Submitted:

19 May 2025

Posted:

20 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of APTES Modified Fe3O4 Nanoparticles

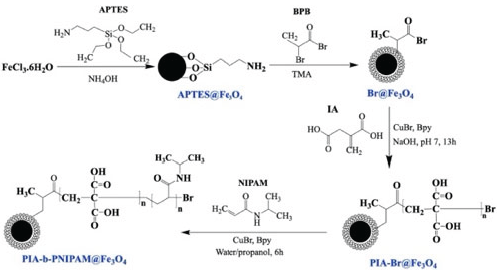

2.3. Surface-Initiated Block Copolymerization of Itaconic acid (IA) and N-Isopropyl Acrylamide (NIPAM) on Fe3O4 Nanoparticles

2.4. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgment

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lochhead, R. The Use of Polymers in Cosmetic Products. Cosmet. Sci. Technol. Theor. Princ. Appl. 2017, 13, 171–221. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf, M.; Eskandarinezhad, S. Journal of Composites and Compounds. J. Compos. Compd. 2021, 3, 275–290. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Sudhakara, P.; Omran, A. A. B.; Singh, J.; Ilyas, R. Recent Trends and Developments in Conducting Polymer Nanocomposites for Multifunctional Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadasivuni, K. K.; Hegazy, S. M.; Aly, Aa. A. M. A.; Waseem, S.; Karthik, K. Polymers in Electronics. In Polymer science and innovative applications; Elsevier, 2020; pp 365–392.

- Chen, Y.; Liu, G.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Li, R.-W.; Wang, L. Polymer Memristor for Information Storage and Neuromorphic Applications. Mater. Horiz. 2014, 1, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikada, Y. Surface Modification of Polymers for Medical Applications. Biomaterials 1994, 15, 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Sudhakara, P.; Omran, A. A. B.; Singh, J.; Ilyas, R. Recent Trends and Developments in Conducting Polymer Nanocomposites for Multifunctional Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moinudeen, G.; Ahmad, F.; Kumar, D.; Al-Douri, Y.; Ahmad, S. IoT Applications in Future Foreseen Guided by Engineered Nanomaterials and Printed Intelligence Technologies a Technology Review. Int. J. Internet Things 2017, 6, 106–148. [Google Scholar]

- Mao Png, Z.; Wang, C.-G.; Chuan Yeo, J. C.; Cheng Lee, J. J.; Erdeanna Surat’man, N.; Lin Tan, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, P.; Hoon Tan, B.; Wei Xu, J.; Jun Loh, X.; Zhu, Q. Stimuli-Responsive Structure–Property Switchable Polymer Materials. Mol. Syst. Des. Eng. 2023, 8, 1097–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiruta, Y. Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide)-Based Temperature- and pH-Responsive Polymer Materials for Application in Biomedical Fields. Polym. J. 2022, 54, 1419–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J. E.; Macdonald, M.; Nie, J.; Bowman, C. N. Structure and Swelling of Poly(Acrylic Acid) Hydrogels: Effect of pH, Ionic Strength, and Dilution on the Crosslinked Polymer Structure. Polymer 2004, 45, 1503–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, T.; Swanson, L.; Geoghegan, M.; Rimmer, S. The pH-Responsive Behaviour of Poly(Acrylic Acid) in Aqueous Solution Is Dependent on Molar Mass. Soft Matter 2016, 12, 2542–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, T.; Hu, L.; Shen, Q.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Serpe, M. J. Stimuli-Responsive Polymer-Based Systems for Diagnostic Applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 7042–7061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trehan, K.; Saini, M.; Thakur, S. Stimuli-Responsive Material in Controlled Release of Drug. In Engineered Biomaterials: Synthesis and Applications; Malviya, R., Sundram, S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagay, Z. A.; Rongpi, S. Stimuli-Responsive In-Situ Gelling Systems: Smart Polymers for Enhanced Drug Delivery.

- Ahadi, F.; Bahmanpour, A. H.; Mozafari, M. 14 - Stimuli-Responsive Polymers for Biomedical Applications. In Handbook of Polymers in Medicine; Mozafari, M., Singh Chauhan, N. P., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Biomaterials; Woodhead Publishing, 2023; pp 401–423. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Jung, K.; Li, A.; Liu, J.; Boyer, C. Recent Advances in Stimuli-Responsive Polymer Systems for Remotely Controlled Drug Release. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2019, 99, 101164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Municoy, S.; Álvarez Echazú, M. I.; Antezana, P. E.; Galdopórpora, J. M.; Olivetti, C.; Mebert, A. M.; Foglia, M. L.; Tuttolomondo, M. V.; Alvarez, G. S.; Hardy, J. G.; Desimone, M. F. Stimuli-Responsive Materials for Tissue Engineering and Drug Delivery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Yu, L.; Ding, J. PEG-Based Thermosensitive and Biodegradable Hydrogels. Acta Biomater. 2021, 128, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, A.; Ajazuddin, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Khan, J.; Saraf, S.; Saraf, S. Polyethylene Glycol (PEG)–Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAAm) Based Thermosensitive Injectable Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2014, 88, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, S.; Dhawan, K.; Varma, M.; Sinha, V. Applications of Poly (Ethylene Oxide) in Drug Delivery Systems. Pharm Technol 2005, 29, 82–96. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, H.-C.; Hsiue ,Ging-Ho; Lee ,Yang-Ping; and Huang, L.-W. Synthesis and Characterization of pH-Sensitive Dextran Hydrogels as a Potential Colon-Specific Drug Delivery System. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 1999, 10, 591–608. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Sun ,Jihong; Bai ,Shiyang; and Wu, X. pH-Sensitive Performance of Dextran–Poly(Acrylic Acid) Copolymer and Its Application in Controlled in Vitro Release of Ibuprofen. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2017, 66, 900–906. [CrossRef]

- Bardajee, G. R.; Hooshyar, Z.; Rastgo, F. Kappa Carrageenan-g-Poly (Acrylic Acid)/SPION Nanocomposite as a Novel Stimuli-Sensitive Drug Delivery System. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2013, 291, 2791–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Lin, S.; Xie, R.; Ju, X.-J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, W.; Mou, C.-L.; Zhao, C.; Chen, Q.; Chu, L.-Y. pH-Responsive Poly(Ether Sulfone) Composite Membranes Blended with Amphiphilic Polystyrene-Block-Poly(Acrylic Acid) Copolymers. J. Membr. Sci. 2014, 450, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Chacón, J.; Arbeláez, M. I. A.; Jorge, J. H.; Marques, R. F. C.; Jafelicci, M. pH-Responsive Poly(Aspartic Acid) Hydrogel-Coated Magnetite Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 77, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, P.; Li, D.; Jin, S.; Ding, J.; Guo, J.; Shi, W.; Wang, C. Stimuli-Responsive Biodegradable Poly(Methacrylic Acid) Based Nanocapsules for Ultrasound Traced and Triggered Drug Delivery System. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 2079–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Zhang, D.; Han, L.; Tejada, J.; Ortiz, C. Synthesis, Preparation, and Conformation of Stimulus-Responsive End-Grafted Poly(Methacrylic Acid-g-Ethylene Glycol) Layers. Soft Matter 2006, 2, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebishima, T.; Yuba, E.; Kono, K.; Takeshima, S.; Ito, Y.; Aida, Y. The pH-Sensitive Fusogenic 3-Methyl-Glutarylated Hyperbranched Poly(Glycidol)-Conjugated Liposome Induces Antigen-Specific Cellular and Humoral Immunity. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2012, 19, 1492–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kim, I.; Lu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yu, D.-G.; Song, W. Intelligent Poly(l-Histidine)-Based Nanovehicles for Controlled Drug Delivery. J. Controlled Release 2022, 349, 963–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rey, M.; Fernandez-Rodriguez, M. A.; Karg, M.; Isa, L.; Vogel, N. Poly-N-Isopropylacrylamide Nanogels and Microgels at Fluid Interfaces. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, M.; Hebels, E.; Hennink, W. E.; Vermonden, T. Poly (N-isopropylacrylamide): Physicochemical Properties and Biomedical Applications. Temp. Polym. Chem. Prop. Appl. 2018, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Shaibie, N. A.; Ramli, N. A.; Mohammad Faizal, N. D. F.; Srichana, T.; Mohd Amin, M. C. I. Poly (N-isopropylacrylamide)-Based Polymers: Recent Overview for the Development of Temperature-Responsive Drug Delivery and Biomedical Applications. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2023, 224, 2300157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Active Control of SPR by Thermoresponsive Hydrogels for Biosensor Applications | The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/jp400255u (accessed 2025-05-10).

- Toma, M.; Jonas, U.; Mateescu, A.; Knoll, W.; Dostalek, J. Active Control of SPR by Thermoresponsive Hydrogels for Biosensor Applications. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 11705–11712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Wang, L.; Yang, X.; Feng, Y.; Li, Y.; Feng, W. Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide)-Based Smart Hydrogels: Design, Properties and Applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 115, 100702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, H.; Sanchez, J. G.; Tsinman, T.; Langer, R.; Khademhosseini, A. Thermoresponsive Platforms for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. AIChE J. Am. Inst. Chem. Eng. 2011, 57, 3249–3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uthman, H. Advances in Membranes for High Temperature Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cells; 2013; pp 1–25.

- VINCE, M.; AUGUSTYNIAK, A.; Durant, Y.; Shaw, J. Soluble Aqueous Compositions of Selected Polyitaconic Acid Polymers. WO2015100412A1, July 2, 2015. https://patents.google.com/patent/WO2015100412A1/en (accessed 2025-05-10).

- Lanzalaco, S.; Armelin, E. Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide) and Copolymers: A Review on Recent Progresses in Biomedical Applications. Gels 2017, 3, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Tao, X.; Cui, Y.; Satoh, T.; Kakuchi, T.; Duan, Q. Synthesis of End-Functionalized Poly( N -Isopropylacrylamide) with Group of Asymmetrical Phthalocyanine via Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization and Its Photocatalytic Oxidation of Rhodamine B. Polym. Chem. 2011, 2, 2590–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Charleux, B.; Matyjaszewski, K. Controlled/Living Radical Polymerization in Aqueous Media: Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Systems. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2001, 26, 2083–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabibullin, A.; Mastan, E.; Matyjaszewski, K.; Zhu, S. Surface-Initiated Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization. In Controlled Radical Polymerization. In Controlled Radical Polymerization at and from Solid Surfaces; Vana, P., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yar, Y.; Khodadust, R.; Akkoc, Y.; Utkur, M.; Saritas, E. U.; Gozuacik, D.; Acar, H. Y. Development of Tailored SPION-PNIPAM Nanoparticles by ATRP for Dually Responsive Doxorubicin Delivery and MR Imaging. J. Mater. Chem. B 2018, 6, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Chen, Z. Function-Driven Design of Stimuli-Responsive Polymer Composites: Recent Progress and Challenges. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6, 11817–11834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.-Z.; Hong, C.-Y.; Pan, C.-Y. Preparation of Smart Polymer/Carbon Nanotube Conjugates via Stimuli-Responsive Linkages. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2007, 17, 2470–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, J.; Minko, T. Multifunctional and Stimuli-Responsive Nanocarriers for Targeted Therapeutic Delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2021, 18, 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakpour, E.; Salehi, S.; Naghib, S. M.; Ghorbanzadeh, S.; Zhang, W. Graphene-Based Nanomaterials for Stimuli-Sensitive Controlled Delivery of Therapeutic Molecules. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1129768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, D.; Yang, T.; Yang, J.; Fu, S.; Zhang, S. Targeting Strategies for Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles in Cancer Therapy. Acta Biomater. 2020, 102, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talelli, M.; Rijcken, C. J. F.; Lammers, T.; Seevinck, P. R.; Storm, G.; van Nostrum, C. F.; Hennink, W. E. Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Encapsulated in Biodegradable Thermosensitive Polymeric Micelles: Toward a Targeted Nanomedicine Suitable for Image-Guided Drug Delivery. Langmuir 2009, 25, 2060–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Near-infrared light remote-controlled intracellular anti-cancer drug delivery using thermo/pH sensitive nanovehicle - ScienceDirect. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1742706115000367?ref=pdf_download&fr=RR-2&rr=93c9b2507c666162 (accessed 2025-05-10).

- L. Moore, T.; Rodriguez-Lorenzo, L.; Hirsch, V.; Balog, S.; Urban, D.; Jud, C.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B.; Lattuada, M.; Petri-Fink, A. Nanoparticle Colloidal Stability in Cell Culture Media and Impact on Cellular Interactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 6287–6305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, X.-M.; He, T. Kinetics of (3-Aminopropyl)Triethoxylsilane (APTES) Silanization of Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Langmuir 2013, 29, 15275–15282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Yan, Y.; Roberts, C.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Y. The Role of Dipole Interactions in Hyperthermia Heating Colloidal Clusters of Densely-Packed Superparamagnetic Nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, S.; Mahmoudi, M. Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Promises for Diagnosis and Treatment of Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Epidemiol. Genet. 2011, 2, 367–390. [Google Scholar]

- Wahajuddin; and Arora, S. Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Magnetic Nanoplatforms as Drug Carriers. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2012, 7, 3445–3471. [CrossRef]

- Pucci, C.; Degl’Innocenti, A.; Gümüş, M. B.; Ciofani, G. Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Magnetic Hyperthermia: Recent Advancements, Molecular Effects, and Future Directions in the Omics Era. Biomater. Sci. 2022, 10, 2103–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles in the Era of Personalized Medicine. Nanotheranostics 2023, 7, 424–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A. I.; Miranda, M. S.; Rodrigues, M. T.; Reis, R. L.; Gomes, M. E. Magnetic Responsive Cell-Based Strategies for Diagnostics and Therapeutics. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 13, 054001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Full article: Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: magnetic nanoplatforms as drug carriers. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.2147/IJN.S30320 (accessed 2025-05-10).

- Ramanujan, R. V.; Ang, K. L.; Venkatraman, S. Magnet–PNIPA Hydrogels for Bioengineering Applications. J. Mater. Sci. 2009, 44, 1381–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthika, V.; AlSalhi, M. S.; Devanesan, S.; Gopinath, K.; Arumugam, A.; Govindarajan, M. Chitosan Overlaid Fe3O4/rGO Nanocomposite for Targeted Drug Delivery, Imaging, and Biomedical Applications. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyiler, E.; Walters, K. B. Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Grafted with Poly (Itaconic Acid)-Block-Poly (N-Isopropylacrylamide). Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2014, 444, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conzatti, G.; Chamary, S.; De Geyter, N.; Cavalie, S.; Morent, R.; Tourrette, A. Surface Functionalization of Plasticized Chitosan Films through PNIPAM Grafting via UV and Plasma Graft Polymerization. Eur. Polym. J. 2018, 105, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakar, M. U.; Khan, K.; Akram, M.; Sami, R.; Khojah, E.; Iqbal, I.; Helal, M.; Hakeem, A.; Deng, Y.; Dai, R. Synthesis of Bimetallic Nanoparticles Loaded on to PNIPAM Hybrid Microgel and Their Catalytic Activity. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta-Ángeles, G.; Kanizsová, L.; Mielczarek, K.; Konefał, M.; Konefał, R.; Hodan, J.; Kočková, O.; Bednarz, S.; Beneš, H. Sustainable Aerogels Based on Biobased Poly (Itaconic Acid) for Adsorption of Cationic Dyes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 259, 129727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorbani, M.; Hamishehkar, H.; Arsalani, N.; Entezami, A. A. Surface Decoration of Magnetic Nanoparticles with Folate-Conjugated Poly (N-Isopropylacrylamide-Co-Itaconic Acid): A Facial Synthesis of Dual-Responsive Nanocarrier for Targeted Delivery of Doxorubicin. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2016, 65, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anushree, C.; Krishna, D. N. G.; Philip, J. Synthesis of Ni Doped Iron Oxide Colloidal Nanocrystal Clusters Using Poly (N-Isopropylacrylamide) Templates for Efficient Recovery of Cefixime and Methylene Blue. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 650, 129616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, R.; Matsuyama, T.; Ida, J. Effect of Immobilization Method and Particle Size on Heavy Metal Ion Recovery of Thermoresponsive Polymer/Magnetic Particle Composites. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020, 590, 124499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A. L.; Hassabo, A. G. Core–Shell Titanium@ Silica Nanoparticles Impregnating in Poly (Itaconic Acid)/Poly (N-Isopropylacrylamide) Microgel for Multifunctional Cellulosic Fabrics. J. Polym. Res. 2022, 29, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 11.5: Infrared Spectra of Some Common Functional Groups. Chemistry LibreTexts. https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Organic_Chemistry/Map%3A_Organic_Chemistry_(Wade)_Complete_and_Semesters_I_and_II/Map%3A_Organic_Chemistry_(Wade)/11%3A_Infrared_Spectroscopy_and_Mass_Spectrometry/11.05%3A_Infrared_Spectra_of_Some_Common_Functional_Groups (accessed 2025-05-11).

| Synthesis Method | Polymer used | Functionalization | MNP | Nanocomposite | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graft polymerization | Chitosan and PEG | PNIPAM | - | Chitosan films | Intended for medium suppuration wounds | Conzatti et al. [64] |

| One-step precipitation polymerization | PNIPAM | DNAzyme | - | PNIPAM/DNAzyme | Promising application in biocatalysts (bioassays and biosensors) | Li et al. |

| Polymerization of soap-free emulsion | NIPAM and acrylic acid (AA) | Thiol- and carboxyl-functionalized | Bimetallic (Cu/Pd) | PNIPAM-based bimetallic Cu/Pd | Possible application as hybrid catalytic materials in the synthesis of nitrogenous compounds with improved optical properties | Kakar et al. [65] |

| Thermal polymerization | Itaconic acid (IA) | Laponite RD | - | Nanocomposites hydrogels | Removal of cationic dyes | Huerta-Angeles et al.[66] |

| Radical polymerization | PNIPAM | PIA | Fe3O4-NPs | NIPAM-co-IA@Fe3O4 | Possible application as a nanocarrier for targeted doxorubicin delivery. | Ghorbani et al. [67] |

| Hydrothermal approach | N-Isopropylacrylamide | - | Nickel ion doped iron oxide NPs | NiFe2O4-PNIPAM or FM | Application as a template for the efficient recovery of cefixime and methylene blue | Anushree et al. [68] |

| Radical polymerization | PNIPAM | APTES and β-Alanine | MNP | Poly(NIPAM-co-AA) | The research study compared the ‘grafting to’ and the ‘in situ’ method | Sakai et al. [69] |

| Co-polymerization | PNIPAM | Poly(itaconic acid) (PAA) | TiO2@SiO2 | PNIPAM/PIA- TiO2@SiO2 | Investigation for antibacterial activities against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria (S. aureus and E. coli) | Mohamed and Hassabo[70] |

| Surface-initiated ATRP | PNIPAM | - | Fe3O4-NPs | SPION-PNIPAM | Application in contrast generation in MRI | Yar et al. [44] |

| Surface-initiated atom transfer radical polymerization | PNIPAM | Poly (itaconic acid) (PAA) | Fe3O4-Ps | Fe3O4-PIA-b-PNIPAM | Demonstration of the stimuli-responsive features (thermos-responsiveness) of the nanocomposites | Eyiler and Walters |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).