Submitted:

16 May 2025

Posted:

19 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Source of Ovarian Cancer Cell Lines and PDX Tumor Models

2.2. Soft Agar Colony Formation Assay

2.3. Generation of Lentiviruses and Cell Transduction

2.4.3. T5 Cell Proliferation Assay

2.5. WES (ProteinSimple)

2.6. Quantification of Protein Abundance Using High Resolution Accurate Mass Spectrometry (HRA-MS)

2.7. Metabolic Flux of Stable Isotope Labelled [U13C]-Glucose and [U13C]-Glutamine

2.8. Extraction of Shikonin-Bound Cellular Proteins

2.9. Mass-Spectrometry-Based Drug Discovery Study to Identify Shikonin’s Molecular Targets

2.10. Modified Pull Down Assay Coupled with WES(ProteinSimple) to Validate Shikonin Binding to LRPPRC

2.11. Animal Experiments

2.12. Dose Response Assays

2.13. Drugs and Reagents

2.14. In Silico Analysis of SDHA and LRPPRC Gene Expression in Human HGSOC Samples

2.15. Measurement of OCR and ATP Production Rate by Seahorse

2.16. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

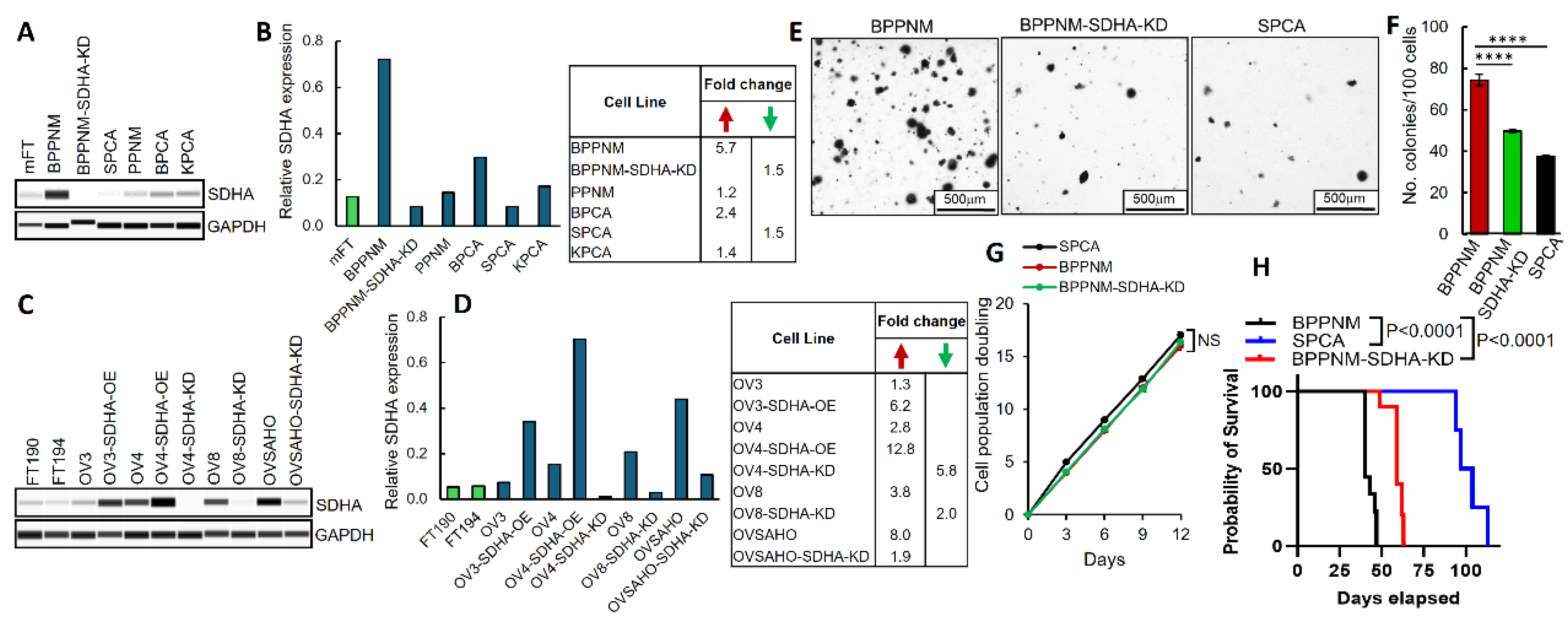

3.1. SDHA Overexpression Promotes Proliferation and Survival of Ovarian Tumor Cells in Suspension Cultures

3.2. SDHA Upregulation Promotes Orthotopic Tumor Growth in Immunocompetent Mouse Models of Ovarian Cancer

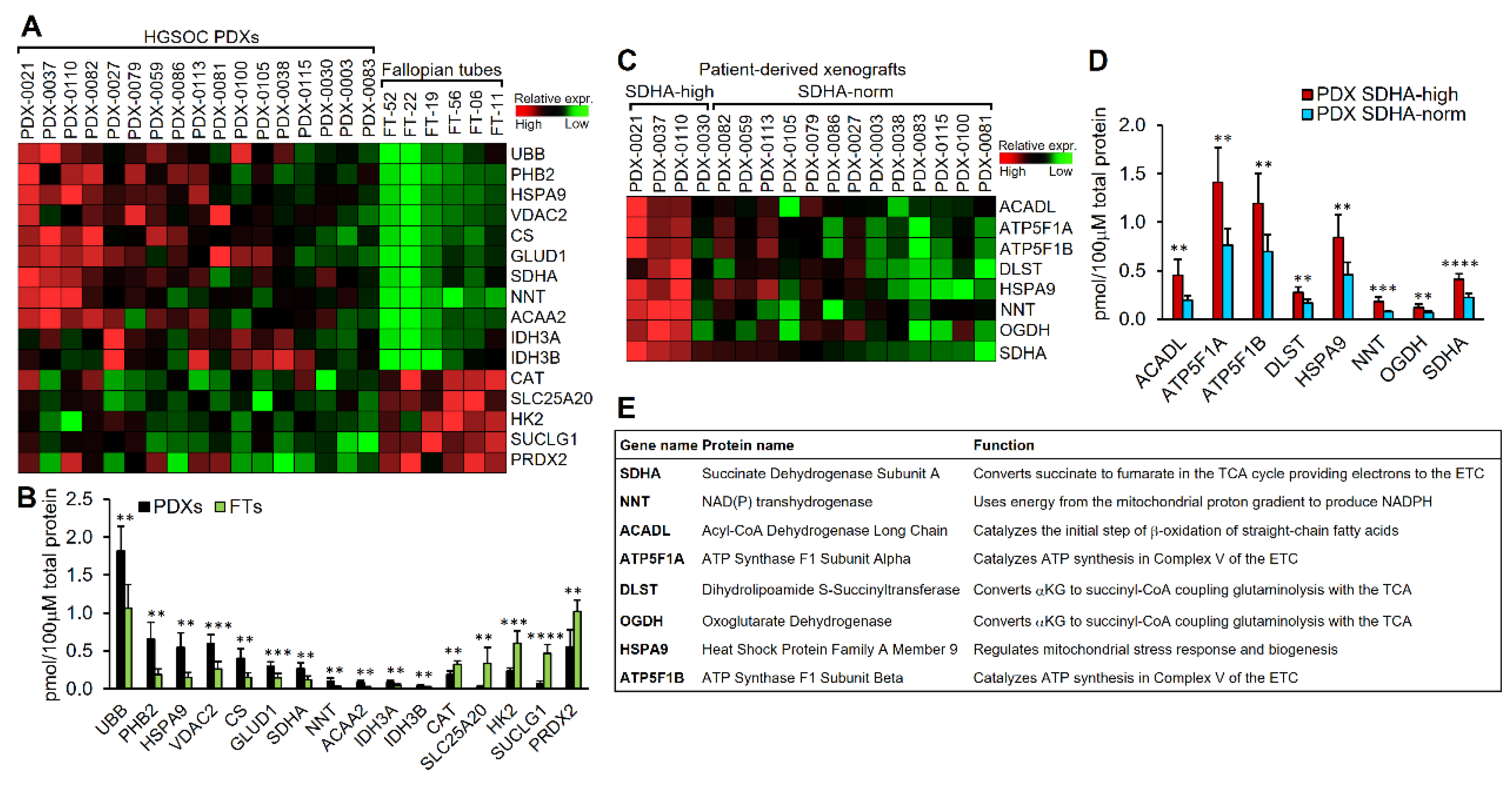

3.3. The Majority of Differentially Expressed Proteins Between Normal Human Fallopian Tubes and Ovarian PDXs, Particularly PDXs with SDHA Overexpression Are Components of the TCA Cycle

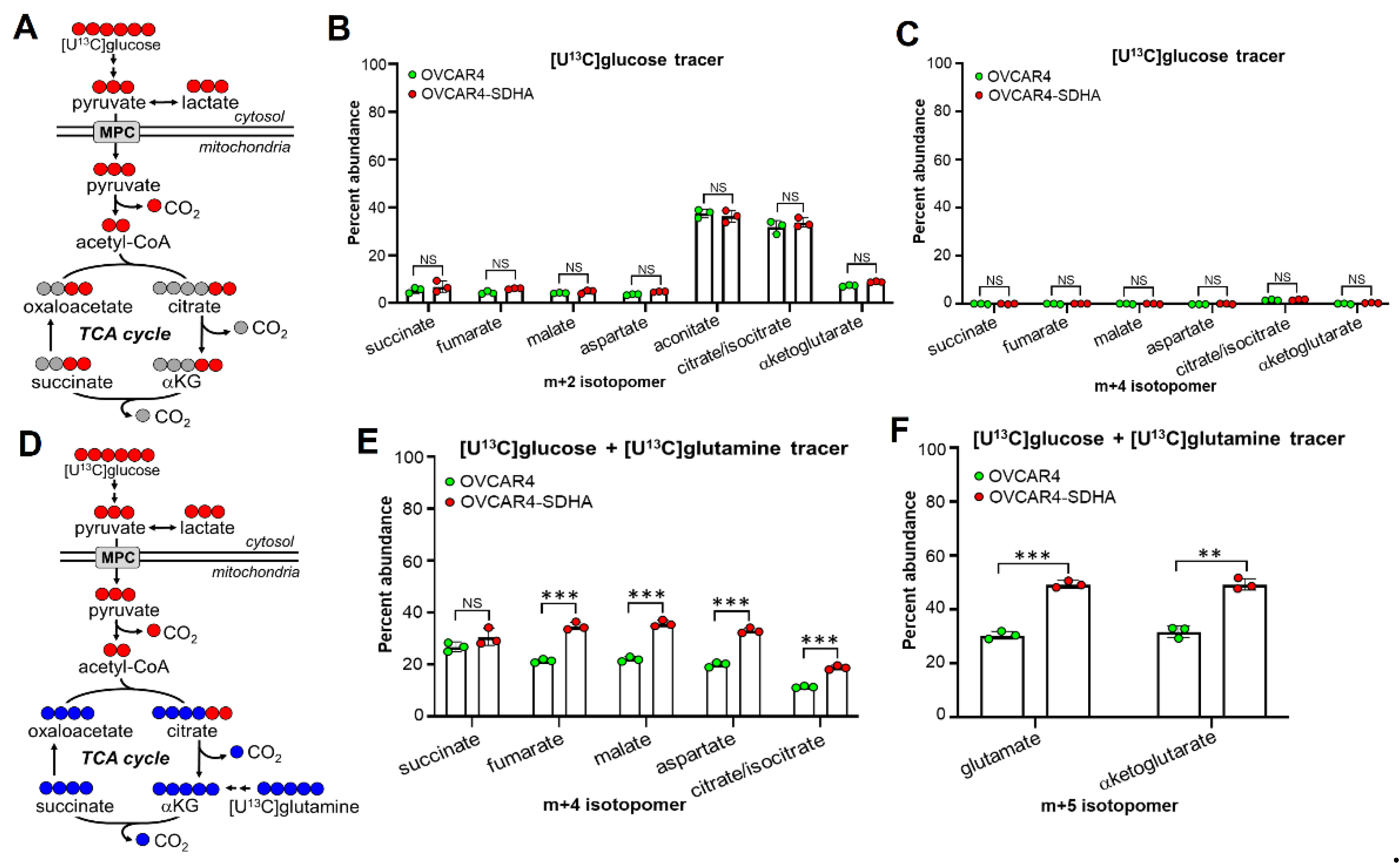

3.4. SDHA Overexpressing Ovarian Cancer Cells Rely on Glutaminolysis to Maintain an Increased TCA Cycle Flux and OXPHOS Activity

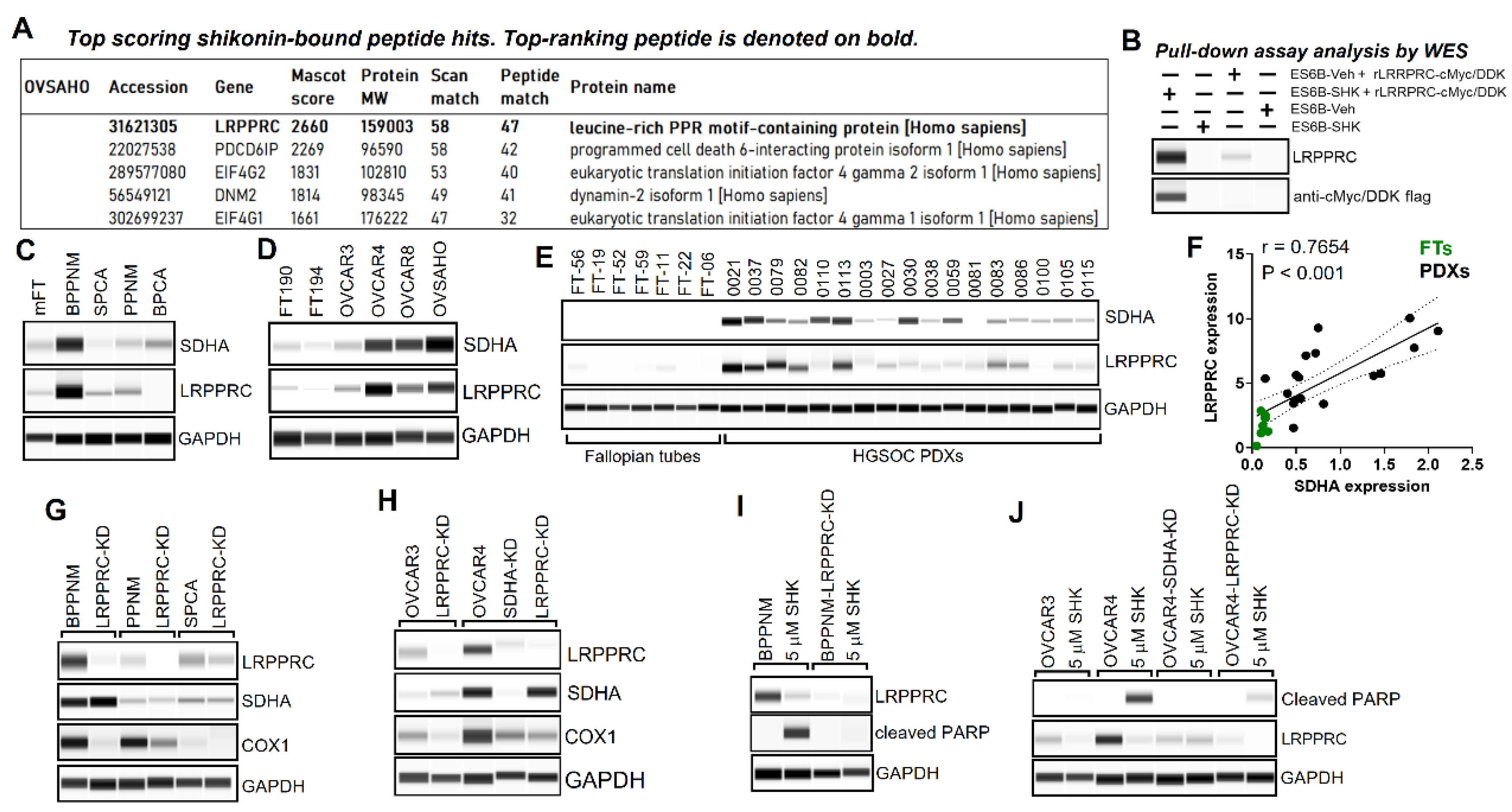

3.5. Identification of LRPPRC Protein as a Top Molecular Target of Shikonin

3.6. SDHA and LPPPRC Transcript Levels Progressively Increase from Precancerous Lesions to Invasive HGSOC, and Exhibit Concomitant Gene and Protein Expression Patterns, Particularly in Advanced Invasive Tumors

3.7. Shikonin Inhibits LRPPRC Suppressing Mitochondrial Respiration, Which Leads to Bioenergetic Disfunction and Death of Cancer Cells Overexpressing of SDHA and LRPPRC

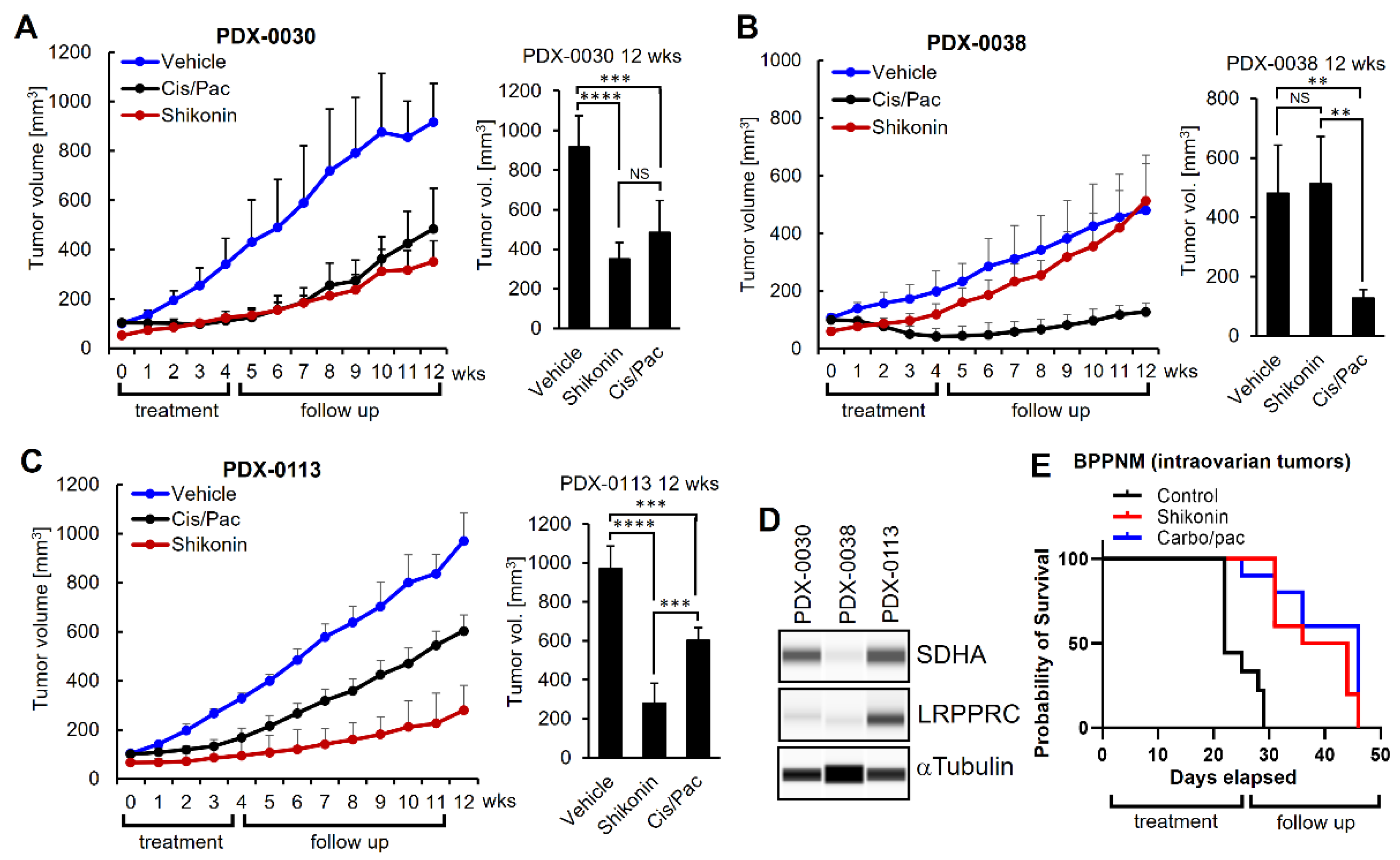

3.8. Shikonin Shows Potent Anti-Tumor Efficacy In Vivo in Ovarian Tumors with Concomitant Overexpression of SDHA and LRPPRC

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D | two-dimensional |

| 3D | three-dimensional |

| 3-PGA | 3-phosphoglyceric acid |

| aKG | aketoglutarate |

| aKGDH | aketoglutarate dehydrogenase |

| ACAA2 | acetyl-CoA acyltransferase 2 |

| ACADL | acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Long Chain |

| ANOVA | analysis of variance |

| ATCC | American type culture collection |

| ATP | adenosine triphosphate |

| BSA | bovine serum albumin |

| CAT | catalase |

| CI | complex I |

| CII | complex II |

| CIII | complex II |

| CIV | complex IV |

| CV | complex V |

| CS | citrate synthase |

| DHAP | dihydroxyacetone phosphate |

| DLST | dihydrolipoamide S-succinyltransferase |

| DOX | doxycycline |

| ECAR | extracellular acidification rate |

| ES6B | epoxy-activated Sepharose 6B |

| ETC | electron transport chain |

| F1,6BP | fructose-1,6-bisphosphate |

| F6P | fructose 6-phosphate |

| FADH2 | flavin adenine dinucleotide |

| FCCP | carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone |

| FT | fallopian tube |

| G6P | glucose-6 phosphate |

| GAPDH | glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| GLU | glucose |

| GLUD1 | glutamate dehydrogenase 1 |

| GLN | glutamine |

| hFT | human fallopian tube |

| HGSOC | high-grade serous ovarian cancer |

| HK2 | hexokinase 2 |

| H | hour |

| HPLC | high-performance liquid chromatography |

| HRA-MS | high resolution accurate mass spectrometry |

| IACUC | institutional animal care and use committee |

| IDH3A | isocitrate dehydrogenase (NAD(+)) 3 catalytic subunit alpha |

| IDH3B | isocitrate dehydrogenase (NAD(+)) 3 catalytic subunit beta |

| IRB | institutional review board |

| KD | knockdown |

| LC-MS-MS | liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry |

| LC-Q/TOF | liquid chromatography-quadropole/time-of-flight |

| LRPPRC | leucine-rich pentatricopeptide repeat-containing |

| LSFC | French-Canadian Leigh Syndrome |

| mFT | mouse fallopian tube |

| mFTE | murine fallopian tube epithelium |

| MS | mass spectrometry |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide |

| NADH | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide hydrogen |

| OCR | oxygen consumption rate |

| OGDH | oxoglutarate dehydrogenase |

| OE | overexpression |

| OMRF | Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation |

| OS | overall survival |

| OXPHOS | oxidative phosphorylation |

| PDX | patient-derived xenograft |

| PEP | phosphoenolpyruvate |

| PRDX2 | peroxiredoxin 2 |

| PPP | pentose phosphate pathway |

| RT | room temperature |

| SCNA | somatic copy number aberration |

| SD | standard deviation |

| SDH | succinate dehydrogenase |

| SDHA | succinate dehydrogenase subunit A |

| SDS-PAGE | sodium dodecyl-sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| SEM | standard error of the mean |

| shRNA | short hairpin ribonucleic acid |

| SLC25A20 | solute carrier family 25 member 20 |

| SUCLG1 | succinate-CoA ligase GDP/ADP-forming subunit alpha |

| STIC | serous tubal intraepithelial carcinomas |

| STR | short tandem repeat |

| TCA | tricarboxylic acid |

| TME | tumor microenvironment |

| USG | ultroser G serum substitute |

References

- Foley, O.W. , Rauh-Hain, J.A.; del Carmen, M.G. Recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer: an update on treatment. Oncology (Williston Park) 2013, 27, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Raja, F.A.; Chopra, N.; Ledermann, J.A. Optimal first-line treatment in ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol 2012, 23 (Suppl 10), x118–x127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazidimoradi, A.; Momenimovahed, Z.; Khani, Y.; Shahrabi, A.R.; Allahqoli, L.; Salehiniya, H. Global patterns and temporal trends in ovarian cancer morbidity, mortality, and burden from 1990 to 2019. Oncologie 2023, 25, 641–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society, A.C. Cancer Facts and Figures, 2024. 2024.

- Anderson, A.S.; Roberts, P.C.; Frisard, M.I.; Hulver, M.W.; Schmelz, E.M. Ovarian tumor-initiating cells display a flexible metabolism. Exp Cell Res 2014, 328, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caneba, C.A.; Bellance, N.; Yang, L.; Pabst, L.; Nagrath, D. Pyruvate uptake is increased in highly invasive ovarian cancer cells under anoikis conditions for anaplerosis, mitochondrial function, and migration. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2012, 303, E1036–E1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, S.; Chhina, J.; Mert, I.; Chitale, D.; Buekers, T.; Kaur, H.; Giri, S.; Munkarah, A.; Rattan, R. Bioenergetic Adaptations in Chemoresistant Ovarian Cancer Cells. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 8760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaal, E.A.; Berkers, C.R. The Influence of Metabolism on Drug Response in Cancer. Front Oncol 2018, 8, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griguer, C.E.; Oliva, C.R.; Gillespie, G.Y. Glucose metabolism heterogeneity in human and mouse malignant glioma cell lines. J Neurooncol 2005, 74, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Enriquez, S.; Carreno-Fuentes, L.; Gallardo-Perez, J.C.; Saavedra, E.; Quezada, H.; Vega, A.; Marin-Hernandez, A.; Olin-Sandoval, V.; Torres-Marquez, M.E.; Moreno-Sanchez, R. Oxidative phosphorylation is impaired by prolonged hypoxia in breast and possibly in cervix carcinoma. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2010, 42, 1744–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellance, N.; Benard, G.; Furt, F.; Begueret, H.; Smolkova, K.; Passerieux, E.; Delage, J.P.; Baste, J.M.; Moreau, P.; Rossignol, R. Bioenergetics of lung tumors: alteration of mitochondrial biogenesis and respiratory capacity. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2009, 41, 2566–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascale, R.M.; Calvisi, D.F.; Simile, M.M.; Feo, C.F.; Feo, F. The Warburg Effect 97 Years after Its Discovery. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentric, G.; Kieffer, Y.; Mieulet, V.; Goundiam, O.; Bonneau, C.; Nemati, F.; Hurbain, I.; Raposo, G.; Popova, T. , Stern, M.H.; et al. PML-Regulated Mitochondrial Metabolism Enhances Chemosensitivity in Human Ovarian Cancers. Cell Metab 2019, 29, 156–173 e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc, Z.C.; Sollars, V.E.; Bou Zgheib, N.; Rankin, G.O.; Koc, E.C. Evaluation of mitochondrial biogenesis and ROS generation in high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Front Oncol 2023, 13, 1129352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasto, A.; Bellio, C.; Pilotto, G.; Ciminale, V.; Silic-Benussi, M.; Guzzo, G.; Rasola, A.; Frasson, C.; Nardo, G.; Zulato, E.; et al. Cancer stem cells from epithelial ovarian cancer patients privilege oxidative phosphorylation, and resist glucose deprivation. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 4305–4319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Moss, T.; Mangala, L.S.; Marini, J.; Zhao, H.; Wahlig, S.; Armaiz-Pena, G.; Jiang, D.; Achreja, A.; Win, J.; et al. Metabolic shifts toward glutamine regulate tumor growth, invasion and bioenergetics in ovarian cancer. Mol Syst Biol 2014, 10, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Cybula, M.; Rostworowska, M.; Wang, L.; Mucha, P.; Bulicz, M.; Bieniasz, M. Upregulation of Succinate Dehydrogenase (SDHA) Contributes to Enhanced Bioenergetics of Ovarian Cancer Cells and Higher Sensitivity to Anti-Metabolic Agent Shikonin. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Huo, X.; Zhai, Y.; Wang, A.; Xu, J.; Su, D.; Bartlam, M.; Rao, Z. Crystal structure of mitochondrial respiratory membrane protein complex II. Cell 2005, 121, 1043–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ni, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Y. Integrated proteomics and metabolomics reveals the comprehensive characterization of antitumor mechanism underlying Shikonin on colon cancer patient-derived xenograft model. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 14092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, L.N.; Kong, L.Q.; Xu, H.H.; Chen, Q.H.; Dong, Y.; Li, B.; Zeng, X.H.; Wang, H.M. Research Progress on Structure and Anti-Gynecological Malignant Tumor of Shikonin. Front Chem 2022, 10, 935894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Wang, L.; Ren, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H. LRPPRC: A Multifunctional Protein Involved in Energy Metabolism and Human Disease. Front Physiol 2019, 10, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterky, F.H.; Ruzzenente, B.; Gustafsson, C.M.; Samuelsson, T.; Larsson, N.G. LRPPRC is a mitochondrial matrix protein that is conserved in metazoans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010, 398, 759–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perets, R.; Wyant, G.A.; Muto, K.W.; Bijron, J.G.; Poole, B.B.; Chin, K.T.; Chen, J.Y.; Ohman, A.W.; Stepule, C.D.; Kwak, S.; et al. Transformation of the fallopian tube secretory epithelium leads to high-grade serous ovarian cancer in Brca;Tp53;Pten models. Cancer Cell 2013, 24, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, S.; Zhang, S.; Yucel, S.; Horn, H.; Smith, S.G.; Reinhardt, F.; Hoefsmit, E.; Assatova, B.; Casado, J.; Meinsohn, M.C.; et al. Genetically Defined Syngeneic Mouse Models of Ovarian Cancer as Tools for the Discovery of Combination Immunotherapy. Cancer Discov 2021, 11, 384–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cybula, M.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Drumond-Bock, A.L.; Moxley, K.M.; Benbrook, D.M.; Gunderson-Jackson, C.; Ruiz-Echevarria, M.J.; Bhattacharya, R.; Mukherjee, P.; et al. Patient-Derived Xenografts of High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer Subtype as a Powerful Tool in Pre-Clinical Research. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieniasz, M.; Radhakrishnan, P.; Faham, N.; De La, O.J.; Welm, A.L. Preclinical Efficacy of Ron Kinase Inhibitors Alone and in Combination with PI3K Inhibitors for Treatment of sfRon-Expressing Breast Cancer Patient-Derived Xenografts. Clin Cancer Res 2015, 21, 5588–5600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLean, B.; Tomazela, D.M.; Shulman, N.; Chambers, M.; Finney, G.L.; Frewen, B.; Kern, R.; Tabb, D.L.; Liebler, D.C.; MacCoss, M.J. Skyline: an open source document editor for creating and analyzing targeted proteomics experiments. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 966–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kader, T.; Lin, J.R.; Hug, C.; Coy, S.; Chen, Y.A.; de Bruijn, I.; Shih, N.; Jung, E.; Pelletier, R.J.; Leon, M.L.; et al. Multimodal Spatial Profiling Reveals Immune Suppression and Microenvironment Remodeling in Fallopian Tube Precursors to High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, F.; Xu, F.; Yang, T. Mass Spectrometry-Based Protein Quantification. Adv Exp Med Biol 2016, 919, 255–279. [Google Scholar]

- Eniafe, J.; Jiang, S. The functional roles of TCA cycle metabolites in cancer. Oncogene 2021, 40, 3351–3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.; Singh, K.K. The mitochondrial landscape of ovarian cancer: emerging insights. Carcinogenesis 2021, 42, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koundouros, N.; Poulogiannis, G. Reprogramming of fatty acid metabolism in cancer. Br J Cancer 2020, 122, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, N.; Yang, M.; Gaur, U.; Xu, H.; Yao, Y.; Li, D. Alpha-Ketoglutarate: Physiological Functions and Applications. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 2016, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yohannes, E.; Kazanjian, A.A.; Lindsay, M.E.; Fujii, D.T.; Ieronimakis, N.; Chow, G.E.; Beesley, R.D.; Heitmann, R.J.; Burney, R.O. The human tubal lavage proteome reveals biological processes that may govern the pathology of hydrosalpinx. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 8980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewis, I.A.; Winston, R.M.; Leese, H.J. Energy metabolism of the human fallopian tube. J Reprod Fertil 1992, 95, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Console, L.; Scalise, M.; Mazza, T.; Pochini, L.; Galluccio, M.; Giangregorio, N.; Tonazzi, A.; Indiveri, C. Carnitine Traffic in Cells. Link With Cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020, 8, 583850. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, P.; Mu, J.; Wang, Z.; Ma, S.; Da, X.; Song, J.; Zhang, H.; Yang, L.; Li, J.; Yang, J. Down-regulation of SLC25A20 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma growth and metastasis through suppression of fatty-acid oxidation. Cell Death Dis 2021, 12, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, E.; Diehl, S. Analysis and interpretation of transcriptomic data obtained from extended Warburg effect genes in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Oncoscience 2015, 2, 151–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaberi, E.; Chitsazian, F.; Ali Shahidi, G.; Rohani, M.; Sina, F.; Safari, I.; Malakouti Nejad, M.; Houshmand, M.; Klotzle, B.; Elahi, E. The novel mutation p.Asp251Asn in the beta-subunit of succinate-CoA ligase causes encephalomyopathy and elevated succinylcarnitine. J Hum Genet 2013, 58, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tretter, L.; Adam-Vizi, V. Alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase: a target and generator of oxidative stress. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2005, 360, 2335–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatrinet, R.; Leone, G.; De Luise, M.; Girolimetti, G.; Vidone, M.; Gasparre, G.; Porcelli, A.M. The alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex in cancer metabolic plasticity. Cancer Metab 2017, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mates, J.M.; Di Paola, F.J.; Campos-Sandoval, J.A.; Mazurek, S.; Marquez, J. Therapeutic targeting of glutaminolysis as an essential strategy to combat cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2020, 98, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Xie, J.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X. Shikonin and its analogs inhibit cancer cell glycolysis by targeting tumor pyruvate kinase-M2. Oncogene 2011, 30, 4297–4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolland, S.G.; Motori, E.; Memar, N.; Hench, J.; Frank, S.; Winklhofer, K.F.; Conradt, B. Impaired complex IV activity in response to loss of LRPPRC function can be compensated by mitochondrial hyperfusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, E2967–E2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldera, A.P.; Govender, D. Gene of the month: SDH. J Clin Pathol 2018, 71, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazar, E.; Khatami, F.; Saffar, H.; Tavangar, S.M. The Emerging Role of Succinate Dehyrogenase Genes (SDHx) in Tumorigenesis. Int J Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Res 2019, 13, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnichon, N.; Briere, J.J.; Libe, R.; Vescovo, L.; Riviere, J.; Tissier, F.; Jouanno, E.; Jeunemaitre, X.; Benit, P.; Tzagoloff, A.; et al. SDHA is a tumor suppressor gene causing paraganglioma. Hum Mol Genet 2010, 19, 3011–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoekstra, A.S.; de Graaff, M.A.; Briaire-de Bruijn, I.H.; Ras, C.; Seifar, R.M.; van Minderhout, I.; Cornelisse, C.J.; Hogendoorn, P.C.; Breuning, M.H.; Suijker, J.; et al. Inactivation of SDH and FH cause loss of 5hmC and increased H3K9me3 in paraganglioma/pheochromocytoma and smooth muscle tumors. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 38777–38788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courage, C.; Jackson, C.B.; Hahn, D.; Euro, L.; Nuoffer, J.M.; Gallati, S.; Schaller, A. SDHA mutation with dominant transmission results in complex II deficiency with ocular, cardiac, and neurologic involvement. Am J Med Genet A 2017, 173, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, C.; Oba, J.; Roszik, J.; Marszalek, J.R.; Chen, K.; Qi, Y.; Eterovic, K.; Robertson, A.G.; Burks, J.K.; McCannel, T.A.; et al. Elevated Endogenous SDHA Drives Pathological Metabolism in Highly Metastatic Uveal Melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2019, 60, 4187–4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, L.; Fang, Y.; Jin, L.; Zhang, X.; Luis, M.A.; Lin, X.; Tang, S.; Cai, F. Unveiling the hidden role of SDHA in breast cancer proliferation: a novel therapeutic avenue. Cancer Cell Int 2025, 25, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapalczynska, M.; Kolenda, T.; Przybyla, W.; Zajaczkowska, M.; Teresiak, A.; Filas, V.; Ibbs, M.; Blizniak, R.; Luczewski, L.; Lamperska, K. 2D and 3D cell cultures - a comparison of different types of cancer cell cultures. Arch Med Sci 2018, 14, 910–919. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhou,Y. Understanding the cancer/tumor biology from 2D to 3D. J Thorac Dis 2016, 8, E1484–E1486.

- Cortesi, M.; Warton, K.; Ford, C.E. Beyond 2D cell cultures: how 3D models are changing the in vitro study of ovarian cancer and how to make the most of them. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewski, K.; Barsotti, A.; Feng, X.J.; Momcilovic, M.; Liu, K.G.; Kim, J.I.; Morris, K.; Lamarque, C.; Gaffney, J.; Yu, X.; et al. Inhibition of glucose transport synergizes with chemical or genetic disruption of mitochondrial metabolism and suppresses TCA cycle-deficient tumors. Cell Chem Biol 2022, 29, 423–435 e410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, M.; Bague, S.; Valero, C.; Holgado, A.; Lopez-Vilaro, L.; Terra, X.; Aviles-Jurado, F.X.; Leon, X. Transcriptional Expression of SLC2A3 and SDHA Predicts the Risk of Local Tumor Recurrence in Patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas Treated Primarily with Radiotherapy or Chemoradiotherapy. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, K.M.; Lu, M.; Yang, P.; Wu, S.; Cai, C.; Zhong, W.D.; Olumi, A.; Young, R.H.; Wu, C.L. Succinate dehydrogenase B: a new prognostic biomarker in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol 2015, 46, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Pan, S.; Chen, C.; Cao, L.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Su, X.; Lin, S. Down-regulation of succinate dehydrogenase subunit B and up-regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 predicts poor prognosis in recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Tumour Biol 2016, 37, 5145–5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Liang, N.; Long, X.; Zhao, J.; Yang, J.; Du, X.; Yang, T.; Yuan, P.; Huang, X.; Zhang, J.; et al. SDHC-related deficiency of SDH complex activity promotes growth and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma via ROS/NFkappaB signaling. Cancer Lett 2019, 461, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udumula, M.P.; Rashid, F.; Singh, H.; Pardee, T.; Luther, S.; Bhardwaj, T.; Anjaly, K.; Piloni, S.; Hijaz, M.; Gogoi, R.; et al. Targeting mitochondrial metabolism with CPI-613 in chemoresistant ovarian tumors. J Ovarian Res 2024, 17, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Moss, T.; Mangala, L.S.; Marini, J.; Zhao, H.; Wahlig, S.; Armaiz-Pena, G.; Jiang, D.; Achreja, A.; Win, J.; et al. Metabolic shifts toward glutamine regulate tumor growth, invasion and bioenergetics in ovarian cancer. Mol Syst Biol 2014, 10, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, A.R.; Wheaton, W.W.; Jin, E.S.; Chen, P.H.; Sullivan, L.B.; Cheng, T.; Yang, Y.; Linehan, W.M.; Chandel, N.S.; DeBerardinis, R.J. Reductive carboxylation supports growth in tumour cells with defective mitochondria. Nature 2011, 481, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metallo, C.M.; Gameiro, P.A.; Bell, E.L.; Mattaini, K.R.; Yang, J.; Hiller, K.; Jewell, C.M.; Johnson, Z.R.; Irvine, D.J.; Guarente, L.; et al. Reductive glutamine metabolism by IDH1 mediates lipogenesis under hypoxia. Nature 2011, 481, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.; Cardenas, H.; Matei, D. Ovarian Cancer-Why Lipids Matter. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieman, K.M.; Kenny, H.A.; Penicka, C.V.; Ladanyi, A.; Buell-Gutbrod, R.; Zillhardt, M.R.; Romero, I.L.; Carey, M.S.; Mills, G.B.; Hotamisligil, G.S.; et al. Adipocytes promote ovarian cancer metastasis and provide energy for rapid tumor growth. Nat Med 2011, 17, 1498–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chujo, T.; Ohira, T.; Sakaguchi, Y.; Goshima, N.; Nomura, N.; Nagao, A.; Suzuki, T. LRPPRC/SLIRP suppresses PNPase-mediated mRNA decay and promotes polyadenylation in human mitochondria. Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 40, 8033–8047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lv, L.; Zheng, J.; Zhou, J.; Liu, B.; Chen, H.; Liang, C.; Wang, R.; Su, L.; Li, X.; et al. The significance of LRPPRC overexpression in gastric cancer. Med Oncol 2014, 31, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Li, X.; Huang, H.; Jiang, F.; Lin, Z.; He, H.; Chen, Y.; Yue, F.; Zou, J.; He, Y.; et al. Elevated levels of mitochondrion-associated autophagy inhibitor LRPPRC are associated with poor prognosis in patients with prostate cancer. Cancer 2014, 120, 1228–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, T.; Kurabe, N.; Goto-Inoue, N.; Nakamura, T.; Sugimura, H.; Setou, M.; Maekawa, M. Immunohistochemical expression analysis of leucine-rich PPR-motif-containing protein (LRPPRC), a candidate colorectal cancer biomarker identified by shotgun proteomics using iTRAQ. Clin Chim Acta 2017, 471, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, B.; Liang, Y.; Tang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, L.; Yin, J. Prognostic significance of LRPPRC and its association with immune infiltration in liver hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Clin Exp Immunol 2024, 13, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, X.; Xie, F.; Ma, C.; Lam, E.W.; Kang, N.; Jin, D.; Yan, J.; Jin, B. Comprehensive pan-cancer analysis identifies the RNA-binding protein LRPPRC as a novel prognostic and immune biomarker. Life Sci 2024, 343, 122527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Janson, V.; Liu, H. Comprehensive review on leucine-rich pentatricopeptide repeat-containing protein (LRPPRC, PPR protein): A burgeoning target for cancer therapy. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 282 Pt 3, 136820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research N: Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature 2011, 474, 609–615. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xu, Z.; Jiang, J.; Xu, T.; Xu, J.; Liu, P. High Expression of Succinate Dehydrogenase Subunit A Which Is Regulated by Histone Acetylation, Acts as a Good Prognostic Factor of Multiple Myeloma Patients. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 563666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Q.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Wang, D.; Zhang, T.; Shen, T.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Shao, X.; Zhou, W.; et al. LRPPRC confers enhanced oxidative phosphorylation metabolism in triple-negative breast cancer and represents a therapeutic target. J Transl Med 2025, 23, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuillerier, A.; Honarmand, S.; Cadete, V.J.J.; Ruiz, M.; Forest, A.; Deschenes, S.; Beauchamp, C.; Consortium, L.; Charron, G.; Rioux, J.D.; et al. Loss of hepatic LRPPRC alters mitochondrial bioenergetics, regulation of permeability transition and trans-membrane ROS diffusion. Hum Mol Genet 2017, 26, 3186–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olahova, M.; Hardy, S.A.; Hall, J.; Yarham, J.W.; Haack, T.B.; Wilson, W.C.; Alston, C.L.; He, L.; Aznauryan, E.; Brown, R.M.; et al. LRPPRC mutations cause early-onset multisystem mitochondrial disease outside of the French-Canadian population. Brain 2015, 138 Pt 12, 3503–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Chen, L.L.; Xiong, Y.; Ye, D. Metabolite regulation of epigenetics in cancer. Cell Rep 2024, 43, 114815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuillerier, A.; Ruiz, M.; Daneault, C.; Forest, A.; Rossi, J.; Vasam, G.; Cairns, G.; Cadete, V.; Consortium, L.; Des Rosiers, C.; et al. Adaptive optimization of the OXPHOS assembly line partially compensates lrpprc-dependent mitochondrial translation defects in mice. Commun Biol 2021, 4, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).