Submitted:

21 May 2025

Posted:

22 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Raw Materials

2.1.2. Pozzolanic Activity of Calcined Laterite

2.1.3. Binder Pastes

2.1.4. Mortar Pastes

- excavation laterite containing by mass fine particles, labelled as LAT70/30,

- partially sieved laterite that contained by mass fine particles, labelled as LAT60/40,

- or the totally sieved laterite containing particles with grain sizes larger than , labelled as LAT0/100.

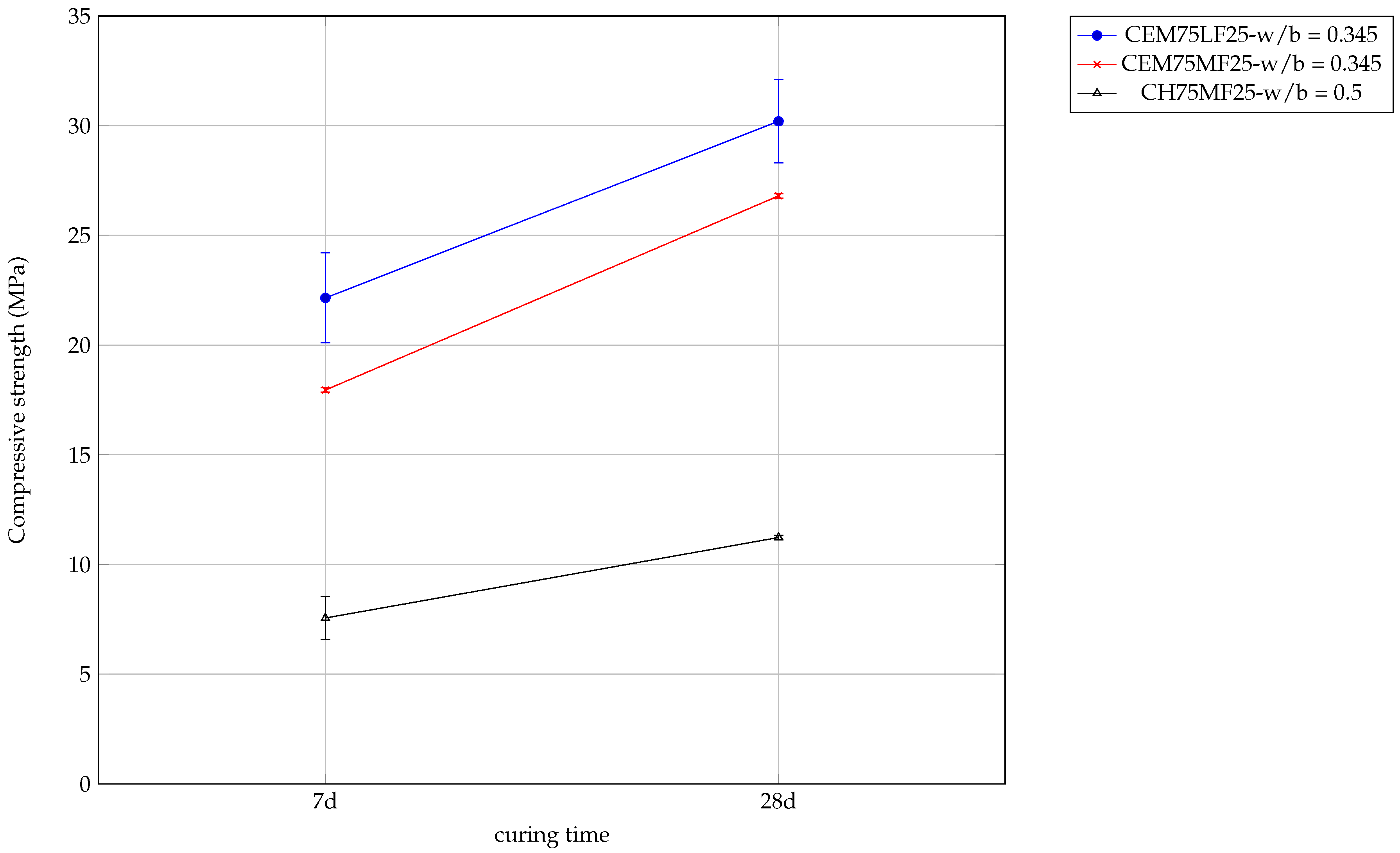

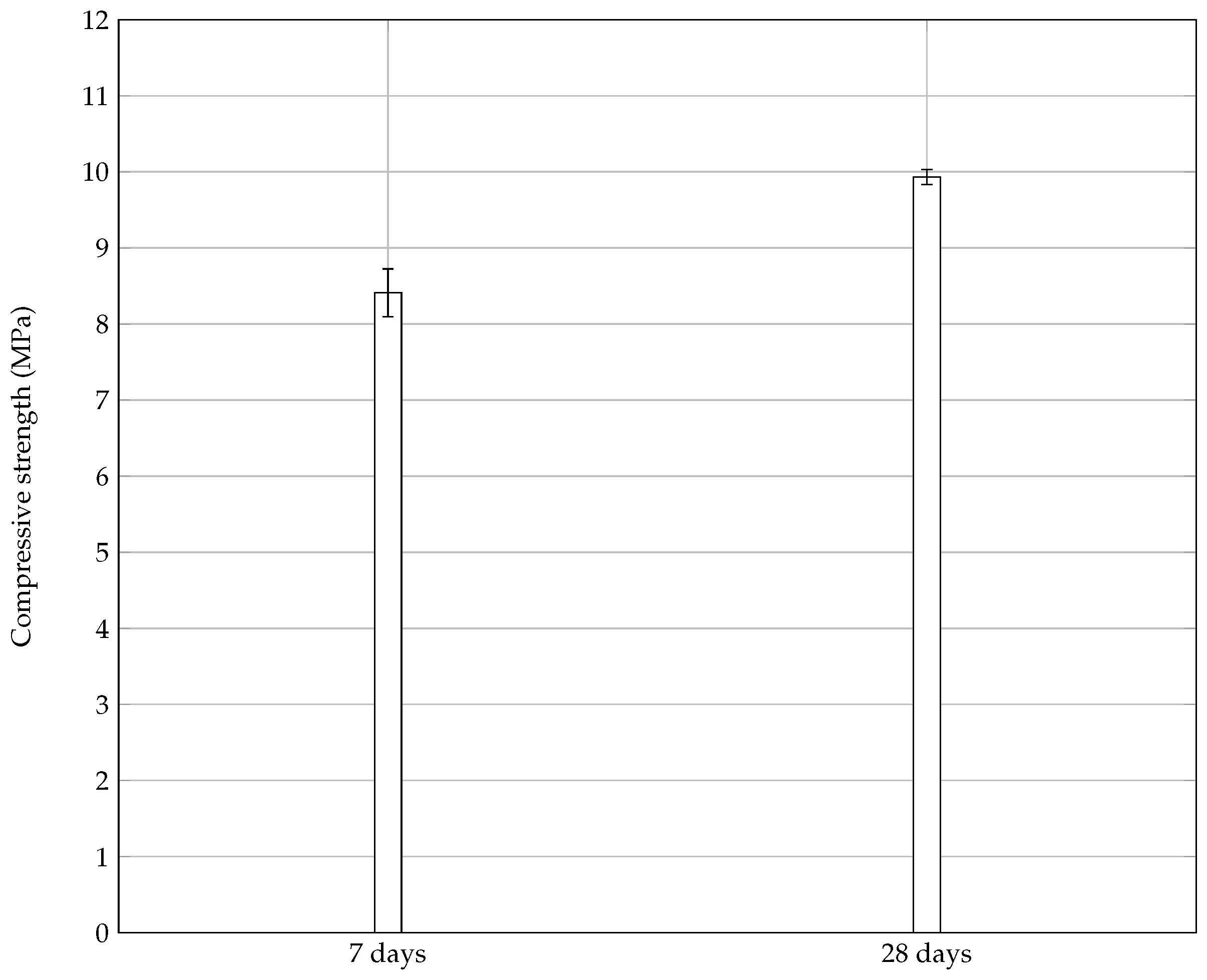

2.1.5. Reuse Potential of End of Life Grinded Mortar

- lime and mortar fines, referred to as CH75MF25, with a water to solid ratio of 0.5;

- CEM and limestone filler, referred to as CEM75LF25,with a water to solid ratio of 0.345;

- CEM and mortar fines, referred to as CEM75MF25, with a water to solid ratio of 0.345.

2.2. Characterization Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Raw Material Analysis

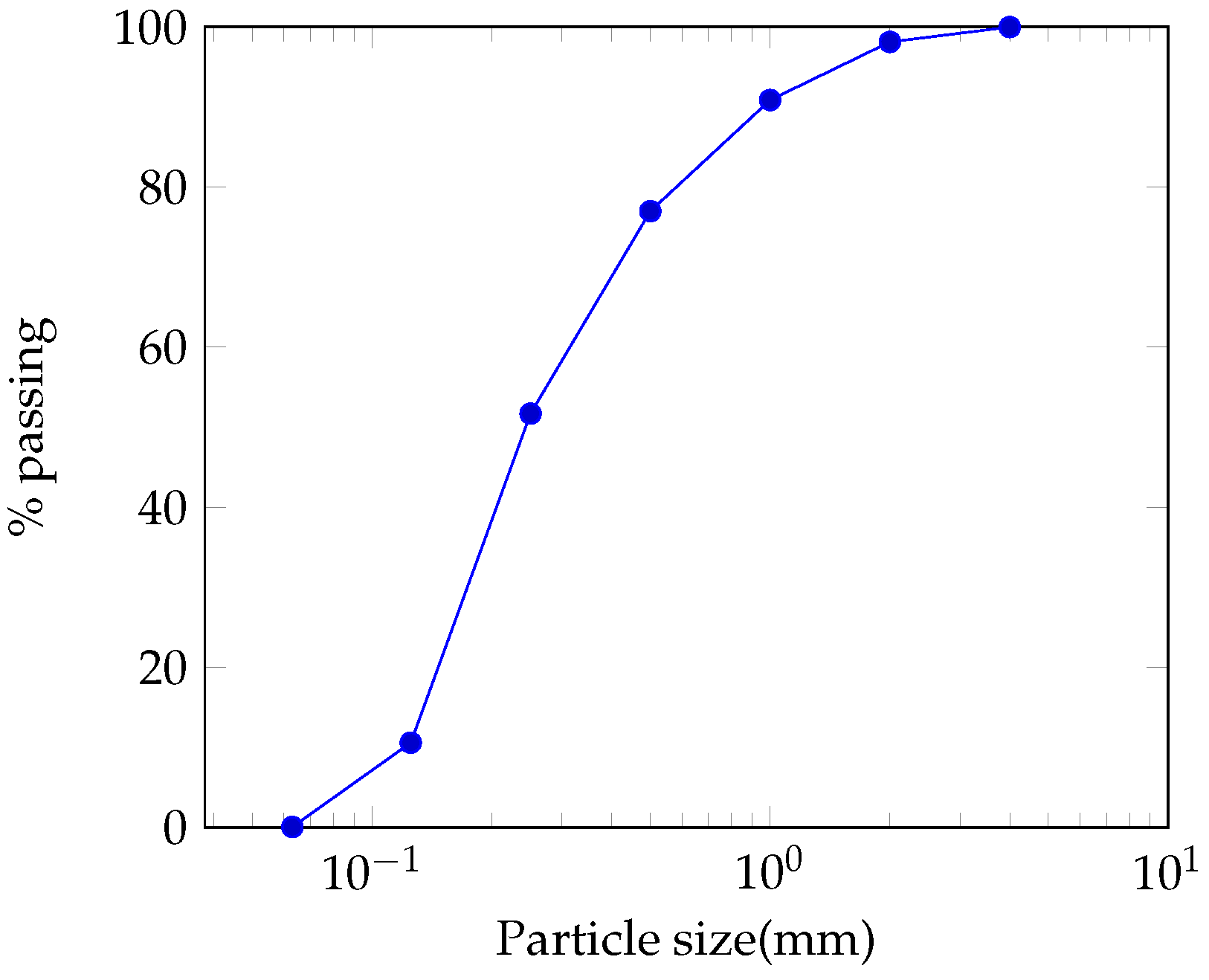

3.1.1. Particle Size

Lateritic Sand

Lateritic Fines

3.1.2. XRF

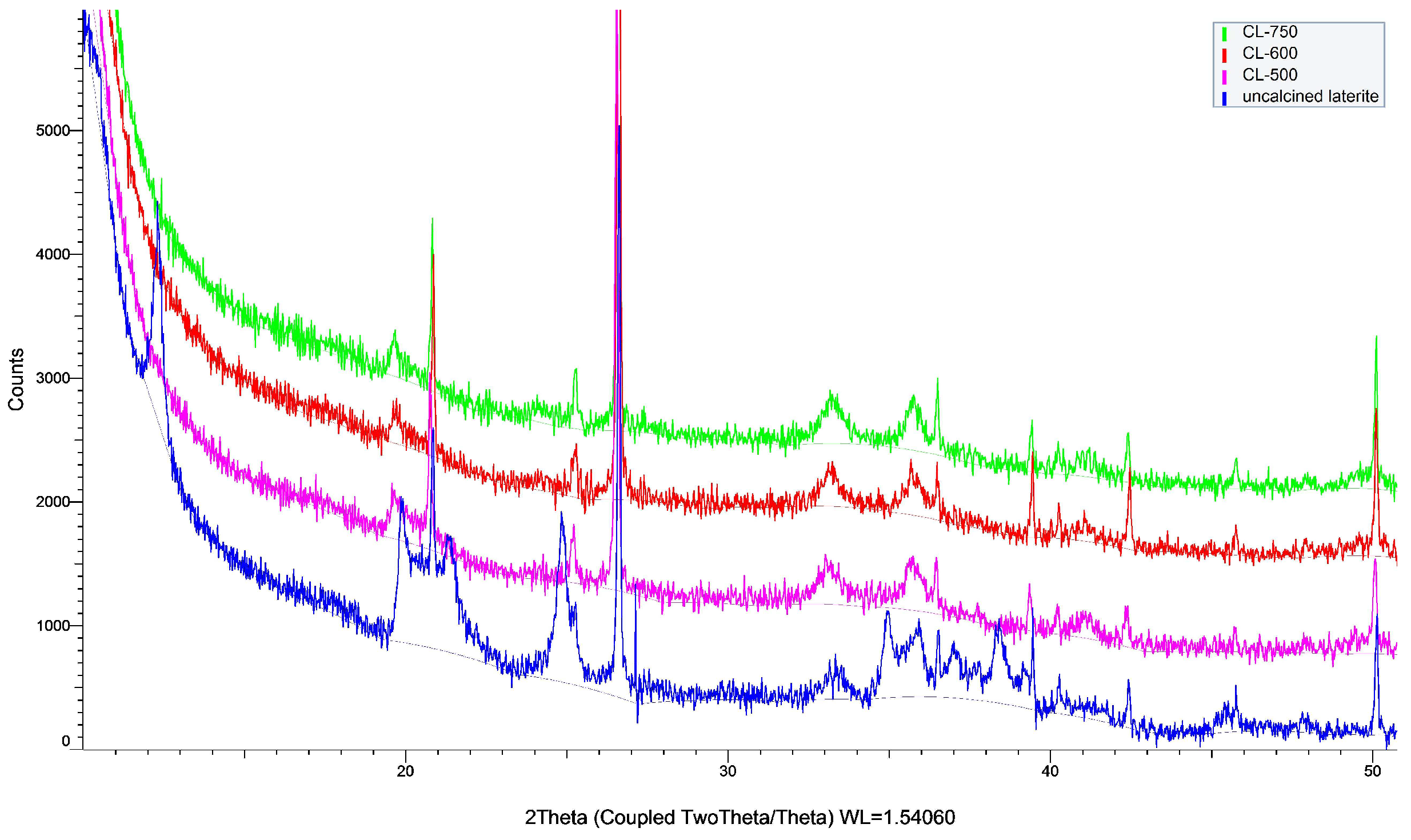

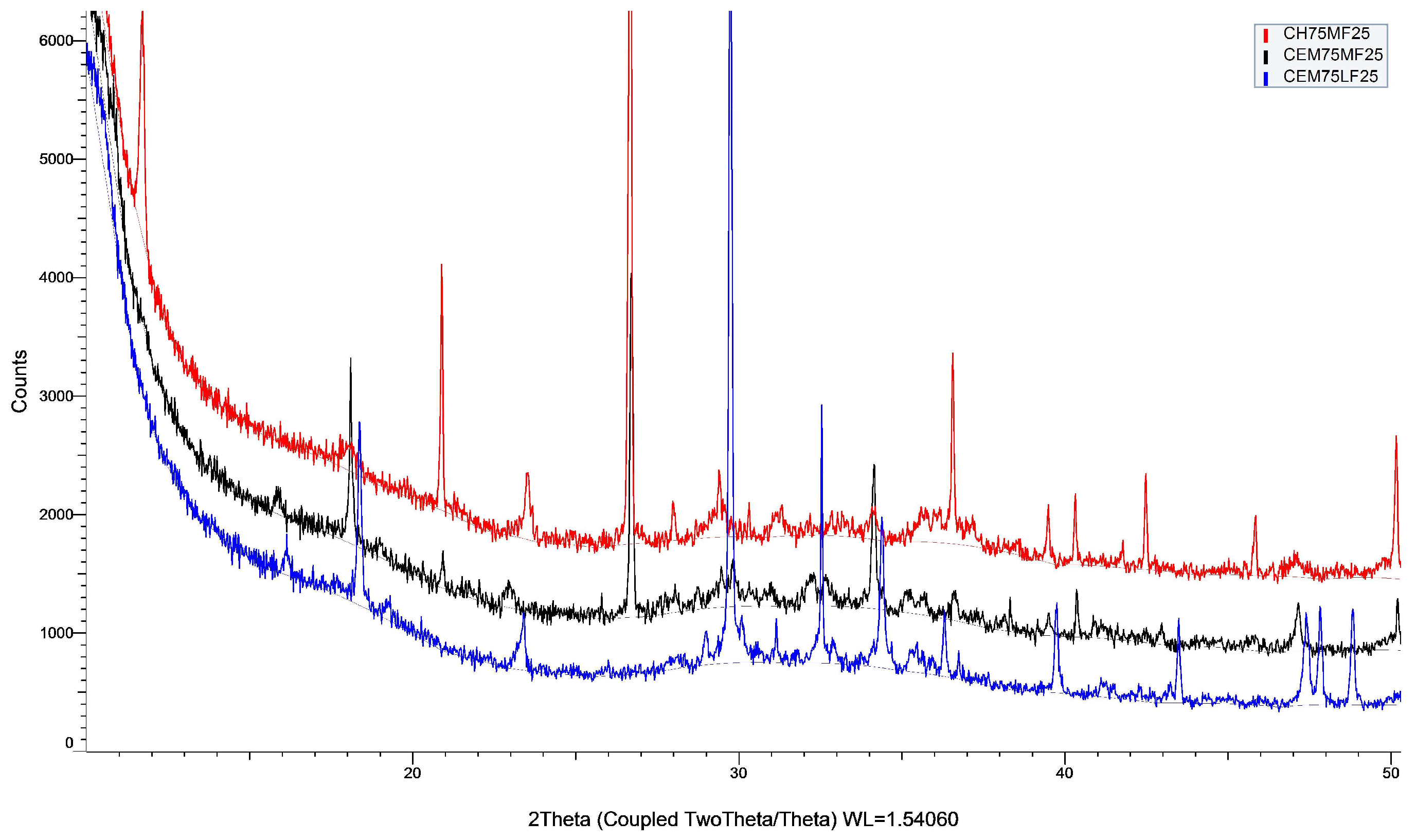

3.1.3. XRD

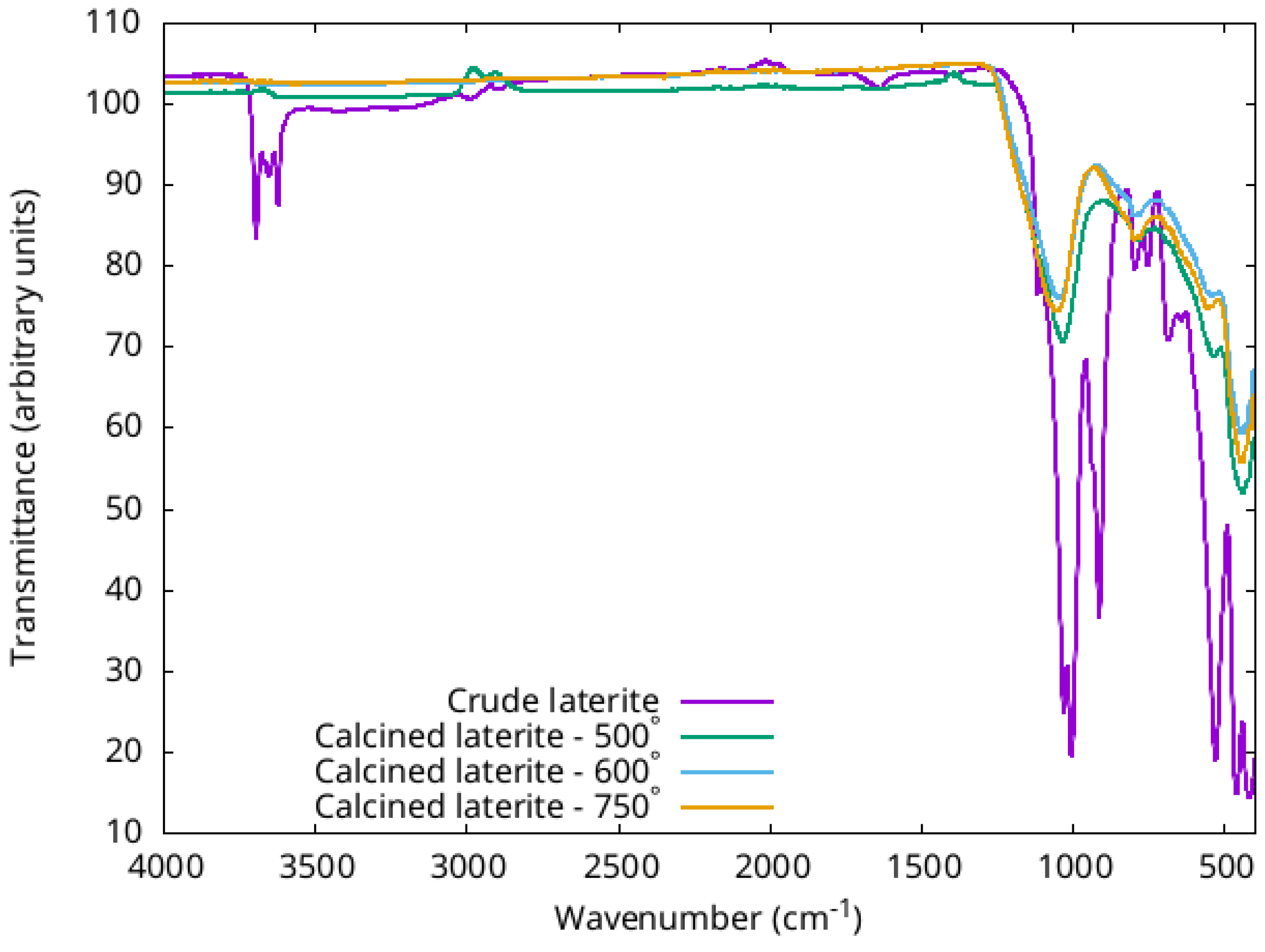

3.1.4. FTIR

- OH stretching bands located at 3686, 3651 and 3610 cm−1. These bands disappear upon calcination: this accounts for deshydroxylation of laterite;

- Si-O deformation bands located at 1119, 1028, 1001 and 684 cm−1. Upon calcination these narrow bands are replaced by a broad peak located at 1036 cm−1, 1045 cm−1 and 1051 cm−1 when the calcination temperature is 500°, 600° and 750° respectively. The shift to higher wavelength is a sign for the phase transformation from kaolinite to metakaolin;

- Al-OH band located at 909 cm−1 that disappear upon calcination;

- the strong narrow peak located at 526 cm−1 is related to the Al-O-Si deformation band, this peak translates to 777cm−1, which is related with a change in Al coordination;

- the band located at 460 cm−1 is related to Si-O-Si vibration modes, upon calcination this band transforms into a broad band of medium intensity located at 533 cm−1, 545 cm−1 and 558 cm−1 when the calcination temperature is 500°, 600° and 750°. The shift of Si-O-Si vibration mode to higher wavelength attests for the appearance of an amorphous structure.

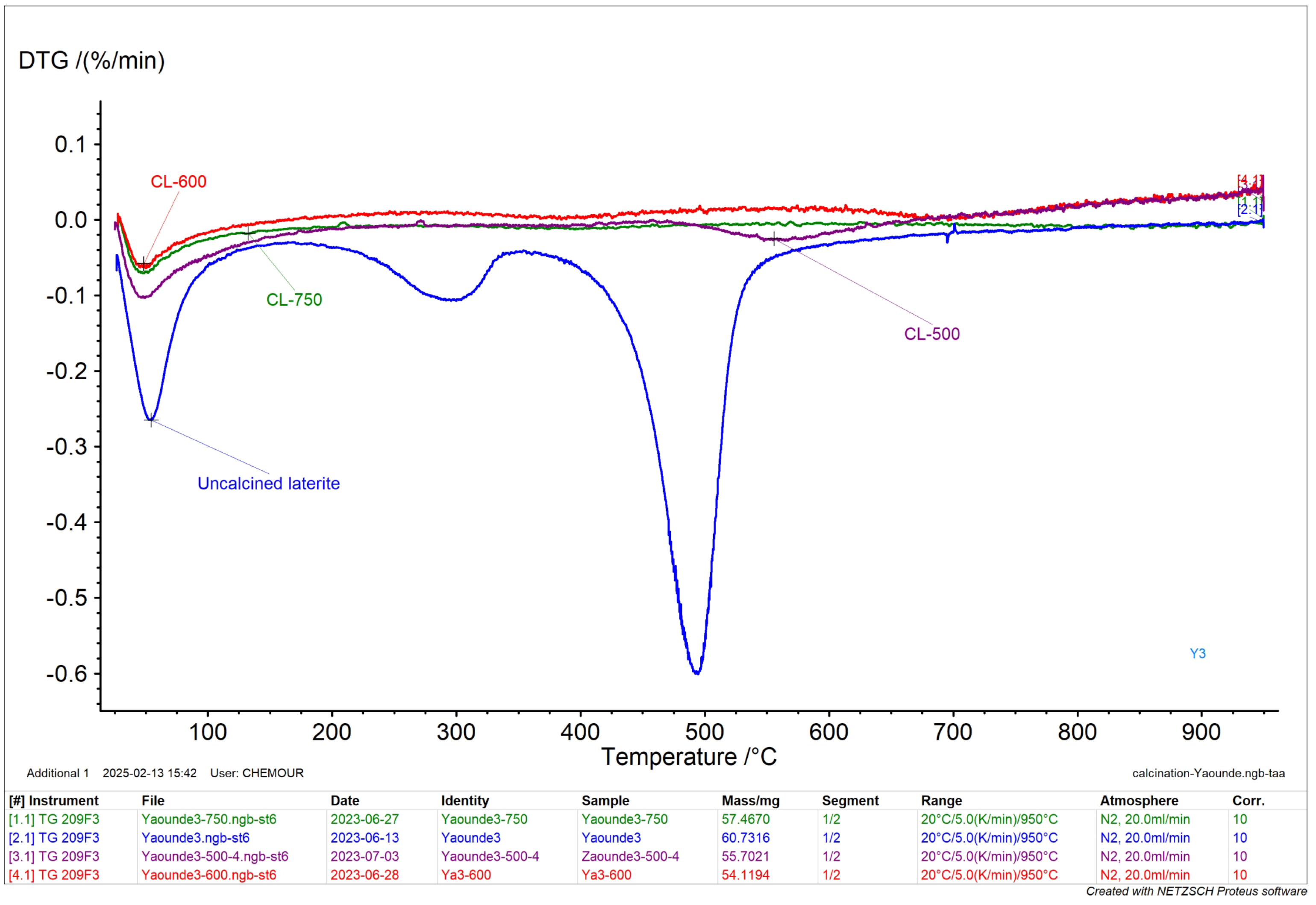

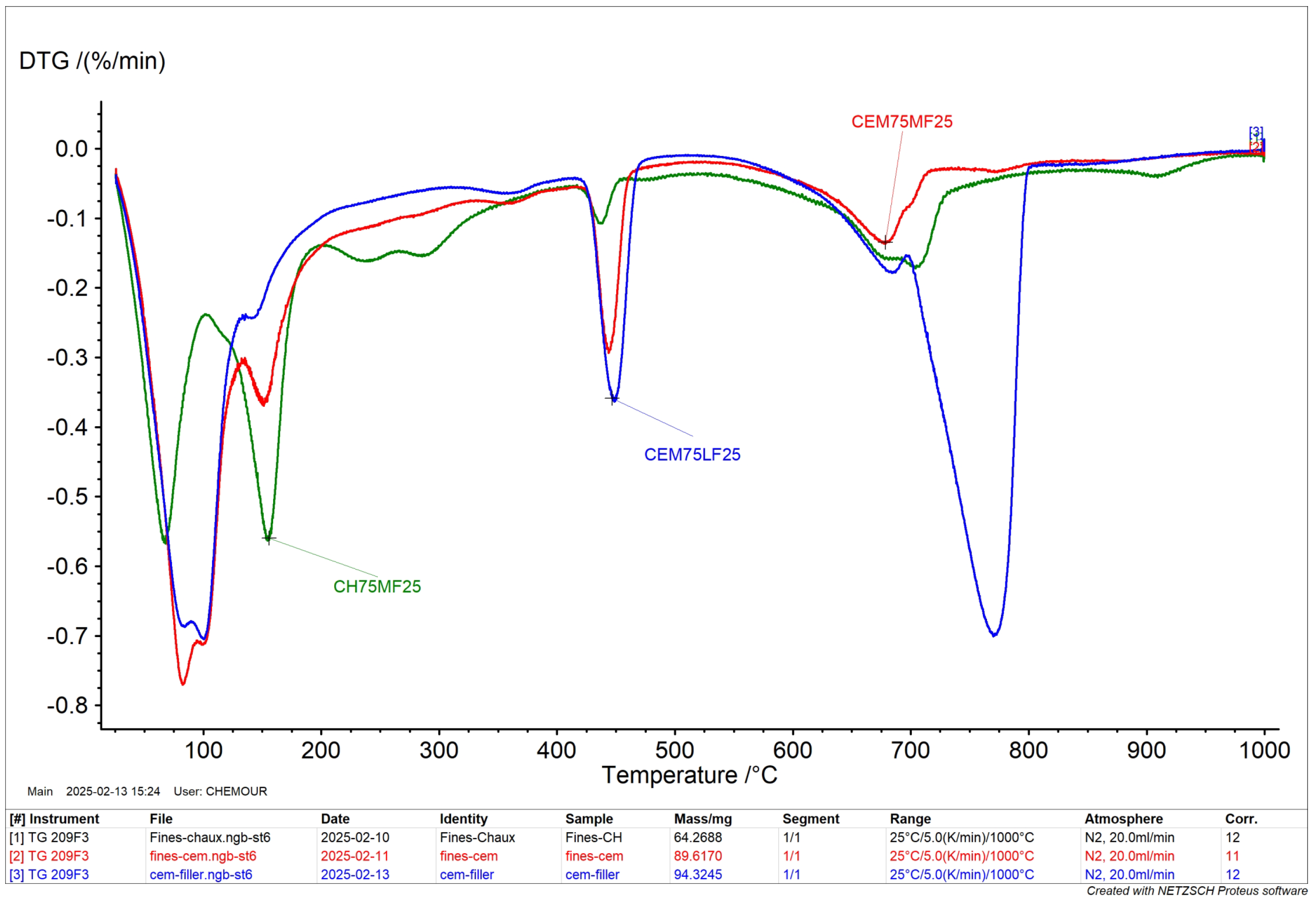

3.1.5. DTG

- the first peak between 25 and 100 °C which corresponds to the loss of adsorbed water;

- the second peak between 225 °C and 325 °C corresponds to the decomposition of organic matter and of goethite to hematite;

- the peak between 400°C and 600 °C corresponds to the dehydroxylation of kaolinite.

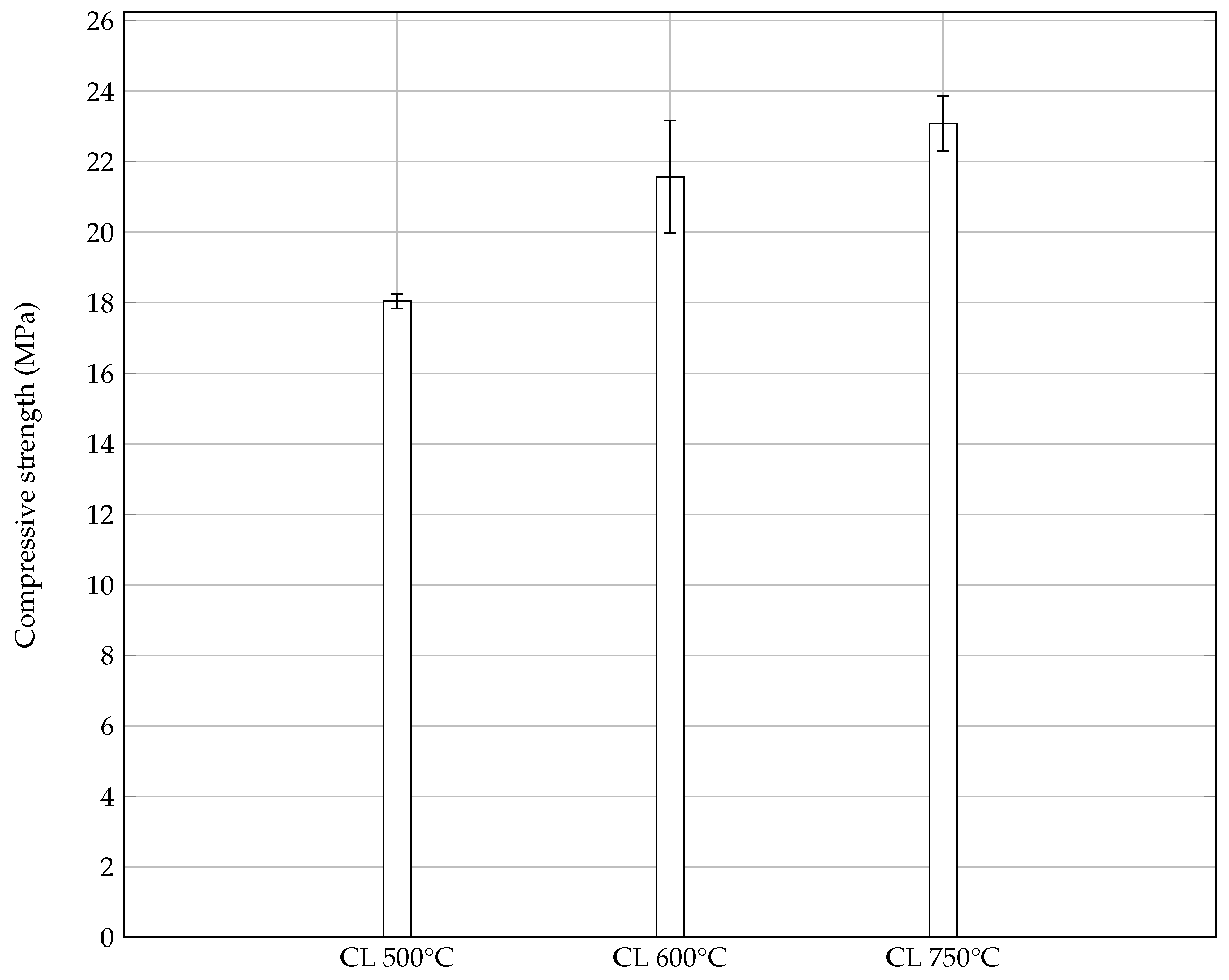

3.2. Pozzolanic Activity of Calcined Laterite

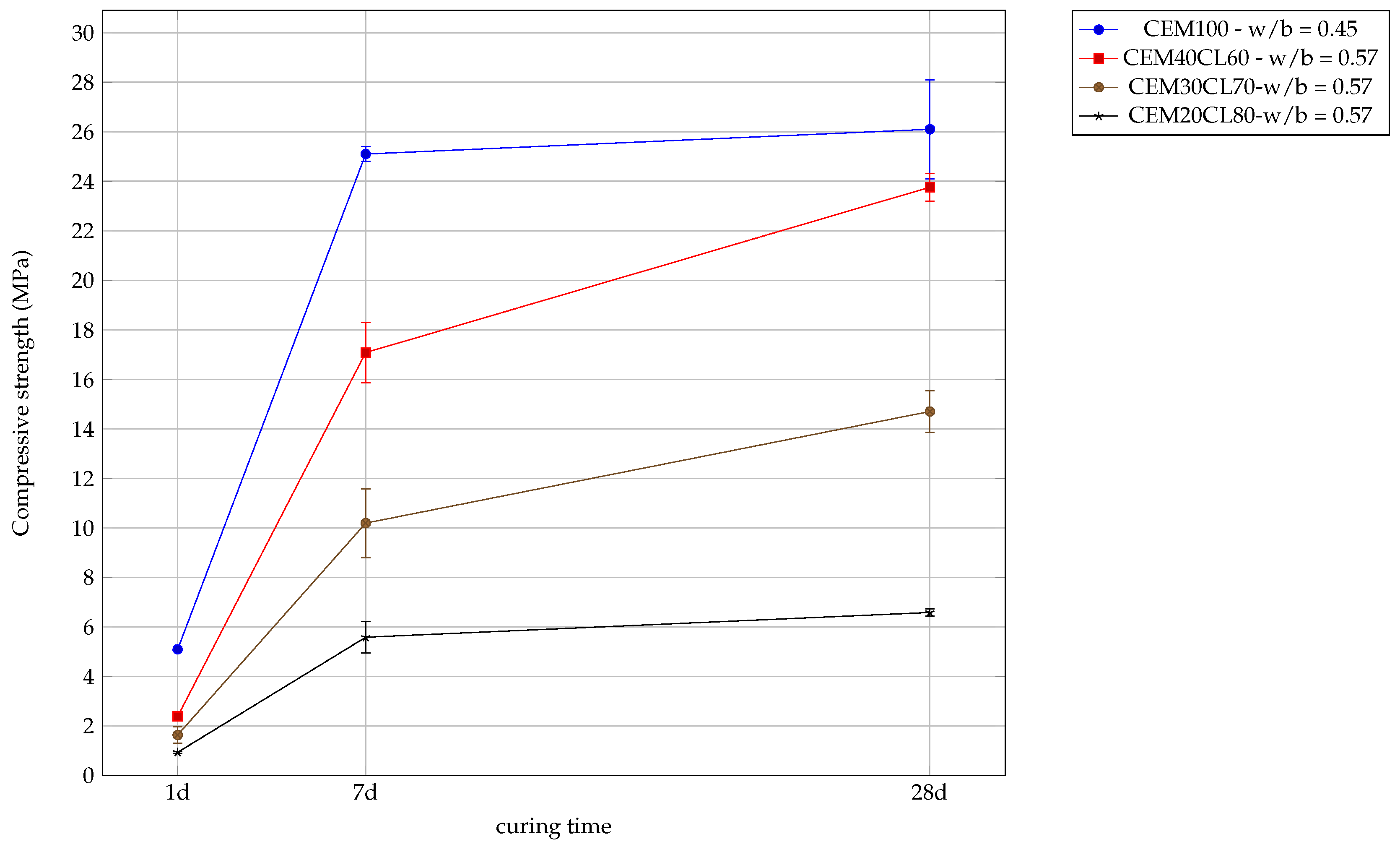

3.3. Eco-Binder Design

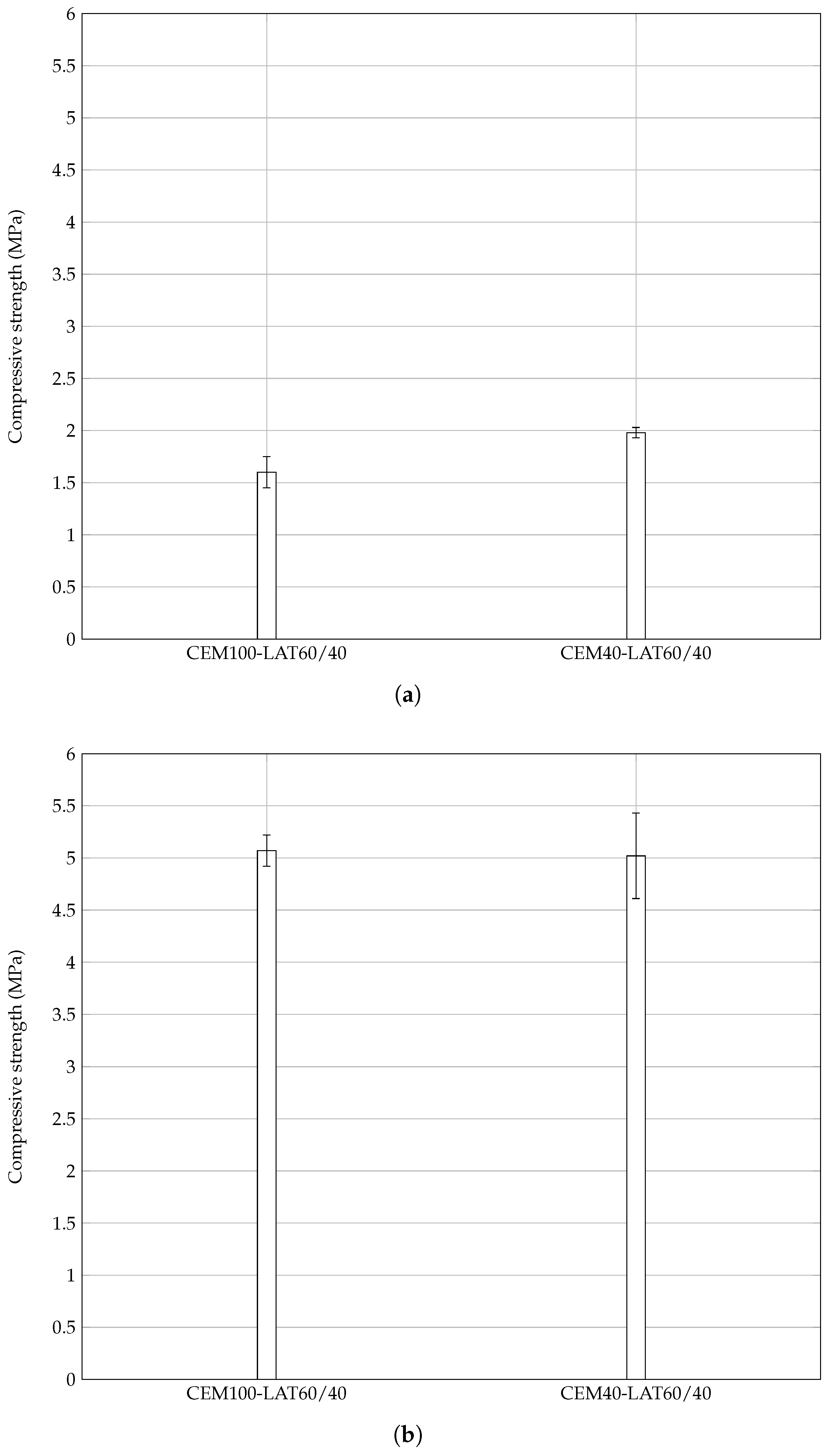

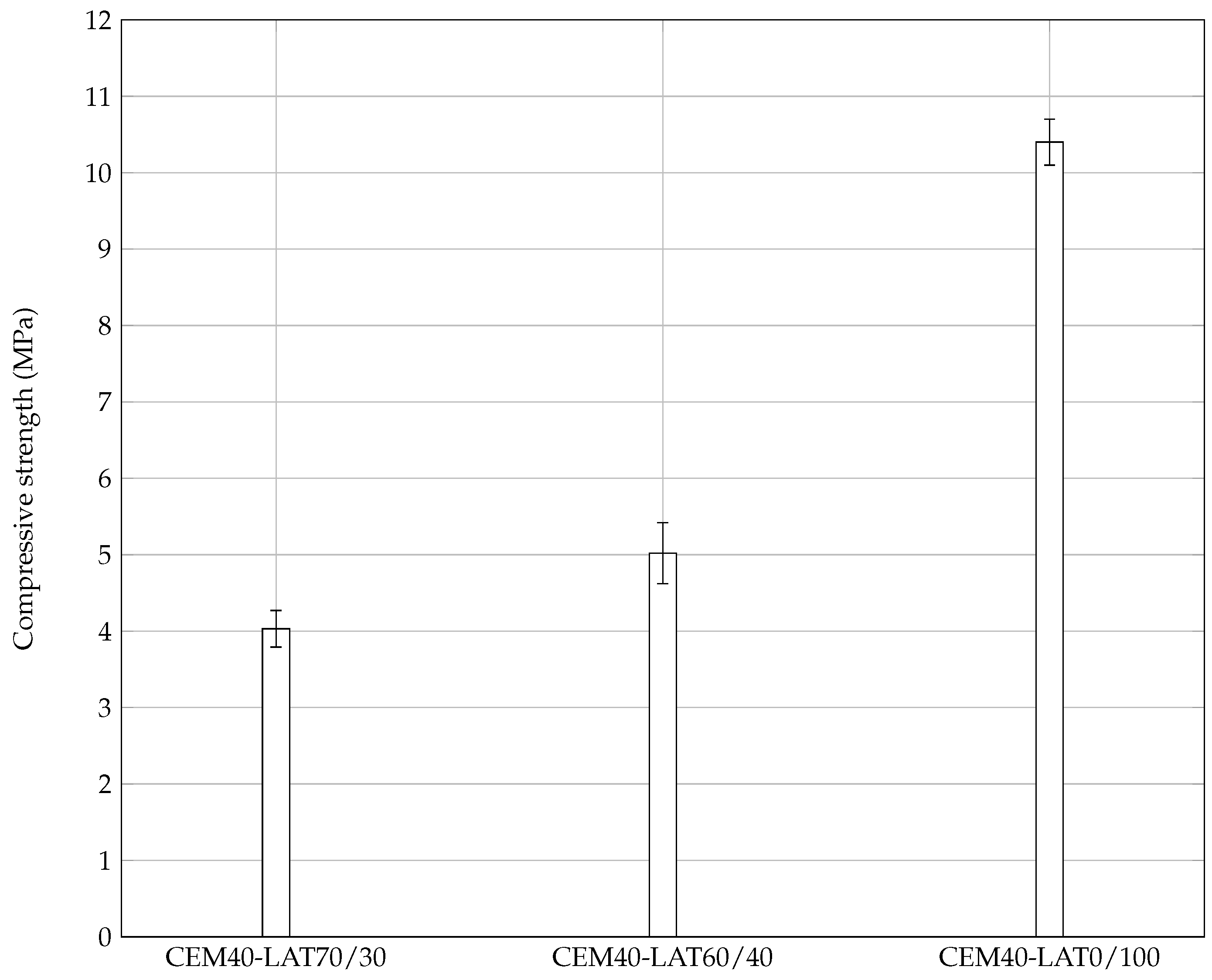

3.4. Mortar Pastes

3.4.1. Mechanical Resistance

3.4.2. Water Absorption by Capillarity Test

3.5. Closing the Loop for the Developed Solution

3.5.1. Pozzolanicity of Mortar Fines

3.5.2. Lime Stabilization of Grinded Mortar

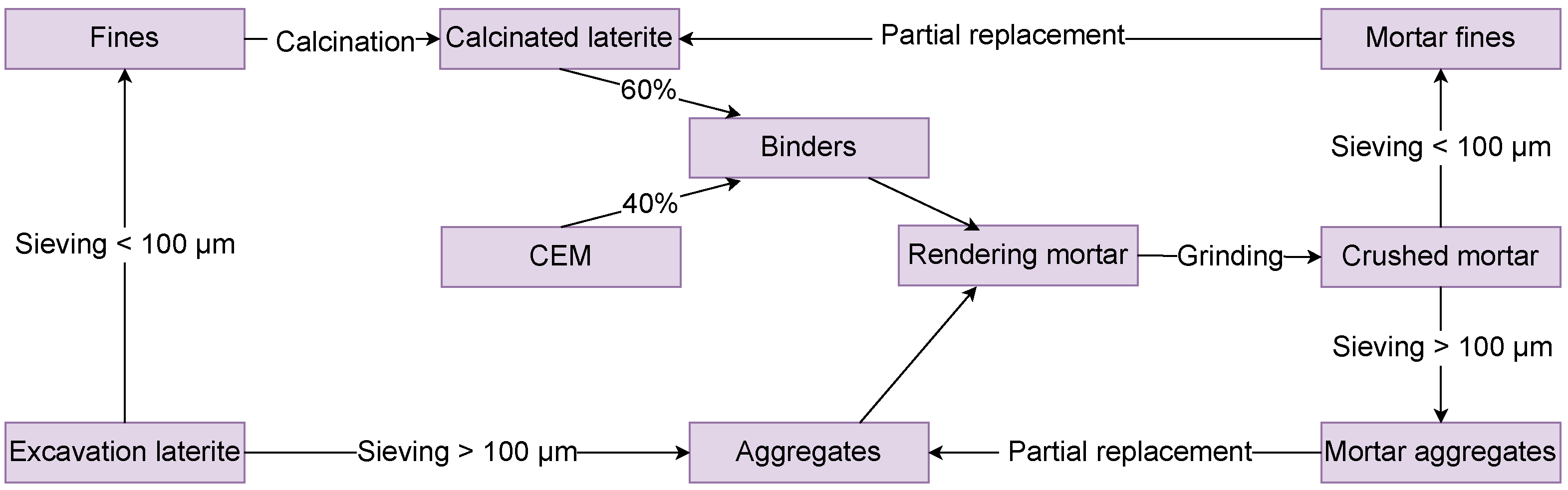

3.5.3. Life Cycle of the Developed Solution

- the fines, with particle sizes smaller than , as partial replacement for the calcined laterite, leading to further energy savings;

- the larger aggregates, with sizes larger than as partial replacement for the lateritic sand.

4. Conclusions

- replacing of cement by calcined laterite enables to achieve acceptable mechanical strength for cement pastes;

- replacing of cement by calcined laterite enables to achieve the same compression strength than a 100% cement paste for similar workability.

- mortar fines are pozzolanic and can enter the binder formulation developed here as partial replacement of the calcined laterite, leading to further energy savings;

- the larger particles have the ability to substitute laterite sand in the developed rendering mortar, or equivalent mortars.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PC | Portland cement |

| CL | calcined laterite |

| CH | Hydrated calcium hydroxyde |

| LATx/100-x | laterite sand containing of fines (<100) |

References

- Serdar, M.; Bjegovic, D.; Stirmer, N.; Pecur, I. B. Alternative binders for concrete: opportunities and challenges. Gradevinar 2019, 71, 200–218. [Google Scholar]

- Bendixen, M.; Iversen, L. L.; Best, J.; Franks, D. M.; Hackney, C. R.; Latrubesse, E. M.; Tusting, L. S. Sand, gravel, and UN Sustainable Development Goals: Conflicts, synergies, and pathways forward. One Earth 2021, 4, 1095–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mougoue, B.; Laurentine, N. E. Croissance de la ville de Yaoundé et résiliences aux pandémies. Espace Géographique et Société Marocaine 2021, 43-44, 339–353. [Google Scholar]

- Djatcheu, M.L. Fabriquer la ville avec les moyens du bord: L’habitat précaire à Yaoundé (Cameroun). Géoconfluences 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Moutila, B.L. Pression et dynamique de l’espace côtier à mangrove de Youpwê (Douala). Proceedings of XVIe Colloque International du SIFEE, Yaoundé, september 12-15, 2011.

- Tchamba, A. B.; Nzeukou, A. N.; Tené, R. F.; Melo, U. C. Building potentials of stabilized earth blocks in Yaounde and Douala (Cameroon). Int. J. Civ. Eng. Res. 2012, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lemougna, P.N.; Melo, U.F.C.; Kamseu, E.; Tchamba, A.B. Laterite Based Stabilized Products for Sustainable Building Applications in Tropical Countries: Review and Prospects for the Case of Cameroon. Sustainability 2011, 3, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eko, R. M.; Mpele, M.; Doumtsop, M. D.; Minsili, L. S.; Wouatong, A. S. Some hydraulic, mechanical, and physical characteristics of three types of compressed earth blocks. Agric. Eng. Int.: CIGR Journal 2006, 8, BC 06 007. [Google Scholar]

- Darman, J. T.; Tchouata, J. H. K.; Ngôn, G. F. N.; Ngapgue, F.; Ngakoupain, B. L.; Langollo, Y. T. Evaluation of lateritic soils of Mbé for use as compressed earth bricks (CEB). Heliyon 2022, 8, e10147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Essa, L. K.; Kaze, R. C.; Nemaleu, J. G. D.; Tchakoute, H. K.; Meukam, P.; Kamseu, E.; Leonelli, C. Engineering properties, phase evolution and microstructure of the iron-rich aluminosilicates-cement based composites: Cleaner production of energy efficient and sustainable materials. Clean. Mater. 2021, 1, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onugba, M. A.; Eze, C. O.; Atonu, Y. A.; Alih, U. Influence of Fly Ash and Palm Fibre on the Mechanical Properties of Compressed Stabilized Earth Blocks. Asian J. Curr. Res. 2024, 9(4), 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodounon, N. A.; Kanali, C.; Mwero, J. Compressive and flexural strengths of cement stabilized earth bricks reinforced with treated and untreated pineapple leaves fibres. Open J. Compos. Mater. 2018, 8(4), 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yannick, T. L.; Ali, T. O.; Taypondou, D. J.; Kom, M. I. L. F.; Luc, A. L.; Ngueyep, L. L. M.; Mache, J. R. Statistical analysis of Nkoulou soils properties and suitability for earthen constructions. Heliyon 2022, 8(10), e11141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeleke, B. K.; Oladipo, A. A.; Alfa, N. M.; Atere, O. A. Comparative Study of Cement and Lime Stabilized Laterite for Compressed Earth Bricks. Journal of Chemical, Mechanical and Engineering Practices 2025, 5, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Salleh, N.M.; Roslan, M.H. The stabilization of compressed earth blocs using fly ash. Infrastructure University Kuala Lumpur Research Journal 2015, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Mimboe, A. G.; Abo, M. T.; Djobo, J. N. Y.; Tome, S.; Kaze, R. C.; Deutou, J. G. N. Lateritic soil based-compressed earth bricks stabilized with phosphate binder. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 31, 101465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukpata, J. O.; Ephraim, M. E.; Akeke, G. A. Compressive strength of concrete using lateritic sand and quarry dust as fine aggregate. ARPN J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2012, 7(1), 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Raja, R.; Vijayan, P.; Kumar, S. Durability studies on fly-ash based laterized concrete: A cleaner production perspective to supplement laterite scraps and manufactured sand as fine aggregates. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 366, 132908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaze, R. C.; Naghizadeh, A.; Tchadjie, L.; Adesina, A.; Djobo, J. N. Y.; Nemaleu, J. G. D.; Kamseu, E.; Melo, U.C.; Melo, U.C.; Tayeh, B. A. Lateritic soils based geopolymer materials: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 344, 128157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaze, C. R.; Lemougna, P. N.; Alomayri, T.; Assaedi, H.; Adesina, A.; Das, S. K.; Lecomte-Nana, G.; Kamseu, E.; Melo, U.C.; Leonelli, C. Characterization and performance evaluation of laterite based geopolymer binder cured at different temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 270, 121443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaze, C. R.; Lecomte-Nana, G. L.; Adesina, A.; Nemaleu, J. G. D.; Kamseu, E.; Melo, U. C. Influence of mineralogy and activator type on the rheology behaviour and setting time of laterite based geopolymer paste. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 126, 104345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, A.; Felaous, K.; Alomayri, T.; Jindal, B. B. A state-of-the-art review of the structure and properties of laterite-based sustainable geopolymer cement. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 54333–54350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metekong, J. V. S.; Kaze, C. R.; Adesina, A.; Nemaleu, J. G. D.; Djobo, J. N. Y.; Lemougna, P. N.; Tatietse, T. T. Influence of thermal activation and silica modulus on the properties of clayey-lateritic based geopolymer binders cured at room temperature. Silicon 2022, 14, 7399–7416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudeu, R. C.; Ekani, C. J.; Djangang, C. N.; Blanchart, P. Role of Heat-Treated Laterite on the Strengthening of Geopolymer Designed with Laterite as Solid Precursor. Ann. Chim. Sci. Mat. 2019, 43, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaze, R. C.; à Moungam, L. B.; Djouka, M. F.; Nana, A.; Kamseu, E.; Melo, U. C.; Leonelli, C. The corrosion of kaolinite by iron minerals and the effects on geopolymerization. Appl. Clay Sci. 2017, 138, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaze, C. R.; Lecomte-Nana, G. L.; Adesina, A.; Nemaleu, J. G. D.; Kamseu, E.; Melo, U. C. Influence of mineralogy and activator type on the rheology behaviour and setting time of laterite based geopolymer paste. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 126, 104345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musbau, K. D.; Kolawole, J. T.; Babafemi, A. J.; Olalusi, O. B. Comparative performance of limestone calcined clay and limestone calcined laterite blended cement concrete. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2021, 4, 100264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaze, R. C., Bikoko. Influence of calcined laterite on the physico-mechanical, durability and microstructure characteristics of portland cement mortar. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2024, 9, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A. T.; Damini, R. G.; Akosubo, I. S. Utilization of Calcined Lateritic Soil as Partial Replacement of Cement on Concrete Strength. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2019, 10(12), 100–104. [Google Scholar]

- Sabir, B. B.; Wild, S.; Bai, J. Metakaolin and calcined clays as pozzolans for concrete: a review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2001, 23, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tironi, A.; Trezza, M. A.; Irassar, E. F.; Scian, A. N. Thermal treatment of kaolin: effect on the pozzolanic activity. Procedia Mater. Sci. 2012, 1, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguwa, J. I. Study of compressive strengths of laterite-cement mixes as a building material. Assumption University Journal of Technology 2009, 13(2), 114–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gameiro, A., Silva. Physical and chemical assessment of lime–metakaolin mortars: Influence of binder: aggregate ratio. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2014, 45, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavali, Rama Vara Prasad, Reddy, P. Swelling and compressibility characteristics of bentonite and kaolin clay subjected to inorganic acid contamination. Int. J. Geotech. Eng. 2017, 12, 1–7.

- Danner, T.; Norden, G.; Justnes, H. Characterisation of calcined raw clays suitable as supplementary cementitious materials. Appl. Clay Sci. 2018, 162, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroke, U. O.; Abdulkarim, A.; Ogubunka, R. O. Fourier-transform infrared characterization of kaolin, granite, bentonite and barite. ATBU journal of environmental technology 2013, 6, 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Öz, A.; Bayrak, B.; Kavaz, E.; Kaplan, G.; Çelebi, O.; Alcan, H. G.; Aydın, A. C. The radiation shielding and microstructure properties of quartzic and metakaolin based geopolymer concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 342, 127923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengyang, P.; Rangsriwatananon, K.; Chaisena, A. Preparation of zeolite N from metakaolinite by hydrothermal method. J. Ceram. Process. Res. 2015, 16, 111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, G. S.; Saini, P. K.; Deoliya, R.; Mishra, A. K.; Negi, S. K. Characterization of laterite soil and its use in construction applications: a review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 16, 200120. [Google Scholar]

- Pera, J.; Ambroise, J.; Momtazi, A. S. Investigation of Pozzolanic Binders Containing Calcined Laterites. MRS Online Proceedings Library (OPL). 1991, 245, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, R.; Martirena, F.; Scrivener, K. L. The origin of the pozzolanic activity of calcined clay minerals: A comparison between kaolinite, illite and montmorillonite. Cem. Concr. Res. 2011, 41, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moropoulou, A.; Bakolas, A.; Aggelakopoulou, E. Evaluation of pozzolanic activity of natural and artificial pozzolans by thermal analysis. Thermochim. Acta 2004, 420, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eires, R.; Nunes, J. P.; Fangueiro, R.; Jalali, S.; Camões, A. New eco-friendly hybrid composite materials for civil construction. Proceedings of ECCM 12 - European Conference on Composite Materials, Biarritz, 2006.

- Ghorbel, H.; Samet, B. Effect of iron on pozzolanic activity of kaolin. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 44, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, M.; Tanaçan, L.; Barış, K. E. Improving the strength of metakaolin-lime based binder. In MATEC Web of Conferences, Proceedings of SUBLime Conference 2024 – Towards the Next Generation of Sustainable Masonry Systems: Mortars, Renders, Plasters and Other Challenges, Funchal, Madeira, Portugal, November 11-12, 2024; Volume 403, p. 02006.

- Zhao, Q.; Tu, J.; Han, W.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y. Hydration properties of portland cement paste with boron gangue. Adv. mater. sci. eng. 2020, 2020(1), 7194654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, M. H.; Soares, G. S.; Romano, R. C. D. O.; Cincotto, M. A. Monitoring of Portland cement chemical reaction and quantification of the hydrated products by XRD and TG in function of the stoppage hydration technique. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2019, 136(3), 1269–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| label | CEM II | calcined laterite | w/b |

| CEM100 | 100 | 0 | 0.45 |

| CEM20CL80 | 20 | 80 | 0.57 |

| CEM30CL70 | 30 | 70 | 0.57 |

| CEM40CL60 | 40 | 60 | 0.57 |

| Label | Binder % weight composition | Lateritic sand granulometry (% particule size distribution) | w/b | ||

| CEM II | Calcined laterite | ||||

| CEM100-LAT 60/40 | 100 | 0 | 60 | 40 | 1.35 |

| CEM40- LAT 60/40 | 40 | 60 | 60 | 40 | 1.35 |

| CEM40- LAT 70/30 | 40 | 60 | 70 | 30 | 1.98 |

| CEM40- LAT 0/100 | 40 | 60 | 0 | 100 | 0.88 |

| CL | |||||||||||

| CEM | 0.43 |

| Water absorption by capillarity coefficient | |

| CEM100-LAT40/60 | 0.011 |

| CEM40-LAT30/70 | 0.026 |

| CEM40-LAT40/60 | 0.039 |

| CEM40-LAT100/0 | 0.051 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).