Submitted:

27 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. A Far-Right Culture War on Climate Politics

1.1. From Climate Policy Role Model to International Scapegoat

1.2. Nasty Rhetoric as a Strategy in Swedish Climate Politics

1.3. Understanding Nasty Rhetoric in Climate Politics

1.4. Religion as a Basis of the Far-Right’s Culture War

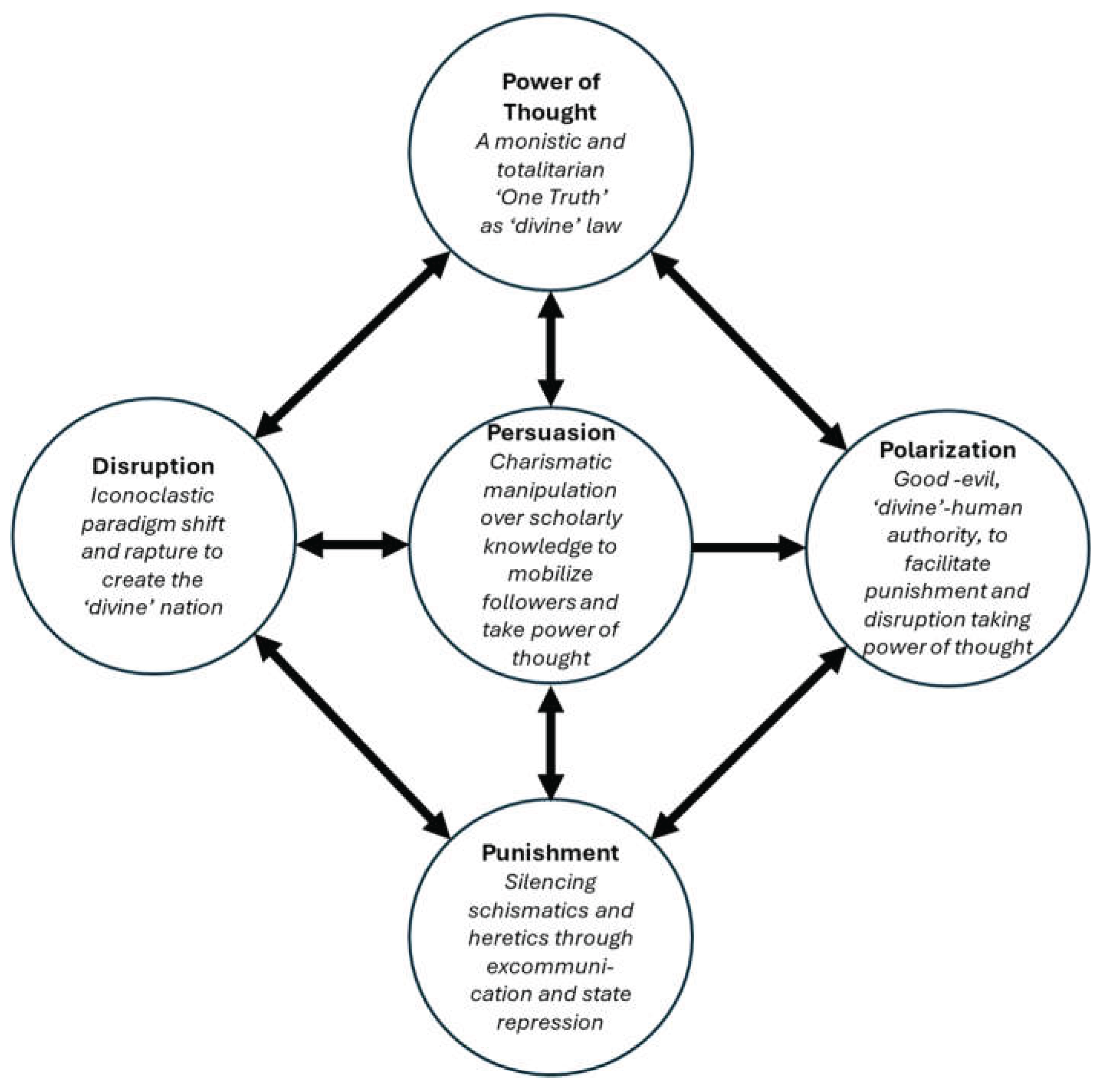

- Power of Thought

- Polarisation

- Persuasion

- Punishment

- Disruption

2. Populist Politics with Hate, Threats and Violence

2.1. Nasty Politics

2.2. Nasty Rhetoric

2.3. Emotional Governance

2.4. Insults Feed Violence

3. Far-Right Populism and the Legacy of Christianity

3.1. Power of Thought

3.1.1. The Far-Right’s Conception of Public Interest

I work to upgrade western civilisation and identity. I think that is very important and will become even more important. It is about the legacy of Rome, Athens, Jerusalem, the Enlightenment. It will need to be strengthened in the future.

3.1.2. Christianity and Public Interest

There is none like you, O Lord, and there is no God besides you, according to all that we have heard with our ears.

We demolish arguments and every pretention that sets itself up against the knowledge of God, and we take captive every thought to make it obedient to Christ.

should not submit to the ‘form’ of them but that we [the people] should be transformed, that we should receive a new form by the renewing of the mind, that is, by starting from a new point, namely, the will of God and love.

3.1.3. Analysing the Legacy

3.2. Polarisation

3.2.1. Far-Right Polarisation in Climate Politics

3.2.2. Christian Dualism

The God who made the world and everything in it, being Lord of heaven and earth, does not live in temples made by man, nor is he served by human hands, as though he needed anything, since he himself gives to all mankind life and breath and everything.

3.2.1.1. Divine vs. Human Authority

I will give you all these things, if you will prostrate yourself and worship me (Matthew 4:8–9).

I will give you all this power and the glory of these kingdoms, for it has been given to me, and I give it to whom I will. If you, then, will prostrate yourself before me, it shall all be yours (Luke 4:6–7).

The state is a means by which to concentrate wealth and it enriches its clients. We see the same thing today in the form of public works and arms production. Political power makes alliance with the power of money. When Babylon collapses, all the kings of the earth lament and despair and the capitalists weep.

3.2.1.2. Divine vs. Scholarly Knowledge

The scribes and Pharisees have taken their seat on the chair of Moses. […] For they preach but they do not practice. They tie up heavy burdens and lay them on people’s shoulders, but they will not lift a finger to move them.

Woe to you scribes and Pharisees, you hypocrites. You lock the kingdom of heaven before human beings. You do not enter yourselves, nor do you allow entrance to those trying to enter. […] You cleanse the outside of cup and dish, but inside they are full of plunder and self-indulgence. […] You are like whitewashed tombs, which appear beautiful on the outside, but inside are full of dead men’s bones and every kind of filth.

And my speech and my preaching was not with enticing words of man’s wisdom, but in demonstration of the Spirit and of power: that your faith should not stand in the wisdom of men, but in the power of God.

3.2.3. Analysing the Legacy

3.3. Persuasion

3.3.1. Fiction and Manipulation in Far-Right Populism

3.3.2. Charisma in Christianity

And my speech and my preaching was not with enticing words of man’s wisdom, but in demonstration of the Spirit and of power: that your faith should not stand in the wisdom of men, but in the power of God.

Figuring eloquence as a charisma allows Paul to leverage two elements of first-century Corinthian culture, sophistry and patronage, against each other. To say that speech and knowledge are kinds of spiritual charismata is to argue that the value of their exercise consists in an advertisement of the divine patronage that they evidence. This refiguration, consequently, changes the quality, shape, and meaning of virtuoso speech, but it does not abolish it. Paul simply promotes an enigmatic set of rhetorical performances—the charismata—over theatrical displays of sophistic reasoning.

3.3.3. From Corinthians to Max Weber and Magick

devotion to the extraordinary and unheard-of, to what is strange to all rule and tradition and which therefore is viewed as divine. It is devotion born of distress and enthusiasm. Genuine charismatic domination therefore knows of no abstract legal codes and statutes and of no ‘formal’ way of adjudication. Its ‘objective’ law emanates concretely from the highly personal experience of heavenly grace and from the god-like strength of the hero. […] Hence, its attitude is revolutionary and transvalues everything; it makes a sovereign break with all traditional or rational norms: ‘It is written, but I say unto you’.

Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law

Love is the law, love under will

3.3.4. From Max Weber to Christian mission

3.3.5. Analysing the Legacy

To you in the Elite...we are not ashamed. It is not us who have destroyed Sweden... It is you who are to blame for it.

3.4. Punishment

3.4.1. Far-Right Punishment of Enemies

3.4.2. Sin, Redemption and Vengeance

I do not understand what I do. For what I want to do I do not do, but what I hate I do. And if I do what I do not want to do, I agree that the law is good. As it is, it is no longer I myself who do it, but it is sin living in me. I know that nothing good lives in me, that is, in my sinful nature. For I have the desire to do what is good, but I cannot carry it out. For what I do is not the good I want to do; no, the evil I do not want to do—this I keep on doing. Now if I do what I do not want to do, it is no longer I who do it, but it is sin living in me that does it.

What a miserable person I am! Who will rescue me from my dying body? I thank God that our Lord Jesus Christ rescues me! So I am obedient to God’s standards with my mind, but I am obedient to sin’s standards with my corrupt nature.

Whoever takes a human life shall surely be put to death. Whoever takes an animal’s life shall make it good, life for life. If anyone injures his neighbour, as he has done it shall be done to him, fracture for fracture, eye for eye, tooth for tooth; whatever injury he has given a person shall be given to him. Whoever kills an animal shall make it good, and whoever kills a person shall be put to death. [...]

Do not judge, and you will not be judged. Do not condemn, and you will not be condemned. Forgive, and you will be forgiven. Give, and it will be given to you. A good measure, pressed down, shaken together and running over, will be poured into your lap. For with the measure you use, it will be measured to you.

He made Him who knew no sin to be sin on our behalf, so that we might become the righteousness of God in Him.

3.4.3. Love and Hate

3.4.4. Schism, Heresy and Excommunication

3.4.5. Analysing the Legacy

3.5. Disruption

3.5.1. The Far-Right Populist Paradigm Shift

3.5.2. The Judgement Day

3.5.3. Analysing the Legacy

In a time of ceaseless peril, openly supremacist movements in these countries are positioning their relatively wealthy states as armed bunkers. These bunkers are brutal in their determination to expel and imprison unwanted humans (even if that requires indefinite confinement in extra-national penal colonies).

4. Concluding Remarks

| 1 | Articles in French newspaper Le Monde, 27 January 2024, https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2024/01/27/sweden-is-moving-backward-on-climate-policy_6470373_4.html, and pan-European newspaper Euractive, 30 March 2023, https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/news/swedish-right-wing-government-puts-country-on-wrong-climate-path/

|

| 2 | Article in independent conservative newspaper Svenska Dagbladet, 21 December 2023, https://www.svd.se/a/3EneLP/torehammar-svek-och-djavulspakter-i-klimatpolitiken l |

| 3 | In a recent editorial, Editor-in-Chief of Science, Dr. Holden Thorp (2025, p. 339) considers that scientists should not talk about scientific consensus, but that scientists should look for convergent evidence. Convergent evidence “honours science’s norms of critique and correction by scientists being invited to discussions of the extent of existing knowledge and multiple ways in which is it was developed rather than on what a lay audience is likely to hear as a ‘case closed’ appeal to authority”. |

| 4 | Interview in Swedish Television, 10 December 2021.Quote at 1:04:03. https://bit.ly/36rVAyf

|

| 5 | See article in Independent, 12 May 2025. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/us-politics/trump-credit-conclave-pope-leo-xiv-election-b2749213.html

|

| 6 | See article in National Catholic Reporter, 1 February 2025. https://www.ncronline.org/opinion/guest-voices/jd-vance-wrong-jesus-doesnt-ask-us-rank-our-love-others

|

| 7 | |

| 8 |

References

- Aalberg, T.; De Vreese, C. Introduction: Comprehending populist political communication. In Populist Political Communication in Europe; Aalberg, T., Esser, F., Reinemann, C., De Vreese, C.,Stromback, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, 2016; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, A. Hating an outgroup is to render their stories a fiction: A BLINCS model hypothesis and commentary. Imagination, Cognition and Personality 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuín-Vences, N., Cuesta-Cambra, U., Niño-González, J.I.; Bengochea-González, C. Hate speech analysis as a function of ideology: Emotional and cognitive effects. Comunicar: Media Education Research Journal 2022, 30, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agius, C., Bergman Rosamond, A.; Kinnvall, C. Populism, ontological insecurity and gendered nationalism: Masculinity, climate denial and Covid-19. Politics, Religion & Ideology 2021, 21, 432–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allwood, M., Ghafoori, B., Salgado, C., Slobodin, O., Kreither, J., Waelde, L.C., Larrondo, P.; Ramos, N. Identity-based hate and violence as trauma: Current research, clinical implications, and advocacy in a globally connected world. Journal of Traumatic Stress 2022, 35, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkiviadou, N. The legal regulation of hate speech: The international and European frameworks, Politička Misao: Croatian Political Science Review. 2018, 55, 203–229. https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?

- Andersson, M. (2021) The climate of climate change: Impoliteness as a hallmark of homophily in YouTube comment threads on Greta Thunberg’s environmental activism, Journal of Pragmatics, 178, 93-107. [CrossRef]

- Arce-García, S. , Díaz-Campo, J. & Cambroneo-Saiz, B. (2023) Online hate speech and emotions on Twitter: a case study of Greta Thunberg at the UN Climate Change Conference COP25 in 2019, Social Network Analysis and Mining, 13, 48. [CrossRef]

- Arendt, H. Thinking and moral considerations: A lecture. Social Research 1971, 38, 417–446. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40970069.

- Askanius, T., Brock, M., Kaun, A.; Larsson, A.O. Time to abandon Swedish women’: Discursive connections between misogyny and white supremacy in Sweden. International Journal of Communication 2024, 18, 5046–5064. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/16808/4840.

- Asprem, E. Arguing with Angels: Enochian Magic and Modern Occulture; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Assimakoupoulos, S., Baider, F. H.; Millar, S. Online Hate Speech in the European Union; Springer: Heidelberg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Atak, K. (2022) Racist victimization, legal estrangement and resentful reliance on the police in Sweden, Social & Legal Studies, 31(2), 238-260. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, I. , Gouldson, A. & Newell, P. (2011) Ecological modernisation and the governance of carbon: A critical analysis, Antipode, 43, 682-703. [CrossRef]

- Barker, J. The one and the many: Church-centered innovations in a Papua New Guinean community. Current Anthropology 2014, 55, S172–S181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, A.R. , Eroukhmanoff, C. & Head, N. (2019) Introduction: Interrogating the ‘everyday’ politics of emotions in international relations, Journal of International Political Theory, 15(2), 136-147. [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, H.A.; Nathansson, C. Kulturpolitikens liv efter döden; Bokförlaget Atlas: Stockholm, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson Meuller, E. & Evans, E. (2024) Comparing policy responses to incels in Sweden and the UK, Policy & Politics, early view. [CrossRef]

- Berecz, T.; Devinat, C. Relevance of cyberhate in Europe and current topics that shape online hate speech, International Network Against Cyber Hate (INACH). 2017. https://www.inach.net/wp-content/uploads/FV-Relevance_of_Cyber_Hate_in_Europe_and_Current_Topics_that_Shape_Online_Hate_Speech.pdf.

- Berglund, O. & Schmidt, D. (2020) Extinction Rebellion and Climate Change Activism: Breaking the Law to Change the World, London: Palgrave Macmillan. [CrossRef]

- Beuter, C. & Kortmann, M. (2023) Similar yet not the same: Right-wing populist parties’ stances on religion in Germany and the Netherlands, Politics and Religion, 16(2), 374-392. [CrossRef]

- Bialecki, J. (2014) After the denominozoic: Evolution, differentiation, denominationalism, Current Anthropology, 55(S10), S193-S204. [CrossRef]

- Bitonti, A. The role of lobbying in modern democracy: A theoretical framework. In Lobbying in Europe: Public Affairs and the Lobbying Industry in 28 EU Countries; Bitonti, A., Harris, P., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, 2017; pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bitonti, A. (2020) Where it all starts: Lobbying, democracy and the public interest, Journal of Public Affairs, 20, e2001. [CrossRef]

- Bjereld, U. SD:s hat påverkar public service framtid. Magasinet Konkret. 14 May 2024. https://magasinetkonkret.se/sds-hat-paverkar-public-service-framtid/.

- Björkenfeldt, O. & Gustafsson, L. (2023) Impoliteness and morality as instruments of destructive informal social control in online harassment targeting Swedish journalists, Language & Communication, 93, 172-187. [CrossRef]

- Bleiker, R. Visual Global Politics. Routledge: Oxford, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Boasson, E.L. & Huitema, D. (2017) Climate governance entrepreneurship: Emerging findings and a new research agenda, Environment & Planning C: Politics and Space, 35, 1343-1361. [CrossRef]

- Boese, V.A. , Lundstedt, M., Morrison, K., Sato, Y. & Lindberg, S.I. (2022) State of the world 2021: Autocratization changing its nature? Democratization, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, H. Aleister Crowley: A prophet for a modern age. In The Occult World; Partridge, C., Ed.; Routledge: New York, 2015; pp. 293–302. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan, H.; Starr, M.P. Aleister Crowley and Western Esotericism; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Brosch, T. (2021) Affect and emotions as drivers of climate change perception and action: a review, Current Opinion in Behavioral Science, 42, 15-21. [CrossRef]

- Bsumek, P.K. , Schwarze, S., Peeples, J. & Schneider, J. (2019) Strategic gestures in Bill McKibben’s climate change rhetoric, Frontiers in Communication, 4, 40. [CrossRef]

- Burck, J., Uhlich, T., Bals, C., Höhne, N., Nascimento, L., Wong, J., Beaucamp, L., Weinreich, L.; Ruf, L. Climate Change Performance Index 2025, Bonn: Germanwatch, NewClimate Institute & Climate Action Network. 2024. https://c, cpi.org/download/climate-change-performance-index-2025/.

- Buzogány, A.; Mohamad-Klotzbach, C. Environmental populism. In The Palgrave Handbook of Populism; Oswald, M., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, CH, 2022; pp. 321–340. [Google Scholar]

- Calvert, C. (1997) Hate speech and its harms: A communication theory perspective, Journal of Communication, 47(1), 4-19. [CrossRef]

- Caramani, D. (2017) Will vs. reason: The populist and technocratic forms of political representation and their critique to party government, American Political Science Review, 111(01), 54-67. [CrossRef]

- Cassegård, C.; Thörn, H. Climate justice, equity and movement mobilization. In Climate Action in a Globalizing World; Cassegård, C., Soneryd, L., Thörn, H., Wettergren, Å, Eds.; Routledge: London, 2017; pp. 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cassese, E.C. (2021) Partisan dehumanization in American politics, Political Behavior, 43, 29-50. [CrossRef]

- Castaño-Pulgarín, S.A. , Suárez-Betancur, N., Tilano Vega, L.M. & Herrera López, H.M. (2021) Internet, social media and online hate speech. Systematic review, Aggression and Violent Behavior, 58, 101608. [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.L. (2019) The impact of emotion: A blended model to estimate influence on social media, Information Systems Frontiers, 21, 1137-1151. [CrossRef]

- Chetty, N. & Alathur, S. (2018) Hate speech review in the context of online social networks, Aggression and Violent Behavior, 40, 108-118. [CrossRef]

- Chua, L. The Christianity of Culture: Conversion, Ethnic Citizenship, and the Matter of Religion in Malaysian Borneo; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Churton, T. Aleister Crowley: The Beast in Berlin; Inner Traditions: Rochester, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Churton, T. Aleister Crowley in America; Inner Traditions: Rochester, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Almagor, R. (2018) Taking North American white supremacist groups seriously: The scope and challenge of hate speech on the internet, International Journal for Crime, Justice, and Social Democracy, 7(2), 38-57. [CrossRef]

- Cowan, G. & Hodge, C. (1996) Judgments of hate speech: The effects of target group, publicness, and behavioral responses of the target, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 26(4), 355-374. [CrossRef]

- Crawford, N.C. (2014) Institutionalizing passion in world politics: Fear and empathy, International Theory, 6(3), 535-557. [CrossRef]

- Crowley, A. [1909] The Book of the Law: Liber Al Vel Legis; Red Wheel/Weiser: San Francisco, CA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley, A. [1912] Magick: Liber ABA; Red Wheel/Weiser: San Francisco, CA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley, K. & Head, B.W. (2017) The enduring challenge of ‘wicked problems’: revisiting Rittel and Webber, Policy Sciences 50, 53-547. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, K., Hix, S., Dennison, S.; Laermont, I. A Sharp Right Turn: A Forecast for the 2024 European Parliament Elections; European Council on Foreign Relations: Berlin, 2024; https://ecfr.eu/publication/a-sharp-right-turn-a-forecast-for-the-2024-european-parliament-elections/.

- Dahl, R.A. On Democracy, New Haven; Yale University Press: CT, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, R.J., Recchia, S.; Rohrschneider, R. The environmental movement and the modes of political action. Comparative Political Studies 2003, 36, 743–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daswani, G. (2013) On Christianity and ethics: Rupture as ethical practice in Ghanaian Pentecostalism, American Ethnologist, 40(3), 467-479. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, S. (2012) The insuperable imperative: A critique of the ecologically modernizing state¸ Capitalism Nature Socialism, 23(2), 31-50. [CrossRef]

- De Felipe, P.; Jeeves, M.A. Science and Christianity conflicts: Real and contrived. Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith 2017, 69, 131–147. [Google Scholar]

- de Moor, J. , De Vydt, M., Uba, K. & Wahlström, M. (2020) New kids on the block: Taking stock of the recent cycle of climate activism, Social Movement Studies, 20, 619-625. [CrossRef]

- Dellagiacoma, L. , Geschke, D. & Rothmund, T. (2024) Ideological attitudes predicting online hate speech: the differential effects of right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation, Frontiers in Social Psychology, 2, early view. [CrossRef]

- Dryzek, J.S. (2014) The deliberative democrat’s idea of justice, European Journal of Political Theory, 12, 329-346. [CrossRef]

- Eco, U. Ur-Fascism: Freedom and liberation are an unending task. The New York Review. 22 June 1995. https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1995/06/22/ur-fascism/.

- Eddebo, J. Babylon will be found no more: On affinities between Christianity and Anarcho-Primitivism. Journal of Religion & Society 2017, 19, 1–17. http://moses.creighton.edu/JRS/toc/2017.html.

- Ehrman, B. Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ekberg, K. & Pressfeldt, V. (2022) A road to denial: Climate change and neoliberal thought in Sweden, 1988–2000, Contemporary European History, 31(4), 627-644. [CrossRef]

- Ellul, J. Anarchy and Christianity; Grand Rapic, MI: Eerdmans, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Eubanks, P. The Troubled Rhetoric and Communication of Climate Change: The Argumentative Situation; London: Routledge, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Euler, J. (2018) The commons: A social form that allows for degrowth and sustainability, Capitalism Nature Socialism, 30(2), 158-175. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. A more inclusive and protective Europe: extending the list of EU crimes to hate speech and hate crime, Brussels. 2021. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:4d768741-58d3-11ec-91ac-01aa75ed71a1.0002.02/DOC_1&format=PDF.

- Evans, G. & Phelan, L. (2016) Transition to a post-carbon society: Linking environmental justice and just transition discourses, Energy Policy, 99, 329-339. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A. , Joosse, S., Strandell, J., Söderberg, N., Johansson, K. & Boonstra, W.J. (2024) How justice shapes transition governance—a discourse analysis of Swedish policy debates, Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 67(9), 1998-2016. [CrossRef]

- Forst, M. State repression of environmental protest and civil disobedience: a major threat to human rights and democracy, Position Paper by UN Special Rapporteur on Environmental Defenders under the Aarhus Convention, February 2024, Geneva: United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. 2024. https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2024-02/UNSR_EnvDefenders_Aarhus_Position_Paper_Civil_Disobedience_EN.pdf.

- Freedman, D. (2018) Populism and media policy failure, European Journal of Communication, 33(6), 604-618. [CrossRef]

- Frijda, N.H. The Emotions; Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Frijda, N.H. & Mesquita, B. (1994) The social roles and functions of emotions, In: Kitayama, S. & Markus, H.R. (eds.), Emotion and Culture: Empirical studies of mutual influence, NN: American Psychological Association; 51-87. [CrossRef]

- Garland, J. Iconoclash and the climate movement. Visual Studies 2023, 39, 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerle, E. Farlig förenkling – Religion och politik utifrån Sverigedemokraterna och Humanisterna; Nora: Nya Doxa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Glad, K.A. , Dyb, G., Hellevik, P., Michelsen, H. & Øien Stensland, S. (2023) “I wish you had died on Utøya”: Terrorist attack survivors’ personal experiences with hate speech and threats, Terrorism and Political Violence, 36(6), 834-850. [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J.; Morton, T. Climate crisis and the limits of liberal democracy? Germany, Australia and India compared. Democarcy & Crisis, Isakhan, B., Slaughter, S., Eds.; London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014; pp. 229–252. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia, J.J.E.; Noone, T.B. A Companion to Philosophy in the Middle Ages; London: Wiley, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Grosshans, H.P. Reason and philosophy in Martin Luther’s thought. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. 2017. https://oxfordre.com/religion/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.001.0001/acrefore-9780199340378-e-343.

- Grundmann, R. (2016) Climate change as a wicked social problem, Nature Geoscience, 9, 562-563. [CrossRef]

- Guiliani, M. (2015) Patterns of democracy reconsidered: The ambiguous relationship between corporatism and consensualism, European Journal of Political Research, 55, 22-42. [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, P. Angreppet—så urholkar Tidöregeringen vår demokrati. Lund, SE: Arkiv förlag, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann, A.,; Thompson, D. Democracy and Disagreement; Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, T. , Syrovatka, F. & Jürgens, I. (2022) The European Green Deal and the limits of ecological modernisation, Culture, Practice & Europeanization, 7, 247.261. [CrossRef]

- Habermas, J. Between Facts and Norms. Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hagerlid, M. (2021) Swedish women’s experiences of misogynistic hate crimes: The impact of victimization on fear of crime, Feminist Criminology, 16(4), 504-525. [CrossRef]

- Haley, P. (1980) Rudolph Sohm on Charisma, The Journal of Religion, 60(2), 185-197. [CrossRef]

- Handman, C. (2014) Becoming the body of Christ: Sacrificing the speaking subject in the making of the colonial Lutheran church in New Guinea, Current Anthropology, 55(S10), S205-S215. [CrossRef]

- Hann, C. 2014. The heart of the matter: Christianity, materiality, and modernity, Current Anthropology, 55(S10), S182-S192. [CrossRef]

- Hedenborg White, M. Rethinking Aleister Crowley and Thelema: New perspectives. Aries: Journal for the Study of Western Esotericism 2021, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkurinen, P. (2021) The nature of degrowth: Theorising the core of nature for the degrowth movement, Environmental Values, 30(3), 367-385. [CrossRef]

- Held, D. Models of Democracy; Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hellström, A. (2023) The populist divide in far-right political discourse in Sweden: Anti-immigration claims in the Swedish socially conservative online newspaper Samtiden from 2016 to 2022, Societies, 13(5), 108. [CrossRef]

- Hellström, A. & Nilsson, T. (2010) ‘We Are the Good Guys’: Ideological positioning of the nationalist party Sverigedemokraterna in contemporary Swedish politics, Ethnicities, 10(1), 55-76. [CrossRef]

- Hietanen, M. & Eddebo, J. (2022) Towards a definition of hate speech: — With a focus on online contexts, Journal of Communication Inquiry, 47(4), 440-458. [CrossRef]

- Hornsey, M.J. (2021) The role of worldviews in shaping how people appraise climate change, Current Opinion in Behavioral Science, 42, 36-41. [CrossRef]

- Howe, P.D. (2021) Extreme weather experience and climate change opinion, Current Opinion in Behavioral Science, 42, 127-131. [CrossRef]

- Hultman, M., Björk, A.; Viinikka, T. The far right and climate change denial. In The Far Right and the Environment: Politics, Discourse and Communication; Forchtner, B., Ed.; London: Routledge, 2019; pp. 121–136. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, C. (2014) Schism, event, and revolution: the Old Believers of Trans-Baikalia, Current Anthropology, 55(S10), S216-S225. [CrossRef]

- Ilse, P.B. & Hagerlid, M. (2025) ‘My trust in strangers has disappeared completely’: How hate crime, perceived risk, and the concealment of sexual orientation affect fear of crime among Swedish LGBTQ students, International Review of Victimology, 31(1), 39-58. [CrossRef]

- Incropera, F.P. Climate Change: A Wicked Problem. Complexity and uncertainty at the intersection of science, economics, politics, and human behavior. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC (2023) Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report, Geneva: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. [CrossRef]

- Izard, C.E. (2010) More meanings and more questions for the term “emotion”, Emotion Review, 2(4), 383-385. [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, K.H. & Taussig, D. (2017) Disruption, demonization, deliverance, and norm destruction: The rhetorical signature of Donald J. Trump, Political Science Quarterly, 132(4), 619-650. [CrossRef]

- Jänicke, M. Ecological modernization—A paradise of feasibility but no general solution. In The Ecological Modernization Capacity of Japan and Germany: Energy Policy and Climate Protection; Metz, L., Okamura, L., Weidner, H., Eds.; Wiesbaden: Springer Nature, 2020; pp. 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, M. Sverige enda land som inte sökt pengar från EU:s återhämtningsfond. Tidningen Syre. 22 July 2024. https://tidningensyre.se/2024/22-juli-2024/sverige-enda-land-som-inte-sokt-pengar-fran-eus-aterhamtningsfond/.

- Jylhä, K.M. , Strimling, P. & Rydgren, J. (2020) Climate change denial among radical right-wing supporters, Sustainability, 12(23), 10226. [CrossRef]

- Kaczynski, R. Perdurabo: The Life of Aleister Crowley, 2nd ed.; Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmoe, N. P. , Gubler, J. R. & Wood, D. A. (2017) Toward conflict or compromise? How violent metaphors polarize partisan issue attitudes, Political Communication, 35(3), 333-352. [CrossRef]

- Katsambekis, G. (2022) Constructing ‘the people’ of populism: A critique of the ideational approach from a discursive perspective, Journal of Political Ideologies, 27(1), 53-74. [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, T. Luther and Lutheranism. In The Oxford Handbook of the Protestant Reformations; Rublack, U., Ed.; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017; pp. 146–166. [Google Scholar]

- Keltner, K., Oatley, K.; Jenkins, J. M. Understanding Emotions, 3rd ed.; London: Wiley, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, M. Back to the populist future?: understanding nostalgia in contemporary ideological discourse. In Re-energizing Ideology Studies; Freeden, M., Ed.; London: Routledge, 2018; pp. 133–150. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, E. Why We’re Polarized; New York: Avid Reader Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, N. Doppleganger: A Trip into the Mirror World; Toronto: Penguin Random House, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, N.; Taylor, A. The rise of end time fascism. The Guardian. 13 April 2025. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2025/apr/13/end-times-fascism-far-right-trump-musk.

- Ketola, M.; Odmalm, P. The end of the world is always better in theory: The strained relationship between populist radical right parties and the state-of-crisis narrative. In Political Communication and Performative Leadership; Lacatus, C., Meibauer, G., Löfflmann, G., Eds.; 2023; pp. 163–177. [Google Scholar]

- Khmara, Y. & Kronenberg, J. (2020) Degrowth in the context of sustainability transitions: In search of a common ground, Journal of Cleaner Production, 267, 122072. [CrossRef]

- Kinnvall, C. & Svensson, T. (2022) Exploring the populist ‘mind’: Anxiety, fantasy, and everyday populism, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 24(3), 526-542. [CrossRef]

- Klemperer, V. The Language of the Third Reich: LTI, Lingua Tertii Imperii: A Philologist’s Notebook; London, Continuum, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Koschorke, A.; Golb, J. Fact and Fiction: Elements of a General Theory of Narrative; Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman, G. Aleister Crowley: Magick, Rock and Roll, and the Wickedest Man in the World; New York: Tarcher, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Laclau, E. On Populist Reason; London: Verso, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Laebens, M.G. & Lührmann, A. (2021) What halts democratic erosion? The changing role of accountability, Democratization, 28(5), 908-928. [CrossRef]

- Lagerkvist, S. Så snabbt kan vår demokrati avskaffas. Tidningen Syre. 23 March 2024. https://tidningensyre.se/2024/23-mars-2024/sa-snabbt-kan-var-demokrati-avskaffas/.

- Lago, I. & Coma, I. (2017) Challenge or consent? Understanding losers’ reactions in mass elections, Government & Opposition, 52(3), 412-436. [CrossRef]

- Lahn, B. (2021) Changing climate change: The carbon budget and the modifying-work of the IPCC, Social Studies of Science, 51(1), 3-27. [CrossRef]

- Lamour, C. (2022) Orbán Urbi et Orbi: Christianity as a nodal point of radical-right populism, Politics and Religion, 15, 317-343. [CrossRef]

- Lang, P.J. , Davis, M., & Öhman, A. (2000) Fear and anxiety: Animal models and human cognitive psychophysiology, Journal of Affective Disorders, 61(3), 137-159. [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Emotion and Adaptation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, L.J. Super wicked problems and climate change: Restraining the present to liberate the future. Cornell Law Review 2008, 94, 1153. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/clqv94&div=38&id=&page=.

- Lehmann, D. (2013) Religion as heritage, religion as belief: Shifting frontiers of secularism in Europe, the USA and Brazil, International Sociology, 28(6), 645-662. [CrossRef]

- Levin, K. , Cashore, B., Bernstein, S. & Auld, G. (2012) Overcoming the tragedy of super wicked problems: constraining our future selves to ameliorate global climate change, Policy Sciences, 45, 123-152 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Levitsky, S.; Ziblatt, D. How Democracies Die; New York City: Crown, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowsky, S. (2021) Liberty and the pursuit of science denial, Current Opinion in Behavioral Science, 42, 65-69. [CrossRef]

- Lijphart, A. Democracy in Plural Societies: A Comparative Exploration; New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg, D.C. The fate of science in Patristic and Medieval Christendom. In The Cambridge Companion to Science and Religion; Harrison, P., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Lindvall, D. & Karlsson, M. (2023) Exploring the democracy–climate nexus: A review of correlations between democracy and climate policy performance, Climate Policy, 24, 87-103. [CrossRef]

- Lönegård, C. SD:s stora plan: ta makten över kulturen. Svenska Dagbladet. 4 July 2020. https://www.svd.se/a/Jo5j87/karlssons-plan-en-motkraft-till-kulturvanstern?utm_source=iosapp&utm_medium=share.

- Lowrie, W.; Sohm, R. The Church and Its Organization in Primitive and Catholic Times: An Interpretation of Rudolph Sohm’s Kirchenrecht; New York: Longmans, Green and Co, 1904. [Google Scholar]

- Lührmann, A. (2021) Disrupting the autocratization sequence: Towards democratic resilience, Democratization, 28, 1017-1039. [CrossRef]

- Lührmann, A., Gastaldi, L., Hirndorf, D.; Lindberg, S.I. Defending Democracy Against Illiberal Challengers: A Resource Guide, Gothenburg: V-Democracy Institute/University of Gothenburg. 2020. https://www.v-dem.net/documents/21/resource_guide.pdf.

- Lundquist, L.J. Slutet på yttrandefriheten (och demokratin?); Stockholm: Carlsson Bokförlag, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, P. (2019) Variation in policy success: radical right populism and migration policy, West European Politics, 42(3), 517-544. [CrossRef]

- Mair, P. Ruling the Void: The Hollowing of Western Democracy; London: Verso, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt, J. , Oliveira, C. & Lederer, M. (2022) Same, same but different? How democratically elected right-wing populists shape climate change policymaking, Environmental Politics, 31(5), 777-800. [CrossRef]

- Martínez, C.A. , van Prooijen, J.-W. & Van Lange, P.A.M. (2022a) Hate: Toward understanding its distinctive features across interpersonal and intergroup targets, Emotion, 22(1), 46.63. [CrossRef]

- Martínez, C.A. , van Prooijen, J.-W. & Van Lange, P.A.M. (2022b) A threat-based hate model: How symbolic and realistic threats underlie hate and aggression, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 103, 104393. [CrossRef]

- Masson, T. & Fritsche, I. (2021) We need climate change mitigation and climate change mitigation needs the ‘We’: a state-of-the-art review of social identity effects motivating climate change action, Current Opinion in Behavioral Science, 42, 89-96. [CrossRef]

- Matti, S. , Petersson, C. & Söderberg, C. (2021) The Swedish climate policy framework as a means for climate policy integration: an assessment, Climate Policy, 21(9), 1146-1158. [CrossRef]

- McBath, J.H. & Fisher, WR. Persuasion in presidential campaign communication. Quarterly Journal of Speech 1969, 55(1), 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, A. Science and Religion: A New Introduction, 2nd ed.; Malden, MA: Wiley–Blackwell, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Meléndez, C. & Rovira Kaltwasser, CC. Negative partisanship towards the populist radical right and democratic resilience in Europe. Democratization, 2021, 28(5), 949–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, T.M. (2020) No-go zones in Sweden: The infectious communicability of evil, Language, Culture and Society, 2(1), 7-36. [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.L. , & Vaccari, C. (2020). Digital threats to democracy: Comparative lessons and possible remedies, The International Journal of Press/Politics, 25(3), 333-356. [CrossRef]

- Minkenberg, M. Religion and the radical right. In The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right; Rydgren, J., Ed.; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018; pp. 366–393. [Google Scholar]

- Minor, A. Iconoclasm. In Iconoclasm: Art as a Battleground; Minor, A., Manley, A., Eds.; Copenhagen: Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, 2024; pp. 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Modéus, F. SD:s politik följer inte en kristen idétradition. Expressen. 27 October 2022. https://www.expressen.se/debatt/sds-politik-foljer-inte-en-kristen-idetradition--/.

- Moffitt, B. The Global Rise of Populism: Performance, Political Style, and Representation; Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt, B. (2017) Liberal illiberalism? The reshaping of the contemporary populist radical right in Northern Europe, Politics and Governance, 5(4), 112-122. [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, B. & Tormey, S. (2013) Rethinking populism: Politics, mediatisation and political style, Political Studies, 62(2), 381-397. [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, K.A. & Winter, R. Explaining the religion gap in support for radical right parties in Europe. Politics and Religion 2015, 8(2), 379–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouffe, C. The ‘End of Politics’ and the challenge of right-wing populism. In Populism and the Mirror of Democracy; Panizza, F., Ed.; London: Verso, 2005; pp. 50–71. [Google Scholar]

- Mouffe, C. Agonistics: Thinking the World Politically; London: Verso, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mudde, C. (2004) The populist Zeitgeist, Government and Opposition, 39(4), 541-563. [CrossRef]

- Mudde, C. Introduction to the populist radical right. In The Populist Radical Right. A Reader; Mudde, C., Ed.; London: Routledge, 2017; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mudde, C. The Far Right Today; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mudde, C. (2021) Populism in Europe: An illiberal democratic response to undemocratic liberalism, Government and Opposition, 56(4), 577-597. [CrossRef]

- Mudde, C.; Rovira Kaltwasser C. Populism. In The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies; Freeden, M., Sargent, L.T., Stears, M., Eds.; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013; pp. 493–512. [Google Scholar]

- Mutz, D.C. & Reeves, B. (2005) The new videomalaise: Effects of televised incivility on political trust, American Political Science Review, 99(1), 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Newell, P. (2008) Civil society, corporate accountability and the politics of climate change, Global Environmental Politics, 8, 122-153. [CrossRef]

- Niebuhr, H.R. The Social Sources of Denominationalism; New York: Meridian, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Nordensvärd, J. & Ketola, M. (2022) Populism as an act of storytelling: analyzing the climate change narratives of Donald Trump and Greta Thunberg as populist truth-tellers, Environmental Politics, 31(5), 861-882. [CrossRef]

- Oates, S.; Gibson, R.K. The Internet, civil society and democracy: A comparative perspective. In The Internet and Politics: Citizens, Voters and Activists; Oates, S., Owen, D., Gibson, R.K., Eds.; Abingdon: Routledge, 2006; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- OECD (2025) OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Sweden 2025, Paris: OECD Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Olivas Osuna, J.J. (2021) From chasing populists to deconstructing populism: A new multidimensional approach to understanding and comparing populism, European Journal of Political Research, 60(4), 829-853. [CrossRef]

- Olson, G. (2020) Love and hate online: Affective politics in the era of Trump, In: Violence and Trolling on Social Media: History, Affect, and Effects of Online Vitriol, Polak, S. & Trottier, D. (eds.), Amsterdam, NL: Amsterdam University Press; 153-178. [CrossRef]

- Opotow, S. & McClelland, S.I. (2007) The intensification of hating: A theory, Social Justice Research, 20(1), 68-97. [CrossRef]

- Pagels, E. The Gnostic Gospels; New York: Randon House, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, S. (2024) A comparative rhetorical analysis of Trump and Biden’s climate change speeches: Framing strategies in politics, Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 55(2), 138-162. [CrossRef]

- Pasi, M. Aleister Crowley and the Temptation of Politics; Abingdon: Routledge, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pawelec, M. (2022) Deepfakes and democracy (theory): How synthetic audio-visual media for disinformation and hate speech threaten core democratic functions, Digital Society, 1, 19. [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.A. (2020) Limiting the capacity for hate: Hate speech, hate groups and the philosophy of hate, Educational Philosophy and Theory, 54(14), 2325-2330. [CrossRef]

- Pétrement, S. A Separate God: The Origins and Teachings of Gnosticism; San Francisco, CA: Harper, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson, T. (2009) Religion och samhällspraktik: en jämförande analys av det sekulariserade Sverige, Socialvetenskaplig tidskrift, 16(3/4), 233-264. [CrossRef]

- Piazza, J. A. (2020a) Politician hate speech and domestic terrorism, International Interactions, 46(3), 431-453. [CrossRef]

- Piazza, J.A. When politicians use hate speech political violence increases. The Conversation. 28 September 2020b. https://theconversation.com/when-politicians-use-hate-speech-political-violence-increases-146640.

- Pickering, J. , Bäckstrand, K. & Schlosberg, D. (2020) Between environmental and ecological democracy: Theory and practice at the democracy-environment nexus, Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 22(1), 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Poletti Lundström, T. Trons försvarare: Idéer om religion i svensk radikalnationalism 1988–2020; Uppsala: Uppsala University Press, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Polletta, F. , Chen, P.C.B., Gardner, B.G. & Motes, A. The sociology of storytelling. Annual Review of Sociology 2011, 37(1), 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popper, K.R. The Open Society and Its Enemies; London: Routledge, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Prusac-Lindhagen, M. Excluded from history: The ultimate humiliation in Roman times. In Iconoclasm: Art as a Battleground; Minor, A., Manley, A., Eds.; Copenhagen: Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, 2024; pp. 49–76. [Google Scholar]

- Rawls, J. Political Liberalism; New York: Columbia University Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Renström, E.A, Bäck, H.; Carroll, R. Threats, emotions, and affective polarization. Political Psychology 2023, 44, 1337–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittel, H.W.J. & Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences 1973, 4(2), 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, J. (2007) Continuity thinking and the problem of Christian culture: Belief, time, and the anthropology of Christianity, Current Anthropology, 48(1), 5-38. [CrossRef]

- Robbins, J. Is the trans- in transnational the trans- in transcendent? On alterity and the sacred in the age of globalization. In Transnational Transcendence: Essays on Religion and Globalization; Csordas, T.J., Ed.; Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009; pp. 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, J. (2014) The Anthropology of Christianity: Unity, diversity, new directions. An introduction to Supplement 10, Current Anthropology, 55(S10), S157-S171. [CrossRef]

- Roberts-Miller, P. (2019) Demagoguery, Charismatic Leadership, and the Force of Habit, Rhetoric Society Quarterly, 49(3), 233-247. [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.S.; Rivers, D.J. Donald Trump, legitimisation and a new political rhetoric. World Englishes 2020, 39, 623–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, B. (2023) The shadow of the Swedish right, Journal of Democracy, 34(1), 36-49. [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.A. The conflict metaphor and its social origins. Science and Christian Belief 1989, 1, 3–26. https://www.cis.org.uk/serve.php?filename=scb-1-1-russell.pdf.

- Rydgren, J. & van der Meiden, S. The radical right and the end of Swedish exceptionalism. European Political Science 2019, 18, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCPC. Klimatpolitiska rådets rapport 2024; Stockholm: Swedish Climate Policy Council, 2024; https://www.klimatpolitiskaradet.se/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/klimatpolitiskaradetsrapport2024.pdf.

- Schieffelin, B.B. (2014) Christianizing language and the displacement of culture in Bosavi, Papua New Guinea, Current Anthropology, 55(S10), S226-S237. [CrossRef]

- Schlosberg, D. Environmental Justice and the New Pluralism: The Challenge of Difference for Environmentalism; Cary, NC: Oxford University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, C.R., Zaval, L.; Markowitz, E.M. Positive emotions and climate change. Current Opinion in Behavioral Science 2021, 42, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz-Tomančok, A. & Woschnagg, F. Credibility at stake. A comparative analysis of different hate speech comments on journalistic credibility and support on climate protection measures. Cogent Social Sciences 2024, 10(1), 236709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweppe, J. & Perry, B. (2021) A continuum of hate: Delimiting the field of hate studies, Crime, Law and Social Change, 77, 503-528. [CrossRef]

- Scruton, R. England and the Need for Nations; London: Civitas, 2004; https://www.civitas.org.uk/pdf/EnglandAndTheNeedForNations.pdf.

- Séville, A. ‘There is no Alternative’: Politik zwischen Demokratie und Sachzwang; Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, T.M. (2024) Emotions in politics: A review of contemporary perspectives and trends, International Political Science Abstracts, 74(1), 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Sharman, A. & Howarth, C. (2017) Climate stories: Why do climate scientists and sceptical voices participate in the climate debate? Public Understanding of Science. [CrossRef]

- Silander, D. Problems in Paradise? Changes and Challenges to Swedish Democracy; Leeds, UK: Emerald, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Skovmøller, A.; Danbolt, M. The image of a toppled statue: Iconoclasm and collctive memory. In Iconoclasm: Art as a Battleground; Minor, A., Manley, A., Eds.; Copenhagen: Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, 2024; pp. 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.M. Stories of Peoplehood: The Politics and Morals of Political Membership; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Somer, M., McCoy, J.L.; Luke, R.E. Pernicious polarization, autocratization and opposition strategies. Democratization 2021, 28, 929–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soral, W., Bilewicz, M.,; Winiewski, M. Exposure to hate speech increases prejudice through desensitization. Aggressive Behavior 2018, 44, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaargaren, G. & Mol, A.P.J. (1992) Sociology, environment, and modernity: Ecological modernization as a theory of social change, Society & Natural Resources, 5(4), 323-344. [CrossRef]

- Sponholz, L. Hate Speech in den Massenmedien: Theoretische Grundlagen und empirische Umsetzung. Wiesbaden: Springer, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, W.G. & Stephan, C.W. (2017) Intergroup threats, In: Sibley, C.G. & Barlow, F.K. (eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of the Psychology of Prejudice, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 131-148. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, B. (2020) The rise of far-right civilizationism, Critical Sociology, 46(7-8), 1207-1220. [CrossRef]

- Strømmen, H.M. Sacred scripts of populism: Scripture-practices in the European far-right. In The Spirit of Populism: Political Theologies in Polarized Times; Schmiedel, U., Ralston, J., Eds.; Leiden, NL; Brill, 2021; pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Sutin, L. Do What Thou Wilt; New York: St Martin’s, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Svatoňová, E. , & Doerr, N. (2024) How anti-gender and gendered imagery translate the Great Replacement conspiracy theory in online far-right platforms, European Journal of Politics and Gender, 7(1), 83-101. [CrossRef]

- SWEPA. Naturvårdsverkets underlag till regeringens klimatredovisning 2024; Stockholm: Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, 2024; https://www.naturvardsverket.se/49732a/globalassets/amnen/klimat/klimatredovisning/naturvardsverkets-underlag-till-regeringens-klimatredovisning-2024.pdf.

- Swyngedouw, E. (2011) Depoliticized environments: The end of nature, climate change and the post-political condition, Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplements, 69, 253-274. [CrossRef]

- Taş, H. (2022) The chronopolitics of national populism, Identities, 29(2), 127-145. [CrossRef]

- Tenove, C. (2020) Protecting democracy from disinformation: Normative threats and policy responses, The International Journal of Press/Politics, 25(3), 517-537. [CrossRef]

- Thörn, H. & Svenberg, S. (2016) ‘We feel the responsibility that you shirk’: Movement institutionalization, the politics of responsibility and the case of the Swedish environmental movement, Social Movement Studies, 15, 593-609. [CrossRef]

- Thorp, H.H. (2025) Convergence and consensus, Science, 388(6745), 339. [CrossRef]

- Tidö parties. Tidöavtalet: En överenskommelse för Sverige; (Tidö Agreement: An agreement for Sweden), 14 October 2022, Tidö, SE: Moderaterna, Kristdemokraterna, Liberalerna, Sverigedemokraterna, 14 October 2022. https://www.liberalerna.se/wp-content/uploads/tidoavtalet-overenskommelse-for-sverige-slutlig.pdf.

- Törnberg, P. & Chueri, J. (2025) When do parties lie? Misinformation and radical-right populism across 26 countries, The International Journal of Press/Politics, early view. [CrossRef]

- V-Dem Institute. Democracy Winning and Losing at the Ballot: Democracy Report 2024; Gothenburg, SE: University of Gothenburg, 2024; https://v-dem.net/documents/43/v-dem_dr2024_lowres.pdf.

- Vahter, M. & Jakobson, M.L. (2023) The moral rhetoric of populist radical right: The case of the Sweden Democrats, Journal of Political Ideologies, preprint. [CrossRef]

- Valcore, J. , Asquith, N.L. & Rodgers, J. (2023) “We’re led by stupid people”: Exploring Trump’s use of denigrating and deprecating speech to promote hatred and violence, Crime, Law and Social Change, 80, 237-256. [CrossRef]

- Vargiu, C., Nai. & Valli, C. (2024) Uncivil yet persuasive? Testing the persuasiveness of political incivility and the moderating role of populist attitudes and personality traits, Political Psychology, 45(6), 1157-1176. [CrossRef]

- Vatter, M. (2020) Dignity and the foundation of human rights: Toward an averroist genealogy, Politics and Religion, 13(2), 304-332. [CrossRef]

- Vergani, M. , Perry, B., Freilich, J., Chermark, S., Scrivens, R, Link, R., Kleinsman, D., Betts, J. & Iqbal, M. (2024) Mapping the scientific knowledge and approaches to defining and measuring hate crime, hate speech, and hate incidents: A systematic review, Campbell Systematic Reviews, 20(2), e1397. [CrossRef]

- Vihma, A. , Reischl, G. & Andersen, A.N. (2021) A climate backlash: Comparing populist parties’ climate policies in Denmark, Finland, and Sweden, The Journal of Environment & Development, 30(3), 219-239. [CrossRef]

- von Malmborg, F. (2024a) Strategies and impacts of policy entrepreneurs: Ideology, democracy, and the quest for a just transition to climate neutrality, Sustainability, 16(12), 5272. [CrossRef]

- von Malmborg, F. (2024b) Tidöpolitiken hotar både klimatet och demokratin. Tidningen Syre. 6 April 2024. https://tidningensyre.se/2024/06-april-2024/tidopolitiken-hotar-bade-klimatet-och-demokratin/.

- von Malmborg, F. (2025a) Emotional governance and nasty rhetoric in climate politics: Democracy harms of a far-right populist culture war, European Policy Analysis. [CrossRef]

- von Malmborg, F. (2025b) Weird sporting with double edged swords: Understanding nasty rhetoric in Swedish climate politics, Humanities and Social Science Communications. [CrossRef]

- von Malmborg, F. (2025c) Victims of nasty rhetoric in Swedish climate politics, International Review of Victimology. [CrossRef]

- von Malmborg, F. (2025d) ‘Executed in front of your children’: Writing from the body to understand victims of nasty politics, Humanity & Society. [CrossRef]

- von Stuckrad, K. Western Esotericism: A Brief History of Secret Knowledge; London: Routledge, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Vowles, K. & Hultman, M. (2021a) Dead white men vs. Greta Thunberg: Nationalism, misogyny, and climate change denial in Swedish far-right digital media, Australian Feminist Studies, 36(110), 414-431. [CrossRef]

- Vowles, K. & Hultman, M. (2021b) Scare-quoting climate: The rapid rise of climate denial in the Swedish far-right media ecosystem, Nordic Journal of Media Studies, 3(1), 79-95. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M. & Morisi, D. (2019) Anxiety, fear and political decision making, Oxford Research Encyclopedias Online: Politics. [CrossRef]

- Wahlström, M. , Törnberg, A. & Ekbrand, H. (2021) Dynamics of violent and dehumanizing rhetoric in far-right social media, New Media & Society, 23(11), 3290-3311. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. & Lo, K. (2021) Just transition: A conceptual review, Energy Research & Social Science, 82, 102291. [CrossRef]

- Walther, J.B. Making a case for a social processes approach to online hate. In Social Processes of Online Hate; Walther, J.B., Rice, R.E., Eds.; Oxon: Routledge, 2025; pp. 9–36. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M. From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M. (1968) Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology, New York: Bedminster.

- Weber, E.P. Pluralism by the Rules: Conflict and Cooperation in Environmental Regulation; Washington DC: Georgetown University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks, A.C. & Allen, P. (2023) Backlash against “identity politics”: far right success and mainstream party attention to identity groups, Politics, Groups, and Identities, 11(5), 935-953. [CrossRef]

- Weintrobe, S. Psychological Roots of the Climate Crisis: Neoliberal Exceptionalism and the Culture of Uncare 2021.

- Weise, Z.; Camut, N. Let’s kill the Green Deal together, far-right leader urges EU’s conservatives. Politico. 27 January 2025. https://www.politico.eu/article/lets-kill-eu-green-deal-together-france-far-right-leader-tells-center-right-jordan-bardella/.

- Wheeler, G.J. “Do what thou wilt”: the history of a precept. Religio 2019, 27, 17–44. https://hdl.handle.net/11222.digilib/141542.

- Whillock, R.K.; Slayden, D. Hate Speech; Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- White, M. (2022) Greta Thunberg is ‘giving a face’ to climate activism: Confronting anti-feminist, anti-environmentalist, and ableist memes, Australian Feminist Studies, 36(110), 396-413. [CrossRef]

- White, J. What Makes Climate a Populist Issue? Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment Working Paper 401, London: London School of Economics and Political Science, 2023; https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/working-paper-401-White.pdf.

- Widfeldt, A. The far-right Sweden. In The Routledge Handbook of Far-Right Extremism in Europe; Kondor, K., Littler, M., Eds.; London: Routledge, 2023; pp. 193–206. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, C. Aleister Crowley: The Nature of the Beast; London: Aquarian, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wodak, R. The Politics of Fear: What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean; Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. COP26 special report on climate change and health: the health argument for climate action; Geneva, 2021; https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241514972.

- Yılmaz, F. (2012) Right-wing hegemony and immigration: How the populist far-right achieved hegemony through the immigration debate in Europe, Current Sociology, 60(3), 368-381. [CrossRef]

- Young, M. (2024) Towards a rhetorical theory of charisma: Corinthians, cults, and demagogic criticism, Quarterly Journal of Speech, 111, early view. [CrossRef]

- Zeitzoff, T. Nasty Politics: The Logic of Insults, Threats and Incitement; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zulianello, M. & Ceccobelli, D. (2020) Don’t call it climate populism: on Greta Thunberg’s technocratic ecocentrism, The Political Quarterly, 91(3), 623-631. [CrossRef]

- Zúquete, J.P. Populism and Religion, In: The Oxford Handbook of Populism; Rovira Kaltwasser, C., Taggart, P., Espejo, P.O., Ostiguy, P., Eds.; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017; pp. 445–466. [Google Scholar]

| Type of nasty rhetoric | Description | Level of aggression |

| Insults | Name-calling that influences how people make judgement and interpret situations and could sometimes include dehumanising and enmity rhetoric. | Hate |

| Accusations | Blaming opponents of doing something illegal or shady, or promulgating conspiracy theories about opponents. | Hate |

| Intimidations | Veiled threats advocating economic or legal action against an opponent, e.g., that they should get fired, be investigated or sent to prison. | Threat |

| Incitements | The most aggressive rhetoric includes people threatening or encouraging sometimes fatal violence against opponents. If the statement is followed, which happens, it implies physical harm to, or in the worst case, death of opponents. | Threat |

| Economic/legal violence (repression) | Denunciation, detention | Violence |

| Physical violence | Assault, beating, rape, murder. | Violence |

| Trait | Far-right populism | Christianity |

| Power of Thought | Totalitarian ideology; The Only Truth; Anti-pluralism | Monotheistic religion; Divine law |

| Polarisation | People–Elite; Ingroup–Outgroup; Good–Evil | God–World; Good–Evil; Divine authority–State/church/human authority; Religion–Sophism; Religion–Science; Mind–Body |

| Persuasion | Demagoguery; manipulation; hate; threats; violence; demonisation, dehumanisation | Charisma; demagoguery; manipulation |

| Punishment | Hate; threats; violence; silencing; censoring; state repression (legal, economic) | Hersey; schism; excommunication |

| Disruption | Paradigm shift; iconoclasm; saviourism | Rapture; Judgement Day; salvation; iconoclasm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).