1. Introduction

Von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) disease (ORPHA:892) is an autosomal dominant, rare tumor syndrome caused by germline mutations in the tumor suppressor gene

VHL (NC_000003.12), located on chromosome 3 (3p25-p26) [

1]. With an incidence of approximately 1 in 36,000 births and nearly complete penetrance (>90%) by the age of 65, patients with VHL develop hemangioblastomas (Hbs) in the central nervous system (CNS) [

2]. In addition to CNS tumors, visceral lesions such as clear-cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), pheochromocytomas, and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors may also occur in these individuals. The CNS tumors typically include hemangioblastomas in the retina and the craniospinal axis (cerebellum, brainstem, and spinal cord), with more rare occurrences of endolymphatic sac tumors (ELSTs) [

3,

4]. Patients carry

VHL mutations in a heterozygous state across all cells of the body. However, tumor formation occurs at sites where a second somatic event ("second hit") inactivates the remaining wild-type

VHL allele, resulting in complete loss of functional VHL protein.

This gene contains three exons: exon 1 includes nucleotides 1–340 (codons 1–113), exon 2 spans nucleotides 341–463 (codons 114–154), and exon 3 covers nucleotides 464–642 (codons 155–213) [

5,

6,

7]. Affected individuals inherit one mutated

VHL allele from a parent, and disease development typically follows loss or inactivation of the remaining wild-type allele. Mutations have been reported in all three exons. Approximately 30–60% are missense mutations, 20–40% are large intragenic deletions (ranging from 0.5 to 250 kb), 12–20% are small insertions or deletions, and 7–11% are nonsense mutations [

8].

The natural history of Von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) disease indicates that the average age of symptom onset is around 26 years (according to Orphanet), with 80% of patients developing at least one CNS hemangioblastoma (Hb) during their lifetime [

9,

10]. In the absence of effective treatments for VHL-related tumors, repeated surgeries remain the primary approach to managing the disease [

11]. However, these recurrent surgeries can significantly diminish the patient's quality of life [

12]. While inhibitors targeting VEGF/VEGFR and mTOR have been evaluated in clinical trials, their efficacy has been limited [

1]. In advanced clear-cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), tyrosine kinase inhibitors like Pazopanib have been used, though resistance often develops as the tumor adapts to the microenvironment [

13]. Recently, the selective HIF-2α inhibitor belzutifan has shown promising short-term therapeutic effects in treating VHL-related ccRCC and its associated symptoms [

13,

14]. The progression of hemangioblastomas tends to be notably faster in symptomatic tumors, particularly those with cysts. Patients under the age of 20 are more likely to develop new tumors compared to those older than 40 years [

9]. A higher tumor burden may indicate or result from other aggressive underlying pathological factors.

Recently, we have published the two sides of the coin on VHL disease. On one hand, a 72-year-old VHL patient showing any disease symptoms because she also is carrier of a pathogenic mutation of another rare disease, Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis (ORPHA: 228360), counteracting this fact the complete penetrance of VHL, and avoiding the tumor growth due to her

VHL pathogenic mutation one each other [

15]. On the other hand, the case followed up, in the present manuscript, shows a patient who had a notable early onset of the disease (11 years old), showing a very severe phenotype [

16]. Between its 13 and 26, he suffered up to 6 surgeries with a total of 12 CNS Hbs ressected. A germinal and somatic clinical exome was performed after the surgery in 2022 and the study revealed the presence of an additonal germinal pathogenic mutation to the already known

VHL deletion. It is a mutation in heterozygous condition at the

CHEK2 gene in in the germinal line, worsening the pathological condition of the patient.

The

CHEK2 mutation was inherited by maternal side [

16]. The father and sister of this patient did not carry the

CHEK2 gene mutation, while being both heterozygous for the

VHL deletion. These relatives don’t show such a severe phenotype as in the case under study.

This case highlights the importance of individualized, large-scale genetic analyses in inherited rare diseases with atypical clinical histories, to uncover additional mutations that may contribute to the observed phenotype. Therefore, a deeper understanding of tumor pathophysiological features may contribute to more accurate prognostic assessments and enhance the effectiveness of both surgical and non-surgical interventions, while also opening new avenues for the development of targeted therapies.

The present work focuses on the molecular analysis and a personalized therapeutic perspective, with the aim to improve the health condition of this and other VHL patients whose pathological issues don’t fit the natural history of the VHL disease.

Once the genetic condition of the patient was uncovered, we took advantage of the open source PanDrugs algorithm (

https://www.pandrugs.org) which scores gene actionability of the tumor molecular alterations and drug feasibility to provide a personalized and prioritized evidence-based list of potential therapeutic drugs [

17].

Olaparib, an oral inhibitor of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) [

18], was indicated as the first choice. Then,

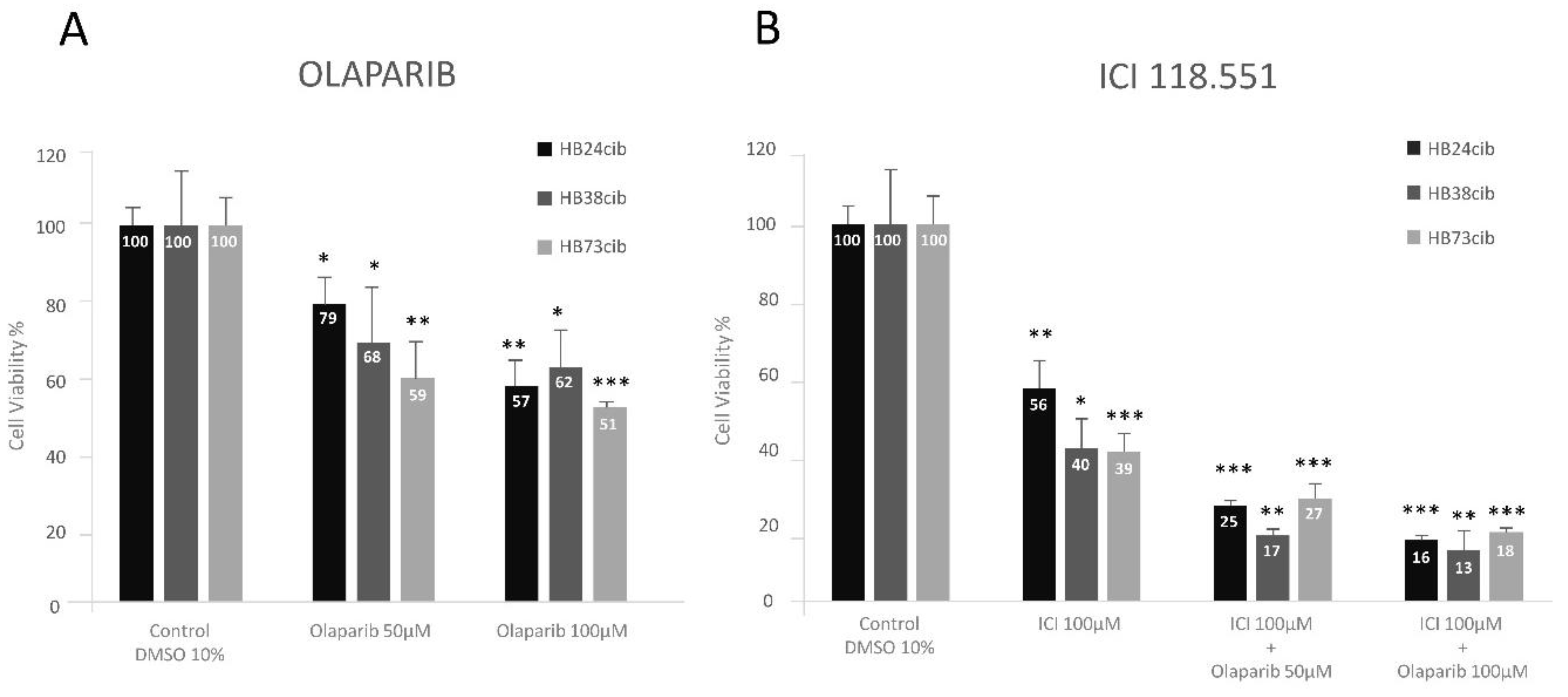

in vitro studies of the primary cultures, treated with Olaparib alone or in combination with ICI-118,551 (ICI), a beta-adrenergic receptor 2 blocker with demostrated therapeutic properties in VHL disease, showed therapeutic properties since tumor cell viabilty was impaired 50% and 80%, respectively.

Olaparib (Lynparza) (AstraZeneca, Cambridge, UK), is an oral inhibitor of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) [

18], specifically designed to competitively inhibit NAD

+ at the catalytic sites of PARP1 and PARP2, essential for DNA single-strand breaks (SSBs) repairing, via the base excision repair (BER) pathway. By inhibiting this pathway, Olaparib leads to the accumulation of unrepaired SSBs, which eventually result in harmful double-strand breaks (DSBs). In tumors with homologous recombination HR deficiencies, Olaparib induces synthetic lethality. The present study examined

VHL gene mutations and expression patterns across the patient’s last three consecutive surgical specimens. In addition, patient-derived cultured cells were treated with Olaparib as a personalized therapeutic approach, given the presence of germline mutations in both

VHL and

CHEK2.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics

The procedure was fully approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Agency for Research in Spain (CSIC), under reference number 075/2017. Informed consent was obtained from the patient for each surgery.

2.2. Cell Cultures

Primary cultures of CNS hemangioblastomas (Hb) were established from surplus tissue obtained during the patient's last three surgeries. The samples were mechanically and enzymatically dissociated and subsequently cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS), following the protocol described in [

19]. The tissue used was fresh and not preserved in RNA later or formalin-fixed. Cells began to proliferate shortly after dissociation and were maintained in culture until confluence was reached.

Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs) were cultured in EBM-2 medium (Lonza), combined with SingleQuots™ (Lonza) endothelial growth medium-2 (EGM-2) components. The culture medium was additionally enriched with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, and 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin., 100X antibiotic-antimycotic, and Mycozap (all from GIBCO, Grand Island, NY, USA excepting Mycozap, from Lonza, Basel, Switzerland). The samples had been collected at three different surgeries, in 2018 (Hb24cib) and 2020 (Hb38cib), both from spinal cord, and in 2024 (Hb73cib) from cerebellum.

2.3. Genomic DNA Extraction and Sequencing

Total DNA was isolated from peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) and freshly obtained tumor tissue using the QIAamp Mini Kit (Qiagen, Düsseldorf, Germany), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Library preparation was carried out using a custom panel designed with SureSelectXT technology (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA), targeting the exonic regions of clinically relevant genes along with adjacent splicing sites (within 5–20 bp). Sequencing was performed on the NovaSeq 6000 System™ (Illumina, CA, USA), a high-throughput next-generation sequencing platform. Tumor-derived libraries were sequenced at an average coverage depth of 500×. The resulting reads were mapped to the human reference genome (GRCh38/hg38) and processed through quality control pipelines. Variant calling focused on mutations located within exons and splice-site regions (minimum 5 bp from exon–intron boundaries).

2.4. RNA Extraction, Reverse Transcription, and qPCR

A culture of 3 × 10⁵ primary tumor cells was processed for RNA isolation using the NucleoSpin RNA purification kit (Macherey-Nagel GmbH&Co, Düren, Germany), in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Approximately 1 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed using the Applied Biosystems kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Quantitative PCR was conducted with the FastStart Essential DNA Green Master mix (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) to amplify the VHL gene, with 18S RNA serving as a housekeeping control. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate, and experiments were performed at least three times. The primers used for amplification were:

18S Fwd CTCAACACGGGAAACCTCAC; Rev CGCTCCACCAACTAAGAACG, and VHL Fwd ATCCGTAGCGGTTGGTGA; Rev CTCACGGATGCCTCAGTCTT.

2.5. PanDrugs.

PanDrugs (

http://www.pandrugs.org) offers a bioinformatics platform designed to prioritize anticancer drug therapies based on personalized multi-omics data. The software consolidates information from 23 primary data sources and maintains 74,087 drug-target interactions derived from 4,642 genes and 14,659 distinct compounds.

For identifying potential therapeutic drugs, we introduced VHL and CHEK2 as the target genes mutated in the patient’s germ line. The system, based on their clinical status and signaling pathway effect, scores and suggests some drugs indicating its effect in one or both affected genes. Nevertheless, we searched for those who showed some activities in both mutations.

2.6. Western Blot (WB)

Cell lysates were prepared from around 1 million cells cultured in a P10 plate to analyze proteins in Western Blot. Final protein concentrations were measured using the Coomassie (Bradford) Assay Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Samples were prepared for electrophoresis on Mini-Protean TGX Precast Gels (4-20% gradient) (BIORAD, Hercules, CA, USA), loading 15 µg per well in a total 20 µl volume. Each sample was loaded by duplicate in Laemmli Buffer. Separation was performed at 150V for one hour and proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham, GE, Chicago, IL, USA) at 4°C overnight 25 V in (Tris-Glycine, 10% methanol) buffer. The membrane was transiently stained with Ponceau red to check the amount of transferred protein. The membrane was then rinsed with PBS-Tween (0.05%) and incubated with a blocking solution consisting of 5% skimmed milk in PBS-Tween-20 for one hour. Afterwards, it was incubated with mAb anti-von Hippel-Lindau (Novus Biologicals Cat NB110-10160), Centennial, CO, USA) 1:500 diluted, at 4ºC, overnight. Next day, the membrane was washed and incubated for one hour with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (Dako, Agilent Technologies) 1:2,000 diluted. The peroxidase reaction was done with the Super Signal West Pico Plus kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and detection of the luminescent signal was analyzed by a Gel-Doc (BIORAD).

2.7. Cell Treatments

In 96-well plates, 3 experiments were performed for each of the cell cultures from 3 independent and consecutive surgeries of the same patient. In each experiment, 7 treatment conditions were set up, each in quadruplicate. In each well, 5000 cells were seeded in a total volume of 150µL culture medium. Cells were treated for 48 hours with ICI 118.551 (Sigma-Aldrich I127, San Louis, Ma, USA) (100µM), Olaparib (50µM and 100µM) (Sigma, Aldrich, SML3705), or the combination of both (ICI 100µM + Olaparib 50µM or ICI 100µM + Olaparib 100µM) and viability was measured by the commercial CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay kit (Promega). This kit measures the amount of ATP produced by the cells, and the reaction was made following manufacturer's instructions. The luminescence resulting from the reaction was quantified in the GloMax®-Multi+ Detection System (Promega).

2.8. Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t-test for comparisons between two groups, and two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test for analyses involving two independent variables (performed using GraphPad Prism version 8.0.1). Normality and homogeneity of variances were verified before applying parametric tests. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, with significance levels indicated as follows: p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.001, and p < 0.0001."

3. Results

3.1. DNA Analysis in Germline and Hemangioblastoma Primary Cultures from Different Surgeries of the same Patient

A personalized study of tumoral cells grown from VHL surplus surgeries of an especially severe VHL case, previously published by us [

16] has been followed up. The patient had an early onset of the disease (11 years old) with a very severe phenotypes suffering up to 6 CNS surgeries with a total of 12 CNS Hbs resected between 13 and 26 years of age (

Table 1).

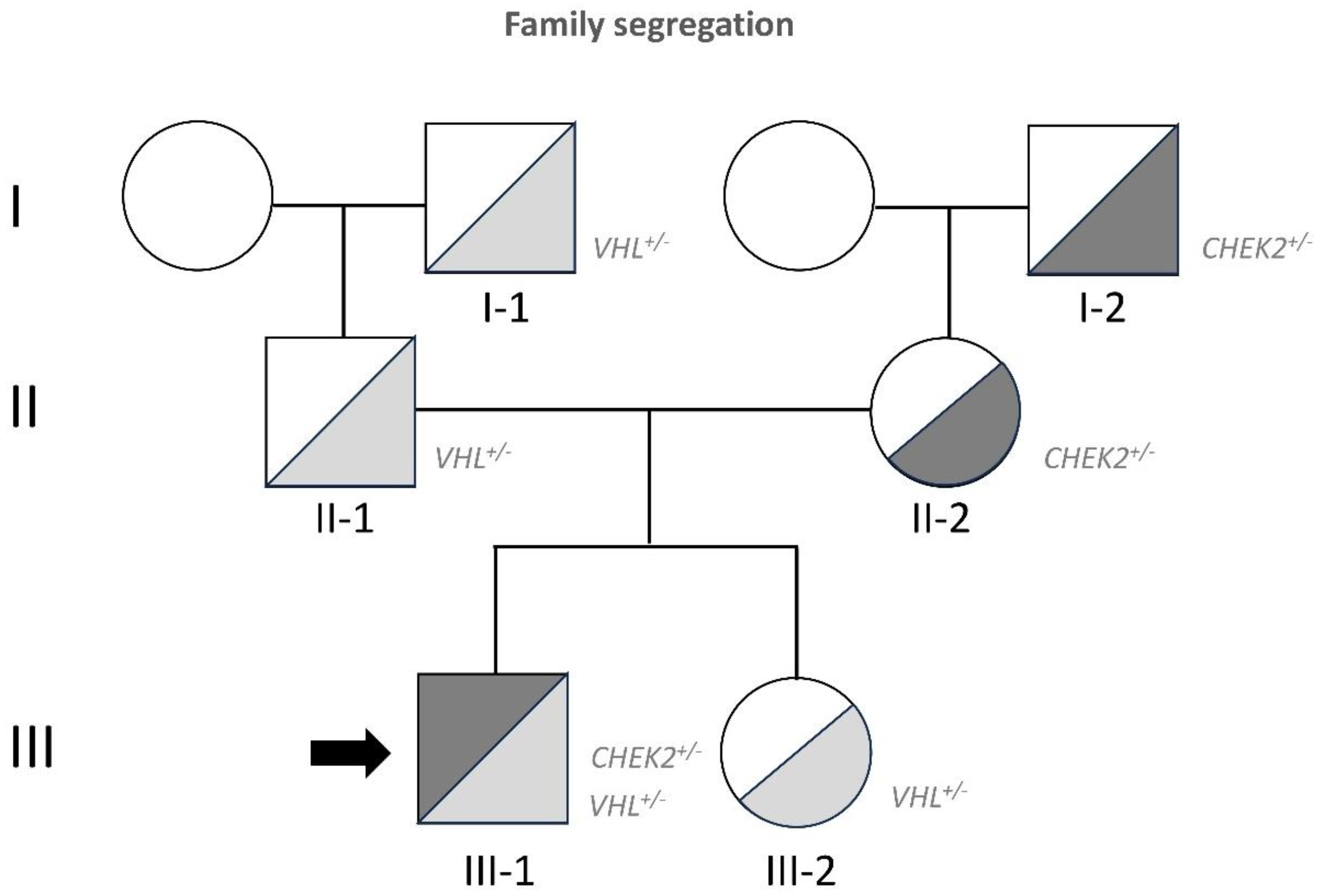

Genetic analysis revealed a complete deletion of one

VHL allele, inherited from the paternal side, spanning from exon 1 (Chr3:10,142,089) to exon 3 (Chr3:10,149,946) [

16] (

Figure 1). Additionally, the heterozygous variant c.1259+1G>C was detected, which results in the skipping of exon 10, frameshift of the coding sequence, and premature termination of the resulting protein (p.Pro1336Frameshift*2). Both variants are classified as highly pathogenic. The surgeries and type of Hbs were as showed in

Table 1, while the mutation segregation of

VHL and the

CHEK2 mutations found after DNA analysis of tumor after 2022 surgeries are depicted in

Figure 1.

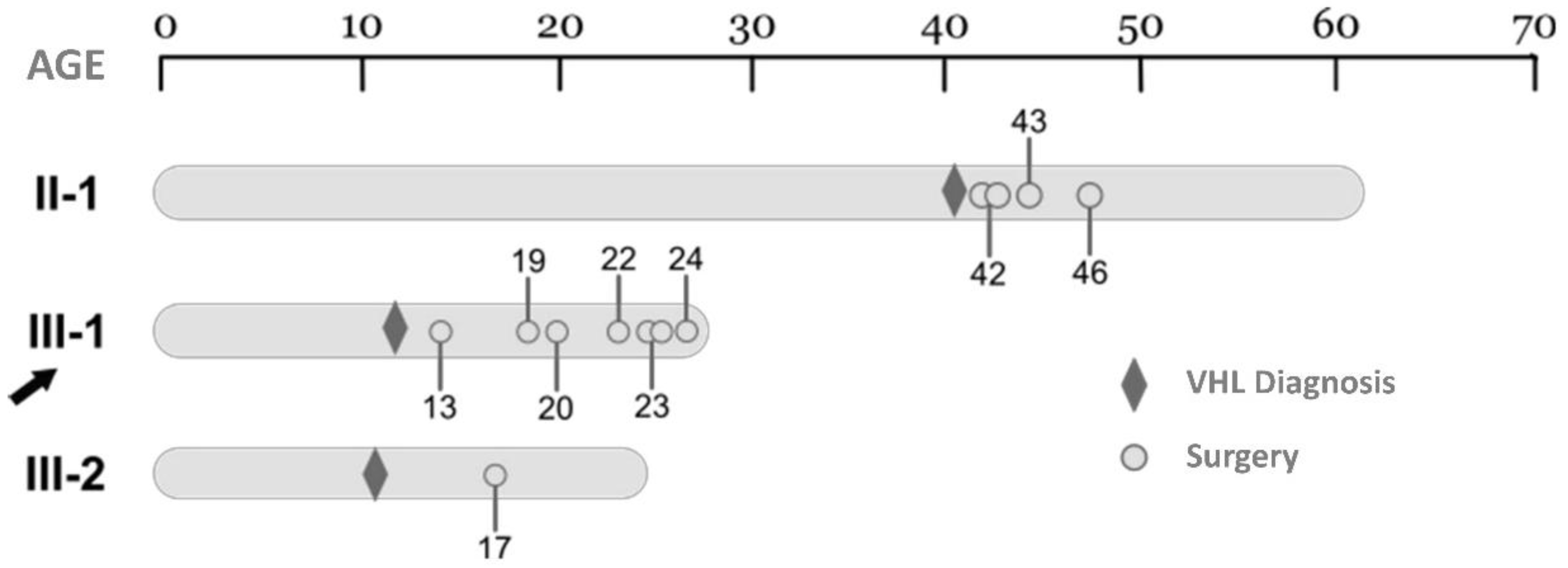

The timeline of all the surgeries in the members of the family affected by the

VHL germinal allelic loss is exemplified in

Figure 2.

In 2023 a new surgery was carried out, resecting 2 Hbs from cerebellum. DNA from one of them was extracted and subjected to a clinical exome analysis with a depth of >500 readings. Then, in addition to the two germinal heterozygous mutations in VHL and CHEK2, previously described, a second hit, in the VHL remaining allele was identified; a somatic 4 bp nucleotide deletion of VHL (c.402_405del (AATT)), in 34.7% of the cells. This deletion leads to a frameshift with a premature stop of the translation process (p.Glu134Aspfs*24). In the previous clinical exome analysis of the 2022 Hb surgery (Hb65cib), the second hit in the other allele of VHL was not found, although other somatic mutations in genes involved in tumor development by LOF were reported. The changes were a deletion in exon 1 of BRAF at cytoband 7q34 and a deletion in exon 1 of PTPN11 at cytoband 12q24.13. These mutations were not present in the germline. These different mutations found in tumors of two consecutive surgeries, mediating less than 1 year among them, demonstrate a high rate of mutation present in the case under study. On the other hand, the different mutations found in the Hbs analyzed point to the individuality, and independent somatic nature of each Hb.

3.2. The second Hit Differs in Different Hbs of the Same Patient: VHL Expression at RNA and Protein Level

As mentioned, in the last Hb somatic exome analysis, from the last surgery (Hb73cib), we were able to find the second hit mutation in exon 2 of VHL. At least 35% of the cells, in the surgical surplus, had a second hit with a mutation VHL c.402_405del (AATT). We wondered whether we could find a second hit in the primary cultures grown from the previous surgeries. Total DNA was extracted from the primary cell cultures derived from the three previous surgeries and the VHL gene was sequenced without finding any other mutation but the germinal one, the complete deletion of VHL. Several possibilities may account for this second hit triggering tumor development: mutations in promoters, enhancers, deep intronic regions, or epimutations in the pattern of VHL DNA methylation. These possibilities cannot be detected by the DNA exomal approach.

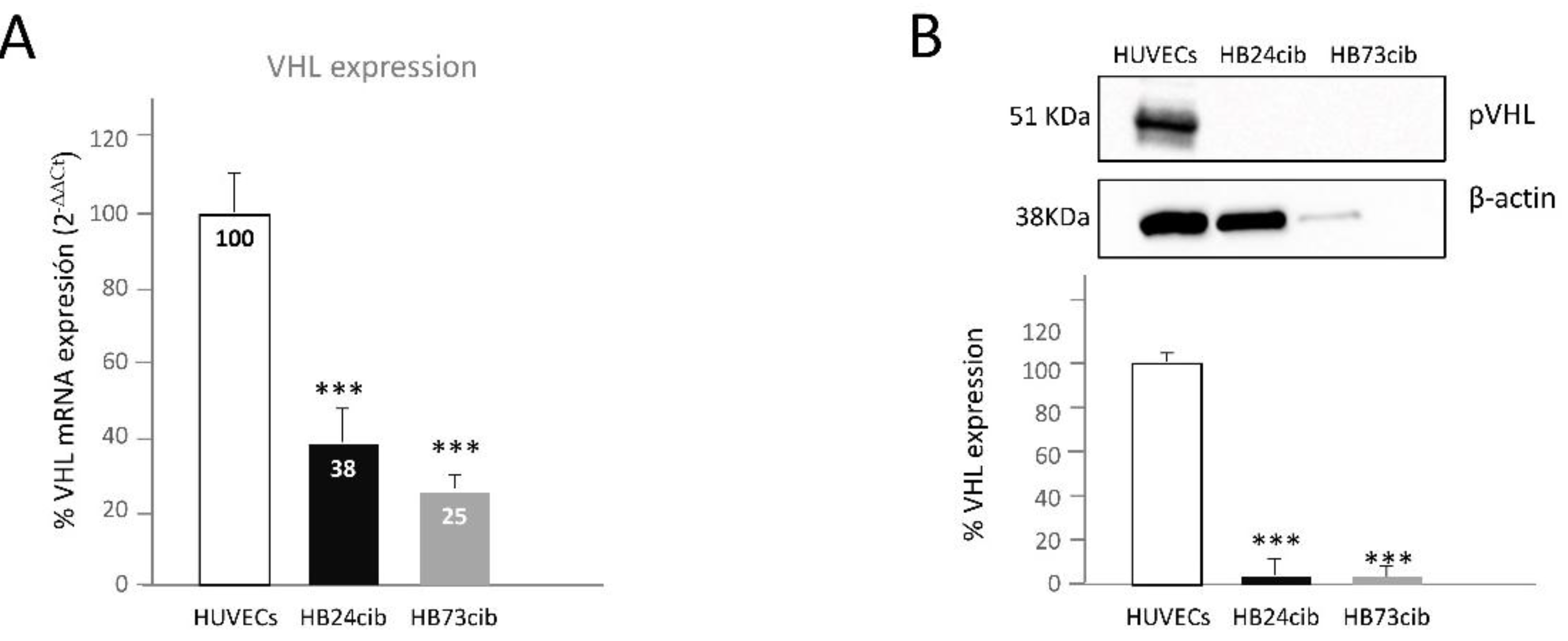

Next, the RNA levels of

VHL in cells of the three last surgeries were analyzed by RT-qPCR. We found RNA expression in all of them, but at significantly reduced than in HUVECs, a primary culture of normal endothelial cells used as control. In this particular case, only one

VHL allele could be transcribed, since the germinal mutation was a complete allele deletion. Thus, the RNA was coming from the other allele, wild type in the germinal line. However, since the RNA was coming from Hbs, a second hit in

VHL was predicted to account for the decrease in RNA expression. From the

Figure 3A, representing the RT-qPCR it is clear the cells from Hbs synthesize RNA from this second allele, although less than 50%. In addition, a dot plot of qPCR cycles results is shown in

Figure S1.

3.3. Hemangioblastoma Cells Express Less RNA of VHL but Have No VHL Protein Expression

The next question to find out was the expression of pVHL. If the cells from the surgeries were expressing RNA from

VHL, could they express, to some extent, pVHL? As observed, WB analysis showed no pVHL expression, even after long exposure times. HUVECs primary culture was used as a positive control showing pVHL band, since this protein is ubiquitously expressed by all normal cells. It was a complete absence of pVHL according to the WB analysis (

Figure 3B). Although Hb73cib lane shows much lower load, we exposed the blot for pVHL 5 min and actin for 1 minute. pVHL never appeared although the band of pVHL of HUVECs was saturated. Thus, we are sure there is no protein VHL, in spite of having lower protein content in this lane. Thus, the RNA detected in these cells is not translated into a complete/stable pVHL. In the last case, Hb73cib, we know that at least 34% of cells had a second mutation in exon 2, leading to a stop codon, but in other previous surgeries this second hit, could not be found. Therefore, Hb cells exhibit a complete loss of expression in pVHL).

3.4. Selection of Olaparib as the Best Candidate by Using PanDrugs Software

As commented in materials and methods section. PanDrugs software was used to identify potential therapeutic drugs for tumor cells mutated in VHL and CHEK2 genes. Among the three drugs with double intervention, Olaparib was scored as a potential drug for both mutations.

Olaparib (Lynparza) (AstraZeneca, Cambridge, UK), is an oral inhibitor of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) [

18], specifically designed to competitively inhibit NAD

+ at the catalytic sites of PARP1 and PARP2, essential for DNA single-strand breaks (SSBs) repairing, via the base excision repair (BER) pathway. By inhibiting this pathway, Olaparib leads to the accumulation of unrepaired SSBs, which eventually result in harmful double-strand breaks (DSBs). In tumors with homologous recombination HR deficiencies, Olaparib induces synthetic lethality.

3.5. Personalized In Vitro Treatment of Tumoral Cells with Olaparib

The aggressive growth rate of hemangioblastomas in this patient, along with genetic findings obtained through next-generation sequencing (NGS) in the last two surgical samples, points to a high mutation burden. This is likely attributable to the presence of two germline mutations, one in the VHL gene and another in the CHEK2 gene. Since in the last years the patient had suffered almost a surgery per year, he was derived to the department of genetic oncology, where the possibility of an “off label” treatment of the patient with Olaparib was suggested.

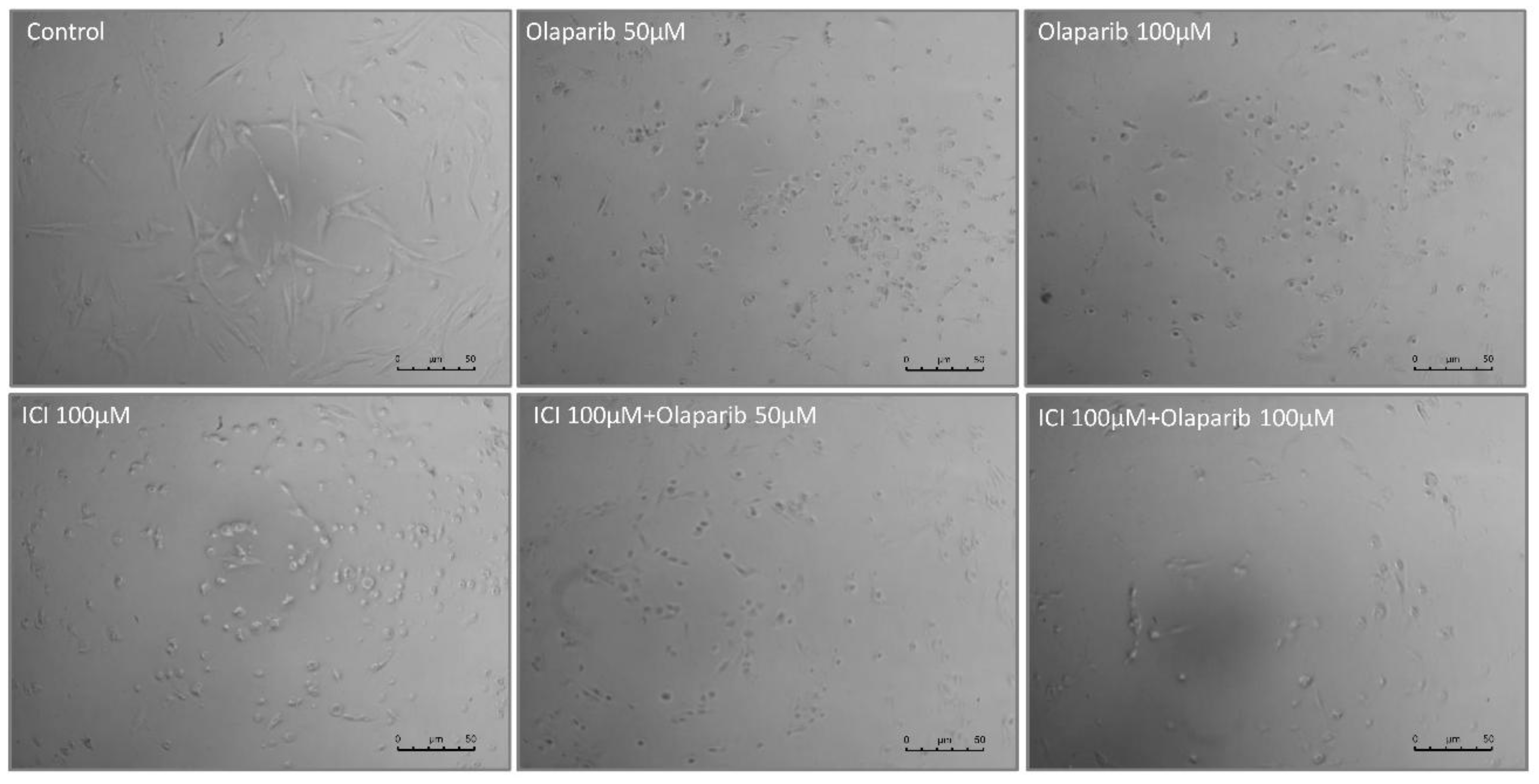

Thus, we decided to test the cell viability of the three different primary cultures from the patient last surgeries with 50 and 100µM Olaparib for 48 hours. Light microscopy images (

Figure 4) show the effect of Olaparib on the tumor cell morphology after 48 h of treatment. A notable decrease in the number of cells attached to the culture dish, especially at 100 M can be observed.

3.6. Treatment with ICI Alone and with the Combination ICI/Olaparib

Between 2015 and 2021, we have been showing that the treatment with ß-blockers of adrenergic receptors is effective in the reduction of Hb cell viability, and in their apoptosis induction [

16,

17,

18,

19]. The treatment of this patient cells with ICI, a specific blocker of the β2 adrenergic receptor reduced significantly the viability of the cells from the cultures of the last surgeries of this patient, to less than 50%, being the reduction stronger that the produced by Olaparib at the highest dose assayed (100 µM). The combination of both reduced cell viability to 25%, even with the lowest dose of Olaparib, in an additive effect. The viability decrease from untreated cells was statistically significant in all cases (

Figure 5).

The effects of both individual and combined treatments (

Figure 5A,B) were analyzed by t-test and ANOVA test for each Hb sample from the last three surgeries. In Hb24cib (first of the three), treatment with either Olaparib or ICI118,551 alone, as well as their combination, resulted in statistically significant differences compared to control (

Figure 5A,B;

Supplementary Table S1). In Hb38cib (second of the three), the single treatments again significantly reduced cell viability relative to the DMSO control. However, no significant differences were observed between the two Olaparib doses (50 and 100 µM). Similarly, in Hb73cib (last surgery), both Olaparib and ICI118,551 individually led to significant viability reduction, but no statistical differences were found between the two Olaparib doses.

4. Discussion

This study investigates the progression of a young patient with Von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) disease, characterized by an unusually aggressive and early onset of the disease, diverging from the typical VHL clinical progression. The patient has undergone an exceptional number of surgeries from a young age, with a notable difference in the disease phenotype compared to family members [

16]. Both, the patient and his sister inherited a complete deletion of one

VHL allele from the paternal line. While the sister has displayed mild clinical symptoms, the patient experienced a more severe form, suggesting that the aggressive phenotype in this case may be driven by additional factors beyond the typical

VHL mutation.

Previous genetic studies, including those analyzing DNA from the patient's hemangioblastoma (Hb) and peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL), identified a germline pathogenic mutation in the

CHEK2 gene [

16].

CHEK2 is a well-established tumor suppressor gene involved in DNA repair mechanisms. This mutation, inherited from the mother, coexists with the

VHL allele deletion, which raised the hypothesis that the

CHEK2 mutation might act as a "second hit" in the pathogenesis of this patient's disease, contributing to the frequent growth of hemangioblastomas.

To explore this further, we investigated the presence of a second hit in the VHL gene in various tumor samples from the patient's last surgeries. Interestingly, exomic analysis of the VHL gene did not reveal second-hit mutations in the coding regions, except for the last surgery, where a small deletion was identified in the second exon of VHL. This suggests that second hits in VHL may not always occur in exonic regions, but rather in regulatory or intronic regions, or possibly through epigenetic modifications such as hypermethylation, which remain undetectable by standard DNA sequencing techniques.

Western blot (WB) analysis from the most recent surgeries confirmed the complete loss of pVHL expression in hemangioblastoma cells, supporting the hypothesis that the second hit occurs in regulatory regions or through epimutations in the VHL gene. This finding highlights the complexity of VHL gene inactivation in tumor development, which cannot be fully explained by exomic mutations alone. Despite the CHEK2 mutation not acting as a direct second hit in the VHL gene, the clinical progression observed suggests that CHEK2 may act as a modifier, potentially triggering mutations in other genes such as PTEN and RB, which could accelerate tumor growth. These mutations, observed in earlier surgeries, along with the second exon deletion of VHL in the last surgery, imply a complex interplay of genetic events driving tumorigenesis in this patient.

The study also emphasizes the importance of personalized medicine in treating complex tumor diseases like VHL. Through the use of the PanDrugs software, which integrates the genetic mutations identified in the patient (

VHL and

CHEK2), Olaparib emerged as a promising therapeutic option. Olaparib, a PARP inhibitor, is FDA-approved for use in cancers with mutations in DNA repair genes, such as

BRCA and

CHEK2 [

18], and was found to effectively reduce cell division in hemangioblastoma cells from this patient. This finding suggests that Olaparib could be an effective strategy in treating tumors in VHL patients with an additional

CHEK2 mutation, targeting the defective DNA repair mechanisms.

In addition to Olaparib, previous research by our group has demonstrated that β-adrenergic receptor blockers, such as ICI118,551 (ICI), are effective in reducing tumor viability in hemangioblastomas and renal carcinomas in VHL patients [

20,

21]. The combination of Olaparib and ICI resulted in a nearly 80% reduction in cell viability in vitro, indicating a potential additive effect of both drugs, working independently of each other. This combination could provide a more effective therapeutic approach, targeting both DNA repair mechanisms and the β-adrenergic pathway, which is involved in tumor growth.

Although propranolol, a β-adrenergic receptor blocker, has shown efficacy in preventing retinal hemangioblastoma growth in VHL patients, its use is limited by side effects such as chronic hypotension, particularly in patients with concurrent β1-adrenergic receptor blockade [

20]. The ICI compound, which specifically blocks β2-adrenergic receptors without affecting β1 receptors, presents a promising alternative, potentially minimizing cardiovascular side effects [

20,

21,

22]. As demonstrated in this study, ICI could be an ideal candidate for clinical trials in VHL disease, particularly in combination with Olaparib, to delay the growth of existing tumors and prevent the formation of new ones.

In conclusion, this study highlights the complexity of VHL disease, especially in cases with additional germline mutations such as in CHEK2. The combination of Olaparib and ICI presents a promising therapeutic strategy, addressing both the genetic and molecular mechanisms underlying tumor progression in this patient. Further clinical trials are necessary to confirm the efficacy of this combination and its potential for broader application in VHL patients with similar genetic profiles.

5. Conclusions

1. Impact of Additional Mutations in Rare Diseases. The combination of mutations commonly found in the general population, such as CHEK2, with a rare disease like VHL, results in somatic alterations in Hb tumors within intronic or epigenetic regulatory regions that remain undetected by DNA germinal analyses. These changes play a critical role in triggering mutations in other tumor suppressor genes, such as PTEN and RB, which contribute to accelerated tumor growth. This highlights the necessity of comprehensive genetic screening of germinal and somatic tumor DNA that goes beyond exomic analysis to detect regulatory region mutations in rare disease cases.

2. Genetic Heterogeneity in Tumor Development. This study reveals the independence of genetic mutations across different hemangioblastomas within the same VHL patient, suggesting that distinct tumor mechanisms may drive tumor growth. The variability in genetic alterations across tumors reinforces the complexity of tumorigenesis in VHL patients and underlines the importance of analyzing multiple tumor samples to understand the full spectrum of genetic alterations involved.

3. Importance of Individualized Genetic Analysis. This case underscores the significance of personalized genetic analysis in rare diseases, especially when clinical manifestations deviate from typical disease progression. It emphasizes the need for in-depth genetic investigation to uncover additional mutations that may be responsible for the severity of the phenotype, enabling more precise diagnosis and therapeutic strategies.

4. Therapeutic Potential of Olaparib and ICI118,551 Combination. The combination of Olaparib (a PARP inhibitor) and ICI118,551 (a β2-adrenergic receptor blocker) demonstrated significant additive therapeutic effects in slowing tumor growth in vitro. This dual approach targets distinct molecular pathways involved in tumor proliferation, offering a promising strategy for the treatment of VHL-associated tumors, particularly in patients with additional mutations such as CHEK2. Further studies are needed to evaluate the clinical application of this combination therapy.

5. Need for Personalized Treatment Approaches. This work exemplifies the necessity of a personalized medicine approach, using patient-derived cells as models to tailor treatments. Such individualized strategies, which consider both genetic background and tumor characteristics, are essential not only for managing rare diseases like VHL but also for improving the treatment of common cancers, where personalized therapies could significantly enhance treatment outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: qPCR cycles (logarithmic phase) for HUVECs andHemangioblastomas; Figure S2: Viability of HB24cib, HB38cib and HB73cib under different treatments with Olaparib and ICI118,551. Table S1: 2 way Anova, Multiple comparisons.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M.B. and L.R.-L; methodology, V.A., C.S.M, D.T.A..; software, J.V.-L.; validation, L.M.B. and L.R.-L.; formal analysis, V.A., C.S.M, L.L.H, L.R.-P.; investigation, V.A., C.S.M., L.L.H., L.R.-P.; resources, L.M.B.; data curation, C.S.M., A.M.C., V.A., and D.T.A.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M.B. and V.A.; writing—review and editing, L.M.B., A.M.C., and V.A .; visualization, L.M.B and V.A.; supervision, L.M.B.; V.A., A.M.C.; project administration, L.M.B.; funding acquisition, L.M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by MICINN (Ministry of Science and Innovation of Spain), grant AEI/10.13039/501100011033 number PID2020-115371RB-I00 by FEDER and MICINN grant AEI number PID2023-146593OBI00.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Human Ethics Committee) of CSIC (National Research Council of Spain) for research involving human participants (protocol code 228/2020).

Informed Consent Statement

For the publication of this study, informed consent was acquired from the patient(s).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available in our laboratory records. DNA, RNA, cell culture, and tissue samples are part of the research collection associated with the group’s ongoing studies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VHL |

Von Hippel-Lindau |

CNS

Hb

ICI

ELST

VEGF

VEGF-R

mTOR

ccRCC

HIF

HUVEC

PARP

SSBs

BER

DSBs

HR

RPMI

PBL

WB

HRP

LOF

BRAF

PTPN11

RTqPCR

HUVEC

RB |

Central Nervous System

Hemangioblastoma

ICI-118,551

Endolymphatic Sac Tumors

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor

Mechanistic Target Of Rapamycin

clear cell Renal Cell Carcinoma

Hypoxic Inducible Factor

Human Umbilical Vascular Endothelial Cells

Poly [ADP-Ribose] Polymerase

Single-Strand Breaks

Base Excision Repair

Double-Strand Breaks

Homologous Recombination

Roswell Park Memorial Institute

Peripheral Blood Lymphocytes

Western Blot

Horseradish peroxidase

Loss Of Function

Murine Sarcoma Viral (V-Raf) Oncogene Homolog B1

Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Non-receptor type 11

Real Time quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells

Retinoblastoma |

References

- Gläsker, S.; Vergauwen, E.; Koch, C.; Kutikov, A.; Vortmeyer, A. 2020. Von Hippel-Lindau Disease: Current Challenges and Future Prospects. OncoTargets and Therapy 2020, 13, 5669–5690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feletti, A.; Anglani, M.; Scarpa, B.; Schiavi, F.; Boaretto, F.; Zovato, S.; Taschin, E.; Gardi, M.; Zanoletti, E.; Piermarocchi, S.; Murgia, A.; Pavesi, G.; Opocher, G. Von Hippel-Lindau disease: An evaluation of natural history and functional disability. Neuro-Oncology 2016, 18, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lonser, R.R.; Butman, J.A.; Huntoon, K.; Asthagiri, A.R.; Wu, T.; Bakhtian, K.D.; Chew, E.Y.; Zhuang, Z.; Linehan, W.M.; Oldfeld, E.H. J Neurosurg 2014, 120, 1055–1062.

- Lonser, R.R.; Butman, J.A.; Kiringoda, R.; Song, D.; Oldfeld, E.H. Pituitary stalk hemangioblastomas in von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Neurosurg 2009, 110, 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latif, F.; Tory, K.; Gnarra, J.; Yao, M.; Duh, F.M.; Orcutt, M.L.; Stackhouse, T.; Kuzmin, I.; Modi, W.; Geil, L.; et al. Identification of the von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor gene. Science 1993, 260, 1317–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.M.; Rhodes, L.; Blanco, I.; Chung, W.K.; Eng, C.; Maher, E.R.; Richard, S.; Giles, R.H. Von Hippel-Lindau Disease: Genetics and Role of Genetic Counseling in a Multiple Neoplasia Syndrome. J Clin Oncol 2016, 34, 2172–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, N.; Kebede, A.A.; Owusu-Dapaah, H.; Lather, J.; Kaushik, M.; Bhullar, J.S. A Review of Von Hippel-Lindau Syndrome. J Kidney Cancer VHL 2017, 4, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, J.; Neuhaus, C.; Macdonald, F.; Brauch, H.; Maher, E.R. Clinical utility gene card for: Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL). Eur J Hum Genet 2014, 22, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, H.P.; Wiestler, O.D. Clustering of features of von Hippel-Lindau syndrome: Evidence for a complex genetic locus. Lancet 1991, 337, 1052–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.M.; Zhuang, Z.; Chen, L.; Szerlip, N.; Maric, I.; Li, J.; Sohn, T.; Kim, S.H.; Lubensky, I.A.; Vortmeyer, A.O.; Rodgers, G.P.; Oldfeld, E.H.; Lonser, R.R. Von Hippel-Lindau disease-associated hemangioblastomas are derived from embryologic multipotent cells. PLoS Med 2007, 4, e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossage, L.; Eisen, T.; Maher, E. 2015. VHL, the story of a tumour supressor gene. Nature Reviews Cancer 2015, 1, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binderup, M.L.; Jensen, A.M.; Budtz-Jorgensen, E.; Bisgaard, M.L. Survival and causes of death in patients with von Hippel Lindau disease. J Med Genet 2017, 54, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choueiri, T.K.; Bauer, T.M.; Papadopoulos, K.P.; Plimack, E.R.; Merchan, J.R.; McDermott, D.F.; Michaelson, M.D.; Appleman, L.J.; Thamake, S.; Perini, R.F.; Zojwalla, N.J.; Jonasch, E. Inhibition of hypoxiainducible factor-2alpha in renal cell carcinoma with belzutifan: A phase 1 trial and biomarker analysis. Nat Med 2021, 27, 802–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palavani, L.B.; Camerotte, R.; Vieira Nogueira, B.; Ferreira, M.Y.; Oliveira, L.B.; Pari Mitre, L.; Coelho Nogueira de Castro, W.; Canto Gomes, G.L.; Fabrini Paleare, L.F.; Batista, S.; Fim Andreão, F.; Bertani, R.; Dias Polverini, A. Innovative solutions? Belzutifan therapy for hemangioblastomas in Von Hippel-Lindau disease: A systematic review and single-arm meta-analysis. J Clin Neurosci 2024, 128, 110774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de, R.o.j.a.s.-P.I.; Albiñana, V.; Recio-Poveda, L.; Rodriguez-Rufián, A.; Cuesta, Á.M.; Botella, L.M. CLN5 in heterozygosis may protect against the development of tumors in a VHL patient. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2020, 15, 132. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera-Montes, J.; Aguirre, D.; Viñas-López, J.; Lorente-Herraiz, L.; Recio-Poveda, L.; Albiñana, V.; Pérez Pérez, J.; Botella, L.; Cuesta, A. Mutation in CHEK2 triggers von Hippel-Lindau hemangioblastoma growth. Acta Neurochirurgica 2023, 165, 4241–4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro-Yáñez, E.; Reboiro-Jato, M.; Gómez-López, G.; Perales-Patón, J.; Troulé, K.; Rodríguez, J.M.; Tejero, H.; Shimamura, T.; López-Casas, P.P.; Carretero, J.; Valencia, A.; Hidalgo, M.; Glez-Peña, D.; Al-Shahrour, F. M.; Tejero, H.; Shimamura, T.; López-Casas, P.P.; Carretero, J.; Valencia, A.; Hidalgo, M.; Glez-Peña, D.; Al-Shahrour, F. PanDrugs: A novel method to prioritize anticancer drug treatments according to individual genomic data. Genome Med 2018, 10, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, J.; Chung, S.; Parakrama, R.; Fayyaz, F.; Jose, J.; Wasif, M. The role of PARP inhibitors in BRCA mutated pancreatic cancer. Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology 2021, 14, 17562848211014818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albiñana, V.; Villar Gómez de Las Heras, K.; Serrano-Heras, G.; Segura, T.; Perona-Moratalla, A.B.; Mota-Pérez, M.; de Campos, J.M.; Botella, L.M. Propranolol reduces viability and induces apoptosis in hemangioblastoma cells from von Hippel-Lindau patients. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2015, 10, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albiñana, V.; Escribano, R.M.J.; Soler, I.; Padial, L.R.; Recio-Poveda, L.; Villar Gómez de Las Heras, K.; Botella, L.M. Repurposing propranolol as a drug for the treatment of retinal haemangioblastomas in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2017, 12, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta, A.; Albiñana, V.; Gallardo-Vara, E.; Recio-Poveda, L.; de Rojas, I.; Villar, K.; Aguirre, D.; Botella, L. The β2-adrenergic receptor antagonist ICI-118,551 blocks the constitutively activated HIF signaling in hemangioblastomas from von Hippel-Lindau. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 10062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munabi, N.C.; England, R.W.; Edwards, A.K.; Kitajewski, A.A.; Tan, Q.K.; Weinstein, A.; Kung, J.E.; Wilcox, M.; Kitajewski, J.K.; Shawber, C.J.; Wu, J.K. Propranolol Targets Hemangioma Stem Cells via cAMP and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Regulation. Stem Cells Transl Med 2016, 5, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).