1. Introduction

Sustainable development highlights the necessity of conserving natural resources and reducing environmental pollution. Today, plastic waste is viewed as a valuable resource that requires effective management policies and efficient recycling mechanisms [1, 2] . In Algeria, the largest country in Africa by area, more than 13.1 million tons of household and similar wastes (HSW) were generated in 2019, and15.31% of that quantity were plastic [

3]. Today, the major challenge lies in the disposal of this waste which is often buried or incinerated. However, over the past few years, a new trend that consists of using recycled plastic waste as artificial aggregates to replace natural aggregates in cementitious materials has emerged [

4].

It was shown that the properties of the incorporated aggregates have a significant impact on the quality of concrete [5, 6], which means that their selection and the proportions used are highly important.

Lightweight aggregates (LWA) are used in cementitious materials because they possess several advantages, such as their reduced density as well as their insulating and soundproofing properties[

7].

It is worth noting that the direct incorporation of recycled plastics as aggregates or fibers in the construction materials has shown promising signs of feasibility [8-34]. To the best of our knowledge, little research has focused on the possibility of incorporating plastic-based synthesized aggregates in concrete as an indirect replacement [35-38] [39-43]. In this context, [

44] and et [

45] prepared synthetic lightweight aggregates (SLAs) from a mixture of fly ash and plastics, such as polystyrene (PS), low-density polyethylene (LDPE), high-density polyethylene (HDPE), and a mixture of various plastics (MP), at different (fly ash-to-plastic) ratios ranging from 0:100 to 80:20, to be incorporated into concrete and pavement. In this context, Binici et al. [

46] developed cement-free concretes, using different types of sand, with 33.3% PET by weight. For this, the PET plastic waste was mechanically crushed and transformed into fibers. Then, mortars were prepared by mixing the PET fibers with different types of sands, in a temperature range extending from 200 to 210 °C. The same authors found out that the composites, which contained plastics without cement, exhibited satisfactory test results. It was particularly shown that the strengths of the composites containing quartz and limestone were higher than those of control samples by 35%. In addition, waste plastic lightweight aggregates (WPLAs) could be produced from PET plastic wastes using granulated blast furnace slag (GBFS) [

47] and also from PET wastes with river sand aggregates [48-50]. Likewise, Bouaziz et al. [

51] manufactured a lightweight composite aggregate containing polypropylene coated with a layer of ceramic powder to replace ordinary natural aggregates in concrete. They then noticed that their compressive strength increased by 8% in compared with that observed for the same content of polypropylene beads introduced directly into the cement matrix. The previous 8% strength increase was recorded following the addition of 30% of polypropylene beads coated with fine ceramic powder. The authors explained this observation by the fact that the polypropylene grains remain in their volume space, which engenders good homogenization of the lightweight concrete matrix. They then concluded that wrapping the polypropylene beads with marble powder improves the compressive strength of concrete. As for Alqahtani et al. [

52], they manufactured recycled plastic aggregates (RPA) by mixing recycled plastic, i.e. linear low-density polyethylene (LLDPE), and red sand, fly ash, quarry fines or silica fumes, in respective proportions of 30 and 70%. Likewise, Liu et al. [

53] showed that it is indeed possible to manufacture lightweight aggregates by incorporating shredded automobile plastics waste into clay at 1200°C. With regard to Ennahal et al. [

54], they prepared lightweight aggregates based on marine sediments and recycled thermoplastic waste (PP/PS and PP/PE) using a vacuum extruder, at mixing temperatures ranging from 200 to 230 °C.

On the other hand, Del Rey Castillo et al. [

36] conducted a study on the development of lightweight concrete using artificial aggregates made from plastic waste. According to these authors, the mixture with 15% substitution percentage showed quite interesting compressive strength properties (20 MPa at 28 days) with a density of 1800 kg/m

3. Moreover, Gorak et al. [

55] produced lightweight composite aggregates from waste, mainly recycled PET. Furthermore, two production technologies, using various synthesis mechanisms and different temperatures, were tested. On the other side, Erdogmus et al. [

56] investigated the possibility of using expanded polystyrene (EPS) as well as used waste rubber tire power (WRTP) in fired clay bricks for green and cleaner constructions. For this, different ratios of EPS and WRTP were mixed with clay. The resulting mixtures were then fired at 1000 °C.

Furthermore, it was found that increased porosity was formed between the cement paste and plastic aggregates with smooth surfaces and flaky shapes, leading to decreased bond strength, increased permeability of the resulting concrete, and decreased overall mechanical performance of the final composite. To address these problems, it is highly recommended to use finer plastic waste fractions, in the form of granules or powder, rather than coarser fractions or elongated and flaky shapes. In addition, the mechanical or chemical treatment of the surface of the plastic aggregate particles to increase their roughness can improve the bonding within the interstitial zones (ITZ). In addition, the addition of pozzolanic admixtures, such as supplementary binders, is also recommended to improve the microstructure of the matrix. Finally, the conversion of plastic particles into new lightweight aggregates by thermal treatment and their combination with natural or mineral admixtures are also recommended. It has been revealed that all these corrective measures are viable guidelines for future research work [

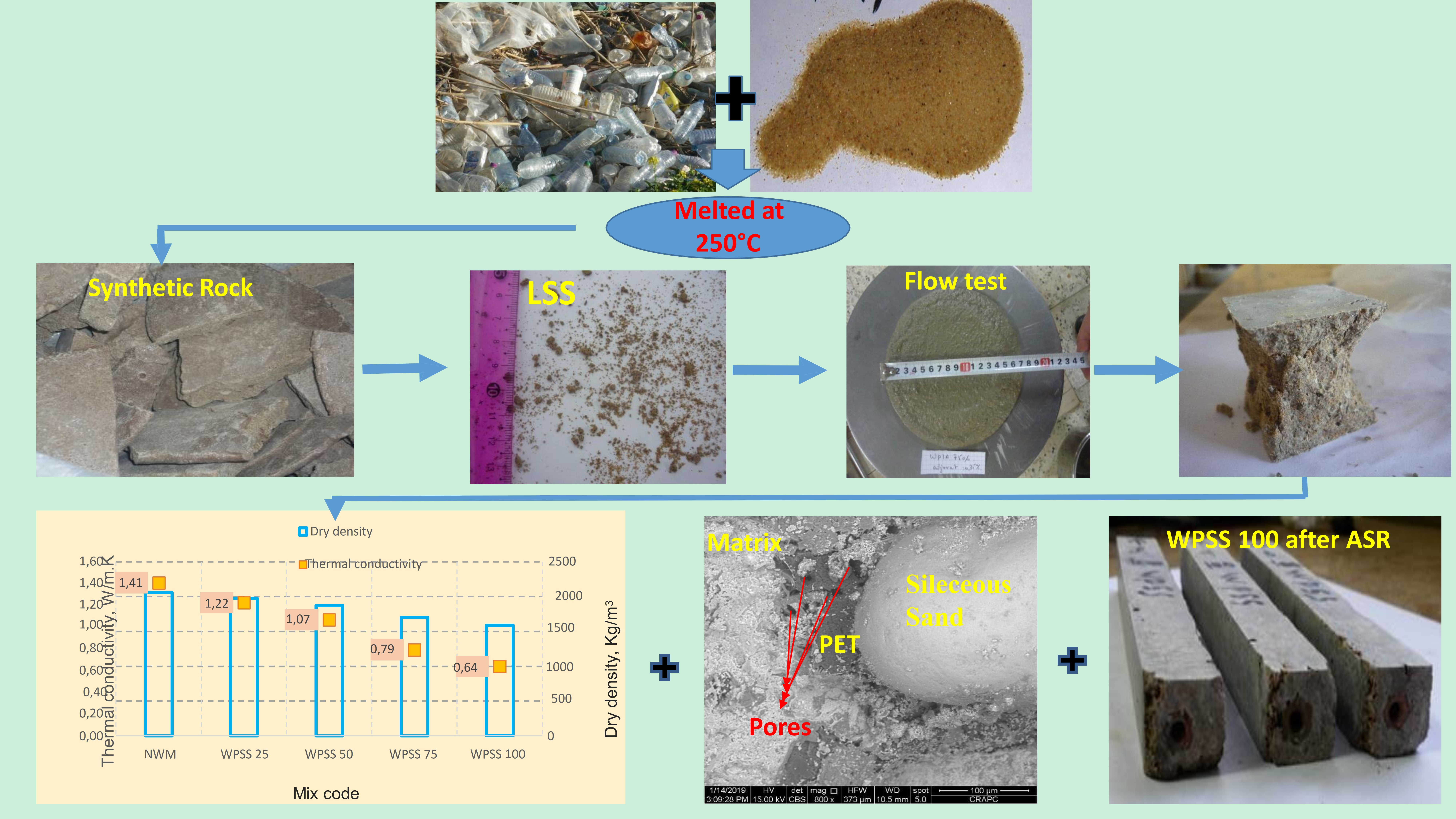

57].The synthesized hybrid material (LSS), used in this study, containing silica sand in a flexible matrix and originating from PET bottle waste, may have promising properties. In order to address the lack of research on the possibility of using plastic waste-based synthesized aggregates as substitutes for natural aggregates in cementitious materials, it was deemed appropriate to carry out an experimental program that consists in studying the effect of partial or total substitution of sand with these LSS aggregates on the physico-mechanical behavior and thermal properties of WPSS composite mortars, on their ductility and adhesion, by examining the ITZ using a scanning electron microscope. The durability factors, such as porosity and alkali silica reaction (ASR), were investigated as well. The present work is therefore an approach that allows for the implementation of efficient waste management. The purpose is to reduce the use of natural resources, and hence contribute to creating an important circular economy loop.

2. Materials and Methods

CEM II 42.5 N cement from the LCO Cement Plant of LAFARGE Group, located in the small town of OGGAZ in the Wilaya (Province) of Mascara (northwestern Algeria) is used in this study. This cement has a fineness of 4500 cm

2/g and an absolute density of 3.09 g/cm

3. The average compressive strength was found equal to 22 MPa at 2 days and 48 MPa at 28 days. Its chemical compositions are presented in

Table 1, while the mineralogical composition of its clinker is given in

Table 2.

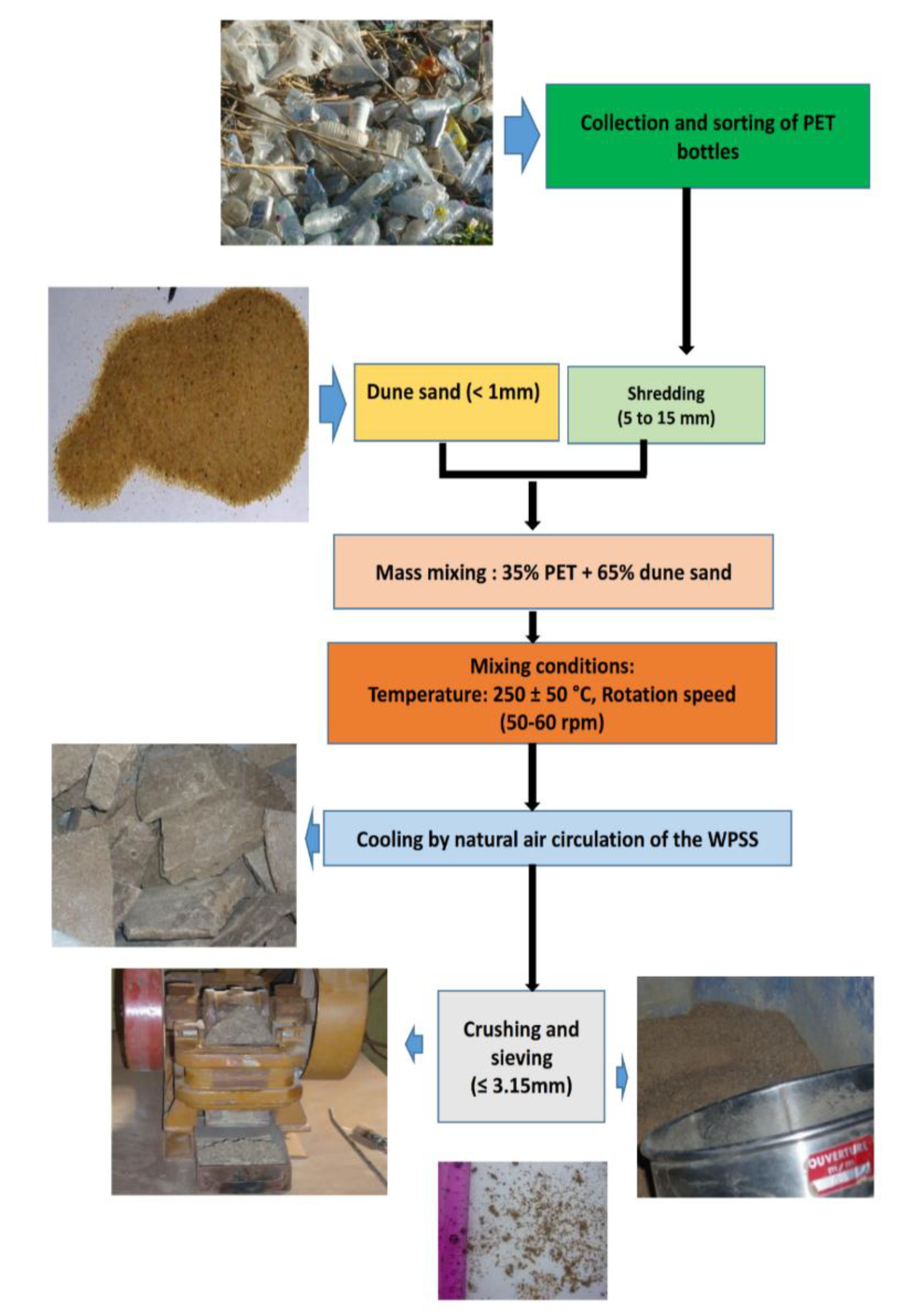

In this work, a composite containing LSS aggregates based on PET plastic waste and silica sand was thermally synthesized according to the flowchart drawn in

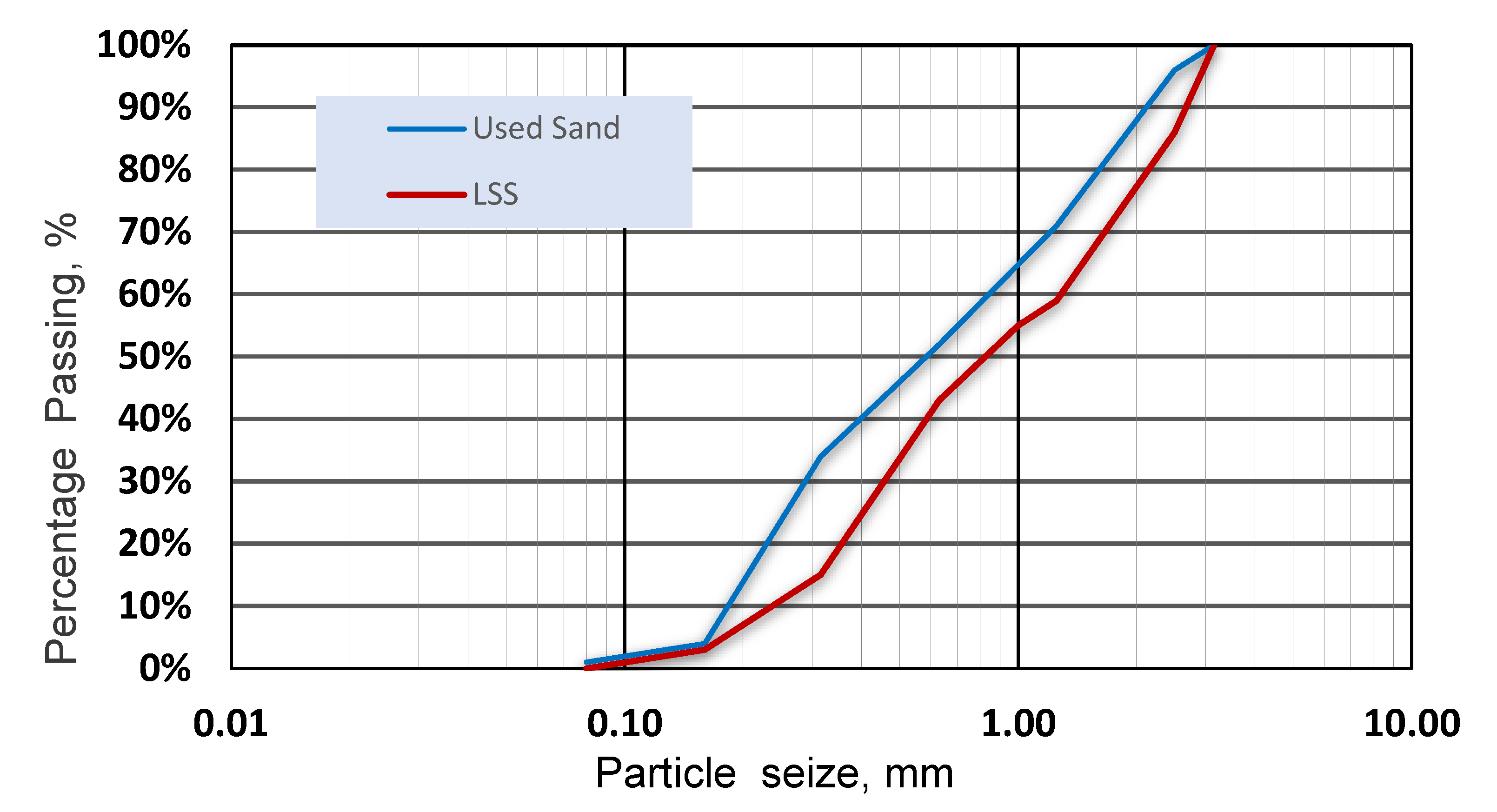

Figure 1. Next, The synthetic rocks were crushed, and then sieved to obtain different granular fractions, as depicted in the same Figure. The LSS aggregate fraction with size ≤ 3.15 mm was used in this study. It should be noted that silico-calcareous sand with a fraction smaller than 3.15 mm was also used. The chemical composition of the two sands, the particle size of LSS and that of the sand used, as well as their physical characteristics are summarized in

Table 1,

Figure 2, and

Table 3, respectively. It is worth noting that the WPSS composite mortars were developed according to the standard EN 196-1 [

58].The sand used was then replaced by the synthesized LSS aggregates, with volume percentages equal to 25, 50, 75 and 100%, as shown in

Table 4. For all formulations, the water-to-cement (W/C) ratio was set at 0.5. In addition, the superplasticizer SUPERIOR 9 WG, with a density of 1.10 and a dry extract of 33%, was added in order to achieve an almost homogeneous consistency.

Furthermore, prismatic molds of dimensions (4x4x16 cm³) were cast and then mechanically compacted using an electric shock table [

58]. This step was intended to investigate the properties of the samples in the fresh state. The molds were then covered with a plastic film and stored in laboratory conditions. Afterwards, these samples were unmolded after 24 hours, and then kept in a lime-saturated water environment at temperature T = (20 ± 2) °C and relative humidity RH = 100%, until the moment of testing.

The mechanical strengths of mortars were determined at 7, 28 and 90 days, according to Standard NF EN 196-1[

58]. It is worth mentioning that the loading rate was (50 ± 10) N/s for the flexural strength, and (2400 ± 200) N/s for the compressive strength.

Furthermore, the thermal properties of the WPSS composites were measured according to Standard ASTM D5334 [

59], while the ultrasonic tests were performed in accordance with the recommendations of Standard ASTM C597 [

60]. Additionally, their dynamic modulus of elasticity was calculated according to the methods that were developed by Malešev et al. and Gupta et al [24, 61].

Likewise, the QUANTA 250 FEI scanning electron microscope was employed for the microscopic analysis of our composite mortars.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Density in the Fresh and Hardened State

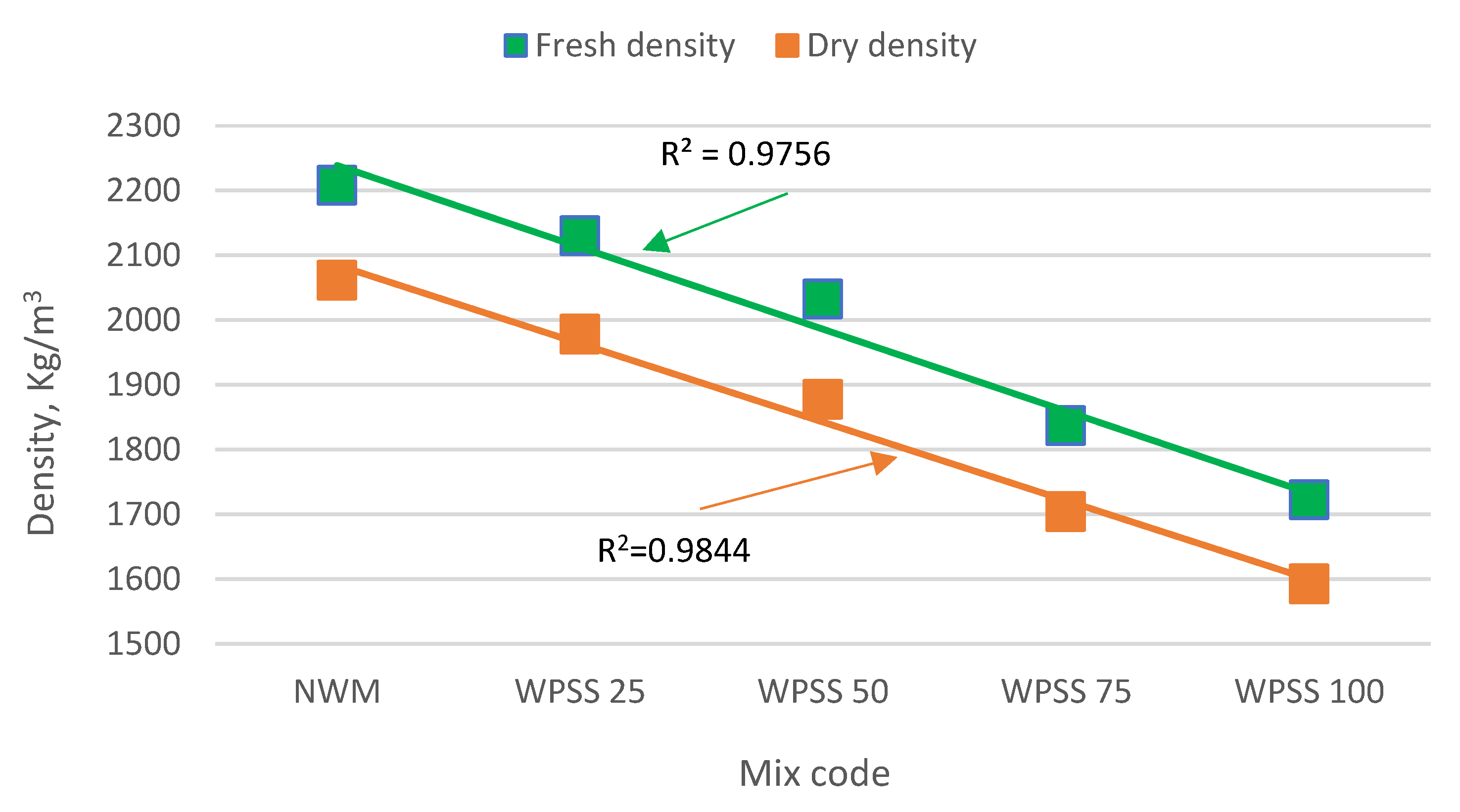

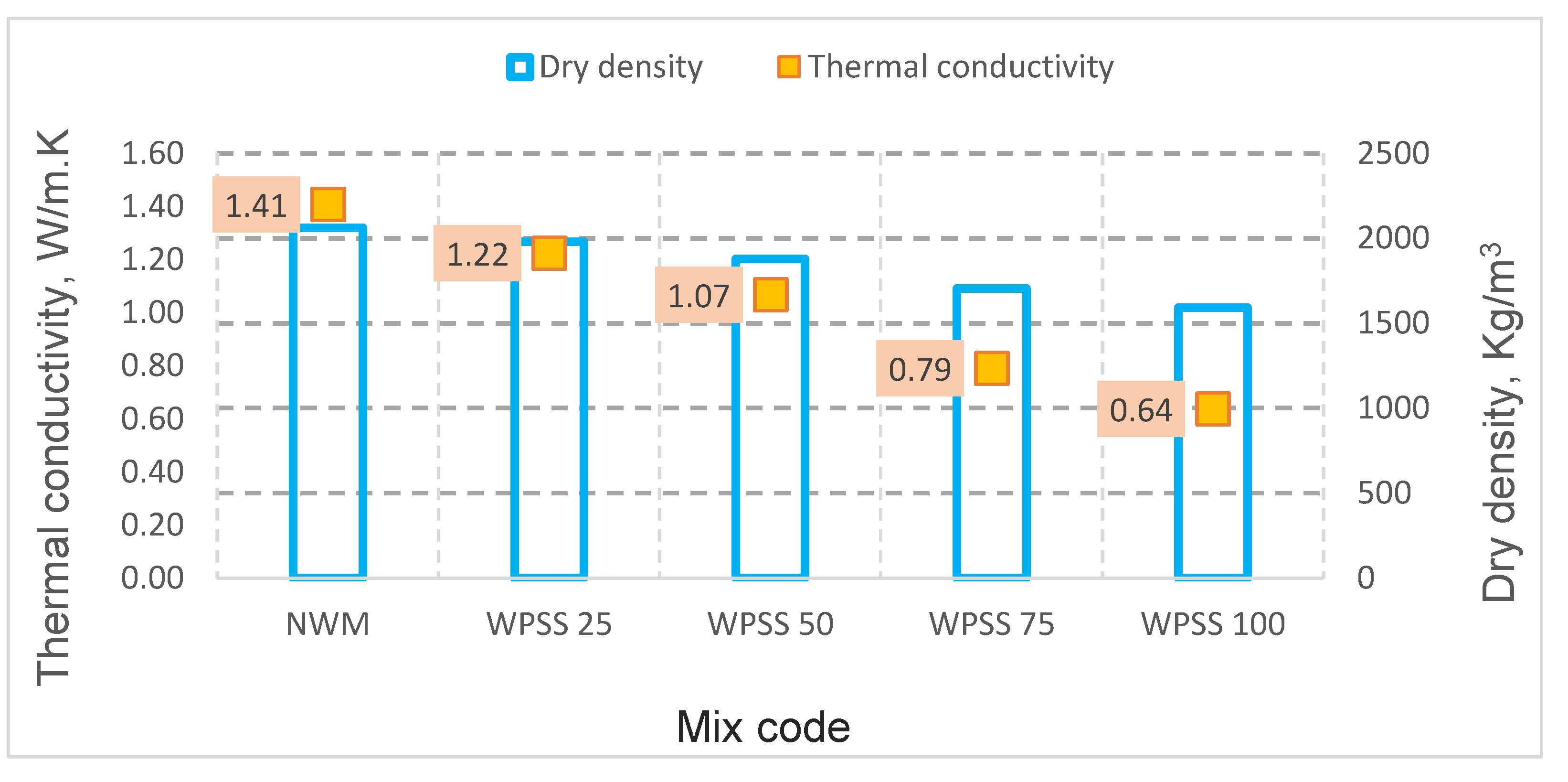

Figure 3 and

Figure 7 show, respectively, the effects of synthesized lightweight aggregates (LSA) on the fresh and hardened densities of composite mortars. It is easily noticed that the fresh density decreased proportionally to the rate of aggregate addition. This decrease was 22% for WPSS100 compared to that of natural witness mortar (NWM).

The above results are consistent with those reported by Alqahtani et al. [

52] who found a very small difference, not more than 3%, between the fresh density of LAC (1935 kg/m

3) and that of RP2F1C100 (1987 kg/m

3). This difference in density helps to reduce the proper weight of the structure during the construction period.

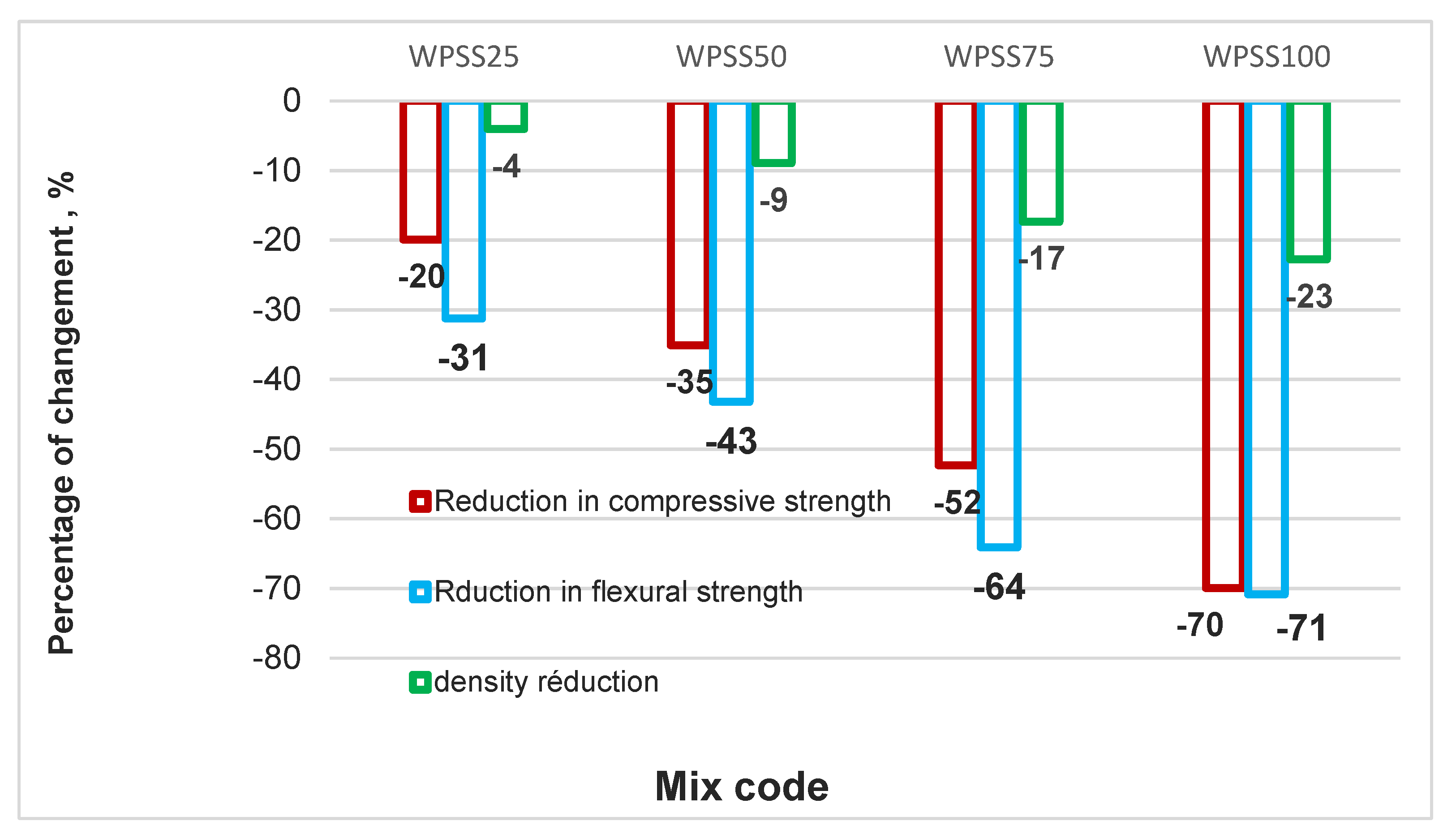

Likewise, a gradual reduction in the hardened density of WPSS composites was also noticed. Indeed,

Figure 3 clearly shows that at 28 days, drops of 4, 9, 17 and 23% were recorded, respectively, for WPSS25, WPSS50, WPSS75 and WPSS100, in comparison with NWM. It should be noted that, in this study, the density of WPSS100 is 1592 Kg/m

3 because of the low density of LSS (1.68 g/cm

3) compared to that of natural sand (2.630 g/cm

3). It was also found that the densities of the composites with the replacement percentages 75 and 100% meet well the classification criteria of lightweight aggregate concrete as required by the ACI 213R Guide [

7].These results are consistent with those found by [62, 63].

Furthermore, Gouasmi et al. [

64] found out that the densities of composite mortars tend to decrease as the WPLA replacement rate increases, which means that the resulting modified mortar is lighter. The density ranges from 2090 to 2420 kg/m

3, which corresponds to a reduction between 3% and 16% when compared to that of the control mortar. In this regard, Alqahtani et al. [

63] suggested that lightweight composite concrete can be produced with a replacement level of up to 100% as this can help to reduce the size of the elements used in building and consequently diminish their manufacturing costs.

Moreover,

Figure 3 shows the existence of a good correlation between the addition rate and density, with a coefficient of determination R

2 = 0.9756 for the fresh mortar density, and R

2 = 0.9844 for the hardened mortar density.

3.2. Compressive Strength

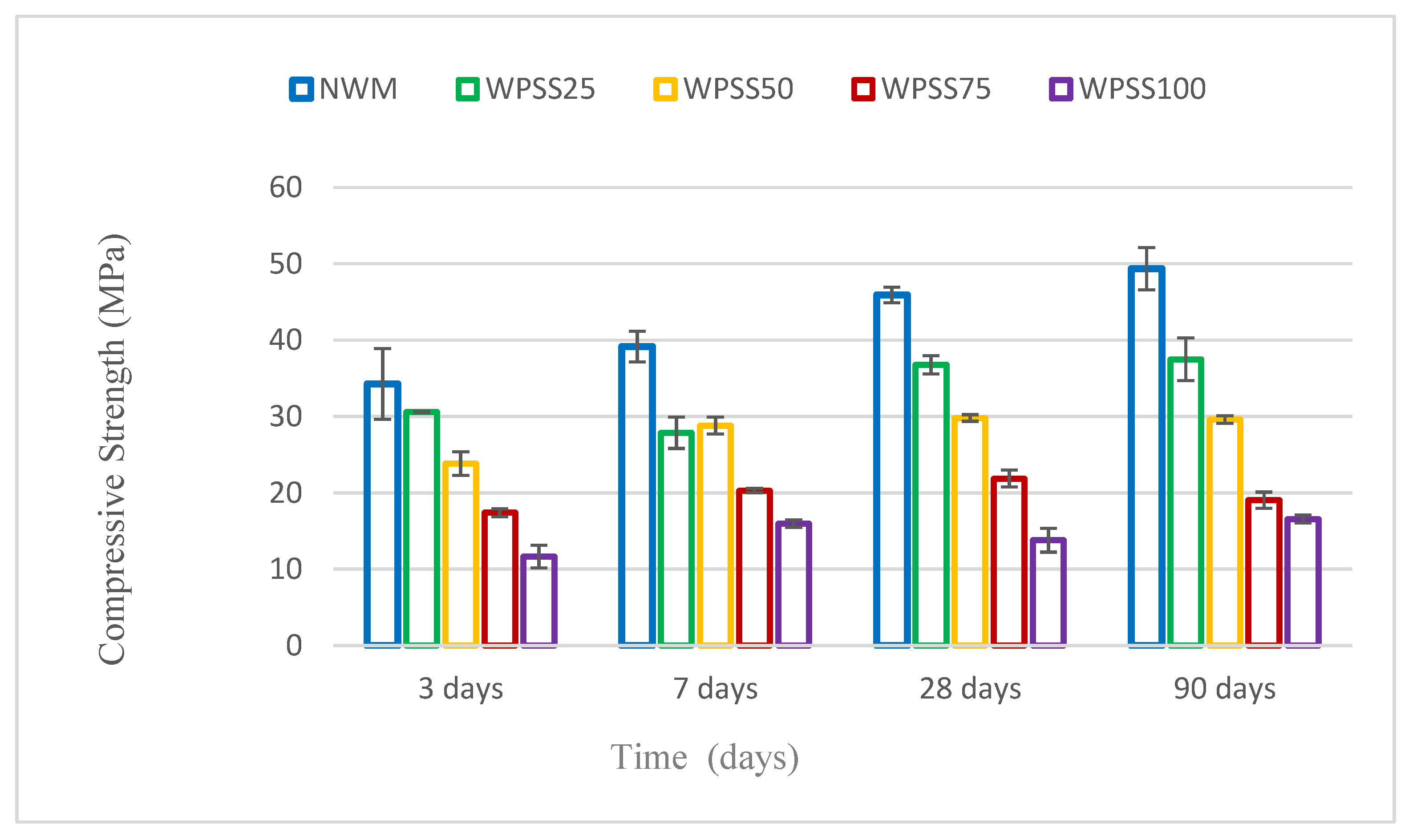

Figure 4 and

Figure 7 depict the compressive strength values of composite mortars, at different time points. It is observed that the compressive strength of all the mixtures increases with age (7, 28, and 90 days). The low densities of the different composite mortars (

Figure 1) indicate that these mortars have different compressive strengths.

It was also revealed that the addition of synthesized aggregates leads to a decrease in strength. In addition, the strength differences between the prepared composite mortars and the control mortar indicate that these different mortars exhibit different performances. These performance differences were found around 20, 35, 52 and 70% for composites WPSS25, WPSS50, WPSS75 and WPSS100, respectively. These findings are consistent with those reported in other studies that were conducted on other types of composite aggregates, by Gouasmi et al. [

64], Alqahtani et al. [

63], Ennahal et al. [

54], Bouaziz et al. [

51] and Binici et al. [

46].

Indeed, Gouasmi et al. [

64] found that the compressive strength values, at 28 days, evolved negatively for all WPLA composite mortars compared to the unmodified mortar.

Similarly, Alqahtani et al. [

63] suggested that the smallest compressive strength reduction was observed for RP2F3A concrete, which was 40% less than that of conventional concrete containing lightweight aggregates (LWA). In contrast, the maximum compressive strength reduction of 53% was observed for RP1F2A concrete as compared to that of conventional concrete. The authors then confirmed that the RP1F3C0.5 and RP2F3C0.5 formulations met well the strength requirements of Standard ASTM C330 (greater than 17 MPa).

With regard to Ennahal et al.[

54], they compared the compressive strength of the control mortar with those of the MSPE1-30% mortars. They then found out that the compressive strength of the MSPE1-30% was 59.77% lower than that of the control mortar, while the strength of the MSPE2-30% was 52.97% lower. These results show that the MSPE2-30% mortar is more resistant than the MSPE1-30% mortar by 14.46%. The authors then concluded that the compressive strength difference between the MSPE1-30% and MSPE2-30% mortars was due to the differences in the cement and aggregates proportions used.

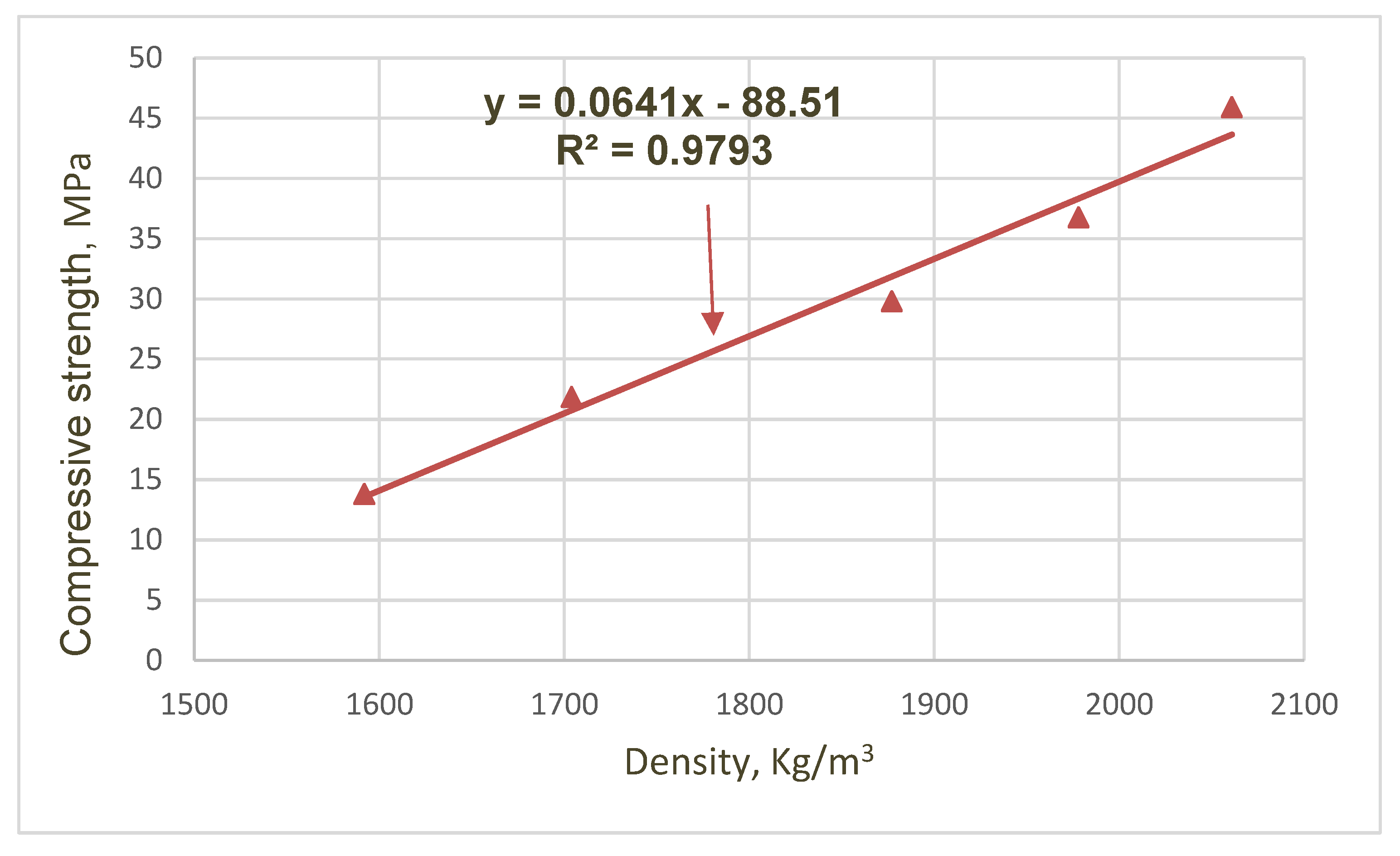

Figure 5 shows a good correlation between the hardened concrete density and the compressive strength at 28 days, with a coefficient of determination R

2 = 0.9793.

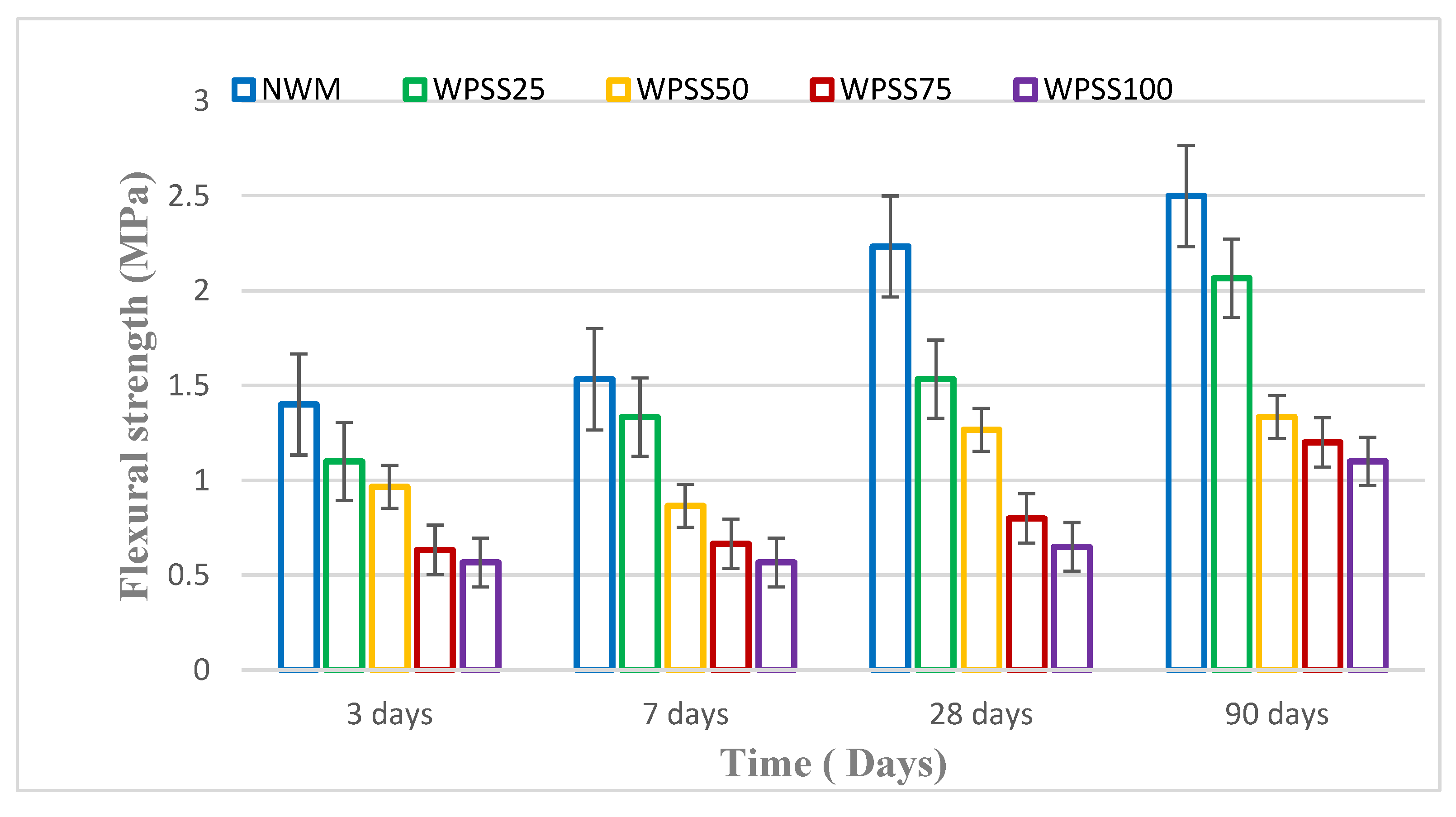

3.3. Flexural Strength

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 present the data relative to the flexural strength measurements. They indicate a systematic flexural strength reduction as the synthesized PET-silica sand aggregate percentage increases. It was found that, this reduction, at 28 days, was 31, 43, 64 and 71% for composites WPSS25, WPSS50, WPSS75 and WPSS100, respectively, with respect to that of NWM.

In this context, Gouasmi et al. [

64] noticed that, among all the composite mortars developed, WPLA25 presented the highest strength that was equal to 5.23 MPa. However, the flexural strength of WPLA0 was 4.81 MPa which is represents an 8% gain in flexural strength. They then justified this by the elastic nature and non-brittle characteristic of PET plastic aggregates under loading.

On the other hand, Alqahtani et al. [

63] found out that the flexural strength decreases when plastic-based composite aggregates are added. In addition, Ennahal et al.[

54] revealed that the flexural strength of MSPE2-30% mortar (mortar containing 30% polypropylene and polystyrene) was about 42.13% lower than that of the reference mortar due to the addition of aggregates in the composite mortars.

3.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis

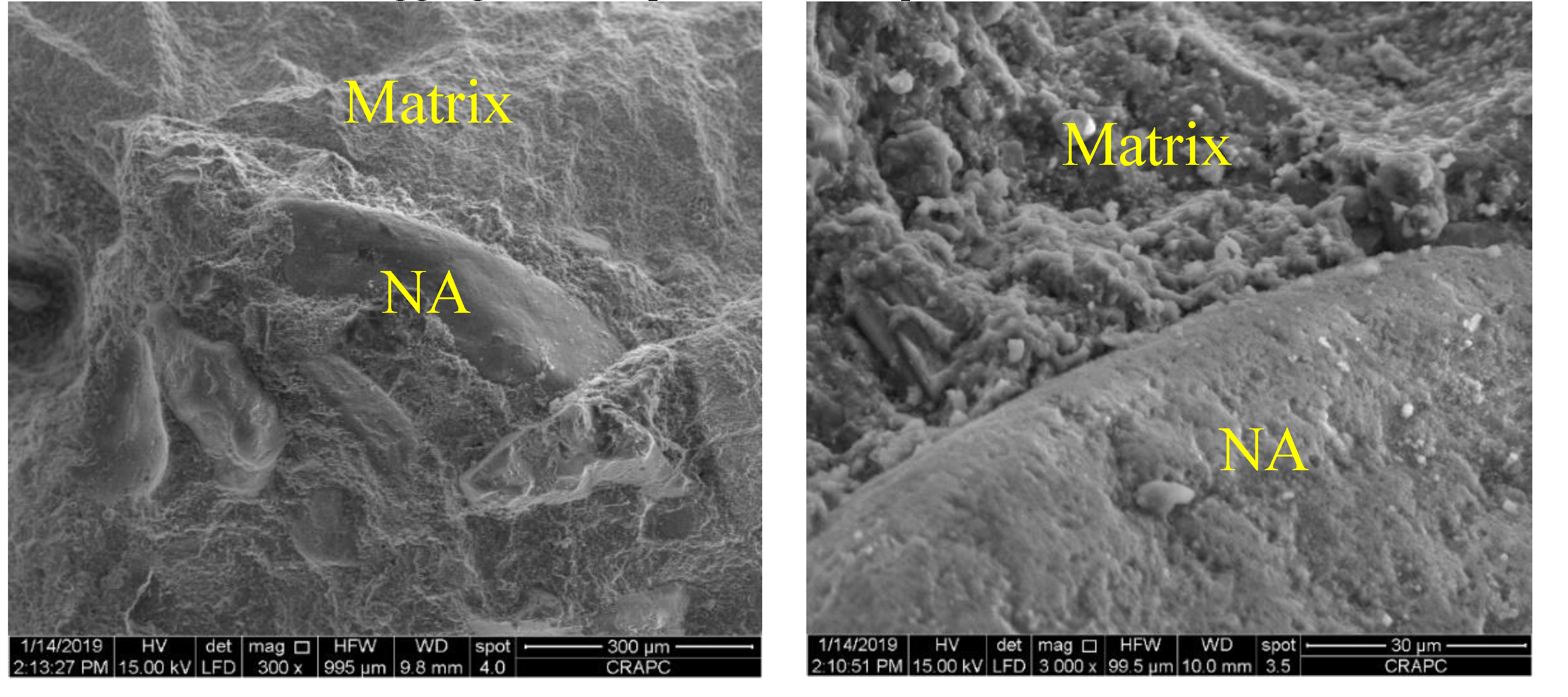

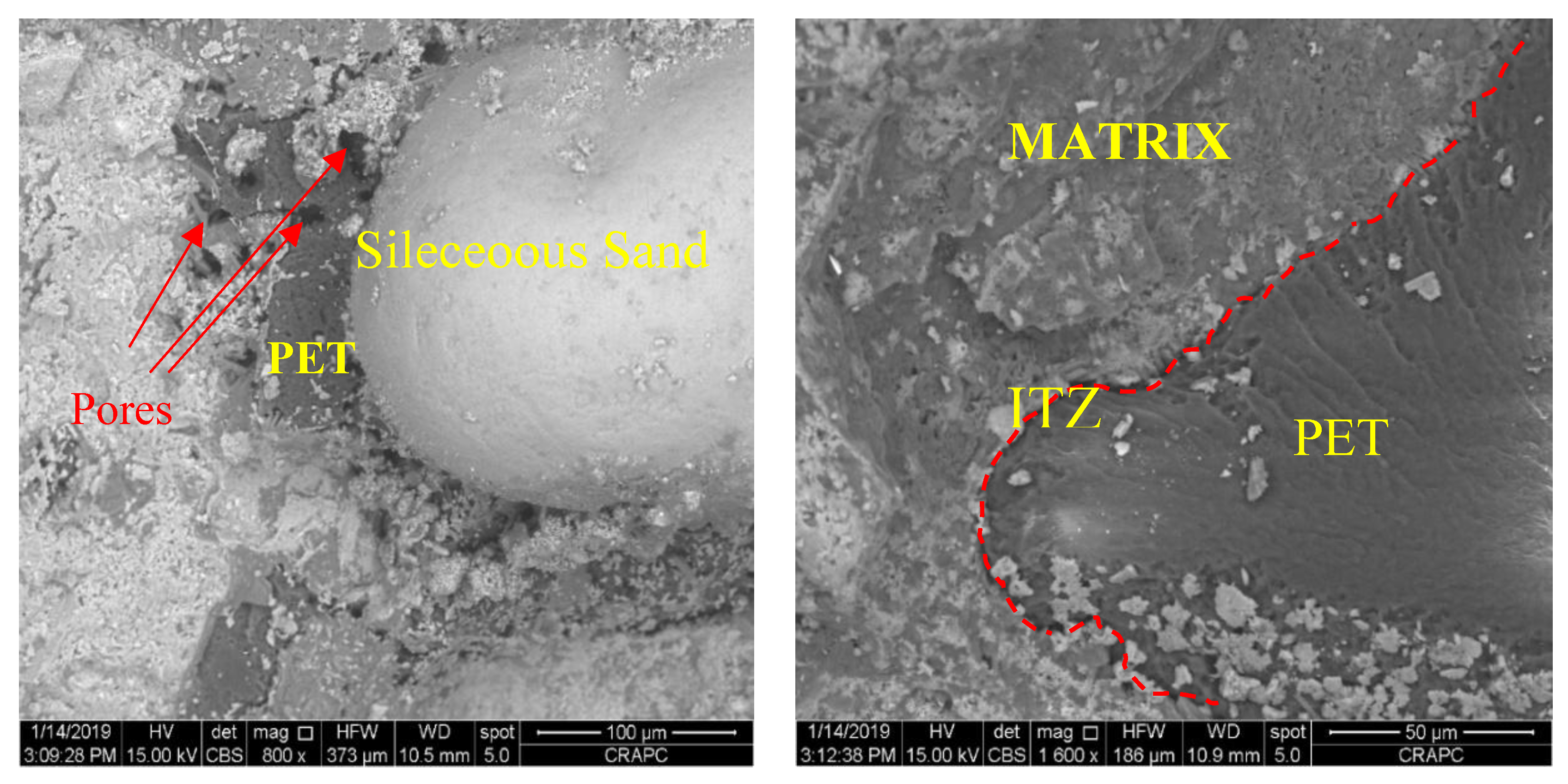

The SEM images, which are illustrated in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, clearly show the interface transition zone (ITZ) between the cement matrix and aggregates. A good adhesion was observed, on the one hand, between this matrix and natural aggregates and, on the other hand, between this same matrix and LSS aggregates. The findings are quite consistent with those reported in several other works [

51], [

50], [

47] and [

65].

Furthermore, Ge et al. [

65]indicated that the PET and sand particles were well bonded, and the ITZ was dense. Also, no microcracks or voids were detected. As for Gouasmi et al. [

66], they asserted that a perfect microstructural arrangement existed between PET aggregates and silica sand grains, which explains the strong adhesion between the composite aggregate and cement paste. Likewise, Ennahal et al. [

54] reported that sediment particles were well distributed in the thermoplastic matrix for both types of synthesized aggregates. There was a good interaction between the matrix and these particles.

In contrast, Choi et al. [

47] found out that the ITZ between waste plastic lightweight aggregates (WPLAs) and cement paste tended to get larger than that of the natural aggregate. This was certainly due to the fact that WPLA aggregates are spherical in shape with a smooth surface.

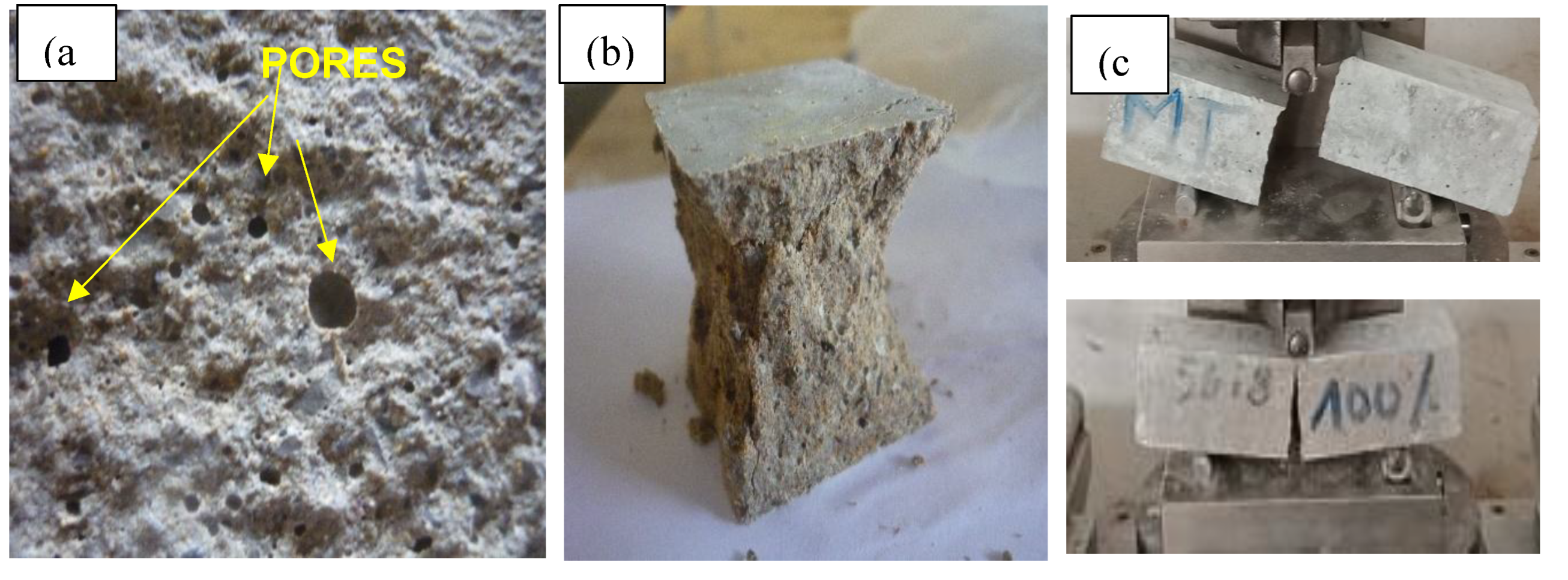

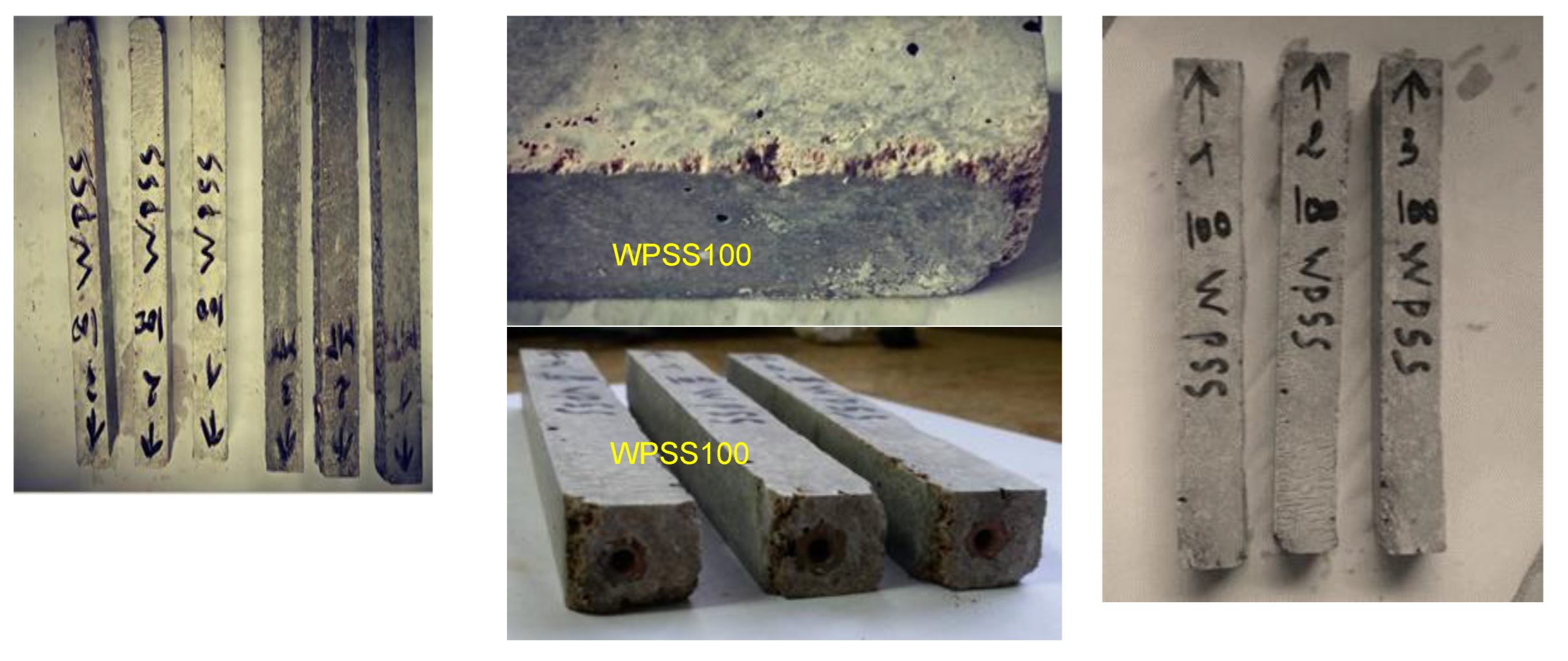

Figure 10 shows the condition of the samples after the compression and bending tests. After the tests, WPSS100 composite mortars exhibited slightly higher ductility than NWM, meaning that the mortar becomes slightly more elastic and less rigid.

The above findings agree well with those reported by Saikia and Brito [

67], Marzouk et al. [

10] and Alqahtani et al. [

63] who found out that the crack propagation range was extended due to the presence of recycled plastic particles. However, despite this, it can be said that the waste that has not undergone any heat treatment has a better ductility than that of the synthesized aggregates. This is certainly due to the fibrous aspect of the untreated plastics.

Likewise, Jayasinghe et al. [

42] used the scanning electron microscopy technique to show that the PET plastic mixture presents a homogeneous crystallization when mixed with quarry dust, which is not the case for mixtures incorporating HDPE and PP.

As for Badache et al. [

27], they obtained better results. They then found out that this was due to the shape and rigidity of the HDPE aggregates which do not have the same characteristics as natural aggregates, and particularly those having a fiber shape. This allows, therefore, saying that the wastes that have not undergone heat treatment possess a better ductility compared to that of synthesized aggregates.

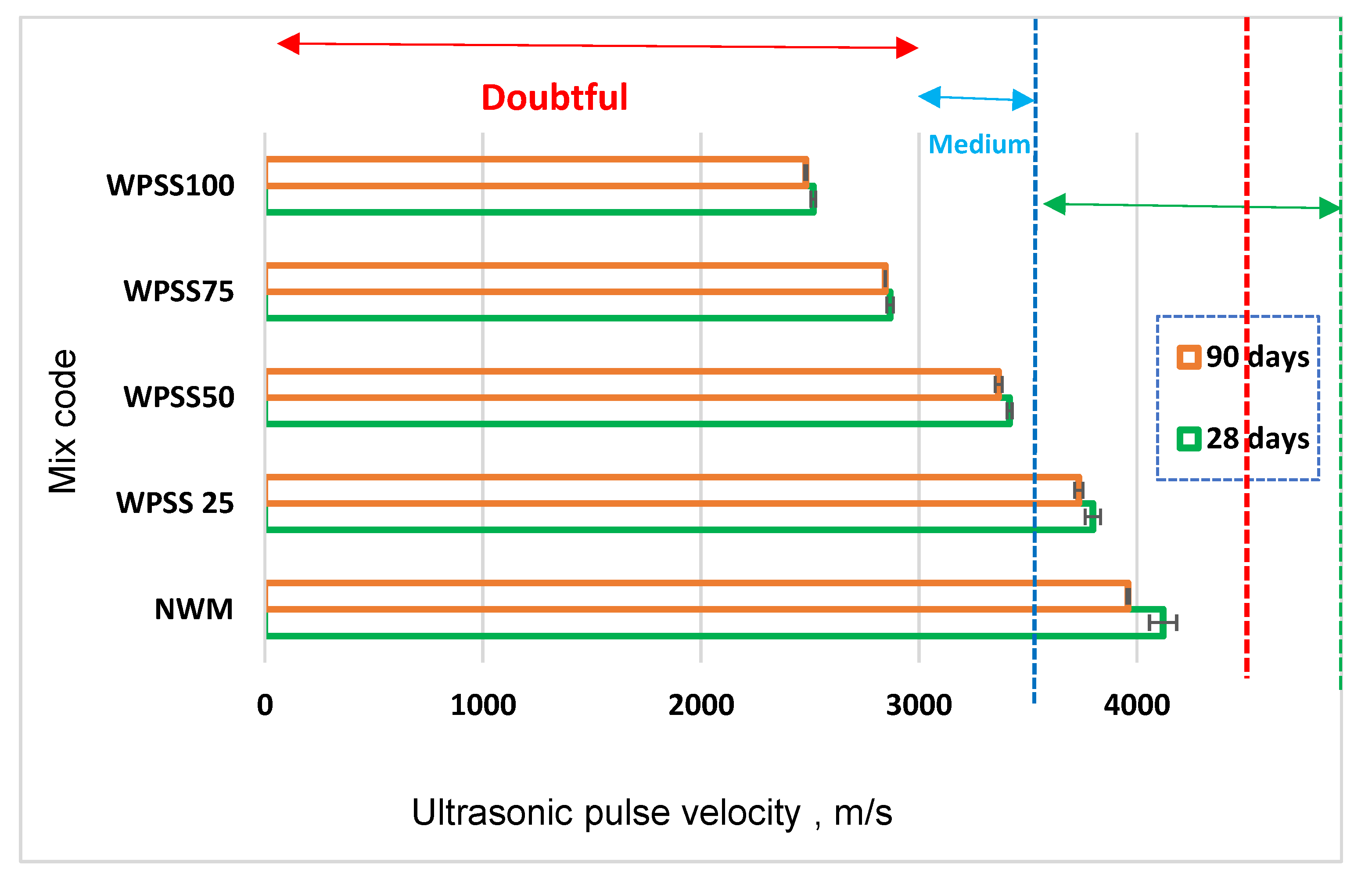

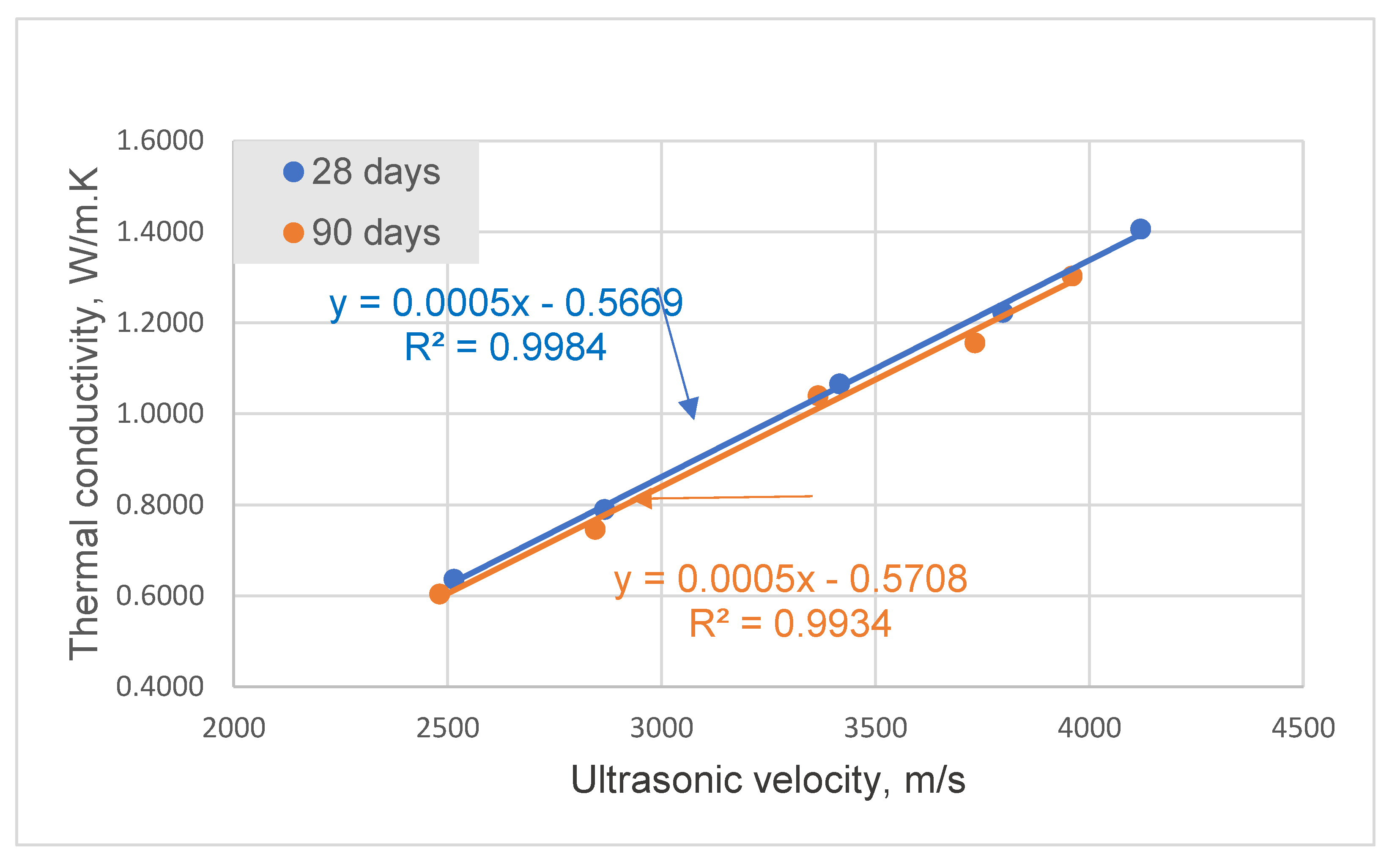

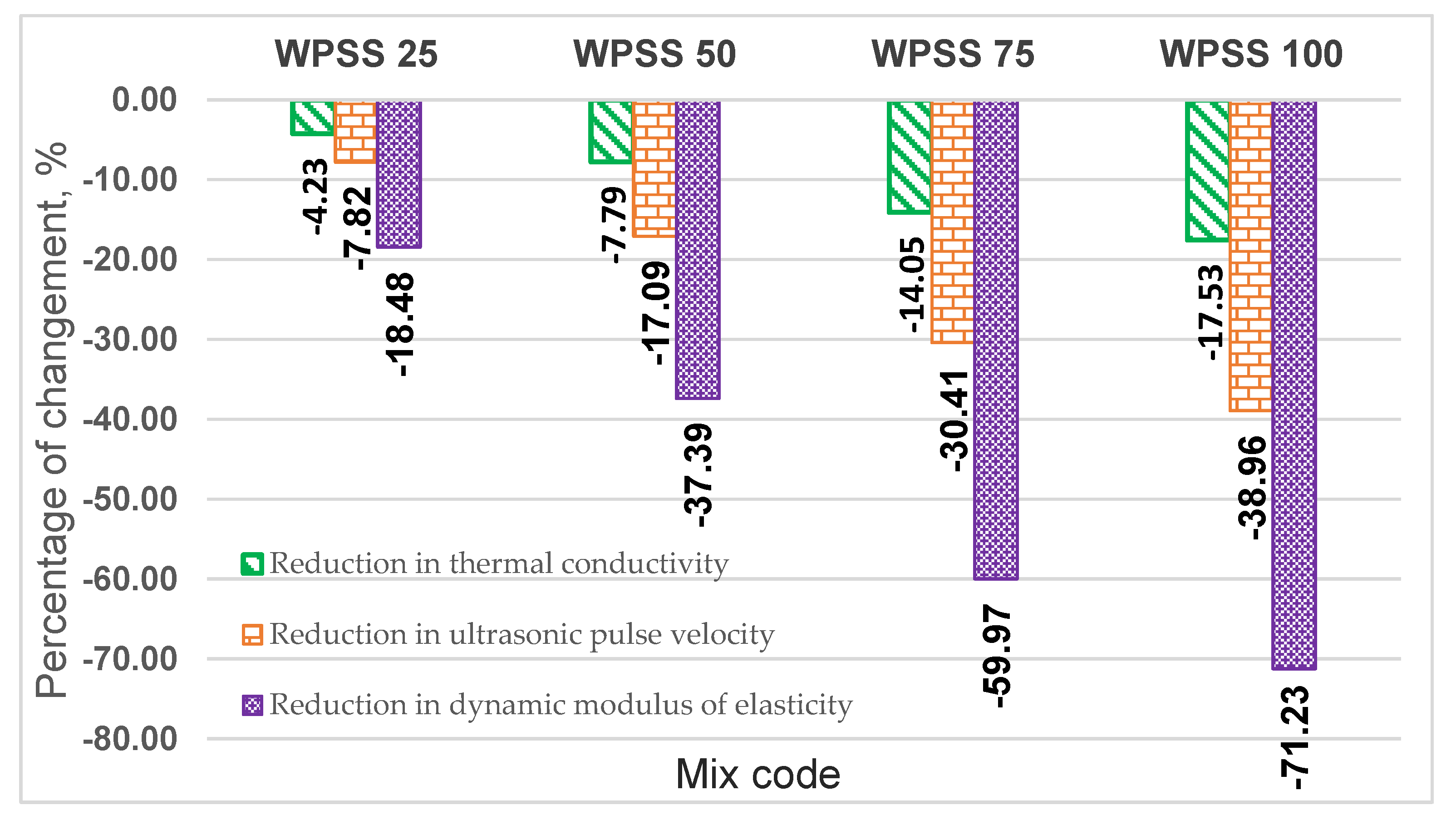

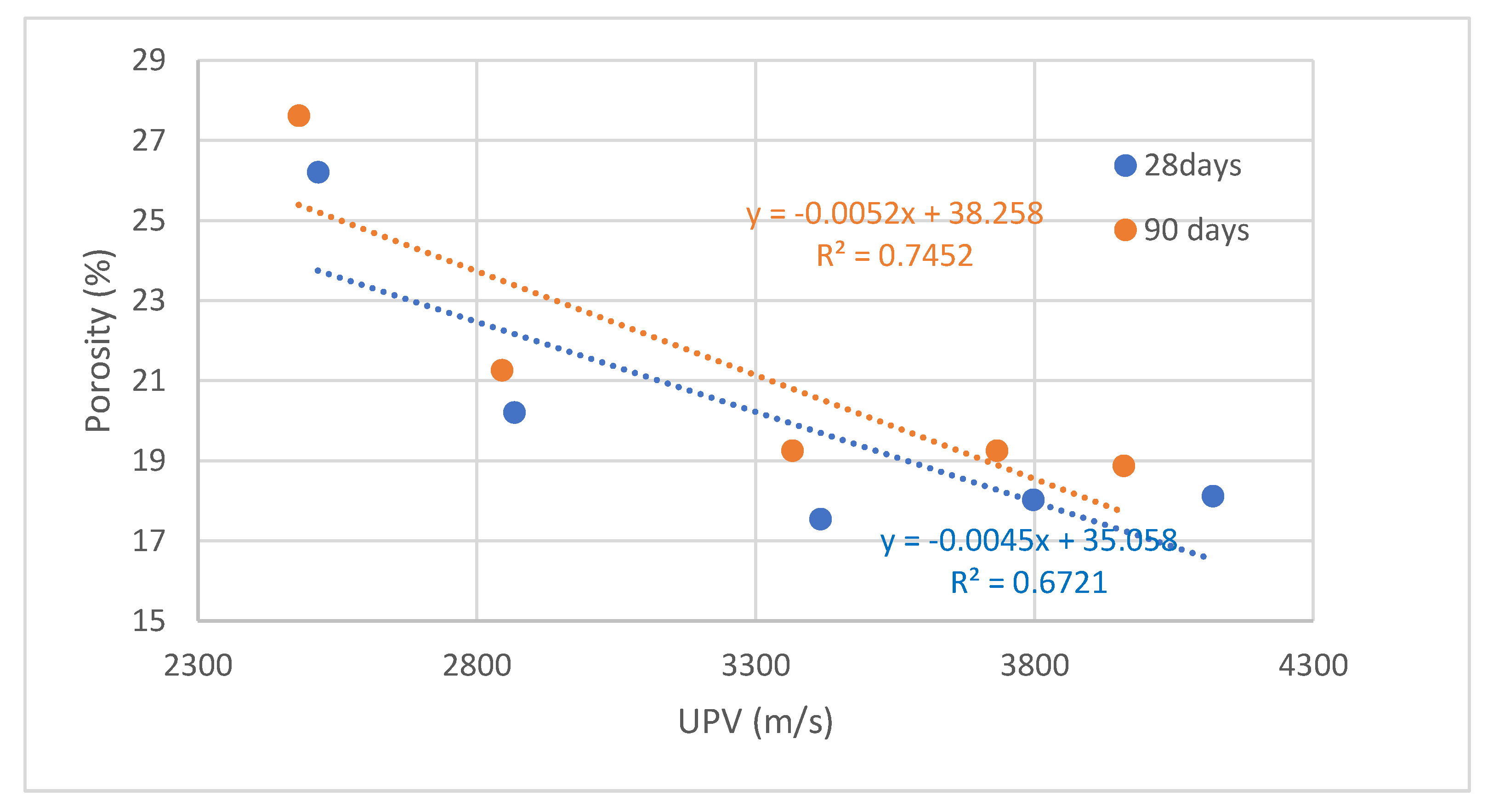

3.4. Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity (UPV) Test

The UPV test results of the composites under study, at 28 days and 90 days, are presented in

Figure 11.

It was shown that the ultrasonic pulse velocity in a material depends on its density, moisture content, and elastic properties [

68]. It was also observed that, at 28 days, the UPV decreases by 8, 17, 30, and 39% for composites WPSS25, WPSS50, WPSS75, and WPSS100, respectively, compared to that of NWM.

Regarding Gouasmi et al. [

66], they found out that the UPV value decreases as the WPLA content in the composite increases. They indeed indicated that the UPV decreases by 3.5%, 9%, 14%, and 23% for composites WPLA25, WPLA50, WPLA75, and WPLA100, respectively, as compared to that of WPLA0 (control mortar). They then concluded that this was certainly due to the discontinuous presence of air voids within the cement matrix since the ultrasonic wave should bypass these voids to propagate.

Similar results were obtained for composites based on recycled lightweight aggregates by Azhdarpour et al. [

69], Senhadji et al. [

21] and Akçaözoğlu et al. [

70].

Further, Azhdarpour et al. [

69] and Senhadji et al. [

21]reported that when a sound pulse passes through various materials, i.e. plastic aggregates, cement matrix, and pores, it is only partially transmitted, implying that the pulse velocity decreases. It was also revealed that the UPV depends on the volumetric concentration of the different constituents of the material. When plastic aggregates replace natural aggregates, plastic particles with a sheet-like structure act as a refraction barrier for ultrasonic pulses. It is important to highlight that Standard IS 13311-1-92 [

71] classifies the quality of composite mortars according to their UPV values.

Figure 14 shows that the compressive strength values of reference sample (NWM) and composite WPSS25 may be considered as acceptable. On the other hand, the quality of WPSS50 and WPSS75 specimens is considered to be fair and quite poor, respectively.

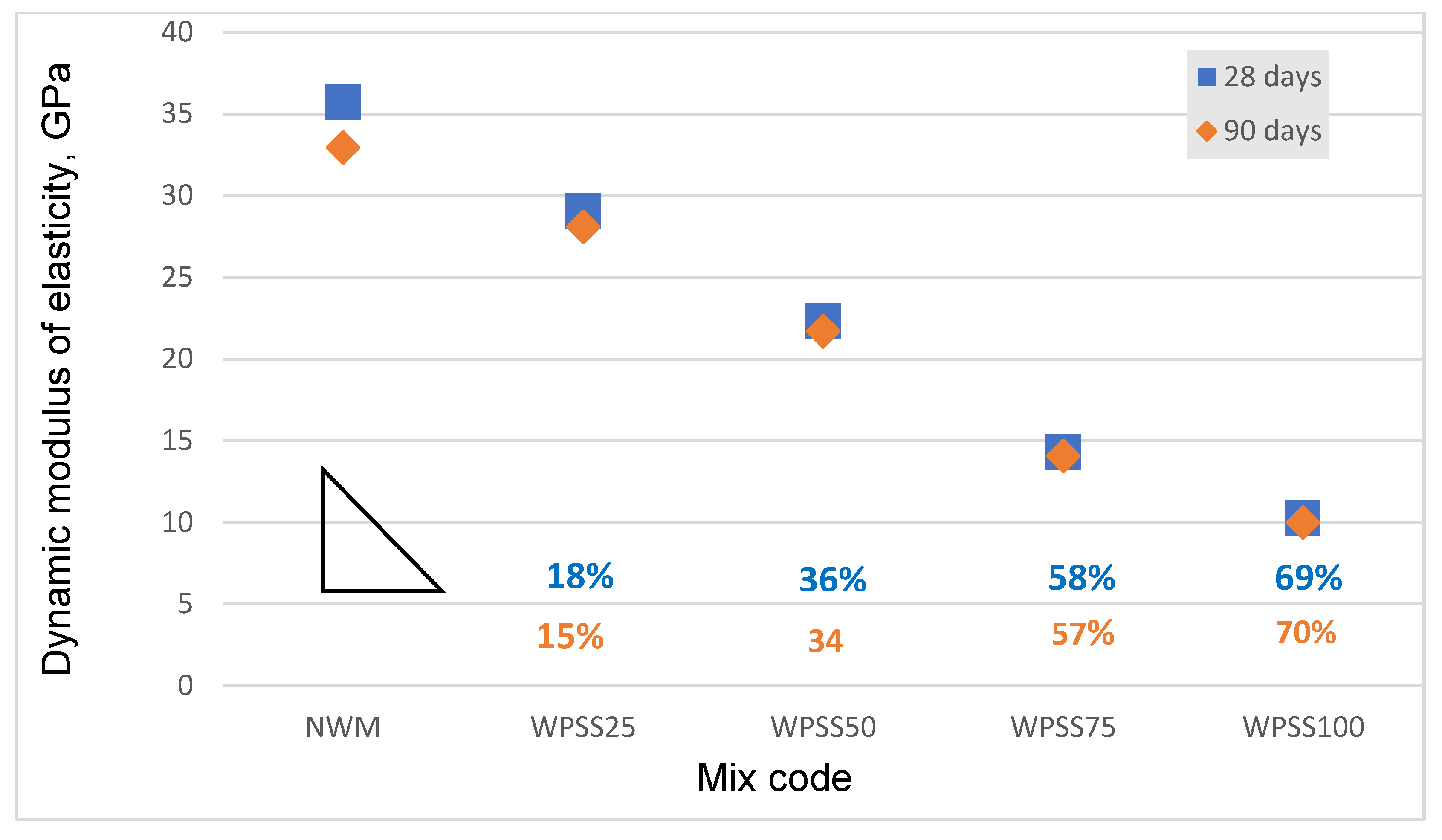

3.5. Dynamic Modulus of Elasticity

Figure 12 depicts the dynamic modulus of elasticity (Ed) values which decrease as the LSS aggregate content rises. At 28 days, Ed drops by 18%, 36%, 58% and 69% for the mixtures containing 25%, 50%, 75% and 100% of LSS, respectively. This can be attributed, firstly, to the weak bonding between the cement matrix and plastic particles of the different composites [

72], [

73] and [

18]and, secondly, to the low elastic modulus values of PET (E

PET = 2.7 GPa) [

74], [

66].

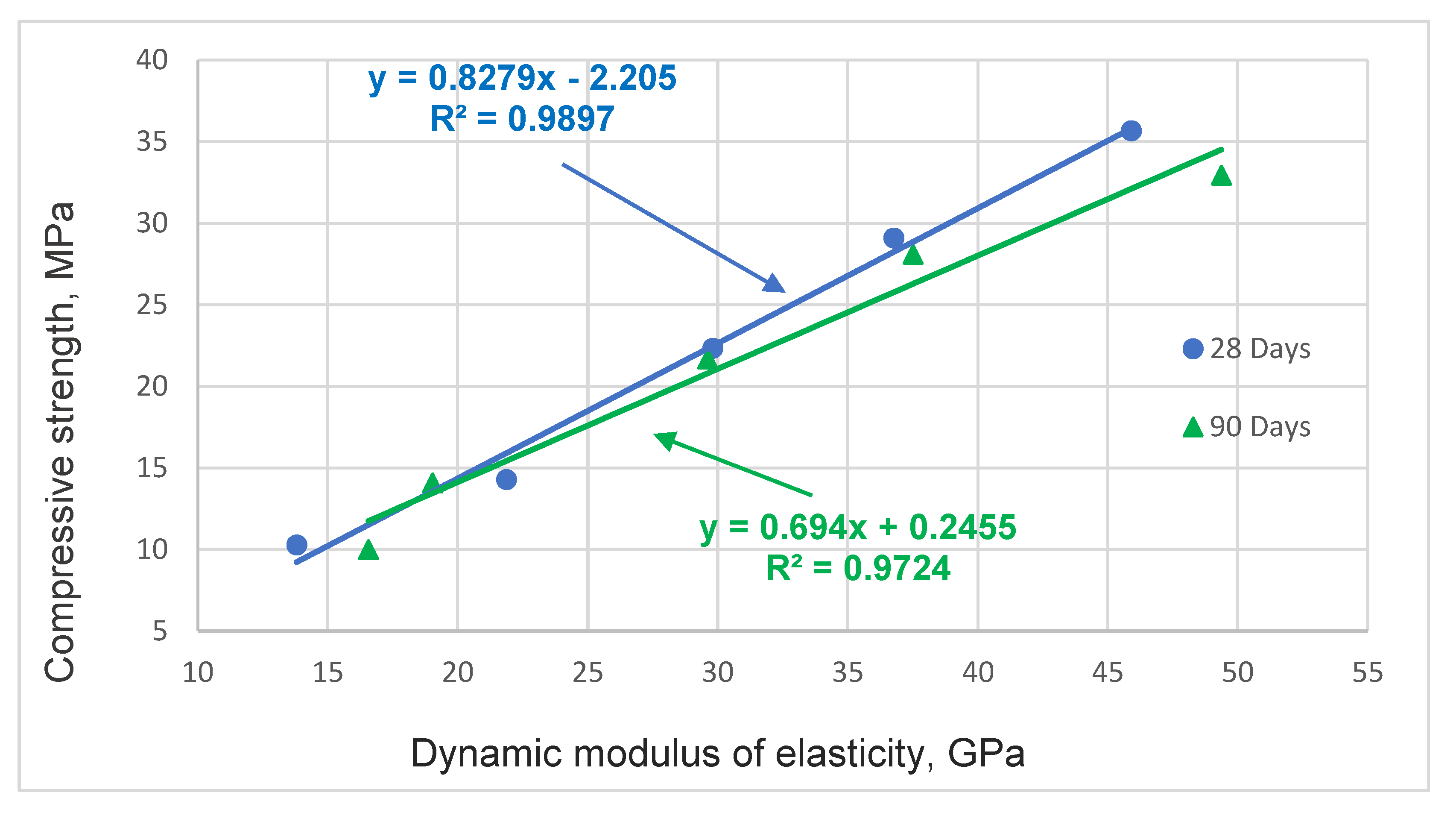

In addition,

Figure 13 shows that the correlation between the compressive strength and Ed is quite good. It was indeed observed that the coefficients of determination for the correlations, at 28 days and 90 days, were R

2 = 0.9897 and R

2 = 0.9724, respectively.

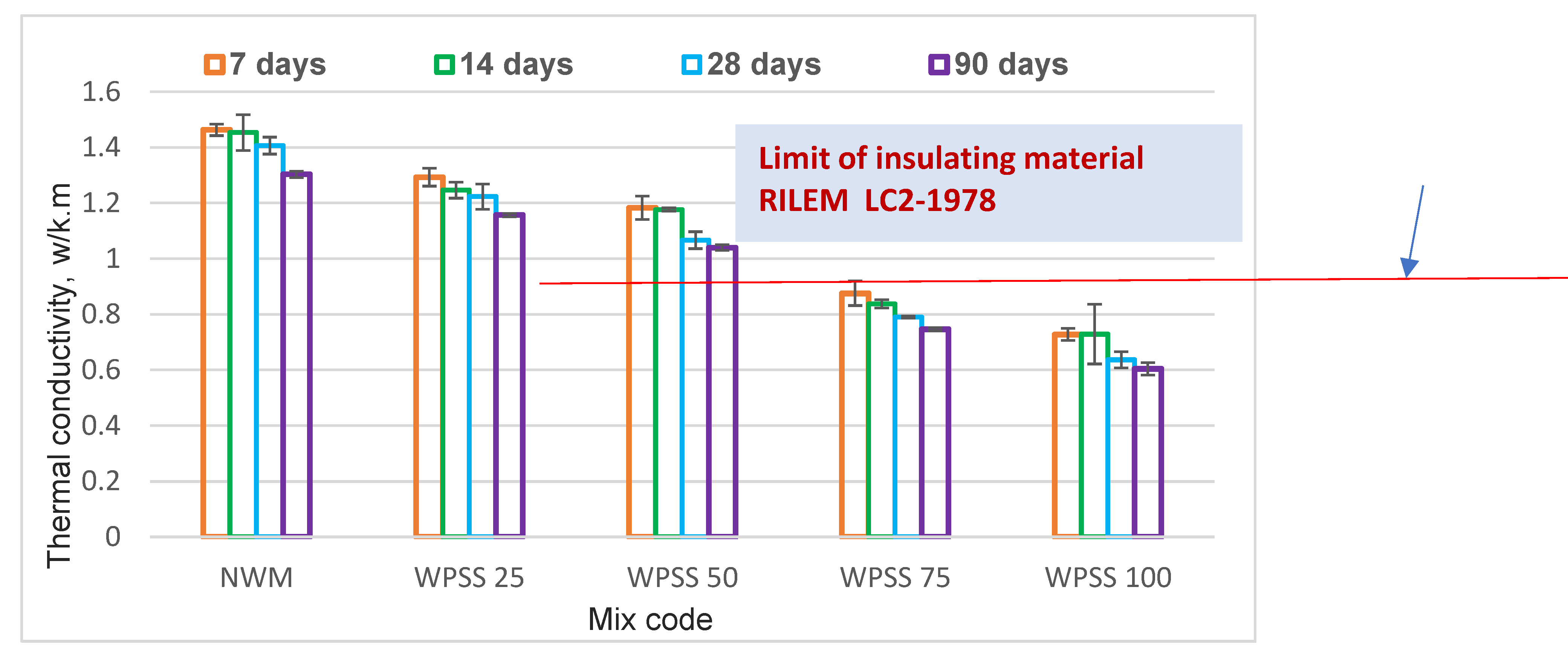

3.6. Thermal Properties

3.6.1. Thermal Conductivity of WPSS Composite Mortars

The thermal conductivity λ of the samples, measured at different time points, is depicted in

Figure 14. At 90 days, the value of λ for control mortar (NWM) is 1.30 W/m.K, while for WPSS100, it is smaller, around 0.60 W/m.K. Moreover, the incorporation of LSS aggregates into the composites resulted in a decrease in the thermal conductivity of the different samples.

It was actually observed that increasing the proportions of LSS (λ = 0.589 W/m.K) that is based on PET (λ = 0.15 W/m.K) as a replacement for natural sand (λ silica = 3.59W/m.K [

75], with λ of natural aggregate = 2.0 W/m.K [

76]) leads to a decrease in the conductivity of composite mortars.

The above findings have been confirmed by Boudenne [

77], Gouasmi et al.[

78], Hannawi et al.[

76], Erdogmus et al. and Akçaözoğlu et al. [56, 70].

Likewise, Alqahtani et al. [

79] reported that the thermal conductivity decrease in their composites was essentially due to the porous structure of the synthesized aggregates and also to the air trapped in voids. Moreover, Erdogmus et al. [

56] suggested that for inhomogeneous mixtures containing pores of different sizes, the distribution of these pores as well as the microcracks formed after the addition of plastic waste do have an impact on the thermal conductivity and porosity of the composites.

Since the thermal conductivity results of our WPSS75 and WPSS100 composites are lower than 0.75 W/m.K., as depicted in

Figure 15, then it may be said that their compressive strengths are greater than 3.5 MPa (Rc > 3.5 MPa). It is therefore possible to deduce that these composite mortars can be used as insulating materials, according to the functional classification of lightweight concretes by Rilem (1978) [

80].

Figure 15 indicates that the thermal conductivity decrease is directly related to the reduction in density. As for

Figure 16, it presents the different correlation coefficients (R

2 ≥ 99%). It actually shows that a good correlation exists between the thermal conductivity values and UPV values, for all WPSS composites. Similarly,

Figure 17 clearly shows the effect of LSS aggregates on the outcomes of the different non-destructive tests carried out on WPSS composites.

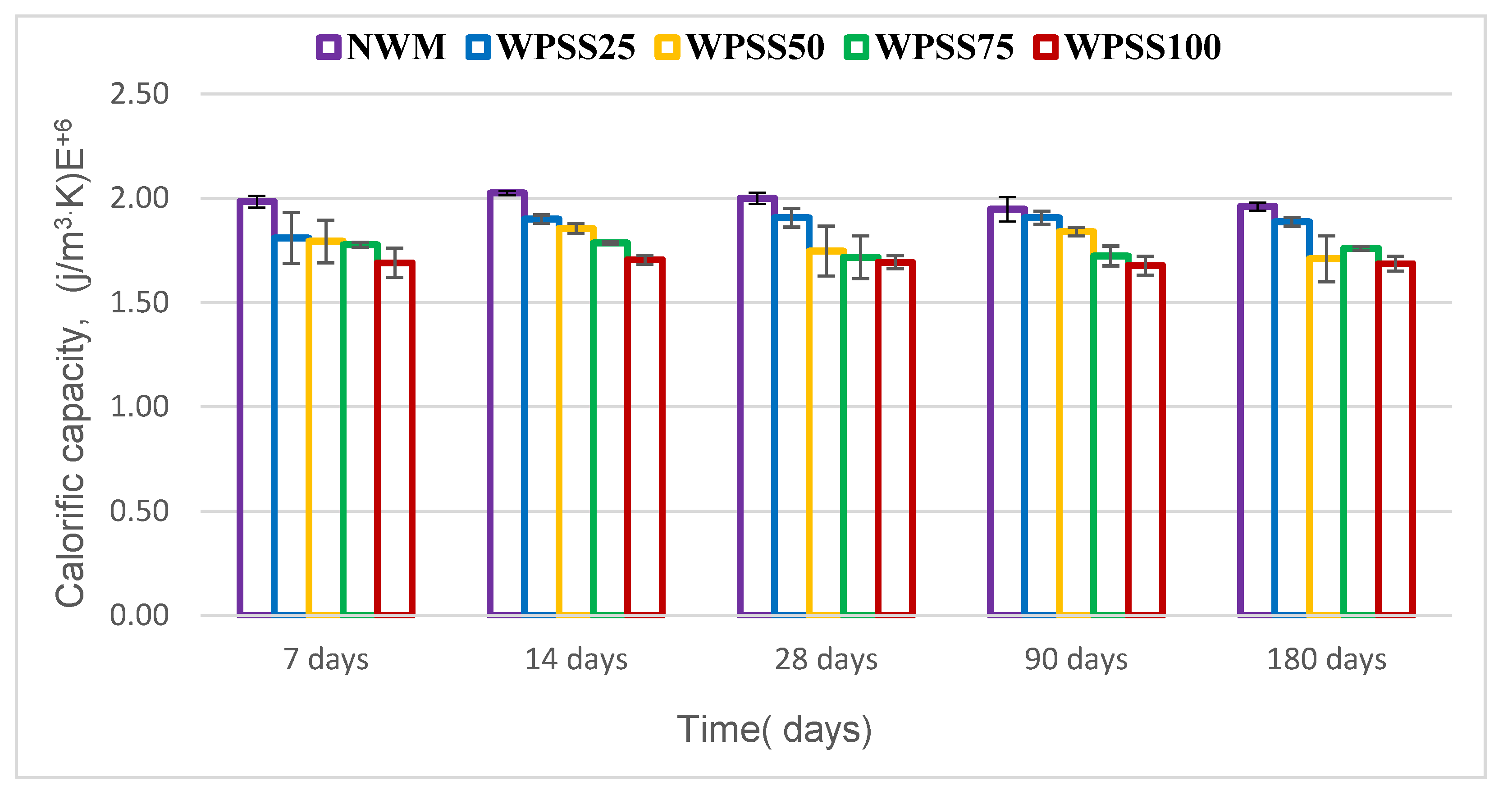

3.6.2. Heat Capacity

Figure 18 depicts the evolution of the heat capacity Cp as a function of time, at room temperature. One can easily see that as the LSS addition rate increases, the heat capacity decreases. Furthermore, it is also noticed that, over time, Cp varies slightly. Indeed, it is clearly indicated that at 180 days, the rate of Cp decrease went from 4% to 14%. It should also be mentioned that the heat capacity of NWM reached an average value of 1.96 J/m

3.K which is higher than that of mortar WPSS100 (1.69 J/m

3.K), which can be explained by the fact that the thermal properties of PET and conventional aggregates are different. In this context, Mounanga et al. [

81] indicated that the effect of polyurethane (PUR) foam on the heat capacity of mortars is quite low, which is certainly due to the small value of Cp of foam (0.04×10

6 J/m

3.K). This is compensated with the very high heat capacity of water (Cp water = 4.18×106 J/m

3 K), which contributes to saturating the porosity of mortars. However, this value is compensated by the very high heat capacity of water. In addition, Gouasmi et al. [

78]revealed that the heat capacity of WPLA0 can reach an average value of 1.76×106 J/m

3.K which is significantly higher than that of the other composite mortars. This finding is in agreement with that reported by Badache et al.[

27] , Attache et al. [

82]and Latroch et al. [

26].

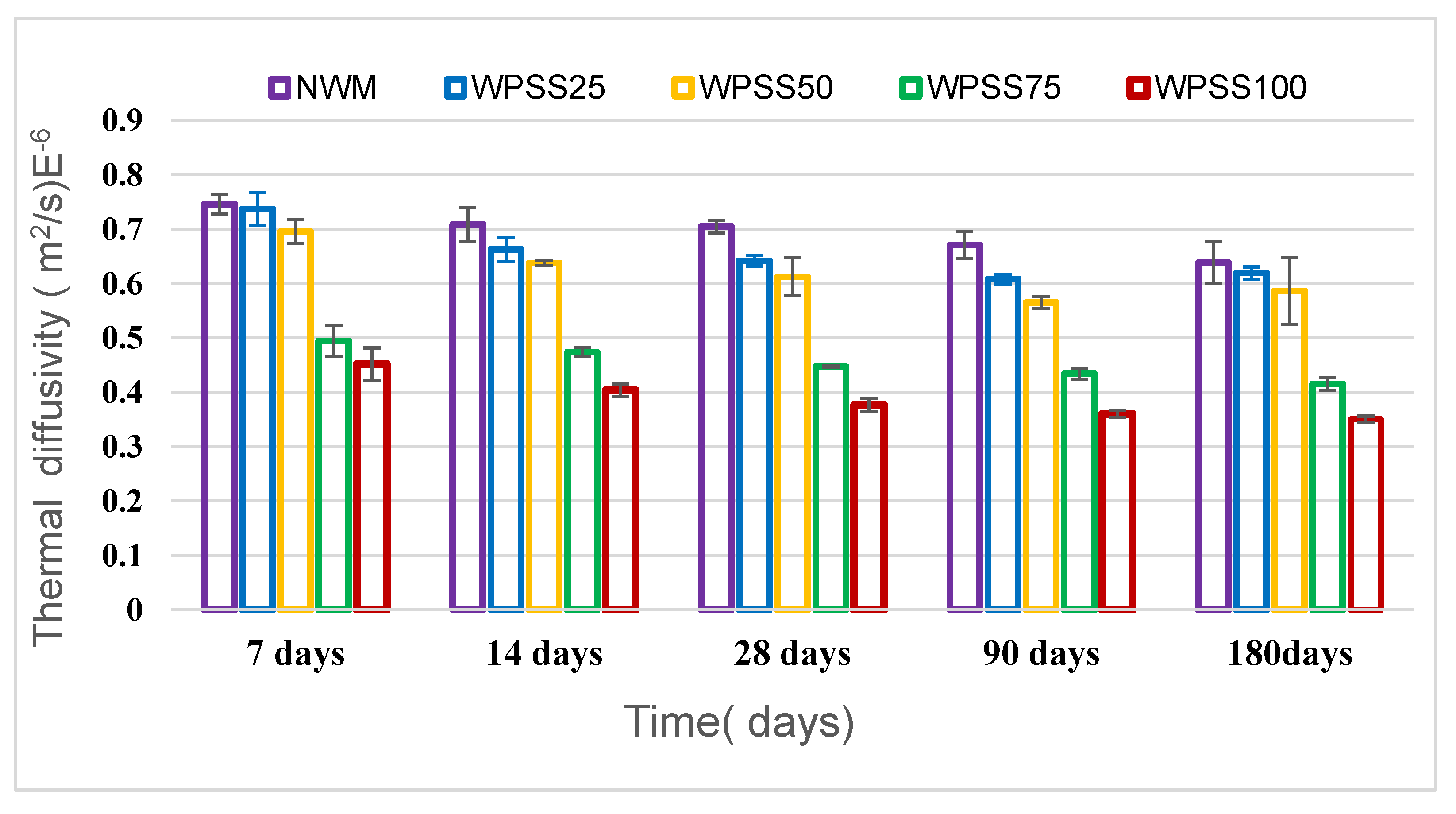

3.6.3. Thermal Diffusivity

Figure 19 illustrates the variation of thermal diffusivity (

a) as a function of time, at room temperature. At 7 days, WPSS25 exhibited a 1% thermal diffusivity decrease, while WPSS100 showed a decrease of 39% with respect to that of control mortar. Likewise, at 180 days, WPSS25 presented a decrease of 3%, while WPSS100 exhibited a decrease of 45% compared to that of the control mortar. It was also observed that the addition of synthesized aggregates leads to a reduction in the thermal diffusivity of WPSS (

a = 0.398×10

-6 m²/s), which is certainly due to the high LSS content. This would also cause a reduction in heat transfer within the composite mortars. It can therefore be said that the lower the diffusivity value, the longer the heat front will take to cross the thickness of the material. These results are similar to those reported by Gouasmi et al. [

78]and Attache et al. [

82]. It should be noted that this can be highly advantageous when these types of composite mortars are used in sustainable buildings with high energy performance.

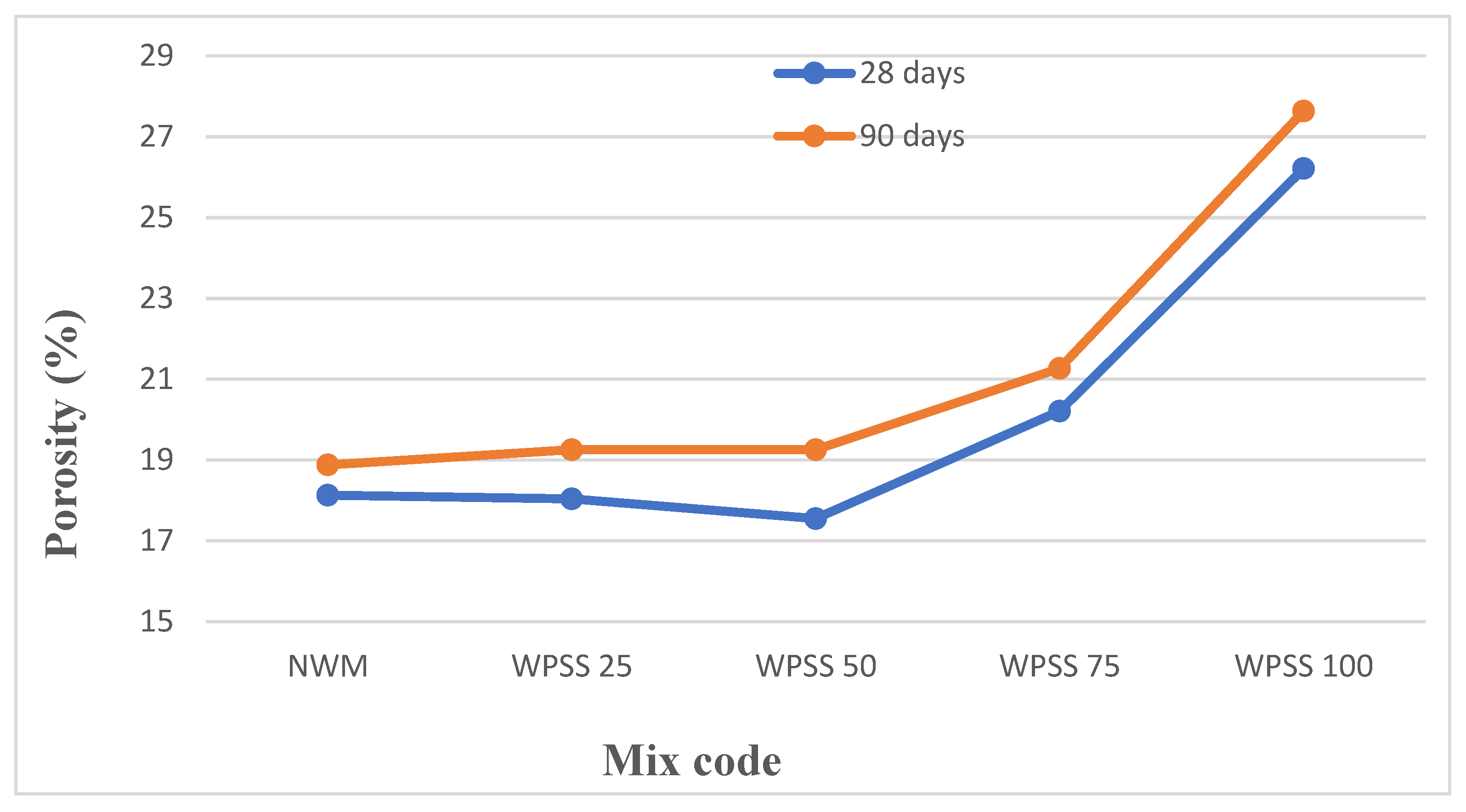

3.7. Porosity

Figure 20 presents the variation of open porosity as a function of the addition rate of the synthesized LSS aggregates. The water accessible porosity of NWM, WPSS25, WPSS50, WPSS75 and WPSS100 mortars are respectively equal to 18%, 19%, 19%, 21% and 27%. The porosity of NWM, WPSS25 and WPSS 50 mortars is almost the same. It was found that the porosity starts to change beyond 50% addition. Furthermore, Erdogmus et al. [

56] noticed that when the EPS and WRTP dosages increase, the apparent porosities of the brick specimens also increase. They then explained this by the fact that, following the addition of plastic waste, there was formation of a non-homogeneous mixture which affected the porosity of the brick specimens. The authors then justified this result by the fact that porosity can be disturbed by two factors, namely the compactness of the mixture and the intrinsic characteristics of LSS.

Figure 21 shows the correlation between the porosity values and UPV values, with a R

2 = 0.74 at 90 days.

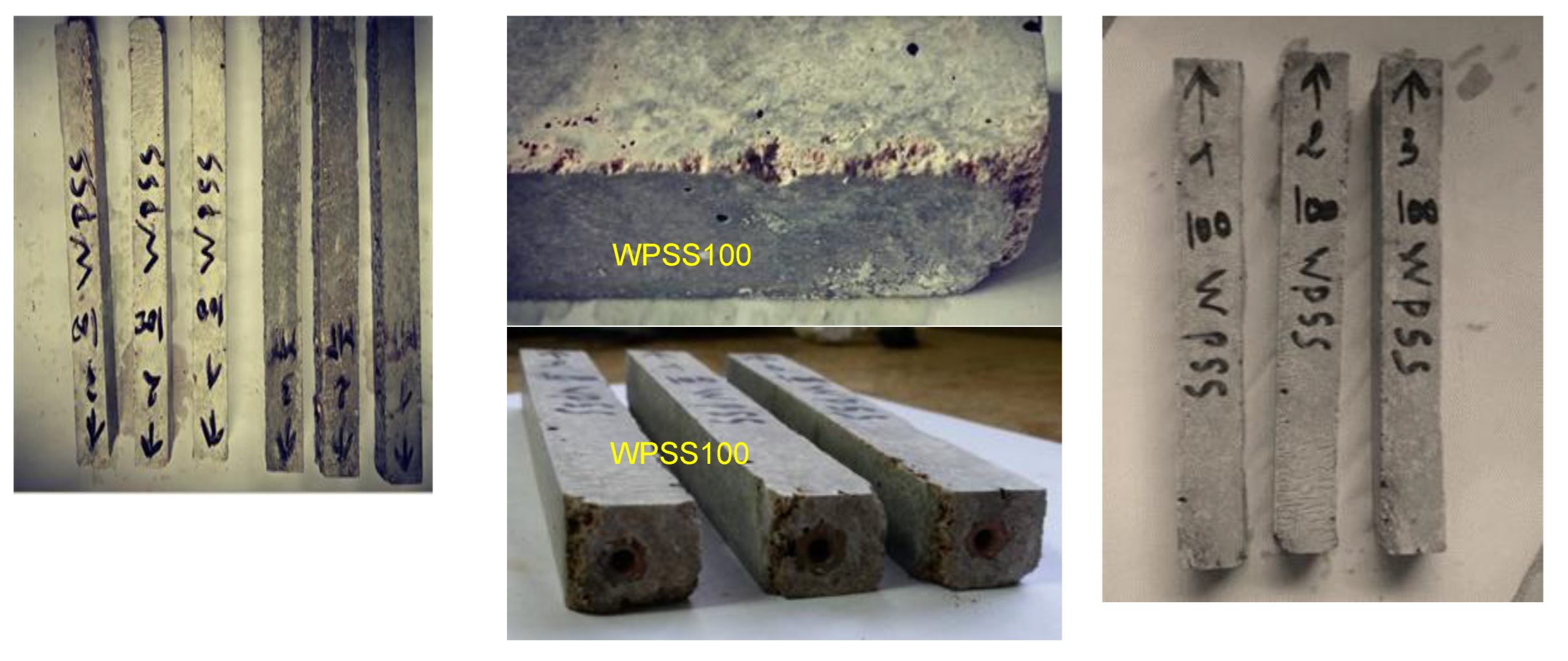

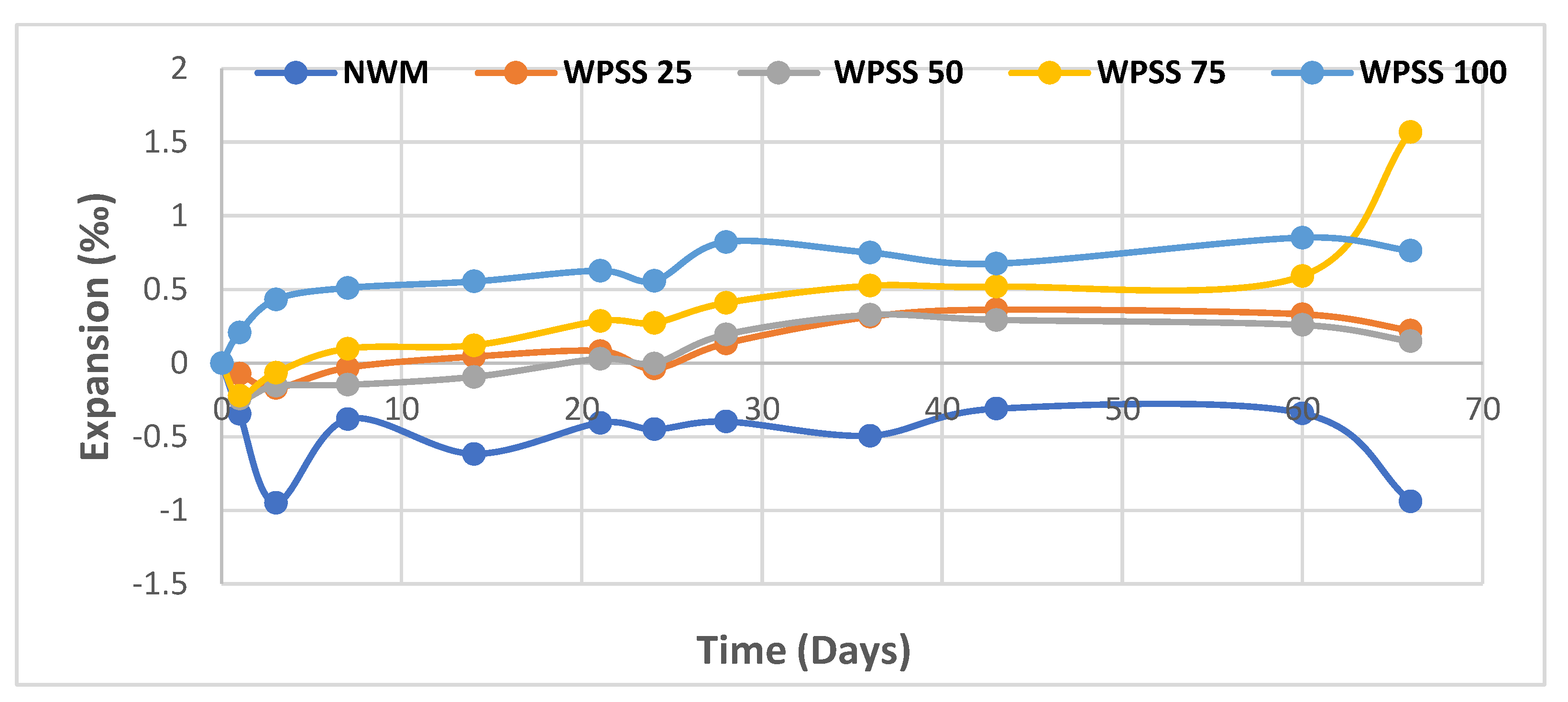

3.8. The Alkali-Silica Reaction

The alkali-silica reaction (ASR) in concrete causes expansion and structural deterioration due to swelling pressures that produce microcracks and make them propagate as a result of the chemical interaction between alkalis and reactive components of the aggregates [

83].

Figure 22 presents the results of the expansion of mortar samples .According to Standard ASTM C1260 [

84], if a specimen expands less than 0.10%, it can be considered as an acceptable mixture which does not present any significant risk of deleterious expansion. However, if the expansion is greater than 0.10%, the risk of deleterious expansion of the mix is likely possible. Finally, if the expansion is greater than 0.20%, then the risk of deleterious expansion in the mix is high.

It was found that the highest expansion value recorded in this test was 1.57‰ at the age of 66 days, for the WPSS75 composite. This value then confirms that there was no ASR reaction in all WPSS mortars. Indeed, the specimens under study were regularly inspected in order to detect the possible appearance of cracks on the surface or to identify probable changes in the color of the specimens (Figure 23). In this same figure, a slight degradation of the edges of the WPSS100 samples was noted.

3.9. Correlation Between Physico-Mechanical and Thermal Properties of WPSS

Table 6 summarizes all possible correlations that can be used to predict any parameter under study.

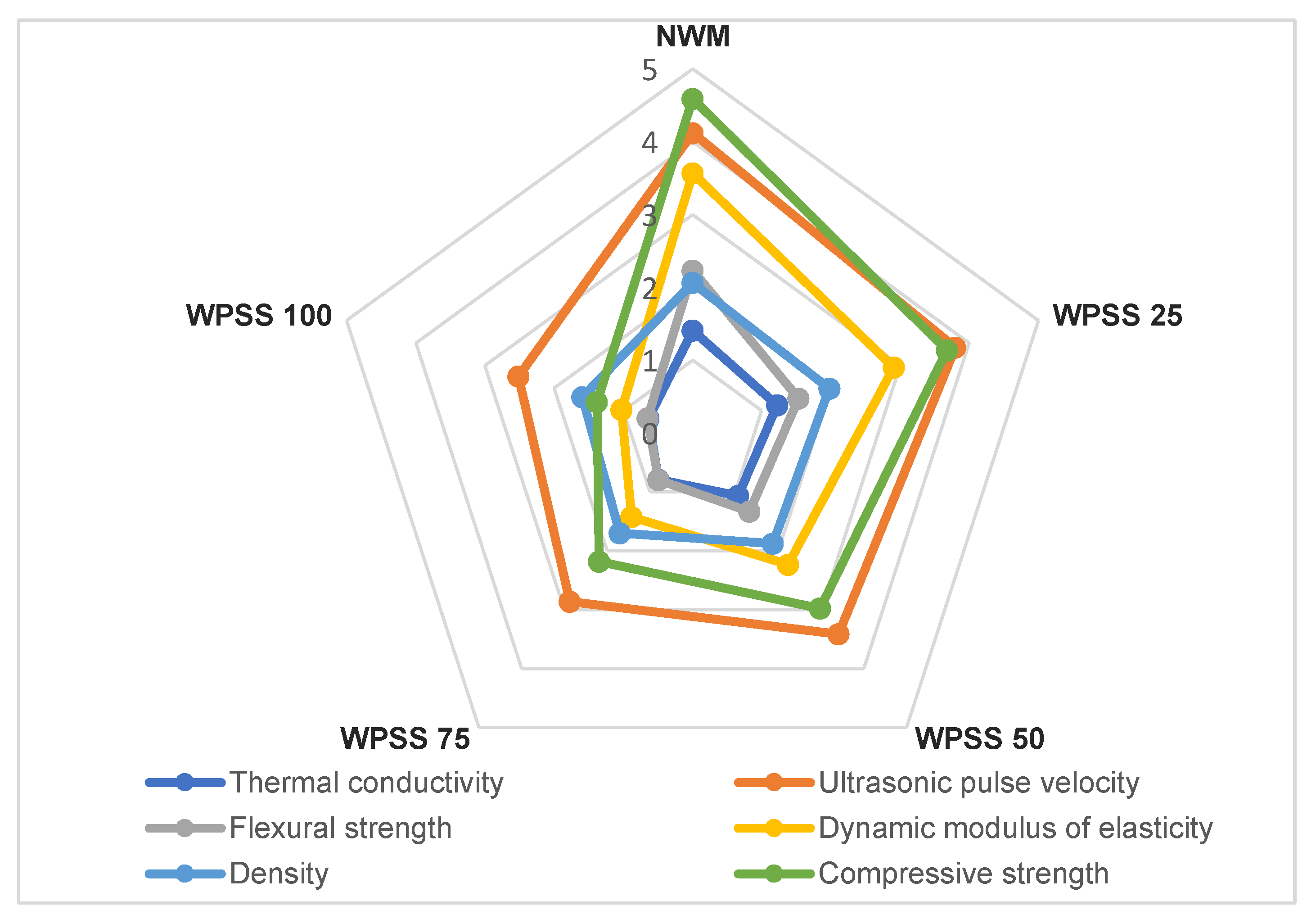

Figure 24 depicts the physico-mechanical and thermal characteristics of WPSS composite mortars. It shows all the physico-mechanical and thermal characteristics of the different formulations under study.

3.10. Impact of Incorporating PET Waste Into Mortar on the Environment

It has been reported that incineration, which is often touted as having the capacity to transform plastic waste into energy, contributes significantly to greenhouse gas emissions. Carbon dioxide (CO₂) was shown to be the main end product of oxidation in an incinerator. Therefore, it is important to estimate the carbon dioxide emissions from the decomposition of carbon contained in the incinerated waste. As part of our study, the amounts of CO₂ emitted were estimated following the incineration of different types of plastics, including PET waste. The recorded data show that CO2 emissions vary in accordance with the type of plastic incinerated.

Belmokkadem et al. [

85] used PP, PE, and PVC plastic waste into concrete and concluded that incorporating recycled plastic waste into the formulation of concrete mixes may be viewed as one of the best solutions to reduce pollution due to energy consumption, waste disposal, and global warming. This approach has several advantages because incorporating recycled plastics into concrete helps to reduce the amount of plastic waste in our environment. By doing so, it is possible to limit the extraction and consumption of natural resources in a significant way. This technique contributes considerably to reducing the carbon footprint and to establishing a more sustainable circular economy.

Table 7 gives a comparison of the amounts of CO

2 emitted during the incineration of various plastics, such as PE, PP and PVC, as reported by [

85], and the combustion of PET that is used in this study

4. Conclusion

This paper presents the results of a systematic study that was conducted on the effect of incorporating lightweight synthesized sand (LSS) aggregates on the properties of composite eco-materials. The results obtained allowed drawing the following conclusions:

- The incorporation of LSS into composite mortars reduces the density by 4, 9, 17 and 23% for WPSS25, WPSS50, WPSS75 and WPSS100 mortars, respectively, as compared to that of the control mortar (NWM). This reduction is due to the fact that the density of LSS is lower than that of natural sand. This is very interesting because using lightweight eco-composites can help to reduce the size of the elements used in construction and consequently diminish the costs of the building materials, their handling, transportation, and overall costs.

- The mechanical performance of composite mortars improved over time (3 - 90 days). The incorporation of 25, 50, 75 and 100% of LSS reduced the compressive strength of WPSS25, WPSS50, WPSS75 and WPSS100 mortars by 20, 35, 52 and 70%, respectively, compared to that of the NWM control mortar. This could be useful when these eco-composites are used in applications requiring low strengths, such as paving stones or sidewalk borders.

- The incorporation of this type of these thermally treated aggregate (LSS) improved the ITZ, which is not the case with plastic wastes without thermal treatment. This suggests that the synthesized aggregates performed better than the shredded aggregates.

- LSS aggregates incorporated into WPSS100 composite mortars slightly increased the ductility but reduced the dynamic modulus of elasticity (Ed) by 18%, 36%, 58% and 69% for the mixtures containing 25%, 50%, 75% and 100% LSS, respectively, compared to that of NWM. These mortars can therefore be used to produce more flexible and more resistant eco-cementitious materials.

The thermal performance of WPSS composites was improved. Indeed, the thermal conductivity of WPSS25, WPSS50, WPSS75, and WPSS100 mixtures was improved by 4%, 8%, 14%, and 18%, respectively, compared to that of NWM. This result encourages us to apply this type of synthesized aggregates in thermal insulation materials due to their energy performance.

The study of porosity revealed that increasing the percentage of LSS aggregates increases the water sensitivity of WPSS composites.

The eco-friendly composite mortars are not susceptible to alkali-silica reaction, which confirms their potential to improve the durability of structures. This feature offers a promising solution to prevent problems related to the reactivity of aggregates.

Comparing the different eco-composites developed in this study helped to identify the most suitable material for direct use in the construction sector. The selection of the materials to be used is based on the analysis of their specific properties. Adopting such an approach allows maximizing the efficiency and performance of these materials in real-life applications.

The integration of these composites in the field of construction can contribute to developing more efficient and sustainable strategies that allow managing plastic waste, reducing CO₂ emissions, and helping to develop a circular economy.

It may finally be concluded that it is possible to produce clean and ecological polymer waste mortars in order to improve the performance of construction elements, develop efficient waste management, and promote sustainability in construction as well. This study represents an important contribution to the field of recycling plastic waste as aggregates to be used in mortar and concrete. It has provided valuable information on various potential applications of these aggregates in clean green buildings. It is then highly recommended to carry out more in-depth and detailed investigations on gas emissions resulting from the synthesis of composite aggregates.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.B., M.H. and A.B.; methodology, A.B., A.S.B., M.H., Y.S and N.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.B and M.H.; writing—review and editing, A.S.B., M.H., W.M. and A.B.; visualization, A.S.B., and M.H.; supervision, M.H., A.S.B. and W.M.; resources W.M. and M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. .

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

This work could be completed as a result of the financial aid from the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research in Algeria, within the framework of the PRFU project A01L02EP130220220001 and the DGRSDT. .

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hees, T., et al., Tailoring hydrocarbon polymers and all-hydrocarbon composites for circular economy. Macromolecular rapid communications, 2019. 40(1): p. 1800608. [CrossRef]

- Hachemi, H., et al., Improving municipal solid waste management in Algeria and exploring energy recovery options. Renewable Energy, 2024. 230: p. 120861. [CrossRef]

- A.N.D. https://and.dz/caracterisation-des-dechets-menagers-et-assimiles-campagne-nationale-2018-2019/. 2018.

- Pacheco-Torgal, F., et al., Use of Recycled Plastics in Eco-efficient Concrete. 2018: Woodhead Publishing.

- Gu, L. and T. Ozbakkaloglu, Use of recycled plastics in concrete: A critical review. Waste Management, 2016. 51: p. 19-42. [CrossRef]

- Babafemi, A.J., et al., Engineering properties of concrete with waste recycled plastic: a review. Sustainability, 2018. 10(11): p. 3875. [CrossRef]

- ACI 213R, Guide for structural lightweight aggregate concrete. Farmington Hills, Michigan: American Concrete Institute Committee 213R;. 2014.

- Poon, C.S., Z. Shui, and L. Lam, Effect of microstructure of ITZ on compressive strength of concrete prepared with recycled aggregates. Construction and Building Materials, 2004. 18(6): p. 461-468. [CrossRef]

- Haghi, A., M. Arabani, and H. Ahmadi, Applications of expanded polystyrene (EPS) beads and polyamide-66 in civil engineering, Part One: Lightweight polymeric concrete. Composite Interfaces, 2006. 13(4-6): p. 441-450. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.Y., R. Dheilly, and M. Queneudec, Valorization of post-consumer waste plastic in cementitious concrete composites. Waste management, 2007. 27(2): p. 310-318. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, Z.Z. and E.A. Al-Hashmi, Use of waste plastic in concrete mixture as aggregate replacement. Waste management, 2008. 28(11): p. 2041-2047. [CrossRef]

- Albano, C., et al., Influence of content and particle size of waste pet bottles on concrete behavior at different w/c ratios. Waste Management, 2009. 29(10): p. 2707-2716. http://dx.doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2009.05.007.

- Kou, S., et al., Properties of lightweight aggregate concrete prepared with PVC granules derived from scraped PVC pipes. Waste Management, 2009. 29(2): p. 621-628. [CrossRef]

- Hannawi, K., S. Kamali-Bernard, and W. Prince, Physical and mechanical properties of mortars containing PET and PC waste aggregates. Waste management, 2010. 30(11): p. 2312-2320. [CrossRef]

- Frigione, M., Recycling of PET bottles as fine aggregate in concrete. Waste management, 2010. 30(6): p. 1101-1106. [CrossRef]

- Madandoust, R., M.M. Ranjbar, and S.Y. Mousavi, An investigation on the fresh properties of self-compacted lightweight concrete containing expanded polystyrene. Construction and Building Materials, 2011. 25(9): p. 3721-3731. [CrossRef]

- Junco, C., et al., Durability of lightweight masonry mortars made with white recycled polyurethane foam. Cement and Concrete Composites, 2012. 34(10): p. 1174-1179. [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, E., et al., On the mechanical properties of concrete containing waste PET particles. Construction and Building Materials, 2013. 47: p. 1302-1308. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, N. and J.d. Brito, Waste polyethylene terephthalate as an aggregate in concrete. Materials Research, 2013. 16(2): p. 341-350. [CrossRef]

- Akçaözoğlu, S. and C. Ulu, Recycling of waste PET granules as aggregate in alkali-activated blast furnace slag/metakaolin blends. Construction and Building Materials, 2014. 58: p. 31-37.

- Senhadji, Y., et al., Effect of incorporating PVC waste as aggregate on the physical, mechanical, and chloride ion penetration behavior of concrete. Journal of Adhesion Science and Technology, 2015. 29(7): p. 625-640. [CrossRef]

- Benosman, A., et al., Effect of addition of PET on the mechanical performance of PET-Mortar Composite materials. Journal of Materials and Environmental Science, 2015. 6(2): p. 559-571.

- Islam, M.J., M.S. Meherier, and A.R. Islam, Effects of waste PET as coarse aggregate on the fresh and harden properties of concrete. Construction and Building materials, 2016. 125: p. 946-951. [CrossRef]

- Malešev, M., et al., The effect of aggregate, type and quantity of cement on modulus of elasticity of lightweight aggregate concrete. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering, 2014. 39(2): p. 705-711. [CrossRef]

- Thorneycroft, J., et al., Performance of structural concrete with recycled plastic waste as a partial replacement for sand. Construction and Building Materials, 2018. 161: p. 63-69. [CrossRef]

- Latroch, N., et al., Physico-mechanical and thermal properties of composite mortars containing lightweight aggregates of expanded polyvinyl chloride. Construction and Building Materials, 2018. 175: p. 77-87. [CrossRef]

- Badache, A., et al., Thermo-physical and mechanical characteristics of sand-based lightweight composite mortars with recycled high-density polyethylene (HDPE). Construction and Building Materials, 2018. 163: p. 40-52. [CrossRef]

- Senhadji, Y., et al., Physical, mechanical and thermal properties of lightweight composite mortars containing recycled polyvinyl chloride. Construction and Building Materials, 2019. 195: p. 198-207. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G. and S. Pavia, Physical properties and microstructure of plastic aggregate mortars made with acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene (ABS), polycarbonate (PC), polyoxymethylene (POM) and ABS/PC blend waste. Journal of Building Engineering, 2020: p. 101341. [CrossRef]

- Almeshal, I., et al., Eco-friendly concrete containing recycled plastic as partial replacement for sand. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Alkhrissat, T., Impact of adding waste polyethylene (PE) and silica fume (SF) on the engineering properties of cement mortar. Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering, 2024. 9: p. 100731. [CrossRef]

- Caniato, M., et al., Acoustic and thermal characterization of a novel sustainable material incorporating recycled microplastic waste. Sustainable Materials and Technologies, 2021. 28: p. e00274. [CrossRef]

- Hacini, M., et al., Utilization and assessment of recycled polyethylene terephthalate strapping bands as lightweight aggregates in Eco-efficient composite mortars. Construction and building materials, 2021. 270: p. 121427. [CrossRef]

- Latroch, N., et al., Effect of High Temperature on Composite Mortars Containing Hazardous Expanded Polyvinyl Chloride Waste. Journal of Hazardous, Toxic, and Radioactive Waste, 2021. 25(3): p. 04021011. [CrossRef]

- Limami, H., et al., Study of the suitability of unfired clay bricks with polymeric HDPE & PET wastes additives as a construction material. Journal of Building Engineering, 2020. 27: p. 100956. [CrossRef]

- Del Rey Castillo, E., et al., Light-weight concrete with artificial aggregate manufactured from plastic waste. Construction and Building Materials, 2020. 265: p. 120199. [CrossRef]

- Ikechukwu, A.F. and C. Shabangu, Strength and durability performance of masonry bricks produced with crushed glass and melted PET plastics. Case Studies in Construction Materials, 2021. 14: p. e00542. [CrossRef]

- Aneke, F.I. and C. Shabangu, Green-efficient masonry bricks produced from scrap plastic waste and foundry sand. Case Studies in Construction Materials, 2021. 14: p. e00515. [CrossRef]

- Ye, W., et al., Effects of plastic coating on the physical and mechanical properties of the artificial aggregate made by fly ash. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2022. 360: p. 132187. [CrossRef]

- Babatunde, Y., et al., Influence of material composition on the morphology and engineering properties of waste plastic binder composite for construction purposes. Heliyon, 2022. 8(10). https://doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11207.

- Hamzah, A.F. and R.M. Alkhafaj, An investigation of manufacturing technique and characterization of low-density polyethylene waste base bricks. Materials Today: Proceedings, 2022. 61: p. 724-733. [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, R.R., et al., Strength Properties of Recycled Waste Plastic and Quarry Dust as Substitute to Coarse Aggregates: an Experimental Methodology. Materials Circular Economy, 2023. 5(1): p. 5. [CrossRef]

- Mache, E., E. Nthiga, and G.K. Muthakia, Formulation and characterization of floor tile composite derived from Polyethylene Terephthalate waste and sand. 2023.

- Kashi, M., et al. Innovative lightweight synthetic aggregates developed from coal Flyash. in Proceedings from the 13th international symposium on use and management of coal combustion products (CCPs), Orlando, Florida. 1999. https:// DOI: 10.9790/5736-1604012336.

- Jansen, D.C., et al., Lightweight fly ash-plastic aggregates in concrete. Transportation research record, 2001. 1775(1): p. 44-52. [CrossRef]

- Binici, H., R. Gemci, and H. Kaplan, Physical and mechanical properties of mortars without cement. Construction and Building Materials, 2012. 28(1): p. 357-361. [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.-W., et al., Effects of waste PET bottles aggregate on the properties of concrete. Cement and concrete research, 2005. 35(4): p. 776-781. [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.W., et al., Characteristics of mortar and concrete containing fine aggregate manufactured from recycled waste polyethylene terephthalate bottles. Construction and Building Materials, 2009. 23(8): p. 2829-2835. [CrossRef]

- Mohandesi, J.A., et al., Effect of temperature and particle weight fraction on mechanical and micromechanical properties of sand-polyethylene terephthalate composites: a laboratory and discrete element method study. Composites Part B: Engineering, 2011. 42(6): p. 1461-1467. [CrossRef]

- Gouasmi, M.T., A.S. Benosman, and T. Hamed, Development of materials based on PET-siliceous sand composite aggregates. Journal of Building Materials and Structures, 2018. 4(2): p. 58-67.

- Bouaziz, S. and K. Ait Tahar. Behavior of the Composite Lightweight Concrete. in Applied Mechanics and Materials. 2012. Trans Tech Publ. https://doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.146.39.

- Alqahtani, F.K., et al., Novel lightweight concrete containing manufactured plastic aggregate. Construction and Building Materials, 2017. 148: p. 386-397. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P., et al., Lightweight expanded aggregates from the mixture of waste automotive plastics and clay. Construction and Building Materials, 2017. 145: p. 283-291. [CrossRef]

- Ennahal, I., et al., Performance of Lightweight Aggregates Comprised of Sediments and Thermoplastic Waste. Waste and Biomass Valorization, 2020: p. 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Górak, P., et al., Lightweight PET based composite aggregates in Portland cement materials-Microstructure and physicochemical performance. Journal of Building Engineering, 2021. 34: p. 101882. [CrossRef]

- Erdogmus, E., et al., Enhancing thermal efficiency and durability of sintered clay bricks through incorporation of polymeric waste materials. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2023. 420: p. 138456. [CrossRef]

- Sau, D., A. Shiuly, and T. Hazra, Utilization of plastic waste as replacement of natural aggregates in sustainable concrete: Effects on mechanical and durability properties. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, 2024. 21(2): p. 2085-2120. [CrossRef]

- 2005., in Methods of Testing Cement – Part 1: Determination of Strength, European Committee for Standardization, CEN,. EN 196-1.

- ASTM D5334, Standard Test Method for Determination of Thermal Conductivity of Soil and Soft Rock by Thermal Needle Probe Procedure, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA,. 2000.

- ASTM C597, Standard Test Method for Pulse Velocity Through Concrete, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA. 2009.

- Gupta, T., S. Chaudhary, and R.K. Sharma, Mechanical and durability properties of waste rubber fiber concrete with and without silica fume. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2016. 112: p. 702-711. [CrossRef]

- Senthil Kumar, K. and K. Baskar, Development of ecofriendly concrete incorporating recycled high-impact polystyrene from hazardous electronic waste. Journal of Hazardous, Toxic, and Radioactive Waste, 2015. 19(3): p. 04014042. [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, F.K., et al., Production of recycled plastic aggregates and its utilization in concrete. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, 2017. 29(4): p. 04016248. [CrossRef]

- Gouasmi, M., A. Benosman, and H. Taïbi, Improving the properties of waste plastic lightweight aggregates-based composite mortars in an experimental saline environment. Asian Journal of Civil Engineering, 2019. 20(1): p. 71-85. [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z., et al., Properties of plastic mortar made with recycled polyethylene terephthalate. Construction and Building Materials, 2014. 73: p. 682-687. [CrossRef]

- Gouasmi, M., et al. Destructive and Non-destructive testing of an industrial screed mortar made with lightweight composite aggregates WPLA. in International Journal of Engineering Research in Africa. 2017. Trans Tech Publ.

- Saikia, N. and J. de Brito, Mechanical properties and abrasion behaviour of concrete containing shredded PET bottle waste as a partial substitution of natural aggregate. Construction and building materials, 2014. 52: p. 236-244. [CrossRef]

- Shariq, M., J. Prasad, and A. Masood, Studies in ultrasonic pulse velocity of concrete containing GGBFS. Construction and Building Materials, 2013. 40: p. 944-950. [CrossRef]

- Azhdarpour, A.M., M.R. Nikoudel, and M. Taheri, The effect of using polyethylene terephthalate particles on physical and strength-related properties of concrete; a laboratory evaluation. Construction and Building Materials, 2016. 109: p. 55-62. [CrossRef]

- Akçaözoğlu, S., K. Akçaözoğlu, and C.D. Atiş, Thermal conductivity, compressive strength and ultrasonic wave velocity of cementitious composite containing waste PET lightweight aggregate (WPLA). Composites Part B: Engineering, 2013. 45(1): p. 721-726. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.02.011.

- IS 13311-1, Indian Standard, Method of Non-destructive testing of concrete – Methods of test, Part 1: Ultrasonic pulse velocity [CED 2: Cement and Concrete],. 1992.

- Guo, Y.-C., et al., A review on the influence of recycled plastic aggregate on the engineering properties of concrete. Journal of Building Engineering, 2023: p. 107787. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. and C. Meyer, Performance of cement mortar made with recycled high impact polystyrene. Cement and Concrete Composites, 2012. 34(9): p. 975-981. [CrossRef]

- Benosman, A., et al., Plastic waste particles in mortar composites: sulfate resistance and thermal coefficients. Progress in Rubber Plastics and Recycling Technology, 2017. 33(3): p. 171-202. [CrossRef]

- Ahrens J.T., Rock Physics & Phase Relation: A Handbook of Physical Constant. American Geophysical Union, Washington, USA, pp.240. (1995),.

- Hannawi, K., W. Prince, and S. Kamali-Bernard, Effect of thermoplastic aggregates incorporation on physical, mechanical and transfer behaviour of cementitious materials. Waste and Biomass Valorization, 2010. 1(2): p. 251-259. [CrossRef]

- Boudenne, A., Etude expérimentale et théorique des propriétés thermophysiques de matériaux composites à matrice polymère. 2003, Paris 12.

- Gouasmi, M., et al., Les Propriétés physico-thermiques des mortiers à base des agrégats composites «PET-sable siliceux». J. Mater. Environ. Sci., 2016,. 7( 2): p. 409-415.

- Alqahtani, F.K. and I. Zafar, Characterization of processed lightweight aggregate and its effect on physical properties of concrete. Construction and Building Materials, 2020. 230: p. 116992. [CrossRef]

- Rilem, L., . Functional classification of lightweight concrete. Mater. Struct. 11,281e283. 1978.

- Mounanga, P., P. Turcry, and P. Poullain. Effets thermique et mécanique de l'incorporation de déchets de mousse de polyuréthane dans un mortier. in XXIVèmes Rencontres Universitaires de Génie Civil, Construire: un nouveau défi. 2006.

- Aattache, A., et al., Experimental study on thermo-mechanical properties of Polymer Modified Mortar. Materials & Design (1980-2015), 2013. 52: p. 459-469. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2013.05.055.

- Swamy, R.N., The alkali-silica reaction in concrete. 1991: CRC Press.

- ASTM C1260, Standard test method for potential alkali reactivity of aggregates (mortar-bar method)’, ASTM Standards in Building Codes, 2001: p. 681-85.

- Belmokaddem, M., et al., Mechanical and physical properties and morphology of concrete containing plastic waste as aggregate. Construction and Building Materials, 2020. 257: p. 119559. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Semi-industrial process for the synthesis of LSS aggregates.

Figure 1.

Semi-industrial process for the synthesis of LSS aggregates.

Figure 2.

Particle size distribution curves of LSS and sand used.

Figure 2.

Particle size distribution curves of LSS and sand used.

Figure 3.

Effect of substituting natural sand with synthesized sand on the density in the fresh and hardened state (28 days) of mortars.

Figure 3.

Effect of substituting natural sand with synthesized sand on the density in the fresh and hardened state (28 days) of mortars.

Figure 4.

Variation of compressive strength of WPSS composites.

Figure 4.

Variation of compressive strength of WPSS composites.

Figure 5.

Correlation between the compressive strength and dry concrete density at 28 days.

Figure 5.

Correlation between the compressive strength and dry concrete density at 28 days.

Figure 6.

Variation in flexural strength of WPSS composites.

Figure 6.

Variation in flexural strength of WPSS composites.

Figure 7.

Percentage of change in densities and strengths as compared to control mortar.

Figure 7.

Percentage of change in densities and strengths as compared to control mortar.

Figure 8.

Scanning electron microscopy examination of NWM. NA: Natural aggregate.

Figure 8.

Scanning electron microscopy examination of NWM. NA: Natural aggregate.

Figure 9.

Scanning electron microscopy examination of WPSS100.

Figure 9.

Scanning electron microscopy examination of WPSS100.

Figure 10.

a) Surface of the composite WPSS100 after the bending test, (b) State of the WPSS100 composite after compression, (c) State of the NWM and WPSS100 mortars after the bending test, at 28 days.

Figure 10.

a) Surface of the composite WPSS100 after the bending test, (b) State of the WPSS100 composite after compression, (c) State of the NWM and WPSS100 mortars after the bending test, at 28 days.

Figure 11.

Effect of WPSS on UPV of composite mortars, at 28 and 90 days.

Figure 11.

Effect of WPSS on UPV of composite mortars, at 28 and 90 days.

Figure 12.

Evolution of Ed of WPSS composites.

Figure 12.

Evolution of Ed of WPSS composites.

Figure 13.

Correlation between the dynamic modulus of elasticity Ed and compressive strength.

Figure 13.

Correlation between the dynamic modulus of elasticity Ed and compressive strength.

Figure 14.

Variation of the thermal conductivity of WPSS composites.

Figure 14.

Variation of the thermal conductivity of WPSS composites.

Figure 15.

Effect of the density on thermal conductivity.

Figure 15.

Effect of the density on thermal conductivity.

Figure 16.

Correlation between thermal conductivity and UPV.

Figure 16.

Correlation between thermal conductivity and UPV.

Figure 17.

Evolution of non-destructive test results with respect to those of the control mortar, at 28 days.

Figure 17.

Evolution of non-destructive test results with respect to those of the control mortar, at 28 days.

Figure 18.

Variation of heat capacity of WPSS composites.

Figure 18.

Variation of heat capacity of WPSS composites.

Figure 19.

Variation of the thermal diffusivity of WPSS composites.

Figure 19.

Variation of the thermal diffusivity of WPSS composites.

Figure 20.

Effect of synthesized aggregates on the water accessible porosity.

Figure 20.

Effect of synthesized aggregates on the water accessible porosity.

Figure 21.

Correlation between the UPV values and porosity values.

Figure 21.

Correlation between the UPV values and porosity values.

Figure 22.

Expansion of WPSS composites as a function of exposure time to a 1N NaOH solution at 80 °C.

Figure 22.

Expansion of WPSS composites as a function of exposure time to a 1N NaOH solution at 80 °C.

Figure 24.

Relationship between physical, mechanical, and thermal properties of the composites under consideration in this study.

Figure 24.

Relationship between physical, mechanical, and thermal properties of the composites under consideration in this study.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of CPJ CEM II /B 42.5 N cement, silica sand, and calcareous.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of CPJ CEM II /B 42.5 N cement, silica sand, and calcareous.

| Eléments |

SiO2 |

Al2O3 |

Fe2O3 |

CaO |

MgO |

K2O |

SO3 |

Na2O |

PAF |

Cl- |

CaCO3 |

CO2 |

| Ciment |

17.40 |

4.12 |

2.97 |

61.15 |

1.16 |

0.66 |

2.46 |

0.13 |

8.85 |

0.017 |

- |

- |

| Ss |

83.29 |

0.21 |

0.45 |

7.03 |

4.20 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

1.00 |

| Sc |

11.76 |

- |

0.91 |

44.35 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

59.09 |

26.00 |

Table 2.

Mineralogical composition of clinker.

Table 2.

Mineralogical composition of clinker.

| C3S |

C2S |

C3A |

C4AF |

| 64.00 |

15.00 |

8.00 |

12.16 |

Table 3.

Physical parameters of sands used.

Table 3.

Physical parameters of sands used.

| Physical properties |

Natural Sand |

LSS |

| Shape |

Angular |

Angular |

| Absolute density (g/cm3) |

2.630 |

1.68 |

| Apparent density (g/cm3) |

1.460 |

1.020 |

| Equivalent of sand «%» |

77.00 |

- |

| Fineness modulus «FM» |

2.42 |

2.93 |

| Absorption coefficient (%) |

0.56 |

0.040 |

| Coefficient of curvature «Cc» |

0.55 |

0.60 |

| Coefficient of uniformity «Cu» |

4.72 |

5.83 |

| Thermal conductivity «k» (W/m.K) |

- |

0.589 |

Table 4.

Composition of waste plastic synthetic sand (WPSS) lightweight composite mortars.

Table 4.

Composition of waste plastic synthetic sand (WPSS) lightweight composite mortars.

| Composites |

LSS /S(%) *

|

Sand Mix(g) |

Admixture (%) ** |

Cement(g) |

E/C |

Spreading (%) |

| LSS |

Sand |

| NWM |

0 |

0.0 |

1350.0 |

0.90 |

450 |

0.5 |

70 |

| WPSS25 |

25 |

235.8 |

1012.5 |

0.50 |

450 |

0.5 |

74 |

| WPSS50 |

50 |

471.6 |

675.0 |

0.40 |

450 |

0.5 |

73 |

| WPSS75 |

75 |

707.4 |

337.5 |

0.35 |

450 |

0.5 |

80 |

| WPSS100 |

100 |

943.2 |

0.0 |

0.30 |

450 |

0.5 |

69 |

Table 6.

Correlations between different properties of WPSS composites.

Table 6.

Correlations between different properties of WPSS composites.

| Properties |

Correlation equation |

Correlation coefficient |

| Cs – UPV |

Y=0.0522x+1.7967 |

R2=0.9878 |

| UPV– density |

Y=0.2935x+0.8611 |

R2=0.9978 |

| Ed–Cs |

Y=11.954x+2.9406 |

R2=0.9897 |

| λ– density |

Y=0.6153+1.2119 |

R2=0.9953 |

| λ– UPV |

Y=2.0971+1.1941 |

R2=0.9984 |

| Fs – Cs |

Y=19.408+4.2017 |

R2=0.9612 |

| Cs -Density |

Y=0.0153+1.3899 |

R2=0.9793 |

| λ– Porosity |

Y=29.056x2-68.331x+57.257 |

R2=0.9434 |

| Cs-porosity |

Y=0.167x2-1.2285x+39.65 |

R2=0.9697 |

Table 7.

emissions from different plastics.

Table 7.

emissions from different plastics.

| |

Carbon content

(% by weight) |

Fossil carbon share

(% of total carbon) |

Oxidation rate

(%) |

Emission of C (kg eq C/t) |

| PE [85] |

85,6 |

100 |

95 |

813 |

| PP [85] |

85,5 |

100 |

95 |

812 |

| PVC [85] |

40,1 |

100 |

95 |

381 |

| PET (The current study) |

62,5 |

100 |

95 |

594 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).