Submitted:

20 May 2025

Posted:

21 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Experimental Design

2.2. Noise Exposure

2.3. Biochemical Analysis

- Fraction preparation.

- 1-D Electrophoresis and Western Blotting.

2.4. EM Study. Perfusion and Brain Processing

2.5. Statistical Analysis—Biochemical Study

3. Results

3.1. Immunostaining

3.2. Proteins Involved in Synaptic Vesicle Exocytosis—Long-Term Exposure to Loud Noise Induces Upregulation of Synaptophysin in the Hippocampal REGION

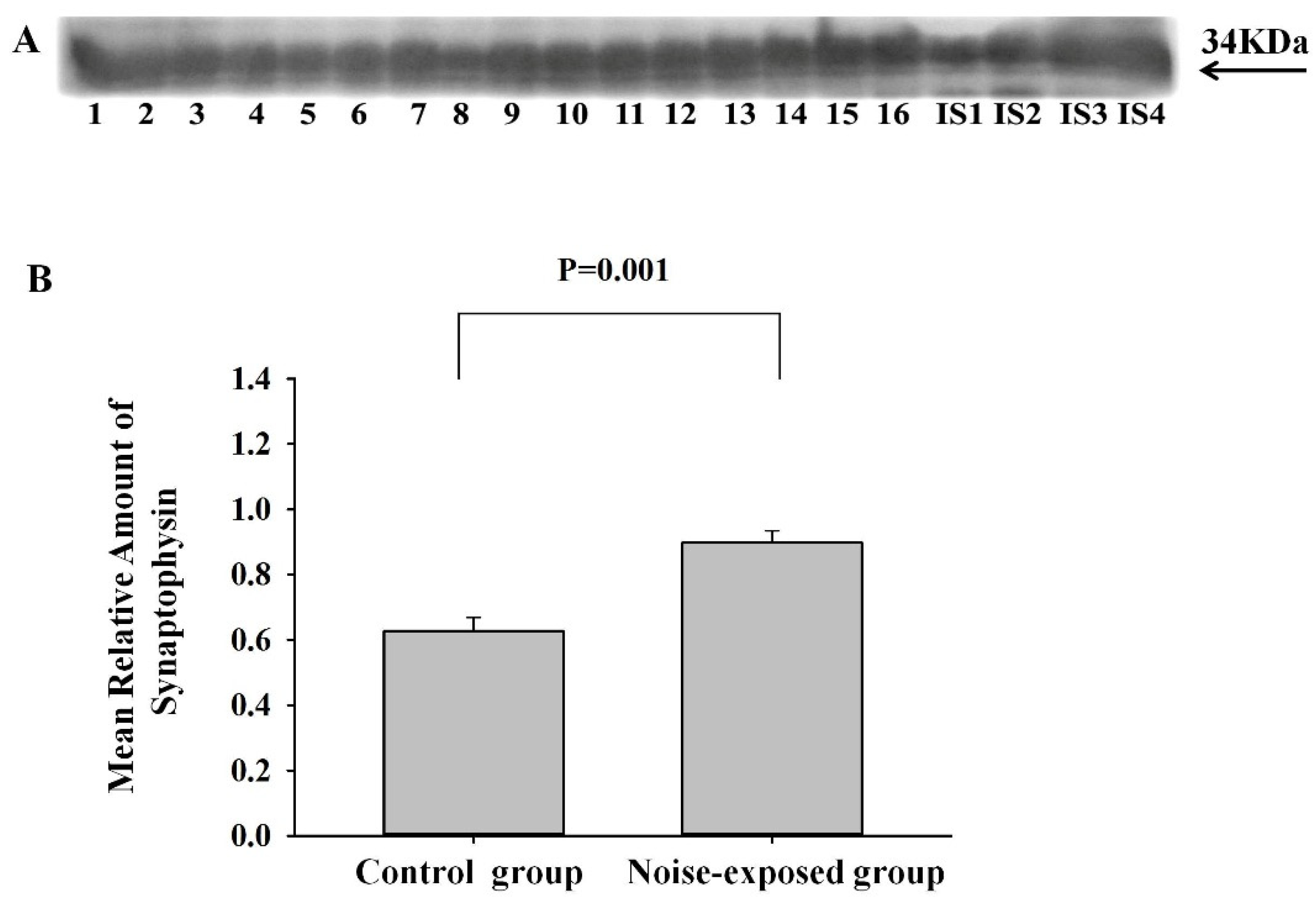

3.2.1. Synaptophysin

3.2.2. SNAP25 and Syntaxin

3.3. Proteins Involved in Neuroinflammation—Long-Term Exposure to Loud Noise Increases the Level of These Proteins in CNIC and Decreases in BLA

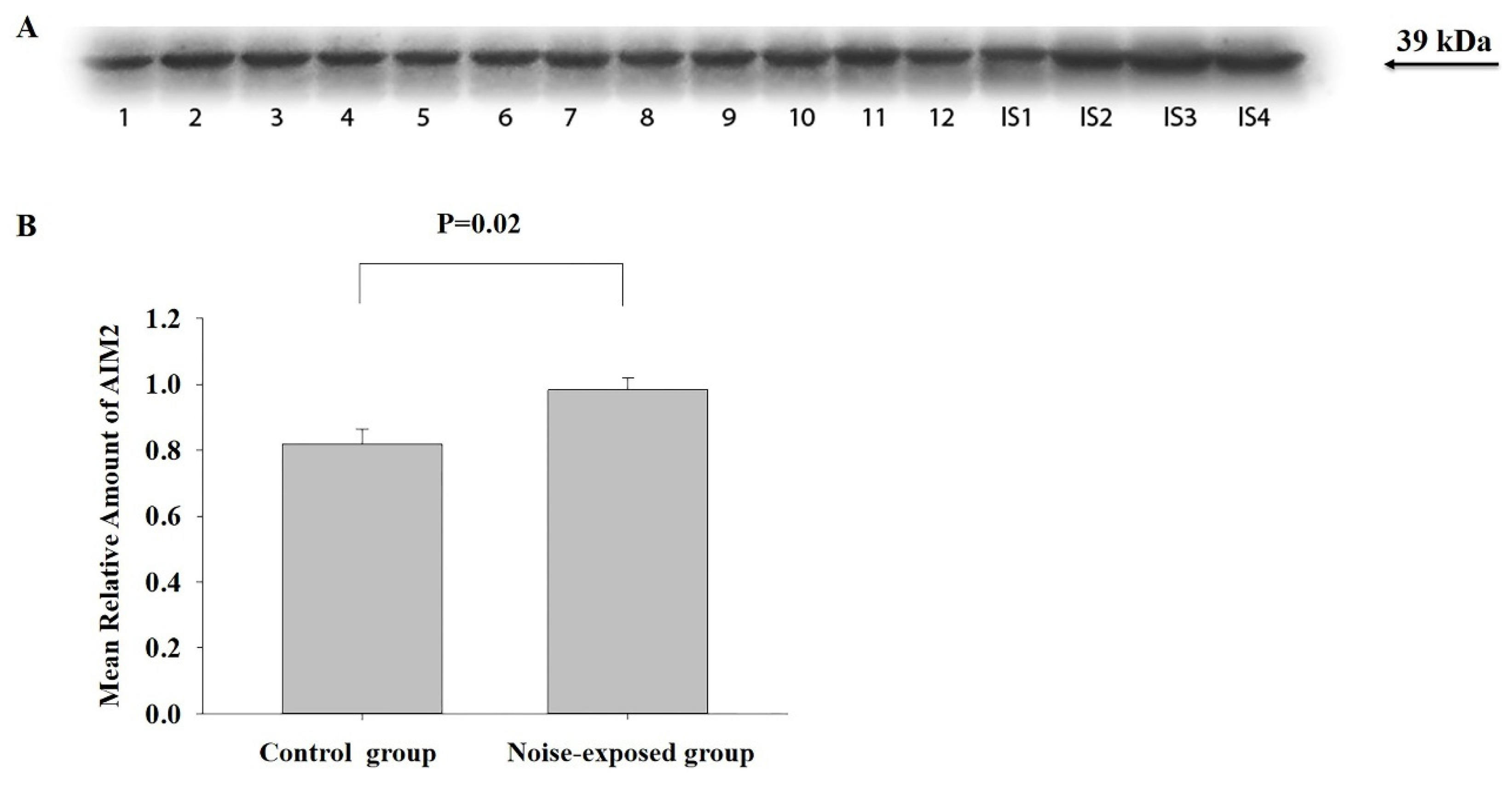

3.3.1. AIM2

CNIC

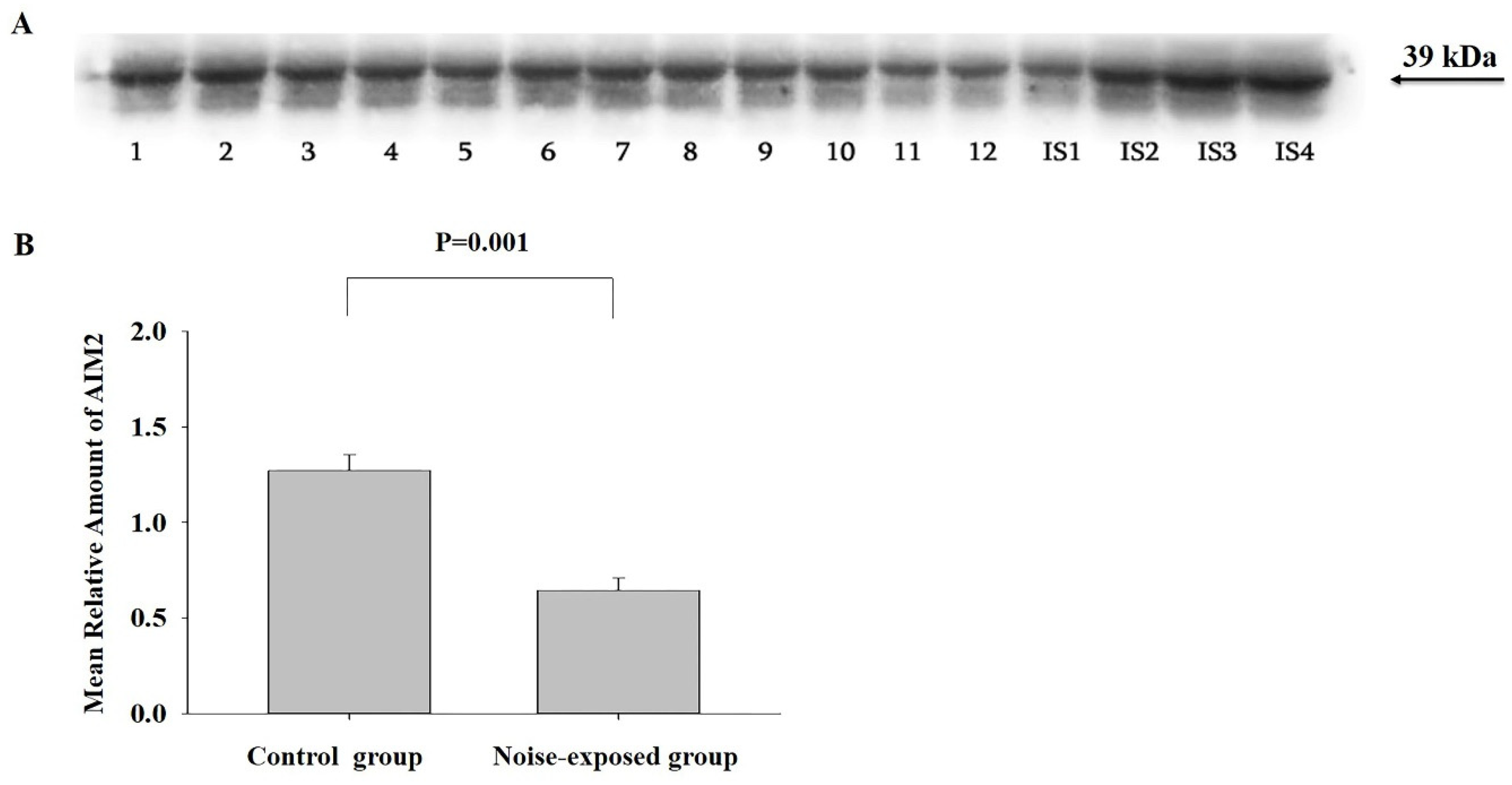

BLA

The Hippocampal Area

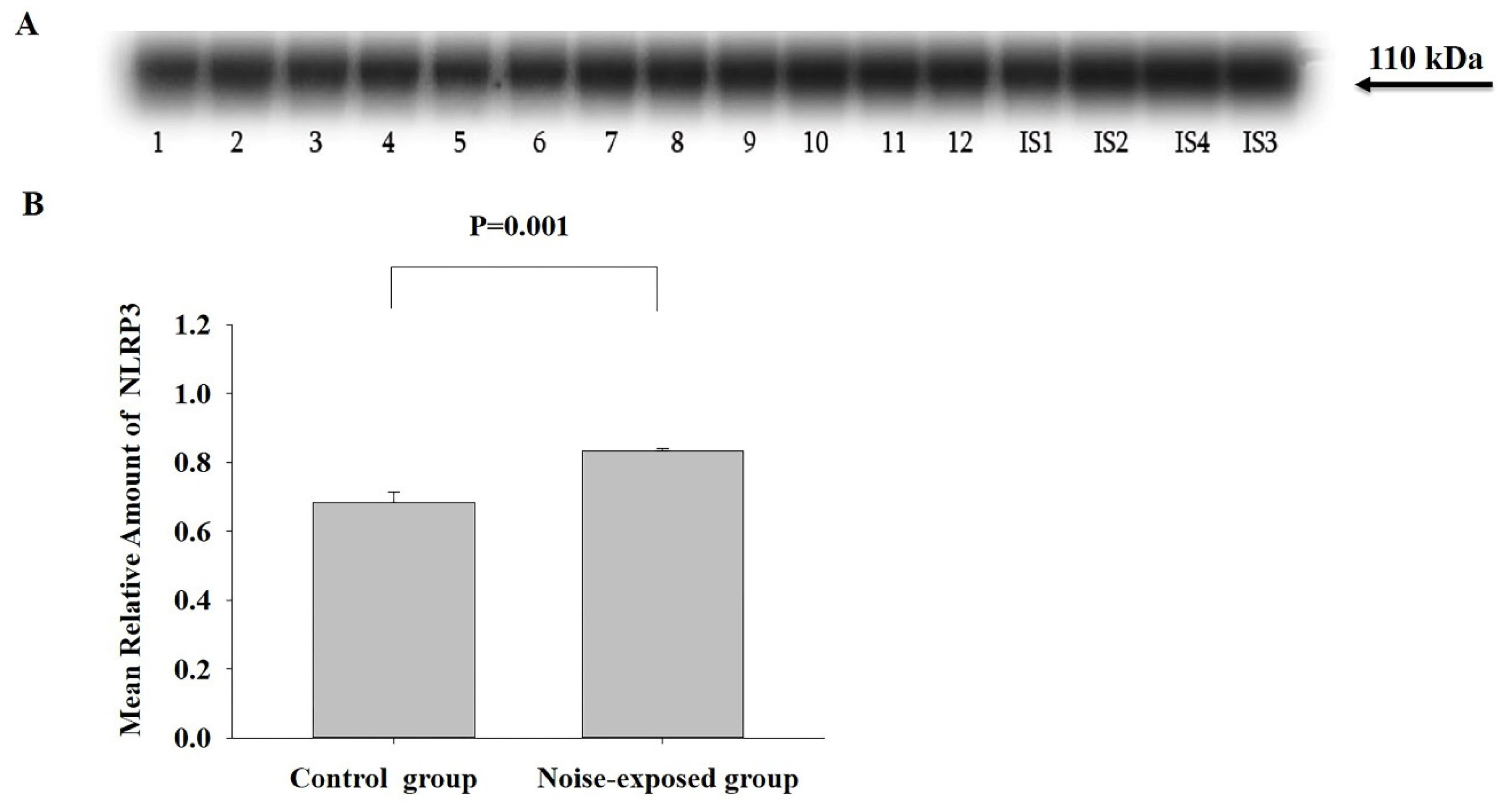

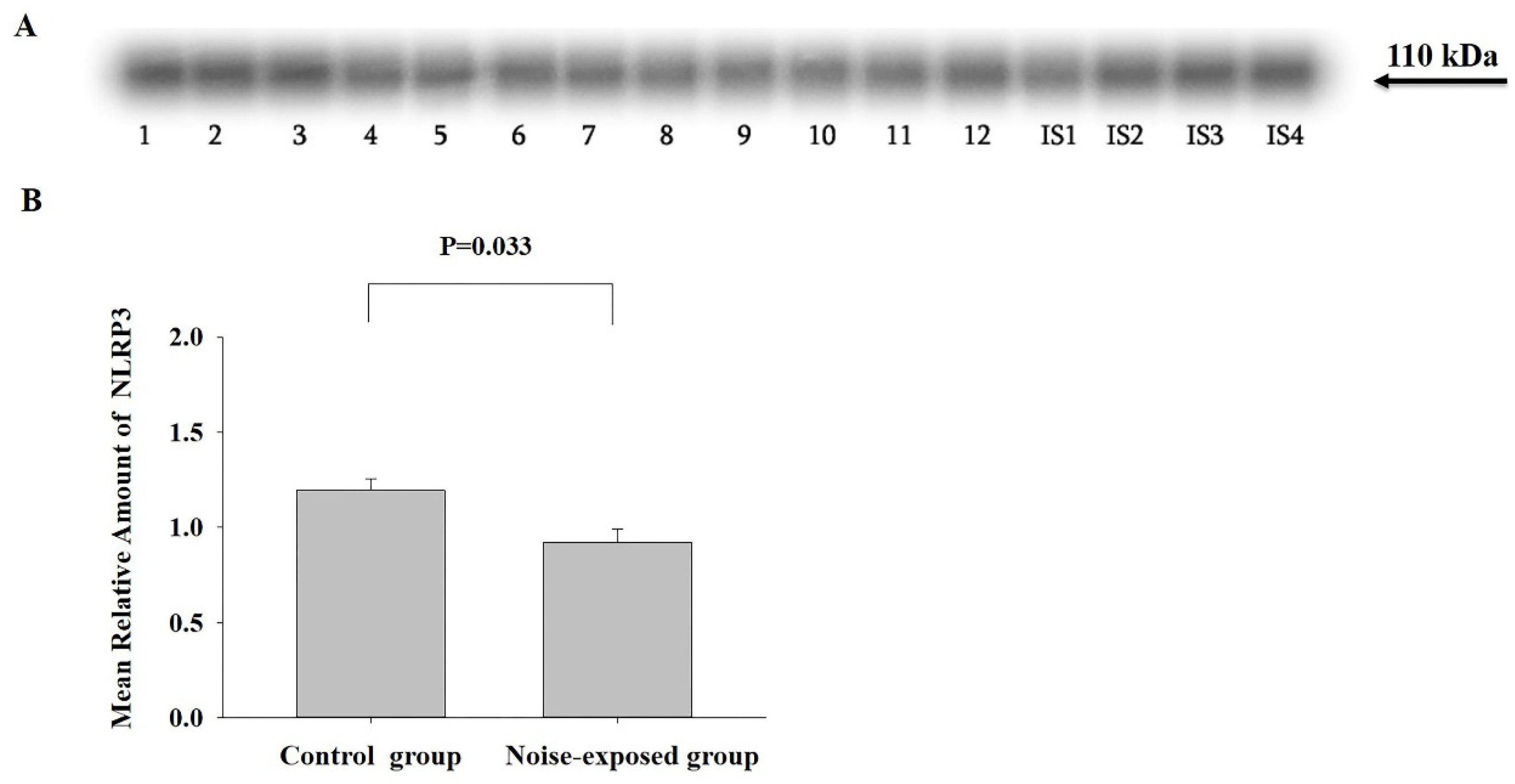

3.3.2. NLRP3

CNIC

BLA

The Hippocampus

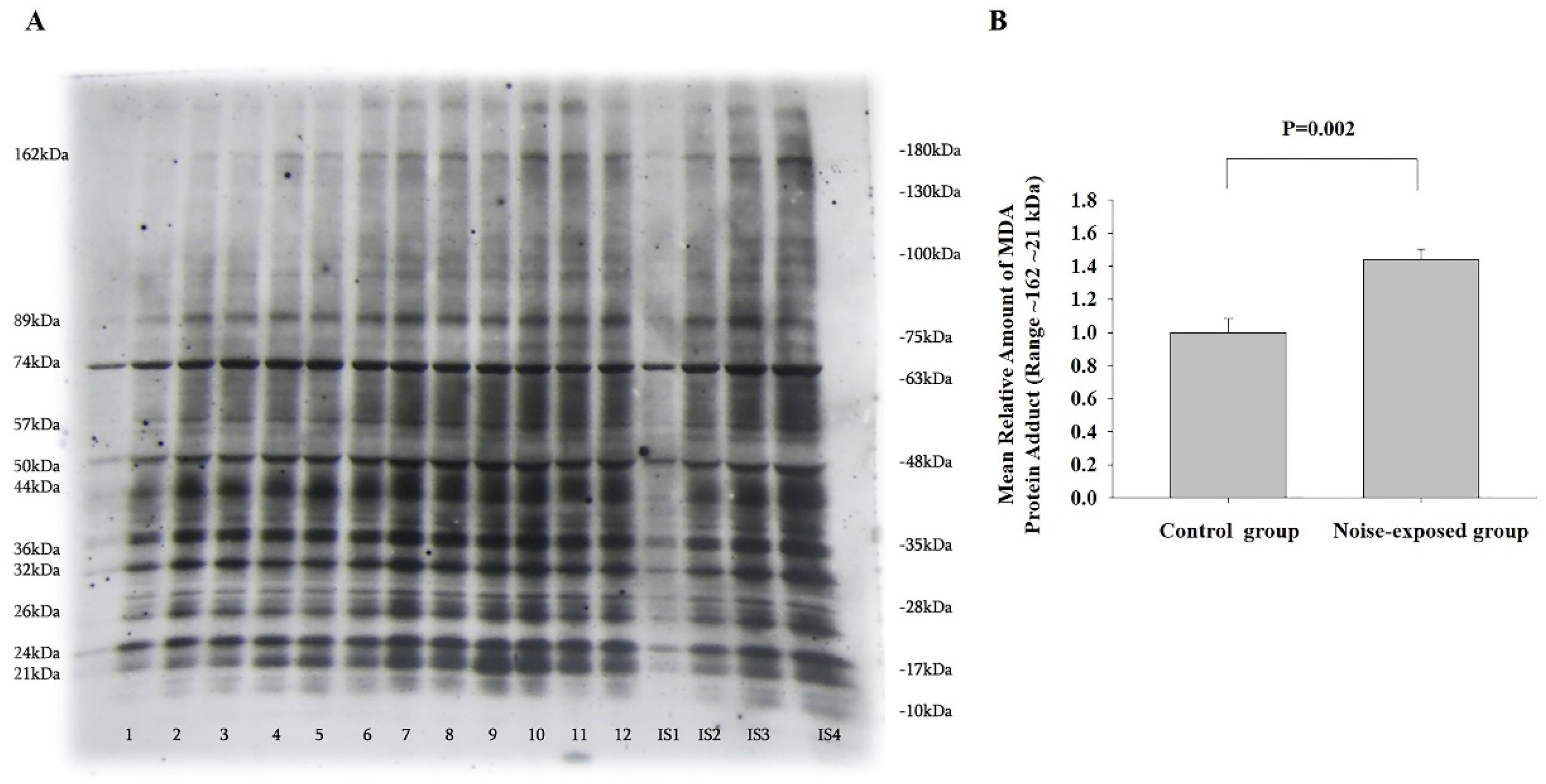

3.4. Long-Term Exposure to Loud Noise Increases the Level of MDA-Protein Adducts in CNIC

CNIC

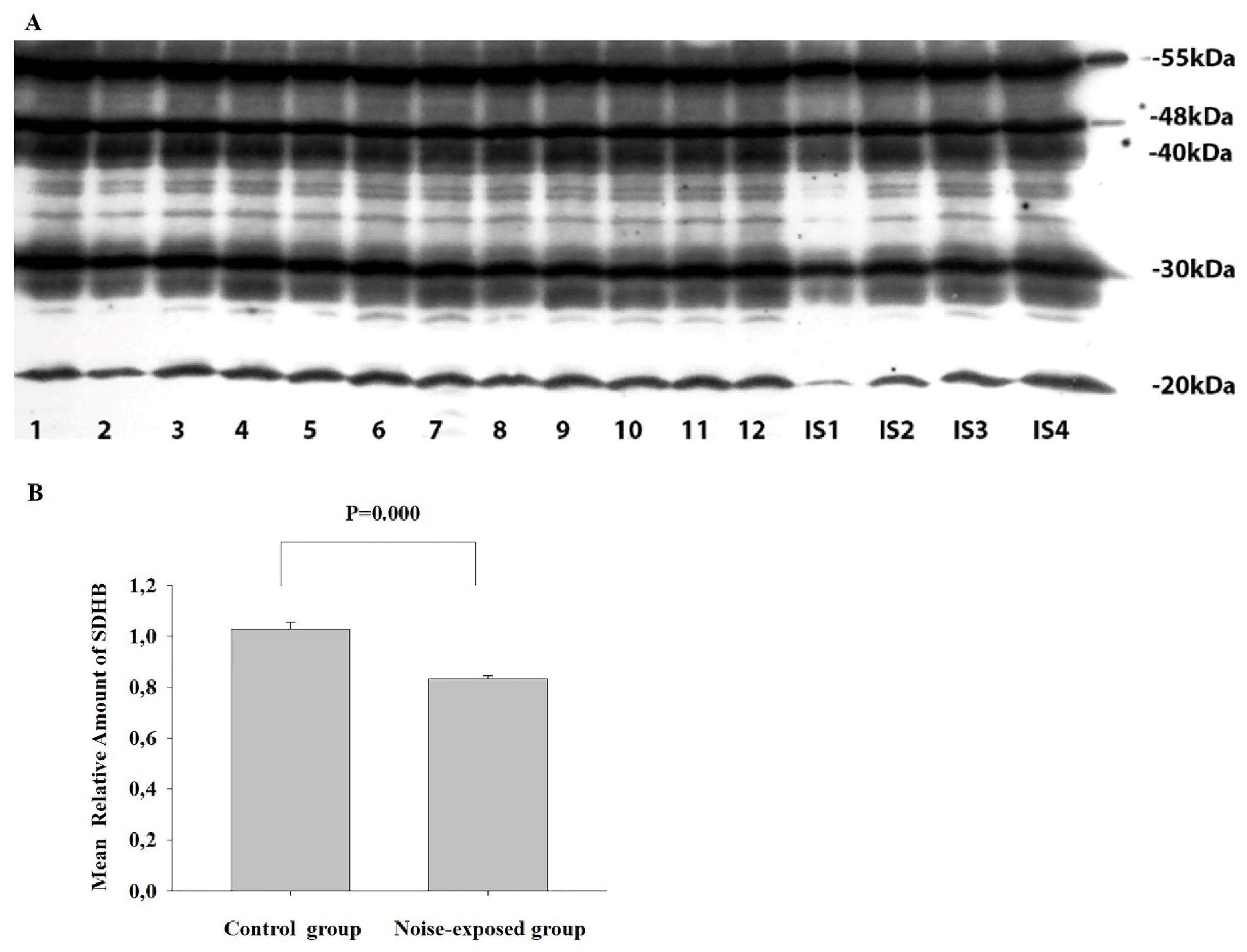

3.5. Long-Term Exposure to Loud Noise Affects the Level of Proteins Involved in Oxidative Phosphorylation and ATP Synthase FoF1 Complex—Deficiency of Succinate Dehydrogenase Complex in the Hippocampal Area of Noise-Exposed Rats

3.5.1. ATP5A, UQCRC2, MTCO1 and NDUFB8

3.5.2. SDHB

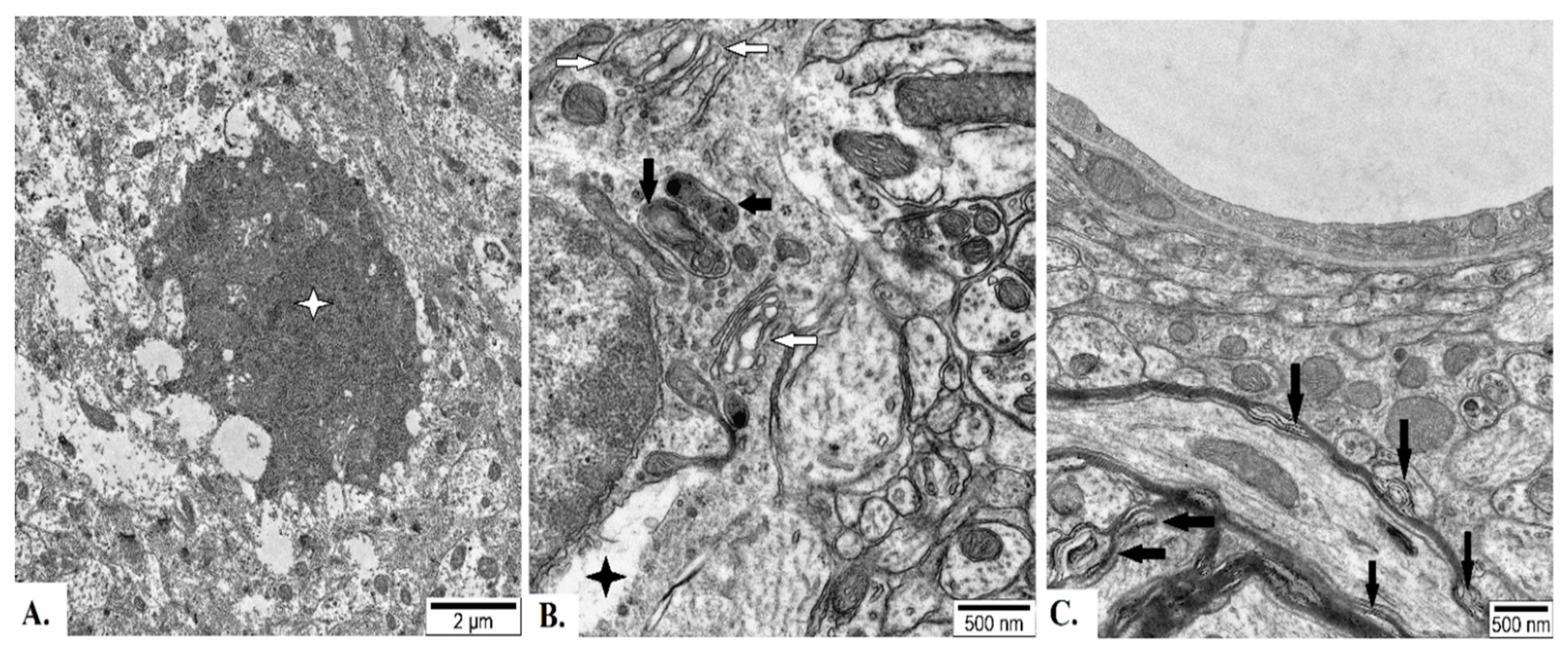

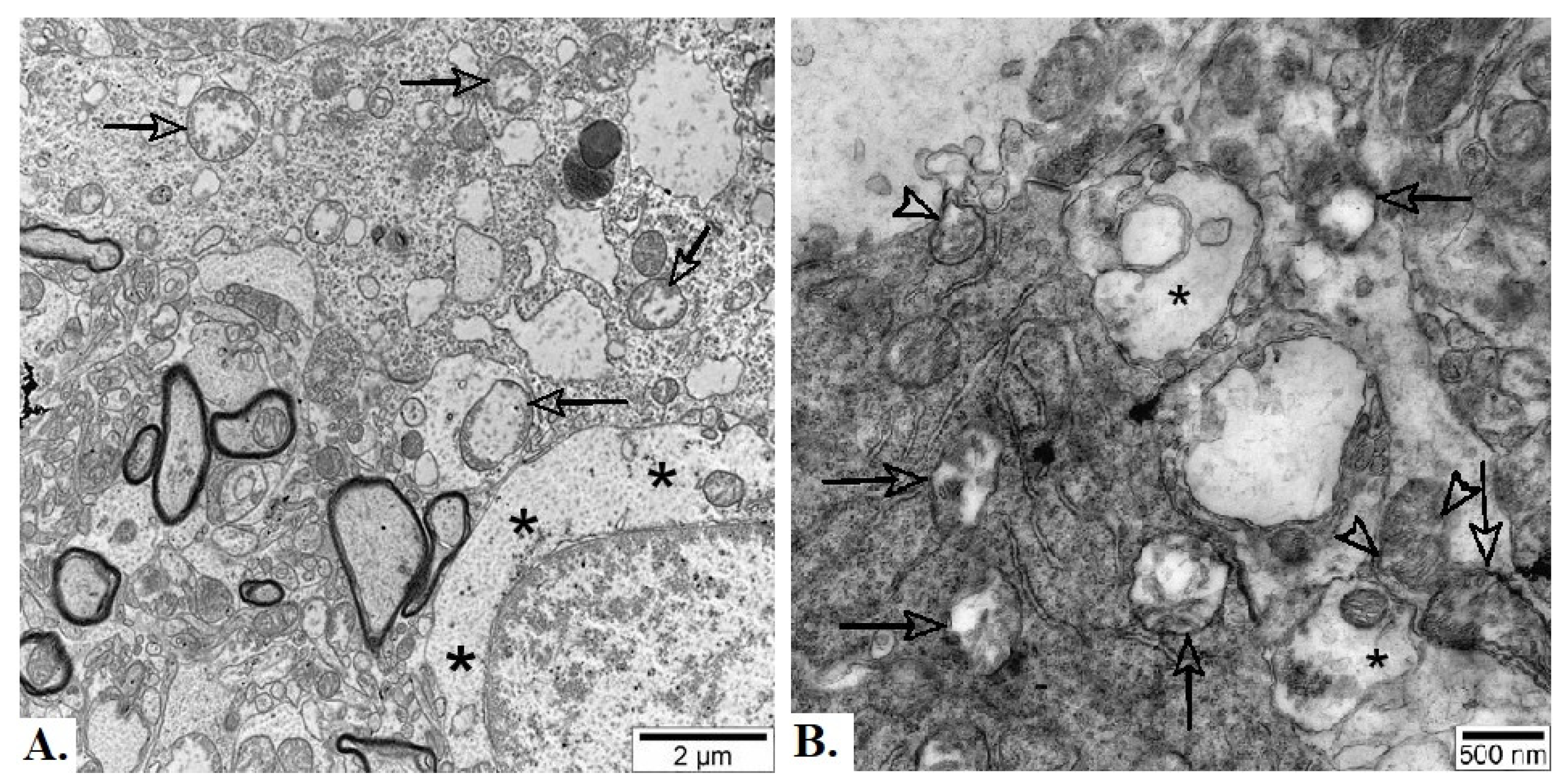

3.6. EM Study—Long-Term Exposure to Loud Noise Affects the Ultrastructure of CNIC, BLA and the Hippocampus

4. Discussion

4.1. Biochemical Alterations

4.1.1. Synaptic Vesicles

4.1.2. Neuroinflammation

4.1.3. MDA-Protein Adducts

4.1.4. Mitochondria

4.1.5. Possible Сross Talk Between Neuroinflammation, Lipid Peroxidation and Mitochondrial Dysfunction After Chronic Exposure to Loud Noise Could Lead to the Major Pathological Changes

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krenz, K., Dhanani, A., McEachan, R.R.C., Sohal, K., Wright, J., Vaughan, L. Linking the Urban Environment and Health: An Innovative Methodology for Measuring Individual-Level Environmental Exposures. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2023, 20;20(3):1953. [CrossRef]

- Le Prell, C.G., Clavier, O.H., Bao, J. Noise-induced hearing disorders: Clinical and investigational tools. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2023, 153(1):711. [CrossRef]

- Kempen, E.V., Casas, M., Pershagen, G., Foraster, M. WHO Environmental Noise Guidelines for the European Region: A Systematic Review on Environmental Noise and Cardiovascular and Metabolic Effects: A Summary. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018, 22;15(2):379. [CrossRef]

- Münzel, T., Daiber, A., 2013. Vascular Redox Signaling, Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase Uncoupling, and Endothelial Dysfunction in the Setting of Transportation Noise Exposure or Chronic Treatment with Organic Nitrates. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 13-15, 1001-1021. [CrossRef]

- Arjunan, A., Rajan, R. Noise and brain. Physiol. Behav. 2020, Dec 1;227:113136. [CrossRef]

- Cho, I., Kim, J., Jung, S., Kim, S.Y., Kim, E.J., Choo, S., Kam, E.H., Koo, B.N. The Impact of Persistent Noise Exposure under Inflammatory Conditions. Healthcare (Basel). 2023, Jul 19;11(14):2067. [CrossRef]

- Almasabi, F., van Zwieten, G., Alosaimi, F., Smit, J.V., Temel, Y., Janssen, M.L.F., Jahanshahi, A., 2022. The Effect of Noise Trauma and Deep Brain Stimulation of the Medial Geniculate Body on Tissue Activity in the Auditory Pathway. Brain Sci. 2020, Aug 18;12(8):1099. [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, N., Batts, S., Stankovic, K.M. Noise-Induced Hearing Loss. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 17;12(6):2347. [CrossRef]

- Aime, M., Augusto, E., Kouskoff, V., Campelo, T., Martin, C., Humeau, Y., Chenouard, N., Gambino, F. The integration of Gaussian noise by long-range amygdala ininputs in frontal circuit promotes fear learning in mice. Elife. 2020 Nov 30;9:e62594. [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, N.M., Wilson, S.J. The Contribution of Brainstem and Cerebellar Pathways to Auditory Recognition. Front. Psychol. 2017, 20;8:265. [CrossRef]

- Oberle, H.M., Ford, A.N., Czarny, J.E., Rogalla, M.M., Apostolidis, P.F. Recurrent Circuits Amplify Corticofugal Signals and Drive Feedforward Inhibition in the Inferior Colliculus. J. Neurosci. 2023, 43, 5642-5655. [CrossRef]

- Gruene, T., Flick. K., Rendall, S., Cho, J.H., Gray, J., Shansky, R. Activity-dependent structural plasticity after aversive experiences in amygdala and auditory cortex pyramidal neurons. Neuroscience, 2016, 22;328:157-64. [CrossRef]

- Tempest, G.D., Parfitt, G. Prefrontal oxygenation and the acoustic startle eye blink response during exercise: A test of the dual-mode model. Psychophysiology, 2017, 54, 1070-1080. [CrossRef]

- Asokan, M.M., Watanabe, Y., Kimchi, E.Y., Polley, D.B. Potentiated cholinergic and corticofugal inputs support reorganized sensory processing in the basolateral amygdala during auditory threat acquisition and retrieval. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2023, Feb 2:2023.01.31.526307. [CrossRef]

- Billig, A.J., Lad, M., Sedley, W., Griffiths, T.D. The hearing hippocampus. Prog. Neurobiol. 2022, Nov;218:102326. [CrossRef]

- Cusinato, R., Alnes, S.L, van Maren, E., Boccalaro, I., Ledergerber, D., Adamantidis, A., Imbach, L.L., Schindler, K., Baud, M.O., Tzovara, A. Intrinsic Neural Timescales in the Temporal Lobe Support an Auditory Processing Hierarchy. J. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 3696-3707. [CrossRef]

- Jena, B.P. Role of SNAREs in membrane fusion. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2011, 713, 13-32. [CrossRef]

- Rizo, J. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Neurotransmitter Release. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2022, 51, 377-408. [CrossRef]

- Platnich, J.M., Muruve, D.A. NOD-like receptors and inflammasomes: A review of their canonical and non-canonical signaling pathways. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2019, 30, 4-14. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., Zhang, L.S., Zinsmaier, A.K., Patterson, G., Leptich, E.J., Shoemaker, S.L, Yatskievych, T.A., Gibboni, R., Pace, E., Luo, H., et al. Neuroinflammation mediates noise-induced synaptic imbalance and tinnitus in rodent models. PLoS Biol. 2019, 17(6):e3000307. [CrossRef]

- Gogokhia, N., Japaridze, N., Tizabi, Y., Pataraya, L., Zhvania, M.G. Gender differences in anxiety response to high intensity white noise in rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2021, Jan 18;742:135543. [CrossRef]

- Zhvania, M., Gogokhia, N., Tizabi, Y., Japaridze, N., Pochkidze, N., Lomidze, N., Rzayev, F., Gasimov E. Behavioral and neuroanatomical effects on exposure to White noise in rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2020, 29;728:134898. [CrossRef]

- Paxinos, G. and Watson, C. (2006) The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Sixth Edition, Academic Press, Cambridge.

- Golubiani, G., van Agen, L., Tsverava, L., Solomonia, R., Müller, M. Mitochondrial Proteome Changes in Rett Syndrome. Biology (Basel). 2023, Jul 3;12(7):956. [CrossRef]

- Dittmer, A., Dittmer, J. Beta-actin is not a reliable loading control in Western blot analysis. Electrophoresis. 2006, 27, 2844-5. [CrossRef]

- Meparishvili, M., Nozadze, M., Margvelani, G., McCabe, B.J., Solomonia, R.O. A Proteomic Study of Memory After Imprinting in the Domestic Chick. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2015, 9:319. [CrossRef]

- Pochkhidze, N., Gogokhia, N., Japaridze, N., Lazrishvili, I., Bikashvili, T., Zhvania, M.G. 2021. Electron microscopy demonstrating noise exposure alters synaptic vesicle size in the inferiorcolliculus of cat. Noise Health. 2021, 23, 51-56. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, C.M., Palmerton, H., Saway, B., Tomlinson, D., Simonds, G. Effect of Various OR Noise on Fine Motor Skills, Cognition, and Mood. Surg. Res. Pract. 2019, Jul 4;2019:5372174. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R., Smith, R.B., Bou Karim, Y., Shen, C., Drummond, K., Teng, C., Toledano, M.B. Noise pollution and human cognition: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of recent evidence. Environ. Int. 2022, Jan;158:106905. [CrossRef]

- Bera, M., Radhakrishnan, A., Coleman, J., Venkat, R., Sundara, K., R.V., Ramakrishnan, S., Pincet, F., Rothma, J.E. Synaptophysin chaperones the assembly of 12 SNAREpins under each ready-release vesicle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2023, Nov 7;120(45):e2311484120. Epub 2023 Oct 30. Erratum in: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024 Feb 6;121(6):e2400216121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2400216121. [CrossRef]

- Lavinsky, J., Kasperbauer, G., Bento, R.F., Mendonca, A., Wang, J., Crow, A.L., Allayee, H., Friedman R.A. Noise exposure and distortion product otoacoustic emission suprathreshold amplitudes: a genome-wide association study. Audiol. Neurootol. 2021, 26, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Voet S, Srinivasan S, Lamkanfi M, van Loo G. Inflammasomes in neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases. EMBO Mol Med. 2019 Jun;11(6):e10248. [CrossRef]

- Lamkanfi, M., Dixit, V.M. Inflammasomes and their roles in health and disease. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2012, 28, 137-61. [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.F., Tan, L., Tan, M.S., Jiang, T., Tan, C.C., Li, M.M., Wang, H.F., Yu, J.T. Inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome provides neuroprotection in rats following amygdala kindling-induced status epilepticus. J. Neuroinflammation. 2014, 17;11:212. [CrossRef]

- Liang, P., Zhang, X., Zhang, Y., Wu, Y., Song, Y., Wang, X., Chen, T., Liu, W., Peng, B., Yin, J., et al. Neurotoxic A1 astrocytes promote neuronal ferroptosis via CXCL10/CXCR3 axis in epilepsy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 195, 329-342. [CrossRef]

- Ranganayaki, S., Jamshidi, N., Aiyaz, M., Rashmi, S.K., Gayathri, N., Harsha, P.K., Padmanabhan, B., Srinivas Bharath, M.M. Inhibition of mitochondrial complex II in neuronal cells triggers unique pathways culminating in autophagy with implications for neurodegeneration. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11(1):1483. [CrossRef]

- Solomonia, R.O., Kunelauri, N., Mikautadze, E., Apkhazava, D., McCabe, B.J., Horn, G. Mitochondrial proteins, learning and memory: biochemical specialization of a memory system. Neuroscience. 2011, 194, 112-23. [CrossRef]

- Margvelani, G., Meparishvili, M., Tevdoradze, E., McCabe, B.J., Solomonia, R. Mitochondrial fusion and fission proteins and the recognition memory of imprinting in domestic chicks. Neuroreport 2018, 29,128-133. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D., Jia, G., Zhang, Y., Mao, H., Zhao, L., Li, W., Chen, Y., Ni, Y. Sox2 overexpression alleviates noise-induced hearing loss by inhibiting inflammation-related hair cell apoptosis. J. Neuroinflammation. 2022, Feb 28;19(1):59. [CrossRef]

- Op de Beeck, K., Schacht, J., Van Camp, G. Apoptosis in acquired and genetic hearing impairment: the programmed death of the hair cell. Hear Res. 2011, 281, 18-27. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., Ye. J., Kong. W., Zhang, S. Zheng, Y. Programmed cell death pathways in hearing loss: A review of apoptosis, autophagy and programmed necrosis. Cell Prolif. 2020, Nov;53(11):e12915. [CrossRef]

- Oshitari, T. Neurovascular Cell Death and Therapeutic Strategies for Diabetic Retinopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24(16):12919. [CrossRef]

- Tang, D., Ch. X., Kang, R., Kroemer, G. Ferroptosis: molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell Res. 2020, 31, 107-125. [CrossRef]

- Guha, L., Singh, N., Kumar, H. Different Ways to Die: Cell Death Pathways and Their Association with Spinal Cord Injury. Neurospine. 2023, 20, 430-448. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X., Xu, Y., Xu, H., Jin, C., Zhang, H., Su, H., Li, Y., Zhou, K., Ni, W. Progress in Understanding Ferroptosis and Its Targeting for Therapeutic Benefits in Traumatic Brain and Spinal Cord Injuries. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2021, 4;9:705786. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Fang, Z.M., Yi, X., Wei, X., Jiang, D.S. The interaction between ferroptosis and inflammatory signaling pathways. Cell Death Dis. 2023, Mar 21;14(3):205. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Gao, X., Zhou, S., 2020. New Target for Prevention and Treatment of Neuroinflammation: Microglia Iron Accumulation and Ferroptosis. ASN Neuro. 2020, 14:17590914221133236. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L., Yuan L., Li. W., Li, J.Y. Ferroptosis in Parkinson's disease: glia-neuron crosstalk. Trends Mol, Med. 2022, 28, 258-269. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.J, Lemberg, K.M., Lamprecht, M.R., Skouta, R., Zaitsev, E.M., Gleason, C.E., Patel, D.N., Bauer, A.J., Cantley, A.M., Yang, W.S. et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012, 149, 1060-72. [CrossRef]

- Costigan, A., Hollville, E., Martin, S.J., 2023. Discriminating Between Apoptosis, Necrosis, Necroptosis, and Ferroptosis by Microscopy and Flow Cytometry. Curr. Protoc. 2023, Dec;3(12):e951. [CrossRef]

- Tan, X., He, Y., Yu, P., Deng, Y., Xie, Z., Guo, J., Hou, Q., Li, P., Lin, X., Ouyang, S. et al. The dual role of FSP1 in programmed cell death: resisting ferroptosis in the cell membrane and promoting necroptosis in the nucleus of THP-1 cells. Mol. Med. 2024, Jul 15;30(1):102. [CrossRef]

- Miyake, S., Murai, S., Kakuta, S., Uchiyama, Y., Nakano, H. Identification of the hallmarks of necroptosis and ferroptosis by transmission electron microscopy. Biochem. Biophys.Res. Commun. 2020, 527, 839-844. [CrossRef]

- Jian, B., Pang, J., Xiong, H., Zhang, W., Zhan, T., Su, Z., Lin, H., Zhang, H., He, W., Zheng, Y. Autophagy-dependent ferroptosis contributes to cisplatin-induced hearing loss. Toxicol. Lett. 2021, 10, 249-260. [CrossRef]

- Tisato, V., Castiglione, A., Ciorba, A., Aimoni, C., Silva, J.A., Gallo, I., D'Aversa, E., Salvatori, F., Bianchini, C., Pelucchi, S. et al. LINE-1 global DNA methylation, iron homeostasis genes, sex and age in sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSNHL). Hum. Genomics. 2023, 17(1):112. [CrossRef]

- Gao, W., Wang, X., Zhou, Y., Wang, X., Yu, Y. Autophagy, ferroptosis, pyroptosis, and necroptosis in tumor immunotherapy. Sig. Transduct. Target Ther. 2023, Jun 20;7(1):196. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Li, Z., Li, B., Liu, W., Zhang, S., Qiu, K., Zhu, W. Relationship between ferroptosis and mitophagy in cardiac ischemia reperfusion injury: a mini-review. PeerJ. 2023, Mar 13;11:e14952. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., Zou, S., He, Z., Chen, X. The role of autophagy and ferroptosis in sensorineural hearing loss. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16:1068611. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, He W, Zhang J. A richer and more diverse future for microglia phenotypes. Heliyon. 2023, Mar 21;9(4):e14713. [CrossRef]

- Bisht, K., Sharma, K.P., Lecours, C., Sánchez, M.G., El Hajj, H., Milior, G., Olmos-Alonso, A., Gómez-Nicola, D., Luheshi, G., Vallières L.et al. Auditory cortex shapes sound responses in the inferior colliculus. Elife. 2020, Jan 31;9:e51890. [CrossRef]

- Flury, A., Aljayousi, L, Park HJ, Khakpour M, Mechler J, Aziz S, McGrath JD, Deme P, Sandberg C, González Ibáñez F, et al. A neurodegenerative cellular stress response linked to dark microglia and toxic lipid secretion. Neuron. 2025 Feb 19;113(4):554-571.e14. [CrossRef]

- St-Pierre, M.K., Bordeleau, M., Tremblay, M.È. Visualizing Dark Microglia. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 2034, 97-110. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).