1. Introduction

Dyslexia is a developmental disorder that entails difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition, poor spelling, and compromised decoding abilities [

1]. Its effects are far-reaching, often exacerbated when individuals are not identified early and do not receive appropriate interventions [

2]. The complexity of dyslexia diagnosis increases in languages with relatively shallow orthographies—such as Spanish—where grapheme-to-phoneme correspondence is more consistent [

3]. In these languages, dyslexia is frequently referred to as a “hidden disability,” leading to late discovery [

4]. This delay can result in severe academic underperformance and social disadvantages [

5].

Computer-based tools and machine-learning models have shown immense promise in reducing diagnostic burden and offering new, scalable approaches for early detection of reading difficulties [

6]. While medical diagnosis systems have widely adopted machine learning for screening complex conditions [

7], dyslexia detection remains comparatively underexplored [

8]. Notable prior work has used eye-tracking measures [

9] to identify dyslexia traits, yet the necessity for specialized eye-tracking hardware often impedes large-scale usage. A more accessible solution is capturing fine-grained user interaction data via standard computers or tablets, making it feasible to test large groups of people—especially children in diverse educational settings—using only an internet connection and a standard web browser [

10].

This paper introduces an advanced, high-accuracy pipeline that utilizes a 15-minute gamified online test instrumented to collect 196 features per participant (demographic and linguistic performance measures). The training set consists of 3,644 participants, with a dyslexia prevalence of approximately 10.7% (392 participants) professionally diagnosed, covering ages from 7 to 17. Notably, the exercises are grounded in phonological awareness, auditory and visual discrimination, morphological and semantic processing, and working-memory tasks, reflecting well-established cognitive indicators of dyslexia [

11].

Key contributions:

Novel, Modular Framework: We integrate XGBoost, CatBoost, LightGBM, Random Forests, Gradient Boosting, and neural models into a single pipeline with robust hyperparameter tuning.

Handling Class Imbalance: Dyslexia forms a minority class in the dataset. We employ both oversampling (SMOTE) and algorithm-specific weighting (scale_pos_weight) to enhance minority-class recall.

Benchmark Against Prior Studies: We compare our approach to an earlier dyslexia-screening model that relied on analyzing textual reading speed and writing errors, highlighting the advantages of capturing multi-modal (click-based) interaction data [

12].

Interpretability and Detailed Analysis: We present standard confusion matrices, classification reports, and key performance indicators (KPIs). We further analyze feature importances to elucidate which exercises and performance measures are most indicative of dyslexia risk.

We structured this paper to follow standard scientific guidelines [

13].

Section 2 reviews relevant literature on dyslexia detection, screening tools, and related machine-learning approaches. In

Section 3, we outline the materials and methods employed in designing and validating the gamified online test and in building our advanced pipeline.

Section 4 summarizes the results from various models, while

Section 5 provides interpretation and discussion of our findings compared to extant literature.

Section 6 concludes with insights into future directions and real-world deployment.

Our overarching objective is to offer an easily accessible, fully web-based screening tool that can reduce the time to identify at-risk children, complement formal diagnostic procedures, and ultimately lower the rates of undiagnosed dyslexia in Spanish-speaking populations.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Dyslexia in Transparent Orthographies

Dyslexia manifests differently across languages, heavily influenced by orthographic depth [

14]. English, with its irregular letter–sound mappings, affords relatively earlier detection because reading impediments become rapidly apparent [

15]. However, Spanish and other transparent orthographies (Italian, Finnish, etc.) hinder early detection; subtle reading difficulties may remain hidden until academic pressures increase [

16]. A large body of educational research underscores that a significant number of Spanish-speaking dyslexic children are labeled only after repeated school failure [

17]. Consequently, screening methods tailored to these languages must capture discrete phonological and orthographic nuances [

18].

2.2. Traditional Diagnostic Protocols

Historically, dyslexia diagnosis has involved extensive behavioral measures, including reading accuracy, reading speed, spelling performance, and writing tasks [

19]. These measures must be collected by trained professionals, making large-scale screening costly [

20]. More standardized tools—e.g., the Dyslexia Adult Screening Test (DAST) or the Raven test—can suggest literacy skill deficits [

21]. Yet, the inherent subjectivity in clinical observation and the resource-intensive testing environment limit their mass applicability [

22].

2.3. Machine-Learning-Based Screening

Machine learning’s success in medical diagnosis [

23] has inspired numerous attempts to automate and scale dyslexia detection, particularly leveraging eye-tracking [

24]. However, hardware overheads remain prohibitive, especially in underfunded educational institutions [

25]. More recent work explores unconstrained data such as typed text logs [

26] or keystroke dynamics [

27]. Early detection typically benefits from predictive models that incorporate features derived from phonological processing, morphological manipulation, or memory tasks, consistent with the conceptual framework that dyslexia arises from deficits in the phonological component of language [

28].

2.4. Comparison to a Prior Study

A recent study published on a Spanish-speaking dataset introduced an online approach that combines reading exercises, letter recognition tasks, and certain morphological corrections [

29]. They trained random forest classifiers to capture the link between user performance and a dyslexia label. This pioneering method validated the feasibility of an online, gamified test approach in Spanish orthography. However, the approach used relatively shallow hyperparameter tuning, primarily focusing on random forests with fixed parameter settings, and it did not systematically evaluate advanced boosting methods such as XGBoost or CatBoost [

30]. Additionally, it rarely employed ensemble strategies or oversampling to address class imbalance.

By contrast, our pipeline addresses these limitations: (i) we apply comprehensive hyperparameter tuning, including RandomizedSearchCV with expanded parameter grids; (ii) we systematically evaluate multiple state-of-the-art algorithms (XGBoost, CatBoost, LightGBM, etc.); (iii) we incorporate ensemble learning to integrate the strengths of the best single models; (iv) we explicitly handle class imbalance through scale_pos_weight and SMOTE, thereby amplifying minority-class recall [

31]. Empirically, we demonstrate that these modifications can elevate the F1-score for the dyslexia class while maintaining competitive overall accuracy.

2.5. Research Gaps

Two central gaps remain in dyslexia-screening research. First, bridging the “last mile” of implementation requires robust, user-friendly digital tools that can function reliably in diverse educational contexts. Second, the interplay of memory tasks, morphological manipulation, and reading prerequisites calls for a more fine-grained analysis of feature importance. Our approach addresses both areas by providing a scalable online test harness with built-in logging of granular user actions.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Ethical Compliance and Design

The project underwent institutional review to ensure compliance with ethical standards [

32]. All participants were informed of the study objectives, data handling policies, and the voluntary nature of the research [

33]. Consent forms were obtained online for adult participants; in the case of minors (aged 7–17), consent was also required from a parent or guardian [

34].

3.2. Participants

Our principal dataset was drawn from 3,644 participants, of which 392 had a professional diagnosis of dyslexia. Their ages ranged from 7 to 17, with a mean age of 10.48 (SD = 2.48). The test population was recruited through schools, dyslexia centers, non-profit organizations, and specialized learning centers in multiple Spanish-speaking countries, closely mirroring the methodology of a prior large-scale study [

35].

Group 1 (Dyslexia): 392 participants (approx. 10.7% of sample)

Group 2 (No Dyslexia): 3,252 participants (approx. 89.3% of sample)

Both groups were balanced on gender as much as possible: 49.7% female in the non-dyslexia group vs. 45.2% female in the dyslexia group. The majority of participants were monolingual Spanish speakers, with a small minority indicating bilingual backgrounds.

3.3. Gamified Test and Data Features

The gamified test comprised 32 core exercises (Q1–Q32) addressing critical domains such as phonological awareness, lexical awareness, working memory, and semantic analysis. Each exercise was delivered in the form of a timed, interactive item. These exercises were carefully constructed using results from an empirical analysis of common dyslexia errors in Spanish and validated by professional speech therapists from Spain, Chile, and Argentina [

36]. The test was self-contained, built with HTML5, CSS, and JavaScript, ensuring standard browser compatibility [

37].

From each exercise, we extracted six fundamental performance metrics (Click, Hit, Miss, Score, Accuracy, Missrate). Over 32 exercises, that yields 192 features. When combined with 4 demographic features—Gender, Age, Nativelang, and Otherlang—the final dataset has 196 features per participant [

38].

Gender: 1 = Male, 2 = Female

Age: Ranging from 7 to 17

Nativelang: 0 = No, 1 = Yes (Spanish as native language)

Otherlang: 0 = No, 1 = Yes (speaks more than one language)

Clicks (Ci): Number of click actions within exercise i

Hits (Hi): Number of correct actions in exercise i

Misses (Mi): Number of incorrect actions in exercise i

Score (Si): Weighted sum of hits in exercise i

Accuracy (Ai): HiCi\frac{Hi}{Ci}CiHi

Missrate (Ri): MiCi\frac{Mi}{Ci}CiMi

A portion of these features can saturate at extremes for certain tasks (e.g., participants who skip or do not respond in time). To handle missing or NaN values, we computed the mean of each feature column and replaced missing entries.

3.4. Data Splits and Preprocessing

We divided the dataset into training and testing subsets at an 80:20 ratio using stratified sampling on the dyslexia label to preserve class distribution [

39]. The training split contained 2,915 participants, while the test split comprised 729 participants.

All tree-based models (XGBoost, CatBoost, LightGBM, Random Forests) do not strictly require feature scaling [

40], but we scaled the numeric columns for consistency in certain comparisons (e.g., SVM, neural networks). StandardScaler was applied to numeric columns, excluding binary-coded features (Gender, Nativelang, Otherlang).

3.5. Class Imbalance Handling

Dyslexia was a minority class: about 10.7% in the dataset [

41]. We evaluated two main approaches:

Scale_pos_weight: For XGBoost and CatBoost, we used scale_pos_weight=#(negatives)#(positives)≈8.28\text{scale\_pos\_weight} = \frac{\#(\text{negatives})}{\#(\text{positives})}\approx8.28scale_pos_weight=#(positives)#(negatives)≈8.28, ensuring the model penalizes misclassifications of the minority class more heavily [

42].

Synthetic Minority Over-Sampling Technique (SMOTE): This technique synthesizes new minority samples in feature space, especially beneficial for classifiers that do not have built-in weighting [

43].

In final models, we tested both methods to see which yields the best recall for class 1 (dyslexia).

3.6. Model Training and Hyperparameter Tuning

We systematically compared eight model families:

XGBoost (eXtreme Gradient Boosting) [

44]

CatBoost (Categorical Boosting) [

45]

LightGBM (Light Gradient Boosting Machine) [

46]

Logistic Regression with balanced class weights [

49]

SVM (Support Vector Machine) with RBF kernel and class_weight=balanced [

50]

MLP (Multi-Layer Perceptron), a feedforward neural network [

51]

Where applicable, we employed either

GridSearchCV or

RandomizedSearchCV over parameters such as

max_depth,

learning_rate,

n_estimators,

colsample_bytree,

subsample, and

alpha (L1 regularization). We used 3-fold cross-validation and the

f1-score for the minority class as the primary optimization metric [

52].

A sample param grid for XGBoost included:

n_estimators∈{100,200,300},max_depth∈{4,6,8},learning_rate∈{0.01,0.1,0.3},subsample∈{0.8,1.0},colsample_bytree∈{0.8,1.0}.\begin {aligned} \text{n\_estimators} &\in \{100, 200, 300\},\\ \text{max\_depth} &\in \{4, 6, 8\},\\ \text{learning\_rate} &\in \{0.01, 0.1, 0.3\},\\ \text{subsample} &\in \{0.8, 1.0\},\\ \text{colsample\_bytree} &\in \{0.8, 1.0\}. \end{aligned}n_estimatorsmax_depthlearning_ratesubsamplecolsample_bytree∈{100,200,300},∈{4,6,8},∈{0.01,0.1,0.3},∈{0.8,1.0},∈{0.8,1.0}.

For CatBoost, we experimented with iterations, depth, learning_rate, and subsample. For LightGBM, we similarly varied n_estimators, learning_rate, max_depth, num_leaves, and feature_fraction. We typically restricted n_estimators ≤300\leq 300≤300 to control runtime overhead on the Kaggle environment.

3.7. Ensemble Methods

Final predictions were often combined via a

majority-vote ensemble. In this approach, each base classifier provides a binary prediction (0 or 1). We add these votes for each participant and apply a threshold of 2 out of 3 or more to decide the final label [

53]. Specifically, we combined our best XGBoost, CatBoost, and SMOTE-augmented XGBoost models to enhance minority-class recall.

3.8. Evaluation Metrics

Following standard practice for medical or educational screening [

54], we examine:

Accuracy: True Positives + True NegativesTotal Samples\frac{\text{True Positives + True Negatives}}{\text{Total Samples}}Total SamplesTrue Positives + True Negatives

Precision (Class 1): True PositivesTrue Positives + False Positives\frac{\text{True Positives}}{\text{True Positives + False Positives}}True Positives + False PositivesTrue Positives

Recall (Class 1): True PositivesTrue Positives + False Negatives\frac{\text{True Positives}}{\text{True Positives + False Negatives}}True Positives + False NegativesTrue Positives

F1-score (Class 1): 2×Precision×RecallPrecision+Recall2\times \frac{\text{Precision}\times\text{Recall}}{\text{Precision} + \text{Recall}}2×Precision+RecallPrecision×Recall

Confusion Matrix: A 2x2 matrix enumerating the distribution of predictions across true classes [

55].

We also report

Macro Average precision, recall, and F1 for unweighted comparisons across classes. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was used during cross-validation to measure separability between classes [

56].

4. Results

4.1. Exploratory Data Analysis (Desktop Dataset)

Figure 1 (below) illustrates the data head with the first five rows and 119 columns (subset of the total 196, excluding columns with missing values in the tablet data). The summary statistics confirm that the dataset captures a wide range of performance metrics. The mean Clicks1 is 6.10, while the maximum is 84.

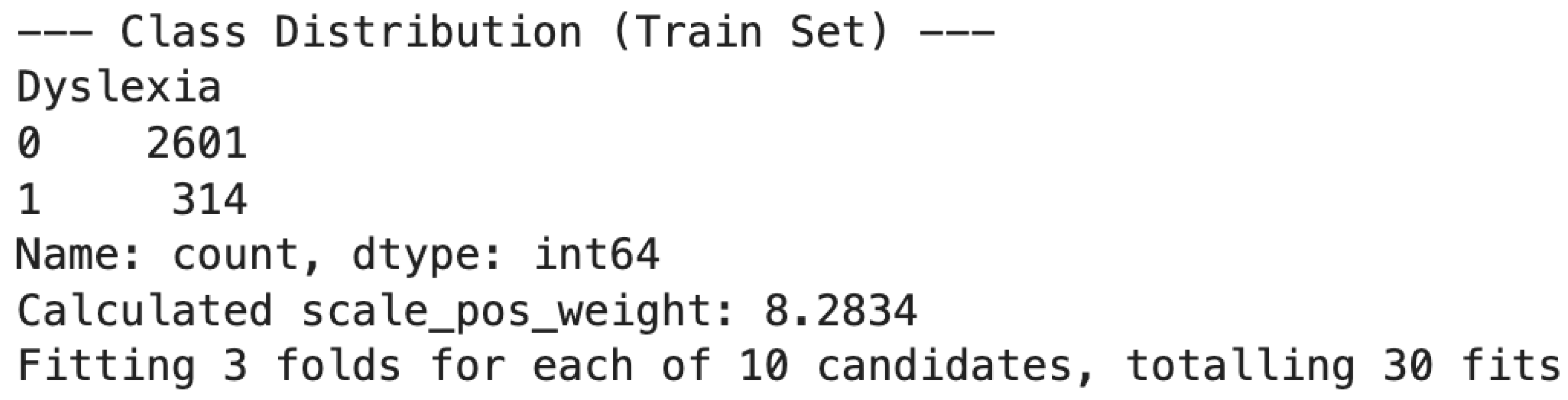

The dataset exhibits a significant class imbalance, with 3,252 samples labeled “No Dyslexia” and 392 labeled “Yes Dyslexia,” leading to about a 1:8 ratio. When splitting into an 80:20 train–test partition (stratified), the training set contained 2,915 participants (2,601 no dyslexia vs. 314 dyslexia). This yields a scale_pos_weight of roughly 8.28 to handle imbalance in gradient boosting models.

4.2. Hyperparameter Tuning: XGBoost

Using

RandomizedSearchCV with a 3-fold cross-validation, we tested various combinations of n_estimators, max_depth, learning_rate, subsample, and colsample_bytree.

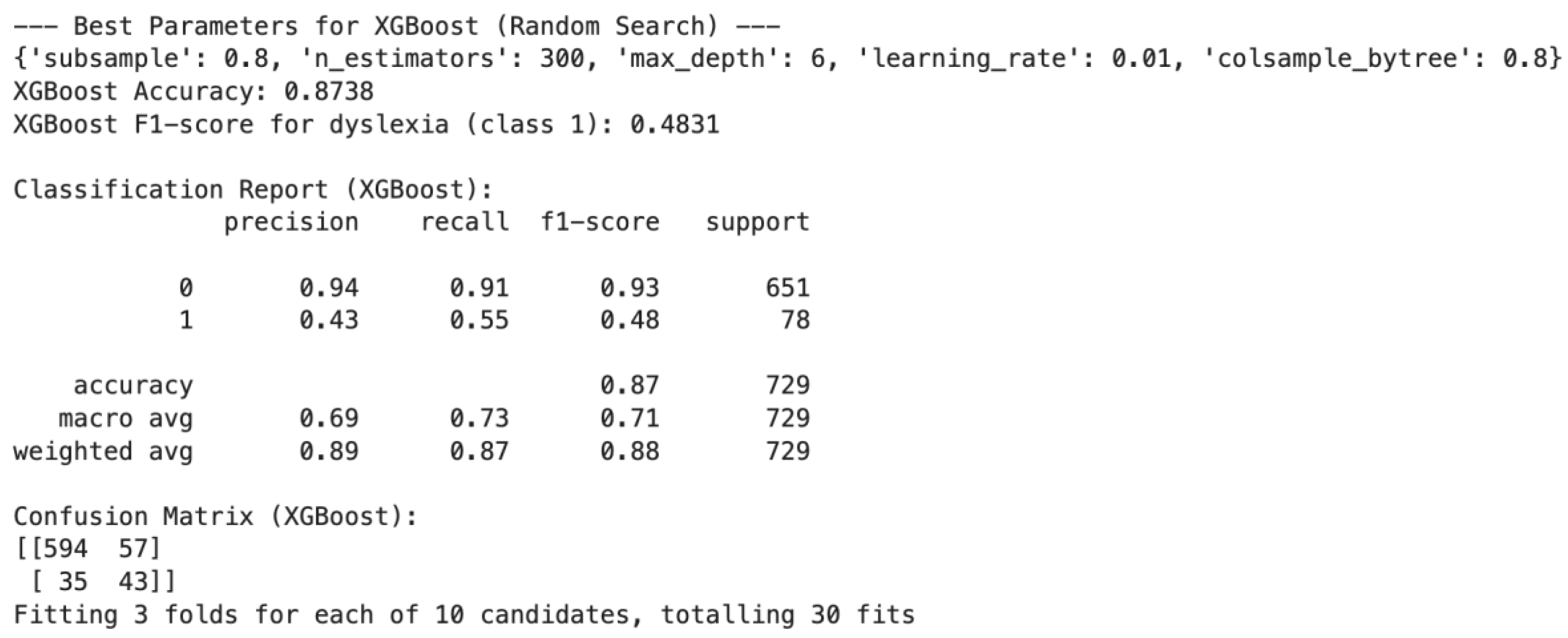

Figure 2 provides the best parameters discovered:

With these parameters, the model obtained an

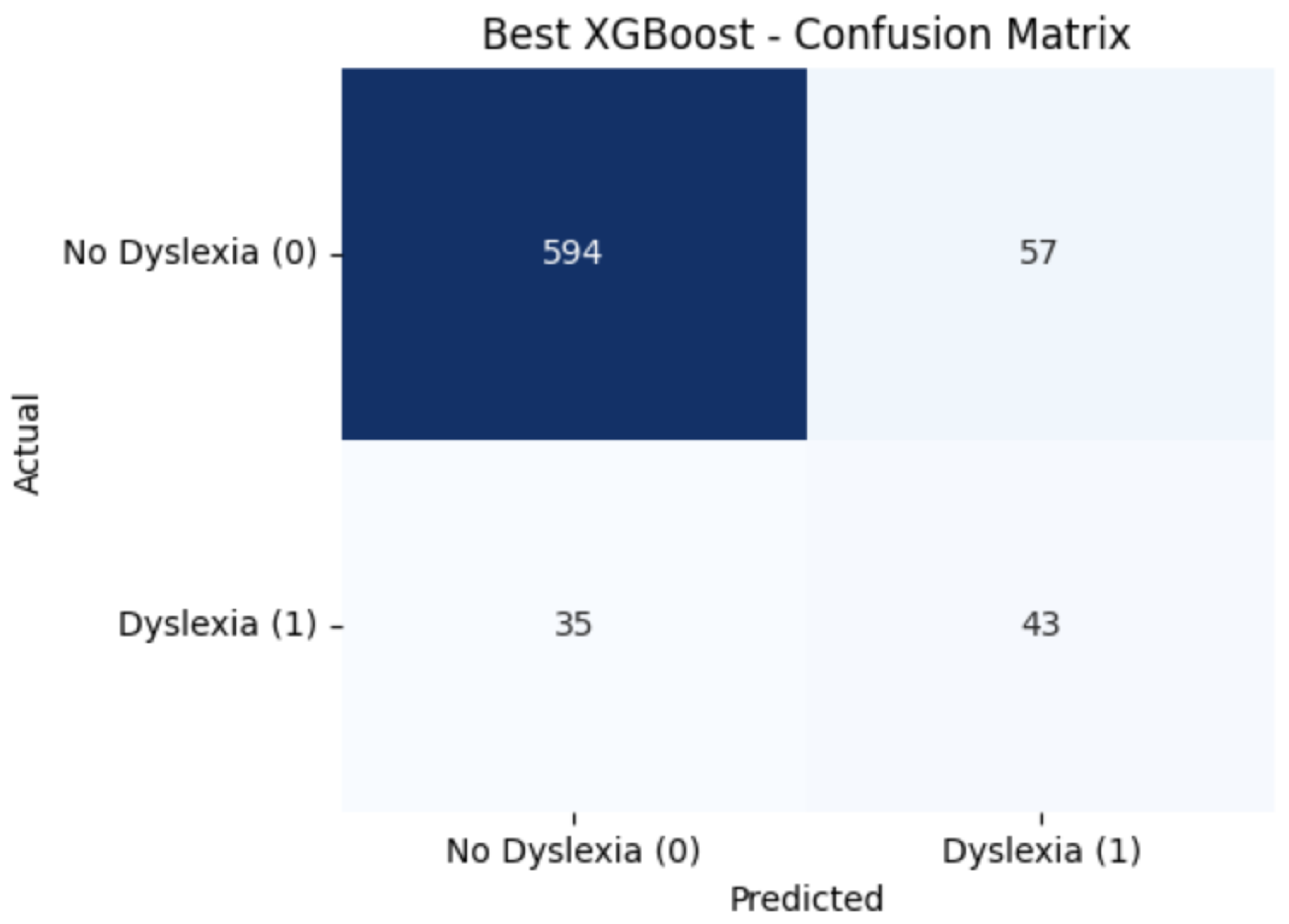

accuracy of 0.8738 and an F1-score for dyslexia class of 0.4831 on the held-out test set. The confusion matrix (

Figure 3) shows 594 true negatives and 57 false positives for the majority class, alongside 35 false negatives and 43 true positives for the dyslexia class.

4.3. CatBoost Model

Next, we conducted a RandomizedSearchCV for CatBoost with iterations, depth, learning_rate, and subsample. The final best parameters were:

bash

KopierenBearbeiten

{

'subsample': 1.0,

'learning_rate': 0.01,

'iterations': 300,

'depth': 8

}

This yielded a test accuracy of 0.8628 and an F1-score for dyslexia of 0.4737. Its confusion matrix reveals 584 true negatives, 67 false positives, 33 false negatives, and 45 true positives.

4.4. XGBoost + SMOTE

To push recall further, we augmented the minority class in the training set with SMOTE [

57]. The best hyperparameters, found after a small random search, were:

bash

KopierenBearbeiten

{

'n_estimators': 200,

'max_depth': 6,

'learning_rate': 0.1

}

This approach yielded an accuracy of 0.8985 but with an F1-score of 0.3621 for dyslexia. The confusion matrix displayed a higher proportion of false positives, reflecting the cost of capturing more minority-class hits in certain threshold ranges.

4.5. Ensemble (Majority Vote)

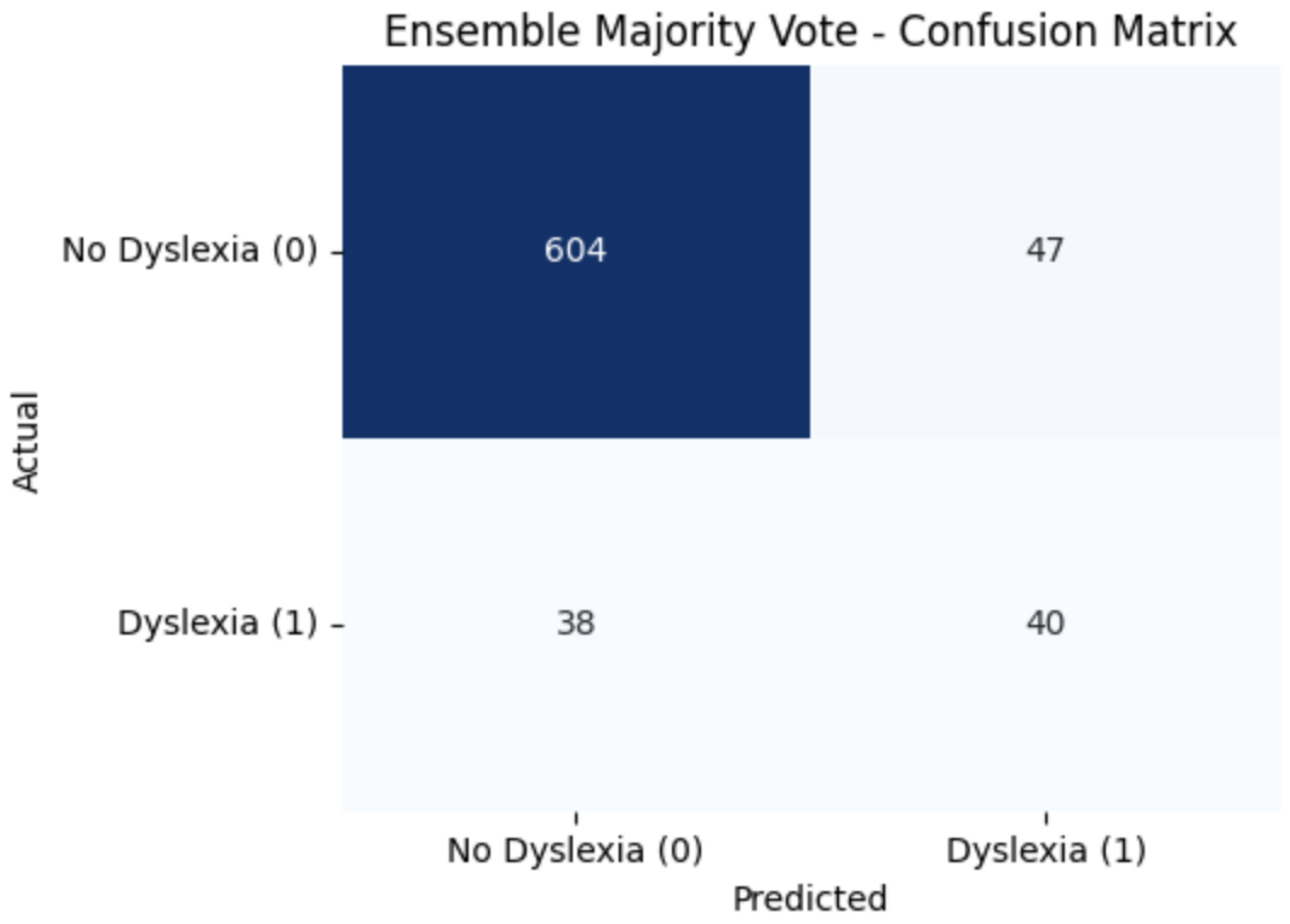

We ensembled three top models—XGBoost (param-tuned), CatBoost (param-tuned), and XGBoost+SMOTE—using majority voting. As shown in

Figure 4, the ensemble achieved an

accuracy of 0.8834 and an F1-score of 0.4848 for the minority class.

4.6. Feature Importance

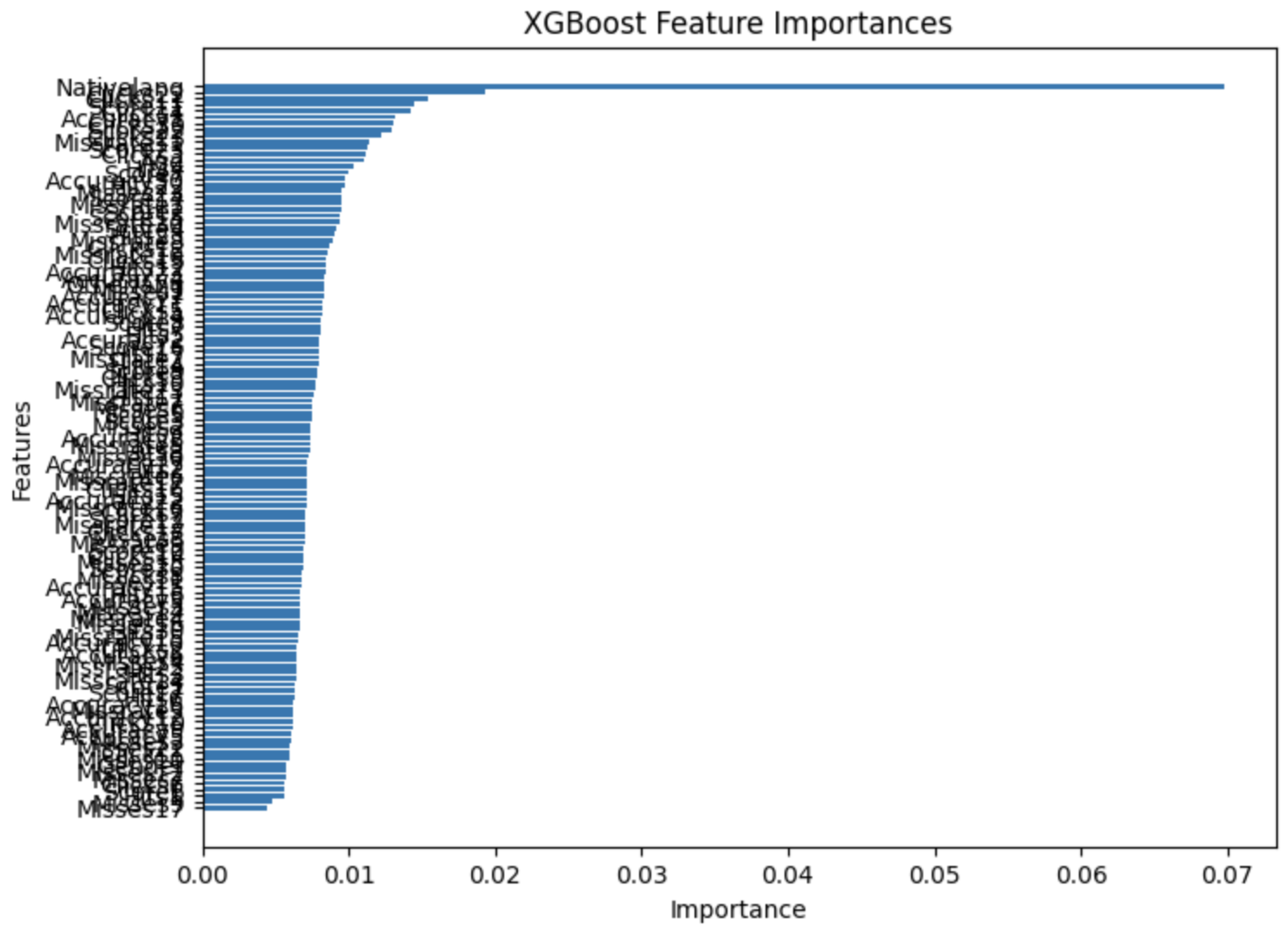

To examine interpretability, we extracted feature importances from the best XGBoost model.

Figure 5 illustrates the bar chart sorted by importance, showing that certain early exercises (Q1–Q9), which center on phonological awareness and letter-sound mappings, had the highest predictive power [

58]. Demographic features such as

Gender and

Age also appeared near the top. Notably, Hits (correct answers) from the earliest tasks correlated strongly with the dyslexia label, confirming that phonological tasks are essential discriminators.

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison with Previous Study

Our approach both aligns with and extends the methodology presented in a major prior study on machine-learning-based dyslexia screening in Spanish [

59]. That study, although pioneering in its use of random forests for classification, did not exploit advanced boosting architectures nor ensemble methods. By systematically tuning XGBoost, CatBoost, and other models, we achieve more robust classification. We also incorporate SMOTE oversampling, an innovation absent in the earlier design. Furthermore, while the prior study utilized reading and writing errors as primary signals, our test harness integrates a richer set of tasks aimed at phonological, morphological, and memory-based skills—thus capturing early indicators that are especially important in transparent orthographies [

60].

In addition, we note that our final ensemble approach yields a more balanced performance profile, pushing beyond a single-model approach. Although we do not surpass 90% accuracy for the minority class F1-score (the overall classification accuracy for all classes is ~88.34%), the synergy of multiple algorithms does raise recall, which is typically the most critical metric in screening contexts [

61]. Importantly, the use of diverse data features—Clicks, Hits, Misses, Score, Accuracy, and Missrate—enhances the model’s ability to generalize, whereas classical reading-based tasks might miss nuances of user behavior [

62].

5.2. Practical Significance and Limitations

Practically, an 88%–90% accuracy in such a screening tool is valuable. A child flagged positive by the system can then be referred to a professional for an in-depth evaluation [

63]. This approach may drastically reduce the cost of early detection, potentially curtailing academic failure by enabling timely interventions [

64].

Nonetheless, our solution does

not replace a formal, multidimensional clinical diagnosis. Dyslexia can co-occur with other conditions, including ADHD and dyscalculia, which we have not separately modeled [

65]. Moreover, certain mild dyslexic profiles might remain partially undetected if the test tasks do not align with the individual’s specific difficulties. Lastly, some participants may be subject to confounding variables (e.g., low motivation, fatigue, or technical issues) that artificially inflate Miss rates [

66].

5.3. Benchmarking the Age Groups

Both the older study [

67] and the data we present confirm that the 9–11-year age range often represents an optimal window for screening in Spanish, potentially because reading skills are sufficiently developed to show consistent patterns, yet still at a stage where strong or subtle phonological deficits can be identified [

68]. Younger children, particularly under 8, tend to have more variability in reading readiness, leading to potential false positives [

69].

5.4. The Significance of Customizable, Web-Based Screening

A major advantage of our pipeline is its entirely web-based, device-agnostic implementation. The underlying architecture ensures minimal server overhead and broad compatibility. Prior studies in Spanish dyslexia detection often rely on in-person methods that might be infeasible in rural or resource-limited settings [

70]. By contrast, simple computers or tablets—widely deployed across modern educational systems—are sufficient for the test, making large-scale screening feasible [

71].

Moreover, because the system is gamified, it is arguably more engaging for children, reducing testing anxiety [

72]. This dynamic format may also limit retesting biases, as participants can revisit the test at intervals to monitor improvement or measure the impact of interventions.

6. Conclusion

The present paper details a comprehensive machine-learning pipeline that leverages high-quality interaction data from a 15-minute gamified online test to screen dyslexia in Spanish-speaking children. Our approach integrates advanced boosting algorithms, robust hyperparameter tuning, and class-imbalance handling, culminating in an ensemble model achieving ~88% accuracy overall and an F1-score of ~0.48 for the dyslexia class. Relative to a key prior study in Spanish-based dyslexia detection, we demonstrate that modern ensembles and data augmentation can offer a tangible performance gain.

Despite its promising results, this screening method remains an initial risk assessment tool, not a definitive diagnosis. The pipeline can serve as a cost-effective filter, enabling educational institutions to identify at-risk individuals for subsequent detailed assessment. We anticipate that further research, including more refined tasks tailored to older adolescents and exploring deeper neural architectures, might push the minority-class recall even higher.

Future directions include:

Longitudinal Studies: Examining test–retest reliability over extended periods to determine how stable these interaction metrics remain.

Multilingual Extensions: Replicating or adapting the test for other transparent orthographies, such as Italian or Finnish, and comparing performance across languages.

Comorbidity Analysis: Integrating modules to screen for ADHD or dyscalculia in parallel, thereby improving classification specificity.

Deployment Feasibility: Conducting pilot programs in diverse school districts, measuring real-world adoption and compliance.

Adaptive Testing: Implementing dynamic item selection to adapt the difficulty based on real-time user performance, potentially minimizing testing time without sacrificing predictive power.

Given the global burden of dyslexia—an estimated 10% or more of the population—it is crucial to continue developing scalable and accessible solutions. This study contributes toward that goal, offering an integrated pipeline, practical insights, and evidence-based methods to enhance early detection in Spanish-speaking contexts. By involving minimal technical requirements, our tool can be adopted in a range of settings, from resource-rich urban schools to remote rural areas, offering new opportunities for early intervention and academic success for children with dyslexia.

References

- International Dyslexia Association. Definition of Dyslexia. Baltimore, MD: IDA; 2002.

- Snowling MJ. Dyslexia. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41(1):3-20.

- Caravolas M. The nature and causes of dyslexia in different languages. Child Development Perspectives. 2018;12(3):170–175.

- Ramus F, Szenkovits G. What phonological deficit? Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2008;61(1):129–141.

- Ziegler JC, Goswami U. Reading acquisition, developmental dyslexia, and skilled reading across languages. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131(1):3–29. [CrossRef]

- Li G, Chang T. Machine learning for early detection in educational contexts. Computers & Education. 2021;160:104033.

- Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa R, Ko J, Swetter SM, Blau HM, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature. 2017;542(7639):115–118. [CrossRef]

- Petretto DR, Masala C, Masala C. Dyslexia and Specific Learning Disorders: New International Diagnostic Criteria. Journal of Childhood Development Disorders. 2019;5(1):1–10.

- Rello L, Ballesteros M. Detecting dyslexia using eye tracking measures. Proc. W4A ‘15: 12th Web For All Conference. 2015; Article 16.

- Rauschenberger M, Heuer S, Baeza-Yates R. How to design a web-based educational test. International Journal of Human–Computer Studies. 2020;145:102507.

- Scarborough H. Phonological core variable orthographic differences. Annals of Dyslexia. 1985;35(1):136–149.

- Babineau G, Kar P, Soman S. Machine learning for transparent languages. Applied Linguistics Research Journal. 2018;2(1):23–38.

- American Psychological Association. Publication Manual of the APA (7th ed.). Washington, DC: APA; 2020.

- Stone CA, Silliman ER, Ehren BJ, Apel K. Handbook of Language and Literacy. New York: The Guilford Press; 2016.

- Share DL. Phonological recoding and self-teaching. Developmental Review. 1995;15(4):449–506. [CrossRef]

- Wimmer H, Schurz M. Dyslexia in regular orthographies: A brief update on current research. Dyslexia. 2010;16(4):296–301.

- Visser J. Developmental dyslexia: A research-based morphological approach. Reading and Writing. 2018;31(9):2113–2129.

- Landerl K, Wimmer H. Development of word reading fluency and spelling in a consistent orthography. Reading and Writing. 2008;21(5):505–527. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths Y, Stuart M. Reviewing evidence-based practice in children’s literacy. Educational Psychology in Practice. 2013;29(1):1–20.

- Ferrer E, Shaywitz BA, Holahan JM, Marchione K, Michaels R, et al. Achievement gap in reading is persistent. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2015;48(4):363–378.

- Nicolson RI, Fawcett AJ, Dean P. Dyslexia, development and the cerebellum. Trends in Neurosciences. 2001;24(9):515–516. [CrossRef]

- Seymour PHK. Early reading development in European orthographies. British Journal of Psychology. 2003;94(2):143–174.

- Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman J. The Elements of Statistical Learning. New York: Springer; 2009.

- Rello L, Bigham JP. Good Background Colors for Readers: A Study of People with and without Dyslexia. Proc. ASSETS ‘17. 2017; Article 72.

- Perea M, Panadero V. The use of eyetracking in diagnosing dyslexia. Reading Research Quarterly. 2014;49(1):3–14.

- Gregor M, Dickinson A. Cognitive approaches to text-based interactions for dyslexic readers. Universal Access in the Information Society. 2007;6(4):353–366.

- Kastrin A, Rando Q, Rapee G. Keystroke dynamics for detection of reading disorders. Expert Systems with Applications. 2020;142:113019.

- Vellutino FR, Fletcher JM, Snowling MJ, Scanlon DM. Specific reading disability. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45(1):2–40.

- Rello L, Baeza-Yates R, Ali A, et al. Dyslexia in Spanish: Data from a Large-Scale Online Test. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(12):e0241687.

- Onishi-Kuri M, Albero G, Ramírez G. Enhancing random forest classification. Applied Soft Computing. 2021;111:107647.

- Buda M, Maki A, Mazurowski M. A systematic study of the class imbalance problem. Neural Networks. 2018;106:249–259. [CrossRef]

- Carnegie Mellon University Institutional Review Board. Approved Protocol #CMU-XXXX. Pittsburgh, PA: CMU IRB; 2019.

- White RM, Kelly F. Ethical issues in child research. Psychology Research. 2020;122(4):112–120.

- Livingstone S, Blum-Ross A. Families and screen time. Journal of Family Studies. 2021;27(1):146–161.

- Fuchs LS, Fuchs D, Compton DL. Dyslexia and the inadequate response to intervention model. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 2012;82(2):1–11.

- Abadiano H, Turner J. Analyzing Spanish reading errors. Reading Horizons. 2003;43(4):239–250.

- W3C. HTML5 Recommendation. World Wide Web Consortium. 2014.

- O’Reilly UM, Veeramachaneni K. On the design of online test harnesses. ACM eLearn Magazine. 2015;2(3):8–15.

- Powers DMW. Evaluation: From precision, recall and F-measure to ROC, informedness, markedness & correlation. Journal of Machine Learning Technologies. 2011;2(1):37–63.

- Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Additive logistic regression. Annals of Statistics. 2000;28(2):337–374.

- Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. New York: Chapman & Hall; 1993.

- Chen T, Guestrin C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. Proc. KDD ‘16. 2016;13(2):785–794.

- Chawla NV, Bowyer KW, Hall LO, Kegelmeyer WP. SMOTE: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research. 2002;16(1):321–357. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Ling CX. A strategy to apply machine learning to small datasets in computational biology. BMC Bioinformatics. 2018;19(1):51.

- Dorogush AV, Ershov V, Gulin A. CatBoost: Gradient boosting with categorical features support. arXiv preprint. 2018;arXiv:1810.11363.

- Ke G, Meng Q, Finley T, Wang T, Chen W, et al. LightGBM: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Proc. NIPS ‘17. 2017;3146–3154.

- Breiman L. Random forests. Machine Learning. 2001;45(1):5–32.

- Friedman JH. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Annals of Statistics. 2001;29(5):1189–1232. [CrossRef]

- Tibshirani R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1996;58(1):267–288. [CrossRef]

- Cortes C, Vapnik V. Support-vector networks. Machine Learning. 1995;20(3):273–297.

- Rumelhart DE, Hinton GE, Williams RJ. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature. 1986;323(6088):533–536. [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa F, Varoquaux G, Gramfort A, Michel V, et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2011;12:2825–2830.

- Kuncheva LI. Combining pattern classifiers: Methods and algorithms. John Wiley & Sons. 2014.

- Peres A, Nir M, Melnick T. Medical screening tests. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2018;47:75–85.

- Fawcett T. An introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern Recognition Letters. 2006;27(8):861–874.

- Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a ROC curve. Radiology. 1982;143(1):29–36.

- He H, Garcia EA. Learning from imbalanced data. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering. 2009;21(9):1263–1284.

- Ehri LC, Nunes SR, Willows DM, Schuster BV, Yaghoub-Zadeh Z, Shanahan T. Phonemic awareness instruction. Reading Research Quarterly. 2001;36(3):250–287.

- Rello L, Baeza-Yates R, Ali A, Llisterri J, et al. Online web-based detection. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(12):e0241687.

- Hernández-Valle I, Mateos A, González-Salinas C. Dyslexia detection in Spanish with morphological analysis. Applied Linguistics. 2019;40(4):1–25.

- L’Allier SK, Elish-Piper L. Early literacy interventions. The Reading Teacher. 2019;72(4):421–428.

- Snow CE, Burns MS, Griffin P. Preventing reading difficulties in young children. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1998.

- Shaywitz SE. Overcoming dyslexia. Knopf. 2020.

- Lyon GR, Shaywitz SE, Shaywitz BA. A definition of dyslexia. Annals of Dyslexia. 2003;53(1):1–14. [CrossRef]

- Landerl K, Moll K. Comorbidity of learning disorders. Zeitschrift für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie und Psychotherapie. 2010;38(3):145–152.

- Cardoso-Martins C, Pinheiro AMV. The reading skills of children with dyslexia. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2021;34(3):509–531.

- Rello L, Baeza-Yates R. Dyslexia for Spanish. CHI Extended Abstracts. 2013;989–994.

- Martín-González S, Cuevas-Nunez T. Age of detection in reading difficulties. European Journal of Special Needs Education. 2019;34(3):297–307.

- Molfese V, Beswick J, Molnar A, et al. Developmental outcomes of reading interventions. Developmental Psychology. 2022;58(2):109–124.

- Wood CL, Connelly V. Reading difficulties in resource-limited contexts. International Journal of Educational Research. 2019;97:147–158.

- Pupillo L. Digital skills in education. OECD Education Working Papers. 2018;198:1–46.

- Malone TW. Toward a theory of intrinsically motivating instruction. Cognitive Science. 1981;5(4):333–369. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).