Submitted:

15 May 2025

Posted:

15 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Role of Vitamin D

3. Inflammatory Processes and the Role of Lipid Acid-Derived Mediators

4. SPMs are Essential for Resolution of Inflammation

5. The Significance of SPMs in Chronic Inflammatory Diseases

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Islam, M.S. , et al., Extracellular matrix in uterine leiomyoma pathogenesis: a potential target for future therapeutics. Hum Reprod Update, 2018. 24(1): p. 59-85.

- Buttram, V.C., Jr. and R.C. Reiter, Uterine leiomyomata: etiology, symptomatology, and management. Fertil Steril, 1981. 36(4): p. 433-45.

- Cramer, S.F. and A. Patel, The frequency of uterine leiomyomas. Am J Clin Pathol, 1990. 94(4): p. 435-8.

- Marshall, L.M. , et al., Variation in the incidence of uterine leiomyoma among premenopausal women by age and race. Obstet Gynecol, 1997. 90(6): p. 967-73.

- Baird, D.D. , et al., High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2003. 188(1): p. 100-7.

- Kjerulff, K.H. , et al., Uterine leiomyomas. Racial differences in severity, symptoms and age at diagnosis. J Reprod Med, 1996. 41(7): p. 483-90.

- Szydlowska, I. , et al., Markers of Inflammation and Vascular Parameters in Selective Progesterone Receptor Modulator (Ulipristal Acetate)-Treated Uterine Fibroids. J Clin Med, 2021. 10(16).

- Goad, J. , et al., Single Cell atlas of uterine myometrium and leiomyomas reveals diverse and novel cell types of non-monoclonal origin. bioRxiv, 2020: p. 2020.12.21.402313.

- Tal, R. and J.H. Segars, The role of angiogenic factors in fibroid pathogenesis: potential implications for future therapy. Hum Reprod Update, 2014. 20(2): p. 194-216.

- Ciavattini, A. , et al., Uterine fibroids: pathogenesis and interactions with endometrium and endomyometrial junction. Obstet Gynecol Int, 2013. 2013: p. 173184.

- Galindo, L.J. , et al., HMGA2 and MED12 alterations frequently co-occur in uterine leiomyomas. Gynecol Oncol, 2018. 150(3): p. 562-568.

- Grings, A.O. , et al., Protein expression of estrogen receptors alpha and beta and aromatase in myometrium and uterine leiomyoma. Gynecol Obstet Invest, 2012. 73(2): p. 113-7.

- Ishikawa, H. , et al., Progesterone is essential for maintenance and growth of uterine leiomyoma. Endocrinology, 2010. 151(6): p. 2433-42.

- Kawaguchi, K. , et al., Mitotic activity in uterine leiomyomas during the menstrual cycle. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1989. 160(3): p. 637-41.

- Islam, M.S. , et al., Complex networks of multiple factors in the pathogenesis of uterine leiomyoma. Fertil Steril, 2013. 100(1): p. 178-93.

- Modugno, F. , et al., Inflammation and endometrial cancer: a hypothesis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2005. 14(12): p. 2840-7.

- Orciani, M. , et al., Chronic Inflammation May Enhance Leiomyoma Development by the Involvement of Progenitor Cells. Stem Cells Int, 2018. 2018: p. 1716246.

- Protic, O. , et al., Possible involvement of inflammatory/reparative processes in the development of uterine fibroids. Cell Tissue Res, 2016. 364(2): p. 415-27.

- Macdiarmid, F. , et al., Stimulation of aromatase activity in breast fibroblasts by tumor necrosis factor alpha. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 1994. 106(1-2): p. 17-21.

- Purohit, A., S. P. Newman, and M.J. Reed, The role of cytokines in regulating estrogen synthesis: implications for the etiology of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res, 2002. 4(2): p. 65-9.

- Leppert, P.C. et al., Summary of the Proceedings of the Basic Science of Uterine Fibroids Meeting: New Developments February 28, 2020. F S Sci, 2021. 2(1): p. 88-100.

- Ciebiera, M. , et al., The Evolving Role of Natural Compounds in the Medical Treatment of Uterine Fibroids. J Clin Med, 2020. 9(5).

- Zannotti, A. , et al., Macrophages and Immune Responses in Uterine Fibroids. Cells, 2021. 10(5).

- Lima, M.S.O. , et al., Evaluation of vitamin D receptor expression in uterine leiomyoma and nonneoplastic myometrial tissue: a cross-sectional controlled study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol, 2021. 19(1): p. 67.

- Halder, S.K., J. S. Goodwin, and A. Al-Hendy, 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 reduces TGF-beta3-induced fibrosis-related gene expression in human uterine leiomyoma cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2011. 96(4): p. E754-62.

- Halder, S.K., K. G. Osteen, and A. Al-Hendy, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin d3 reduces extracellular matrix-associated protein expression in human uterine fibroid cells. Biol Reprod, 2013. 89(6): p. 150.

- Al-Hendy, A. , et al., 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 regulates expression of sex steroid receptors in human uterine fibroid cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2015. 100(4): p. E572-82.

- Paffoni, A. , et al., Vitamin D status in women with uterine leiomyomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2013. 98(8): p. E1374-8.

- Baird, D.D. , et al., Vitamin d and the risk of uterine fibroids. Epidemiology, 2013. 24(3): p. 447-53.

- Sabry, M. , et al., Serum vitamin D3 level inversely correlates with uterine fibroid volume in different ethnic groups: a cross-sectional observational study. Int J Womens Health, 2013. 5: p. 93-100.

- Chiurchiu, V., A. Leuti, and M. Maccarrone, Bioactive Lipids and Chronic Inflammation: Managing the Fire Within. Front Immunol, 2018. 9: p. 38.

- Flower, R.J. , Prostaglandins, bioassay and inflammation. Br J Pharmacol, 2006. 147 Suppl 1: p. S182-92.

- Samuelsson, B. , Role of basic science in the development of new medicines: examples from the eicosanoid field. J Biol Chem, 2012. 287(13): p. 10070-10080.

- Hotchkiss, R.S. , et al., Sepsis and septic shock. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2016. 2: p. 16045.

- Furman, D. , et al., Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat Med, 2019. 25(12): p. 1822-1832.

- Nathan, C. and A. Ding, Nonresolving inflammation. Cell, 2010. 140(6): p. 871-82.

- Serhan, C.N. , Pro-resolving lipid mediators are leads for resolution physiology. Nature, 2014. 510(7503): p. 92-101.

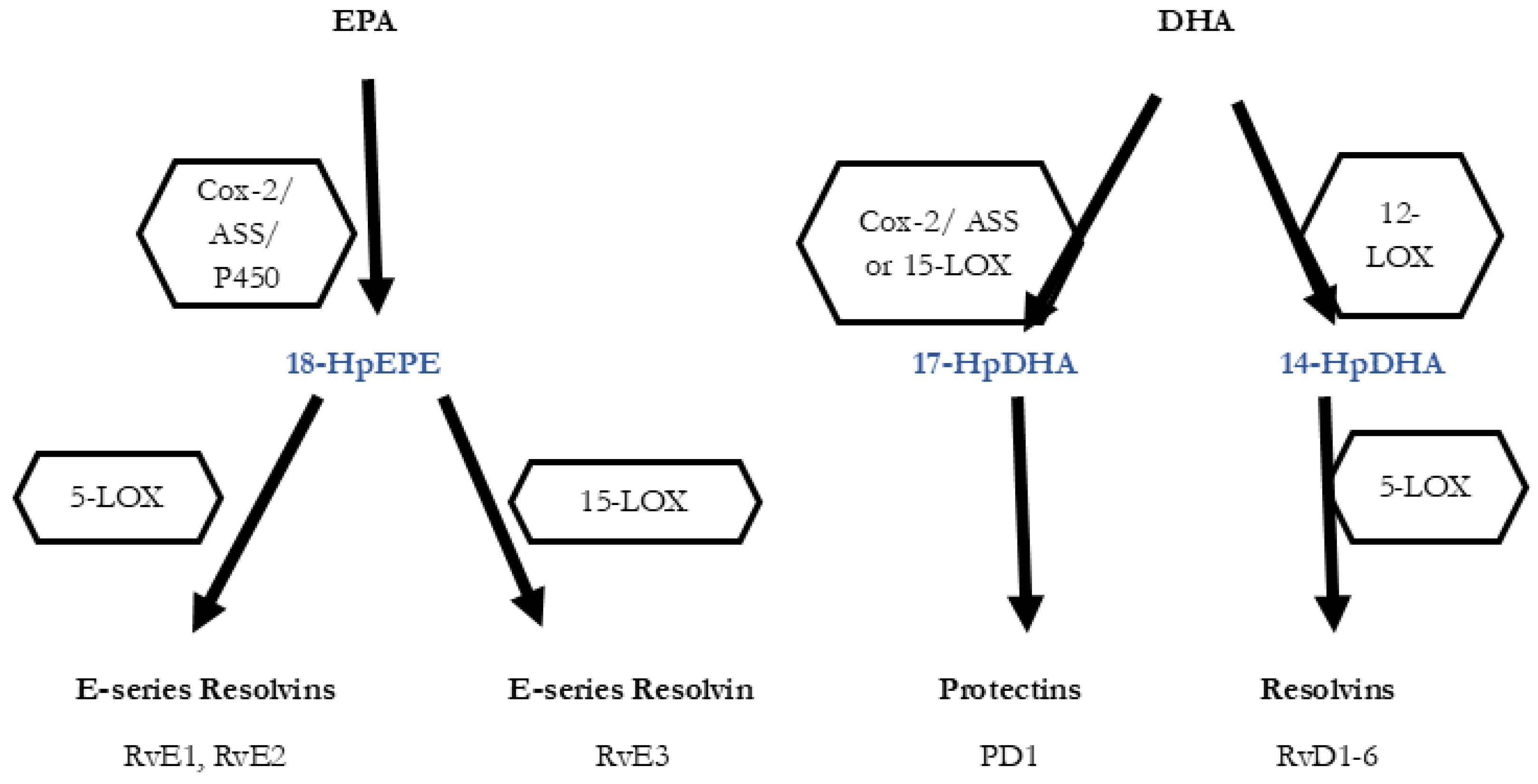

- Serhan, C.N. , et al., Novel functional sets of lipid-derived mediators with antiinflammatory actions generated from omega-3 fatty acids via cyclooxygenase 2-nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and transcellular processing. J Exp Med, 2000. 192(8): p. 1197-204.

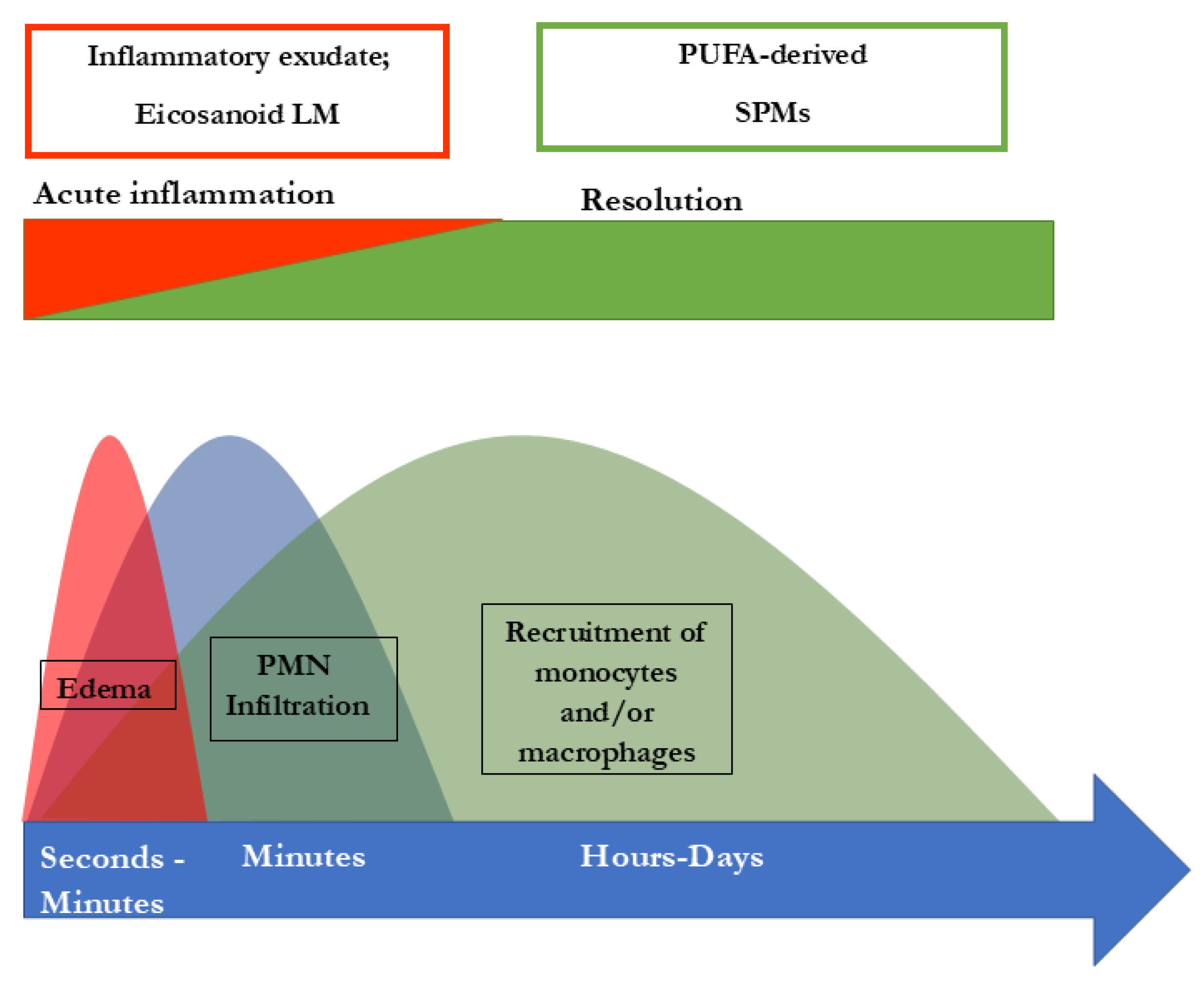

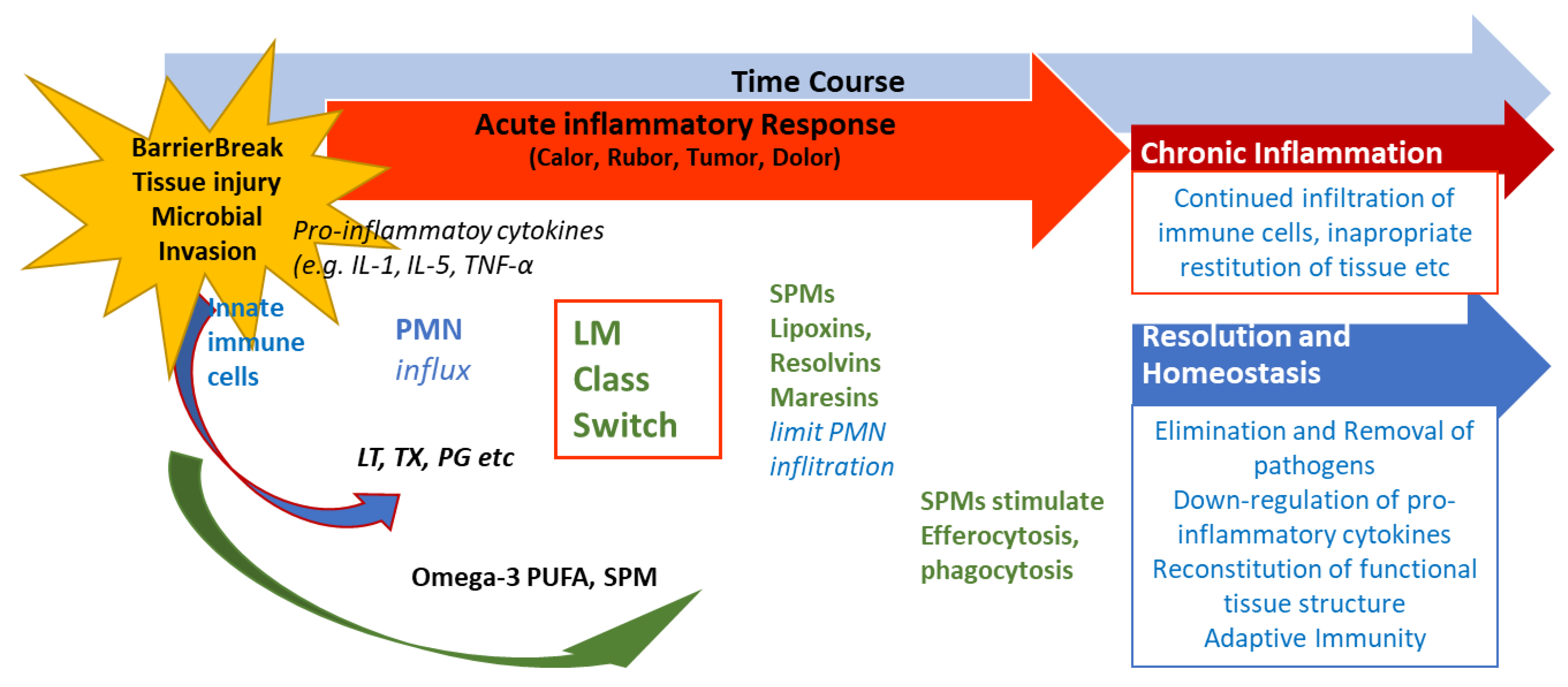

- Serhan, C.N., N. Chiang, and J. Dalli, The resolution code of acute inflammation: Novel pro-resolving lipid mediators in resolution. Semin Immunol, 2015. 27(3): p. 200-15.

- Serhan, C.N. , Treating inflammation and infection in the 21st century: new hints from decoding resolution mediators and mechanisms. FASEB J, 2017. 31(4): p. 1273-1288.

- Regidor, P.A. , et al., Omega-3 long chain fatty acids and their metabolites in pregnancy outcomes for the modulation of maternal inflammatory- associated causes of preterm delivery, chorioamnionitis and preeclampsia. F1000Research 2024, 13:882.

- Serhan, C.N. , et al., Novel proresolving aspirin-triggered DHA pathway. Chem Biol, 2011. 18(8): p. 976-87.

- Serhan, C.N. , et al., Resolvins: a family of bioactive products of omega-3 fatty acid transformation circuits initiated by aspirin treatment that counter proinflammation signals. J Exp Med, 2002. 196(8): p. 1025-37.

- Schett, G. and M.F. Neurath, Resolution of chronic inflammatory disease: universal and tissue-specific concepts. Nat Commun, 2018. 9(1): p. 3261.

- Serhan, C.N. and N. Chiang, Resolution phase lipid mediators of inflammation: agonists of resolution. Curr Opin Pharmacol, 2013. 13(4): p. 632-40.

- Serhan, C.N. and B.D. Levy, Resolvins in inflammation: emergence of the pro-resolving superfamily of mediators. J Clin Invest, 2018. 128(7): p. 2657-2669.

- Serhan, C.N. and J. Savill, Resolution of inflammation: the beginning programs the end. Nat Immunol, 2005. 6(12): p. 1191-7.

- Bandeira-Melo, C. , et al., Cyclooxygenase-2-derived prostaglandin E2 and lipoxin A4 accelerate resolution of allergic edema in Angiostrongylus costaricensis-infected rats: relationship with concurrent eosinophilia. J Immunol, 2000. 164(2): p. 1029-36.

- Levy, B.D. , et al., Lipid mediator class switching during acute inflammation: signals in resolution. Nat Immunol, 2001. 2(7): p. 612-9.

- Barnig, C. , et al., Lipoxin A4 regulates natural killer cell and type 2 innate lymphoid cell activation in asthma. Sci Transl Med, 2013. 5(174): p. 174ra26.

- Chiurchiu, V. , et al., Proresolving lipid mediators resolvin D1, resolvin D2, and maresin 1 are critical in modulating T cell responses. Sci Transl Med, 2016. 8(353): p. 353ra111.

- Serhan, C.N. , et al., Reduced inflammation and tissue damage in transgenic rabbits overexpressing 15-lipoxygenase and endogenous anti-inflammatory lipid mediators. J Immunol, 2003. 171(12): p. 6856-65.

- Merched, A.J. , et al., Atherosclerosis: evidence for impairment of resolution of vascular inflammation governed by specific lipid mediators. FASEB J, 2008. 22(10): p. 3595-606.

- Merched, A.J., C. N. Serhan, and L. Chan, Nutrigenetic disruption of inflammation-resolution homeostasis and atherogenesis. J Nutrigenet Nutrigenomics, 2011. 4(1): p. 12-24.

- Lima-Garcia, J.F. , et al., The precursor of resolvin D series and aspirin-triggered resolvin D1 display anti-hyperalgesic properties in adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats. Br J Pharmacol, 2011. 164(2): p. 278-93.

- Martins, V. , et al., ATLa, an aspirin-triggered lipoxin A4 synthetic analog, prevents the inflammatory and fibrotic effects of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. J Immunol, 2009. 182(9): p. 5374-81.

- Borgeson, E. , et al., Lipoxin A(4) and benzo-lipoxin A(4) attenuate experimental renal fibrosis. FASEB J, 2011. 25(9): p. 2967-79.

- Qu, X. , et al., Resolvins E1 and D1 inhibit interstitial fibrosis in the obstructed kidney via inhibition of local fibroblast proliferation. J Pathol, 2012. 228(4): p. 506-19.

- Lagana AS, Vitale SG, Ban Frangez H, Vrtacnik-Bokal E., D’Anna R. Vitamin D in human reproduction: the more, the better? An evidence-based critical appraisal. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 2017; 21: 4243-4251.

- Colonese F, Laganà AS, Colonese E, Sofo V, Salmeri FM, Granese R, Triolo O. The pleiotropic Effects of Vitamin D in Gynaecological and Obstetric Diseases: An Overview on a Hot Topic. BioMed Research International Volume 2015, Article ID 986281, 11 pages. [CrossRef]

- Vergara D, Catherino WH, Trojano G, Tinelli A. Vitamin D: Mechanism of Action and Biological Effects in Uterine Fibroids. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 597. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).