Submitted:

18 May 2025

Posted:

19 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

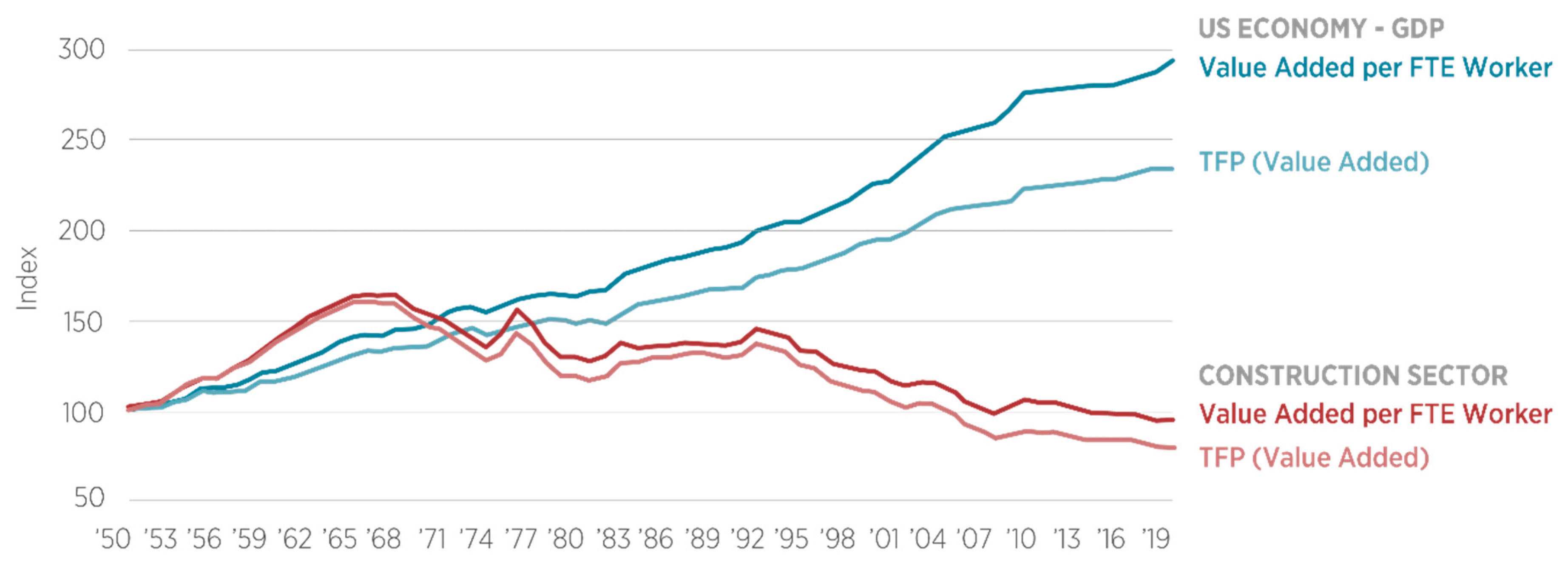

1.1. Current Status of the Construction Sector

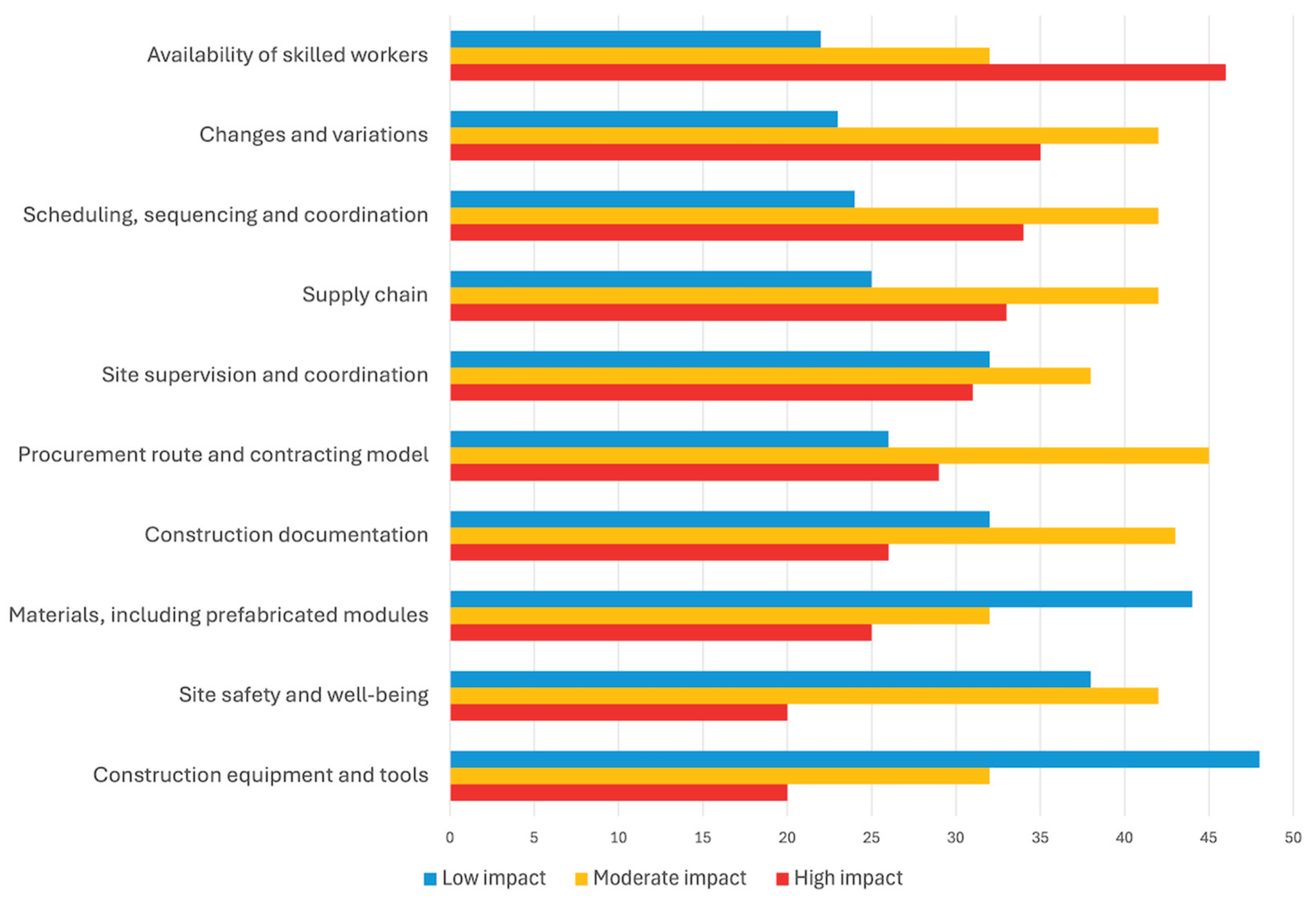

1.2. The Productivity Gap and Its Root Causes

1.3. Existing Approaches and Their Limitations

1.4. Research Contribution: A Hierarchical Framework for Construction Productivity

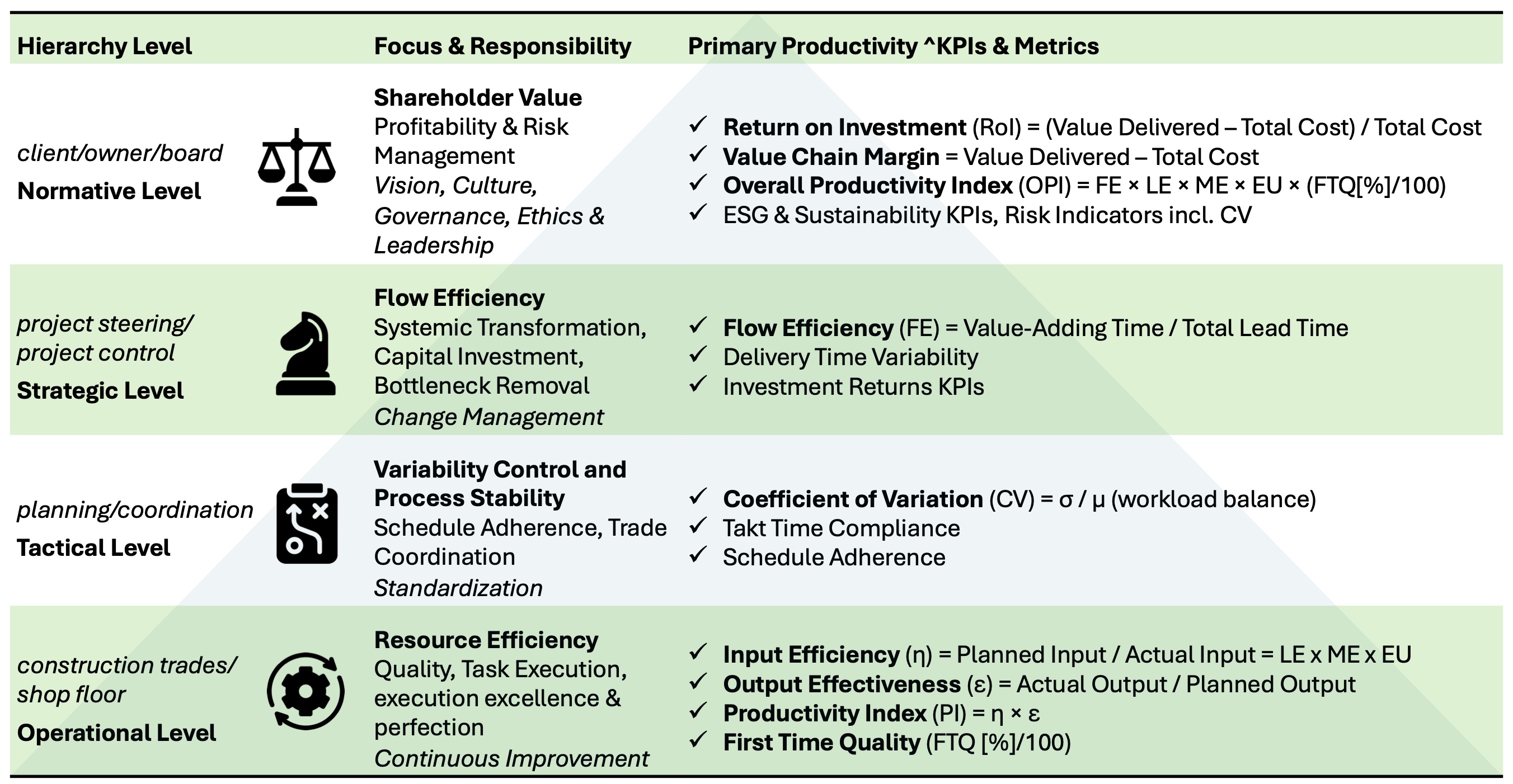

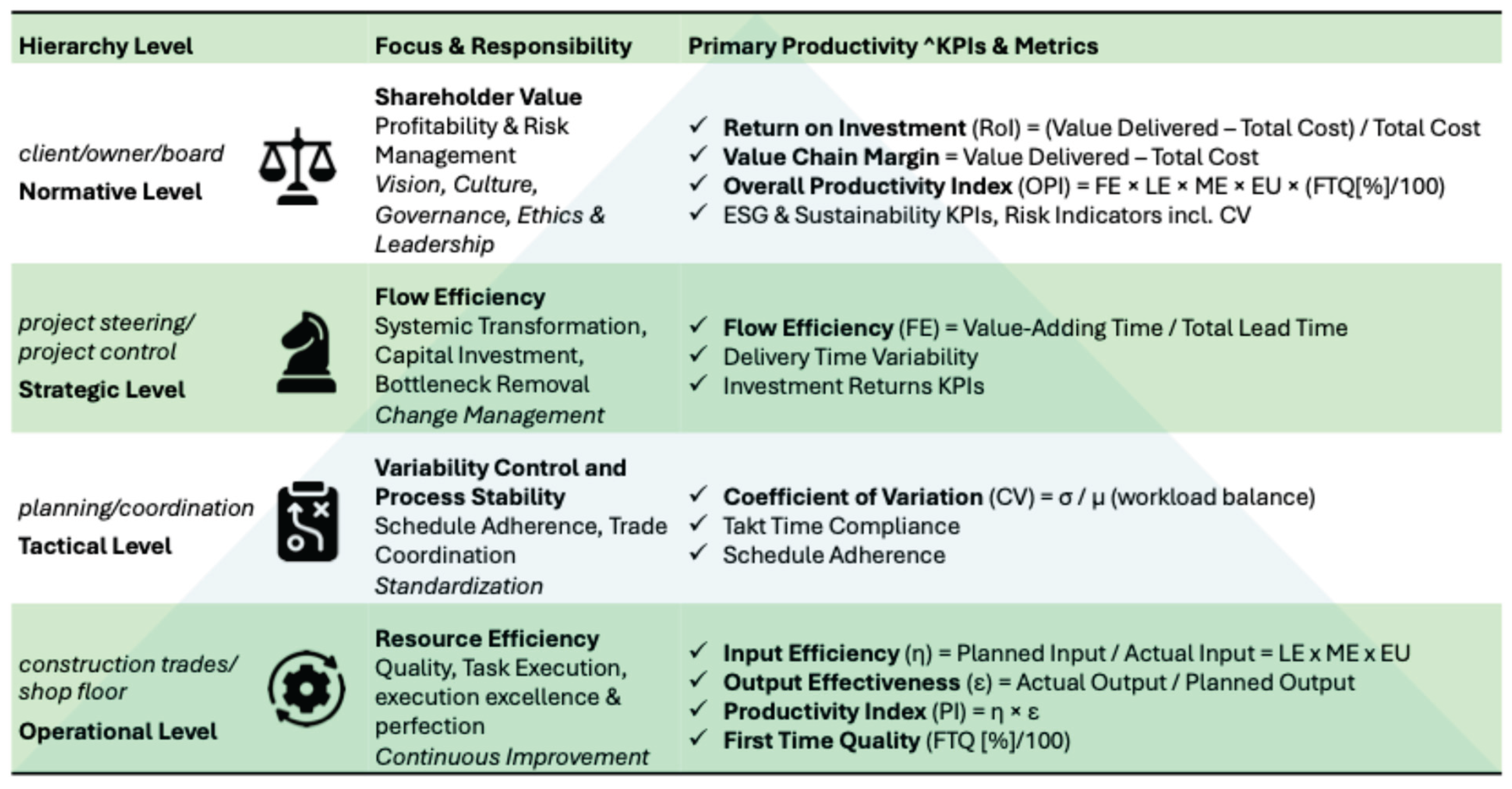

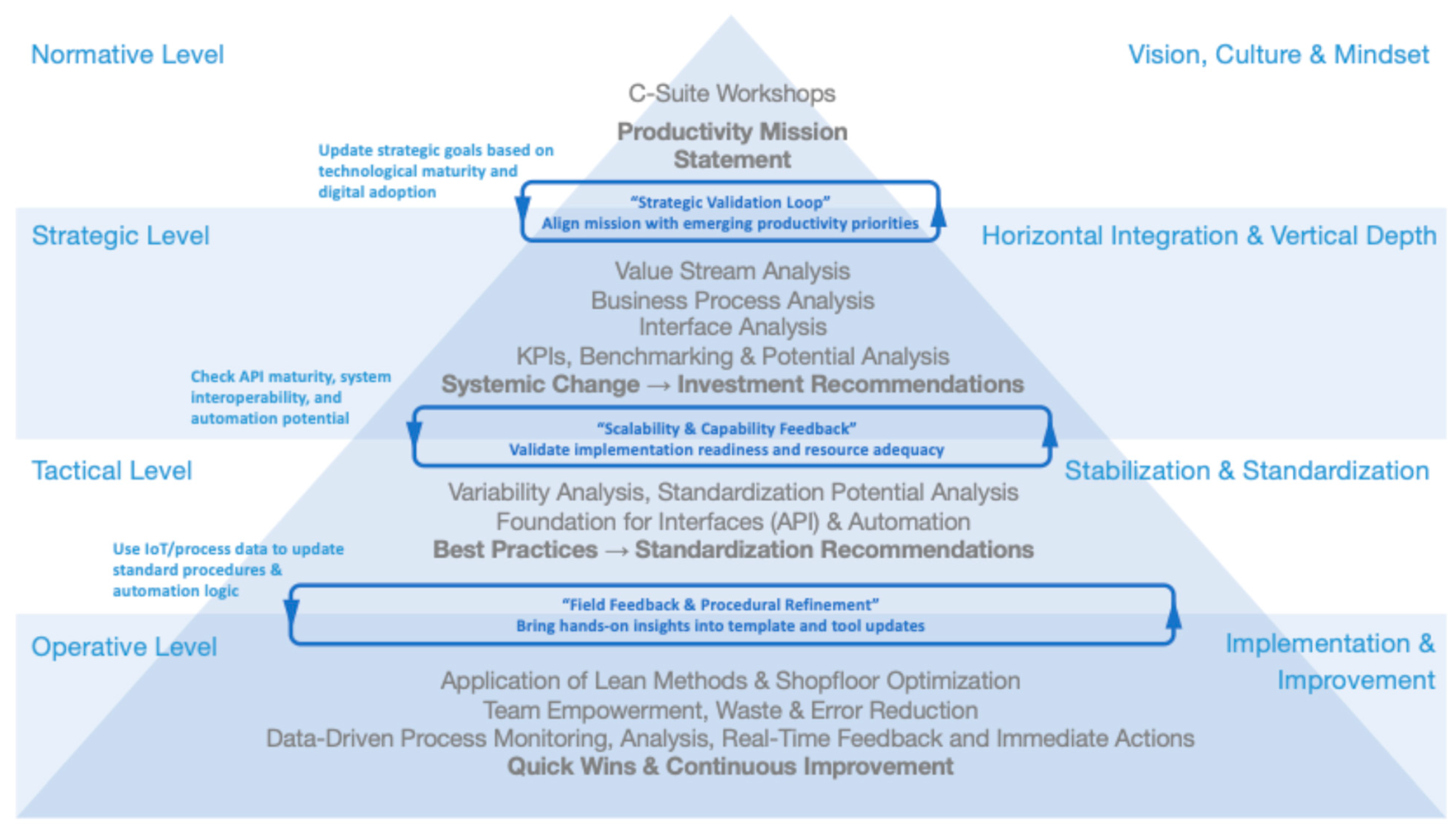

- Operational Level: Standardized process steps are recorded through Value Stream Mapping (VSM) and analyzed via input efficiency, output effectiveness, and First-Time Quality (FTQ). This granular data foundation enables high-resolution performance diagnostics while preserving traceability across tasks and trades.

- Tactical Level: Metrics such as takt-time compliance, schedule reliability, and workload balance (expressed through the Coefficient of Variation) are used to assess trade synchronization and production flow stability. These KPIs are synthesized across process clusters and work packages.

- Strategic Level: Broader performance indicators—including flow efficiency and multi-resource utilization—capture the coordination of trades, disciplines, and modules across spatial and temporal interfaces within the project environment.

- Normative Level: The framework culminates in a composite Overall Productivity Index (OPI), combining quality, efficiency, and effectiveness metrics with sustainability and ESG considerations to inform organizational learning and capital allocation.

- IoT-based real-time sensing,

- computer vision–enabled activity tracking,

- and agentic AI systems capable of autonomous workflow re-sequencing and predictive bottleneck elimination.

2. Historical Context and Current State of the Research Field, Traditional Methods of Productivity Measurement (the Past 100 Years)

2.1. Early Scientific Management and Time-Motion Studies (1900s–1920s)

2.2. Gantt Charts and Project Scheduling (1910s–1950s)

2.3. On-Site Observational Methods – Work Sampling and Time Tracking (1940s–1980s)

2.4. Unit Rate Tracking and Early Productivity Standards (1960s-1980s)

2.5. Evolution into Industry Standards and Lean Practices (1990s–2000s)

2.6. Summary of Advantages and Limitations

3. Review of Existing Productivity Metrics and Frameworks

3.1. Productivity in Construction: Perceptions, Metrics, and Conceptual Foundations

- Labor productivity, typically expressed as output (e.g., value added) per labor hour;

- Capital productivity, which considers the return on equipment and infrastructure investment;

3.2. Measurement Levels and Multi-Scale Productivity Perspectives

- At the task or trade level, metrics focus on specific activities (e.g., cubic meters of concrete poured per crew-hour).

- At the project level, broader indices combine labour and cost metrics to reflect overall efficiency (e.g., square meters delivered per euro or per man-day).

- At the industry level, productivity is typically reported through national statistics or macroeconomic surveys based on value added, capital stock, and labour data.

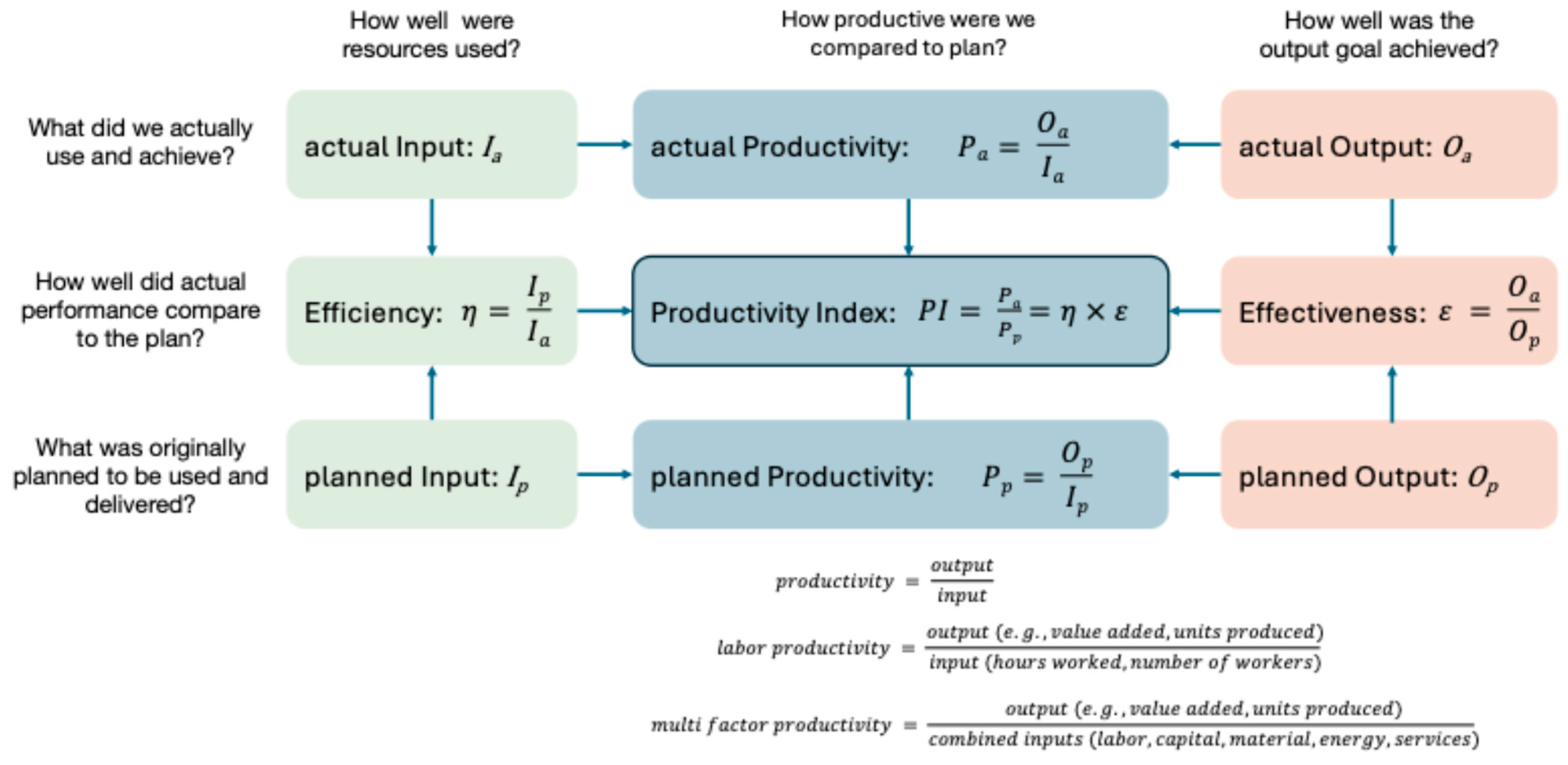

- Planned Productivity (PP): The expected output per planned input;

- Actual Productivity (AP): The realized output per actual input;

- Efficiency (η): The ratio of planned input to actual input, indicating resource use;

- Effectiveness (ε): The ratio of actual output to planned output, indicating goal fulfillment;

- Productivity Index (PI): A composite metric defined as η × ε, integrating both dimensions.

3.3. Challenges in Standardization and Data Coherence

- (1)

- Overreliance on Single-Factor Indicators: Labor productivity remains the most frequently cited metric in both research and practice, yet it captures only one dimension of performance. A crew may appear more productive in labour terms by increasing equipment usage or material throughput, while total resource efficiency may decline. Hence, labour productivity can be misleading if viewed in isolation—especially in capital- or technology-intensive environments [63].

- (2)

- Activity-Level Myopia and Lack of System View: Productivity metrics often focus on individual trades or isolated tasks (e.g., cubic meters of concrete placed per hour). However, construction outcomes result from interdependent workflows. Gains in one area (e.g., faster rebar placement) can disrupt others (e.g., delays in inspections or follow-on trades). This lack of systemic perspective undermines the validity of task-level metrics as proxies for overall project performance [63].

- (3)

- Macro–Micro Disconnect: There is a well-documented disjunction between project-level data and macroeconomic indicators. National or industry-wide productivity reports may show stagnation or decline, while individual projects report local gains—often due to methodological mismatches in data aggregation, output definitions, or sector-level adjustments [63]. This misalignment hampers policy relevance and undermines trust in reported figures.

- (4)

- Absence of Harmonized Data Infrastructure: Unlike manufacturing, construction lacks centralized reporting platforms for performance data. Measurement practices are typically firm-specific, undocumented, and manually conducted. This lack of structured, interoperable datasets impedes benchmarking, comparison across firms or regions, and broader research on best practices [63].

3.4. Fragmentation, Silo Thinking, and the One-Off Nature of Projects

3.5. External Variability and Systemic Dependencies

3.6. Lessons from Manufacturing: Flow, Modularity, and Standardization

- Process standardization to reduce variability and ensure repeatability;

- Modularization and prefabrication to enable efficient assembly and reduce onsite complexity;

- Automation and robotics to increase throughput and minimize human error;

- Integrated supply chains to synchronize material, information, and process flows.

4. A Unified Hierarchical Framework for Productivity Measurement in Construction

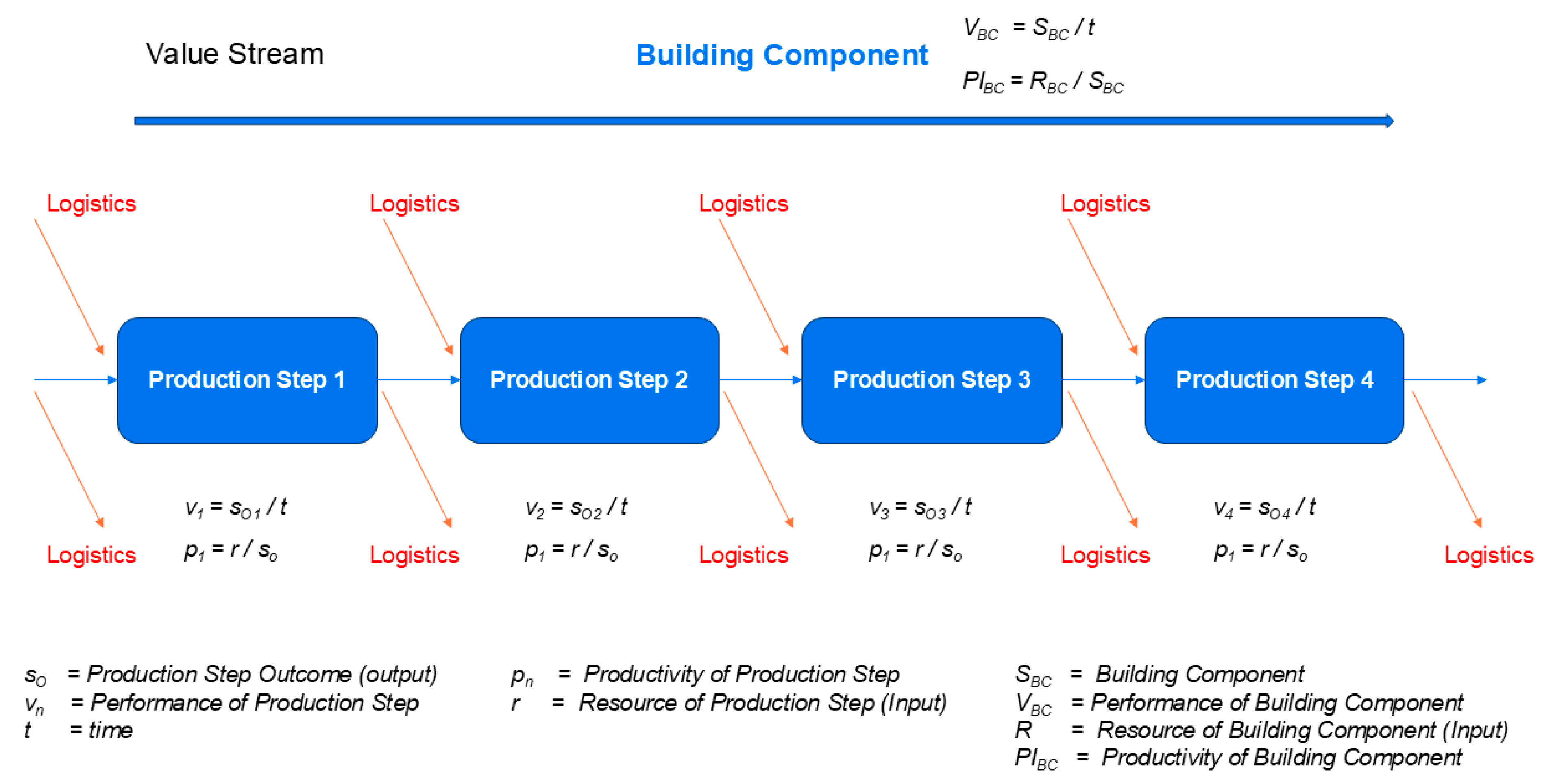

4.1. Operational Level

- Benchmarking performance: Actual task durations and resource usage can be compared against standard benchmarks derived from the Value Stream Map (VSM) of a given Building Component. These benchmarks represent the sum of expected durations for standardized process steps plus idealised logistics times (assumed to be zero in a just-in-time setup). This enables calculation of performance deviations at the level of individual construction elements.

- Benchmarking productivity: Similarly, productivity can be evaluated as the ratio of resource input (e.g. labour hours) to the actual output (e.g. installed area or component volume), allowing for quantifiable comparisons of work efficiency across different crews, shifts, or sites.

- Waste identification: Discrepancies between standard and actual sequences (e.g. idle time, rework, excessive motion) become visible within the process step model, highlighting bottlenecks and non-value-adding activities for elimination.

- Transfer of best practices: Because a process step such as “pour concrete” is identically defined across projects, successful strategies and learned optimizations from one site can be directly transferred to another, reinforcing organizational learning.

4.2. Tactical Level (or Trade Level)

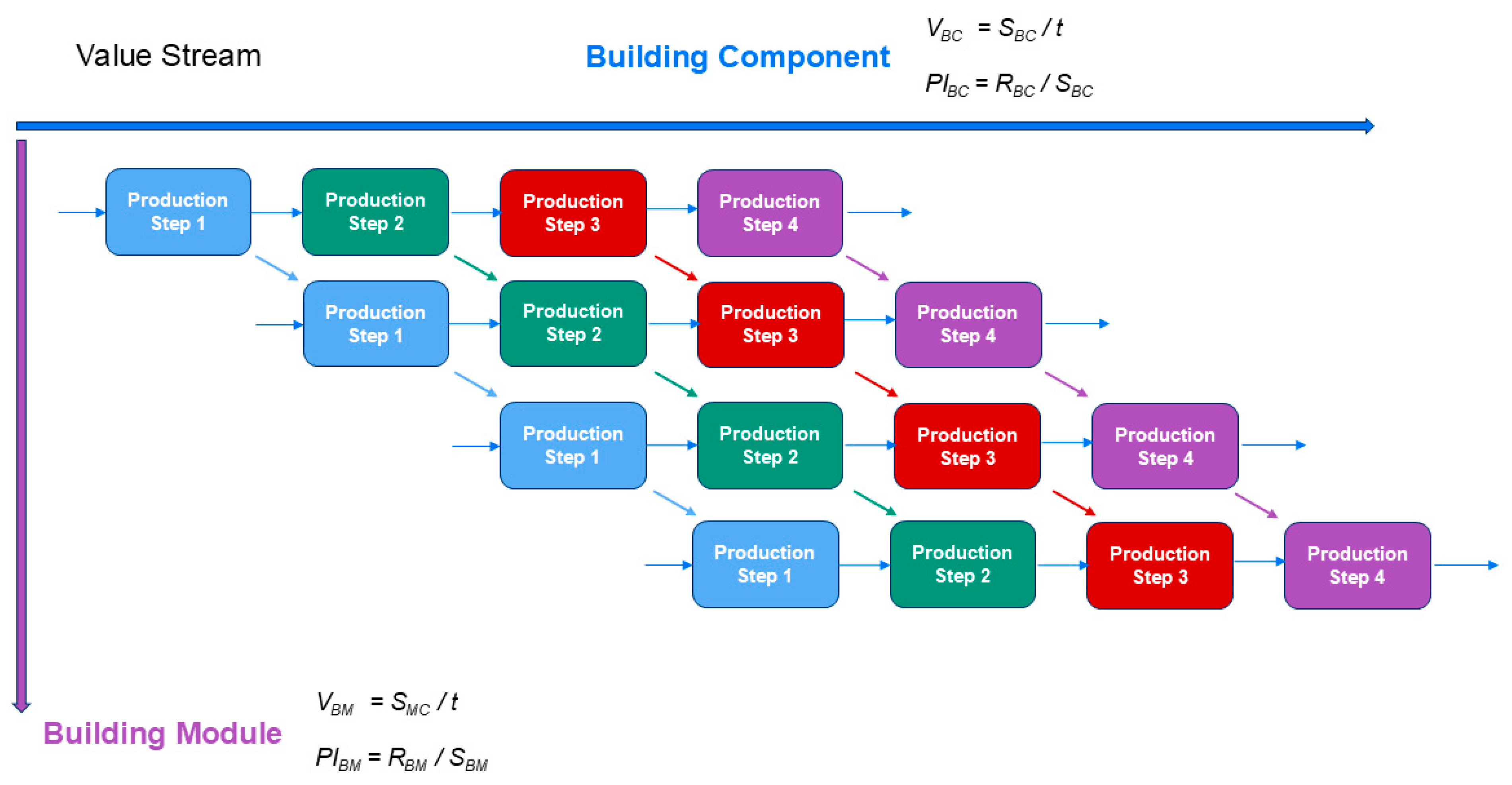

- Horizontal productivity is calculated along the process axis. It aggregates the cycle times and First-Time-Quality scores of the standardised process steps that form a single building component (e.g., one bored pile, one drywall partition).

- Vertical productivity is measured up the operation axis. It sums the performance of all construction elements produced by one trade within a defined zone or takt window, yielding the overall productivity of a Construction Module (e.g., an entire bored-pile wall or a completed apartment floor).

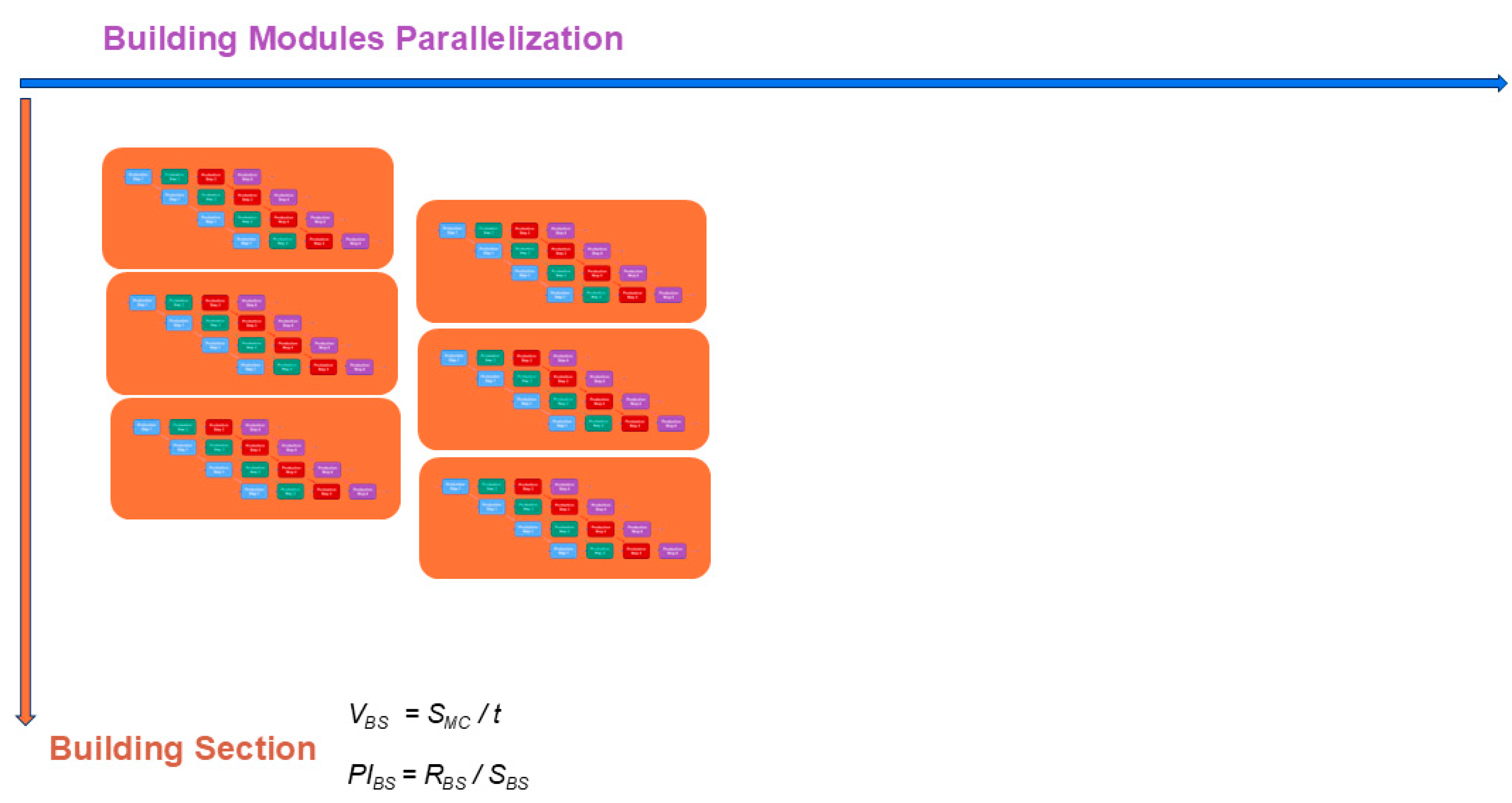

4.3. Stratetic Level (or Building Section or Building)

5. Discussion and Future Outlook

5.1. Future Research Directions

- Empirical validation of the hierarchical framework across diverse project typologies (e.g., high-rise, infrastructure, modular housing), procurement models, and geographic contexts.

- Integration with digital twins and IoT-based observability, enabling bi-directional feedback between physical construction processes and virtual planning/control environments.

- Deployment of agentic AI systems that leverage the hierarchical KPI structure to detect deviations, trigger learning loops, and optimize workflows autonomously—while maintaining traceability and human oversight.

- Potential exploration of exponential technologies in construction such as smart contracts and blockchain integration for linking real-time productivity data to contractual milestones, payment systems, and performance-based incentives.

- Development of interoperability standards to bridge heterogeneous platforms (e.g., BIM, ERP, site sensors) through API harmonization and common data ontologies. This also aligns with recent initiatives in platform-based industrialization and open data models such as IFC 4.3 and ISO 19650, which seek to harmonize productivity data across construction ecosystems.

- Cultural and organizational change frameworks to overcome resistance to automation, standardization, and the shift from intuition-based to data-driven project management.

- The proposed framework can serve as a blueprint for digital construction standards, productivity-linked contracts, and AI integration strategies at both firm and industry levels. We recommend its inclusion in sectoral modernization roadmaps, such as those currently pursued under national productivity missions, construction industrialization plans, or EU digital twin programs.

5.2. Towards the Future of Intelligent Construction

5.3. Conclusion: A New Paradigm for Construction Productivity

5.4. Limitations and Future Work

- Inter-project comparability of standardized process steps remains a methodological and organizational challenge across heterogeneous firms and delivery models. The potential tension between standardization and the bespoke nature of architectural design intent, which may require careful reconciliation between performance optimization and aesthetic/functional diversity.

- Integration with legacy IT ecosystems and fragmented data silos may require transitional interfaces, change management processes, and phased implementation strategies.

- Cultural resistance to automation, standardization, and performance transparency may constrain adoption, particularly in traditionally managed organizations.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| BEA | Bureau of Economic Analysis |

| BIM | Building Information Modelling |

| CICE | Construction Industry Cost Effectiveness |

| CPI | cost performance index |

| CPM | Critical Path Method |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| EVM | Earned Value Management |

| FTE | Full Time Equivalent |

| FTQ | First Time Quality |

| HIC | Human-in-Command |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| LiDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| MPDM | Method Productivity Delay Model |

| OPI | Overall Productivity Index |

| PERT | Program Evaluation and Review Technique |

| R&D | Research and Development |

| ROI | Return on Investment |

| SPI | Schedule performance index |

| TFP | Total factor productivity |

| VSM | Value Stream Mapping |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1 Definition of Key Concepts and Terms

References

- Farmer, M. The Farmer Review of the UK construction labour model "Modernize or die - Time to decide the industry's future"; http://www.constructionleadershipcouncil.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Farmer-Review.pdf, 2016.

- Barbosa, F.; Woetzel, J.; Mischke, J. Reinventing construction: A route of higher productivity; dln.jaipuria.ac.in: 2017.

- Barbosa, F.; Mischke, J.; Parsons, M. Improving construction productivity; dln.jaipuria.ac.in: 2017.

- Goolsbee, A.; Syverson, C. The strange and awful path of productivity in the us construction sector; nber.org: 2023.

- Mischke, J.; Stokvis, K.; Vermeltfoort, K.; Biemans, B. Delivering on construction productivity is no longer optional; 2024.

- Hossain, M.; Ng, S.; Antwi-Afari, P.; Amor, B. Circular economy and the construction industry: Existing trends, challenges and prospective framework for sustainable construction. Renewable and Sustainable … 2020.

- Yang, M.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Msigwa, G.; Osman, A.; ... Circular economy strategies for combating climate change and other environmental issues; Springer: 2023.

- World Economic Forum (WEF). Shaping the Future of Construction: A Breakthrough in Mindset and Technology; World Economic Forum: Cologny, Switzerland, 2016.

- Ballard, G.; Howell, G. Shielding production: Essential step in production control. Journal of Construction Engineering and … 1998. [CrossRef]

- Koskela, L. An exploration towards a production theory and its application to construction; aaltodoc.aalto.fi: 2000.

- World Economic Forum (WEF). Shaping the Future of Construction – An Action Plan to solve the Industry’s Talent Gap; World Economic Forum: Cologny, Switzerland, 2018.

- Bühler, M.M.; Jelinek, T.; Nübel, K. Training and Preparing Tomorrow’s Workforce for the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Education Sciences 2022, 12, 782.

- Alejo, A.; Aigbavboa, C.; Aghimien, D. Emerging Trends of Safe Working Conditions in the Construction Industry: A Bibliometric Approach; mdpi.com: 2024.

- Elbashbishy, T.; El-adaway, I. Assessing the Impact of Skilled Labor Shortages on Project Cost Performance. Construction Research Congress … 2024. [CrossRef]

- Syverson, C. Challenges to mismeasurement explanations for the US productivity slowdown. Journal of Economic Perspectives 2017. [CrossRef]

- Oglesby, C.; Parker, H.; Howell, G. Productivity improvement in construction; cir.nii.ac.jp: 1989.

- Thomas, H.; Kramer, D. The manual of construction productivity measurement and performance evaluation; firedoc.nist.gov: 1988.

- Clark, W. The Gantt chart: A working tool of management; Ronald Press Company: 1922.

- Hinze, J. Construction planning and scheduling; academia.edu: 2012.

- Fleming, Q.; Koppelman, J. Earned value project management; books.google.com: 2016.

- …; Tortorella, G.L.; Antony, J.; Romero, D. Lean Industry 4.0: Past, present, and future. Quality Management … 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ballard, G. The Lean Project Delivery System: An Update. Lean Construction Journal 2008.

- Ballard, G.; Howell, G. Lean project management. Building Research & Information 2003. [CrossRef]

- Howell, G. What is lean construction-1999; academia.edu: 1999.

- Koskela, L.; Howell, G.; Ballard, G.; ... The foundations of lean construction. Design and … 2007.

- Ballard, G.; Howell, G. Implementing lean construction: stabilizing work flow. Lean construction 1994.

- Frandson, A.; Berghede, K.; Tommelein, I. Takt time planning for construction of exterior cladding; Citeseer: 2013.

- Hamledari, H.; Fischer, M. Construction payment automation using blockchain-enabled smart contracts and robotic reality capture technologies. Automation in Construction 2021.

- Alzubi, K.; Alaloul, W.; Malkawi, A.; ... Automated monitoring technologies and construction productivity enhancement: Building projects case; Elsevier: 2023.

- Teizer, J.; Wolf, M.; Golovina, O.; ... Internet of Things (IoT) for integrating environmental and localization data in Building Information Modeling (BIM); researchgate.net: 2017.

- Banitaan, S.; Al-refai, G.; Almatarneh, S.; ... A review on artificial intelligence in the context of industry 4.0; researchgate.net: 2023.

- Kwak, E. Automatic 3D building model generation by integrating LiDAR and aerial images using a hybrid approach. 2013.

- Gubbi, J.; Buyya, R.; Marusic, S.; Palaniswami, M. Internet of Things (IoT): A vision, architectural elements, and future directions. Future Generation Computer Systems 2013, 29, 1645-1660. [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.; Kulinan, A.; Kim, T.; Park, M.; Park, S. Vision-based motion prediction for construction workers safety in real-time multi-camera system. Advanced Engineering … 2024.

- Morales, J.N. AI-driven project controls: integrated computer vision production tracking &AI-driven forecasting in building construction; ideals.illinois.edu: 2024.

- Xu, S.; Wang, J.; Shou, W.; Ngo, T.; Sadick, A.; ... Computer vision techniques in construction: a critical review. … Methods in Engineering 2021. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wilde, A.; Menzel, K.; Sheikh, M.; ... Computer vision for construction progress monitoring: A real-time object detection approach. Working Conference on … 2023. [CrossRef]

- …; Paulson, J.A.; Carron, A.; Zeilinger, M.N. Physics-Informed Machine Learning for Modeling and Control of Dynamical Systems. arXiv preprint arXiv … 2023.

- Boiko, A. Big data and machine learning. Practical step-by-step course for beginners. Available online: https://bigdataconstruction.com/ (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Casini, M. Construction 4.0: Advanced technology, tools and materials for the digital transformation of the construction industry; books.google.com: 2021.

- Kumar, S. System and method for computational simulation and augmented/virtual reality in a construction environment. US Patent 11,907,885 2024.

- Liang, R.; Huang, C.; Zhang, C.; Li, B.; Saydam, S.; ... Exploring the fusion potentials of data visualization and data analytics in the process of mining digitalization. IEEE … 2023.

- Chen, Y.; Huang, D.; Liu, Z.; Osmani, M.; Demian, P. Construction 4.0, Industry 4.0, and Building Information Modeling (BIM) for sustainable building development within the smart city; mdpi.com: 2022.

- Bock, T.; Linner, T. Robot oriented design; books.google.com: 2015.

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, L. Integrating BIM and AI for smart construction management: Current status and future directions. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2023. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, L. Roles of artificial intelligence in construction engineering and management: A critical review and future trends. Automation in Construction 2021.

- Farmer, E. Time and motion study; HM Stationery Office: 1921.

- Gilbreth, F. Bricklaying system; MC Clark Publishing Company: 1909.

- Gantt, H. Work, wages, and profits; Engineering magazine: 1913.

- Gantt, H. Organizing for work; Harcourt, Brace and Howe: 1919.

- Adrian, J.; Boyer, L. Modeling method-productivity. Journal of the Construction Division 1976. [CrossRef]

- Syverson, C. What determines productivity? Journal of Economic literature 2011.

- Modig, N.; Åhlström, P. This is lean: Resolving the efficiency paradox; nhpqi.ca: 2012.

- …; Farshidian, F.; Hutter, M.; Zeilinger, M.N. Bayesian multi-task learning MPC for robotic mobile manipulation. IEEE Robotics and … 2023.

- Ghanbari, J.; Zare, M. Review of Automation and Robotic in Advanced Construction Methods: A Case Study of Karaksa Hotel. New Approaches in Civil Engineering 2021.

- Bock, T. The future of construction automation: Technological disruption and the upcoming ubiquity of robotics. Automation in construction 2015.

- Ayele, S.; Fayek, A. A framework for total productivity measurement of industrial construction projects. Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering 2019. [CrossRef]

- Sacks, R.; Eastman, C.; Lee, G.; Teicholz, P. BIM handbook: A guide to building information modeling for owners, designers, engineers, contractors, and facility managers; books.google.com: 2018.

- Dave, B.; Kubler, S.; Främling, K.; Koskela, L. Opportunities for enhanced lean construction management using Internet of Things standards. Automation in construction 2016.

- Borrmann, A.; König, M.; Koch, C.; Beetz, J. Building information modeling: Why? what? how?; Springer: 2018.

- Dixit, S.; Sharma, K. An empirical study of major factors affecting productivity of construction projects. Emerging Trends in Civil Engineering: Select … 2020. [CrossRef]

- Sawhney, A.; Rubinsohn, S.; Luo, D. RICS Construction productivity report 2024. Available online: https://www.rics.org/news-insights/rics-construction-productivity-report-2024 (accessed on 11 May).

- Rathnayake, A.; Middleton, C. Systematic review of the literature on construction productivity. Journal of Construction Engineering … 2023. [CrossRef]

- Shan, M.; Li, Y.; Hwang, B.; Chua, J. Productivity metrics and its implementations in construction projects: A case study of Singapore; mdpi.com: 2021.

- Teicholz, P. Labor productivity declines in the construction industry: causes and remedies; 2004.

- Sacks, R.; Brilakis, I.; Pikas, E.; Xie, H.; ... Construction with digital twin information systems. Data-centric … 2020.

- Sacks, R.; Girolami, M.; Brilakis, I. Building information modelling, artificial intelligence and construction tech; Elsevier: 2020.

- Dubois, A.; Gadde, L. The construction industry as a loosely coupled system: implications for productivity and innovation. Construction management &economics 2002. [CrossRef]

- Winch, G. Managing construction projects; books.google.com: 2012.

- Love, P.; Gunasekaran, A. Concurrent engineering in the construction industry. Concurrent Engineering 1997. [CrossRef]

- Antunes, R.; Poshdar, M. Envision of an integrated information system for project-driven production in construction. arXiv preprint arXiv:1807.04966 2018.

- Antunes, R.; Gonzalez, V. A production model for construction: A theoretical framework; mdpi.com: 2015.

- Soliman, M.; Saurin, T.A. Lean-as-imagined differs from lean-as-done: the influence of complexity. Production Planning &Control 2022. [CrossRef]

- Howell, G.; Ballard, G.; Demirkesen, S. Why lean projects are safer. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 25th Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction, Heraklion, Greece, 2017; pp. 4-12.

- Salem, O.; Solomon, J.; Genaidy, A.; ... Lean construction: From theory to implementation. Journal of management … 2006. [CrossRef]

- Elghaish, F.; Abrishami, S.; Hosseini, M.R. Integrated project delivery with blockchain: An automated financial system. Automation in Construction 2020, 114, 103182. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; He, J.; Zhou, S. Sharing tacit knowledge for integrated project team flexibility: Case study of integrated project delivery. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2013, 139, 795-804.

- Kent, D.C.; Becerik-Gerber, B. Understanding construction industry experience and attitudes toward integrated project delivery. Journal of construction engineering and management 2010, 136, 815-825.

- Hijazi, A.A.; Perera, S.; Calheiros, R.N. A data model for integrating BIM and blockchain to enable a single source of truth for the construction supply chain data delivery. … , Construction and … 2023. [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum (WEF). Shaping the Future of Construction – An Action Plan to Accelerate Building Information Modeling (BIM) Adoption; World Economic Forum: Cologny, Switzerland, 2018.

- Schuldt, S.; Nicholson, M.; Adams, Y.; Delorit, J. Weather-related construction delays in a changing climate: a systematic state-of-the-art review; mdpi.com: 2021.

- Dong, R.; Muhammad, A.; Nauman, U. The Influence of Weather Conditions on Time, Cost, and Quality in Successful Construction Project Delivery; mdpi.com: 2025.

- Pryke, S. Successful Construction supply chain management: Concepts and case studies; John Wiley & Sons: 2020.

- Zhang, G.; Yang, Y.; Yang, G. Smart supply chain management in Industry 4.0: the review, research agenda and strategies in North America. Annals of operations research 2023. [CrossRef]

- D'Amico, L.; Glaeser, E.; Gyourko, J.; Kerr, W.; ... Why Has Construction Productivity Stagnated? The Role of Land-Use Regulation; nber.org: 2024.

- Womack, J.; Jones, D.; Roos, D. The machine that changed the world: The story of lean production--Toyota's secret weapon in the global car wars that is now revolutionizing world industry; books.google.com: 2007.

- Smith, P. BIM Implementation – Global Strategies. Procedia Engineering 2014, 85, 482-492. [CrossRef]

- Ouda, E.; Haggag, M. Automation in Modular Construction Manufacturing: A Comparative Analysis of Assembly Processes; mdpi.com: 2024.

- Conte, M.; Echeveste, M.; Formoso, C.; Bazzan, J. Synergies between Mass Customisation and Construction 4.0 Technologies; mdpi.com: 2022.

- Ng, M.; Graser, K.; Hall, D. Digital fabrication, BIM and early contractor involvement in design in construction projects: A comparative case study. Architectural Engineering and Design … 2023. [CrossRef]

- Geiger, M.; Schlicke, M.; Yang, B.; Nübel, K. Framework of an Implementation Strategy for a Modular Construction Toolkit Design in Construction Companies. Journal of Information Systems Engineering and Management 2025, Vol. 10 No. 34s (2025). [CrossRef]

- Shingo, S. Non-stock production: the Shingo system of continuous improvement; books.google.com: 1988.

- Shingo, S. Zero quality control: Source inspection and the poka-yoke system; taylorfrancis.com: 2021.

- Shingo, S.; Dillon, A. A study of the Toyota production system: From an Industrial Engineering Viewpoint; books.google.com: 2019.

- Liker, J. The Toyota way: 14 management principles from the world's greatest manufacturer; katalog.ub.uni-heidelberg.de: 2020.

- Imai, M. Kaizen: The key to Japan's competitive success; 1986.

- Rother, M.; Shook, J. Value-stream mapping to create value and eliminate muda; 1999.

- Womack, J.; Jones, D. Lean thinking—banish waste and create wealth in your corporation. Journal of the operational research … 1997. [CrossRef]

- Ohno, T. Toyota production system: beyond large-scale production; taylorfrancis.com: 1988.

- Ballard, H. The last planner system of production control; etheses.bham.ac.uk: 2000.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).