Submitted:

12 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Developmental dyslexia is one of the most common learning disorders, characterized by persistent difficulties with reading, writing, and phonological processing. While many studies have employed supervised classification models to distinguish dyslexic from control participants, the effectiveness of purely unsupervised techniques remains underexplored. This paper examines a novel, fully unsupervised clustering pipeline to separate dyslexic and control participants on the basis of multiple screening test results (cognitive, phonological, and reading-based measures). The pipeline leverages correlation-based feature selection, EllipticEnvelope outlier removal, nonlinear dimensionality reduction (UMAP), and extensive hyperparameter searches across six clustering algorithms. Applied to a dataset of 55 participants (after removing one spurious group “M” label), our approach eventually yielded two distinct clusters with an approximate purity of 92.11% when mapped back to the actual Dyslexic vs. Control labels. We interpret these findings in light of prior research on phonological deficits in dyslexia, highlighting how the emergent cluster structure suggests robust differences in phoneme awareness, reading speed, and memory spans under noise. Our approach extends prior speech-in-noise classification image (ACI) studies by focusing on large-scale, data-driven unsupervised learning, revealing distinct compensation strategies that dyslexic adults can develop. Although the final purity indicates a high alignment between clusters and clinical labels, we also emphasize the necessity of replicating these findings with broader samples and considering combined methods (e.g., semi-supervised or supervised) to confirm the stability of these results. This study adds to the growing body of evidence that advanced machine learning methods—properly optimized—can elucidate phonological deficits, test compensatory hypotheses, and potentially guide future interventions in dyslexia research.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Dyslexia and Phonological Deficit

1.2. Prior Work on Unsupervised Dyslexia Assessment

1.3. Aims and Contributions

- Feature Subset Selection: We prioritize dyslexia-relevant features such as reading speed, phoneme awareness tasks (deletion, spoonerism), memory spans, and partial audiometric or attention measures [23].

- Correlation Filtering: Remove highly correlated (>0.90) features to reduce redundancy [24].

- EllipticEnvelope Outlier Removal: Exclude participants with extreme values (e.g., outliers) that could distort cluster boundaries [25].

- Nonlinear Dimensionality Reduction (UMAP): Reveal manifold structure better than PCA alone [26].

- Hyperparameter Tuning of Six Clustering Methods: KMeans, Agglomerative, DBSCAN, Spectral Clustering, Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM), HDBSCAN [27].

- Cluster Validation: Evaluate silhouette, Davies-Bouldin, and “purity-based accuracy” by mapping cluster assignments back to the known Dyslexic vs. Control labels [28].

1.4. Paper Structure

- Section 2 describes the participants, the original data acquisition, and the steps in the unsupervised pipeline.

- Section 3 details the results of each stage, including feature selection, outlier removal, clustering metrics, and the final 92.11% cluster purity.

- Section 4 discusses the implications of these findings, parallels and distinctions compared to prior speech-in-noise research, and limitations.

- Section 5 concludes, emphasizing next steps and how unsupervised approaches might complement supervised diagnosis tools.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Ethical Considerations

2.2. Preliminary Screening Tests

- Age and Handedness (Edinburgh test) [32]

- Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices (score /60): A measure of nonverbal IQ [33].

- Reading Age (L’Alouette), Alouette Errors, Alouette Time: Standard French reading test measures [34].

- Phoneme Deletion (score /10) plus time, Spoonerism (score /20) plus time: Key phonological awareness tasks [35].

- Reading Tests: Regular words, irregular words, pseudowords (scores and times) [36].

- Spelling Tests (score/time for regular, irregular, pseudowords) [37].

- Memory Span Tests: Forward digit, backward digit [38].

- ANT (Attention Network Test): Alerting, orienting, conflict effect [39].

2.3. Data Preprocessing

2.3.1. Removing “M” and Handling NaNs

2.3.2. Feature Subset

2.3.3. Correlation Filtering

2.4. Outlier Detection and Removal

2.5. Dimensionality Reduction (UMAP)

2.6. Clustering Algorithms and Hyperparameter Search

- Silhouette Score: Measures how distinct clusters are [50].

- Davies-Bouldin Index: Evaluates average cluster similarity; lower is better [51].

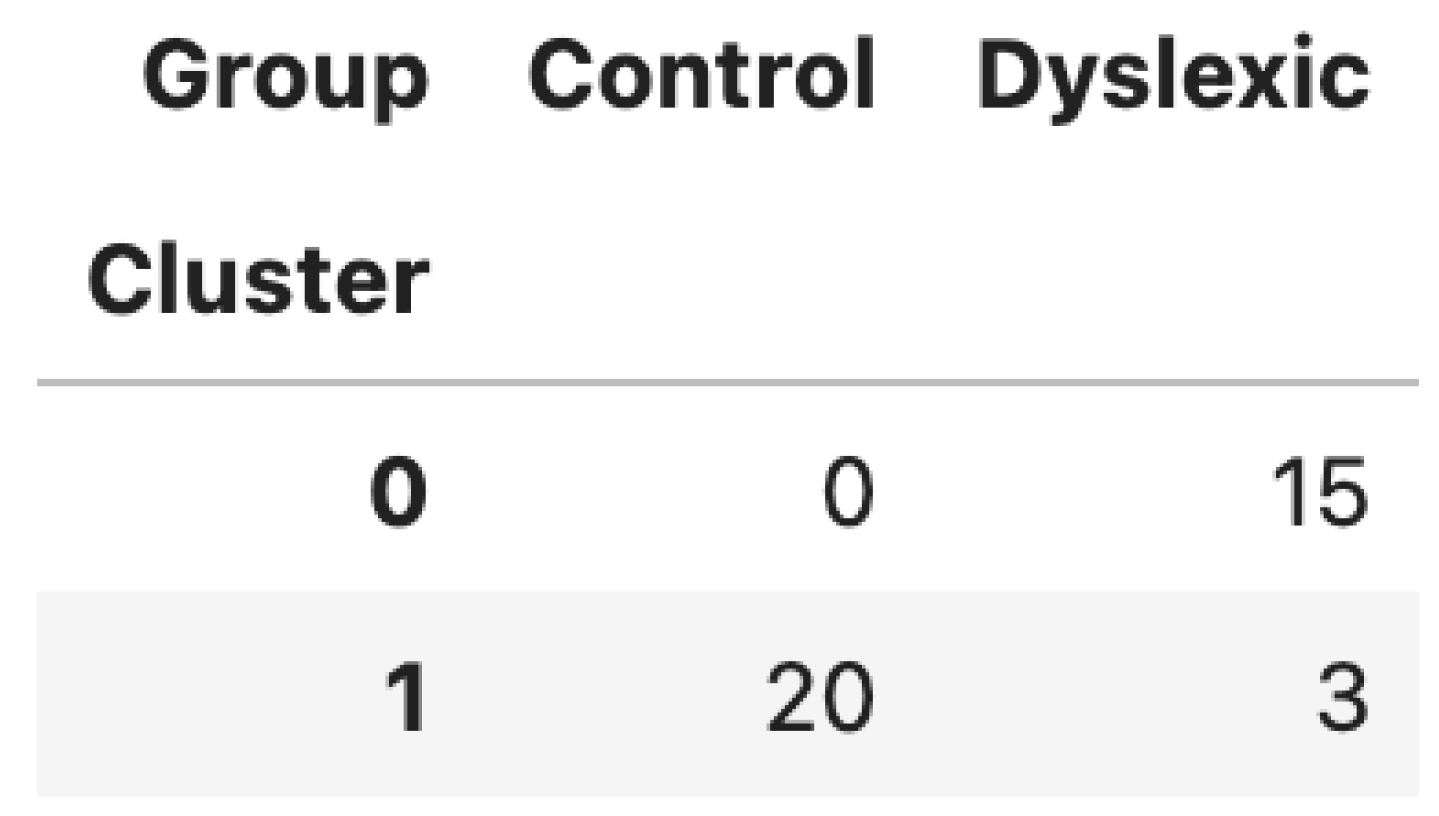

- Approximate Cluster Purity: We mapped the final labels to the participant’s “Group” (Control, Dyslexic). Specifically, each cluster was assigned the label that maximized the overlap among its members, and we computed the fraction of participants whose group label matched that cluster label [52].

2.7. Visualization

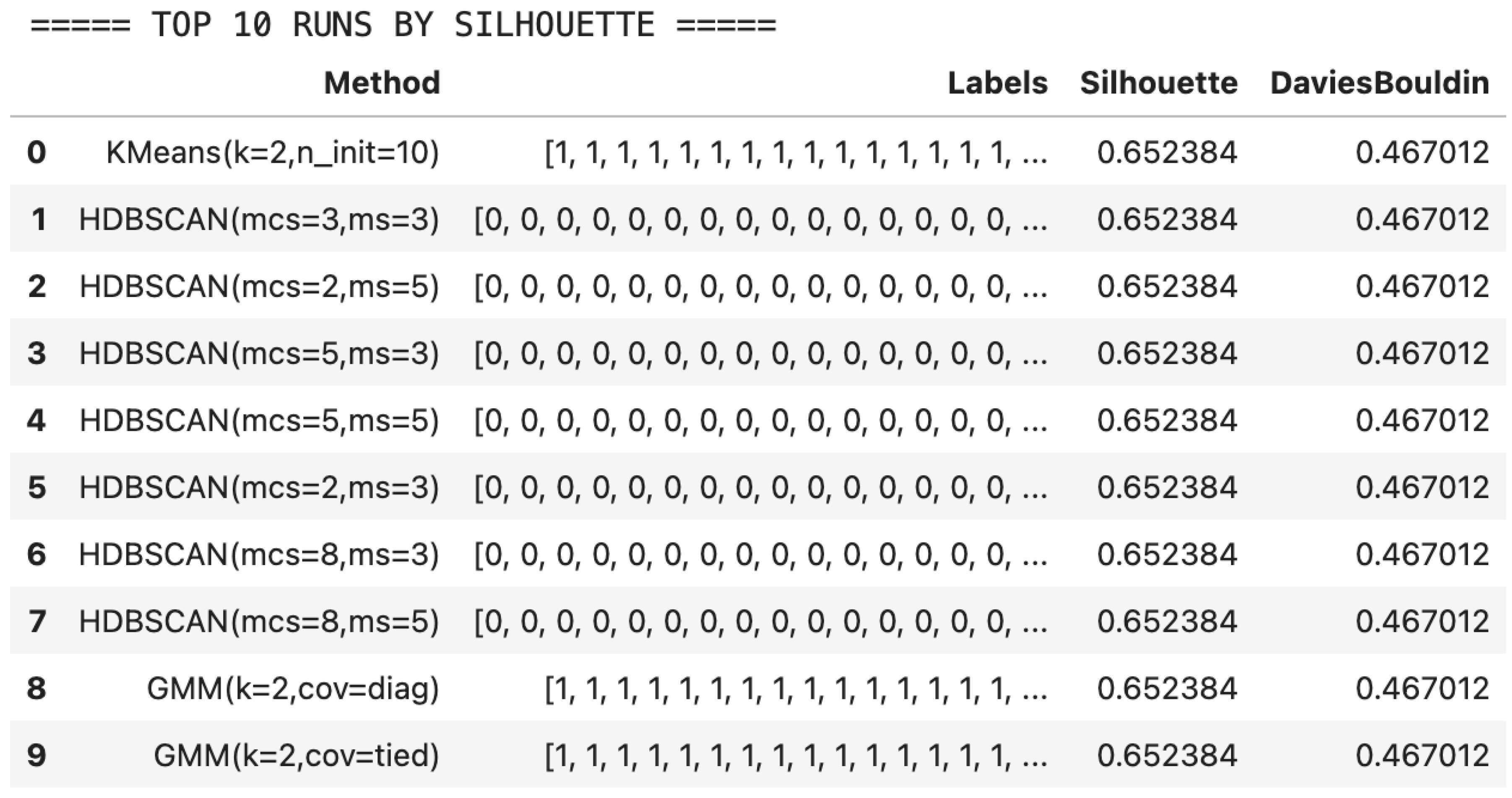

- Figure 1: Top 10 runs by silhouette score, with method name and final silhouette.

- Figure 2: Cluster vs. Group distribution table.

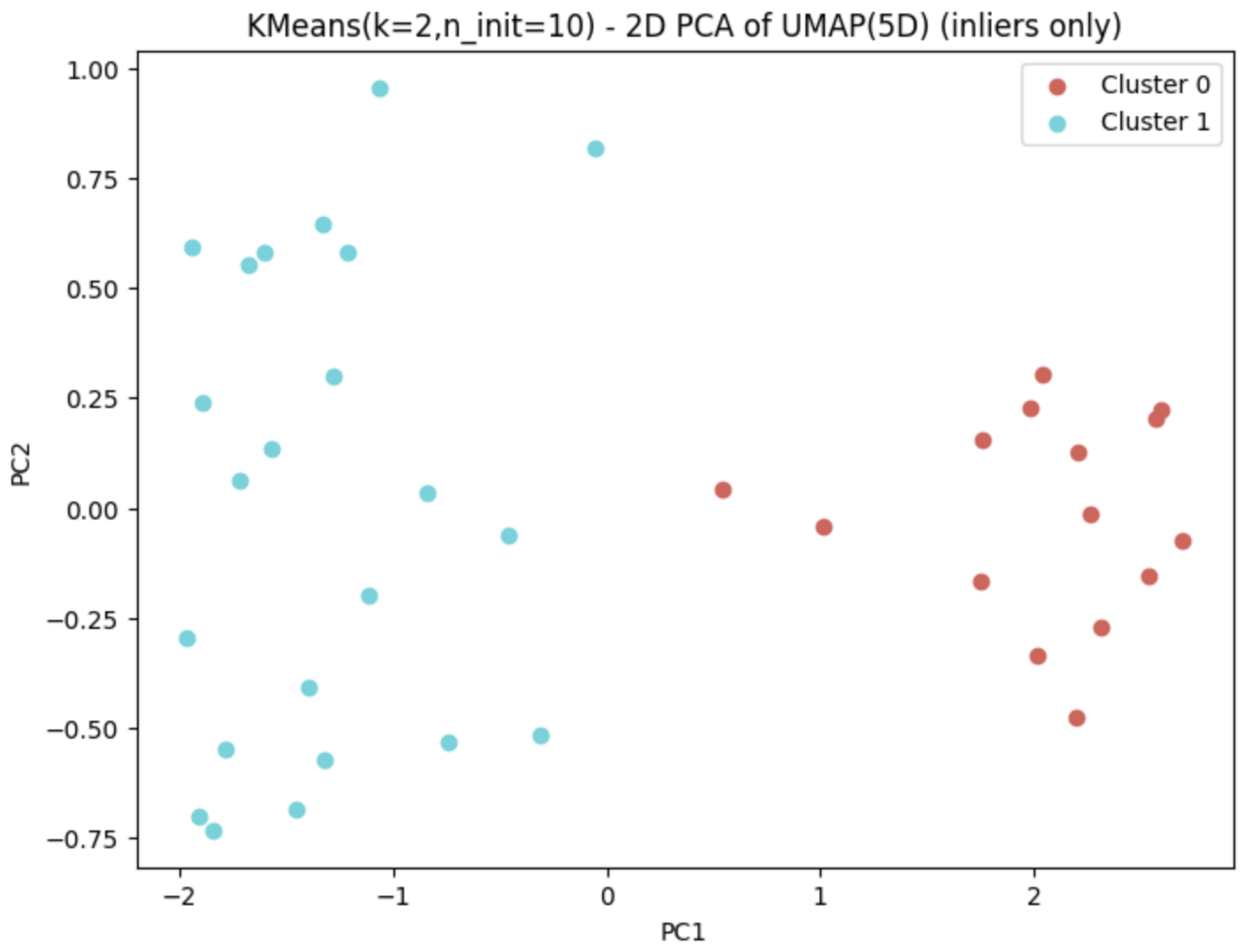

- Figure 3: 2D PCA projection of the 5D UMAP space, color-coded by cluster.

3. Results

3.1. Dataset Composition

3.2. Feature Selection and Correlation Filtering

3.3. UMAP Transformation

3.4. Clustering Performance

3.5. Cluster Purity at 92.11%

3.6. 2D Visualization of Final Clusters

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with Prior Research

- Restricting to Dyslexia-Relevant Features: Instead of letting hearing-based or purely audiometric frequencies dominate the variance, we curated a subset focusing on reading, memory, and phoneme tasks.

- Advanced Pipeline: The combination of correlation filtering, outlier removal, and UMAP captured crucial separations in the data.

- Extensive Hyperparameter Search: Instead of default clustering settings, we methodically tuned parameters, allowing K=2 with multiple n_init for KMeans, plus broad sweeps for DBSCAN’s eps/min_samples, etc.

4.2. Relation to the Speech-in-Noise (ACI) Studies

4.3. Innovations Beyond Previous Studies

- Extended Feature Scope: We leveraged not only reading and phoneme tasks but also memory spans, spelling error counts, and broader reading times to ensure a more holistic measure of dyslexic impairment.

- Unsupervised Approach: Previous studies typically used group-based comparisons (ANOVAs, t-tests, cross-prediction deviance) [16]. Our pipeline detects clusters de novo, demonstrating that participants self-group by reading and phonological variables.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: We systematically scanned across many algorithms and parameters, as recommended in data science [59].

4.4. Limitations

- Sample Size: Our final sample was 38 participants post-outlier removal. Although we achieved striking purity, small sample sizes can lead to overfitting or unstable cluster boundaries [60].

- Generalizability: The 92.11% figure may not hold in a broader population with more heterogeneous reading difficulties or comorbidities.

- Feature Selection Bias: We explicitly chose reading-related tasks. If a future dataset included strong morphological or semantic tasks overshadowing phoneme tasks, clusters might diverge from the present results [61].

- Noise and Reproducibility: UMAP can show variability if random seeds differ (though we used a fixed seed). Reproducibility is improved by specifying hyperparameters and random states [62].

4.5. Toward Clinical and Scientific Implications

5. Conclusion

References

- Shaywitz, SE. Dyslexia. N Engl J Med. 1998, 338, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyon GR, Shaywitz SE, Shaywitz BA. A definition of dyslexia. Ann Dyslexia. 2003, 53, 1–14.

- Snowling, MJ. Dyslexia. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 2000.

- Castles A, Coltheart M. Varieties of developmental dyslexia. Cognition. 1993, 47, 149–180.

- Pennington, BF. Diagnosing learning disorders: A neuropsychological framework. New York: Guilford Press; 2008.

- Ramus, F. Neurobiology of dyslexia: A reappraisal of the hypotheses. Brain. 2004, 127, 2269–2283. [Google Scholar]

- Lyytinen H, Erskine J, Tolvanen A, Poikkeus AM, Lyytinen P. Trajectories of reading development. J Exp Child Psychol. 2006, 93, 130–155.

- Kearns DM, Rogers HJ, Koriakin T, Al Ghanem R. Unsupervised cluster analysis of dyslexia subtypes. Ann Dyslexia. 2020, 70, 1–20.

- Cutting LE, Scarborough HS. Prediction of reading comprehension: Relative contributions of word recognition, language proficiency, and other cognitive skills can depend on how comprehension is measured. Sci Stud Read. 2006, 10, 277–299.

- Vellutino FR, Fletcher JM, Snowling MJ, Scanlon DM. Specific reading disability (dyslexia): what have we learned in the past four decades? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004, 45, 2–40.

- Goswami, U. A temporal sampling framework for developmental dyslexia. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011, 15, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallal, P. Auditory temporal perception, phonics, and reading disabilities in children. Brain Lang. 1980, 9, 182–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowling MJ, Hulme C. A developmental perspective on word reading, comprehension, and language in dyslexia. In: Cain K, Compton DL, Parrila R, editors. Theories of Reading Development. Amsterdam: John Benjamins; 2017. p. 51–71.

- Ziegler JC, Perry C, Ma-Wyatt A, Ladner D, Schulte-Körne G. Developmental dyslexia in different languages. Child Dev. 2003, 74, 756–769.

- Ziegler JC, Krügel A, Pinet S, et al. Dyslexic children show differences in the processing of auditorily presented pseudowords. Dev Sci. 2020, 23, e12929.

- Varnet L, Meunier F, Trollé G, Hoen M. Direct Viewing of Dyslexics’ Compensatory Strategies in Speech in Noise Using Auditory Classification Images. PLoS ONE. 2016, 11, e0153781.

- Saksida A, Ibbotson P, Hesketh A, Pollack R. Speech perception and compensation in dyslexia. Dev Psychol. 2017, 53, 370–383.

- Im-Bolter N, Johnson J, Pascual-Leone J. Processing limitations in children with specific language impairment: The role of executive function. Child Dev. 2006, 77, 1822–1841.

- Vogel I, Petersen MK, Werker JF. Using machine learning to identify dyslexic readers from EEG signals. Comput Biol Med. 2019, 107:238–247.

- Glutting JJ, Monaghan MC, Adams W. Cluster analysis of WISC-III subtest scores of poor readers. J Learn Disabil. 2002, 35, 270–279.

- Ahissar, M. Dyslexia and the anchoring deficit hypothesis. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007, 11, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus F, Szenkovits G. What phonological deficit? Q J Exp Psychol. 2008, 61, 129–141.

- Landerl K, Wimmer H, Frith U. The impact of orthographic consistency on dyslexia: A German-English comparison. Cognition. 1997, 63, 315–334.

- Guyon I, Gunn S, Nikravesh M, Zadeh L. Feature extraction: foundations and applications. Berlin: Springer; 2006.

- Rousseeuw PJ, Leroy AM. Robust Regression and Outlier Detection. New York: Wiley; 1987.

- McInnes L, Healy J, Melville J. UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction. arXiv:1802.03426 [preprint]. 2018.

- Ester M, Kriegel HP, Sander J, Xu X. A density-based algorithm for discovering clusters in large spatial databases with noise. KDD-96 Proc. 1996, 226–231.

- Manning CD, Raghavan P, Schütze H. Introduction to Information Retrieval. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

- Hoen M, Meunier F, Grataloup C, Julia L. Cognitive markers of dyslexia in speech perception tasks: The role of auditory classification images. In: The Proceedings of the International Conference on Dyslexia; 2015. p. 11–16.

- Elbro, C. Early linguistic abilities and reading development: A review and a hypothesis about underlying differences in distinctiveness of phonological representations. Read Writ. 1996, 8, 453–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013, 310, 2191–2194.

- Oldfield, RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971, 9, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raven JC, Court JH, Raven J. Manual for Raven’s Progressive Matrices and Vocabulary Scales. Oxford: Oxford Psychologists Press; 2000.

- Lefavrais, P. Test de l’Alouette. Les Editions du Centre de Psychologie Appliquée; 1965.

- Bruck, M. Word recognition skills of adults with childhood diagnoses of dyslexia. Dev Psychol. 1990, 26, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer J, Foss DM. Phonological coding and reading ability. Mem Cognit. 1992, 20, 144–148.

- Angelelli P, Notarnicola A, Judica A, Spinelli D, Luzzatti C. Spelling impairments in Italian dyslexic children: An orthographic, phonological, or morphological deficit? Cortex. 2010, 46, 1299–1311.

- Pelli DG, Tillman KA. Parts, wholes, and context in reading: A triple dissociation. PLoS ONE. 2008, 3, e2081.

- Fan J, McCandliss BD, Sommer T, Raz A, Posner MI. Testing the efficiency and independence of attentional networks. J Cogn Neurosci. 2002, 14, 340–347.

- Torgesen JK, Wagner RK, Rashotte CA. Longitudinal studies of phonological processing and reading. J Learn Disabil. 1994, 27, 276–286.

- Liu H, Motoda H. Feature Selection for Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. Boston: Springer; 1998.

- Hubert M, Van der Veeken S. Outlier detection for skewed data. J Chemom. 2008, 22(3–4):235–246.

- Becht E, McInnes L, Healy J, Dutertre CA, Kwok IWH, Ng LG, et al. Dimensionality reduction for visualizing single-cell data using UMAP. Nat Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 38–44.

- MacQueen, JB. Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. Proc 5th Berkeley Symp Math Stat Prob. 1967, 1:281–297.

- Murtagh F, Legendre P. Ward’s hierarchical agglomerative clustering method: which algorithms implement Ward’s criterion? J Classif. 2014, 31, 274–295.

- Schubert E, Sander J, Ester M, Kriegel HP, Xu X. DBSCAN revisited: why and how you should (still) use DBSCAN. ACM Trans Database Syst. 2017, 42, 19.

- Ng AY, Jordan MI, Weiss Y. On spectral clustering: Analysis and an algorithm. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2002, 14, 849–856.

- Bishop, CM. Pattern recognition and machine learning. New York: Springer; 2006.

- Campello RJGB, Moulavi D, Sander J. Density-based clustering based on hierarchical density estimates. In: Pacific-Asia Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. Berlin: Springer; 2013. p. 160–172.

- Rousseeuw, PJ. Silhouettes: A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. J Comput Appl Math. 1987, 20:53–65.

- Davies DL, Bouldin DW. A cluster separation measure. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 1979, 1, 224–227.

- Manning CD, Raghavan P, Schütze H. Cluster purity measure: Implementation details. In: Introduction to Information Retrieval. Cambridge: CUP; 2008. p. 349–350.

- Hulme C, Snowling MJ. Reading disorders and dyslexia. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2013, 25, 731–735.

- Ramus F, Ahissar M. Developmental dyslexia: The difficulties of interpreting poor performance, and the importance of normal performance. Cogn Neuropsychol. 2012, 29(1–2):104–122.

- Van der Maaten L, Postma E, Herik H. Dimensionality reduction: a comparative. J Mach Learn Res. 2009, 10:66–71.

- Maaten L, Hinton G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J Mach Learn Res. 2008, 9:2579–2605.

- Swanson E, Yu J, Markaki V, Shinn-Cunningham BG. Behavioral classification images reveal reduced weighting of frequency-specific temporal cues in older listeners. Ear Hear. 2019, 40, 902–917.

- McInnes L, Healy J. UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection. J Open Source Softw. 2018, 3, 861.

- Bergstra J, Bengio Y. Random search for hyper-parameter optimization. J Mach Learn Res. 2012, 13:281–305.

- Fokkema M, Smits N, Kelderman H, Cuijpers P. Response bias in self-report data. Psychol Assess. 2012, 24, 170–176.

- Paulesu E, Danelli L, Berlingeri M. Reading the dyslexic brain: multiple dysfunctional routes revealed by a new meta-analysis of PET and fMRI activation studies. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014, 8:830.

- Reimers N, Gurevych I. Reporting score distributions makes a difference: Performance study of LSTM-networks for sequence tagging. In: Proc of EMNLP. 2017. p. 338–348.

- Thapliyal V, Arnett AB, Willcutt E. Data-driven subtyping of reading disability: Searching for robust subtypes. J Learn Disabil. 2021, 54, 393–406.

- Shaywitz BA, Shaywitz SE. Dyslexia (Specific Reading Disability). Biol Psychiatry. 2005, 57, 1301–1309.

- Ziegler JC, Pech-Georgel C, Dufau S, Grainger J. Rapid processing of letters, digits and symbols: What purely visual-attentional deficit in developmental dyslexia? Dev Sci. 2010, 13, F8–F14.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).