Submitted:

20 May 2025

Posted:

20 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

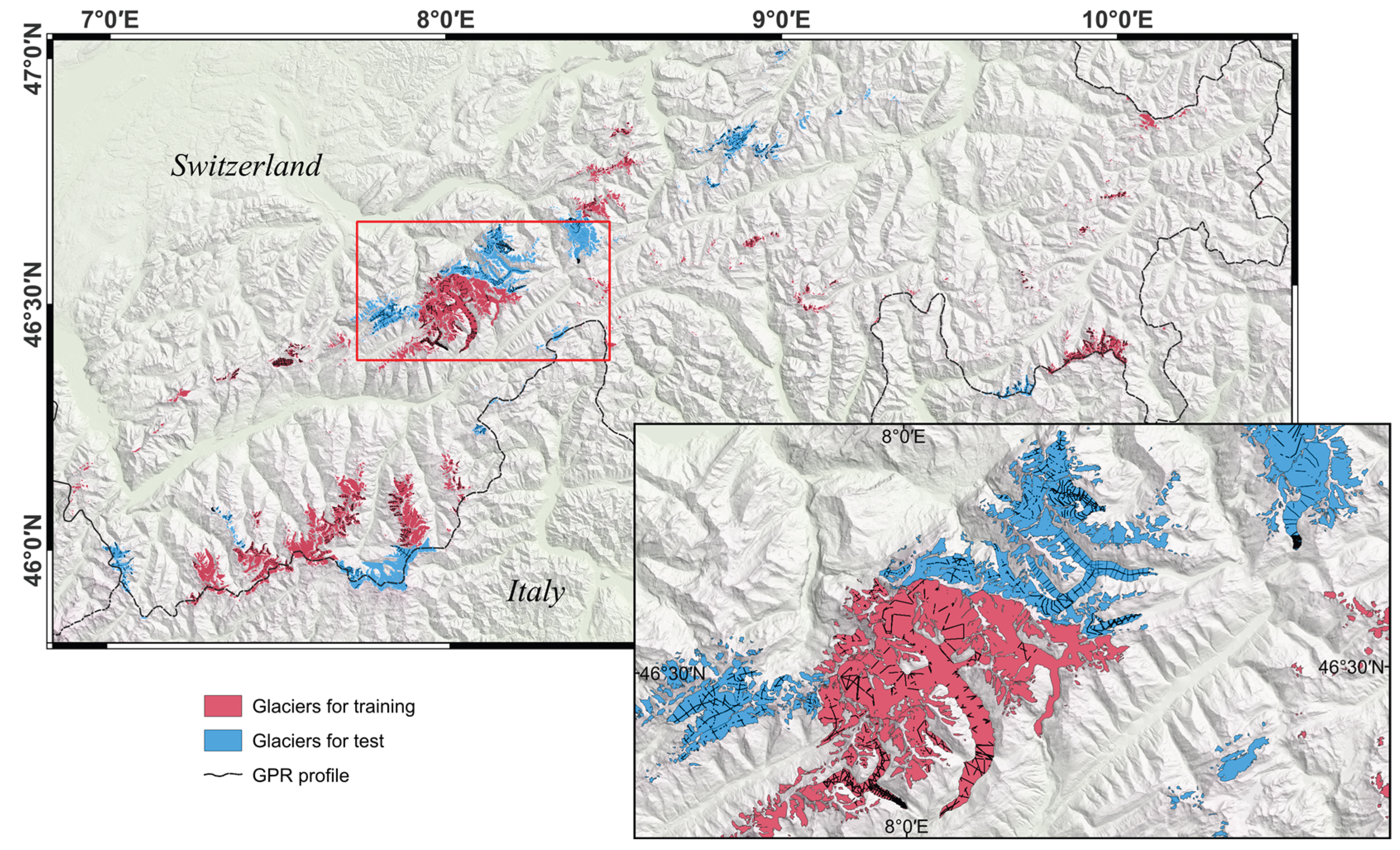

2. Study Area and Data

2.1. Overview of Glaciers in Switzerland and High Mountain Asia

2.2. Data

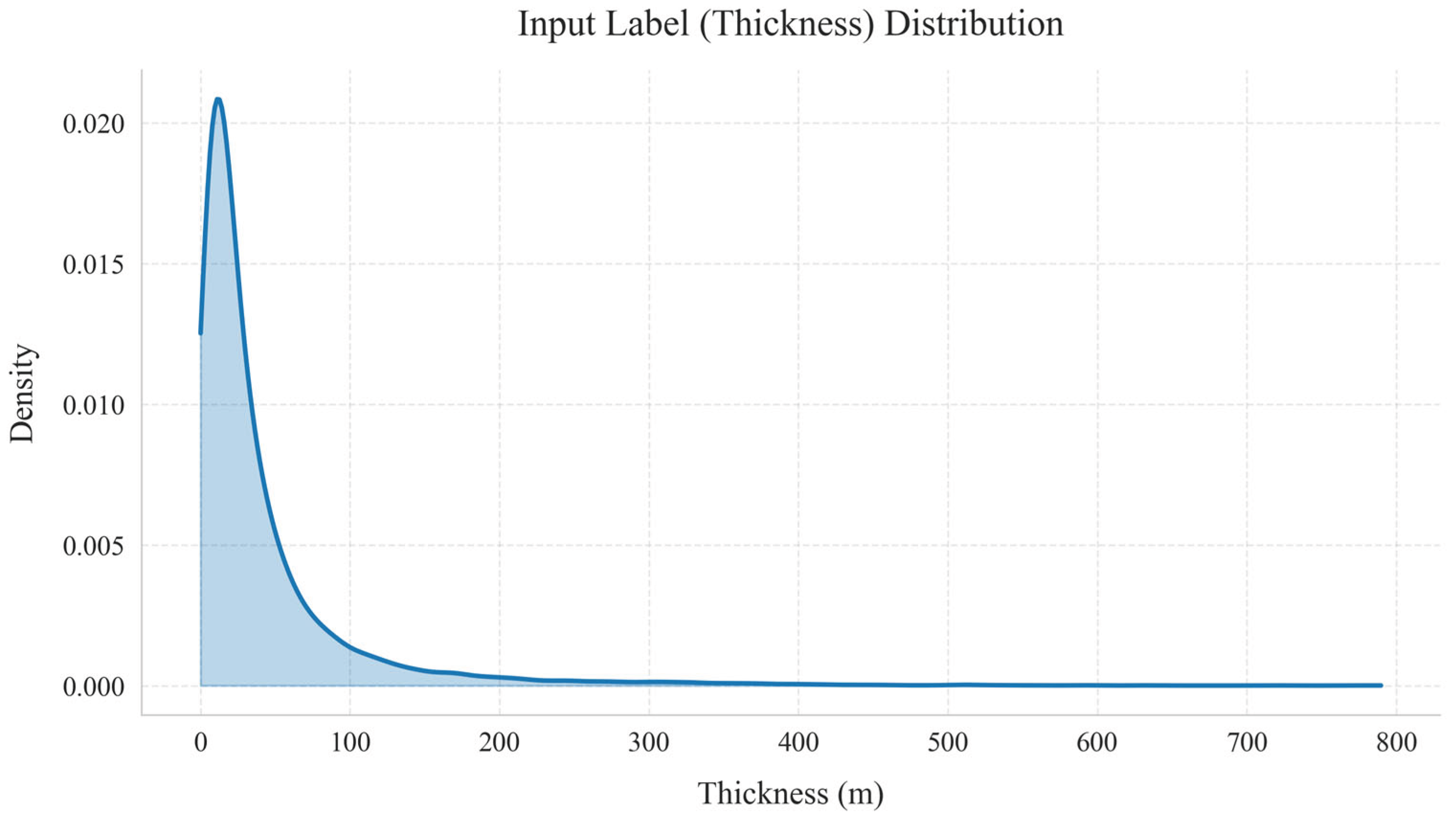

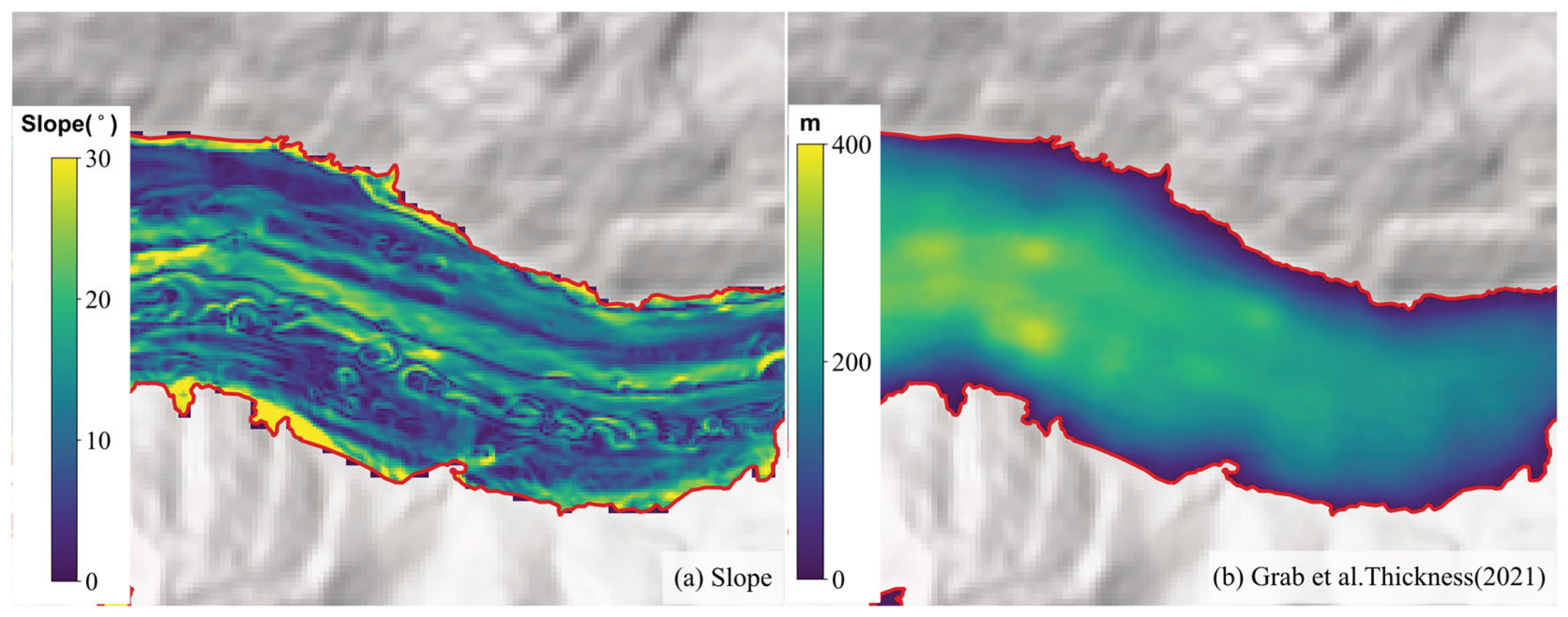

- Ice Thickness: we utilized the 10 m resolution ice thickness distribution data in the Swiss Glacier region presented by Grab et al. (2021) as the baseline thickness data. This dataset is generated by combining measured data with two glacier modeling methods (GlaTE [25,22] and ITVEO [6]). Their approach, benefited from the combination between in situ measurements and models, could reduce interpolation errors and improved the robustness of the ice thickness results. Thanks to the large volume of measured data, the uncertainty of the obtained ice thickness distribution is lower compared to previous studies. This study uses these ice thickness results to train the neural network;

- Glacier Surface Velocity: The ice deformation, one of the two components of ice flow, is mainly controlled by shear stress, which varies with depth and is strongly related to ice thickness. Glacier velocity is a key parameter in physical models used to estimate ice thickness. The surface velocity data used in this study is generated from Millan et al. [26], which is represented by the vectors in east-west and north-south directions. These velocity products were obtained by matching Landsat 8, Sentinel-2, and Sentinel-1 images acquired between 2017 and 2018. The velocity resolution is 50m, with an accuracy of approximately 10 m/a;

- Ice Surface Slope: Ice surface slope is influenced to some extent by the underlying topography, affects the glacier's internal shear stress, and serves as a key parameter in physical models used to estimate glacier ice thickness. Slope is calculated based on the SwissALTI3D DEM. The SwissALTI3D DEM is a digital elevation model (DEM) created using photogrammetric techniques, with a spatial resolution of 2 m. The vertical accuracy is approximately 0.5 m for areas below 2000 m, and between 1 and 3m for areas above 2000 m [27]. The DEM data is updated every 6 years, with the version used in this study being released in 2019 [27];

- Hypsometry: The median glacier elevation can serve as an approximation of the equilibrium line altitude [28]. We used the hypsometry of glaciers as an input parameter for network learning [16]. The elevation value at each surface point is normalized as the proportion of the glacier area (or number of points) below that elevation relative to the total glacier area (or total points), resulting in a normalized distribution from the lowest point (0) to the highest point (1). For stable glaciers, the “contour line” at a value of 0.5 divides the glacier into two equal-area parts, which can coincide with the equilibrium line altitude. The incoporation of hypsometry can help mitigate ice thickness underestimation and reduces the standard deviation of training [16];

- Distance to Boundary: The profiles of most valley glaciers are "U"-shaped, with glacier ice thickness gradually increasing from the edge to the center flow lines [29]. Thus, ice thickness is typically correlated with the distance to the boundary. This study incorporates the minimum distance of selected point to the boundary as an input parameter for the training model.

2.3. Training and Test Datasets Generation

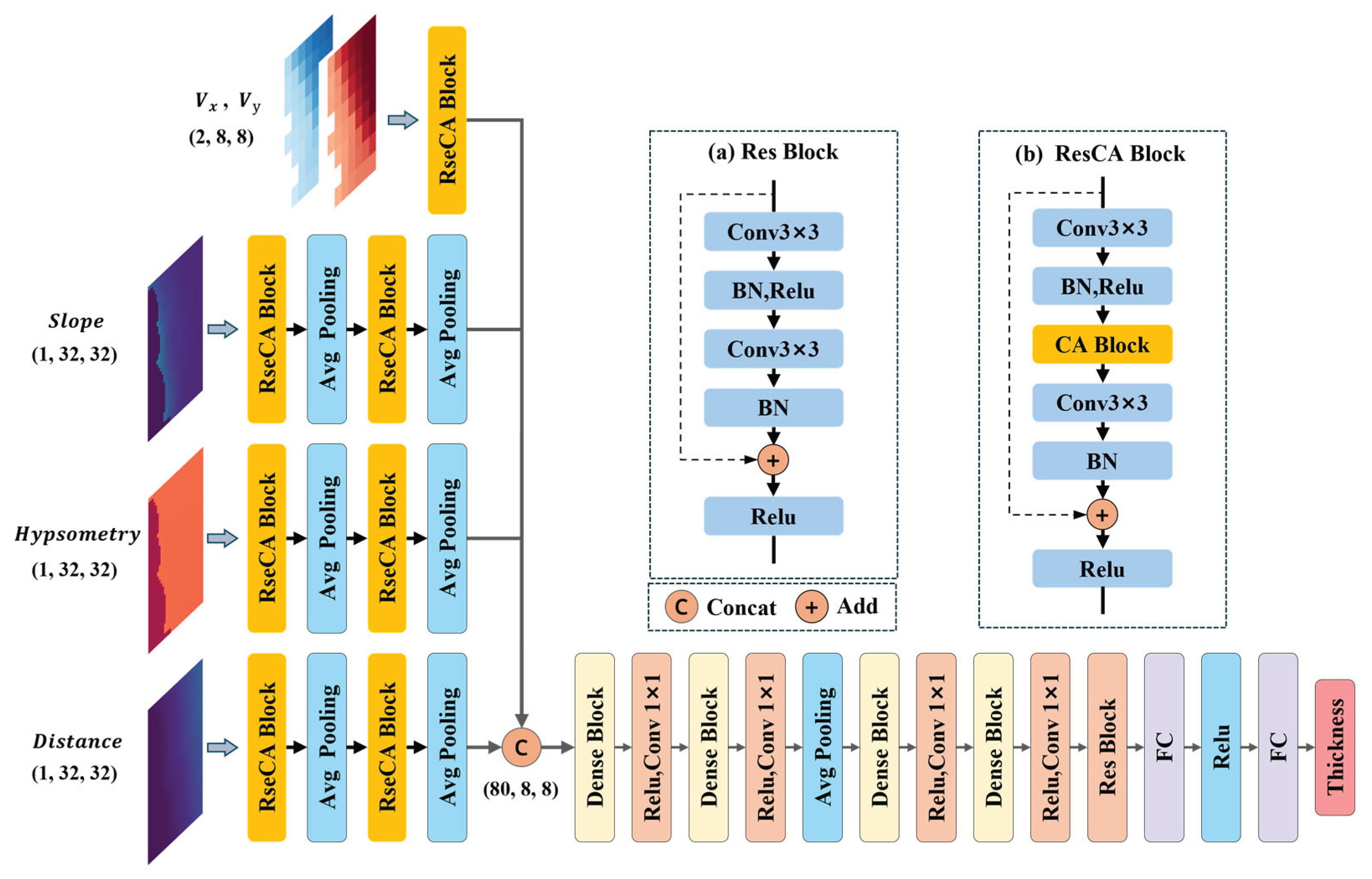

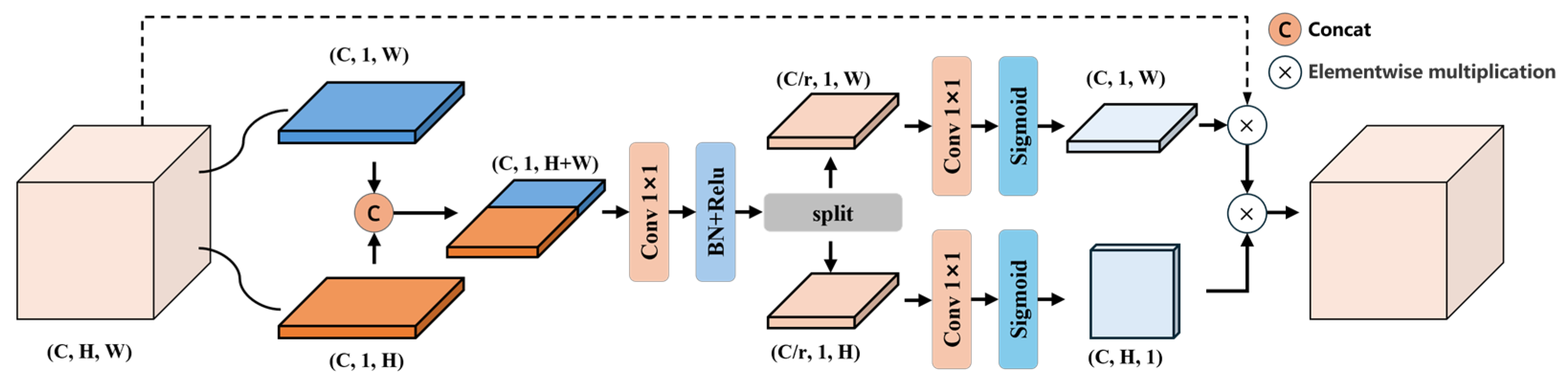

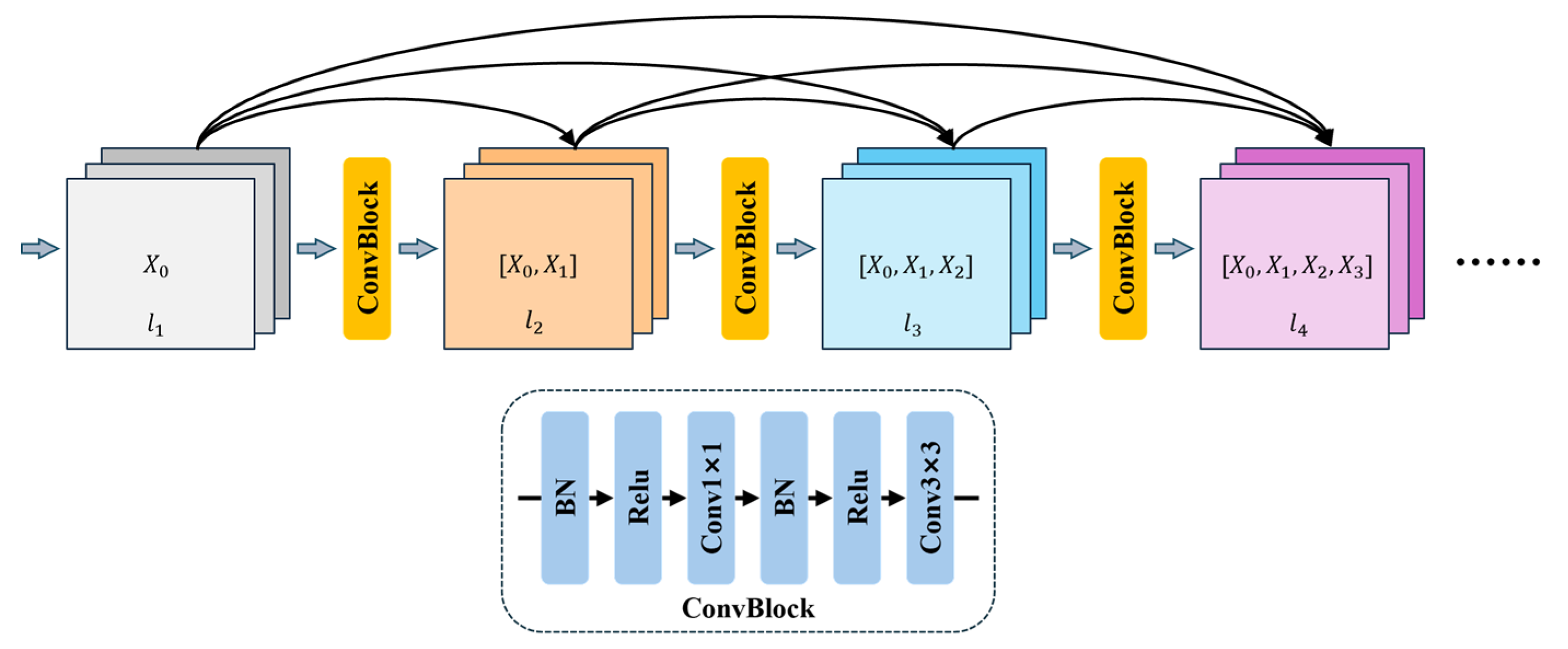

3. Estimation Method

3.1. Convolutional Neural Network Architecture

3.2. Training and Metrics

4. Result

4.1. Model Performance: Glacier Ice Thickness Estimation in Switzerland

4.1.1. Comparison Between CADGITE with and Without Distance Input

4.1.2. Comparison Between CADGITE and Original Approach

4.1.3. Comparison Between CADGITE and Physics-Based Models

5. Discussion

5.1. Advantages of our Methodology

5.2. Interpretation of the Performance of CADGITE

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zekollari, H.; Huss, M.; Farinotti, D.; Lhermitte, S. Ice-Dynamical Glacier Evolution Modeling—A Review. Reviews of Geophysics 2022, 60, e2021RG000754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farinotti, D.; Brinkerhoff, D.J.; Clarke, G.K.C.; Fürst, J.J.; Frey, H.; Gantayat, P.; Gillet-Chaulet, F.; Girard, C.; Huss, M.; Leclercq, P.W.; et al. How Accurate Are Estimates of Glacier Ice Thickness? Results from ITMIX, the Ice Thickness Models Intercomparison eXperiment. The Cryosphere 2017, 11, 949–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Pelt, W.J.J.; Oerlemans, J.; Reijmer, C.H.; Pettersson, R.; Pohjola, V.A.; Isaksson, E.; Divine, D. An Iterative Inverse Method to Estimate Basal Topography and Initialize Ice Flow Models. The Cryosphere 2013, 7, 987–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fürst, J.J.; Gillet-Chaulet, F.; Benham, T.J.; Dowdeswell, J.A.; Grabiec, M.; Navarro, F.; Pettersson, R.; Moholdt, G.; Nuth, C.; Sass, B.; et al. Application of a Two-Step Approach for Mapping Ice Thickness to Various Glacier Types on Svalbard. The Cryosphere 2017, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farinotti, D.; Huss, M.; Bauder, A.; Funk, M.; Truffer, M. A Method to Estimate the Ice Volume and Ice-Thickness Distribution of Alpine Glaciers. J. Glaciol. 2009, 55, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huss, M.; Farinotti, D. Distributed Ice Thickness and Volume of All Glaciers around the Globe. Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface 2012, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maussion, F.; Butenko, A.; Champollion, N.; Dusch, M.; Eis, J.; Fourteau, K.; Gregor, P.; Jarosch, A.H.; Landmann, J.; Oesterle, F.; et al. The Open Global Glacier Model (OGGM) v1.1. Geosci. Model Dev. 2019, 12, 909–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, H.; Machguth, H.; Huss, M.; Huggel, C.; Bajracharya, S.; Bolch, T.; Kulkarni, A.; Linsbauer, A.; Salzmann, N.; Stoffel, M. Estimating the Volume of Glaciers in the Himalayan–Karakoram Region Using Different Methods. The Cryosphere 2014, 8, 2313–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linsbauer, A.; Paul, F.; Haeberli, W. Modeling Glacier Thickness Distribution and Bed Topography over Entire Mountain Ranges with GlabTop: Application of a Fast and Robust Approach: REGIONAL-SCALE MODELING OF GLACIER BEDS. J. Geophys. Res. 2012, 117, F03007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsankaran, R.; Pandit, A.; Azam, M.F. Spatially Distributed Ice-Thickness Modelling for Chhota Shigri Glacier in Western Himalayas, India. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2018, 39, 3320–3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantayat, P.; Kulkarni, A.; Srinivasan, J. Estimation of Ice Thickness Using Surface Velocities and Slope: Case Study at Gangotri Glacier, India. Journal of Glaciology 2014, 60, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabatel, A.; Sanchez, O.; Vincent, C.; Six, D. Estimation of Glacier Thickness From Surface Mass Balance and Ice Flow Velocities: A Case Study on Argentière Glacier, France. Front. Earth Sci. 2018, 6, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, G.K.C.; Berthier, E.; Schoof, C.G.; Jarosch, A.H. Neural Networks Applied to Estimating Subglacial Topography and Glacier Volume. Journal of Climate 2009, 22, 2146–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, W.J.; Horgan, H.J. DeepBedMap: A Deep Neural Network for Resolving the Bed Topography of Antarctica. The Cryosphere 2020, 14, 3687–3705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, M.A.; Azam, M.F.; Vincent, C. Efficiency of Artificial Neural Networks for Glacier Ice-Thickness Estimation: A Case Study in Western Himalaya, India. J. Glaciol. 2021, 67, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez Uroz, L.; Yan, Y.; Benoit, A.; Rabatel, A.; Giffard-Roisin, S.; Lin-Kwong-Chon, C. Using Deep Learning for Glacier Thickness Estimation at a Regional Scale. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sensing Lett. 2024, 21, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnier, J.; Zhu, J. Physically-Constrained Data-Driven Inversions to Infer the Bed Topography beneath Glaciers Flows. Application to East Antarctica. Comput Geosci 2021, 25, 1793–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steidl, V.; Bamber, J.L.; Zhu, X.X. Physics-Aware Machine Learning for Glacier Ice Thickness Estimation: A Case Study for Svalbard. The Cryosphere 2025, 19, 645–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Computer Vision – ECCV 2018; Ferrari, V., Hebert, M., Sminchisescu, C., Weiss, Y., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; ISBN 978-3-030-01233-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Q.; Zhou, D.; Feng, J. Coordinate Attention for Efficient Mobile Network Design. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Nashville, TN, USA, June, 2021; pp. 13708–13717. [Google Scholar]

- Linsbauer, A.; Huss, M.; Hodel, E.; Bauder, A.; Fischer, M.; Weidmann, Y.; Bärtschi, H.; Schmassmann, E. The New Swiss Glacier Inventory SGI2016: From a Topographical to a Glaciological Dataset. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 704189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grab, M.; Mattea, E.; Bauder, A.; Huss, M.; Rabenstein, L.; Hodel, E.; Linsbauer, A.; Langhammer, L.; Schmid, L.; Church, G.; et al. Ice Thickness Distribution of All Swiss Glaciers Based on Extended Ground-Penetrating Radar Data and Glaciological Modeling. J. Glaciol. 2021, 67, 1074–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RGI Consortium Randolph Glacier Inventory - A Dataset of Global Glacier Outlines, Version 6 2017.

- Welty, E.; Zemp, M.; Navarro, F.; Huss, M.; Fürst, J.J.; Gärtner-Roer, I.; Landmann, J.; Machguth, H.; Naegeli, K.; Andreassen, L.M.; et al. Worldwide Version-Controlled Database of Glacier Thickness Observations. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 3039–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhammer, L.; Grab, M.; Bauder, A.; Maurer, H. Glacier Thickness Estimations of Alpine Glaciers Using Data and Modeling Constraints. The Cryosphere 2019, 13, 2189–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millan, R.; Mouginot, J.; Rabatel, A.; Morlighem, M. Ice Velocity and Thickness of the World’s Glaciers. Nat. Geosci. 2022, 15, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swisstopo Bundesamt für Landestopografie swisstopo-swissALTI3D, Ausgabebericht 2019 2019.

- Raper, S.C.B.; Braithwaite, R.J. Glacier Volume Response Time and Its Links to Climate and Topography Based on a Conceptual Model of Glacier Hypsometry. The Cryosphere 2009, 3, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, G.; Cui, Z. Glacial Valley Cross-Profile Morphology, Tian Shan Mountains, China. Geomorphology 2001, 38, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaw, N.; Yousefi, S.; Gahrooei, M.R. Multimodal Data Fusion for Systems Improvement: A Review. IISE Transactions 2022, 54, 1098–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, T.; Guo, C.; Feng, X.; Chen, Y.; Song, J. A Comprehensive Survey on Deep Learning Multi-Modal Fusion: Methods, Technologies and Applications. CMC 2024, 80, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely Connected Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Honolulu, HI, July, 2017; pp. 2261–2269. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Las Vegas, NV, USA, June, 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Zafar, A.; Aamir, M.; Mohd Nawi, N.; Arshad, A.; Riaz, S.; Alruban, A.; Dutta, A.K.; Almotairi, S. A Comparison of Pooling Methods for Convolutional Neural Networks. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 8643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; IEEE: Salt Lake City, UT, June, 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Farinotti, D.; Huss, M.; Fürst, J.J.; Landmann, J.; Machguth, H.; Maussion, F.; Pandit, A. A Consensus Estimate for the Ice Thickness Distribution of All Glaciers on Earth. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Groups | Result 1 | Result 2 | Result 3 | Result 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CADGITE without Distance | 18.40 | 18.07 | 18.01 | 17.05 |

| CADGITE | 17.28 | 18.14 | 17.44 | 16.49 |

| Group | Result 1 | Result 2 | Result 3 | Result 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLUM with Distance | 17.51 | 17.89 | 17.85 | 16.37 |

| RGIId | Error Metrics | Millan | H&F | GlabTop2 | CADGITE |

| RGI60-10.00604 | MD | 4.56 | 29.37 | -0.25 | -0.27 |

| MAD | 13.62 | 30.78 | 9.62 | 8.88 | |

| RMSE | 16.89 | 34.96 | 12.45 | 10.53 | |

| RGI60-13.08055 | MD | 30.67 | 4.10 | 4.66 | -3.77 |

| MAD | 47.47 | 28.23 | 32.21 | 22.39 | |

| RMSE | 57.31 | 33.18 | 37.34 | 27.03 | |

| RGI60-13.08624 | MD | 34.30 | 23.60 | 23.91 | 10.18 |

| MAD | 37.70 | 30.81 | 31.02 | 18.05 | |

| RMSE | 48.98 | 36.50 | 37.43 | 22.58 | |

| RGI60-13.24602 | MD | -0.49 | -28.33 | -10.55 | -3.41 |

| MAD | 22.48 | 31.41 | 19.17 | 17.87 | |

| RMSE | 28.59 | 37.82 | 23.65 | 21.06 | |

| RGI60-13.24874 | MD | 29.56 | 31.70 | 22.50 | 1.67 |

| MAD | 35.82 | 35.11 | 23.45 | 15.75 | |

| RMSE | 43.03 | 41.40 | 29.61 | 19.88 | |

| RGI60-13.31356 | MD | -6.36 | 4.74 | -13.36 | -0.86 |

| MAD | 16.83 | 11.83 | 14.97 | 9.18 | |

| RMSE | 20.24 | 15.11 | 18.66 | 11.08 | |

| RGI60-13.32330 | MD | -17.03 | -22.42 | -31.87 | -38.12 |

| MAD | 22.40 | 24.89 | 32.99 | 38.51 | |

| RMSE | 26.61 | 29.65 | 36.59 | 41.93 | |

| RGI60-13.43165 | MD | 146.57 | 40.80 | 45.02 | 42.50 |

| MAD | 146.84 | 41.12 | 46.23 | 47.37 | |

| RMSE | 161.16 | 49.80 | 55.37 | 53.07 | |

| RGI60-13.45233 | MD | -9.91 | 19.45 | 18.79 | 26.00 |

| MAD | 22.00 | 21.88 | 22.11 | 27.96 | |

| RMSE | 26.62 | 25.86 | 28.39 | 33.45 | |

| RGI60-13.45334 | MD | -30.22 | -30.62 | -43.64 | -23.67 |

| MAD | 35.61 | 36.96 | 46.50 | 32.79 | |

| RMSE | 40.24 | 41.07 | 50.83 | 36.26 | |

| RGI60-13.45335 | MD | -22.54 | -26.08 | -35.58 | -5.55 |

| MAD | 31.07 | 29.92 | 38.03 | 20.53 | |

| RMSE | 35.72 | 35.52 | 44.43 | 24.98 | |

| RGI60-13.47247 | MD | 13.72 | 3.09 | 2.90 | 18.83 |

| MAD | 22.14 | 18.87 | 13.19 | 23.74 | |

| RMSE | 27.70 | 22.89 | 16.08 | 3073 | |

| RGI60-13.48211 | MD | 6.39 | 48.20 | 76.63 | -2.50 |

| MAD | 27.60 | 51.64 | 81.61 | 29.56 | |

| RMSE | 36.72 | 61.76 | 95.67 | 37.75 | |

| RGI60-14.15990 | MD | -17.82 | -16.48 | -8.82 | -49.90 |

| MAD | 47.07 | 56.23 | 50.19 | 61.28 | |

| RMSE | 55.16 | 63.00 | 55.42 | 73.31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).