Submitted:

22 May 2025

Posted:

22 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

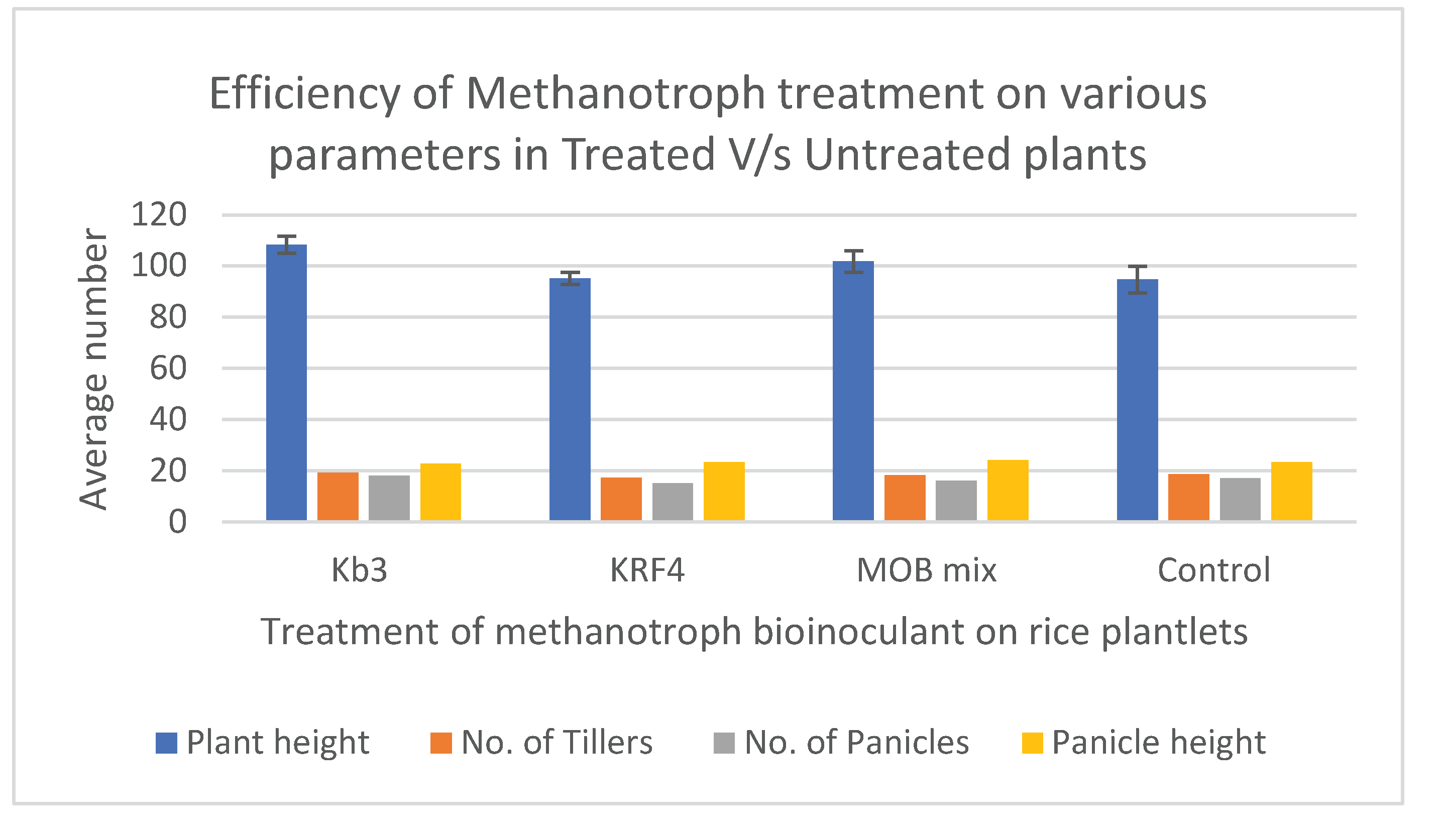

2.1. Overall Health of the Plants and Early Flowering Seen in Methylomonas Kb3-Treated Plants

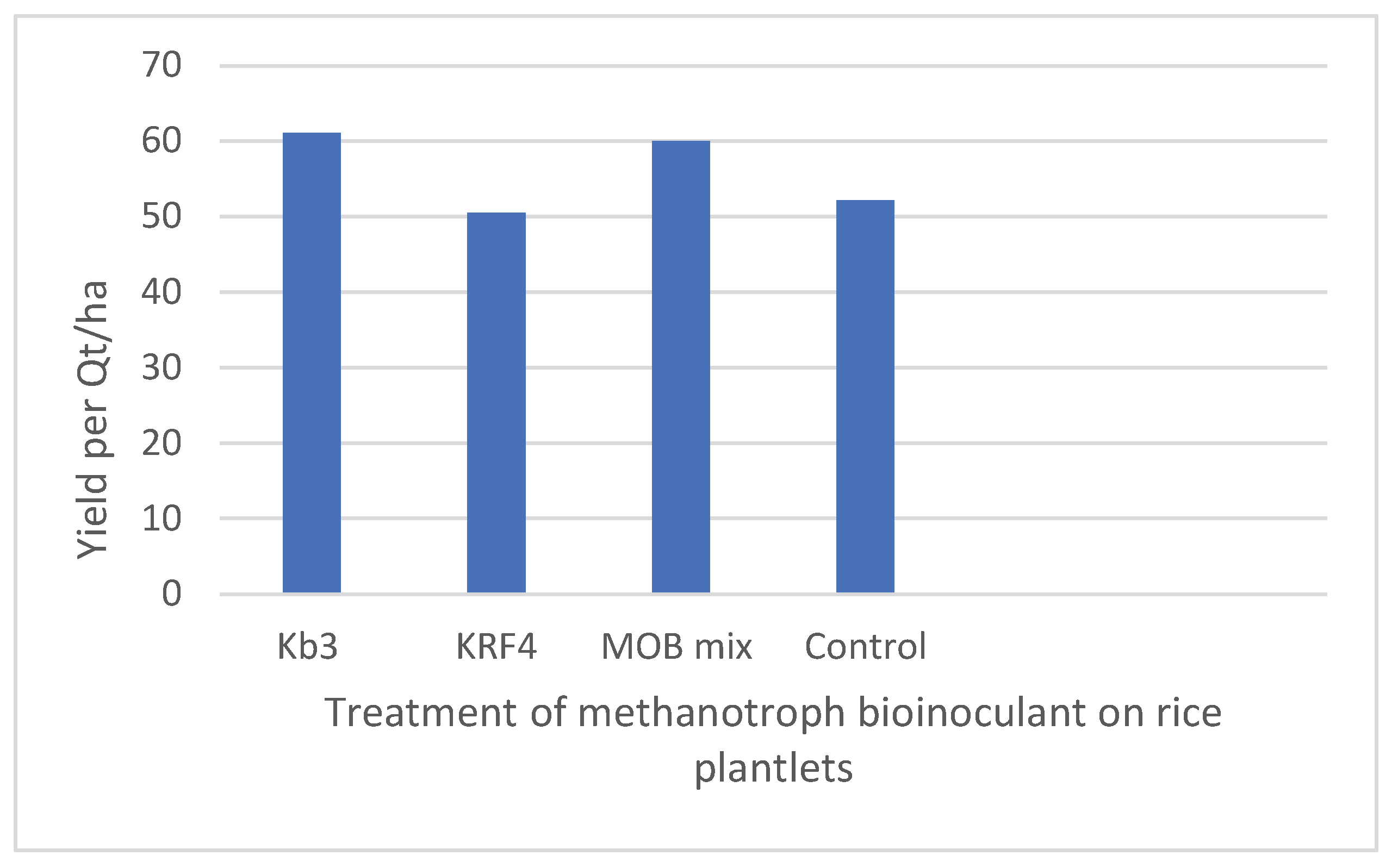

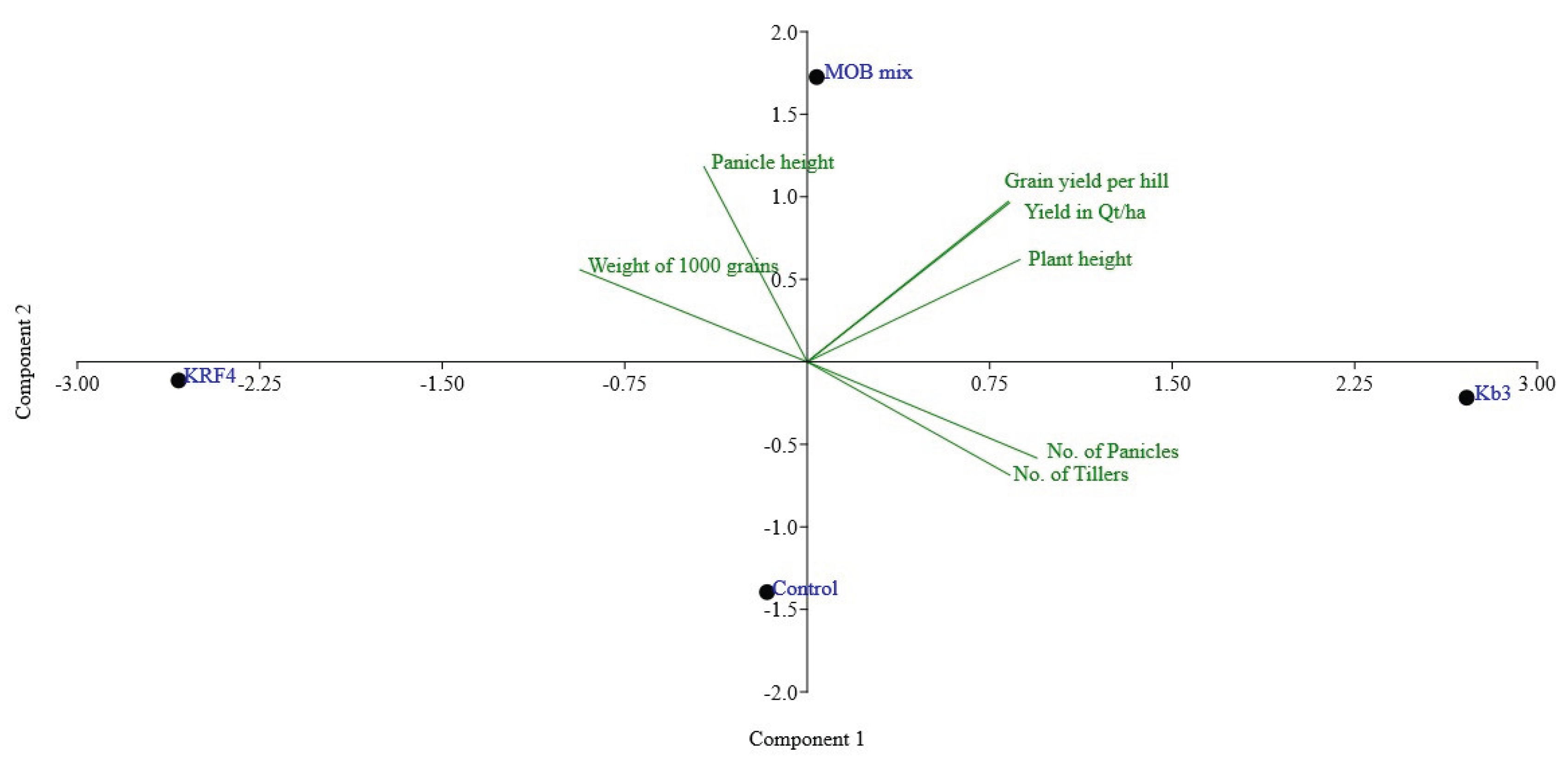

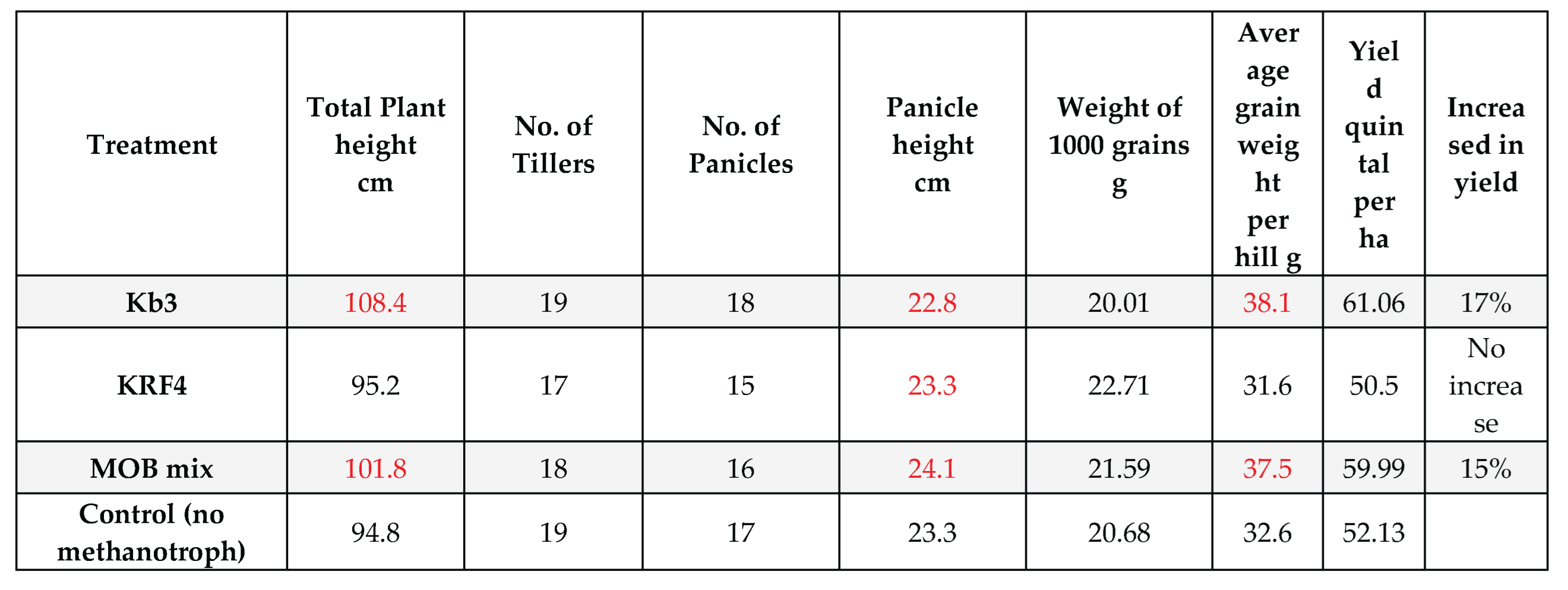

2.2. Enhanced Growth Yield, Plant Height in Methylomonas Kb3-Treated Plants

2.3. Re-Isolation of Methanotrophs

3. Discussion

3.1. Need for Novel Bio-Inoculants in Rice

3.2. Nitrogen Fixation by Methanotrophs

3.3. Methanotrophs as a New Class of Bio-Inoculants

3.4. A Methanotroph, Methylococcus Capsulatus, Has Been Shown to Act as a Bio-Stimulant on Multiple Levels

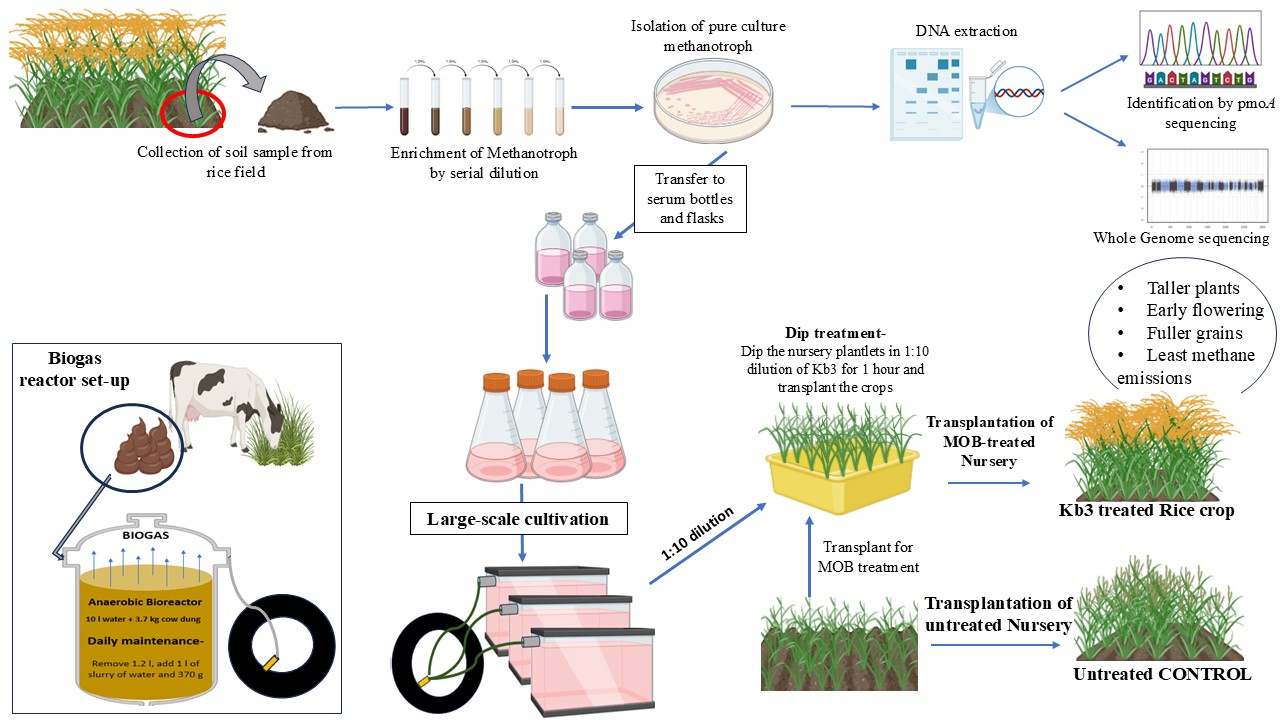

4. Materials and Methods

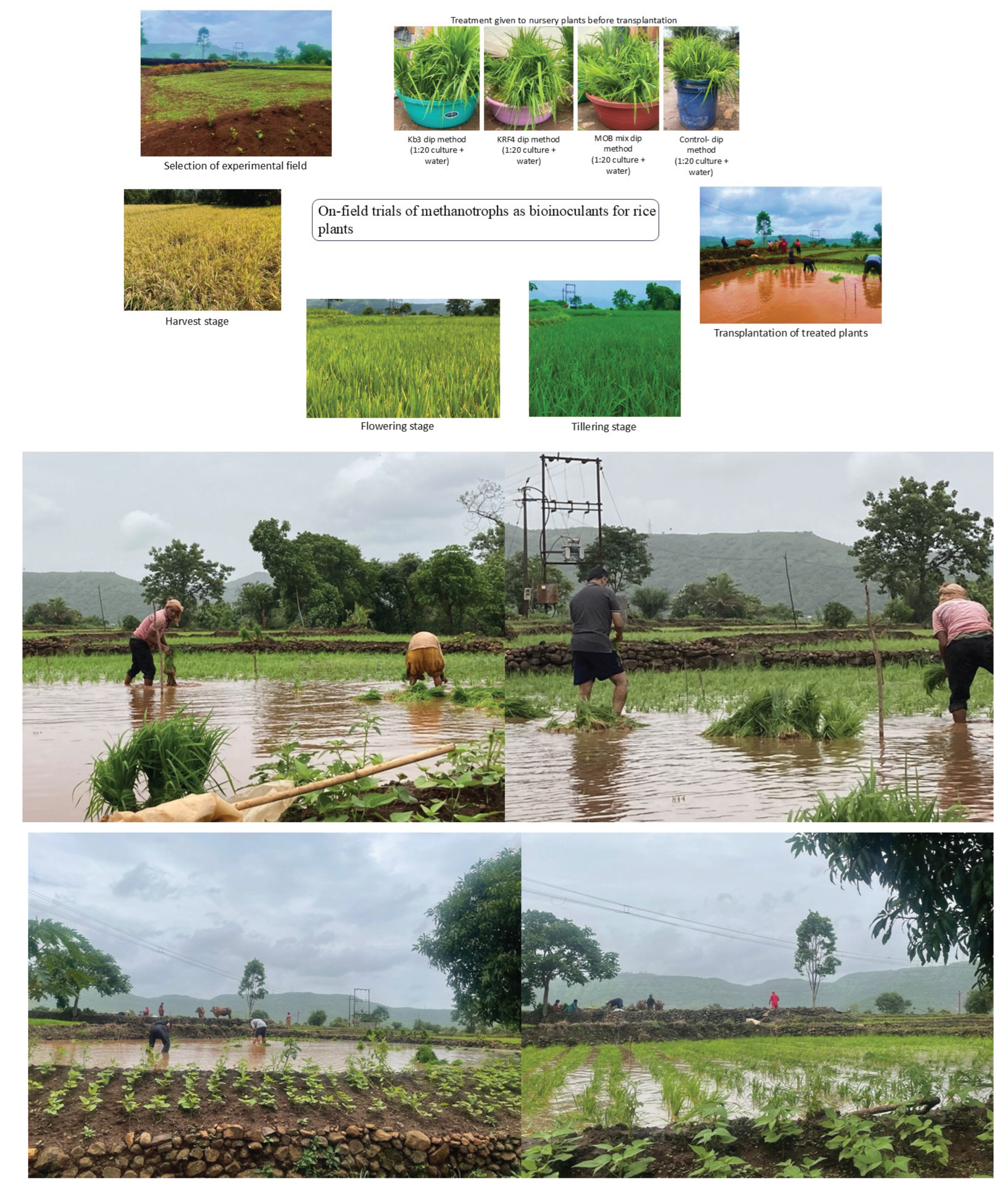

4.1. Selection of a Rice Field for the Field Experiment

4.2. Treatment of Rice Plantlets with Selected Methanotroph Strains

4.3. Data Collection, Farm Visits and Soil Sampling

4.4. Soil Sampling for Enrichment of Methanotrophs

4.5. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MOB | Methane-oxidizing bacteria |

References

- Auman AJ, Speake CC, Lidstrom ME (2001) nifH Sequences and Nitrogen Fixation in Type I and Type II Methanotrophs. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 67:4009-4016.

- Bahulikar RA, Chaluvadi SR, Torres-Jerez I, Mosali J, Bennetzen JL, Udvardi M (2021) Nitrogen Fertilization Reduces Nitrogen Fixation Activity of Diverse Diazotrophs in Switchgrass Roots. Phytobiomes . [CrossRef]

- Canadell JG, Monteiro PMS (2021) Global Carbon and Other Biogeochemical Cycles and Feedback. In: IPCC (ed) Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the IPCC, pp 673-779.

- Conrad R (2009) The global methane cycle: recent advances in understanding the microbial processes involved. Environmental Microbiology Reports 1:285-292.

- Ferrando L, Tarlera S (2009) Activity and diversity of methanotrophs in the soil-water interface and rhizospheric soil from a flooded temperate rice field. J Appl Microbiol 106:306-316.

- Ganesan A, Rigby M, Lunt MF, Parker RJ, Boesch H, Goulding N, Umezawa T, Zahn A, Chatterjee A, Prinn RG, Tiwari YK, Schoot Mvd, Krummel PB (2017) Atmospheric observations show accurate reporting and little growth in India’s methane emissions. Nature Communications 8:836.

- Gilbert B, Frenzel P (1998) Rice roots and CH4 oxidation: the activity of bacteria, their distribution and the microenvironment. Soil Biol Biochem 30:1903-1916.

- Hammer O, Harper DAT, Ryan PD (2001) PAST: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Paleontologica Electronica 4:9.

- Hanson RS, Hanson TE (1996) Methanotrophic bacteria. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 60:439-471.

- Hardoim PR, Andreote FD, Reinhold-Hurek B, Sessitsch A, van Overbeek LS, van Elsas JD (2011) Rice root-associated bacteria: insights into community structures across 10 cultivars. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 77:154-164.

- Kumar SR, David EM, Pavithra GJ, Kumar GS, Subbian E (2024) Methane-derived microbial biostimulant reduces greenhouse gas emissions and improves rice yield. Frontiers in Plant Science 15.

- Mohite J, Khatri K, Pardhi K, Manvi SS, Jadhav R, Rathod S, Rahalkar MC (2023) Exploring the potential of methanotrophs for plant growth promotion in rice agriculture. Methane 2:361-371.

- Murrell JC, Dalton H (1983) Nitrogen-fixation in obligate methanotrophs. Journal of General Microbiology 129:3481-3486.

- Orozco-Mosqueda MDC, Rocha-Granados MDC, Glick BR, Santoyo G (2018) Microbiome engineering to improve biocontrol and plant growth-promoting mechanisms. Microbiological Research 208:25-31.

- Pandit PS, Rahalkar M, Dhakephalkar P, Ranade DR, Pore S, Arora P, Kapse N (2016) Deciphering community structure of methanotrophs dwelling in rice rhizospheres of an Indian rice field using cultivation and cultivation independent approaches. Microbial Ecology 71:634-644.

- Pandit PS, Ranade DR, Dhakephalkar PK, Rahalkar MC (2016) A pmoA-based study reveals dominance of yet uncultured Type I methanotrophs in rhizospheres of an organically fertilized rice field in India. 3 Biotech 6:135.

- Pandit PS, Rahalkar MC (2019) Renaming of ‘Candidatus Methylocucumis oryzae’ as Methylocucumis oryzae gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel Type I methanotroph isolated from India. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 112:955-959.

- Rahalkar M, Khatri K, Pandit PS, Bahulikar R, Mohite JA (2021) Cultivation of Important Methanotrophs From Indian Rice Fields. Frontiers in Microbiology:1-15.

- Rahalkar MC, Pandit P (2018) Genome-based insights into a putative novel Methylomonas species (strain Kb3), isolated from an Indian rice field. Gene Reports 13:9-13.

- Rahalkar MC, Khatri K, Pandit PS, Dhakephalkar PK (2019) A putative novel Methylobacter member (KRF1) from the globally important Methylobacter clade 2: cultivation and salient draft genome features. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 112:1399-1408.

- Rahalkar MC, Khatri K, Mohite J, Pandit P, Bahulikar R (2020) A novel Type I methanotroph Methylolobus aquaticus gen. nov. sp. nov. isolated from a tropical wetland. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 113:959-971.

- Rahalkar MC, Khatri K, Pandit P, Mohite J (2024) Polyphasic Characterization of Ca. Methylomicrobium oryzae: A Methanotroph Isolated from Rice Fields. Indian Journal of Microbiology.

- Scagliola M, Valentinuzzi F, Mimmo T, Cesco S, C C, Y P (2021) Bioinoculants as Promising Complement of Chemical Fertilizers for a More Sustainable Agricultural Practice. Front Sustain Food Syst 4:622169:1-12.

- Tallapragada P, Seshagiri S (2017) Application of Bioinoculants for Sustainable Agriculture. In: Kumar V, Kumar M, Sharma S, Prasad R (eds) Probiotics and Plant Health. Springer, Singapore, pp 473–495.

- The Fertilizer Association of India ND (2019) FAI Annual Seminar – 2019 on New Approach to Fertilizer Sector.

- Thomas L, Singh I (2019) Microbial Biofertilizers: Types and Applications. In: Giri B, Prasad R, Wu Q, Varma A (eds) Biofertilizers for Sustainable Agriculture and Environment Springer, pp 1-19.

- Wu L, Ma K, Lu Y (2009) Rice roots select for type I methanotrophs in rice field soil. Systematic and applied microbiology 32:421-428.

- Yuan J, Yuan Y, Zhu Y, Linkui Cao (2018) Effects of different fertilizers on methane emissions and methanogenic community structures in paddy rhizosphere soil. Science of The Total Environment 627:770-781.

- Yuanfeng Cai, Yan Zheng, Paul L. E. Bodelier, Conrad R, Jia Z (2016) Conventional methanotrophs are responsible for atmospheric methane oxidation in paddy soils. Nature Communications 11728.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).