1. Introduction

Subjective tinnitus is a sound perception that is not related to an acoustic sound source. People suffering from tinnitus typically describe hearing a high-pitched tone or noise, often described as ringing in the ear. However, a wide range of tinnitus sounds has been described. Although tinnitus is often of mild impact, its consequences can be devastating. Tinnitus can lead to depression and anxiety, sleep deprivation and may severely hinder the ability to participate in social activities or work [

1,

2].

Tinnitus is often associated with hearing loss. Plastic changes associated with hearing loss are believed to lead to tinnitus [

3]. Indeed, noise-induced changes to cochlear function in animals lead to central changes in spontaneous neural activity in central auditory structures [

4,

5,

6]. Moreover, tinnitus has been linked to incomplete cortical adaptation to hearing loss [

7], or more generally, as a failure to adapt to hearing loss [

8].

However, tinnitus may also occur in absence of any documented hearing loss. Then, tinnitus does not seem to be associated with changes in the tonotopic map [

9]. One study showed enlarged responses to sound in normal hearing tinnitus subjects compared to controls without tinnitus [

10,

11]. However, Lanting et al., 2014 found no difference in cortical response. In these studies, bilateral stimuli were used. Thus, the responses measured are the net result of simultaneous stimulation of both ears, with the ear ipsilateral to a brain hemisphere probably contributing more to inhibition, while the contralateral ear may contribute to excitation [

12]. Thus far, the bilateral stimuli may have masked effects related to either inhibition or excitation. Therefore, in this study we measured monaural tone-evoked response to assess brain activity in higher details. Also, we used pure tone stimuli of 4 different frequencies to estimate the tonotopic organization of the auditory cortex. We included two high frequency stimuli (6 and 8 kHz), as an earlier study [

7] only detected significant differences between tinnitus and controls for higher frequencies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

Eighteen volunteers (39.8±10.9 years old, 12 males) with subjective continuous tinnitus and twenty healthy volunteers (29.4±8.4 years old, 13 males) were recruited for this investigation. The protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Groningen, all participants gave written informed consent, and the research was conducted in accordance with the principles of the declaration of Helsinki.

Pure-tone thresholds were obtained for both ears at all octave frequencies from 125 Hz to 8000 Hz using a standard audiometry device (AC40). Only participants with pure-tone thresholds below 25dB SPL for all of the tested frequencies were included.

Every participant completed the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory, EHI [

13], Hyperacusis Questionnaire, HQ [

14], and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, HADS [

15]. Participants with tinnitus also filled in the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory, THI [

16], and Tinnitus Functionality Index, TFI [

17]. Additionally, tinnitus subjects adjusted the frequency and loudness of a pure tone such that its pitch and loudness matched that of their tinnitus.

2.2. Acoustic Stimuli

In the MRI scan, participants were monaurally stimulated with pure tones of frequencies 353 Hz, 1000 Hz, 6000 Hz and 8000 Hz. The loudness of the stimuli was matched to that of a 60 dB SPL tone at 1000 Hz. Each stimulus consisted of a train of thirty 100-ms sine waves, including two 10-ms rise-time and fall-time. Each sine wave alternated by a 100-ms silence, forming a 6-seconds sound wave. A 5-percent frequency deviation (randomly chosen) was embedded in either the first or the last 3 seconds of each 6-second sound and participants were instructed to determine if the frequency change is incremental or decremental by pushing one of the two MRI-compatible buttons inside the scanner bore.

2.3. Imaging Paradigm

The MRI data were acquired using a 3-Tesla scanner (MAGNETOM Prisma, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) equipped with a 64-channel phased array head coil. A T1-weighted image (MPRAGE) was acquired for each subject (TR = 2300 ms, TE = 2.98 ms, FoV = 256 mm × 240 mm × 176 mm, 176 slices, 1 mm

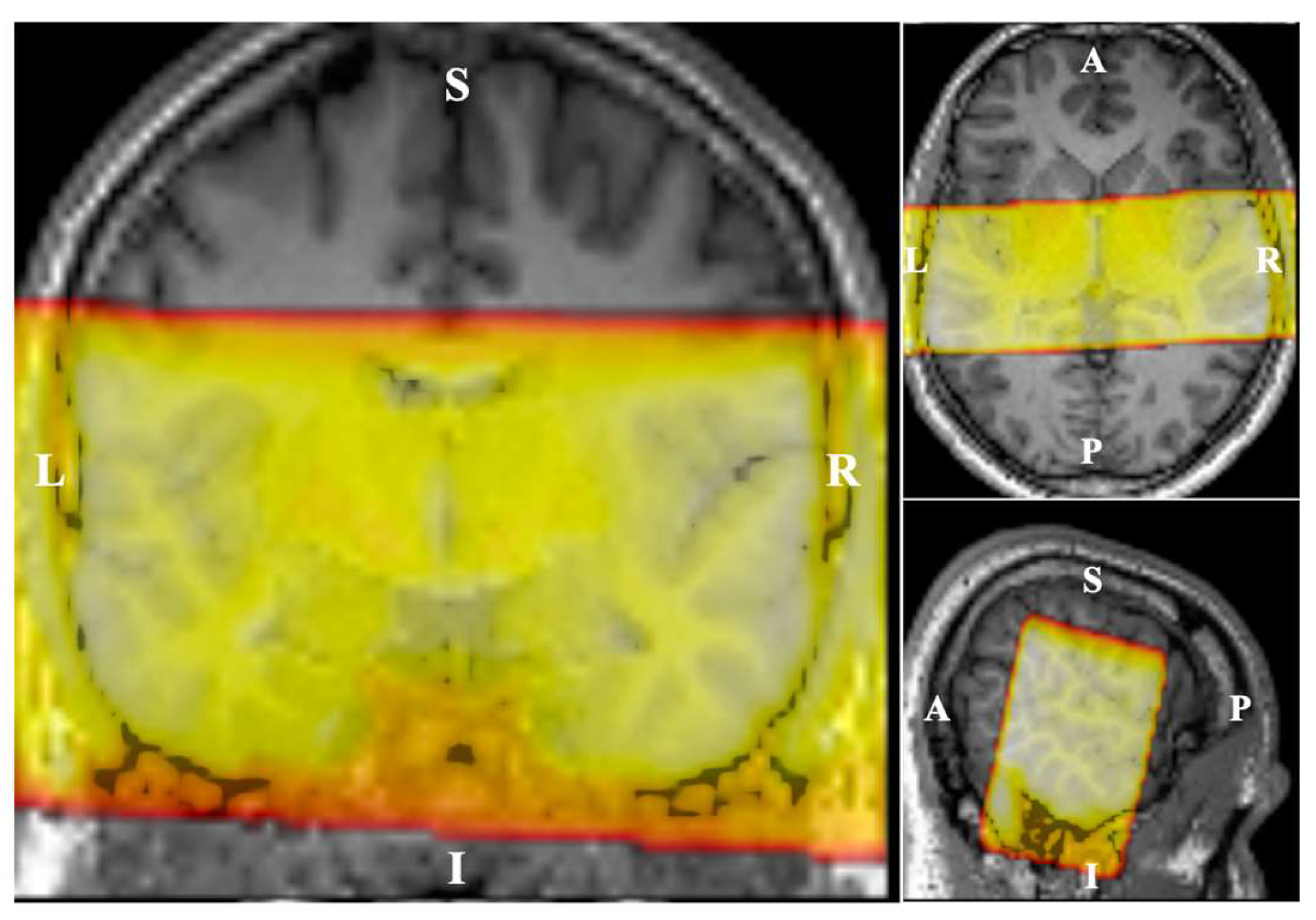

3 isotropic voxel) for anatomical reference. Echo-Planar-Imaging with reduced field of view in two dimensions (Siemens ZOOMit technique,

Figure 1) was used to acquire the functional images (TR = 10s, TA = 2.97s, TE = 30ms, FoV = 192 mm × 84 mm × 176 mm, 29 coronal slices, 2 mm

3 isotropic voxel). A sparse sampling method (6s sound stimulation scanner down) was used to prevent interference of scanner noise on the auditory cortex response [

18]. For each subject, two runs of functional MRI were performed, 127 brain volumes each. Within one run, each frequency was monaurally presented 14 times to each ear. Additionally, a “silence condition” (no sound played) was presented 15 times, randomly distributed across the full run. A single EPI volume with the opposite phase-encoding direction was acquired after each functional run to allow geometric distortion correction. A T2-weighted image (TR = 1000 ms, TE = 127ms, FoV = 192mm × 84mm × 96mm, 96 slices, 1 mm

3 isotropic voxel) with the same FoV as the functional scans was acquired to aid the registration of the functional images to the structural image.

Figure 1.

Field-of-view (FoV) in functional MRI. The fMRI scans were performed coronally with FoV cropped in the superior-inferior direction.

Figure 1.

Field-of-view (FoV) in functional MRI. The fMRI scans were performed coronally with FoV cropped in the superior-inferior direction.

2.4. Data Analysis

We use MATLAB (version 2021a) as the main package for processing the data, accompanied with the SPM12 software package [

19] for image registration and functional analysis.

2.4.1. Pre-Processing

As a first step, the potential geometric distortion in the functional images was corrected using the

Topup feature from the FMRIB Software Library (FSL) toolbox [

20]. The functional volumes were then realigned to the mean volume and registered to the subject’s anatomical image. Then, the functional images were normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) stereotaxic space using the transformation matrix obtained from the anatomical T1 transformation to MNI space. Images were further resampled into a 2 mm × 2 mm × 2 mm isotropic voxel size, and smoothed with an isotropic Gaussian kernel with a full-width-half-maximum of 8 mm. A log transform was applied to the voxel values of the smoothed images to de-emphasize outliers and obtain a symmetrical bell-shaped distribution of the response [

9]. A Generalized Linear Model (GLM) with eight regressors was applied at the subject level to obtain the neural-evoked response for each and every stimulus type (i.e. four frequencies, left and right presentation) versus baseline (silence).

2.4.2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

We employed PCA to retrieve the most significant patterns in our data by reducing the dimensionality, a procedure that has been used to obtain the tonotopical organization of the auditory cortex [

7,

9]. For this purpose, a region of interest (ROI) was generated using a group level GLM that included all voxels showing a significant response to any pure tone relative to baseline (F-test across all conditions, P<0.01 FWE corrected, minimum cluster size k=500). Then, within that ROI, the estimated evoked responses of all subjects for each of the eight conditions were concatenated to form an

n×8 matrix, which was subsequently subjected to PCA, where

n is the product of the number of voxels in the ROI and the number of subjects. In order to compare these components between groups, the first 3 resulting components were then separately fed into another PCA and the loadings on the first two components were compared between groups [

9].

2.4.3. Generalized Linear Model (GLM) Analysis

We further conducted a fully factorial GLM analysis of the data to explore the effect of tinnitus (between subjects’ variable) and its interaction with sound frequency and laterality (within subject’s variables). Thus, the design matrix included two groups (tinnitus/controls), two sides of stimulation (left/right), and four frequencies (353 Hz, 1000 Hz, 6000 Hz and 8000 Hz). The threshold for the statistical parametric maps was set to P=0.001 with a minimum cluster size of 20 voxels [

22].

2.4.4. Effects of Tinnitus Severity and Hyperacusis

To further our understanding of differences in neural evoked response associated with tinnitus, we conducted correlation analyses within the regions showing a significant effect of groups in the GLM (main effect or interaction). The dependent variable was the median evoked response of each participant within these ROIs. The independent variables were the scores on the THI and TFI questionnaires assessing tinnitus burden (tinnitus group only) and the hyperacusis questionnaire assessing hypersensitivity to sounds (across all participants; tinnitus and controls). A Pearson correlation was computed between the evoked response and questionnaire scores.

3. Results

3.1. Groups Description

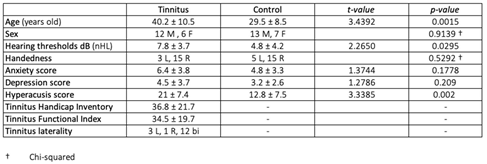

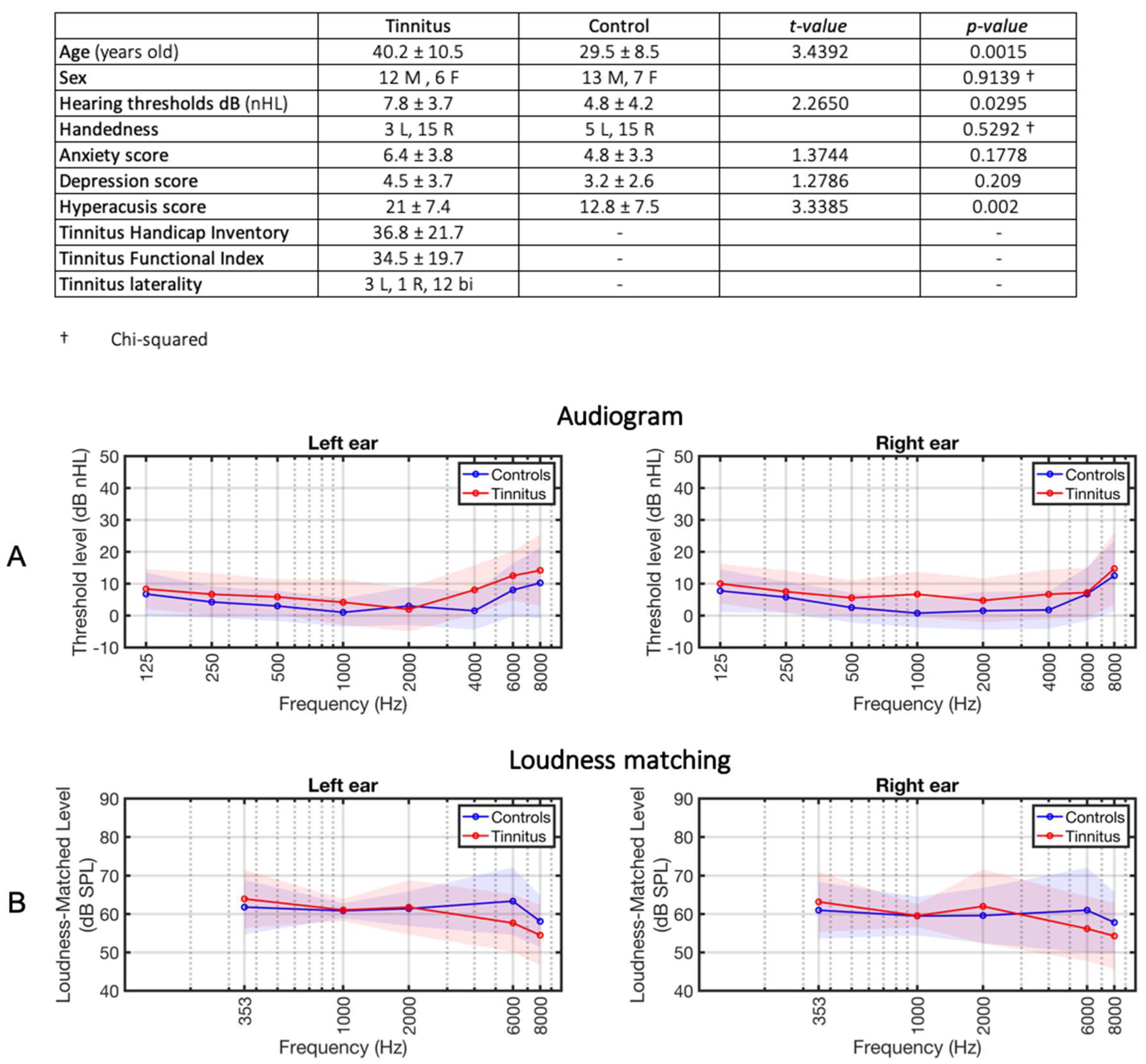

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the subject groups. The average thresholds were 7.8 dB HL and 4.8 dB SPL in the tinnitus and control group, respectively (t=2.26, p=0.029,

Figure 1). The intensities of the loudness matched stimuli, to be used in the MRI experiment, were not different between groups (t=1.32, p=0.18,

Figure 1B).

Table 1.

Subject characteristics. Averages per group were compared using a t-test. The hearing thresholds are measured in the following frequencies: 125, 250, 500, 1000, 2000, 4000, 6000, and 8000 Hz. For sex and handedness, a chi-square test was used to compare the groups (†).

Table 1.

Subject characteristics. Averages per group were compared using a t-test. The hearing thresholds are measured in the following frequencies: 125, 250, 500, 1000, 2000, 4000, 6000, and 8000 Hz. For sex and handedness, a chi-square test was used to compare the groups (†).

Figure 1.

Audiograms and loudness-matching. A) Average hearing thresholds of the tinnitus subjects (depicted in red) and the control subjects (represented in blue). The shading indicates the standard deviation per group. B) Average loudness-matched levels. The loudness of tones at frequencies of 353, 1000, 2000, 6000, and 8000 Hz was matched to 60 dB SPL at 1kHz in a randomly selected ear for each subject. During the fMRI experiments, the individually-matched tones at 353, 1000, 6000, and 8000 Hz were used for stimulation.

Figure 1.

Audiograms and loudness-matching. A) Average hearing thresholds of the tinnitus subjects (depicted in red) and the control subjects (represented in blue). The shading indicates the standard deviation per group. B) Average loudness-matched levels. The loudness of tones at frequencies of 353, 1000, 2000, 6000, and 8000 Hz was matched to 60 dB SPL at 1kHz in a randomly selected ear for each subject. During the fMRI experiments, the individually-matched tones at 353, 1000, 6000, and 8000 Hz were used for stimulation.

The hyperacusis scores were significantly higher in the tinnitus group, as compared to the control group (t=3.33, p=0.002). With a cutoff score equal to HQ=22 [

23], the questionnaire indicates the presence of hyperacusis in 2 controls and 9 participants with tinnitus. As indicated in Table 1, the participants groups did not significantly differ with respect to sex, handedness, and HADS score (anxiety and depression). The THI and TFI indicate on average a moderate tinnitus burden in the tinnitus group. The scores on the HQ, THI, and TFI questionnaires were highly correlated within the tinnitus group (see Supplementary

Figure 1).

3.2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

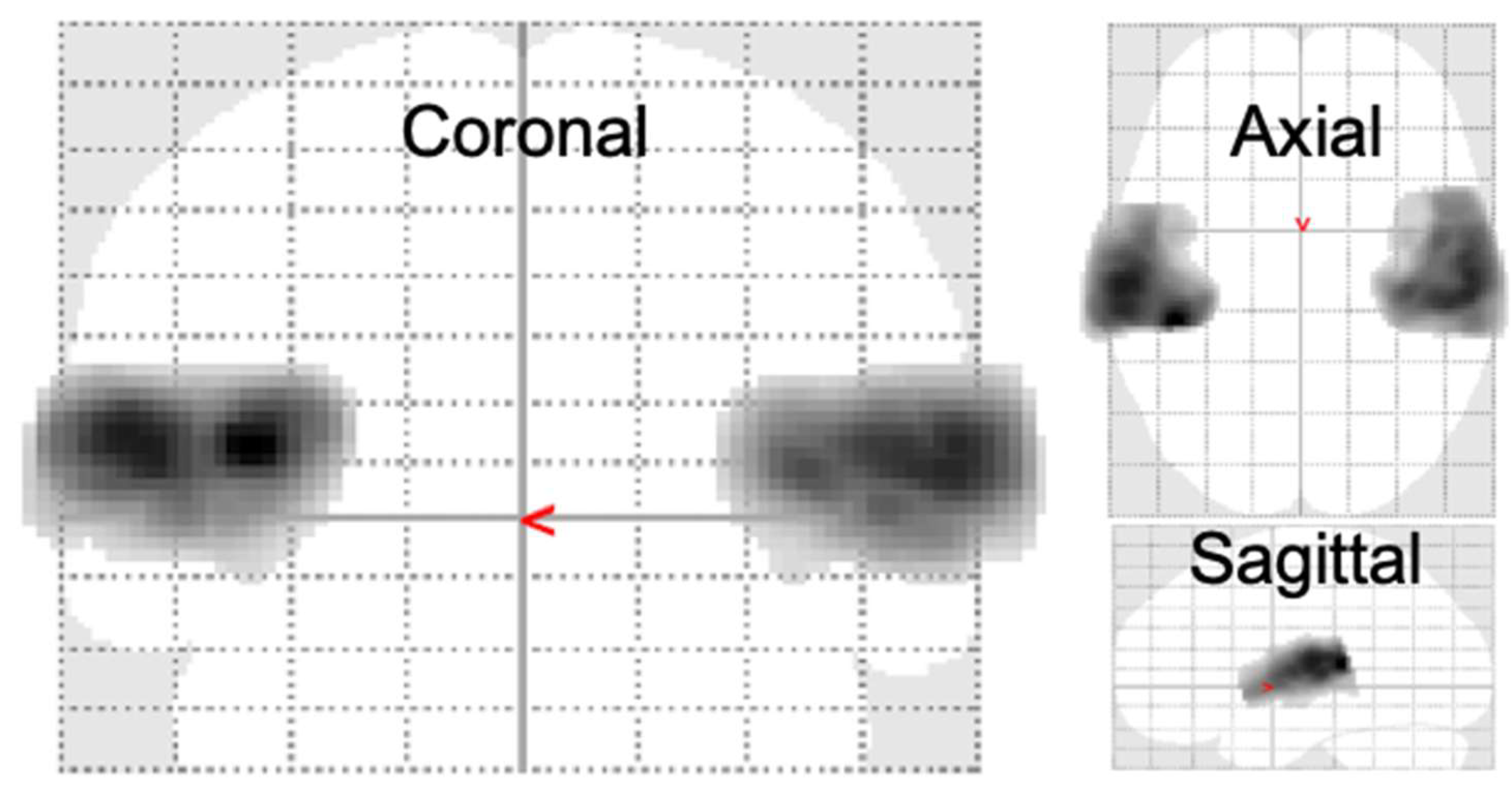

The acoustic stimuli significantly activated a total of 9109 voxels in the left and right auditory cortices

(p<0.01, FWE corrected, Figure 3).

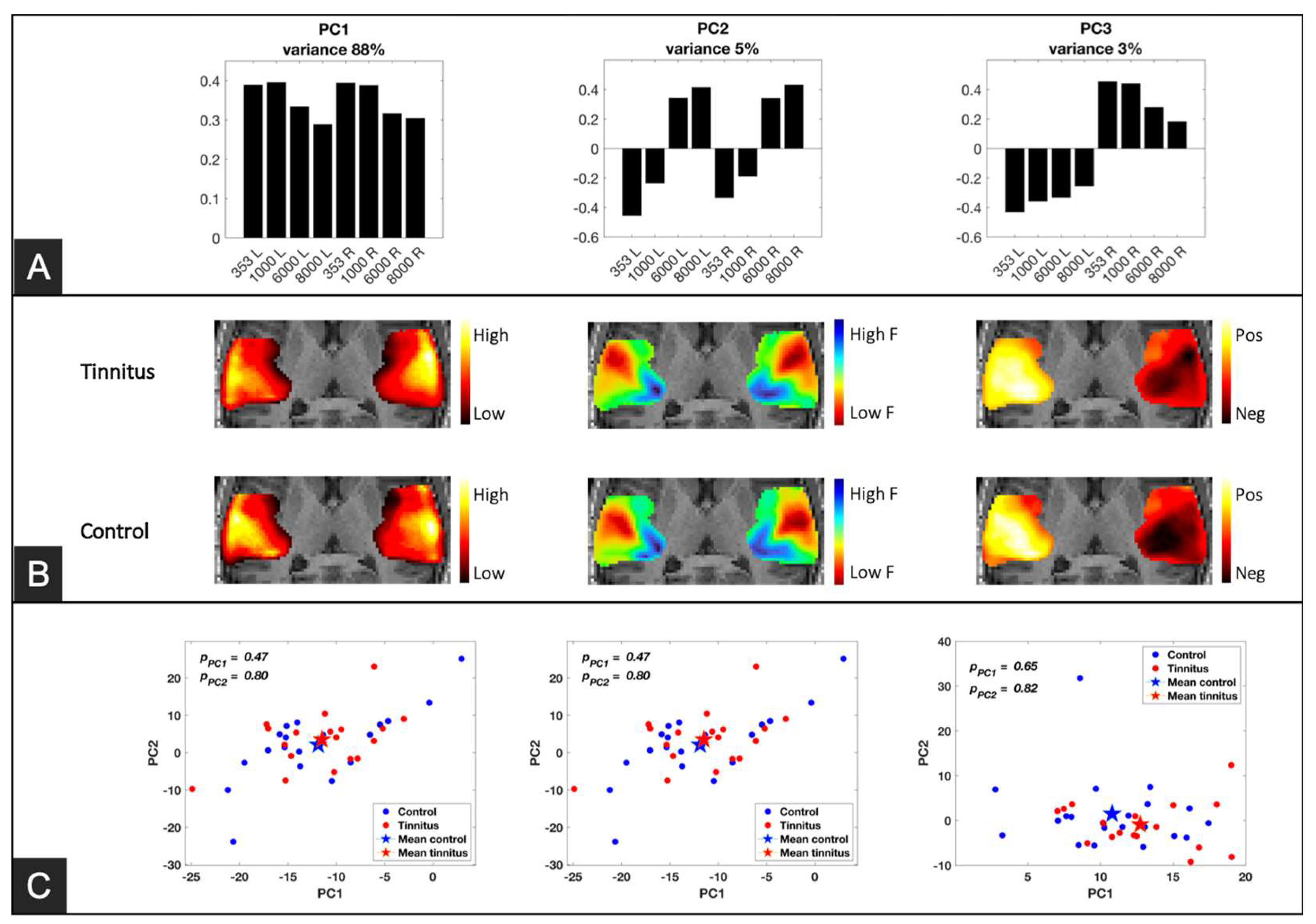

In the selected region of interest (ROI) representing the auditory cortex, the first three principal components, each corresponded to a distinct aspect of the auditory stimuli (

Figure 4). The first component (PC1), accounting for 89% of the total variance, depicted an overall neural response profile to any auditory stimuli, Loadings on that component were relatively higher for low compared to high frequency stimuli. The second component (PC2), explaining 5% variance, showed a clear staircase profile reflecting the differential neural response to sound frequency. On that component, low frequency pure tones had negative loadings and high frequency pure tones had positive loadings irrespective of the stimulated ear. The third component (PC3) classified the laterality of the presented sounds, whereby loadings for left-ear stimulation had a negative sign and those for right-ear stimulation had positive signs.

Figure 4A displays the loading profile of the first three principal components.

The loadings on PC1-3 of each subject were back-projected into the 3D ROI to generate a response map for each group. Results are depicted on

Figure 4 with separate maps for the two groups. The maps for the first component (average response) showed relatively high values in the lateral side of the auditory cortex. These lateral regions are known to encode lower frequencies, and this is reflected in PC-1 profile showing higher loadings for lower frequencies. The maps of the second component (separating frequencies) showed a typical tonotopic organization of the auditory cortices where neurons in the posteromedial side of the Heschl’s gyrus are dominantly responsive to high-frequency sounds with a gradual V-shape gradient toward the anterolateral side. The maps of the third component (distinguishing the stimulated ear) indicated a clear controlaterality between stimulation side and cortical activity.

To compare the maps between the groups, we performed another principal component analysis on the maps of each component from the first PCA results (i.e., PC1, PC2, and PC3). The analysis represents the response maps of each subject by just three scores (

Figure 4C). This analysis did not show any difference between the means of differences of the scores between the groups.

3.3. Full Factorial GLM Analysis

To further explore potential differences between groups, a full-factorial GLM was conducted including group as between subject variable, as well as tone frequency and stimulation side as within subject variables. We looked for main effects of group (tinnitus vs. controls), as well as interactions between group and frequency or side of stimulation on the auditory cortex sound-evoked response within the field of view (

Figure 1). Statistical maps were thresholded at the voxel level (p<0.001 uncorrected) with a minimum cluster size of 20 voxels.

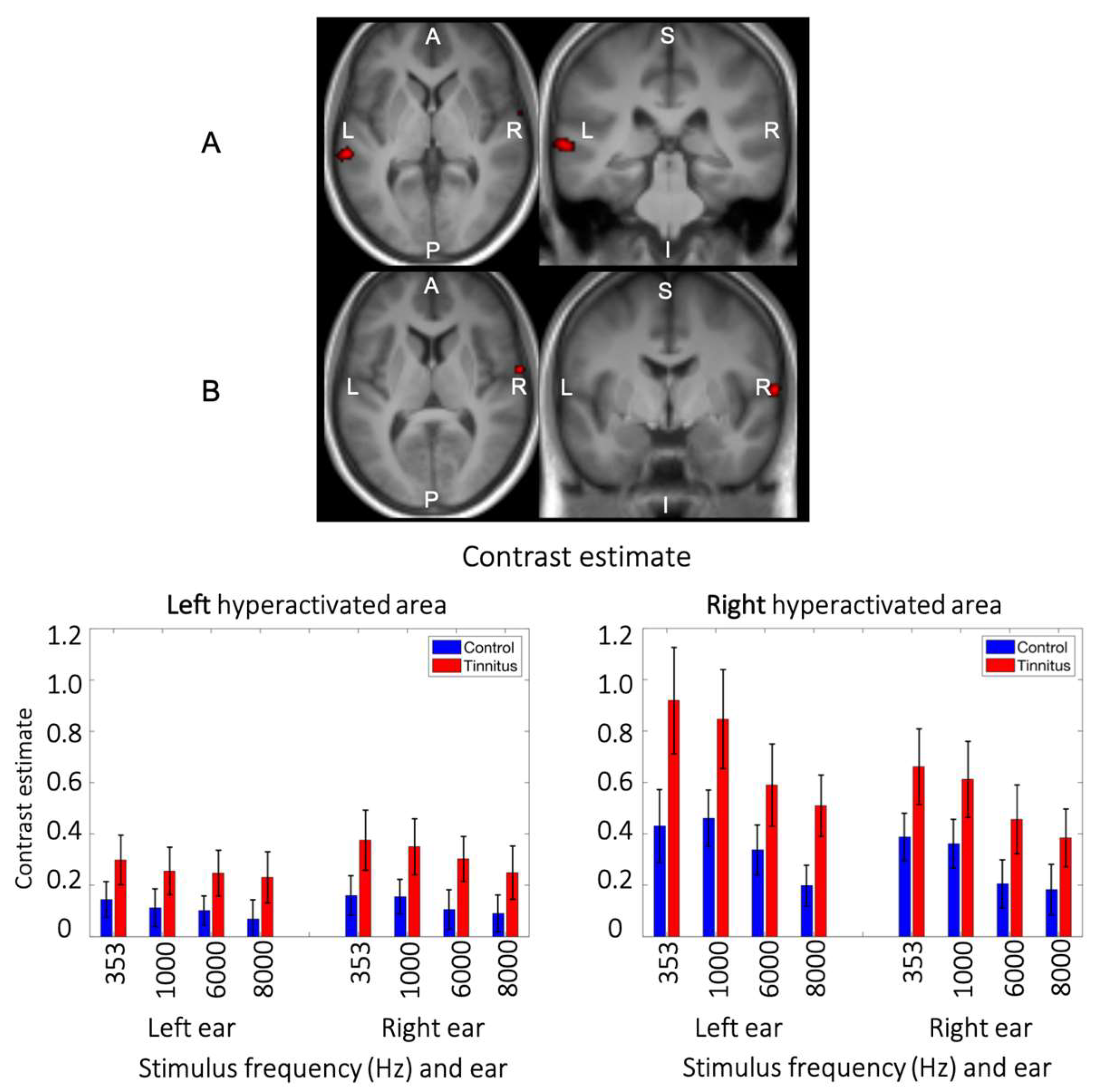

3.4. Main Effect of Group

A main effect of group was found in two regions of the lateral auditory cortices. The first cluster (55 voxels, MNI peak coordinate -62, -30, 2, F

1,288 = 16.86) was located in the left posterior superior temporal gyrus/superior temporal sulcus (

Figure 4A). The second cluster (29 voxels, peak coordinate 64, -4, 8, F

1,288 = 15.92) was located more anteriorly in the right superior temporal gyrus / Heschl’s gyrus with some voxels in the Rolandic operculum (

Figure 4B). In both regions, participants with tinnitus showed higher evoked auditory response compared to controls irrespective of pure tone frequency and stimulated ear (

Figure 4). The plots of the contrast estimates across all conditions also show a clear staircase profile whereby in these two lateral auditory regions, lower frequencies evoked higher responses than higher ones, in accordance with the tonotopic organization of the auditory cortex (

Figure 4).

We further tested for correlations between brain evoked responses and scores on questionnaires of tinnitus burden (THI, TFI) and hyperacusis (HQ) within these two auditory brain regions showing significant main effects of group (Supplementary

Figure 2). In the tinnitus group, tinnitus burden (THI or TFI) scores were positively associated with the median sound-evoked response for the lowest frequency (353 Hz) only, and more so in the right hemisphere following left ear stimulation. Similarly, for the hyperacusis scores, a positive correlation with the median evoked response was found solely for the 353Hz stimulation in the right hemisphere following left ear stimulation in the tinnitus group.

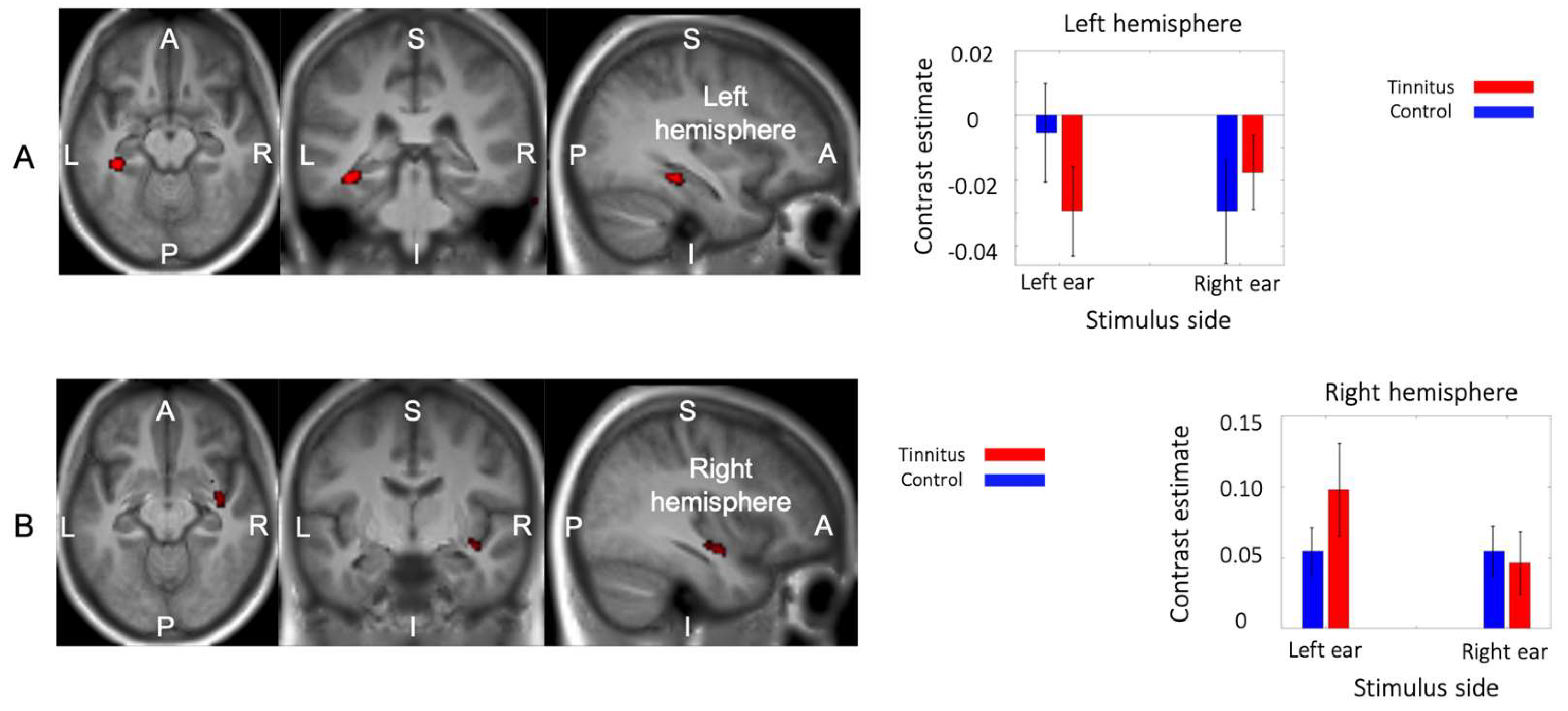

3.5. Interaction between Group and Side of Stimualtion

An interaction between group and the stimulated ear was found in two regions. The first cluster (59 voxels, MNI peak coordinate -36, -34, -14, F

1,288 = 20.2) was located in the left parahippocampal region with a peak in the collateral sulcus in-between the parahippocampal and fusiform gyri (

Figure 5A). This cluster included 7 voxels in the hippocampus proper. The second cluster (34 voxels, MNI peak coordinate 38, -8, -12, F

1,288 = 13.22) was found in the right superior temporal gyrus at the vicinity of the lateral fissure and the insular cortex (

Figure 5B).

The contrast estimates of the two groups for the two stimulated ears are also shown in

Figure 5. In the left parahippocampal region, the control group showed decreased activity relative to baseline following right but not left ear stimulation. Participants with tinnitus in contrast showed decreased activity during sound presentation irrespective of the stimulated ear. In the right superior temporal cluster, sound presentation was associated with increased BOLD response for both groups and both stimulation sides, but in the tinnitus group the response was higher following contralateral (left ear) stimulation.

3.6. Triple Interaction: Group × Stimulation Side × Frequency

There was no significant interaction between group and sound frequency, however there was a significant triple interaction between group, frequency and stimulation side (

Figure 6). The cluster (41 voxels, MNI peak coordinate 56, -4, 18, F

3,288 = 7.64) was found in the inferior part of the Rolandic fissure (pre- and postcentral gyri).

The plot of the contrast estimates for the 8 conditions and the two groups (

Figure 6) shows that in the control group, this Rolandic region was significantly active relative to baseline for all conditions and displayed a relatively strong response to low frequency (353Hz) stimuli presented to the right ear. In the tinnitus group in contrast, this region was not active above baseline in most of the conditions with an exception for 4kHz stimuli presented to the right ear and 353Hz stimuli presented to the left ear.

4. Discussion

This study sought to examine differences in sound-evoked brain response associated with tinnitus in individuals with clinically normal hearing levels. To this effect, tinnitus and control participants were monaurally stimulated with pure tones of four different frequencies. We first applied a principal component analysis (PCA) to the data in order to retrieve the tonotopic organization of the auditory cortex in both groups [

24]. Three components accounted for most of the variance in the signal. The first component showed positive loadings for all conditions (especially for low frequencies, 353Hz and 1kHz). The second component revealed the tonotopic organization of the auditory cortex. The third component reflected the side of stimulation (left or right ear). In agreement with one previous research ([

9], we found no significant difference in terms of tonotopic organization of the auditory cortices in these participants with tinnitus and no hearing loss, at least at a macroscopic level. Furthermore, both groups (tinnitus and controls) showed a typical pattern of higher cerebral activity contralateral to the stimulated ear [

11,

25]. These results support the idea that hearing loss, not tinnitus, is the main factor driving functional and neuroanatomical changes in the auditory cortex [

3,

7,

26].

Although PCA can provide a data-driven picture of the auditory cortex behavior, comparing the maps between groups is challenging. For instance, higher loadings for the first component in the right lateral auditory cortex of participants with tinnitus was not captured by our between-group analysis. Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) was therefore, used to fit a full-factorial model to the data at the voxel level, testing for the effect of group, and its interactions with side of stimulation, and tone frequency. This analysis revealed a significant main effect of group in two regions of the lateral auditory cortices (left superior temporal gyrus and right Heschl’s gyrus). Participants with tinnitus showed higher sound-evoked response relative to controls in both regions. These lateral areas also displayed relatively higher response for sound of lower frequencies in accordance with the tonotopic mapping. Interestingly, the sound-evoked response in these two regions was correlated with tinnitus burden and hyperacusis scores, but only for low frequencies. Because hyperacusis (hyper-sensitivity to sounds of mild or moderate intensity) is highly correlated to tinnitus burden in our group, it is however not possible to disentangle the contribution of these two factors.

Hyperacusis in tinnitus patients is associated with enhanced cortical response to both low- and high-frequency stimuli [

27]. In contrast, effects of tinnitus are only present in response to high-frequency tones and primarily in high-frequency portions of the auditory cortex [

7]. Together, this suggests that hyperacusis is associated with pathological response across the frequencies and therefore across the tonotopic map, while the pathology of tinnitus appears to be more localized in high-frequency cortical areas. This corresponds to the pitch of tinnitus which typically corresponds to that of a high-frequency tone. If indeed hyperacusis is associated with pathology across the tonotopic map, the hyperactivity in the lateral portion of Heschl’s gyrus [

9] is likely associated with hyperacusis rather than tinnitus.

Our analysis also revealed an interaction between groups and side of stimulation in the parahippocampal cortex. In control subjects, the left parahippocampus showed inhibition in response to sounds presented to the contralateral but not the ipsilateral ear. In participants with tinnitus the same region was below baseline for both left and right ear stimulation. In other words, left-ear stimulation stood out as deviant from other stimulation conditions between groups. The parahippocampus has been associated with tinnitus, primarily in resting-state studies. In tinnitus, beta and gamma band activity is enhanced [

28], and functional connectivity is increased between the parahippocampal cortex and the auditory cortex [

29] or more generally with the auditory resting state network [

30]. The parahippocampus was not reported in functional MRI studies that studied sound-evoked response. Here however, we could show an interaction with the side of stimulation due to our design with monaural stimuli. The parahippocampus is involved in memory retrieval, and it has been suggested that dysfunctional gating of perceptual memory may result in a phantom percept, that is, tinnitus [

31]. It seems however unlikely that the high-pitched tonal percept of which tinnitus often consists is based on retrieval from memory. On the basis of our results, we confirm a role of the parahippocampus in tinnitus, but cannot provide support for the hypothesis that this role concerns sound memory retrieval. Indeed, our participants with normal hearing thresholds do not need to fill-out a gap in the high frequency band. Our results instead seem to suggest an important effect of laterality of sound presentation, which could be related to tinnitus sound localization in a map of the environment or an interference between tinnitus and spatial sound perception [

32].

Finally, a triple interaction was found in the right inferior central sulcus, a motor area associated with tongue and lip movements [

33]. Control participants showed a positive activity relative to baseline in this region, with a high response for low frequency pure tones, in sharp contrast with tinnitus participants who only showed a significant response for high frequencies presented to the right (ipsilateral) ear.

We found no interaction between group and pure tone frequency, therefore confirming the normal tonotopic organization of the auditory cortex in patients with tinnitus and normal hearing thresholds.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, in individuals with tinnitus and clinically normal hearing levels (<25dB SPL for all frequencies up to 8kHz), the tonotopical organization of the auditory cortices seems to be preserved. However, these individuals showed elevated sound-evoked responses in two lateral auditory regions. This hyper-activity could be related to hyperacusis rather than tinnitus, but further studies will be needed to clarify the difference between hyperacusis and tinnitus burden on these group effects. Furthermore, we found an effect of the laterality of sound presentation on parahippocampal activity as a function of group. The parahippocampal gyrus has been often associated with tinnitus in resting state studies. Here we demonstrate that this region, involved in memory but also spatial navigation, distinguishes between groups following left ear stimulation, in normal hearing participants.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

Preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.D.; methodology, S.S., M.T., R.J.R. and, P.D; software, S.S.; validation, S.S., M.T. and, P.D.; formal analysis, S.S.; investigation, S.S., M.T. and, P.D; resources, P.D.; data curation, S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; writing—review and editing, S.S., M.T. and, P.D; visualization, S.S., M.T. and, P.D; supervision, M.T., P.D.; project administration, P.D.; funding acquisition, P.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (Grant agreement number 76604, TINACT), the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMW, project 91218033), the American Tinnitus Association under the Innovative Grants Research Program 2021 and the Dorhout Mees Family Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of University Medical Center Groningen (2021/543, 07-02-2021).” for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no competing interest.

References

- Baguley, D., McFerran, D., Hall, D.: Tinnitus. The Lancet. 382, 1600–1607 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Langguth, B., de Ridder, D., Schlee, W., Kleinjung, T.: Tinnitus: Clinical Insights in Its Pathophysiology-A Perspective. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology. (2024). [CrossRef]

- Husain, F.T., Medina, R.E., Davis, C.W., Szymko-Bennett, Y., Simonyan, K., Pajor, N.M., Horwitz, B.: Neuroanatomical changes due to hearing loss and chronic tinnitus: A combined VBM and DTI study. Brain Res. 1369, 74–88 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Noreña, A.J., Eggermont, J.J.: Changes in spontaneous neural activity immediately after an acoustic trauma: implications for neural correlates of tinnitus. Hear Res. 183, 137–153 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.S., Kaltenbach, J.A.: Increases in spontaneous activity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus of the rat following exposure to high-intensity sound. Neurosci Lett. 250, 197–200 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Bauer, C.A., Turner, J.G., Caspary, D.M., Myers, K.S., Brozoski, T.J.: Tinnitus and inferior colliculus activity in chinchillas related to three distinct patterns of cochlear trauma. J Neurosci Res. 86, 2564–2578 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Koops, E.A., Renken, R.J., Lanting, C.P., van Dijk, P.: Cortical Tonotopic Map Changes in Humans Are Larger in Hearing Loss Than in Additional Tinnitus. The Journal of Neuroscience. 40, 3178–3185 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Knipper, M., Van Dijk, P., Nunes, I., Rüttiger, L., Zimmermann, U.: Advances in the neurobiology of hearing disorders: Recent developments regarding the basis of tinnitus and hyperacusis. Prog Neurobiol. 111, 17–33 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Langers, D.R.M., Kleine, E. de, Dijk, P. van: Tinnitus does not require macroscopic tonotopic map reorganization. Front Syst Neurosci. 6, (2012). [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.W., Halpin, C.F., Nam, E.-C., Levine, R.A., Melcher, J.R.: Tinnitus, Diminished Sound-Level Tolerance, and Elevated Auditory Activity in Humans With Clinically Normal Hearing Sensitivity. J Neurophysiol. 104, 3361–3370 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Melcher, J.R., Levine, R.A., Bergevin, C., Norris, B.: The auditory midbrain of people with tinnitus: Abnormal sound-evoked activity revisited. Hear Res. 257, 63–74 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Gutschalk, A., Steinmann, I.: Stimulus dependence of contralateral dominance in human auditory cortex. Hum Brain Mapp. 36, 883–896 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Oldfield, R.C.: The assessment and analysis of handedness: The Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 9, 97–113 (1971). [CrossRef]

- Khalfa, S., Dubal, S., Veuillet, E., Perez-Diaz, F., Jouvent, R., Collet, L.: Psychometric Normalization of a Hyperacusis Questionnaire. ORL. 64, 436–442 (2002). [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A.S., Snaith, R.P.: The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 67, 361–370 (1983). [CrossRef]

- Newman, C.W., Jacobson, G.P., Spitzer, J.B.: Development of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Archives of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 122, 143–148 (1996). [CrossRef]

- Meikle, M.B., Henry, J.A., Griest, S.E., Stewart, B.J., Abrams, H.B., McArdle, R., Myers, P.J., Newman, C.W., Sandridge, S., Turk, D.C., Folmer, R.L., Frederick, E.J., House, J.W., Jacobson, G.P., Kinney, S.E., Martin, W.H., Nagler, S.M., Reich, G.E., Searchfield, G., Sweetow, R., Vernon, J.A.: The Tinnitus Functional Index. Ear Hear. 33, 153–176 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.A., Haggard, M.P., Akeroyd, M.A., Palmer, A.R., Summerfield, A.Q., Elliott, M.R., Gurney, E.M., Bowtell, R.W.: ?sparse? temporal sampling in auditory fMRI. Hum Brain Mapp. 7, 213–223 (1999). [CrossRef]

- Friston, K.J.: Statistical Parametric Mapping. In: Neuroscience Databases. pp. 237–250. Springer US, Boston, MA (2003).

- Andersson, J.L.R., Skare, S., Ashburner, J.: How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin-echo echo-planar images: application to diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage. 20, 870–888 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Goodpaster, A.M., Kennedy, M.A.: Quantification and statistical significance analysis of group separation in NMR-based metabonomics studies. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems. 109, 162–170 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Thirion, B., Pinel, P., Mériaux, S., Roche, A., Dehaene, S., Poline, J.-B.: Analysis of a large fMRI cohort: Statistical and methodological issues for group analyses. Neuroimage. 35, 105–120 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Aazh, H., Moore, B.C.J.: Factors related to uncomfortable loudness levels for patients seen in a tinnitus and hyperacusis clinic. Int J Audiol. 56, 793–800 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Langers, D.R.M., van Dijk, P.: Mapping the Tonotopic Organization in Human Auditory Cortex with Minimally Salient Acoustic Stimulation. Cerebral Cortex. 22, 2024–2038 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Lanting, C.P., de Kleine, E., van Dijk, P.: Neural activity underlying tinnitus generation: Results from PET and fMRI. Hear Res. 255, 1–13 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Makani, P., Thioux, M., Pyott, S.J., van Dijk, P.: A Combined Image- and Coordinate-Based Meta-Analysis of Whole-Brain Voxel-Based Morphometry Studies Investigating Subjective Tinnitus. Brain Sci. 12, 1192 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Koops, E.A., van Dijk, P.: Hyperacusis in tinnitus patients relates to enlarged subcortical and cortical responses to sound except at the tinnitus frequency. Hear Res. 401, 108158 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Vanneste, S., Plazier, M., van der Loo, E., Van de Heyning, P., De Ridder, D.: The difference between uni- and bilateral auditory phantom percept. Clinical Neurophysiology. 122, 578–587 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Maudoux, A., Lefebvre, P., Cabay, J.-E., Demertzi, A., Vanhaudenhuyse, A., Laureys, S., Soddu, A.: Auditory Resting-State Network Connectivity in Tinnitus: A Functional MRI Study. PLoS One. 7, e36222 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.A., Akrofi, K., Carpenter-Thompson, J.R., Husain, F.T.: Default Mode, Dorsal Attention and Auditory Resting State Networks Exhibit Differential Functional Connectivity in Tinnitus and Hearing Loss. PLoS One. 8, e76488 (2013). [CrossRef]

- De Ridder, D., Vanneste, S., Weisz, N., Londero, A., Schlee, W., Elgoyhen, A.B., Langguth, B.: An integrative model of auditory phantom perception: Tinnitus as a unified percept of interacting separable subnetworks. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 44, 16–32 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.W., Wang, B., Chen, B., Galvin, J.J., Fu, Q.-J.: Tinnitus impairs segregation of competing speech in normal-hearing listeners. Sci Rep. 10, 19851 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Grabski, K., Lamalle, L., Vilain, C., Schwartz, J., Vallée, N., Tropres, I., Baciu, M., Le Bas, J., Sato, M.: Functional MRI assessment of orofacial articulators: Neural correlates of lip, jaw, larynx, and tongue movements. Hum Brain Mapp. 33, 2306–2321 (2012). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).