Submitted:

14 May 2025

Posted:

14 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability

Acknowledgments

Competing Interests

Ethics approval:

Consent to participate:

Consent to publish:

References

- Aselmann I, Crutzen PJ (1989) Global distribution of natural freshwater wetlands and rice paddies, their net primary productivity, seasonality and possible methane emissions. Journal of Atmospheric Chemistry 8:307-358.

- Belova SE, Kulichevskaya IS, Bodelier PL, Dedysh SN (2013) Methylocystis bryophila sp. nov., a facultatively methanotrophic bacterium from acidic Sphagnum peat, and emended description of the genus Methylocystis (ex Whittenbury et al. 1970) Bowman et al. 1993. International journal of systematic and evolutionary microbiology 63:1096-1104.

- Bowman J (2016) Methylococcaceae. In: Whitman W (ed) Bergey’s Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria. John Wliey and Sons, USA.

- Bowman JS, Ducklow HW (2015) Microbial communities can be described by metabolic structure: a general framework and application to a seasonally variable, depth-stratified microbial community from the coastal West Antarctic Peninsula. PloS One 10.

- Conrad R (2009) The global methane cycle: recent advances in understanding the microbial processes involved. Environmental Microbiology Reports 1:285-292. [CrossRef]

- Dall’Osto L, Bassi R, Ruban A (2014) Photoprotective Mechanisms: Carotenoids. In: S.M. Theg, Wollman FA (eds) Plastid Biology, Advances in Plant Biology. Springer, New York.

- Dedysh SN, Knief C (2018) Diversity and phylogeny of described aerobic methanotrophs. In: Kalyuzhnaya MG, Xing X-H (eds) Methane Biocatalysis: Paving the way to sustainability. Springer, pp 17-42.

- Fazli P, Man HC, Shah UKM, Idris A (2013) Characteristics of methanogens and methanotrophs in rice fields: a review. Asia-Pacific Journal of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology 21:3-17.

- Ghashghavi M, Belova SE, Bodelier PLE, Dedysh SN, Kox MAR, Speth DR, Frenzel P, Jetten MSM, Lücker S, Lüke C (2019) Methylotetracoccus oryzae Strain C50C1 Is a Novel Type Ib Gammaproteobacterial Methanotroph Adapted to Freshwater Environments. mSphere 4:e00631-00618. [CrossRef]

- Hanson RS, Hanson TE (1996) Methanotrophic bacteria. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 60:439-471.

- Hu S, Niu Z, Chen Y (2017) Global Wetland Datasets: a Review. Wetlands 37:807-817.

- Knief C (2015) Diversity and habitat preferences of cultivated and uncultivated aerobic methanotrophic bacteria evaluated based on pmoA as molecular marker. Frontiers in Microbiology 6. [CrossRef]

- Lugo AE, Brown S, Brinson MM (1990) Concepts in wetland ecology. Ecosystems of the world, pp 53-85.

- McDonald IR, Bodrossy L, Chen Y, Murell CJ (2008) Molecular ecology techniques for the study of aerobic methanotrophs. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:1305-1315.

- Mohite JA, Manvi SS, Pardhi K, Khatri K, Bahulikar RA, Rahalkar MC (2023) Thermotolerant methanotrophs belonging to the Methylocaldum genus dominate the methanotroph communities in biogas slurry and cattle dung: A culture-based study from India. Environmental Research 228:1-6. [CrossRef]

- Rahalkar MC, Patil S, Dhakephalkar PK, Bahulikar RA (2018) Cultivated methanotrophs associated with rhizospheres of traditional rice landraces from Western India belong to Methylocaldum and Methylocystis. 3 Biotech 8. [CrossRef]

- Rahalkar MC, Khatri K, Mohite J, Pandit P, Bahulikar R (2020) A novel Type I methanotroph Methylolobus aquaticus gen. nov. sp. nov. isolated from a tropical wetland. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 113:959-971.

- Takeuchi M, Kamagata Y, Oshima K, Hanada S, Tamaki H, Marumo K, Sakata S (2014) Methylocaldum marinum sp. nov., a thermotolerant, methane-oxidizing bacterium isolated from marine sediments, and emended description of the genus Methylocaldum. International Journal of systematic and evolutionary microbiology 64:3240-3246.

- Wang Z, Zeng D, Patrick WH (1996) Methane emissions from natural wetlands. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 42:143-161.

- Wartiainen I, Hestnes AG, McDonald IR, Svenning MM (2006) Methylocystis rosea sp. nov., a novel methanotrophic bacterium from Arctic wetland soil, Svalbard, Norway (78° N) Free. International Journal of systematic and evolutionary microbiology 56:541-547.

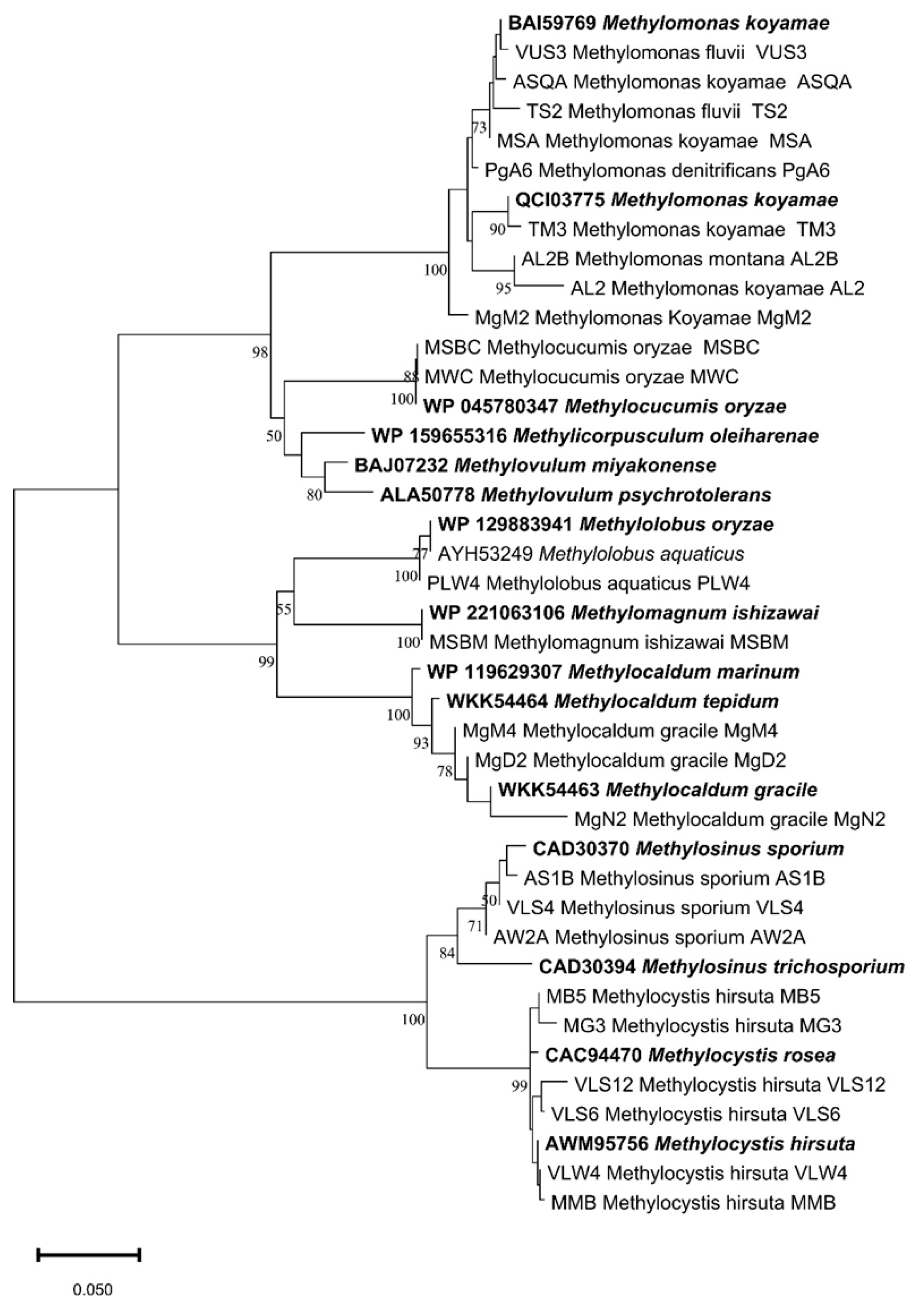

| Sampling details | Dilution used for isolation of methanotrophs | Representative cultures | Identification using pmoA gene | |||||

| Sampling site | Sample name | Sampling date | Strain name | GeneBank accession number | Nearest match (with type cultures) | % similarity (nucleotide) | % similarity (protein) |

|

|

Venna Lake Sediments |

soil sample | 28.12.2022 | 10-12 | VLS12 | PQ821915 |

Methylocystis hirsuta CSC1 |

97.25 | 98.60 |

| soil sample | 28.12.2022 | 10-6 | VLS6 | - | Methylocystis hirsuta CSC1 | 97.70 | 98.56 | |

| soil sample |

28.12.2022 | 10-4 | VLS4 | PQ821914 |

Methylosinus sporium ATCC |

95.06 | 98.55 | |

| soil sample | 28.12.2022 | 10-3 | VUS3 | PQ821926 | Methylomonas fluvii EbB | 95.19 | 100 | |

| water sample | 28.12.2022 | 10-4 | VLW4 | PQ821917 | Methylocystis hirsuta strain CSC1 | 97.35 | 97.93 | |

| soil sample | 28.12.2022 | 10-5 | MB5 | PQ821931 | Methylocystis hirsuta strain CSC1 | 97.12 | 98.66 | |

| Vetal hill Pond | Stone Sample |

15-01-2024 | 10-2 | AS1B | PQ821919 | Methylosinus sporium strain ATCC 35069 | 99.31 | 98.61 |

| water sample | 15-01-2024 | 10-8 | AW2A | PQ821929 | Methylosinus sporium strain ATCC 35069 | 95.05 | 97.93 | |

| water sample | 04-02-2024 | 10-2 | ASQA | PQ821920 | Methylomonas koyamae strain Fw12E-Y | 96.12 | 99.31 | |

| Mahatma hill pond | Seaweed Sample |

21-04-2024 | 10-2 | MSBM | PQ821923 | Methylomagnum ishizawai strain RS11D | 99.53 | 99.29 |

| Seaweed sample |

21-04-2024 | 10-6 | MSA | PQ821928 | Methylomonas koyamae strain Fw12E-Y | 95.81 | 100 | |

| Seaweed sample |

21-04-2024 | 10-8 | MSBC | PQ821922 | Methylocucumis oryzae strain Sn 10-6 | 98.66 | 100 | |

| water sample | 21-04-2024 | 10-7 | MWC | PQ821924 | Methylocucumis oryzae strain Sn 10-6 | 98.61 | 100 | |

| Mud sample |

18-12-2023 | 10-3 | TM3 | PQ821925 | Methylomonas koyamae strain Fw12E-Y | 92.47 | 97.18 | |

| Mud sample |

21-04-2024 | 10-5 | MMB | PQ821921 | Methylocystis hirsuta strain CSC1 | 97.46 | 98.62 | |

| Pashan Lake | water sample | 08.07.2023 | 10-2 | PLW2 | PQ821916 | Methylosinus trichosporium strain OB3b | 100 | 99.31 |

| water sample | 08.07.2023 | 10-4 | PLW4 | PQ821918 | Methylolobus aquaticus strain FWC3 | 97.25 | 100 | |

| Tamhini river | sediment | 16-06-2023 | 10-2 | TS2 | PQ821913 | Methylomonas fluvii strain EbB | 95.19 | 98.53 |

| ARI pond | Lotus root sample |

02-01-2024 | 10-2 | AL2 | PQ821908 | Methylomonas koyamae strain Fw12E-Y | 87.79 | 95.16 |

| Lotus root sample |

02-01-2024 | 10-2 | AL2B | PQ821907 | Methylomonas montana strain MW1 | 89.56 | 97.90 | |

|

Paragrass BAIF pond |

Root sample | 09-01-2024 | 10-6 | PgA6 | PQ821927 | Methylomonas denitrificans strain FJG1 | 94.82 | 98.03 |

|

Mumbai Mangroves |

soil sample | 21-09-2023 | 10-2 | MgM2 | PQ821911 | Methylomonas koyamae strain Fw12E-Y | 91.88 | 97.14 |

| soil sample | 21-09-2023 | 10-4 | MgM4 | PQ821912 | Methylocaldum gracile strain VKM-14L | 99.18 | 100 | |

| Alibag mangroves | soil sample | 23-03-2023 | 10-3 | MG3 | PQ821909 | Methylocystis hirsuta strain CSC1 | 97.50 | 99.29 |

| soil sample | 23-03-2023 | 10-3 | MgN2 | PQ821930 | Methylocaldum gracile strain VKM-14L | 99.52 | 100 | |

| Diveagar mangroves | soil sample | 29-12-2023 | 10-2 | MgD2 | PQ821910 | Methylocaldum gracile strain VKM-14L | 98.95 | 100 |

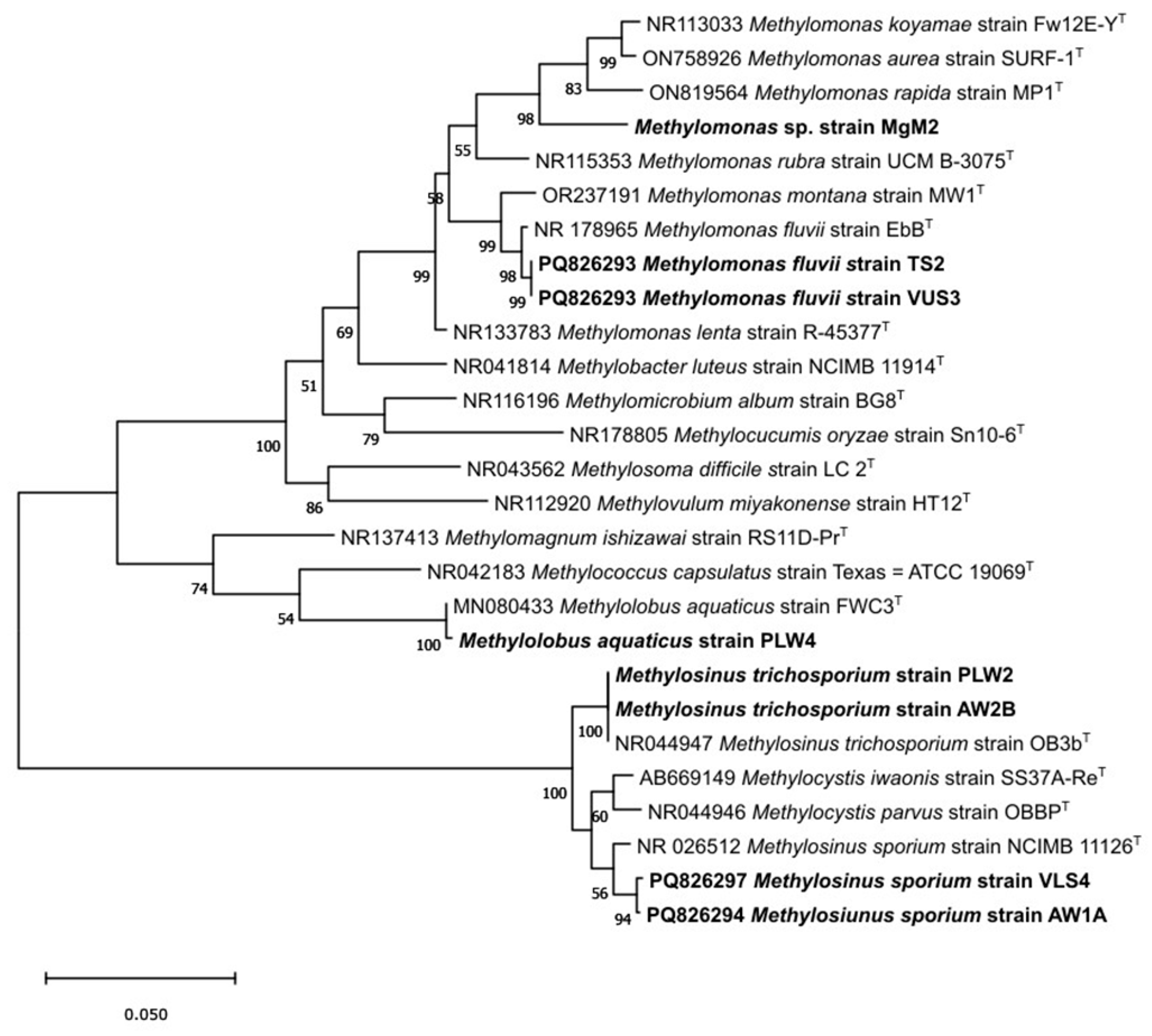

| Sampling details | Dilution used for isolation of methanotrophs | Representative strain | Identification using 16SrRNA gene | ||||

| Sampling site | Sample name | Sampling date | Strain name | Gene accession number | Nearest match with type strain | % similarity | |

| Vetal hill pond | Water sample | 16-01-2023 | 10-8 | AW1A | PQ826297 |

Methylomonas sporium strain NCIMB 11126 | 98.89 |

| Tamhini river | sediment | 16-06-2023 | 10-2 | TS2 | PQ826293 |

Methylomonas fluvii strain EbB | 99.41 |

| Venna lake | Soil sample | 03-01-23 | 10-3 | VUS3 | PQ826293 |

Methylomonas fluvii strain EbB | 99.41 |

| Venna Lake | Soil sample | 03-01-2023 | 10-4 | VLS4 | PQ826294 |

Methylomonas sporium strain NCIMB 11126 | 98.96 |

| Pashan Lake | water sample | 08.07.2023 | 10-2 | PLW2 | - | Methylosinus trichosporium strain OB3b | 99.93 |

| Pashan Lake | water sample | 08.07.2023 | 10-4 | PLW4 | - | Methylolobus aquaticus strain FWC3 | 99.43 |

|

Mumbai Mangroves |

soil sample | 21-09-2023 | 10-2 | MgM2 | PV630802 | Methylomonas aurea strain SURF-1 | 96.70 |

| Vetal hill Pond | Water Sample |

15-01-2024 | 10-8 | AW2B | - | Methylosinus trichosporium strain OB3b | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).