1. Introduction

On April 4, 2025, the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) approved the construction of Canada’s first nuclear power plant, which will be equipped with a light-water SMR [

1]. As a result, the BWRX-300 project has reached a significant milestone on its path to implementation. In parallel with the process of pursuing the construction permit, GE Hitachi has progressively released increasingly detailed project documentation into the public domain [

2,

3,

4,

5]. This transparency has facilitated independent and increasingly comprehensive assessments of the BWRX-300’s maturity, including critical evaluations of its safety features, economic viability, licensing readiness, and technological robustness.

The BWRX-300 reactor is presented as an improvement and simplification of the ESBWR reactor design. This new GE Hitachi initiative aims to enhance its commercial viability, contribute to the global transition toward lower carbon emissions, and attract investors beyond the traditional energy industry. This is achieved by scaling down the nuclear unit, implementing modular construction, and maintaining — or even enhancing — safety. The ESBWR reactor [

6] serves as a strong foundation for the BWRX-300 reactor, having obtained certification in the USA. However, no investment involving the ESBWR reactor with a capacity of approximately 1500 MW has been initiated, primarily due to business barriers present across all Euro-Atlantic countries regarding the construction of large-scale nuclear power stations.

A comparison of the business case for the BWRX-300 and the 1500 MW ESBWR is justified by the pioneering deployment in Canada and other proposed projects — including those in Poland — which envision the development of multi-unit clusters of BWRX-300 reactors at a single site, with a total generating capacity comparable to that of a single, large-scale ESBWR unit.

The first version of the conceptual BWRX-300 design was presented in 2019, and by 2020, significant modifications to the reactor building design had been implemented. GE Hitachi has yet to provide an explanation for the rationale behind these changes or their potential implications. This publication addresses these important issues, which were highlighted in the previous study [

7]. Their significance derives from the fundamental principle that transparency is essential for both the safety and economic viability of nuclear energy.

2. Reactor Building Overview

The conceptual design of the BWRX-300, first published in 2019, showed a containment structure integrated with a compact, underground reactor building. This concept was presented by GE Hitachi in a report submitted to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and subsequently published by the agency. Although the report is no longer available on the IAEA’s website, a copy can still be obtained from an alternative source [

8].

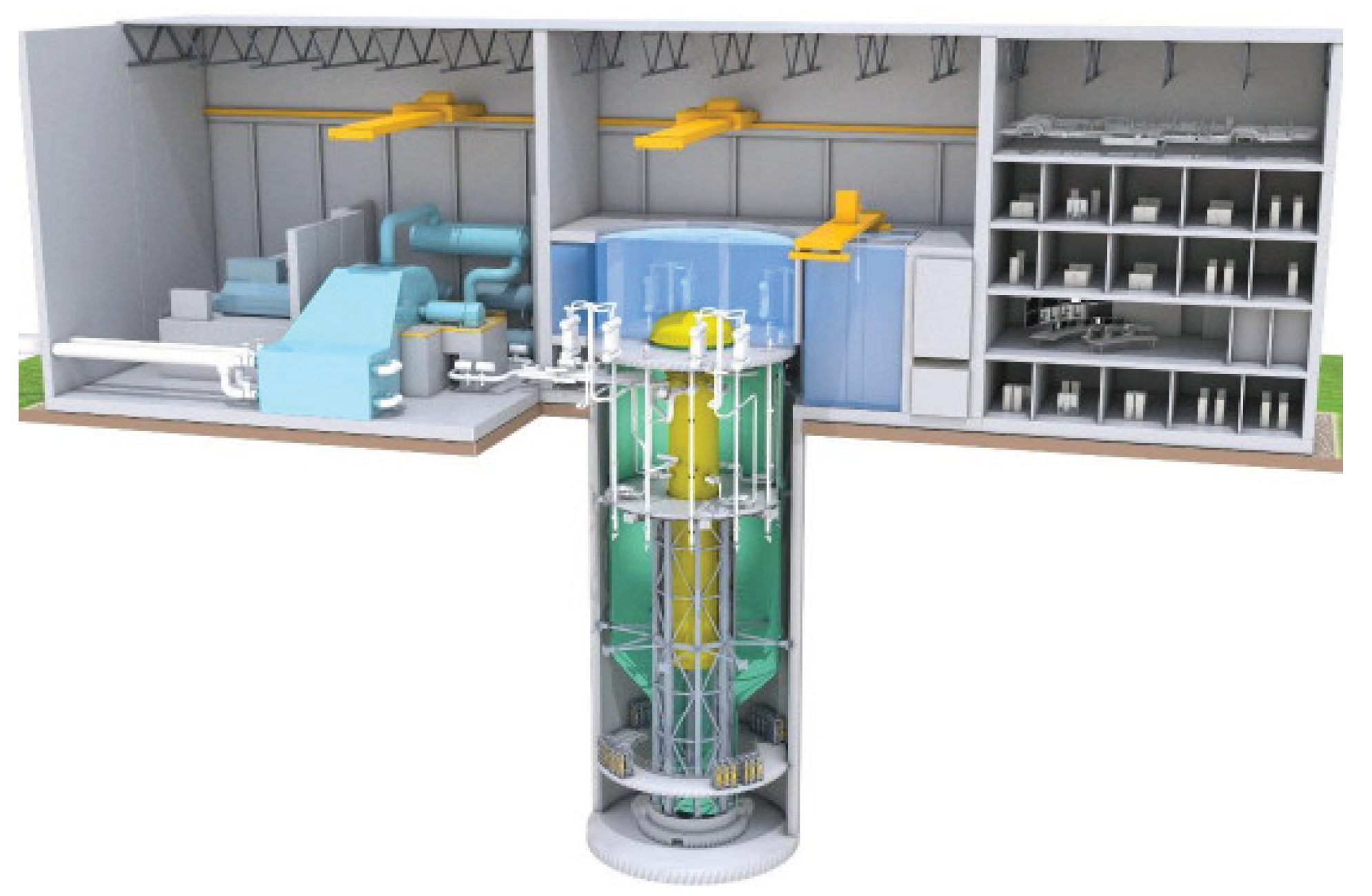

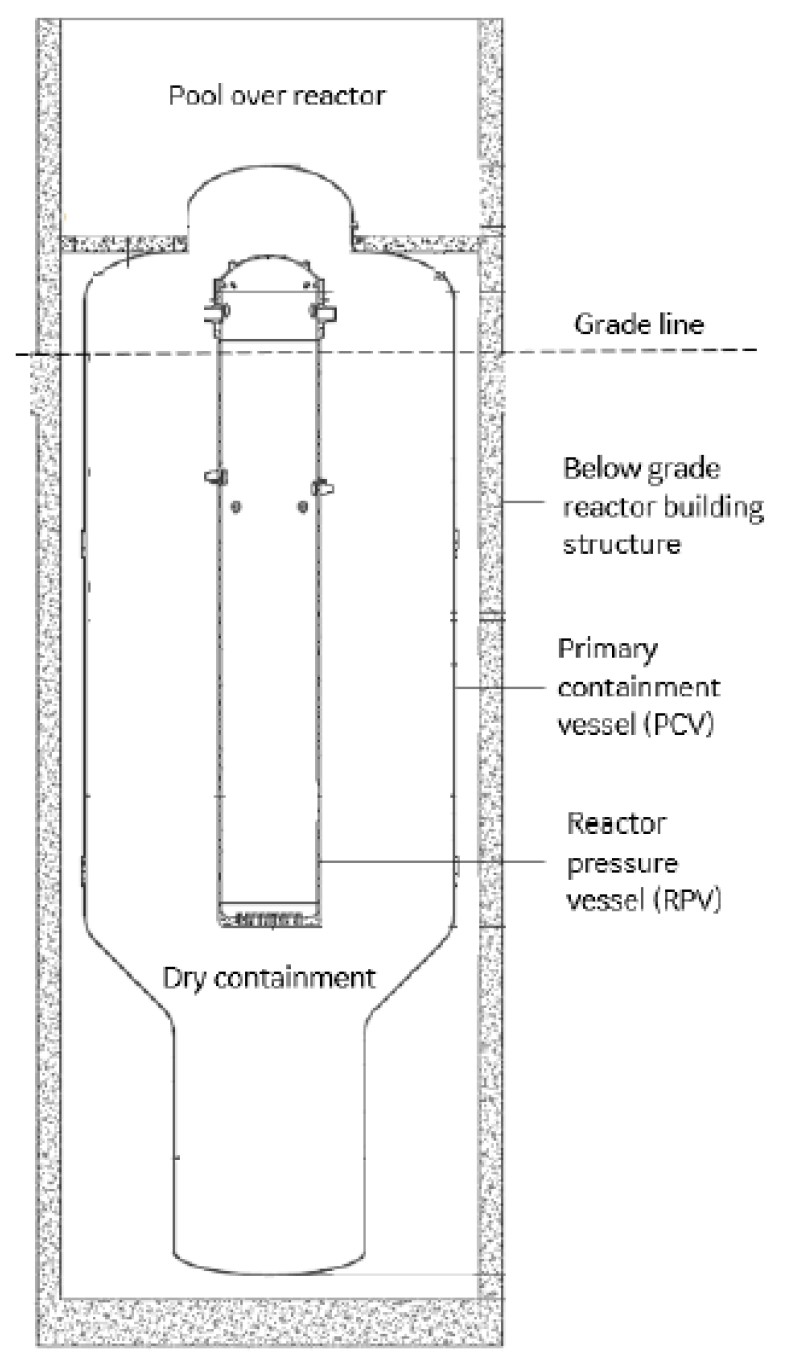

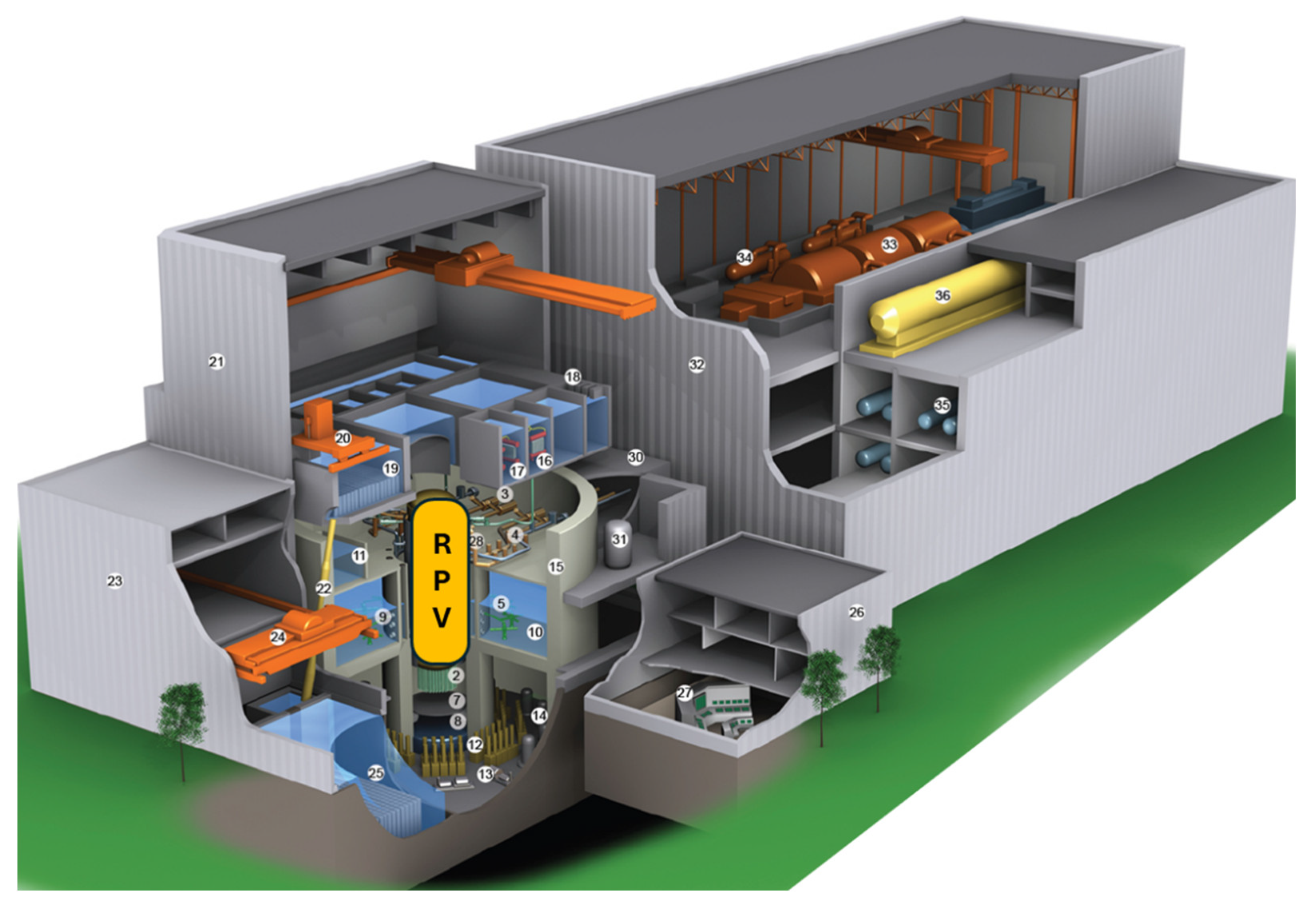

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, sourced from the referenced GE Hitachi report, illustrate the overall concept of the BWRX-300 (2019) nuclear power plant and a schematic representation of the underground reactor building, including the containment structure and the reactor pressure vessel, respectively.

There are no doubts that, in the presented BWRX-300 (2019) concept, the containment structure is in direct contact with the wall of the underground reactor building. As a result, external access to the containment for inspection or monitoring is not possible. This appears unusual, given that the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (U.S. NRC) mandates appropriate periodic inspection of all safety-significant areas, including the reactor containment [

9]. Consequently, it appears that conducting a leak-tightness inspection of the containment is unfeasible and likely constitutes a violation of one of the fundamental safety requirements widely recognized internationally, including by the IAEA [

10]. To date, GE Hitachi has not provided any publicly available explanation of how the first BWRX-300 (2019) design was intended to meet the safety requirements expected of the containment structure. Furthermore, none of the publicly available documentation from the pre-licensing dialogue between GE Hitachi and the U.S. NRC, addresses the BWRX-300 (2019) concept in which the containment structure is in direct contact with the wall of the underground reactor building. It is evident, however, that as early as GE Hitachi’s presentation to the U.S. NRC in October 2020, the BWRX-300 (2020) concept [

11] was introduced, in which the reactor building has a significantly larger diameter than the containment structure, thereby enabling the possibility of a leak-tightness inspection.

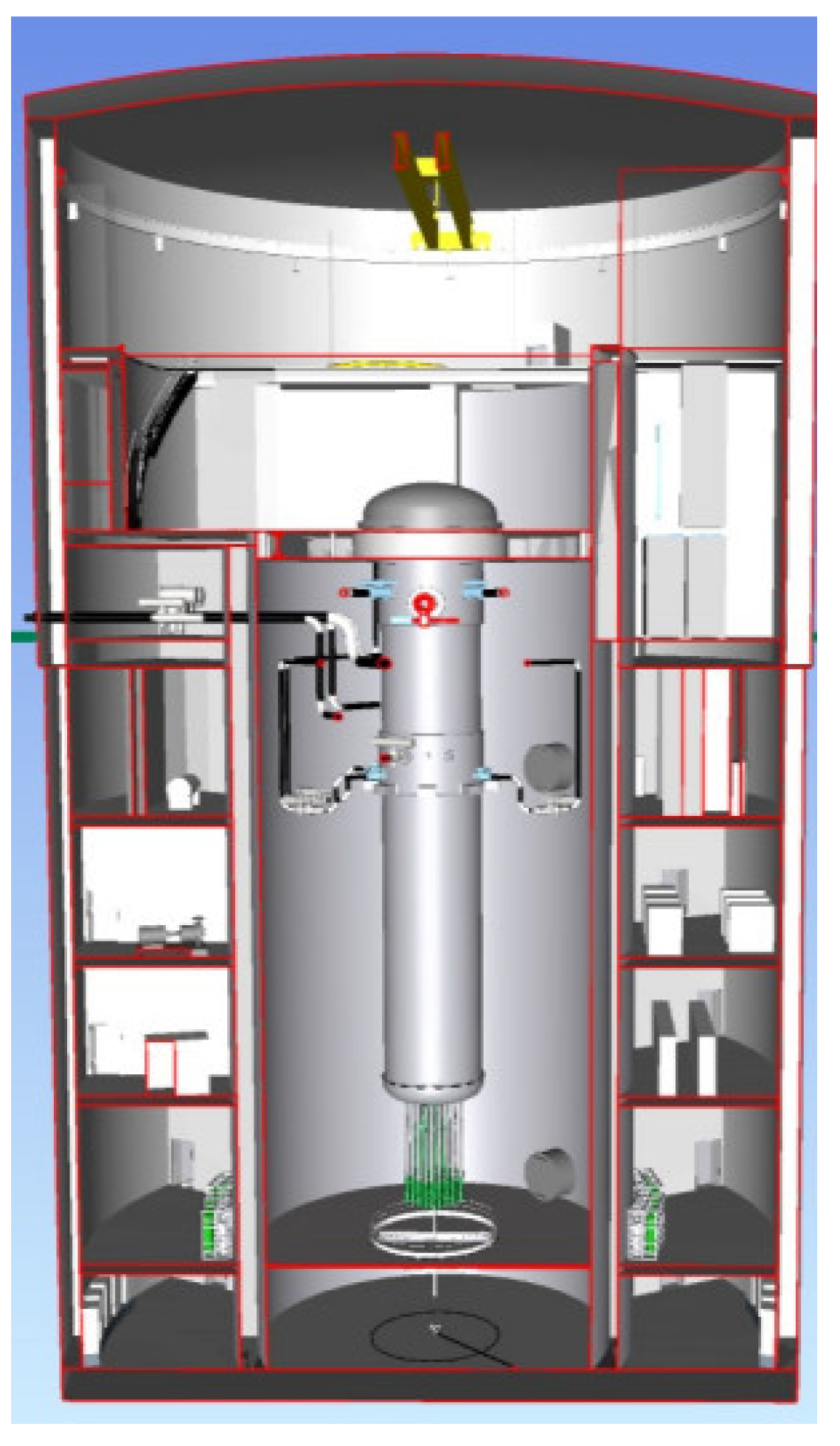

Figure 3 is taken from the cited presentation. The concept of a reactor building with a much larger diameter than the containment structure has been maintained to this day.

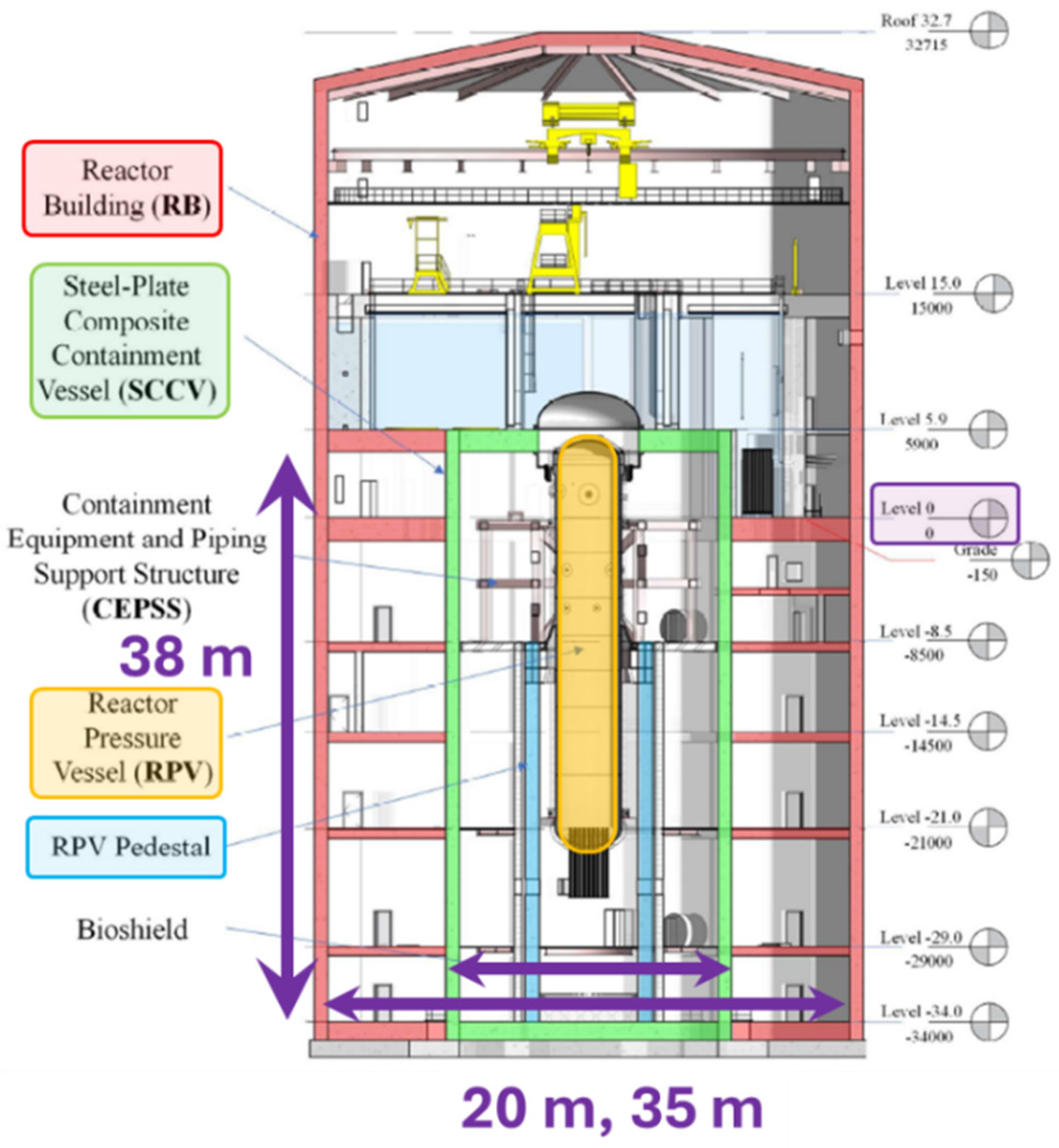

Figure 4 is from a GE Hitachi document [

12] submitted to the U.S. NRC in 2024, seeking approval for an innovative steel-concrete composite panel technology intended to replace conventional reinforced concrete structures.

Figure 4 illustrates the cylindrical reactor building of the BWRX-300 (2024), highlighted in red, with an estimated height of approximately 67 meters and a total enclosed volume of around 64,000 m³. The building’s foundation is designed to extend roughly 34 meters below grade. The Steel-Plate Composite Containment Vessel (SCCV), shown in green, is embedded almost entirely underground and encloses the centrally positioned Reactor Pressure Vessel (RPV), indicated in yellow.

The SCCV is engineered to meet regulatory requirements, specifically to withstand all Design-Basis Accidents (DBAs). Such events may result in the release of substantial volumes of steam from the RPV, causing a rapid increase in internal pressure. The SCCV is rated for internal overpressures up to approximately 413.7 kPaG [

13]. Consequently, its internal volume significantly exceeds that of the RPV—a design characteristic that is typical for light-water reactors employing steel-concrete containment.

A ring-shaped annular gap is incorporated between the SCCV and the surrounding underground reactor building to ensure inspection and maintenance of the containment structure. However, GE Hitachi has not yet provided a technical rationale for the relatively large volume of this space, estimated at approximately 25,000 m³, which accounts for nearly 40% of the total internal volume of the reactor building. According to publicly accessible documentation, this substantial and costly void remains largely unutilized, raising questions regarding the extent to which cost optimization was considered during the BWRX-300 design process.

While the below-grade placement of the RPV may enhance safety features, it also leads to significantly increased capital costs. Importantly, such a configuration has not been adopted in conventional nuclear power plants utilizing large-scale light-water reactors. The ESBWR, which serves as the reference design for the BWRX-300, similarly assumes an above-grade reactor building configuration.

Figure 5 shows a schematic representation of the ESBWR facility [

6], with an electrical capacity of approximately 1500 MWe.

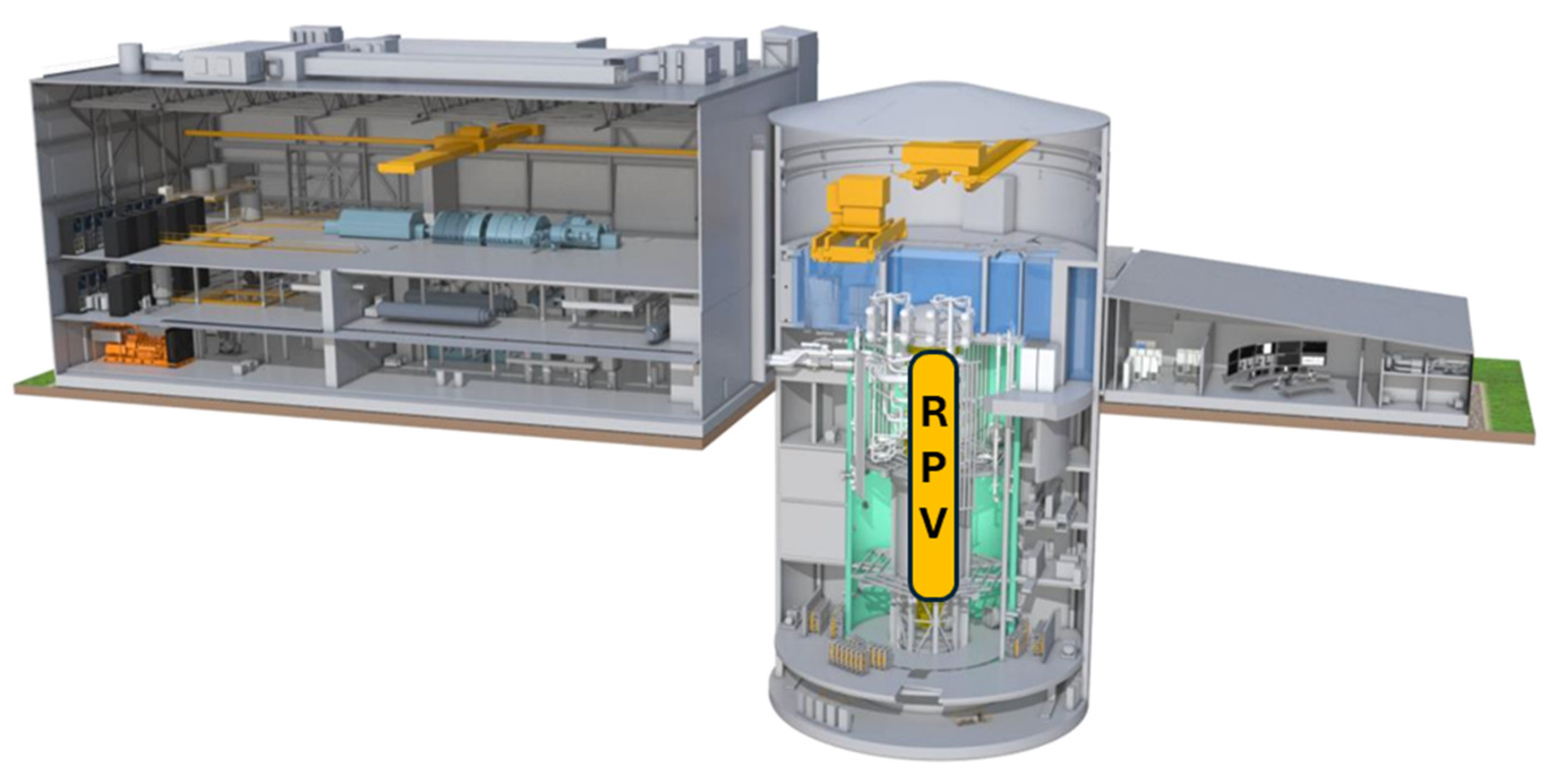

Figure 6 presents the current design layout of the BWRX-300 plant [

14], which is expected to deliver a nominal electrical output of approximately 300 MWe. To date, GE Hitachi has not provided a detailed technical justification for the decision to locate the BWRX-300 reactor vessel below grade. Notably, both the ESBWR and BWRX-300 designs feature RPVs of comparable height — approximately 27 meters. However, the internal diameters differ substantially: the ESBWR RPV measures 7.1 meters in diameter, whereas the BWRX-300 RPV is only 4 meters wide. As a result, the internal volume of the BWRX-300 RPV is roughly 3.2 times smaller than that of the ESBWR, despite the fact that its rated power output is lower by a factor of five. Although the lower power density in the BWRX-300 may offer improved safety margins, it inevitably leads to higher unit capital costs. Given the limited availability of publicly disclosed technical data, it is currently not possible to conclusively determine whether deploying multiple BWRX-300 units at a single site offers a cost-effective alternative to the construction of a single, large-scale ESBWR unit.

By abandoning the original — and arguably flawed — BWRX-300 (2019) design, which envisioned a compact underground reactor building integrated with the SCCV structure, GE Hitachi simultaneously forfeited a key argument in favor of the project: the reduction in the volume of costly reactor infrastructure, thus resulting in a reduction in capital investment. To mitigate the need for a significantly larger underground reactor building, the revised design incorporated an innovative construction technology: the use of steel-concrete composite panels as an alternative to conventional reinforced concrete. This approach is in line with modern engineering practices for nuclear facilities but introduces novel challenges regarding certification and regulatory compliance. Specifically, GE Hitachi proposed the use of welded plates with transverse diaphragms — a highly innovative technology that necessitates a comprehensive certification process in accordance with U.S. NRC regulations and ASME codes. This process spans all phases of the project, from design and material selection to fabrication, assembly, and final acceptance testing, ensuring compliance with all applicable nuclear safety standards and structural integrity requirements.

In August 2024, the U.S. NRC approved the topical report submitted by GE Hitachi, addressing the potential application of innovative steel-concrete composite panel technology [

15]. Consequently, GE Hitachi was obligated to prepare and publish a version of the document formally approved by the U.S. NRC. However, GEH chose not to publish the approved version and, in December 2024, submitted a revised third version of the report [

16] and U.S. NRC accepted this procedure [

17]. The final approval of this version is expected later in the year. In April 2025 it was announced that a research team led by GE Hitachi successfully tested a modular steel-concrete composite, which are anticipated to further support the certification process [

18]. Nonetheless, it remains unclear when the recently issued construction license in Canada will be extended to cover the use of this innovative technology. It is important to note that under the license [

1] issued on April 4, 2025 by the CNSC, the additional information will be required by CNSC prior to undertaking specific three construction activities including installation of the reactor building foundation and installation of the RPV [

19]. It is equally important that GE Hitachi disclose the estimated construction costs of the reactor building based on the innovative steel-concrete composite panel technology with welded diaphragms, which remains uncertified and unproven on an industrial scale.