1. Introduction: The Background of the Situation, the Goals, and Objectives of the Study

According to the 2015 Paris Agreement [

71], all its parties must formulate and submit to the secretariat of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) long-term development strategies with low greenhouse gas emissions for the period up to 2050 by 2020. To November 2024 74 countries have fulfilled this condition [

68]. Russia began developing a Long-term low-emission Development Strategy of Russia (LT LEDS) in 2019, and on October 29, 2021, it was approved by the Government of the Russian Federation [

42]. LT-LEDS are crucial frameworks that guide countries in aligning their developmental goals with the Paris Agreement’s objective to limit global warming to well below 2°C. These strategies provide a roadmap for transitioning national economies towards sustainable, low-carbon models by mid-century, integrating climate action with economic and social planning. LT-LEDS includes the strategies in LULUCF sector aimed to reduce emissions and increase absorption by ecosystems. Many Russian officials and representatives of business believe that it is principal country advantage if compare with many other countries.

Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) are key elements of the Paris Agreement that contribute to the achievement of its long-term goals. They reflect the efforts of specific countries to reduce emissions at the national level and to adapt to the effects of climate change. In accordance with the provisions of Article 4 of the Paris Agreement, each party prepares and sends to the UNFCCC secretariat its NDCs, which it adheres to and intends to achieve. They are subject to submission once every 5 years. A LT LEDS should be linked to the current NDC, since both documents represent the official position of the country in the context of the implementation of the Paris Agreement. On November 25, 2020, Russia announced its first NDC within the framework of the implementation of the Paris Agreement – consistent and providing for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 to 70% compared to the 1990 level, considering the maximum possible absorption capacity of forests and other ecosystems and subject to sustainable and balanced socio-economic development of the country [

69]. At the same time, according to the National Inventory of anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of Greenhouse Gases (GHG), the level of total net emissions in 2022 compared to the baseline in 1990 has already amounted to 31.3% [

69]. That is mainly due to collapse of state Soviet high carbon industry in the beginning of nineties and introduction of much less carbon intensive market-based industry, based on modern technological processes after the year 2000. No special measures for decarbonization of economy were implemented before 2020, so the decrease of emissions happened due to technological modernization. The emission reduction trajectory is still not in line with Paris agreement targets as Russia's NDC leads to a potential significant increase in GHG emissions from current levels. Therefore, according to the Climate Action Tracker rating [

9], Russian NDC is considered highly insufficient, since it corresponds to the trajectory of temperature growth up to 4°C instead of keeping the temperature increase within 1.5–2°C according to the Paris Agreement.

This research is aimed to define and discuss the different scenarios of achieving carbon neutrality, taking into account new data of LULUCF net GHG absorption, published in Russia National Inventory Document [

70]. These scenarios will be actively discussed by different stakeholders, belonging to government, business and experts in coming months, before the new trajectory of carbon neutrality will be fixed in the strategic climate documents. The article specifically focuses on the role of managed forest ecosystems in achieving carbon neutrality and the ways of adapting forest management to low carbon development.

The strategic documents, include the Climate Doctrine of the Russian Federation (2023), Long term low-emission Development Strategy of Russia [

34], the LT LEDS Operational plan drafts, the Nationally Determined Contribution [

69], the draft law "On Amendments to the Forest Code of the Russian Federation" (Bill No. 566540-8)[

5], the new information on forests net carbon sequestration as per amended Russian NID, based on results of on-going strategic VIP GZ project

1. The documents were analyzed for the conceptual basis of the proposed measures, the correctness of their formulations, increasing the investment attractiveness (co-investment) in forest climate projects from the corporate sector, including based on existing trends in carbon markets and international experience of business involvement in climate projects.

2. Literature Review

In 2015 in the framework of the Paris Agreement 195 countries committed to set a global goal to achieve carbon neutrality in the second half of the XXI century. Over the past 2-3 years, there has been a sharp surge in publications on ways and approaches to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050-2060 [

8,

28,

57,

58,

82]. An important segment of this discussion is the potential role and importance of carbon absorption by natural ecosystems, primarily forests, including within the framework of Nature Based Solutions to climate change projects both on a global scale [

39,

65,

75] and within ambitious projects within the framework of South-South cooperation [

85], as well as at the national level – in Russia [

45,

46,

52,

53,

60], China [

72,

76,

77,

78], the European Union [

29,

33] and developing countries [

41,

64], up to the level of individual industries [

10] and companies.

It should be noted that estimates in the “Land use, land-use change and forestry” (LULUCF) sector are characterized by relatively high uncertainty ranges. Thus, while GHG emissions in the energy sector are estimated, as a rule, with an uncertainty of less than 5%, in the LULUCF sector carbon dioxide fluxes usually have an uncertainty of ±20-30%, and methane and nitrous oxide emissions of a few hundred percent. Therefore, there is a significant risk of manipulating estimates in this sector to present the best result in the field of mitigation of different countries.

On the other hand, country reporting on anthropogenic GHG emissions and absorption should, first of all, provide incentives for countries to step up efforts to further reduce emissions and increase absorption [

52]. Therefore, it may not fully coincide with scientific estimates of the annual GHG balance of all ecosystems of countries. At the moment, uncontrolled human fluxes of GHG from the melting of permafrost in the Arctic zone are not included in carbon reporting, however, if a decision is made to include them, this may seriously affect the GHG balance in the LULUCF. In particular, this may reduce incentives to fight forest fires due to the disparity in the size of these fluxes.

It has been shown that due to Canada’s GHG reporting approach may lead to climate mitigation policies that are ineffectual or detrimental to reducing net carbon in the global atmosphere [

6]. Until recently, the data showed that remote-sensing estimates to quantify carbon losses from global forests are characterized by considerable uncertainty and we lack a comprehensive ground-sourced evaluation to benchmark these estimates [

39], although satellites have detected a global increase in emissions from forest fires [

83,

84]. Climate change leads to a significant increase in fire risk in forests, especially in areas with a sharply continental climate (Siberia, Russian Far East). Under the conditions of the predicted increase in summer temperatures and adverse weather events, a further increase in the flammability of forests can be expected [

35,

36], respectively, forest areas of Siberia, which were previously considered the leading net carbon sinks of the atmosphere, may become a net source of GHGs in the future [

12,

26,

32]. In addition, many researchers analyze the carbon balance considering only data on carbon dioxide (CO2), without considering other GHG types (the first of all – methane CH4) in the carbon balance.

Russia's carbon neutrality and ways to achieve it

The goals of achieving carbon neutrality in Russia were fixed in the Decree of the President of the Russian Federation No. 812 of October 26, 2023, "On approval of the Climate Doctrine of the Russian Federation". According to the LT LEDS, Russia will strive to achieve carbon neutrality no later than 2060.

Inertial and target development scenarios are embedded in LT LEDS adopted on October 29, 2021. The inertial scenario did not lead to carbon neutrality on the planning horizon, so the target scenario was taken as a basis, which guaranteed the achievement of carbon neutrality by 2060. It identifies ensuring Russia's competitiveness and sustainable economic growth in the context of global energy transition as a key task. The implementation of the target scenario will require investments in reducing GHG emissions in the amount of about 1% of GDP in 2022-2030 and up to 1.5-2% of GDP in 2031-2050. The main investments in decarbonization are foreseen in energy sector, steel and aluminum sector, cement production, chemical and fertilizers industry as they are responsible for almost 75% of overall GHG emissions. These costs are based on current levels of spending on low-carbon technology development, equipment procurement and changes in supply and distribution chains. The decarbonization process includes measures to support the introduction, replication and scaling of low- and carbon neutral technologies, stimulating the use of secondary energy resources, changes in tax, customs and budgetary policies, the development of green finance, conservation and increase the absorption capacity of forests and other ecosystems, support for capturing and utilization technologies of greenhouse gases. Under the target scenario, economic growth will be possible with a reduction in GHG emissions: by 2050, their net emissions will decrease by 60% from the level of 2019 and by 80% from the level of 1990. Following this scenario will allow Russia to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060.

Drafts of the Operational plan of the Long-term low-emission Development Strategy.

The first draft of the action plan (operational plan) for the implementation of the LT LEDS (LT LEDS Operational plan) was prepared in February 2022 by the Ministry of Economic Development of the Russian Federation and was actively discussed at various professional venues. The second draft of LT LEDS was also submitted for discussion on professional venues, for example, at the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs Climate Forum in February 2024. The structure of the document consists of 6 key blocks: regulatory measures, industrial modernization, increased absorption and climate projects, energy, technological innovations, international cooperation. The main tools are to reduce the carbon intensity of the economy and increase the absorption capacity of Russian ecosystems. The plan includes about 170 activities in key carbon-intensive sectors of the economy. Minister of Economic Development M. Reshetnikov noted in his speech that the focus of the Ministry is the carbon footprint of products. It is important not only to implement climate projects: market participants must learn how to assess the carbon footprint of their products. First of all, these are issues of carbon pricing.

The role of Russian forests

The Russian forests occupy about 1/5 of the total forest area of the Earth. Forest resources are one of the renewable natural resources but forest management is not sustainable due to pioneer type of forest management in some areas, increasing forest fires and forest pest. GHG emissions from forest ecosystems occur mainly because of forest fires and logging. Forests have exeptional role in Russia LULUCF sector, as they actually absorb 90% of GHG in the whole LULUCF, as per Russian national inventory document (NID) 2024. Achieving the maximum possible absorption capacity of forests, noted in the Russian NDC, can be ensured through the intensification of the measures to reduce emissions and increase absorption in managed ecosystems, including by reducing GHG emissions resulting from logging and forest fires. Another potential measure aimed at increasing the area of forests and increase their productivity (accumulation of biomass) through active forest management and effective reforestation. In the case of methodological improvements, both the basic level of net absorption and target indicators should be recalculated, while the planned effect of mitigation measures reflected in strategic documents should be recalculated accordingly. This approach is reflected in the methodological recommendations of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and is called time series consistency on GHG emissions and sinks [

22].

Methodological consistency of time series is a central element of decarbonization strategies and makes it possible to correctly track the effectiveness of emission reduction measures at the national level. All estimates of emissions in the time series should be performed in a consistent manner, that is, the time series should be calculated using the same method and data sources for all years. The use of different methods and data in a time series can lead to erroneous estimates and conclusions, since in this case the estimated emission trend reflects not only actual changes in emissions or absorptions, but also the nature of methodological improvements [

22].

The achievement of the goals of the Paris Agreement and the global reduction of anthropogenic net GHG emissions into the atmosphere should be ensured through the implementation of appropriate mitigation measures and assessed based on the principle "as atmosphere sees". It is our point of view, that in the absence of methodological corrections between the baseline and target indicators of national low-carbon strategies, the reductions announced by the countries become dubious, because the atmosphere "does not see them". In reality, the fluxes have not changed due to the fact that we estimated them more accurately. That is why, when implementing the Paris Agreement, their stated national commitments to reduce emissions should be seen as primary national commitment.

Russia NID 2024 changes of net absorption in LULUCF comparing NID 2023

Russia NID 2024 was approved and published in November 2024. Its LULUCF net absorption data are significantly different, then NID 2023 and earlier NID data.

As it mentioned in the section P.6 of Russian NID 2024, the “the inventory was developed, in particular, using the results obtained during the implementation of the National Innovation Project ‘Unified National System for Monitoring of Climate Active Substances’ (VIP GZ). In this inventory, recalculations and improvements of GHG emissions and removals were made35, including those related to the methodologies of calculation estimates. The reasons for the changes in a number of indicators include the introduction of new national emission factors derived from the VIP GZ project” [

70] - (

Table 1).

According to the target scenario of LT LEDS 2021, net absorption in the LULUCF sector should increase to the level of 1200 Mln t CO2-eq. per year by 2050. To achieve zero emissions by 2060, the volume of absorption in LULUCF must correspond to the residual volume of emissions, i.e. 1200 Mln t CO2-eq. per year. Based on NID 2023 data that means an increase in net absorptions in LULUCF from about 548 Mln t CO2-eq. per year (in the period 2018-2021) to 1200 Mln t CO2-eq. level in 2050, or increase in 652 Mln t CO2-eq. per year. In this assessment, we have not yet considered the absorption effect due to the possible implementation of Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage (CCUS), Direct Air Capture and Storage (DACS) and other carbon direct removals (CDR) projects in the Russian Federation due to absence of official data on CCUS and other CDR projects in Russia.

According to the National GHG Inventory Document 2024 [

70], net absorption in LULUCF is equal to 1081 Mln t CO2-eq. (average in 2018-2022). To achieve carbon neutrality target in Russia LT LEDS, equal to 1200 Mln t CO2-eq., the increase of net absorption in LULUCF should be much less ambitious, than based on GHG inventory 2023 data, and should be equal to 119 Mln t CO2-eq., instead of 652 Mln t CO2-eq., or 5,5 times less.

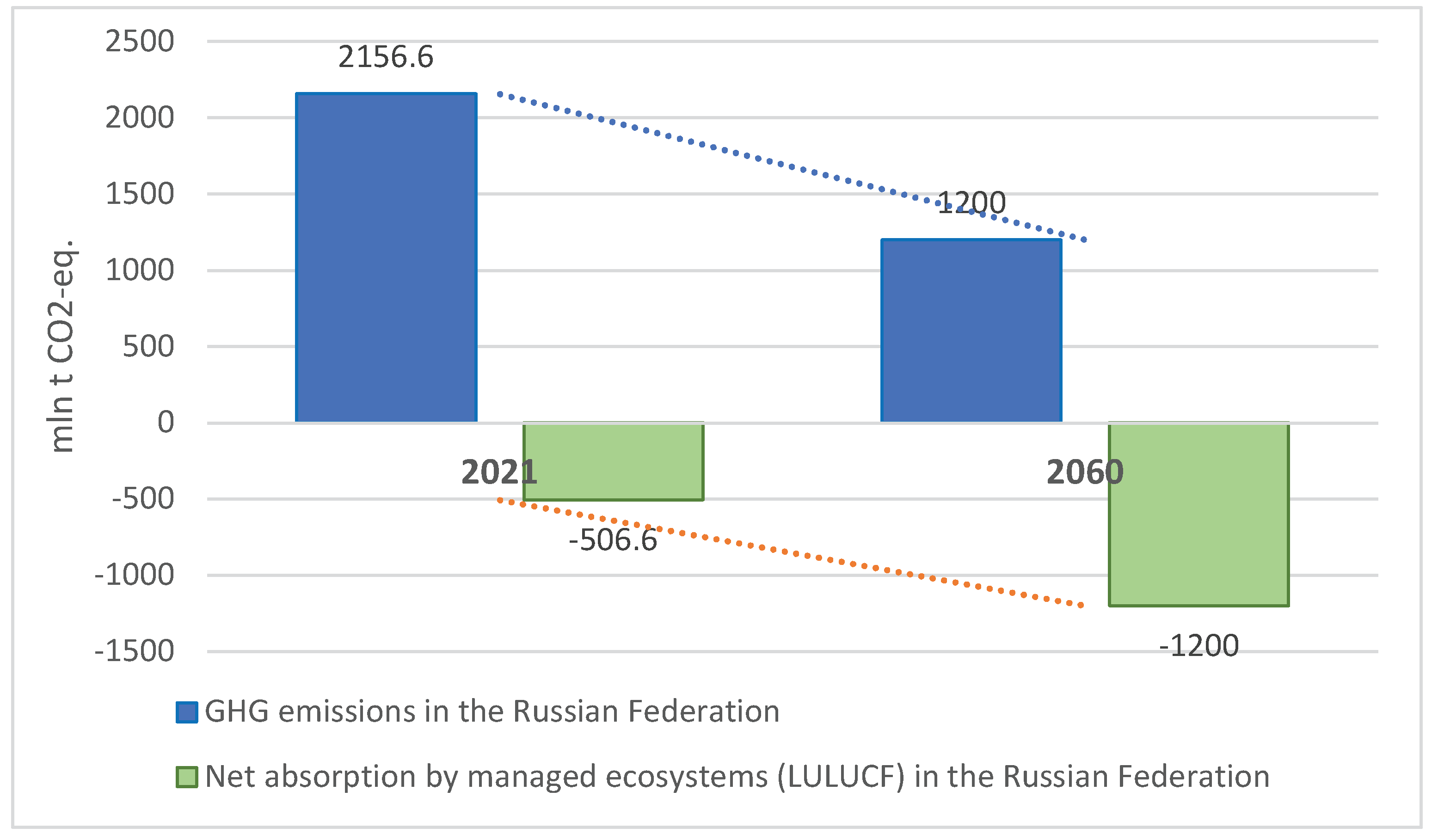

In the LT LEDS 2021 Russia carbon neutrality scenario, based on GHG Inventory 2023 data, emissions should be reduced from 2156,6 Mln t CO2-eq. (emissions of 2021) to 1200 Mln t CO2-eq., that mean that technological decarbonization will be equal to 956,6 Mln t CO2-eq. The absorption should increase from 506,6 Mln t CO2-eq. (absorption of 2021) to 1200 Mln t CO2-eq. (

Figure 1) The ratio between technological decarbonization and increase of net absorption in LULUCF is equal to 1,38 (956,6/693,4 Mln t CO2-eq.). This is usually high ratio for industrialized country with powerful energy sector in favor of GHG net absorption in LULUCF by managed ecosystems.

The new LT LEDS Russia carbon neutrality scenario based on updated NID 2024 data is not yet elaborated. The expert discussion about amendment of LT LEDS indicators in achieving carbon neutrality is starting now.

If the ambition to increase net absorption in LULUCF up to 1200 Mln t CO2-eq. will not change as per LT LEDS 2021 scenario and the net absorption in LULUCF is equal to 1081 Mln t CO2-eq. (average in 2018-2022), that will keep the technological decarbonization equal to 956,6 Mln t and net absorption in LULUCF increase will be 119 Mln t. That will keep ratio between technological decarbonization and increase of net absorption in LULUCF equal to 8 (956,6/119 Mln t CO2-eq.). This ratio is more or less typical for industrialized countries with powerful energy sector and vast LULUCF sector (USA, Canada).

3. Materials and Methods

Before 2024 Russian national GHG inventories were based on general IPCC reporting principles and approaches for GHG inventories. In 2022, the significant innovative project of national importance "Unified National Monitoring System of Climatically Active Substances" (VIP GZ) was launched with the aim to amend indicators and methodologies of GHG emissions and absorption. VIP GZ project was supervised by the Ministry of Economic Development of Russia. The results of the project should allow to obtain objective data on regional climate change, GHG fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems, including the absorption capacity of Russian ecosystems. Within the framework of VIP GZ, the scientific consortium "RITM Carbon" provided detailed assessment of carbon stocks in forests and other terrestrial ecosystems, prepared a forecast of the dynamics of the main carbon pools and GHG fluxes under different scenarios of land use and climate change. A monitoring network was launched to assess carbon stocks and its absorption in forests and other terrestrial ecosystems in Russia.

Within the framework of the VIP GZ a combined approach to the assessment of carbon removals in forests was developed. In this case, the zoning of the territory of the Russian Federation was performed, providing an optimal combination of remote sensing data from space on the basis of data from the information-analytical system ‘Carbon-E’ (

http://carbon.geosmis.ru/) [

3,

4] and State Forest Inventory (SFI) data on the basis of 69.1 thousand sample plots during 2007-2020 according to the criterion of maximum accuracy of the obtained estimates of carbon budget parameters in the country's forests. Zone 1 - using predominantly remote sensing data, it includes large subjects characterized by low density of SFI sample areas and significant areas of hard-to-reach territories. Zone 2 - using predominantly ground survey data (SFI, statistics of the Federal Forestry Agency), it includes most of the regions in the European part of the Russian Federation, in the south of Siberia and the Far East.

Data on the distribution of areas and reserves of plantations by species, bonitet and age were obtained from the SFI data. The current growth was calculated based on the normative-reference base of growth and productivity of forests in Northern Eurasia using modal growth patterns of modal stands [

63]. The models provide the opportunity to take into account regional characteristics, species composition, age and bonitet of stands. Similarly, using that set of models [

61] the stocks of different fractions of dead wood (dry wood, dry branches, dead wood, stumps) are estimated in 1-year increments. Current forest growth is estimated as the difference between the wood stocks at the current age and one year ago.

Refined Biomass Expansion Factors (conversion factors) were used for forest carbon budget calculations [

55], that take into account as input parameters the age, bonitet and completeness of stands of a particular dominant species. Taking into account that 50 per cent of dry biomass is carbon [

23], annual changes in carbon stocks in the phytomass of plantations per 1 ha can be estimated.

The area of forest loss due to fire is also determined using a combined approach: in zone 1, remote sensing data are used [

37], in zone 2 - statistics of the Federal Forestry Agency. Forest carbon losses during harvesting are determined on the basis of actual data on harvested wood stocks according to Federal Forestry Agency data.

The areas of managed forests have been clarified: based on remote sensing data, the areas of sparse woodlands that are part of managed forest lands but were not previously accounted for in the GHG inventory due to the lack of activity data have been included. Their area over the period 2013-2022 decreased from 23.7 to 19.5 million hectares, which is explained by the transition of part of sparse forests to forest covered land. In addition, from 2019, managed forest land additionally includes 44.5 million ha of so called “reserve forests” where additional fire control and suppression activities are carried out. And the managed forests include former collective farm forests located on agricultural lands. According to the Ministry of Agriculture of Russia the area of collective farm forests totaled 4.0 million hectares.

The first results of VIP GZ project, considered the results of new SFI data, indicate that a significant reassessment of the net absorption of CO2 by managed forests has been made.

4. Results. Possible Scenarios to Achieve Carbon Neutrality in the Russian Federation in the New LT LEDS

After approval of new NID 2024, it is possible to expect that LT LEDS target scenario to reach carbon neutrality in 2060 will be amended and new LT LEDS will be tentatively endorsed in coming months

2. The previous LT LEDS 2021 scenario was based on assumption, that absorption in LULUCF will be increased on 693,4 Mln t CO2, while technological decarbonization will be equal to 956,6 Mln t CO2-eq. (

Figure 1). It worth to mention, that according the authors assessment [

46] the LT-LEDS 2021 ambition to increase absorption in LULUCF is mainly based on the idea, that existing in 2021 government assessments and registers (e.g. State forest register by Federal forest agency etc.) underestimates absorption by forests and other ecosystems, and the new science-based assessment of GHG absorption will lead to significantly higher figures in absorption. That assessment was fully supported as the result of VIP GZ project implementation - absorption in LULUCF increased almost two times from 548 Mln t CO2e to 1081 Mln t CO2e in NID 2024. VIP GZ re-assessment of ecosystem absorption capacity contributed to almost 86% of LT-LEDS planned absorption growth by 2050 in LULUCF.

The two “extreme” potential options will define the framework for the re-calculation of target scenario in the new LT LEDS for achieving carbon neutrality:

1) The ambition of LT LEDS 2021 to increase net absorption in LULUCF will remain unchanged (-693,4 Mln t CO2-eq. in 2060 comparing to 2023) while technological decarbonization will decrease.

2) The ambition of LT LEDS 2021 to decrease emissions through technological decarbonization will remain unchanged (-956,6 Mln t CO2-eq. in 2060 comparing 2023) while net absorption in LULUCF will decrease.

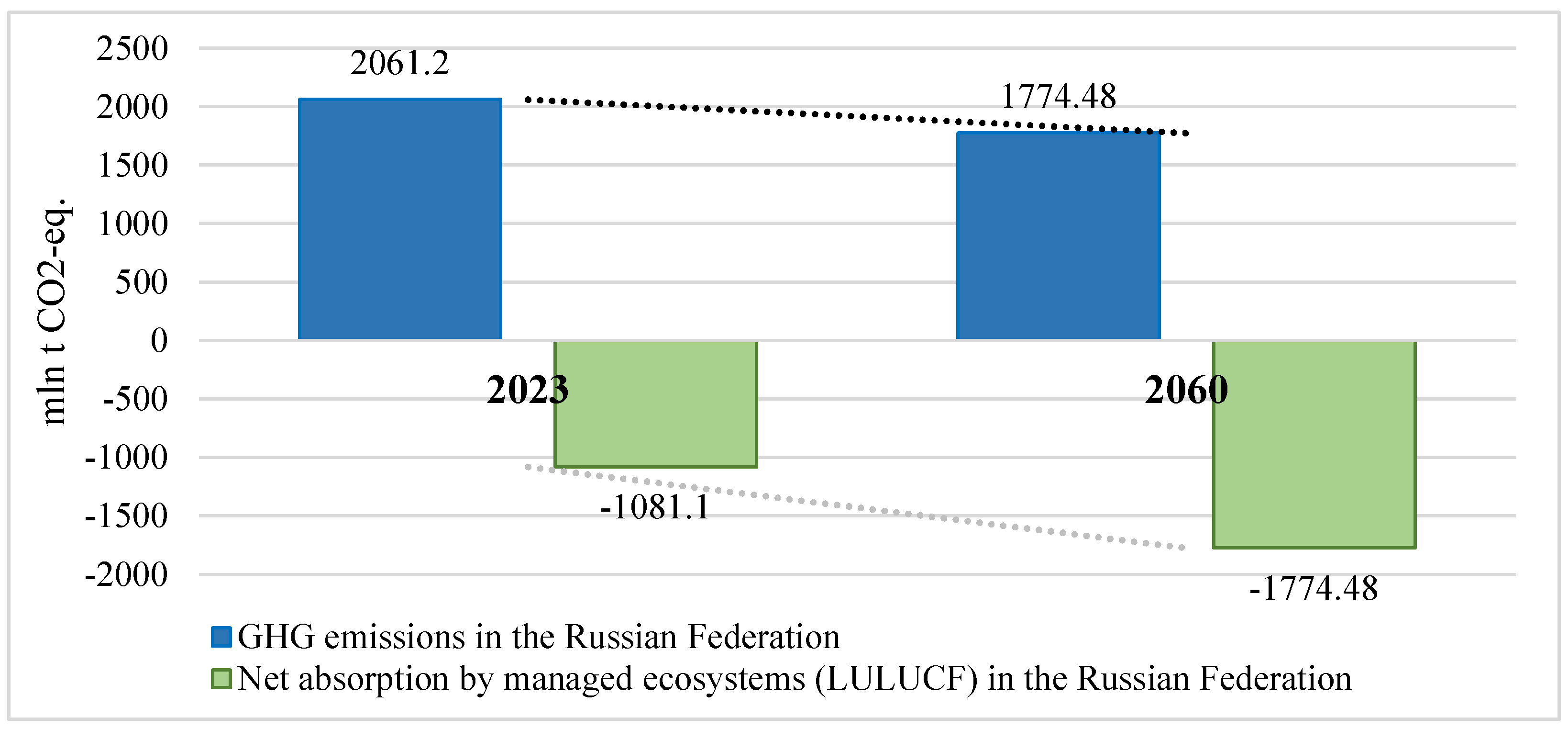

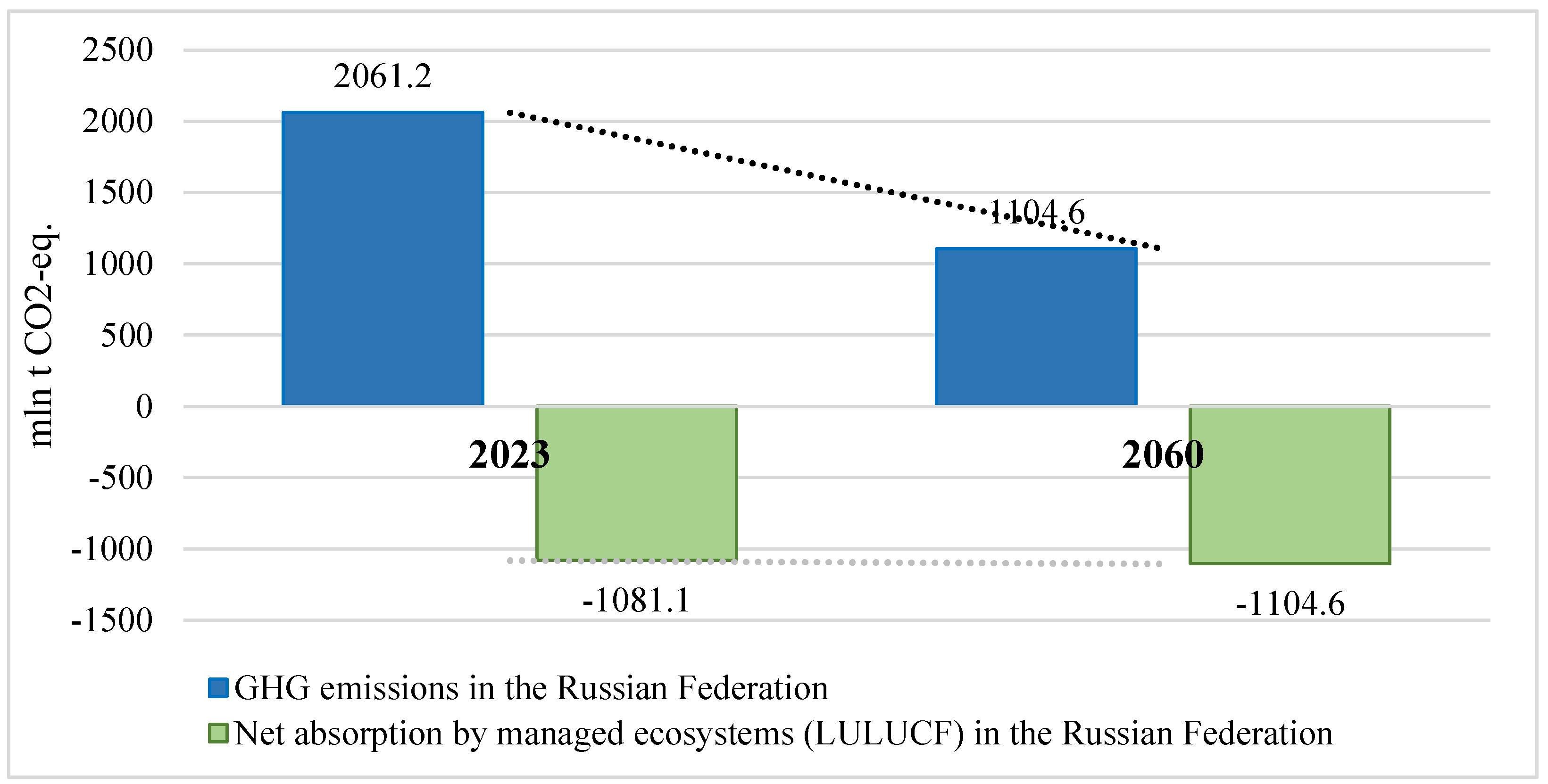

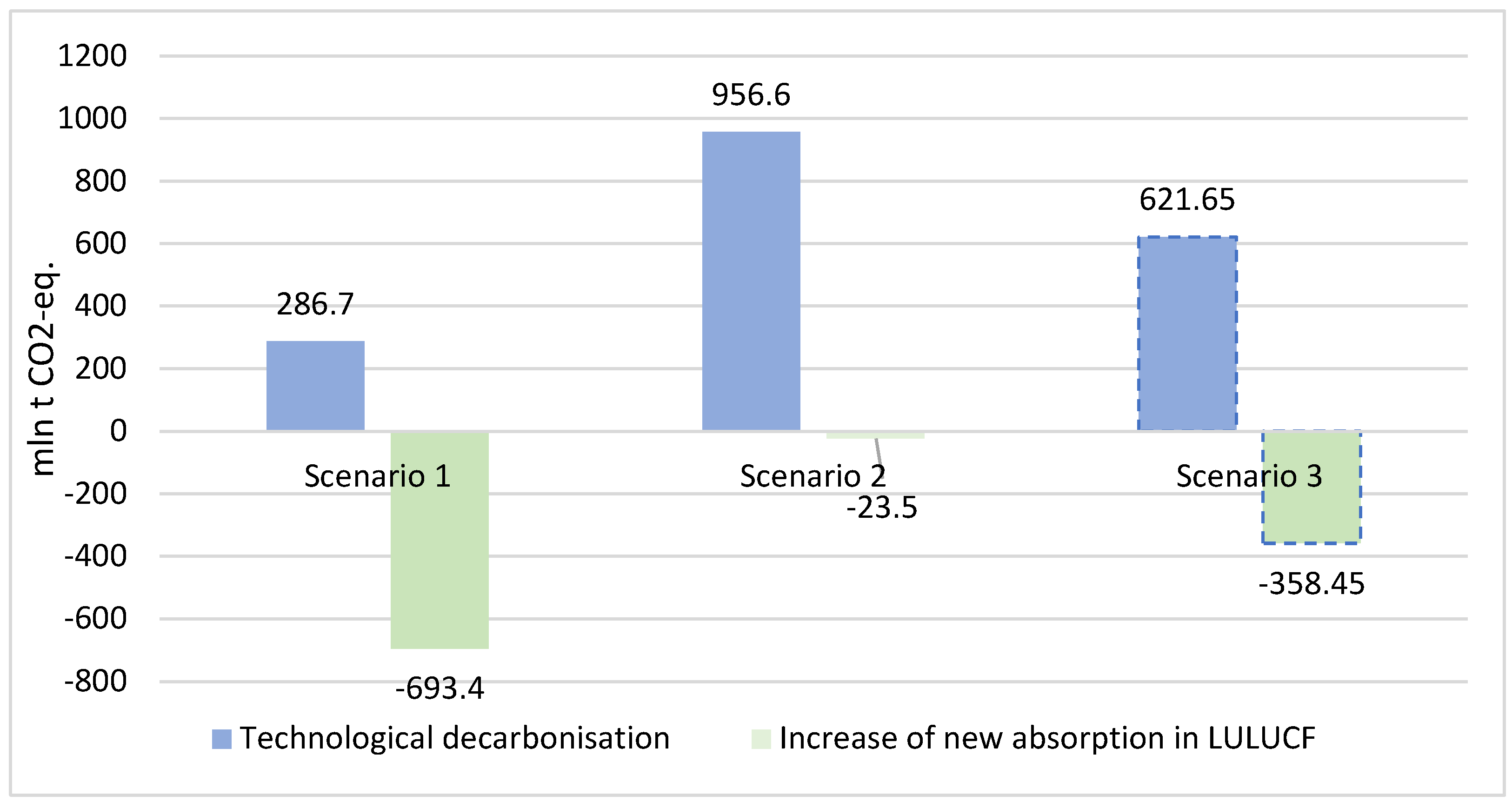

Based on that, three possible scenarios of reaching carbon neutrality in target scenario in the new LT LEDS are presented below with assumption of GHG emissions in 2023 - 2061,2 Mln t CO2-eq. (average in 2018-2022) and GHG net absorption by LULUCF in 2023 - 1081,08 Mln t CO2-eq. (average in 2018-2022)

Scenario 1. In this scenario the increase of net absorption in LULUCF will remain as planned in LT LEDS 2021 – 693,4 Mln t CO2-eq., while technological decarbonization will decrease from 956,6 to 286,7 Mln t CO2-eq (2061,2-1081,1-693,4), or almost 2,8 times from LT LEDS 2021 decarbonization target (

Figure 2).

Scenario 2. In this scenario the level of technological decarbonization will not change (956,6 Mln t CO2-eq.) while net absorption in LULUCF will decrease from 693,4 to 23,5 Mln t CO2-eq (2061,2-1081,1-956,6), or almost 30 times from LT LEDS 2021 decarbonization target (

Figure 3).

Scenario 3. Will be a mixt scenario between Scenario 1 and 2. This scenario is seen as the compromise between “extreme” scenarios 1 and 2. This scenario is presented below in a very simplified manner as average figures between scenarios 1 and 2. The basis of comparison are technological decarbonization and net absorption ambitions (change of net carbon balance) in 2050 comparing with 2023 (

Figure 4).

Scenario 1 will greatly simplify the achievement of carbon neutrality by the largest GHG emitters, provide time and opportunities for the gradual restructuring of energy supply systems and industry in the country. At the same time, analyzing possible ways to increase net uptake in the LULUCF sector, given the projected increase in boreal forest burning as a result of climate change, shows that the financial costs of forestry should significantly increase from current levels [

40]. The total funding for the federal project "Forest Preservation" within the framework of the new national project "Environmental Well-Being" will amount to 71 billion rubles by 2030. This is 70% more than was allocated for the previous five years [

38]. According to information from the Ministry of Natural Resources and Ecology Funding for fighting forest fires in Russia will increase by 5.3 billion rubles to 20.2 billion in 2025 [

48]. Thus, the goals for the LULUCF sector to increase absorption volumes remain unrealistically high and leave a high burden on the state departments responsible for implementing the program to increase GHG absorption by forests and agricultural lands (the Ministry of Natural Resources of the Russian Federation, the Federal Forestry Agency, and the Ministry of Agriculture of the Russian Federation) (

Figure 1).

Scenario 2 will decrease burden from Ministries, responsible for implementing net absorption programs in LULUCF, but will keep relatively high decarbonization levels for business, municipalities and non LULUCF Ministries, such as Ministry of Energy and others. In this scenario it is possible to anticipate significant resistance from mentioned entities.

Scenario 3. The more realistic scenario can be a combination of scenario 1 and 2. In this option it is possible to determine a more realistic level for increasing absorption in LULUCF, considering the real potential of adaptation measures and climate projects, and the corresponding adjustment of emission reduction targets by industry and other emitters. In this case, the impact on the LULUCF sector will be achievable in practice, but requiring the implementation of a complex set of management, adaptation and mitigation approaches. At the same time, the burden on the relevant GHG emitters in the energy sector and industry will be higher, than in option 2, but lower, than in option 1. This option is the most preferable from the point of view of the authors. It requires a scientifically based approach to assessing the practical potential of mitigation, adaptation and management measures in the LULUCF sector of the Russian Federation for the coming decades. This approach will require both evaluation of possible technological and policy options to define cost-effective potential of mitigation and adaptation.

The authors suggest that the main discussion on the decarbonization of the Russian economy in the coming years will unfold around these options of low carbon development. In our opinion, if the third option is adopted, it is possible to define realistic goals for achieving carbon neutrality in all sectors of the economy, including forestry, and systematically achieve them within the time frame specified in the LT LEDS. Global business decarbonization standards (SBTI Net Zero, ISO 14068, etc.) are on the side of the third option, which limits the use of offsets for decarbonization in energy and other industries. The discussion on decarbonization should be continued, both at the level of the expert community and interested ministries and departments, unions, and business organizations.

It is known that reducing GHG emissions through technology is quite an expensive measure. In general, approaches related to the implementation of nature-based climate projects are more financially attractive. The role of managed forests in net carbon sequestration in LULUCF is around 90%, as per NID 2024. Non-managed forests also absorb CO2 from the atmosphere. Romanovskaya and Korotkov [512] estimates that 80% of net absorption by managed and non-managed ecosystems are done by forests.

In the research of A.A. Romanovskaya [

53] it is noted that the forest area of Russia is increasing (by 15.2% in 2016 compared to 1990) mainly due to the actual transition of unused agricultural lands to non-managed forests. The reduction in logging volumes on managed forest lands from 1990 to 2010, against the background of an increase in the area of actively GHG-absorbing young forests at the site of extensive Soviet-era logging, led to an overall increase in the absorption of GHG by forests. But after 2010 the annual volume of net absorption in forests stopped decreasing and began to grow due to an increase in logging and in the area passed by forest fires [

81].

4.1. Reaching Carbon Neutrality and Forest Fires Problem

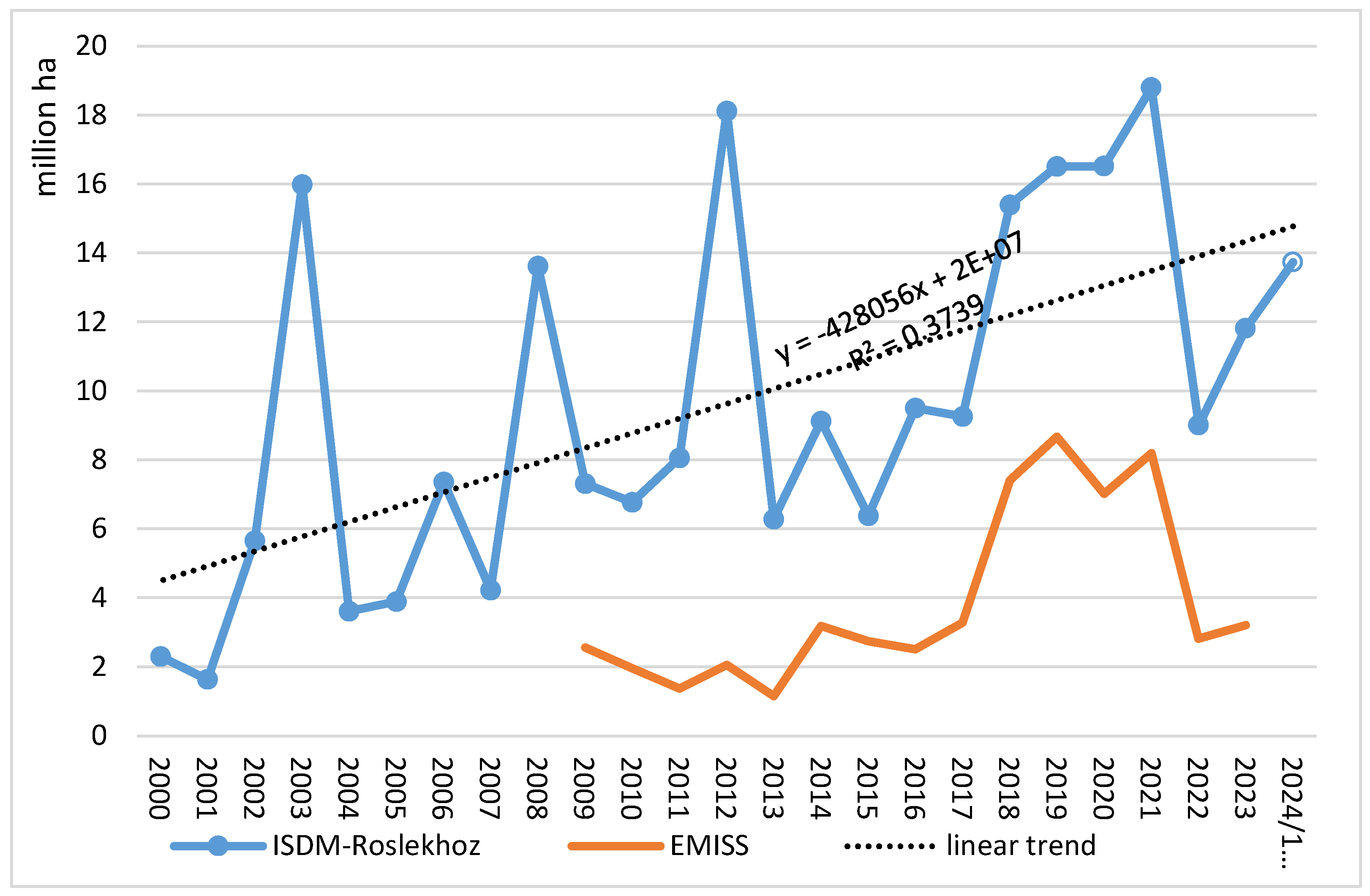

A number of studies have revealed a high potential for reducing emissions in the prevention of forest fires (220-420 million tons of CO2-eq. per year). At the same time, despite a significant increase in funding in the field of forest fire control in the last 10-15 years, the area of forests passed by fires has only increased: from about 4 million hectares in 2000 to about 13 million hectares in 2023, according to the Forest Fires Remote Monitoring Information System (ISDM-Rosleskhoz) of the Federal Forestry Agency (

Figure 5). Without measures to reduce the area of forest fires and limit logging, a subsequent reduction in net GHG absorption on managed forest lands is expected [

12,

26,

50] and a further increase in the flammability of forests [

35,

36].

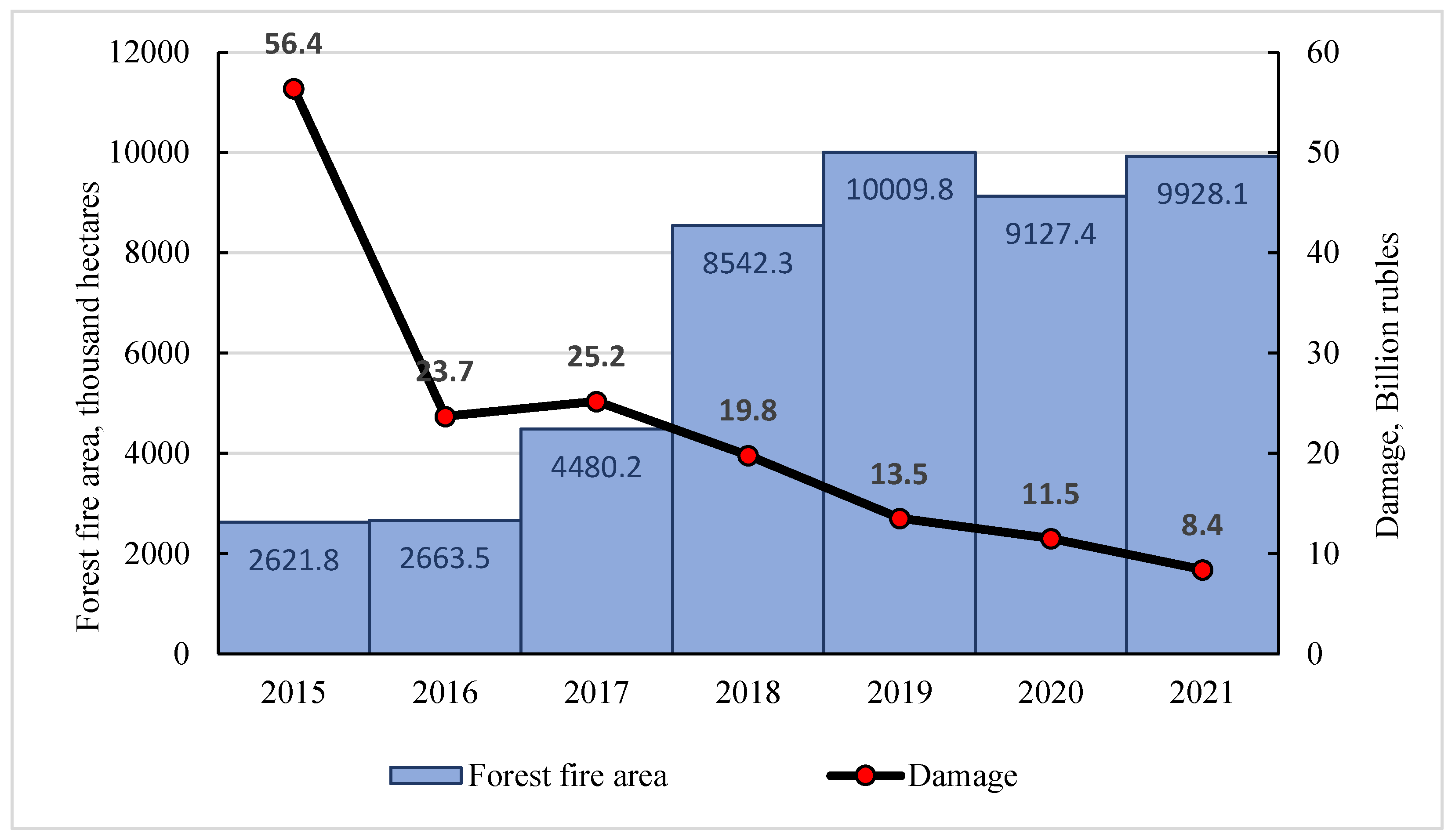

A significant problem in accounting for the dynamics of carbon dioxide emissions during forest fires is the intention of forest authorities to limit or cut off the supply of information on forest fires, which was revealed by auditors of the Accounts Chamber of the Russian Federation (

Figure 6). The reporting of the Ministry of Natural Resources and the Federal Forestry Agency plays up the alleged decrease in the economic indicator of "damage" from forest fires during the period since 2000, which simultaneously masks a parallel sharp increase in the area of forest fires in the country, especially in Central Siberia, Yakutia and Russian Far East [

12,

26,

27,

50]. The economic "damage" from fires is determined by the cost of lost of commercial value of timber, which is minimal in the regions most far from the transport and logistics infrastructure and maximal in the regions of the European territory of Russia with the most developed road infrastructure, a high proportion of leased forests for the harvesting and a proven forest fire fighting system.

4.2. Estimates of the Carbon Balance in Russian Forests

Many authors are assessing the carbon balance of forests and its main components [

17,

50,

52,

59]. For example, Shchepashchenko and co-authors [

54] estimates the net absorption of Russian forests in 1988-2014 at an average of 354 million tons of C per year (in living biomass), which corresponds to 1,298 million tons of CO2. This is significantly higher than the value indicated in the National GHG Inventory in 2023 and before. The difference arises due to the use of data from the first cycle of the State Forest Inventory (SFI) ended in 2020, in combination with remote sensing data (satellite surveys) instead of data from the State Forest Register (SFR). The SFI data surpass on 39% the SFR data on wood reserves in forests [

54]. In the research [

18,

24] the absorption capacity of forests on former agricultural lands is estimated to be about 7 times higher than on forest lands, which is explained by more favorable conditions for forest growth on more fertile former agricultural soils. The difference in net absorption is also due to the fact that only managed forest ecosystems, which occupy about 82% of the country's forest land area, are included in the National GHG Inventory.

Various publications and estimates [

16,

52,

59] show that the approach based on traditional forest inventory has a significant drawback – difficulties in accounting for the processes of succession and adaptation of ecosystems to new conditions. Considering the average age of forest census data in Russia at 25-30 years or more, many old growth forests have already been transformed into young or middle-aged ones due to natural forest growth cycles. Similar results at the local level have been demonstrated by many researchers. Thus, for the Central Forest Nature Reserve, as a result of natural processes and adaptation to climate change, according to remote sensing data, over 30 years, 41% of forests without human influence or major catastrophic events have changed their leading species and only 21% of old growth forests have retained their characteristics [

47].

It is important to note the divergence of trends – stationary models [

81] often give a predicted decrease in the absorption capacity of forests, whereas studies of global and regional scales based on remote sensing data show an increase in the growth rate of biological products and adaptation of forest ecosystems to an increase in CO2 content in the atmosphere in the coming decades. Models based on remote data and measurements of FLUXNET systems, on the contrary, often tend to overestimate the absorption capacity of landscape cover [

31,

59]. Thus, the World Resources Institute model of global carbon fluxes in forest vegetation [

21] gives an average absorption of 4,320 Mt of CO2 per year for the territory of Canada over 20 years (and even more for the territory of the Russian Federation). For Russia, models based on the use of remote data and measurement of FLUXNET systems form a range of 1,800-2,500 Mt CO2 per year. It should be noted that the measurements of flows by the eddy covariance method are characterized by the greatest uncertainties. In addition, such estimates do not consider the lateral carbon fluxes associated with logging, leaching of soil carbon and loss with erosion. The publication, based on a combination of data from the first cycle of the GIL in 2007-2020 and remote sensing data [

54], gives an “intermediate” estimate of ~1,270 Mt CO2 per year. Similar estimates were obtained in the article by Romanovskaya and Korotkov [

52] in the case of accounting for all forests, however, these estimates require clarification of the contribution of litter and soil pools to the carbon balance of forests.

However, only the methodology of the National GHG Inventory has been repeatedly verified by the experts of UNFCCC when reviewing the national reports of the Russian Federation in the UNFCCC and therefore is considered official. A recent study by a representative international team of authors [

39] showed that despite regional variation, the predictions demonstrated remarkable consistency at a global scale, with only a 12% difference between the ground-sourced and satellite-derived estimates. In this regard, it should be noted that the study of the World Resources Institute [

21], which estimates of the Net Carbon Balance for Russian Forests 1400+ Mt C per year (

Table 2), which appears to be significantly overestimated compared with both official data from the Russian SFI and recent publications data (4-4.4 times higher than in Schepaschenko et al. 2021 and in Romanovskaya, Korotkov 2024).

4.3. Legal Regulation of Climate Projects in the Forest Lands

In the spring of 2022, the Ministry of Natural Resources of the Russian Federation initiated amendments to the Forest Code of the Russian Federation and Article 9 of Federal Law No. 296 "On Limiting Greenhouse Gas Emissions" to support the implementation of climate projects in the field of forest relations (forest climate projects). After two years of discussion, significant adjustments were made to the final version of the draft law. Draft law No. 566540-8 "On Amendments to the Forest Code of the Russian Federation (in order to create legal grounds for the implementation of climate projects in forests on the Territory of the Russian Federation)" was submitted for consideration to the State Duma of the Russian Federation in March 2024 and finally adopted on December 26, 2024.

The main criticisms during the discussion of the draft law were related to the fact that the Ministry of Natural Resources of Russia initially suggested to classify only those climate projects in forests that provide for the implementation of works on protection, reforestation, afforestation, ensuring the reduction (avoidance) of greenhouse gas emissions or an increase of GHG removal (

Table 3). This contradicts international practice, according to which up to 60% of carbon units can be provided by projects for the conservation and restoration of ecosystems, and no more than 40% by projects to improve ecosystem management [

19]. On the other hand, the accumulated criticism of projects to preserve forests from deforestation and the objective difficulties of verifying the additionality of such projects and the baseline may serve as an argument in favor of the prematurity of including such projects in the forest climate projects of the Russian Federation.

Significant additions were made to the draft law "On Amendments to the Forest Code of the Russian Federation» before final approval, which make it possible to implement forest climate projects both on leased forest plots and on non-leased. The version of the draft law adopted in the first reading contains, according to the authors, a number of controversial points: the permissive nature of the implementation of projects in the forest fund by the Federal Forestry Agency (in general, it does not correspond to the world practice of implementing forest climate projects), as well as the possibility of non-agreement of the climate project if its purpose does not correspond to the "intended purpose of forests" (art. 66, paragraph 9). At the same time, the concept of "forest purpose" was defined in the 2006 Forest Code without considering the climate agenda. According to our assessment, there are projects at risk that are aimed at reducing emissions as a result of a reduction in logging, for example, projects for the voluntary conservation of forests of high conservation value (as they do not fully meet the intended purpose of operational forests) or projects for rewetting of drained peatlands in the forest fund – in the absence of obvious signs of fire danger on them.

4.4. Assessment of Measures to Increase Absorption and Stimulate the Implementation of Climate Projects in the LULUCF Sector in the Draft Operational Plan of LT LEDS

The draft LT LEDS Operational plan of June 2024 provides for an increase in absorption:

- −

Indicators of increased absorption of LULUCF on forest lands by the years up to 2030 (Section 3.1.1).

- −

Indicators of the total annual area of forest fires on forest fund lands, which are planned to be reduced by 2030 to 4.2 million hectares by 2030 compared to 10 million hectares in 2019 (Section 3.1.1).

- −

The stepwise quantitative result of the implementation of climate projects by 2030 in the amount of 20 million tons of CO2-eq., compared with 1 million tons in 2024 (Section 3.1.2).

- −

Focus on exploring the potential of agroforestry and regenerative agriculture for carbon storage and the implementation of measures and climate projects in this field (Section 3.2.1.1 and 3.2.1.2).

- −

Stimulating the implementation of climate projects (Section 3.2.2.), which is caused by low current business interest in the implementation of climate projects.

In general, the measures proposed by the LT LEDS Operational plan draft look quite logical, scientifically sound and consistent with world experience, for example, the role of agroforestry and protective afforestation measures has been increased. However, in our opinion, the last version of LT LEDS Operational plan is still needing some improvement. In particular, measures to assess the absorption capacity of forests and other ecosystems should be significantly adjusted and linked to the results of the VIP GZ project. It is planned that, based on the results of VIP GZ and an adjusted National GHG Inventory the accounting for forest absorption will allow all targets to be achieved “automatically”. However, it should be recalled that methodological refinements of the assessment of net absorption in the LULUCF sector cannot be considered mitigation measures and should lead to both a reassessment of the baseline (2019 in LT LEDS) and the target indicator. Unfortunately, as follows from the second version of LT LEDS Operational plan of VIP GZ, such a recalculation was not done, and the refinement effect of VIP GZ will be counted in National GHG inventory and other documents as an "absorption capacity increase".

The degree of elaboration of climate measures in LULUCF is different. If the agroforestry section shows a chain of actions aimed at achieving the desired result, including the development of an appropriate roadmap for agroforestry, then in terms of measures under the Ministry of Natural Resources and the Federal Forestry Agency, such a sequence is not visible. Some of the proposed indicators are debatable. For example, the planned area for reducing forest fires provides for a reversal of the trend towards increasing fires (Fig. 5), but it is unclear by what measures this change will be implemented.

As for climate projects to protect forests from fires, in the international methodology Verra VM0029 and by the Clean Energy Regulator of the Australian Government assigns only one type of forest fire projects – controlled burning (controlled fire-fighting burns during a less fire-hazardous period in order to prevent catastrophic fires during the peak of the fire-hazardous period). The inclusion of the methodology for the implementation of forest climate projects for the protection of forests from pests in LT LEDS Operational plan, as well as for the protection of forests from fires, in our opinion, requires longer discussion and elaboration, including due to the presence of polar opinions on their effectiveness among specialists and the lack of convincing world practice.

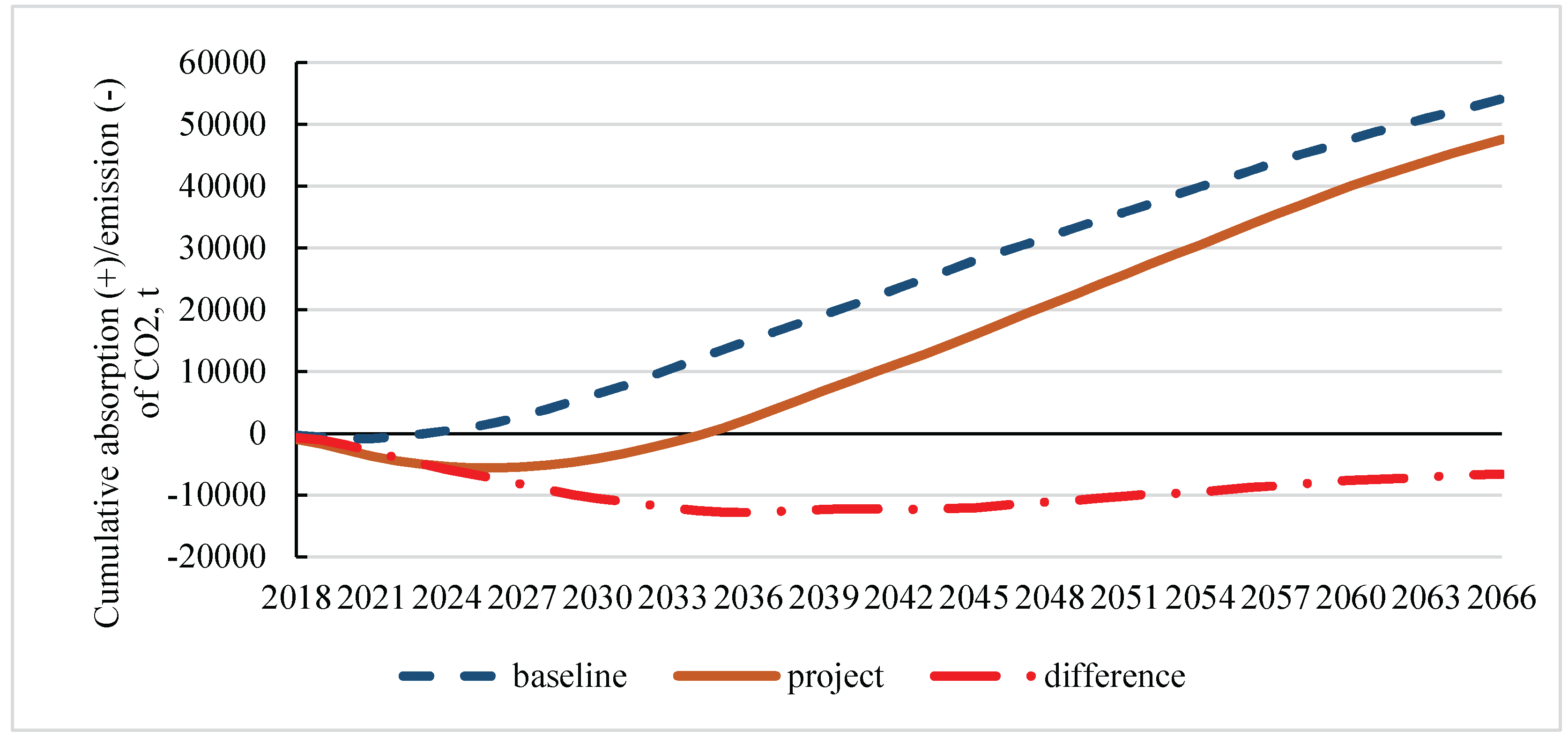

Reforestation and afforestation measures for the implementation of climate projects also raise questions. Reforestation projects in burned and cut down areas are often characterized by a negative carbon balance compared to the baseline of the project [

30,

56]. The natural afforestation in boreal forests is starting with a predominance of leaved species (birch, aspen, etc.) often leads to greater carbon absorption than the planting of coniferous forests required by the modern regulatory framework of the Russian forestry. The example of negative carbon balance of reforestation project in the Irkutsk Region is showed on

Figure 7.

At the UNFCCC Conference of the Parties in Glasgow in 2021, it was decided that the credit period for forest projects implemented under Article 6.4 of the Framework Convention is up to 15 years with the possibility of a maximum of two more extensions – that is, up to 45 years in total. Considering this factor, the effect of carbon sequestration measures through traditional forestry reforestation with coniferous monocultures in the Irkutsk Region and the Krasnoyarsk Territory is negative until about the age of 50. According to the work of [

56], only when the stand is over 50 years old, carbon accumulation in

Pinus sylvestris crops becomes higher than during spontaneous overgrowth. It can be assumed that most reforestation projects in the forest zone (the zone of natural overgrowth), focused on the cultivation of coniferous monocultures, will lose out to natural restoration, which occurs in most cases (except for poor sandy or rocky soils) by overgrowing with deciduous crops depositing 1.4-2 times more carbon than coniferous ones, or not have significant differences from it [

67].

Thus, reforestation by methods focused on the growing of only coniferous trees is not a reliable climate project without reorientation to deciduous and mixed ones with a maximum rate of carbon accumulation compared to coniferous monocultures. Due to the pronounced course of improving the quality of carbon units, this creates risks for a fair assessment of the value and quality of carbon units from Russia. The latter is especially important given the increasing criticism of carbon offsets for climate change mitigation [

25,

74]. It should be noted that the adoption of the Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation No. 665 of May 23, 2024, which made public the materials of all registered climate projects from June 1, 2024, allows us to count on ensuring transparency in the implementation of climate projects in Russia.

The approach of implementing climate projects only in leased forests has significant limitations: in total only about 15.2–15.4% of the forests of the State Forest Fund are leased for timber industry purposes in the Russian Federation in 2022-2023. Considering the sanctions and restrictions on the export of timber products, there are no significant prospects for the growth of the forest lease area. In order to maximize the potential of carbon sequestration by Russian forests, it is important to reorient the management of the country's non-leased forests (almost 85% of the Russian forest area) to increase their resistance to fires, reduce the flammability and increase carbon removal capacity of forests.

4.5. The Lack of Climate Indicators for the Implementation of Measures in the Draft LT LEDS Operational Plan

In the column "Expected result" in sections 3.2.1.1 and 3.2.1.2 of LT LEDS Operational plan, the results of climate measures are given in hectares, for example, the area of elimination of the pest outbreak, protection of forests from fires, etc. At the same time, section 3.2.2 gives the cumulative result of voluntary forest climate projects in the Russian Federation in million tons of CO2-eq. per year. In our opinion, the purpose of the measures in sections 3.2.1.1 and 3.2.1.2 should be to obtain a climatic effect to increase absorption or reduce emissions, therefore, the expected results in this section should further be linked to tons of CO2-eq.

Previously, the authors proposed a list of priority forest climate projects in Russia based on national and international experience, appropriate methods and features of forest management in the country [

44,

51]. Such projects are proposed for implementation, primarily on leased forest plots or on agricultural land.

We have made a forecast calculation of the yield of carbon units at a cost of production of less than

$30 per unit (1 ton of CO2) (

Table 4). The cost was estimated during the execution of contractual works for a number of Russian thermal power companies in 2021 with the participation of experts from the GFA Climate Competence Center.

According to recent studies, forest climate projects can provide up to 30% of the absorption of GHG necessary to contain global temperature increases within 1.5°C [

20,

49,

73]. At the same time, the cost of such solutions is in the range of

$10-40 per 1 ton of CO2-eq. It should be noted that there is a significant difference in approaches to decarbonization through measures in the LT LEDS Operational plan 2024 and in global practice. An analysis of research in the field of natural and climate solutions has shown that globally, projects for the conservation of ecosystems (forests) can bring the greatest effect, followed by projects for the restoration of ecosystems, and in third place – for better forest management. The absorption rate between them, respectively, is 2.1:1.2:1. At the same time, almost all the measures proposed in the draft LT LEDS Operational plan 2024, with the exception of afforestation, relate to better forest management and do not include projects for the conservation and restoration of ecosystems, with the exception of wetlands projects. But since deforestation in Russia is only a fraction of a percent of the area of forest land, the emphasis on sustainable forest management may be quite justified.

5. Discussion

How to increase carbon sequestration by Russian forests

Although there is a widespread perception among decision makers in Russia that due to the huge area and absorbing capacity of forests, the country should not significantly "invest" in decarbonization of industry and housing and communal services, the real picture of the dynamics of the carbon balance in forests and natural ecosystems of Russia is not so promising and positive.

Firstly, some forecasts of the carbon balance of forests indicate a reduction in its value by 2050 by 2.5-5 times compared to the current situation, depending on the projected volume of logging [

79]. Even if the current level of logging is maintained, a decrease in net forest absorption can be expected due to a decrease in the areas of actively absorbing young trees. This decrease is due to the different volume of logging in the USSR (around 400 mln m3/year) and in the Russian Federation (around 200 mln m3/year). The decrease of logging volume also means the decrease of areas for reforestation, and young forests absorb significantly higher volumes of CO2 than old forests.

Secondly, the area of burned forests is growing, which is recorded according to remote sensing data, and in the conditions of the predicted increase in summer temperatures and adverse weather events, further growth in forest fires can be expected. Accordingly, an increase in the volume of forest fire emissions is predicted [

51].

In our opinion, it is necessary to build a national decarbonization policy considering the high probability of a gradual decrease in net forest absorption from more than 1000 million tons of CO2-eq. in 2021 to about 300-400 million by 2050 [

81]. This will require both increasing efforts in terms of technological decarbonization and changing the priorities of the national forest policy, directing it not only and not so much to the development of logging as it is now, but also to radically increase carbon dioxide absorption by forests. The latter is also important regarding the fact that the cost of reducing emissions of 1 ton of CO2 through natural solutions is considered significantly lower than using technologies [

20].

To achieve carbon neutrality by 2060, it is necessary to reorient and reform forestry outside of forests leased for industrial purposes (more than 80% of the country's forest areas) to reduce the flammability and increase forest resistance to fires and increase the absorption of carbon dioxide by forests, instead of increasing the industrial stock and growth of coniferous wood. These tasks require a radical reform of the entire forestry system of the country and a change in the priority of forestry outside the territory of the forestry lease to increase the absorption and the term of carbon deposition by forests and all other types of natural and anthropogenic ecosystems in Russia, increase the role of natural reforestation and the formation of more fire-resistant multi-species plantations, edging previously created coniferous monocultures by deciduous plantings, etc. [

59,

60].

It is proposed as possible tools for the required changes (the list is not comprehensive):

- Complementing the federal project "Conservation of Forests" of the national project "Ecology" and the state program "Forestry Development" as the main instruments for financing forestry by the Russian Federation with indicators of quantitative estimates of GHG absorption within the framework of ongoing measures in the field of forestry funded from the federal budget, as well as to limit the requirements for the use of mainly coniferous seedlings in reforestation with a closed root system.

- In accordance with the Decree of the President of the Russian Federation No. 382 of June 15, 2022, set targets for the federal subjects of the Russian Federation to ensure a reduction in the area of forest fires by at least 50% from the level of 2021 and, accordingly, a reduction in emissions and an increase in forest absorption, within the framework of the prepared LT LEDS Operational plan. This will allow forestry to make a quantitative contribution to achieving carbon neutrality in Russia.

- Implementation of regional carbon targets in the forest plans of the subjects of the Russian Federation, forest management regulations of forest districts and forest development plans.

- Provision for the achievement of these targets both through departmental measures for mitigation and adaptation of forests, and through the implementation of forest climate projects by private investors.

- Implementation of measures to stimulate adaptation measures and climate projects through financial incentives and green financing for private investors. Minimizing administrative and departmental barriers in the implementation of climate projects in forests.

- Removing restrictions on agroforestry on unused agricultural lands, if this does not threaten "food security", which will strengthen measures to protect forests from fires and pests. Approximately 70% of such forests are not planned to be returned to agricultural turnover. In many regions (Vologda region, Kostroma region, Nizhny Novgorod region) agriculture turns out to be economically more sustainable precisely in cooperation with forest management.

- Definition, at the level of the carbon unit registry, of the best practices for the implementation of climate projects in the forest, including issues of determining the baseline, project scenario and additionality.

- Taking measures to harmonize Russian methodologies, the work of validation and verification authorities with international requirements in this area. This will be in demand, including within the framework of the upcoming processes of cross-border carbon regulation.

6. Conclusions: the Role of Forests in the Implementation of the Target Scenario of Low-Carbon Development in Russia

To better understand the possibilities of GHG absorption by ecosystems, it is important to determine both the full mitigation potential and the economically available mitigation potential, including the technical capabilities and economic feasibility of its use. The Yu.A. Izrael Institute of Global Climate and Ecology (IGCE) estimates the potential of CO2 mitigation by terrestrial ecosystems in Russia in the range of 545-940 million tons of CO2-eq. per the year [

52,

53].

These figures are based on a study of the full mitigation potential, without considering the costs and technological limitations associated with such measures. The potential for reducing forest fires emissions in [

53] is estimated at 220-420 million tons. The total absorption potential in Russian forests, according to the work of A. Romanovskaya, is approximately 235-480 million tons of CO2-eq., excluding the potential of projects for long-term storage of harvested wood products (HWP). The economically affordable mitigation potential within the framework of climate projects (with a cost of carbon units up to

$30) is up to 200 million tons of CO2-eq. per year by 2050 ([

46];

Table 4).

In the process of further discussion of the role of forests in the implementation of Russia’s low-carbon development, it is important to determine the ratio of the role of government spending and private investment, the role of structural measures to adapt forestry to modern climate change (such measures as, for example, changing the regulatory framework and forestry practices), and the place of forest climate projects (that is, projects implemented at the expense of investors who become owners of carbon units gained as a result of the implementation of forest climate project) in the decarbonization strategy of Russia. To characterize and assess the contribution of the federal project “Forest Conservation” of the national project “Ecology” (until 12/ 31/ 2024) and the Forestry Development state program (until 2030) as the main instruments of financing forestry by the Russian Federation in the country to the implementation of LT LEDS, it is advisable to quantify the GHG absorption within the framework of ongoing measures in the field of forestry financed from the federal budget.

A wide range of forecast values of decarbonization parameters, different interpretations of the role of adaptation and mitigation measures, climate projects, public and private investments necessitate the development of expert dialogue, openness in conducting transactions with carbon units in the national register of carbon units and further work to find the optimal scenario for decarbonization of Russia in the LT LEDS Operational plan.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.A.S., A.V.P., A.A.R., and V.N.K.; methodology, A.V.P. and A.A.R.; formal analysis, E.A.S., A.V.P., A.A.R. and V.N.K.; investigation, A.V.P., A.A.R., and V.N.K.; resources, E.A.S. and A.V.P., data curation, A.V.P., A.A.R., V.N.K. and A.S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, E.A.S., A.V.P., A.A.R., V.N.K.; writing—review and editing, E.A.S., A.V.P., A.A.R., V.N.K. and A.S.B.; visualization, A.V.P. and A.S.B.; supervision, E.A.S., A.V.P. and A.A.R.; project administration, A.S.B.; funding acquisition, E.A.S. and A.V.P.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The studies were supported by grant of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of Russian Federation (agreement № 075-15-2024-554 of 24.04.2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Konstantin Kobyakov (Nature&People Foundation, Moscow), Galina Popova (Center for Responsible Environmental Management, Institute of Geography of the Russian Academy of Sciences) and Varvara Gryaznova (MGIMO) for their valuable assistance in preparing this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCUS |

Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage |

| DACS |

Direct Air Capture and Storage |

| EMISS |

Unified Interdepartmental Information and Statistical System |

| GDP |

Gross domestic product |

| GHG |

Greenhouse gases |

| HWP |

Harvested wood products |

| IG RAS |

Institute of Geography of the Russian Academy of Sciences |

| IGCE |

Institute of Global Climate and Ecology named after Academician Yu.A. Israel |

| IPCC |

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| ISDM-Rosleskhoz |

Forest Fires Remote Monitoring Information System of the Federal Forestry Agency |

| LT LEDS |

Long term low-emission Development Strategy of Russia |

| LULUCF |

Land use, land-use change and forestry |

| NDC |

Nationally determined contribution |

| NID |

National GHG Inventory Document |

| SFI |

State Forest Inventory |

| SFR |

State Forest Register |

| UNFCCC |

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

| VIP GZ |

The significant innovative project of national importance "Unified National Monitoring System of Climatically Active Substances" |

References

- Accounts Chamber of the Russian Federation. Bulletin of the Accounts Chamber of the Russian Federation No 1 (278). Forest firefighting equipment. 2021. Available online: https://ach.gov.ru/statements/byulleten-schetnoy-palaty-1-278-2021-g (accessed on 10 June 2024). (In Russian).

- Accounts Chamber of the Russian Federation. Bulletin of the Accounts Chamber of the Russian Federation No 4 (305). Forest protection. 2023. Available online: https://ach.gov.ru/statements/bulletin-sp-4-2023 (accessed on 10 June 2024). (In Russian).

- Bartalev, S.A.; Egorov, V.A.; Zharko, V.O.; Lupyan, E.A.; Plotnikov, D.E.; Khvostikov, S.A.; Shabanov, N.V. Satellite mapping of vegetation cover in Russia; IKI RAS: Moscow, (In Russian). 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bartalev, S.A.; Lukina, N.V. New methodology for studying carbon in the forests of Russia from space. Zemlya i vselennaya 2023, 5, 44–58. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bill, No. 566540-8 “On Amendments to the Forest Code of the Russian Federation (in order to create legal grounds for the implementation of climate projects in forests on the territory of the Russian Federation)”. Available online: https://sozd.duma.gov.ru/bill/566540-8 (accessed on 16 June 2024). (In Russian).

- Bysouth, D.; Boan, J.J.; Malcolm, J.R.; Taylor, A.R. High emissions or carbon neutral? Inclusion of “anthropogenic” forest sinks leads to underreporting of forestry emissions. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change 2024, 6, 1297301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, H.; Lau, Y.-Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, W.; Zhang, G. Climate change, carbon peaks, and carbon neutralization: A bibliometric study from 2006 to 2023. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciais, P.; Canadell, J.; Luyssaert, S.; Chevallier, F.; Shvidenko, A.; Poussi, Z.; Jonas, V.; Peylin, P.; Wayne King, A.; Schulze, E.-D.; Piao, S.; Rodenbeck, C.; Peters, W.; Bréon, F.-M. Can we reconcile atmospheric estimates of the Northern terrestrial carbon sink with land-based accounting? Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2010, 2, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Action Tracker. 2022. Available online: https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/russian-federation (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Dai, M.; Sun, M.; Chen, B.; Shi, L.; Jin, M.; Man, Y.; Liang, Z.; Almeida, C.M.V.B.; Li, J.; Zhang, P.; Chiu, ASF.; Xu, M.; Yu, H.; Meng, J.; Wang, Y. Country-specific net-zero strategies of the pulp and paper industry. Nature 2023, 626, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolman, A.J.; Shvidenko, A.; Schepaschenko, D.; Ciais, D.; Tchebakova, N.; Chen, T.; Van der Molen, M.K.; Belelli Marchesini, L.; Maximov, T.; Maksyutov, S.; Schulze, E.D. An estimate of the terrestrial carbon budget of Russia using inventory-based, eddy covariance and inversion methods. Biogeosciences 2012, 9, 5323–5340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Wigneron, J.P.; Ciais, P.; Chave, J.; Brandt, M.; Sitch, S.; Yue, C.; Bastos, A.; Li, X.; Qin, Y.; Yuan, W.; Schepaschenko, D.; Mukhortova, L.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, M.; Frappart, F.; Xiao, X.; Chen, J.; Ma, M.; Wen, J.; Chen, X.; Yang, H.; Van Wees, D.; Fensholt, R. Siberian carbon sink reduced by forest disturbances. Nature Geoscience 2023, 16, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The Russian Federation Forest sector: outlook study to 2030. Rome, Italy, 2012. (In Russian)

- Filipchuk, A.; Moiseev, B.; Malysheva, N.; Strakhov, V. () Russian forests: A new approach to the assessment of carbon stocks and sequestration capacity. Environmental Development 2018, 26, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipchuk, A.N.; Malysheva, N.V. The assessment of the feasibility of using the state forest inventory data to implement the national commitments under the Paris Agreement. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2020, 574, 012026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipchuk, A.N.; Malysheva, N.V.; Moiseev, B.N.; Strakhov, V.V. Analytical overview of methodologies calculating missions and absorptions of greenhouse gases by forests from the atmosphere. Forestry Information 2016, 3, 36–85. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Filipchuk, A.N.; Malysheva, N.V.; Zolina, T.A.; Yugov, A.N. The Boreal Forest of Russia: Opportunities for the Effects of Climate Change Mitigation. Forestry Information 2020, 1, 92–114. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipchuk, A.N.; Moiseev, B.N.; Yugov, A.N. Comparative Assessment of statistics on Growing Stock in Forests of Russian Federation. Forestry Information 2017, 2, 16–25. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardin, C.A.J.; Jenkins, S.; Seddon, N.; Allen, M.; Lewis, S.L.; Wheeler, C.E.; Griscom, B.W.; Malhi, Y. Nature-based solutions can help cool the planet – if we act now. Nature 2021, 593, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griscom, B.W.; Adams, J.; Ellis, P.W.; Houghton, R.A.; Lomax, G.; Miteva, D.A.; Schlesinger, W.H.; Shoch, D.; Siikamäki, J.V.; Smith, P.; Woodbury, P.; Zganjar, C.; Blackman, A.; Campari, J.; Conant, R.T.; Delgado, C.; Elias, P.; Gopalakrishna, T.; Hamsik, M.R.; Herrero, M.; Kiesecker, J.; Landis, E.; Laestadius, L.; Leavitt, S.M.; Minnemeyer, S.; Polasky, S.; Potapov, P.; Putz, F.E.; Sanderman, J.; Silvius, M.; Wollenberg, E.; Fargione, J. Natural Climate Solutions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114, 11645–11650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, N.L.; Gibbs, D.A.; Baccini, A.; Birdsey, R.A.; De Bruin, S.; Farina, M.; Fatoyinbo, L.; Hansen, M.C.; Herold, M.; Houghton, R.A.; Potapov, P.V.; Suarez, D.R.; Roman-Cuesta, R.M.; Saatchi, S.S.; Slay, C.M.; Turubanova, S.A.; Tyukavina, A. Global maps of twenty-first century forest carbon fluxes. Nature Climate Change 2021, 11, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC 2006 Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. IPCC National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme.

- IPCC 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. IPCC, Switzerland. Available online: https://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2019rf (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Ivanov, A.Y.; et al. Battle for Climate: Carbon Farming as Russia's Bet: Expert Report; Higher School of Economics Publishing House: Moscow, 2021. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.P.G.; Lewis, S.L. Forest carbon offsets are failing: Analysis reveals emission reductions from forest conservation have been overestimated. Science 2023, 381, 830–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharuk, V.I.; Ponomarev, E.I.; Ivanova, G.A.; Dvinskaya, M.L.; Coogan, S.C.P.; Flannigan, M.D. Wildfires in the Siberian taiga. Ambio 2021, 50, 1953–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillina, K.; Shvetsov, E.G.; Protopopova, V.V.; Thiesmeyer, L.; Yan, W. Consideration of anthropogenic factors in boreal forest fire regime changes during rapid socio-economic development: case study of forestry districts with increasing burnt area in the Sakha Republic, Russia. Environmental Research Letters 2020, 15, 035009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimenko, V.V.; Klimenko, A.V.; Tereshin, A.G. Carbon-free Russia: is there a chance to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. Doklady Physics 2023, 68, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korosuo, A.; Pilli, R.; Viñas, R.A.; Blujdea, V.N.B.; Colditz, R.R.; Fiorese., G.; Rossi, S.; Vizzarri, M.; Grassi, G. The role of forests in the EU climate policy: are we on the right track? Carbon balance and management 2023, 18, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotkov, V.N.; Shanin, V.N.; Frolov, P.V. Can artificial reforestation always be a forest climatic project? In: Grabarnik PY, Logofet DO (ed) Proceedings of the Seventh Conference «Mathematical Modeling in Ecology», November 9–12, 2021. FRC PNTsBI RAS, Pushchino, pp 57–58. (In Russian)

- Krenke, A.N.; Ptichnikov, A.V.; Shvarts, E.A.; Petrov, I.K. Assessments of the forest carbon balance in the national climate policies of Russia and Canada. Doklady Earth Sciences 2021, 501, 1091–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukavskaya, E.A.; Shvetsov, E.G.; Buryak, L.V.; Tretyakov, P.D.; Groisman, P.Y. Increasing fuel loads, fire hazard, and carbon emissions from fires in Central Siberia. Fire 2023, 6, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauerwald, R.; Bastos, A.; McGrath, M.J.; et al. Carbon and greenhouse gas budgets of Europe: trends, interannual and spatial variability, and their drivers. Authorea Preprints 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long term low-emission Development Strategy of Russia Operational plan draft. Available online: https://t.me/greenserpent/19734 (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Loupian, E.A.; Lozin, D.V.; Balashov, I.V.; Bartalev, S.A.; Stytsenko, F.V. A study of the dependence of the degree of forest damage by fires on the intensity of burning according to satellite-monitoring data. Cosmic Research 2022, 60, S46–S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozin, D.V.; Loupian, E.A.; Balashov, I.V.; Bartalev, S.A. Estimation of Northern Burnt Forest Mortality in the 21st Century Based on MODIS Data on Fire Intensity. Cosmic Research 2023, 61, S118–S124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matveev, A.M.; Bartalev, S.A. A comparative analysis of wildfire carbon emissions estimates in Russia according to global inventories. Sovremennye problemy distantsionnogo zondirovaniya Zemli iz kosmosa 2024, 21, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment of the Russian Federation Passport of the National Project “Ecology”. 2018. Available online: https://www.mnr.gov.ru/activity/directions/natsionalnyy_proekt_ekologiya/ (accessed on 12 February 2025). (In Russian).

- Mo, L.; Zohner, C.M.; Reich, P.B.; Liang, J.; et al. Integrated global assessment of the natural forest carbon potential. Nature 2023, 624, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morkovina, S.S.; Kharchenko, N.N.; Sheshnitsian, S.S.; Panyavina, E.A.; Ivanova, A.V.; Vodolazhskiy, A.I. Ecological and economic assessment of forestry practices efficiency in maintaining carbon balance. Lesnoy vestnik. Forestry Bulletin 2024, 28, 104–117. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbonna, C.G.; Nwachi, C.C.; Okeoma, I.O.; Fagbami, O.A. Understanding Nigeria’s transition pathway to carbon neutrality using the Multilevel Perspective. Carbon Neutrality 2023, 2, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Order of the Government of the Russian Federation, No. 3052-r dated 10/29/2021 “On Approval of the Strategy of Socio-Economic Development of the Russian Federation with Low Greenhouse Gas Emissions until 2050”. (In Russian). Available online: https://www.consultant.ru/document/cons_doc_LAW_399657 (accessed 16 June).

- Pan, Y.; Birdsey, R.A.; Phillips, O.L.; et al. The enduring world forest carbon sink. Nature 2024, 631, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptichnikov, A.V.; Shvarts, E.A.; Kuznetsova, D.A. The greenhouse gas absorption potential of Russian forests and possibilities for carbon footprint reduction for exported domestic products. Doklady Earth Sciences 2021, 449, 683–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptichnikov, A.V.; Shvarts, E.A.; Popova, G.A.; Baibar, A.S. The role of forests in the implementation of Russia’s low-carbon development strategy. Doklady Earth Sciences 2022, 507, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptichnikov, A.V.; Shvarts, E.A.; Popova, G.A.; Baibar, A.S. Low-carbon development strategy of Russia and the role of forests in its implementation. Herald of the Russian Academy of Sciences (In Russian). 2023, 93, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzachenko, Y.G.; Kotlov, I.P.; Sandlerskiy, R.B. Analysis of changes of land cover using multispectral remote sensing information in the central forest reserve. Izvestiya Rossiiskoi Akademii Nauk Seriya Geograficheskaya, 2014, No. 3, pp. 5–18. (In Russian). [CrossRef]

- 2024. Available online: https://ria.ru/20241008/rossija-1976932385.html (accessed on 12 February 2025). (In Russian).

- Roe, S.; Streck, C.; Obersteiner, M.; Frank, S.; Griscom, B.; Drouet, L.; Fricko, O.; Gusti, M.; Harris, N.; Hasegawa, T.; Hausfather, Z.; Havlík, P.; House, J.; Nabuurs, G.-J.; Popp, A.; Sánchez, M.J.S.; Sanderman, J.; Smith, P.; Stehfest, E.; Lawrence, D. Contribution of the land sector to a 15°C world. Nature Climate Change 2019, 9, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanov, A.A.; Tamarovskaya, A.N.; Gloor, E.; Brienen, R.; Gusev, B.A.; Leonenko, E.V.; Vasiliev, A.S.; Krikunov, E.E. Reassessment of carbon emissions from fires and a new estimate of net carbon uptake in Russian forests in 2001–2021. Science of the total environment 2022, 846, 157322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanovskaya, A.A. Approaches to Implementing Ecosystem Climate Projects in Russia. Regional Research of Russia 2023, 13, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanovskaya, A.A.; Korotkov, V.N. Balance of anthropogenic and natural greenhouse gas fluxes of all inland ecosystems of the Russian Federation and the contribution of sequestration in forests. Forests 2024, 15, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanovskaya, A.A.; Korotkov, V.N.; Polumieva, P.D.; Trunov, A.A.; Vertyankina, V.Y.; Karaban, R.T. Greenhouse gas fluxes and mitigation potential for managed lands in the Russian Federation. Mitigation and adaptation strategies for global change 2020, 25, 661–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepaschenko, D.; Moltchanova, E.; Fedorov, S.; Karminov, V.; Ontikov, P.; Santoro, M.; See, L.; Kositsyn, V.; Shvidenko, A.; Romanovskaya, A.; Korotkov, V.; Lesiv, M.; Bartalev, S.; Fritz, S.; Shchepashchenko, M.; Kraxner, F. Russian forest sequesters substantially more carbon than previously reported. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 12825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepaschenko, D.; Moltchanova, E.; Shvidenko, A.; Blyshchyk, V.; Dmitriev, E.; Martynenko, O.; See, L.; Kraxner, F. Improved Estimates of Biomass Expansion Factors for Russian Forests. Forests 2018, 9, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanin, V.N.; Frolov, P.V.; Korotkov, V.N. Can artificial reforestation always be a forest climatic project? Forest Science Issues 2022, 5, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Zhong, Y.; Li, Y.; Altuntas, M. Does environmental and renewable energy R&D help to achieve carbon neutrality target? A case of the US economy. Journal of Environmental Management 2021, 296, 113229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirov, A.A.; Kolpakov, A.Y.; Gambhir, A.; Koasidis, K.; Köberle, A.C.; McWilliams, B.; Nikas, A. Stakeholder-driven scenario analysis of ambitious decarbonisation of the Russian economy. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Transition 2023, 4, 100055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shvarts, E.A.; Kokorin, A.O.; Ptichnikov, A.V.; Krenke, A.N. Cross-Border Carbon Regulation and Forests in Russia: From Expectations and Myth to Realization of Interests. Economic policy 2022, 17, 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shvarts, E.A.; Ptichnikov, A.V. Low-carbon development strategy of Russia and the role of forests in its implementation. Scientific Works of the Free Economic Society of Russia 2022, 236, 399–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shvidenko, A.; Mukhortova, L.; Kapitsa, E.; Kiaxner, F.; See, L.; Pyzhev, A.; Gordeev, R.; Fedorov, S.; Korotkov, V.; Bartalev, S.; et al. A Modelling System for Dead Wood Assessment in the Forests of Northern Eurasia. Forests 2023, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shvidenko, A.Z.; Schepaschenko, D.G. Carbon budget of Russian forests. Siberian Journal of Forest Science 2014, 1, 69–92. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Shvidenko, A.Z.; Schepaschenko, D.G.; Nilsson, S.; Buluy, YI. Tables and Models of Growth and Productivity of Forests of Major Forest Forming Species of Northern Eurasia. Standard and Reference Materials, 2nd ed.; Federal Agency of Forest Management: Moscow, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Soterroni, A.C.; Império, M.; Scarabello, M.C.; Seddon, N.; Obersteiner, M.; Rochedo, P.R.R.; Schaeffer, R.; Andrade, P.R.; Ramos, F.M.; Azevedo, T.R.; Ometto, J.P.; Havlík, P.; Alencar, A.A. Nature-based solutions are critical for putting Brazil on track towards net-zero emissions by 2050. Global Change Biology 2023, 29, 7085–7101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K. Expanding carbon removal to the Global South: Thematic concerns on systems, justice, and climate governance. Energy and Climate Change 2023, 4, 100103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Report “On the State and Environmental Protection of the Russian Federation in 2015”. Available online: https://www.mnr.gov.ru/docs/o_sostoyanii_i_ob_okhrane_okruzhayushchey_sredy_rossiyskoy_federatsii/http_new_mnr_gov_ru_docs_gosudarstvennye_doklady (accessed on 5 June 2024). (In Russian).