Introduction

Natural selection in the strictly Darwinian sense refers to the process through which beneficial changes occurring in organismal individuals cause the cognate individuals to have more descendants than their peers through enhanced survival and/or reproduction. Reiteration of this process in successive generations causes an increasingly higher proportions of individuals to inherit and express the beneficial traits, eventually leading to their population-wide fixation. Integration of natural selection with Mendelian genetics has led to the theory of modern synthesis (Koonin, 2009; Lewontin, 1974), which further specifies that beneficial phenotypes correspond to changes in the genomic DNA sequences of the underlying organisms, accounting for their heritability. A traditionally less emphasized aspect of natural selection is the purifying selection against deleterious variations (mutations), which was later integrated into the neutral theory of molecular evolution by Kimura and his followers (Kimura, 1983).

Kimura and colleagues first inspected the variations of orthologous proteins in different conspecific populations, and realized that most protein-coding genes exist as multiple non-identical homologues, or alleles, in these populations. They further demonstrated that the relative frequencies of these co-existing alleles are mainly governed by stochastic forces rather than selection (Kimura, 1983). Based on these findings, Kimura and others put forward the neutral theory of molecular evolution arguing that most of the variations (mutations) at the genomic DNA sequence level are neutral or near neutral, and their persistence in living populations or species are dictated by random genetic drift, meaning they can be lost or become fixed purely by chance, independently of natural selection.

The modern synthesis theory, despite many salvaging attempts (e.g. Müller, 2017), is being increasingly recognized as untenable. By contrast, the neutral theory has gained widespread support from the rapidly accumulating sequencing data of genomes of diverse organisms (Jensen et al., 2019; Koonin, 2009), and became the basis of modern-day population genetics (Hartl and Clark, 1989). However, there are still questions that cannot be satisfactorily answered with the neutral theory. For instance, the ample evidence in support of natural selection gleaned from phylogenetic analysis of orthologous genes cannot be easily dismissed. More critically, while Kimura and colleagues readily acknowledge the role of purifying selection against deleterious mutations, they appear to have completely ignored the potential impact of lethal variations or mutations.

Here we propose a novel hypothesis, designated unified model (UM), that features a prominent role of lethal variations in the evolution of all forms of life. We lay out the case that contrary to intuition, most potentially lethal variations have little chance to express the encoded lethality at the time of their emergence, thus are not immediately eliminated from the cognate populations. Being phenotypically masked, these potentially lethal variations are subjected to the same fate as neutral or near neutral mutations. As a result, a substantial proportion of them can be stochastically retained, or even reach fixation, in the populations. Accordingly, an organismal population/species must equip themselves with a mechanism that removes these lethal variations on a regular basis, thereby minimizing their population-wide allele frequencies. We argue that bottlenecked reproduction constitutes such a surveillance mechanism. While we believe this UM framework applies to all living organisms, we choose to focus our current essay on single-celled bacteria with haploid genomes. We shall deliberate how other organisms conform to UM in separate future discussions.

Definitions

Before diving into specific examples, it is important to clearly define what we mean by lethal variations or mutations. We define lethal variations as genetically inheritable variations that, upon expression of the encoded lethal phenotypes, cause the variation-carrying individuals to die or cease reproduction (aka to be sterile). From this definition derive two broad categories of lethal variations. The first category encompasses lethal variations in essential genes, such as DNA-dependent DNA polymerase genes, whose occurrence always result in deaths or sterility in haploids. They are hereby designated as obligately lethal variations (OLVs). Due to their instant lethality, OLVs are unlikely to persist in haploid bacteria. As a result, they are mostly detected and studied as newly arising mutations, many of them experimentally created.

The second category comprises variations whose lethal phenotypes are only expressed under certain conditions, hence are designated as conditionally lethal variations (CLVs). These conditions may include sudden exposure to toxic substances, such as antibiotics and mutagens (e.g. UV light), host-derived defense compounds, antibodies, and immune cells; as well as dramatic changes in temperature, light, humidity, pH, nutrients, or predator incursions. Note that CLVs can be single variations/mutations in single genes, or two or more variations that bring about deaths/sterility only when they co-exist in the same individual. We wish to note that for brevity, this essay will only discuss variations that lead to definitive deaths or sterility under appropriate conditions. We will leave discussions on deleterious variations that do not lead to immediate deaths/sterility for another occasion, where we will argue that such deleterious variations can be treated as lethal variations that inflict deaths/sterility in less than 100% of affected individuals.

Haploid Bacterial Genomes Compel Immediate Removal of OLVs, But Not CLVs

We begin with the single-celled bacteria harboring haploid genomes. Because of the haploid nature of their genomes, most genes exist in these bacterial cells as single copies. As a result, an OLV is expected to express the lethal phenotype as it emerges, causing the variation (mutation)-carrying individual to die or cease reproduction. This in turn excludes the OLV from the descendant population. Therefore, OLVs emerging in a haploid bacterial population are bound to be short-lived, thus should have little evolutionary consequence. However, it is worth emphasizing that the instant purging of OLVs can only occur thanks to the haploidy of the affected genome. As will be discussed later, haploidy is by itself a form of bottlenecked reproduction favored by specific environments. While beyond the scope of this short essay, it is well known that many polyploid bacteria and archaea flourish in certain unique environments (Volland et al., 2022).

However, most lethal variations are CLVs, meaning they do not manifest their lethal phenotypes unless being exposed to certain conditions. As an example, let us examine antibiotic resistance. Common bacterial pathogens reproduce prolifically in the absence of antibiotics but mostly succumb to antibiotics treatment. Still, for a given antibiotic, a few individuals often survive to amplify themselves into lineages that are resistant to this antibiotic. This has been taken as an example of positive selection even by Kimura (1983). Yet we hold the contrarian view that bacterial individuals of the pre-treatment population mostly harbor CLVs whose lethal phenotypes are masked by antibiotic-free environments. In such environments, the fate of these selectively neutral variations is dictated by stochastic forces (Kimura, 1983), thus reaching fixation through pure luck. Conversely, exposure to an antibiotic compels the expression of the lethality encoded by these CLVs, hence their clearance by purifying selection. Following the same logic, it would not be surprising if a pre-treatment population contains rare individuals with genes or gene alleles that are phenotypically neutral in the absence of the antibiotic, but confer varying degrees of resistance in its presence.

If you are not convinced by the above example, let us move to the next one. Many animal- and plant-pathogenic bacteria, such as enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and the plant-pathogenic Pseudomonas syringae, encode Type 3 secretion systems (T3SS) that transfer dozens of bacterial effector proteins into host cells to suppress host immunities and bolster infection successes (Deng et al., 2017; Galán and Bliska, 1996; Puhar and Sansonetti, 2014). The T3SS machinery is made up of more than 30 different proteins that together form a syringe-like injection apparatus. T3SS is absolutely required for these bacteria to colonize their hosts, yet loss-of-function mutations in T3SS protein components, as well as the effectors secreted by T3SS, rarely compromise bacterial fitness in in vitro cultures (Czechowska et al., 2014). These mutations are CLVs because they only become lethal when the mutation-bearing bacteria attempt to colonize host tissues.

Conditional loss-of-function mutations in T3SS genes and T3SS-secreted effectors can arise and persist even inside the infected host tissues, and can afford competitive advantages to mutation-carrying bacteria under certain conditions (Czechowska et al., 2014; Rundell et al., 2016). This is because the effectors are exported to spaces outside of individual bacterial cells to exert their activities. As a result, they can be shared among all individuals colonizing the same infection site. Consequently, bacterial individuals that shirk the responsibility of producing or secreting functional effectors through loss-of-function mutations can still flourish by taking advantage of effectors secreted by co-colonizing sibling cells, unless a surveillance mechanism exists that diligently roots out mutant individuals. More ominously, absent of such surveillance, the numbers and population-level frequencies of such CLVs can rise steadily through rapid bacterial reproduction. This is because existing CLVs can become fixed through genetic drift, and pyramided by newer CLVs that continuously emerge and drift (though most of them should drift to extinction). Given the short generation times of bacteria, it would not take long for the underlying bacterial population to be overburdened by such CLVs, ultimately leading to their collective failure to colonize host tissues, and possibly extinction of entire population/species.

Inter-bacterial sharing of extracellular goods such as T3SS-secreted effectors is very common among bacteria. Another well-studied example is quorum sensing (QS), which operates in both free-floating (planktonic) bacterial populations and inside host tissues (Mukherjee and Bassler, 2019). QS enables bacterial individuals to monitor population densities in the same micro-environment and adjust their behaviors accordingly to synchronize the expression and/or repression of certain products crucial for bacterial survival and reproduction. QS is thought to play an important part in the social behaviors of many, if not most, bacteria, including synchronizing T3SS secretion that maximizes bacterial fitness in micro-environments exposed to host defenses.

QS is encoded in bacterial genomes as complex systems comprising genes that direct the synthesis of QS signal molecules (aka autoinducers), as well as cognate receptors that sense and respond to the signals. For instance, the opportunistic pathogen P. aeruginosa encodes at least a dozen genes that together make up four distinct QS systems, producing and responding to at least five different autoinducers (Lin and Cheng, 2019). Given the fact that autoinducers are shared goods in a bacterial colonization site, loss-of-function mutations in at least some of QS system genes are CLVs. For example, individuals lacking an autoinducer-synthesizing enzyme could still detect and respond to autoinducers produced by their wildtype peers to maximize their own fitness in an environment shared by many conspecific bacteria. Such cheaters must be rigorously policed to minimize the population-wide accumulation of CLVs and pyramiding of different CLVs affecting multiple QS genes (Mukherjee and Bassler, 2019).

Lethal Mutation Surveillance Through Bottlenecked Reproduction

Haploidy as a form of bottlenecked reproduction. Bottlenecked reproduction is a widely shared feature of multi-cellular organisms, though its natural selection imperative has not been carefully examined. To illustrate bottlenecked reproduction in bacteria, we return to the fact that bacteria with haploid genomes instantly wipe out OLV-containing individuals. Haploidy can be viewed as a form of bottlenecked reproduction that limited the reproducing genome copy to one in each cell, and such bottlenecked reproduction has likely outcompeted alternative arrangements because it constitutes the most efficient means of purging OLVs, hence shared by most bacteria examined by scientists. Simply put, the haploid arrangement bottlenecks the number of reproducing genomes to one per cell. For bacteria with relatively small genome sizes, rapid reproduction cycles, large population sizes, and propagating in relatively constant environments, haploid genomes facilitate real-time expulsion of few newly emerging OLV-carrying individuals from the populations, thereby sustaining the populations as OLV-free.

The selective advantage of a haploid genome under these conditions is further evident because replicating a haploid genome is most cost-effective compared to diploid or polyploid genomes. A diploid or polyploid genome may have a transient advantage as they shield loss-of-function OLVs from immediate expression of lethality (by converting them into recessive CLVs). As a result, individual lineages with diploid and polyploid genomes can initially reproduce for more generations. But eventually they all become functionally haploid by accumulating lethal mutations in redundant alleles (Birdsell and Wills, 2003; Charlesworth and Charlesworth, 2010). Upon reaching this point, those with diploid or polyploid genomes would lose the transient advantage of prolonged lineage survival. By then the extra costs of having to replicate genomes that are twice or multiple times larger render them less competitive than haploids. Thus, under conditions that are free of frequent, irregular fluctuations, bacteria with haploid genomes are mostly favored by natural selection. Nevertheless, we hasten to note that haploidy is by itself conditional – under certain extreme conditions polyploidy can have unique advantages (Volland et al., 2022).

Colony-level bottlenecked reproduction exposes bacterial CLVs to purifying selection. How might CLVs, such as those affecting genes encoding T3SS components, effectors mobilized by T3SS, and QS, be exposed to purifying selection? The existing literature frames mutant bacteria carrying such CLVs as cheaters because they exploit their wildtype peers to advance their own preferential proliferation (Mukherjee and Bassler, 2019; Rundell et al., 2016). Czechowska and colleagues (2014) observed that mutant bacteria with defective T3SS were frequently recovered from patients infected with P. aeruginosa. These mutants were unable to infect otherwise susceptible hosts (mice) by themselves. However, when mixed with their wildtype counterparts, they initially outcompeted the wildtype bacteria in infected animals, though this competitive advantage disappeared as the mutant bacteria became dominant. These experiments demonstrated that the mutant bacteria were avid cheaters but could not sustain cheating without enough wildtype peers supplying shared goods. These findings thus provide hints for a purging strategy that deprives cheaters of shared goods – by forcing them to become dominant through colony-level bottlenecking of reproduction.

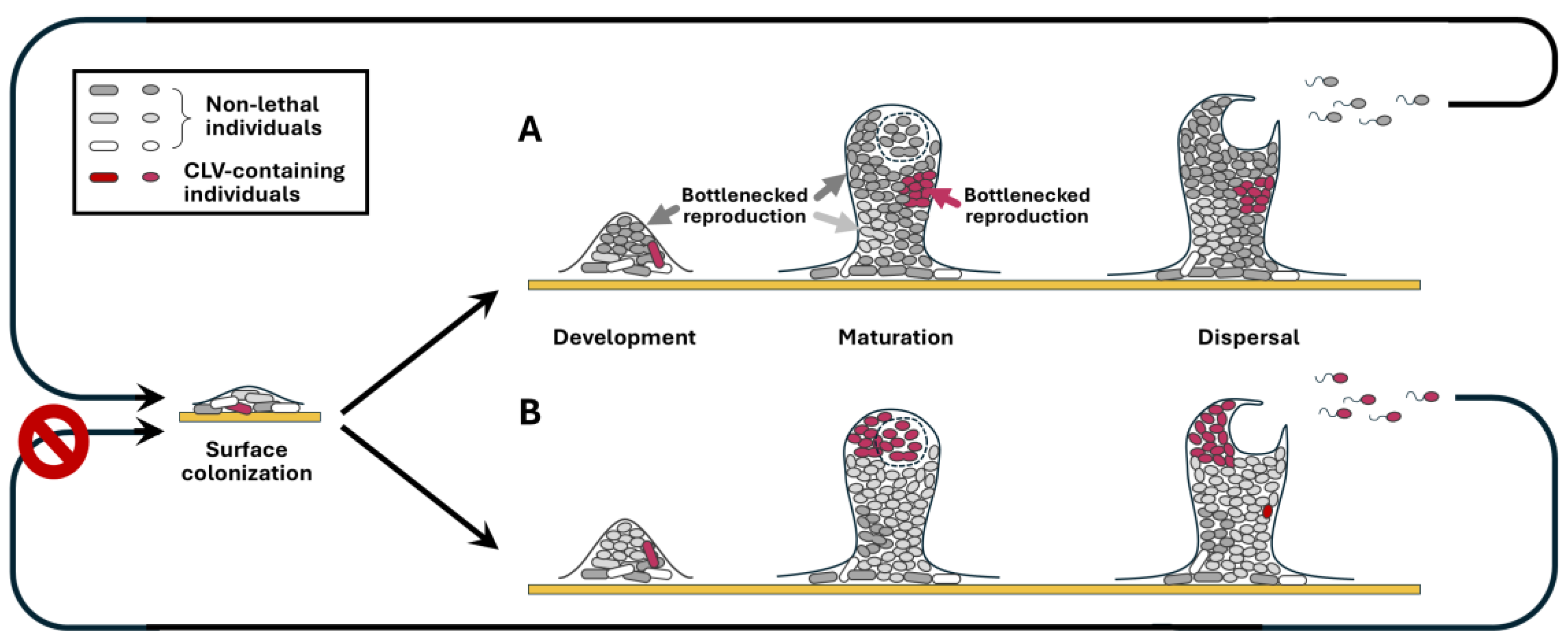

These and other studies inspired us to propose that most bacteria undergo bottlenecked reproduction at the site of colonization, permitting a tiny fraction of co-colonizing bacterial individuals to reproduce. Although the composition of such colonization sites may not be as clonal as individual bacterial colonies growing on solid media, we still refer to such bottlenecked reproduction as colony-level bottlenecking for lack of a more accurate term. Specifically, we advocate that most conspecific bacterial individuals sharing the same colonization site are non-reproducing or reproduce for so few cycles that their progeny occupy a negligible proportion of the descendant population (

Figure 1). Instead, they mostly serve supportive roles, such as collectively secreting toxins, defense-suppressing effectors, QS autoinducers, extracellular polysaccharides, and other colony-building substances. In such colonies, exponential reproduction only occurs with very few random bacterial individuals, causing the descendant population to be dominated by few progeny lineages, each with their unique subset of CLVs (

Figure 1).

Such colony-level reproductive bottlenecking is likely evolutionarily reinforced, thus genetically programmed, for several reasons. First, by restricting reproduction to a small number of founding individuals, it excludes most CLVs (of course also most potentially beneficial variations) from the descendant populations. Second, it immediately exposes CLVs that do transmit into the few amplified progeny lineages to purifying selection in the subsequent colonies they cooperatively construct. This is because, with a given CLV now carried by most or all descendants (

Figure 1B), the new colonization site will now experience a substantial shortfall, or a total loss, of shared goods. This then leads to inefficient reproduction at the new colonization site, or even total abolition of the new site, and consequently reduction or elimination of CLV-carrying individuals in the new progeny populations. As an aside, such colony-level reproductive bottlenecking also allows potentially beneficial variations to exhibit their encoded benefits, should the beneficial-variation-carrying individual be the one to escape the reproductive bottlenecks to amplify itself. In conclusion, colony-level bottlenecked reproduction would be a compelling natural selection solution to minimize allele frequencies of CLVs.

Biofilms as Potential Sites of Colony-Level Bottlenecked Reproduction

Biofilms are complex structures that protect the resident bacteria from adverse environments and bactericidal agents such as antibiotics, host-borne defense compounds, and immune cells (Flemming et al., 2016; Stoodley et al., 2002). Biofilms can be formed by bacteria in liquids, on solid surfaces such as interiors of water pipes, medical examination equipment; or in patient tissues such as burned skin or surgical implants. They are assembled through cooperative actions of numerous bacterial individuals that collectively secrete or release extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), including polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and DNA (Flemming et al., 2016). Importantly, bacteria inside biofilms have been shown to differentiate into subpopulations that perform highly specialized tasks (van Gestel et al., 2015). Therefore, biofilm construction is a form of sophisticated social coordination among hundreds to thousands of bacterial individuals. It is easy to see that this type of sociality is highly conducive to cheaters, thus demands diligent surveillance against cheating.

Research on the single-species/isolate biofilms formed by P. aeruginosa yielded intriguing results that are consistent with the occurrence of colony-level bottlenecked reproduction in these biofilms (Klausen et al., 2003). These authors engineered two isogenic lineages of P. aeruginosa (isolate PAO1) that were tagged with yellow and cyan fluorescent proteins (Yfp and Cfp), respectively, and used a 1:1 mixture of the two to induce biofilms under minimal nutrient condition. These biofilms were induced in a device called flow chamber to permit observation with confocal microscopy. The induced biofilms initially appeared as a lawn containing both Yfp- and Cfp-tagged cells. However, small multicellular bumps, referred as microcolonies, subsequently emerged from the biofilm lawn. Notably, cells of these microcolonies were either Yfp- or Cfp-tagged, but never both. Since the initial biofilm lawn contained both types of isogenic cells nearly evenly mixed, the authors concluded that each of the microcolonies, rather than reflecting localized congregation of multiple founding cells, must have resulted from repetitive division of a single founding cell (Klausen et al., 2003). Put differently, only one of the multiple biofilm-inducing cells present in the vicinity had the chance to reproduce into the multi-celled microcolony. Thus, such microcolonies arose from bottlenecked reproduction within the biofilm environment.

These microcolonies would eventually develop into discrete mushroom-shaped mounds. Apparently, as the mushroom mounds rose in heights, some of the non-dividing founding cells migrated along. This is because cell clusters with a distinct fluorescent tag were frequently observed on sides or tops of the mushroom mounds dominated by the alternate fluorescent tag (Klausen et al., 2003;

Figure 1). Again these cell clusters contained cells with either a Yfp- or a Cfp-tag, but not both. Therefore, they too were products of localized, bottled reproduction at their respective positions (Klausen et al., 2003).

The reproductive bottlenecking in these mushroom mounds was probably further augmented at the dispersal step (

Figure 1). The mushroom mounds are thought to be functionally similar to fruiting bodies formed by other bacteria and single-celled fungi, thus likely serving the purpose of dispersing amplified individuals to more distant locations (van Gestel et al., 2015). Indeed, it was shown that many cells in the caps of

P. aeruginosa-induced mushroom mounds eventually underwent controlled autolysis to form a cavity from which the cells located at the very center, known as swimming cells, were dispersed (Ma et al., 2009; Stoodley et al., 2002). This suggests that even though bottlenecked reproduction could occur at multiple sites of a mushroom mound, only the descendant cells at the center of the cap had the chance to further reproduce at new colonization site(s).

Taken together, the premise of bottlenecked reproduction is highly consistent with published works on biofilms of P. aeruginosa and other bacteria (van Gestel et al., 2015). This in turn suggests that biofilms are likely sites where many bacteria undergo colony-level reproductive bottlenecking to purge CLVs affecting inter-bacterial cooperations.

Evidence in Support of Colony-Level Bottlenecked Reproduction Inside Hosts of Bacterial Pathogens

The concept of colony-level bottlenecked reproduction is not only supported by observations made with P. aeruginosa biofilms generated in vitro. It is also consistent with the findings of a recent study examining the bacterial population dynamics in infected animals (Aggarwal et al., 2023). Authors of this study constructed a Streptococcus pneumoniae (Spn) population consisting of 2,764 isogenic variants distinguishable from each other by virtue of unique chromosomal barcodes. They then used this Spn population to colonize the nasopharynx of infant mice. They found that “within 1 day post inoculation, diversity was reduced >35-fold with expansion of a single clonal lineage.” (Aggarwal et al., 2023). More importantly, the authors found that the dramatic loss of diversity could not be explained by relative clonal abundance, genetic drift, or in vivo adaptation, thus suggesting stochastic bottlenecking as a possible cause. Interestingly, although Spn is a gram-positive bacterium lacking T3SS, Spn individuals have been shown to secrete large numbers of virulence factors into extracellular spaces to ensure successful colonization. More strikingly, similar to the biofilm-residing P. aeruginosa, many Spn individuals also commit suicidal autolysis to release effectors that aid in the survival and reproduction of others (Brooks and Mias, 2018).

How Does Colony-Level Bottlenecked Reproduction Occur?

We next consider how bacterial individuals sharing the same colonization environment, such as a mushroom mound in P. aeruginosa biofilms, coordinate among themselves to enforce bottlenecked reproduction. More specifically, how such coordination precludes most participating individuals from yielding progeny. In the case of P. aeruginosa mushroom mound, the very few bacterial individuals that escape bottlenecking each multiplied to form unique descent lineages at different positions of the mound. Such localized bottlenecking could occur if all (or most) participating bacterial individuals secrete one or more repressive QS signals that at appropriate local concentrations act to prohibit the multiplication of nearby cells. As a result, cells that are located at the periphery of the biofilm matrix may encounter signifcantly lower concentrations of the said QS signals, thus could be freed from repression to commence reproduction.

An alternative, but not mutually exclusive possibility is that the QS signals may induce autolysis of cells in the vicinity. This would in turn reduce the number of live cells capable of secreting the said QS signals. Consequently, the suicide-inducing QS signals would gradually diminish, allowing the few surviving cells to commence reproduction unhindered. Consistent with the latter scenario, Aggarwal and colleagues (2023) demonstrated that deletion of the blp locus from Spn caused a 5-fold increase in the diversity of barcoded clones recoverable from infected mice at 1 day post inoculation, suggesting a drastic relaxation of reproductive bottlenecks. The blp locus of Spn encodes numerous bacteriocin peptides that mediate the killing of bacterial cells in the close vicinity. Moreover, the expression of blp locus genes is known to be induced by the QS signaling peptide BlpC. Accordingly, deletion of the blpC gene likewise caused substantial elevation of clonal diversities in infected mice. Together these findings strongly suggest that bottlenecked reproduction in biofilms and intra-host colonization sites requires QS, a bacterial communication system that depends on inter-bacterial cooperations. Conversely, the integrity of QS itself depends on rigorous surveillance through bottlenecked reproduction.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Michael Lynch for his critical reading of an earlier version of the manuscript. We thank members of Qu lab for stimulating discussions. UM was inspired by research findings made through a project supported in part by an NSF grant (#1758912).

References

- Aggarwal, S.D.; Lees, J.A.; Jacobs, N.T.; Bee, G.C.W.; Abruzzo, A.R.; Weiser, J.N. BlpC-mediated selfish program leads to rapid loss of Streptococcus pneumoniae clonal diversity during infection. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 124–134.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birdsell, J.A.; Wills, C. The Evolutionary Origin and Maintenance of Sexual Recombination: A Review of Contemporary Models. In Evolutionary Biology; Macintyre, R.J., Clegg, M.T., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2003; pp. 27–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, L.R.K.; Mias, G.I. Streptococcus pneumoniae’s Virulence and Host Immunity: Aging, Diagnostics, and Prevention. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlesworth, B.; Charlesworth, D. Elements of Evolutionary Genetics; W. H. Freeman and Company: New York, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Czechowska, K.; McKeithen-Mead, S.; Al Moussawi, K.; Kazmierczak, B.I. Cheating by type 3 secretion system-negative Pseudomonas aeruginosa during pulmonary infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, 7801–7806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Marshall, N.C.; Rowland, J.L.; McCoy, J.M.; Worrall, L.J.; Santos, A.S.; Strynadka, N.C.J.; Finlay, B.B. Assembly, structure, function and regulation of type III secretion systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, H.-C.; Wingender, J.; Szewzyk, U.; Steinberg, P.; Rice, S.A.; Kjelleberg, S. Biofilms: an emergent form of bacterial life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán, J.E.; Bliska, J.B. CROSS-TALK BETWEEN BACTERIAL PATHOGENS AND THEIR HOST CELLS. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1996. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartl, D.L.; Clark, G.C. Principles of population genetics, 2nd ed.; Sinauer Associates, Inc.: Sunderland, MA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, J.D.; Payseur, B.A.; Stephan, W.; Aquadro, C.F.; Lynch, M.; Charlesworth, D.; Charlesworth, B. The importance of the Neutral Theory in 1968 and 50 years on: A response to Kern and Hahn 2018. Evolution 2019, 73, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M. The neutral theory of molecular evolution; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Klausen, M.; Aaes-Jørgensen, A.; Molin, S.; Tolker-Nielsen, T. Involvement of bacterial migration in the development of complex multicellular structures in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 50, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E.V. The Origin at 150: is a new evolutionary synthesis in sight? Trends Genet. 2009, 25, 473–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewontin, R.C. The genetic basis of evolutionary change; Columbia University Press: New York, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Cheng, J. Quorum Sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Its Relationship to Biofilm Development, in: Introduction to Biofilm Engineering, ACS Symposium Series. American Chemical Society 2019, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Conover, M.; Lu, H.; Parsek, M.R.; Bayles, K.; Wozniak, D.J. Assembly and Development of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilm Matrix. PLOS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, S.; Bassler, B.L. Bacterial quorum sensing in complex and dynamically changing environments. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, G.B. Why an extended evolutionary synthesis is necessary. Interface Focus 2017, 7, 20170015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perdoncini Carvalho, C.; Ren, R.; Han, J.; Qu, F. Natural Selection, Intracellular Bottlenecks of Virus Populations, and Viral Superinfection Exclusion. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Puhar, A.; Sansonetti, P.J. Type III secretion system. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, R784–R791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, F.; Khemsom, K.; Perdoncini Carvalho, C.; Han, J. Quasispecies are constantly selected through virus-encoded intracellular reproductive population bottlenecking. J. Virol. 2024, 98, e00020–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, F.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, S.; Sun, R.; Slot, J.; Miyashita, S. Bottleneck, Isolate, Amplify, Select (BIAS) as a mechanistic framework for intracellular population dynamics of positive-sense RNA viruses. Virus Evol. 2020, 6, veaa086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundell, E.A.; McKeithen-Mead, S.A.; Kazmierczak, B.I. Rampant Cheating by Pathogens? PLOS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoodley, P.; Sauer, K.; Davies, D.G.; Costerton, J.W. Biofilms as Complex Differentiated Communities. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2002. [CrossRef]

- van Gestel, J.; Vlamakis, H.; Kolter, R. Division of Labor in Biofilms: the Ecology of Cell Differentiation. Microbiol. Spectr. 2015, 3, 10.1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volland, J.-M.; Gonzalez-Rizzo, S.; Gros, O.; Tyml, T.; Ivanova, N.; Schulz, F.; Goudeau, D.; Elisabeth, N.H.; Nath, N.; Udwary, D.; Malmstrom, R.R.; Guidi-Rontani, C.; Bolte-Kluge, S.; Davies, K.M.; Jean, M.R.; Mansot, J.-L.; Mouncey, N.J.; Angert, E.R.; Woyke, T.; Date, S.V. A centimeter-long bacterium with DNA contained in metabolically active, membrane-bound organelles. Science 2022, 376, 1453–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).