1. Summary

Orthographic processing in skilled adulthood is now understood as a rapid, knowledge-driven operation in which precisely specified letter-string representations give readers almost immediate access to meaning [

1]. Within the first few hundreds of milliseconds of viewing a word, adults recruit left-occipitotemporal networks that encode orthographic form independently of articulation, yet they can still fall back on phonological recoding when print-to-sound mappings are unreliable [

2]. The efficiency of this system hinges on how tightly orthographic, phonological, morphological and semantic codes are bonded [

3].

Undoubtedly, orthographic knowledge is a core component of the multi-layered process involved in orthographic processing. In adults, it refers to the stored mental representations of whole words, word parts (e.g., affixes), and sublexical elements [

4]. Crucially, orthographic knowledge contributes to overall lexical quality, with more robust representations enabling more efficient lexical access [

3]. Notably, orthographic knowledge is not static; it is a dynamic system that supports the ongoing acquisition and refinement of lexical representations throughout the lifespan [

5]. Experimental evidence confirms that adults continue to fine-tune their orthographic representations over time, especially for low-frequency or morphologically complex items [

6].

This dynamic and evolving nature of orthographic knowledge becomes particularly relevant when considering languages like Spanish. Although Spanish exhibits high phonological transparency for reading, its orthographic system retains etymological complexities that demand more than simple phoneme-to-grapheme mappings. Certain graphemic domains remain persistent sources of difficulty, such as the phoneme /b/, which can be represented by either the letter B or V (e.g., the homophones

vaca [cow] and

baca [luggage rack]), or the phoneme /y/, which is mapped onto both the letter Y and the digraph LL (e.g.,

malla [mesh] and

maya [Mayan]). Consequently, despite the relative consistency of Spanish orthography, adult writers must often rely on lexical knowledge to resolve ambiguities in spelling. Pseudohomophones—nonwords that are phonologically identical to real words (e.g.,

absolber, which preserves the pronunciation of

absolver [to absolve])—have been widely employed to investigate this interplay between phonological and orthographic information during visual word recognition. Research conducted in Spanish consistently shows that such pseudohomophones pose a challenge for lexical decision, highlighting the cognitive effort involved in rejecting plausible-sounding nonwords [

7].

Evidence from laboratory studies, classroom corpora, and neurocognitive research consistently points to elevated error rates in these orthographic contrasts [

8,

9]. Eye-tracking data have revealed increased competition between phonologically similar representations during reading and writing tasks [

10], while electrophysiological studies indicate that late-stage verification processes draw primarily on stored lexical knowledge rather than phonological cues alone [

11]. Together, these findings emphasize that even fluent adult readers must navigate a complex network of historical orthographic irregularities during written language production. They underscore the central role of orthographic knowledge in supporting efficient spelling and accurate visual word recognition.

To quantify these challenges at scale we compiled OthoKnow-SP, a megastudy in which 27,185 Spanish adults completed an 80-item two-alternative forced-choice task (2AFC) that paired each correct word with a pronunciation-matched pseudohomophone violating a critical spelling rule. The project yielded 2.17 million observations together with age, sex, education and device metadata (see

Methods for detail). OthoKnow-SP was designed to offer the possibility to (i) generate population norms of grapheme difficulty, (ii) trace how sociodemographic variables sculpt orthographic decisions, and (iii) furnish a benchmark for computational models trained on quasi-transparent orthographies. Early validation shows that item-level speed and accuracy correlate strongly with existing word knowledge norms [

5], confirming sensitivity to established lexical variables.

Megastudies of this sort have transformed psycholinguistics by replacing small, homogeneous samples with crowdsourced datasets large enough to expose subtle interactions between reader characteristics and word properties [

12]. Over the past decade Spanish has joined English, Dutch and French as a major contributor to this movement, spawning large-scale, web-based resources [13-15]; however, none of these corpora directly targets the persistent orthographic confusability that surfaces in adult spelling, nor do they pair accuracy with high-resolution timing data in a demographically diverse sample. OthoKnow-SP extends that agenda by sampling beyond university cohorts, capturing regional, generational and technological diversity that is typically invisible in laboratory work.

The OthoKnow-SP dataset already underpins multiple lines of research. One ongoing project integrates OthoKnow-SP with existing crowdsourced lexical decision data to investigate lifespan changes in lexical quality and orthographic knowledge. A secondary objective is to extract systematic error patterns that may inform the development of more sophisticated spell-checking algorithms. In parallel, an international collaborative initiative is deploying the same experimental architecture across multiple languages, enabling the creation of comparable datasets and opening new avenues for cross-linguistic comparisons of orthographic competence and its modulation by demographic variables.

Public release of the dataset in an open repository will magnify these benefits: open access ensures full reproducibility, enables secondary analyses that may reveal novel demographic effects, and provides educators and NLP developers with fine-grained norms for error-sensitive applications. Moreover, researchers can now investigate how age, gender, educational background, and device ecology influence the micro-dynamics of spelling, questions that earlier, smaller studies could only address in broad strokes.

In sum, OthoKnow-SP offers a richly annotated, population-scaled window onto the enduring irregularities of Spanish orthography and the sociocognitive factors that govern their resolution. We anticipate that its public availability, alongside sister corpora in other languages, will stimulate theoretical advances and practical tools alike.

2. Data Description

The OrthoKnow-SP dataset comprises 2,174,800 raw observations, corresponding to 27,185 participants completing 80 forced-choice spelling trials each. Detailed information about the participants, materials, and procedures is provided in the

Methods section. The final dataset is distributed through a publicly repository (

https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29107727) and consists of three main files:

ORTHOKNOW-SP PARTICIPANT DATA.csv,

ORTHOKNOW-SP RESPONSE DATA.csv and

OrthoKnow-SP.R

The first main data file,

ORTHOKNOW-SP PARTICIPANT DATA.csv, contains participant-level sociodemographic metadata for each individual in the study. The second main data file,

ORTHOKNOW-SP RESPONSE DATA.csv, contains trial-level response data for each participant and each word pair. These files include the variables reported in

Table 1. These files are encoded in UTF-8 CSV format and are compatible with standard analysis tools such as R and Python.

The dataset is accompanied by a supporting R script, OrthoKnow-SP.R, which contains all the code used to process, clean, and structure the raw data. This script performs key preprocessing operations, including the import and formatting of the original response logs, the filtering and validation of participant-level entries, the trimming of implausible reaction times, and the computation of accuracy metrics and trial-level summaries. These procedures ensure the integrity and consistency of the final dataset provided. Full methodological details regarding these steps are outlined in the Data Treatment section of the manuscript.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

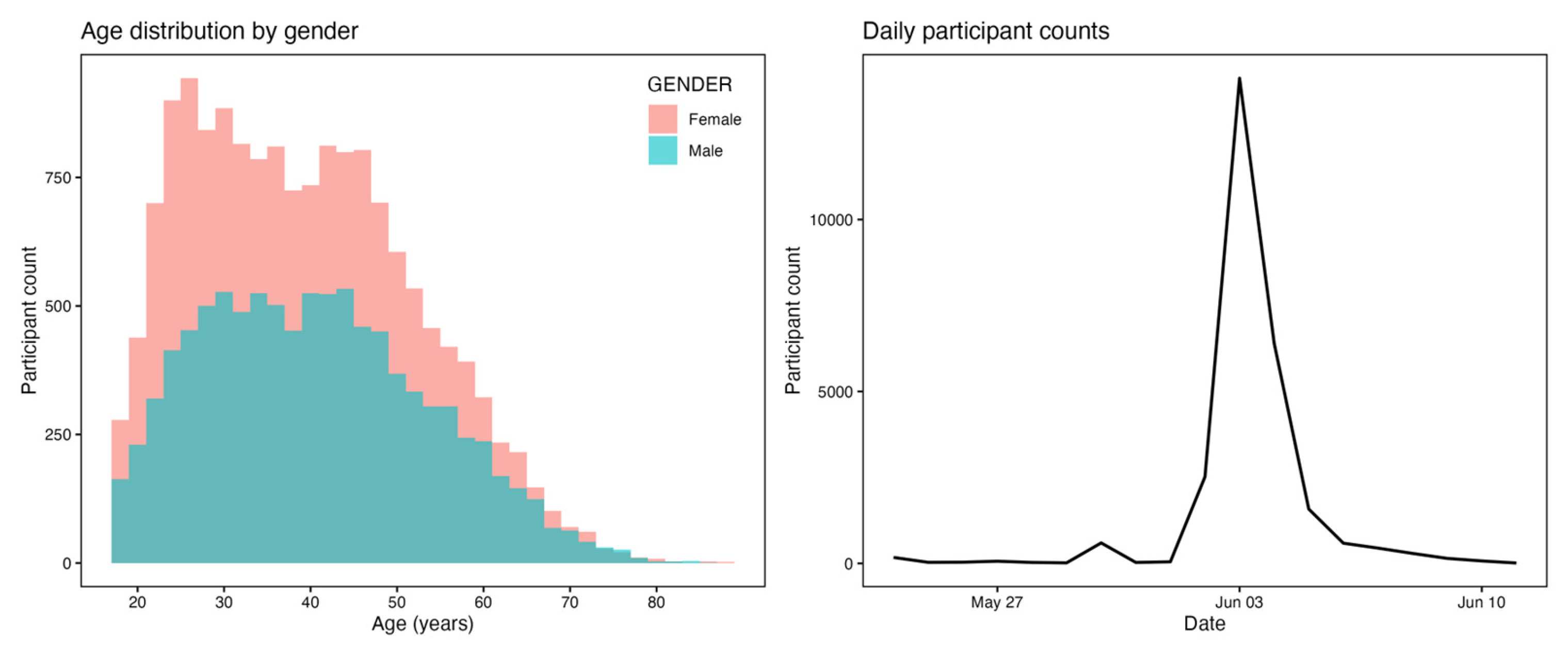

A total of 27,185 unique native speakers of Spanish, all of whom reported Spain as their country of residence and were at least 18 years of age, completed the experiment after providing informed consent through an online form that detailed the anonymisation of their data and its exclusive use for research purposes. Ethical clearance had been granted by the Ethics Board of Universidad Nebrija (approval code UNNE-2022-0017), and the study was carried out following the rules of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975, revised in 2008. The sample had a mean age of 40.40 years (SD = 13.0, range = 18–88) and comprised 62.06 % women (n = 15,609) and 37.94 % men (n = 9,544; see

Figure 1). Formal education was generally high, with 74.64 % of participants holding a university degree, while the remainder had completed secondary school, professional training, high school or primary school. Most volunteers accessed the task on a mobile phone (88.31 %, n = 23,785), and the rest used a computer (11.69 %, n = 3,148).

3.2. Materials

To operationalize orthographic difficulty, we selected eighty Spanish words that have been consistently identified by teachers, normative guides, and prior behavioral studies as frequent targets of misspelling. Each word was paired with a pseudohomophone foil that preserved the canonical pronunciation but violated a single graphemic rule. This design required participants to rely on stored orthographic knowledge rather than phonological cues alone. The manipulation was structured around six orthographic contrasts that are well-documented sources of confusion in contemporary Spanish. First, we included the historical merger of the bilabial plosives B and V, both pronounced /b/ but orthographically distinct (e.g., absolver [to absolve] vs. absolber). Second, we targeted the silent H, a letter with no phonetic realization in modern Spanish but retained in lexicalized forms (e.g., almohada [pillow] vs. almoada). Third, we manipulated the contrast between Y and LL, which can both represent the palatal approximant /y/ (e.g., boyante [buoyant] vs. bollante). Fourth, we drew on the graphemic ambiguity between C and Z, both of which can encode the /θ/ phoneme before certain vowels in Peninsular Spanish (e.g., cianuro [cyanide] vs. zianuro). Fifth, we addressed the alternation between G and J, where the voiceless velar fricative /x/ can be written with either letter depending on vowel context and other factors (e.g., exagerar [to exaggerate] vs. exajerar). Finally, we included items requiring the diaeresis <ü> in the digraph <gü>, which signals the preservation of the glide /w/ before front vowels (e.g., pingüino [penguin] vs. pinguino).

3.3. Data Collection

Data were gathered between 24 May and 11 June 2025 via a purpose-built website (

https://nebrija.com/ortografia) promoted through institutional and personal social-media channels as well as general-interest forums.

After landing on the site, visitors read a concise description of the study, the inclusion criteria, contact details for the research team and the informed-consent statement. They then completed a brief sociodemographic questionnaire (age, sex, highest level of education, country of residence and native language) before proceeding to the practice trials that illustrated the two-alternative forced-choice (2-AFC) procedure. During the test, the eighty word–foil pairs were presented in random order. The spatial arrangement of the two spellings was also randomised on every trial. Participants indicated the spelling they believed correct by touching or clicking, and each trial terminated either when a response was registered or after 5,000 ms had elapsed. A progress bar at the top of the screen provided continuous feedback on task completion.

Upon finishing, participants received personalised feedback that included their mean reaction time (RT), overall accuracy, a list of incorrectly answered items linked to their definitions in the official Spanish dictionary, and options for sharing their performance on social media or repeating the test.

All front-end interactions were implemented in JavaScript. PHP scripts handled server-side communication with a MySQL database that stored item identifiers, responses, reaction times and session metadata. The full experiment typically required no more than eight minutes.

3.4. Data Treatment

For the present dataset we retained only the first session of each participant who satisfied the inclusion criteria, yielding 2,174,800 raw observations (27,185 participants × 80 trials).

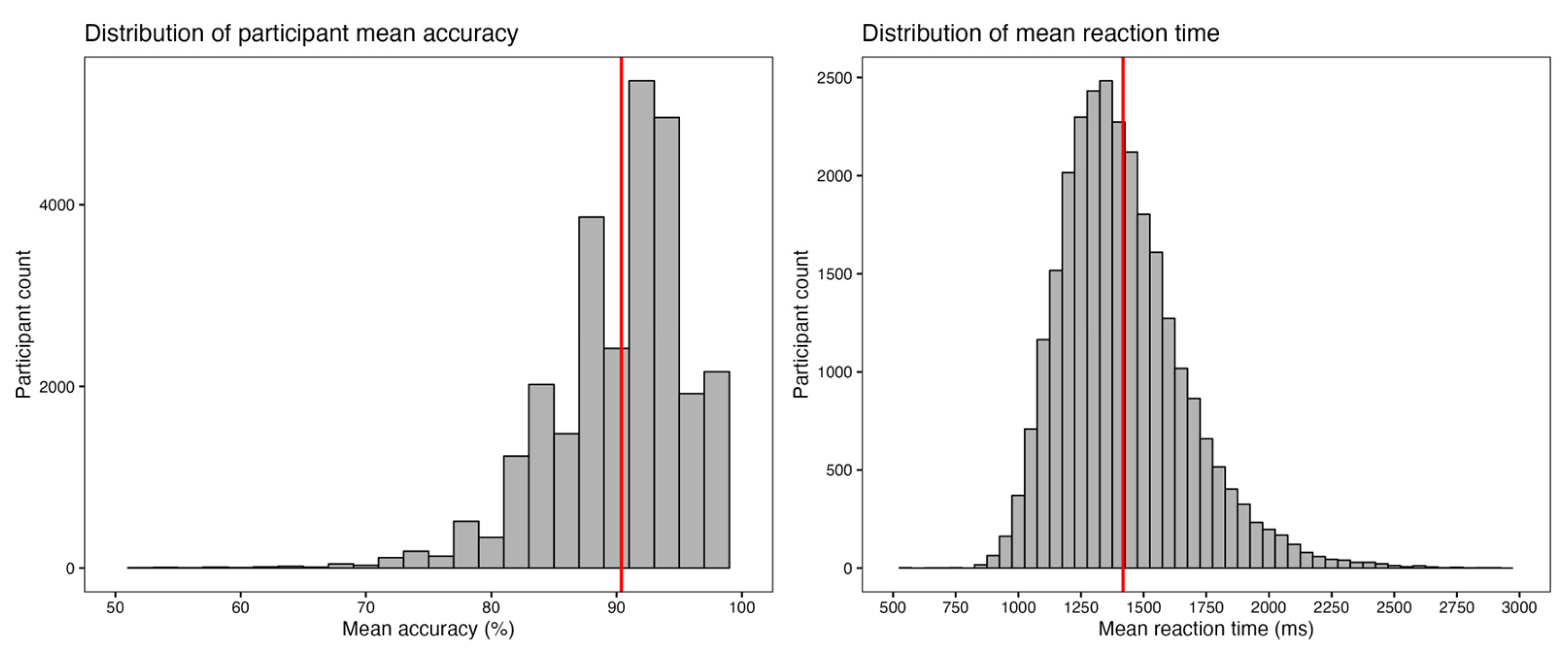

Participant-level accuracy ranged from 50 % (chance) to 100 %, with a mean of 90.4 % (SD = 5.61 %; see

Figure 2, left panel). Reaction-time (RT) analyses excluded all timeouts (RT = 5,000 ms; 4,681 trials) and all incorrect responses. For each participant, the remaining RTs were trimmed at the conventional threshold of the individual mean plus three standard deviations, eliminating a further 41,342 outliers. The cleaned RT matrix comprised 1,923,973 observations (M = 1,418 ms, SD = 252 ms, Median = 1,382 ms, range = 156–3,966 ms; see

Figure 2, right panel), providing a robust basis for subsequent item-level estimates.

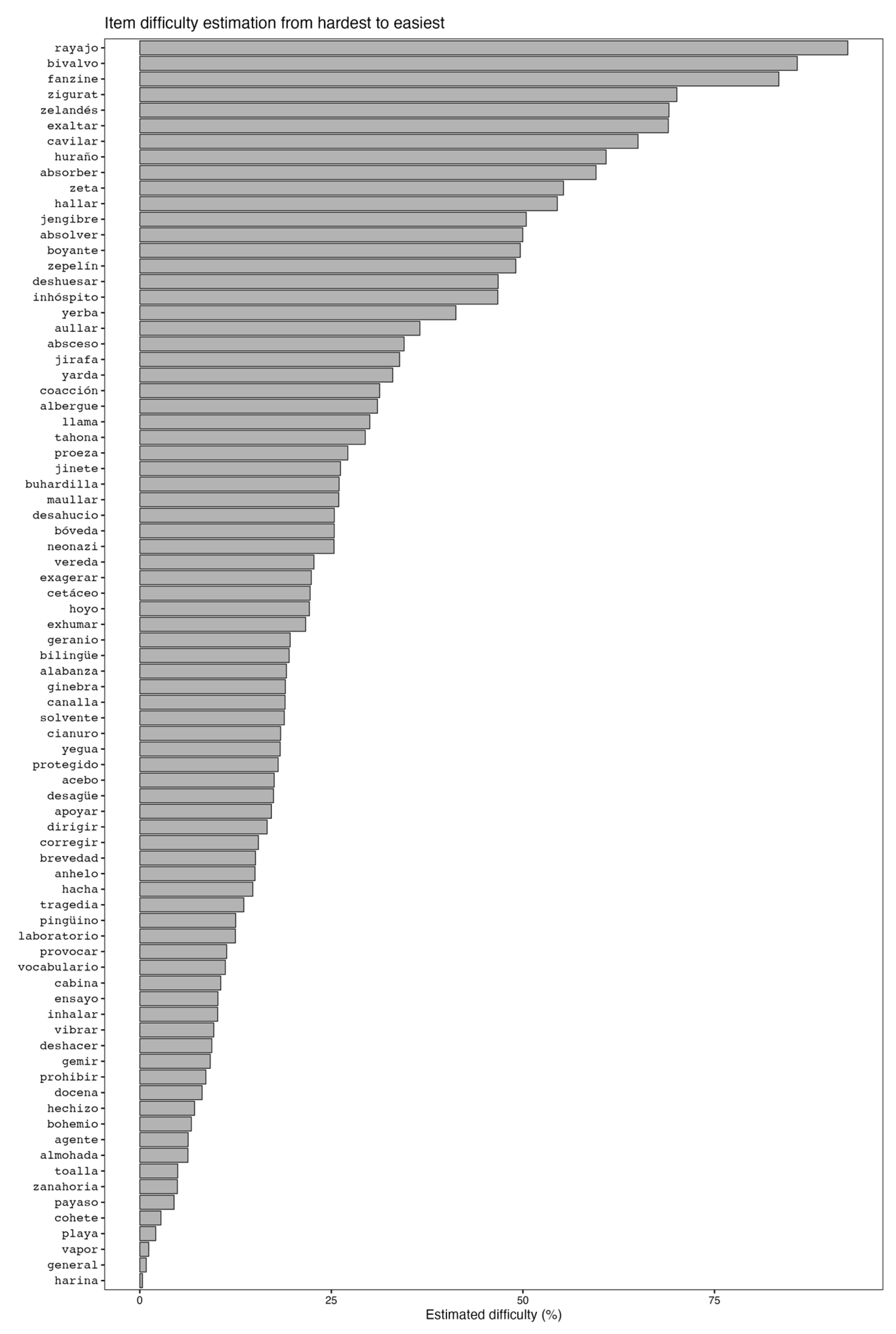

To integrate speed and accuracy into a single descriptive metric, we computed an item-wise difficulty index. Mean RTs were first rescaled to the 0–1 interval, where 0 denotes the fastest and 1 the slowest item; mean accuracies were converted into error proportions, likewise rescaled so that 0 marks flawless performance and 1 the poorest. The two standardised values were averaged and multiplied by 100, producing a percentage score that assigns equal weight to slowness and inaccuracy. This composite facilitates intuitive item ranking while avoiding ceiling effects that would arise from relying on accuracy alone (see

Figure 3 for a ranked list of the items based on their estimated difficulty).