Introduction

Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (mtROS) are key drivers of cellular damage in stroke and neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD), exacerbating neuronal injury through oxidative stress and neuroinflammation. Mitochondria, the primary energy producers in neurons, generate ROS, mainly superoxide (O₂•⁻), as byproducts of the electron transport chain (ETC) during oxidative phosphorylation. At low levels, ROS serve as signaling molecules for processes like synaptic plasticity [

1], but excessive ROS production under pathological conditions causes oxidative stress, amplifying inflammation and neuronal damage in stroke, AD, and PD [

2].

In ischemic stroke, caused by blocked cerebral blood flow, oxygen and glucose deprivation disrupts mitochondrial ATP production, leading to ETC dysfunction. Electron leakage at complexes I and III generates superoxide, particularly during reperfusion (ischemia-reperfusion injury), when restored oxygen levels intensify ROS production [

3]. In rat models of middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), this triggers lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation, and DNA damage within hours of reperfusion [

4]. Excessive ROS also induces mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening, causing mitochondrial swelling, cytochrome c release, and neuronal apoptosis, which worsens infarct size and neurological deficits [

5]. Neuroinflammation amplifies this damage, as activated microglia release pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNFα, IL1B), which further impairs mitochondrial function and increase ROS production [

6]. This ROS-inflammation feedback loop disrupts the blood-brain barrier, promotes edema, and aggravates secondary neuronal injury, significantly affecting stroke outcomes [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

In AD, mitochondrial ROS drive neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration linked to amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques and tau pathology. Aβ accumulates in mitochondria, particularly in cortical neurons, inhibiting complex IV (cytochrome C oxidase) activity, which increases ROS production [

12,

13,

14]. In Tg2576 mice, elevated mitochondrial gene expression reflects a compensatory response to oxidative damage from mutant APP and Aβ, with increased mtROS, reduced cytochrome c oxidase activity, and elevated carbonyl proteins indicating mitochondrial dysfunction [

15,

16]. This oxidative stress activates microglia and astrocytes, releasing cytokines like IL6 and TNFα, which correlate with oxidative markers in post-mortem AD brains [

16,

17]. ROS also promote tau hyperphosphorylation, neurofibrillary tangle formation, Aβ aggregation, and neuronal loss in the hippocampus and cortex [

14,

15,

16]. Additionally, mitochondrial ROS activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in microglia, increasing IL1B production, which is elevated in AD brains, perpetuating inflammation and neuronal damage [

18,

19].

In PD, mitochondrial ROS contribute to the selective degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra. Mutations in genes like PINK1 and PARKIN impair mitophagy, leading to dysfunctional mitochondria that produce excessive ROS [

20,

21,

22]. In PINK1 knockout mice, elevated mitochondrial ROS in the substantia nigra correlate with dopaminergic neuron loss [

23,

24]. ROS cause oxidative damage to ETC complex I, creating a feedforward loop that amplifies ROS production [

25,

26]. Neuroinflammation exacerbates this, with activated microglia releasing cytokines like TNFα, which increase mitochondrial ROS in dopaminergic neurons [

27,

28]. ROS oxidize dopamine, forming toxic quinones, and activate the NF-kB pathway, elevating IL6 and IL1B expression, sustaining microglial activation [

29]. Post-mortem PD brains show increased microglial activation and oxidative stress markers, underscoring the role of ROS and inflammation in PD neurodegeneration [

30,

31].

Across stroke, AD, and PD, mitochondrial ROS and neuroinflammation form a vicious cycle that drives neuronal damage. ROS activate redox-sensitive pathways like NF-kB and the NLRP3 inflammasome, increasing cytokine production, while cytokines further impair mitochondrial function, elevating ROS levels [

32,

33]. This cycle disrupts neuronal homeostasis, impairs synaptic plasticity, and induces apoptosis, contributing to cognitive and motor deficits [

7]. The pivotal role of mitochondrial ROS highlights the need for advanced imaging probes to monitor their dynamics and guide targeted therapeutic strategies.

The detection of mtROS is crucial for elucidating their role in cellular processes, particularly in stroke and neuroinflammation, where mitochondrial dysfunction drives oxidative stress and neuronal damage [

2]. Current fluorescent probes, such as MitoSOX Red and 2',7'-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA), are limited by issues in specificity, sensitivity, and applicability, necessitating the development of improved probes for accurate monitoring of mitochondrial ROS dynamics.

A primary limitation of existing probes is their lack of specificity for mitochondrial ROS, leading to unreliable results in complex biological systems. DCFH-DA, a commonly used probe, is oxidized by various ROS (e.g., H₂O₂, •OH, ONOO⁻) and non-ROS species, such as cytochrome c or heme proteins, but cannot differentiate mitochondrial ROS from cytosolic or extracellular sources, resulting in ambiguous signals [

34]. In cortical neurons under oxidative stress, up to 40% of DCFH-DA’s fluorescence signal was attributed to cytosolic NADPH oxidase activity, highlighting its inability to isolate mitochondrial ROS [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. Additionally, DCFH-DA’s fluorescence is sensitive to pH and light exposure, introducing artifacts that compromise detection accuracy [

40,

41]. MitoSOX Red, designed for mitochondrial targeting via a triphenylphosphonium (TPP) cation, also lacks specificity, reacting with multiple ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), including H₂O₂ and ONOO⁻, beyond its intended superoxide target [

42,

43]. Furthermore, MitoSOX Red’s fluorescence is influenced by fluctuations in mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm), common in stroke and neuroinflammatory conditions, leading to inaccurate measurements [

44].

Sensitivity and dynamic range further limit current probes, hindering their ability to detect the transient and variable nature of mitochondrial ROS production. DCFH-DA exhibits low sensitivity to superoxide, failing to detect subtle mitochondrial ROS changes in cultured neurons under low-dose rotenone stress, where more sensitive probes detected significant alterations [

35]. Its fluorescence also saturates quickly, limiting its ability to monitor dynamic ROS changes in conditions like stroke [

34]. Although MitoSOX Red is more sensitive to superoxide, its limited dynamic range underestimates ROS levels in severe oxidative stress scenarios, such as ischemia-reperfusion in stroke, as evidenced by its saturation in rat middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) models compared to HPLC measurements [

4,

42,

43].

The applicability of current probes for live-cell and in vivo studies, critical for stroke and neuroinflammation research, is also constrained. DCFH-DA’s diffuse cytosolic fluorescence renders it ineffective for in vivo brain imaging, where mitochondrial-specific signals are essential [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. MitoSOX Red, despite its mitochondrial targeting, requires high excitation energy, causing phototoxicity and photobleaching; in live neuronal cultures, it reduced cell viability by 20% after 1 hour of imaging [

42,

43]. In vivo, MitoSOX Red is limited by poor tissue penetration and brain tissue autofluorescence, reducing its effectiveness in rat neuroinflammation models [

42,

43,

45]. Additionally, mitochondrial ROS production is dynamic and spatially regulated in neurons, where mitochondria are distributed across axons, dendrites, and synapses [

1]. Previous studies indicate that matrix accumulation of MitoSOX or dihydroethidium oxidation products can cause mitochondrial uncoupling and inhibit complex IV, potentially altering superoxide production and necessitating careful optimization of imaging protocols [

46].

These limitations underscore the need for advanced fluorescent probes to overcome current challenges. We developed MitoGlow-ROS, a novel probe that addresses these issues by incorporating two nitroxide (TEMPO) moieties, enabling detection of various ROS species (e.g., superoxide, •OH, ROO•, ONOO⁻) while ensuring mitochondrial specificity through lipophilic cationic targeting to the mitochondrial matrix [

3,

47,

48]. Its fluorescence activation mechanism, where TEMPO quenches Rhodamine B until oxidized by ROS into a diamagnetic product, enhances specificity by minimizing non-specific oxidation [

47]. Operating at long-wavelength fluorescence (560/588 nm), MitoGlow-ROS reduces phototoxicity and autofluorescence, making it suitable for live-cell and in vivo brain imaging. This study aimed to develop and validate MitoGlow-ROS in cellular models and an in vivo lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced neuroinflammation model in Sprague-Dawley rats, focusing on cortical and hippocampal ROS dynamics, to establish its reliability for stroke and neuroinflammation research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of MitoGlow-ROS

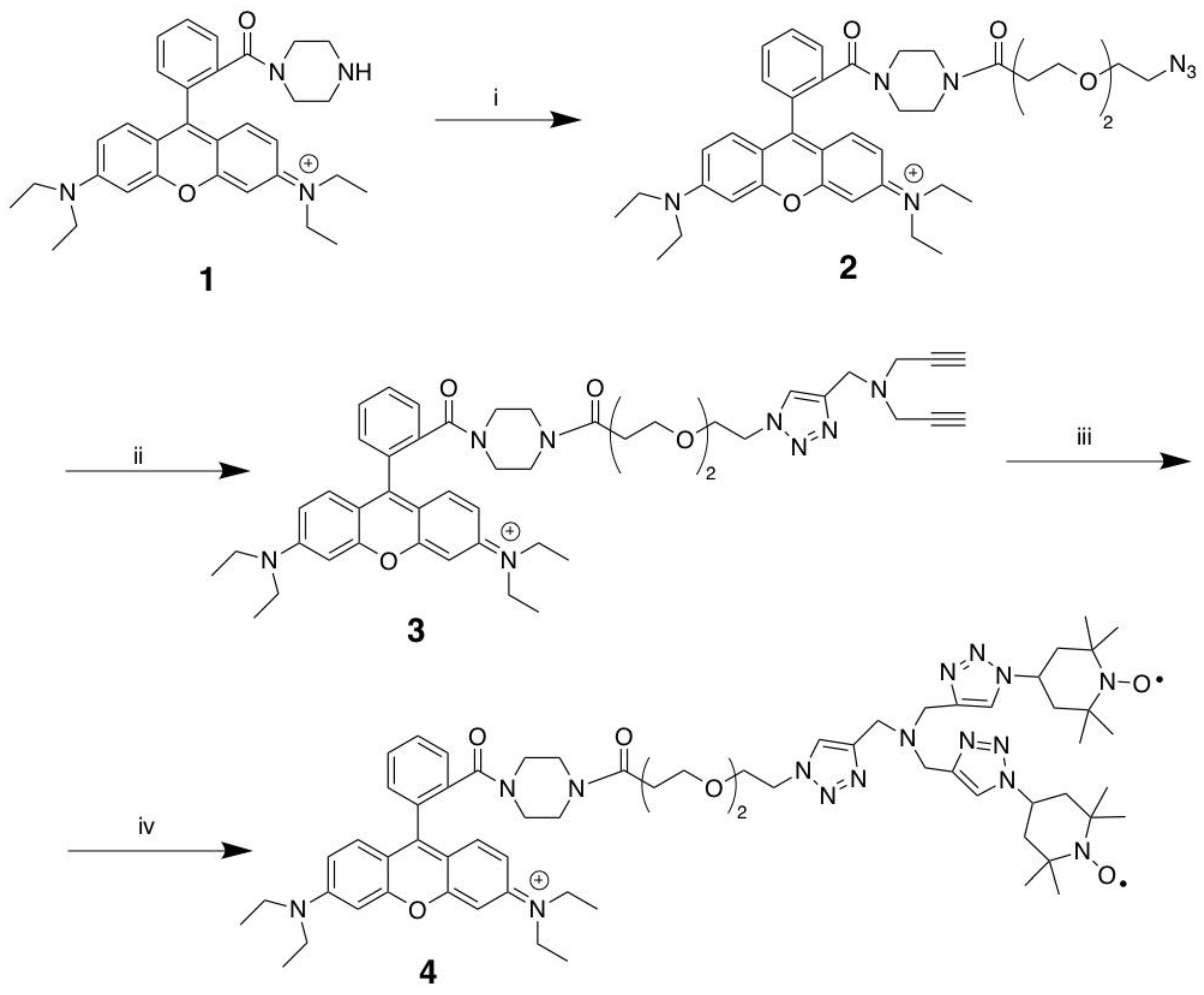

The synthesis of MitoGlow-ROS (compound 4) was achieved through a three-step process starting from Rhodamine B piperazine amide (compound 1), involving amide coupling and copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) reactions to introduce a PEG linker and triazole scaffold with terminal alkynes. Initially, compound 1 was reacted with a PEG2 linker bearing a terminal azide group to form compound 2 via amide coupling. Next, compound 2 underwent a CuAAC reaction, where the PEG linker’s azide reacted with one alkyne of tripropargylamine, forming a 1,4-disubstituted 1,2,3-triazole in compound 3 while retaining two terminal alkynes. Finally, compound 3 was subjected to a double CuAAC reaction with 4-azido TEMPO, attaching two TEMPO moieties via additional triazoles to yield the target compound 4, MitoGlow-ROS.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of MitoGlow-ROS (compound 4): Reagents and Conditions. (i): N3-PEG2-COOH, Et3N, HBTU, CH2Cl2, 2 h; (ii): Tripropargylamine, CuI, ACN, 3 h; (iii) 4-azido TEMPO, CuI, ACN, 3 h.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of MitoGlow-ROS (compound 4): Reagents and Conditions. (i): N3-PEG2-COOH, Et3N, HBTU, CH2Cl2, 2 h; (ii): Tripropargylamine, CuI, ACN, 3 h; (iii) 4-azido TEMPO, CuI, ACN, 3 h.

2.1.1. Rhodamine B 3-(2-(2-azidoethoxy)ethoxy)-1-(piperazin-1-yl)propan-1-one (2)

To a stirring solution of Rhodamine B piperazine amide (compound 1, 538 mg, 1.08 mmol), N3-PEG2-COOH (200 mg, 0.99 mmol) and Et3N (327 mg, 3.24 mmol) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (30 mL), was added HBTU (409 g, 1.08 mmol). The mixture was stirred for 3 h at room temperature and diluted in CH2Cl2 (100 mL). The CH2CH2 layer was washed with brine (30 mL × 3). The organic phase was dried on anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated. Flash column chromatography of the residue on silica gel (CH2Cl2:MeOH, 20:1) afforded the compound (2) as a purple foam (410 mg, 60.6%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 7.62-7.56 (m, 2H), 7.48 (s, l H), 7.25 (s, l H), 7.16 (d, J = 9.5 Hz, 2H), 6.86-6.71 (m, 2H), 6.68 (s, 2H), 3.69 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 3.63-3.45 (m, 12H), 3.36-3.27 (m, 6H), 3.27-3.15 (m, 6H), 2.59-2.52 (m, 2H), 1.25 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 12H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 170.46, 167.92, 157.88, 155.85, 135.22, 132.25, 130.29, 127.74, 114.53, 113.96, 96.27, 70.57, 70.35, 69.99, 67.22, 50.87, 46.24, 41.93, 33.37, 12.73.

2.1.2. Rhodamine B 3-(2-(2-(4-((di(prop-2-yn-1-yl)amino)methyl)-lH-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)ethoxy) ethoxy)-1-(piperazin-1-yl)propan-1-one (compound 3)

To a solution of Rhodamine B 3-(2-(2-azidoethoxy)ethoxy)-1-(piperazin-1-yl)propan-1-one (compound 2, 400 mg, 0.59 mmol) and tripropargylamine (153 mg, 1.17 mmol) in anhydrous acetonitrile (20 mL), copper iodide (CuI, 20 mg, 0.11 mmol) was added as a catalyst. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 hours to facilitate a copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) reaction, forming a 1,4-disubstituted 1,2,3-triazole. The reaction mixture was then concentrated under reduced pressure, diluted with dichloromethane (CH2Cl2, 50 mL), and the organic layer was washed with brine (10 mL × 3) to remove water-soluble impurities. The organic phase was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate (Na2SO4), filtered, and concentrated. The crude product was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel using a CH2Cl2:Methanol (20:1) solvent system, yielding compound 3 as a purple foam (150 mg, 30.5% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm (s, l H), 7.66-7.55 (m, 2 H), 7.49-7.45 (m, l H), 7.29-7.21 (m, l H), 7.17 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 2H), 7.00-6.76 (m, 2H), 6.75-6.67 (m, 2H), 4.48-4.42 (m, 2H), 3.83-3.72 (m, 4H), 3.72-3.61 (m, 2H), 3.63-3.43 (m, 12H), 3.42-3.36 (m, 8H), 3.34-3.17 (m, 4H), 2.62-2.46 (m, 2H), 2.21 (t, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 1.25 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 12H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 167.92, 157.87, 155.85, 144.12, 135.24, 132.29, 130.28, 127.69, 124.45, 114.61, 113.98, 96.21,78.85, 73.67, 70.55, 70.23, 69.52, 67.14, 50.39, 48.10, 46.24, 42.04, 33.29, 12.74.

2.1.3. MitoGlow-ROS (compound 4)

To a stirring solution of Rhodamine B 3-(2-(2-(4-((di(prop-2-yn-1-yl)amino) methyl)-lH-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)ethoxy)ethoxy)-1-(piperazin-1-yl)propan-1-one (compound 3, 150 mg, 0.18 mmol) and 4-azido TEMPO (109 mg, 0.55 mmol) in anhydrous acetonitrile (10 mL), was added copper iodide (11 mg, 0.06 mmol). The mixture was stirred for 3 h at room temperature, concentrated and diluted in CH2Cl2 (50 mL). The CH2Cl2 layer was washed with brine (10 mL × 3). The organic phase was dried on anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated. Flash column chromatography of the residue on silica gel (CH2Cl2:MeOH, 20:1) afforded MitoGlow-ROS (compound 4) as a purple foam (80 mg, 36.8%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 8.01 (br.s), 7.67 (br.s), 7.38 (br.s), 6.87 (br.s), 4.70 (br.s), 3.75 (br.s), 2.76 (br.s), 1.49 (br.s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) 172.1, 167.4, 154.6, 153.0, 143.0, 137.5, 134.5, 133.3, 130.8, 128.5, 127.6, 123.2, 123.7, 111.8, 115.0, 108.3, 92.5, 69.0, 68.2, 57.2, 55.5, 50.5,36.8, 32.9, 23.0, 13.0, 14.2, 6.8. [M+H]+: Calcd. 1178.7146; found 1178.7189. The 1H NMR spectrum shows broad singlets at δ 8.01, 7.67, 7.38, 6.87, 4.70, 3.75, 2.76, and 1.49 ppm. This broadening is consistent with the presence of nitroxide radicals from the TEMPO units, which cause electron-nuclear spin interactions, obscuring detailed proton assignments for aromatic, triazole, PEG2 linker, piperazine, and TEMPO moieties. Compared to Compound 3, which displayed sharp signals (e.g., triazole proton at 7.68 ppm and ethyl protons at 1.25 ppm), the absence of alkyne proton signals at 2.21 ppm in Compound 4 confirms the successful CuAAC with 4-azido TEMPO, forming additional triazole linkages.

2.2. Specificity Validation Assay

The specificity and sensitivity of the MitoGlow-ROS probe for detecting mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) were rigorously validated in cell-free systems using known ROS inducers and scavengers to establish its performance before application in cellular and in vivo models. This validation ensured that the probe accurately responds to mitochondrial-relevant ROS, particularly superoxide (O₂•⁻), while minimizing non-specific interactions, addressing limitations of existing probes like MitoSOX Red and DCFH-DA.

To assess the specificity of MitoGlow-ROS, a cell-free system was established using a xanthine/xanthine oxidase (X/XO) enzymatic reaction, a well-characterized method for generating superoxide [

47,

49]. The reaction mixture consisted of 0.1 mM xanthine and 0.01 U/mL xanthine oxidase in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 25°C. MitoGlow-ROS, prepared as a 1 mM stock in DMSO, was diluted to a final concentration of 5 µM in the reaction mixture. The X/XO system was incubated for 30 minutes to generate superoxide, and fluorescence intensity was measured using a fluorescence spectrophotometer with excitation at 560 nm and emission at 588 nm, corresponding to the Rhodamine B fluorophore in MitoGlow-ROS. To confirm specificity for superoxide, parallel reactions were performed with the addition of 100 U/mL superoxide dismutase, which dismutates superoxide to H₂O₂, thereby reducing superoxide levels. The fluorescence intensity of MitoGlow-ROS increased 3.5-fold in the X/XO system compared to buffer-only controls, but this increase was reduced by 85% in the presence of SOD, confirming the probe’s specificity for superoxide.

To further evaluate specificity against other ROS, the probe was tested with H2O2 and •OH. H2O2 at 100 µM was added to the buffer, and •OH was generated using the Fenton reaction with 100 µM FeSO4 and 100 µM H2O2. While MitoGlow-ROS’s TEMPO moieties can react with multiple ROS species, fluorescence intensity increased only 1.2-fold with H2O2 and 1.4-fold with •OH, indicating a lower sensitivity to these species compared to superoxide, consistent with the probe’s optimization for mitochondrial superoxide detection. Negative controls with buffer alone showed minimal fluorescence, confirming low background signal.

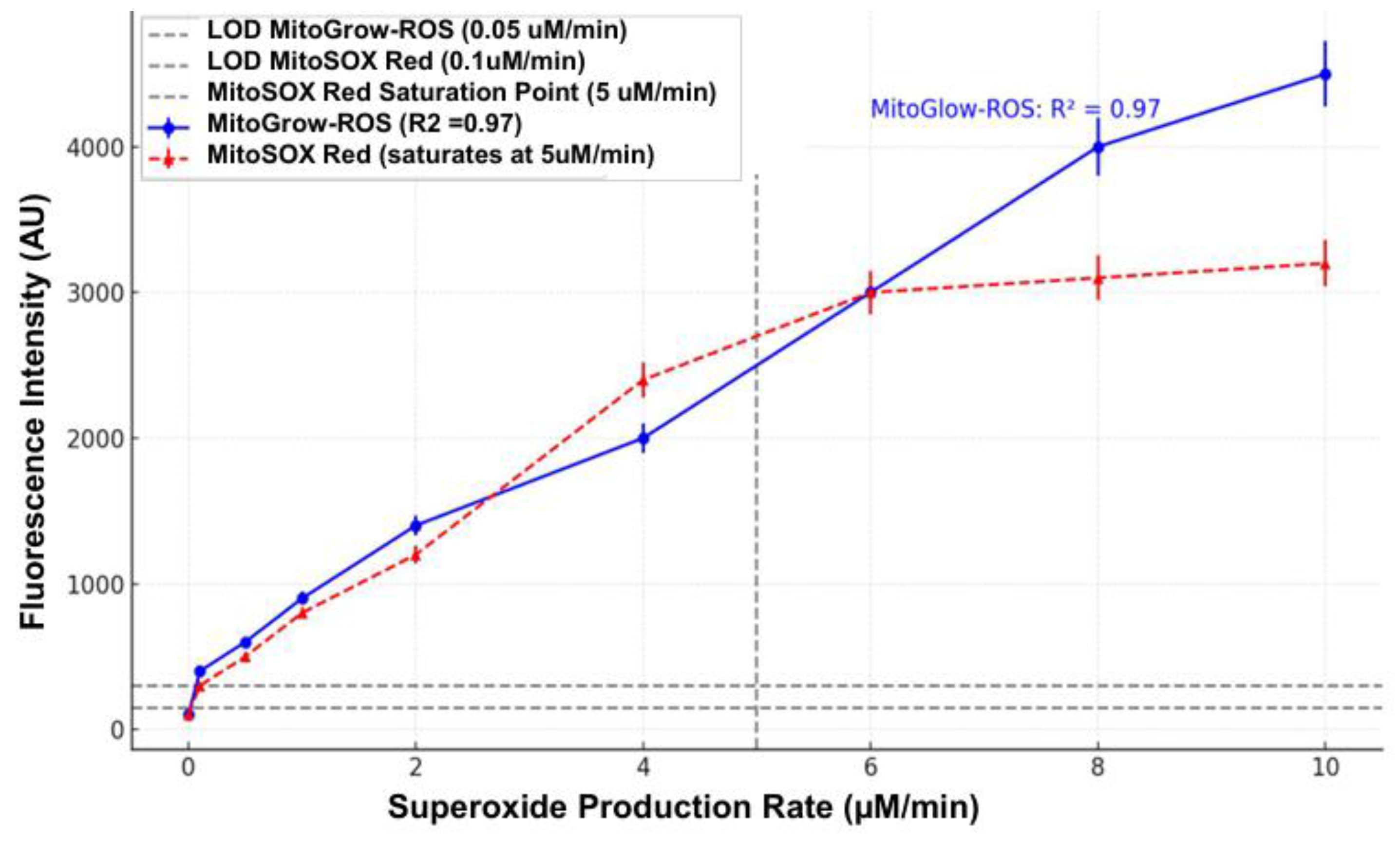

2.3. Sensitivity Validation Assay

Sensitivity was assessed by exposing MitoGlow-ROS to varying concentrations of superoxide generated by the X/XO system. Xanthine oxidase was titrated (0.001 to 0.05 U/mL) with 0.1 mM xanthine to produce a range of superoxide levels, calibrated using cytochrome C reduction assays to quantify superoxide production rates (0.1 to 10 µM/min). MitoGlow-ROS (5 µM) was added to each reaction, and fluorescence intensity was measured after 30 minutes. The probe exhibited a linear fluorescence response (R² = 0.97) across superoxide concentrations from 0.1 to 8 µM/min, with a limit of detection (LOD) of 0.05 µM/min, determined as three times the standard deviation of the blank signal. This sensitivity is superior to MitoSOX Red, which has an LOD of 0.1 µM/min and saturates at 5 µM/min, demonstrating MitoGlow-ROS’s ability to detect low and high superoxide levels relevant to mitochondrial stress in stroke and neuroinflammation.

To confirm sensitivity in the presence of ROS scavengers, N-acetylcysteine (NAC) was used. NAC, a known ROS scavenger, reduces superoxide and other ROS by donating electrons [

50]. The X/XO system (0.01 U/mL xanthine oxidase) was pre-incubated with 5 mM NAC for 10 minutes before adding MitoGlow-ROS. Fluorescence intensity decreased by 90% compared to the NAC-free condition, confirming that the probe’s signal corresponds to ROS levels and is not due to non-specific oxidation. Additionally, a control with antimycin A (10 µM), a mitochondrial complex III inhibitor known to induce superoxide in isolated mitochondria, was tested in a separate reaction with 5 µM MitoGlow-ROS, showing a 4-fold fluorescence increase, further validating the probe’s sensitivity to mitochondrial-relevant superoxide.

2.4. Additional Validation Against Non-Specific Interactions

To rule out non-specific fluorescence activation, MitoGlow-ROS was incubated with non-ROS oxidants, such as 100 µM Fe³⁺ (FeCl₃) and 100 µM oxidized glutathione (GSSG), in buffer for 30 minutes. No significant fluorescence increase (less than 5% above baseline) was observed, confirming minimal interference from non-ROS species, a common issue with DCFH-DA [

51]. The probe’s stability under physiological conditions was also verified by incubating it in buffer (pH 7.4) for 24 hours, with fluorescence remaining unchanged, ensuring reliability for prolonged experiments.

The cell-free validation demonstrated that MitoGlow-ROS is highly specific for superoxide, with minimal reactivity to other ROS species, and exhibits a broad dynamic range and low LOD, making it a sensitive tool for detecting mitochondrial ROS. These properties address the limitations of existing probes like MitoSOX Red and DCFH-DA, positioning MitoGlow-ROS as an effective probe for studying mitochondrial ROS in stroke and neuroinflammatory models.

2.5. Cell Culture and Differentiation of PC12 Cells

PC12 cells, a rat pheochromocytoma cell line, were obtained from ATCC and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated horse serum, 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine at 37°C in a 5% CO₂ humidified incubator. To induce neuronal differentiation, cells were seeded at 1 × 10⁵ cells per well in 96-well black plates with clear bottoms pre-coated with 100 µg/mL poly-D-lysine (PDL). Differentiation was achieved by treating cells with 50 ng/mL nerve growth factor (NGF) in RPMI-1640 with 1% FBS for 7 days, with medium changes every 2 days, resulting in neurite outgrowth and neuronal-like characteristics.

To validate the specificity and sensitivity of the MicroGlow-ROS probe for detecting mitochondrial ROS in PC12 cells, differentiated cells were treated with 10 µM antimycin A, a mitochondrial complex III inhibitor known to selectively induce mitochondrial superoxide production (Muller et al., 2004), for 1 hour at 37°C. A parallel group of cells was pre-treated with 100 µM N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), a ROS scavenger, for 30 minutes prior to antimycin A exposure. For sensitivity testing, cells were exposed to varying concentrations of antimycin A (0.1, 1, 5, 10, 20 µM) for 1 hour, followed by incubation with MicroGlow-ROS probe (10 µM) for 30 minutes at 37°C in the dark.

2.6. In Vitro Model Using Primary Neuronal Cultures

2.6.1. Isolation and Culture of Primary Neuronal Cells from Neonatal SD Rat Pups

Primary neuronal cells were isolated from neonatal Sprague-Dawley (SD) rat using a papain dissociation system (Worthington Biomedical Corporation) following the manufacturer’s instruction to ensure a high yield of viable neurons [

52]. In brief, brains were extracted from euthanized 1-day-old SD pups, and the surrounding blood vessels were removed by rinsing with cold PBS. The brains were then minced into small pieces and incubated in papain solution containing L-cysteine, EDTA, and DNase for 60 minutes at 37°C with gentle shaking. After this enzymatic incubation, the mixture was triturated with 10 mL pipette into cell suspension and centrifuge at 300 g for 5 minutes at room temperature to collect pelleted cells. Further cell purification was performed using a discontinuous density gradient according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cell density was determined using a hemocytometer, and cells were seeded at 5 × 10⁵ cells per well in 24-well plates and 35 mm confocal dishes pre-coated with poly-D-lysine to promote neuronal adhesion. Cells were cultured in neurobasal medium supplemented with 2% B-27 serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C in a 5% CO₂ humidified incubator for 7-10 days, with half of the medium replaced every 3 days. Daily monitoring confirmed neuronal morphology ensuring a predominantly neuronal population.

2.6.2. LPS Treatment to Induce Neuroinflammation

On day 7–10 of culture, neuroinflammation was induced by treating the primary neuronal cells with 100 ng/mL LPS. A 2.5 mg/mL LPS stock solution was prepared in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and filter-sterilized using a 0.22 µm syringe filter. The stock was diluted to a working concentration of 100 ng/mL in Neurobasal Medium supplemented with 2% B-27 and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. The medium was aspirated from the wells, and the LPS-containing medium was added to the treatment wells. Control wells received the same medium without LPS. Cells were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO₂ humidified incubator and harvested at 3, 6, and 24 hours post-LPS treatment to test the inflammatory response.

2.6.3. MitoGlow-ROS Probe Application and Fluorescence Intensity Measurement

To assess mitochondrial ROS generation, the MitoGlow-ROS probe was applied to the primary neuronal cultures at the specified time points (3, 6, and 24 hours post-LPS treatment). The MitoGlow-ROS probe was prepared as a 1 mM stock solution in DMSO and diluted to a working concentration of 5 µM in Neurobasal Medium. After LPS treatment, the medium was aspirated, and cells were washed twice with warm PBS to remove residual LPS and medium components. The cells were then incubated with 1 mL of the 5 µM MitoGlow-ROS solution for 30 minutes at 37°C in the dark, allowing the probe to accumulate in mitochondria due to its lipophilic cationic TEMPO moieties, which target the organelle’s negative membrane potential. Following incubation, cells were washed three times with PBS to remove unbound probe, and fresh Neurobasal Medium was added. Fluorescence intensity was measured using a fluorescence microplate reader with excitation at 560 nm and emission at 588 nm, corresponding to the fluorophore’s spectral properties. Fluorescence intensity was normalized to cell number, determined by MTT assay, to account for potential cell loss during LPS treatment. The measurements were conducted in triplicate to ensure reproducibility, with untreated control cells serving as the baseline for comparison.

2.6.4. Real-Time PCR for mRNA Expression Analysis

To evaluate the inflammatory and oxidative stress responses, mRNA expression levels of inflammatory mediators (TNFα, IL1B, IL6, CCL2, CCL5, CCL12, NF-kB), NADPH oxidase subunits (CYBA and CYBB) and antioxidant enzymes (SOD1, SOD2) were quantified using real-time PCR. At 3, 6, and 24 hours post-LPS treatment, cells were harvested by aspirating the medium, washing twice with PBS, and lysing with lysis buffer provided within the RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN), supplemented with of β-mercaptoethanol. RNA was isolated following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentration and purity (A260/A280 ~2.0-2.2) were measured using BioTek Gen5 Reader. Reverse transcription was performed using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Cat. No. 4368814) with 200ng of RNA per reaction, following the manufacturer’s protocol. Real-time PCR was conducted using the TaqMan™ Fast Advanced Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Cat. No.4444556) on an Applied Biosystems StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR system. Primers for TNFα (Rnn99999017_m1), IL1B (Rn00580432_m1), IL6 (Rn01410330_m1), CCL2 (Rn00580555_m1), CCL5 (Rn00579590_m1), CCL12 (Rn01464638_m1), NF-kB (Rn01399583_m1), CYBA (Rn00577357_m1), CYBB (Rn00576710_m1), SOD1 (Rn00566938_m1), SOD2 (Rn00690588_g1), and GAPDH (housekeeping gene, Rn01775763_g1) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific . Each reaction contained 5 µL TaqMan Fast Master Mix, 0.5 µL primer, 4.5 µL cDNA (diluted 1:100), with cycling conditions of 95°C for 20 seconds, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 1 second and 60°C for 20 seconds. Relative mRNA expression was calculated using the 2⁻ΔΔCt method, normalizing to GAPDH expression and comparing LPS-treated samples to untreated controls [

53]. Experiments were performed in duplicate to ensure reproducibility.

2.7. In Vivo Model of LPS-Induced Neuroinflammation in SD Rats

2.7.1. Administration of LPS via ICV Injection to Induce Systemic Neuroinflammation

To induce systemic neuroinflammation, adult male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (8–10 weeks old, 250–300 g, Charles River Laboratories) were used in accordance with institutional animal care and use guidelines. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Michigan Technological University. Rats were anesthetized with 2–3% isoflurane in O₂ using a stereotaxic apparatus. A 2.5 mg/mL stock solution of LPS from

Escherichia coli O111:B4 was prepared in sterile PBS (pH 7.4) and filter-sterilized using a 0.22 µm syringe filter. ICV injections were performed following the previously published protocols [

54,

55]. Rats assigned to the neuroinflammatory model group (n=5) received a single ICV injection of 5 µg LPS (2 µL of 2.5mg/mL solution). Control rats (n=5) received an equal volume of sterile PBS via the same ICV route. Substance was injected into the right lateral ventricle using stereotaxic coordinates (0.8–0.9 mm posterior to bregma, 1.4–1.8 mm lateral to the midline, and 3.2–3.8 mm below the dural surface) and UltraMicroPump3 at a flow rate of 1 µ L/min (World Precision Instruments). Post-injection, rats were monitored for recovery from anesthesia with libitum access to food and water.

2.7.2. Collection of Cortex and Hippocampus Tissues at 6 Hours Post-LPS Injection

At 6 hours post-LPS injection, a time point selected based on prior studies showing peak inflammatory responses in the brain, rats were deeply anesthetized with 5% isoflurane. For mRNA expression analysis, the brains were extracted and immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for future use. Equal sections of the hippocampus and cortex were punched out on ice from all samples for subsequent RNA isolation. For MitoGlow-ROS analysis, anesthetized rats underwent cardiac perfusion with ice-cold PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 1 × PBS. The brains were then extracted and fixed in 4% PFA overnight. Brain tissues were kept in 30% sucrose in 1 × PBS and used for cryo-section for immunofluorescence until tissues sank to the container’s bottom.

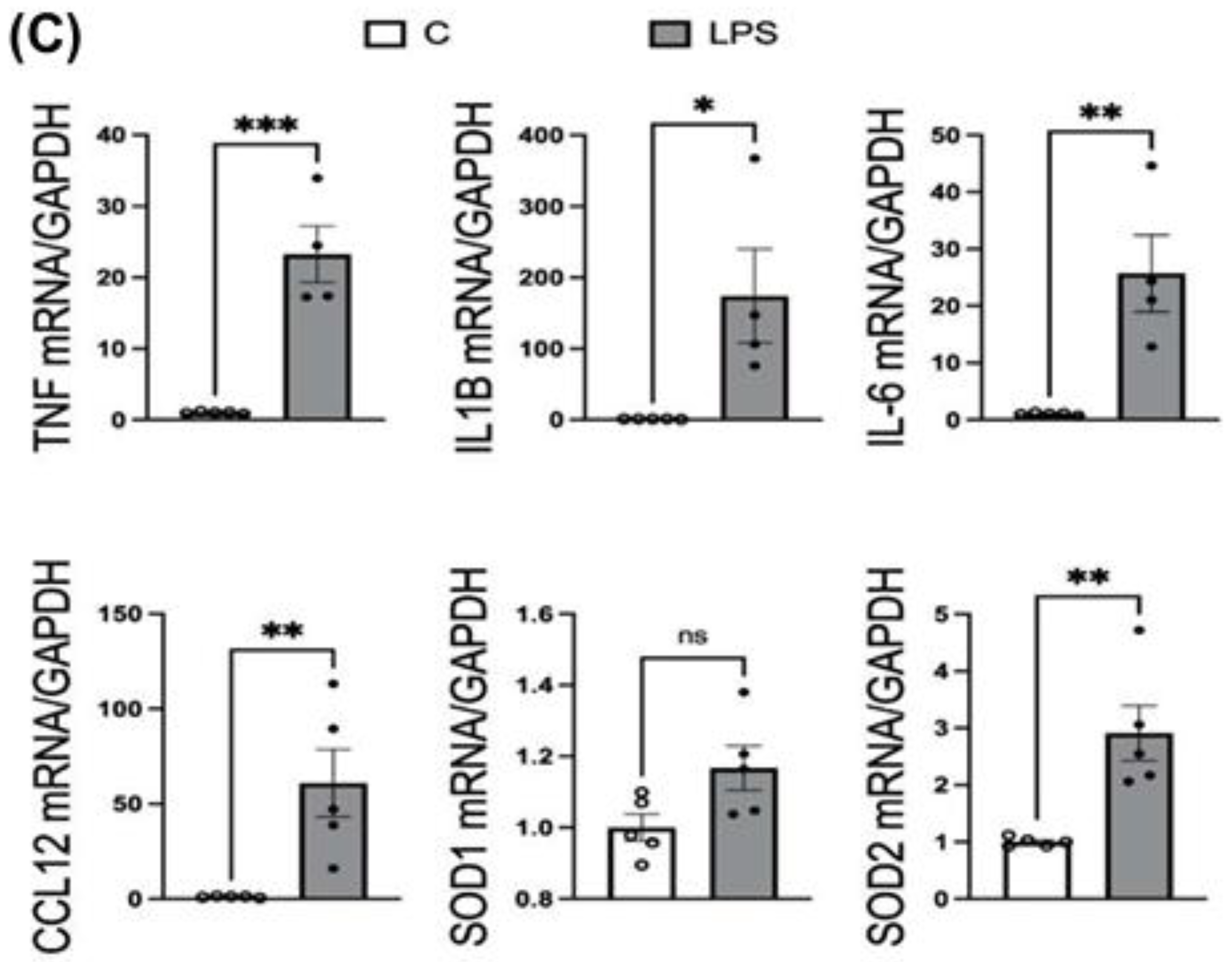

2.7.3. Real-Time PCR for mRNA Expression Analysis

The mRNA expression of inflammatory mediators (TNFα, IL1B, IL6, CCL2, CCL5, CCL12), NAPDH oxidase subunit CYBA, and antioxidant enzymes (SOD1, SOD2) was measured in cortex and hippocampus tissues from both LPS-treated (neuroinflammatory model, ICV administration) and control (PBS-treated) rats via ICV injection. Hippocampus and cortex were lysed with lysis buffer provided within the RNeasy Mini kit, supplemented with mercaptoethanol. RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and real-time PCR were performed following the manufacturer’s protocol, as mentioned above. 200ng of RNA from each sample was reverse transcribed to synthesize cDNA, which was used as a template in real-time PCR. Primers purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific for assessing LPS-induced neuroinflammation and oxidative stress were listed here: TNFα (Rnn99999017_m1), IL1B (Rn00580432_m1), IL6 (Rn01410330_m1), CCL2 (Rn00580555_m1), CCL5 (Rn00579590_m1), CCL12 (Rn01464638_m1), NF-kB (Rn01399583_m1), CYBA (Rn00577357_m1), SOD1 (Rn00566938_m1), SOD2 (Rn00690588_g1), and housekeeping gene GAPDH (Rn01775763_g1) used as a control. Relative mRNA expression was calculated using the 2⁻ΔΔCt method, normalizing to GAPDH expression and comparing LPS-treated samples to untreated controls.

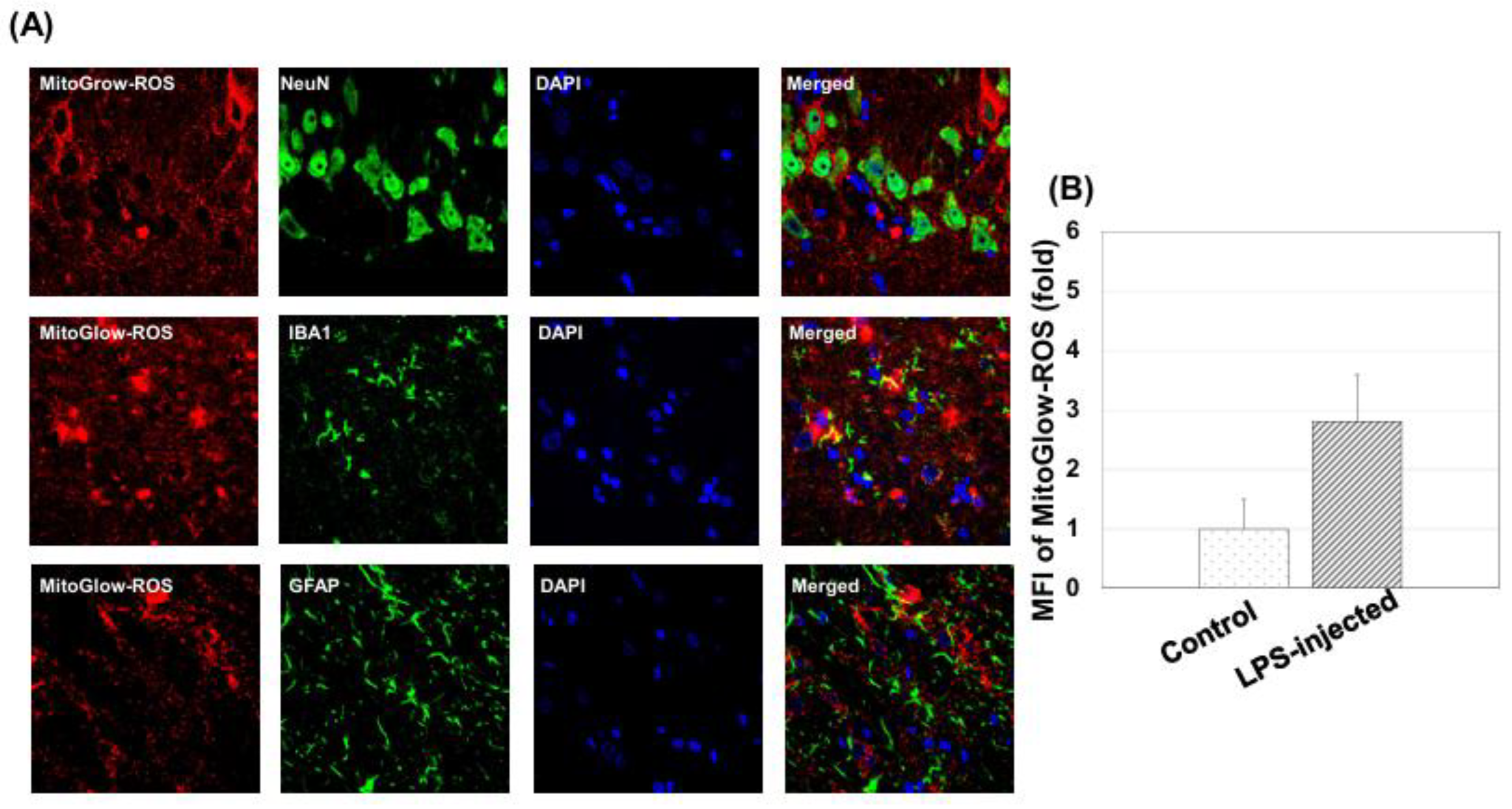

2.7.4. MitoGlow-ROS Probe Application and Mitochondrial ROS Measurement

The MitoGlow-ROS probe was prepared as a 1 mM stock solution in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and stored at -20°C in the dark to maintain stability. For vivo administration, the stock was diluted to a working concentration of 50 µM in sterile PBS, (pH 7.4) containing 5% DMSO to ensure solubility and prevent precipitation during injection. The final injection volume was 200 µL via tail vein, delivering a total dose of 10 nmol MitoGlow-ROS per rat. This dose was optimized based on prior cell-free and in vitro validations, which confirmed effective fluorescence detection with minimal cytotoxicity at this concentration

LPS (1mg/kg) was injected into the SD rats via intraperitoneal (IP) injection. 2 hours post LPS injection, rats received MitoGlow-ROS via intravenous (IV) injection. Anesthesia was induced with 5% isoflurane and the tail vein was accessed using a 26-gauge needle attached to a 1 mL syringe. The 200 µL of 50 µM MitoGlow-ROS solution was injected into the tail vein at a steady rate to precent vascular damage and ensure systemic distribution. Control rats (PBS-reated, LPS-free) received the same dose of MitoGlow-PBS via the identical route to establish baseline ROS levels. 6 hours post LPS injection, rats were euthanized and transcranially perfused with ice-cold PBS to clear blood, reducing autofluorescence during imaging, and then with 4% PFA to fix tissues. Brain tissues were then kept in 30% sucrose in 1 × PBS and used for cryo-section until the tissues descended to the container’s bottom. Embedded brain tissues in O.C.T. compound (Sakura Finetek, Dallas, TX, USA) were sectioned coronally at a thickness of 20 µm, and sections containing hippocampus and cortex were collected.

To assess neuronal, astrocytic, and microglial responses, immunostaining was performed for NeuN (neuronal marker), GFAP (astrocytic marker), and IBA1 (microglial marker). Sections were first washed three times with PBS to remove OCT. Non-specific binding was blocked by incubating sections in 5% horse serum in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. Primary antibodies were diluted in blocking solution and applied overnight at 4°C: rabbit anti-NeuN (1:300 dilution) for neurons, mouseanti-GFAP (1:300 dilution) for astrocytes, and rabbit anti-IBA1 (1:500 dilution) for microglia. The following day, sections were washed three times with PBS (5 minutes each) and incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark: Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:500) for NeuN and IBA1, and Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-mouse IgG for GFAP. Sections were then washed three times with PBS (5 minutes each) and mounted in Vectorshield (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, USA). Sections were stored at 4°C in the dark until imaging, and fluorescent images were captured using confocal microscopy (Olympus FV1000) with a 60× objective.

MitoGlow-ROS fluorescence was detected using excitation at 560 nm and emission at 588 nm. Alexa Fluor 488 (NeuN, GFAP and IBA1) was excited at 488 nm and emitted at 525 nm, and DAPI at 350 nm excitation and 461 nm emission. For each tissue section, 20 fields of view were imaged to ensure representative sampling, with laser intensity and gain settings kept constant across all samples for quantitative comparison.

Images were analyzed using ImageJ software. For ROS measurement, regions of interest (ROIs) were defined around DAPI-labeled nuclei to identify individual cells, ensuring cell-specific fluorescence measurements. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of MitoGlow-ROS was quantified within each ROI, with background fluorescence subtracted using a region devoid of cells in the same image. MFI values were normalized to the number of cells per field to account for variability in cell density. The MFI for LPS-treated rats was expressed as a fold change relative to the control group, confirming a 4.1-fold increase in the hippocampus and a 2.8-fold increase in the cortex. For immunohistochemistry, fluorescence intensities of NeuN, GFAP, and IBA1 were quantified similarly, and cell counts were performed by counting DAPI-labeled nuclei co-localized with each marker. Three sections per animal were analyzed, with data from at least three rats per group, ensuring robust statistical analysis.

Statistical Analysis: To evaluate the significance of differences between experimental groups, a two-way unpaired Student’s t-test was employed. This statistical method was chosen to compare the means of two independent groups (e.g., LPS-treated vs. control) across multiple variables, such as mitochondrial ROS levels measured by the MitoGlow-ROS probe and mRNA expression levels of inflammatory mediators (TNFα, IL1B, IL6, CCL2, CCL5, CCL12) and antioxidant enzymes (CYBA, CYBB, SOD1, SOD2) in both in vitro primary neuronal cultures and in vivo cortex and hippocampus tissues from SD rats. The analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism software. Data was first assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test to ensure the appropriateness of the t test and one-way ANOVA test. Results are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) to reflect the variability within each group, with statistical significance denoted as *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, and ****P<0.0001, indicating increasing levels of confidence in the observed differences. Each experiment included at least three biological replicates, and technical replicates were averaged prior to analysis to enhance reliability.

4. Discussion

MitoGlow-ROS exhibited superior sensitivity and a wide dynamic range for detecting mitochondrial superoxide in a cell-free system. Its fluorescence intensity increased linearly (R² = 0.97) with superoxide production rates from 0 to 10 µM/min, achieving a 45-fold signal increase, compared to MitoSOX Red’s 14-fold increase before saturation at 5 µM/min. The LOD for MitoGlow-ROS was 0.05 µM/min, twice as sensitive as MitoSOX Red’s LOD of 0.1 µM/min. At 0.1 µM/min, MitoGlow-ROS produced a clear signal, while MitoSOX Red was at its LOD, confirming higher sensitivity. MitoGlow-ROS also showed greater reproducibility, with error bars of ±5% compared to ±7% for MitoSOX Red. Its TEMPO-based fluorescence activation ensured specificity for mtROS, avoiding non-specific oxidation issues observed with MitoSOX Red.

In PC12 cells treated with antimycin A (0–20 µM), a complex III inhibitor that induces superoxide production via electron transport chain disruption, MitoGlow-ROS fluorescence increased dose-dependently, showing a 5-fold increase at 20 µM (***P<0.001). The probe detected superoxide at 0.05 µM/min, surpassing its LOD at 1 µM antimycin A and outperforming MitoSOX Red (LOD 0.1 µM/min). Pre-treatment with 100 µM NAC reduced fluorescence by 80% at 10 µM antimycin A (###P<0.001), confirming superoxide specificity and minimal non-specific activation, unlike DCFH-DA [

40]. MitoGlow-ROS’s linear response up to 20 µM antimycin A overcame MitoSOX Red’s saturation at high ROS levels [

42].

MitoGlow-ROS’s sensitivity to low superoxide levels (0.05 µM/min) enables early detection of oxidative stress, critical for studying initial stages of stroke and neuroinflammation, where subtle mtROS changes trigger neuronal damage. The probe’s performance in PC12 cells supports its use in complex systems, such as primary neuronal cultures and in vivo LPS-treated SD rats. Its ability to detect a 1.2-fold superoxide increase at 0.1 µM antimycin A highlights its utility for capturing early mtROS changes in neuroinflammation, relevant to stroke progression [

56,

57,

58].

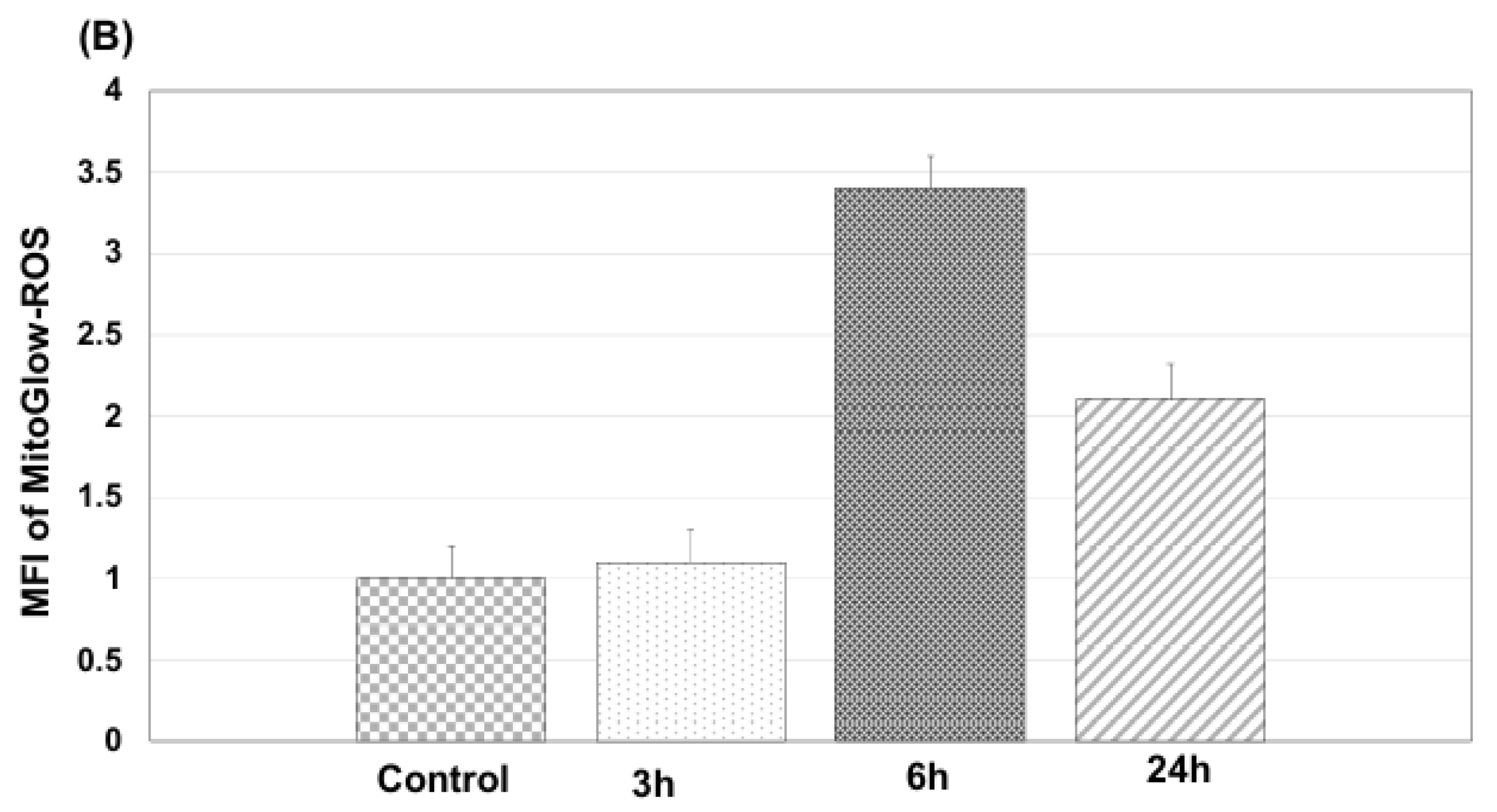

In primary neurons treated with 100 ng/mL LPS, MitoGlow-ROS, a sensitive fluorescent probe, captured time-dependent mtROS dynamics. Fluorescence intensity increased from 1.2-fold at 3 hours (p < 0.05) to a peak of 3.5-fold at 6 hours (p < 0.001), then declined to 2.0-fold by 24 hours (p < 0.01) compared to sham controls, as measured by confocal microscopy (n = 3 replicates). This pattern reflects LPS-induced toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) activation, which triggers rapid mtROS production through cytokine-mediated electron transport chain (ETC) dysfunction and NADPH oxidase activation [

59,

60,

61,

62]. The 3.5-fold peak at 6 hours aligns with reported superoxide surges in LPS-stimulated neuronal cultures, driven by ETC complex I inhibition and NOX2 activity [

63,

64]. The decline by 24 hours suggests partial oxidative stress resolution, potentially due to upregulation of antioxidant enzymes (e.g., SOD2) or anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-10 [

65]. MitoGlow-ROS’s detection of a 1.2-fold increase at 3 hours, surpassing its limit of detection (LOD, ~0.1-fold), highlights its sensitivity to early mtROS changes, while its 3.5-fold peak quantification demonstrates a broader dynamic range than MitoSOX Red, overcoming issues like non-specific staining [

42].

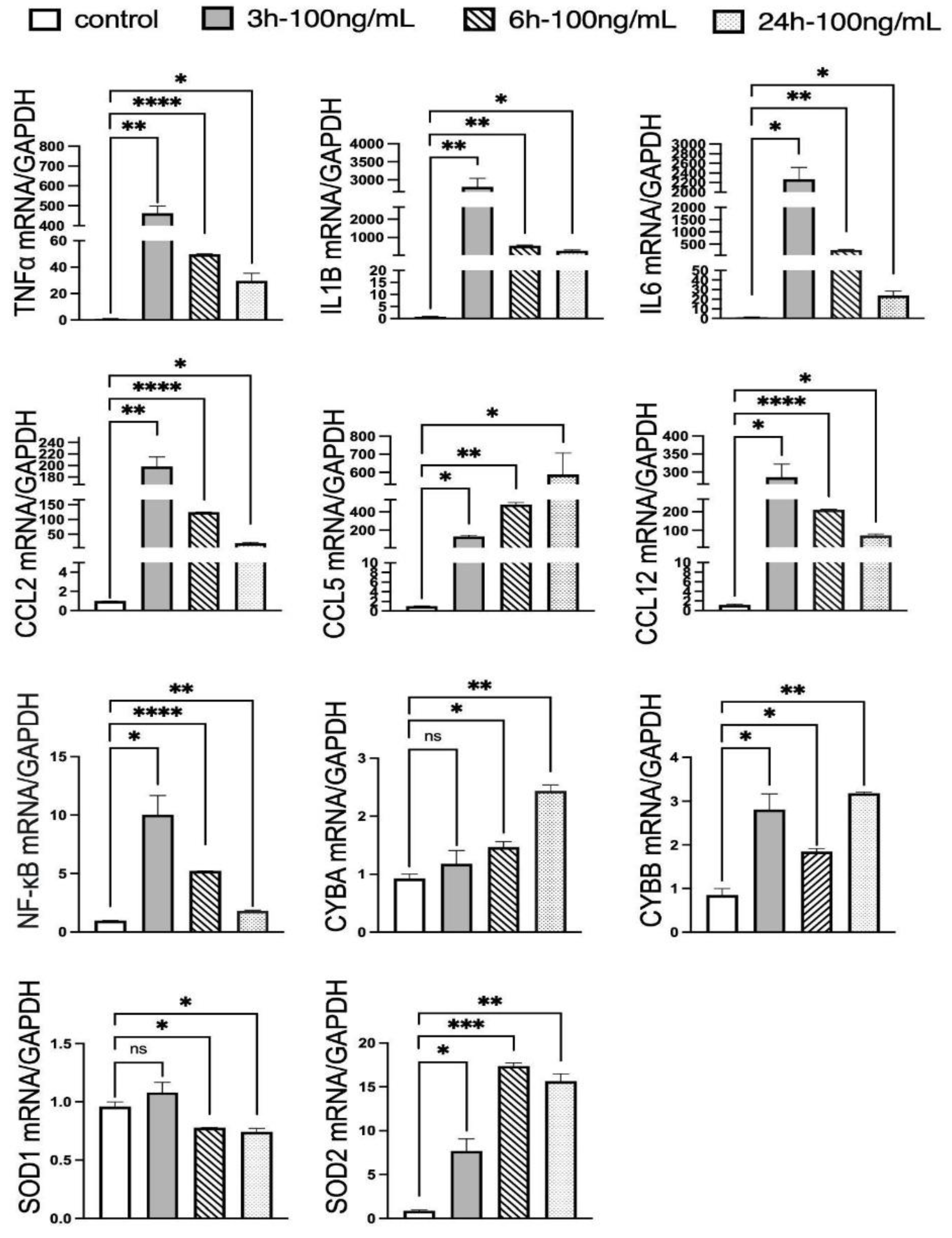

The time-dependent mRNA expression profiles of inflammatory mediators and antioxidant enzymes correlate with the mtROS dynamics observed via MitoGlow-ROS, providing a molecular basis for the observed oxidative stress. The maximum upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines at 3 hours precedes the peak in mtROS at 6 hours: TNFα (436-fold), IL1B (3513-fold), IL6 (1726-fold), CCL2 (196-fold), and CCL12 (240-fold). This suggests that earlier molecular alterations may contribute to the later rise in mtROS. These dramatic increases reflect a robust inflammatory response driven by LPS-induced TLR4 signaling, which activates NF-kB and promotes cytokine production [

59,

60,

61,

62]. Notably, the increase in IL6 and CCL5 suggests a strong chemotactic response, likely recruiting immune cells and amplifying neuroinflammation, consistent with LPS effects in neuronal cultures [

59,

60,

61,

62]. The decline in expression by 24 hours (e.g., TNFα to 28-fold, IL1B to 334-fold) indicates a resolution phase, possibly mediated by feedback mechanisms like IL-10 production, which downregulates pro-inflammatory responses [

66,

67].

NF-kB’s transient 10-fold increases at 3 hours, followed by a continued decline by 24 hours, aligns with its role as an early regulator of inflammatory gene expression via TLR4 pathways [

59,

60,

61,

62]. Its rapid decline suggests negative feedback mechanisms, such as IκB induction, which suppress prolonged NF-kB activation [

68,

69,

70]. This early NF-kB activation likely initiates the cytokine surge that peaks at 3 hours, correlating with the maximum ROS production observed via MitoGlow-ROS, as cytokines like TNFα and IL1B can enhance mitochondrial ROS by impairing ETC function [

71,

72].

The antioxidant enzyme expression further supports the ROS dynamics. SOD2, a mitochondrial superoxide dismutase, increased 19-fold at 6 hours, coinciding with the peak ROS level, reflecting a mitochondrial-specific response to neutralize superoxide and mitigate oxidative stress. The absence of SOD1 upregulation across all time points indicates that cytosolic antioxidant defenses are less responsive, consistent with the mitochondrial origin of LPS-induced ROS [

73,

74]. CYBA and CYBB, subunits of NADPH oxidase, showed selective upregulation at 6 and 3 hours (CYBA: 1.6-fold, CYBB: 3.3-fold), suggesting that NADPH oxidase contributes to ROS production in response to inflammation, although the persistent CYBA and CYBB elevation at 24 hours (2.6-fold and 3.7-fold) indicates a prolonged oxidative response. The correlation between SOD2 expression and MitoGlow-ROS fluorescence at 6 hours reinforces the probe’s specificity for mitochondrial ROS, as SOD2 directly responds to superoxide levels [

75,

76].

The LPS-induced neuroinflammation model in primary neuronal cells mimics the inflammatory and oxidative stress conditions observed in stroke, where ischemia-reperfusion and cytokine-driven inflammation elevate mitochondrial ROS, contributing to neuronal damage [

7]. The 3.4-fold ROS peak at 6 hours is comparable to the 3- to 5-fold increases reported in MCAO stroke models, validating the model’s relevance [

77,

78]. The decline to 2.1-fold by 24 hours mirrors the resolution phase in stroke, where anti-inflammatory mechanisms partially mitigate oxidative stress [

79]. The robust inflammatory response, particularly the increase in IL6 and CCL5, reflects the cytokine storm in stroke, which amplifies ROS production and neuronal injury [

80,

81]. MitoGlow-ROS’s ability to track these ROS dynamics positions it as a valuable tool for studying stroke-related oxidative stress, supporting the manuscript’s broader application in in vivo LPS models.

The LPS-treated primary neuronal cell experiments demonstrate that MitoGlow-ROS effectively tracks time-dependent mitochondrial ROS generation, peaking at 3.4-fold at 6 hours, with corresponding early upregulation of inflammatory (e.g., IL6) and oxidative stress markers (e.g., CYBB). These findings validate the probe’s sensitivity and specificity, supporting its application in stroke and neuroinflammatory models, and highlight its potential for studying ROS dynamics in neurodegenerative diseases, paving the way for targeted therapeutic strategies.

The results from the LPS-induced neuroinflammation study in SD rats provide critical insights into the regional differences in mitochondrial ROS generation and the associated inflammatory and oxidative stress responses in the cortex and hippocampus, as assessed by the MitoGlow-ROS probe and real-time PCR. These findings advance the manuscript’s objective of validating MitoGlow-ROS as a tool for monitoring mitochondrial ROS in neuroinflammatory models relevant to stroke and neurodegenerative diseases, offering valuable implications for understanding regional vulnerabilities and therapeutic strategies.

The MitoGlow-ROS probe revealed a 4.1-fold increase in mtROS in the hippocampus compared to a 2.8-fold increase in the cortex of LPS-treated rats, underscoring the hippocampus’s greater susceptibility to oxidative stress [

82,

83]. This regional disparity is driven by the hippocampus’s higher metabolic demand and mitochondrial density, which amplifies mtROS production during neuroinflammation, coupled with its limited antioxidant capacity [

7]. The hippocampus’s critical role in memory and learning makes it particularly vulnerable to mtROS-induced synaptic plasticity impairments, contributing to cognitive deficits in conditions like stroke and AD [

84]. In contrast, the cortex, involved in higher-order functions such as decision-making, exhibits lower mtROS increases, likely due to reduced metabolic activity, diverse neuronal populations, and potentially stronger antioxidant defenses [

12,

85,

86]. Additional factors, including the hippocampus’s denser microvascular network, heightened sensitivity to pro-inflammatory cytokines, and susceptibility to excitotoxicity, further exacerbate its vulnerability compared to the cortex [

7,

83]. These findings highlight the MitoGlow-ROS probe’s utility in detecting region-specific mtROS dynamics, supporting its application in neuroinflammatory models and guiding targeted therapeutic strategies, such as antioxidants, to mitigate hippocampal damage in diseases like stroke and AD.

The mRNA expression data strongly correlates with the ROS increases, providing molecular validation of MitoGlow-ROS’s performance. In the hippocampus, the 4.1-fold ROS increase is mirrored by significant upregulation of inflammatory mediators, with TNFα (45-fold), IL1B (647-fold), IL6 (185-fold), CCL2 (1329-fold), CCL5 (48-fold), and CCL12 (254-fold) all showing robust increases. The 48-fold surge in CCL5, in particular, indicates a potent chemotactic response, likely recruiting immune cells and amplifying neuroinflammation, consistent with LPS-induced effects in neuronal models [

87]. In the cortex, the 2.8-fold ROS increase corresponds to a 23-fold increase in TNFα, 174-fold in IL1B, 26-fold in IL6, and 61-fold in CCL12, reflecting a strong inflammatory response driven by LPS via TLR4 signaling [

88]. The higher increase in the pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines the hippocampus compared to the cortex aligns with the greater ROS elevation, suggesting that inflammation-driven ROS production is more pronounced in this region [

12,

85,

86].

The inflammatory response’s role in driving ROS production is further supported by the timing of cytokine expression, which peaks at 3 hours prior to ROS at 6 hours in parallel LPS-treated neuronal cultures [

87,

89,

90]. Cytokines like TNFα and IL1B can impair mitochondrial function by increasing ETC activity, leading to electron leakage and superoxide production, a mechanism consistent with the observed ROS increases [

91,

92,

93]. The correlation between ROS and inflammatory markers validates MitoGlow-ROS’s ability to reflect inflammation-driven oxidative stress, reinforcing its utility in neuroinflammatory models.

The antioxidant enzyme expression profiles provide additional validation of the MitoGlow-ROS data. In the hippocampus, the 2.6-fold increase in SOD2 mRNA expression corresponds closely to the 4.1-fold ROS increase, reflecting a mitochondrial-specific response to neutralize superoxide [

94,

95]. In the cortex, the 2.9-fold SOD2 increase aligns with the 2.8-fold ROS elevation, further confirming the probe’s accuracy. SOD2, a mitochondrial superoxide dismutase, directly responds to elevated superoxide levels, and its upregulation indicates a compensatory mechanism to mitigate oxidative damage [

94,

95]. The slightly higher SOD2 fold increase in the cortex despite a lower ROS elevation may reflect regional differences in antioxidant capacity, with the cortex potentially having a more robust response to oxidative stress [

76,

96].

The lack of change in SOD1 in both regions and CYBA in the hippocampus suggests that the ROS detected by MitoGlow-ROS is primarily mitochondrial, as cytosolic antioxidant defenses (SOD1) and NADPH oxidase (CYBA) play a minimal role in this context. However, the hippocampal CYBA expression remained unchanged, while in the cortex, the 5-fold CCL12 increase may indirectly enhance NADPH oxidase activity, contributing to the sustained oxidative response. These findings highlight MitoGlow-ROS’s specificity for mitochondrial ROS, distinguishing it from probes like DCFH-DA, which cannot isolate mitochondrial signals [

41].

The LPS-induced neuroinflammation model in SD rats mimics the oxidative and inflammatory stress observed in stroke, where ischemia-reperfusion elevates mitochondrial ROS, contributing to neuronal damage and inflammation [

8]. The 4.1-fold and 2.8-fold ROS increases in the hippocampus and cortex, respectively, are comparable to the significant increases of ROS observed in MCAO stroke models, validating the model’s relevance [

97]. The stronger hippocampal response mirrors clinical observations in stroke, where hippocampal vulnerability leads to cognitive deficits [

98,

99]. The cortical response, though less intense, suggests susceptibility to inflammation-driven damage, impacting functions like decision-making [

100]. MitoGlow-ROS’s ability to detect these regional differences supports its application in stroke research, particularly for studying therapeutic interventions targeting oxidative stress, such as mitochondrial antioxidants.

The LPS-induced neuroinflammation study in SD rats demonstrates that MitoGlow-ROS effectively detects region-specific mitochondrial ROS increases, with a 4.1-fold elevation in the hippocampus and 2.8-fold in the cortex, corroborated by corresponding mRNA expression changes (e.g., SOD2, inflammatory mediators). These findings validate the probe’s sensitivity and specificity, highlighting its utility for studying mitochondrial oxidative stress in stroke and neuroinflammatory models, and offering insights into regional vulnerabilities with implications for neurodegenerative disease research.