1. Introduction and Related Work

Humanoid robots have seen remarkable advancements in recent years, due to improvements in both design and control. They are increasingly being considered for practical applications in settings where human-like mobility is essential. Unlike wheeled robots, which are mostly limited to flat and structured environments, humanoids are designed to traverse complex human-centric environments, including stairs and ramps.

Despite recent successes demonstrating formidable agility, we have seen less impressive results in the field of autonomous navigation of complex environments. Indeed, in such environments it is necessary to couple long-term planning with effective control.

Moving in complex and cluttered environments demands the ability to plan over a long horizon, ensuring that the robot can reach a distant goal without getting stuck. To make the problem more approachable, the possible paths the robot can take are often reduced to those that can be constructed as concatenations of

primitives, i.e., the displacement between two consecutive footsteps is selected from a catalogue [

1]. The problem then becomes that of searching within this large discrete space. Approaches based on grid or graph search (e.g., A*) proved effective in relatively simple contexts, thanks to clear heuristics and systematic exploration [

2,

3,

4]. However, they may suffer from combinatorial explosion due to the need of exploring a large number of branches.

The representation of the environment is a crucial aspect, not only for efficiency reasons, but also because it can allow or disallow features of the algorithm. A commonly used representation is the

elevation map, which associates each point in the

-plane with a corresponding elevation value. Although elevation maps are easy to reconstruct from data, they have limitations, e.g., they do not allow representing multi-floor environments. In [

5,

6], the authors showed efficient ways to represent the environment as a set of planar regions, and tested on-line footstep planning using an A* algorithm.

A significant boost in the search efficiency can be obtained using sample-based methods, such as those based on Rapidly-exploring Random Trees (RRT) [

7]. These methods can address some of the limitations of search techniques because the expansion mechanism is biased towards exploration. RRT in its basic formulation however does not account in any way for the quality of the produced plan, and can lead to inefficient motions. Furthermore, the use of a primitive catalogue will result in a certain

granularity of the final plan, as the number of possible choices is limited by the number of primitives available.

On the control side, many techniques have been proposed. While approaches based on reinforcement learning and imitation learning have proven to produce very agile motions, these are usually not designed to move in crowded environments because high-level commands are given as reference velocities, rather than a precise sequence of footstep positions. Conversely, approaches based on Model Predictive Control (MPC) can more effectively follow an input reference footstep plan. Classic methods use a Linear Inverted Pendulum (LIP) as a simplified dynamic model [

8], which is unsuited to motion in complex environments due to the constant height Center of Mass (CoM) requirement. However, later studies have shown [

9,

10] that other similar simplified models can be used to generate variable-height CoM trajectories.

The problem becomes more complex when the surfaces on which it is possible to step have an arbitrary orientation, since the possibility of slipping of the contact feet is now significant. Therefore, it is necessary to generate interaction forces that offer sufficient friction. One possibility is to produce a sufficiently robust controller that can walk blindly and adapt to unknown slope changes [

11,

12]. While this has its advantages, there are cases in which the terrain information is known, and its use will undoubtedly produce better performance. [

13] focused on the problem of moving across surfaces with known different orientation, but the footstep plan was given a priori.

We previously proposed an MPC-based humanoid gait generation methodology including an explicit stability constraint [

14]. While the original approach used the LIP as a template model, we have showed that it can be extended in order to generate vertical motions [

15], and even running [

16]. In [

17], we integrated our MPC controller with a footstep planner to realize motion in complex environments constituted by horizontal ground patches at different heights (a

world of stairs). The exploration was performed by randomly expanding a tree of possible footstep sequences with the goal of reaching a given goal region. The planner was given a time budget, after which it would return the best found plan according to a specified optimality criterion using an RRT*-like strategy [

18].

In this paper, we propose a comprehensive framework for footstep planning and control that addresses the unique demands posed by complex environments, including the presence of stairs, inclined planes, and multiple floors. The footstep planner is based on an off-line randomized exploration which finds the best footstep plan in a given time budget. Its goal is to find the sequence that reaches a given goal position in the minimum number of steps. The control pipeline is constituted by a Model Predictive Controller (MPC) and a Whole-Body Controller (WBC) generating torque control commands for the humanoid.

In particular our unified framework is capable of:

planning a collision-free sequence of footsteps in a world of ramps, i.e., an environment constituted by planar regions with different inclination, without using motion primitives;

optimizing said footstep plan according to a quality metric and returning the best solution found within the afforded time budget;

providing, along with the footstep sequence, also variable height collision-free trajectories for the swing foot in order to overcome small obstacles on the ground or climb at a different height;

generating a stable 3D CoM trajectory that allows the robot to move along the planned footstep sequence;

computing torque commands for the humanoid robot in such a way that contact forces provide sufficient friction to avoid slipping.

We validated the footstep planner with an extensive testing campaign in which we evaluated its performance in several different simulated environments, and compared results using different time budgets. Furthermore, we tested the full framework, including the control modules, in dynamic simulations in MuJoCo.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. In the next section, we formulate the motion generation problem while in

Section 3 we give an overview of the proposed approach. A full description of the introduced footstep planner is given in

Section 4 while the control architecture is presented in

Section 5. We extensively test the proposed approach on increasingly complex environments through dynamic simulations in MuJoCo in

Section 6.

Section 7 concludes the article.

2. Problem Formulation

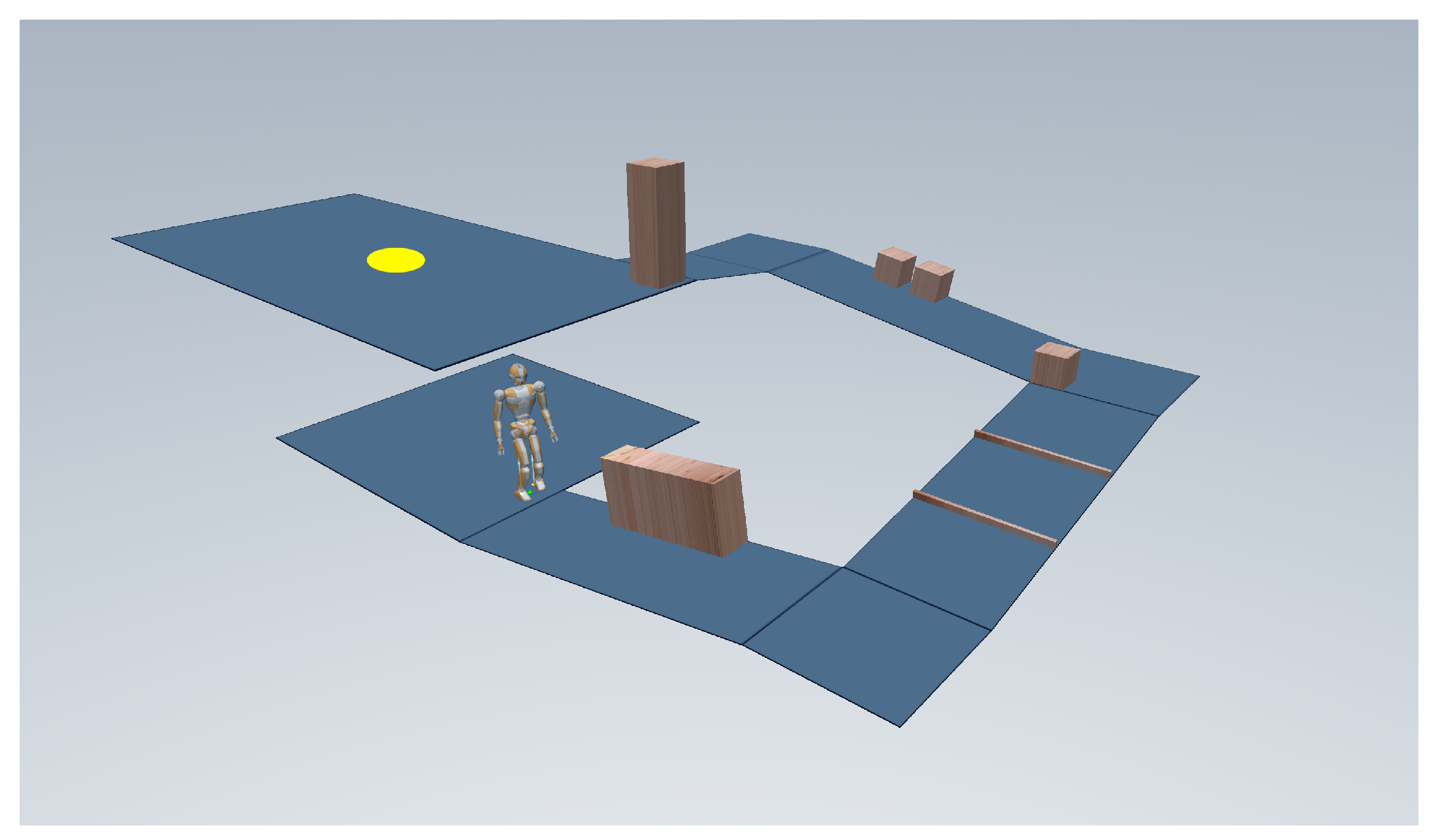

In the situation of interest (

Figure 1), a humanoid robot moves in a

world of ramps, a specific 3D environment consisting of planar regions that are arbitrarily placed and oriented in space. This characterization encompasses office-like scenarios, with rooms connected by staircases or ramps, possibly arranged on several floors and populated by obstacles. Depending on its elevation and/or inclination, a planar region may be accessible for the humanoid to step on, or not.

The mission of the robot is to reach a certain goal area , assumed to be contained in a single planar region. The locomotion task is accomplished as soon as the robot places a footstep inside .

We want to devise a complete framework enabling the humanoid to plan and execute a motion to fulfill the assigned task in the world of ramps. This requires addressing two fundamental problems: finding a 3D footstep plan and generating a variable-height gait consistent with such plan. Footstep planning consists in finding both footstep placements and swing foot trajectories; overall, the footstep plan must be feasible (in a sense to be formally defined later) for the humanoid, given the characteristics of the environment. Gait generation consists in finding a Center of Mass (CoM) trajectory which realizes the footstep plan while guaranteeing dynamic balance of the robot at all time instants. Starting from the trajectories of the CoM and the feet, a whole-body controller will generate torque commands for the robot joints that complying with the robot kinematic and dynamic limitations.

The problem will be solved under the following assumptions.

- A1

Information about the environment geometry is completely known a priori and collected in a

map expressed as

where

is an arbitrarily oriented planar region in 3D space (a

ramp).

- A2

The humanoid is endowed with a localization module which, using the available sensor data, provides an estimate of the robot current state in terms of its CoM and swing foot pose.

In view of assumption A1, a complete footstep plan leading to the goal area

can be computed off-line, before the humanoid starts to execute the motion. While we will maintain this viewpoint in the present paper, an extension to the on-line case can be devised along the same lines of [

17], i.e., by updating the footstep plan on the basis of new information gathered and added to

during the motion, e.g., using visual information [

5,

6,

17].

3. Proposed Approach

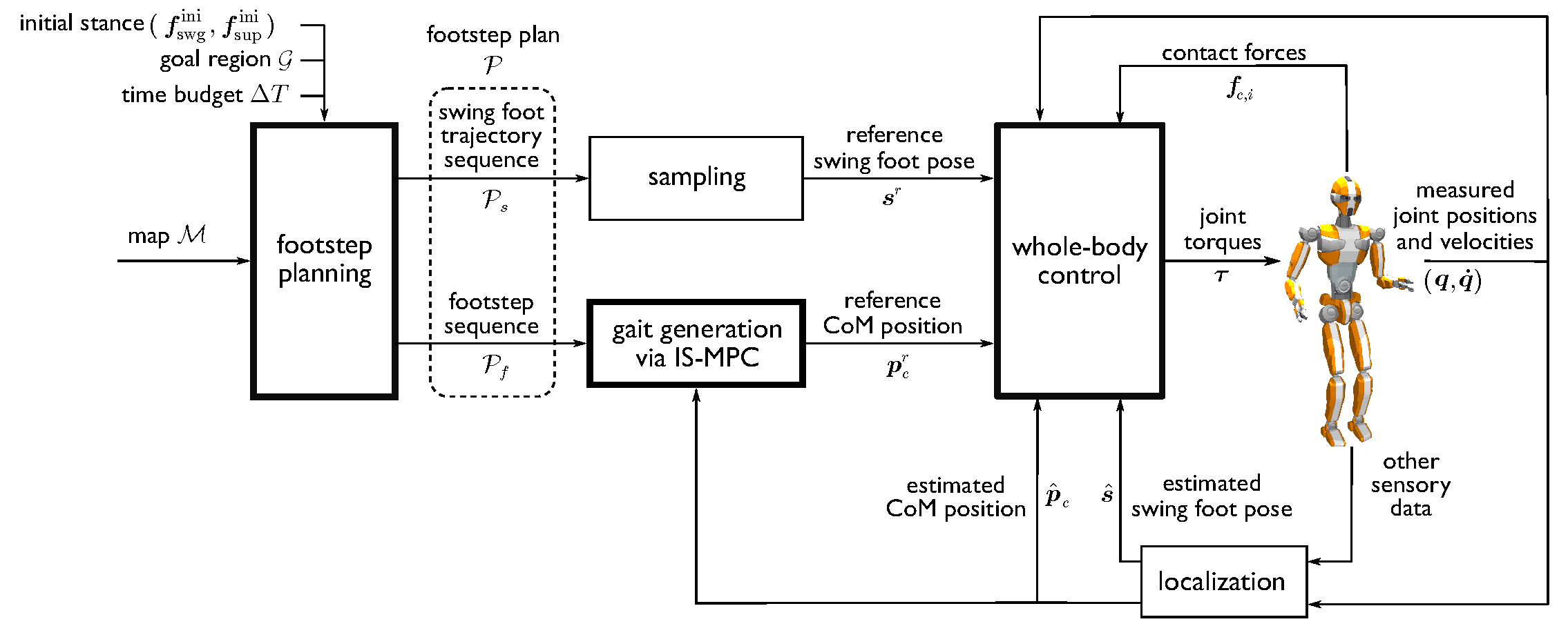

To solve the described problem, we adopt the architecture shown in

Figure 2, in which the main components are the footstep planning, gait generation and whole-body control modules.

In the following, we denote by the pose of a footstep, with , , representing the coordinates of a representative point, henceforth collectively denoted as , and its orientation, expressed via roll-pitch-yaw angles, collectively denoted by . Moreover, a pair defines a stance, i.e., the feet poses during a double support phase after which a step is performed by moving the swing foot from while keeping the support foot at .

The footstep planner receives in input the initial humanoid stance , the goal area , a time budget , and the map of the environment.

The time budget represents the time given to the planner to find a solution. When this time runs over, the algorithm either returns a solution or ends with a failure. Explicitly specifying this time as input to the algorithm allows us to evaluate the performance of the planning module, but also paves the way for the extension to the on-line case, where the time budget would be set equal to the duration of a step in order to meet the real-time requirement.

The planner works off-line to find, within

, an optimal

footstep plan leading to the desired goal area

. In

, we denote by

the sequence of footstep placements, whose generic element

is the pose of the

j-th footstep, with

and

. Also, we denote by

the sequence of associated swing foot trajectories, whose generic element

is the

j-th

step, i.e., the trajectory leading the foot from

to

over a fixed duration

.

Once the footstep plan has been generated, the sequence of footsteps

is sent to a gait generator based on Intrinsically Stable MPC (IS-MPC), which computes in real time a variable-height CoM trajectory that is compatible with

and guaranteed to be

stable, i.e., bounded with respect to a specific point called

Zero Moment Point (ZMP, more on this in

Section 5.1). In particular, we denote by

the current reference position of the CoM produced by IS-MPC. Also, let

be the current reference pose of the swing foot, obtained by sampling the appropriate subtrajectory in

.

Finally, the reference trajectories and are passed to a whole-body controller which computes the joint torque commands for the robot so as to track these trajectories while ensuring that the generated contact forces are feasible.

Sensor information, including joint encoder data, is used by the localization module to continuously update the estimate of the CoM position and swing foot pose ( and , respectively) through kinematic computations. Finally, these estimates are used to provide feedback to both the gait generation and whole-body control modules.

4. Footstep Planner

The input data for this module are the initial robot stance , the goal region , the time budget and the elevation map . Given an optimality criterion, the footstep planner returns the best footstep plan leading to found within .

The planning algorithm builds a tree , where each vertex specifies a stance, and an edge between two vertexes v and indicates a step between the two stances, i.e., a collision-free trajectory such that one foot swings from to and the other is fixed at .

Each branch joining the root of the tree to a generic vertex v represents a footstep plan . The sequences and for this plan are respectively obtained by taking along the branch the support foot poses of all vertexes and the steps corresponding to all edges.

4.1. Footstep Feasibility

Footstep is feasible if it satisfies the following requirements:

- R1

-

is fully contained in a single horizontal region.

In practice, one typically uses an enlarged footprint to ensure that this requirement will still be satisfied in the presence of small positioning errors.

- R2

-

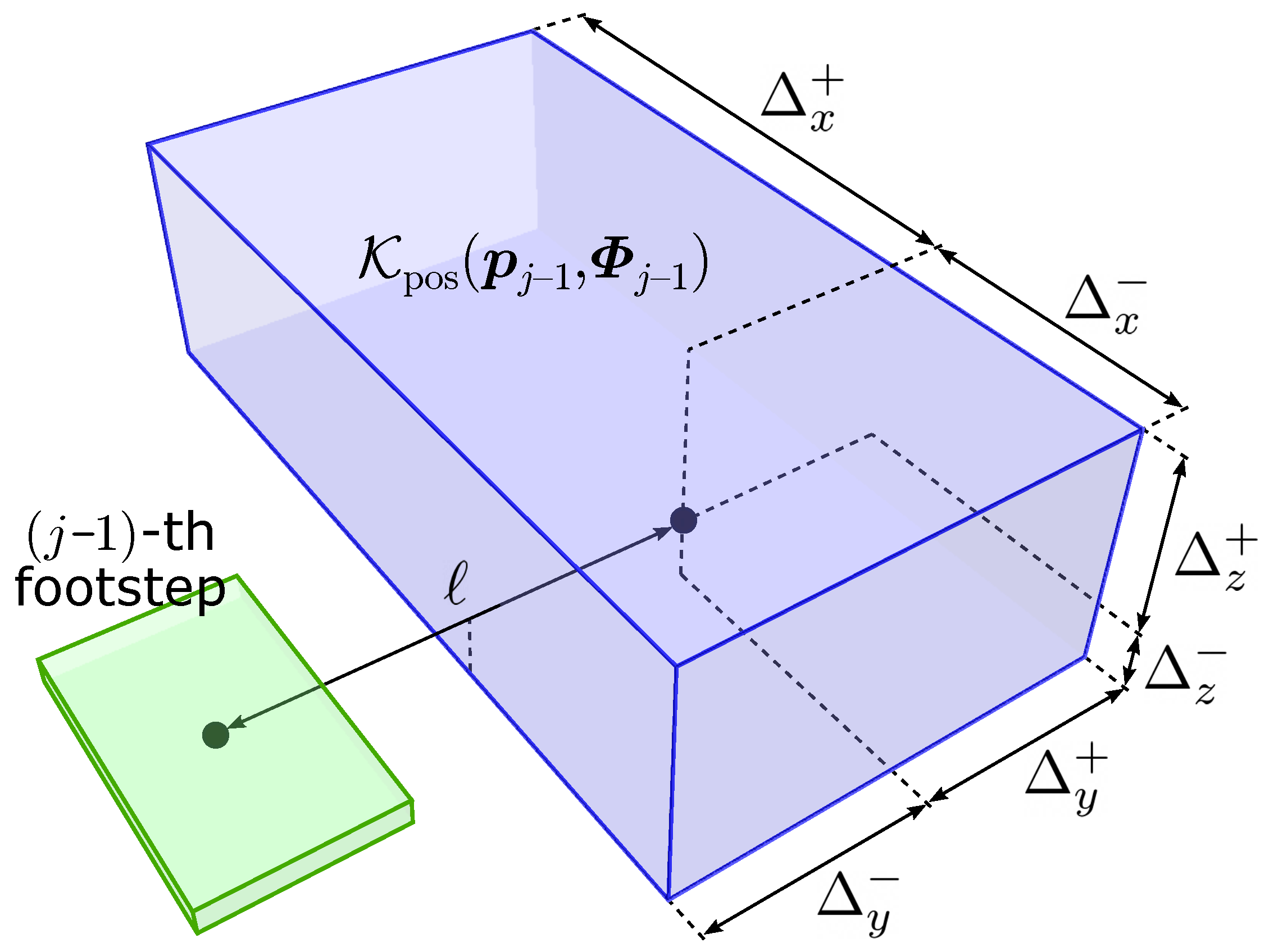

is kinematically admissible from the previous footstep .

Given

, the

kinematically admissible region for

is the submanifold of

defined as

Here,

is the set of kinematically admissible positions of the

j-th footstep, defined by the following constraints:

where

is the rotation matrix associated with

and the

symbols denote lower and upper maximum increments, see

Figure 3.

The set

of kinematically admissible orientations of the

j-th footstep is defined by the following constraints:

Note that the constraints on the roll and pitch angles and are bounds on their value, whereas the constraint on the yaw angle only limits its variation with respect to the previous footstep. This is because yaw can assume any value, whereas pitch and roll are subject to kinematic limitations that are impossible to evaluate at the planning stage, and must then be accounted for conservatively.

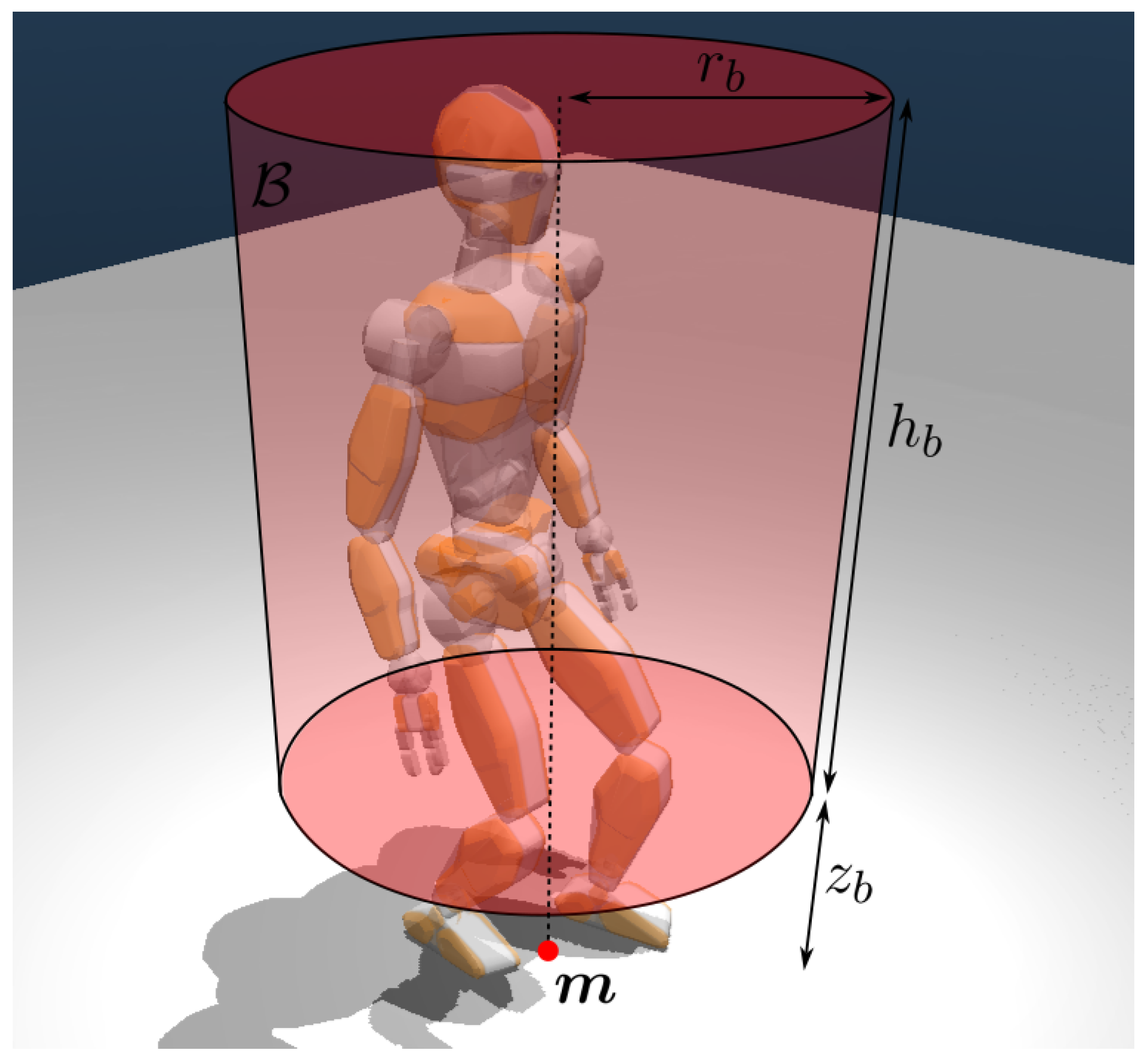

- R3

-

is reachable from through a collision-free motion.

Since information about the whole-body motion of the robot is not yet available during footstep planning (it will only be defined in the subsequent gait generation phase), this requirement can only be tested conservatively. In particular, we say that R3 is satisfied if (

i) a collision-free swing foot trajectory

from

to

can be found, and (

ii) a suitable volume

accounting for the maximum occupancy of the humanoid upper body at stance

is collision-free. More precisely,

is a vertical cylinder whose base has radius

, center at the midpoint

between the footsteps, and is raised from the ground by

, which represents the average distance between the ground and the hip (

Figure 4).

4.2. Algorithm

At the beginning, is rooted at , the initial stance of the humanoid. Then, is expanded using an RRT*-like strategy. The generic iteration consists of: selecting a vertex for expansion, generating a candidate vertex, choosing a parent for the new vertex and rewiring the tree. We will describe these individual steps below, right after some quick preliminaries.

4.2.1. Preliminaries

We assume that an edge between two vertexes

and

of

has a cost

. The

cost of a vertex

v is then defined as

and represents the cost of reaching

v from the root of

. Then, the cost of a plan

ending at a vertex

v is

. In this paper, we let

for all edges in

. Correspondingly, the cost of a vertex is the length

1 of the corresponding plan in terms of number of edges (i.e., steps).

The algorithm will make use of the set of

neighbors of a vertex

, defined as

where

is the footstep-to-footstep metric, with

, and

is a threshold distance.

4.2.2. Selecting A Vertex For Expansion

A point

is randomly selected in

, and the vertex

is identified that is closest to

is identified according to the following vertex-to-point metric

where

is the midpoint between the feet at stance

v,

is a weight matrix , and

is the angle between the ground projection of the robot sagittal axis (whose orientation is the average of the yaw angles of the two footsteps) and the ground projection of the line joining

to

. Matrix

can be used to weigh differently vertical and horizontal displacements.

4.2.3. Generating A Candidate Vertex

After identifying the vertex

, a candidate footstep is generated in the kinematically admissible region associated to

. For simplicity, denote by

the pose of

. We first compute the

steppable region from

, i.e., the intersection between

and the collection

of planar regions that constitute the world:

By construction,

itself will be a collection of planar regions. One of these regions is randomly selected, and a sample point

is extracted from it. Also, a random yaw angle

is generated in

. Finally, we perform

foot snapping, a process that correctly places the footstep at

, with yaw angle

, by matching its pitch and roll angles to those of the associated planar region of

.

Once the candidate footstep

has been generated, it can be checked with respect to requirement R1 and R2. For the latter, note that the position constraint (

1) and the last of the angular constraints (

2) are automatically satisfied by the above procedure, and therefore only the pitch and roll rows of (

2) must be explicitly checked.

In order to check requirement R3, we invoke an engine that generates a swing foot trajectory from to . Such engine uses a Bezier curve as a parameterized trajectory; given the endpoints, such trajectory can be deformed through control points so as to change the apex height h along the motion. Once a a swing foot trajectory has been generated, it is checked for collision with the environment: if a collision is detected, h is increased and the process is repeated. If a maximum height has been reached without success, the candidate footstep is discarded.

If R1–R3 are satisfied, the candidate vertex is generated as , with ; however, adding to is postponed, as the planner first has to choose a parent for it. If, instead, one of the requirements is violated, we abort the current expansion and start a new iteration.

4.2.4. Choosing A Parent

Although

was generated from

, there might be a different vertex in the tree that leads to the same vertex with a lower cost. To find it, the planner checks for each vertex

whether setting

as parent of

satisfies requirements R2-R3, and whether this connection reduces the cost of

, that is

The vertex

that allows to reach

with minimum cost is chosen as its parent. If

, then

can be added to the tree together with the edge joining it to

. However, if a different parent

is chosen, the candidate vertex

must be modified by relocating its swing footstep to the support footstep of

. To this end, a new vertex

with

and

is generated and added to

as child of

. The edge between

and

corresponds to the swing foot trajectory

.

4.2.5. Rewiring

This final step checks whether

allows to reach with a lower cost some vertex already in

, and updates the tree accordingly. In particular, for each

, the procedure checks whether setting

as a child of

satisfies requirements R2-R3, and whether this connection reduces the cost of

, that is

If this is the case,

is modified (similarly to what was done when choosing a parent) by relocating its swing footstep to

, and then reconnected to

as a child of

. The edge between

and

corresponds to the swing foot trajectory

. Finally, for each child

of

, the swing foot trajectory

from the relocated

to

is generated and the edge between

and

is accordingly updated.

4.3. Pseudocode

For convenience, the pseudocode of the footstep planning algorithm so far described is given in Algorithm 1.

|

Algorithm 1:FootstepPlanner() |

Require:, , ,

Initialize(, ))

while TimeNotExpired() do

← RandomPointGenerator

← NearestNeighborVertex(, ) ← GenerateCandidateFootstep() if R1() AND R2() then

← SwingTrajectoryGenerator() if R3() then

Neighbors() ChooseParent()

AddVertex() Rewire() end if

end if

-

end while

return

|

When the time budget expires, we stop tree expansion and retrieve , the set of vertexes v such that . From this, we extract the vertex with minimum cost and obtain the optimal footstep plan as the branch of joining the root to .

4.4. Footstep Planning: Numerical Results

The proposed footstep planner was implemented in C++ on a laptop equipped with an AMD Ryzen 7 6800HS CPU and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3050 GPU. The chosen humanoid is JVRC1, an open-source virtual robot having a total of 44 joints created for the Japan Virtual Robotics Challenge [

19]. JVRC1 is similar to the HRP series humanoids in terms of mechanical design, thus representing a realistic yet convenient simulation platform.

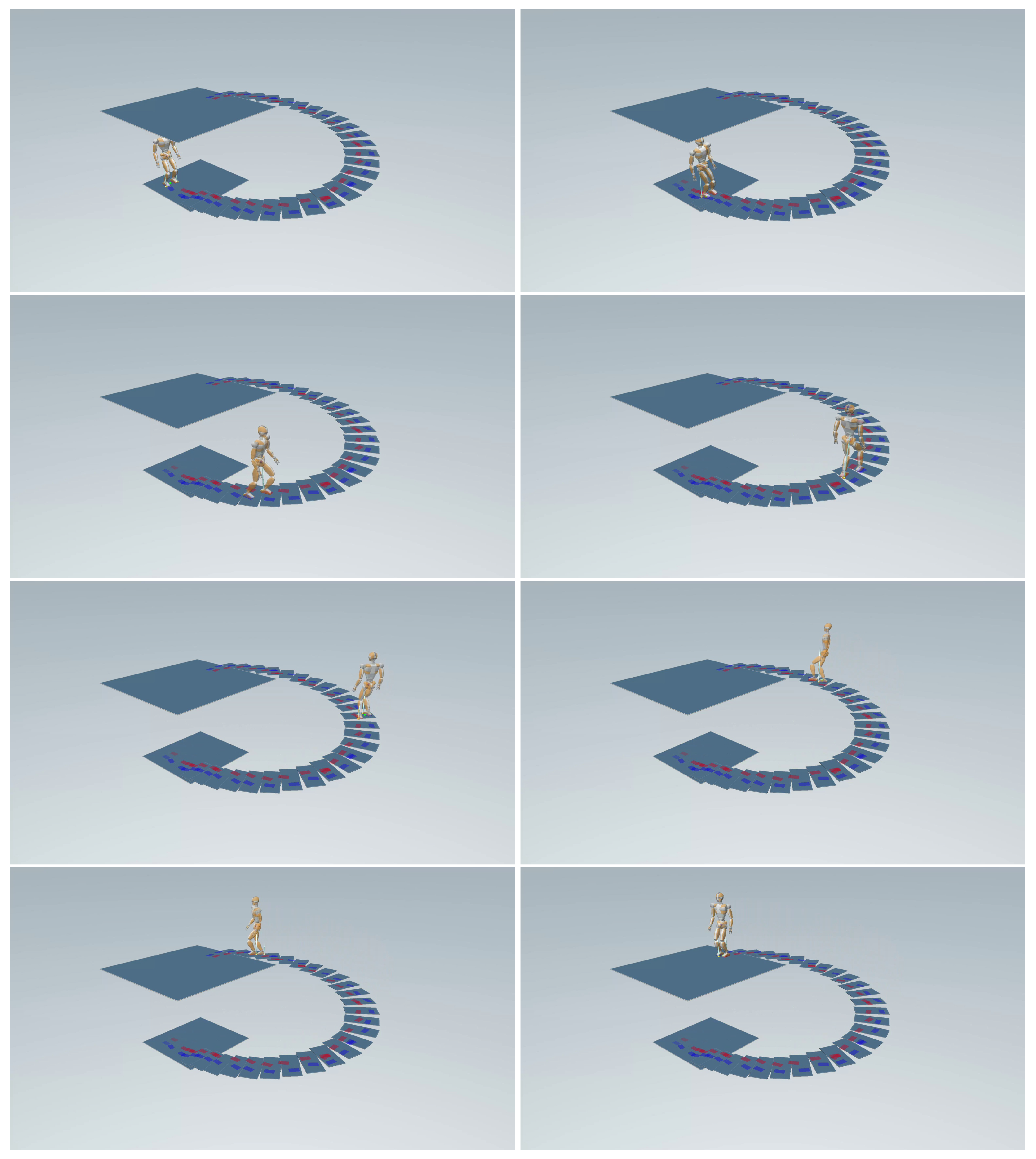

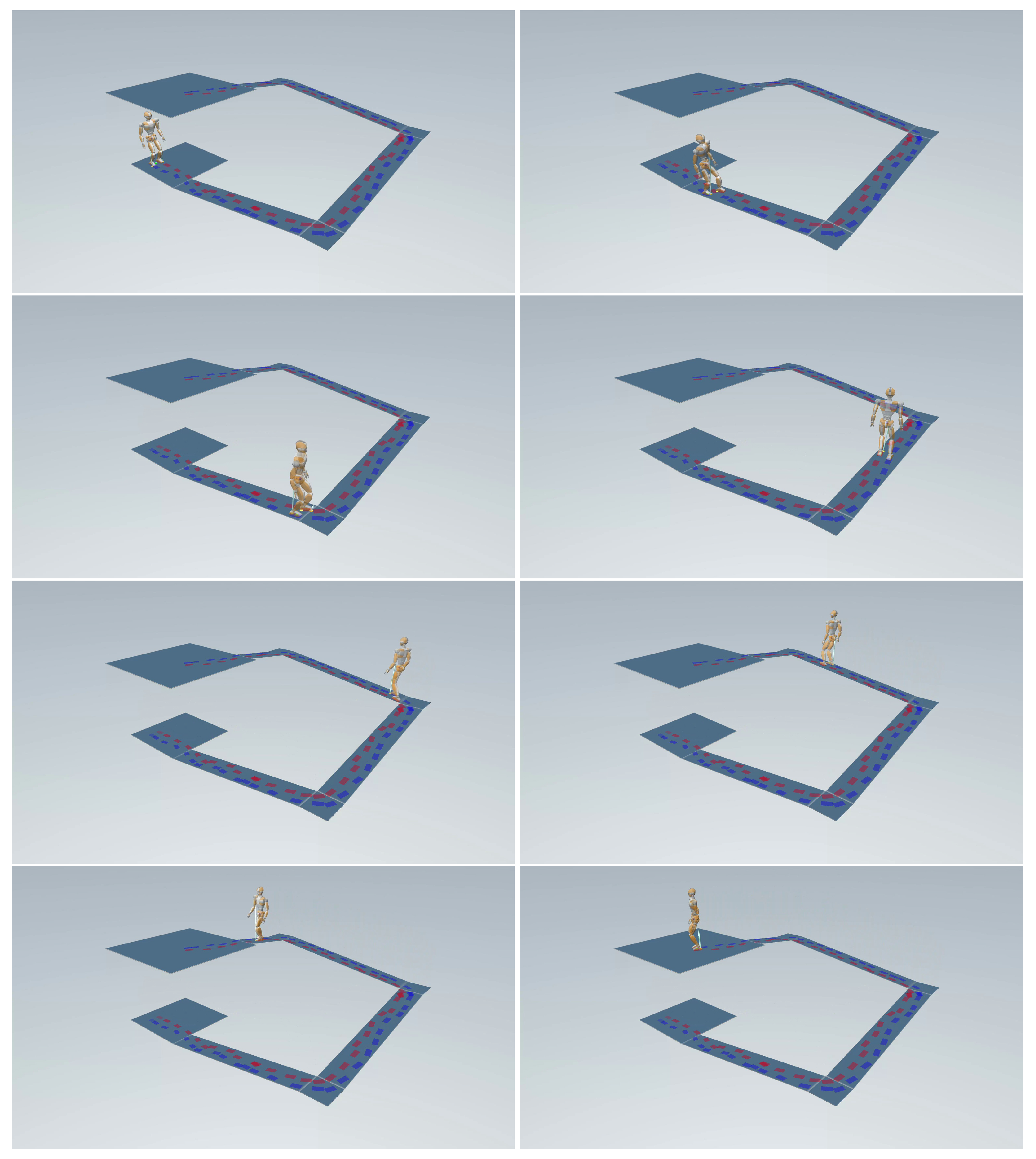

A campaign of planning experiments took place over four scenarios of different complexity (see

Figure 5):

Single Floor. This environment includes elevation changes, ramps (both ascending and descending) and obstacles.

Multi-Floor with Stairs. This is an environment with two floors connected by 23 steps.

Spiral Staircase. A spiral staircase with 26 steps connects two floors.

Multi-Floor with Ramps. In this environment, the two floors are connected by four inclined ramps and three landings.

In all scenarios, the robot has to reach a circular goal region of radius 0.3 m. In the footstep planner we have set m, m, m, m, m, m, rad, rad, rad, m, m, and m.

Figure 5 shows some example of successful footstep plans obtained in the four scenarios using the proposed algorithm.

Table 1 gives details about the performance of the planner in each scenario, for different values of the time budget, with each row reporting average results over 30 runs of the planner (1st Plan is the time needed by the footstep planner to generate the first plan that reaches the goal). A run is considered unsuccessful if the planner terminates without placing any footstep in the goal region. Note that increasing the time budget consistently improves the success rate, suggesting that the proposed footstep planner is probabilistically complete.

Overall, the results highlight the effectiveness of the proposed planner in rather complex 3D scenarios, even in the presence of stairs and ramps. See the concluding section for some hints at possible improvements of our planner.

5. Control Architecture

This section describes the control pipeline, which consists of the IS-MPC module followed by the whole-body controller (see

Figure 2).

5.1. Is-Mpc Gait Generation

Gait generation is the process of generating a feasible trajectory for the CoM position , such that the robot realizes the assigned footstep plan and maintains balance. This last requirement can be formulated as a constraint on the position of the Zero Moment Point (ZMP), which is the point of application of the equivalent ground reaction force.

To generate the CoM trajectory, we use Model Predictive Control (MPC), which optimizes trajectories over a certain horizon, using a model to predict the evolution of the system.

5.1.1. Prediction Model

Our prediction model is a 3D extension of the classic Linear Inverted Pendulum (LIP), which has the ZMP as input and allows for vertical motion of the CoM [

15,

20]. By neglecting the internal angular momentum variation, we have

where

g is the gravity acceleration. To remove the nonlinear coupling between the horizontal and vertical components, we impose

, where

is a constant parameter. The resulting model is expressed as

where

is a constant drift. This means the 3D LIP is at an equilibrium when the CoM and ZMP are vertically displaced by

; this should be taken into account when choosing the value of

. In our formulation, we dynamically extend (

3) so that the input is the ZMP velocity

, rather than the position

, in order to generate smoother trajectories.

5.1.2. ZMP constraints

In the classic LIP, the condition for balance requires the ZMP to stay within of the support polygon of the robot, which however is no more defined in a 3D setting. A sufficient condition for ensuring balance in this case is that the ZMP must belong to a pyramidal region , with apex at the robot CoM and edges going through the vertexes of the convex hull of the contact surfaces. Since this condition is nonlinear, we resort to the following conservative approximation.

Consider a

moving box with constant dimensions

along the three axes. Its center

moves in the following way: during single support phases it coincides with the position of the support foot, while during double support phases it performs a roto-translation from the position of the previous support foot to the position of the next. By properly choosing

,

and

one may guarantee that

is always contained in

[

17].

At a generic time instant

, a linear ZMP constraint can then be written as

where

is the rotation matrix associated to the orientation of the moving box at

, and the

j superscript denotes the variable at

.

5.1.3. Stability Constraint

While keeping the ZMP inside (and therefore, inside ) is sufficient for balance, it does not by itself guarantee that the COM trajectories are bounded with respect to the ZMP. This is due to the well-known fact that the LIP model includes one unstable mode, which can be isolated by defining the variable .

To avoid divergence, IS-MPC enforces the following

stability condition:

This is a relationship between the current value of

and the future of the ZMP trajectory, and is therefore noncausal. To obtain a causal condition, we split the integral in two parts, the first from

to

(the final instant of the prediction horizon) and the second from

to infinity. While the first integral can be expressed in terms of the MPC decision variables

, the second can be computed by conjecturing a trajectory

of

(

anticipative tail) on the basis of information contained in the footstep plan:

The stability constraint can then be written as

5.1.4. IS-MPC

At each iteration, IS-MPC solves the following quadratic program:

where

is a positive weight. After solving the quadratic program, the first optimal sample

is used to integrate the dynamically extended model (

3) and obtain the next sample of the reference CoM position

and velocity

, as well as of the corresponding ZMP position

. The corresponding CoM acceleration can then be computed from (

3). All these terms are sent to the whole-body control module, where they are used to set up the CoM tracking task.

5.2. Whole-Body Controller

Commands to be sent to the robot joints are generated by a whole-body controller which works in two stages. A first stage determines appropriate joint accelerations and contact forces by solving a constrained quadratic program, and a second stage computes the associated joint torques via inverse dynamics.

5.2.1. Task References

The input to the whole-body controller is a set of reference trajectories, one for each task. The set of tasks is {com, left, right, torso, joint}, which respectively represent:

com: the CoM reference, generated by the IS-MPC module;

left/right: foot pose references, generated by the footstep planner;

torso: a reference torso orientation, typically chosen to be upright;

joint: a reference joint posture (for solving kinematic redundancy).

Denote the generic task variable by

,

, and its reference position, velocity and acceleration by

,

and

, respectively.

2 The desired acceleration

is then defined as

where the reference acceleration is used as feedforward and the PD feedback is aimed at robustifying kinematic inversion. The desired acceleration

will be realized provided that the following relationship holds:

where

is the Jacobian of the

i-th task.

5.2.2. Robot Dynamics

The robot dynamics can be written as

Here,

is the inertia matrix, the configuration

is the stack of the floating base (unactuated) variables and the joint (actuated) variables,

contains the corresponding pseudovelocities,

collects Coriolis, centrifugal and gravitational terms,

are the joint torques, and

denotes the Jacobian of the point of application of the

i-th contact force

, with

.

Equation (

6) can be partitioned to highlight the unactuated and the actuated dynamics:

where we have omitted the dependence on

and

for compactness.

5.2.3. Constraints

The first constraint enforces the unactuated part of (

7):

We do not directly enforce the actuated dynamics (which would require adding

as a decision variable) because

will not explicitly appear in our quadratic program; therefore, it can be computed a posteriori from the inverse dynamics without affecting the optimization process.

3

The second set of constraints guarantees stationary contacts by imposing zero acceleration to the left and/or right foot, depending on the specific support phase:

The third set of constraints enforces limits on joint velocities and positions:

where

is the duration of a sampling interval.

The last set of constraints requires each contact force

to be contained in the friction cone, ensuring that no slipping occurs:

where

is the friction coefficient,

is the normal component of

, and

are its tangential components along the

x and

y axes of the foot frame at the contact. Note that

(i) a pyramidal approximation of the friction cone has been used to maintain linearity, and

(ii) these constraints automatically imply

, i.e., unilaterality of the contact forces.

5.2.4. Quadratic Program

At each iteration, the first stage of the whole-body controller solves the following QP problem:

5.2.5. Inverse Dynamics

Once

and the contact forces

have been obtained by solving the above QP, the joint torques can be computed using the actuated dynamics in (

7), i.e.,

6. Simulations

We now complement the footstep planning results of

Section 4.4 by presenting dynamic simulations of the JVRC1 robot executing the planned motions in MuJoCo, which guarantees high physical accuracy. IS-MPC runs at

, uses a sampling interval of 0.1 s and a control horizon of 2 s, whereas the whole-body controller runs at

(i.e.,

ms). Contacts are modeled with 4 forces per foot, so that

or 8 depending on the support phase. Finally, all quadratic programs (QP) are solved with HPIPM [

21], which requires under

to compute a solution, ensuring real-time capability.

The simulation results are shown via successive snapshots in

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 and, in form of video clips, at

https://youtu.be/RFPrQjY2tD8. As expected, the robot was able to efficiently and robustly realize all footstep plans, even in the presence of stairs or inclined ramps.

7. Conclusions

The proposed framework represents a humanoid motion generation scheme that enables navigation in complex 3D environments, including multiple floors and inclined surfaces. We ran an extensive campaign in order to validate the performance of the pipeline (footstep planner, gait generation and whole body control) in several different scenarios via dynamic simulations on a JVRC1 robot in MuJoCo. Our results show that our framework is effective and robust in very complex environments, paving the way for further promising research.

Future work will explore several directions, including:

Author Contributions

The individual contributions for this article were as follows: Conceptualization, M.C., N.S., L.L., and G.O.; methodology, D.M., M.C., N.S., L.L., and G.O.; software, D.M., M.C., and N.S.; validation, D.M., M.C., and N.S.; formal analysis, D.M., M.C., N.S., L.L., and G.O.; investigation, D.M., M.C., N.S., L.L., and G.O.; resources, M.C., N.S., L.L., and G.O.; data curation, D.M., M.C., N.S., L.L., and G.O.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M., M.C., N.S., L.L., and G.O.; writing—review and editing, M.C., N.S., L.L., and G.O.; visualization, D.M., M.C., N.S., L.L., and G.O.; supervision, M.C., N.S., L.L., and G.O.; project administration, M.C., N.S., L.L., and G.O.; funding acquisition, L.L. and G.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Nicola Scianca has been fully supported by PNRR MUR project PE0000013-FAIR.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available upon request from the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hauser, K.; Bretl, T.; Latombe, J.C.; Harada, K.; Wilcox, B. Motion Planning for Legged Robots on Varied Terrain. The International Journal of Robotics Research 2008, 27, 1325–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chestnutt, J.; Lau, M.; Cheung, G.; Kuffner, J.; Hodgins, J.; Kanade, T. Footstep Planning for the Honda ASIMO Humanoid. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE Int. Conf. on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2005; pp. 629–634. [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann, J.S.; Fukuchi, M.; Fujita, M. Real-time path planning for humanoid robot navigation. In Proceedings of the 19th Int. Joint Conf. on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI); 2005; pp. 1232–1237. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, R.J.; Wiedebach, G.; McCrory, S.; Bertrand, S.; Lee, I.; Pratt, J. Footstep Planning for Autonomous Walking Over Rough Terrain. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Int. Conf. on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2019; pp. 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, B.; Calvert, D.; Bertrand, S.; McCrory, S.; Griffin, R.; Sevil, H.E. GPU-accelerated rapid planar region extraction for dynamic behaviors on legged robots. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/RSJ Int. Conf. on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). IEEE; 2021; pp. 8493–8499. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, B.; Calvert, D.; Bertrand, S.; Pratt, J.; Sevil, H.E.; Griffin, R. Efficient Terrain Map Using Planar Regions for Footstep Planning on Humanoid Robots. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE-RAS Int. Conf. on Humanoid Robots (Humanoids). IEEE; 2024; pp. 8044–8050. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, T. Hierarchical RRT for Humanoid Robot Footstep Planning with Multiple Constraints in Complex Environments. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/RSJ Int. Conf. on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); 2012; pp. 3187–3194. [Google Scholar]

- Wieber, P.B. Trajectory Free Linear Model Predictive Control for Stable Walking in the Presence of Strong Perturbations. In Proceedings of the 6th IEEE-RAS Int. Conf. on Humanoid Robots (Humanoids); 2006; pp. 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Caron, S.; Escande, A.; Lanari, L.; Mallein, B. Capturability-based Pattern Generation for Walking with Variable Height. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2019, 36, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englsberger, J.; Ott, C.; Albu-Schäffer, A. Three-Dimensional Bipedal Walking Control Based on Divergent Component of Motion. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2015, 31, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.H.; Cho, B.K. Slope walking of humanoid robot without IMU sensor on an unknown slope. Robotics and autonomous systems 2022, 155, 104163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedebach, G.; Bertrand, S.; Wu, T.; Fiorio, L.; McCrory, S.; Griffin, R.; Nori, F.; Pratt, J. Walking on partial footholds including line contacts with the humanoid robot Atlas. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE-RAS Int. Conf. on Humanoid Robots (Humanoids). IEEE; 2016; pp. 1312–1319. [Google Scholar]

- Caron, S.; Pham, Q.C.; Nakamura, Y. ZMP support areas for multicontact mobility under frictional constraints. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2016, 33, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scianca, N.; De Simone, D.; Lanari, L.; Oriolo, G. MPC for Humanoid Gait Generation: Stability and Feasibility. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2020, 36, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamparelli, A.; Scianca, N.; Lanari, L.; Oriolo, G. Humanoid Gait Generation on Uneven Ground using Intrinsically Stable MPC. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaldone, F.M.; Scianca, N.; Lanari, L.; Oriolo, G. From walking to running: 3D humanoid gait generation via MPC. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 2022, 9, 876613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipriano, M.; Ferrari, P.; Scianca, N.; Lanari, L.; Oriolo, G. Humanoid motion generation in a world of stairs. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2023, 168, 104495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, S.; Frazzoli, E. Sampling-based algorithms for optimal motion planning. Int. J. of Robotics Research 2011, 30, 846–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okugawa, M.; Oogane, K.; Shimizu, M.; Ohtsubo, Y.; Kimura, T.; Takahashi, T.; Tadokoro, S. Proposal of inspection and rescue tasks for tunnel disasters — Task development of Japan virtual robotics challenge. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Symposium on Safety, Security, and Rescue Robotics (SSRR); pp. 1–2.

- Smaldone, F.M.; Scianca, N.; Lanari, L.; Oriolo, G. From Walking to Running: 3D Humanoid Gait Generation via MPC. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frison, G.; Diehl, M. HPIPM: A high-performance quadratic programming framework for model predictive control. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 6563–6569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belvedere, T.; Scianca, N.; Lanari, L.; Oriolo, G. Joint-Level IS-MPC: A Whole-Body MPC with Centroidal Feasibility for Humanoid Locomotion. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). IEEE; 2024; pp. 11240–11247. [Google Scholar]

| 1 |

See [ 17] for other interesting definitions of the cost of a plan, such as the total height variation or the minimum obstacle clearance. |

| 2 |

With a small abuse, we are using a time derivative notation also for angular task variables. |

| 3 |

If one wants to minimize torque effort or impose torque limits, must be included in the decision variables, and then the actuated dynamics should be added as a constraint. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).