Submitted:

28 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Compounds and reagents

Preparation of microglial cultures

Measurement of cytokines

MicroRNA-seq

Bioinformatic analysis and statistics

Results

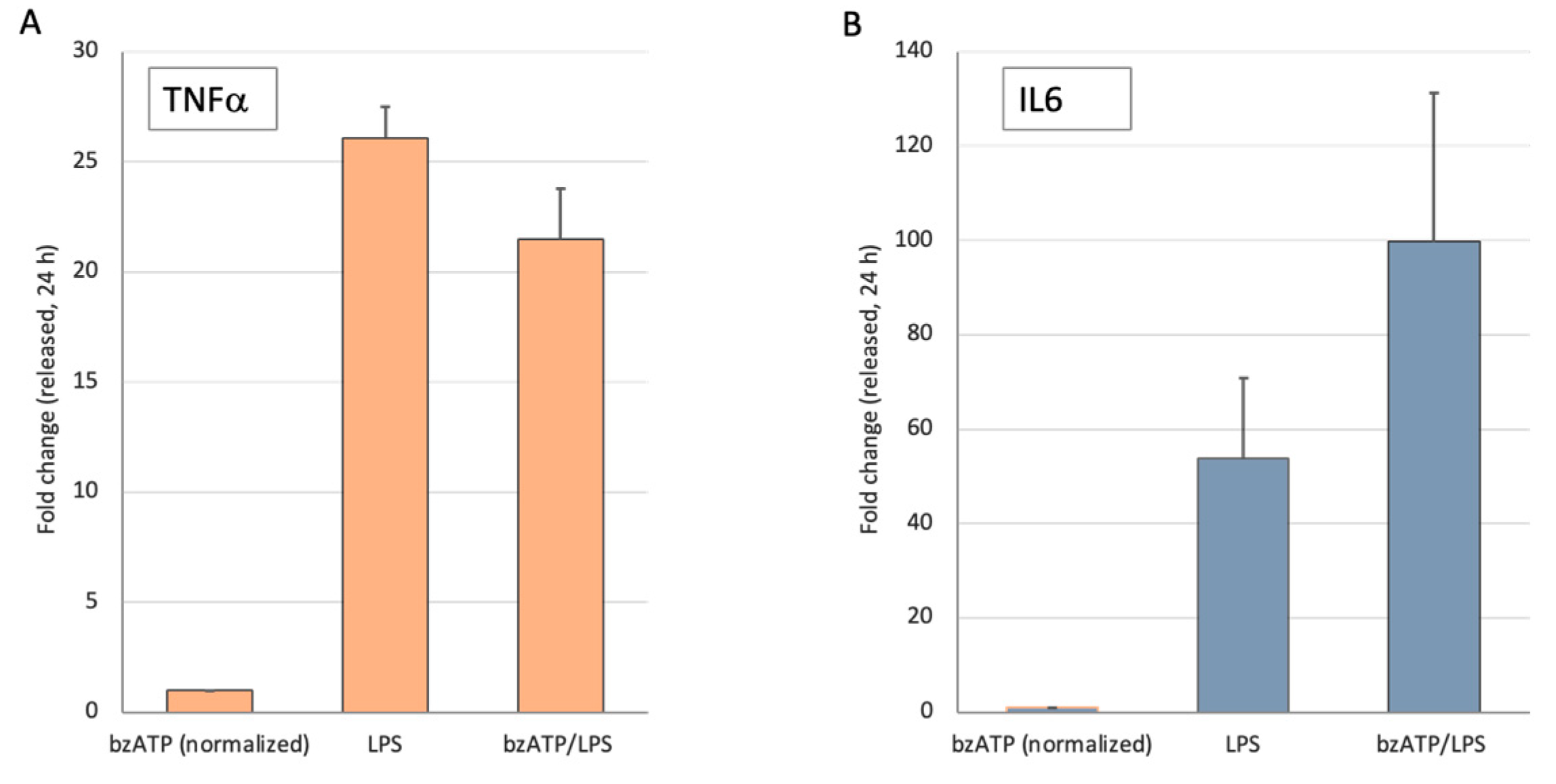

Release of pro-inflammatory cytokines in response of microglia to activation

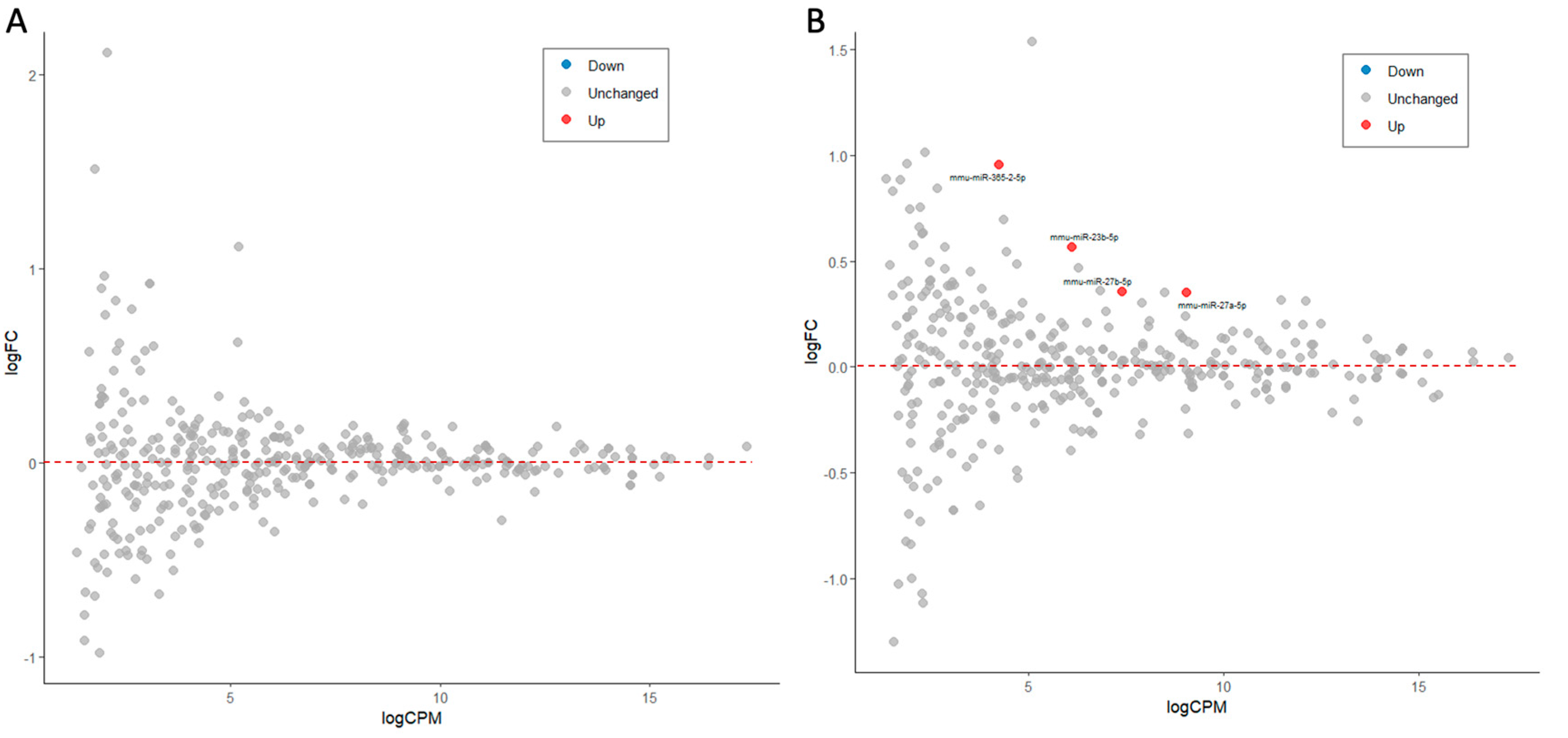

The alternation in miRNA profile in the presence of bzATP is minimal

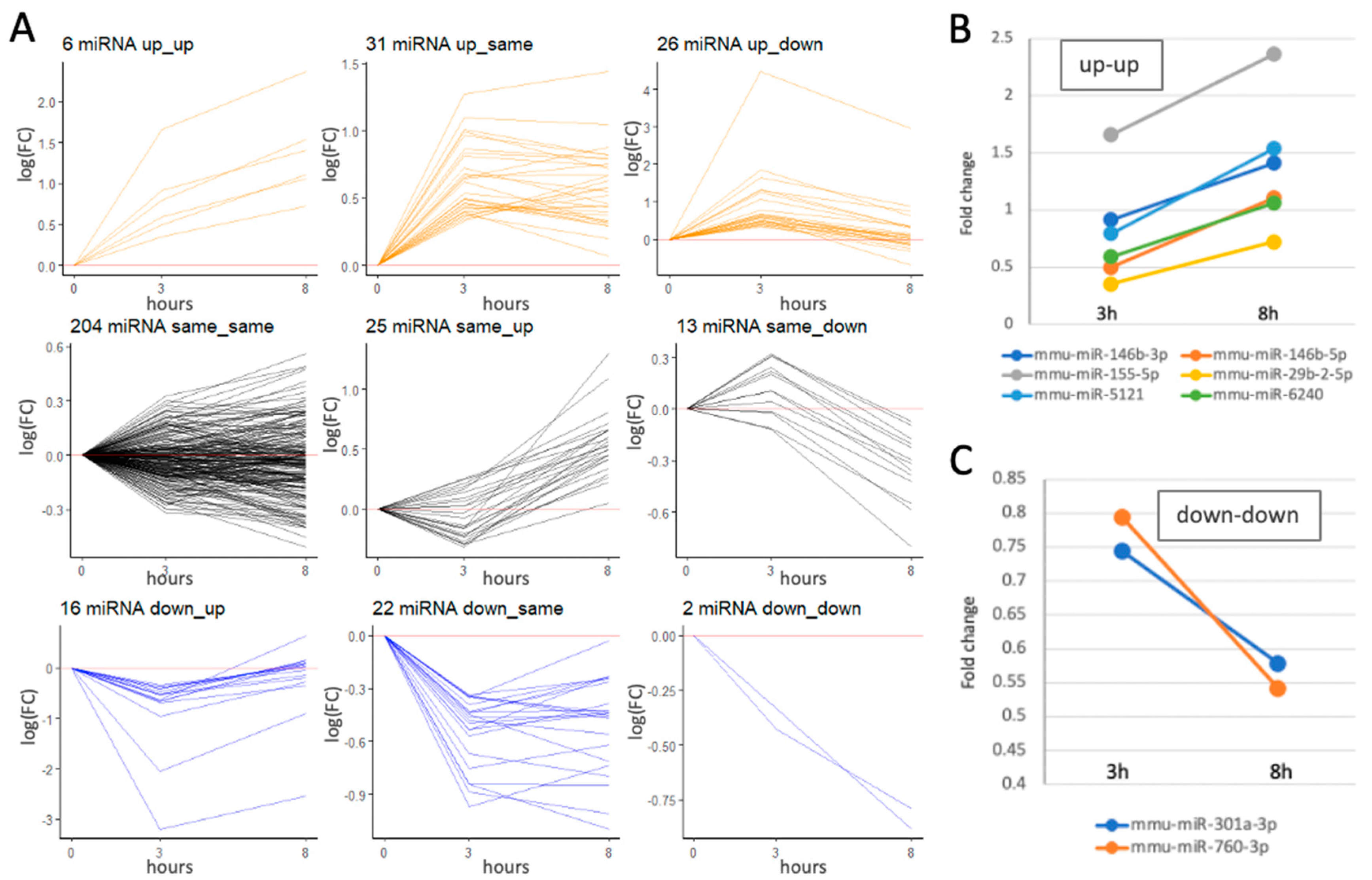

Temporal expression miRNA profiles following bzATP/LPS activation

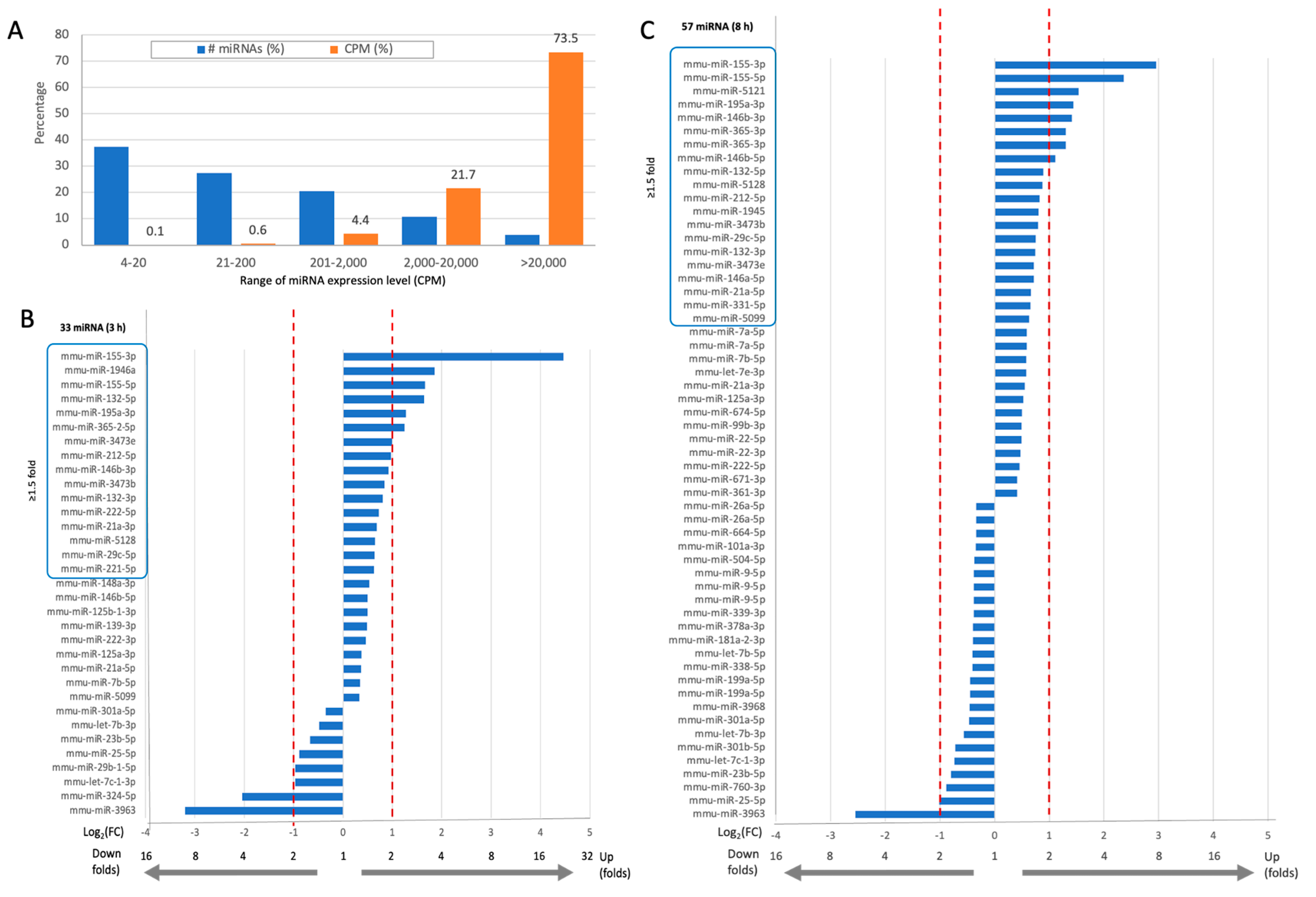

Activation of microglia by bzATP/LPS alters the miRNAs expression profile, including abundant miRNAs

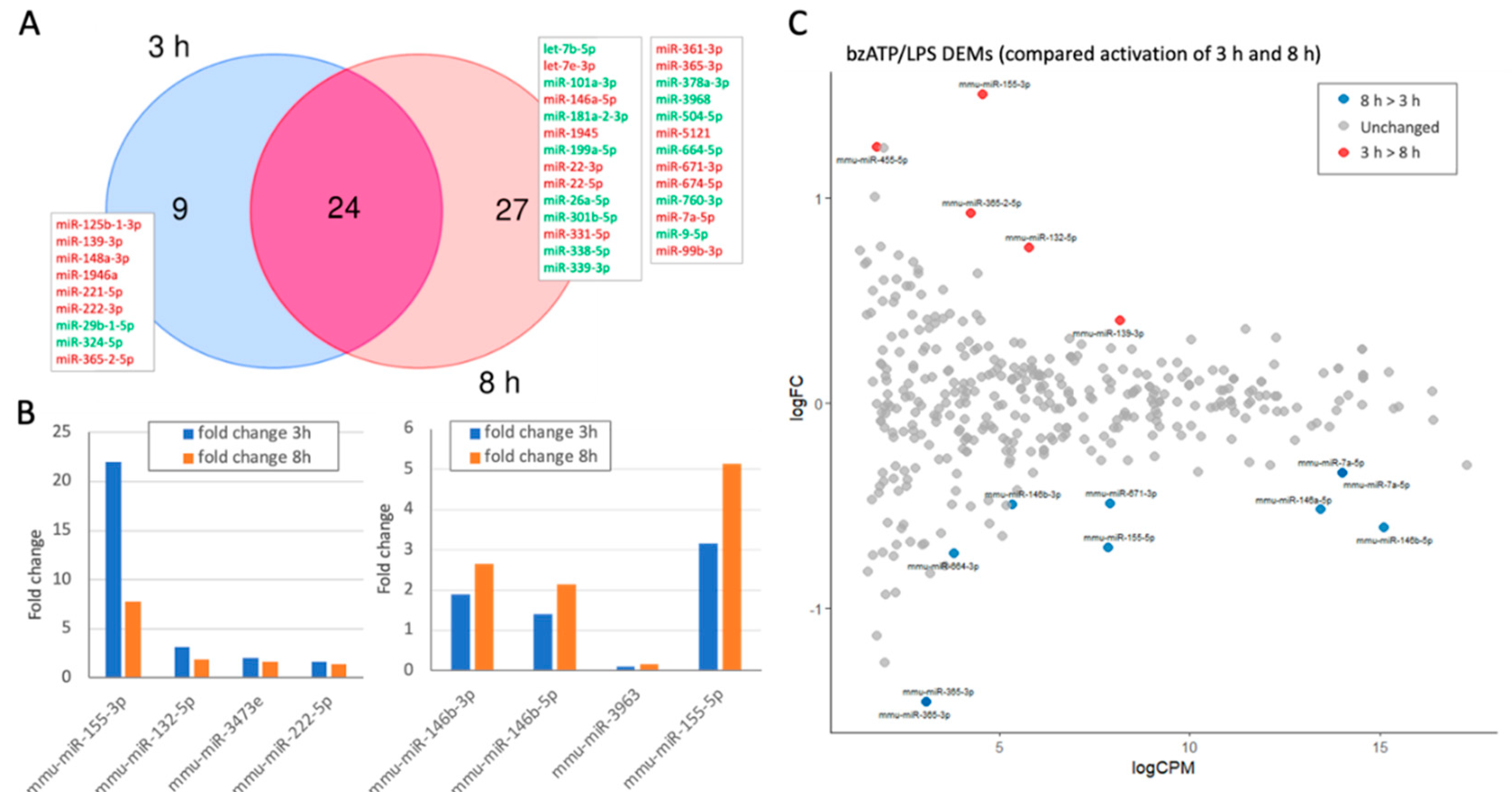

Dynamics of differentially expressed miRNAs (DEMs) by bzATP/LPS activation

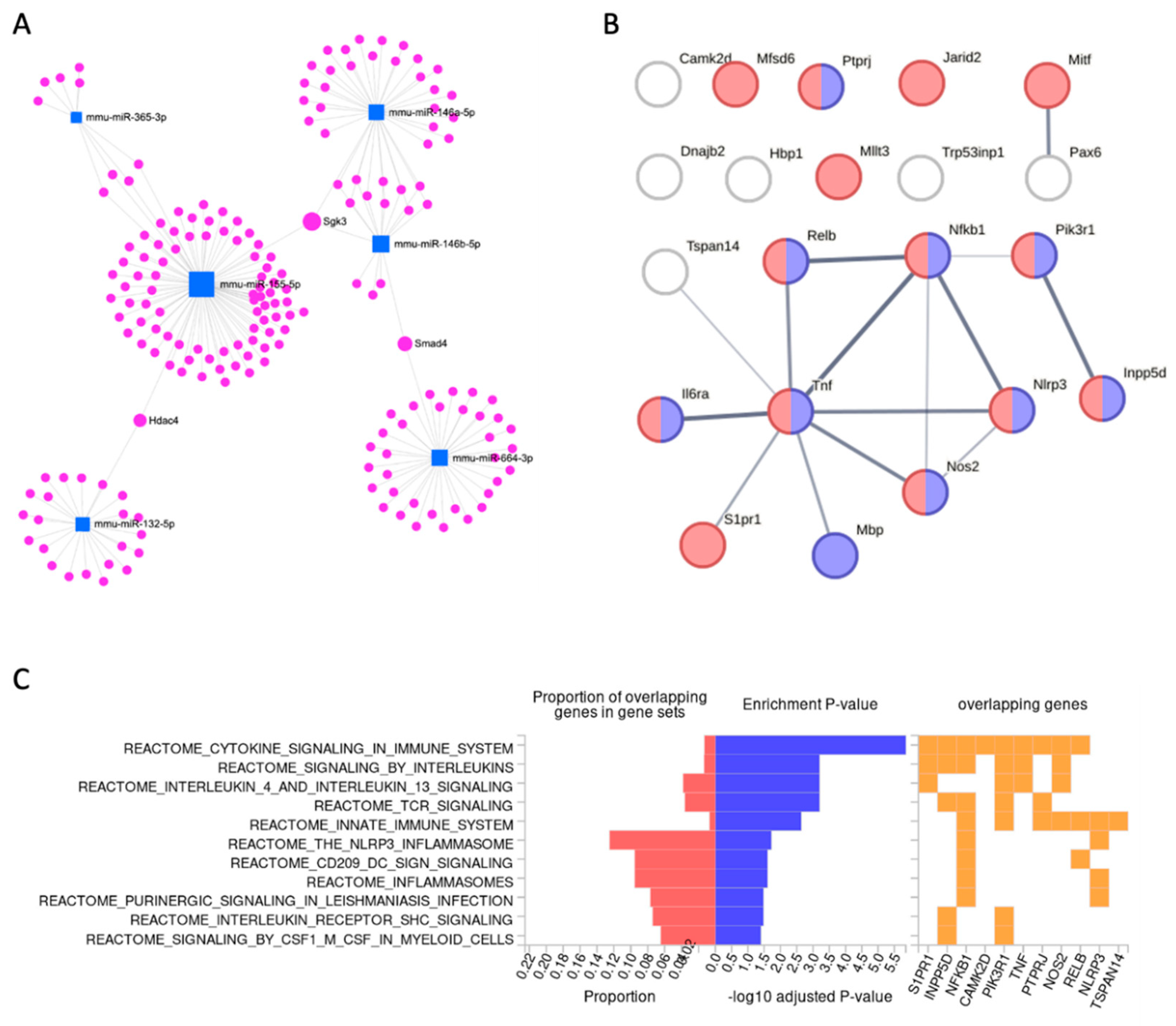

Temporal expression of a set of miRNAs is coupled with differentially expressed inflammatory genes

Ladostigil induced miRNAs that may serve as mediators in suppressing inflammation

Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability

Acknowledgment

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| BzATP | 2'-3'-O-(4-benzoyl benzoyl) adenosine 5'-triphosphate |

| DEG | Differentially expressed genes |

| DEM | Differentially expressed miRNAs |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium |

| FC | Fold change |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| GO | Gene ontology |

| h | Hours |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| N.T. | Not treated |

| RNAseq | RNA sequencing |

| TMM | Trimmed Mean of M-values normalization of RNA |

References

- Thakur, S.; Dhapola, R.; Sarma, P.; Medhi, B.; Reddy, D. H. , Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: current progress in molecular signaling and therapeutics. Inflammation 2023, 46, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Voet, S.; Srinivasan, S.; Lamkanfi, M.; van Loo, G. , Inflammasomes in neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases. EMBO molecular medicine 2019, 11, e10248. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Xiao, D.; Mao, Q.; Xia, H. , Role of neuroinflammation in neurodegeneration development. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2023, 8, 267. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, F.; Edison, P. , Neuroinflammation and microglial activation in Alzheimer disease: where do we go from here? Nature Reviews Neurology 2021, 17, 157–172. [Google Scholar]

- Von Bernhardi, R.; Eugenín-von Bernhardi, L.; Eugenín, J. , Microglial cell dysregulation in brain aging and neurodegeneration. Frontiers in aging neuroscience 2015, 7, 124. [Google Scholar]

- Raffaele, S.; Lombardi, M.; Verderio, C.; Fumagalli, M. , TNF production and release from microglia via extracellular vesicles: impact on brain functions. Cells 2020, 9, 2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, L.; Paolicelli, R. C. , Microglia-mediated synapse loss in Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Neuroscience 2018, 38, 2911–2919. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, Z.; Hu, H.; Zhao, M.; Sun, L. , Microglia in Alzheimer’s disease: a target for therapeutic intervention. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2021, 15, 749587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoham, S.; Linial, M.; Weinstock, M. , Age-induced spatial memory deficits in rats are correlated with specific brain region alterations in microglial morphology and gene expression. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology 2019, 14, 251–262. [Google Scholar]

- Colonna, M.; Butovsky, O. , Microglia Function in the Central Nervous System During Health and Neurodegeneration. Annu Rev Immunol 2017, 35, 441–468. [Google Scholar]

- Butovsky, O.; Jedrychowski, M. P.; Moore, C. S.; Cialic, R.; Lanser, A. J.; Gabriely, G.; Koeglsperger, T.; Dake, B.; Wu, P. M.; Doykan, C. E.; Fanek, Z.; Liu, L.; Chen, Z.; Rothstein, J. D.; Ransohoff, R. M.; Gygi, S. P.; Antel, J. P.; Weiner, H. L. , Identification of a unique TGF-beta-dependent molecular and functional signature in microglia. Nat Neurosci 2014, 17, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemonnot, A.-L.; Hua, J.; Ulmann, L.; Hirbec, H. , Microglia in Alzheimer disease: well-known targets and new opportunities. Frontiers in aging neuroscience 2019, 11, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghraiybah, N. F.; Wang, J.; Alkhalifa, A. E.; Roberts, A. B.; Raj, R.; Yang, E.; Kaddoumi, A. , Glial Cell-Mediated Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potru, P. S.; Vidovic, N.; Wiemann, S.; Russ, T.; Trautmann, M.; Spittau, B. , A Custom Panel for Profiling Microglia Gene Expression. Cells 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohar, K.; Lezmi, E.; Reichert, F.; Eliyahu, T.; Rotshenker, S.; Weinstock, M.; Linial, M. , Coordinated Transcriptional Waves Define the Inflammatory Response of Primary Microglial Culture. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linial, M.; Stern, A.; Weinstock, M. , Effect of ladostigil treatment of aging rats on gene expression in four brain areas associated with regulation of memory. Neuropharmacology 2020, 177, 108229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, F.; Zohar, K.; Lezmi, E.; Eliyahu, T.; Rotshenker, S.; Linial, M.; Weinstock, M. , Ladostigil Reduces the Adenoside Triphosphate/Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Secretion of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines from Microglia and Modulate-Immune Regulators, TNFAIP3, and EGR1. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Yao, X.; Taylor, N.; Bai, Y.; Lovenberg, T.; Bhattacharya, A. , RNA sequencing analysis reveals quiescent microglia isolation methods from postnatal mouse brains and limitations of BV2 cells. J Neuroinflammation 2018, 15, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thounaojam, M. C.; Kaushik, D. K.; Basu, A. , MicroRNAs in the brain: it's regulatory role in neuroinflammation. Mol Neurobiol 2013, 47, 1034–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.; Magdy, R. , MicroRNAs in central nervous system disorders: current advances in pathogenesis and treatment. The Egyptian Journal of Neurology, Psychiatry and Neurosurgery 2021, 57, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Hong, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, P.; Korner, H.; Tu, J.; Wei, W. , MicroRNAs in Microglia: How do MicroRNAs Affect Activation, Inflammation, Polarization of Microglia and Mediate the Interaction Between Microglia and Glioma? Front Mol Neurosci 2019, 12, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, F.; Rotshenker, S. , Complement-receptor-3 and scavenger-receptor-AI/II mediated myelin phagocytosis in microglia and macrophages. Neurobiology of disease 2003, 12, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Gitik, M.; Liraz-Zaltsman, S.; Oldenborg, P.-A.; Reichert, F.; Rotshenker, S. , Myelin down-regulates myelin phagocytosis by microglia and macrophages through interactions between CD47 on myelin and SIRPα (signal regulatory protein-α) on phagocytes. Journal of neuroinflammation 2011, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C. A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T. R. , STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander, M. R.; Mackowiak, S. D.; Li, N.; Chen, W.; Rajewsky, N. , miRDeep2 accurately identifies known and hundreds of novel microRNA genes in seven animal clades. Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 40, 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, M. D.; McCarthy, D. J.; Smyth, G. K. , edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A. L.; Lyon, D.; Junge, A.; Wyder, S.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Simonovic, M.; Doncheva, N. T.; Morris, J. H.; Bork, P. , STRING v11: protein–protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic acids research 2019, 47, D607–D613. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, L.; Zhou, G.; Soufan, O.; Xia, J. , miRNet 2.0: network-based visual analytics for miRNA functional analysis and systems biology. Nucleic acids research 2020, 48, W244–W251. [Google Scholar]

- Sayed, M.; Park, J. W. , miRinGO: Prediction of biological processes indirectly targeted by human microRNAs. Non-coding RNA 2023, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Wang, Y.; Ling, Y.; Zhou, C.; Wang, H.; Teschendorff, A. E.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, H.; He, Y.; Zhang, G. , dbDEMC 3.0: functional exploration of differentially expressed miRNAs in cancers of human and model organisms. Genomics, Proteomics and Bioinformatics 2022, 20, 446–454. [Google Scholar]

- Mahlab-Aviv, S.; Linial, N.; Linial, M. , miRNA Combinatorics and its Role in Cell State Control—A Probabilistic Approach. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 2021, 8, 772852. [Google Scholar]

- Iwakawa, H. O.; Tomari, Y. , The Functions of MicroRNAs: mRNA Decay and Translational Repression. Trends Cell Biol 2015, 25, 651–665. [Google Scholar]

- Remenyi, J.; van den Bosch, M. W.; Palygin, O.; Mistry, R. B.; McKenzie, C.; Macdonald, A.; Hutvagner, G.; Arthur, J. S.; Frenguelli, B. G.; Pankratov, Y. , miR-132/212 knockout mice reveal roles for these miRNAs in regulating cortical synaptic transmission and plasticity. PLoS One 2013, 8, e62509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Lin, X.; Lin, X. , MiR-146a-5p Contributes to Microglial Polarization Transitions Associated With AGEs. Mol Neurobiol 2023, 60, 3020–3033. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, N. A.; Hyrlov, K. H.; Elkjaer, M. L.; Thygesen, E. K.; Wlodarczyk, A.; Elbaek, K. J.; Aboo, C.; Okarmus, J.; Benedikz, E.; Reynolds, R.; Hegedus, Z.; Stensballe, A.; Svenningsen, A. F.; Owens, T.; Illes, Z. , Absence of miRNA-146a Differentially Alters Microglia Function and Proteome. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 1110. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, M.; Jassal, B.; Stephan, R.; Milacic, M.; Rothfels, K.; Senff-Ribeiro, A.; Griss, J.; Sevilla, C.; Matthews, L.; Gong, C. , The reactome pathway knowledgebase 2022. Nucleic acids research 2022, 50, D687–D692. [Google Scholar]

- Zohar, K.; Lezmi, E.; Eliyahu, T.; Linial, M. , Ladostigil attenuates induced oxidative stress in human neuroblast-like SH-SY5Y cells. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, L. S.; Geffen, Y.; Rabinowitz, J.; Thomas, R. G.; Schmidt, R.; Ropele, S.; Weinstock, M.; Group, L. S. , Low-dose ladostigil for mild cognitive impairment: A phase 2 placebo-controlled clinical trial. Neurology 2019, 93, e1474–e1484. [Google Scholar]

- van Wijk, N.; Zohar, K.; Linial, M. , Challenging cellular homeostasis: Spatial and temporal regulation of miRNAs. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23, 16152. [Google Scholar]

- Reichholf, B.; Herzog, V. A.; Fasching, N.; Manzenreither, R. A.; Sowemimo, I.; Ameres, S. L. , Time-Resolved Small RNA Sequencing Unravels the Molecular Principles of MicroRNA Homeostasis. Mol Cell 2019, 75, 756–768.e7. [Google Scholar]

- D'Onofrio, N.; Prattichizzo, F.; Martino, E.; Anastasio, C.; Mele, L.; La Grotta, R.; Sardu, C.; Ceriello, A.; Marfella, R.; Paolisso, G.; Balestrieri, M. L. , MiR-27b attenuates mitochondrial oxidative stress and inflammation in endothelial cells. Redox Biol 2023, 62, 102681. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, C.; Bai, Y.; Wang, S. , Neuroinflammation in Parkinson's disease: focus on the relationship between miRNAs and microglia. Front Cell Neurosci 2024, 18, 1429977. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, X.; Zou, Y.; Li, S.; Qi, R.; Yu, H.; Li, J. , MALAT1 Mediates alpha-Synuclein Expression through miR-23b-3p to Induce Autophagic Impairment and the Inflammatory Response in Microglia to Promote Apoptosis in Dopaminergic Neuronal Cells. Mediators Inflamm 2023, 2023, 4477492. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, B.; Ao, Q.; Shi, J.; He, Z. , MicroRNA-23b alleviates neuroinflammation and brain injury in intracerebral hemorrhage by targeting inositol polyphosphate multikinase. Int Immunopharmacol 2019, 76, 105887. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Lu, F.; Xie, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zhao, T.; Tao, S.; Lai, Z.; Wei, N.; Yang, R.; Shao, Y.; He, J. , miR-23b Negatively Regulates Sepsis-Induced Inflammatory Responses by Targeting ADAM10 in Human THP-1 Monocytes. Mediators Inflamm 2019, 2019, 5306541. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Kawashima, N.; Han, P.; Sunada-Nara, K.; Yu, Z.; Tazawa, K.; Fujii, M.; Kieu, T. Q.; Okiji, T. , MicroRNA-27a-5p Downregulates Expression of Proinflammatory Cytokines in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Human Dental Pulp Cells via the NF-kappaB Signaling Pathway. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Kobeissy, P. H.; Deneve-Larrazet, C.; Marvaud, J. C.; Kansau, I. , MicroRNA miR-27a-5p Reduces Intestinal Inflammation Induced by Clostridioides difficile Flagella by Regulating the Nuclear Factor-kappaB Signaling Pathway. J Infect Dis 2025, 231, e38–e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Su, S.; Jiang, L.; Yu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, H.; Han, K.; Zhang, X. , Exosomal miR-27a-5p attenuates inflammation through Toll-like receptor 7 in foodborne Salmonella infections. Vet Microbiol 2025, 302, 110394. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, S.; Song, Z.; Wu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Gao, M.; Liu, F.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Y. , MicroRNA-27b Modulates Inflammatory Response and Apoptosis during Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection. J Immunol 2018, 200, 3506–3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thulasingam, S.; Massilamany, C.; Gangaplara, A.; Dai, H.; Yarbaeva, S.; Subramaniam, S.; Riethoven, J. J.; Eudy, J.; Lou, M.; Reddy, J. , miR-27b*, an oxidative stress-responsive microRNA modulates nuclear factor-kB pathway in RAW 264.7 cells. Mol Cell Biochem 2011, 352, 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, N.; Rasheed, Z.; Ramamurthy, S.; Anbazhagan, A. N.; Voss, F. R.; Haqqi, T. M. , MicroRNA-27b regulates the expression of matrix metalloproteinase 13 in human osteoarthritis chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum 2010, 62, 1361–1371. [Google Scholar]

- Deora, V.; Lee, J. D.; Albornoz, E. A.; McAlary, L.; Jagaraj, C. J.; Robertson, A. A. B.; Atkin, J. D.; Cooper, M. A.; Schroder, K.; Yerbury, J. J.; Gordon, R.; Woodruff, T. M. , The microglial NLRP3 inflammasome is activated by amyotrophic lateral sclerosis proteins. Glia 2020, 68, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, C.; Arisi, I.; D'Ambrosi, N.; Storti, A. E.; Brandi, R.; D'Onofrio, M.; Volonte, C. , Dysregulated microRNAs in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis microglia modulate genes linked to neuroinflammation. Cell Death Dis 2013, 4, e959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonski, K. A.; Gaudet, A. D.; Amici, S. A.; Popovich, P. G.; Guerau-de-Arellano, M. , Control of the Inflammatory Macrophage Transcriptional Signature by miR-155. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0159724. [Google Scholar]

- Zingale, V. D.; Gugliandolo, A.; Mazzon, E. , MiR-155: An Important Regulator of Neuroinflammation. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Meldolesi, J. , Exosomes and ectosomes in intercellular communication. Current Biology 2018, 28, R435–R444. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X. F.; Wu, N.; Wang, L.; Li, J. , Circulating microRNAs: a novel class of potential biomarkers for diagnosing and prognosing central nervous system diseases. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2013, 33, 601–613. [Google Scholar]

- Long, X.; Yao, X.; Jiang, Q.; Yang, Y.; He, X.; Tian, W.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, H. , Astrocyte-derived exosomes enriched with miR-873a-5p inhibit neuroinflammation via microglia phenotype modulation after traumatic brain injury. J Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 89. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, E. B.; Hochfelder, C. G.; Lamberty, B. G.; Meays, B. M.; Morsey, B. M.; Kelso, M. L.; Fox, H. S.; Yelamanchili, S. V. , Traumatic brain injury increases levels of miR-21 in extracellular vesicles: implications for neuroinflammation. FEBS Open Bio 2016, 6, 835–846. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. F.; Luh, F.; Ho, Y. S.; Yen, Y. , Exosomes: a review of biologic function, diagnostic and targeted therapy applications, and clinical trials. J Biomed Sci 2024, 31, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Chevillet, J. R.; Kang, Q.; Ruf, I. K.; Briggs, H. A.; Vojtech, L. N.; Hughes, S. M.; Cheng, H. H.; Arroyo, J. D.; Meredith, E. K.; Gallichotte, E. N.; Pogosova-Agadjanyan, E. L.; Morrissey, C.; Stirewalt, D. L.; Hladik, F.; Yu, E. Y.; Higano, C. S.; Tewari, M. , Quantitative and stoichiometric analysis of the microRNA content of exosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014, 111, 14888–14893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| miRNA | FDR | Fold Change | Ave. CPM | Trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mmu-miR-155-5p | 2.04E-15 | 5.14 | 231.0 | Up |

| mmu-miR-146b-5p | 3.29E-16 | 2.15 | 35,262.0 | Up |

| mmu-miR-146a-5p | 3.17E-07 | 1.64 | 11,147.5 | Up |

| mmu-miR-21a-5p | 3.06E-13 | 1.59 | 161,946.4 | Up |

| mmu-miR-5099 | 8.14E-07 | 1.55 | 4,425.2 | Up |

| mmu-miR-7a-5p | 7.51E-09 | 1.50 | 16,738.0 | Up |

| mmu-miR-125a-3p | 2.87E-06 | 1.44 | 106.7 | Up |

| mmu-miR-99b-3p | 3.54E-06 | 1.40 | 523.7 | Up |

| mmu-miR-22-5p | 1.27E-04 | 1.40 | 169.7 | Up |

| mmu-miR-22-3p | 9.06E-08 | 1.39 | 3,072.8 | Up |

| mmu-miR-222-5p | 1.90E-05 | 1.37 | 243.8 | Up |

| mmu-miR-671-3p | 5.08E-03 | 1.33 | 238.8 | Up |

| mmu-miR-361-3p | 6.20E-05 | 1.33 | 330.7 | Up |

| mmu-miR-26a-5p | 2.87E-06 | 0.79 | 15,464.0 | Down |

| mmu-miR-101a-3p | 2.07E-05 | 0.79 | 825.0 | Down |

| mmu-miR-504-5p | 9.77E-03 | 0.78 | 114.8 | Down |

| mmu-miR-9-5p | 2.87E-06 | 0.77 | 2,290.4 | Down |

| mmu-miR-378a-3p | 1.47E-07 | 0.76 | 4,776.9 | Down |

| mmu-let-7b-5p | 1.95E-03 | 0.76 | 4,927.1 | Down |

| mmu-miR-3968 | 7.01E-03 | 0.73 | 142.6 | Down |

| Validated target. | Gene name | miRNAa (E: 3h >8h) |

FDR T-DEG (3h-8h) |

DEG Ave. CPM |

FC T-DEG (3h>8h) |

FC DEG (8h to N.T.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camk2d | calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II, delta | miR-146a-5p | 1.2E-18 | 47.2 | 0.50 | 1.31 |

| Dnajb2 | DnaJ heat shock protein family (Hsp40) member B2 | E: miR-155-3p | 1.4E-15 | 16.0 | 2.17 | 1.90 |

| Hbp1 | high mobility group box transcription factor 1 | miR-155-5p | 3.2E-14 | 16.3 | 2.05 | 0.68 |

| Il6ra | interleukin 6 receptor, alpha | miR-155-5p | 8.2E-17 | 18.3 | 2.58 | 0.54 |

| Inpp5d | inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase D | miR-155-5p | 5.2E-25 | 178.1 | 2.20 | 1.04 |

| Jarid2 | jumonji, AT rich interactive domain 2 | miR-155-5p | 6.5E-21 | 35.0 | 0.42 | 2.29 |

| Mbp | myelin basic protein | miR-7a-5p | 4.7E-21 | 71.5 | 2.10 | 0.54 |

| Mfsd6 | major facilitator superfamily domain containing 6 | miR-155-5p miR-365-3p | 4.9E-22 | 116.0 | 2.06 | 1.35 |

| Mitf | melanogenesis associated transcription factor | E: miR-155-3p | 1.3E-28 | 354.5 | 0.34 | 1.05 |

| Mllt3 | myeloid/lymphoid or mixed-lineage leukemia; translocated to, 3 | miR-146a-5p miR-146b-5p | 2.9E-14 | 12.0 | 2.41 | 0.71 |

| Nfkb1 | nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells 1, p105 | miR-146b-5p | 3.6E-26 | 523.3 | 0.43 | 2.59 |

| Nlrp3 | NLR family, pyrin domain containing 3 | miR-7a-5p | 1.6E-29 | 1000.0 | 0.25 | 3.85 |

| Nos2 | nitric oxide synthase 2, inducible | miR-146a-5p | 6.0E-17 | 22.6 | 3.10 | 39.13 |

| Pax6 | paired box 6 | miR-7a-5p | 6.2E-14 | 12.6 | 2.53 | 0.50 |

| Pik3r1 | phosphoinositide-3-kinase regulatory subunit 1 | E: miR-132-5p | 1.2E-20 | 47.4 | 2.16 | 0.81 |

| Ptprj | protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, J | miR-155-5p | 1.0E-22 | 392.8 | 0.42 | 1.89 |

| Relb | avian reticuloendotheliosis viral (v-rel) oncogene related B | miR-146a-5p | 3.5E-26 | 56.2 | 0.34 | 1.10 |

| S1pr1 | sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 | miR-155-5p | 2.1E-15 | 10.9 | 4.13 | 0.30 |

| Tnf | tumor necrosis factor | E: miR-132-5p | 4.8E-28 | 5250.7 | 0.29 | 18.92 |

| Trp53inp1 | transformation related protein 53 inducible nuclear protein 1 | miR-155-5p | 1.1E-16 | 18.3 | 3.24 | 0.57 |

| Tspan14 | tetraspanin 14 | miR-155-5p | 9.2E-20 | 41.9 | 2.32 | 0.94 |

| miRNA | Activation /Condition | Cellular and Modela | Target gene/ pathwayb | Refrerence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-23b-5p | intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) | Rat brain | IPMK | [44] |

| Sepsis-Induced | Mouse | MMP/ ADAM10 | [45] | |

| miR-27a-5p | LPS activated | Human dental pulp cells (hDPCs) | TAB1/NF-κB | [46] |

| Clostridioides infection | Mouse Intestine | NF-κB signaling | [47] | |

| Salmonella infection | EVs, RAW264.7 cells | TLR7/ NF-κB | [48] | |

| miR-27b-5p | TNF alpha exposure | Human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) | Akt-FOXO1 | [41] |

| Mycobacterium Infection | RAW264.7 cells | NF-κB signaling | [49] | |

| Hydrogen peroxide induced | RAW264.7 cells | NF-κB signaling | [50] | |

| IL-1β-induced | Human osteoarthritis chondrocytes | MMP-13/NF-kB/ p38 | [51] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).