1. Introduction

Against common belief, mandibular condyle fractures are not that rare, with morbidity rates ranging up 52%, depending on actual literature sources [

1,

2,

3]. There has been a lot of debate over the years about whether surgical or conservative treatment yields better results. Wide-spread access to computed tomography and higher awareness of complications associated with untreated this kind of trauma is the reason why more and more hospitals opt for surgical treatment of such injuries. Proper stability and decreased scarification osteosynthesis save functional results in temporomandibular joint (TMJ) [

4]. Some loss of bone dimensions is seen following osteosynthesis (0.3-1.6 mm) and close treatment (6.9 mm). A factor that is surely related to this, even if only partially, is the function restoration following osteosynthesis, which ranges from 63 to 90%. This contrasts with the poor TMJ function restoration ratios achieve with closed treatment (40%). [

3]Taking the results of such studies into consideration, it is warranted to strive for more frequent application of surgical techniques that decrease bone resorption.

Each medical center tries to improve the surgical techniques applied and obtain the most satisfactory anatomical and functional effect. There are numerous papers reporting attempts at establishing best possible access technique, material and shape of plates for osteosynthesis [

5,

6,

7].

A commonly used fixation material is titanium alloy, which, due to its biological interaction [

8,

9] with the living organism, could be removed once bone union is achieved. There are however certain anatomical difficulties associated with obtaining surgical approach [

10] to the condylar process. These difficulties are primarily associated with the need for re-surgery within the area of the pre-existing scar. Such surgery is often associated with a more difficult course of the procedure, including the presence of synechiae that prevent easy access to the anatomical structures. Surgery carried out in this anatomical region also requires working in the direct vicinity of the facial nerve and since scarring reduces visibility and poses additional challenges related to proper identification of anatomical structures, nerve injury is more frequent. Not to mention the reluctance of patients to re-surgery when, from their subjective point of view, it is not needed. It seems, however, that titanium plates and screws remaining inside some patients’ bodies cause complications, as they provoke resorption of the surrounding bone. The issue is fairly well-known for lag screw fixations [

11,

12,

13], while in the case of osteosynthesis the miniplate has not been studied in this anatomical region.

Our maxillofacial surgery department has focused on condylar process fractures for many years, and we have published many papers focusing on bone loss around the screws used for osteosynthesis of high fractures. However, we have also noticed a gap in the literature and it is difficult to find papers focused on on bone loss ocurring after the healing period at osteosynthesis plates used for treating manidibular condylar fractures.

Therefore, we realized how informative and revealing it can be to study this very issue, and the results can improve surgical technique and better plan when it will be necessary to take out the osteosynthesis plate

The purpose of this study is to determine the extent of bone resorption related to fixation material remaining in the body after surgical treatment of extracapsular fractures of the mandibular condylar process.

2. Materials and Methods

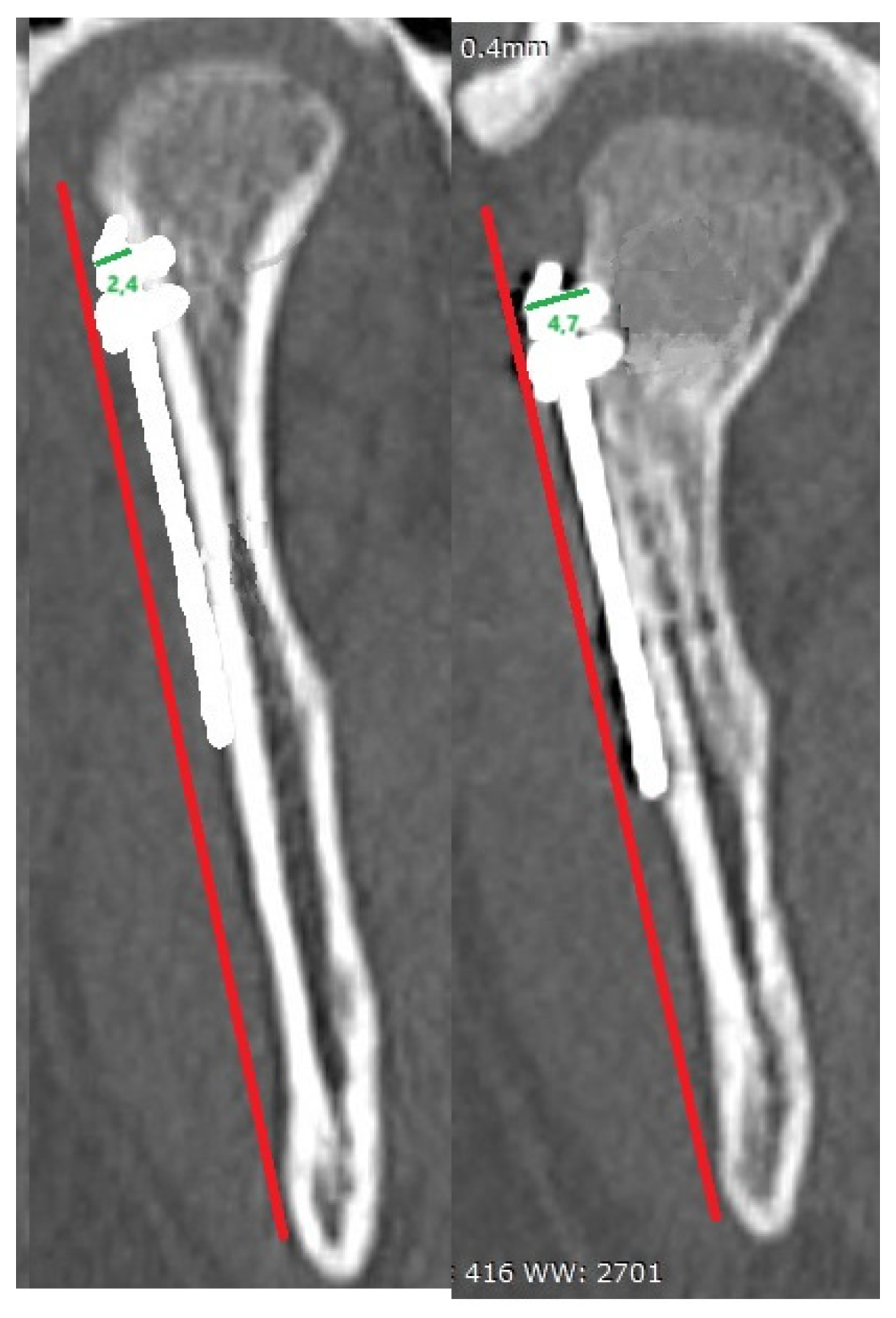

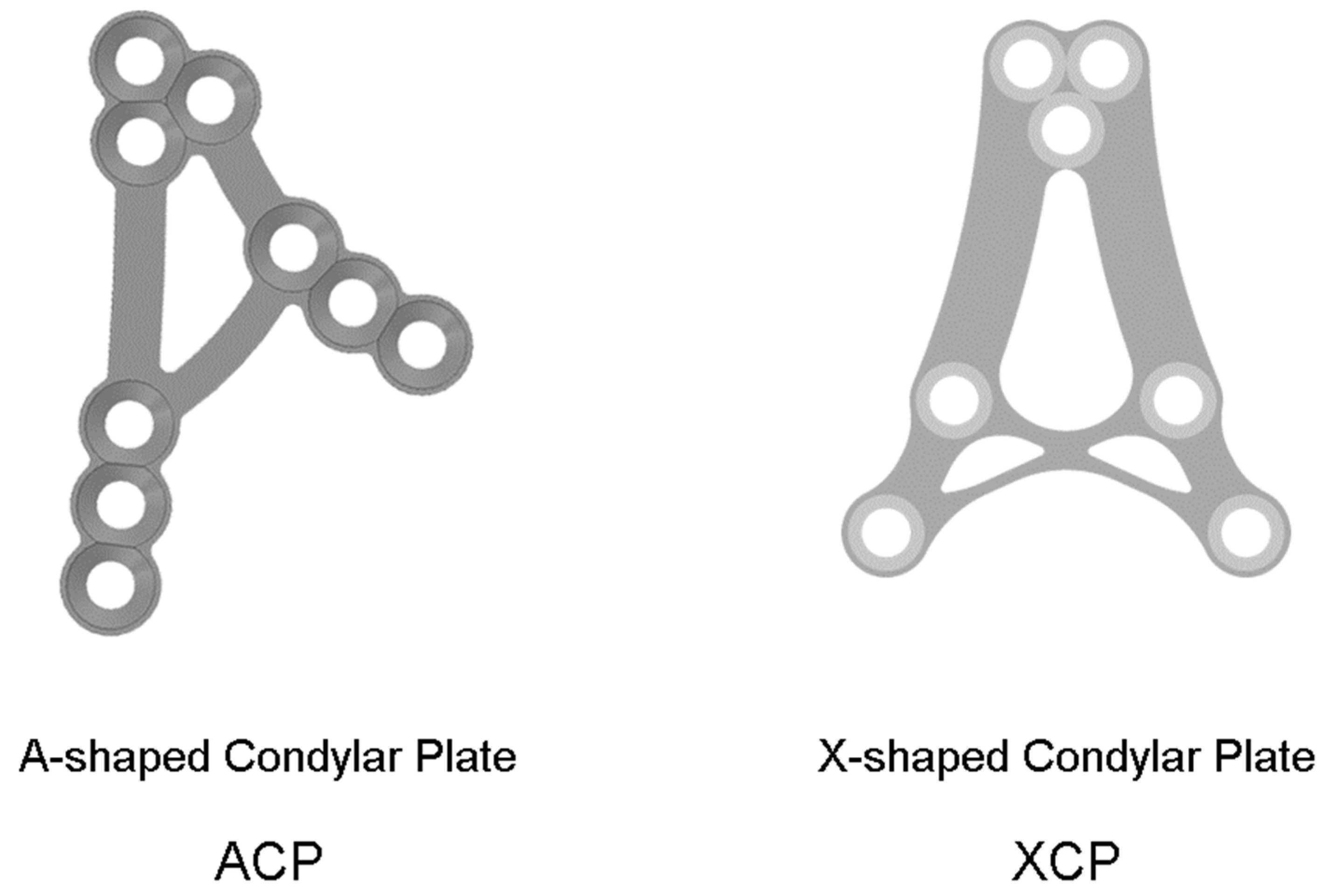

The retrospective study was authorized by a bioethics committee (corresponding ethical approvalcode: RNN 227/19/KE). The research material consisted of 220 patients admitted to the Department of Maxillofacial Surgery, Medical University of Lodz, Poland. Used fixing material (

Figure 1) was titanium grade 5, ACP and XCP, dedicated miniplates and 2.0 mm self-tapping screws by ChM (

www.chm.eu/en/ access date: 8 May 2024).

Pathological features of the injury were evaluated in RadiAnt (

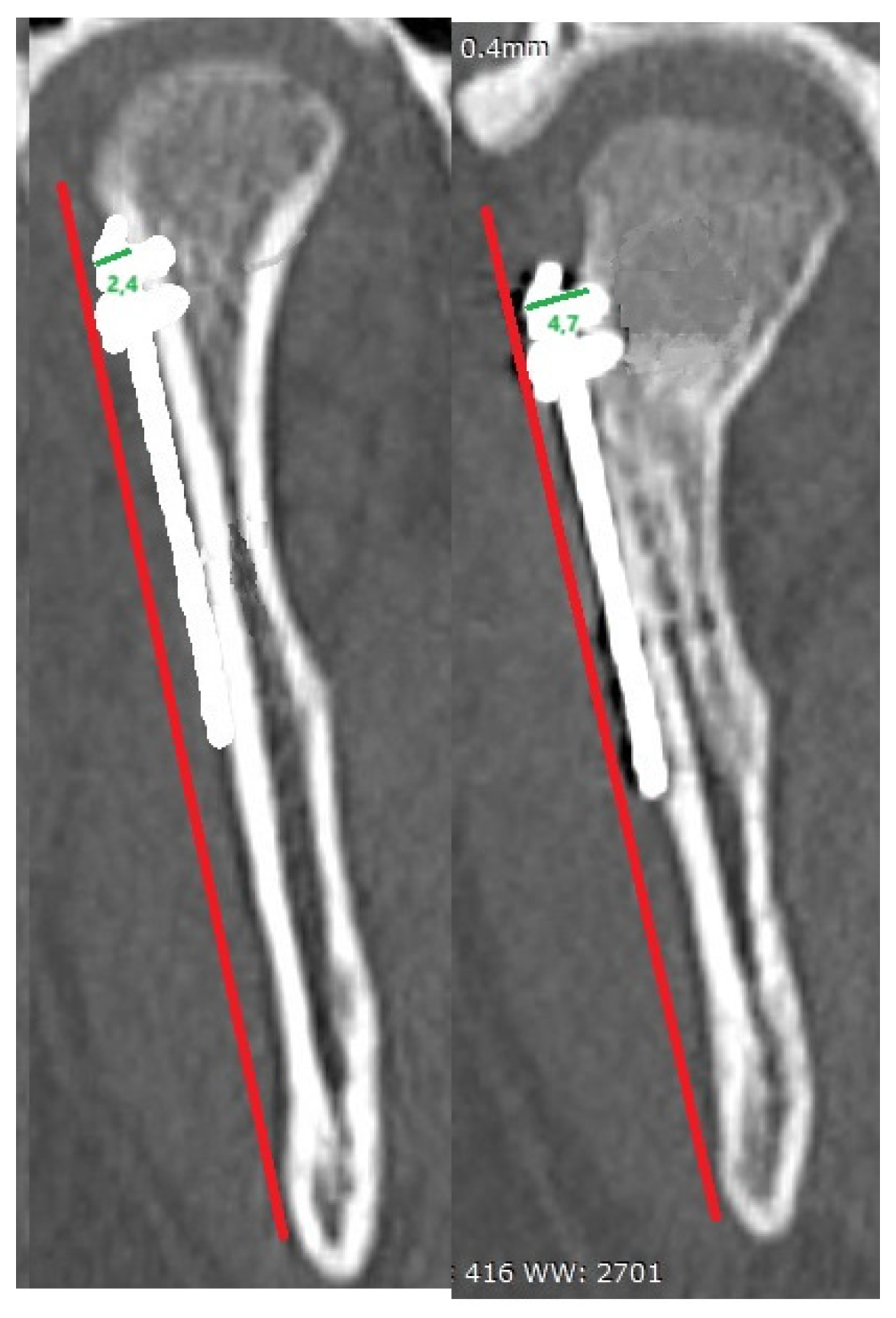

www.radiantviewer.com, accessed on 1 October 2022) using computed tomography scans, the modality of choice at the Department. A bone window (window level = 300 HU, window width = 1500 HU) was used for the study. The region of the head of the screw placed in the mini-plate used for osteosynthesis was examined. The change in the position of the bone border at 12 months was measured in millimeters. If bone loss was observed with more than one screw, the average defect size was calculated. Measurements were taken on CT scans both postoperatively and 12 months later. A frontal projection was used. The measurement was taken from the head of the screw parallel to the screw and extending to the bone border. Average bone loss was obtained by adding all atrophy around the screws used for the ORIF of the condylar process fracture and dividing by the number of screws used.

The patient population was made up of individuals with condylar process fractures who were admitted from the Emergency Unit, transferred from other hospitals and reported to the outpatient clinic. Patients with fractures of the base of the condylar process, low neck and high neck, according to Kozakiewicz's classification [

14], were selected for the study. Patients who had a condylar process fracture treated only with screws or conservatively were not considered. Fractures were screened for bone fragment displacement and joint dislocation. Questionnaires used included questions about the site of the injury, how it occurred and whether it involved one or both condylar processes. Additional fractures in the mandible, craniofacial region and whole-body injuries were also registered.

All patients were treated under general anesthesia with nasotracheal intubation (NTI) by a surgical team at the Department of Maxillofacial Surgery, Medical University of Lodz. In all cases the fixing material used was grade 5 titanium/ We used ACP and XCP design plates, as well as custom miniplates with 2.0 mm self-tapping screws by ChM

Using the surgical protocols, delay after the injury and duration of surgical procedure were noted. The type of surgical approach used was preauricular and retromandibular, the number and length of screws inserted, as well as the osteosynthesis material used we also recorded. Each of the patients included in the study had regular follow-up visits and a CT scan after 12 months post-operationally. Based on the CT scan, consolidation in the fracture area, bone loss in the area of the screws and plates, change in the length of the mandibular ramus following osteosynthesis and on the opposite side after 12 months, as well as deformities of the mandibular head were studied.

The research included 276 fractures of the base, low and high neck of the condylar process.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis includes feature distribution evaluation and analysis of regression was applied for assess the relationship between quantitative variables. The difference was considered significant if p < 0.05. Statgraphics Centurion XVI (StarPoint Technologies. INC., The Plains, VA, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

3. Results

The most common cause of mandibular condyle fracture was assault and falling from a height equal to the patient’s own height or higher, as well as bicycle or scooter accidents. The amount of bone resorption in peri-screw bone is independent on injury reason (

Table 1).

The average age of the treated patients was 34.5 ± 15 years. In this group, 18.8% were female and 81.2% were male.

Greater bone loss (p < 0.05) was observed in bilateral fractures of the mandibular condyle (0.86±1.00 mm) and in unilateral (0.33±0.49 mm) fractures. However, as there is an accompanying fracture of the body of the mandible, it seems to have no effect on bone resorption at the condylar fixation (p = 0.548) contrary to an accompanying zygoma fracture, where higher resorption rates are reported in cases of condyle osteosynthesis (1.50±00.00 mm; p < 0.05). The presence of an orbital or maxillary fracture is not related to the resorption at condylar fixation being investigated.

A summary of the collected data is presented below in tables (

Table 2 and

Table 3).

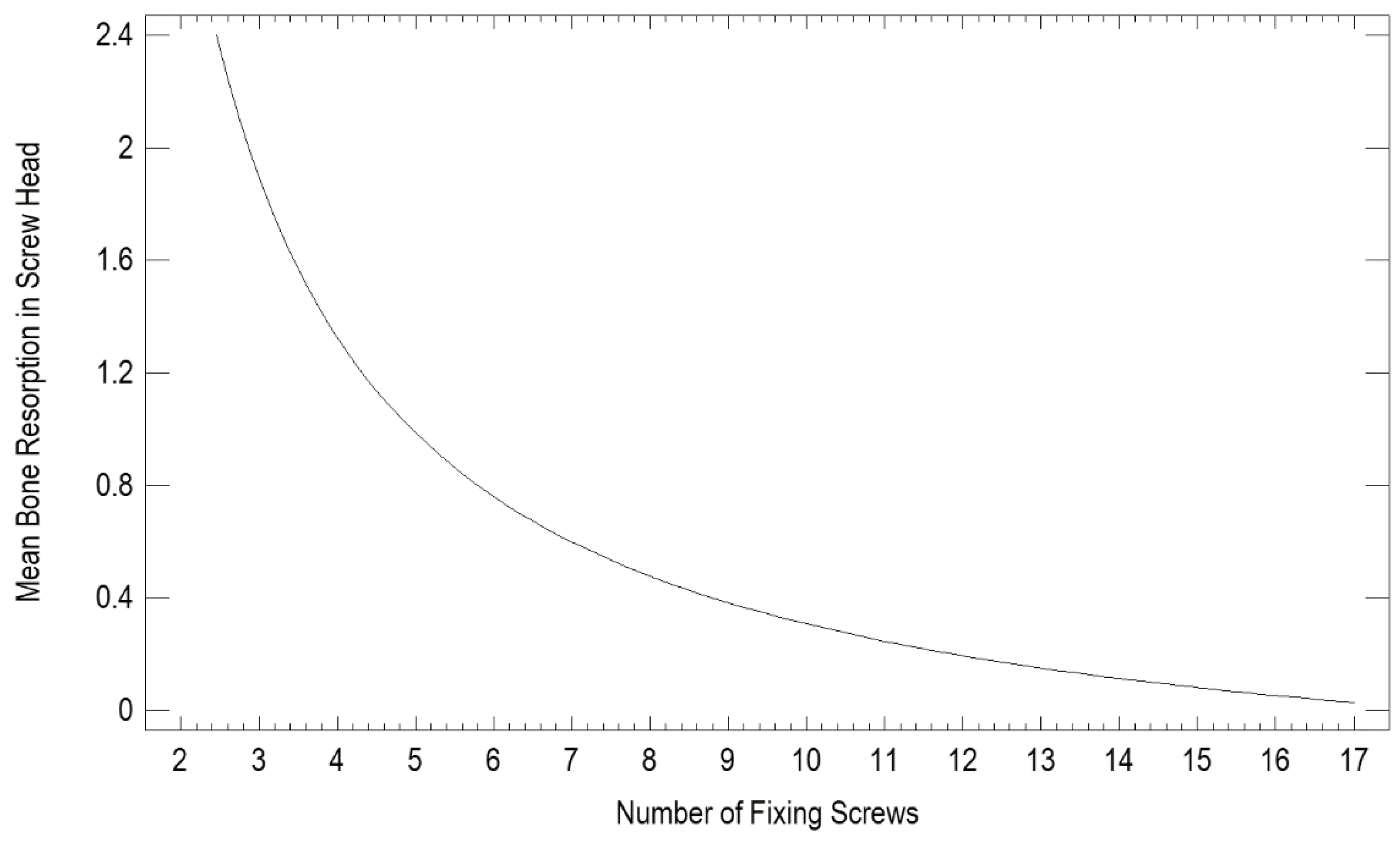

Using screws and miniplates is the gold standard for treating mandibular condylar process fractures. The number of screws (

Figure 2) used makes a difference in bone loss around the screw head. The more screws used, the less bone loss around the screw head is seen (p < 0.05).

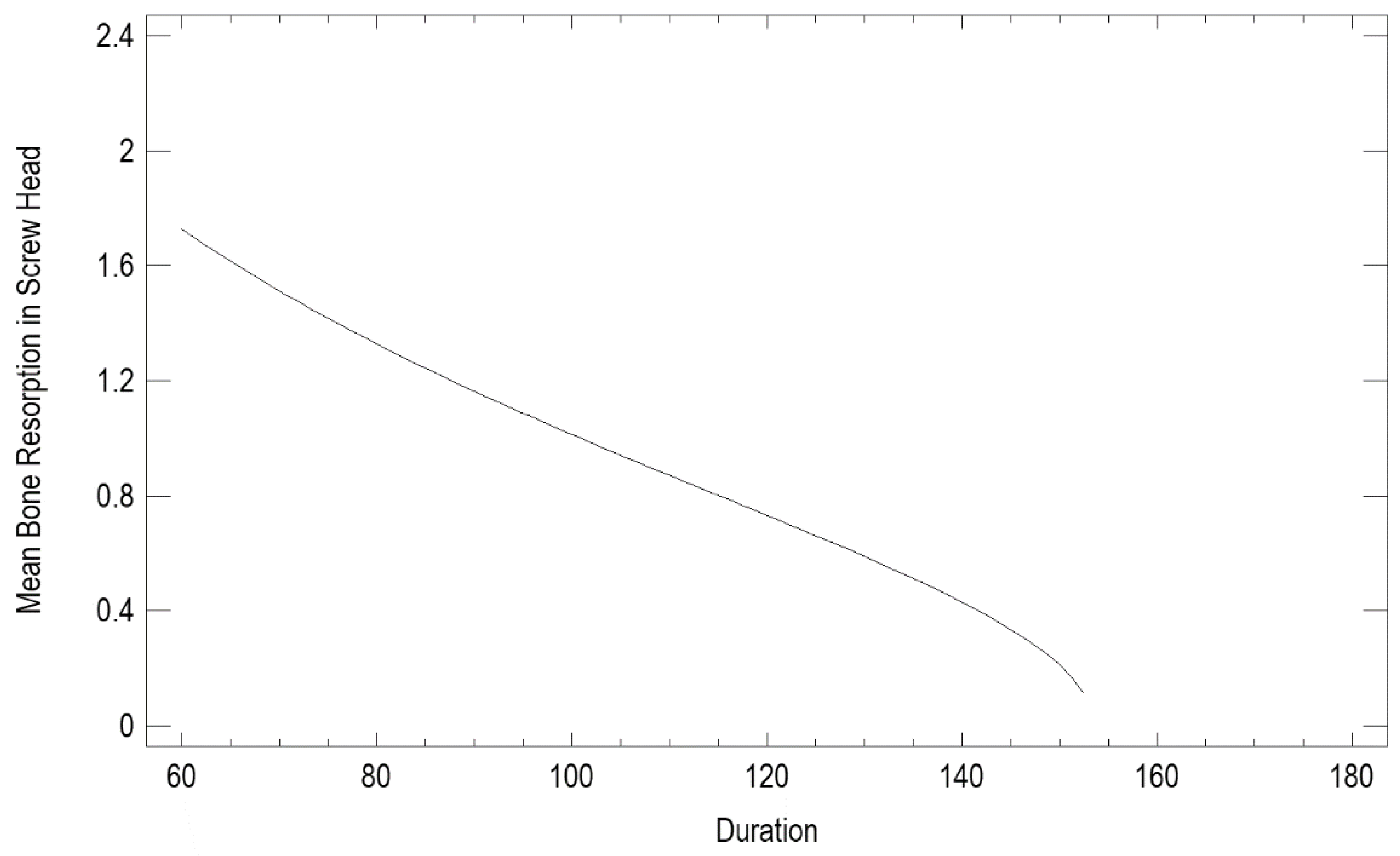

Recorded surgical procedure duration (

Figure 3) ranged from 60 to 180 minutes. A moderately strong relationship between the variables was noted: short osteosynthesis duration (in minutes) led to greater resorption (in mm) in the screw head area (p < 0.0001, correlation coefficient 0.59).

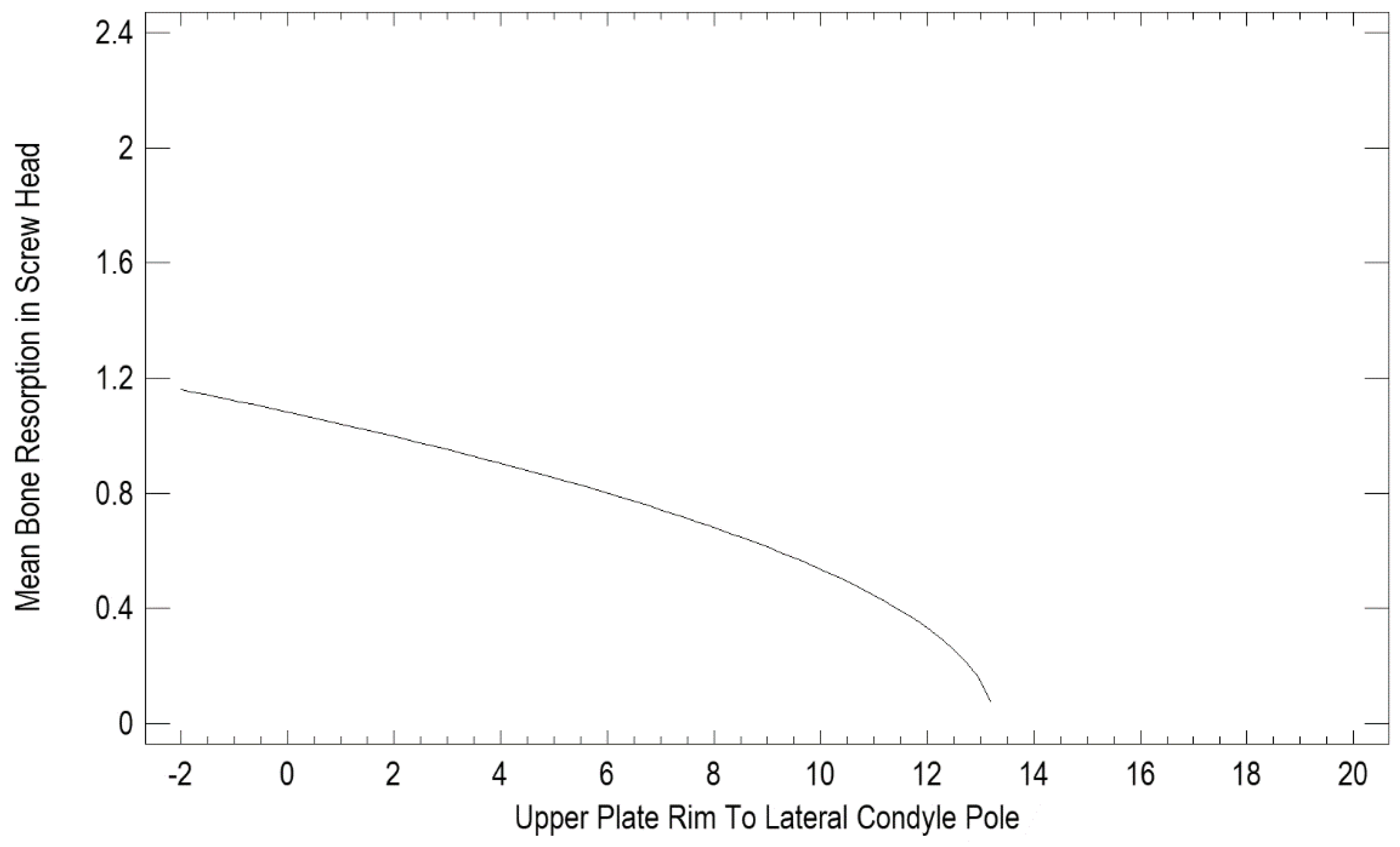

Effect of the distance from the plate edge to the lateral pole of the mandibular head (in mm) is presented in

Figure 4. The recorded values ranged from those overlapping with the lateral pole (negative values) to a distance of as much as 20 mm. A statistical evaluation indicated that proximity to the lateral pole is a risk factor (p < 0.05) for bone resorption at the plate edge (

Figure 5).

There was no relationship between resorption at the head of the screw and delay in the initiation of surgical treatment (p = 0.208), the length of the screw used (p = 0.098), the affected/intact ramus height ratio (p = 0.333). In contrast, a relationship was found between the distance of the plate edge to the lateral pole of the mandibular head (p < 0.001), the distance of the superior screw to the lateral pole (p < 0.0001), the amount of resorption at the plate (p < 0.001), the percentage of screw length resorbed (p < 0.0001), the height of the ramus 12 months after treatment (p < 0.0001), as well as on the unaffected side after 12 months (p < 0.001), and the average resorption around the heads of the screws used.

There was no difference in the amount of bone resorption in cases of fixation of different fractures: basal (0.48±0.69 mm), low-neck (0.00±0.00) and high-neck (1.14±1.31 mm) The amount of resorption with screws is higher (1.12±1.08 mm) in M-type fractures and lower (0.29±0.45 mm) in P-type fractures (p < 0.01).

It was also noted that when performing ORIF of the mandibular condylar process, bone loss around the screw heads is affected by approach selection (p < 0.05). The largest loss was recorded with the preauricular approach, reaching approximately 0.74 mm, while the smallest loss (0.0 mm) was noted with the extended mandibular and intraoral approaches.

After choosing the approach and repositioning the fracture, the choice of fixing material is important. During the study, it was noted that the smallest average loss was recorded with XCP-type plates, reaching approximately 0.33 mm, 0.37 mm with straight plates and ACP plates presenting the highest loss with approximately 0.44 mm.

Unexpectedly, consolidation turned out to be statistically important. We have noted that in the absence of consolidation there is no bone loss around the heads of screws used with plates. Postoperatively, patients had their bite examined. Occlusion obtained has no influence on bone loss (p = 0.46) On the other hand, it was proven that the greatest bone loss was seen in the patient who did not achieve stable bite conditions due to a small number of teeth and not using dentures (p < 0.05).

It was also noted that in the absence of osteosynthesis there is less atrophy at the screw heads.

4. Discussion

As in earlier research [

1], it was found that the most common reason for mandibular condyle fracture among women is falls and assault among men. Moreover, females are at risk due to lower bone density [

15]. Fortunately, these are low-energy injuries and generally women are a minority among patients treated for mandibular bone fractures. This is confirmed by the matter and clinical (approx. 80%) presented here.

There are a number of papers that focus on bone loss around screws in treated fractures of the mandibular head [

16,

17]. Few papers focus on loss around plates and screws used with plates when treating a lower mandibular condylar process fracture. Research (

Figure 1) shows that the more screws are used, the less atrophy is seen. It should be noted that the optimal number of screws is 9. Any further reduction of bone loss is already negligible beyond that, so there is ample evidence in support of using at least 9 screws in low condylar process fractures.

The low resorptions rates seen with prologed procedures (

Figure 3) seem surprising and are difficult to explain. It is known that longer surgery affects patients and generally constitute a risk factor [

19] and not a success predictor. The authors believe that longer duration of osteosynthesis may be related to the greater involvement of the surgical team and not simply to the complexity of the skeletal damage suffered.

It should be noted (

Figure 4) that the location of osteosynthesis is related to resorption. Based on our findings, factors that induce resorption are not limited to insertion of a plate on the articular surface or covering the lateral pole of the mandibular head. Even lower osteosyntheses within the mandibular neck entail resorption. Only distant placement of the fixation material, more than 14 mm away from the lateral pole, does not lead to bone resorption at the osteosynthesis site. This is probably the result not only of irritation of the surrounding tissues with titanium material [

19,

20] but also the morphology of the fracture [

21], which does not affect the damage to the mandibular head [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

It has been noted that the length of the screws used does not very much affect the amount of bone loss, so the surgeon should be guided by the stability of fixation, the amount and quality of bone at the site of the planned screw fixation.The observed relationship of smaller mandibular ramus heights with higher mean bone loss at the screw heads may be due to the standard available miniplate sizes and the small bone surface area available for osteosynthesis. Thus, the edge of the plate in patients with shorter ramus may be located closer to the vulnerable lateral pole. This unfavorable relationship may also result from combined atrophy at the screws with atrophic remodeling of mandibular heads [

26,

28,

29]. Surprisingly, there is significant resorption at the osteosynthesis screws in the case of M fractures, which are characterized by a lack of shortening of the ascending ramus. The authors are unable to explain this observation.

More severe trauma, technical difficulties caused by lower fragments stability seem to explain the greater bone resorptions in bilateral condylar fractures. Greater extent of the injury is also supported by the observed greater resorption when accompanied by a fracture of the zygomatic bone. This is probably not a homogeneous factor or one not directly related to resorption at the condyle, since an accompanying fracture of the mandibular body or other parts of the facial skeleton, except the zygomatic bone, are not related to bone resorption at the osteosynthesis of the mandibular condyle.

It is surprising that lack of union in a mandibular condylar process fracture results in only a small amount of bone loss at the heads of the screws. This may be related to the formation of load-bearing mechanical conditions, which provide stimulus for bone formation at the loaded screws.

It is worth noting that the significance of the presented bone loss is generally not threatening to the outcome of treatment, as it does not affect the loss of height of the mandibular ramus. The exceptions here may be the resorption observed at the upper end of the miniplates placed near the lateral pole of the mandible head. This can result in the involvement of the mandibular head in the resorptive process, shortening of the ramus and finally malocclusion. A second clinically devastating case may be patients with significant bone resorption even on the lateral surface of the condylar process (distant from the mandibular head), as this causes greater plate strain and plate fracture or pull-out of the fixation material due to exceeding the pull-out force for residual length of screw fixation (usually only 6 mm in total length).

5. Conclusions

Fractures of the mandible, including condylar processes, are fractures routinely treated at maxillofacial surgery departments. All current research is aimed at improving the final result achieved after ORIF of the condylar process. Through the research conducted, it is possible to predict the steps that cause bone atrophy around both screws and plates in condylar process fractures. Considering the results of our study, atrophy occurs not only around screws as part of treating mandibular head fractures, but also around plates used in lower fractures. When treating such injuries, using two ostetosynthesis plates is known to provide the best mechanical results.

It is worth noting when entering the surgery, choosing a preauricular approach, it is worth to be tempted to extend retromandibularly, When treating the fracture, an appropriate distance should be selected - 14 mm below the lateral pole. This is because, as seen in [

Figure 4], this can result in bone loss both around the screw head and at the lateral pole. This will help choose the proper length and shape of the ORIF plate. Next, that the optimal number of screws is 9, and during the procedure, supplying lower fractures of the mandibular condylar processes, there is no need to take into account the length of the screws.

In addition to planning of the procedure itself, it can be predicted that women with zygomatic arch fractures are at a greater risk of bone atrophy around the screws. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation may be considered in such cases. This knowledge prevents complications and allows a procedure that provides the most benefits to the patient.

Funding

This research was funded by Medical University of Lodz, grant number 503/1-138-01/503-11/001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Bioethics Committee of the Medical University of Lodz (RNN/125/15/KEW, date of approval: 19 May 2015 and RNN/738/12/KB, date of approval: 20 November 2012) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kozakiewicz, M.; Walczyk,A. Current Frequency of MandibularCondylar Process Fractures. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1394. [CrossRef]

- Tatsumi, H.; Matsuda, Y.;Toda, E.; Okui, T.; Okuma, S.;Kanno, T. Postoperative Complications Following Open Reduction and Rigid InternalFixation of Mandibular CondylarFracture Using the HighPerimandibular Approach.Healthcare 2023, 11, 1294.

- Kolk, A., Scheunemann, L.-M., Grill, F., Stimmer, H., Wolff, K.-D., & Neff, A. (2020). Prognostic factors for long-term results after condylar head fractures: a comparative study of non-surgical treatment versus open reduction and osteosynthesis. Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery. [CrossRef]

- Neff A, Kolk A, Meschke F, Deppe H, Horch HH. Kleinfragmentschrauben vs. Plattenosteosynthese bei Gelenkwalzenfrakturen. Vergleich funktioneller Ergebnisse mit MRT und Achsiographie [Small fragment screws vs. plate osteosynthesis in condylar head fractures]. Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir. 2005.9 (2):80-88. [CrossRef]

- Kozakiewicz, M.; Swiniarski, J. “A” shape plate for open rigid internal fixation of mandible condyle neck fracture. J. Craniomax-illofac. Surg. 2014, 42, 730–737.

- Kozakiewicz, M.; Okulski,J.; Krasowski, M.; Konieczny, B.;Zielinski, R. Which of 51 PlateDesigns Can Most Stably Fixate theFragments in a Fracture of theMandibular Condyle Base? J. Clin.Med. 2023, 12, 4508.

- Çimen, E.; Önder, M.E.; Cambazoglu, M.; Birant, E. Comparison of Different Fixation Types Used in Unilateral MandibularCondylar Fractures. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2016, 27, 1277–128. [CrossRef]

- Zalewska, A.; Antonowicz, B.; Szulimowska, J.; Zieniewska-Siemieńczuk, I.; Leśniewska, B.; Borys, J.; Zięba, S.; Kostecka-Sochoń, P.; Żendzian-Piotrowska, M.; Lo Giudice, R.; et al. Mitochondrial Redox Balance of Fibroblasts Exposed to Ti-6Al-4V Microplates Subjected to Different Types of Anodizing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12896. [CrossRef]

- Wozniak, L.; Ratajczak-Wrona, W.; Borys, J.; Antonowicz, B.; Nowak, K.; Bortnik, P.; Jablonska, E. Levels of Biological Markers of Nitric Oxide in Serum of Patients with Mandible Fractures. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2832. [CrossRef]

- Sikora, M.; Chęciński, M.; Chlubek, D. Retro-Auricular Approach to the Fractures of the Mandibular Condyle: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 230. [CrossRef]

- Herbert T.J. Fisher W.E. Management of the fractured scaphoid using a new bone screw. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1984; 66: 114-123.

- Kolk A. Neff A. Long-term results of ORIF of condylar head fractures of the mandible: a prospective 5-year follow-up study of small-fragment positional-screw osteosynthesis (SFPSO).J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2015; 43: 452-461.

- Kozakiewicz, M. Small-diameter compression screws completely embedded in bone for rigid internal fixation of the condylar head of the mandible. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg, 2018, 56: 74-76. [CrossRef]

- Kozakiewicz M. Classification proposal for fractures of the processus condylaris mandibulae. Clin Oral Investig. 2019 Jan;23(1):485-491. [CrossRef]

- Miyake M, Oda Y, Iwanari S, Kudo I, Igarashi T, Honda K, Shinoda K, Sairenji E. A case of osteoporosis with bilateral defects in the mandibular processes. J Nihon Univ Sch Dent. 1995 Jun;37(2):108-14. [CrossRef]

- Kozakiewicz, M. Small-diameter compression screws completely embedded in bone for rigid internal fixation of the condylar head of the mandible. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg, 2018, 56: 74-76. [CrossRef]

- Neff A, Kolk A, Meschke F, Deppe H, Horch HH. Kleinfragmentschrauben vs. Plattenosteosynthese bei Gelenkwalzenfrakturen. Vergleich funktioneller Ergebnisse mit MRT und Achsiographie [Small fragment screws vs. plate osteosynthesis in condylar head fractures]. Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir. 2005.9 (2):80-88. [CrossRef]

- Kozakiewicz, M.; Zieliński, R. Relationship between blood loss and other factors during orthognathic surgery. Dent Med Probl, 2015, 52, 144-149.

- Borys, J.; Maciejczyk, M.; Antonowicz, B.; Krętowski, A.; Sidun, J.; Domel, E.; Dąbrowski, J.R.; Ładny, J.R.; Morawska, K.; Zalewska, A. Glutathione Metabolism, Mitochondria Activity, and Nitrosative Stress in Patients Treated for Mandible Fractures. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 127. [CrossRef]

- Zalewska, A.; Antonowicz, B.; Szulimowska, J.; Zieniewska-Siemieńczuk, I.; Leśniewska, B.; Borys, J.; Zięba, S.; Kostecka-Sochoń, P.; Żendzian-Piotrowska, M.; Lo Giudice, R.; et al. Mitochondrial Redox Balance of Fibroblasts Exposed to Ti-6Al-4V Microplates Subjected to Different Types of Anodizing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12896. [CrossRef]

- Wozniak, L.; Ratajczak-Wrona, W.; Borys, J.; Antonowicz, B.; Nowak, K.; Bortnik, P.; Jablonska, E. Levels of Biological Markers of Nitric Oxide in Serum of Patients with Mandible Fractures. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2832. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Galil, K.; Loukota, R. Fractures of the mandibular condyle: Evidence base and current concepts of management. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010, 48, 520–526. [CrossRef]

- Kozakiewicz, M.; Gabryelczak, I.; Bielecki-Kowalski, B. Clinical Evaluation of Magnesium Alloy Osteosynthesis in the Mandibular Head. Materials 2022, 15, 711. [CrossRef]

- Neff, A.; Cornelius, C.P.; Rasse, M.; Torre, D.D.; Audigé, L. The Comprehensive AOCMF Classification System: Condylar Process Fractures—Level 3 Tutorial. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2014, 7 (Suppl. 1), S44–S58. [CrossRef]

- Neff, A.; Kolk, A.; Neff, F.; Horch, H.H. Operative vs. konservative Therapie diakapitulärer und hoher Kollumluxationsfrakturen. Vergleich mit MRT und Achsiographie. Mund-Kiefer-Gesichtschirurgie 2002, 6, 66–73.

- Pavlychuk, T.; Chernogorskyi, D.; Chepurnyi, Y.; Neff, A.; Kopchak, A. Biomechanical evaluation of type p condylar head osteosynthesis using conventional small-fragment screws reinforced by a patient specific two-component plate. Head Face Med. 2020, 16, 25. [CrossRef]

- Rasse, M. Diakapitulare frakturen der mandibula. Eine neue operationsmethode und erste ergebnisse. Z Stomatol. 1993, 90, 413–428.

- Skroch, L.; Fischer, I.; Meisgeier, A.; Kozolka, F.; Apitzsch, J.; Neff, A. Condylar remodeling after osteosynthesis of fractures of the condylar head or close to the temporomandibular joint. J. Cranio Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 48, 413–420. [CrossRef]

- Smolka, W.; Cornelius, C.P.; Lechler, C. Resorption behaviour of the articular surface dome and functional outcome after open reduction and internal fixation of mandibular condylar head fractures using small-fragment positional screws. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 46, 1953–1959. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).