1. Introduction

After the breakthrough paper of Aserinski and Kleitman [

1] that described periods of rapid conjugate eye movements occurring during sleep and associated with recall of dream content, the acronym REM (rapid eye movement) was first used by Dement and Kleitman [

2] which also described the cyclic occurrence of REM sleep across the night.

Rapid eye movements (REMs) were initially associated with dreaming, suggesting a relationship between REMs and dream content [

3], REMs were supposed to follow the dream content, “scanning” what was happening in the dream.

Recent data from Andrillon et al. [

4] and Senzai and Scanziani [

5] have revitalized the “scanning hypothesis” by showing a relationship between REMs and brain events associated with waking vision, however the hypothesis that REMs are indicative of visual imagery of the occurring dream is questioned by several observations. Reports of visual dreaming are also evident during NREM sleep and during REM sleep in absence of REMs, thus rapid eye movements do not lie necessarily behind the dreaming process. Differences between the rapid eye movements during wakefulness and those occurring during the REM periods have been highlighted in several studies (see review of Arnulf [

6] and Moskovitz and Berger [

7]). Furthermore, REMs during REM sleep are also present in blind individuals who report no visual dreaming [

8], spontaneous REMs have been found in a hydranencephalic infants where the cortex was presumably absent [

9], and REM behaviors have also been reported in a microcephalic infant [

10], suggesting that cerebral structures are not involved in REMs.

Successive studies have focused on the phenomenology and physiological significance of REMs, also looking at differences of REMs in pathological conditions [

11,

12,

13,

14].

REMs are categorized as expressions of the phasic REM component, characterized by bursts of eye movements, whereas the tonic REM component is characterized by quiescent periods without eye movements [

15]. REM bursting characteristics show a different behavior across the night sleep, bursts in the late REM period tend to be longer and have more REMs compared to bursts in the early REM period [

16].

It has been proposed that the occurrence of REMs is not a random process but could result by the action of a periodic generator [

12,

17]. Aserinsky [

16] reported that eye movements peaked 5-10 minutes after the onset of the REM period and then decreased 10 minutes later. The data also suggested the existence of a cyclic pattern, with REM periods of 40 and 60 min. showing respectively two and three peaks of REM activity. Salzarulo [

18] reported that during a REM phase, frequency of eye movements increases progressively, reaches a peak value at the middle of the phase and decreases at the end, the variations also depend on the length of the phase and its location within the night. Peaks tend to be reached more rapidly in the longest phase.

Differences in neural states between phasic and tonic periods with respect to environmental alertness, spontaneous and evoked cortical activity, information processing have been also suggested (see review Simor et al. [

15]), highlighting the physiological significance of the two components. External information processing appears to be attenuated and cortical activity to be detached from the surrounding environment during periods of phasic activity [

19], whereas environmental alertness is partially maintained during tonic periods [

20,

21].

To characterize REM phasic activity during sleep, different measures have been adopted to monitor the REMs occurrence: “REM activity” defines the number of REMs during a REM period, frequency of REMs is defined as “REM density”, reflecting the relationship between numbers of REMs (REM activity) and REM duration.

Although widely used in early studies, description of REM activity has been later dismissed, to favor REM density as the main index of REM phasic activity.

To further define the significance of rapid eye movements (REMs) during REM sleep, we analyzed the two components tonic and phasic REM, across the sleep period, the REM activity characteristics of the first 5 minutes and of last 5 minutes of REM periods across the sleep period were also assessed, finally we compared the REM activity of REM periods that terminated with transitions to wakefulness with REM periods with transitions to stable sleep (stage 2) or intermediate, light sleep (stage1).

2. Materials and Methods

The study is a retrospective analysis of 7 consecutive days of baseline condition (16 h light, 8 h dark) of 15 healthy volunteers (1 female, 14 males), for a total of 105 sleep records, who participated in a photoperiod study [

22]. The protocol was approved by the NIH intramural research project, and written informed consent were obtained.

Polysomnographic sleep was monitored with a Grass 78 D polygraph, using conventional electrode montage: C3-A2 and C4-A1 EEG channels, left and right EOG and submental EMG. Sleep stages were visually scored according to the criteria of Rechtschaffen and Kales [

23]. A minimal duration of 5 minutes was adopted to define a REM period [

24,

25].

REM activity for each minute of REM sleep was expressed on a 0-8 scale. According to this scale, 0 corresponded to no eye movements, 1, 1-2 EMs; 2, 3-5 EMs; 3, 6-9 EMs; 4, 10-14 EMs; 5, 15-20 EMs; 6, 21-26 EMs; 7, 27-32 EMs; 8, 33 and over EMs [

26].

Following the end of a REM period, three possible conditions were classified: wake: period with transition to stage 0 (wake); intermediate: period with transition to stage 1; sleep: period with transition to stage 2.

Further analyses were conducted on REM activity for the first and last 5 minutes of each REM period.

Tonic epochs were defined as epochs with no EMs or single isolated EMs (epochs 0 or 1 on the activity scale), phasic epochs were defined as epochs with EMs (2-8 on the activity scale).

For each subject, REM variables were averaged over 7 nights for each cycle. A repeated ANOVA was used to compare the factors; types of REM (phasic vs tonic) and rank of cycles (by order of successive occurrence across the night); types of epochs (first 5 minutes vs last five minutes) and rank of cycle.

A one-way ANOVA was used to compare types of transitions (wake, intermediate, sleep) and REM activity (first 5 minutes and last five minutes).

3. Results

REM time and REM density for each night cycle are shown in

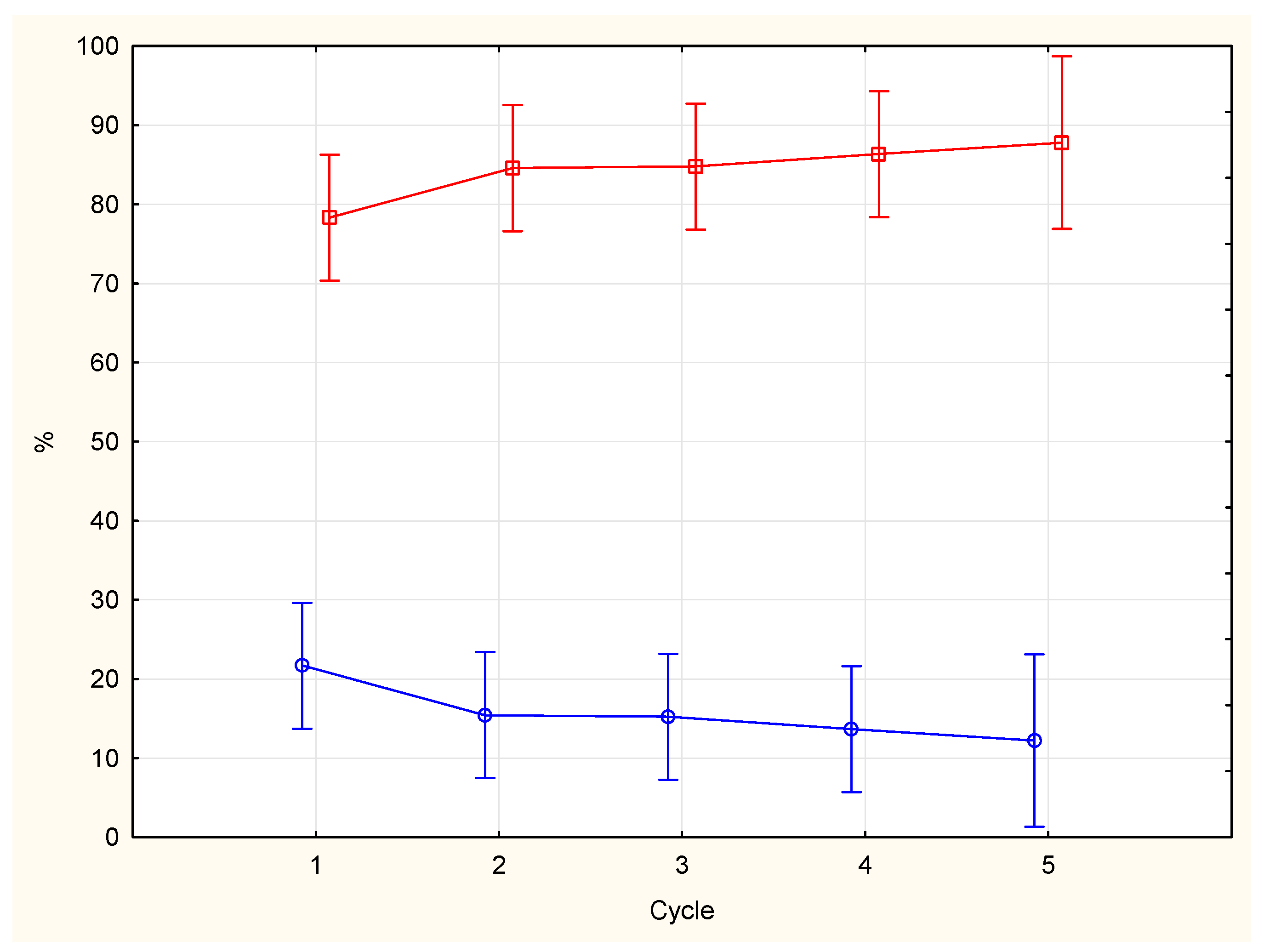

Table 1. Phasic activity was more represented than tonic activity across the whole night period [84.0% (SD=15,31) vs 15,99% (SD=15,31)], F (1,63) =316,4 p=0,000). The percentage of phasic activity showed a modest increasing trend towards the end of the night, the opposite trend was observed for the percentage of tonic activity, with more tonic epochs in the first cycle (

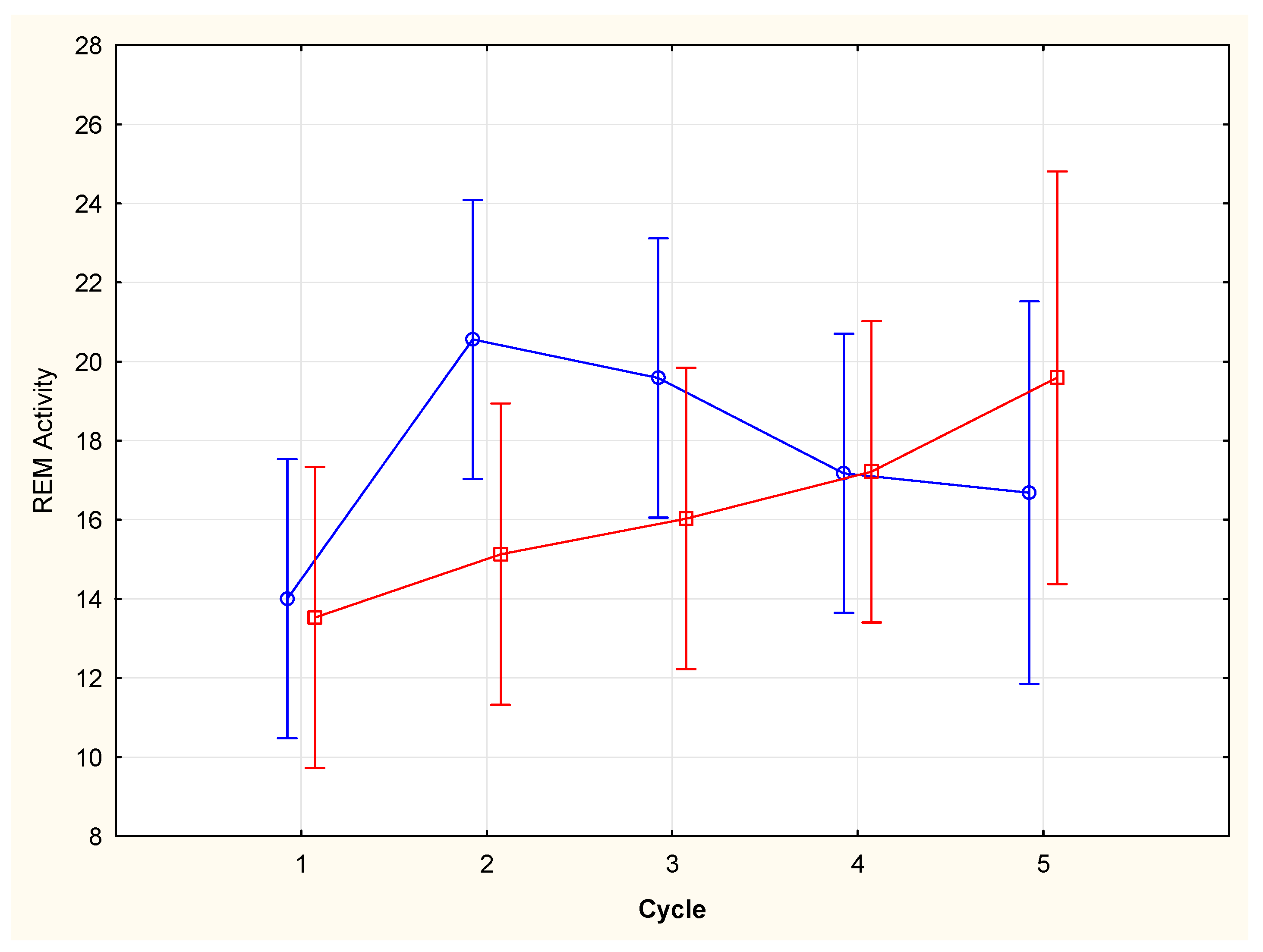

Figure 1), however the respective percentages of phasic epochs and that of tonic epochs did not show significant differences across the night (F(4,63) =0,73163, p=0,57377). REM activity during the first and last five minutes of a REM period showed a different behavior during the night (

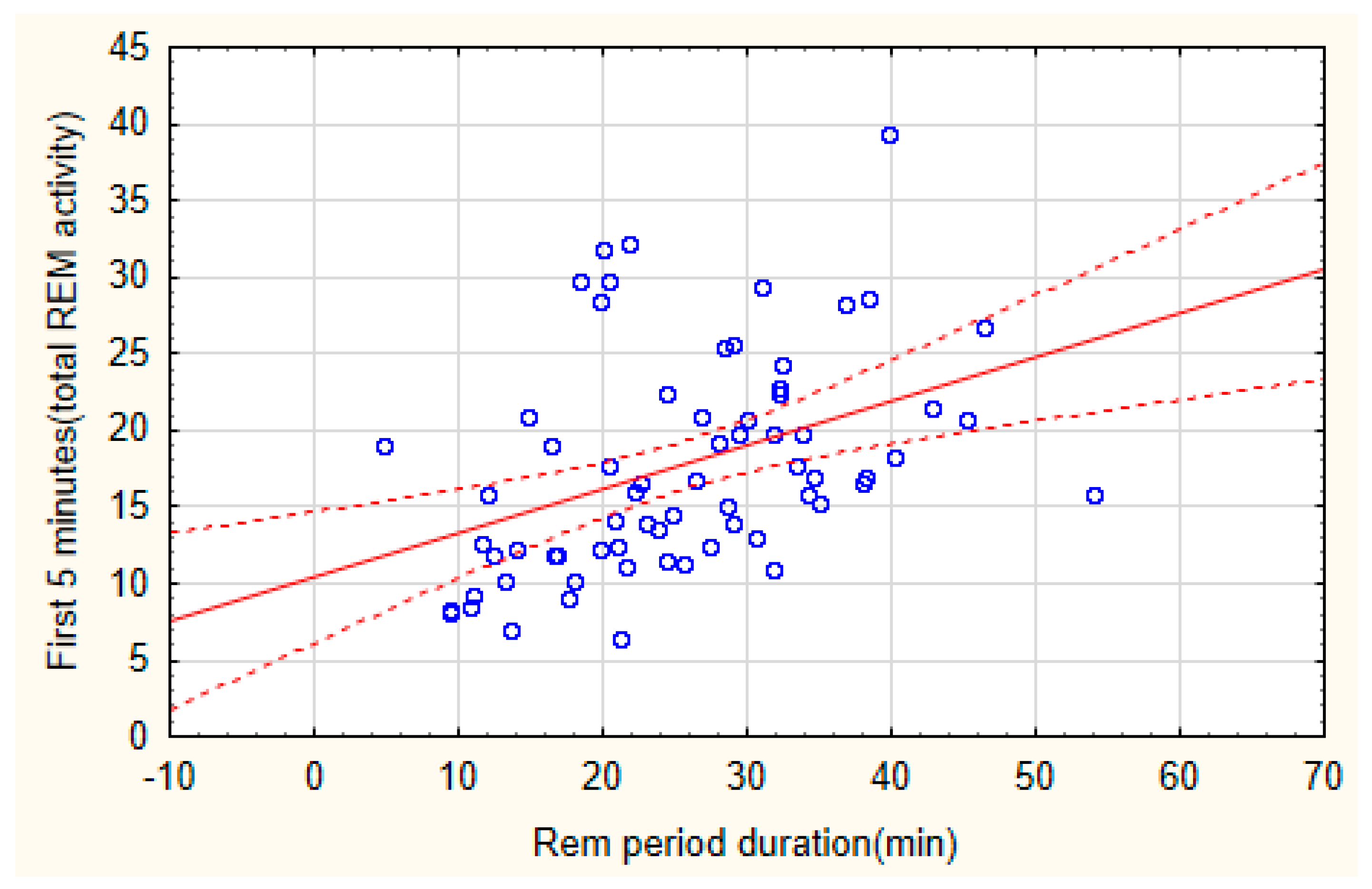

Figure 2), higher REM activity in the first 5 minutes of the REM period were found in the second and third cycle, whereas higher REM activity in the last five minutes of the REM period was found in the fifth cycle (cycle X condition, F (4,63)=2,91, p=0,028), with a progressive increasing trend throughout the night period. A significant correlation was found between the activity of the first 5 minutes of the REM period and the total duration of the REM period (Spearman rank order correlation: n=68, R= 0,4819 t=4.46, p=0.000032)(

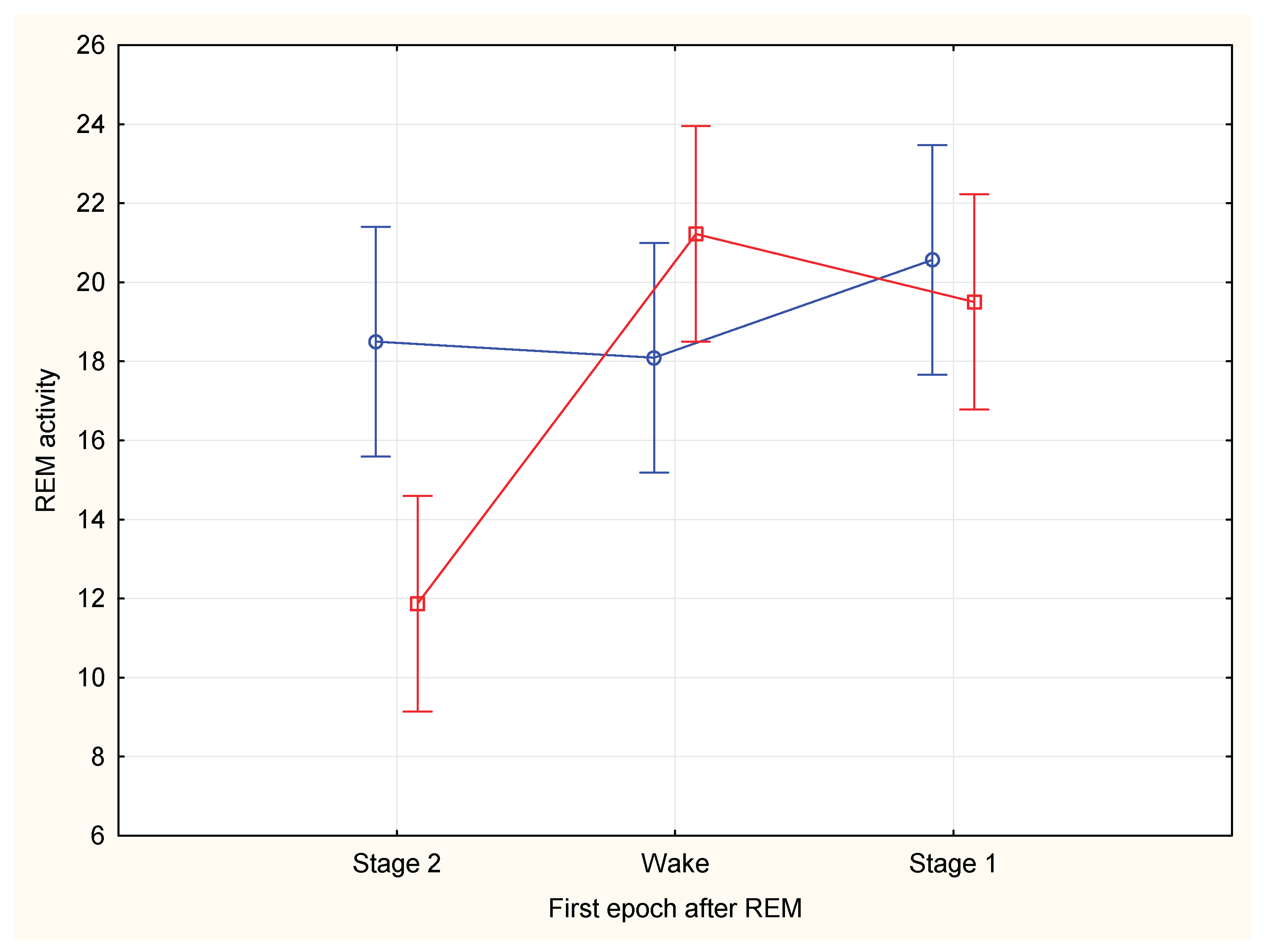

Figure 3), no significant correlation was found between the activity of the last five minutes of REM period and the total duration of the REM period (Spearman rank correlation N=68, R=0,1224,t=1.00, p=0,3199). The REM density was not significantly different for REM periods with transition to wake or to stage 1 or to stage 2 ( F(2, 42)=1,7305, p=,18959). Total REM activity was not significantly different for REM periods with transition to wake or to stage 1 or to stage 2 (Current effect: F (2, 42)=2,8034, p=,07197). REM activity during the first five minutes of the REM period was not significantly different for REM periods with transition to wake or to stage 1 or to stage 2 (F(2, 42)=0,85214, p=0,43374), REM activity during the last five minutes of the REM period was significantly different for REM periods with transition to wake or stage 1 compared to periods with transition to stage 2 (F(2, 42)=13,589, p=,00003); wake vs stage 2 (21,22 vs 11,87, F(1, 28)=26,400, p=0,00002; wake vs stage 1 (21,22 vs 19,50, F(1, 28)=0,60670, p=0,44257); stage 1 vs stage2 ( 19,50 vs 11,87, F(1, 28)=21,170, p=0,00008) (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

In his “Harvey Lecture”, Giuseppe Moruzzi stated: “(…) Summing up, a distinction between underlying tonic changes and phasic outbursts is likely to be useful in any attempt to unveil – trough more refined and more complete electrophysiological and behavioral analysis – the basic nature and the functional significance of sleep “[

27].

The significance of phasic REM activity during REM sleep is not well understood, also it is not clear if the frequency of REMs (REM density) can be considered a measure of the intensity of REM sleep. After selective REM deprivation, increased pressure for REM in the recovery night is manifested by a decreased REM latency and increased REM percent, but not by an increased REM density, which instead is reduced. [

28].

Increased REM percent and REM density have been reported in depression and considered, together with shortened REM latency, index of increased propensity (and/or pressure) for. REM sleep in this clinical condition.

Different mechanisms appear to regulate REM occurrence and its duration, and REM density. REM sleep time is controlled by short- and long-term homeostatic regulations [

29,

30,

31], and by a definite circadian modulation which coincides with the body temperature minimum [

32,

33], REM density increases as a function of time in consecutive sleep cycles, opposite to the decreasing NREM sleep pressure, and it has been associated with arousal during sleep [

34,

35,

36,

37], it also presents a circadian modulation independent from the circadian modulation of REM sleep, the REM density peak occur earlier in the circadian cycle [

38].

A critical aspect in assessing significance and regulation of phasic REM is the lack of univocal and consistent methodologies used. REM density has been reported in several ways, with no consensus on a definite and reproducible way to measure it. Most studies measures REM density as the relationship between the total REM activity (number of REMs) and the duration of the REM period. Other studies have instead considered REM density as the percentage of REM epochs with REMs (number of intervals that contained REMs).

As well as, due to difficulties counting the large number of REMs that occur during a time unit, REM activity is mostly measured, using the Pittsburgh method, on a 9 points scale from 0 (no EMs) to 8 (more than 33 EMs) [

26].

Few studies have adopted automatically measured scoring of REMs [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. Automated analyses have also proposed different parameters, like EM frequency and EM rotation with speed and energy, showing a different behavior of the REMs across the night compared to traditional measures, with an inverted V pattern and higher EM rotation in the second cycle [

39], and suggested fluctuation at a periodicity of about 2 min that may relate to rhythmic component of the REM generating mechanisms [

40].

In our study, tonic and phasic epochs did not show peculiar behavior, epochs with bursts of eye movements were more frequent across the whole night compared to the tonic epochs, but neither the tonic nor phasic epochs were significantly prevalent in a defined cycle.

Previous data on the behavior of REMs during the REM period have shown different results. According to Aserinsky [

16] total numbers of REMs are similar in both halves of a REM period, whereas for Petre-Quadens [

44] number of REMs tends to increase from the beginning to the midpart, then to decrease toward the end. We found thar the REM activity during the first and last five minutes of a REM period were different according to the sequence of the cycles across the night. The first five minutes of a REM period showed higher number of REMs in the second and third cycle, whereas in the last five minutes of the REM period REMs were higher in the fifth cycle, showing also an increasing trend across the night, Interestingly, the activity in the first five minutes appeared to predict the length of the whole REM period, higher activity leading to a longer period, consistent with early observations of Salzarulo [

18] who reported that peaks of EM density tend to be reached more rapidly in the longest phases, a data which suggests a possible relationship between the systems that control the phasic activity and those controlling the duration of the REM period. Considering that REM sleep and slow wave sleep can be competing variables within sleep [

29,

45,

46], higher REM activity at the beginning of a REM period can express a higher REM propensity that would lead to a longer duration of the period.

The higher activity of the last five minutes was associated with transitions to epochs of stage 1 or wake, consistent with previous data of a relationship of increased REM density with transition to wake in extended sleep [

25]. It has been suggested that REM density can be related to arousal during sleep [

37], REM activity at the end of the REM period can possibly reflect a decrease of sleep pressure, leading the transition to a lighter sleep phase and/or to wake.

According to our results, the analysis of REM activity and the focus on segments of a REM period, could provide more information on REM phasic activity than those obtained with REM density, which is limited to the whole REM period and could “dilute” the possible significance of phasic activity.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.B. and T.A.W.; methodology, G.B. and T.A.W.; formal analysis, G.B; writing—original draft preparation, G.B.; writing—review and editing, G.B. and T.A.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institutional human research committee of the Intramural Program of the National Institute of Mental Health, and all subjects gave informed consent after the nature and possible consequences of the experiment were fully explained.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Aserinsky, E.; Kleitman, N. Regularly occurring periods of eye motility, and concomitant phenomena, during sleep. Science 1953, 118, 273-274. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dement, W.C.; Kleitman. N. Cyclic variations in EEG during sleep and their relation to eye movements, body motility, and dreaming. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1957, 9: 673-690. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roffwarg, H.P.; Dement, W.C.; Muzio, J.N.; Fisher, C. Dream imagery: relationship to rapid eye movements of sleep. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1962 7, 235-258. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrillon, T.; Nir, Y,; Cirelli, C.; Tononi, G.; Fried, I. Single-neuron activity and eye movements during human REM sleep and awake vision. Nat Commun. 2015 6, 7884. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Senzai, Y.; Scanziani, M. A cognitive process occurring during sleep is revealed by rapid eye movements. Science 2022, 377, 999-1004. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnulf, I. The 'scanning hypothesis' of rapid eye movements during REM sleep: a review of the evidence. Arch Ital Biol. 2011, 149, 367-382. Epub 2011 Dec 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moskowitz, E.; Berger, R.J. Rapid eye movements and dream imagery: are they related? Nature 1969, 224, 613-614. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, N.H. ; Foulkes, D.; Schmidt, M. The structure of laboratory dream reports in blind and sighted subjects. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1982 170, 286-294. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, C.M.; Mathis, J.L.; Jabbour, J.T. Dream patterns in narcoleptic and hydranencephalic patients. Am J Psychiatry 1965, 122, 402-404. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmon, R.J.; Emde, R.N. Spontaneous REM behaviors in a microcephalic infant. Percept Mot Skills 1972, 34, 827-833. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benoit, O.; Parot, S.; Garma, L. Evolution during the night of REM sleep in man. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology 1974, 36, 245-251. ISSN 0013-4694. [CrossRef]

- Lavie, P. Rapid eye movements in REM sleep--more evidence for a periodic organization. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1979, 46,683-688. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feinberg, I. Sleep electroencephalographic and eye-movement patterns in patients with schizophrenia and with chronic brain syndrome. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis. 1967, 45, 211-240. [PubMed]

- Kupfer, D.J.; Heninger, G.R. REM activity as a correlate of mood changes throughout the night. Electroencephalographic sleep patterns in a patient with a 48-hour cyclic mood disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1972, 27, 368-373. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simor, P.; van der Wijk, G.; Nobili, L.; Peigneux, P. The microstructure of REM sleep: Why phasic and tonic? Sleep Med Rev. 2020, 52, 101305. Epub 2020 Mar 19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aserinsky, E. Rapid eye movement density and pattern in the sleep of normal young adults. Psychophysiology. 1971 8, 361-375. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krynicki, V. Time trends and periodic cycles in REM sleep eye movements. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1975 39, 507-513. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salzarulo, P. Variations with time of the quantity of eye movements during fast sleep in man. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1972, 32, 409-416. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, L.J.; Kremen, I. Variations in behavioral response threshold within the REM period of human sleep. Psychophysiology. 1980 , 17, 133-140. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ermis, U.; Krakow, K.; Voss, U. Arousal thresholds during human tonic and phasic REM sleep. J Sleep Res. 2010, 19,400-406. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehrle, R.; Kaufmann, C.; Wetter, T.C.; Holsboer, F.; Auer, D.P.; Pollmächer, T.; Czisch, M. Functional microstates within human REM sleep: first evidence from fMRI of a thalamocortical network specific for phasic REM periods. Eur J Neurosci. 2007 , 25, 863-871. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehr, T.A.; Moul, D.E.; Barbato, G.; Giesen, H.A.; Seidel, J.A.; Barker, C.; Bender, C. Conservation of photoperiod-responsive mechanisms in humans. Am J Physiol. 1993, 265, R846-R857. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rechtschaffen, A.; Kales, A. (Eds)A Manual of Standardized Terminology, Techniques and Scoring System for Sleep Stages of Human Subjects. Public Health Service, US Government Printing Office, Washington DC.1968.

- Dijk, D.J.; Brunner, D.P.; Borbély, A.A. Time course of EEG power density during long sleep in humans. Am J Physiol. 1990 258, R650-R661. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbato G, Barker C, Bender C, Giesen HA, Wehr TA. Extended sleep in humans in 14 hour nights (LD 10:14): relationship between REM density and spontaneous awakening. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1994 Apr;90(4):291-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buysse, D.J,; Kupfer, D.J. Diagnostic and research applications of electroencephalographic sleep studies in depression. Conceptual and methodological issues. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1990, 178, 405-414. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moruzzi G. Active processes in the brain stem during sleep. Harvey Lect 1963, 58, 233-297. [PubMed]

- Antonioli, M.; Solano, L.; Torre, A.; Violani, C,; Costa, M.; Bertini, M. Independence of REM density from other REM sleep parameters before and after REM deprivation. Sleep 1981, 4, 221-225. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbato, G,; Wehr, T.A. Homeostatic regulation of REM sleep in humans during extended sleep. Sleep, 1998 21, 267-276. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franken P. Long-term vs. short-term processes regulating REM sleep. J Sleep Res. 2002 11, 17-28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franken, P.; Dijk, D.J. Sleep and circadian rhythmicity as entangled processes serving homeostasis. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2024, 25, 43-59. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czeisler, C.A.; Zimmerman, J.C.; Ronda, J.M.; Moore-Ede, M.C.; Weitzman, E.D. Timing of REM sleep is coupled to the circadian rhythm of body temperature in man. Sleep 1980, 2, 329-246. [PubMed]

- Zulley, J. Distribution of REM sleep in entrained 24 hour and free-running sleep--wake cycles. Sleep 1980, 2, 377-389. [PubMed]

- Aserinsky, E. The maximal capacity for sleep: rapid eye movement density as an index of sleep satiety. Biol Psychiatry 1969, 1, 147-159. [PubMed]

- Feinberg, I.; Baker, T.; Leder, R.; March, J.D. Response of delta (0-3 Hz) EEG and eye movement density to a night with 100 minutes of sleep. Sleep 1988, 11, 473-487. [PubMed]

- Barbato, G.; Barker, C.; Bender C.; Wehr, T.A. Spontaneous sleep interruptions during extended nights. Relationships with NREM and REM sleep phases and effects on REM sleep regulation. Clin Neurophysiol. 2002, 113, 892-900. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbato G. Is REM Density a Measure of Arousal during Sleep? Brain Sci. 2023 Feb 21;13(3):378. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khalsa, S.B.; Conroy, D.A.; Duffy, J.F.; Czeisler, C.A.; Dijk, D.J. Sleep- and circadian-dependent modulation of REM density. J Sleep Res. 2002. 11, 53-59. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, K; Atsumi, Y. Precise measurement of individual rapid eye movements in REM sleep of humans. Sleep. 1997 20, 743-752. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ktonas, P.; Nygren, A-; Frost, J. Jr. Two-minute rapid eye movement (REM) density fluctuations in human REM sleep. Neurosci Lett. 2003, 353,161-164. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, J.A.E.; Kempfner, L.; Leonthin, H.L.; Hvidtfelt, M.; Nikolic, M.; Kornum, B.R.; Jennum, P. Novel method for evaluation of eye movements in patients with narcolepsy. Sleep Med. 2017, 33,171-180. Epub 2016 Dec 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yetton, B.D.; Niknazar, M.; Duggan, K.A.; McDevitt, E.A.; Whitehurst, L.N.; Sattari, N.; Mednick, S.C. Automatic detection of rapid eye movements (REMs): A machine learning approach. J Neurosci Methods. 2016, 259, 72-82. Epub 2015 Nov 28. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Agarwal, R.; Takeuchi, T.; Laroche, S.; Gotman, J. Detection of rapid-eye movements in sleep studies. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2005 52, 1390-1396. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petre-Quadens, O; De Lee, C. Eye-movements during sleep: a common criterion of learning capacities and endocrine activity. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1970 12, 730-740. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carskadon, M.A; Dement, W.C. Sleep studies on a 90-minute day. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1975 39, 145-155. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, WC.; Barbato, G.; Fagioli, I.; Garcia-Borreguero, D.; Wehr, T.A. A biphasic daily pattern of slow wave activity during a two-day 90-minute sleep wake schedule. Arch Ital Biol. 2009 147, 117-130. [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).