Ana B. Perona-Moratalla 1, Blanca Carrión 2,3, Karina Villar Gómez de las Heras 4, Lourdes Arias-Salazar 2,5, Blanca Yélamos-Sanz 2,5, Tomás Segura 1,5,6,* and Gemma Serrano-Heras 2,5,*

1 Department of Neurology, General University Hospital of Albacete, Street: Hermanos Falcó, 37, 02008 Albacete, Spain; abperona@gmail.com (A.B.P-M.)

2 Research Unit, General University Hospital of Albacete, Street: Laurel, 37, 02008 Albacete, Spain; blanca_carrion@hotmail.com (B.C.); Lourdesas.1230@gmail.com (L.A-S.); blanca.yelamos.sanz@gmail.com (B.Y-S.)

3 Universidad Europea de Madrid. Faculty of Medicine, Health and Sports. Department of Medicine

4 Emergency and Medical Transport Management, Castilla-La Mancha Health Service (SESCAM), Toledo, Spain; kvillar@jccm.es (K.V.G.H.)

5 Institute of Health Research of Castilla-La Mancha (IDISCAM), Castilla-La Mancha, Spain

6 Biomedicine Institute of UCLM (IB-UCLM), Faculty of Medicine, University of Castilla-La Mancha, Albacete, Spain

1. Introduction

Von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL) (OMIM 193300) is a dominantly inherited familial syndrome with an incidence that has been internationally reported to be 1 in 36,000 [

1]. This rare disease is caused by a heterozygous mutation or deletion in the VHL tumor suppressor gene located in the chromosome 3p25-p26 region [

2,

3]. This genetic alteration predisposes individuals to a variety of neoplasms with complete penetrance and variable expressivity, including retinal and central nervous system hemangioblastomas (CNS-HBs), renal cell carcinoma (RCC), pheochromocytomas (Pheo), paragangliomas, cystic and solid pancreatic lesions (comprising pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, pNETs), endolymphatic sac tumors, and broad ligament cystadenomas in women or epididymal cystadenomas in men [

4,

5,

6]. Four general VHL phenotypes (type 1, type 2A, type 2B, type 2C) have been suggested based on the likelihood of pheochromocytoma. VHL type 1 is characterized by a low risk for pheochromocytoma. Pathogenic truncating variants that are predicted to grossly disrupt the folding of the VHL protein or deletions are associated with VHL type 1. VHL type 2 is characterized by a high risk for pheochromocytoma. Individuals with VHL type 2 commonly have a pathogenic missense variant [

7,

8].

Multiple CNS hemangioblastomas, occurring either synchronously or metachronously, are common in VHL disease, with 60% to 80% of patients developing these tumors, except for those with type 2C VHL. Roughly 80% of these tumors develop in the brain (primarily in the cerebellum and brainstem), and 20% in the spinal cord. Growth patterns of CNS-HBs can be saltatory (72%), linear (6%), or exponential (22%) [

9]. Increased growth was associated with male sex, symptomatic tumors, hemangioblastoma-associated cysts, and germline VHL intragenic deletions [

10]. Hemangioblastomas typically present as benign, highly vascular tumors, often associated with cyst formation, and are composed of both stromal cells and numerous blood vessels formed by pericytes and endothelial cells [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. The etiopathogenesis of VHL-associated hemangioblastomas is driven by VHL gene mutations, which explains why these CNS tumors exhibit a unique microenvironment heavily influenced by hypoxia signaling [

17,

18,

19].

VHL mutations lead to the dysregulation of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. HIF-1α and HIF-2α are transcription factors that play key roles in the cellular response to hypoxia [

23,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Under low oxygen conditions, HIF-1α and HIF-2α are stabilized due to the loss of degradation signals. These factors then dimerize with HIF-β subunits (also known as ARNT) to form functional transcriptional complexes. The HIF-α/β heterodimers translocate to the nucleus, where they bind to hypoxia-responsive elements (HREs) in the promoters of target genes. In VHL-deficient cells, the absence of functional VHL protein prevents the degradation of both HIF-α isoforms [

20,

25,

30,

31,

32]. As a result, stabilized HIF-1α and HIF-2α lead to the overexpression of diverse factors, even under normal oxygen conditions. HIF-1α is broadly expressed in most cell types and is involved in acute responses to hypoxia, regulating genes associated with processes such as glycolysis, angiogenesis, and cell survival under hypoxic conditions. In contrast, HIF-2α has more restricted expression, being mainly found in tissues like the kidneys, liver, and vasculature. It regulates genes related to cell proliferation, differentiation, and erythropoiesis [

33,

34]. In VHL-deficient renal cell carcinoma (RCC), HIF-2α is the key oncogenic driver, although HIF-1α also supports tumor metabolism [

35,

36,

37]. On the other hand, the stabilization of both HIF-1α and HIF-2α in VHL-deficient hemangioblastomas has been suggested to drive the tumor's highly vascularized environment, supporting its growth and survival [

19,

38]. These findings underscore the critical roles of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in the development, progression, and vascularization of VHL-associated hemangioblastomas.

Although surgical resection remains the standard of care for CNS hemangioblastomas, excision may not be feasible depending on the tumor's location. In cases where a symptomatic tumor is nonresectable, stereotactic radiosurgery can offer short-term control [

39]. The recurrent manifestation of VHL-related tumors, along with the complications associated with repeated surgical interventions or the presence of unresectable tumors, makes CNS-HBs a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with VHL disease. For this reason, in the last decade, the development of pharmacological treatments as complementary strategy has gained increasing interest.

Recently, Belzutifan (Welireg™), a selective HIF-2α inhibitor, was approved for the treatment of advanced RCC, CNS hemangioblastomas, and pNET associated with VHL [

40,

41]. The response rate for CNS-HBs, which included both solid and cystic components, was 30%, with only 6% of patients achieving complete responses [

42]. This rate is lower than that observed in RCC (49%) and pNET (91%), possibly reflecting the distinct molecular characteristics of these tumors. The involvement of both HIF-1α and HIF-2α in tumor growth and vascularization may explain why selective HIF-2α inhibitors like Belzutifan show limited efficacy in VHL-deficient hemangioblastomas. In this context, we hypothesize that dual inhibition of HIF-1α and HIF-2α would be a more effective strategy to delay tumor progression and enhance therapeutic outcomes in CNS hemangioblastomas. Notably, targeting both HIF-α isoforms has been shown to promote cytotoxicity in glioblastoma cells, another brain tumor [

43,

44], where overexpression leads to increased proliferation and invasion [

45].

This study aims to analyze HIF-1α and HIF-2α mRNA and protein levels, as well as the isoform expression distribution among different cell components, in an in vitro CNS hemangioblastoma model based on patient-derived primary cell cultures. These cultures, which better preserve the genetic and phenotypic characteristics of the original tumor, allow for more reliable testing of potential therapeutic interventions. Hence, the effect of simultaneous HIF-1α and HIF-2α inactivation on cell survival, proliferation, cell cycle, and cell death triggering in primary HB cultures was further evaluated using acriflavine, a dual inhibitor that blocks the formation of active transcriptional complexes and reduces HIF transcriptional activity [

46,

47,

48]. This study seeks to enhance our understanding of the molecular basis of VHL, focusing on the combined role of HIFs in tumor progression, and potentially contribute to the development of novel pharmacological strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Recruitment, Clinical Data Collection, and Tissue Sampling of CNS Hemangioblastomas and Gliomas

Patients diagnosed with VHL disease who underwent neurosurgical procedures at the Jiménez Díaz Foundation Hospital, Madrid (Spain) for CNS-HBs were offered participation in the study. A total of 12 excess resected hemangioblastoma tissue samples were collected from 11 patients (one patient underwent two surgeries). Concurrently, glioma tumor samples, for use as controls in cellular and molecular experiments, were obtained post-surgery from 3 patients diagnosed with astrocytoma, gliosarcoma, and glioblastoma, respectively, by the Neurology and Neurosurgery departments of the General University Hospital of Albacete, Spain. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. All procedures were approved by the Human Ethics Committees of both hospitals (Ethical approval numbers: 2014/2 and 03/2014). Sociodemographic data (sex and age) and clinical information, including genetic profile (deletion, nonsense, or missense mutation of the VHL gene), central nervous system location of the hemangioblastoma, and synchronous or metachronous appearance of other lesions assessed by radiographic examinations, were collected (see table 1). Immediately after resection, fresh tissue samples were placed in Earle's Balanced Salt Solution (EBSS, Gibco) cell culture medium, which maintains cell viability, and transported at room temperature to the Research Unit, General University Hospital of Albacete, within 6 hours.

2.2. Protocol for Establishing Primary Cell Cultures of CNS Hemangioblastomas and Gliomas and Use of Immortalized Cell Lines

Upon receipt of tissue samples from 11 CNS hemangioblastomas and 3 gliomas (astrocytoma, gliosarcoma, and glioblastoma) at Hospital of Albacete, we applied the method for the establishment and growth of patient-derived primary cell cultures, as previously described by our group [

49]. It is worth noting that these primary cultures were obtained for the first time, as no studies with HB cells derived from patients had been earlier described in the literature. Briefly, tumor samples were washed multiple times with PBS and cut into 1 mm³ pieces. Tissue pieces were then transferred using sterile tweezers to clean cell culture dishes (Sarstedt, Germany) and subjected to enzymatic digestion with an equal volume of collagenase I and dispase II, both at a final concentration of 1 mg/mL in EBSS, for 45 minutes at 37°C. Subsequently, the pieces were completely disaggregated by gentle pipetting and further digested with trypsin for 15 minutes at 37°C. The minced samples were then centrifuged, and the resulting cell pellets were resuspended in growth medium (RPMI 1640 (Gibco) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 5 mM glutamine) and incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO₂ incubator. The medium was replaced every 72 hours until the cultures reached confluence. Cells were then detached using 0.25% trypsin and subcultured in cell plates with fresh proliferative medium for subsequent cellular and molecular experiments.

In addition to the primary glioma cultures, immortalized cell lines were also used as controls. SW48 (derived from a human colorectal adenocarcinoma) and ARPE-19 (derived from the human retinal pigment epithelium) cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Virginia, USA (ATCC CCL-231 and CRL-2302, respectively). SW48 and ARPE cells were maintained in the same media conditions as those for patient-derived cell cultures: RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 20% FBS, 1% P/S, and 5 mM glutamine at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

2.3. Cell Profiling and Analysis of HIF-α Isoform Protein Expression: Flow Cytometry and Western Blot

First, HIF-1α and HIF-2α protein expression was determined by flow cytometry in the 9 successfully established primary hemangioblastoma cultures (HB2, HB3, HB4, HB7, HB8, HB9, HB10, HB11, HB12—clinical characteristics shown in

Table 1) and 5 controls: 3 primary glioma cell cultures (astrocytoma, gliosarcoma, and glioblastoma) and SW48 and ARPE-19 cell lines. All cells were harvested at a density of 0.3 x 106 cells and centrifuged. The resulting cell pellets were resuspended in PBS and incubated with fluorophore-conjugated antibodies that specifically recognize the membrane markers of each cell type present in HB (phenotypic characterization): anti-CD99-APC (stromal cells) (Immunostep S.L #99A-100T-cloneHI156), anti-NG2-FITC (pericytes) (Thermo Fisher Scientific #18646693-clone:7.1) , and anti-CD34-PE-Cy7 (endothelial cells) (Immunostep S.L #34PC7-100T-CUSTOM-clone 581) for 2 hours at room temperature in the dark. Following a wash, the cells were fixed with Intracellular Reagent A (Immunostep S.L. #INTRA-100T) for 15 minutes, washed again with PBS, and permeabilized with Intracellular Reagent B (Immunostep S.L. #INTRA-100T). Subsequently, the cells were incubated with either anti-HIF-1α-PE (Immunostep S.L # HIF1PE-015mg-CUSTOM-cloneH1alpha67) or anti-HIF-2α-PE (Immunostep S.L.#HIF2PE-01mg-CUSTOM-clone ep190b) antibodies for 1 hour in the dark. Finally, the cells were centrifuged, the supernatant was removed, and the cells were resuspended in 400 µL of PBS for analysis using a FACS Canto II flow cytometer with FACS DIVA software. These antibodies yielded data on the percentage of cells expressing HIF-1α or HIF-2α in the primary cultures of CNS-HB and gliomas, and in the immortalized human cell lines. Moreover, in the case of the HB cells, it was possible to determine the cellular distribution of endothelial, pericyte, and stromal cells in the primary cultures and the HIF-α isoform expression profile among the different cellular components.

In parallel, total proteins were extracted using RIPA buffer (Merck #R0278-500ml) from 7 primary hemangioblastoma (HB) cell cultures (HB2, HB3, HB4, HB7, HB8, HB9, HB10; HB11 and HB12 yielded insufficient cells), 2 primary glioma cell cultures (astrocytoma and glioblastoma), and the SW48 cell line, all grown to a density of 0.8-1 x 106 cells (equivalent to confluence in 100 mm culture dishes). The protein concentration was determined by a BCA assay. Subsequently, protein extracts (20-30 µg) were separated using denaturing SDS-PAGE polyacrylamide gels and transferred to PVDF membranes (Hybond-C Extra, Amersham Biosciences). A Spectra™ Multicolor Broad Range Protein Ladder (Thermo Fisher Scientific #26634) was utilized as a molecular weight marker. The primary antibodies used were anti-HIF-1α and anti-HIF-2α (Santa Cruz), and anti-tubulin as a loading control. Chemiluminescence detection was achieved using SuperSignal™ West Dura (Thermo Fisher Scientific #34075) on a Luminescent Image Analyzer LAS-mini 4000 system (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).

2.4. RNA Isolation and Real-Time RT-PCR Analysis

The mRNA levels of HIF-1α and HIF-2α were determined as follows: Total RNA was extracted using the QIAshredder and RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN #79654, #74104) from the same primary HB cultures analyzed by Western blot, 2 primary glioma cell cultures (astrocytoma and glioblastoma), and the SW48 cell line, all grown to a density of 0.8-1 x 106 cells (equivalent to confluence in 100 mm culture dishes). RNA was quantified by spectrophotometry using a NanoDrop ND-100. Subsequently, cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of extracted RNA using the RevertAid™ Minus First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific #K1632), which includes dNTPs, random hexamers, oligo(dT) primers, and reverse transcriptase. Real-time PCR was then performed on the cDNA using the SYBR Green PCR Kit (Applied Biosystems #4385612) and a STEP ONE PLUS system (Applied Biosystems). mRNA levels were normalized to tubulin and quantified using the 2-ΔΔCT method to determine relative gene expression. The sequences of the primers used were:

HIF-1α: Forward:5′-ACTTCTGGATGCTGGTGATT-3′, Reverse:5′-TCCTCGGCTAGTTAGGGTAC-3′

HIF-2α: Forward:5′-CAACCTCAAGTCAGCCACCT-3´, Reverse:5′-TGCTGGATTGGTTCACACAT-3′

β-Tubulin: Forward:5′-CTTCGGCCAGATCTTCAGAC-3′, Reverse: 5′- AGAGAGTGGGTCAGCTGGAA -3′

2.5. Cell Viability

Cell viability and proliferative activity were determined using the colorimetric MTT (3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay according to the manufacturer's instructions. Primary hemangioblastoma (HB) cell cultures, showing moderate (HB2, HB3, HB8) and high (HB7, HB9, HB10) HIF-1α/2α levels, were seeded at a density of 0.4 x 105 cells in duplicate into 24-well plates and incubated in 500 µL of RPMI medium supplemented with 20% FBS, 5 mM glutamine, and increasing concentrations (1 µM, 2.5 µM, 5 µM, 10 µM, 25 µM, 50 µM, 100 µM) of acriflavine purified (≥95%HPLC, Mixture of trypaflavines: 3,6-diamino-10-methylacridinium chloride and 3,6-diamino-3-methylacridinehydrochloride, and proflavine:3,6-diaminoacridine hydrochloride)(Merck #SML3350). Following 24, 48, and 72-hour incubations, MTT solution (5 mg/mL) (Merck # M2128) was added and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. The medium was subsequently aspirated, and a solubilization solution was added to dissolve the resulting formazan crystals. The MTT assay relies on the reduction of MTT to formazan by metabolically active cells. The amount of formazan produced, as measured by the absorbance at 570 nm using a microplate reader (SPECTROstar Omega, BMG LABTECH), is directly proportional to the number of viable cells. The percentage of cell viability was then calculated relative to untreated control cells

2.6. Cell Cycle Analysis and Apoptosis/Necrosis Assays

Moderate-high HIF-overexpressing primary HB cultures (HB2, HB3, HB7, HB8, HB9, HB10) were seeded in duplicate in 60 mm culture dishes and grown to a density of 0.3 x 106 cells, then exposed to 2.5 µM and 25 µM acriflavine or PBS-vehicle for 24 hours. Subsequently, cells were harvested, washed with PBS, fixed, and permeabilized using a cold fixative solution containing ethanol to preserve their DNA content and allow access of staining reagents to the DNA. The cells were then incubated with propidium iodide (PI)(10mg/ml) (Thermo Fisher Scientific-Molecular probes #P1304MP), a DNA-binding dye that intercalates with DNA in a stoichiometric manner, meaning the amount of dye bound is directly proportional to the amount of DNA. To determine the distribution of cells across the cell cycle phases (G0/G1, S, and G2/M), the PI-stained cells were analyzed using flow cytometry. The collected data were analyzed using FACS DIVA software to determine the percentage of cells in each phase of the cell cycle and to generate histograms.

In addition, to assess acriflavine-triggered cell death, these HB cultures (at a density of 0.3 x 10^6 cells per sample) were treated in duplicate with acriflavine at doses of 2.5 µM and 25 µM, or with a PBS-vehicle control, for 48 hours. Following treatment, cells were harvested, centrifuged, and resuspended in 450 µL of 1X Annexin V binding buffer (Immunostep S.L. #BB10X-50ml). The cells were then stained with 10 µL of Annexin V conjugated to Dy-634 (Immunostep S.L. #ANXDY-200T) and 40 µL of PI (10mg/ml) (Thermo Fisher Scientific-Molecular probes #P1304MP) for 1 hour in the dark. Cell death analysis was performed using a FACS Canto II flow cytometer. Early apoptotic cells (Annexin V-positive, PI-negative), late apoptotic cells (Annexin V-positive, PI-positive), and necrotic cells (Annexin V-negative, PI-positive) were quantified and represented using FACS DIVA software

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22. Statistical significance was assessed using Student’s t-test for two-group comparisons to analyze the transcriptional activity of HIF-1α or HIF-2α in each primary HB cell type, relative to SW48 carcinoma cells. Additionally, statistical analysis was performed on the cell viability assay (MTT) using Student’s t-test for two-group comparisons to evaluate each concentration of acriflavine treatment compared to untreated cells at each incubation time (24, 48, and 72 hours).

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics and Genetics of the Patient Cohort

The study cohort consisted of 11 VHL patients who underwent CNS hemangioblastoma resection. Our study is based on a total of 12 HB samples, as one patient experienced two surgeries, providing tumor specimens from both procedures (HB3 and HB7).

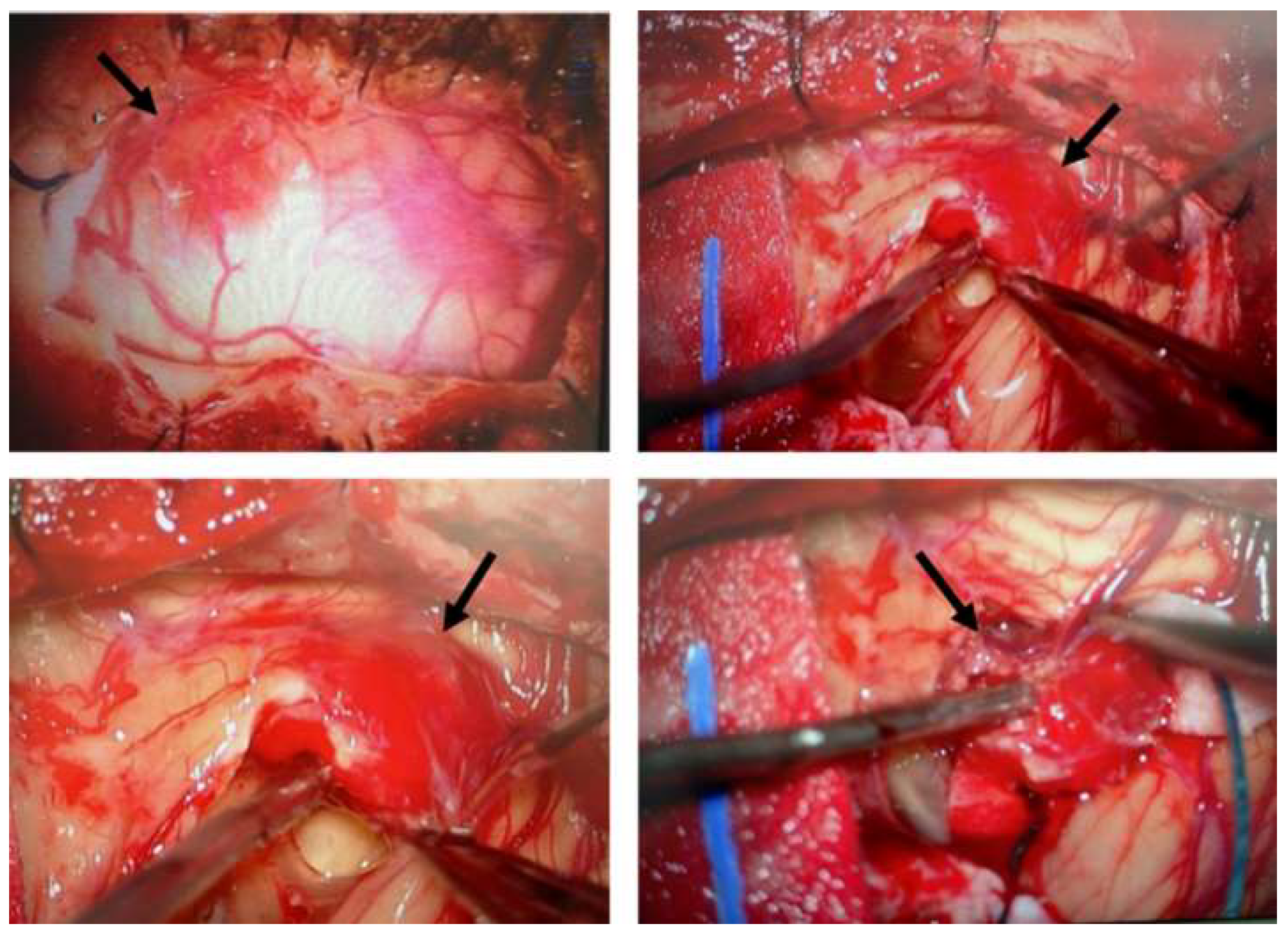

Figure 1 illustrates the surgical removal of HB8 located in the cerebellum. As is commonly observed with this type of tumor, the lesion is highly vascularized. The images show different stages of the surgical procedure, highlighting the identification and initial dissection steps, making the tumor accessible for subsequent complete resection.

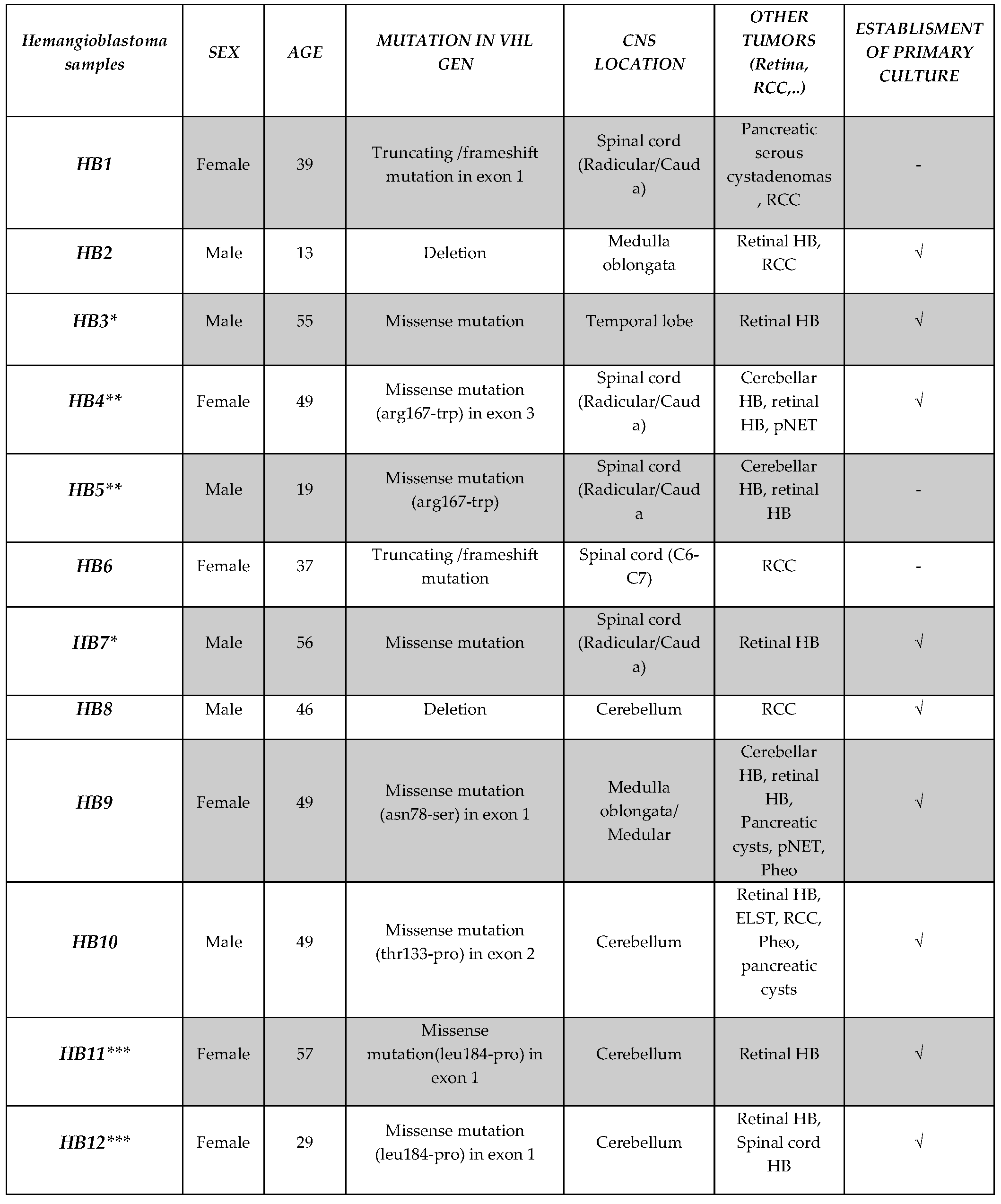

Disease-related features of the enrolled patients with VHL are shown in

Table 1. The cohort consisted of 5 males and 6 females, with ages ranging from 13 to 57 years. Genetic analysis revealed that mutations in the VHL gene were identified in all of the patients, with missense mutations being the most frequent (7/11, 63.6%). Other mutations included truncating/frameshift mutations (2/11, 18.2%) and deletions (2/11, 18.2%). At the time of surgery, hemangioblastoma locations varied, with most lesions found in the spinal cord region, including radicular/cauda and medulla oblongata (7/12, 58.3%), followed by the cerebellum (4/12, 33.3%) and the temporal lobe (1/12, 8.3%). Clinical record reviews indicated that patients HB4, HB5, HB9, and HB12 presented with additional CNS-HBs either concurrently or at different times. In addition, patients presented a variety of other VHL-associated tumors. Retinal tumors were common, observed in 7 of the 11 patients (63.63%). Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) was observed in 4 patients (33.3%). Other tumors included pancreatic cysts (2 patients), pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNET) (2 patients), pheochromocytomas (2 patients), and endolymphatic sac tumors (ELST) (1 patient). Based on available clinical data at the time of writing this article and the genetic characteristics of the patient cohort, we could potentially classify the VHL patients into different subtypes. Type 1, characterized by a low risk of pheochromocytoma and associated with truncating mutations or deletions in the VHL gene, would include patients HB1, HB2, HB6, and HB8. Type 2, associated with a high risk of pheochromocytoma and commonly linked to missense mutations, can be further divided into subtypes. Type 2B, associated with both pheochromocytoma and renal cell carcinoma (RCC), would comprise patients HB4, HB5, HB7, HB9, HB10, HB11, and HB12. Type 2A, with high pheochromocytoma risk but low RCC risk, and Type 2C, with high pheochromocytoma risk but low CNS hemangioblastoma risk, were not clearly represented in our cohort. Patient HB3, with a missense germinal mutation but no reported pheochromocytoma.

* CNS hemangioblastomas collected from the same patient, ** mother and son *** aunt and niece. Abbreviations: RCC: Renal Cell Carcinoma, HB: Hemangioblastoma, pNET: Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor, Pheo: Pheochromocytoma.

3.2. Establishment, Cell Characterization, and HIF-Alpha Expression of Primary CNS Hemangioblastoma Cultures

To better understand the role of the HIF-α isoforms in VHL-associated CNS-HBs, we determined the levels of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in patient-derived cell cultures using cellular and molecular techniques. To this end, we first proceeded with the establishment of primary cultures from CNS-HB samples collected post-surgery, as described by our group [

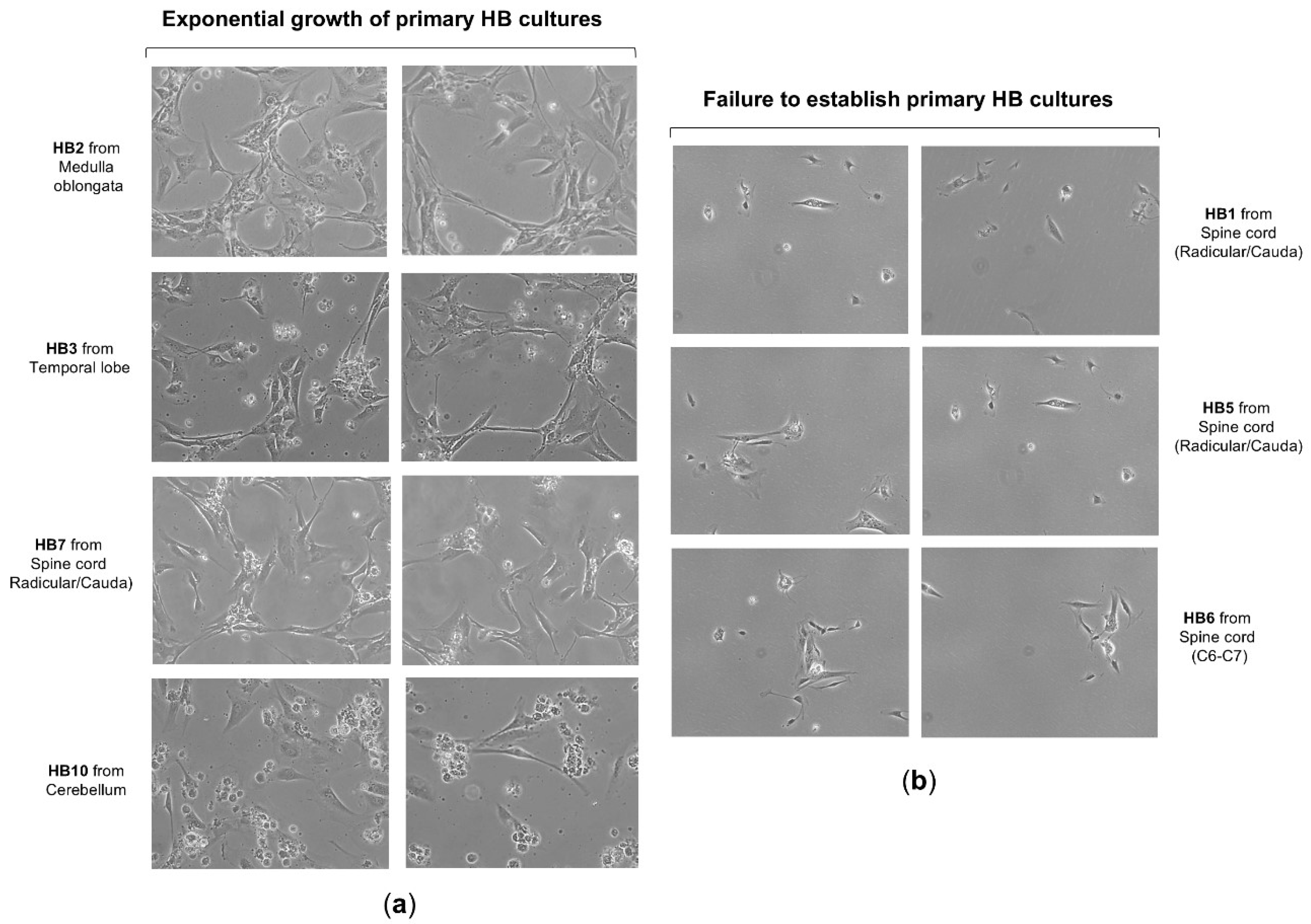

49] and briefly outlined in the Materials and Methods section. Notably, 9 primary cell cultures derived from a total of 12 CNS hemangioblastoma tumor samples, obtained immediately post-surgical resection and transported to the cell culture laboratory in EBSS solution within 6 hours, were successfully established (75% success rate), allowing subsequent in vitro investigations. These patient-derived HB cells grew in a monolayer and mainly exhibited a fusiform shape, but also, to a lesser extent, a polygonal shape (

Figure 2a), reaching 80% cell confluence (with an estimated doubling time of 86-96 hours), equivalent to approximately 1.2-1.5 x 10⁶ cells within 3-4 weeks. The primary HB cultures continued proliferating until the 11th to 14th generation, after which cell growth ceased, and the cultured cells died within 6–8 weeks. While the cell morphology was similar, the growth rate was slower than that reported in previous work [

50]. In contrast, the lifespan of our primary HB cells was extended, allowing cultures to proliferate for more than 2 weeks, which exceeded the time reported by those authors, potentially due to variations in culture medium and materials. On the other hand, despite all these tumor samples being carefully maintained under the same appropriate conditions to ensure their viability for primary cells establishment, HB1, HB5, and HB6 were unable to grow and quickly entered the senescence phase, dying a few days later (

Figure 2b). Although these CNS hemangioblastomas were all derived from a spinal cord location, it is unlikely that the failure of hemangioblastoma growth was due to this, as 2 other samples, HB4 and HB7, were removed from the spinal cord and successfully grew to confluence. The challenge in establishing these three cultures was probably related to the small initial size of the samples, which measured less than 0.3 cm x 0.4 cm, while the successfully growing samples were larger than 0.5 cm x 0.5 cm.

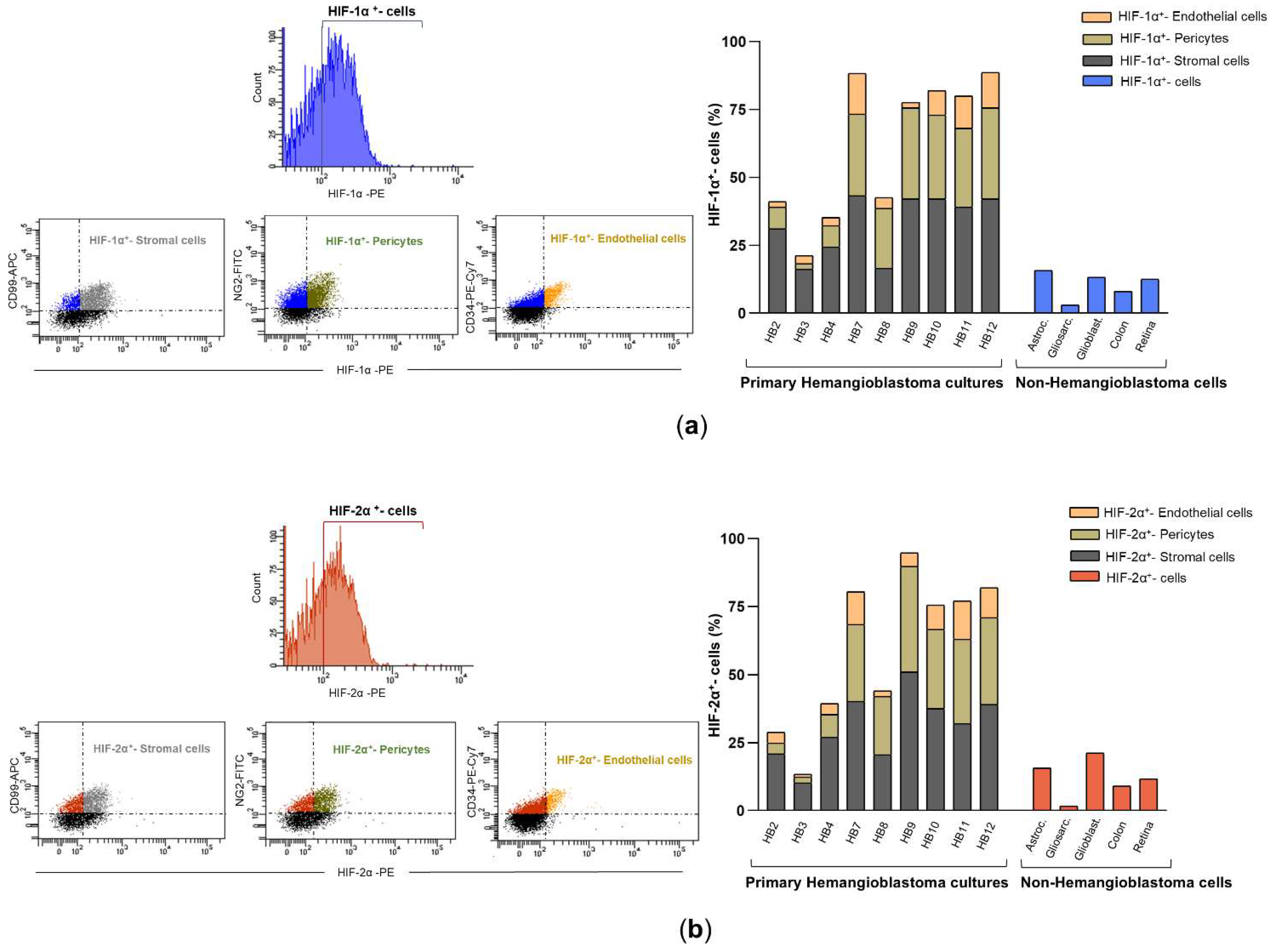

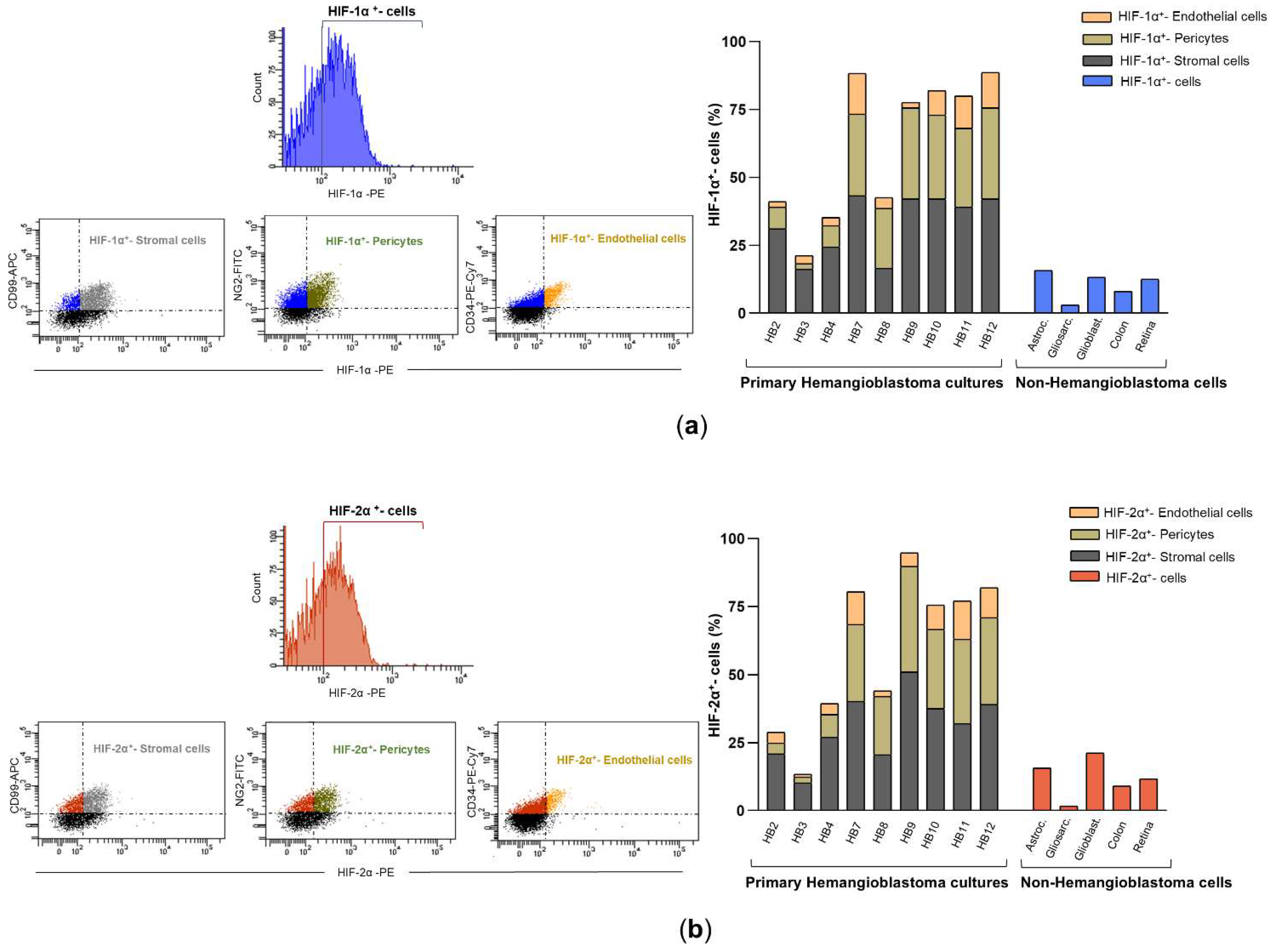

Next, the 9 continuously growing HB cells were incubated with specific membrane markers for stromal cells, pericytes, and endothelial cells and analyzed by flow cytometry to confirm the presence of well-known cell components of CNS hemangioblastomas. As expected, the results showed that the primary HB cultures contained roughly 35-45% stromal cells, 25-40% pericytes, and 5-15% endothelial cells. This cellular analysis technique was further used to determine the percentage of cells expressing HIF-1α and HIF-2α in the primary HB cultures (

Figure 3a), compared to those present in primary cultures derived from other brain tumors (astrocytoma, gliosarcoma, and glioblastoma), as well as in the SW48 (colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line) and ARPE-19 (immortalized human retinal pigment epithelium) cell lines. As shown in

Figure 3b, the percentage of cells positive for HIF-1α and HIF-2α varied among the different hemangioblastoma (HB) cells, indicating some heterogeneity in hypoxia-related protein expression. Nevertheless, in all primary HB cultures, the levels of HIF-1α and HIF-2α expression were significantly higher than in non-hemangioblastoma cells, with a slightly higher proportion of cells showing positivity for HIF-1α compared to HIF-2α. Specifically, HB7 and HB9, derived from the spinal cord and medulla oblongata, respectively, and HB10, HB11, and HB12, derived from the cerebellum, exhibited the highest percentages of cells with intracellular synthesis of HIF-1α (85%-90%) and HIF-2α (80%-85%). In contrast, HB3, cultured from the temporal lobe, showed the lowest levels of both markers (22.1% for HIF-1α and 14.7% for HIF-2α). The remaining cultures, HB2, HB4, and HB8, derived from the medulla oblongata, spinal cord, and cerebellum, respectively, presented intermediate expression levels, displaying 40%-50% and 35%-45% of HIF-1α and HIF-2α positive cells. When comparing these values with non-hemangioblastoma cell lines, the expression of HIF-1α and HIF-2α was markedly lower in gliosarcoma cells (3% and 1.7%, respectively) and SW48 colorectal carcinoma cells (8.1%-1.9% for HIF-1α and 9.1%-4.4% for HIF-2α), while increased levels were observed in astrocytoma, glioblastoma, and ARPE-19 cell lines. Although the crucial role of hypoxia-inducible factors in mediating tumor progression in astrocytic tumors or in adapting to the high metabolic demand of the retina has been reported, these cells did not reach the high levels of HIF positivity detected in most HB cells in this study (

Figure 3b). Subsequently, we found that the HIF-1α expression profile among the different cellular components of all primary HB cultures was similar, with stromal cells showing the highest positivity for the protein, reaching 35-45%, followed by pericytes (20-30%). Endothelial cells exhibited lower expression across all cultures, ranging from 2.2% to 15%. Likewise, HIF-2α was mainly expressed in stromal cells and pericytes, with low levels detected in endothelial cells (

Figure 3b). These results indicate that hypoxia-inducible factors are predominantly expressed in stromal and pericytic cells of patient-derived HB cultures, suggesting a potential role for these cell populations in the hypoxic response of hemangioblastomas and, consequently, in tumor progression.

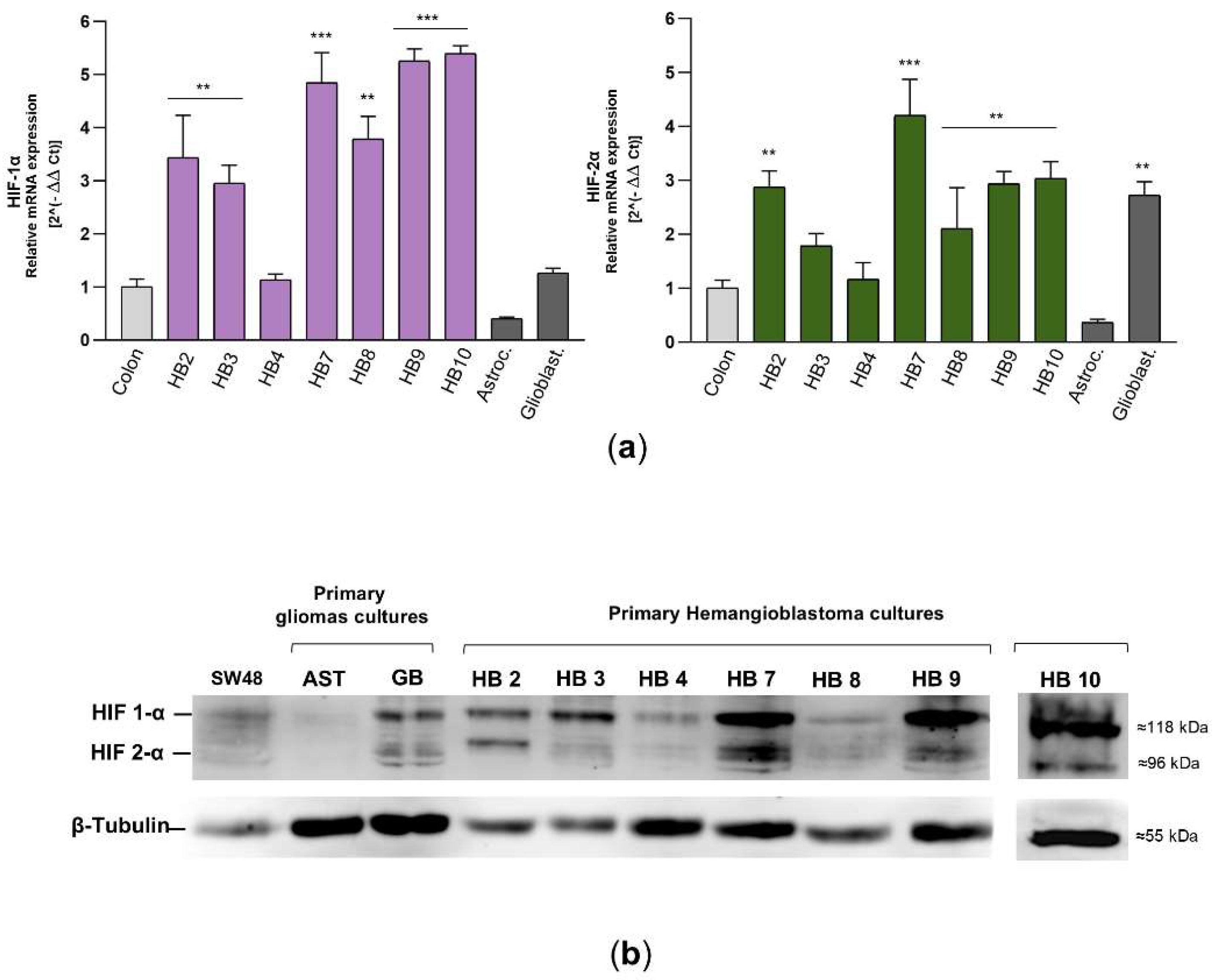

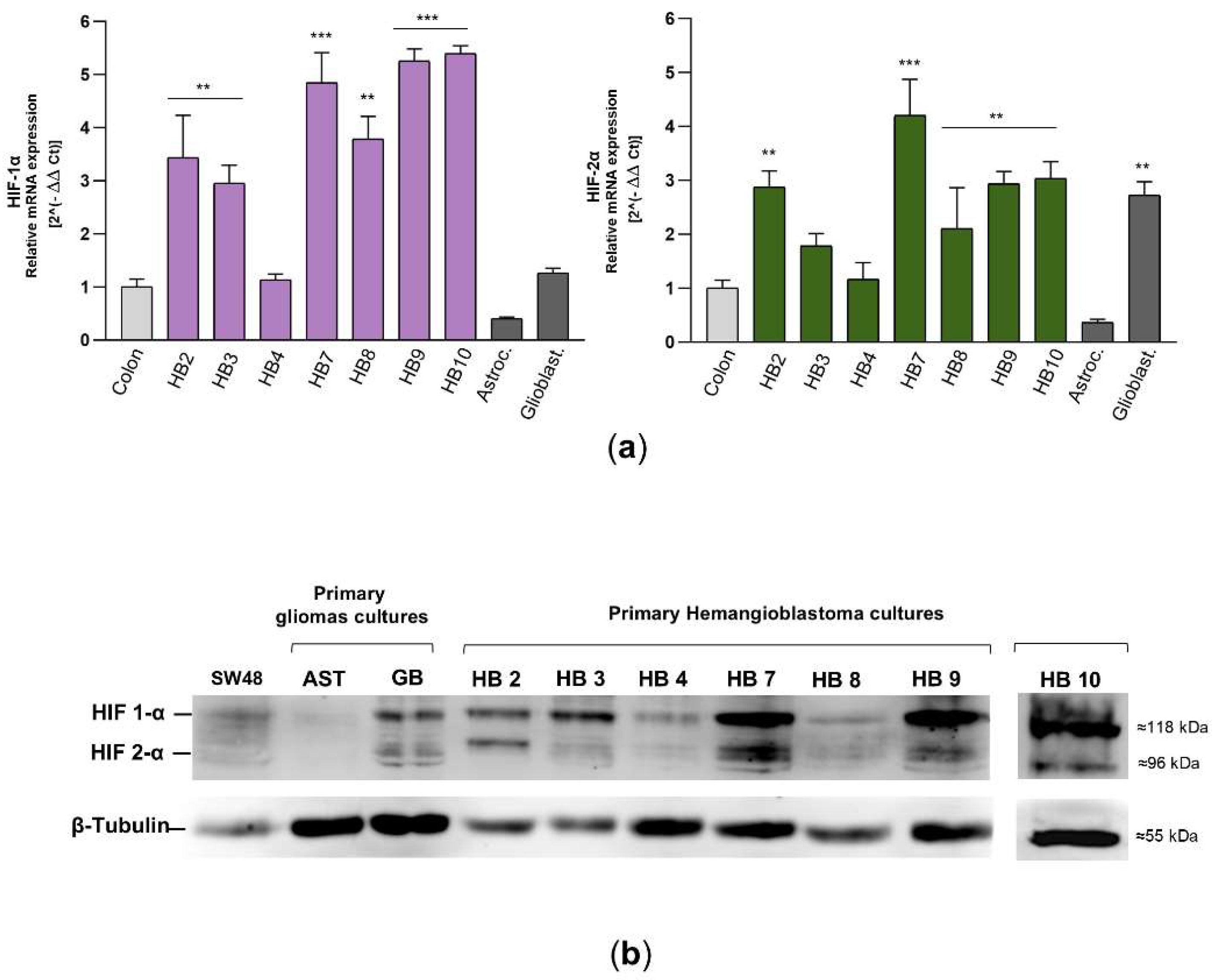

Finally, mRNA and protein levels of HIF-1α and HIF-2α were determined in 7 primary HB cultures, as HB11 and HB12 did not exhibit sufficient growth for molecular experiments and subsequent acriflavine exposure. As depicted in

Figure 4a, HB7, HB9, and HB10 demonstrated the highest transcriptional levels of HIF-1α and HIF-2α, approximating a 5-fold increase compared to the levels observed in SW48 colorectal carcinoma cells, which served as a control. HB2, HB3, and HB8 also showed significantly elevated expression, with values surpassing 3-fold those of the SW48 cell line. By contrast, HB4 displayed lower levels, remaining proximate to baseline. Primary cultures of astrocytoma and glioblastoma exhibited moderate expression of HIF- α isoforms, though not at the same magnitude as in the majority of HB cultures. Western blot analysis confirmed the findings from the mRNA expression evaluation and the flow cytometry data concerning the proportion of HIF-positive cells. HIF-1α and HIF-2α protein levels were markedly elevated in HB7, HB9, and HB10, while HB2, HB3, and HB8 showed moderate amount of these hypoxia-inducible factors (

Figure 4b). Both experimental approaches revealed a slight to moderate trend towards increased HIF-1α expression.

Together, these cellular and molecular assay results indicate that over 85% of the primary CNS-HB cultures derived from patients with VHL disease exhibit moderate to high overexpression of HIF-1α and HIF-2α, independent of tumor localization within the CNS. This suggests that the robust hypoxic response observed in hemangioblastomas, as evidenced by the elevated levels of HIF-α isoforms, may be associated with microenvironmental adaptation and tumor development and progression.

3.3. Growth Suppression, Cell Cycle Arrest, and Necrosis Induction by Acriflavine

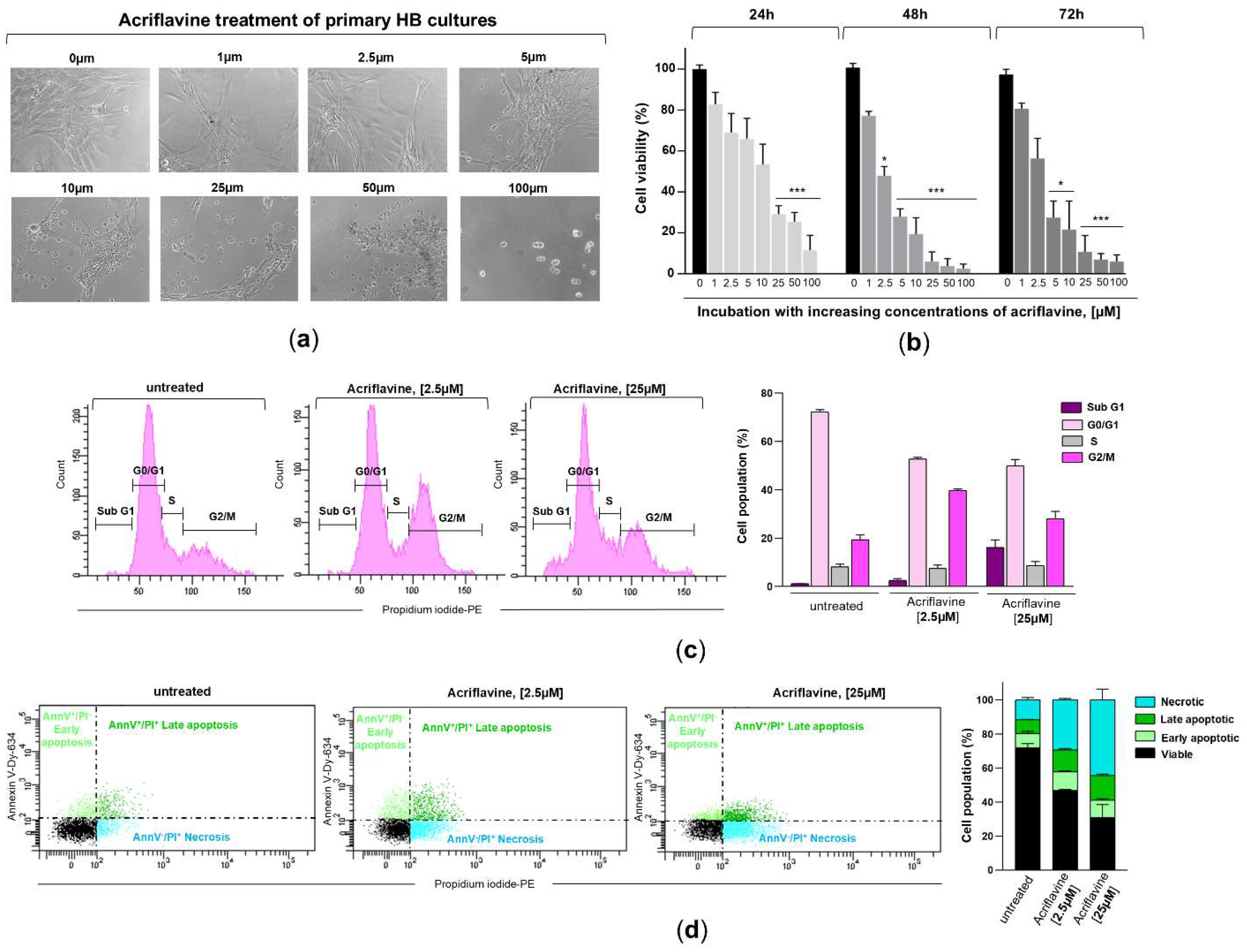

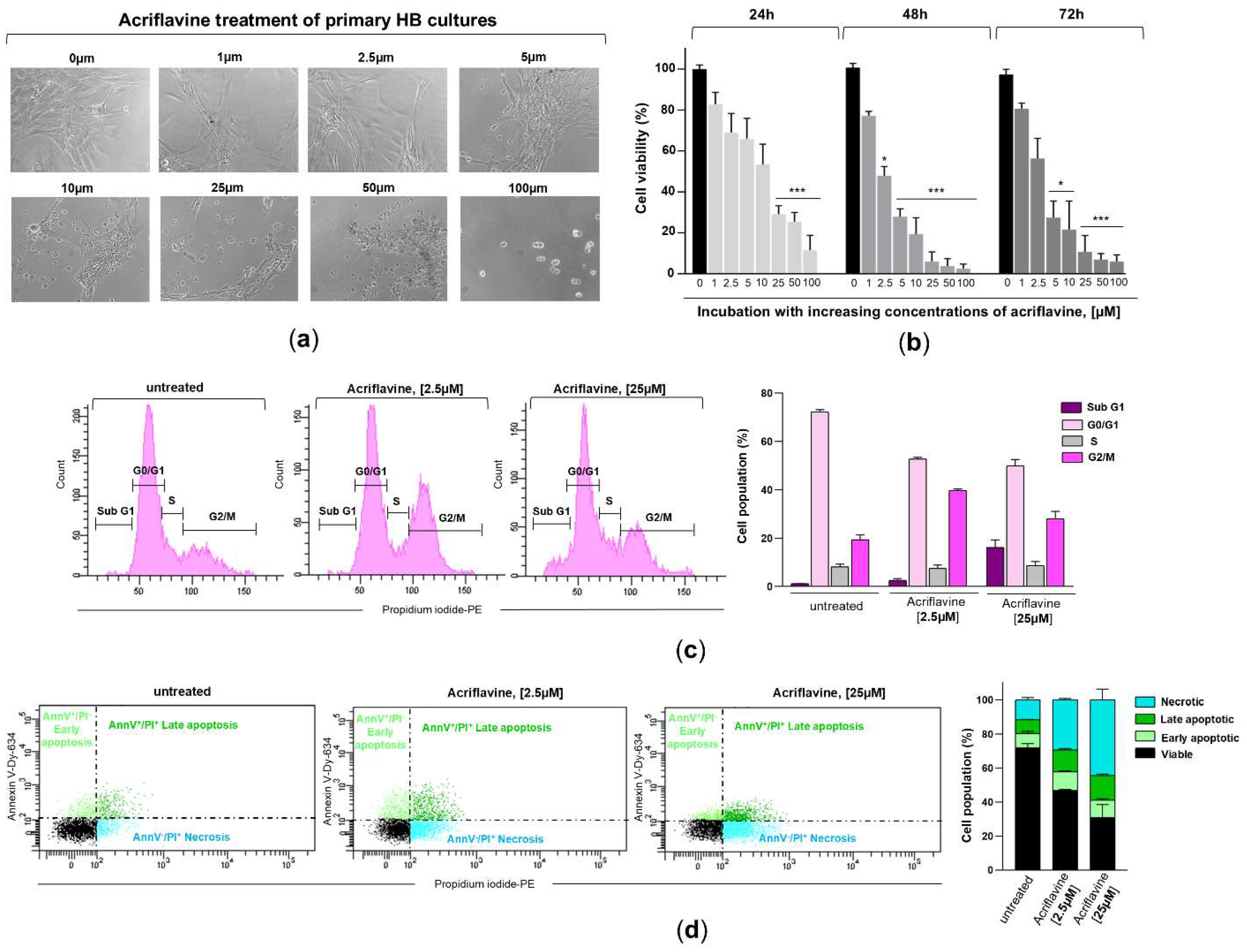

To evaluate novel pharmacological approaches for limiting the proliferation and growth of CNS hemangioblastomas, patient-derived primary tumor cultures were subsequently incubated with acriflavine, a drug that blocks the binding of HIF-α isoforms to the β subunit, thereby inhibiting HIF transcriptional activity. After treating HB cells, exhibiting moderate (HB2, HB3, and HB8) to high (HB7, HB9, and HB10) overexpression of HIF-1α and HIF-2α, with increasing concentrations of acriflavine (1 µM to 100 µM), optical microscopy analysis revealed significant structural and morphological alterations (

Figure 5a). Cells became rounded and clustered in response to treatment with 5-10 µM of the drug for 24 hours. At higher concentrations (25-100 µM), cells exhibited signs of severe stress, including shrinkage, loss of adhesion, and cell death. Using the MTT assay, which measures metabolic activity as an indicator of cell viability, we found that acriflavine in the culture medium led to a notable, dose- and time-dependent reduction in cell growth in these 6 primary HB cultures. Acriflavine significantly reduced cell survival and proliferation, with viability dropping below 50% at low concentrations (2.5-5 µM) within 48-72 hours, highlighting its strong cytotoxic effect (

Figure 5b). These results, along with microscopic observations, indicate that acriflavine effectively suppresses hemangioblastoma growth in vitro.

To gain further insight into the effect of acriflavine on cell cycle regulation and cell death, primary HB cells with moderate to high HIF-α overexpression were treated with 2.5 and 25 µM of the inhibitor for 24 hours. The cells were then stained with the DNA-intercalating agent propidium iodide and analyzed by flow cytometry. The results showed that blocking HIF transcriptional activity induced cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase, with a considerable increase in cells containing duplicated DNA that struggled to complete mitosis and continue dividing. Specifically, the percentage of cells in the G0/G1 phase (resting or pre-synthesis DNA phase) decreased from 72.3±0.85% in untreated cells to 52.7±0.71% and 49.9±2.69% in cells treated with 2.5 µM and 25 µM acriflavine, respectively. Meanwhile, the S phase (DNA replication phase) remained relatively stable, with 8.25±1.06%, 7.55±1.34%, and 8.75±1.63% in untreated, 2.5 µM-, and 25 µM-treated cells, respectively. Interestingly, a significant accumulation of cells was observed in the G2/M phase (pre-mitosis phase), increasing from 19.45±1.91% in untreated cells to 39.75±0.64% and 28.05±3.04% in those treated with 2.5 µM and 25 µM acriflavine, respectively. Exposure to the highest dose also led to the detection of cells in the subG1 phase, with 16.15±3.04%, which have a lower DNA content than cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle, a phenomenon typically associated with dead or dying cells (

Figure 5c). This suggests that acriflavine interferes with normal cell cycle progression, acting as an anti-mitotic agent and potentially contributing to its anti-proliferative effects.

Evaluation of the impact of HIF inactivation on hemangioblastomas was completed by assessing the type of cell death induced by acriflavine. To this end, hemangioblastoma cultures HB2, HB3, HB7, HB8, HB9, and HB10 were treated with acriflavine for 48 hours, followed by propidium iodide and Annexin V-APC staining, and analyzed by flow cytometry. As shown in

Figure 5d, acriflavine exposure led to a slight increase in both early (11.1±0.57% and 10.35±0.78%) and late apoptosis (12.85±0.85% and 14.5±0.71%), and a strong increase in dead cells positive for propidium iodide but negative for Annexin V (29.3±0.3% and 44.3±6.22%) at low and high doses compared to untreated primary HB cells, which displayed a proportion of early and late apoptotic cells and necrotic cells of 8.45±1.06%, 8±0.14%, and 11.55±1.2%, respectively. These findings demonstrate that acriflavine exerts a potent cytotoxic and antiproliferative effect on primary HB cultures in a dose-dependent manner, leading to G2/M cell cycle arrest and the induction of necrosis.

4. Discussion

The standard treatment for hemangioblastomas associated with VHL disease remains surgical resection, despite the risk of neurological sequelae. However, due to the recurrent nature of VHL-related tumors and the risks associated with multiple surgeries, there is a rising interest in developing pharmacological treatments as a complementary strategy. Belzutifan (Welireg™), a HIF-2α inhibitor, is the only FDA-approved non-surgical option, but it has demonstrated only a 30% partial response rate in patients with CNS hemangioblastomas [

42]. To explore alternative molecular targets as potential non-invasive therapeutic strategies, we established primary cell cultures from CNS hemangioblastomas of VHL patients undergoing surgery. Cellular and molecular analyses revealed overexpression of both HIF-α isoforms in HB cells, with HIF-1α levels slightly higher than HIF-2α. Interestingly, treatment of the patient-derived HB cultures with acriflavine, an inhibitor of HIF-α/β heterodimer formation and consequently HIF transcriptional activity, resulted in a reduction in cell viability by more than 50% due to G2/M cell cycle arrest and increased necrosis. These findings suggest that dual inhibition of HIF-1 and HIF-2 could represent a promising therapeutic approach for VHL-associated hemangioblastomas.

Despite the challenges inherent to the benign nature of these tumors, such as the slow proliferation rate of stromal, pericyte, and endothelial cells and the scarcity of published studies on primary HB cultures [

50], we achieved successful establishment of primary HB cultures from 9 of 12 tumor samples, representing a 75% success rate. Cell profiling of the proliferating primary HB cultures revealed a predominance of stromal cells, followed by pericytes, with a smaller proportion of endothelial cells. These results are in agreement with previous phenotypic characterizations of VHL-related hemangioblastomas [

19,

50,

51], which identified three main cell types: stromal cells, the most abundant and which would be essential for tumor growth; pericytes, which would contribute to vascular stability; and endothelial cells, which, although less numerous, could play a crucial role in vessel formation in these highly vascularized tumors. Moreover, we observed that over 85% of VHL patient-derived HB cells displayed moderate to high overexpression of HIF-1α and HIF-2α. Of note, the remaining 15%, despite exhibiting lower HIF-α isoform levels compared to most HB cultures, still exhibited elevated levels relative to glioblastoma cells, thus suggesting the significant involvement of both hypoxia-inducible factors in CNS hemangioblastoma formation and growth. These results are consistent with prior molecular and immunohistochemical research performed on tumor samples of CNS HB reporting increased HIF-α isoform levels [

17,

38] and elevated expression of HIF target genes like EGFR, TGF-α, and VEGF [

52,

53]. It is noteworthy that our results reveal that HIF-1α protein levels were higher than HIF-2α in primary HB cell cultures, a pattern that differs from that exhibited by renal cell carcinoma (RCC) carrying VHL-defective genes. In an in vitro model of VHL-null RCC, it has been found that transcriptional activity favors HIF-2α over HIF-1α, resulting in a distinct bias of alpha isoform expression toward HIF-2α [

31]. Additionally, immunohistochemical analysis of nephrectomy specimens from VHL patients showed that HIF-1α expression is evident in the earliest detectable lesions, even in single tubular cells, whereas HIF-2α upregulation becomes significantly stronger in cystic and malignant lesions [

54]. In this line, Kondo et al. [

55] provided evidence that downregulation of HIF-2α using short hairpin RNAs was sufficient to suppress tumor formation in pVHL-defective renal carcinoma cells, reinforcing HIF-2α's role as a major driver of VHL-associated RCC tumor development.

Currently, there is no effective pharmacological treatment capable of completely inhibiting HB growth. Therefore, as previously mentioned, surgical excision continues to be the treatment of choice for CNS hemangioblastomas. Although recent advancements in microsurgical techniques have significantly reduced mortality rates from 50% to 24%, the risk remains substantial as this procedure is performed in the core of the CNS on tumors with a strong tendency to bleed. To reduce the need for operative procedures and its associated complications, researchers emphasize the urgent need for noninvasive therapeutic alternatives effective in limiting tumor progression. Clinical trials involving patients with VHL disease and unresectable HBs have historically explored the use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (targeting genes from the VEGFR, PDGFR, and EGFR families, which are regulated by the HIF pathway), such as semaxanib, vatalanib, sunitinib, and pazopanib, as well as monoclonal anti-VEGF antibodies (bevacizumab). However, the results have not been sufficiently robust to justify the widespread clinical application of these drugs [

56,

57,

58,

59]. Accordingly, in the last decade, HIF inhibition has become a primary focus of current research efforts. In this context, previous findings, together with our results, which collectively reveal differential expression of HIF-1α and HIF-2α between CNS-HBs and RCC, suggest that therapeutic strategies targeting the HIF system should consider isoform-specific expression patterns in each VHL-associated tumor type. Therefore, considering the HIF-1α and HIF-2α overexpression distribution, the simultaneous inhibition of HIF-1α and HIF-2α may provide a more effective strategy for reducing the proliferative capacity of CNS-HBs compared to the use of selective HIF-2α inhibitors alone. This theory would explain the observed 30% partial response rate of Belzutifan in VHL-associated hemangioblastomas [

42], while this drug and PT2385, a first-generation HIF-2α inhibitor [

55], demonstrated clinical efficacy in VHL patients with renal cell carcinoma (RCC) [

40,

41,

60].

Given the limited efficacy of selective HIF-2α inhibition in CNS hemangioblastomas, our study explores a broader therapeutic approach by targeting both HIF-1α and HIF-2α simultaneously. Unlike Belzutifan, which exclusively inhibits HIF-2α, acriflavine disrupts the dimerization of both HIF isoforms, effectively blocking their transcriptional activity. This mechanism is particularly relevant for VHL-associated hemangioblastomas, where both HIF-1α and HIF-2α are significantly overexpressed, as demonstrated in our primary patient-derived culture. Our group previously observed [

49] that propranolol treatment reduced the expression of both HIF-1α and HIF-2α proteins in primary CNS-HB cultures, leading to cytotoxicity. However, the inhibitory activity of this drug on the alpha isoforms was not direct; rather, it exerts its effects indirectly by blocking β-adrenergic receptors, preventing cAMP signaling, and subsequently reducing PKA-mediated phosphorylation of Src, which ultimately affects the stabilization of HIF-1α and HIF-2α, lowering their levels. Therefore, it was not possible to confirm whether HIF-1/2 α inhibition was the main cause of cell death in HB cells, given that propranolol, a beta-adrenergic blocker, acts on several pathways. For this reason, in this study, we chose to use acriflavine (ACF) because it directly inhibits HIF, and it has been recognized as the most potent direct HIF inhibitor among the 336 drugs approved by the FDA. In addition, it is a low-cost, water-soluble, and commercially available molecule. Originally used as an antiseptic agent a century ago, with a well-documented safety record [

61], it has recently been shown to be effective against a broad spectrum of cancers (glioblastoma, osteosarcoma, breast, lung, liver, colon, ovarian, and pancreatic cancers, leukemia, and melanoma) [

46,

47]. It also exerts an impact on the immune system, promoting the infiltration of NK and CD8+ T cells into the tumor microenvironment [

62]. Moreover, research in murine models of oxygen-induced ischemic retinopathy has shown that ACF, administered intraocularly or intraperitoneally, effectively inhibits retinal neovascularization and diminishes the expression of HIF-1-responsive genes in a dose-dependent manner [

48]. Our results reveal that ACF treatment resulted in a significant reduction in cell viability in primary HB cultures, with a mean inhibitory concentration 50% (IC50) ranging from 2.5 to 5 μM, similar to the IC50 reported for the cytotoxic effect of ACF in glioblastoma cell lines [

43,

44]. Surprisingly, HB cell death induced by this dual HIF-α inhibitor was mainly via necrosis, in contrast to that reported for glioblastomas, which underwent apoptosis as the main type of cell death after ACF incubation. This discrepancy in cell death pathways between hemangioblastoma and glioblastoma cells following ACF exposure may rely on the differential dependencies on HIF signaling for cell survival and proliferation. As we showed in this study, primary hemangioblastoma cultures produce higher levels of HIF-α isoforms than primary glioblastoma cells. Thereby, the abrupt disruption of this pathway by acriflavine could rapidly deplete the cell's energy source, which might trigger a cascade of events that favor necrosis, as apoptosis is an ATP-dependent process.

Hence, together these results suggest that dual inhibition of HIF-1α and HIF-2α could be a promising non-invasive strategy for the treatment of VHL-associated hemangioblastomas or as a complementary therapy to surgery. Moreover, the therapeutic use of dual HIF-α isoform inhibition in VHL-related tumors would have several clinical advantages. First, since HIF-1α and HIF-2α participate in interconnected signaling pathways, both proteins could compensate for each other in certain situations, such as selective inhibition of HIF-2α, which can trigger the activation of HIF-1α expression. Therefore, dual inhibition prevents this functional redundancy. Second, many tumors develop resistance to single inhibitors. In fact, in the VHL context, acquired resistance to HIF-2 antagonists has been reported in preclinical studies of PT2399 and in clinical studies of PT2385/MK-3475 (Phase 1) and PT2977 (Belzutifan) [

40,

63,

64], underscoring the necessity of more comprehensive strategies to overcome resistance in HIF-2-targeted therapies. While Belzutifan selectively binds to the PAS-B domain of HIF-2α [

65], exploiting subtle structural differences with the corresponding domain of HIF-1α, acriflavine interacts with common sites in both the PAS-A and PAS-B domains of both HIF isoforms, thereby preventing their dimerization with HIF-1β. Thus, dual targeting could reduce the risk of resistance by simultaneously disrupting HIF pathways. It is worth mentioning that the structure of ACF small molecule has allowed for the development of optimized formulations enabling sustained drug release for the treatment of various pathologies. Acriflavine was incorporated into poly-lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA)-formulated microparticles, which showed efficacy for long-term suppression of choroidal neovascularization [

66]. Very recently, Korelidou et al. [

67] reported the preparation and optimization of 3D-printed ACF-loaded reservoir-type implants, demonstrating antitumor effects against glioblastoma. Additionally, ACF is a low-cost, commercially available compound with a well-established safety profile, originally used as an antimicrobial agent [

61]. These factors make it an attractive candidate for repurposing in oncology, particularly for rare diseases such as VHL. Finally, the availability of an alternative inhibitor to Belzutifan for treating CNS hemangioblastomas could facilitate the development of combination therapies, potentially exerting a synergistic effect in reducing tumor growth. This approach could enable a reduction in Belzutifan dosage, thereby reducing its most common adverse effects, such as decreased hemoglobin levels (with anemia occurring in 90% of patients, 7% of whom experience Grade 3 anemia), fatigue, increased creatinine, headache, dizziness, hyperglycemia, and nausea [

57,

60,

68].

Several limitations should be taken into account in this study. While primary hemangioblastoma cultures were successfully established from 9 out of 12 tumor samples from patients diagnosed with VHL, a low-prevalence disease, the sample size remains small. Future studies with larger samples may offer more detailed insights to identify all cellular targets of acriflavine and assess their contribution to treatment efficacy, as well as to investigate its selectivity for hemangioblastoma cells over normal cells. Additionally, comparative studies between the HIF-2α selective inhibitor and acriflavine would provide valuable information. On the other hand, this study offers preclinical evidence supporting acriflavine's therapeutic potential for VHL-associated hemangioblastomas, based on patient-derived cell cultures, which are better at preserving original tumor characteristics than established cell lines. However, they do not fully replicate the complex in vivo tumor microenvironment, potentially affecting treatment response. Thus, in vivo studies like patient-derived xenografts or genetically modified mouse models could provide more relevant acriflavine efficacy data, opening the possibility for the development of clinical trials to confirm these findings and evaluate acriflavine's safety and efficacy in patients.

5. Conclusions

Our results reveal that HIF-1α and HIF-2α are overexpressed in primary hemangioblastoma cultures, and that their simultaneous transcriptional activity inactivation by acriflavine led to a relevant reduction in cell viability and proliferation, and increased necrotic cell death. The findings of this study suggest that dual inhibition of HIF-1 and HIF-2 may offer a non-invasive therapeutic strategy for managing VHL-associated hemangioblastomas.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and Investigation, A.B.P.-M., T.S. and G.S.-H.; Methodology, Data curation and Formal Analysis, A.B.P.-M., B.C., K.V.G.H., L.A-S., B.Y-S., T.S. and G.S.-H.; Writing—original draft preparation, A.B.P.-M., T.S. and G.S.-H.; Supervision and Funding acquisition, T.S. and G.S.-H. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

Lourdes Arias-Salazar and Blanca Yélamos-Sanz are the recipients of contracts funded by the Programa Investigo (2022-2025) of the Recovery, Transformation, and Resilience Plan (Next Generation European Funds) and managed by the Fundación Hospital Nacional de Parapléjicos-Institute of Health Research of Castilla-La Mancha (IDISCAM). Gemma Serrano-Heras is the recipient of a contract funded by the grant awarded to the project 'Reinforcement of the Research Activity of Castilla-La Mancha (EMER) (Fundación Hospital Nacional de Parapléjicos-Institute of Health Research of Castilla-La Mancha (IDISCAM), Castilla-La Mancha, Spain). This study received funding from the ”Strategies for Rare Diseases” line of the Ministry of Health, Social Services, and Equality, according to the agreement of the Interterritorial Council of the National Health System (SNS) for the distribution of funds to the Autonomous Communities.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures were approved by the Human Ethics Committees of both hospitals (Ethical approval numbers: 2014/2 and 03/2014) and were performed in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants to perform the investigation and to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to the patients who participated in this study and generously donated tumor samples. Their invaluable contribution made this research possible. The authors also wish to acknowledge Dr. José María Campos, of the Neurosurgery Department at the Jiménez Díaz Foundation Hospital, Madrid, Spain, for his invaluable support and assistance in the collection of CNS hemangioblastoma tumor samples. We are also grateful to the VHL Alliance for their dedication to improving the lives of individuals affected by VHL disease. Finally, we would like to thank Hernán Sandoval, Daniel García-Pérez, and Christoph J. Klein-Zampaña of the Neurosurgery Department at the General University Hospital of Albacete for collaborating in this research by providing tumor glioma samples used as controls.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Louise, M.; Binderup, M.; Smerdel, M.; Borgwadt, L.; Beck Nielsen, S.S.; Madsen, M.G.; et al. von Hippel-Lindau disease: Updated guideline for diagnosis and surveillance. Eur J Med Genet 2022, 65, 104538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seizinger, B.R.; Rouleau, G.A.; Ozelius, L.J.; Lane, A.H.; Farmer, G.E.; Lamiell, J.M.; et al. Von Hippel–Lindau disease maps to the region of chromosome 3 associated with renal cell carcinoma. Nature 1988, 332, 268–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latif, F.; Tory, K.; Gnarra, J.; Yao, M.; Duh, F.-M.; Orcutt, M.L.; et al. Identification of the von Hippel-Lindau Disease Tumor Suppressor Gene. Science 1993, 260, 1317–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, E.R.; Yates, J.R.W.; Harries, R.; Benjamin, C.; Harris, R.; Moore, A.T.; et al. Clinical Features and Natural History of von Hippel-Lindau Disease. QJM 1990, 77, 1151–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, E.R.; Neumann, H.P.; Richard, S. von Hippel–Lindau disease: A clinical and scientific review. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 19, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonser, R.R.; Glenn, G.M.; Walther, M.; Chew, E.Y.; Libutti, S.K.; Linehan, W.M.; et al. von Hippel-Lindau disease. The Lancet 2003, 361, 2059–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.M.; Rhodes, L.; Blanco, I.; Chung, W.K.; Eng, C.; Maher, E.R.; et al. Von Hippel-Lindau Disease: Genetics and Role of Genetic Counseling in a Multiple Neoplasia Syndrome. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 2172–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, M.P.; Feldman, J.; Mirzaa, G.M.; NLM Citation: van Leeuwaarde, R.S.; Ahmad, S.; van Nesselrooij, B. et al. Von Hippel-Lindau Syndrome Synonyms: VHL Disease, VHL Syndrome, Von Hippel-Lindau Disease Summary Clinical characteristics. 1993.

- Takami, H.; Graffeo, C.S.; Perry, A.; Brown, D.A.; Meyer, F.B.; Burns, T.C.; et al. Presentation, imaging, patterns of care, growth, and outcome in sporadic and von Hippel–Lindau-associated central nervous system hemangioblastomas. J. Neurooncol. 2022, 159, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonser, R.R.; Butman, J.A.; Huntoon, K.; Asthagiri, A.R.; Wu, T.; Bakhtian, K.D.; et al. Prospective natural history study of central nervous system hemangioblastomas in von Hippel-Lindau disease. J. Neurosurg. 2014, 120, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, A.M.; Rubinstein, L.J. Cerebellar capillary hemangioblastoma: Its histogenesis studied by organ culture and electron microscopy. Cancer 1975, 35, 326–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Zhou, L.; Tan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, J. Histologic and histogenetic investigations of intracranial hemangioblastomas. Surg. Neurol. 2007, 67, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, J.E.; Chou, D.; Clatterbuck, R.E.; Brem, H.; Long, D.M.; Rigamonti, D. Hemangioblastomas of the Central Nervous System in von Hippel-Lindau Syndrome and Sporadic Disease. Neurosurgery 2001, 48, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishizawa, K.; Komori, T.; Hirose, T. Stromal cells in hemangioblastoma: Neuroectodermal differentiation and morphological similarities to ependymoma. Pathol. Int. 2005, 55, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, D.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, M.; Ding, X.; Xu, F.; Hua, W.; et al. Identification of tumorigenic cells and implication of their aberrant differentiation in human hemangioblastomas. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2011, 12, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovic, D.; Selimovic, E.; Kuharic, M.; Splavski, B.; Rotim, K.; Arnautovic, K.I. Understanding Adult Central Nervous System Hemangioblastomas: A Systematic Review. World Neurosurg. 2024, 191, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagzag, D.; Zhong, H.; Scalzitti, J.M.; Laughner, E.; Simons, J.W.; Semenza, G.L. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in brain tumors. Cancer 2000, 88, 2606–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnaluri, V.K.C.; Vavilala, D.T.; Prakash, S.; Mukherji, M. Hypoxia mediated expression of stem cell markers in VHL-associated hemangioblastomas. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 438, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagzag, D.; Krishnamachary, B.; Yee, H.; Okuyama, H.; Chiriboga, L.; Ali, M.A.; et al. Stromal Cell-Derived Factor-1α and CXCR4 Expression in Hemangioblastoma and Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma: von Hippel-Lindau Loss-of-Function Induces Expression of a Ligand and Its Receptor. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 6178–6188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domene, C.; Illingworth, C.J.R. Effects of point mutations in pVHL on the binding of HIF-1α. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Bioinf. 2012, 80, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razafinjatovo, C.; Bihr, S.; Mischo, A.; Vogl, U.; Schmidinger, M.; Moch, H.; et al. Characterization of VHL missense mutations in sporadic clear cell renal cell carcinoma: hotspots, affected binding domains, functional impact on pVHL and therapeutic relevance. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; Lee, J.-H.; Lee, K.E.; Kim, J.H.; Hong, J.M.; Ra, E.K.; et al. Genotype-phenotype analysis of von Hippel-Lindau syndrome in Korean families: HIF-α binding site missense mutations elevate age-specific risk for CNS hemangioblastoma. BMC Med. Genet. 2016, 17, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroka, D.M.; Burkardt, T.; Desbaillets, I.; Wenger, R.H.; Neil, D.A.H.; Bauer, C.; et al. HIF-1 is expressed in normoxic tissue and displays an organ-specific regulation under systemic hypoxia. FASEB J. 2001, 15, 2445–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapitsinou, P.P.; Haase, V.H. The VHL tumor suppressor and HIF: Insights from genetic studies in mice. Cell Death Differ. 2008, 15, 650–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haase, V. The VHL Tumor Suppressor: Master Regulator of HIF. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2009, 15, 3895–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loboda, A.; Jozkowicz, A.; Dulak, J. HIF-1 and HIF-2 Transcription Factors - Similar but Not Identical. Mol. Cells 2010, 29, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L. HIF-1, O2, and the 3 PHDs. Cell 2001, 107, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon, W.C.; Wilson, M.I.; Harlos, K.; Claridge, T.D.W.; Schofield, C.J.; Pugh, C.W.; et al. Structural basis for the recognition of hydroxyproline in HIF-1α by pVHL. Nature 2002, 417, 975–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.-J.; Wang, L.-Y.; Chodosh, L.A.; Keith, B.; Simon, M.C. Differential Roles of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1α (HIF-1α) and HIF-2α in Hypoxic Gene Regulation. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 23, 9361–9374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unwith, S.; Zhao, H.; Hennah, L.; Ma, D. The potential role of HIF on tumour progression and dissemination. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, 2491–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieg, M.; Haas, R.; Brauch, H.; Acker, T.; Flamme, I.; Plate, K.H. Up-regulation of hypoxia-inducible factors HIF-1α and HIF-2α under normoxic conditions in renal carcinoma cells by von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene loss of function. Oncogene 2000, 19, 5435–5443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, K.; Klco, J.; Nakamura, E.; Lechpammer, M.; Kaelin, W.G. Inhibition of HIF is necessary for tumor suppression by the von Hippel-Lindau protein. Cancer Cell 2002, 1, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallio, P.J.; Wilson, W.J.; O’Brien, S.; Makino, Y.; Poellinger, L. Regulation of the Hypoxia-inducible Transcription Factor 1α by the Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 6519–6525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmeliet, P.; Dor, Y.; Herbert, J.-M.; Fukumura, D.; Brusselmans, K.; Dewerchin, M.; et al. Role of HIF-1α in hypoxia-mediated apoptosis, cell proliferation and tumour angiogenesis. Nature 1998, 394, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Gao, P.; Fukuda, R.; Kumar, G.; Krishnamachary, B.; Zeller, K.I.; et al. HIF-1 Inhibits Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Cellular Respiration in VHL-Deficient Renal Cell Carcinoma by Repression of C-MYC Activity. Cancer Cell 2007, 11, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefflin, R.; Harlander, S.; Schäfer, S.; Metzger, P.; Kuo, F.; Schönenberger, D.; et al. HIF-1α and HIF-2α differently regulate tumour development and inflammation of clear cell renal cell carcinoma in mice. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönenberger, D.; Rajski, M.; Harlander, S.; Frew, I.J. Vhl deletion in renal epithelia causes HIF-1α-dependent, HIF-2α-independent angiogenesis and constitutive diuresis. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 60971–60985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gläsker, S.; Smith, J.; Raffeld, M.; Li, J.; Oldfield, E.H.; Vortmeyer, A.O. VHL-deficient vasculogenesis in hemangioblastoma. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2014, 96, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornbos, D.; Kim, H.J.; Butman, J.A.; Lonser, R.R. Review of the Neurological Implications of von Hippel–Lindau Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2018, 75, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonasch, E.; Donskov, F.; Iliopoulos, O.; Rathmell, W.K.; Narayan, V.K.; Maughan, B.L.; et al. Belzutifan for Renal Cell Carcinoma in von Hippel–Lindau Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 2036–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, J.; Brave, M.H.; Weinstock, C.; Mehta, G.U.; Bradford, D.; Gittleman, H.; et al. FDA Approval Summary: Belzutifan for von Hippel-Lindau Disease–Associated Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 4843–4848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Nguyen, C.C.; Zhang, N.T.; Fink, N.S.; John, J.D.; Venkatesh, O.G.; et al. Neurological applications of belzutifan in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Neuro. Oncol. 2023, 25, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangraviti, A.; Raghavan, T.; Volpin, F.; Skuli, N.; Gullotti, D.; Zhou, J.; et al. HIF-1α-Targeting Acriflavine Provides Long Term Survival and Radiological Tumor Response in Brain Cancer Therapy. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.; Jin, H.O.; Masudul Haque, M.; Kim, H.Y.; Jung, H.; Park, J.H.; et al. Synergism of a novel MCL1 downregulator, acriflavine, with navitoclax (ABT 263) in triple negative breast cancer, lung adenocarcinoma, and glioblastoma multiforme. Int. J. Oncol. 2022, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.-W.; Wang, C.-C.; Wu, C.-P.; Lin, Y.-J.; Lee, Y.-C.; Cheng, Y.-W.; et al. Tumor cycling hypoxia induces chemoresistance in glioblastoma multiforme by upregulating the expression and function of ABCB1. Neuro. Oncol. 2012, 14, 1227–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piorecka, K.; Kurjata, J.; Stanczyk, W.A. Acriflavine, an Acridine Derivative for Biomedical Application: Current State of the Art. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 11415–11432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piorecka, K.; Kurjata, J.; Gostynski, B.; Kazmierski, S.; Stanczyk, W.A.; Marcinkowska, M.; et al. Is acriflavine an efficient co-drug in chemotherapy? RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 21421–21431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Shen, J.; Liu, Y.; Lu, L.Y.; Ding, K.; Fortmann, S.D.; et al. The HIF-1 antagonist acriflavine: visualization in retina and suppression of ocular neovascularization. J. Mol. Med. (Berl) 2017, 95, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albiñana, V.; Villar Gómez de las Heras, K.; Serrano-Heras, G.; Segura, T.; Perona-Moratalla, A.B.; Mota-Pérez, M.; et al. Propranolol reduces viability and induces apoptosis in hemangioblastoma cells from von Hippel-Lindau patients. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2015, 10, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, S.; Hui, X.; You, C. Establishment and Characterization of Cell Lines from Primary Culture of Hemangioblastoma Stromal Cells. Neurol. India 2020, 68, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welten, C.M.; Keats, E.C.; Ang, L.-C.; Khan, Z.A. Hemangioblastoma Stromal Cells Show Committed Stem Cell Phenotype. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2012, 39, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reifenberger, G.; Reifenberger, J.; Bilzer, T.; Wechsler, W.; Collins, V.P. Coexpression of transforming growth factor-alpha and epidermal growth factor receptor in capillary hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system. Am. J. Pathol. 1995, 147, 245–250 https://pubmedncbinlmnihgov/7639324/. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Flamme, I.; Krieg, M.; Plate, K.H. Up-Regulation of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in Stromal Cells of Hemangioblastomas Is Correlated with Up-Regulation of the Transcription Factor HRF/HIF-2α. Am. J. Pathol. 1998, 153, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raval, R.R.; Lau, K.W.; Tran, M.G.B.; Sowter, H.M.; Mandriota, S.J.; Li, J.-L.; et al. Contrasting Properties of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 (HIF-1) and HIF-2 in von Hippel-Lindau-Associated Renal Cell Carcinoma. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 25, 5675–5686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondo, K.; Kim, W.Y.; Lechpammer, M.; Kaelin, W.G. Inhibition of HIF2α Is Sufficient to Suppress pVHL-Defective Tumor Growth. PLoS Biol. 2003, 1, e83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitanio, J.F.; Mazza, E.; Motta, M.; Mortini, P.; Reni, M. Mechanisms, indications and results of salvage systemic therapy for sporadic and von Hippel-Lindau related hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2013, 86, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, L.; Soleimani, M. Belzutifan: a novel therapeutic for the management of von Hippel–Lindau disease and beyond. Future Oncol. 2024, 20, 1251–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonasch, E.; McCutcheon, I.E.; Waguespack, S.G.; Wen, S.; Davis, D.W.; Smith, L.A.; et al. Pilot trial of sunitinib therapy in patients with von Hippel–Lindau disease. Ann. Oncol. 2011, 22, 2661–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galarza Fortuna, G.M.; Ozay, Z.I.; Hage Chehade, C.; Gebrael, G.; Li, H.; Maughan, B.L. Von Hippel Lindau syndrome: A systematic review of pharmaceutical treatments. Kidney Cancer 2024, 8, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palavani, L.B.; Camerotte, R.; Vieira Nogueira, B.; Ferreira, M.Y.; Oliveira, L.B.; Pari Mitre, L.; et al. Innovative solutions? Belzutifan therapy for hemangioblastomas in Von Hippel-Lindau disease: A systematic review and single-arm meta-analysis. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2024, 128. [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, M. Acridine--a neglected antibacterial chromophore. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001, 47, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortezaee, K.; Majidpoor, J. The impact of hypoxia on immune state in cancer. Life Sci. 2021, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Hill, H.; Christie, A.; Kim, M.S.; Holloman, E.; Pavia-Jimenez, A.; et al. Targeting renal cell carcinoma with a HIF-2 antagonist. Nature 2016, 539, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courtney, K.D.; Ma, Y.; de Leon, A.D.; Christie, A.; Xie, Z.; Woolford, L.; et al. HIF-2 complex dissociation, target inhibition, and acquired resistance with PT2385, a first-in-class HIF-2 inhibitor, in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res 2020, 26, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Key, J.; Scheuermann, T.H.; Anderson, P.C.; Daggett, V.; Gardner, K.H. Principles of Ligand Binding within a Completely Buried Cavity in HIF2α PAS-B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 17647–17654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, S.F.; Fu, J.; Kim, Y.C.; Tsujinaka, H.; Shen, J.; Lima e Silva, R.; et al. Sustained delivery of acriflavine from the suprachoroidal space provides long term suppression of choroidal neovascularization. Biomaterials 2020, 243, 119935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korelidou, A.; Domínguez-Robles, J.; Islam, R.; Donnelly, R.F.; Coulter, J.A.; Larrañeta, E. 3D-printed implants loaded with acriflavine for glioblastoma treatment. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliopoulos, O.; Iversen, A.B.; Narayan, V.; Maughan, B.L.; Beckermann, K.E.; Oudard, S.; et al. Belzutifan for patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease-associated CNS haemangioblastomas (LITESPARK-004): a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, 1325–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Surgical removal of a hemangioblastoma located in the cerebellum. Intraoperative images illustrate the surgical procedure for hemangioblastoma resection. The tumor, characterized by its highly vascularized nature, was carefully identified, isolated, and progressively dissected. This surgical approach is the standard treatment for CNS hemangioblastomas in patients with VHL disease, despite the risk of recurrence and the potential need for multiple interventions.

Figure 1.

Surgical removal of a hemangioblastoma located in the cerebellum. Intraoperative images illustrate the surgical procedure for hemangioblastoma resection. The tumor, characterized by its highly vascularized nature, was carefully identified, isolated, and progressively dissected. This surgical approach is the standard treatment for CNS hemangioblastomas in patients with VHL disease, despite the risk of recurrence and the potential need for multiple interventions.

Figure 2.

Growth and morphology of primary cell cultures from CNS hemangioblastomas. (a) Representative images show the successful establishment and expansion of primary cell cultures derived from CNS hemangioblastoma samples obtained from different anatomical locations, including the cerebellum, spinal cord, and temporal lobe. Primary HB cells predominantly exhibited a spindle-shaped or polygonal morphology and proliferated as monolayers under culture conditions. (b) A subset of HB tumor samples failed to develop proliferating primary cultures, particularly those derived from smaller tissue specimens.

Figure 2.

Growth and morphology of primary cell cultures from CNS hemangioblastomas. (a) Representative images show the successful establishment and expansion of primary cell cultures derived from CNS hemangioblastoma samples obtained from different anatomical locations, including the cerebellum, spinal cord, and temporal lobe. Primary HB cells predominantly exhibited a spindle-shaped or polygonal morphology and proliferated as monolayers under culture conditions. (b) A subset of HB tumor samples failed to develop proliferating primary cultures, particularly those derived from smaller tissue specimens.

Figure 3.

HIF-1α and HIF-2α expression in primary HB cells and their distribution among cellular components by flow cytometry analysis. (a) Representative fluorescence histogram (top left) for HIF-1α-PE single staining and dot plots (bottom left) for dual staining using fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against HIF-1α-PE and cell-specific markers: CD99-APC for stromal cells, NG2-FITC for pericytes, and CD34-PE-Cy7 for endothelial cells. The histogram (right) depicts the percentage of HIF-1α-expressing cells within each cellular subpopulation: stromal cells (double-positive for HIF-1α-PE and CD99-APC), pericytes (double-positive for HIF-1α-PE and NG2-FITC), and endothelial cells (double-positive for HIF-1α-PE and CD34-PE-Cy7). These values are compared with HIF-1α expression levels in non-hemangioblastoma cells, including astrocytoma, gliosarcoma, glioblastoma, colorectal carcinoma, and human retinal pigment epithelium (ARPE) cell lines. (b) Illustrative fluorescence distribution chart (top left) for HIF-2α-PE staining, along with scatter plots (bottom left) depicting its co-detection with CD99-APC, NG2-FITC, or CD34-PE-Cy7. The histogram (right) shows the proportion of stromal (HIF-2α-PE⁺/CD99-APC⁺), pericytic (HIF-2α-PE⁺/NG2-FITC⁺), and endothelial (HIF-2α-PE⁺/CD34-PE-Cy7⁺) cells expressing HIF-2α, compared to non-hemangioblastoma cell lines positive for HIF-2α. Raw data for both histograms are available in the Supplementary Material (Data Set).

Figure 3.

HIF-1α and HIF-2α expression in primary HB cells and their distribution among cellular components by flow cytometry analysis. (a) Representative fluorescence histogram (top left) for HIF-1α-PE single staining and dot plots (bottom left) for dual staining using fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against HIF-1α-PE and cell-specific markers: CD99-APC for stromal cells, NG2-FITC for pericytes, and CD34-PE-Cy7 for endothelial cells. The histogram (right) depicts the percentage of HIF-1α-expressing cells within each cellular subpopulation: stromal cells (double-positive for HIF-1α-PE and CD99-APC), pericytes (double-positive for HIF-1α-PE and NG2-FITC), and endothelial cells (double-positive for HIF-1α-PE and CD34-PE-Cy7). These values are compared with HIF-1α expression levels in non-hemangioblastoma cells, including astrocytoma, gliosarcoma, glioblastoma, colorectal carcinoma, and human retinal pigment epithelium (ARPE) cell lines. (b) Illustrative fluorescence distribution chart (top left) for HIF-2α-PE staining, along with scatter plots (bottom left) depicting its co-detection with CD99-APC, NG2-FITC, or CD34-PE-Cy7. The histogram (right) shows the proportion of stromal (HIF-2α-PE⁺/CD99-APC⁺), pericytic (HIF-2α-PE⁺/NG2-FITC⁺), and endothelial (HIF-2α-PE⁺/CD34-PE-Cy7⁺) cells expressing HIF-2α, compared to non-hemangioblastoma cell lines positive for HIF-2α. Raw data for both histograms are available in the Supplementary Material (Data Set).

Figure 4.

mRNA and protein levels of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in primary HB cells. (a) HIF-1α and HIF-2α transcript levels were determined by real-time RT-PCR in different primary cell cultures from hemangioblastomas and gliomas, as well as in the SW48 colorectal carcinoma cell line, which was used as a control. The mRNA levels of these factors were normalized to β-tubulin as an internal control and then to the corresponding HIF-α isoform mRNA from SW48 cells using the 2^(-ΔΔCT) method to determine relative gene expression with respect to the control cells. Results are presented as the mean ± SD from two independent experiments. Raw data for both histograms are available in the Supplementary Material (Data Set). Statistical significance was evaluated using Student’s t-test: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, compared to control colon cells. (b) Expression of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in hemangioblastoma (HB) cells, primary astrocytoma (AST) and glioblastoma (GB) cells, and SW48 cells was detected by Western blot analysis. In this figure, the grouped blots were cropped from different Western blot experiments, with β-tubulin as a loading control. The original blots are presented in the

Supplementary Figure S1.

Figure 4.

mRNA and protein levels of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in primary HB cells. (a) HIF-1α and HIF-2α transcript levels were determined by real-time RT-PCR in different primary cell cultures from hemangioblastomas and gliomas, as well as in the SW48 colorectal carcinoma cell line, which was used as a control. The mRNA levels of these factors were normalized to β-tubulin as an internal control and then to the corresponding HIF-α isoform mRNA from SW48 cells using the 2^(-ΔΔCT) method to determine relative gene expression with respect to the control cells. Results are presented as the mean ± SD from two independent experiments. Raw data for both histograms are available in the Supplementary Material (Data Set). Statistical significance was evaluated using Student’s t-test: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, compared to control colon cells. (b) Expression of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in hemangioblastoma (HB) cells, primary astrocytoma (AST) and glioblastoma (GB) cells, and SW48 cells was detected by Western blot analysis. In this figure, the grouped blots were cropped from different Western blot experiments, with β-tubulin as a loading control. The original blots are presented in the

Supplementary Figure S1.

Figure 5.

Effects of acriflavine exposure on cell viability, cell cycle, and cell death in primary HB cultures. (a) Representative phase-contrast microscopy images showing morphological changes in primary HB cells treated with increasing concentrations of acriflavine (1–100 µM) for 24 hours. (b) Hemangioblastoma cell viability was assessed in cells incubated with (concentration indicated) or without acriflavine using the MTT assay. Cell viability was normalized to untreated cells for 24, 48, and 72 hours and represented as a histogram (mean ± SD from two independent experiments). Statistical significance was assessed using Student’s t-test: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, relative to HB cells not exposed to acriflavine. (c) Characteristic DNA content profiles from flow cytometry (left), displaying cells in sub-G1, G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases of the cell cycle, stained with propidium iodide after 24 hours of incubation with 2.5 and 25 µM of acriflavine. The percentage of cells in each cell cycle phase is represented in histogram (right) from two separate experiments. Data are presented as means ± SD. (d) Representative dot plots (left) of flow cytometry analysis using Annexin V-Dy634 (AnnV) and propidium iodide (PI) staining, showing cell death by early (light green dots, single-positive for AnnV) and late (dark green dots, double-positive for AnnV and PI) apoptosis, and necrosis (blue dots, single-positive for PI) in primary HB cultures treated with two concentrations of acriflavine after 48 hours. The histogram (right) shows the cell population undergoing necrotic, late, and early apoptotic cell death, as well as viable cells in untreated and treated cells (mean ± SD from two independent experiments). Raw data for histograms (b, c, and d) can be found in the Supplementary Material (Data Set).

Figure 5.