Introduction

The nuclear energy sector in Euro-Atlantic countries has been stagnant for more than a quarter of a century. Hopes for breaking this stagnation are linked to, among other things, small modular reactors (SMRs). There are many indications that the first light-water SMR could be operational in the Euro-Atlantic region in the early or mid-2030s. This conclusion is based on information provided by SMR designers, nuclear power plant operators, government agencies, including regulators, and scientific publications. Maturity assessments of leading projects, including cost analyses, are particularly valuable, as seen, for example, in Stewart's recent publications [

1,

2,

3]. Without a doubt, all the publications cited by Stewart are also worth attention. It is evident that cost analyses are fraught with significant uncertainties, as demonstrated in [

4] and the subsequent discussion. The potential uses of SMRs are examined, which is the main focus of review articles like [

5,

6]. This article focuses on the strategies adopted by leading light-water SMR projects in Euro-Atlantic countries to increase the competitiveness of their designs.

Table 1 presents a list of selected projects, including basic details about each one. Five are pressurized water reactors (PWRs), while one is a boiling water reactor (BWR).

Implementing an effective cost-saving strategy is crucial for any SMR project due to the absence of economies of scale. The most basic model of economies of scale, which aligns well with advanced models [

13], suggests that the power output of a nuclear power plant is proportional to the volume of the reactor vessel. Meanwhile, the cost is linked to the quantity of material used, which corresponds to the surface area of the reactor vessel. This means that the cost of a nuclear power plant is proportional to its power raised to the two-thirds power. In particular, this simple model shows that an eight-fold increase in power results in only a four-fold increase in cost.

Historically, it is also known that no investor undertook the construction of the AP600, whereas six AP1000 reactors were built in China and the United States. Since 2022, China has initiated the construction of eight additional similar reactors under the name CAP1000. The primary distinction between the AP600 and AP1000 projects is their scale. On the other hand, it is well documented that over the last twenty-five years, only a few large-scale reactors have been built in Euro-Atlantic countries, and all investments have experienced significant delays and cost overruns. This situation creates opportunities for SMRs, while simultaneously challenges them to compensate for the loss of economies of scale and avoid the investment delays and cost overruns.

These finding indicate that achieving competitiveness requires innovation in all SMR projects. However, it should be emphasized that the potential market for SMRs is broader than just the power sector and includes energy-intensive industries whose energy demands are compatible with the capabilities of SMRs. It is also worth noting that the dynamically growing data centre investments, necessary for the development of artificial intelligence, will consume huge amounts of energy. It is possible that, in a decade or so, they will constitute a noticeable part of the energy-intensive industry in the world’s most developed economies. As a result, SMRs have the potential to establish a strong market presence, even if their competitiveness is slightly lower than large-scale reactors.

Approaches to Enhancing Competitiveness

The key innovation in all SMR designs is their modular construction. This approach divides the project into independent modules and then mass-producing standard modules in factories. For example, in the Westinghouse AP300 and Rolls-Royce SMR projects, there are no groundbreaking technical innovations. The only way to ensure these projects remain competitive is by constructing a large fleet of standardized power plants with a modular design. However, modularization of designs is also being implemented in large-scale nuclear power plants, as exemplified by the AP1000 project [

14]. It can be expected that Westinghouse will leverage experience gained from the AP1000 in developing the AP300.

The Rolls-Royce SMR design is based on the concept of deep modularity. This approach permeates every aspect of the design, as demonstrated by the designers [

15] and a recent publication by Wrigley [

16]. However, in this context, the modularity is based on the theoretical assumptions of the project and examples from other sectors, including chemical industry construction. Therefore, business validation of the project's usefulness will only be possible once the first investments are well advanced.

The situation is somewhat different in SMR projects based on technical innovations. In such cases, the modularity of the design is an integral part of the entire new design. However, technical innovations offer the potential for a competitive advantage but also carry the risk of delays and substantial cost increases, particularly when constructing first-of-a-kind units. On the other hand, abandoning technical innovations can provide an advantage by shortening the permitting process, leveraging the existing market of key component manufacturers, and utilizing the pool of experienced contractors. In this context, it becomes evident that making any decision regarding technical innovation is very challenging. The history of the circulation pumps in the AP1000 reactor illustrates this challenge well. By integrating the circulating pump motors into the primary cooling system (using canned motor pump technology), the design was significantly simplified by reducing the thermohydraulic systems. While these pumps performed adequately in submarine reactors, adapting them for the large-scale AP1000 reactor proved difficult [

17], and a pump failure caused an almost year-long shutdown of one of the Chinese AP1000 reactors [

18]. The difficulties in implementing innovative pumps caused notable delays in the construction of AP1000 reactors. However, the designers of the AP1000 met the challenge successfully, and it is now clear that the canned motor pump technology enhances the competitiveness of the AP1000.

Such determination is not common, and within the realm of light-water SMR projects, a notable withdrawal from technical innovation occurred in June 2024 when EDF pulled out of the NUWARD project [

19]. At the same time, it was announced that the revised NUWARD would rely solely on proven solutions. For example, the innovative plate steam generators will be excluded [

20]. Since the new NUWARD concept has not yet been unveiled, further analysis of the project remains impossible.

A similar innovation crisis occurred with the SMR-160 project, which was renamed SMR-300 in December 2023 [

21]. Holtec abandoned the direct connection of the reactor vessel to the steam generator because it could not provide satisfactory answers to the U.S. regulator's questions regarding the fulfilment of nuclear safety requirements by this innovative solution. The aim of directly connecting these two vessels was to eliminate the risk of a large break loss of coolant accident resulting from a rupture of the pipes connecting the reactor vessel with the steam generator. At the same time, this solution involved eliminating the circulation pumps. Abandoning this innovation meant returning to the classic system with traditional circulation pumps in the design and doubling the power from 160 to 320 MW while keeping almost unchanged reactor dimensions.

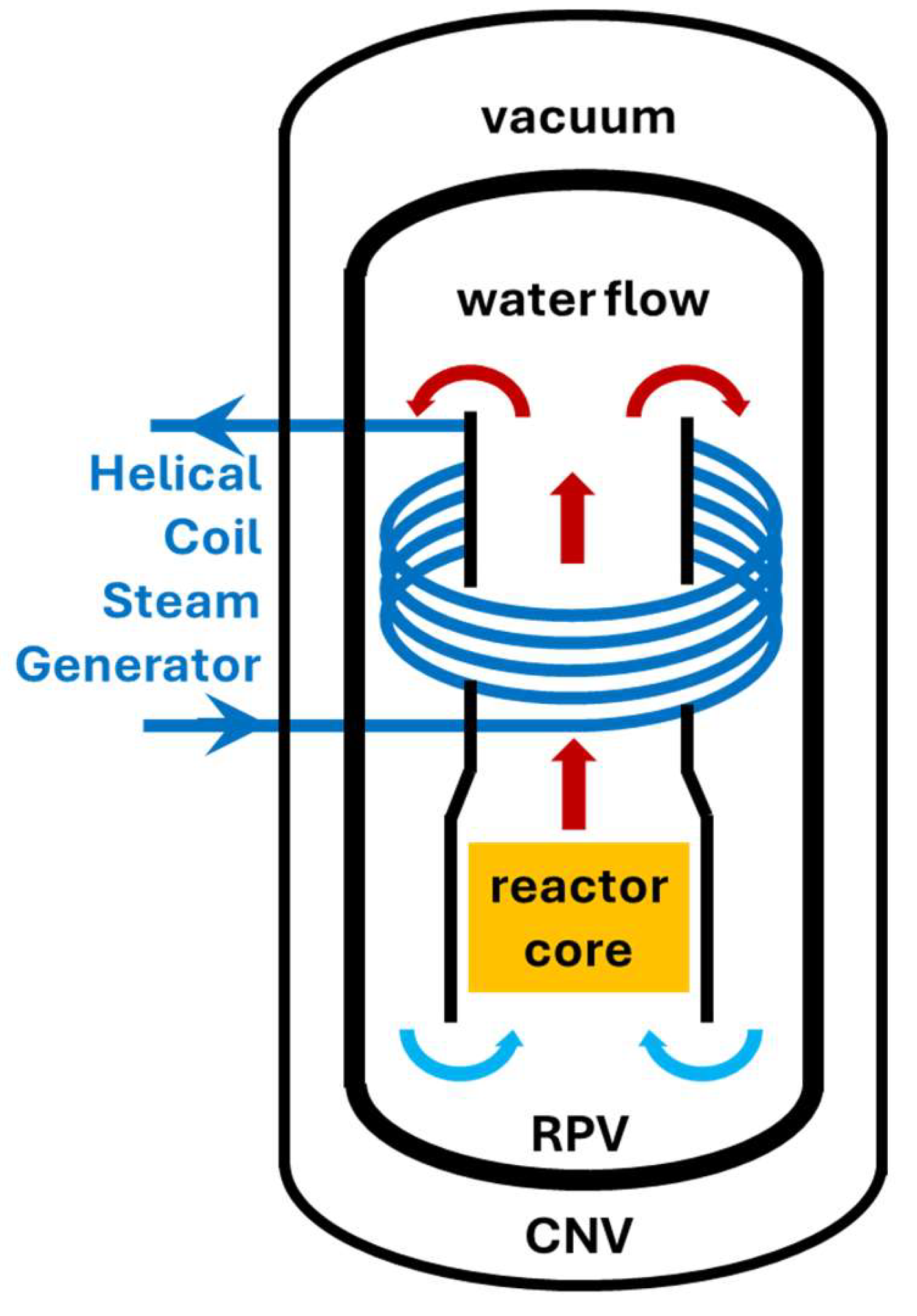

Among the leading selected light-water SMR projects, significant technical innovations are primarily found in the NuScale and BWRX-300 projects. The power output of a single NuScale module is the smallest among the considered SMR projects, leading to the greatest loss of economies of scale but offering the highest potential for gains from series production. Concurrently, the NuScale project incorporates the most extensive technical innovations, primarily focusing on system integration, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

Circulating pumps have been eliminated, and the steam generator is installed within the reactor vessel, which is housed in a compact, vacuum-sealed, cylindrical steel containment vessel. This integrated module is placed in a pool, remaining submerged in water, ensuring that the containment vessel is effectively cooled under any emergency condition. Such a design has the potential to significantly lower costs due to the small size of the containment vessel. In conventional PWR reactors, the containment building must be much larger than the reactor vessel since it is surrounded by air, making cooling during emergencies far less efficient and more complicated.

In the NuScale design, four to twelve integrated modules, each with an output of 77 MW, are to be placed in isolated sections of a common water pool, providing a total gross capacity of 308 to 924 MW. There is also a common spent fuel storage area and shared use of other facilities, including a common control room where a small group of operators will control all the modules. The U.S. regulator's certification process for the initial 50 MW module design spanned six years. Understanding the scope and significance of these innovations is crucial for evaluating whether the certification process could have been more efficiently. The U.S. regulator issued the certification in January 2023 but noted that it does not cover three specific issues, including the helical coil steam generator, due to insufficient information provided by NuScale. Efforts to approve the missing elements are ongoing as part of the certification process for the 77 MW modules, which is expected to be completed by mid-2025 [

22].

The helical coil steam generator offers higher efficiency than typical steam generators used in nuclear power plants with PWR reactors. Its small size offers the potential to reduce costs, however, in the NuScale project, it plays a key role due to the integrated design, in which the steam generator is installed inside the compact pressurized reactor vessel. It is also well known that the helical coil steam generator is subject to undesirable vibrations and the phenomenon of density wave oscillation. Maintaining a stable flow through the helical coil steam generator in the NuScale design is a key issue. Therefore, NuScale has recently conducted extensive theoretical research [

23] and, in collaboration with the SITE laboratory in Italy, has intensified the experimental studies that have been ongoing there for a decade [

24]. The significant interest in the stability of helical coil steam generators is also related to the possibility of their use in other SMR projects, such as the i-SMR project in South Korea [

25], and several SMRs designed based on non-light-water technologies. This is why numerous studies have been conducted in recent years, as illustrated by various publications [

26,

27,

28]. Publication [

29] refers directly to the NuScale helical coil steam generator design. Based on the information provided, it seems that ensuring safe and efficient flow through the helical coil steam generator in the NuScale design remains challenging but feasible. Unfortunately, the comprehensive documentation provided by the U.S. regulator reveals little about the certification progress of the helical coil steam generator, as key information has been withheld [

30].

It should be emphasized that the ongoing NuScale certification process does not cover the entire project. This concerns, for example, the refueling procedure, which in the NuScale design differs from the standard procedures used in large-scale reactors. Specifically, it is assumed that during the refueling of a given module, the other modules can continue to operate normally. The U.S. regulator does not question this concept, but approval of this procedure will only be possible at a later stage of the construction and operation permitting process.

The main challenge in the BWRX-300 project is the return to boiling water reactors, whose development has been paused since the Fukushima disaster in 2011. In Japan, only two out of about a dozen BWRs have recently restarted at the end of 2024 [

31]. However, the future restart of other BWRs remains unclear, and plans to build several large-scale ABWRs have been cancelled. In the United States, although two construction permits were granted, the construction of ABWRs never began, and both permits expired in 2018 [

32]. The BWRX-300 reactor is described as a smaller and simplified version of the large ESBWR, incorporating a passive, gravity-driven cooling system. However, no investor has proceeded with the construction of an ESBWR, despite the fact that two permits were granted in the U.S. in 2015 and 2017, both of which are still valid [

32]. The second point of reference for the BWRX-300 is the Dodewaard power plant, which housed a 55 MW passively cooled BWR reactor and operated in the Netherlands from 1971 to 1997. Despite years of operation with an availability rate of 80-90%, the plant was shut down for economic reasons.

In the initial publicly unveiled BWRX-300 design by GE Hitachi, the reactor building and containment structure were closely integrated and positioned underground. GE Hitachi presented this concept in a study submitted to the IAEA in 2019 [

33] (this document is not currently available on the IAEA website). The underground compact reactor building design aimed to minimize the use of concrete, which was highlighted as one of the key features of the BWRX-300 project, offering significant savings. However, this concept particularly prevented any external inspection of the containment vessel. It is therefore not surprising that in later versions of the BWRX-300, including the current one [

34,

35], the underground reactor building has a significantly larger diameter than the containment, allowing for inspection. Stewart [

36] estimated that the volume of the reactor building increased more than fourfold. Consequently, the amount of concrete required to construct the BWRX-300 has significantly increased, and a significant part of the cost reduction concept from 2019 is no longer relevant.

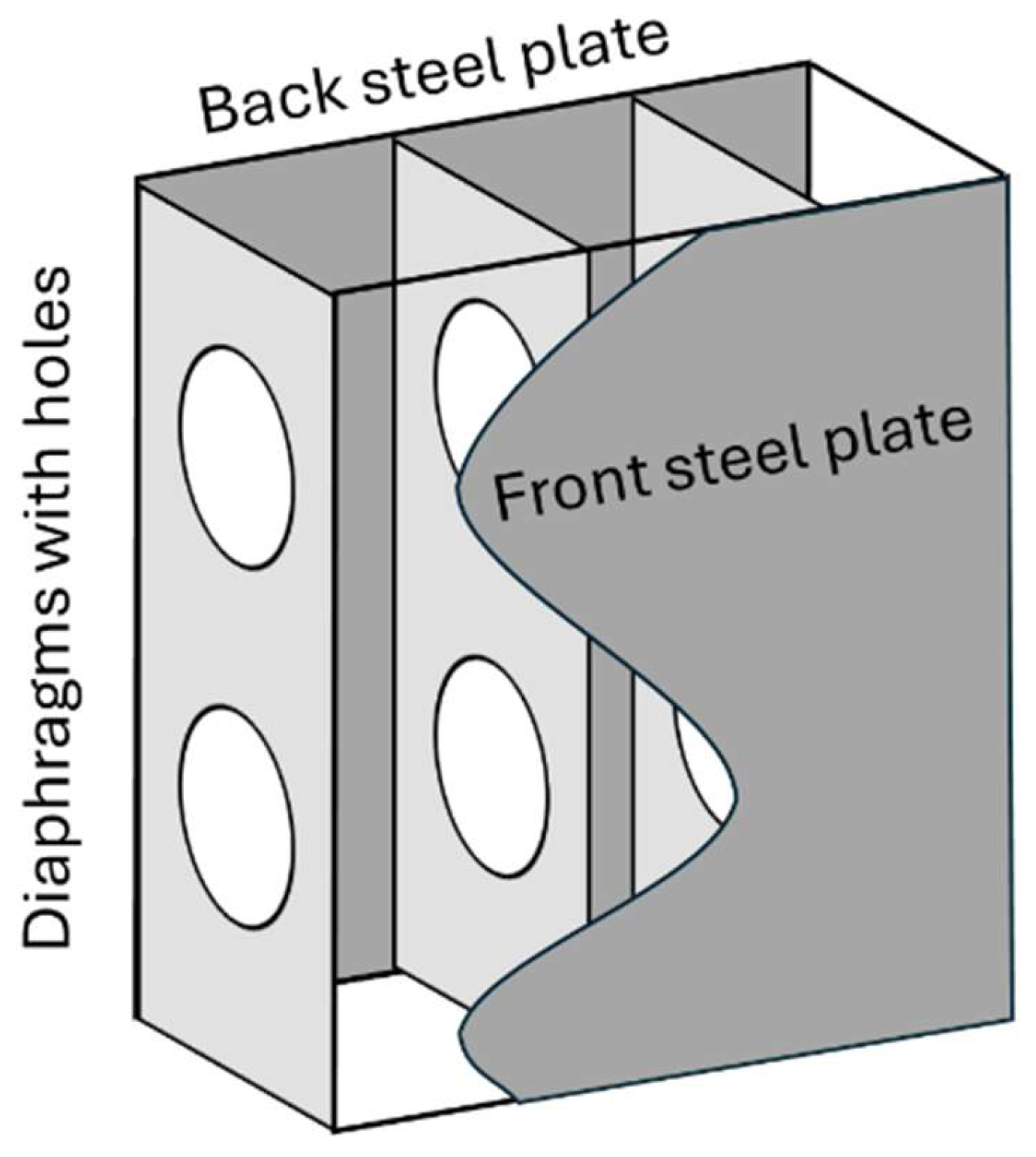

Alongside the substantial expansion of the reactor building, GE Hitachi proposed replacing conventional reinforced concrete with an innovative composite technology.

Figure 2 shows a diagram of the composite of steel plates with diaphragms. First, diaphragms with holes are welded to steel plates. Then, the assembled panels are positioned in the designated location and filled with concrete.

The recently published review article [

37] shows that composite steel-concrete structures are now increasingly used in various civil engineering projects, including nuclear power plant construction [

14,

38,

39]. Despite its potential, this technology has not yet been adopted in nuclear safety-related applications. In the BWRX-300 design, it is planned to be used for constructing the underground reactor building and containment vessel. Additionally, steel-plate composite technology with diaphragms is planned to be used, which has never been applied in nuclear power construction. In the summer of 2024, the U.S. regulatory body conducted a detailed evaluation of the concept [

40], and it looks like it could take several years of intense effort to get the final approval including the implementation procedures. However, if the composite steel-plate technology is commonly accepted by regulators and it turns out that its use reduces costs, we can expect its widespread use in nuclear construction. It is therefore worth observing work on its implementation not only in the BWRX-300 project but also in China [

39], where nuclear power is developing rapidly.

Among the other innovations in the BWRX-300, one notable change is the removal of pipelines connecting the reactor vessel to the isolation valves. This design eliminates the risk of pipe ruptures by directly attaching the isolation valves to the reactor vessel. The safety relief valves are also eliminated because the large capacity of the isolation condenser system, along with the large steam volume in the reactor pressure vessel, provides overpressure protection. These approaches have not been previously used in nuclear power plant construction, meaning their approval by regulators could be a lengthy process. Furthermore, the limited publicly available information from GE Hitachi hinders a comprehensive evaluation of the risks and potential benefits of this design [

34,

35]. Similarly, the simplification of the riser chimney, achieved by eliminating its channel structure, requires careful assessment. Since the introduction of the chimney concept in 1959 [

41], passively cooled BWR chimneys have been divided into channels to prevent radial flows that could disrupt reactor operations. GE Hitachi offered a detailed explanation of the chimney partition in the ESBWR design [

42], but provided little information about why it was possible to omit the chimney partition in the BWRX-300 design. As a result, assessing the feasibility of this innovation remains challenging.

Conclusions

In summary, none of the light-water SMR projects in the Euro-Atlantic region have obtained construction permits yet. The designs of the Rolls-Royce SMR, Holtec SMR-300, and Westinghouse AP300 do not introduce significant technical innovations compared to large-scale PWR reactors, which suggest so obtaining the necessary approvals for these projects should proceed without major obstacles. On the other hand, the NuScale and BWRX-300 projects introduce significant innovative elements, and their approval processes might face delays. However, these projects offer substantial innovation potential, which could lead to cost reductions. At this stage, it is challenging both to determine the most promising SMR project and to predict which approach to technical innovation will prove most effective.

The drive towards overall modularity is evident in all SMR designs. These concepts can be at least partially applied to other fields, such as the construction of large-scale nuclear power plants. Rolls-Royce's SMR design, in addition to its theoretical assumptions, utilizes insights gained from other sectors, including investments in the chemical industry. The AP300 design, on the other hand, relies on Westinghouse's experience in modularizing the AP1000 reactor.

GE Hitachi's work on the innovative implementation of steel-plate composite technology in the BWRX-300 design has the potential to be applied to other nuclear power plant projects. High expectations regarding the use of this technology in nuclear power emerged about a quarter of a century ago, but it is still in the certification process. Only after the technology is approved by regulators will it be possible to assess its business viability, which will most likely be clarified during the construction of the BWRX-300 reactor in Canada.

The integrated design of the reactor pressure vessel, the helical coil steam generator, and the compact containment immersed in the pool may ensure business success for the NuScale project. This project has been certified by the U.S. regulator for 50 MW modules, and certification for 77 MW modules is expected by mid-2025. However, the most significant obstacle for the NuScale project will be the construction of the first-of-a-kind power plant and the assessment of the business suitability of innovative solutions. The most advanced NuScale power plant project is currently being developed in Romania. Demonstrating the stable operation of the helical coil steam generator could have important implications for the development of many other advanced nuclear reactor designs and beyond nuclear industry.

All the discussed in this research study small modular light-water reactors carry significant potential, both commercially as well as technologically, however their implementation faces large number of challenges related to regulation and innovation. The success of developed technologies will mainly depend on the ability to properly manage the risk, speed-up certification processes, and to adapt to rapidly changing worldwide energy market.