and stigma.

7.5. Integrating Surveillance, Rights, and Support

While some surveillance of tobacco use is necessary for enforcement, this study warns against punitive, surveillance-heavy strategies that deter help-seeking—especially among female students.

Replace hostile surveillance with supportive surveillance, where the aim is to understand usage patterns and provide intervention—not to shame or punish.

Ensure all policies are rights-based, offering students protection from harassment, confidentiality in counseling, and avenues for appeal.

Make data collection and program evaluation participatory, involving students and faculty in regular assessments of tobacco communication effectiveness.

7.6. National-Level Implications: Policy and Advocacy

The implications of this study go beyond universities. The findings highlight how tobacco control policies at the national level must integrate communication, gender, and education sectors.

Advocate for a National Youth Tobacco Communication Policy, developed in partnership with the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Ministry of Education, and civil society.

Reform the National Tobacco Control Cell (NTCC) to include communication experts, gender specialists, and academic representatives.

Launch a ‘Voices from Campus’ national campaign to collect, showcase, and act on real stories of youth tobacco use and resistance across universities and colleges.

7.7. International Partnerships and Funding

Global bodies such as the WHO, Bloomberg Philanthropies, and the Global Tobacco Control network already support Bangladesh in tobacco reduction. However, there is a gap in funding youth- and gender-focused communication interventions.

Mobilize international support for pilot projects on campus tobacco communication, particularly ones that can be scaled nationwide.

Advocate for inclusion of ‘gender and youth communication’ as a priority research area under international tobacco grants and SDG-linked funding.

Develop cross-cultural knowledge exchanges between South Asian universities to share best practices and co-create innovative interventions.

Effective tobacco control in Bangladesh—especially among university students and faculty—requires a shift from behavioral blame to structural support, from punitive bans to participatory dialogue, and from generic campaigns to gender-sensitive frameworks. Universities, as formative institutions, must lead this transformation.

The recommendations outlined above are not just preventive—they are empowering, designed to foster safer communication spaces, dismantle stigma, and equip both male and female tobacco users with the resources they need to make informed, autonomous choices.

8. Conclusion and Future Research Directions

8.1. Conclusion

This study set out to investigate the communication behaviors of tobacco users among university male and female teachers and students in Bangladesh. Through a comparative analysis grounded in both quantitative and qualitative data, the research has offered deep insights into how gender, institutional culture, stigma, and power dynamics shape the ways in which tobacco users express, conceal, justify, or challenge their behavior.

The findings reveal a paradox at the heart of tobacco discourse in academia: while university campuses are often regarded as spaces of enlightenment and health consciousness, they simultaneously harbor a culture of silent normalization, particularly among male students and teachers. For women, the reality is more layered. The stigma and cultural taboos surrounding female tobacco use create zones of exclusion, where communication is muted or entirely absent. Despite being tobacco users, women often find themselves denied voice, visibility, and support due to structural constraints and patriarchal narratives.

The research identifies communication behavior not as a static or isolated practice but as a dynamic process shaped by social norms, digital environments, institutional practices, and gendered power structures. Whether through silence, coded language, humor, or online anonymity, tobacco users actively negotiate their identities and resist marginalization. Teachers—particularly male faculty—emerge both as users and informal influencers, suggesting a vertical dynamic in how norms are maintained or challenged within academic spaces.

From the policy perspective, this study underscores the urgent need for gender-sensitive, inclusive, and communication-centric tobacco interventions. A purely regulatory or punitive approach fails to address the nuances of lived experience, especially in educational institutions where identity formation, peer influence, and social performance are tightly interwoven with behavioral choices.

In sum, tobacco use in universities is not just a health issue—it is a communication phenomenon, and to address it effectively, we must engage with it on those terms.

8.2. Contributions to Knowledge

This study contributes to several scholarly and policy domains:

Health Communication: By focusing on how tobacco use is communicated and negotiated, the study expands the field of health communication to include micro-level discourse practices in educational settings.

Gender Studies: It brings much-needed attention to the gendered dimensions of addiction and stigma, showing how patriarchal structures silence female tobacco users.

Addiction Sociology: The study highlights the social and relational dynamics of tobacco use, moving beyond the individualistic framing common in cessation literature.

Educational Policy: It offers a foundation for integrating health and communication policy within university governance, suggesting a model for tobacco-free but dialogue-rich campuses.

8.3. Limitations of the Study

While this research offers robust and original findings, certain limitations must be acknowledged:

Sample Scope: Although the sample included public and private universities across major cities, rural and peripheral academic institutions were not studied. Their socio-cultural contexts might reveal different communication patterns.

Self-Reporting Bias: Some respondents may have underreported their tobacco use or communication behaviors, particularly female participants, due to stigma or social desirability bias.

Temporal Constraints: The cross-sectional nature of the data collection provides a snapshot rather than a longitudinal understanding of behavior change over time.

Lack of Biochemical Validation: The study relied on self-disclosure of tobacco use rather than biochemical verification (e.g., cotinine levels), which may limit the accuracy of usage reports.

8.4. Directions for Future Research

To build on this study’s findings, future research can take several promising directions:

1. Longitudinal Communication Behavior Studies

Following university students and faculty over multiple years can offer deeper insight into how communication behaviors evolve over time, particularly with respect to stress, academic transitions, and institutional interventions.

2. Rural and Non-Metropolitan Universities

Future studies should expand to include universities in less urbanized areas, where tobacco use may be influenced by different socio-economic and cultural factors. These contexts may also feature different gender dynamics and communication patterns.

3. Intersectionality and Marginal Identities

Expanding the research to include LGBTQ+ students, non-binary individuals, and religious minorities could reveal how tobacco-related communication intersects with other forms of identity-based stigma and resistance.

4. Digital Ethnography

A focused exploration of online communities, memes, comment threads, and social media posts among university students can illuminate the covert digital communication practices surrounding tobacco use, particularly for women and marginalized groups.

5. Comparative South Asian Studies

Comparative cross-national studies among universities in India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Nepal could situate the Bangladeshi experience within a broader South Asian context, exploring regional commonalities and divergences in tobacco culture and communication.

6. Intervention-Based Research

Future researchers can design and implement experimental health communication interventions (e.g., peer-led dialogues, gamified cessation apps, anonymous forums) to evaluate their effectiveness in altering both tobacco use and related communication behaviors.

7. Role of Faculty as Communication Catalysts

Further exploration of how teachers—especially male faculty—reinforce or challenge tobacco norms within departments, classrooms, and informal settings is essential. Such studies can help formulate training programs for faculty as active agents in campus health promotion.

8.5. Final Touched

Understanding tobacco use through the lens of communication behavior invites a more empathetic, inclusive, and strategic approach to public health. This study affirms that in order to reduce tobacco use on university campuses in Bangladesh, we must first dismantle the walls of silence, stigma, and structural indifference. Communication is not merely a tool—it is the terrain upon which health, identity, and resistance are negotiated.

Future efforts—both academic and policy-oriented—must harness this terrain, not just to prevent disease but to empower individuals and transform institutions. Only then can we build universities that are not just tobacco-free but also voice-rich, justice-sensitive, and health-centered.