Submitted:

16 May 2025

Posted:

17 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

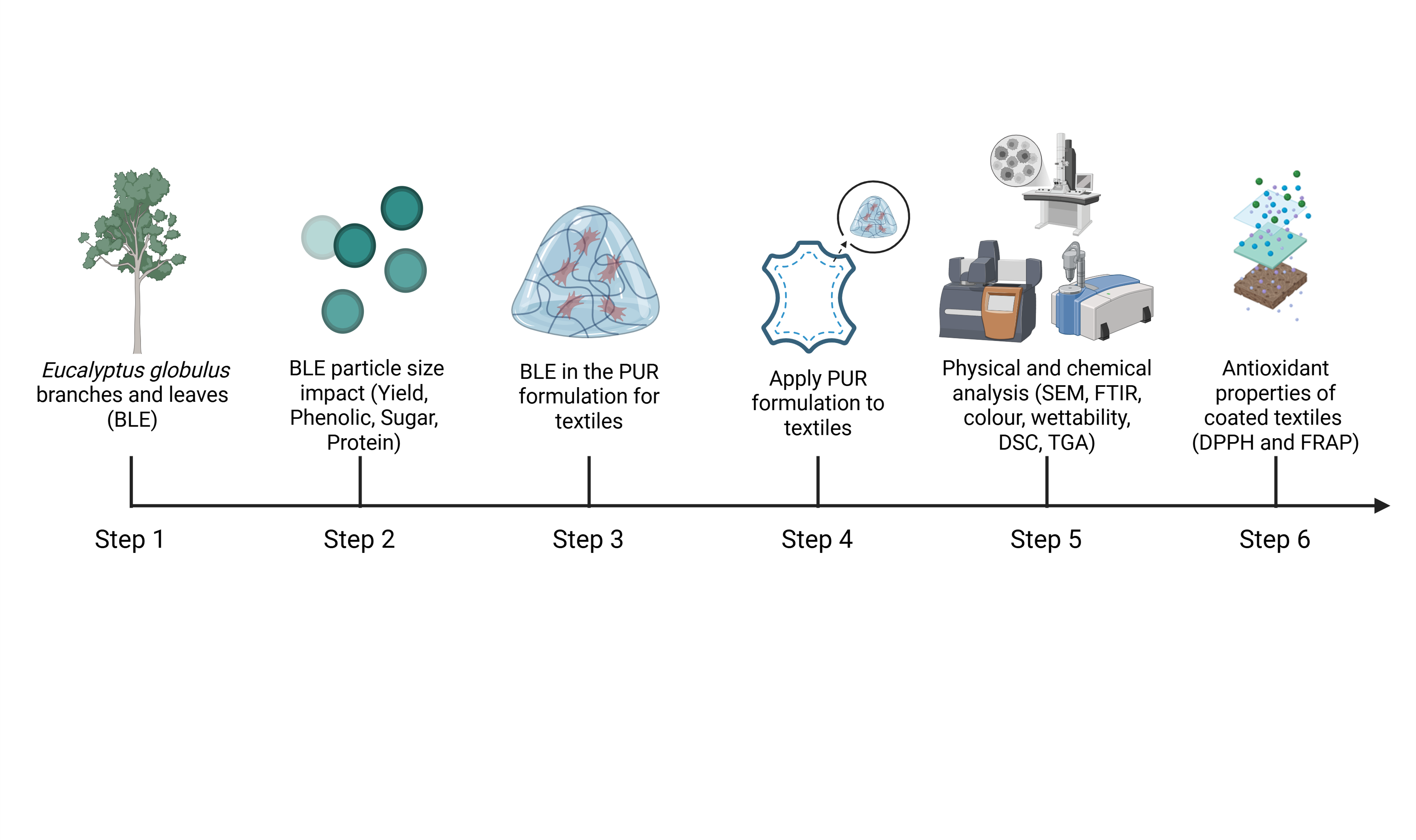

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Material

2.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Assay

2.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy

2.4. Chemical Characterization of BLE Particles

2.4.1. Phenol Content (Folin Ciocalteu)

2.4.2. Sugar Content (Anthrone Method)

2.4.3. Protein Content (Lowry Method)

2.4.4. Extraction Yield

2.5. Coating of Cotton Fabrics with BLE Particles

2.6. Coated Fabrics Characterisation

2.6.1. Colour and Color Fastness Evaluation

2.6.2. Surface Wettability

2.6.3. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

2.6.4. Simultaneous Thermal Analysis (STA)

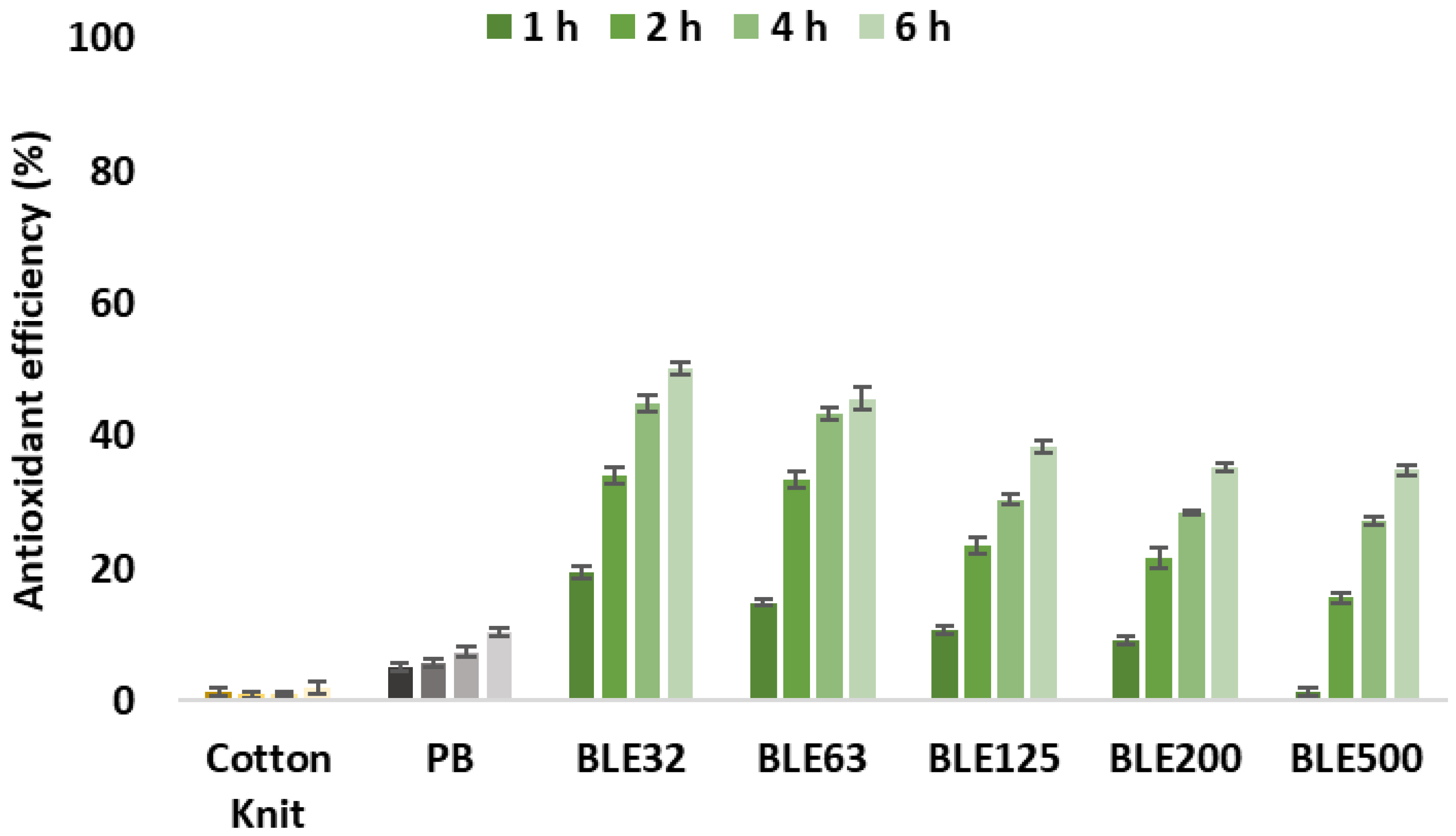

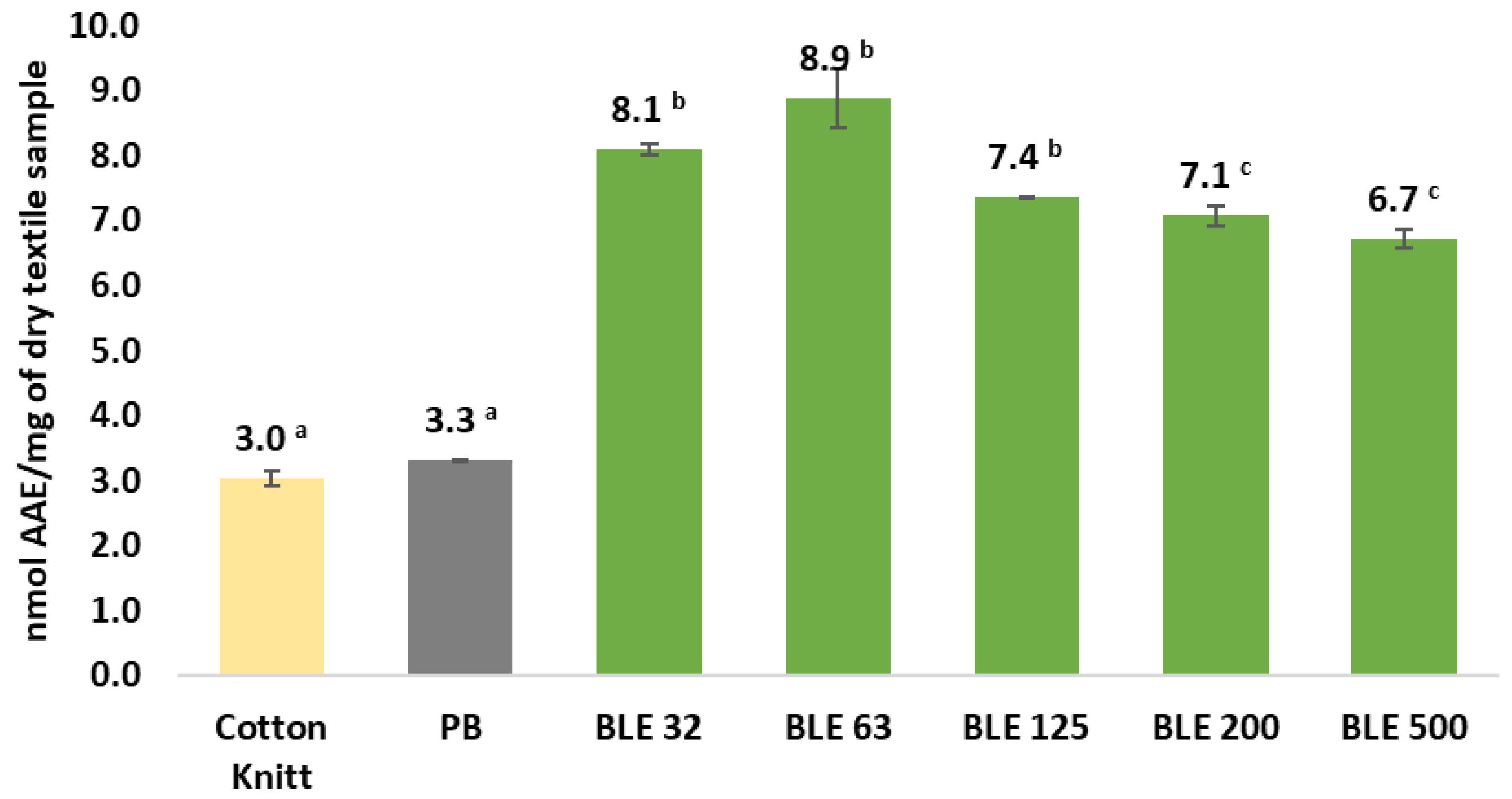

2.6.5. Evaluation of Antioxidant Capacity of the Fabrics

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

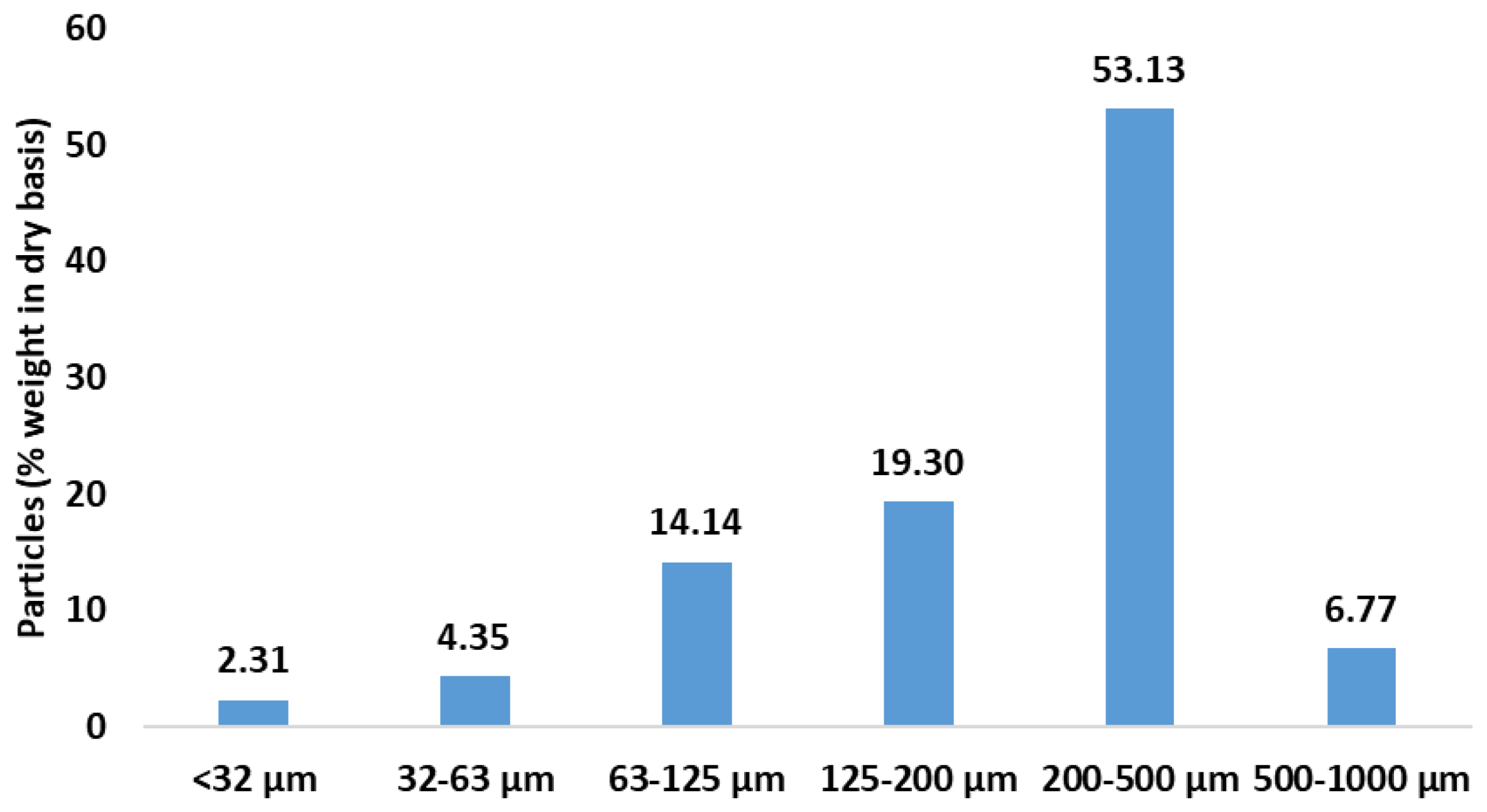

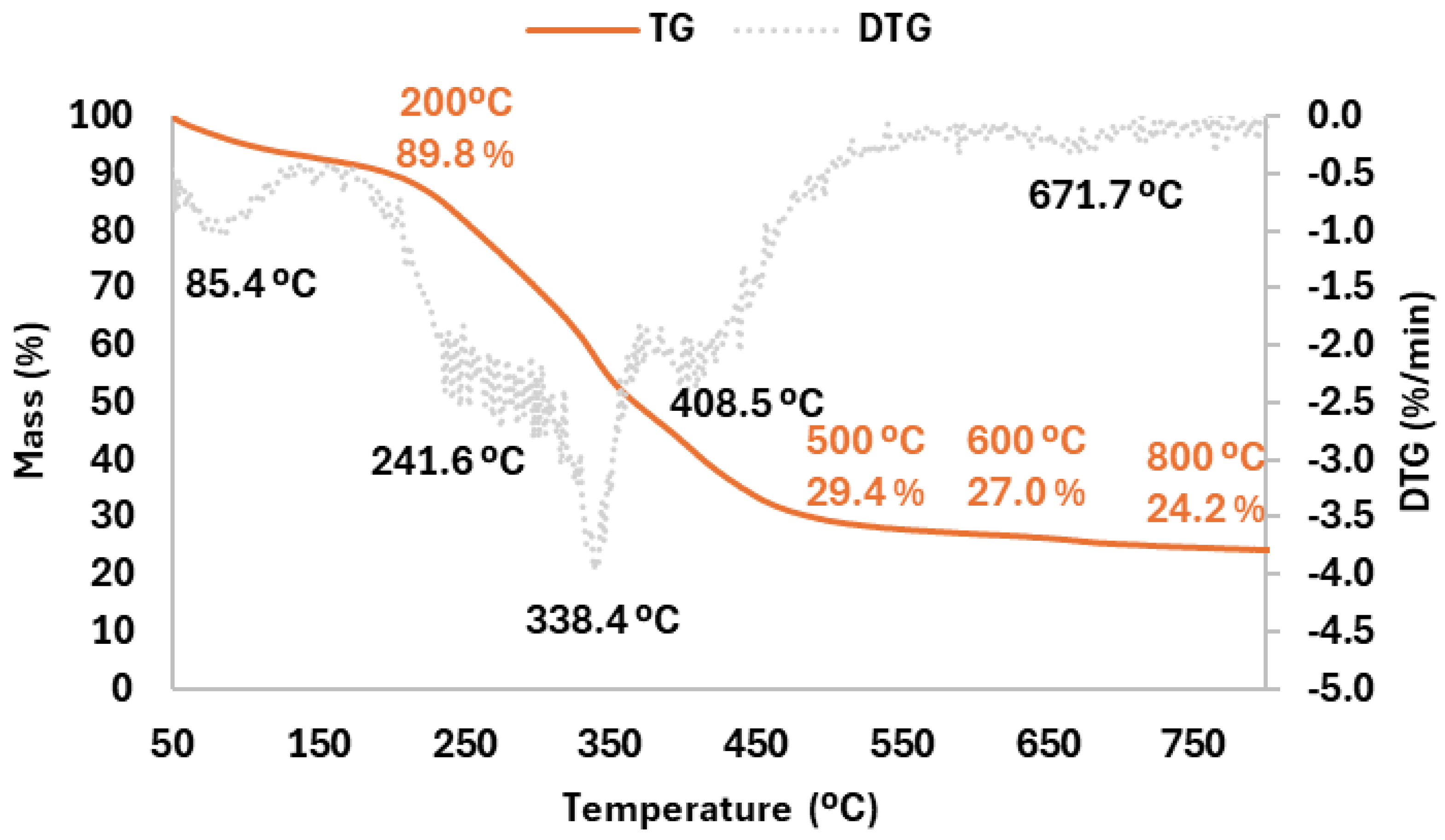

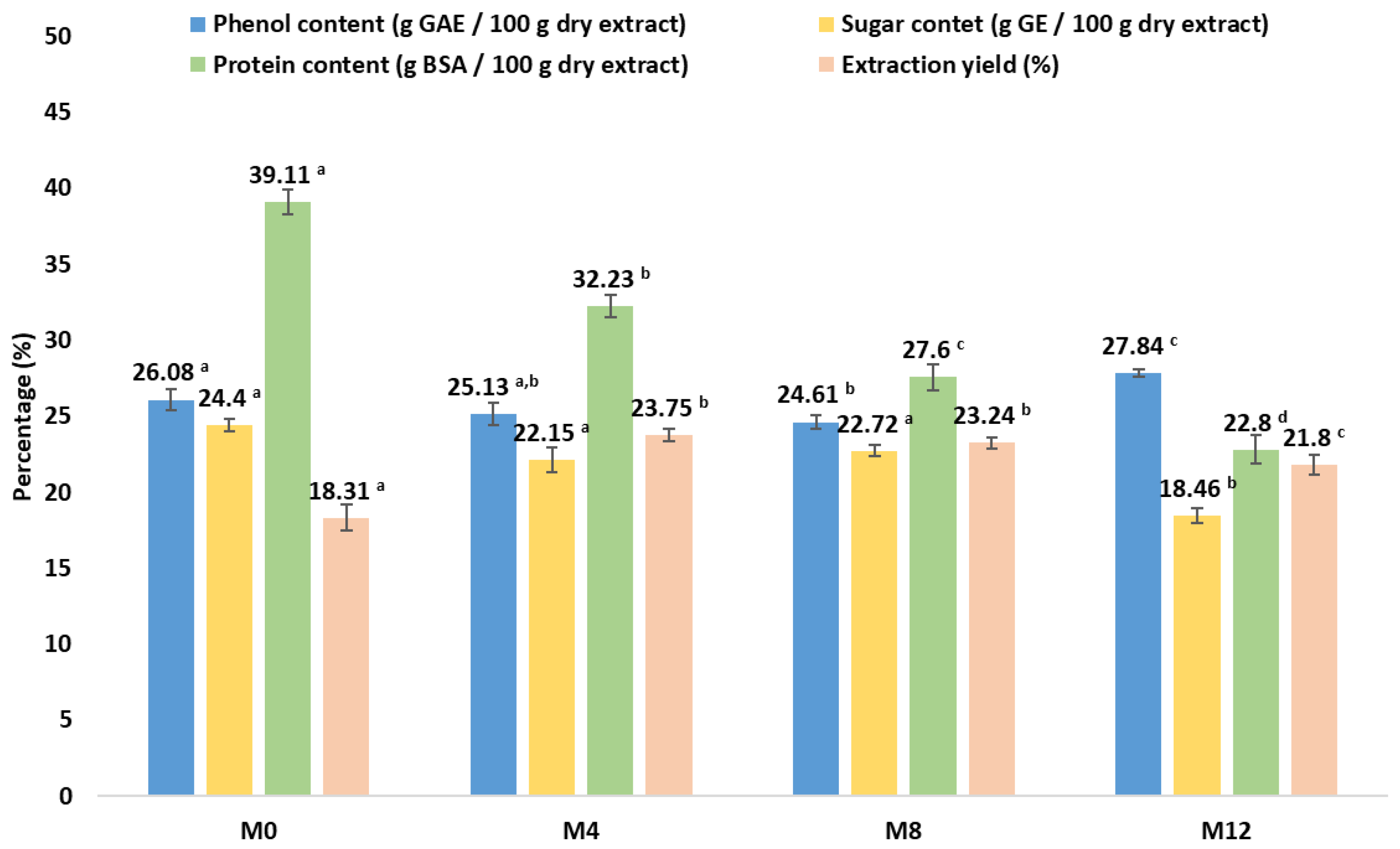

3.1. Characterization of E. globulus Branches and Leaves

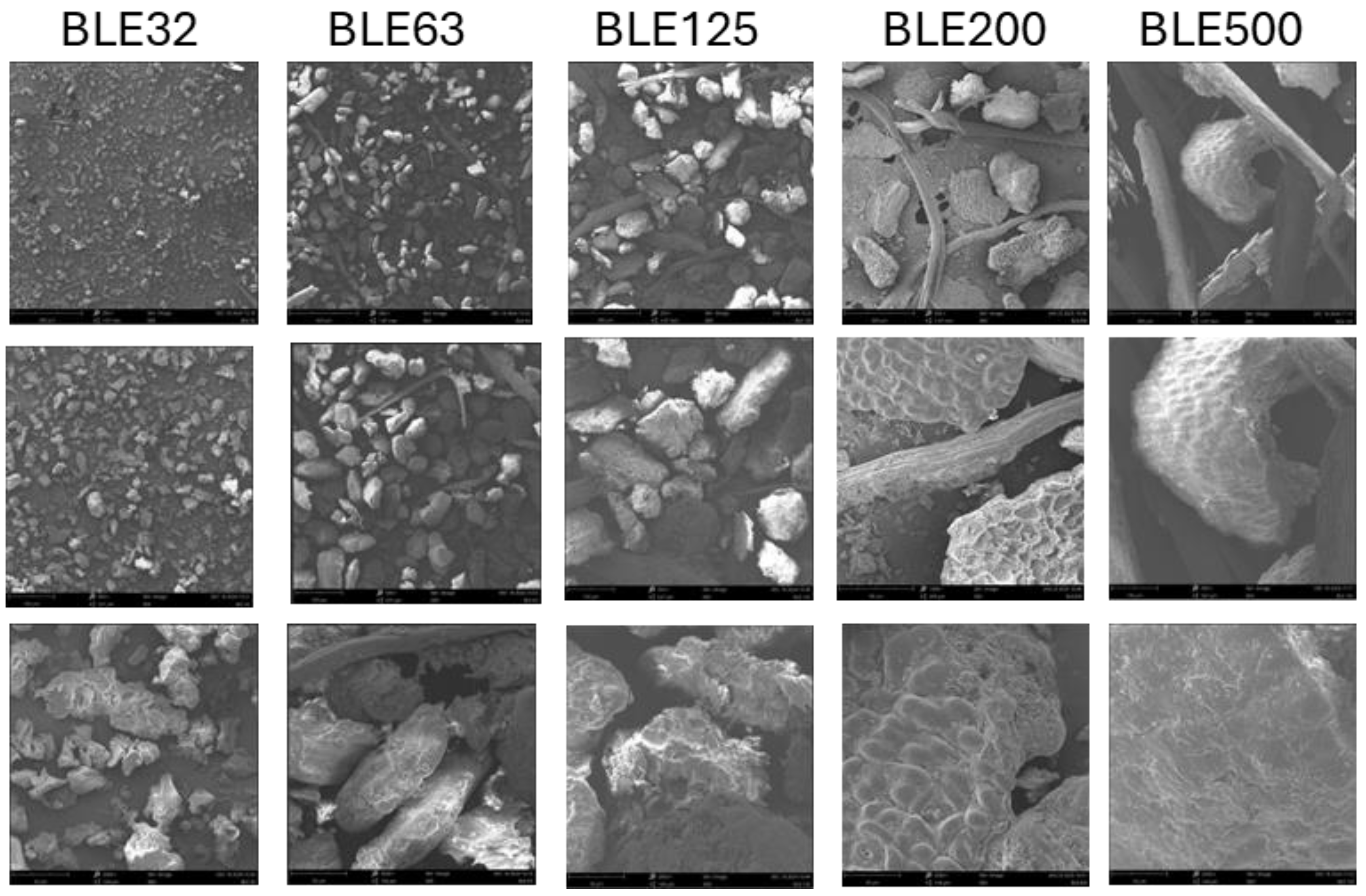

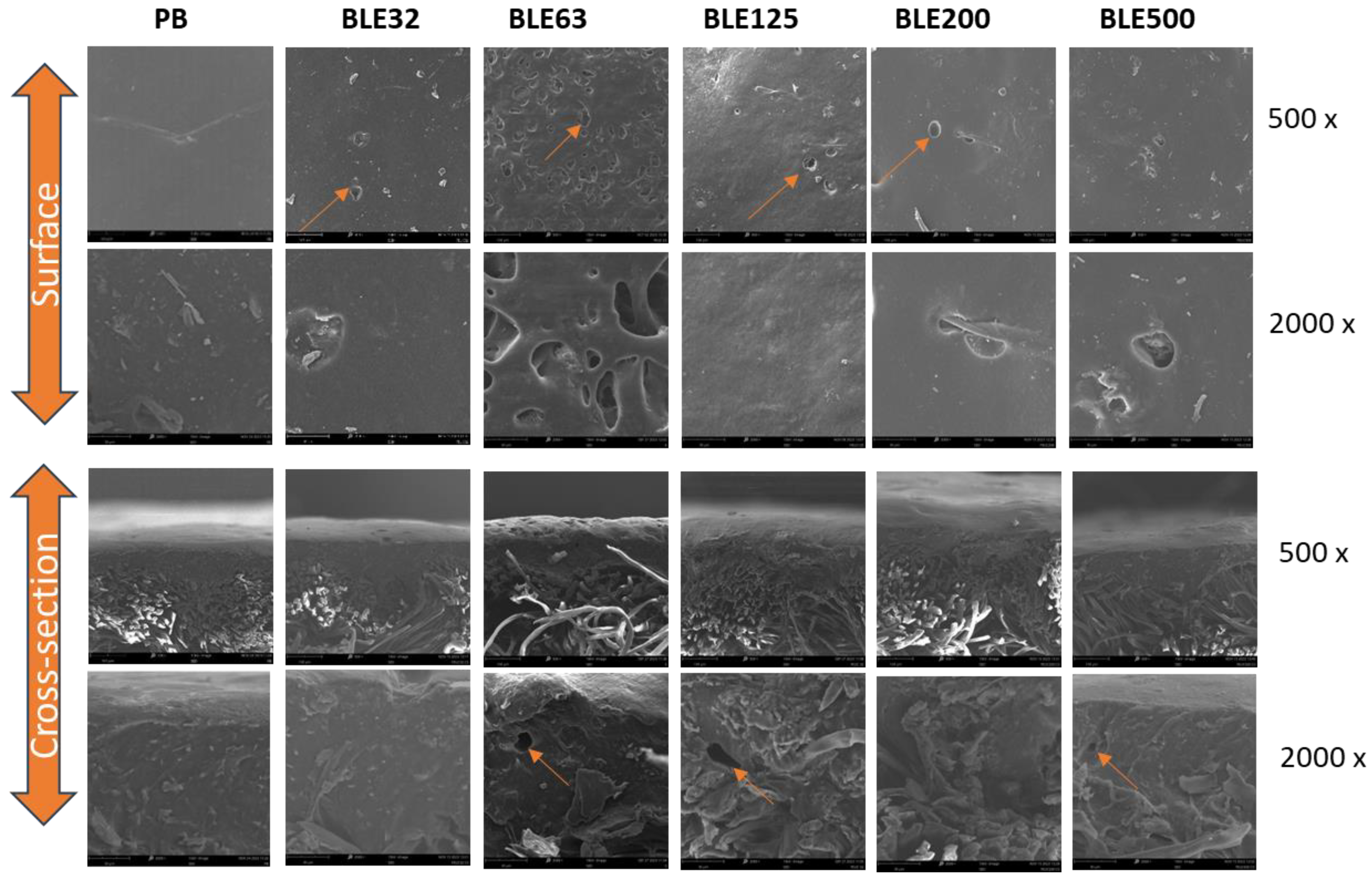

3.1.1. Characterization of the BLE Particles by SEM Microscopy

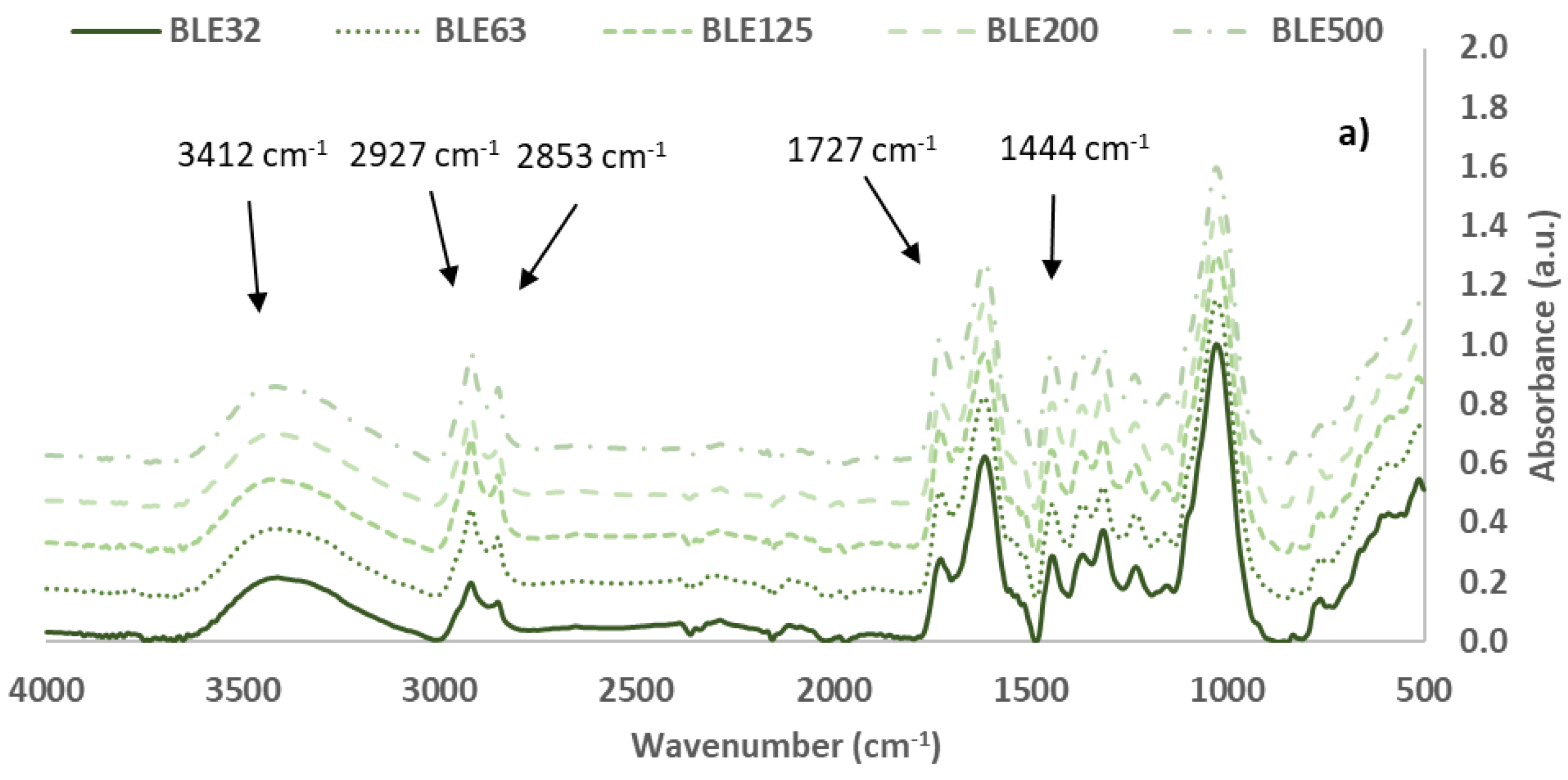

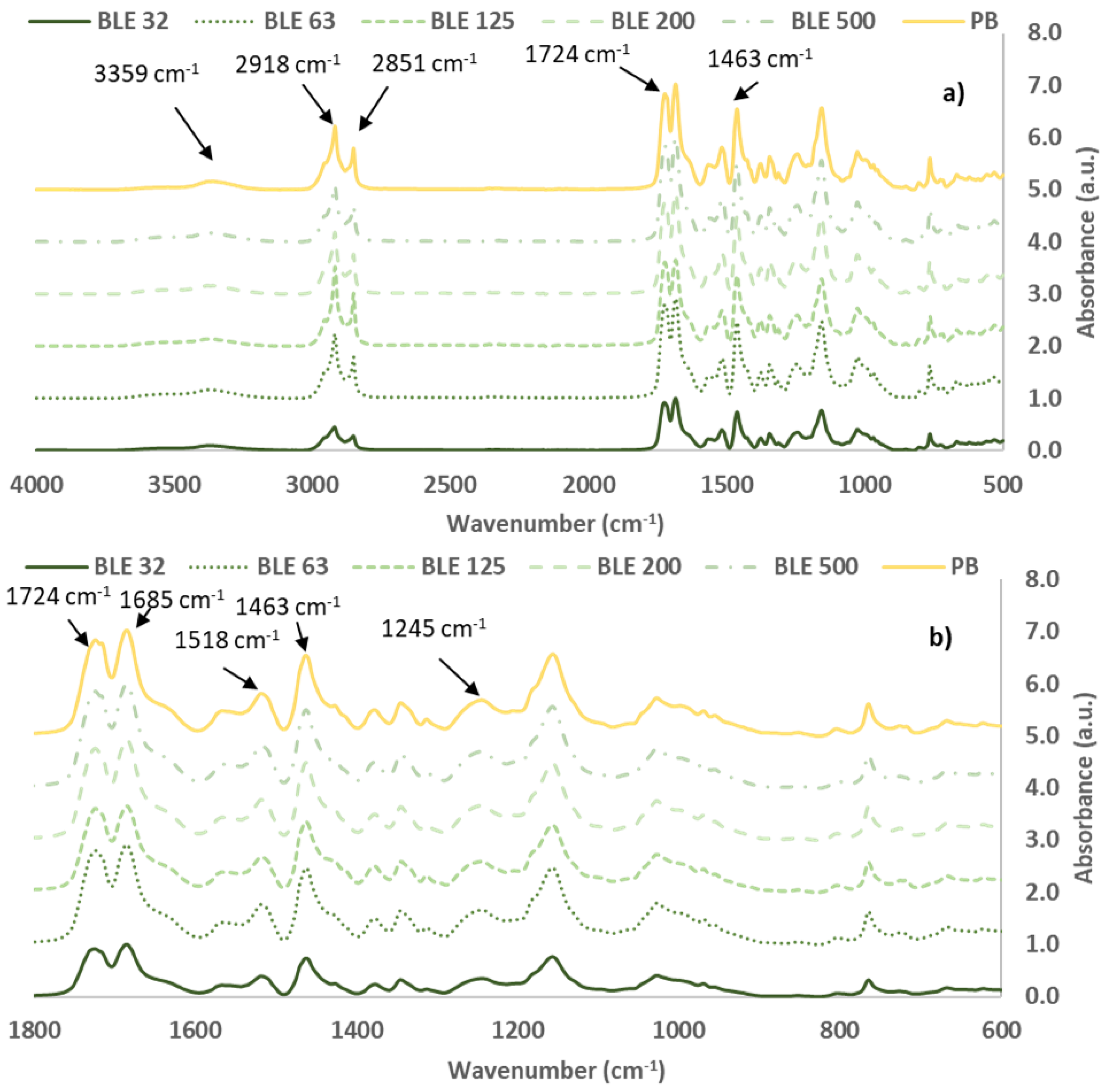

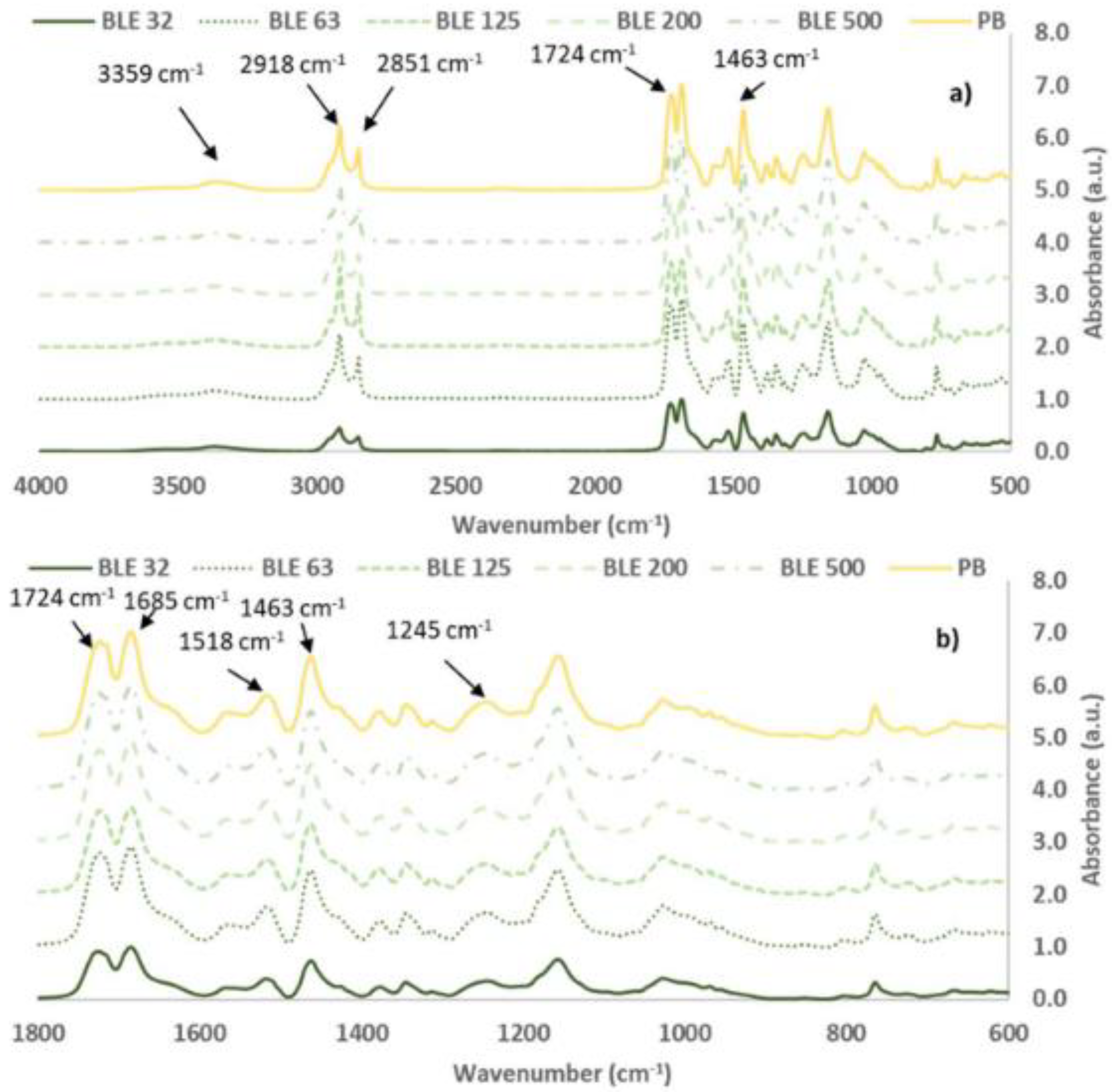

3.1.2. Characterisation of the BLE Particles by FTIR-ATR Spectroscopy

| BLE32 | BLE63 | BLE125 | BLE200 | BLE500 | Group | Integration Range | |

| cm-1 | % Area | % Area | % Area | % Area | % Area | ||

| 2920 | 4.15 ± 0.16 a | 5.98 ± 0.19 b | 6.35 ± 0.26 b | 6.74 ± 0.05 b,b | 5.70 ± 0.36 b,c | -CH2- asymmetric stretch | 3000-2800 |

| 2852 | -CH2- symmetric stretch | ||||||

| 1467 | 0.41 ± 0.01 a | 0.52 ± 0.02 b | 0.53 ± 0.03 b | 0.53 ± 0.03 b | 0.54 ± 0.03 b | CH- deformation; asymmetric in -CH2 | 1480-1460 |

| 1315 | 3.40 ± 0.04 | 3.11 ± 0.07 | 3.10 ± 0.02 | 3.22 ± 0.22 | 3.24 ± 0.02 | CH2 deformation medium-weak |

1340-1285 |

| 721 | 0.55 ± 0.01 | 0.58 ± 0.06 | 0.52 ± 0.04 | 0.53 ± 0.01 | 0.55 ± 0.01 | C-C Alkanes skeletal vibrations |

730-710 |

| ∑ Area | 8.50 ± 0.22 a | 10.35 ± 0.39 b | 11.02 ± 0.66 b | 11.22 ± 0.39 b | 10.03 ± 0.40 b |

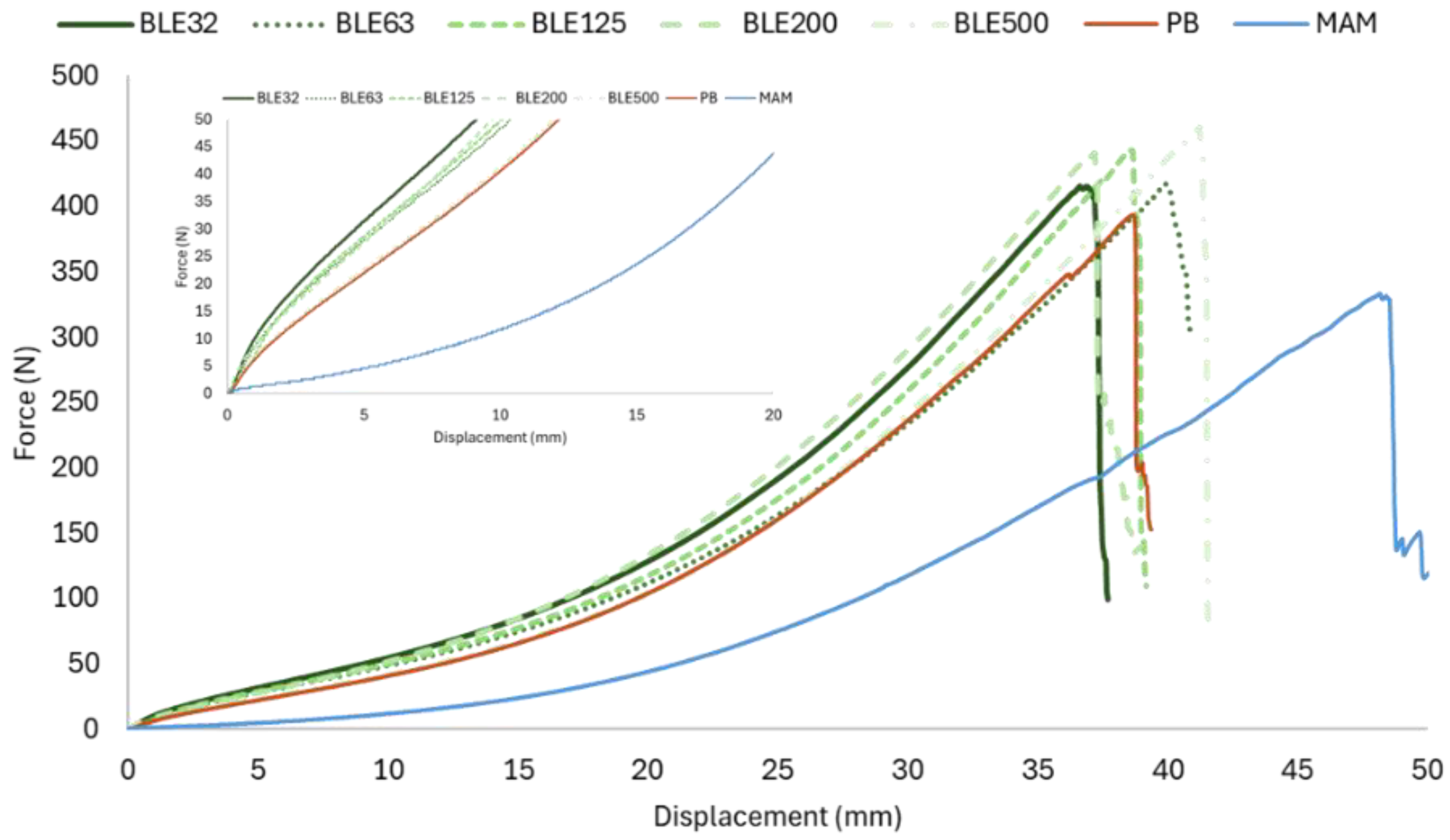

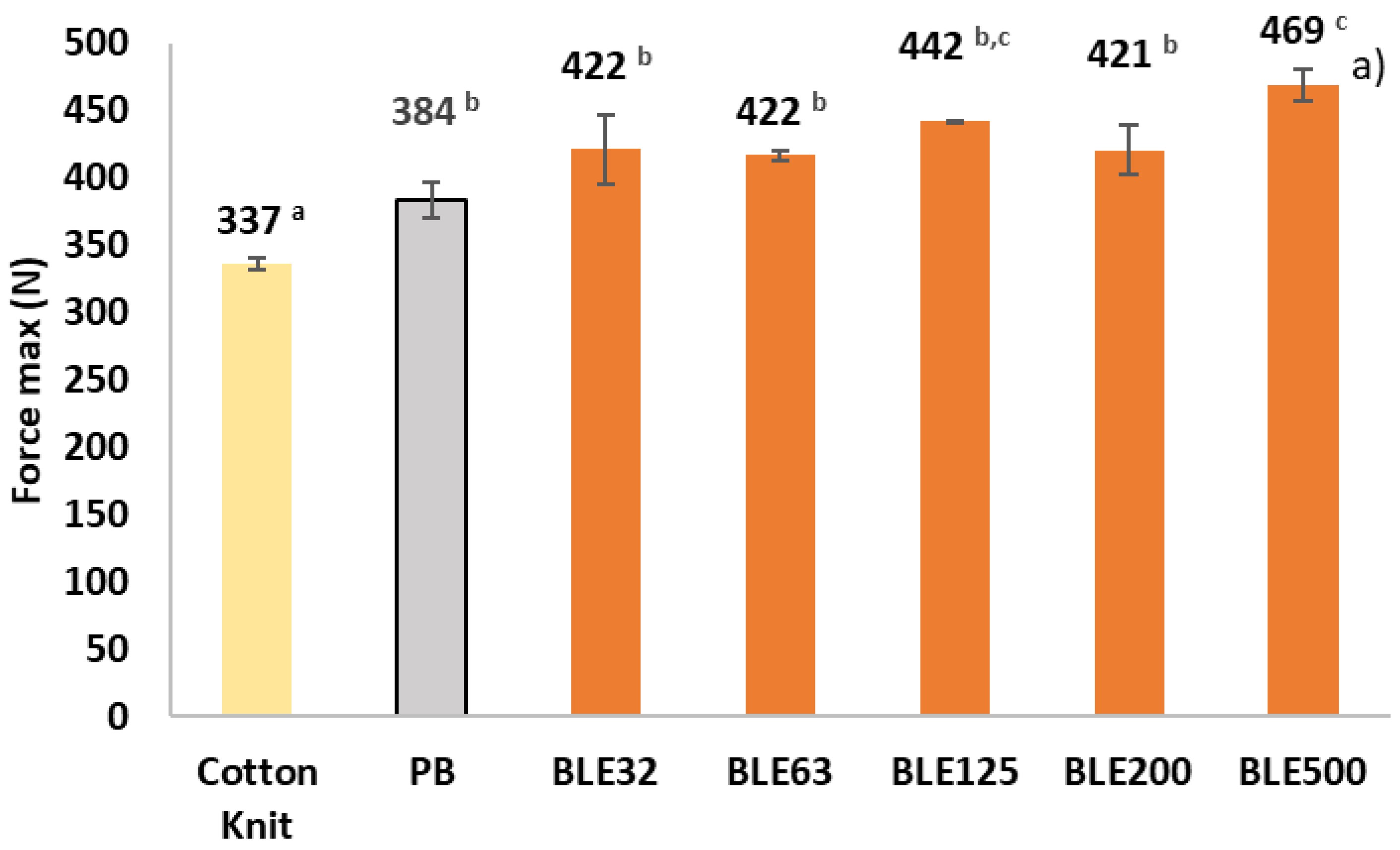

3.2. Production and Characterization of Coated Fabrics with BLE Particles

3.2.1. BLE Particles Impact on WPU Coating Formulation

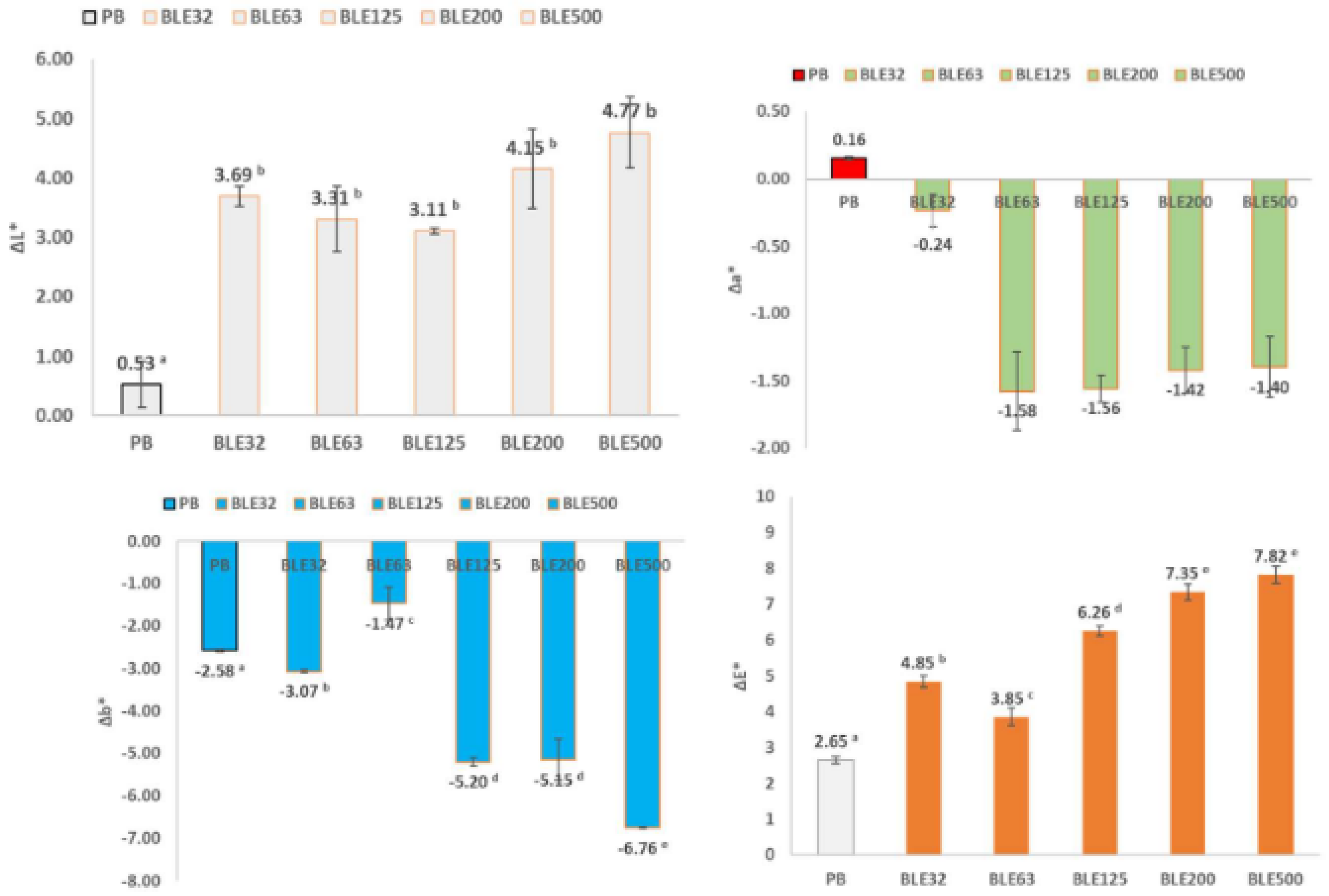

3.2.2. Analysis of Fabrics Coated with BLE Particles

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Escobar-Avello, D.; Ferrer, V.; Bravo-Arrepol, G.; Reyes-Contreras, P.; Elissetche, J.P.; Santos, J.; Fuentealba, C.; Cabrera-Barjas, G. Pretreated Eucalyptus Globulus and Pinus Radiata Barks: Potential Substrates to Improve Seed Germination for a Sustainable Horticulture. Forests 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Villasmil, V.; Fuentealba, C.; Reyes-Contreras, P.; Rubilar, R.; Cabrera-Barjas, G.; Bravo-Arrepol, G.; Escobar-Avello, D. Extracted Eucalyptus Globulus Bark Fiber as a Potential Substrate for Pinus Radiata and Quillaja Saponaria Germination. Plants 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Antorrena, G.; Freire, M.S.; Pizzi, A.; González-Álvarez, J. Environmentally Friendly Wood Adhesives Based on Chestnut (Castanea Sativa) Shell Tannins. European Journal of Wood and Wood Products 2017, 75. [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Escobar-Avello, D.; Fuentealba, C.; Cabrera-Barjas, G.; González-Álvarez, J.; Martins, J.M.; Carvalho, L.H. Forest By-Product Valorization: Pilot-Scale Pinus Radiata and Eucalyptus Globulus Bark Mixture Extraction. Forests 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Casas-Ledón, Y.; Daza Salgado, K.; Cea, J.; Arteaga-Pérez, L.E.; Fuentealba, C. Life Cycle Assessment of Innovative Insulation Panels Based on Eucalyptus Bark Fibers. J Clean Prod 2020, 249. [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Freitas, B.; Fernandes, R.A.; Escobar-Avello, D.; Gomes, T.; Magalhães, P.; Magalhães, F.D.; Martins, J.M.; Carvalho, L.H. Ultrasonic-Assisted Water Extraction from Eucalyptus Globulus Leaves and Branches, to Obtain Natural Textile Dyes with Antioxidant Properties. Ind Crops Prod 2025, 228, 120885. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.; Dietrich, S.; Schulz, H.; Mondschein, A. Comparison of the Technical Performance of Leather, Artificial Leather, and Trendy Alternatives. Coatings 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.; Vilaça, H.; Antunes, J.; Rocha, A.; Silva, C. Textile Bio-Based and Bioactive Coatings Using Vegetal Waste and by-Products. Base Diseño e Innovación 2022, 7. [CrossRef]

- Coelho, L.; Isabel Magalhães, A.; Fernandes, S.; Batista, P.; Pintado, M.; Faria, P.; Costa, C.; Moura, B.; Marinho, A.; Maria, R.; et al. Innovation of Textiles through Natural By-Products and Wastes. In Waste in Textile and Leather Sectors; 2020.

- Nolasco, A.; Esposito, F.; Cirillo, T.; Silva, A.; Silva, C. Coffee Silverskin: Unveiling a Versatile Agri-Food By-Product for Ethical Textile Coatings. In Proceedings of the Communications in Computer and Information Science; 2024; Vol. 1937 CCIS.

- Castro, J.A.; Balbo, R.; Silva, C.J.; Fernández, C.F.; Carrasco, F.A. Material Textile Design as a Trigger for Transdisciplinary Collaboration: Coating Bio-Based Textiles Using Waste from the Wood Industry. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ghazal, H.; Saad, F.; Hegazy, B.M.; Sedik, A.; Hassabo, A.G. Polyurethane and Its Application in Textile Industry. Letters in Applied NanoBioScience 2024, 13.

- Neiva, D.M.; Araújo, S.; Gominho, J.; Carneiro, A. de C.; Pereira, H. Potential of Eucalyptus Globulus Industrial Bark as a Biorefinery Feedstock: Chemical and Fuel Characterization. Ind Crops Prod 2018, 123, 262–270. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, G.; Fernández-Agulló, A.; Freire, M.S.; Antorrena, G.; González-Álvarez, J. Chestnut Bur Extracts as Antioxidants: Optimization of the Extraction Stage. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment 2010, 140. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, G.; Santos, J.; Freire, M.S.; Antorrena, G.; González-Álvarez, J. Extraction of Antioxidants from Eucalyptus (Eucalyptus Globulus) Bark. Wood Sci Technol 2012, 46. [CrossRef]

- Ghaheh, F.S.; Khoddami, A.; Alihosseini, F.; Jing, S.; Ribeiro, A.; Cavaco-Paulo, A.; Silva, C. Antioxidant Cosmetotextiles: Cotton Coating with Nanoparticles Containing Vitamin E. Process Biochemistry 2017, 59, 46–51. [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Sherazee, M.; Marvi, P.K.; Ahmed, S.R.; Gedanken, A.; Srinivasan, S.; Rajabzadeh, A.R. Waste-Derived Sustainable Fluorescent Nanocarbon-Coated Breathable Functional Fabric for Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Applications. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2023, 15, 29425–29439. [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, F. Investigating the Usage of Eucalyptus Leaves in Antibacterial Finishing of Textiles against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria. Journal of the Textile Institute 2021, 112, 341–345. [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Avello, D.; Olmo-Cunillera, A.; Lozano-Castellón, J.; Marhuenda-Muñoz, M.; Vallverdú-Queralt, A. A Targeted Approach by High Resolution Mass Spectrometry to Reveal New Compounds in Raisins. Molecules 2020, 25. [CrossRef]

- Członka, S.; Strakowska, A.; Pospiech, P.; Strzelec, K. Effects of Chemically Treated Eucalyptus Fibers on Mechanical, Thermal and Insulating Properties of Polyurethane Composite Foams. Materials 2020, 13. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Son, Y.G.; Kang, S.D.; Lee, S.W.; Kim, K.D.; Kim, J.Y. Characterization of Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Eucalyptus Globulus Leaves under Different Extraction Conditions. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- SINGH, S.; RAGHAV, S.; KALYANARAMAN, K.; SAIFI, A. Partial Purification and De- Staining Property of Protease from Leaves and Seeds of Eucalyptus Globulus and Fruit of Azadirachta Indica. Int J Pharma Bio Sci 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, S.C.; Soares, C.P.B.; Fehrmann, L.; Jacovine, L.A.G.; von Gadow, K. Biomassa Acima e Abaixo Do Solo e Estimativas de Carbono Para Um Plantio Clonal de Eucalipto No Sudeste Do Brasil. Revista Arvore 2015, 39, 353–363. [CrossRef]

- Wendler, R.; Carvalho, P.O.; Pereira, J.S.; Millard, P. Role of Nitrogen Remobilization from Old Leaves for New Leaf Growth of Eucalyptus Globulus Seedlings. Tree Physiol 1995, 15. [CrossRef]

- Grasel, F.D.S.; Ferrão, M.F.; Wolf, C.R. Development of Methodology for Identification the Nature of the Polyphenolic Extracts by FTIR Associated with Multivariate Analysis. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc 2016, 153, 94–101. [CrossRef]

- Poletto, M.; Ornaghi Júnior, H.L.; Zattera, A.J. Native Cellulose: Structure, Characterization and Thermal Properties. Materials 2014. [CrossRef]

- Yemele, M.C.N.; Koubaa, A.; Cloutier, A.; Soulounganga, P.; Wolcott, M. Effect of Bark Fiber Content and Size on the Mechanical Properties of Bark/HDPE Composites. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2010, 41, 131–137. [CrossRef]

- Kačík, F.; Ďurkovič, J.; Kačíková, D. Chemical Profiles of Wood Components of Poplar Clones for Their Energy Utilization. Energies (Basel) 2012, 5, 5243–5256. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wei, Y.; Xu, J.; Xu, N.; He, Y. Quantitative Visualization of Lignocellulose Components in Transverse Sections of Moso Bamboo Based on FTIR Macro- and Micro-Spectroscopy Coupled with Chemometrics. Biotechnol Biofuels 2018. [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Delgado, N.; Fuentes, J.; Fuentealba, C.; Vega-Lara, J.; García, D.E. Exterior Grade Plywood Adhesives Based on Pine Bark Polyphenols and Hexamine. Ind Crops Prod 2018, 122, 340–348. [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Pereira, J.; Escobar-Avello, D.; Ferreira, I.; Vieira, C.; Magalhães, F.D.; Martins, J.M.; Carvalho, L.H. Grape Canes (Vitis Vinifera L.) Applications on Packaging and Particleboard Industry: New Bioadhesive Based on Grape Extracts and Citric Acid. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Escobar-Avello, D.; Magalhães, P.; Magalhães, F.D.; Martins, J.M.; González-Álvarez, J.; de Carvalho, L.H. High-Value Compounds Obtained from Grape Canes (Vitis Vinifera L.) by Steam Pressure Alkali Extraction. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2022, 133. [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Yu, J.; Tesso, T.; Dowell, F.; Wang, D. Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Lignocellulosic Biomass Using Infrared Techniques : A Mini-Review. Appl Energy 2013, 104, 801–809. [CrossRef]

- Poletto, M.; Ornaghi Júnior, H.L.; Zattera, A.J. Native Cellulose: Structure, Characterization and Thermal Properties. Materials 2014, 7. [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Yu, J.; Tesso, T.; Dowell, F.; Wang, D. Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Lignocellulosic Biomass Using Infrared Techniques: A Mini-Review. Appl Energy 2013, 104.

- Poletto, M.; Ornaghi Júnior, H.L.; Zattera, A.J. Native Cellulose: Structure, Characterization and Thermal Properties. Materials 2014, 7. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Cerrada, R.; Tavernier, R.; Caillol, S. Fully Bio-Based Thermosetting Polyurethanes from Bio-Based Polyols and Isocyanates. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Zuliani, A.; Rapisarda, M.; Chelazzi, D.; Baglioni, P.; Rizzarelli, P. Synthesis, Characterization, and Soil Burial Degradation of Biobased Polyurethanes. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Socrates, G. Infrared and Raman Characteristic Group Frequencies. Tables and Charts; 2001;

- Asefnejad, A.; Khorasani, M.T.; Behnamghader, A.; Farsadzadeh, B.; Bonakdar, S. Manufacturing of Biodegradable Polyurethane Scaffolds Based on Polycaprolactone Using a Phase Separation Method: Physical Properties and in Vitro Assay. Int J Nanomedicine 2011, 6. [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Xiao, K.; Tang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Dai, J.; Long, R.; Liao, W. Preparation and Characterization of Polyurethane (PU)/Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) Blending Membrane. Desalination Water Treat 2016, 57. [CrossRef]

- Hosseinpourpia, R.; Adamopoulos, S.; Echart, A.S.; Eceiza, A. Polyurethane Films Prepared with Isophorone Diisocyanate Functionalized Wheat Starch. Eur Polym J 2021, 161. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.B.; Lee, S. Il; Nah, C.; Lee, Y.S. Preparation of Waterborne Polyurethanes Using an Amphiphilic Diol for Breathable Waterproof Textile Coatings. Prog Org Coat 2009, 66. [CrossRef]

- Katović, D.; Grgac, S.F.; Bischof-Vukušić, S.; Katović, A. Formaldehyde Free Binding System for Flame Retardant Finishing of Cotton Fabrics. Fibres and Textiles in Eastern Europe 2012, 90.

- Son, T.W.; Lee, D.W.; Lim, S.K. Thermal and Phase Behavior of Polyurethane Based on Chain Extender, 2,2-Bis-[4-(2-Hydroxyethoxy)Phenyl]Propane. Polym J 1999, 31. [CrossRef]

- Noureddine, B.; Zitouni, S.; Achraf, B.; Houssém, C.; Jannick, D.R.; Jean-François, G. Development and Characterization of Tailored Polyurethane Foams for Shock Absorption. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Bakhshi, H.; Yeganeh, H.; Yari, A.; Nezhad, S.K. Castor Oil-Based Polyurethane Coatings Containing Benzyl Triethanol Ammonium Chloride: Synthesis, Characterization, and Biological Properties. J Mater Sci 2014, 49. [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.; Strain, J. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma(FRAP)as a Measure of “Antioxidan Power”:The FRAP Assay Analytical Biochemistry. Anal Biochem 1996, 239.

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a Free Radical Method to Evaluate Antioxidant Activity. LWT - Food Science and Technology 1995, 28.

- Allehyani, E.S. Surface Functionalization of Polyester Textiles for Antibacterial and Antioxidant Properties. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

| Sample |

Polyurethane % (dry basis) |

Isocyanate % (dry basis) |

BLE % (dry basis) |

Additives % (dry basis) |

| PB | 62.0 | 29.5 | 0.0 | 8.6 |

| BLE 32 | 55.8 | 26.5 | 10.0 | 7.7 |

| BLE 63 | 55.8 | 26.5 | 10.0 | 7.7 |

| BLE 125 | 55.8 | 26.5 | 10.0 | 7.7 |

| BLE 200 | 55.8 | 26.5 | 10.0 | 7.7 |

| BLE 500 | 55.8 | 26.5 | 10.0 | 7.7 |

| Samples |

Particle size (µm) |

Fiber | Amorphous particle | |

| Length (µm) | Width (µm) | Length (µm) | ||

| BLE32 | >32 | 247.0 ± 41.0 | 15.0 ± 2.1 | 28.6 ± 11.9 |

| BLE63 | 32-63 | 225.9 ± 83.2 | 18.7 ± 5.3 | 51.2 ± 14.4 |

| BLE125 | 63-125 | 535.8 ± 180.2 | 45.0 ± 4.2 | 112.5 ± 39.9 |

| BLE200 | 125-200 | 176.6 ± 43.2 | 49.3 ± 7.3 | 176.6 ± 43.2 |

| BLE500 | 200-500 | 912.5 ± 20.1 | 136.5 ± 7.8 | 398.0 ± 70.7 |

| Samples | Fiber | Amorphous particle | ||||

| C (%) | O (%) | N (%) | C (%) | O (%) | N (%) | |

| BLE32 | 74.7 ± 2.9 a | 21.8 ± 2.5 a | 3.6 ± 1.4 a | 66.0 ± 6.9 a | 26.5 ± 6.4 a | 7.5 ± 2.6 a |

| BLE63 | 66.0 ± 5.5 b | 27.9 ± 4.8 b | 6.1 ± 0.8 b | 52.2 ± 5.9 a | 32.9 ± 8.5 a | 14.9 ± 3.6 b |

| BLE125 | 65.7± 6.2 b | 28.9 ± 4.9 b | 6.2 ± 0.6 b | 60.6 ± 7.8 a | 31.5 ± 7.6 a | 7.8 ± 1.6 a |

| BLE200 | 48.3 ± 0.9 c | 42.3 ± 2.8 c | 10.8 ± 2.0 b | 62.1 ± 3.1 a | 30.8 ± 3.5 a | 7.0 ± 2.2 a |

| BLE500 | 50.7 ± 5.6 c | 40.5 ± 4.1 c | 10.0 ± 3.6 b | 47.2 ± 5.8 b | 44.5 ± 6.4 b | 8.2 ± 4.0 a |

| BLE32 | BLE63 | BLE125 | BLE200 | BLE500 | |||

| cm-1 | Intensity | Intensity | Intensity | Intensity | Intensity | Group | Range |

| 3412* | 21.7 ± 0.1 | 23.3 ± 0.2 | 24.6 ± 0.2 | 25.2 ± 0.7 | 26.0 ± 0.7 | -OH stretch | 3300-3400 |

| 2920* | 19.9 ± 0.3 | 29.9 ± 2.9 | 39.0 ± 3.3 | 30.8 ± 3.3 | 37.7 ± 7.0 | -CH2- asymmetric stretch | 2916-2936 |

| 2853* | 13.5 ± 0.2 | 20.4 ± 2.0 | 26.5 ± 2.3 | 20.7 ± 2.3 | 25.7 ± 4.9 | -CH2- symmetric stretch | 2843-2863 |

| 1727* | 27.9 ± 0.7 | 35.8 ± 1.9 | 42.9 ± 3.4 | 36.6 ± 2.1 | 42.5 ± 3.6 | C=O stretch in unconjugated ketones, carbonyls and in ester groups (hemicellulose) | 1738 |

| 1615* | 62.3 ± 1.6 | 67.6 ± 0.5 | 67.2 ± 1.8 | 69.8 ± 0.6 | 68.5 ± 4.8 | Aromatic skeletal vibration and C=O stretch (lignin) | 1595 |

| 1551* | 17.7 ± 0.4 | 19.8 ± 0.0 | 17.9 ± 1.0 | 17.5 ± 0.9 | 17.6 ± 0.8 | CAR=CAR (Pp cd.) | 1500-1600 |

| 1454* | 23.7 ± 0.8 | 27.0 ± 1.2 | 30.5 ± 1.4 | 31.1 ± 1.5 | 33.6 ± 3.2 | C=C and C-H bond O-H in plane deformation (lignin and hemicellulose) | 1450-1453 |

| 1444* | 28.8 ± 0.2 | 31.3 ± 0.4 | 34.7 ± 0.6 | 35.4 ± 1.0 | 37.0 ± 3.8 | CH- deformation; asymmetric in -CH3 and -CH2- (cellulose) | 1430-1485 |

| 1367 | 29.4 ± 0.2 | 31.5 ± 0.2 | 34.1 ± 0.7 | 34.4 ± 0.7 | 36.1 ± 2.6 | CH deformation (cellulose and hemicellulose) | 1372 |

| 1315 | 37.5 ± 0.6 | 37.4 ± 0.3 | 38.3 ± 0.4 | 40.0 ± 0.6 | 39.7 ± 2.9 | Ph-CHR-OH deformation | 1260-1350 |

| 1232 | 25.3 ± 0.1 | 28.2 ± 0.2 | 29.9 ± 1.4 | 28.6 ± 1.5 | 29.9 ± 2.1 | Syringyl ring and C=C stretch in lignin and xylan | 1235 |

| 1153 | 18.9 ± 0.0 | 21.5 ± 0.9 | 24.0 ± 2.2 | 21.1 ± 0.8 | 23.2 ± 1.8 | Involves C-O stretching of C-OH/C-O-C (cellulose) | 1160 |

| 1027 | 100.0 ± 0.0 | 100.0 ± 0.0 | 100.0 ± 0.0 | 100.1 ± 0.1 | 100.0 ± 0.1 | C-O, C-C, and C-C-O stretch (cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin) | 1025-1035 |

| 832 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | C-O-C aromatic ethers, symmetric stretch | 810-850 |

| 763 | 14.4 ± 0.3 | 13.6 ± 0.0 | 12.7 ± 0.6 | 12.4 ± 1.3 | 12.9 ± 0.7 | C-C Alkanes skeletal vibrations | 720–750 |

| BLE32 | BLE63 | BLE125 | BLE200 | BLE500 | Group | Integration Range | |

| cm-1 | % Area | % Area | % Area | % Area | % Area | ||

| 1444 | 3.12 ± 0.05a | 3.09 ± 0.01a | 3.40 ± 0.00 a | 3.47 ± 0.00 b | 3.53 ± 0.00 b | CH2 deformation medium-weak |

1400-1485 |

| 1367 | 2.18 ± 0.02 a | 2.16 ± 0.02 a | 2.24 ± 0.00 a | 2.32 ± 0.02 b | 2.35 ± 0.05 b | CH deformation | 1390-1350 |

| 1315 | 3.62 ± 0.05 | 3.36 ± 0.01 | 3.29 ± 0.01 | 3.54 ± 0.09 | 3.35 ± 0.12 | CH2 deformation medium-weak |

1340-1280 |

| 1153 | 2.15 ± 0.04 | 2.20 ± 0.13 | 2.26 ± 0.23 | 2.09 ± 0.06 | 2.20 ± 0.01 | C-O stretch of C-OH / C-O-C medium |

1195-1130 |

| 1100 | 2.72 ± 0.16 | 2.51 ± 0.17 | 2.44 ± 0.17 | 2.52 ± 0.14 | 2.49 ± 0.15 | C-O-C stretch medium |

1130-1090 |

| 1027 | 13.55 ± 0.09 a | 12.52 ± 0.03 a | 12.05 ± 0.20 b | 12.60 ± 0.06 a | 12.40 ± 0.62 a | CO stretch medium-strong |

1068-990 |

| ∑ Area | 27.16 ± 0.21 a | 25.75 ± 0.31 b | 25.59 ± 0.14 b | 26.45 ± 0.16 a | 26.29 ± 0.61 a |

| BLE32 | BLE63 | BLE125 | BLE200 | BLE500 | Group | Integration Range | |

| cm-1 | % Area | % Area | % Area | % Area | % Area | ||

| 1688 | 1.72 ± 0.32 | 1.74 ± 0.09 | 1.86 ± 0.23 | 1.68 ± 0.14 | 1.60 ± 0.23 | C=O stretch | 1670-1700 |

| 1616 | 7.61 ± 0.51 | 7.87 ± 0.30 | 7.60 ± 0.36 | 7.70 ± 0.52 | 7.33 ± 0.71 | Aryl ring stretch, asymmetric | 1560-1640 |

| 1516 | 0.62 ± 0.03 a | 0.69 ± 0.01 b | 0.58 ± 0.04 a | 0.57 ± 0.01 a | 0.57 ± 0.01 a | Aryl ring stretch, asymmetric | 1488-1525 |

| 1446 | 3.39 ± 0.13 | 3.50 ± 0.06 | 3.60 ± 0.02 | 3.24 ± 0.14 | 3.43 ± 0.71 | OH deformation, asymmetric, OCH3 CH deformation, asymmetric, S-mode | 1400-1485 |

| 1315 | 3.21 ± 0.26 | 3.08 ± 0.10 | 2.99 ± 0.26 | 3.08 ± 0.28 | 2.74 ± 0.58 | Aryl ring breathing mode; CO stretch; S-mode. | 1290-1340 |

| 1234 | 3.13 ± 0.14 | 3.09 ± 0.19 | 3.18 ± 0.31 | 3.07 ± 0.35 | 3.20 ± 0.36 | Syringyl ring and C=C stretch in lignin and Xylan | 1195-1265 |

| 1160 | 2.08 ± 0.11 | 2.16 ± 0.09 | 2.23 ± 0.03 | 2.11 ± 0.07 | 2.14 ± 0.29 | C-H stretch in G-ring | 1135-1190 |

| ∑ Area | 20.89 ± 0.14 a | 21.32 ± 0.28 a | 22.50 ± 0.47 a,b | 20.82 ± 0.88 a | 19.86 ± 0.57 a,a |

| Sample | µ(mPa⋅s) | Foam density (g/l) | Solid content (%) |

| PB | 8.6 | 218.1 | 39.6 |

| BLE 32 | 54.05 | 263.6 | 42.5 |

| BLE 63 | 63.41 | 275.6 | 42.8 |

| BLE 125 | 70.41 | 217.1 | 42.4 |

| BLE 200 | 65.01 | 222.6 | 42.2 |

| BLE 500 | 41.25 | 200.6 | 43.0 |

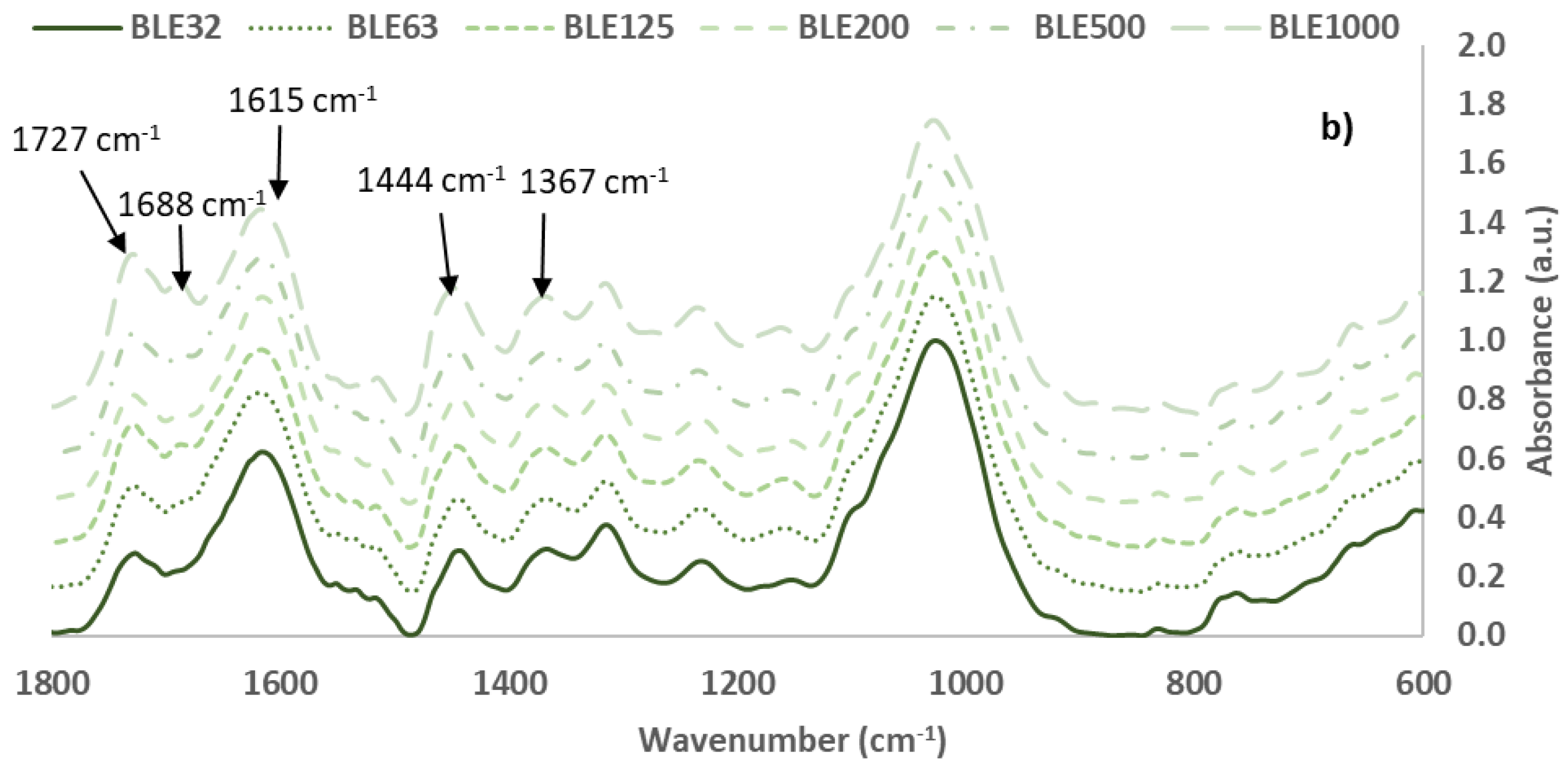

| Samples/Coatings | L * | a * | b * | ΔL * | Δa * | Δb * | ΔE* |

| PB | 87.7 ± 0.2 a | 0.12 ± 0.10 a | 9.2 ± 0.3 a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| BLE32 | 51.3 ± 1.6 b | 8.10 ± 0.48 b | 33.6 ± 1.0 b | -22.3 | 5.1 | 23.1 | 32.5 |

| BLE63 | 46.8 ± 0.9 c | 10.73 ± 0.18 c | 30.5 ± 0.9 c | -26.2 | 6.4 | 25.3 | 37.0 |

| BLE125 | 57.1 ± 0.4 d | 7.65 ± 0.15 b | 34.9 ± 0.3 b | -30.6 | 7.5 | 25.7 | 40.7 |

| BLE200 | 61.5 ± 1.0 e | 6.54 ± 0.30 d | 34.6 ± 0.6 b | -40.9 | 10.6 | 21.3 | 47.3 |

| BLE500 | 65.4 ± 1.3 f | 5.22 ± 0.12 e | 32.3 ± 0.4 c | -36.4 | 8.0 | 24.3 | 44.5 |

| PB-BLE32 | PB-BLE63 | PB-BLE125 | PB-BLE200 | PB-BLE500 | PB | Group |

Integration Range (cm-1) |

||

| cm-1 | Area (%) | Area (%) | Area (%) | Area (%) | Area (%) | Area (%) | |||

| 3520 | 2.16 ± 0.06 a | 2.05 ± 0.16 a | 1.87 ± 0.08 b | 2.02 ± 0.08 a | 2.13± 0.04 a | 1.22 ± 0.01 c | -OH stretch | 3450-3700 | |

| 3383 | 4.13 ± 0.09 a | 3.66 ± 0.18 b | 3.02 ± 0.36 c | 3.63 ± 0.09 b | 3.75 ± 0.07 b | 3.42 ± 0.06 b | -N-H stretch | 3200-3450 | |

| 2917 | 7.96 ± 0.26 a | 8.84 ± 0.17 a | 10.1 ± 0.9 b | 8.6 ± 0.1 a | 8.7 ± 0.5 a | 9.1 ± 0.1 b | -CH2- asymmetric stretch | 2875-3020 | |

| 2851 | 2.50 ± 0.10 a | 2.96 ± 0.06 a | 3.66 ± 0.47 b | 2.91 ± 0.04 a | 2.88 ± 0.23a | 3.05 ± 0.03 a | -CH2- symmetric stretch | 2800-2875 | |

| -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | NCO isocyanate groups stretch | 2260-2270 | |

| 1724 | 8.37 ± 0.01 a | 8.11 ± 0.00 b | 7.55 ± 0.05 c | 8.03 ± 0.00 b | 8.30 ± 0.00 a | 8.47 ± 0.00 a | Urethane carbonyl groups non-hydrogen bonded [39] | 1745-1705 | |

| 1685 | 9.07 ± 0.10 a | 8.74 ± 0.02 a | 8.08 ± 0.35 b | 8.90 ± 0.04 a | 9.01 ± 0.14 a | 9.19 ± 0.02 a | Urethane carbonyl groups hydrogen bonded [39] | 1660-1705 | |

| 1518 | 3.55 ± 0.02 a | 3.48 ± 0.01 a | 3.27 ± 0.04 b | 3.47 ± 0.01 a | 3.58 ± 0.01 a | 3.82 ± 0.00 c | –NH and –C–N vibrations of the urethane linkages[38] | 1490-1540 | |

| 1463 | 5.75 ± 0.00 a | 5.80 ± 0.00 a | 5.81 ± 0.01 a | 5.98 ± 0.00 b | 5.87 ± 0.01 a | 6.28 ± 0.00 c | -CH2, -CH3 bending vibrations[38,40] | 1440-1490 | |

| 1245 | 4.84 ± 0.00 a | 4.62 ± 0.00 b | 4.41 ± 0.01 b | 4.70 ± 0.00 a | 4.81 ± 0.02 a | 4.82 ± 0.00 a | Deformation vibrations of the N-H bond and of the O-C-N bonds | 1220-1285 | |

| 1180 | 3.67 ± 0.00 a | 3.61 ± 0.00 a | 3.37 ± 0.03 b | 3.64 ± 0.00 a | 3.74 ± 0.00 a | 3.80 ± 0.00 a | Coupled C-N and C-O stretching vibrations | 1165-1195 | |

| 1065 | 0.97 ± 0.00 a | 0.91 ± 0.00 b | 0.91 ± 0.00 b | 0.85 ± 0.00 c | 0.83 ± 0.00 c | 0.76 ± 0.00 d | C–H stretching vibration[41] | 1080-1055 | |

| 1027 | 3.42 ± 0.01 a | 3.34 ± 0.01 a | 3.26 ± 0.00 a | 3.21 ± 0.00 b | 3.14 ± 0.00 b | 3.11 ± 0.00 b | C-O, C-C, and C-C-O stretch | 1005-1040 | |

| 764 | 1.85 ± 0.00 a | 1.82 ± 0.00 a | 1.71 ± 0.01 b | 1.85 ± 0.00 a | 1.84 ± 0.01 a | 1.67 ± 0.00 b | N-H out of plane bending | 740-785 | |

| 717 | 0.69 ± 0.00 a | 0.74 ± 0.00 b | 0.80 ± 0.00 c | 0.75 ± 0.00b | 0.74 ± 0.0 b | 0.62 ± 0.00 d | C-C Alkanes skeletal vibrations | 705-735 | |

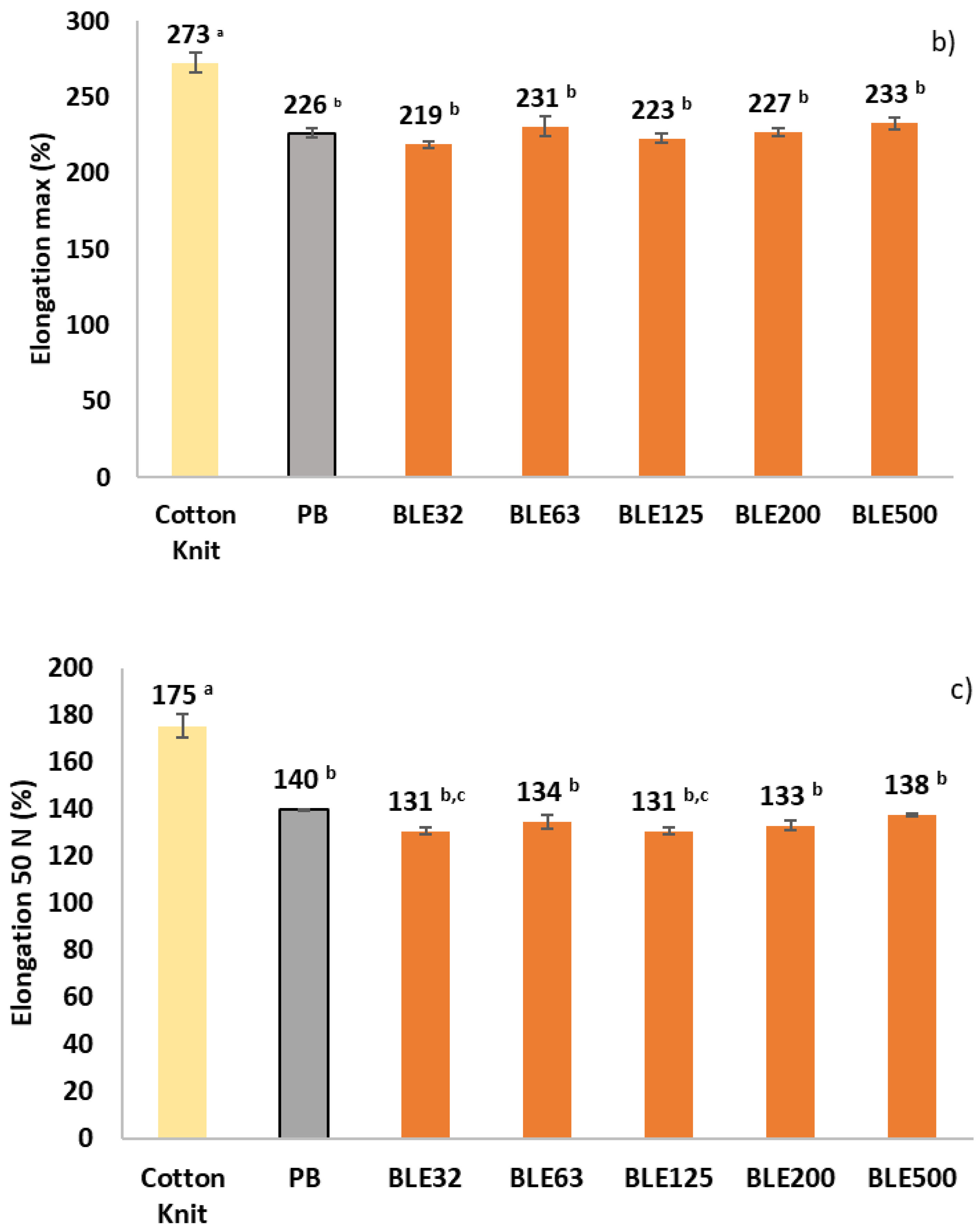

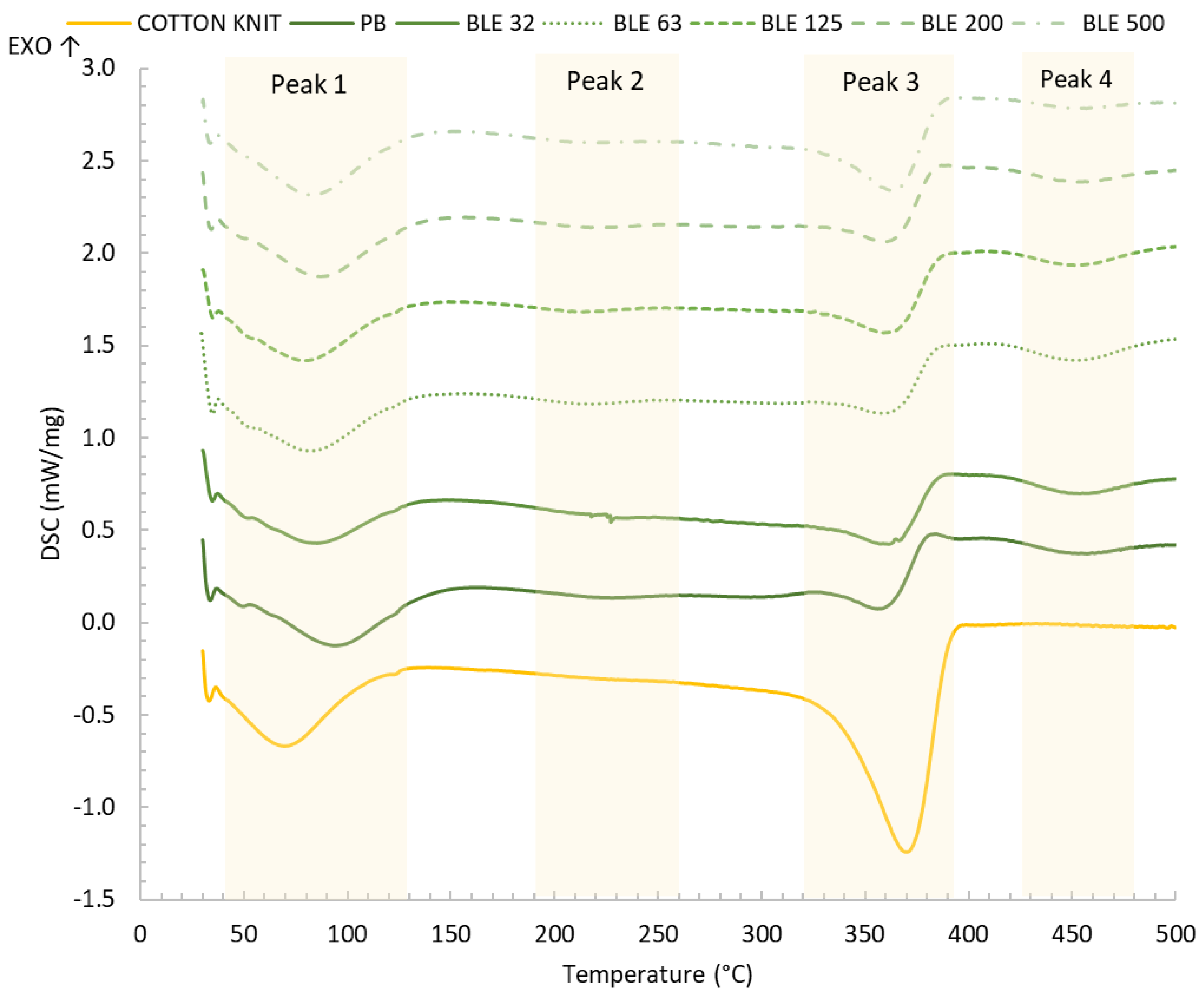

| Samples/Coatings | Peak 1 | Peak 2 | Peak 3 | Peak 4 | ||||

| Temperature (°C) | J/g | Temperature (°C) | J/g | Temperature (°C) | J/g | Temperature (°C) | J/g | |

| Cotton Knitt | 36.9-125.6 (70.2) | -87.8 | -- | -- | 326.7-398.0 (369.7) | -220.3 | -- | -- |

| PB | 55.0 -125.1 (93.9) | -46.8 | 175.1-257.0 (227.3) | -7.8 | 330.7-376.2 (355.9) | -42.2 | 142.9-494.4 (457.1) | -16.8 |

| BLE32 | 54.3-138.8 (85.2) | -45.9 | 180.7-274.6 (227.1) | -7.3 | 321.5-387.3 (361.6) |

-53.0 | 406.8-499.5 (453.3) |

-24.2 |

| BLE63 | 57.4-124.6 (82.5) | -39.0 | 170.8-251.0 (218.4) | -8.2 | 325.1-387.8 (358.8) | -44.7 | 417.3-499.3 (451.4) | -26.4 |

| BLE125 | 57.0-120.9 (78.8) |

-35.2 | 162.1-246.9 (211.8) | -8.5 | 327.7-389.2 (359.2) | -56.1 | 415.7-497.9 (451.2) | -21.3 |

| BLE200 | 52.2-125.6 (87.0) | -53.4 | 162.1-249.7 (221.0) | -7.7 | 325.6-383.5 (359.7) | -52.5 | 413.9-498.8 (453.1) | -17.7 |

| BLE500 | 53.9-122.4 (82.6) | -53.4 | 162.6-254.8 (220.0) | -8.2 | 320.3-389.0 (362.5) | -80.8 | 419.5-494.7 (452.6) | -9.7 |

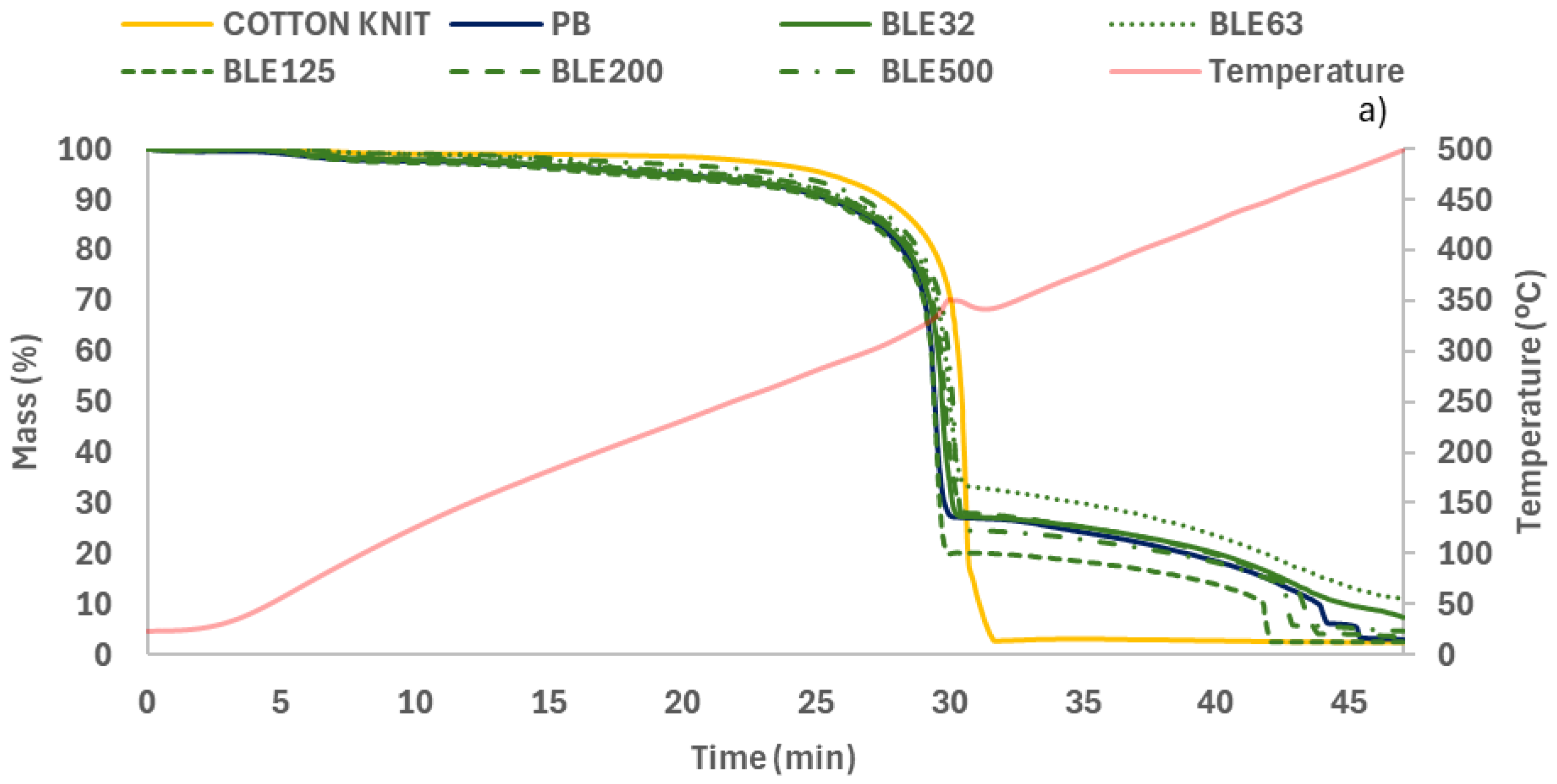

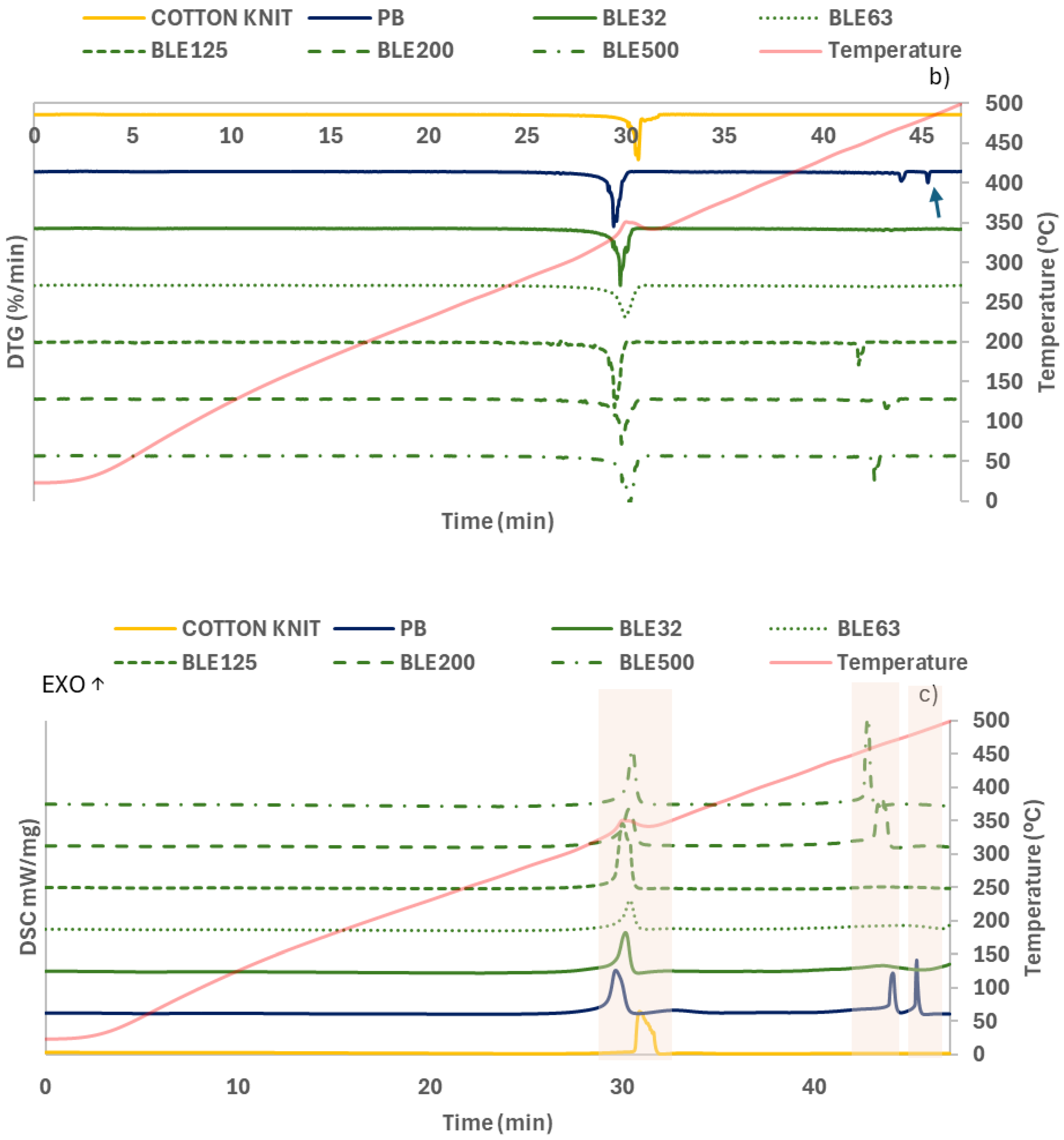

| Cotton Knitt | PB | BLE 32 | BLE 63 | BLE 125 | BLE 200 | BLE 500 | ||

| Peak 1 (°C) | 355.7 | 335.9 | 340.5 | 336.1 | 330.5 | 330.5 | 335.0 | |

| Peak 2 (°C) | -- | 471.0 | 464.3 | -- | 468.2 | 464.3 | 456.6 | |

| Peak 3 (°C) | -- | 484.1 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Temperature (Td 5%) | 285.7 | 225.9 | 221.5 | 243.3 | 230.1 | 246.6 | 269.0 | |

| Temperature (Td 20%) | 325.3 | 315.5 | 317.8 | 318.3 | 313.2 | 316.8 | 318.8 | |

| Temperature (Td 50%) | 345.0 | 340.6 | 340.9 | 337.2 | 327.8 | 331.5 | 333.9 | |

| Temperature (Td 75%) | 357.5 | 370.5 | 379.9 | 420.6 | 330.8 | 381.3 | 342.4 | |

| Residual mass 500 °C (%) | 2.4 | 2.9 | 7.4 | 10.9 | 2.5 | 3.5 | 4.7 | |

| Samples/Coatings | Peak 1 | Peak 2 | Peak 3 | |||

| Temperature (°C) | J/g | Temperature (°C) | J/g | Temperature (°C) | J/g | |

| PB | 283.2-357.6 (355.6) | 1157 | 429.2-474.6 (472.9) | 597.5 | 474.6-487.0 (483.4) | 267.3 |

| BLE32 | 279.9-352.4 (350.2) | 1028 | 403.7-483.5 (465.2) | 380.8 | -- | -- |

| BLE63 | 279.6-347.8 (346.0) | 687.9 | 404.2-495.2 (473.9) | 395.9 | -- | -- |

| BLE125 | 298.6-342.0 (338.2) | 2145 | 427.0-498.9 (465.0) | 288.7 | -- | -- |

| BLE200 | 281.3-349.6 (339.6) | 1004 | 427.6-470.5 (469.5) | 1147 | -- | -- |

| BLE500 | 305.1-345.9 (341.0) | 935.4 | 439.2-463.8 (461.6) | 821.2 | -- | -- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).