Submitted:

15 May 2025

Posted:

16 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

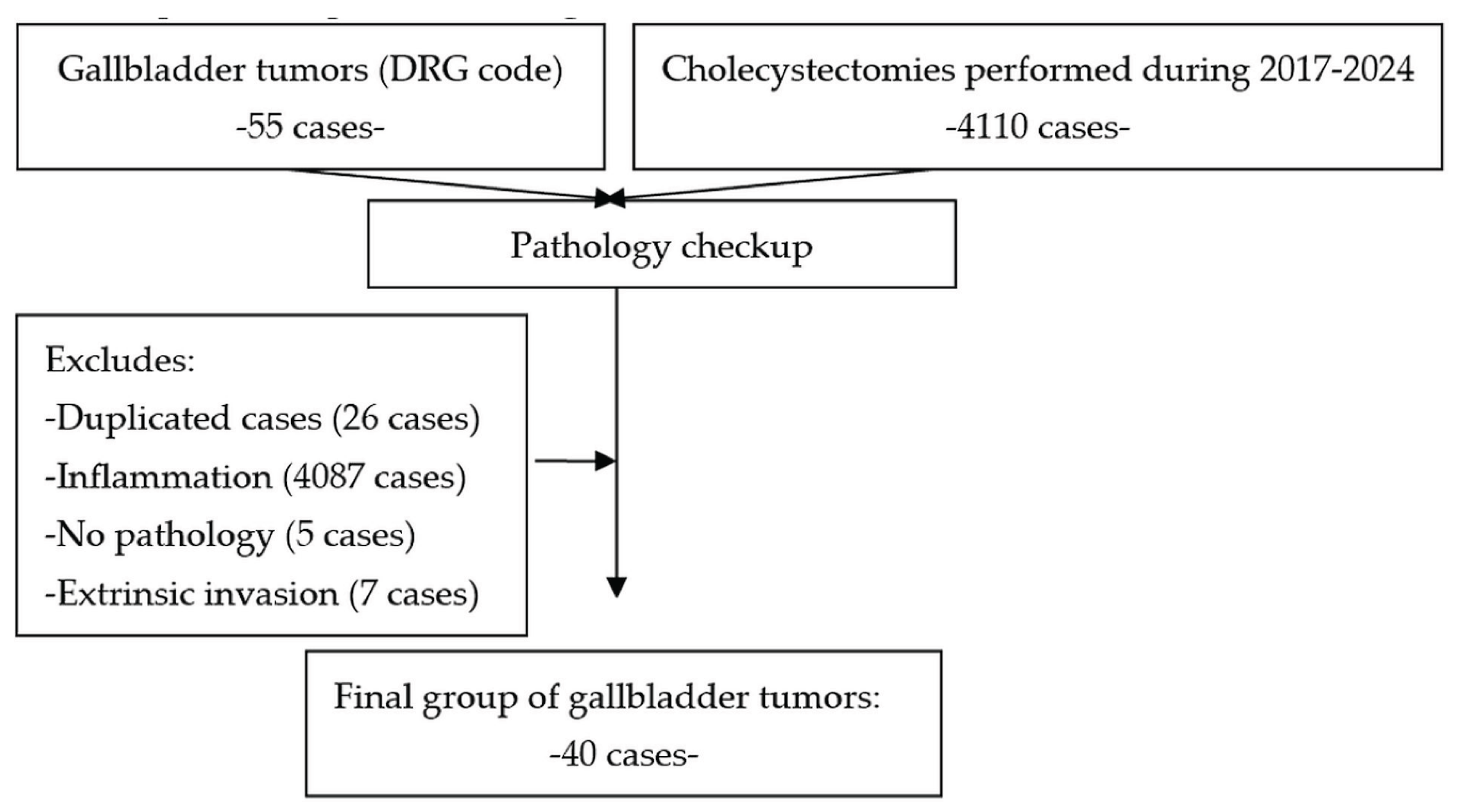

2.1. Patient Selection

2.2. Statistical analysis

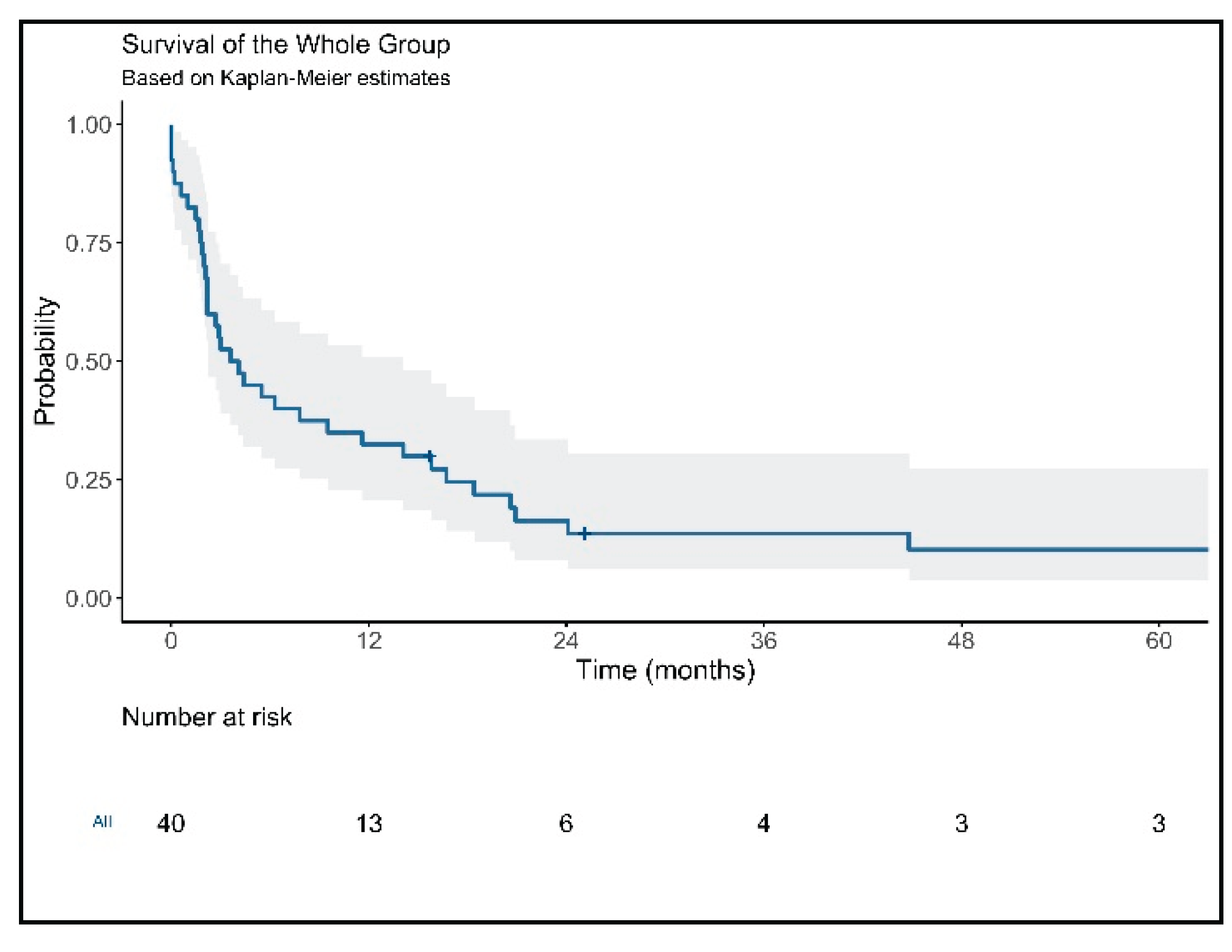

3. Results

Main Characteristics of Patients

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pavlidis, E.T.; Galanis, I.N.; Pavlidis, T.E. New trends in diagnosis and management of gallbladder carcinoma. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2024, 16, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, A.N.; Jain, S.; Dixit, R. Gallbladder carcinoma: Aggressive malignancy with protean loco-regional and distant spread. World J Clin Cases. 2015, 3, 231–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, W.; Liu, F.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J. Research progress on prognostic factors of gallbladder carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2024, 150, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inui, K.; Yoshino, J.; Miyoshi, H. Diagnosis of gallbladder tumors. Intern Med. 2011, 50, 1133–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetze, T.O. Gallbladder carcinoma: Prognostic factors and therapeutic options. World J Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 12211–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, T.R.; Wang, J.K.; Li, F.Y.; Hu, H.J. Prognostic factors for resected cases with gallbladder carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2024, 110, 4342–4355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayabe, R.I.; Wach, M.M.; Ruff, S.M.; Diggs, L.P.; Martin, S.P.; Wiemken, T.; Hinyard, L.; Davis, J.L.; Luu, C.; Hernandez, J.M. Gallbladder squamous cell carcinoma: An analysis of 1084 cases from the National Cancer Database. J Surg Oncol. 2020, 122, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murimwa G, Hester C, Mansour JC, Polanco PM, Porembka MR, Wang SC, Zeh HJ Jr, Yopp AC. Comparative Outcomes of Adenosquamous Carcinoma of the Gallbladder: an Analysis of the National Cancer Database. J Gastrointest Surg. 2021, 25, 1815–1827. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, M.; Ma, B.; Ma, X. Potential role of contrast-enhanced ultrasound for the differentiation of malignant and benign gallbladder lesions in East Asia: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018, 97, e11808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.P.; Bai, M.; Gu, J.Y.; He, Y.Q.; Qiao, X.H.; Du, L.F. Value of contrast-enhanced ultrasound in the differential diagnosis of gallbladder lesions. World J Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocalteu, A.; Iordache, S.; Cazacu, S.M.; Urhut, C.M.; Sandulescu, S.M.; Ciurea, A.M.; Saftoiu, A.; Sandulescu, L.D. Role of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography in Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Using LI-RADS and Ancillary Features: A Single Tertiary Centre Experience. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021, 11, 2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urhuț, M.C.; Săndulescu, L.D.; Streba, C.T.; Mămuleanu, M.; Ciocâlteu, A.; Cazacu, S.M.; Dănoiu, S. Diagnostic Performance of an Artificial Intelligence Model Based on Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound in Patients with Liver Lesions: A Comparative Study with Clinicians. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023, 13, 3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstenmaier, J.F.; Hoang, K.N.; Gibson, R.N. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound in gallbladder disease: a pictorial review. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2016, 41, 1640–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jinawath, A.; Akiyama, Y.; Yuasa, Y.; Pairojkul, C. Expression of phosphorylated ERK1/2 and homeodomain protein CDX2 in cholangiocarcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2006, 132, 805–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.S.; Akiyama, Y.; Igari, T.; Kawamura, T.; Hiranuma, S.; Shibata, T.; Tsuruta, K.; Koike, M.; Arii, S.; Yuasa, Y. Expression of homeodomain protein CDX2 in gallbladder carcinomas. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2005, 131, 271–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.L.; Yang, Z.L.; Liu, J.Q.; Miao, X.Y. Expression of CDX2 and hepatocyte antigen in benign and malignant lesions of gallbladder and its correlation with histopathologic type and clinical outcome. Pathol Oncol Res. 2011, 17, 561–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.T.; Hsu, C.; Jeng, Y.M.; Chang, M.C.; Wei, S.C.; Wong, J.M. Expression of the caudal-type homeodomain transcription factor CDX2 is related to clinical outcome in biliary tract carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007, 22, 389–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graur, F.; Mois, E.; Margarit, S.; Hagiu, C.; Al Hajjar, N. Gallbladder carcinoma. Surgical management of gallbladder carcinoma. An analysis of 37 cases. Ann Ital Chir. 2018, 89, 501–506. [Google Scholar]

- Vlad, L.; Osian, G.; Iancu, C.; Munteanu, D.; Mirică, A.; Furcea, L. Gallbladder carcinoma. A clinical study of a series of 38 cases. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2003, 12, 199–202 PMID: 14502320. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Neculoiu, D.; Neculoiu, L.C.; Popa, R.M.; Manea, R.M. The Many Hidden Faces of Gallbladder Carcinoma on CT and MRI Imaging-From A to Z. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024, 14, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin, A.; Achim, F.; Turcu, T.; Birceanu, A.; Evsei, A.; Socea, B.; Predescu, D. Giant Gallbladder Tumor, Unusual Cancer-Case Report and Short Review of Literature. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023, 13, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiorean, L.; Bartos, A.; Pelau, D.; Iancu, D.; Ciuleanu, T.; Buiga, R.; Oancea, I.; Mangrau, A.; Iancu, C.; Badea, R. Neuroendocrine tumor of gallbladder with liver and retroperitoneal metastases and a good response to the chemotherapeutical treatment. J Med Ultrason (2001). 2015, 42, 271–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

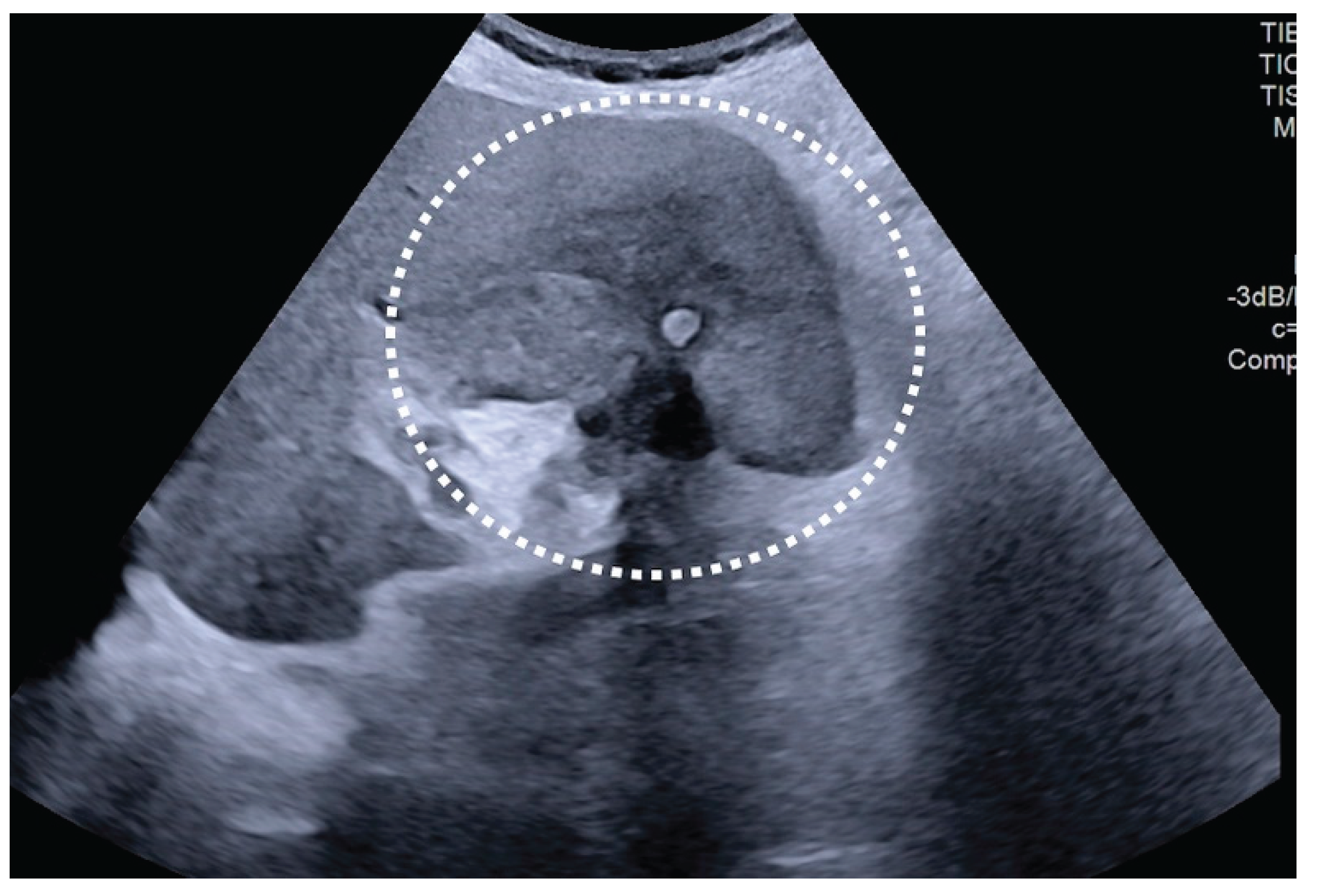

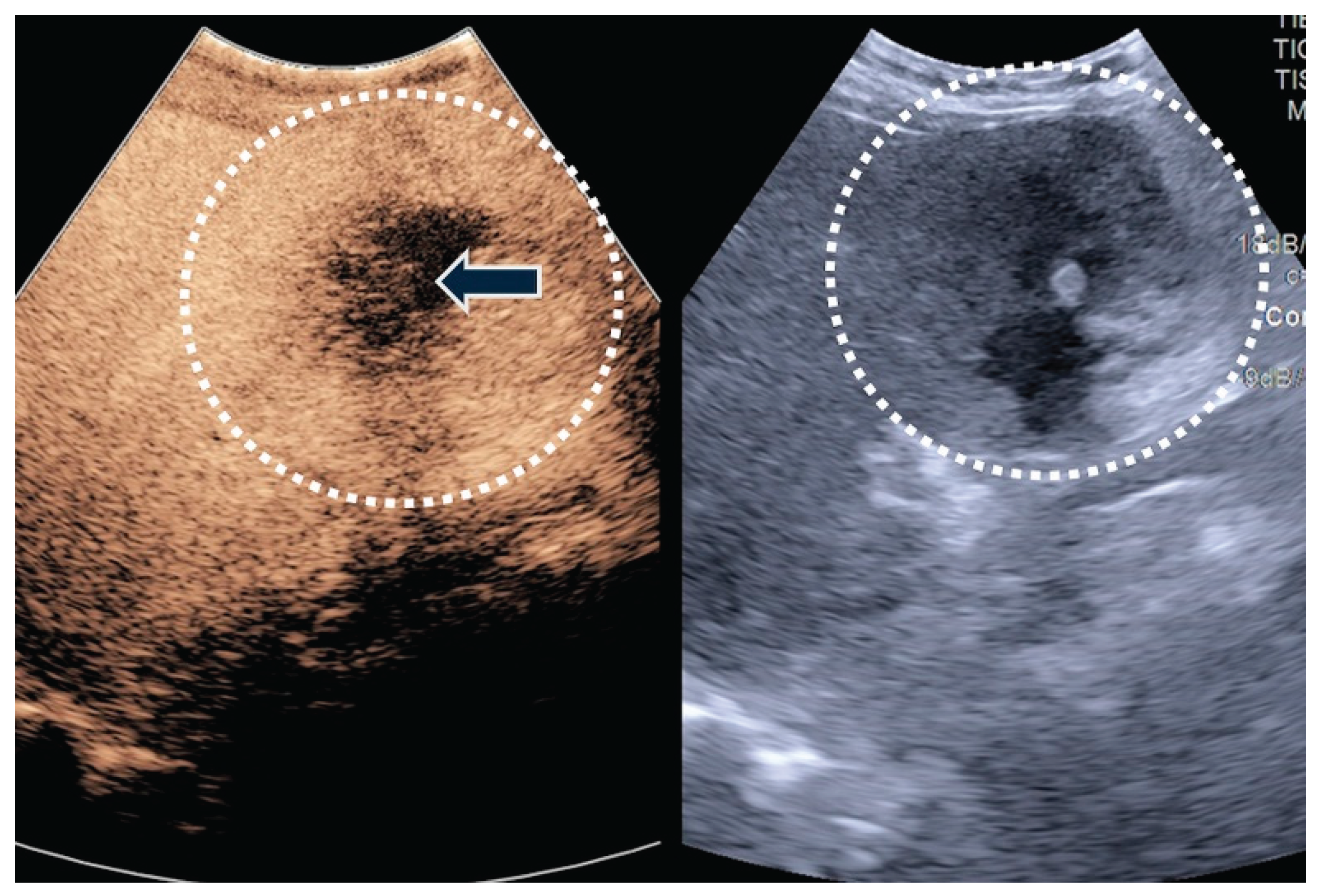

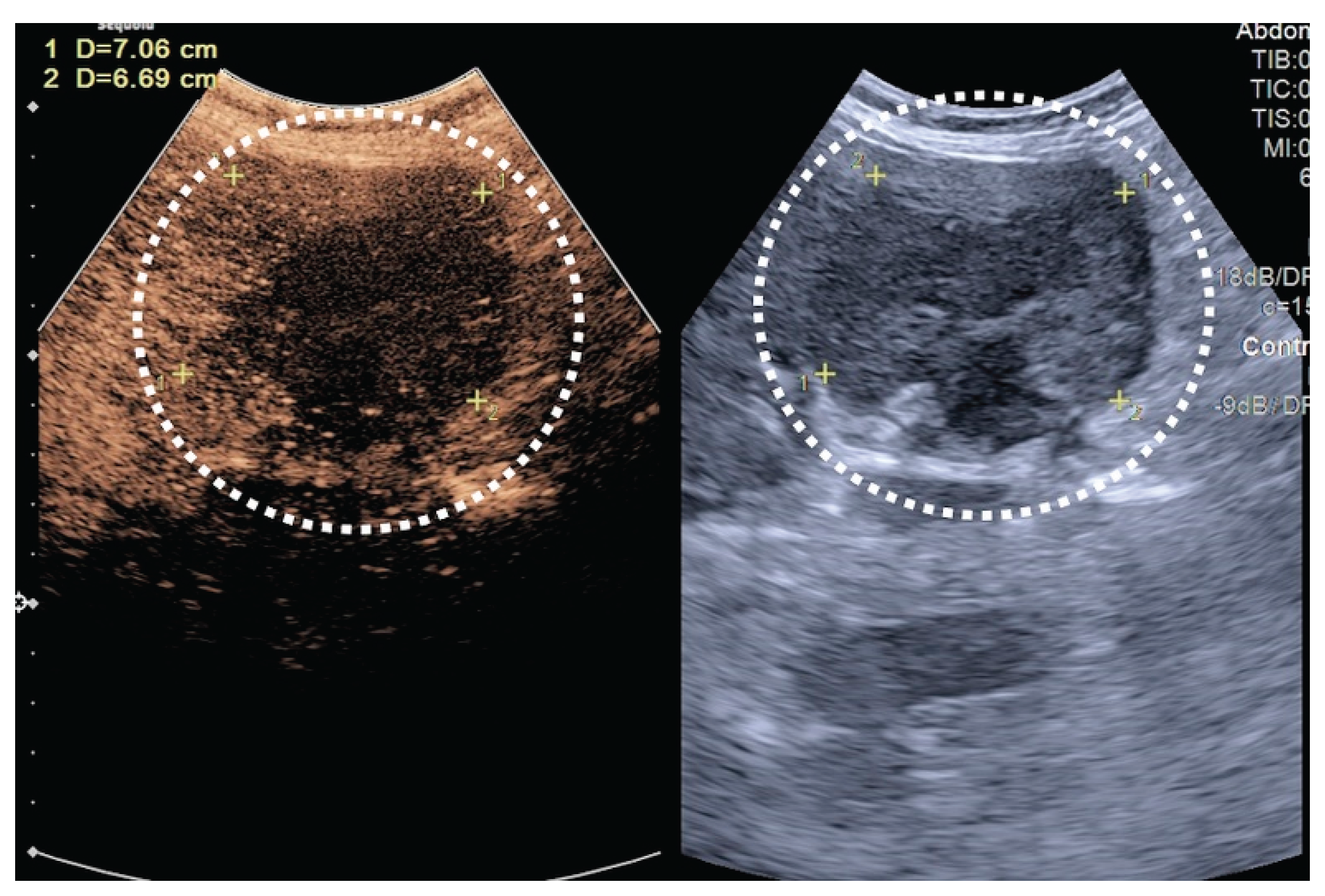

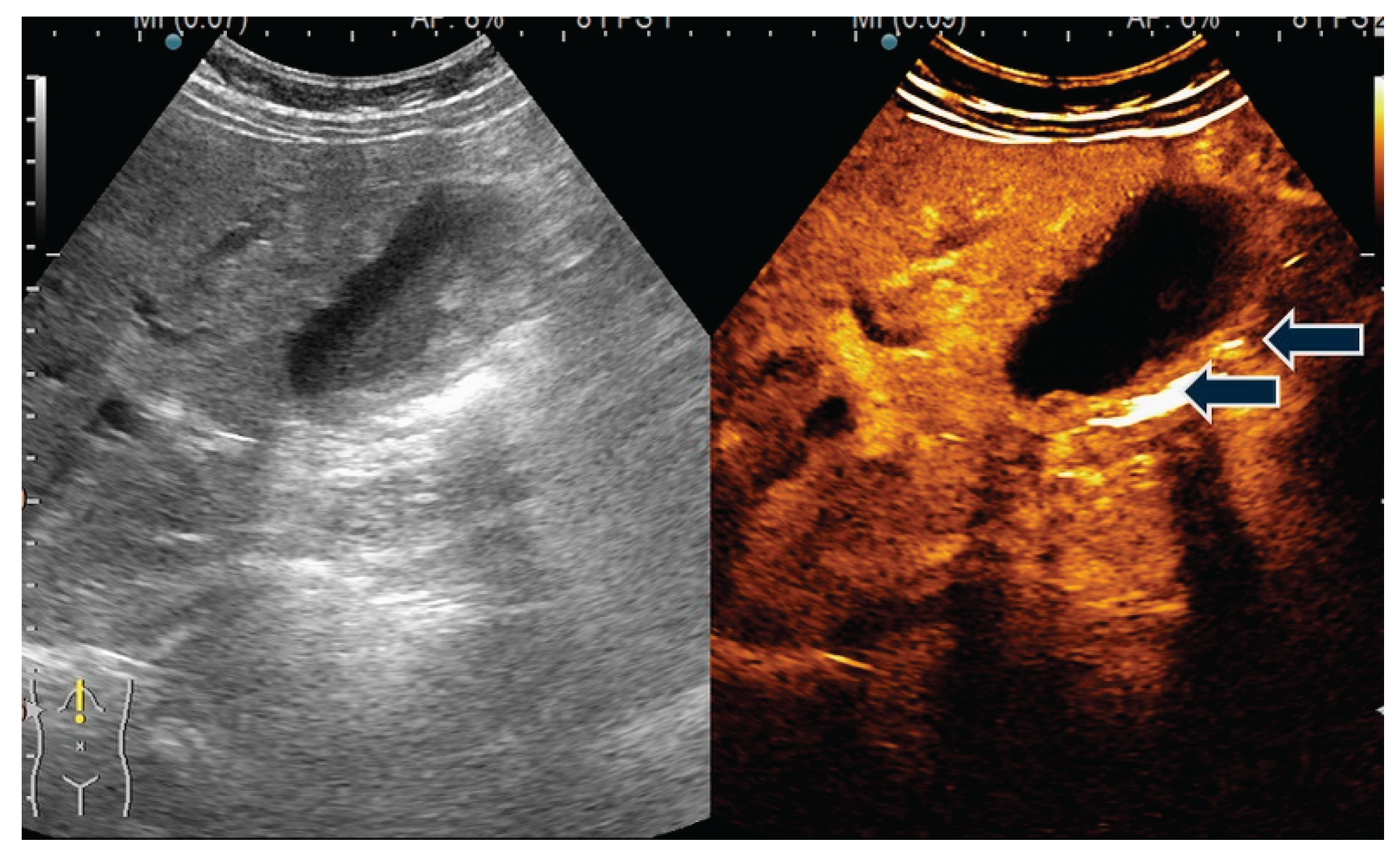

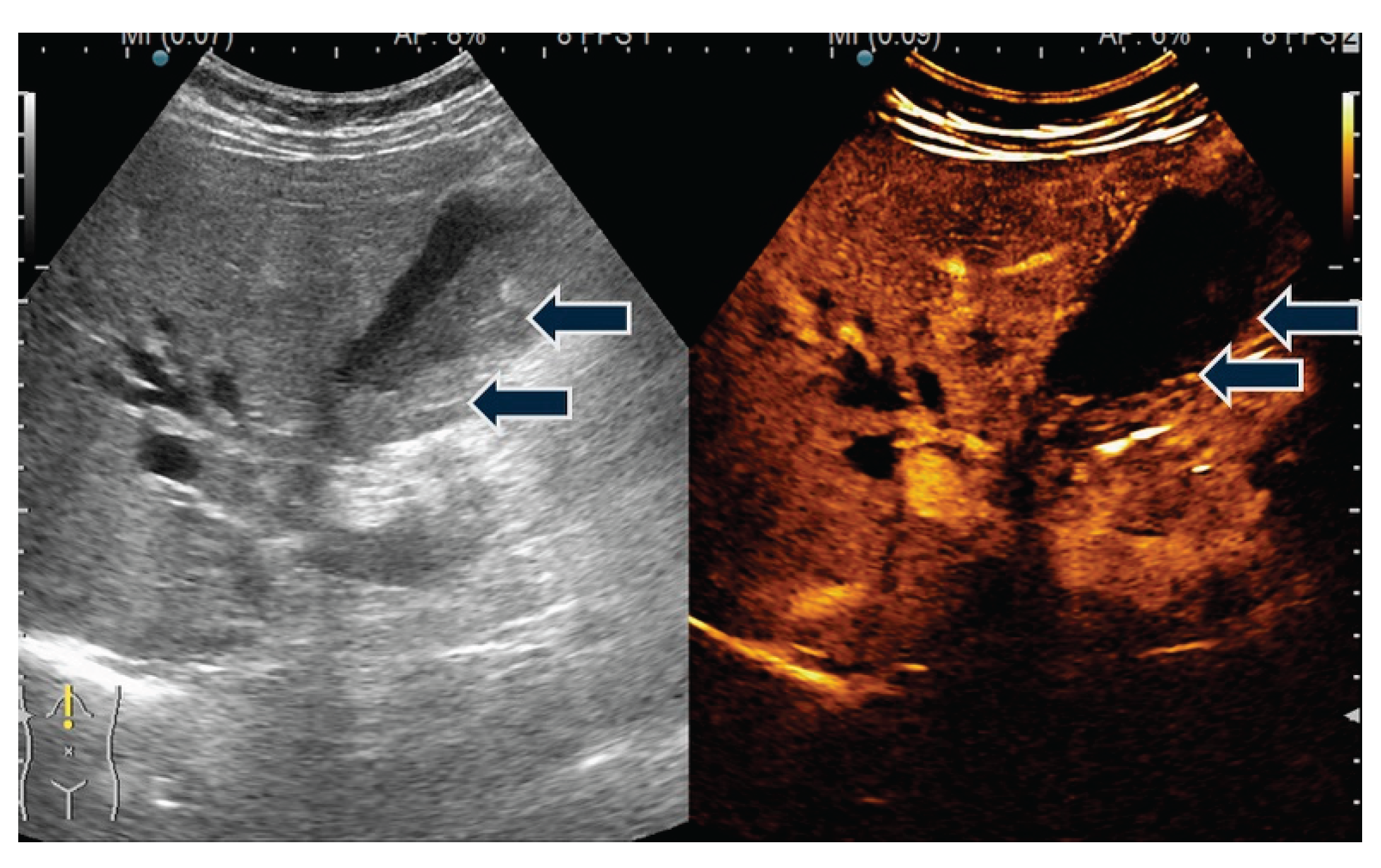

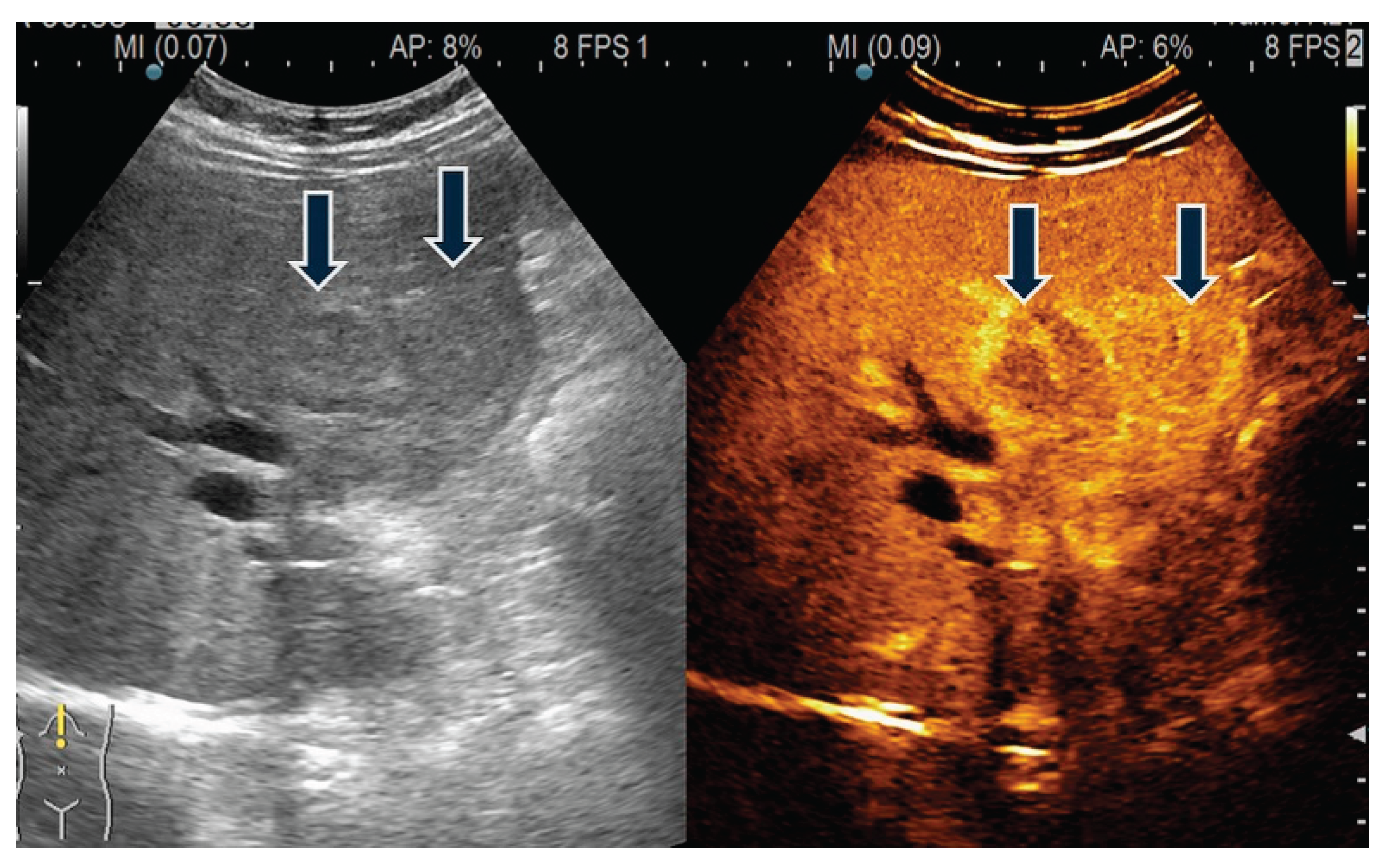

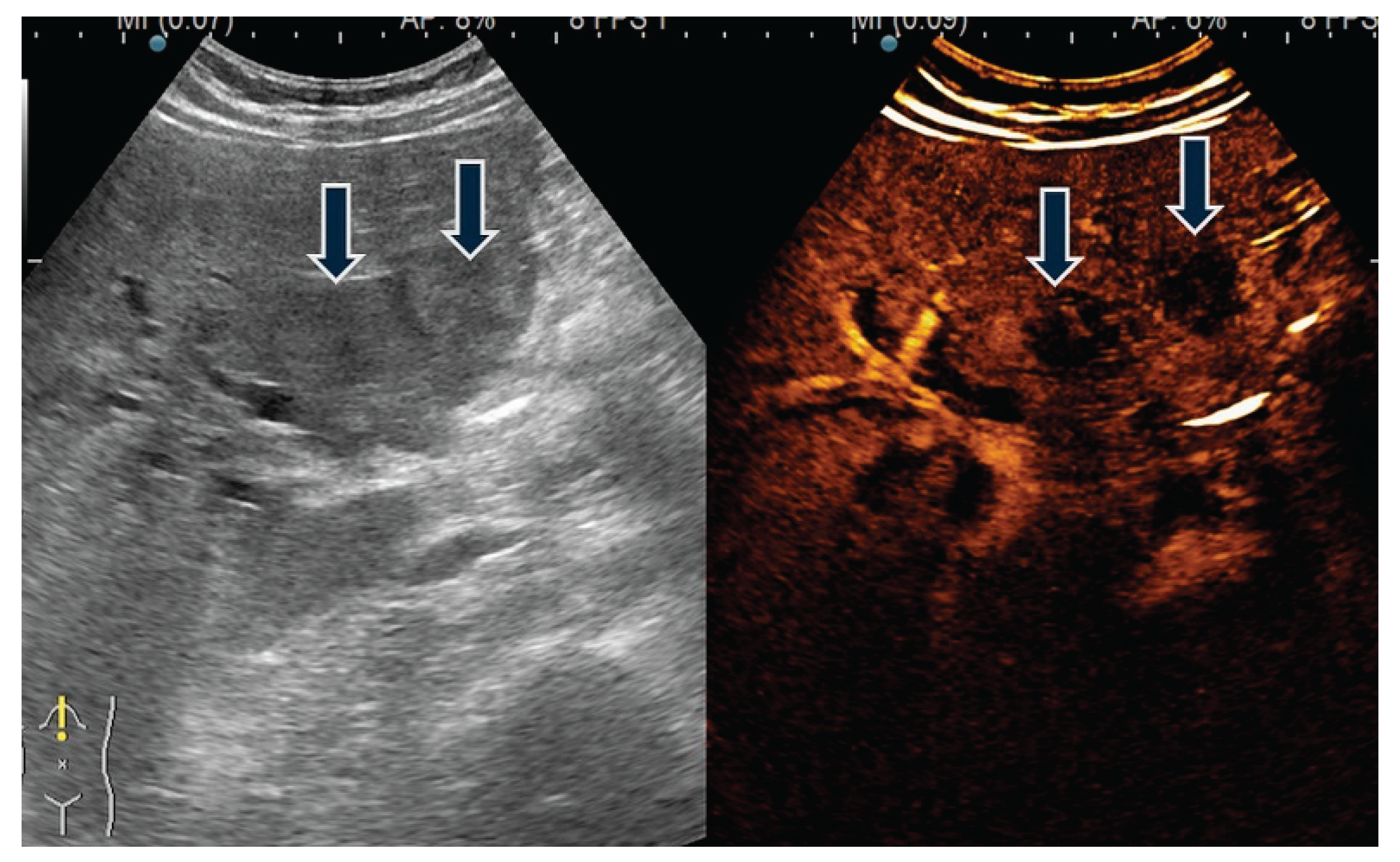

- Zhu, L.; Li, N.; Zhu, Y.; Han, P.; Jiang, B.; Li, M.; Luo, Y.; Clevert, D.A.; Fei, X. Value of high frame rate contrast enhanced ultrasound in gallbladder wall thickening in non-acute setting. Cancer Imaging. 2024, 24, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerakkody, Y.; Yap, J.; Luong, D.; Knipe, H.; Mukherjee, A. Gallbladder cancer (staging - AJCC 8th edition). Reference article, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 16 Apr 2025). [CrossRef]

- Spaziani, E.; Di Cristofano, C.; Di Filippo, A.R.; Caruso, G.; Orelli, S.; Spaziani, M.; Fiori, E.; Picchio, M.; De Cesare, A. Polypoid lesions of the gallbladder in a consecutive series of 2631 patients. A single-center experience. Ann Ital Chir. 2019, 90, 305–310. [Google Scholar]

- Schauer, R.J.; Meyer, G.; Baretton, G.; Schildberg, F.W.; Rau, H.G. Prognostic factors and long-term results after surgery for gallbladder carcinoma: a retrospective study of 127 patients. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2001, 386, 110–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, Y.; Uemura, K.; Sudo, T.; Hashimoto, Y.; Nakashima, A.; Kondo, N.; Sakabe, R.; Kobayashi, H.; Sueda, T. Prognostic factors of patients with advanced gallbladder carcinoma following aggressive surgical resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011, 15, 1007–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.J.; Li, X.H.; Chen, Y.X.; Sun, H.D.; Zhao, G.M.; Hu, S.Y. Radical lymph node dissection and assessment: Impact on gallbladder cancer prognosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 5150–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega EA, De Aretxabala X, Qiao W, Newhook TE, Okuno M, Castillo F, Sanhueza M, Diaz C, Cavada G, Jarufe N, et al. Comparison of oncological outcomes after open and laparoscopic re-resection of incidental gallbladder cancer. Br J Surg. 2020, 107, 289–300. [CrossRef]

- Kijima, H.; Wu, Y.; Yosizawa, T.; Suzuki, T.; Tsugeno, Y.; Haga, T.; Seino, H.; Morohashi, S.; Hakamada, K. Pathological characteristics of early to advanced gallbladder carcinoma and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014, 21, 453–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

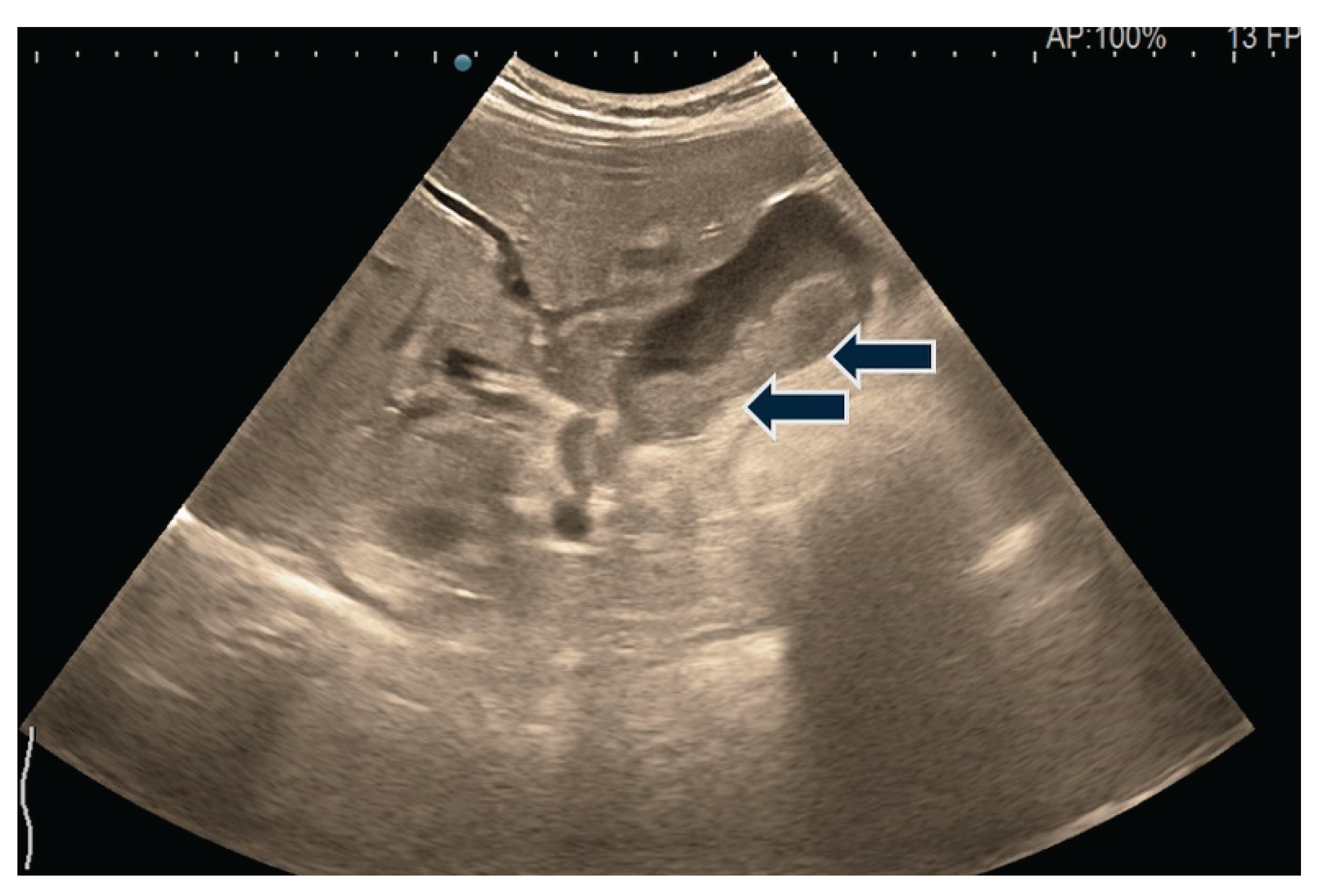

- Gupta, P.; Marodia, Y.; Bansal, A.; Kalra, N. ; Kumar-MP; Sharma, V. ; Dutta, U.; Sandhu, M.S. Imaging-based algorithmic approach to gallbladder wall thickening. World J Gastroenterol. 2020, 26, 6163–6181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H.; Luo, Y.; Fei, X.; Chou, Y.H.; Chiou, H.J.; Wang, H.K.; Lai, Y.C.; Lin, Y.H.; Tiu, C.M.; Wang, J. Algorithmic approaches to the diagnosis of gallbladder intraluminal lesions on ultrasonography. J Chin Med Assoc. 2018, 81, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, E.; Gill, R.; Debru, E. Diagnostic accuracy of transabdominal ultrasonography for gallbladder polyps: systematic review. Can J Surg. 2018, 61, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennmacker, S.Z.; Lamberts, M.P.; Di Martino, M.; Drenth, J.P.; Gurusamy, K.S.; van Laarhoven, C.J. Transabdominal ultrasound and endoscopic ultrasound for diagnosis of gallbladder polyps. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018, 8, CD012233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okaniwa, S. How Can We Manage Gallbladder Lesions by Transabdominal Ultrasound? Diagnostics (Basel). 2021, 11, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, S.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Woo, H.; Joo, I.; Lee, E.S.; Han, J.K.; Choi, B.I. Differentiating between adenomyomatosis and gallbladder cancer: revisiting a comparative study of high-resolution ultrasound, multidetector CT, and MR imaging. Korean J Radiol. 2014, 15, 226–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

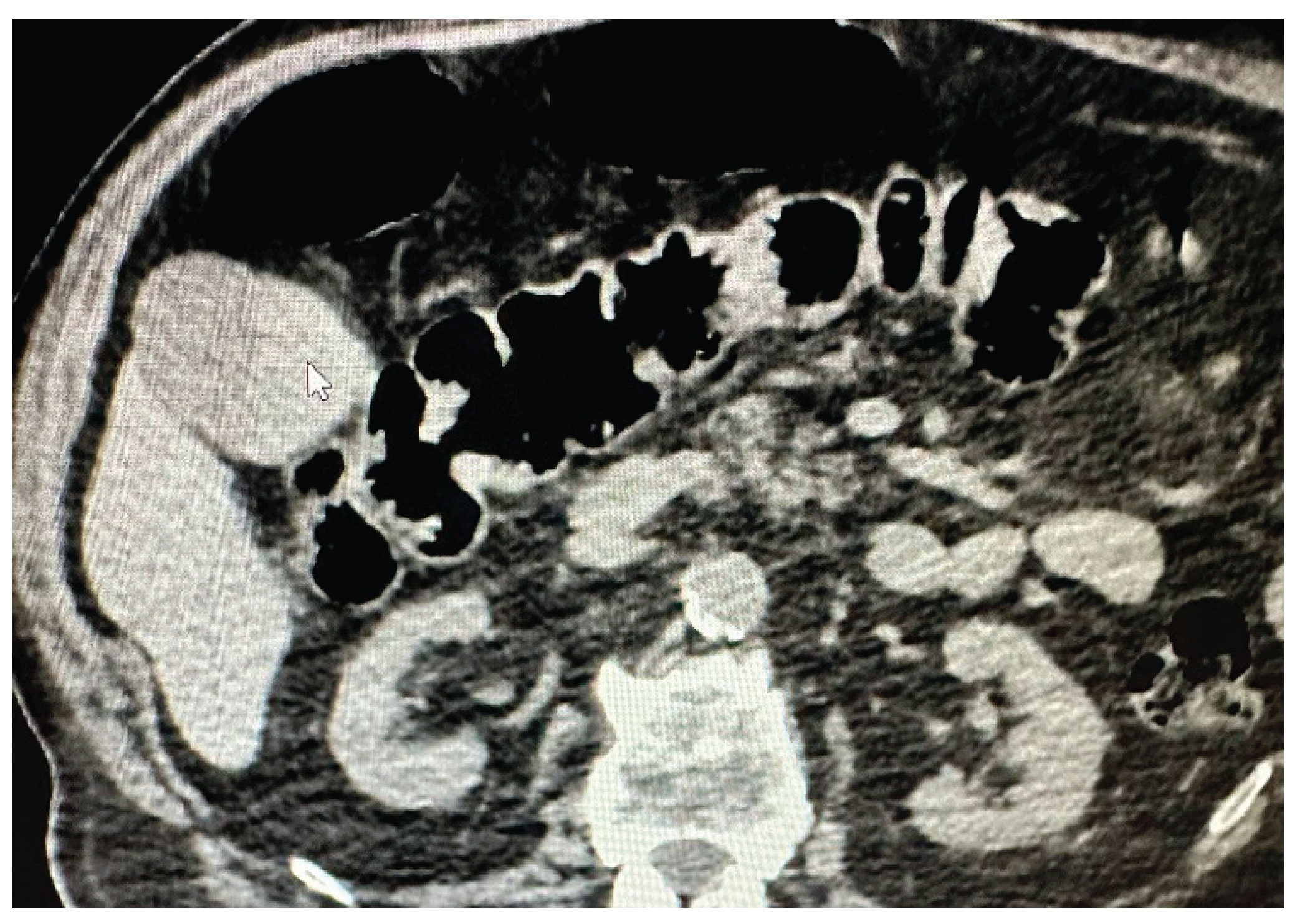

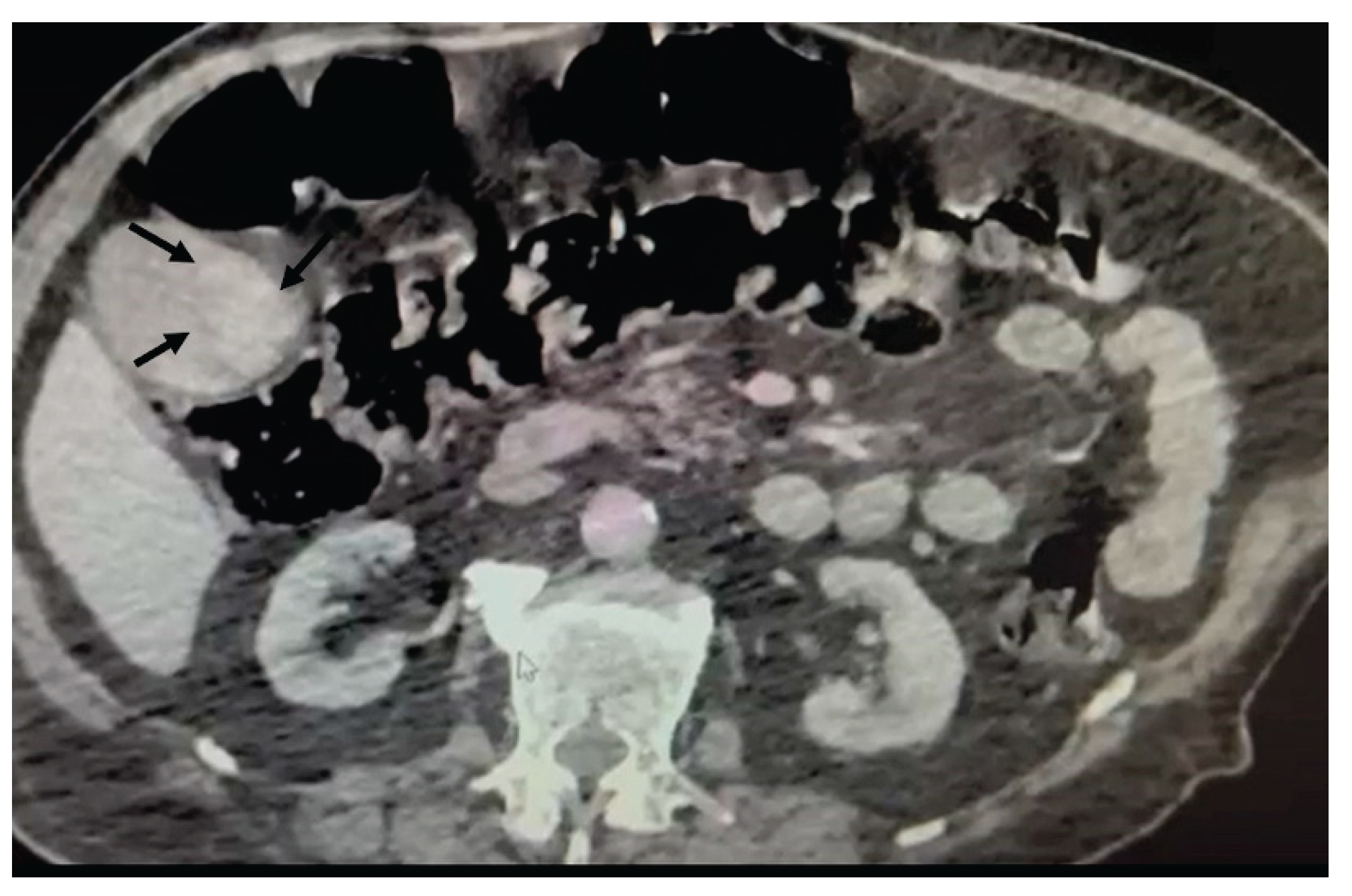

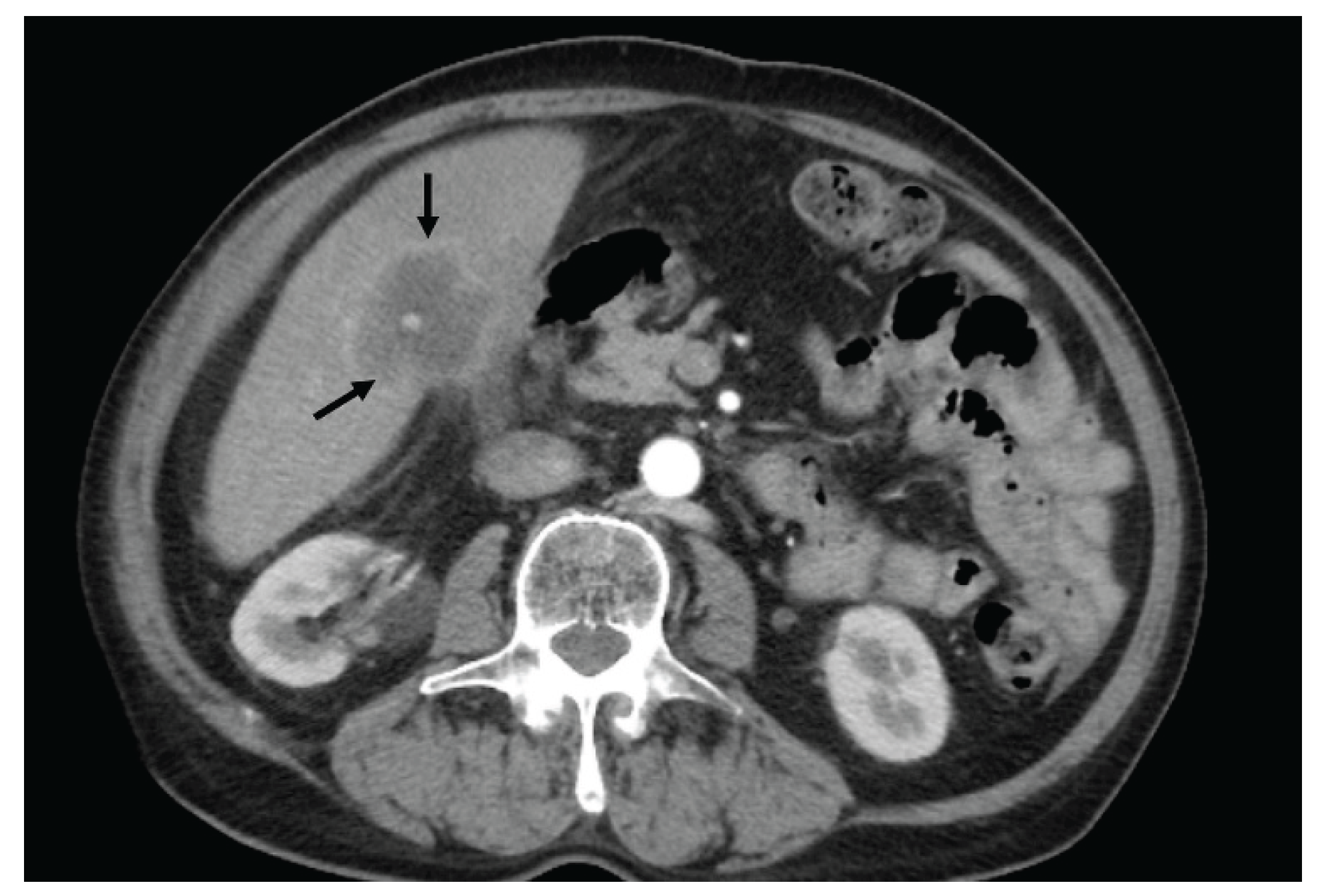

- Tao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, S.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Q.; Mai, X.; Yu, D. Triphasic dynamic contrast-enhanced computed tomography predictive model of benign and malignant risk of gallbladder occupying lesions. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020, 99, e19539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.Y.; Kim, S.W.; Lee, S.E.; Hwang, D.W.; Kim, E.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, S.J.; Ryu, J.K.; Kim, Y.T. Differential diagnostic and staging accuracies of high resolution ultrasonography, endoscopic ultrasonography, and multidetector computed tomography for gallbladder polypoid lesions and gallbladder cancer. Ann Surg. 2009, 250, 943–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu L, Han P, Jiang B, Li N, Fei X. [Differential diagnosis of gallbladder polypoid lesions by micro-flow imaging]. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2022, 42, 922–928 Chinese. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.H.; Kang, H.J.; Bae, J.S. Contrast-Enhanced CT and Ultrasonography Features of Intracholecystic Papillary Neoplasm with or without associated Invasive Carcinoma. Korean J Radiol. 2023, 24, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalage, D.; Gupta, P.; Gulati, A.; Reddy, K.P.; Sharma, K.; Thakur, A.; Yadav, T.D.; Gupta, V.; Kaman, L.; Nada, R.; Singh, H.; Irrinki, S.; Gupta, P.; Das, C.K.; Dutta, U.; Sandhu, M. Contrast Enhanced CT Versus MRI for Accurate Diagnosis of Wall-thickening Type Gallbladder Cancer. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2024, 14, 101397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, N.; Gupta, P.; Singhal, M.; Gupta, R.; Gupta, V.; Srinivasan, R.; Mittal, B.R.; Dhiman, R.K.; Khandelwal, N. Cross-sectional Imaging of Gallbladder Carcinoma: An Update. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2019, 9, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu LN, Xu HX, Lu MD, Xie XY, Wang WP, Hu B, Yan K, Ding H, Tang SS, Qian LX, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound in the diagnosis of gallbladder diseases: a multi-center experience. PLoS One. 2012, 7, e48371. [CrossRef]

- de Sio I, D'Onofrio M, Mirk P, Bertolotto M, Priadko K, Schiavone C, Cantisani V, Iannetti G, Vallone G, Vidili G; SIUMB experts committee. SIUMB recommendations on the use of ultrasound in neoplastic lesions of the gallbladder and extrahepatic biliary tract. J Ultrasound. 2023, 26, 725–731. [CrossRef]

- Foley, K.G.; Lahaye, M.J.; Thoeni, R.F.; Soltes, M.; Dewhurst, C.; Barbu, S.T.; Vashist, Y.K.; Rafaelsen, S.R.; Arvanitakis, M.; Perinel, J.; et al. Management follow-up of gallbladder polyps: updated joint guidelines between the, E. S.G.A.R.; EAES; EFISDS; ESGE Eur Radiol. 2022, 32, 3358–3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparchez, Z.; Radu, P. Role of CEUS in the diagnosis of gallbladder disease. Med Ultrason. 2012, 14, 326–30 PMID: 23243646. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Tang, S.; Huang, L.; Jin, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Lu, C. Value of contrast-enhanced ultrasound in diagnosis and differential diagnosis of polypoid lesions of gallbladder ≥ 1 cm. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022, 22, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori M, Inui K, Yoshino J, Miyoshi H, Okushima K, Nakamura Y, Naito T, Imaeda Y, Horibe Y, Hattori T, et al. [Usefulness of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in the differential diagnosis of polypoid gallbladder lesions]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2007, 104, 790–8 Japanese (Abstract).

- Zheng SG, Xu HX, Liu LN, Lu MD, Xie XY, Wang WP, Hu B, Yan K, Ding H, Tang SS, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound versus conventional ultrasound in the diagnosis of polypoid lesion of gallbladder: a multi-center study of dynamic microvascularization. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2013, 55, 359–74. [CrossRef]

- Miwa H, Numata K, Sugimori K, Sanga K, Hirotani A, Tezuka S, Goda Y, Irie K, Ishii T, Kaneko T, et al. Differential diagnosis of gallbladder polypoid lesions using contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2019, 44, 1367–1378. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.S.; Gu, L.H.; Du, J.; Li, F.H.; Wang, J.; Chen, T.; Zhang, Y.H. Differential diagnosis of polypoid lesions of the gallbladder using contrast-enhanced sonography. J Ultrasound Med. 2015, 34, 1061–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu JM, Guo LH, Xu HX, Zheng SG, Liu LN, Sun LP, Lu MD, Wang WP, Hu B, Yan K, et al. Differential diagnosis of gallbladder wall thickening: the usefulness of contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2014, 40, 2794–804. [CrossRef]

- Bae JS, Kim SH, Kang HJ, Kim H, Ryu JK, Jang JY, Lee SH, Paik WH, Kwon W, Lee JY, et al. Quantitative contrast-enhanced US helps differentiating neoplastic vs non-neoplastic gallbladder polyps. Eur Radiol. 2019, 29, 3772–3781. [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.T.; Shen, H.Y.; Qiu, Y.D.; Han, H.; Wen, B.J.; Wu, M. Application of contrast enhanced ultrasound in gallbladder lesion: is it helpful to improve the diagnostic capabilities? Med Ultrason. 2018, 20, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie XH, Xu HX, Xie XY, Lu MD, Kuang M, Xu ZF, Liu GJ, Wang Z, Liang JY, Chen LD, et al. Differential diagnosis between benign and malignant gallbladder diseases with real-time contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Eur Radiol. 2010, 20, 239–48. [CrossRef]

- Serra C, Felicani C, Mazzotta E, Gabusi V, Grasso V, De Cinque A, Giannitrapani L, Soresi M. CEUS in the differential diagnosis between biliary sludge, benign lesions and malignant lesions. J Ultrasound. 2018, 21, 119–126. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Fei, Y.; Wang, F. Meta-analysis of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography for the detection of gallbladder carcinoma. Med Ultrason. 2016, 18, 281–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Li, F.; Chen, T. Is Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound Superior to Computed Tomography for Differential Diagnosis of Gallbladder Polyps? A Cross-Sectional Study. Front Oncol. 2021, 11, 657223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Kitano, M.; Kudo, M.; Sakamoto, H.; Kawasaki, T.; Yasuda, C.; Maekawa, K. Diagnosis of gallbladder diseases by contrast-enhanced phase-inversion harmonic ultrasonography. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2007, 33, 353–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Xie, T.G.; Ma, Z.Y.; Wu, X.; Li, B.L. Current status and progress in laparoscopic surgery for gallbladder carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 2369–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creasy JM, Goldman DA, Gonen M, Dudeja V, O'Reilly EM, Abou-Alfa GK, Cercek A, Harding JJ, Balachandran VP, Drebin JA, et al. Evolution of surgical management of gallbladder carcinoma and impact on outcome: results from two decades at a single institution. HPB (Oxford). 2019, 21, 1541–1551. [CrossRef]

- Maegawa, F.B.; Ashouri, Y.; Hamidi, M.; Hsu, C.H.; Riall, T.S. Gallbladder Cancer Surgery in the United States: Lymphadenectomy Trends and Impact on Survival. J Surg Res. 2021, 258, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| T category | |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ |

| T1 | |

| T1a* | The tumor invades the lamina propria. |

| T1b* | The tumor invades the muscular layer. |

| T2 | The tumor invades the peri-muscular connective tissue. |

| T3 | The tumor perforates the serosa/directly invades the liver/one adjacent organ/structure. |

| T4 | Tumor invades the main portal vein/hepatic artery/2 or more extrahepatic organs. |

| N category | |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis. |

| N1 | Metastasis in lymph nodes along the cystic duct, common bile duct, hepatic artery, or portal vein. |

| N2 | Metastasis in the periaortic, pericaval, superior mesenteric artery, and celiac trunk. |

| M category | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis. |

| M1 | Distant metastasis. |

| 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

| I | T1 | N0 | M0 |

| II | T2 | N0 | M0 |

| IIIA | T3 | N0 | M0 |

| IIIB | T1-3 | N1 | M0 |

| IVA | T4 | N0-1 | M0 |

| IVB | Any T | Any N | M1 |

| No (%) | |

| Age mean±SD (min-max) | 68.8±9 (46-87) |

| M/F (%F) | 15/25 (62.5) |

| CT scan preoperatively (%) | 23 (57.5) |

| -tumor (%) | 14 (60.9) |

| -lymph nodes (% from preoperatively CT) | 3 (13) |

| -metastasis (% from preoperatively CT) | 6 (26) |

| Ultrasound | |

| YES | 17 (42.5) |

| -tumor | 1 (5.9) |

| -focal thickening | 5 (29.4) |

| -diffuse thickening | 10 (58.8) |

| -lithiasis | 11 (64.7) |

| -sludge | 4 (23.5) |

| Preoperative diagnosis | |

| -tumor | 15 (37.5) |

| -acute/chronic inflammation | 20 (50) |

| -Obstructive jaundice | 5 (12.5) |

| Intraoperative diagnosis | |

| -tumor | 25 (69.4) |

| -acute/chronic inflammation | 11 (30.6) |

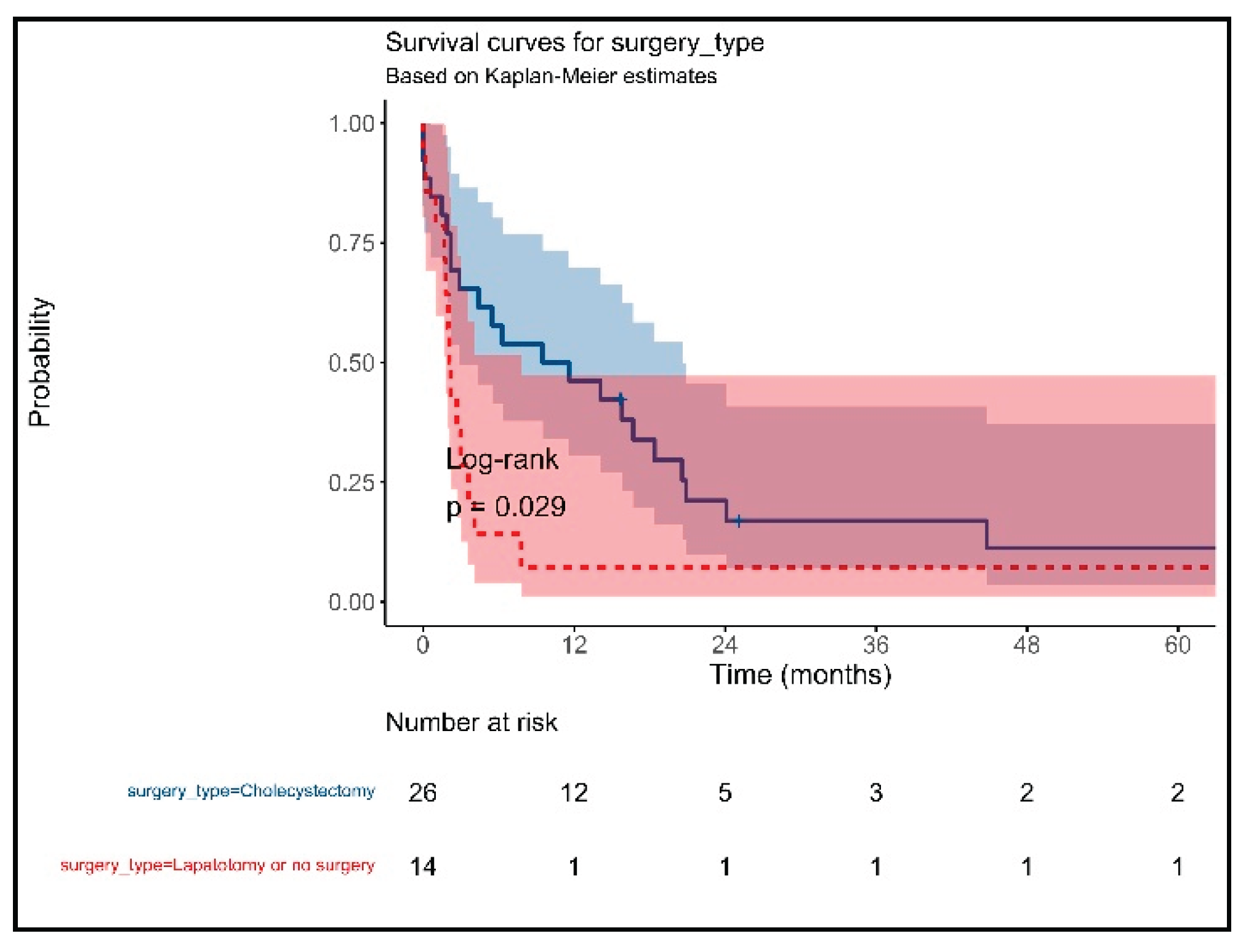

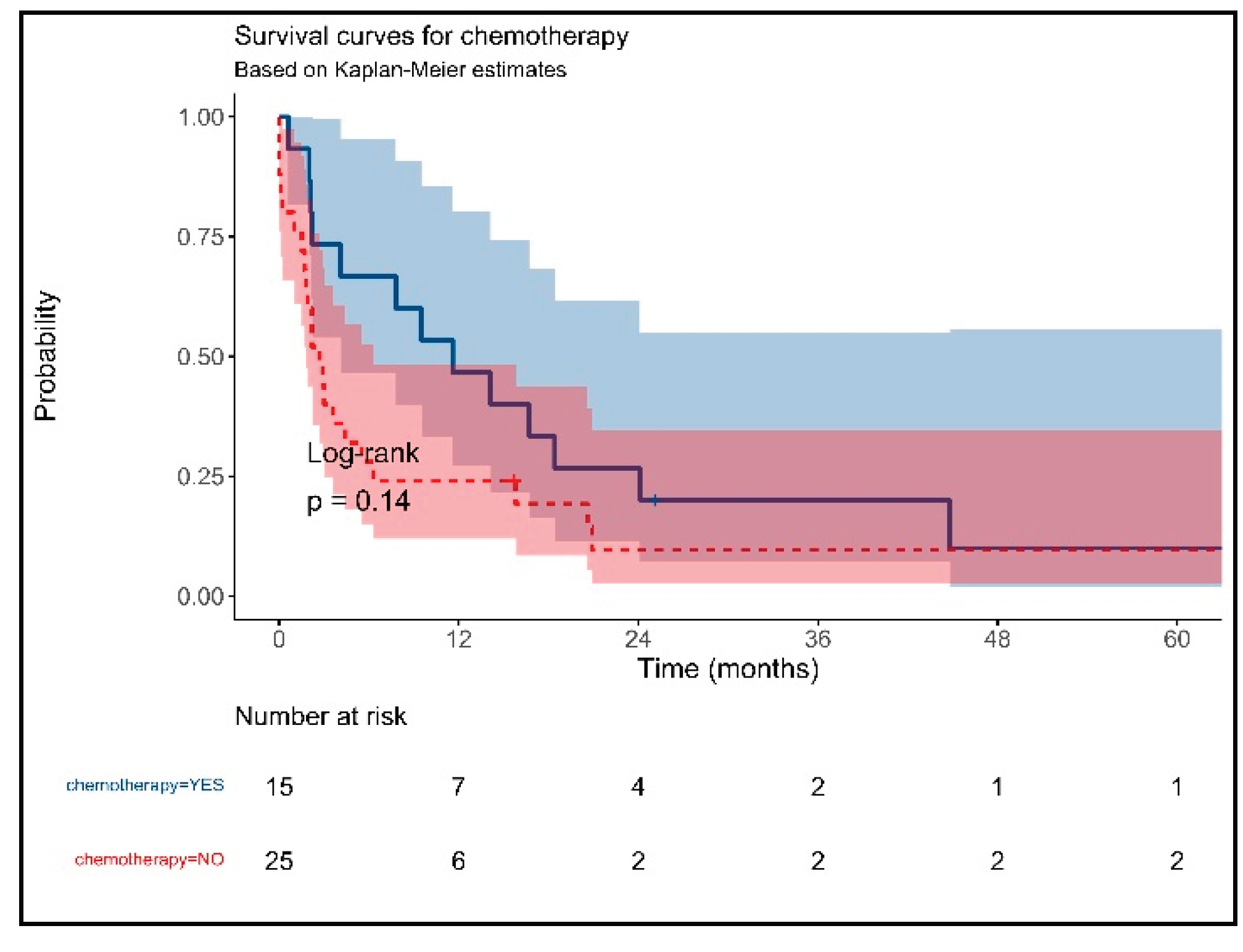

| Surgery | |

| -Open cholecystectomy | 20 (50) |

| -Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | 6 (15) |

| -Laparoscopy with biopsy | 10 (25) |

| -No surgery | 4 (10) |

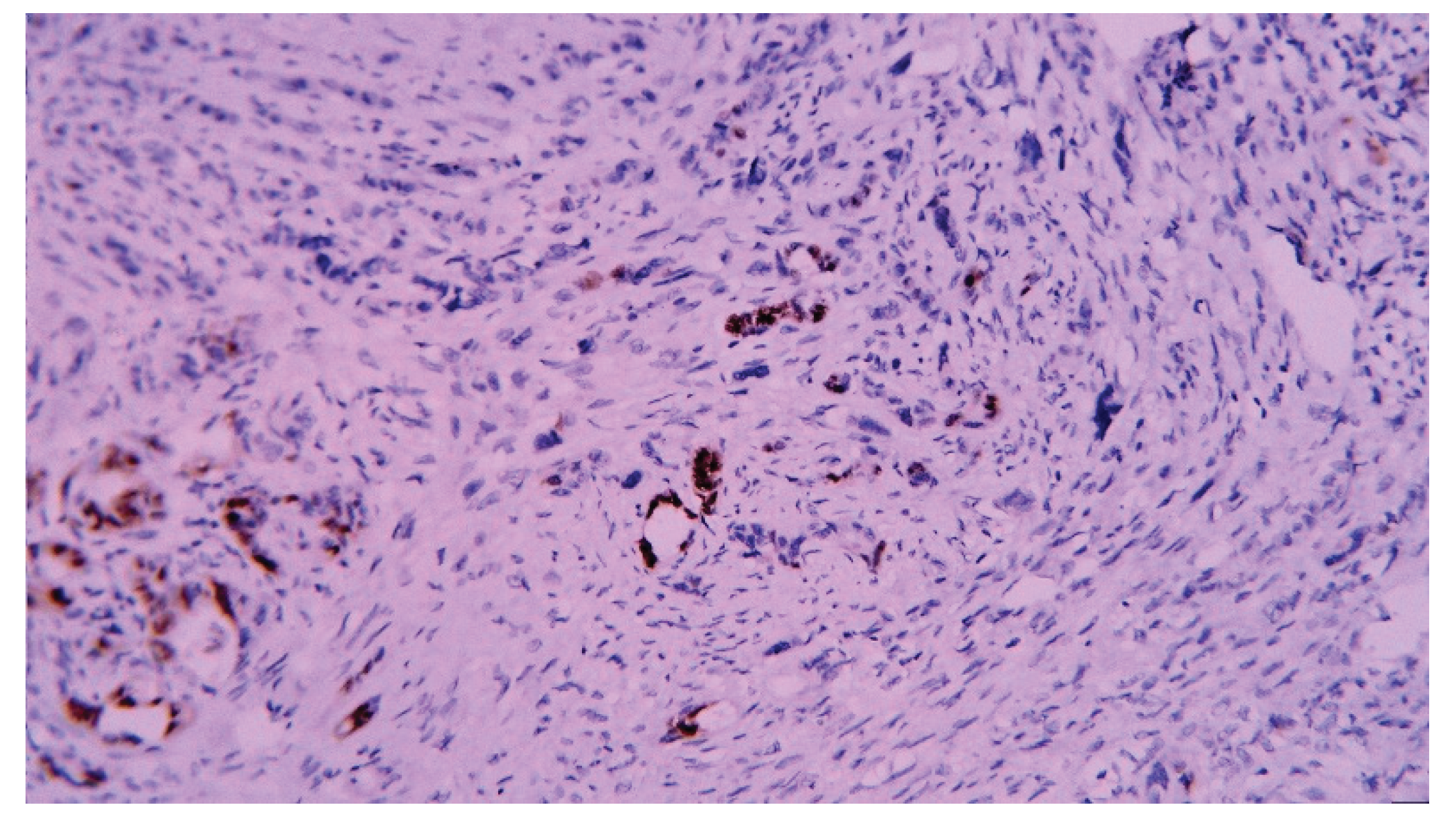

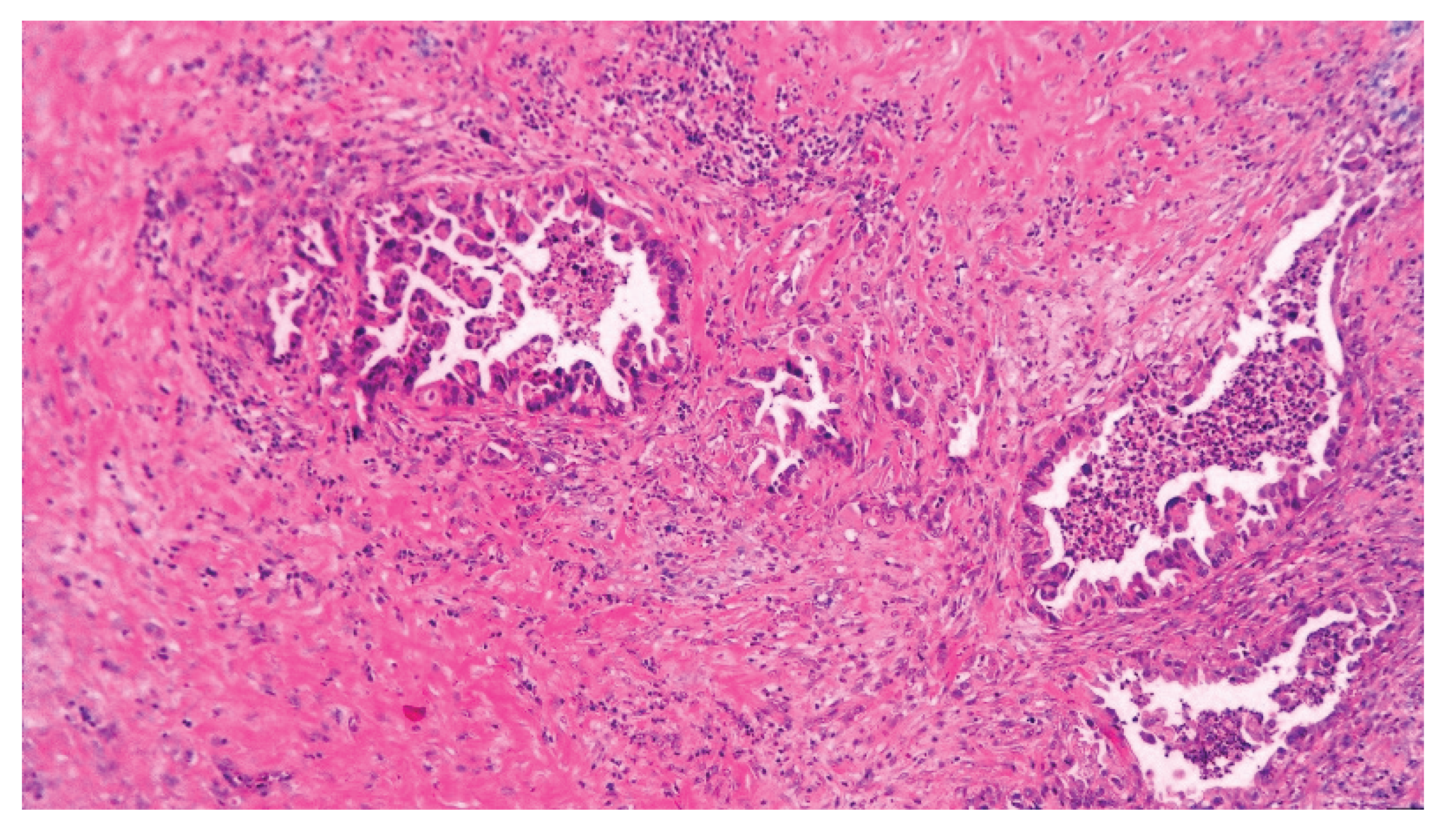

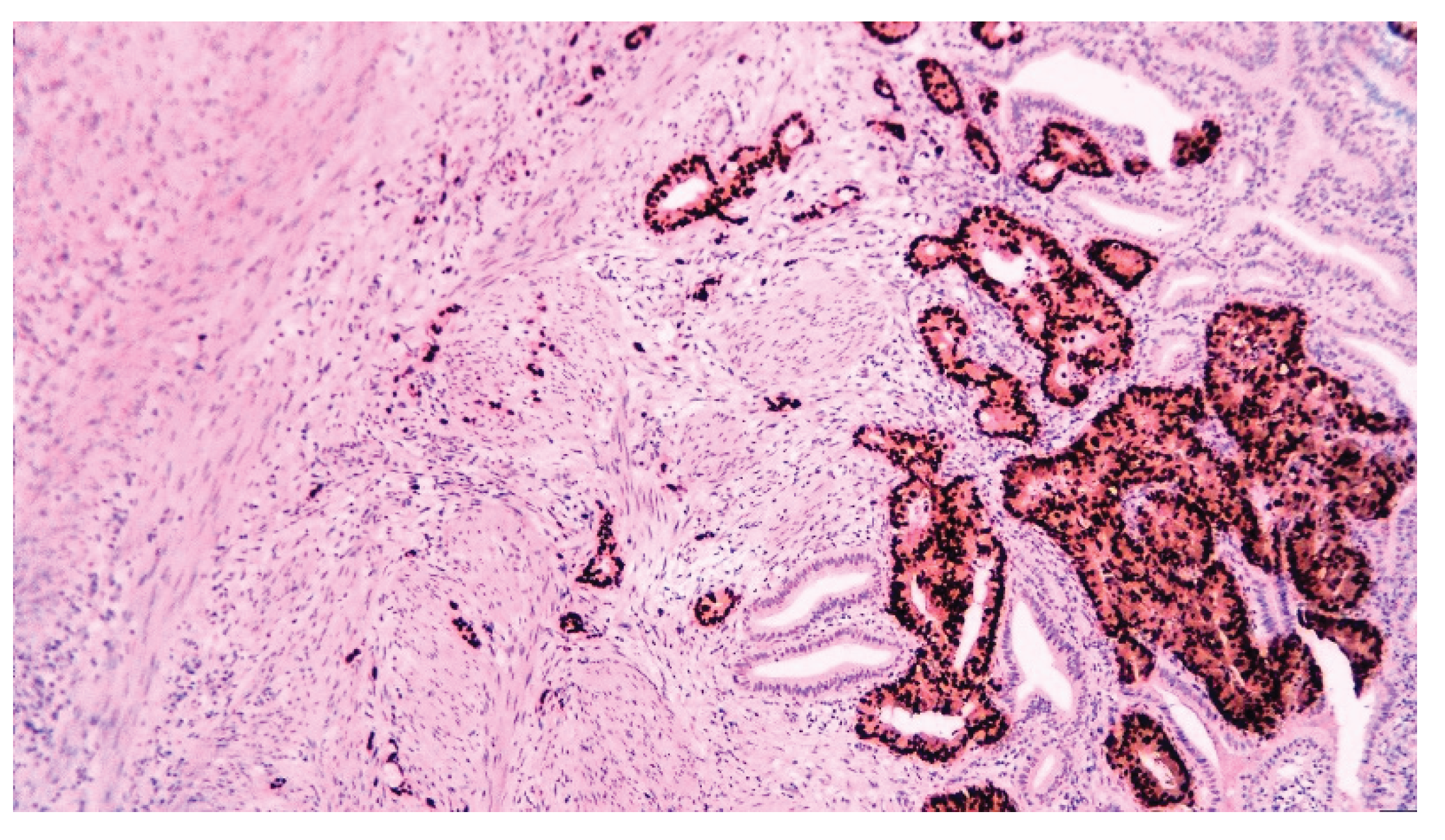

| Pathology | |

| -Adenocarcinoma | 34 (85) |

| -Adenosquamous | 4 (10) |

| -Undifferentiated carcinoma | 2 (5) |

| Lymphatic invasion | 7 (25) |

| Vascular invasion | 12 (42.9) |

| Perineural invasion | 10 (35.7) |

| Grading | 9 (47.4) |

| -G1 | 1 (3.3) |

| -G2 | 11 (36.7) |

| -G3 | 17 (56.7) |

| -G4 | 1 (3.3) |

| Staging | |

| -T1 | 1 (2.5) |

| -T2 | 5 (12.5) |

| -T3 | 20 (50) |

| -T4 | 13 (32.5) |

| -Tx | 1 (2.5) |

| -N0 | 21 (59.3) |

| -N+ | 15 (37.5) |

| -Nx | 4 (10) |

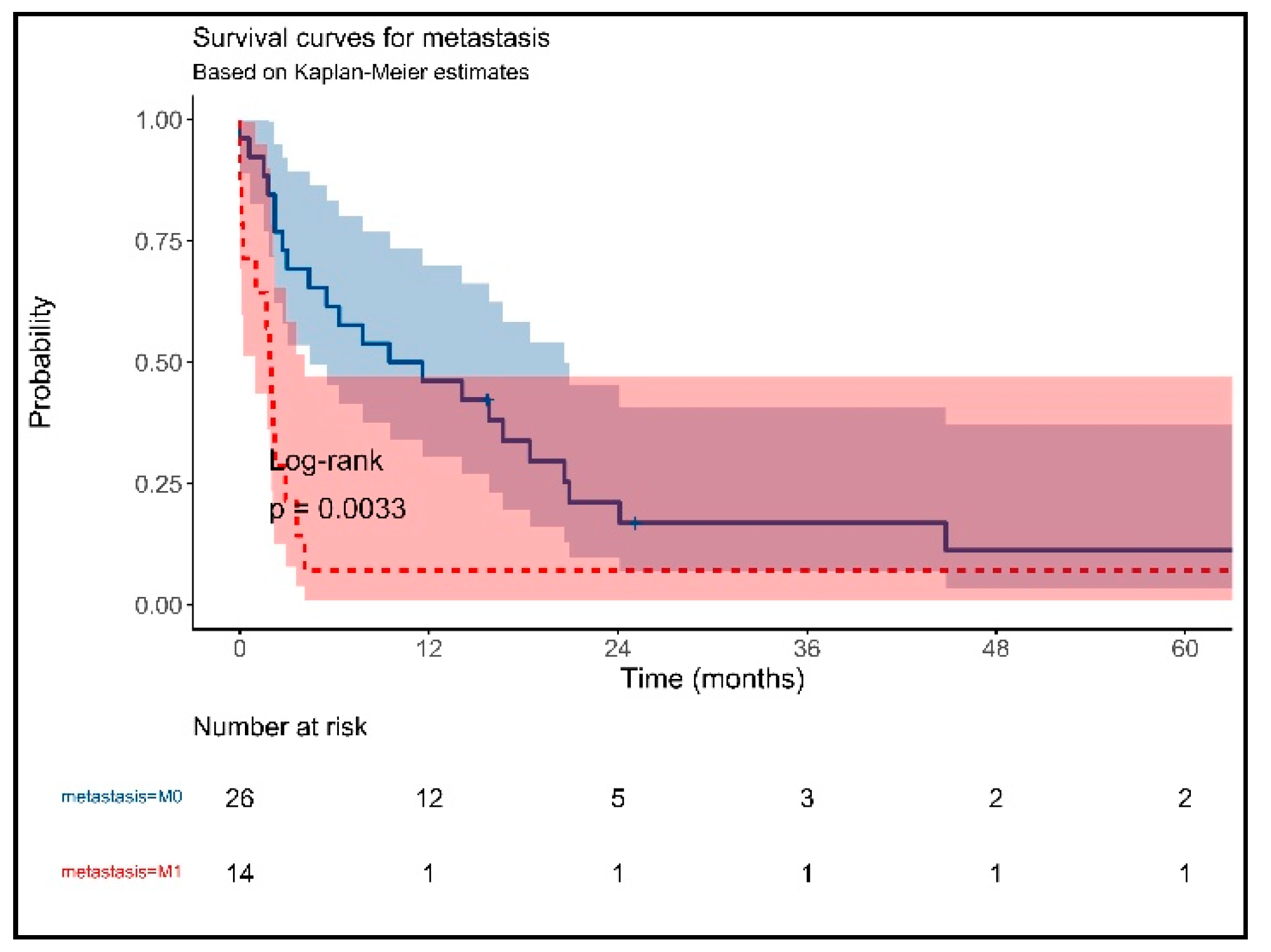

| -M0 | 26 (65) |

| -M1 | 14 (35) |

| -I | 1 (2.5) |

| -II | 2 (5) |

| -IIIA | 13 (37.5) |

| -IIIB | 6 (15) |

| -IVA | 4 (10) |

| -IVB | 14 (35) |

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | |

| Transabdominal US | 35.3 | 98.4 | 27.3 | 98.9 | 97.3 |

| CT scan | 60.9 | 97.6 | 56.0 | 98.1 | 95.9 |

| Preoperative aspect | 51.3 | 99.0 | 45.5 | 99.2 | 98.3 |

| Intraoperative aspect | 74.3 | 99.8 | 83.9 | 99.6 | 99.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).