Submitted:

14 May 2025

Posted:

15 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

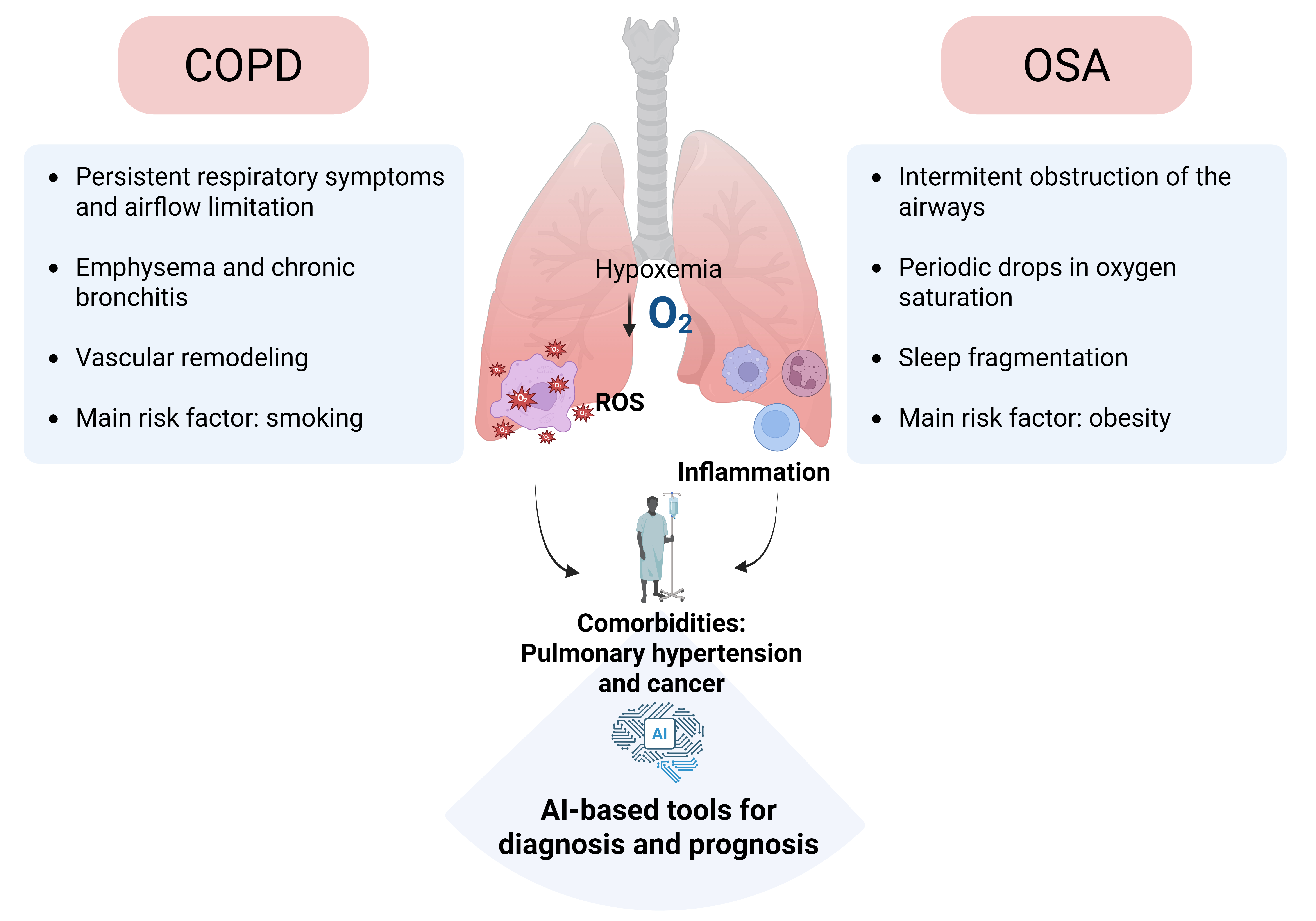

1. Introduction

2. Role of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in CRDS

3. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Comorbidities of Hypoxemic Respiratory Diseases (COPD and OSA)

3.1. Role of Inflammation in Cancer Associated with Respiratory Diseases

3.2. Role of Inflammation in Cardiovascular Complications Associated to CRDs

3.3. Role of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Pulmonary Hypertension Associated to CRDs

4. Transcriptional Response to Sustained and Intermittent Hypoxia in CRDS

4.1. HIF Signaling and Gene Expression Dynamics in Sustained and Intermittent Hypoxia

4.2. Role of HIFs in Vascular Dysfunction in COPD and OSA.

4.3. Role of HIF Pathway in Airway Inflammation

5. Relevance of AI in Respiratory Medicine

5.1. Applications of Traditional Machine Learning in Diagnosis and Prognosis

5.2. Deep Learning Approaches in Diagnosis and Prognosis

5.3. Foundational Models for Diagnosis and Prognosis

5.4. Clinical Databases for COPD and OSA Research

5.5. Risk Assessment of AI for Health. Can AI Be Used as a New Tool in Therapeutic Decision-Making?

5.6. Regulatory Landscape

5.7. Integration of the AI in Practitioner’s Decisions

6. Conclusions, Future Research and Directions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2019 Chronic Respiratory Diseases Collaborators. Global burden of chronic respiratory diseases and risk factors, 1990-2019: an update from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;59:101936.

- Soriano JB, Alfageme I, Miravitlles M, de Lucas P, Soler-Cataluña JJ, García-Río F, et al. Prevalence and Determinants of COPD in Spain: EPISCAN II. Arch Bronconeumol. 2021;57:61–9.

- Safiri S, Carson-Chahhoud K, Noori M, Nejadghaderi SA, Sullman MJM, Ahmadian Heris J, et al. Burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its attributable risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ. 2022;378:e069679.

- Benjafield A V, Ayas NT, Eastwood PR, Heinzer R, Ip MSM, Morrell MJ, et al. Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: a literature-based analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7:687–98.

- Bagdonas E, Raudoniute J, Bruzauskaite I, Aldonyte R. Novel aspects of pathogenesis and regeneration mechanisms in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:995–1013.

- Duijts L, Reiss IK, Brusselle G, de Jongste JC. Early origins of chronic obstructive lung diseases across the life course. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29:871–85.

- Fonseca W, Lukacs NW, Elesela S, Malinczak C-A. Role of ILC2 in Viral-Induced Lung Pathogenesis. Front Immunol. 2021;12:675169.

- MacNee W. Pulmonary and systemic oxidant/antioxidant imbalance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:50–60.

- Sevilla-Montero J, Munar-Rubert O, Pino-Fadón J, Aguilar-Latorre C, Villegas-Esguevillas M, Climent B, et al. Cigarette smoke induces pulmonary arterial dysfunction through an imbalance in the redox status of the soluble guanylyl cyclase. Free Radic Biol Med. 2022;193:9–22.

- Garcia-Rio F, Miravitlles M, Soriano JB, Muñoz L, Duran-Tauleria E, Sánchez G, et al. Systemic inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population-based study. Respir Res. 2010;11:63.

- Divo MJ, Casanova C, Marin JM, Pinto-Plata VM, de-Torres JP, Zulueta JJ, et al. COPD comorbidities network. Eur Respir J. 2015;46:640–50.

- Smith MC, Wrobel JP. Epidemiology and clinical impact of major comorbidities in patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:871–88.

- Santiago Díaz C, Medrano FJ, Muñoz-Rivas N, Castilla Guerra L, Alonso Ortiz MB, en representación de los grupos de trabajo de EPOC y de Riesgo Vascular de la Sociedad Española de Medicina Interna. COPD and cardiovascular risk. Clin Investig Arterioscler. 2025;500757.

- Polman R, Hurst JR, Uysal OF, Mandal S, Linz D, Simons S. Cardiovascular disease and risk in COPD: a state of the art review. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2024;22:177–91.

- Camiciottoli G, Bigazzi F, Magni C, Bonti V, Diciotti S, Bartolucci M, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities according to predominant phenotype and severity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:2229–36.

- Safiri S, Carson-Chahhoud K, Noori M, Nejadghaderi SA, Sullman MJM, Ahmadian Heris J, et al. Burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its attributable risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ. 2022;378:e069679.

- Gottlieb DJ, Punjabi NM. Diagnosis and Management of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Review. JAMA. 2020;323:1389–400.

- Parra O, Arboix A, Montserrat JM, Quintó L, Bechich S, García-Eroles L. Sleep-related breathing disorders: impact on mortality of cerebrovascular disease. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:267–72.

- Martínez-García MA, Soler-Cataluña JJ, Ejarque-Martínez L, Soriano Y, Román-Sánchez P, Illa FB, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure treatment reduces mortality in patients with ischemic stroke and obstructive sleep apnea: a 5-year follow-up study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:36–41.

- Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Vicente E, Agusti AGN. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study. Lancet. 2005;365:1046–53.

- Labarca G, Vena D, Hu W-H, Esmaeili N, Gell L, Yang HC, et al. Sleep Apnea Physiological Burdens and Cardiovascular Morbidity and Mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;208:802–13.

- Martínez Cerón E, Casitas Mateos R, García-Río F. Sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome and type 2 diabetes. A reciprocal relationship? Arch Bronconeumol. 2015;51:128–39.

- Nieto FJ, Young TB, Lind BK, Shahar E, Samet JM, Redline S, et al. Association of sleep-disordered breathing, sleep apnea, and hypertension in a large community-based study. Sleep Heart Health Study. JAMA. 2000;283:1829–36.

- Loke YK, Brown JWL, Kwok CS, Niruban A, Myint PK. Association of obstructive sleep apnea with risk of serious cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:720–8.

- Cai A, Wang L, Zhou Y. Hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea. Hypertens Res. 2016;39:391–5.

- Nakanishi R, Baskaran L, Gransar H, Budoff MJ, Achenbach S, Al-Mallah M, et al. Relationship of Hypertension to Coronary Atherosclerosis and Cardiac Events in Patients With Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography. Hypertension. 2017;70:293–9.

- Al-Mashhadi RH, Al-Mashhadi AL, Nasr ZP, Mortensen MB, Lewis EA, Camafeita E, et al. Local Pressure Drives Low-Density Lipoprotein Accumulation and Coronary Atherosclerosis in Hypertensive Minipigs. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:575–89.

- Baguet J-P, Hammer L, Lévy P, Pierre H, Launois S, Mallion J-M, et al. The severity of oxygen desaturation is predictive of carotid wall thickening and plaque occurrence. Chest. 2005;128:3407–12.

- Savransky V, Nanayakkara A, Li J, Bevans S, Smith PL, Rodriguez A, et al. Chronic intermittent hypoxia induces atherosclerosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:1290–7.

- Campos-Rodriguez F, Martinez-Garcia MA, Martinez M, Duran-Cantolla J, Peña M de la, Masdeu MJ, et al. Association between obstructive sleep apnea and cancer incidence in a large multicenter Spanish cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:99–105.

- Martinez-Garcia MA, Campos-Rodriguez F, Almendros I, Garcia-Rio F, Sanchez-de-la-Torre M, Farre R, et al. Cancer and Sleep Apnea: Cutaneous Melanoma as a Case Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200:1345–53.

- Cubillos-Zapata C, Martínez-García MÁ, Campos-Rodríguez F, Sánchez de la Torre M, Nagore E, Martorell-Calatayud A, et al. Soluble PD-L1 is a potential biomarker of cutaneous melanoma aggressiveness and metastasis in obstructive sleep apnoea patients. Eur Respir J. 2019;53.

- Cubillos-Zapata C, Martínez-García MÁ, Díaz-García E, Jaureguizar A, Campos-Rodríguez F, Sánchez-de-la-Torre M, et al. Obesity attenuates the effect of sleep apnea on active TGF-ß1 levels and tumor aggressiveness in patients with melanoma. Sci Rep. 2020;10:15528.

- Cubillos-Zapata C, Martínez-García MÁ, Díaz-García E, Toledano V, Campos-Rodríguez F, Sánchez-de-la-Torre M, et al. Proangiogenic factor midkine is increased in melanoma patients with sleep apnea and induces tumor cell proliferation. The FASEB Journal. 2020;34:16179–90.

- Olszewska E, Rogalska J, Brzóska MM. The Association of Oxidative Stress in the Uvular Mucosa with Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome: A Clinical Study. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1132.

- Sanchez-Azofra A, Gu W, Masso-Silva JA, Sanz-Rubio D, Marin-Oto M, Cubero P, et al. Inflammation biomarkers in OSA, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/OSA overlap syndrome. J Clin Sleep Med. 2023;19:1447–56.

- Ratcliffe PJ. Oxygen sensing and hypoxia signalling pathways in animals: the implications of physiology for cancer. J Physiol. 2013;591:2027–42.

- Luo Z, Tian M, Yang G, Tan Q, Chen Y, Li G, et al. Hypoxia signaling in human health and diseases: implications and prospects for therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7:218.

- Chen Z, Hao J, Sun H, Li M, Zhang Y, Qian Q. Applications of digital health technologies and artificial intelligence algorithms in COPD: systematic review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2025;25:77.

- Bazoukis G, Bollepalli SC, Chung CT, Li X, Tse G, Bartley BL, et al. Application of artificial intelligence in the diagnosis of sleep apnea. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2023;19:1337–63.

- Smith LA, Oakden-Rayner L, Bird A, Zeng M, To M-S, Mukherjee S, et al. Machine learning and deep learning predictive models for long-term prognosis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Digit Health. 2023;5:e872–81.

- Vigil L, Zapata T, Grau A, Bonet M, Montaña M, Piñar M. Innovación en sueño. Open Respiratory Archives. 2024;6:100402.

- LeCun Y, Bengio Y, Hinton G. Deep learning. Nature. 2015;521:436–44.

- Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention Is All You Need. 2017;

- Meliante PG, Zoccali F, Cascone F, Di Stefano V, Greco A, de Vincentiis M, et al. Molecular Pathology, Oxidative Stress, and Biomarkers in Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24.

- Lavalle S, Masiello E, Iannella G, Magliulo G, Pace A, Lechien JR, et al. Unraveling the Complexities of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Biomarkers in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review. Life (Basel). 2024;14.

- Antosova M, Mokra D, Pepucha L, Plevkova J, Buday T, Sterusky M, et al. Physiology of nitric oxide in the respiratory system. Physiol Res. 2017;66:S159–72.

- Bernard K, Hecker L, Luckhardt TR, Cheng G, Thannickal VJ. NADPH oxidases in lung health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:2838–53.

- Al Ghouleh I, Khoo NKH, Knaus UG, Griendling KK, Touyz RM, Thannickal VJ, et al. Oxidases and peroxidases in cardiovascular and lung disease: new concepts in reactive oxygen species signaling. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1271–88.

- Chen W, Zhang W. Association between oxidative balance score and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A cross-sectional study. Medicine. 2024;103:e39883.

- Liu X, Hao B, Ma A, He J, Liu X, Chen J. The Expression of NOX4 in Smooth Muscles of Small Airway Correlates with the Disease Severity of COPD. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:1–17.

- Wang X, Murugesan P, Zhang P, Xu S, Peng L, Wang C, et al. NADPH Oxidase Isoforms in COPD Patients and Acute Cigarette Smoke-Exposed Mice: Induction of Oxidative Stress and Lung Inflammation. Antioxidants. 2022;11:1539.

- Alateeq R, Akhtar A, De Luca SN, Chan SMH, Vlahos R. Apocynin Prevents Cigarette Smoke-Induced Anxiety-Like Behavior and Preserves Microglial Profiles in Male Mice. Antioxidants. 2024;13:855.

- Hogg JC, Chu F, Utokaparch S, Woods R, Elliott WM, Buzatu L, et al. The Nature of Small-Airway Obstruction in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;350:2645–53.

- Brusselle GG, Joos GF, Bracke KR. New insights into the immunology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Lancet. 2011;378:1015–26.

- Barnes PJ. Inflammatory mechanisms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2016;138:16–27.

- Zuo L, He F, Sergakis GG, Koozehchian MS, Stimpfl JN, Rong Y, et al. Interrelated role of cigarette smoking, oxidative stress, and immune response in COPD and corresponding treatments. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2014;307:L205–18.

- Gan WQ. Association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and systemic inflammation: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Thorax. 2004;59:574–80.

- Agustí A, Edwards LD, Rennard SI, MacNee W, Tal-Singer R, Miller BE, et al. Persistent Systemic Inflammation is Associated with Poor Clinical Outcomes in COPD: A Novel Phenotype. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37483.

- Thomsen M, Dahl M, Lange P, Vestbo J, Nordestgaard BG. Inflammatory Biomarkers and Comorbidities in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:982–8.

- Mastino P, Rosati D, de Soccio G, Romeo M, Pentangelo D, Venarubea S, et al. Oxidative Stress in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome: Putative Pathways to Hearing System Impairment. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023;12.

- Abourjeili J, Salameh E, Noureddine M, Bou Khalil P, Eid AA. Obstructive sleep apnea: Beyond the dogma of obesity! Respir Med. 2024;222:107512.

- Alharbi KS, Fuloria NK, Fuloria S, Rahman SB, Al-Malki WH, Javed Shaikh MA, et al. Nuclear factor-kappa B and its role in inflammatory lung disease. Chem Biol Interact. 2021;345:109568.

- Israel LP, Benharoch D, Gopas J, Goldbart AD. A Pro-Inflammatory Role for Nuclear Factor Kappa B in Childhood Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. Sleep. 2013;36:1947–55.

- Qiu X, Yao Y, Chen Y, Li Y, Sun X, Zhu X. TRPC5 Promotes Intermittent Hypoxia-Induced Cardiomyocyte Injury Through Oxidative Stress. Nat Sci Sleep. 2024;16:2125–41.

- Karamanlı H, Özol D, Ugur KS, Yıldırım Z, Armutçu F, Bozkurt B, et al. Influence of CPAP treatment on airway and systemic inflammation in OSAS patients. Sleep and Breathing. 2014;18:251–6.

- Celec P, Jurkovičová I, Buchta R, Bartík I, Gardlík R, Pálffy R, et al. Antioxidant vitamins prevent oxidative and carbonyl stress in an animal model of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep and Breathing. 2013;17:867–71.

- Jang B-K, Lee J-W, Choi H, Yim S-V. Aronia melanocarpa Fruit Bioactive Fraction Attenuates LPS-Induced Inflammatory Response in Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells. Antioxidants. 2020;9:816.

- Jelska A, Polecka A, Zahorodnii A, Olszewska E. The Role of Oxidative Stress and the Potential Therapeutic Benefits of Aronia melanocarpa Supplementation in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Antioxidants (Basel). 2024;13.

- Ai L, Li Y, Liu Z, Li R, Wang X, Hai B. Tempol attenuates chronic intermittent hypoxia-induced lung injury through the miR-145-5p/Nrf2 signaling pathway. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2023;69:225–34.

- Greten FR, Grivennikov SI. Inflammation and Cancer: Triggers, Mechanisms, and Consequences. Immunity. 2019;51:27–41.

- Kay J, Thadhani E, Samson L, Engelward B. Inflammation-induced DNA damage, mutations and cancer. DNA Repair (Amst). 2019;83:102673.

- Fang L, Liu K, Liu C, Wang X, Ma W, Xu W, et al. Tumor accomplice: T cell exhaustion induced by chronic inflammation. Front Immunol. 2022;13.

- Vicente E, Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Osuna CS, González R, Marin-Oto M, et al. Upper airway and systemic inflammation in obstructive sleep apnoea. European Respiratory Journal. 2016;48:1108–17.

- Houghton AM. Mechanistic links between COPD and lung cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:233–45.

- Dubinett SM, Spira AE. Impact of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease on Immune-based Treatment for Lung Cancer. Moving toward Disease Interception. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:278–80.

- Zaynagetdinov R, Sherrill TP, Gleaves LA, Hunt P, Han W, McLoed AG, et al. Chronic NF-κB activation links COPD and lung cancer through generation of an immunosuppressive microenvironment in the lungs. Oncotarget. 2016;7:5470–82.

- Forder A, Zhuang R, Souza VGP, Brockley LJ, Pewarchuk ME, Telkar N, et al. Mechanisms Contributing to the Comorbidity of COPD and Lung Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:2859.

- Díaz-García E, García-Tovar S, Casitas R, Jaureguizar A, Zamarrón E, Sánchez-Sánchez B, et al. Intermittent Hypoxia Mediates Paraspeckle Protein-1 Upregulation in Sleep Apnea. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:3888.

- Cubillos-Zapata C, Martínez-García MÁ, Díaz-García E, García-Tovar S, Campos-Rodríguez F, Sánchez-de-la-Torre M, et al. Obstructive sleep apnoea is related to melanoma aggressiveness through paraspeckle protein-1 upregulation. European Respiratory Journal. 2023;61:2200707.

- Gozal D, Lipton AJ, Jones KL. Circulating Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Levels in Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Sleep. 2002;25:59–65.

- Díaz-García E, García-Sánchez A, Alfaro E, López-Fernández C, Mañas E, Cano-Pumarega I, et al. PSGL-1: a novel immune checkpoint driving T-cell dysfunction in obstructive sleep apnea. Front Immunol. 2023;14.

- Hernández-Jiménez E, Cubillos-Zapata C, Toledano V, Pérez de Diego R, Fernández-Navarro I, Casitas R, et al. Monocytes inhibit NK activity via TGF-β in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea. European Respiratory Journal. 2017;49:1602456.

- Verduzco D, Lloyd M, Xu L, Ibrahim-Hashim A, Balagurunathan Y, Gatenby RA, et al. Intermittent Hypoxia Selects for Genotypes and Phenotypes That Increase Survival, Invasion, and Therapy Resistance. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120958.

- Almendros I, Wang Y, Becker L, Lennon FE, Zheng J, Coats BR, et al. Intermittent Hypoxia-induced Changes in Tumor-associated Macrophages and Tumor Malignancy in a Mouse Model of Sleep Apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:593–601.

- Pahwa R, Goyal A, Jialal I. Chronic Inflammation. 2025.

- Abderrazak A, Syrovets T, Couchie D, El Hadri K, Friguet B, Simmet T, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome: From a danger signal sensor to a regulatory node of oxidative stress and inflammatory diseases. Redox Biol. 2015;4:296–307.

- Kim J, Kim H-S, Chung JH. Molecular mechanisms of mitochondrial DNA release and activation of the cGAS-STING pathway. Exp Mol Med. 2023;55:510–9.

- Sharma BR, Kanneganti T-D. NLRP3 inflammasome in cancer and metabolic diseases. Nat Immunol. 2021;22:550–9.

- Lamkanfi M, Dixit VM. Mechanisms and Functions of Inflammasomes. Cell. 2014;157:1013–22.

- Gupta N, Sahu A, Prabhakar A, Chatterjee T, Tyagi T, Kumari B, et al. Activation of NLRP3 inflammasome complex potentiates venous thrombosis in response to hypoxia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2017;114:4763–8.

- Li Y, Huang H, Liu B, Zhang Y, Pan X, Yu X-Y, et al. Inflammasomes as therapeutic targets in human diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:247.

- Youm Y-H, Grant RW, McCabe LR, Albarado DC, Nguyen KY, Ravussin A, et al. Canonical Nlrp3 Inflammasome Links Systemic Low-Grade Inflammation to Functional Decline in Aging. Cell Metab. 2013;18:519–32.

- Sutterwala FS, Ogura Y, Flavell RA. The inflammasome in pathogen recognition and inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:259–64.

- Campo G, Pavasini R, Malagù M, Mascetti S, Biscaglia S, Ceconi C, et al. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Ischemic Heart Disease Comorbidity: Overview of Mechanisms and Clinical Management. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2015;29:147–57.

- Divo M, Cote C, de Torres JP, Casanova C, Marin JM, Pinto-Plata V, et al. Comorbidities and Risk of Mortality in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:155–61.

- Goedemans L, Bax JJ, Delgado V. COPD and acute myocardial infarction. European Respiratory Review. 2020;29:190139.

- Onishi K. Total management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease. J Cardiol. 2017;70:128–34.

- Morgan AD, Zakeri R, Quint JK. Defining the relationship between COPD and CVD: what are the implications for clinical practice? Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2018;12.

- Chen W, Thomas J, Sadatsafavi M, FitzGerald JM. Risk of cardiovascular comorbidity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:631–9.

- Kheirandish-Gozal L, Gozal D. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Inflammation: Proof of Concept Based on Two Illustrative Cytokines. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:459.

- Yeghiazarians Y, Jneid H, Tietjens JR, Redline S, Brown DL, El-Sherif N, et al. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;144.

- Tietjens JR, Claman D, Kezirian EJ, De Marco T, Mirzayan A, Sadroonri B, et al. Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Cardiovascular Disease: A Review of the Literature and Proposed Multidisciplinary Clinical Management Strategy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8.

- Yang L, Zhang H, Cai M, Zou Y, Jiang X, Song L, et al. Effect of spironolactone on patients with resistant hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2016;38:464–8.

- Gong T, Liu L, Jiang W, Zhou R. DAMP-sensing receptors in sterile inflammation and inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:95–112.

- Lavie L, Lavie P. Molecular mechanisms of cardiovascular disease in OSAHS: the oxidative stress link. European Respiratory Journal. 2009;33:1467–84.

- Feres MC, Fonseca FAH, Cintra FD, Mello-Fujita L, de Souza AL, De Martino MC, et al. An assessment of oxidized LDL in the lipid profiles of patients with obstructive sleep apnea and its association with both hypertension and dyslipidemia, and the impact of treatment with CPAP. Atherosclerosis. 2015;241:342–9.

- Imamura T, Poulsen O, Haddad GG. Intermittent hypoxia induces murine macrophage foam cell formation by IKK-β-dependent NF-κB pathway activation. J Appl Physiol. 2016;121:670–7.

- Díaz-García E, García-Tovar S, Alfaro E, Jaureguizar A, Casitas R, Sánchez-Sánchez B, et al. Inflammasome Activation: A Keystone of Proinflammatory Response in Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205:1337–48.

- Díaz-García E, Sanz-Rubio D, García-Tovar S, Alfaro E, Cubero P, Gil A V., et al. Inflammasome activation mediated by oxidised low-density lipoprotein in patients with sleep apnoea and early subclinical atherosclerosis. European Respiratory Journal. 2023;61:2201401.

- Wolf D, Ley K. Immunity and Inflammation in Atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2019;124:315–27.

- Simonneau G, Montani D, Celermajer DS, Denton CP, Gatzoulis MA, Krowka M, et al. Haemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;53.

- Kovacs G, Bartolome S, Denton CP, Gatzoulis MA, Gu S, Khanna D, et al. Definition, classification and diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2024;64.

- Krompa A, Marino P. Diagnosis and management of pulmonary hypertension related to chronic respiratory disease. Breathe (Sheff). 2022;18:220205.

- McNicholas WT. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and obstructive sleep apnea: overlaps in pathophysiology, systemic inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:692–700.

- Stenmark KR, Meyrick B, Galie N, Mooi WJ, McMurtry IF. Animal models of pulmonary arterial hypertension: the hope for etiological discovery and pharmacological cure. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L1013-32.

- Pugliese SC, Poth JM, Fini MA, Olschewski A, El Kasmi KC, Stenmark KR. The role of inflammation in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension: from cellular mechanisms to clinical phenotypes. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;308:L229-52.

- Frazziano G, Moreno L, Moral-Sanz J, Menendez C, Escolano L, Gonzalez C, et al. Neutral sphingomyelinase, NADPH oxidase and reactive oxygen species. Role in acute hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:2633–40.

- Villamor E, Moreno L, Mohammed R, Pérez-Vizcaíno F, Cogolludo A. Reactive oxygen species as mediators of oxygen signaling during fetal-to-neonatal circulatory transition. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;142:82–96.

- Hernansanz-Agustín P, Choya-Foces C, Carregal-Romero S, Ramos E, Oliva T, Villa-Piña T, et al. Na+ controls hypoxic signalling by the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Nature. 2020;586:287–91.

- Pak O, Scheibe S, Esfandiary A, Gierhardt M, Sydykov A, Logan A, et al. Impact of the mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ on hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2018;51.

- Smith KA, Schumacker PT. Sensors and signals: the role of reactive oxygen species in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. J Physiol. 2019;597:1033–43.

- Adesina SE, Kang B-Y, Bijli KM, Ma J, Cheng J, Murphy TC, et al. Targeting mitochondrial reactive oxygen species to modulate hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;87:36–47.

- Yan S, Sheak JR, Walker BR, Jernigan NL, Resta TC. Contribution of Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species to Chronic Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023;12.

- Liu JQ, Erbynn EM, Folz RJ. Chronic hypoxia-enhanced murine pulmonary vasoconstriction: role of superoxide and gp91phox. Chest. 2005;128:594S-596S.

- Li X, Zhang X, Hou X, Bing X, Zhu F, Wu X, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea-increased DEC1 regulates systemic inflammation and oxidative stress that promotes development of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Apoptosis. 2023;28:432–46.

- Nisbet RE, Graves AS, Kleinhenz DJ, Rupnow HL, Reed AL, Fan T-HM, et al. The role of NADPH oxidase in chronic intermittent hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40:601–9.

- Mei L, Zheng Y-M, Song T, Yadav VR, Joseph LC, Truong L, et al. Rieske iron-sulfur protein induces FKBP12.6/RyR2 complex remodeling and subsequent pulmonary hypertension through NF-κB/cyclin D1 pathway. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3527.

- Nagaraj C, Tabeling C, Nagy BM, Jain PP, Marsh LM, Papp R, et al. Hypoxic vascular response and ventilation/perfusion matching in end-stage COPD may depend on p22phox. Eur Respir J. 2017;50.

- Gonzalez-Gonzalez FJ, Chandel NS, Jain M, Budinger GRS. Reactive oxygen species as signaling molecules in the development of lung fibrosis. Transl Res. 2017;190:61–8.

- Kinnula VL, Fattman CL, Tan RJ, Oury TD. Oxidative stress in pulmonary fibrosis: a possible role for redox modulatory therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:417–22.

- Bellocq A, Azoulay E, Marullo S, Flahault A, Fouqueray B, Philippe C, et al. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates increase transforming growth factor-beta1 release from human epithelial alveolar cells through two different mechanisms. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;21:128–36.

- Hemnes AR, Zaiman A, Champion HC. PDE5A inhibition attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis and pulmonary hypertension through inhibition of ROS generation and RhoA/Rho kinase activation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:L24-33.

- Behnke J, Dippel CM, Choi Y, Rekers L, Schmidt A, Lauer T, et al. Oxygen Toxicity to the Immature Lung-Part II: The Unmet Clinical Need for Causal Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22.

- Wedgwood S, Steinhorn RH. Role of reactive oxygen species in neonatal pulmonary vascular disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;21:1926–42.

- Huizing MJ, Cavallaro G, Moonen RM, González-Luis GE, Mosca F, Vento M, et al. Is the C242T Polymorphism of the CYBA Gene Linked with Oxidative Stress-Associated Complications of Prematurity? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2017;27:1432–8.

- Wang R-R, Yuan T-Y, Wang J-M, Chen Y-C, Zhao J-L, Li M-T, et al. Immunity and inflammation in pulmonary arterial hypertension: From pathophysiology mechanisms to treatment perspective. Pharmacol Res. 2022;180:106238.

- Ye Y, Xu Q, Wuren T. Inflammation and immunity in the pathogenesis of hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1162556.

- Lin D, Hu L, Wei D, Li Y, Yu Y, Wang Q, et al. Peli1 Deficiency in Macrophages Attenuates Pulmonary Hypertension by Enhancing Foxp1-Mediated Transcriptional Inhibition of IL-6. Hypertension. 2025;82:445–59.

- Savale L, Tu L, Rideau D, Izziki M, Maitre B, Adnot S, et al. Impact of interleukin-6 on hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension and lung inflammation in mice. Respir Res. 2009;10:6.

- Hashimoto-Kataoka T, Hosen N, Sonobe T, Arita Y, Yasui T, Masaki T, et al. Interleukin-6/interleukin-21 signaling axis is critical in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E2677-86.

- Amsellem V, Abid S, Poupel L, Parpaleix A, Rodero M, Gary-Bobo G, et al. Roles for the CX3CL1/CX3CR1 and CCL2/CCR2 Chemokine Systems in Hypoxic Pulmonary Hypertension. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2017;56:597–608.

- Kumar R, Nolan K, Kassa B, Chanana N, Palmo T, Sharma K, et al. Monocytes and interstitial macrophages contribute to hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2025;135.

- Yu Y-RA, Malakhau Y, Yu C-HA, Phelan S-LJ, Cumming RI, Kan MJ, et al. Nonclassical Monocytes Sense Hypoxia, Regulate Pulmonary Vascular Remodeling, and Promote Pulmonary Hypertension. J Immunol. 2020;204:1474–85.

- Kumar R, Mickael C, Kassa B, Gebreab L, Robinson JC, Koyanagi DE, et al. TGF-β activation by bone marrow-derived thrombospondin-1 causes Schistosoma- and hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15494.

- Vergadi E, Chang MS, Lee C, Liang OD, Liu X, Fernandez-Gonzalez A, et al. Early macrophage recruitment and alternative activation are critical for the later development of hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2011;123:1986–95.

- Kumar R, Mickael C, Kassa B, Sanders L, Hernandez-Saavedra D, Koyanagi DE, et al. Interstitial macrophage-derived thrombospondin-1 contributes to hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116:2021–30.

- Maston LD, Jones DT, Giermakowska W, Howard TA, Cannon JL, Wang W, et al. Central role of T helper 17 cells in chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2017;312:L609–24.

- Sevilla-Montero J, Labrousse-Arias D, Fernández-Pérez C, Fernández-Blanco L, Barreira B, Mondéjar-Parreño G, et al. Cigarette Smoke Directly Promotes Pulmonary Arterial Remodeling and Kv7.4 Channel Dysfunction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203:1290–305.

- Truong LN, Wilson Santos E, Zheng Y-M, Wang Y-X. Rieske Iron-Sulfur Protein Mediates Pulmonary Hypertension Following Nicotine/Hypoxia Coexposure. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2024;70:193–202.

- Kim BS, Serebreni L, Hamdan O, Wang L, Parniani A, Sussan T, et al. Xanthine oxidoreductase is a critical mediator of cigarette smoke-induced endothelial cell DNA damage and apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;60:336–46.

- Peinado VI, Barberá JA, Abate P, Ramírez J, Roca J, Santos S, et al. Inflammatory reaction in pulmonary muscular arteries of patients with mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1605–11.

- Lim EY, Lee S-Y, Shin HS, Kim G-D. Reactive Oxygen Species and Strategies for Antioxidant Intervention in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023;12.

- Wang J, Dong W. Oxidative stress and bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Gene. 2018;678:177–83.

- Lachmanová V, Hnilicková O, Povýsilová V, Hampl V, Herget J. N-acetylcysteine inhibits hypoxic pulmonary hypertension most effectively in the initial phase of chronic hypoxia. Life Sci. 2005;77:175–82.

- Young KC, Torres E, Hatzistergos KE, Hehre D, Suguihara C, Hare JM. Inhibition of the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis attenuates neonatal hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res. 2009;104:1293–301.

- Fernandez-Gonzalez A, Mukhia A, Nadkarni J, Willis GR, Reis M, Zhumka K, et al. Immunoregulatory Macrophages Modify Local Pulmonary Immunity and Ameliorate Hypoxic Pulmonary Hypertension. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2024;44:e288–303.

- López-Barneo J, González-Rodríguez P, Gao L, Fernández-Agüera MC, Pardal R, Ortega-Sáenz P. Oxygen sensing by the carotid body: mechanisms and role in adaptation to hypoxia. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2016;310:C629-42.

- Ratcliffe PJ. Oxygen sensing and hypoxia signalling pathways in animals: the implications of physiology for cancer. J Physiol. 2013;591:2027–42.

- Pescador N, Villar D, Cifuentes D, Garcia-Rocha M, Ortiz-Barahona A, Vazquez S, et al. Hypoxia promotes glycogen accumulation through hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-mediated induction of glycogen synthase 1. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9644.

- Arias CF, Acosta FJ, Bertocchini F, Fernández-Arias C. Redefining the role of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) in oxygen homeostasis. Commun Biol. 2025;8:446.

- Bishop T, Ratcliffe PJ. Signaling hypoxia by hypoxia-inducible factor protein hydroxylases: a historical overview and future perspectives. Hypoxia (Auckl). 2014;2:197–213.

- Elvidge GP, Glenny L, Appelhoff RJ, Ratcliffe PJ, Ragoussis J, Gleadle JM. Concordant regulation of gene expression by hypoxia and 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase inhibition: the role of HIF-1alpha, HIF-2alpha, and other pathways. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15215–26.

- Rius J, Guma M, Schachtrup C, Akassoglou K, Zinkernagel AS, Nizet V, et al. NF-kappaB links innate immunity to the hypoxic response through transcriptional regulation of HIF-1alpha. Nature. 2008;453:807–11.

- Shakir D, Batie M, Kwok C-S, Kenneth NS, Rocha S. NF-κB is a Central Regulator of Hypoxia-Induced Gene Expression. 2025.

- Li L, Kang H, Zhang Q, D’Agati VD, Al-Awqati Q, Lin F. FoxO3 activation in hypoxic tubules prevents chronic kidney disease. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:2374–89.

- Jensen KS, Binderup T, Jensen KT, Therkelsen I, Borup R, Nilsson E, et al. FoxO3A promotes metabolic adaptation to hypoxia by antagonizing Myc function. EMBO J. 2011;30:4554–70.

- Gustafsson M V, Zheng X, Pereira T, Gradin K, Jin S, Lundkvist J, et al. Hypoxia requires notch signaling to maintain the undifferentiated cell state. Dev Cell. 2005;9:617–28.

- Laderoute KR, Calaoagan JM, Gustafson-Brown C, Knapp AM, Li G-C, Mendonca HL, et al. The response of c-jun/AP-1 to chronic hypoxia is hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha dependent. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:2515–23.

- Michiels C, Minet E, Michel G, Mottet D, Piret JP, Raes M. HIF-1 and AP-1 cooperate to increase gene expression in hypoxia: role of MAP kinases. IUBMB Life. 2001;52:49–53.

- Villar D, Ortiz-Barahona A, Gómez-Maldonado L, Pescador N, Sánchez-Cabo F, Hackl H, et al. Cooperativity of stress-responsive transcription factors in core hypoxia-inducible factor binding regions. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45708.

- Ma B, Chen Y, Chen L, Cheng H, Mu C, Li J, et al. Hypoxia regulates Hippo signalling through the SIAH2 ubiquitin E3 ligase. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:95–103.

- Wu Z, Zhu L, Nie X, Wei L, Qi Y. USP15 promotes pulmonary vascular remodeling in pulmonary hypertension in a YAP1/TAZ-dependent manner. Exp Mol Med. 2023;55:183–95.

- Chen J, Lockett A, Zhao S, Huang LS, Wang Y, Wu W, et al. Sphingosine Kinase 1 Deficiency in Smooth Muscle Cells Protects against Hypoxia-Mediated Pulmonary Hypertension via YAP1 Signaling. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23.

- Islam R, Hong Z. YAP/TAZ as mechanobiological signaling pathway in cardiovascular physiological regulation and pathogenesis. Mechanobiology in medicine. 2024;2.

- Sermeus A, Michiels C. Reciprocal influence of the p53 and the hypoxic pathways. Cell Death Dis. 2011;2:e164.

- Potteti HR, Noone PM, Tamatam CR, Ankireddy A, Noel S, Rabb H, et al. Nrf2 mediates hypoxia-inducible HIF1α activation in kidney tubular epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2021;320:F464–74.

- Bae T, Hallis SP, Kwak M-K. Hypoxia, oxidative stress, and the interplay of HIFs and NRF2 signaling in cancer. Exp Mol Med. 2024;56:501–14.

- Batie M, Frost J, Frost M, Wilson JW, Schofield P, Rocha S. Hypoxia induces rapid changes to histone methylation and reprograms chromatin. Science. 2019;363:1222–6.

- Chakraborty AA, Laukka T, Myllykoski M, Ringel AE, Booker MA, Tolstorukov MY, et al. Histone demethylase KDM6A directly senses oxygen to control chromatin and cell fate. Science. 2019;363:1217–22.

- Kindrick JD, Mole DR. Hypoxic Regulation of Gene Transcription and Chromatin: Cause and Effect. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21.

- Batie M, Rocha S. Gene transcription and chromatin regulation in hypoxia. Biochem Soc Trans. 2020;48:1121–8.

- Romero-Peralta S, García-Rio F, Resano Barrio P, Viejo-Ayuso E, Izquierdo JL, Sabroso R, et al. Defining the Heterogeneity of Sleep Apnea Syndrome: A Cluster Analysis With Implications for Patient Management. Arch Bronconeumol. 2022;58:125–34.

- Ryan S, Taylor CT, McNicholas WT. Selective activation of inflammatory pathways by intermittent hypoxia in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Circulation. 2005;112:2660–7.

- Taylor CT, Kent BD, Crinion SJ, McNicholas WT, Ryan S. Human adipocytes are highly sensitive to intermittent hypoxia induced NF-kappaB activity and subsequent inflammatory gene expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;447:660–5.

- Yu AY, Shimoda LA, Iyer N V, Huso DL, Sun X, McWilliams R, et al. Impaired physiological responses to chronic hypoxia in mice partially deficient for hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:691–6.

- Brusselmans K, Compernolle V, Tjwa M, Wiesener MS, Maxwell PH, Collen D, et al. Heterozygous deficiency of hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha protects mice against pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular dysfunction during prolonged hypoxia. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1519–27.

- Sheikh AQ, Saddouk FZ, Ntokou A, Mazurek R, Greif DM. Cell Autonomous and Non-cell Autonomous Regulation of SMC Progenitors in Pulmonary Hypertension. Cell Rep. 2018;23:1152–65.

- Kapitsinou PP, Rajendran G, Astleford L, Michael M, Schonfeld MP, Fields T, et al. The Endothelial Prolyl-4-Hydroxylase Domain 2/Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 2 Axis Regulates Pulmonary Artery Pressure in Mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2016;36:1584–94.

- Pullamsetti SS, Mamazhakypov A, Weissmann N, Seeger W, Savai R. Hypoxia-inducible factor signaling in pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:5638–51.

- Hu C-J, Poth JM, Zhang H, Flockton A, Laux A, Kumar S, et al. Suppression of HIF2 signalling attenuates the initiation of hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;54.

- Dai Z, Li M, Wharton J, Zhu MM, Zhao Y-Y. Prolyl-4 Hydroxylase 2 (PHD2) Deficiency in Endothelial Cells and Hematopoietic Cells Induces Obliterative Vascular Remodeling and Severe Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension in Mice and Humans Through Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-2α. Circulation. 2016;133:2447–58.

- Cowburn AS, Crosby A, Macias D, Branco C, Colaço RDDR, Southwood M, et al. HIF2α-arginase axis is essential for the development of pulmonary hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:8801–6.

- Wang S, Zeng H, Xie X-J, Tao Y-K, He X, Roman RJ, et al. Loss of prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2 in vascular endothelium increases pericyte coverage and promotes pulmonary arterial remodeling. Oncotarget. 2016;7:58848–61.

- Gale DP, Harten SK, Reid CDL, Tuddenham EGD, Maxwell PH. Autosomal dominant erythrocytosis and pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with an activating HIF2 alpha mutation. Blood. 2008;112:919–21.

- Tan Q, Kerestes H, Percy MJ, Pietrofesa R, Chen L, Khurana TS, et al. Erythrocytosis and pulmonary hypertension in a mouse model of human HIF2A gain of function mutation. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:17134–44.

- Urrutia AA, Aragonés J. HIF Oxygen Sensing Pathways in Lung Biology. Biomedicines. 2018;6.

- Pasupneti S, Tian W, Tu AB, Dahms P, Granucci E, Gandjeva A, et al. Endothelial HIF-2α as a Key Endogenous Mediator Preventing Emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:983–95.

- Yoo S, Takikawa S, Geraghty P, Argmann C, Campbell J, Lin L, et al. Integrative analysis of DNA methylation and gene expression data identifies EPAS1 as a key regulator of COPD. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1004898.

- Prabhakar NR, Peng Y-J, Nanduri J. Hypoxia-inducible factors and obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:5042–51.

- Yuan G, Khan SA, Luo W, Nanduri J, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 mediates increased expression of NADPH oxidase-2 in response to intermittent hypoxia. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:2925–33.

- Nanduri J, Wang N, Yuan G, Khan SA, Souvannakitti D, Peng Y-J, et al. Intermittent hypoxia degrades HIF-2alpha via calpains resulting in oxidative stress: implications for recurrent apnea-induced morbidities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1199–204.

- Zhang S, Zhao Y, Dong Z, Jin M, Lu Y, Xu M, et al. HIF-1α mediates hypertension and vascular remodeling in sleep apnea via hippo-YAP pathway activation. Mol Med. 2024;30:281.

- Torres-Capelli M, Marsboom G, Li QOY, Tello D, Rodriguez FM, Alonso T, et al. Role Of Hif2α Oxygen Sensing Pathway In Bronchial Epithelial Club Cell Proliferation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25357.

- Woodruff PG, Agusti A, Roche N, Singh D, Martinez FJ. Current concepts in targeting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease pharmacotherapy: making progress towards personalised management. Lancet. 2015;385:1789–98.

- Han J, Wan Q, Seo G-Y, Kim K, El Baghdady S, Lee JH, et al. Hypoxia induces adrenomedullin from lung epithelia, stimulating ILC2 inflammation and immunity. J Exp Med. 2022;219.

- Flayer CH, Linderholm AL, Ge MQ, Juarez M, Franzi L, Tham T, et al. COPD with elevated sputum group 2 innate lymphoid cells is characterized by severe disease. medRxiv. 2024;

- Meng D-Q, Li X-J, Song X-Y, Xin J-B, Yang W-B. Diagnostic and prognostic value of plasma adrenomedullin in COPD exacerbation. Respir Care. 2014;59:1542–9.

- Stolz D, Christ-Crain M, Morgenthaler NG, Miedinger D, Leuppi J, Müller C, et al. Plasma pro-adrenomedullin but not plasma pro-endothelin predicts survival in exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 2008;134:263–72.

- Cramer T, Yamanishi Y, Clausen BE, Förster I, Pawlinski R, Mackman N, et al. HIF-1alpha is essential for myeloid cell-mediated inflammation. Cell. 2003;112:645–57.

- Takeda N, O’Dea EL, Doedens A, Kim J, Weidemann A, Stockmann C, et al. Differential activation and antagonistic function of HIF-{alpha} isoforms in macrophages are essential for NO homeostasis. Genes Dev. 2010;24:491–501.

- Zhang W, Li Q, Li D, Li J, Aki D, Liu Y-C. The E3 ligase VHL controls alveolar macrophage function via metabolic-epigenetic regulation. J Exp Med. 2018;215:3180–93.

- Izquierdo HM, Brandi P, Gómez M-J, Conde-Garrosa R, Priego E, Enamorado M, et al. Von Hippel-Lindau Protein Is Required for Optimal Alveolar Macrophage Terminal Differentiation, Self-Renewal, and Function. Cell Rep. 2018;24:1738–46.

- Wu J, Zhao X, Xiao C, Xiong G, Ye X, Li L, et al. The role of lung macrophages in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2022;205:107035.

- Talker L, Dogan C, Neville D, Lim RH, Broomfield H, Lambert G, et al. Diagnosis and Severity Assessment of COPD Using a Novel Fast-Response Capnometer and Interpretable Machine Learning. COPD: Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2024;21.

- Atzeni M, Cappon G, Quint JK, Kelly F, Barratt B, Vettoretti M. A machine learning framework for short-term prediction of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations using personal air quality monitors and lifestyle data. Sci Rep. 2025;15:2385.

- Yin H, Wang K, Yang R, Tan Y, Li Q, Zhu W, et al. A machine learning model for predicting acute exacerbation of in-home chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2024;246:108005.

- Almazaydeh L, Elleithy K, Faezipour M. Obstructive sleep apnea detection using SVM-based classification of ECG signal features. 2012 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE; 2012. p. 4938–41.

- Espinoza-Cuadros F, Fernández-Pozo R, Toledano DT, Alcázar-Ramírez JD, López-Gonzalo E, Hernández-Gómez LA. Reviewing the connection between speech and obstructive sleep apnea. Biomed Eng Online. 2016;15:20.

- Hajipour F, Jozani MJ, Moussavi Z. A comparison of regularized logistic regression and random forest machine learning models for daytime diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2020;58:2517–29.

- Cheplygina V, Pena IP, Pedersen JH, Lynch DA, Sorensen L, de Bruijne M. Transfer Learning for Multicenter Classification of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2018;22:1486–96.

- Li Z, Liu L, Zhang Z, Yang X, Li X, Gao Y, et al. A Novel CT-Based Radiomics Features Analysis for Identification and Severity Staging of COPD. Acad Radiol. 2022;29:663–73.

- Amudala Puchakayala PR, Sthanam VL, Nakhmani A, Chaudhary MFA, Kizhakke Puliyakote A, Reinhardt JM, et al. Radiomics for Improved Detection of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Low-Dose and Standard-Dose Chest CT Scans. Radiology. 2023;307.

- Moslemi A, Kontogianni K, Brock J, Wood S, Herth F, Kirby M. Differentiating COPD and asthma using quantitative CT imaging and machine learning. European Respiratory Journal. 2022;60:2103078.

- Makimoto K, Hogg JC, Bourbeau J, Tan WC, Kirby M. CT Imaging With Machine Learning for Predicting Progression to COPD in Individuals at Risk. Chest. 2023;164:1139–49.

- Guan Y, Zhang D, Zhou X, Xia Y, Lu Y, Zheng X, et al. Comparison of deep-learning and radiomics-based machine-learning methods for the identification of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on low-dose computed tomography images. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2024;14:2485–98.

- Liao K-M, Liu C-F, Chen C-J, Shen Y-T. Machine Learning Approaches for Predicting Acute Respiratory Failure, Ventilator Dependence, and Mortality in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Diagnostics. 2021;11:2396.

- Moll M, Qiao D, Regan EA, Hunninghake GM, Make BJ, Tal-Singer R, et al. Machine Learning and Prediction of All-Cause Mortality in COPD. Chest. 2020;158:952–64.

- Zeng S, Arjomandi M, Tong Y, Liao ZC, Luo G. Developing a Machine Learning Model to Predict Severe Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Exacerbations: Retrospective Cohort Study. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24:e28953.

- Chen H, Emami E, Kauffmann C, Rompré P, Almeida F, Schmittbuhl M, et al. Airway Phenotypes and Nocturnal Wearing of Dentures in Elders with Sleep Apnea. J Dent Res. 2023;102:263–9.

- Abràmoff MD, Lavin PT, Birch M, Shah N, Folk JC. Pivotal trial of an autonomous AI-based diagnostic system for detection of diabetic retinopathy in primary care offices. NPJ Digit Med. 2018;1:39.

- Wu Y, Xia S, Liang Z, Chen R, Qi S. Artificial intelligence in COPD CT images: identification, staging, and quantitation. Respir Res. 2024;25:319.

- Quer G, Topol EJ. The potential for large language models to transform cardiovascular medicine. Lancet Digit Health. 2024;6:e767–71.

- Moor M, Banerjee O, Abad ZSH, Krumholz HM, Leskovec J, Topol EJ, et al. Foundation models for generalist medical artificial intelligence. Nature. 2023;616:259–65.

- Rasmy L, Xiang Y, Xie Z, Tao C, Zhi D. Med-BERT: pretrained contextualized embeddings on large-scale structured electronic health records for disease prediction. NPJ Digit Med. 2021;4:86.

- Yang S, Yang X, Lyu T, Huang JL, Chen A, He X, et al. Extracting Pulmonary Nodules and Nodule Characteristics from Radiology Reports of Lung Cancer Screening Patients Using Transformer Models. J Healthc Inform Res. 2024;8:463–77.

- Roy A, Gyanchandani B, Oza A, Singh A. TriSpectraKAN: a novel approach for COPD detection via lung sound analysis. Sci Rep. 2025;15:6296.

- Vodnala N, Yarlagadda PS, Bhuvana K S, Ch M, Sailaja K. Novel Deep Learning Approaches to Differentiate Asthma and COPD Based on Cough Sounds. 2024 Parul International Conference on Engineering and Technology (PICET). IEEE; 2024. p. 1–4.

- Bodduluri S, Nakhmani A, Reinhardt JM, Wilson CG, McDonald M-L, Rudraraju R, et al. Deep neural network analyses of spirometry for structural phenotyping of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JCI Insight. 2020;5.

- Mei S, Li X, Zhou Y, Xu J, Zhang Y, Wan Y, et al. Deep learning for detecting and early predicting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from spirogram time series. NPJ Syst Biol Appl. 2025;11:18.

- Gadgil S, Galanter J, Negahdar M. Transformer-based Time-Series Biomarker Discovery for COPD Diagnosis. 2024;

- Taghizadegan Y, Jafarnia Dabanloo N, Maghooli K, Sheikhani A. Prediction of obstructive sleep apnea using ensemble of recurrence plot convolutional neural networks (RPCNNs) from polysomnography signals. Med Hypotheses. 2021;154:110659.

- Niroshana SMI, Zhu X, Nakamura K, Chen W. A fused-image-based approach to detect obstructive sleep apnea using a single-lead ECG and a 2D convolutional neural network. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0250618.

- Mukherjee D, Dhar K, Schwenker F, Sarkar R. Ensemble of Deep Learning Models for Sleep Apnea Detection: An Experimental Study. Sensors. 2021;21:5425.

- Mashrur FR, Islam MdS, Saha DK, Islam SMR, Moni MA. SCNN: Scalogram-based convolutional neural network to detect obstructive sleep apnea using single-lead electrocardiogram signals. Comput Biol Med. 2021;134:104532.

- Wang T, Lu C, Shen G, Hong F. Sleep apnea detection from a single-lead ECG signal with automatic feature-extraction through a modified LeNet-5 convolutional neural network. PeerJ. 2019;7:e7731.

- Chang H-Y, Yeh C-Y, Lee C-T, Lin C-C. A Sleep Apnea Detection System Based on a One-Dimensional Deep Convolution Neural Network Model Using Single-Lead Electrocardiogram. Sensors. 2020;20:4157.

- Zhang Y, Zhou L, Zhu S, Zhou Y, Wang Z, Ma L, et al. Deep Learning for Obstructive Sleep Apnea Detection and Severity Assessment: A Multimodal Signals Fusion Multiscale Transformer Model. Nat Sci Sleep. 2025;Volume 17:1–15.

- Tang LYW, Coxson HO, Lam S, Leipsic J, Tam RC, Sin DD. Towards large-scale case-finding: training and validation of residual networks for detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease using low-dose CT. Lancet Digit Health. 2020;2:e259–67.

- Wu Y, Qi S, Feng J, Chang R, Pang H, Hou J, et al. Attention-guided multiple instance learning for COPD identification: To combine the intensity and morphology. Biocybern Biomed Eng. 2023;43:568–85.

- Xu C, Qi S, Feng J, Xia S, Kang Y, Yao Y, et al. DCT-MIL: Deep CNN transferred multiple instance learning for COPD identification using CT images. Phys Med Biol. 2020;65:145011.

- Yu K, Sun L, Chen J, Reynolds M, Chaudhary T, Batmanghelich K. DrasCLR: A self-supervised framework of learning disease-related and anatomy-specific representation for 3D lung CT images. Med Image Anal. 2024;92:103062.

- González G, Ash SY, Vegas-Sánchez-Ferrero G, Onieva Onieva J, Rahaghi FN, Ross JC, et al. Disease Staging and Prognosis in Smokers Using Deep Learning in Chest Computed Tomography. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:193–203.

- Zou X, Ren Y, Yang H, Zou M, Meng P, Zhang L, et al. Screening and staging of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with deep learning based on chest X-ray images and clinical parameters. BMC Pulm Med. 2024;24:153.

- Schroeder JD, Bigolin Lanfredi R, Li T, Chan J, Vachet C, Paine R, et al. Prediction of Obstructive Lung Disease from Chest Radiographs via Deep Learning Trained on Pulmonary Function Data. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2021;Volume 15:3455–66.

- Weiss J, Raghu VK, Bontempi D, Christiani DC, Mak RH, Lu MT, et al. Deep learning to estimate lung disease mortality from chest radiographs. Nat Commun. 2023;14:2797.

- Ryu S, Kim JH, Yu H, Jung H-D, Chang SW, Park JJ, et al. Diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea with prediction of flow characteristics according to airway morphology automatically extracted from medical images: Computational fluid dynamics and artificial intelligence approach. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2021;208:106243.

- Tsuiki S, Nagaoka T, Fukuda T, Sakamoto Y, Almeida FR, Nakayama H, et al. Machine learning for image-based detection of patients with obstructive sleep apnea: an exploratory study. Sleep and Breathing. 2021;25:2297–305.

- Luo J, Ye M, Xiao C, Ma F. HiTANet: Hierarchical Time-Aware Attention Networks for Risk Prediction on Electronic Health Records. Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2020. p. 647–56.

- Lopez K, Li H, Lipkin-Moore Z, Kay S, Rajeevan H, Davis JL, et al. Deep learning prediction of hospital readmissions for asthma and COPD. Respir Res. 2023;24:311.

- Radford A, Kim JW, Hallacy C, Ramesh A, Goh G, Agarwal S, et al. Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision. 2021;

- Lee J, Yoon W, Kim S, Kim D, Kim S, So CH, et al. BioBERT: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics. 2020;36:1234–40.

- Zhang Y, Xia T, Han J, Wu Y, Rizos G, Liu Y, et al. Towards Open Respiratory Acoustic Foundation Models: Pretraining and Benchmarking. 2024;

- Eyben F, Wöllmer M, Schuller B. Opensmile. Proceedings of the 18th ACM international conference on Multimedia. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2010. p. 1459–62.

- Hershey S, Chaudhuri S, Ellis DPW, Gemmeke JF, Jansen A, Moore RC, et al. CNN architectures for large-scale audio classification. 2017 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE; 2017. p. 131–5.

- Po-Yao Huang, Hu Xu, Juncheng Li, Alexei Baevski, Michael Auli, Wojciech Galuba, et al. Masked Autoencoders that Listen. NeurIPS Proceedings. 2022;

- Elizalde B, Deshmukh S, Ismail M Al, Wang H. CLAP Learning Audio Concepts from Natural Language Supervision. ICASSP 2023 - 2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE; 2023. p. 1–5.

- Niu C, Lyu Q, Carothers CD, Kaviani P, Tan J, Yan P, et al. Medical multimodal multitask foundation model for lung cancer screening. Nat Commun. 2025;16:1523.

- Mikhael PG, Wohlwend J, Yala A, Karstens L, Xiang J, Takigami AK, et al. Sybil: A Validated Deep Learning Model to Predict Future Lung Cancer Risk From a Single Low-Dose Chest Computed Tomography. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2023;41:2191–200.

- Chao H, Shan H, Homayounieh F, Singh R, Khera RD, Guo H, et al. Deep learning predicts cardiovascular disease risks from lung cancer screening low dose computed tomography. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2963.

- Li Y, Rao S, Solares JRA, Hassaine A, Ramakrishnan R, Canoy D, et al. BEHRT: Transformer for Electronic Health Records. Sci Rep. 2020;10:7155.

- Herrett E, Gallagher AM, Bhaskaran K, Forbes H, Mathur R, van Staa T, et al. Data Resource Profile: Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD). Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:827–36.

- Miotto R, Li L, Kidd BA, Dudley JT. Deep Patient: An Unsupervised Representation to Predict the Future of Patients from the Electronic Health Records. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26094.

- Choi E, Bahadori MT, Kulas JA, Schuetz A, Stewart WF, Sun J. RETAIN: An Interpretable Predictive Model for Healthcare using Reverse Time Attention Mechanism. 2016;

- Regan EA, Hokanson JE, Murphy JR, Make B, Lynch DA, Beaty TH, et al. Genetic Epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) Study Design. COPD: Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2011;7:32–43.

- Vestbo J, Anderson W, Coxson HO, Crim C, Dawber F, Edwards L, et al. Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate End-points (ECLIPSE). European Respiratory Journal. 2008;31:869–73.

- Couper D, LaVange LM, Han M, Barr RG, Bleecker E, Hoffman EA, et al. Design of the Subpopulations and Intermediate Outcomes in COPD Study (SPIROMICS): Table 1. Thorax. 2014;69:492–5.

- Bourbeau J, Tan WC, Benedetti A, Aaron SD, Chapman KR, Coxson HO, et al. Canadian Cohort Obstructive Lung Disease (CanCOLD): Fulfilling the Need for Longitudinal Observational Studies in COPD. COPD: Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2014;11:125–32.

- Johnson AEW, Pollard TJ, Shen L, Lehman LH, Feng M, Ghassemi M, et al. MIMIC-III, a freely accessible critical care database. Sci Data. 2016;3:160035.

- Johnson AEW, Bulgarelli L, Shen L, Gayles A, Shammout A, Horng S, et al. Author Correction: MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci Data. 2023;10:219.

- Pollard TJ, Johnson AEW, Raffa JD, Celi LA, Mark RG, Badawi O. The eICU Collaborative Research Database, a freely available multi-center database for critical care research. Sci Data. 2018;5:180178.

- Faltys M, Zimmermann M, Lyu X, Hüser M, Hyland S, Rätsch G, et al. HiRID, a high time-resolution ICU dataset. PhysioNet. 2021;

- Wu Z, Jiang Y, Li S, Li A. Enhanced machine learning predictive modeling for delirium in elderly ICU patients with COPD and respiratory failure: A retrospective study based on MIMIC-IV. PLoS One. 2025;20:e0319297.

- Penzel T, Moody GB, Mark RG, Goldberger AL, Peter JH. The apnea-ECG database. Computers in Cardiology 2000 Vol27 (Cat 00CH37163). IEEE; 2002. p. 255–8.

- Goldberger A, Amaral L, Glass L, Hausdorff J, Ivanov PC, Mark R, et al. St. Vincent’s University Hospital / University College Dublin Sleep Apnea Database. PhysioNet. 2007.

- Quan SF, Howard B V, Iber C, Kiley JP, Nieto FJ, O’Connor GT, et al. The Sleep Heart Health Study: design, rationale, and methods. Sleep. 1997;20:1077–85.

- Topol EJ. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat Med. 2019;25:44–56.

- Hatem R, Simmons B, Thornton JE. A Call to Address AI “Hallucinations” and How Healthcare Professionals Can Mitigate Their Risks. Cureus. 2023;

- Science & Tech Spotlight: Generative AI in Health Care. U.S. Government Accountability Office. 2024.

- AI Act. European Commision. 2025.

- Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence and amending Regulations (EC) No 300/2008, (EU) No 167/2013, (EU) No 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, (EU) 2018/1139 and (EU) 2019/2144 and Directives 2014/90/EU, (EU) 2016/797 and (EU) 2020/1828 (Artificial Intelligence Act) (Text with EEA relevance). European Union; 2024.

- DeGroot MH. Optimal Statistical Decisions. Wiley; 2004.

- Kevin P. Murphy. Probabilistic Machine Learning: An introduction. MIT Press; 2022.

- Dawid AP. The Well-Calibrated Bayesian. J Am Stat Assoc. 1982;77:605–10.

- Luciana Ferrer, Daniel Ramos. Evaluating Posterior Probabilities: Decision Theory, Proper Scoring Rules, and Calibration. Transactions on Machine Learning Research. 2025;

- Guo C, Pleiss G, Sun Y, Weinberger KQ. On calibration of modern neural networks. Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning. JMLR.org; 2017. p. 1321–30.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).