Submitted:

15 May 2025

Posted:

15 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Joint Inversion Overview

- Simulating data (forward modeling) from an initial guess of the subsurface model for both seismic and electrical methods.

- Comparing simulated data (commonly indicated as predicted response) with observed data (commonly indicated as observed response) for each method to calculate a joint cost functional (Φjoint).

- Iteratively updating the model parameters to minimize the joint misfit, (in Figure 1 this is indicated as Φmis). This includes a weighted combination of all the individual misfit for each data set. Various optimization approaches can be used, such as gradient-based, stochastic, or hybrid methods.

- Optionally, we can impose structural or petrophysical constraints, like cross-gradient (ΦX) or rock-physical relationships (Φanalytic) to enforce consistency between the models belonging to different geophysical domains.

- A regularization term, (Φreg,) introduces additional constraints or prior knowledge to stabilize the inversion process and guide it toward physically meaningful solutions. For instance, a smoothness of the model (e.g., Tikhonov regularization), is often applied assuming that physical properties change gradually in space.

2.2. Self-Aware Joint Inversion

2.3. Expected Benefits

3. Synthetic Tests

3.1. Introduction to the Tests

3.2. Model and Acquisition Geometry

3.3. Cross-Gradient Constraint and User Control

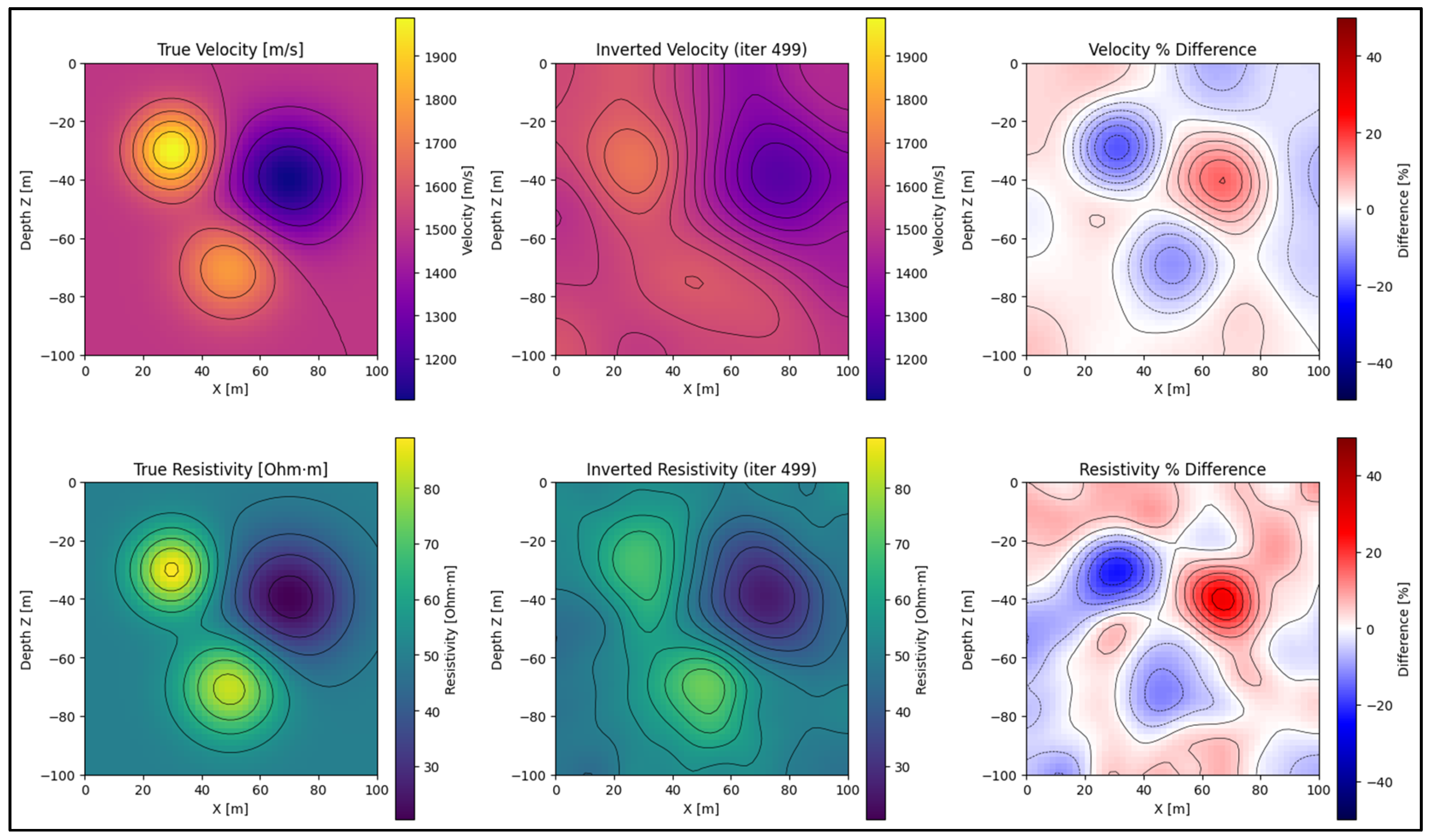

3.4. Results

4. Discussion: Benefits and Limitations

- Benefits:

- Improved accuracy: by jointly inverting seismic and resistivity data, the proposed method generates a more accurate and detailed model of the subsurface, which is particularly beneficial in mineral exploration.

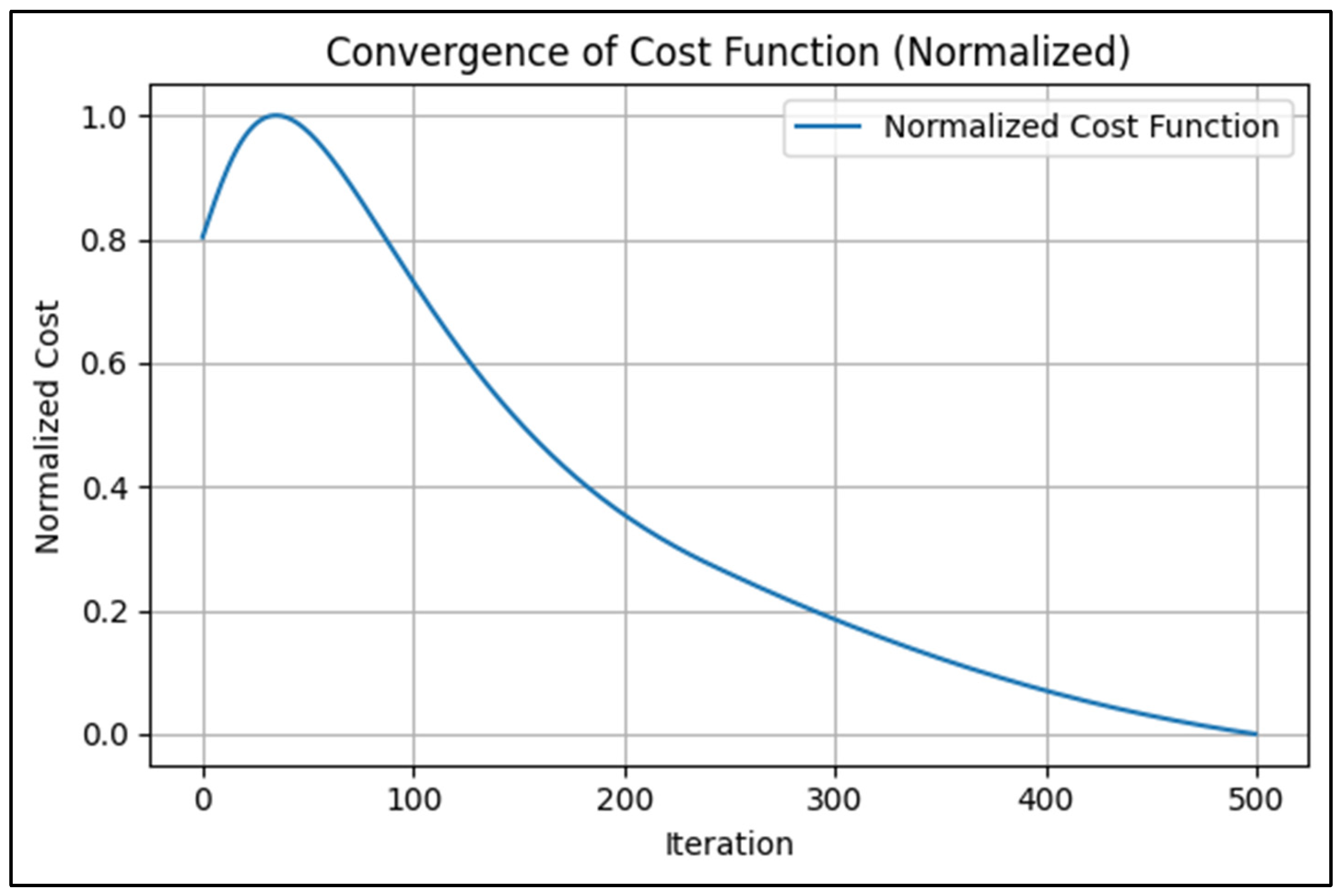

- Self-aware learning: the integration of self-aware learning enables dynamic adjustments of hyper-parameters during the inversion process, improving convergence speed and model accuracy.

- Adaptability: the self-adjustment of hyperparameters ensures that the algorithm adapts to changing data characteristics, preventing overfitting and ensuring robust results.

- Flexibility: the method can be applied to a wide range of geophysical datasets and can incorporate additional geophysical data types in the future.

- Limitations

- Computational complexity: the joint inversion process, combined with self-aware learning, can be computationally intensive, particularly for large-scale 3D datasets.

- Noise sensitivity: while the self-aware learning mechanism helps prevent overfitting, extreme levels of noise in the data may still pose challenges.

- Limited real-world testing: the method was tested using synthetic data, and further validation with real-world datasets is needed to confirm its robustness in actual exploration scenarios.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Appendix: Self-Learning and Self-Aware Basic Mechanisms in the Joint Inversion Framework

- 1.

- Self-Awareness in Hyperparameter Adaptation

- 2.

- Adaptive Smoothing Inspired by Learning Maturation

- 3.

- Feedback-Driven Update with Cross-Domain Coupling

- A data-misfit gradient term,

- A spatial smoothing term, and

- A cross-gradient coupling constraint, cg, encouraging structural similarity across domains.

- 4.

- Domain-Specific Misfit Weights with Self-Tuning

- 5.

- Adaptive Cross-Gradient Constraint

- 6.

- Self-Monitoring and Visualization of Learning Progress

- The misfit curves across different domains,

- The evolution of key hyperparameters (alpha, beta, weights),

- The structural correlation between inverted models.

| Hyperparameter | Self-Adjustment Mechanism |

|---|---|

| Learning rates (alpha_v, alpha_r) | Adjusted based on misfit norm evolution |

| Smoothing factor (sigma_smooth) | Decreases over iterations to allow fine detail |

| Cross-gradient weight (beta) | Tuned based on structural similarity between models |

| Misfit weights (w_seis, w_elec, etc.) | Balanced according to relative misfit magnitudes |

| Smoothing weights (w_smooth_v, w_smooth_r) | Adjustable to control spatial coherence |

| Visualization frequency | Triggered adaptively by error dynamics or plateau detection |

References

- Yilmaz, Ö., 2001. Seismic Data Analysis: Processing, Inversion, and Interpretation of Seismic Data. SEG Books.

- Nabighian, M.N., 2008. Electromagnetic Methods in Applied Geophysics: Applications, Part A and Part B. Society of Exploration Geophysicists.

- Aster, A., Borchers, B., and Thurber, C., 2003, Parameter estimation and inverse problems, Academic Press, New York.

- Backus, G., and Gilbert, F., 1967. Numerical applications of a formalism for geophysical inverse problems, Geophys. J. Royal Astron. Soc., 13, 247–276. [CrossRef]

- Vozoff, K, Jupp, D. L. B., 1975. Joint Inversion of Geophysical Data, Geophysical Journal International, Volume 42, Issue 3, September 1975, Pages 977–991. [CrossRef]

- Colombo, D., McNeice, G., Raterman, N., Turkoglu, E., Sandoval-Curiel, E., 2014. Massive integration of 3D EM, gravity and seismic data for deepwater subsalt imaging in the Red Sea. Exp. Abstracts, SEG 2014.

- Dell’Aversana, P., 2014. Integrated Geophysical Models: Combining Rock Physics with Seismic, Electromagnetic and Gravity Data. EAGE Publications.

- Haber, E. and Oldenburg, D., 1997. Joint Inversion: A Structural Approach, Inverse Problems, Vol. 13, No. 1, 1997, pp. 63-77. [CrossRef]

- Giampaolo, V., Dell’Aversana, P., Capozzoli, L., De Martino, G., Rizzo, E., 2021. Combining Multi-temporal Electric Resistivity Tomography and Predictive Algorithms for supporting aquifer monitoring and management. NSG2021 1st Conference on Hydrogeophysics, 2021.0(1).

- Giampaolo, V., Rizzo, E., Straface, S., Votta, M., 2011. Hydrogeophysics techniques for the characterization of a heterogeneous aquifer. Bollettino di Geofisica Teorica ed Applicata, 52, 595-606. [CrossRef]

- Günther, T., Rücker, C., Spitzer, K., 2006. Three–dimensional modeling and inversion of dc resistivity data incorporating topography–II Inversion. Geophysical Journal International, 166, 506–517. 44. [CrossRef]

- Dell‘Aversana, P., 2001. Integration of seismic, MT and gravity data in a thrust belt interpretation. First Break, Volume 19, Issue 6, Jun 2001. [CrossRef]

- Dell’Aversana P., 2024. An introduction to Self-Aware Deep Learning for medical imaging and diagnosis. Explor Digit Health Technol. 2024; 2:218–34. [CrossRef]

- Dell’Aversana, P., 2024. Enhancing Deep Learning and Computer Image Analysis in Petrography through Artificial Self-Awareness Mechanisms. Minerals 2024, 14, 247. [CrossRef]

- Dell'Aversana, P., 2024. Reservoir geophysical monitoring supported by artificial general intelligence and Q-Learning for oil production optimization. AIMS Geosciences, 2024, 10(3): 641-661. [CrossRef]

- Tarantola, A., 2005. Inverse Problem Theory and Methods for Model Parameter Estimation. SIAM. ISBN 978-0-89871-572-9.

- Boyd, S.P., Vandenberghe, L., 2004, Convex Optimization. Cambridge University Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-521-83378-3.

- Horst, R., Tuy, H., 1996, Global Optimization: Deterministic Approaches, Springer.

- Neumaier, A., 2004, Complete Search in Continuous Global Optimization and Constraint Satisfaction, pp. 271–369 in: Acta Numerica 2004 (A. Iserles, ed.), Cambridge University Press 2004.

- Raschka, S. and Mirjalili, V., 2017, Python Machine Learning: Machine Learning and Deep Learning with Python, scikit-learn, and TensorFlow, 2nd Edition, PACKT Books.

- Ravichandiran, S., 2020, Deep Reinforcement learning with Python, Packt Publishing.

- Dell’Aversana, P., 2022. Reinforcement learning in optimization problems. Applications to geophysical data inversion. AIMS Geosciences, 2022, 8(3): 488-502. [CrossRef]

- Dell’Aversana, P., 2023. Inversion of geophysical data supported by Reinforcement Learning. Bulletin of Geophysics and Oceanography, Vol. 64, n. 1, pp. 45-60; March 2023. [CrossRef]

- Dell’Aversana, P. A Biological-Inspired Deep Learning Framework for Big Data Mining and Automatic Classification in Geosciences. Minerals 2025, 15, 356. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).