1. Introduction

Despite significant advances in materials science (steel, vitalium, titanium alloys) [1, 2], numerous inventions (L-shaped plates, compression plates) [3-10], advances in knowledge [11-14] including biomechanical knowledge [15-18], fixation plates dedicated for mandibular condylar bone fragments still break after osteosynthesis.

Material failure is the most common reason of reoperation after ORIF in mandible [

19]. It may be as high as more than 80% of second surgery in mandible fractures. It seems that the poor fixation and poor reduction are the most responsible factors for that complication. A single straight miniplate should not be used for mandibular condylar fracture fixation [

20]. It is now well established that the golden standard for osteosynthesis of mandibular condylar fractures is the use of not one but two straight plates fixed divergently [21, 22]. However, a plate breakage is a rarely described complication following osteosynthesis of the mandibular condyle. This applies in particular to damage to dedicated plates, which are generally well resistant to breakage [

20].

Loss of fixation stability is functionally catastrophic. It negates all the advantages of ORIF [

23]. Displacement or dislocation (what is worse) of the proximal fragment evoke malocclusion, involving the function of biting by anterior teeth and the function of mastication in ipsilateral side. Less commonly in this anatomical region, damage to fixation stability leads to infection. [

24]. However, abscess formation in the space under the masseter muscle and in the pterygomandibular space can escalate into a life-threatening parapharyngeal abscess.

The authors of the study wanted to determine the conditions under which fixation plates break, which may be important for future designs of plates for osteosynthesis in the mandibular condyle region. The aim of this study is to present a rare complication of osteosynthesis of a mandibular condylar fracture, namely a broken plate.

2. Materials and Methods

Approval was obtained from the bioethics committee of the institution represented by the authors (protocol code RNN/104/25/KE, approved on 15 April 2025). The observational study was reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement [

25].

The selection of clinical material was determined by inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria were: patients presenting mandibular condyle fracture treated by plate osteosynthesis, titanium alloy plates. And exclusion criteria were: only long screw fixation, lack of documentation, no follow-up.

The department's medical records from 2017-2023 identified 238 cases of treatment of condylar fractures that met the inclusion criteria. This group consisted of 57 females and 181 males, with an average age of 45.9±20.3 and 36.5±13.2, respectively (38.8±15.6 years for the entire group). There were 69 rural residents and 169 urban residents. Patients who consumed alcohol prior to injury accounted for 45% of cases. Osteosynthesis was most frequently performed in August (37 procedures) and least frequently in February (4 procedures). Fifteen patients were referred from other maxillofacial surgery departments, while the remaining 223 were diagnosed and treated at the same medical center. All fixing materials were manufactured by ChM (ACP by ChM,

www.chm.eu access date 3 September 2025).

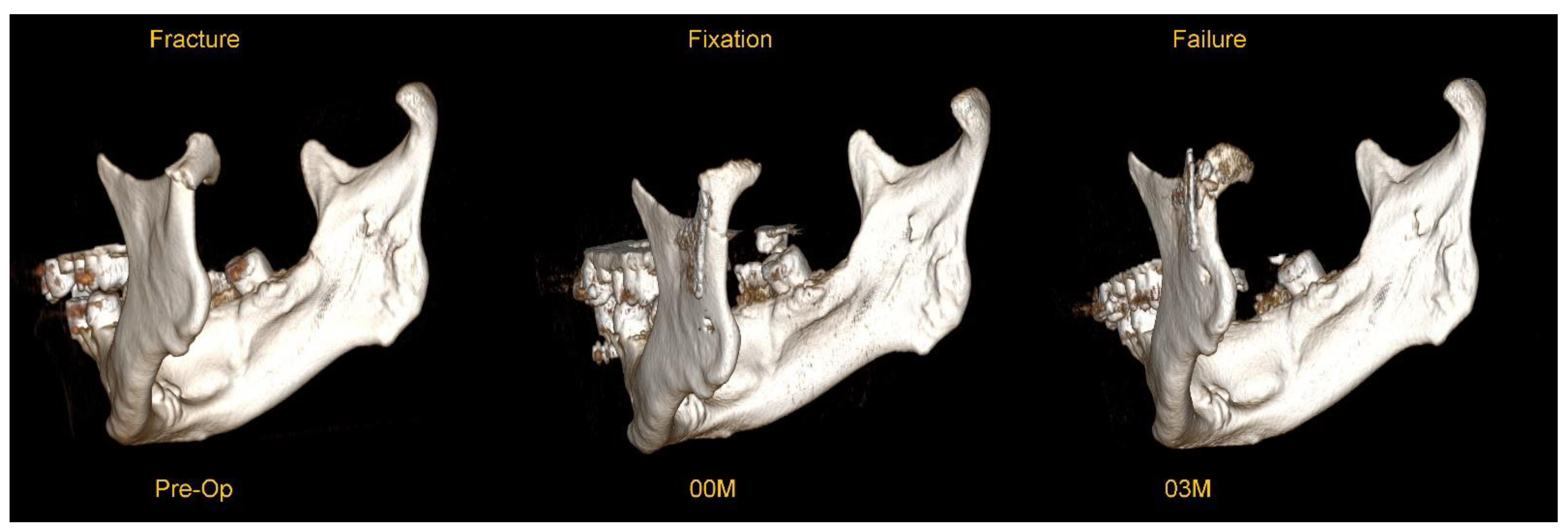

This material was examined for complications in the form of osteosynthesis plate breakage. Typical example of plate breakage is presented below in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

An example of plate breakage after correct osteosynthesis with a dedicated plate for a low-neck fracture of the mandibular condyle. These are three-dimensional reconstructions from a CT scan (RadiAnt software,

www.radiantviewer.com/en access date 3 September 2025). The preoperative image shows a fracture with significant anteromedial displacement. Image 00M shows the immediate result of surgical treatment (open rigid internal fixation) – please note the significant pathological degenerative changes in the joint surface. Image 03M shows a breakage of the plate in the upper part detected 3 months postoperatively - the break line passes through the upper group of holes in the plate (the fracture most often passes through the holes and not the arms of the plate).

Figure 1.

An example of plate breakage after correct osteosynthesis with a dedicated plate for a low-neck fracture of the mandibular condyle. These are three-dimensional reconstructions from a CT scan (RadiAnt software,

www.radiantviewer.com/en access date 3 September 2025). The preoperative image shows a fracture with significant anteromedial displacement. Image 00M shows the immediate result of surgical treatment (open rigid internal fixation) – please note the significant pathological degenerative changes in the joint surface. Image 03M shows a breakage of the plate in the upper part detected 3 months postoperatively - the break line passes through the upper group of holes in the plate (the fracture most often passes through the holes and not the arms of the plate).

The following variables were examined: age, sex, place of residence, cause of injury, alcohol consumption, body mass index, number of co-morbidities, diagnosis, associated mandibular fractures, time interval between injury and surgery, surgical approach, type of osteosynthesis plate used, duration of surgery, facial muscle function [

26], wound healing, Helkimo index [

27], incidents of the plate fracture within 24 months after osteosynthesis, and incidents of reoperation.

Statistical analysis was performed in Statgraphics Centurion 18 (Statgraphics Technologies Inc., The Plains City, Warrenton, VA, USA;

www.statgraphics.com, accessed on 3 September 2025). Statistical analysis consisted of a normality check. The effect of plate breakage on quantitative variables was assessed using one-way analysis of variance (for normal variable distribution) or the Kruskal-Wallis test, while the relationship between breakage and qualitative features was assessed using the χ

2 independence test. In addition, the mechanical excellence factor (MEF) was calculated and, on this basis, the simple regression of the theoretical load capacity was calculated [

28]. The model assumptions are: the raw material is titanium alloy 23, the plate thickness is 1 mm, the plate is cut with a laser, and the plate is fixed exclusively with 2.0 system screws with a length of 6 mm. In this way, an attempt was made to compare 52 models of plates known from the literature. A

p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

In the study group of 238 individuals, plate breakage was observed in 6 cases, which accounts for 2.52%. In these patients, reduction of the fragments was correct in 4 cases, while in 2 cases a wide fracture gap was observed, i.e., reduction was incorrect (Figure 2). It seems that this was the cause of failure in these 2 cases. In the remaining four cases, one plate breakage was caused by an epileptic seizure, while the other three may have been caused by chewing of overly hard foods too early. Data are presented in Table 1 below.

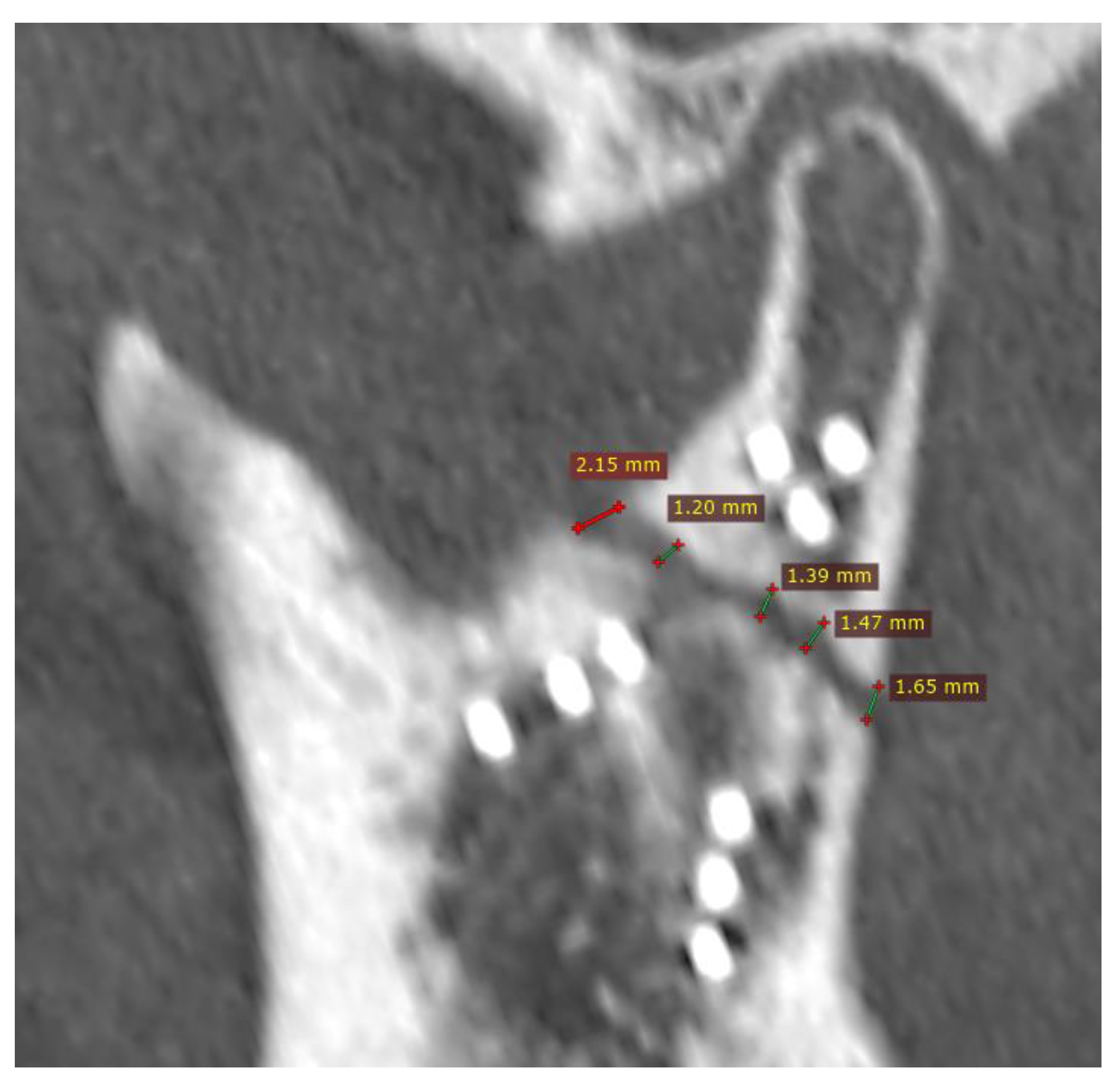

Figure 2.

Fixation with incorrect reduction (CT scan immediately post-operational). Despite fixation with nine screws and the proper head position in the glenoid fossa, load-bearing osteosynthesis was created (this probably caused the plate to break when the patient began masticating hard foods in fourth month post-op). This is the result of a wide fracture gap. The distance between the bone fragments ranges from 1.2 mm to as much as 2.15 mm. It is believed that during fixation of the condylar process after a recent fracture, the gap should be reduced to less than half a millimeter, and ideally to a hairline width. Then, load-shearing osteosynthesis can be expected. It is much more reliable than load-bearing.

Figure 2.

Fixation with incorrect reduction (CT scan immediately post-operational). Despite fixation with nine screws and the proper head position in the glenoid fossa, load-bearing osteosynthesis was created (this probably caused the plate to break when the patient began masticating hard foods in fourth month post-op). This is the result of a wide fracture gap. The distance between the bone fragments ranges from 1.2 mm to as much as 2.15 mm. It is believed that during fixation of the condylar process after a recent fracture, the gap should be reduced to less than half a millimeter, and ideally to a hairline width. Then, load-shearing osteosynthesis can be expected. It is much more reliable than load-bearing.

Table 1.

Clinical material collected for the purpose of analyzing observed breakage of osteosynthesis plate in condylar processes of the mandible.

Table 1.

Clinical material collected for the purpose of analyzing observed breakage of osteosynthesis plate in condylar processes of the mandible.

| Variable |

Stable Osteosynthesis |

Plate Breakage |

Significance |

| Age [years] |

38.55±15.59 |

46.50±17.10 |

p = 0.207 |

| Sex |

Female:Male=53:179 |

Female:Male=4:2 |

p = 0.046 |

| Place of Residence |

Rural:Urban=68:164 |

Rural:Urban=1:5 |

p = 0.827 |

| Primary Injury Reason* |

Assault: 104

Fall: 71

Sport: 5

Vehicle: 46

Workplace: 6 |

Assault: 1

Fall: 4

Sport: 0

Vehicle: 1

Workplace: 0 |

p = 0.437 |

| Intoxicants During Injury |

No:Yes=120:112 |

No:Yes=5:1 |

p = 0.264 |

| BMI [kg/m2] |

23.19±4.39 |

24.73±7.23 |

p = 0.689 |

| Co-Morbidity [n] |

0.4±0.8 |

0.7±0.5 |

p = 0.115 |

| Fracture Diagnosis |

CHF type A: 1

CHF type B: 7

High-Neck: 4

Low-Neck: 33

Base: 187 |

CHF type A: 0

CHF type B: 0

High-Neck: 0

Low-Neck: 2

Base: 4 |

p = 0.753 |

| Condylar Fracture |

Single:Bilateral=181:51 |

Single:Bilateral=6:0 |

p = 0.285 |

| Associated Mandibule Injury |

2.0±0.7 |

1.3±0.5 |

p = 0.024 |

| Delay of Surgery [days] |

8.7±8.5 |

6.2±4.6 |

p = 0.416 |

| Surgical Approach |

Auricular: 1

Ext. Preauricular: 49

Preauricular: 36

Ext. Retromandibular: 35

Retromandibular: 86

Periangular: 8

Intraoral: 17 |

Auricular: 0

Ext. Preauricular: 0

Preauricular: 3

Ext. Retromandibular: 2

Retromandibular: 0

Periangular: 0

Intraoral: 1 |

p = 0.129 |

| Fixing Material |

1 Staight Plate: 4

2 Staight Plates: 73

3 Staight Plates: 5

ACP: 125

XCP: 20 |

1 Staight Plate: 0

2 Staight Plates: 0

3 Staight Plates: 1

ACP: 5

XCP: 0 |

p = 0.405 |

| Duration of Surgery [minutes] |

174±78 |

158±79 |

p = 0.595 |

| House Brackmann Scale 06M |

1.5±1.0. |

2.0±0.0 |

p = 0.266 |

| House Brackmann Scale 24M |

1.0±0.1 |

1.0±0.0 |

p = 0.811 |

| Salivary Fistula |

No: Yes=214:18 |

No: Yes=5:1 |

p = 0.974 |

| Helkimo Index 06M |

0.56±0.85 |

1.5±1.22 |

p = 0.030 |

| Reoperation |

No:Yes=225:13 |

No:Yes=0:6 |

p = 0.001 |

Breaks of the fixing material were found only in single fractures of the condyle, but they were often accompanied by additional fractures in the mandible. The plate fractures were observed in five cases up to six months after surgery (1-6 months post-op). In the sixth case (the one after the epileptic seizure), the accident occurred 11 months after osteosynthesis. It should be emphasized that no fractures of a single straight plate, two straight plates positioned divergently, or an XCP plate were observed (no statistical significance). It is also worth noting that broken plates occurred twice as often in females (p < 0.05). Break of the plates causes deterioration of the functional result (p < 0.05) expressed by the Helkimo Index examined 6 months after the initial surgery (i.e., shortly after secondary surgery due to plate breakage). Second surgery is forced by breakage of the fixation material (p < 0.001).

The plate breakage is not related to facial nerve disfunction. All cases had normal face movements in 24-month follow-up (all patients had 2 in House-Brackmann scale in 6-month examination). A salivary fistula formed in one case of the plate break. Helkimo index was 0 in two cases, 2 in three cases and 3 in one cases of the plate break.

Logistic regression analysis was performed and the relationship between variables and plate breakage was analyzed. The variables studied were: age, place of residence, sex, BMI, co-morbidities, intoxicants use at the time of injury, cause of fracture, diagnosis of condyle injury, number of condyle fractures, associated mandibular fractures, delay in surgery, surgical approach, development of salivary fistula, reoperation, Helkimo index 6 months after surgery, House-Brackmann score 24 months after surgery.

The following factors were found to be independent risk factors for plate breakage: total number of co-existing mandibular fractures, persistent dysfunction expressed as the Helkimo Index score 6 months after surgery, and reoperation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Independent risk factors for osteosynthesis plate breakage in mandibular condylar region.

Table 2.

Independent risk factors for osteosynthesis plate breakage in mandibular condylar region.

| Factor |

χ2

|

Estimated Odds Ratio |

p Value |

| Associated Mandible Injury |

6.921 |

12.765 |

0.0085 |

| Helkimo Index 06M |

6.749 |

0.1974 |

0.0094 |

| Reoperation |

43.135 |

1499.7 |

0.0001 |

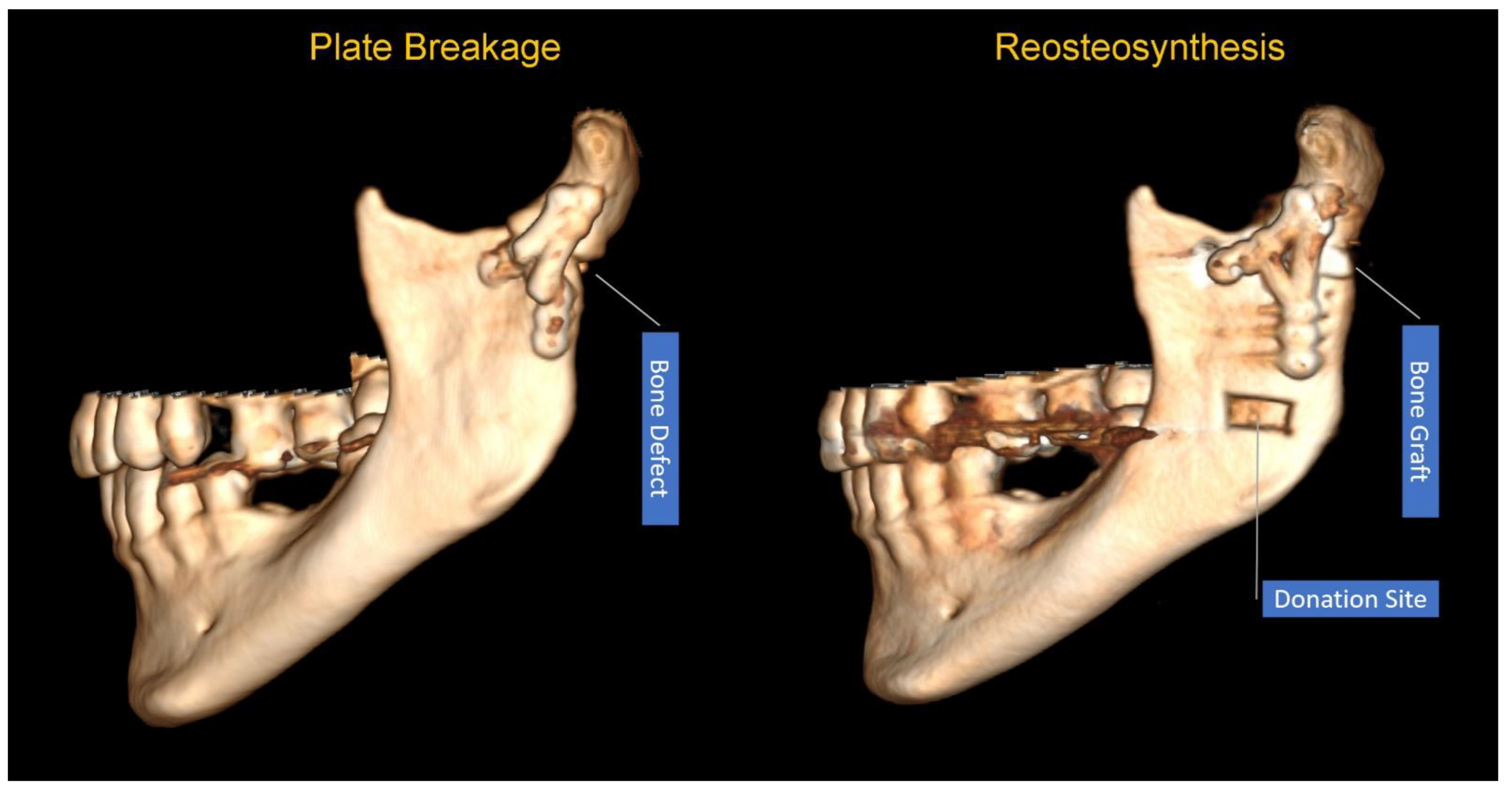

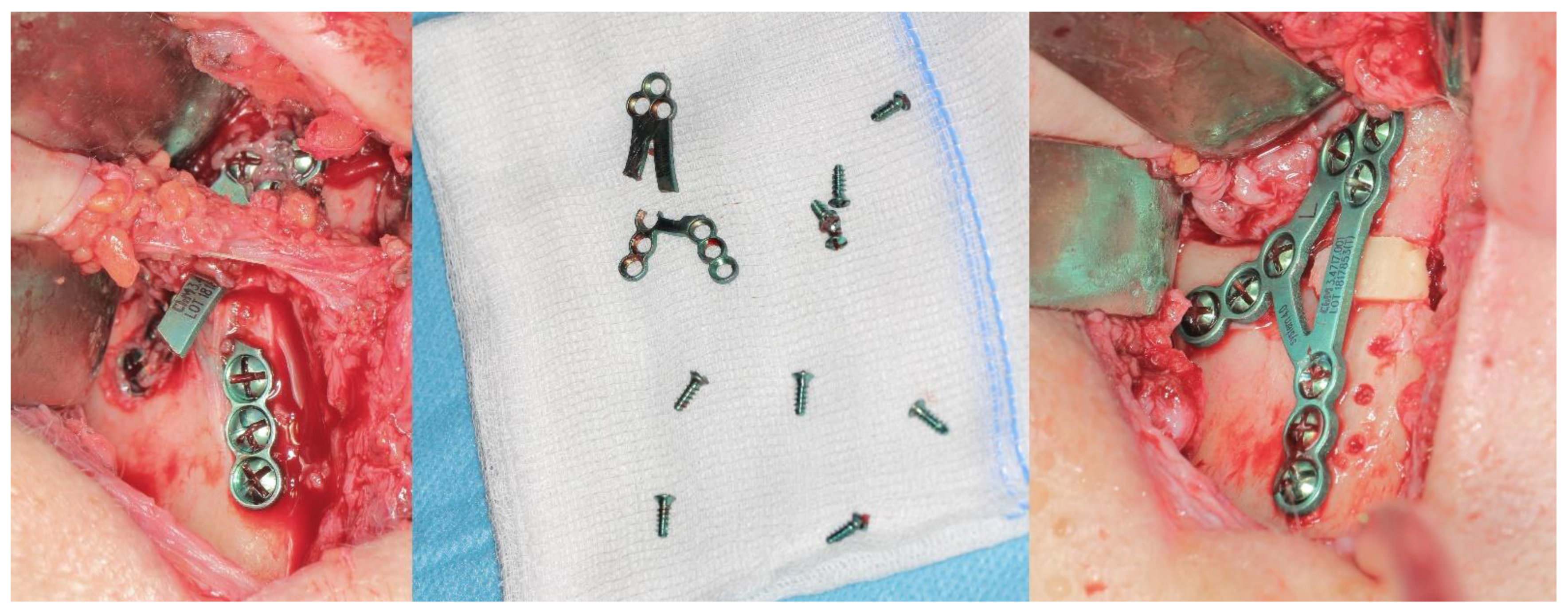

Among the presented cases of plate breakage, reosteosynthesis was performed in four patients. Besides that: once, after removing the plate remnants, union was noticed and a bone shape close to the anatomical form of the condylar process was observed (this was left as it was), and once it was necessary to restore the height of the mandibular neck with a autogenic bone graft (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

The course of the above procedure is shown in Figure 4.

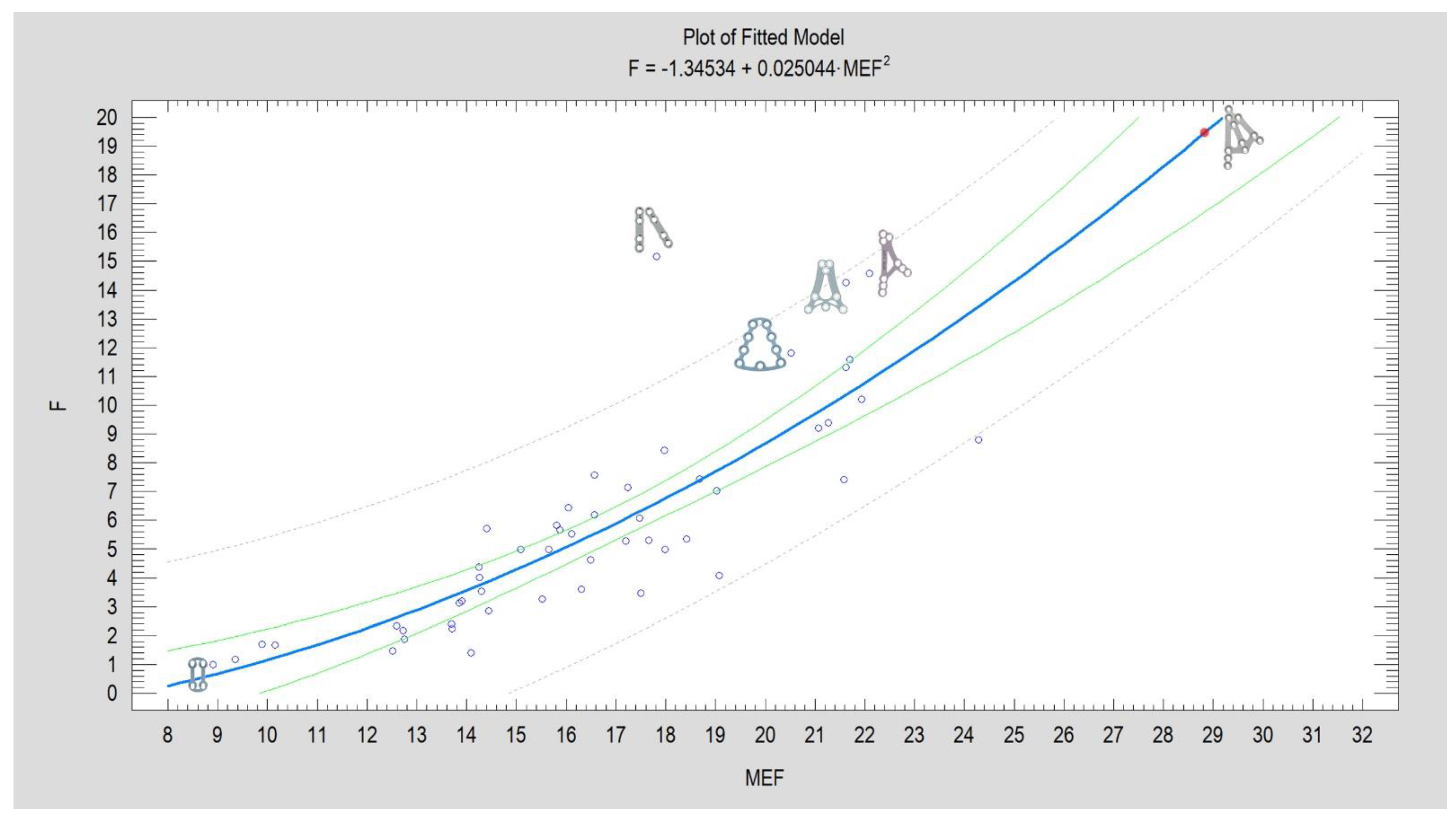

Extrapolation of the force with which the 3AXP plate blocks the displacement of fixed bone fragments by more than 1 mm. For a calculated MEF = 28.775, this force would reach a value of 19.391 N. The result of the regression analysis is presented in Figure 5. For a complete presentation of the data, the statistical significance for the Square X model (p < 0.0001), the correlation coefficient (CC=0.83), and the degree of fit of the model to the experimental data (R2 = 68%) are given. The regression equation is given in the header of the graph below.

Figure 5.

Model of the relationship between the force F (given in units: N) required for 1 mm displacement of fixed fragments (experimental data) and design advantages expressed as the Mechanical Excellence Factor -MEF (number without a unit). Each blue circle on the graph corresponds to one of the currently known shapes of plates used in mandibular condyle osteosynthesis (bibliographic data [

28]). One new plate design, three-axis plate [

31], has been added and marked with a red dot on the plot. Examples of plate shapes illustrating high construction quality (five plates) and low construction values (one plate) have been added next to the circles corresponding to these designs. The blue bold line corresponds to the plot of the calculated regression equation, the green line represents the confidence limit, and the dashed gray line is the prediction limit in this model.

Figure 5.

Model of the relationship between the force F (given in units: N) required for 1 mm displacement of fixed fragments (experimental data) and design advantages expressed as the Mechanical Excellence Factor -MEF (number without a unit). Each blue circle on the graph corresponds to one of the currently known shapes of plates used in mandibular condyle osteosynthesis (bibliographic data [

28]). One new plate design, three-axis plate [

31], has been added and marked with a red dot on the plot. Examples of plate shapes illustrating high construction quality (five plates) and low construction values (one plate) have been added next to the circles corresponding to these designs. The blue bold line corresponds to the plot of the calculated regression equation, the green line represents the confidence limit, and the dashed gray line is the prediction limit in this model.

4. Discussion

The reported frequency of plate breakage in the literature ranges from 0% to 17%, with a tendency for this value to decrease as the number of patients studied increases [32-35]. Breaks in plates occur at their weakest point, i.e., the hole or bend where the plate was fitted to the bone surface. A fracture at the anterior arm of the plate is described, but it appears to be a fracture passing through the hole at the point where the arms of the lambda plate separate on anterior and posterior armes [

34].

Breakage of plates is often described together with loosening of screws as “hardware failure”[

34]. From a clinical point of view, this is very appropriate, but if one would like to assess only the clinical strength of the plate, it is worth focusing only on those cases where the screws hold the plate well and the plate itself breaks. This may provide an answer as to how to improve the design of the plates in the future.

In most cases, this complication depends on the surgeon. In the material described, 1 out of 6 plate breakage cases is the result of an epileptic seizure in the case of drug resistance. Two further cases result from insufficient reduction of the bone fragments. The last three are most likely the result of insufficient supervision of the patient during the six months following the completion of surgical treatment. Thus, most of observed here complication is possible to avoid by surgeon.

More frequent fractures of the plates have been observed in females, although the majority of trauma patients are males. The situation is similar with facial nerve dysfunction after mandibular condyle osteosynthesis [36

, 37]. Females suffer more and for longer. It is difficult to explain this unequivocally. Perhaps, on the one hand, females have a more delicate skeleton and, on the other hand, are more prone to osteoporosis [

38, 39, 40, 41]? The described complications accompanying plate breakage are infection and salivary fistula too. In the material by Hammer et al. [

35] describe many fistulas, in contrast to the clinical material presented in this study. This is probably due to antibiotic prophylaxis regimens [

42], changes in operating room standards, and a significant decrease in the number of plate breakage cases.

The identified independent risk factors for plate breakage can be understood as describing the difficulties in treating multiple and complicated fractures. If the mandibular body is additionally fractured, this significantly destabilizes the stomatognathic system, and osteosynthesis of the body does not always eliminate torsional stresses. Multiple fractures of the mandible and condyles certainly also contribute to long-term abnormal condition of the masticatory muscles [

43, 44]. This further describes another risk factor for plate breakage, which is an elevated Helkimo Index value 6 months after surgery. And reoperations are performed when the fracture proves to be so difficult that, after radiological verification, the fixation needs to be corrected [

34]. The corrective re-open is required as early displacement of fixed fragments or renew dislocation, misalignment, plate malposition, collision of the implant material with the foramen or mandibular canal [45, 46].

Treatment of a patient after a plate break depends on the condition of the bone fragments. The surgeon is faced with either malunion or pseudoarthrosis[

47]. In both cases, treatment is more difficult than primary osteosynthesis. The former situation seems to be better because the bone can undergo osteotomy, reduction, and reosteosynthesis. However, the results of condylar osteotomy [

48] in reoperation are uncertain due to ischemia of bone fragments and a tendency for bone loss. It is also possible to consider leaving the fragments consolidated in a non-anatomical position, ensuring that they do not cause functional impairment (i.e., minor displacement or displacement that can be corrected by prosthetic or orthodontic means). [49, 50]). The last option is to leave the fragments in an improperly consolidated position and plan orthognathic treatment [

51]. The condition for that option is good temporomandibular joint function. In the case of a pseudoarthrosis, the first alternative to consider is bone fragment revision, bone grafting to the defect site, and reosteosynthesis (see

Figure 3). Total alloplastic joint replacement should also be considered as a second treatment alternative [

52]. The higher the pseudoarthrosis is located on the condylar process, the more advisable it is to use a joint replacement [

53, 54].

When searching for preventive actions against plate breakage, structural modification is the first thing that comes to mind [

55]. Plates thicker than the standard 1.0 mm can be manufactured, e.g., 1.2 or 1.3 mm. Such plates dedicated to the mandibular condyle are manufactured by ChM or Medartis. It is worth considering their use. In terms of design modifications, it is certain that the use of plates with bridges without holes protects against breakage. It is also known that plates with round holes fix more rigid than those with oval holes. [

56]. These are just two examples, but general solutions are suggested by the Mechanical Excellence Factor (MEF) analysis. [

28].

The stiffness of any osteosynthetic plate should double or even triple the stiffness of the mandible at the fractured redion to promote physiologic bone growth and healing is the known statement [

57]. About 20 years ago, this recommendation was implemented in the modification of the straight 6-hole plate with a bridge, which works very well in condylar fixations [

58]. Another standard that has been established is plate thickness. It is known that it must be at least 1 millimeter [

59]. In verifying future plate designs for the fixation of mandibular condylar process fractures, the MEF is worth using. It is a combined measure of eight design features (total fixing screw number, number of screws in condylar part, height of the plate, width of the plate, plate surface area, number of round holes in the plate, number of oval holes in the plate, share of oval holes in the total number of holes in the plate). The previous Plate Design Factor [

30] used only four features of plate design and its evaluation loses the effect of oval holes on plate fixation rigidity. And it seems that the influence of oval holes has a negative impact on osteosynthesis rigidity [

40]. The MEF values for a given plate design are strongly related to the measured average value of F

max/dL [

28]. Therefore, it seems to be a good tool to numerically describe the mechanical quality of plate designs. For example, the MEF for a three-axis plate is 28.8 compared to the ACP plate (ACP-T version) 22.1, XCP (XCP Universal 3+5 holes version) 21.9 and the very good large delta TCP (trapezoid pre-shaped 9 holes version, ref. M2-4860) 21.2. A higher value means greater mechanical excellence of the design. For a better understanding of the significance of MEF, it is worth mentioning that for the Gold Standard, i.e., two-plate fixation with straight plates, MEF=17.8. For small 4-hole delta, square, or rhombus plates, MEF takes values between 8.9 and 9.4. Therefore, it is possible to select or make new design a clinically superior solution, i.e., one that is more resistant to breakage. This shows that it is still possible to construct rigid plates from currently available raw materials. And yet there are possibilities to thicken the plate, use grade 2 titanium, avoid cutting at elevated temperatures, e.g., waterjet, use longer screws, e.g., 8 mm, etc.

It indicates that success should be expected when the plate has large dimensions, more than 6 holes for screws, transverse arm connector, short connectors between holes. These are further guidelines for doctors choosing plates for their patients. It is also worth monitoring patients after surgery – this depends on the doctor. Other factors that protect against plate break and depend on the surgeon are: performing fixation along the ideal osteosynthesis line [

16] using the full available bone thickness in the condylar process [

60], performing load-sharing osteosynthesis as opposed to load-bearing osteosynthesis [

31] with perfect reduction of the fracture [59, 39]. This last piece of advice is not applicable in comminuted fractures and difficult to apply in old fractures.

The last thing to know is that any plate can be damaged if the patient is not effectively monitored for 6 months after osteosynthesis for bruxism [61, 62] and maintaining a soft diet. [63-66].

5. Conclusions

Breakage of the osteosynthesis plate is a relatively rare complication, but one that is worth bearing in mind, especially during reduction of bone fragments and during follow-up visits to the outpatient clinic in the six months following surgery.

To reduce the risk of plate fracture in future fixation materials, it is worth considering robust plates in designs. Surgeons should use the most favorable bone conditions to select the plate fixation site, e.g., ideal osteosynthesis lines and areas of bone thickening where longer screws can be inserted.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Paulina Agier and Paulina Pruszyńska; Methodology, Paulina Pruszyńska; Software, Marcin Kozakiewicz; Validation, Paulina Pruszyńska; Formal analysis, Marcin Kozakiewicz, Paulina Agier and Paulina Pruszyńska; Investigation, Paulina Agier and Paulina Pruszyńska; Resources, Marcin Kozakiewicz; Writing – original draft, Marcin Kozakiewicz; Writing – review & editing, Paulina Agier and Paulina Pruszyńska; Visualization, Marcin Kozakiewicz and Paulina Pruszyńska; Supervision, Marcin Kozakiewicz; Project administration, Marcin Kozakiewicz; Funding acquisition, Marcin Kozakiewicz.

Funding

This research was funded by the Medical University of Lodz (grant numbers 503/5-061-02/503-51-001-18 and 503/5-061-02/503-51-001-17).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Medical University of Lodz , RNN/104/25/KE, approved on 15 April 2025

Informed Consent Statement

The study did not involve humans

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ORIFI |

Open Rigid Internal Fixation |

| MEF |

Mechanical Excellence Factor |

| F |

Force |

| N |

Newton unit |

References

- Bigelow, HM. Vitallium bone screws and appliances for treatment of fracture of mandible. J Oral Surg, 1943, 1, 131. [Google Scholar]

- Champy, M.; Lodde, J.P. Syntheses based on mandibular constraints. Rev Stomatol. 1973, 77, 971–979. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.E.; Robinson, M. Individually constructed stainless steel bone onlay splint for immobilization of proximal fragment in fractures of the angle of the mandible. J Oral Surg (Chic). 1954, 12, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.E.; Robinson, M. Stainless steel bone onlay splints for the immobilization of displaced condylar fractures; a new technic: report of three cases, one of ten years' duration. J. Oral Surg (Chic). 1957, 15, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Robinson, M. Immobilization of subcondylar fractures after open reduction. J. South. California Dent. A. 1958, 26, 330. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, M; Yoon, C, New onlay-inlay metal splint for immobilization of mandibular subcondylar fracture. Report of twenty-six cases. Am J Surg, 1960, 100, 6, 845–849. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, M.; Yoon, C. The ’L’ splint for the fractured mandible: a new principle of plating. J Oral Surg Anesth Hosp Dent Serv 1963, 21, 395–399. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, M.; Shuken, R. The L splint for immobilization of iliac bone grafts to the mandible. J Oral Surg. 1966, 24, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Luhr, H.G. The development of modern osteosynthesis. Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir. 2000, 4 Suppl S1, S84–S90, German. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perren, S.M.R.M.; Steinemann, S.; Mueller, M.E.; Allgӧwer, M. A dynamic compression plate. Acta Orthop Scand. 1969, 125 Suppl. 1, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Hansmann, W. A new method for fixing fragments in complicated fractures. Verh Dtsch Ges Chir. 1886, 15, 134. [Google Scholar]

- Matschke, J. , Franke, A., Franke, O.; Bräuer, C.; Leonhardt, H. Methodology: workflow for virtual reposition of mandibular condyle fractures. Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023, 45, 5.

- Luhr, H.G.; Drommer, R.; Hölscher, U. Comparative studies between the extraoral and intraoral approach in compression-osteosynthesis of mandibular fractures. In Hjorting-Hansen E (ed) Oral and maxillofacial surgery. Quintessence, Chicago, 1985, pp 133–137.

- Spiessl, B, Osteosynthese des Unterkiefers. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York. 1988.

- Kessler W: The optical surface layer method for measuring mechanical stress on the human lower jaw under physiological load. PhD Thesis, München, 1980.

- Meyer, C.; Kahn, J.L.; Boutemi, P.; Wilk, A. Photoelastic analysis of bone deformation in the region of the mandibular condyle during mastication. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2002, 30, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilina, P.; Parr, W.C.; Chamoli, U.; Wroe, S. Finite element analysis of patient-specific condyle fracture plates: a preliminary study. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2015, 8, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilina, P.; Chamoli, U.; Parr, W.C.; Clausen, P.D.; Wroe, S. Finite element analysis of three patterns of internal fixation of fractures of the mandibular condyle. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013, 51, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, C.; Welter, M.; Fischer, H.; Goedecke, M.; Doll, C.; Koerdt, S.; Kreutzer, K.; Heiland, M.; Rendenbach, C.; Voss, J.O. Revision Surgery With Refixation After Mandibular Fractures. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2024, 17, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekker, P.; Callahan, N.F.; Miloro, M.; Han, M.D. Which Factors Affect the Reduction Quality of Open Reduction Internal Fixation of Mandibular Subcondylar Fractures? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2023, 81, 1485–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okulski, J.; Kozakiewicz, M.; Krasowski, M.; Zieliński, R.; Wach, T. Which of the 37 Plates Is the Most Mechanically Appropriate for a Low-Neck Fracture of the Mandibular Condyle? A Strength Testing. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.-M.; Chan, M.-Y.; Hsu, J.-T.; Su, K.-C.; Fu, M.-H.; Shen, Y.-W.; Fuh, L.-J.; Tu, M.-G.; Huang, H.-L. Biomechanical Analysis of Subcondylar Fracture Fixation Using Miniplates at Different Positions and of Different Lengths. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwan, H.; Sawatari, Y. What Is the Most Stable Fixation Technique for Mandibular Condyle Fracture? J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 77, 2522.e1–2522.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piombino, P.; Sani, L.; Sandu, G.; Carraturo, E.; De Riu, G.; Vaira, L.A.; Maglitto, F.; Califano, L. Titanium Internal Fixator Removal in Maxillofacial Surgery: Is It Necessary? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Craniofac Surg. 2023, 34, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, J.W.; Brackmann, D.E. Facial Nerve Grading System. Otolaryngol.–Head Neck Surg. 1985, 93, 146–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helkimo, M. Studies on Function and Dysfunction of the Masticatory System. II. Index for Anamnestic and Clinical Dysfunction and Occlusal State. Swed. Dent. J. 1974, 67, 101–121. [Google Scholar]

- Kozakiewicz, M.; Okulski, J.; Krasowski, M.; Konieczny, B.; Zieliński, R. Which of 51 Plate Designs Can Most Stably Fixate the Fragments in a Fracture of the Mandibular Condyle Base? J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozakiewicz, M.; Swiniarski, J. "A" shape plate for open rigid internal fixation of mandible condyle neck fracture. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2014, 42, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozakiewicz, M.; Zieliński, R.; Krasowski, M.; Okulski, J. Forces Causing One-Millimeter Displacement of Bone Fragments of Condylar Base Fractures of the Mandible after Fixation by All Available Plate Designs. Materials 2019, 12, 3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozakiewicz, M. Three-Axis Plate for Open Rigid Internal Fixation of Base Fracture of Mandibular Condyle. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikora, M.; Sielski, M.; Stąpor, A.; Chlubek, D. Use of the Delta plate for surgical treatment of patients with condylar fractures. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2016, 44, 770–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zrounba, H.; Lutz, J.C.; Zink, S.; Wilk, A. Epidemiology and treatment outcome of surgically treated mandibular condyle fractures. A five years retrospective study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2014, 42, 879–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhadauria, FT. ’ Dhupar, V.; Akkara, F.; Kamar, S.M. Efficiency of the 2-mm Titanium Lambda Plate for Open Reduction and Internal Fixation of Subcondylar Fractures of the Mandible: A Prospective Clinical Study. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2022, 21, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, B.; Schier, P.; Prein, J. Osteosynthesis of condylar neck fractures: a review of 30 patients. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1016. [Google Scholar]

- Agier, P.; Kozakiewicz, M.; Tyszkiewicz, S.; Gabryelczak, I. Risk of Permanent Dysfunction of Facial Nerves After Open Rigid Internal Fixation in the Treatment of Mandibular Condylar Process Fracture. Med. Sci. 2025, 13, 121. [Google Scholar]

- Imai, T.; Fujita, Y.; Takaoka, H.; Motoki, A.; Kanesaki, T.; Ota, Y.; Chisoku, H.; Ohmae, M.; Sumi, T.; Nakazawa, M.; Uzawa, N. Longitudinal Study of Risk for Facial Nerve Injury in Mandibular Condyle Fracture Surgery: Marginal Mandibular Branch Traversing Classification of Percutaneous Approaches. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 1445–1454. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hanba, C.; Svider, P.F.; Chen, F.S.; Carron, M.A.; Folbe, A.J.; Eloy, J.A.; Zuliani, G.F. Race and Sex Differences in Adult Facial Fracture Risk. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2016, 18, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, C.; Zink, S.; Chatelain, B.; Wilk, A. Clinical experience with osteosynthesis of subcondylar fractures of the mandible using TCP plates. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2008, 36, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeman, E. Pathogenesis of bone fragility in women and men. Lancet 2002, 359, 1841–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, T.F. The Bone–Muscle Relationship in Men and Women. J. Osteoporos 2011, 2011, 702735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goormans, F.; Coropciuc, R.; Vercruysse, M.; Spriet, I.; Willaert, R.; Politis, C. Systemic Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Maxillofacial Trauma: A Scoping Review and Critical Appraisal. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauria, P.; Carone, C.; Cardarelli, F.; Sguera, N.; Memè, L.; Bambini, F.; Fernandes, G.V.O.; Bordea, I.R.; Del Vecchio, M.; Qorri, E.; Almasri, L.; Alkassab, M.; Almasri, M.; Palermo, A. Impact of Mandibular Condylar Fractures on Masticatory Muscle Function: A Narrative Review. Open Dent. J. 2024, 16. (3.1 Suppl), 204–217. [Google Scholar]

- Inchingolo, F.; Patano, A.; Inchingolo, A.M.; et al. Analysis of Mandibular Muscle Variations Following Condylar Fractures: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hasani, K.M.; Bakathir, A.A.; Al-Hashmi, A.K.; Albakri, A.M. Complications of Open Reduction and Internal Fixation of Mandibular Condyle Fractures in Oman. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2024, 24, 338–344. [Google Scholar]

- Tatsumi, H.; Matsuda, Y.; Toda, E.; Okui, T.; Okuma, S.; Kanno, T. Postoperative Complications following Open Reduction and Rigid Internal Fixation of Mandibular Condylar Fracture Using the High Perimandibular Approach. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throckmorton, G.S.; Ellis, E. , 3rd. Recovery of Mandibular Motion after Closed and Open Treatment of Unilateral Mandibular Condylar Process Fractures. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2000, 29, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo X, Bi R, Jiang N, Zhu S, Li Y. Clinical outcomes of open treatment of old condylar head fractures in adults. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2021, 49, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basdra, E.K.; Stellzig, A.; Komposch, G. Functional treatment of condylar fractures in adult patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998, 113, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.H.; Tai, K.; Sato, Y. Orthodontic treatment of a patient with severe crowding and unilateral fracture of the mandibular condyle. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2016, 149, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, K.; Tamura, H.; Watahiki, R.; Ogura, M. A surgical technique using vertical ramus osteotomy without detaching lateral pterygoid muscle for high condylar fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002, 60, 709–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruszyńska, P.; Kozakiewicz, M.; Szymor, P.; Wach, T. Personalized Temporomandibular Joint Total Alloplastic Replacement as a Solution to Help Patients with Non-Osteosynthesizable Comminuted Mandibular Head Fractures. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercuri, L.G. Alloplastic temporomandibular joint replacement: Rationale for the use of custom devices. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 41, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidebottom, A.J. Current thinking in temporomandibular joint management. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009, 47, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasundram, S.; Kovilpillai, F.J.; Royan, S.J.; Ma, B.C.; Gunarajah, D.R.; Adnan, T.H. A 4-Year Multicentre Audit of Complications Following ORIF Treatment of Mandibular Fractures. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2020, 19, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozakiewicz, M.; Świniarski, J. Finite Element Analysis of Newly Introduced Plates for Mandibular Condyle Neck Fracture Treatment by Open Reduction and Rigid Fixation. Dent. Med. Prob. 2017, 54, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.; Krach, W.; Schicho, K.; Undt, G.; Ploder, O.; Ewers, R. A 3-dimensional finite-element analysis investigating the biomechanical behavior of the mandible and plate osteosynthesis in cases of fractures of the condylar process. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002, 94, 678–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seemann, R,; Schicho, K. ; Reichwein, A.; Eisenmenger, G.; Ewers, R.; Wagner, A. Clinical evaluation of mechanically optimized plates for the treatment of condylar process fractures. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007, 104, e1–e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Undt, G.; Kermer, C.; Rasse, M.; Sinko, K.; Ewers, R. Transoral miniplate osteosynthesis of condylar neck fractures. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999, 88, 534–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielecki-Kowalski, B.; Kozakiewicz, M. Clinico-anatomical classification of the processus condylaris mandibulae for traumatological purposes. Ann Anat. 2021, 234, 151616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artas, A.; Aslan, E.M. Impact of Bruxism on the Mandibular Angle and Condylar Structures: A Panoramic Radiographic Assessment. Oral Radiol. 1007. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, K. Movement Disorders in the Stomatognathic System: A Blind Spot between Dentistry and Medicine. Dent. Med. Probl. 2024, 61, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzon, T. The issue of the advisability of surgical treatment of mandibular condylar fractures in the light of clinical and experimental studies, Habilitation PhD Thesis, Medical University of Lodz, 1966.

- Winstanley, R.P. The management of fractures of the mandible. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1984, 22, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhard, J.P.M.; Koba, S.; Schlittler, F.; Iizuka, T.; Schaller, B. Clinical results of two different three-dimensional titanium plates in the treatment of condylar neck and base fractures: A retrospective study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2020, 48, 756–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prysiazhniuk, O.; Palyvoda, R.; Chepurnyi, Y.; Pavlychuk, T.; Chernogorskyi, D.; Fedirko, I.; Sazanskyi, Y.; Kalashnikov, D.; Kopchak, A. War-related maxillofacial injuries in Ukraine: a retrospective multicenter study. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2025, 26, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).