Submitted:

15 May 2025

Posted:

19 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Biomineralization Process and Efficiency Optimization

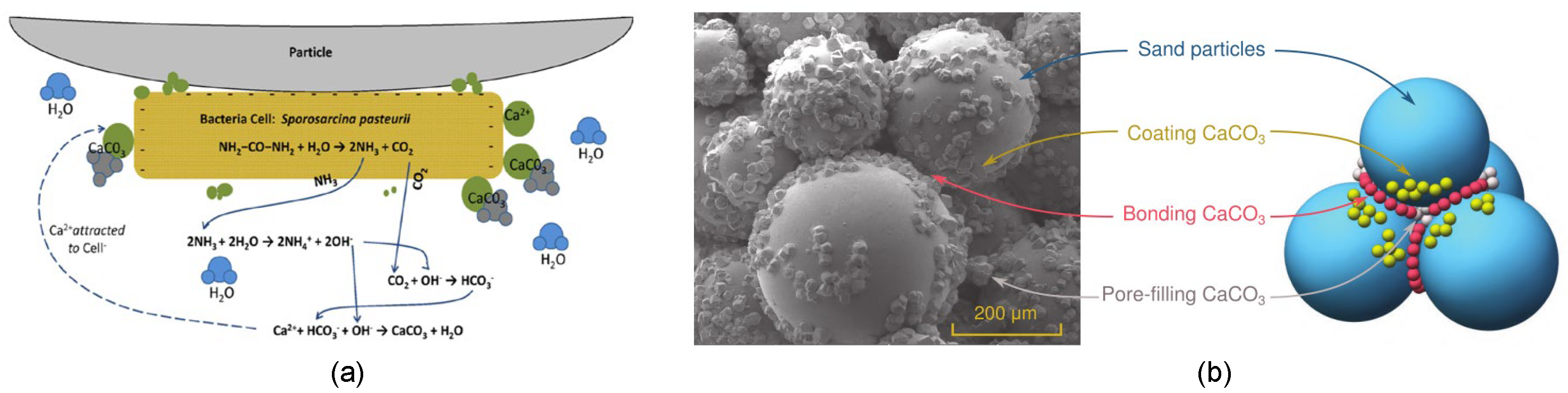

2.1. Traditional Biomineralization Process

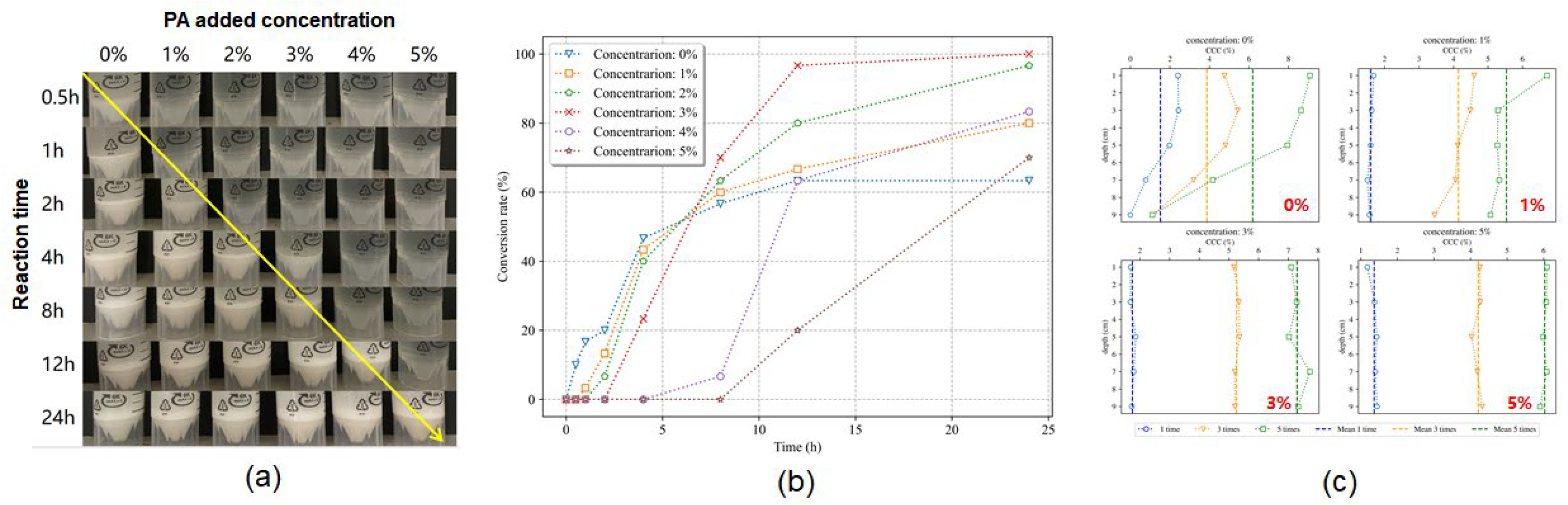

2.2. Biomineralization Efficiency Optimization

3. Multi-Investigations Of Biomineralization Erosion Control in Ocean Engineering

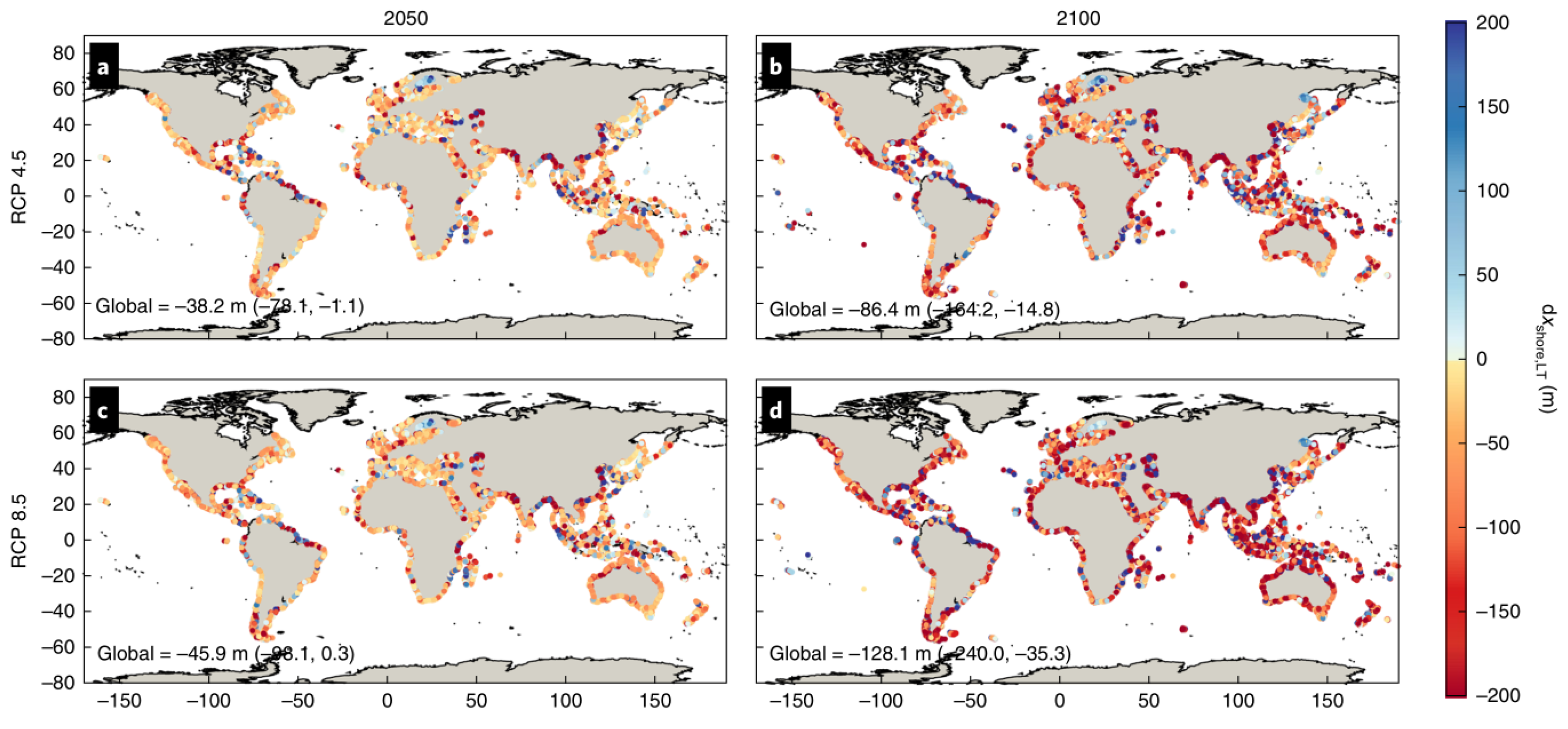

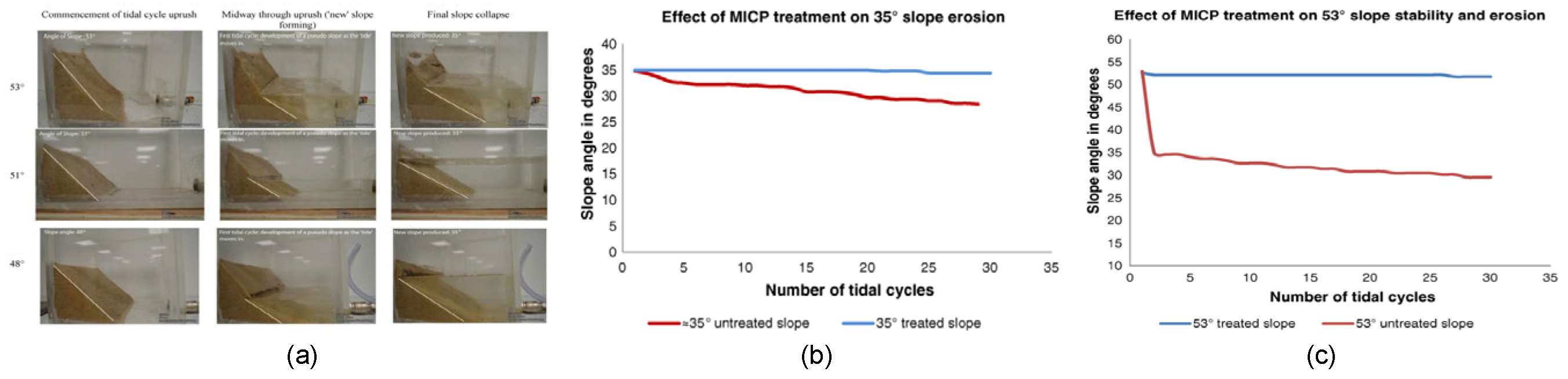

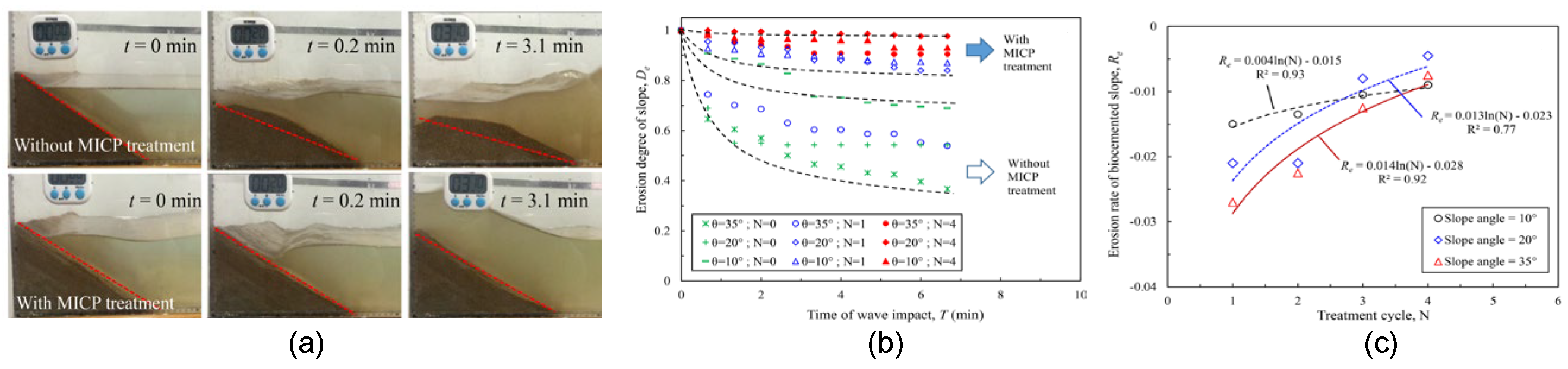

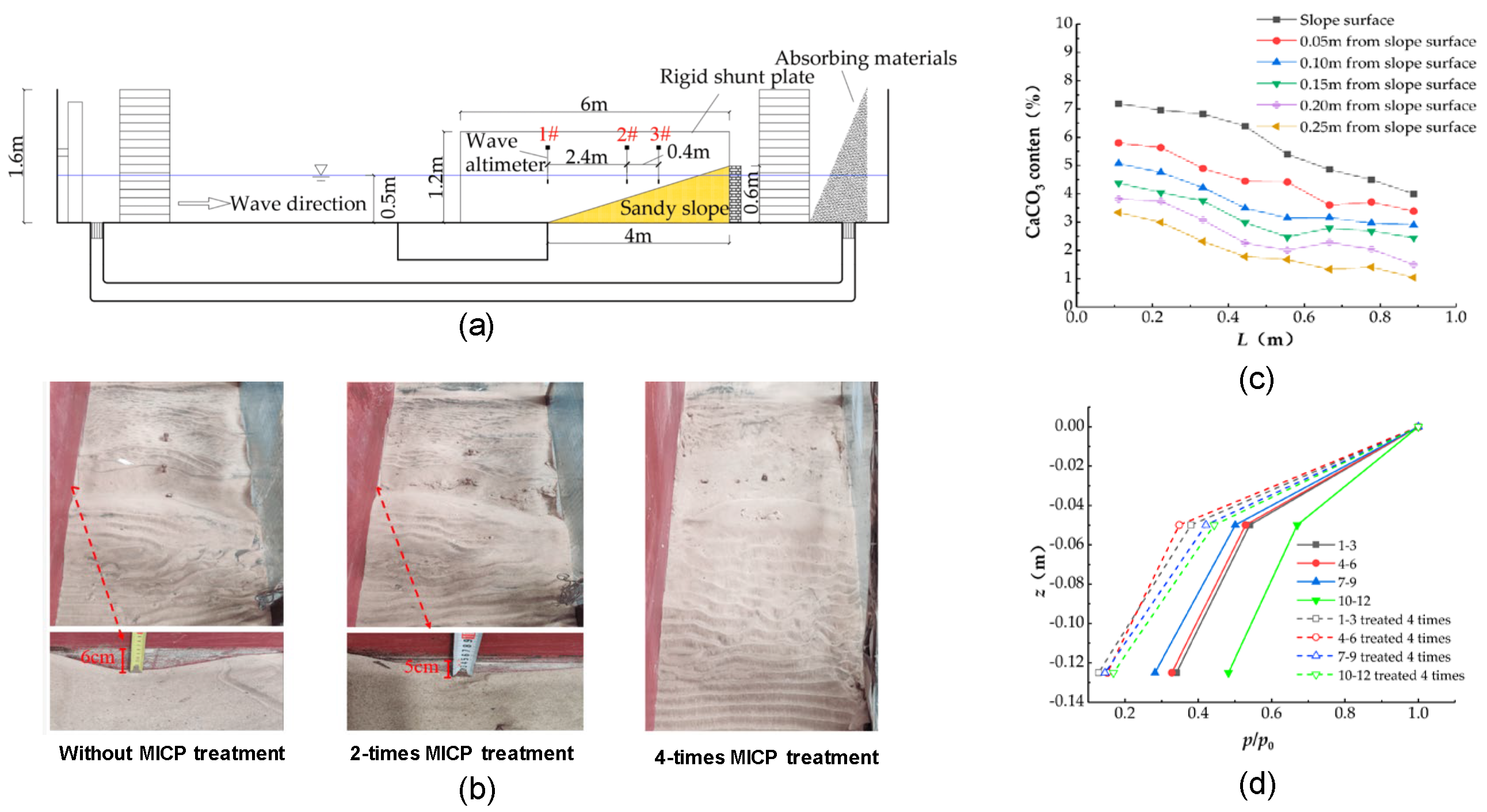

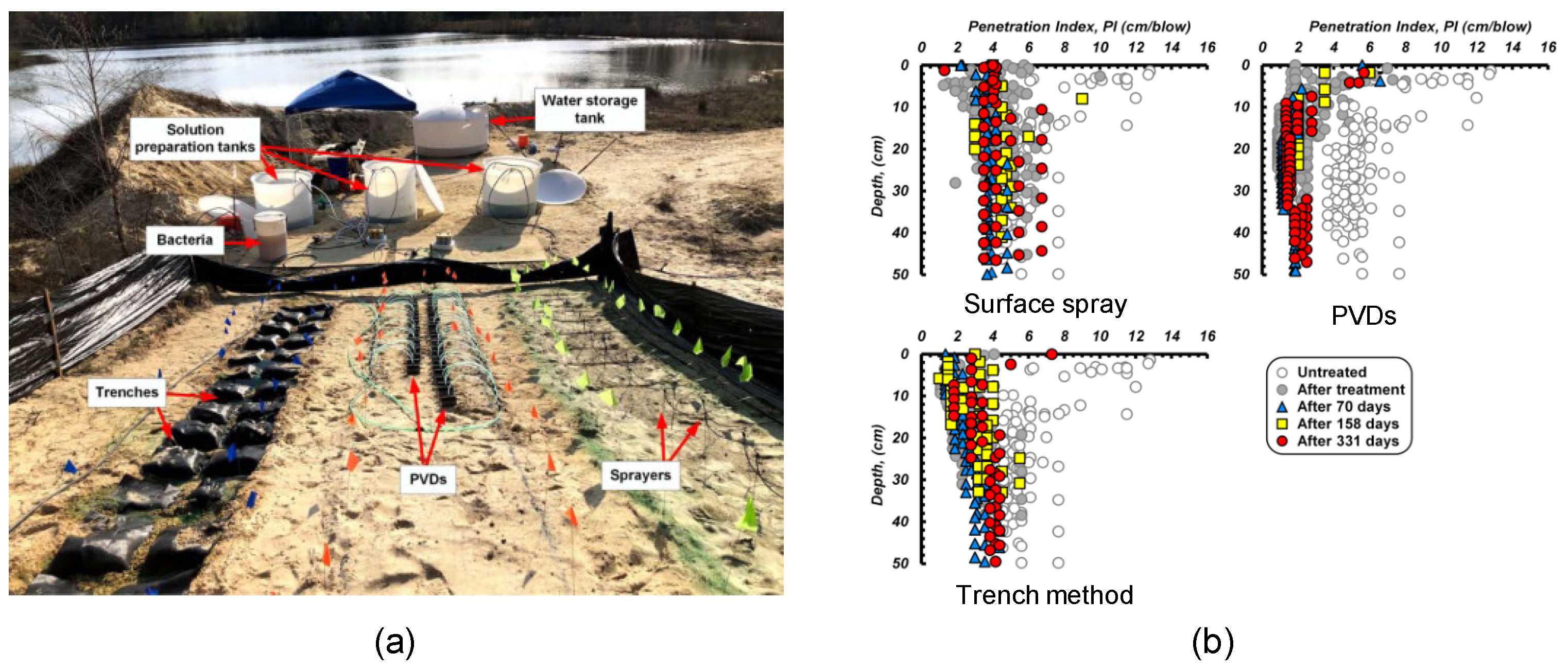

3.1. Erosion Control of Coastline

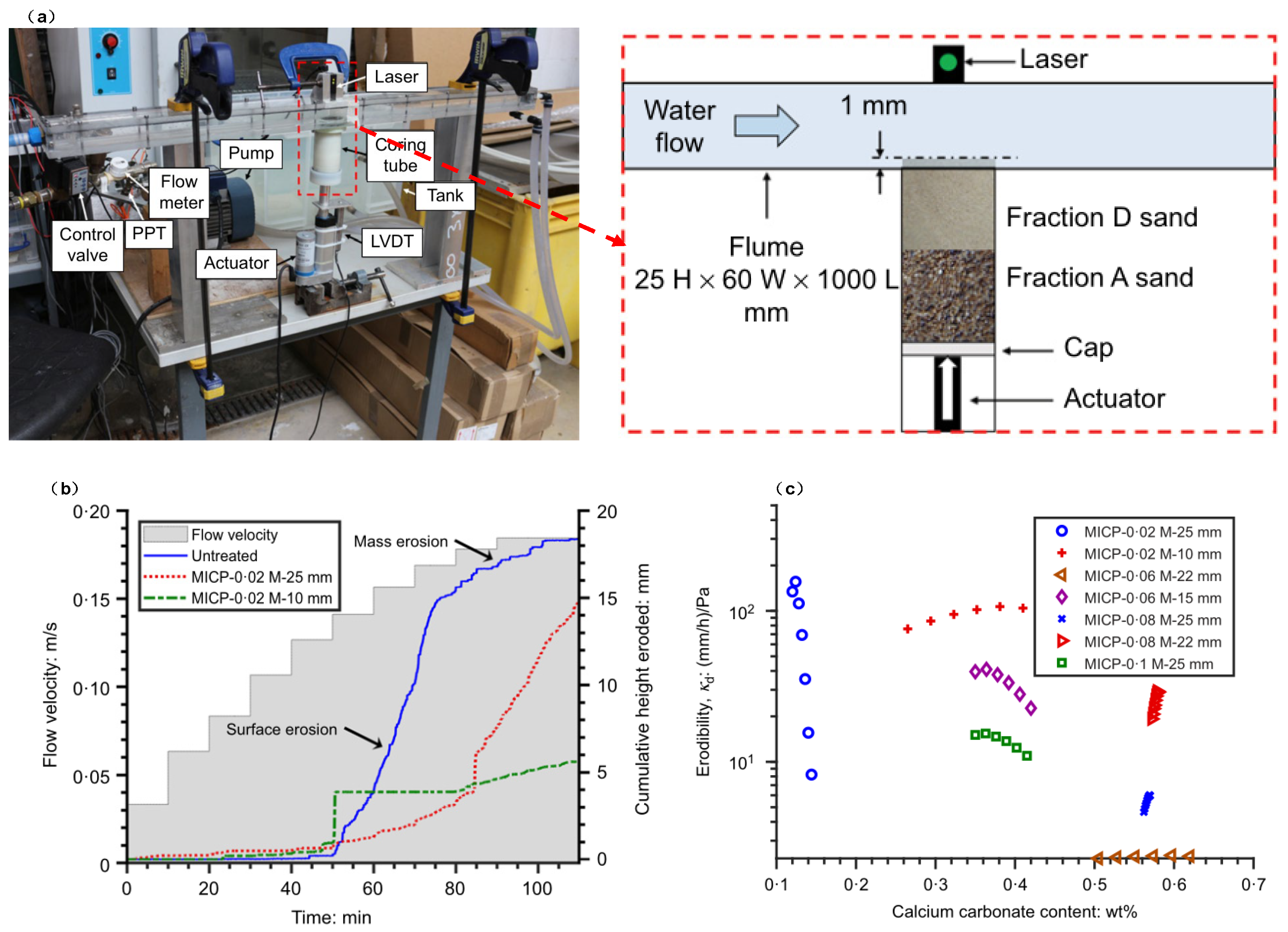

3.2. Local Scour Protection Around Monopile

3.3. Stability Evaluation of MICP Reinforced Seabed

4. Suggestions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The optimization of reinforcement methodology (mixing, grouting, immersion) and material formulation (polycarboxylic acid, PA) are conducive to a more uniform distribution of calcium carbonate. The addition of 3% polycarboxylic acid (PA) delays the onset of CaCO3 precipitation by >2 hours and acts as a non-bacterial nucleation template, facilitating spatially uniform distribution. Kinetic analysis of Ca2+ conversion confirmed complete ion utilization within 24 hours under optimized PA concentration (3%), yielding a compressive strength of 2.76 MPa after five treatment cycles.

- (2)

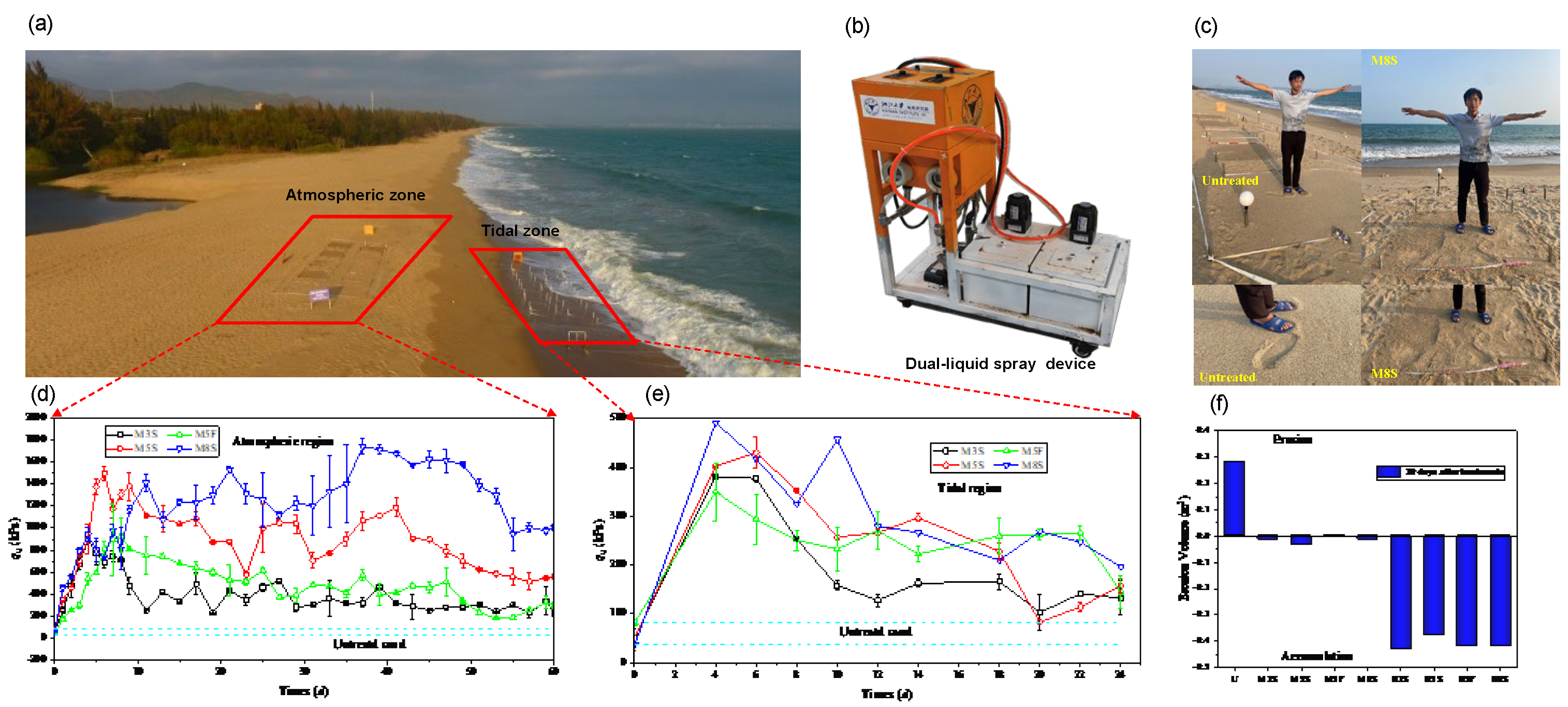

- The erosion resistance of coastline soil was investigated by erosion function apparatus (EFA) tests, tidal actions model test, wave actions model test and field applications. Field validations in Ahoskie and Sanya demonstrate the efficacy of MICP in coastal erosion control through tailored delivery systems and environmental adaptations. In Ahoskie, three delivery methods (surface spraying, PVDs, and trenches) achieved distinct performance: surface spraying formed a 7% CaCO3 crusts (73% surface strength improvement), PVDs enhanced subsurface layers (72% improvement at 30 cm depth), and trenches concentrated CaCO3 (9.9%) near gravel interfaces, collectively enabling the slope to withstand Hurricane Dorian over 331 days. Meanwhile, Sanya’s studies highlighted seawater-compatible MICP solutions, achieving maximum 1743 kPa penetration resistance in atmospheric zone and layered “M-shaped” CaCO3 precipitation in tidal regions. Comparatively, EICP under freshwater yielded weaker aggregates, with MICP’s spherical crystals outperforming EICP’s irregular structures. While tidal exposure degraded MICP durability, synergies between biomineralization and natural sedimentation underscored its ecological potential.

- (3)

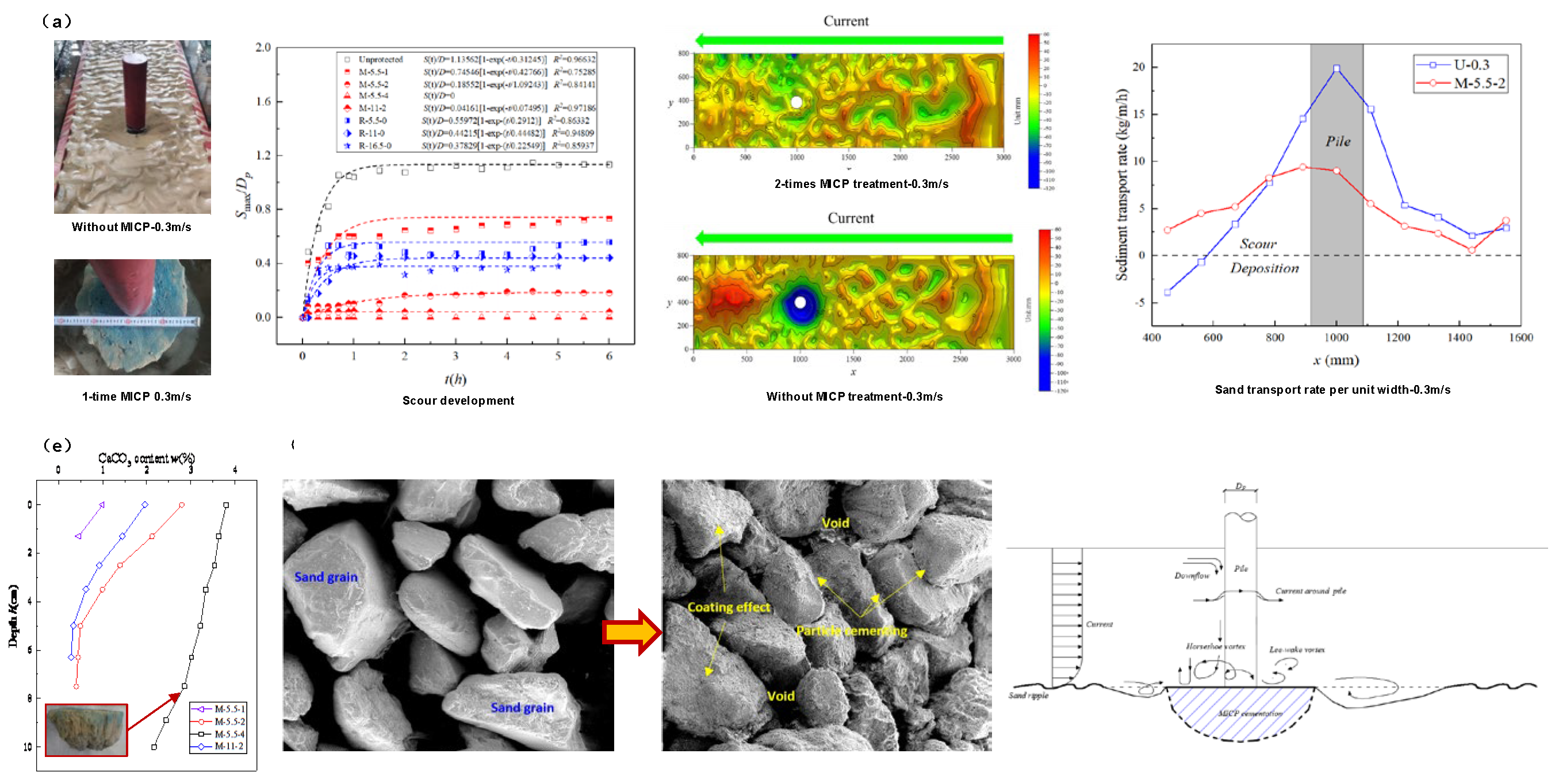

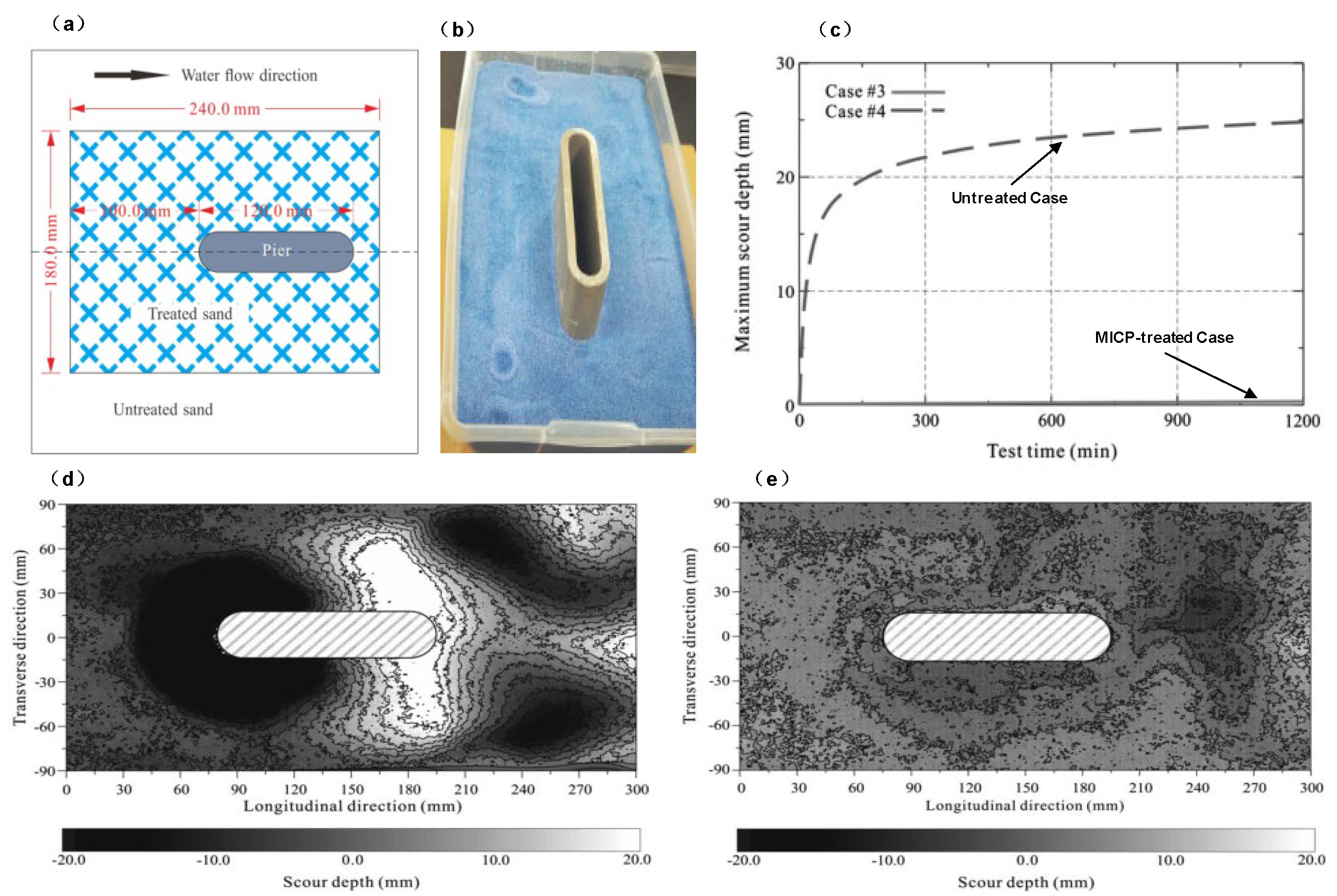

- MICP coupled with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) effectively mitigate local scour around monopile through biomineralization and polymer-enhanced crystal adhesion. Experimental studies reveal that MICP treatments (2-4 cycles) reduce maximum scour depth by 84-100% under unidirectional currents through the formation of a 4-9 cm MICP cemented cone stabilizing seabed sediment. It is necessary to consider the balance of MICP protective times and edge scour. MICP coupled with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) outperforms conventional methods, achieving 500-fold increases in critical shear stress (94.4 Pa) via dense vaterite crystallization at particle contacts and sustaining <0.3 mm erosion under extreme flows. Synergistic effects of polymer-modulated infiltration and biomineralization enable precise 5 cm-thick cemented layers without deep grouting.

- (4)

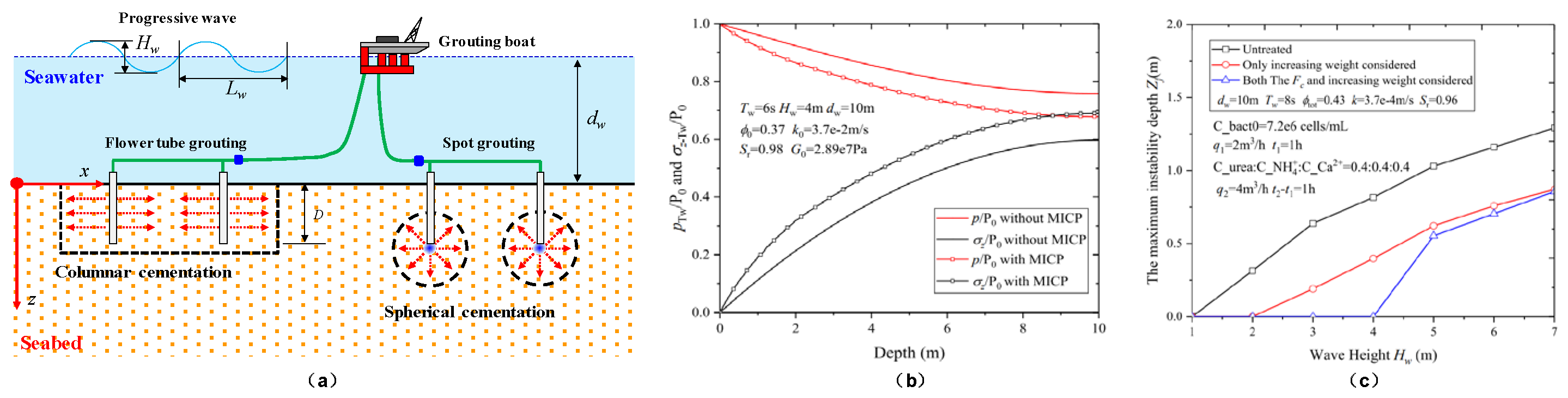

- In addition to erosion protection, MICP technology can also be used to reinforce the seabed and improve stability. The numerical model of MICP reaction for seabed reinforcement considering the wave actions, incorporating bacterial kinetics (suspended/attached phases), urea hydrolysis (Michaelis-Menten equation), and Darcy-driven convection-diffusion-reaction processes, can be used to analysis the seabed stability after MICP treatment. This framework accounts for CaCO3 induced porosity reduction and shear modulus enhancement, resolving wave-seabed-MICP interactions. Simulations reveal MICP increases seabed stability by amplifying vertical effective stress and reducing pore pressure. Surface CaCO3 clogging diminishes permeability and redistributes seepage forces, enhancing resistance to liquefaction. Comparative analyses confirm untreated seabed instability increases linearly with wave height, while MICP-treated seabed exhibit nonlinear stability gains through cohesive strength effects. Validated via unit tests and parametric studies, the model demonstrates MICP’s efficacy in mitigating wave-induced seabed liquefaction.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bird, E. C. (1985). Coastline changes. A global review.

- Zhang, K., Douglas, B. C., & Leatherman, S. P. (2004). Global warming and coastal erosion. Climatic change, 64, 41-58.

- Zhu, X., Linham, M. M., & Nicholls, R. J. (2010). Technologies for climate change adaptation-Coastal erosion and flooding. Danmarks Tekniske Universitet, Risø Nationallaboratoriet for Bæredygtig Energi.

- Pilkey, O. H., & Cooper, J. A. G. (2020). The last beach. Duke University Press.

- Barragán, J. M., & De Andrés, M. (2015). Analysis and trends of the world’s coastal cities and agglomerations. Ocean & Coastal Management, 114, 11-20.

- Ataie-Ashtiani, B., & Beheshti, A. A. (2006). Experimental investigation of clear-water local scour at pile groups. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 132(10), 1100-1104.

- Amini, A., Melville, B. W., Ali, T. M., & Ghazali, A. H. (2012). Clear-water local scour around pile groups in shallow-water flow. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 138(2), 177-185.

- Qi, W. G., Gao, F. P., Randolph, M. F., & Lehane, B. M. (2016). Scour effects on p–y curves for shallowly embedded piles in sand. Géotechnique, 66(8), 648-660.

- Sumer, B. M., Fredsøe, J., & Christiansen, N. (1992). Scour around vertical pile in waves. Journal of waterway, port, coastal, and ocean engineering, 118(1), 15-31.

- Qi, W. G., Li, Y. X., Xu, K., & Gao, F. P. (2019). Physical modelling of local scour at twin piles under combined waves and current. Coastal Engineering, 143, 63-75.

- Sumer, B. M., Whitehouse, R. J., & Tørum, A. (2001). Scour around coastal structures: a summary of recent research. Coastal engineering, 44(2), 153-190.

- Raudkivi, A. J., & Ettema, R. (1983). Clear-water scour at cylindrical piers. Journal of hydraulic engineering, 109(3), 338-350.

- Whitehouse, R. (1998). Scour at marine structures: A manual for practical applications. Thomas Telford.

- Lin, Y., & Lin, C. (2019). Effects of scour-hole dimensions on lateral behavior of piles in sands. Computers and Geotechnics, 111, 30-41.

- Wang, H., Wang, L., Hong, Y., Mašín, D., Li, W., He, B., & Pan, H. (2021). Centrifuge testing on monotonic and cyclic lateral behavior of large-diameter slender piles in sand. Ocean Engineering, 226, 108299.

- Guo, X., Liu, J., Yi, P., Feng, X., & Han, C. (2022). Effects of local scour on failure envelopes of offshore monopiles and caissons. Applied Ocean Research, 118, 103007.

- Yamamoto, T., Koning, H. L., Sellmeijer, H., & Van Hijum, E. P. (1978). On the response of a poro-elastic bed to water waves. Journal of Fluid mechanics, 87(1), 193-206.

- Sakai, T., Hatanaka, K., & Mase, H. (1992). Wave-induced effective stress in seabed and its momentary liquefaction. Journal of waterway, port, coastal, and ocean engineering, 118(2), 202-206.

- Mory, M., Michallet, H., Bonjean, D., Piedra-Cueva, I., Barnoud, J. M., Foray, P., ... & Breul, P. (2007). A field study of momentary liquefaction caused by waves around a coastal structure. Journal of Waterway, Port, Coastal, and Ocean Engineering, 133(1), 28-38.

- Chávez, V., Mendoza, E., Silva, R., Silva, A., & Losada, M. A. (2017). An experimental method to verify the failure of coastal structures by wave induced liquefaction of clayey soils. Coastal Engineering, 123, 1-10.

- Young, Y. L., White, J. A., Xiao, H., & Borja, R. I. (2009). Liquefaction potential of coastal slopes induced by solitary waves. Acta Geotechnica, 4, 17-34.

- Wang, Y., Wang, Q., Cao, R., Gao, G., Feng, X., Yin, B., ... & Lv, X. (2025). Pressure characteristics of two-dimensional topography in wave-induced seabed liquefaction. Physics of Fluids, 37(1).

- Zhao, H. Y., Jeng, D. S., & Liao, C. C. (2016). Parametric study of the wave-induced residual liquefaction around an embedded pipeline. Applied Ocean Research, 55, 163-180.

- Chen, W., Fang, D., Chen, G., Jeng, D., Zhu, J., & Zhao, H. (2018). A simplified quasi-static analysis of wave-induced residual liquefaction of seabed around an immersed tunnel. Ocean Engineering, 148, 574-587.

- Kirca, V. O., Sumer, B. M., & Fredsøe, J. (2012, June). Residual liquefaction under standing waves. In ISOPE International Ocean and Polar Engineering Conference (pp. ISOPE-I). ISOPE.

- Jeng, D. S., Chen, L., Liao, C., & Tong, D. (2019). A numerical approach to determine wave (current)-induced residual responses in a layered seabed. Journal of Coastal Research, 35(6), 1271-1284.

- Vousdoukas, M. I., Ranasinghe, R., Mentaschi, L., Plomaritis, T. A., Athanasiou, P., Luijendijk, A., & Feyen, L. (2020). Sandy coastlines under threat of erosion. Nature climate change, 10(3), 260-263.

- Williams, A. T., Rangel-Buitrago, N., Pranzini, E., & Anfuso, G. (2018). The management of coastal erosion. Ocean & coastal management, 156, 4-20.

- Wang, C., Wu, Q., Zhang, H., & Liang, F. (2024). Effect of scour remediation by solidified soil on lateral response of monopile supporting offshore wind turbines using numerical model. Applied Ocean Research, 150, 104143.

- Whitehouse, R. J., Harris, J. M., Sutherland, J., & Rees, J. (2011). The nature of scour development and scour protection at offshore windfarm foundations. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 62(1), 73-88.

- Chiew, Y. M. (1992). Scour protection at bridge piers. Journal of hydraulic engineering, 118(9), 1260-1269.

- Pade, C., & Guimaraes, M. (2007). The CO2 uptake of concrete in a 100 year perspective. Cement and concrete research, 37(9), 1348-1356.

- Chen, Y., Han, Y., Zhang, X., Sarajpoor, S., Zhang, S., & Yao, X. (2023). Experimental study on permeability and strength characteristics of MICP-treated calcareous sand. Biogeotechnics, 1(3), 100034.

- Peng, S., Di, H., Fan, L., Fan, W., & Qin, L. (2020). Factors affecting permeability reduction of MICP for fractured rock. Frontiers in Earth Science, 8, 217.

- Song, C., & Elsworth, D. (2024). Stress sensitivity of permeability in high-permeability sandstone sealed with microbially-induced calcium carbonate precipitation. Biogeotechnics, 2(1), 100063.

- Yu, T., Souli, H., Pechaud, Y., & Fleureau, J. M. (2021). Review on engineering properties of MICP-treated soils. Geomechanics and Engineering, 27(1), 13-30.

- Lin, H., Suleiman, M. T., & Brown, D. G. (2020). Investigation of pore-scale CaCO3 distributions and their effects on stiffness and permeability of sands treated by microbially induced carbonate precipitation (MICP). Soils and Foundations, 60(4), 944-961.

- Konstantinou, C., Wang, Y., & Biscontin, G. (2023). A systematic study on the influence of grain characteristics on hydraulic and mechanical performance of MICP-treated porous media. Transport in Porous Media, 147(2), 305-330.

- Wu, C., Chu, J., Wu, S., & Hong, Y. (2019). 3D characterization of microbially induced carbonate precipitation in rock fracture and the resulted permeability reduction. Engineering Geology, 249, 23-30.

- Mujah, D., Cheng, L., & Shahin, M. A. (2019). Microstructural and geomechanical study on biocemented sand for optimization of MICP process. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, 31(4), 04019025.

- Liu, S., & Gao, X. (2020). Evaluation of the anti-erosion characteristics of an MICP coating on the surface of tabia. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, 32(10), 04020304.

- Ma, G., He, X., Jiang, X., Liu, H., Chu, J., & Xiao, Y. (2021). Strength and permeability of bentonite-assisted biocemented coarse sand. Canadian Geotechnical Journal, 58(7), 969-981.

- Sang, G., Lunn, R. J., El Mountassir, G., & Minto, J. M. (2023). Meter-scale MICP improvement of medium graded very gravelly sands: lab measurement, transport modelling, mechanical and microstructural analysis. Engineering Geology, 324, 107275.

- Yu, X., & Rong, H. (2022). Seawater based MICP cements two/one-phase cemented sand blocks. Applied Ocean Research, 118, 102972.

- Lin, W., Gao, Y., Lin, W., Zhuo, Z., Wu, W., & Cheng, X. (2023). Seawater-based bio-cementation of natural sea sand via microbially induced carbonate precipitation. Environmental Technology & Innovation, 29, 103010.

- Boquet, E., Boronat, A., & Ramos-Cormenzana, A. (1973). Production of calcite (calcium carbonate) crystals by soil bacteria is a general phenomenon. Nature, 246(5434), 527-529.

- Whiffin, V. S. (2004). Microbial CaCO3 precipitation for the production of biocement (Doctoral dissertation, Murdoch University).

- Mitchell, J. K., & Santamarina, J. C. (2005). Biological considerations in geotechnical engineering. Journal of geotechnical and geoenvironmental engineering, 131(10), 1222-1233.

- Hosseini, S. M. J., Guan, D., & Cheng, L. (2024). Ground improvement with a single injection of a high-performance all-in-one MICP solution. Geomicrobiology Journal, 41(6), 636-647.

- Arpajirakul, S., Pungrasmi, W., & Likitlersuang, S. (2021). Efficiency of microbially-induced calcite precipitation in natural clays for ground improvement. Construction and Building Materials, 282, 122722.

- Wani, K. S., & Mir, B. A. (2022). Application of bio-engineering for marginal soil improvement: an eco-friendly ground improvement technique. Indian Geotechnical Journal, 52(5), 1097-1115.

- Lin, H., Suleiman, M. T., Jabbour, H. M., Brown, D. G., & Kavazanjian Jr, E. (2016). Enhancing the axial compression response of pervious concrete ground improvement piles using biogrouting. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 142(10), 04016045.

- Lai, H. J., Cui, M. J., & Chu, J. (2023). Effect of pH on soil improvement using one-phase-low-pH MICP or EICP biocementation method. Acta Geotechnica, 18(6), 3259-3272.

- Zhao, Q., Li, L., Li, C., Li, M., Amini, F., & Zhang, H. (2014). Factors affecting improvement of engineering properties of MICP-treated soil catalyzed by bacteria and urease. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, 26(12), 04014094.

- Karimian, A., & Hassanlourad, M. (2022). Mechanical behaviour of MICP-treated silty sand. Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment, 81(7), 285.

- Wang, Y. J., Chen, W. B., Li, P. L., Yin, Z. Y., Yin, J. H., & Jiang, N. J. (2024). Soil improvement using biostimulated MICP: Mechanical and biochemical experiments, reactive transport modelling, and parametric analysis. Computers and Geotechnics, 172, 106446.

- Van Wijngaarden, W. K., Vermolen, F. J., Van Meurs, G. A. M., & Vuik, C. (2011). Modelling biogrout: a new ground improvement method based on microbial-induced carbonate precipitation. Transport in porous media, 87, 397-420.

- Cheng, L., & Shahin, M. A. (2016). Urease active bioslurry: a novel soil improvement approach based on microbially induced carbonate precipitation. Canadian Geotechnical Journal, 53(9), 1376-1385.

- Wang, Y., Konstantinou, C., Soga, K., Biscontin, G., & Kabla, A. J. (2022). Use of microfluidic experiments to optimize MICP treatment protocols for effective strength enhancement of MICP-treated sandy soils. Acta Geotechnica, 17(9), 3817-3838.

- Teng, F., Sie, Y. C., & Ouedraogo, C. (2021). Strength improvement in silty clay by microbial-induced calcite precipitation. Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment, 80(8), 6359-6371.

- Chae, S. H., Chung, H., & Nam, K. (2021). Evaluation of microbially Induced calcite precipitation (MICP) methods on different soil types for wind erosion control. Environmental Engineering Research, 26(1).

- Wang, Y. N., Li, S. K., Li, Z. Y., & Garg, A. (2023). Exploring the application of the MICP technique for the suppression of erosion in granite residual soil in Shantou using a rainfall erosion simulator. Acta Geotechnica, 18(6), 3273-3285.

- Wang, Z., Zhang, N., Jin, Y., Li, Q., & Xu, J. (2021). Application of microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation (MICP) in sand embankments for scouring/erosion control. Marine Georesources & Geotechnology, 39(12), 1459-1471.

- Liu, S., & Gao, X. (2020a). Evaluation of the anti-erosion characteristics of an MICP coating on the surface of tabia. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, 32(10), 04020304.

- Liu, S., Wang, R., Yu, J., Peng, X., Cai, Y., & Tu, B. (2020b). Effectiveness of the anti-erosion of an MICP coating on the surfaces of ancient clay roof tiles. Construction and Building Materials, 243, 118202.

- Liu, S., Du, K., Huang, W., Wen, K., Amini, F., & Li, L. (2021). Improvement of erosion-resistance of bio-bricks through fiber and multiple MICP treatments. Construction and Building Materials, 271, 121573.

- Jiang, N. J., Soga, K., & Kuo, M. (2017). Microbially induced carbonate precipitation for seepage-induced internal erosion control in sand–clay mixtures. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 143(3), 04016100.

- Jiang, N. J., & Soga, K. (2019). Erosional behavior of gravel-sand mixtures stabilized by microbially induced calcite precipitation (MICP). Soils and Foundations, 59(3), 699-709.

- Chek, A., Crowley, R., Ellis, T. N., Durnin, M., & Wingender, B. (2021). Evaluation of factors affecting erodibility improvement for MICP-treated beach sand. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 147(3), 04021001.

- Li, K., & Wang, Y. (2024). The impact of Microbially Induced Calcite Precipitation (MICP) on sand internal erosion resistance: A microfluidic study. Transportation Geotechnics, 49, 101404.

- Meng, H., Gao, Y., He, J., Qi, Y., & Hang, L. (2021). Microbially induced carbonate precipitation for wind erosion control of desert soil: Field-scale tests. Geoderma, 383, 114723.

- Cheng, Y. J., Tang, C. S., Pan, X. H., Liu, B., Xie, Y. H., Cheng, Q., & Shi, B. (2021). Application of microbial induced carbonate precipitation for loess surface erosion control. Engineering Geology, 294, 106387.

- Zhang, Z., Lu, H., Tang, X., Liu, K., Ye, L., & Ma, G. (2024). Field investigation of the feasibility of MICP for Mitigating Natural Rainfall-Induced erosion in gravelly clay slope. Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment, 83(10), 406.

- Xiao, Y., Ma, G., Wu, H., Lu, H., & Zaman, M. (2022). Rainfall-induced erosion of biocemented graded slopes. International Journal of Geomechanics, 22(1), 04021256.

- Liu, B., Tang, C. S., Pan, X. H., Cheng, Q., Xu, J. J., & Lv, C. (2025). Mitigating rainfall induced soil erosion through bio-approach: From laboratory test to field trail. Engineering Geology, 344, 107842.

- Sun, X., Miao, L., Wang, H., Wu, L., Fan, G., & Xia, J. (2022). Sand foreshore slope stability and erosion mitigation based on microbiota and enzyme mix–induced carbonate precipitation. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 148(8), 04022058.

- Rodríguez, R. F., & Cardoso, R. (2022). Study of biocementation treatment to prevent erosion by concentrated water flow in a small-scale sand slope. Transportation Geotechnics, 37, 100873.

- Jongvivatsakul, P., Janprasit, K., Nuaklong, P., Pungrasmi, W., & Likitlersuang, S. (2019). Investigation of the crack healing performance in mortar using microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation (MICP) method. Construction and Building Materials, 212, 737-744.

- Sun, X., Miao, L., Wu, L., & Wang, H. (2021). Theoretical quantification for cracks repair based on microbially induced carbonate precipitation (MICP) method. Cement and Concrete Composites, 118, 103950.

- Choi, S. G., Wang, K., Wen, Z., & Chu, J. (2017). Mortar crack repair using microbial induced calcite precipitation method. Cement and Concrete Composites, 83, 209-221.

- Intarasoontron, J., Pungrasmi, W., Nuaklong, P., Jongvivatsakul, P., & Likitlersuang, S. (2021). Comparing performances of MICP bacterial vegetative cell and microencapsulated bacterial spore methods on concrete crack healing. Construction and Building Materials, 302, 124227.

- Nuaklong, P., Jongvivatsakul, P., Phanupornprapong, V., Intarasoontron, J., Shahzadi, H., Pungrasmi, W., ... & Likitlersuang, S. (2023). Self-repairing of shrinkage crack in mortar containing microencapsulated bacterial spores. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, 23, 3441-3454.

- Jiang, L., Xia, H., Hu, S., Zhao, X., Wang, W., Zhang, Y., & Li, Z. (2024). Crack-healing ability of concrete enhanced by aerobic-anaerobic bacteria and fibers. Cement and Concrete Research, 183, 107585.

- Zamani, A., Xiao, P., Baumer, T., Carey, T. J., Sawyer, B., DeJong, J. T., & Boulanger, R. W. (2021). Mitigation of liquefaction triggering and foundation settlement by MICP treatment. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 147(10), 04021099.

- O’Donnell, S. T., Kavazanjian Jr, E., & Rittmann, B. E. (2017a). MIDP: Liquefaction mitigation via microbial denitrification as a two-stage process. II: MICP. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 143(12), 04017095.

- O’Donnell, S. T., Rittmann, B. E., & Kavazanjian Jr, E. (2017b). MIDP: Liquefaction mitigation via microbial denitrification as a two-stage process. I: Desaturation. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 143(12), 04017094.

- Han, Z., Zhang, J., Bian, H., Yue, J., Xiao, J., & Wei, Y. (2024). Study on Liquefaction-Resistance Performance of MICP-Cemented Sands: Applying Centrifuge Shake Table Tests. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 150(8), 06024004.

- Ahenkorah, I., Rahman, M. M., Karim, M. R., & Beecham, S. (2024). Cyclic liquefaction resistance of MICP-and EICP-treated sand in simple shear conditions: A benchmarking with the critical state of untreated sand. Acta Geotechnica, 19(9), 5891-5913.

- Xiao, P., Liu, H., Xiao, Y., Stuedlein, A. W., & Evans, T. M. (2018). Liquefaction resistance of bio-cemented calcareous sand. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering, 107, 9-19.

- Xiao, Y., Zhang, Z., Stuedlein, A. W., & Evans, T. M. (2021). Liquefaction modeling for biocemented calcareous sand. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 147(12), 04021149.

- Zhou, Y., Zhang, Y., Geng, W., He, J., & Gao, Y. (2023). Evaluation of liquefaction resistance for single-and multi-phase SICP-treated sandy soil using shaking table test. Acta Geotechnica, 18(11), 6007-6025.

- Zhang, X., Chen, Y., Liu, H., Zhang, Z., & Ding, X. (2020). Performance evaluation of a MICP-treated calcareous sandy foundation using shake table tests. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering, 129, 105959.

- Darby, K. M., Hernandez, G. L., DeJong, J. T., Boulanger, R. W., Gomez, M. G., & Wilson, D. W. (2019). Centrifuge model testing of liquefaction mitigation via microbially induced calcite precipitation. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 145(10), 04019084.

- Kanwal, M., Khushnood, R. A., Adnan, F., Wattoo, A. G., & Jalil, A. (2023). Assessment of the MICP potential and corrosion inhibition of steel bars by biofilm forming bacteria in corrosive environment. Cement and Concrete Composites, 137, 104937.

- Sun, X., Wai, O. W., Xie, J., & Li, X. (2023). Biomineralization to prevent microbially induced corrosion on concrete for sustainable marine infrastructure. Environmental science & technology, 58(1), 522-533.

- Umar, M., Kassim, K. A., & Chiet, K. T. P. (2016). Biological process of soil improvement in civil engineering: A review. Journal of Rock Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering, 8(5), 767-774.

- Rajasekar, A., Wilkinson, S., & Moy, C. K. (2021). MICP as a potential sustainable technique to treat or entrap contaminants in the natural environment: A review. Environmental Science and Ecotechnology, 6, 100096.

- Mujah, D., Shahin, M. A., & Cheng, L. (2017). State-of-the-art review of biocementation by microbially induced calcite precipitation (MICP) for soil stabilization. Geomicrobiology Journal, 34(6), 524-537.

- Zhang, K., Tang, C. S., Jiang, N. J., Pan, X. H., Liu, B., Wang, Y. J., & Shi, B. (2023). Microbial-induced carbonate precipitation (MICP) technology: a review on the fundamentals and engineering applications. Environmental Earth Sciences, 82(9), 229.

- Fu, T., Saracho, A. C., & Haigh, S. K. (2023). Microbially induced carbonate precipitation (MICP) for soil strengthening: A comprehensive review. Biogeotechnics, 1(1), 100002.

- Wang, Z., Zhang, N., Cai, G., Jin, Y., Ding, N., & Shen, D. (2017). Review of ground improvement using microbial induced carbonate precipitation (MICP). Marine Georesources & Geotechnology, 35(8), 1135-1146.

- Gebru, K. A., Kidanemariam, T. G., & Gebretinsae, H. K. (2021). Bio-cement production using microbially induced calcite precipitation (MICP) method: A review. Chemical Engineering Science, 238, 116610.

- Fouladi, A. S., Arulrajah, A., Chu, J., & Horpibulsuk, S. (2023). Application of Microbially Induced Calcite Precipitation (MICP) technology in construction materials: A comprehensive review of waste stream contributions. Construction and Building Materials, 388, 131546.

- Wang, Y., Sun, X., Miao, L., Wang, H., Wu, L., Shi, W., & Kawasaki, S. (2024). State-of-the-art review of soil erosion control by MICP and EICP techniques: Problems, applications, and prospects. Science of the Total Environment, 912, 169016.

- Kumar, A., Song, H. W., Mishra, S., Zhang, W., Zhang, Y. L., Zhang, Q. R., & Yu, Z. G. (2023). Application of microbial-induced carbonate precipitation (MICP) techniques to remove heavy metal in the natural environment: A critical review. Chemosphere, 318, 137894.

- Harran, R., Terzis, D., & Laloui, L. (2023). Mechanics, modeling, and upscaling of biocemented soils: a review of breakthroughs and challenges. International Journal of Geomechanics, 23(9), 03123004.

- DeJong, J. T., Mortensen, B. M., Martinez, B. C., & Nelson, D. C. (2010). Bio-mediated soil improvement. Ecological engineering, 36(2), 197-210.

- Wu, H., Wu, W., Liang, W., Dai, F., Liu, H., & Xiao, Y. (2023). 3D DEM modeling of biocemented sand with fines as cementing agents. International Journal for Numerical and Analytical Methods in Geomechanics, 47(2), 212-240.

- Stocks-Fischer, S., Galinat, J. K., & Bang, S. S. (1999). Microbiological precipitation of CaCO3. Soil biology and biochemistry, 31(11), 1563-1571.

- Lin, W., Gao, Y., Lin, W., Zhuo, Z., Wu, W., & Cheng, X. (2023). Seawater-based bio-cementation of natural sea sand via microbially induced carbonate precipitation. Environmental Technology & Innovation, 29, 103010.

- Silva-Castro, G. A., Uad, I., Rivadeneyra, A., Vilchez, J. I., Martin-Ramos, D., González-López, J., & Rivadeneyra, M. A. (2013). Carbonate precipitation of bacterial strains isolated from sediments and seawater: formation mechanisms. Geomicrobiology Journal, 30(9), 840-850.

- Kang, B., Wang, H., Zha, F., Liu, C., Zhou, A., & Ban, R. (2025). Exploring the Uniformity of MICP Solidified Fine Particle Silt with Different Sample Preparation Methods. Biogeotechnics, 100163.

- Zhu, Y. Q., Li, Y. J., Sun, X. Y., Guo, Z., Rui, S. J., & Zheng, D. Q. (2025). A one-phase injection method to improve the strength and uniformity in MICP with polycarboxylic acid added. Acta Geotechnica, 1-13.

- Clarà Saracho, A., Haigh, S. K., & Ehsan Jorat, M. (2021). Flume study on the effects of microbial induced calcium carbonate precipitation (MICP) on the erosional behaviour of fine sand. Géotechnique, 71(12), 1135-1149.

- Salifu, E., MacLachlan, E., Iyer, K. R., Knapp, C. W., & Tarantino, A. (2016). Application of microbially induced calcite precipitation in erosion mitigation and stabilisation of sandy soil foreshore slopes: A preliminary investigation. Engineering Geology, 201, 96-105.

- Kou, H. L., Wu, C. Z., Ni, P. P., & Jang, B. A. (2020). Assessment of erosion resistance of biocemented sandy slope subjected to wave actions. Applied Ocean Research, 105, 102401.

- Li, Y., Xu, Q., Li, Y., Li, Y., & Liu, C. (2022a). Application of microbial-induced calcium carbonate precipitation in wave erosion protection of the sandy slope: An experimental study. Sustainability, 14(20), 12965.

- Ghasemi, P., & Montoya, B. M. (2022). Field implementation of microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation for surface erosion reduction of a coastal plain sandy slope. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 148(9), 04022071.

- Li, Y., Guo, Z., Wang, L., Zhu, Y., & Rui, S. (2024). Field implementation to resist coastal erosion of sandy slope by eco-friendly methods. Coastal Engineering, 189, 104489.

- Li, Y., Guo, Z., Wang, L., Yang, H., Li, Y., & Zhu, J. (2022b). An innovative eco-friendly method for scour protection around monopile foundation. Applied Ocean Research, 123, 103177.

- Zhu, T., He, R., Hosseini, S. M. J., He, S., Cheng, L., Guo, Y., & Guo, Z. (2024). Influence of precast microbial reinforcement on lateral responses of monopiles. Ocean Engineering, 307, 118211.

- Wang, X., Tao, J., Bao, R., Tran, T., & Tucker-Kulesza, S. (2018). Surficial soil stabilization against water-induced erosion using polymer-modified microbially induced carbonate precipitation. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, 30(10), 04018267.

- Martinez, B. C., DeJong, J. T., & Ginn, T. R. (2014). Bio-geochemical reactive transport modeling of microbial induced calcite precipitation to predict the treatment of sand in one-dimensional flow. Computers and Geotechnics, 58, 1-13.

- Fauriel, S., & Laloui, L. (2012). A bio-chemo-hydro-mechanical model for microbially induced calcite precipitation in soils. Computers and Geotechnics, 46, 104-120.

- Wang, X., & Nackenhorst, U. (2020). A coupled bio-chemo-hydraulic model to predict porosity and permeability reduction during microbially induced calcite precipitation. Advances in Water Resources, 140, 103563.

- Bosch, J. A., Terzis, D., & Laloui, L. (2024). A bio-chemo-hydro-mechanical model of transport, strength and deformation for bio-cementation applications. Acta Geotechnica, 19(5), 2805-2821.

- Koponen A., Kataja M., Timonen J. (1997). Permeability and effective porosity of porous media. Physical review E, 56(3):3319-3325.

- Li, Y., Guo, Z., Wang, L., & Yang, H. (2023). A coupled bio-chemo-hydro-wave model and multi-stages for MICP in the seabed. Ocean Engineering, 280, 114667.

- Li, Y., Wang, L., Dong, C., et al. (2025). A coupled mathematical model of microbial grouting reinforced seabed considering the response of wave-induced pore pressure and its application. Computers and Geotechnics, 184, 107235.

- Yamamoto T., Koning H., Sellmeijer H. (1978). “On the response of a poroelastic bed to water waves.” Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 78:193-206.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).