1. Introduction

Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have become the dominant energy storage technology for various applications, ranging from consumer electronics to grid storage and electric vehicles, also in the working vehicle industry [

1,

2]. Accurate modeling of LIBs is essential for predicting performance, optimizing efficiency, and ensuring safe operation. Battery models can be broadly categorized into empirical, equivalent circuit models (ECMs) [

3] and physics-based models. The latter offer a more comprehensive representation of the multiphysics processes occurring in batteries; however, this increased accuracy comes at the cost of higher computational complexity due to the coupling of Partial Differential Equations (PDEs). Among physics-based models, the Doyle-Fuller-Newman (DFN) model [

4] stands out as the most prominent due to its ability to accurately describe lithium-ion transport, charge transfer, and electrochemical reactions within the battery. It serves as a fundamental reference for advanced battery simulations and optimization studies, making it a cornerstone in battery modeling research. However, this requires precise estimation of electrochemical and mechanical parameters, which influence battery behavior under operating conditions.

When it comes to battery modeling, it is important to distinguish between the manufacturer perspective and the end user or system integrator one. Manufacturers typically have access to comprehensive internal data, including detailed material properties, geometric specifications, and electrochemical parameters obtained through dedicated design, optimization and characterization campaigns. In contrast, end users – such as developers of battery management systems or integrators of battery packs – often have limited access to such internal information. Therefore, parameter identification plays a crucial role in battery modeling, ensuring that simulation results aligned with actual behavior. Some parameters can be directly measured using experimental setups, while others are more challenging or expensive to determine, requiring estimation methods.

Many studies performed battery parameter estimation through voltage curve fitting [

5,

6], where experimental discharge and charge curves are matched to the simulated ones. This method is widely used due to its simplicity and effectiveness in capturing electrochemical characteristics. The drawback is the reduced accuracy when dealing with a large number of parameters that are not strictly sensitive to voltage profile – called "voltage-insensitive" after a dedicated sensitivity analysis [

7]. Other works leverage on multi-objective approach in order to capture a larger number of sensitive parameters. COBRAPRO [

8] is a MATLAB-based open-source toolbox with an integrated parameter estimation routine for physics-based battery models. It minimizes a multi-objective cost function considering the voltage profile and SOC depending on the concentration of lithium-ions in the electrodes. PyBOP [

9] is a Python library designed to work with PyBaMM, offering a flexible framework for parameter estimation. It uses both gradient-based and free derivative optimization methods to fit model parameters to experimental data, supporting custom objective functions. Zhang et al. [

10] propose a coupled electro-thermal model using Genetic Algorithms (GAs) and minimizing the multi-objective function through Pareto fronts.

Recently, significant focus has been placed on the mechanical response of LIBs during operation, leading to the development of various techniques to measure and model the battery deformation induced by the electrochemical processes [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15] . However, existing parameter estimation methods largely overlook this mechanical behavior. In this work, the effect of the mechanical measurements of the battery deformation on parameter estimation is deeply investigated through an optimization model developed in COMSOL Multiphysics. Particularly focusing on LFP/graphite batteries, a comparison between the electrochemical and the electro-chemo-mechanical approach is then presented to highlight the differences.

2. Materials and Methods

Optimization is an engineering challenge based on identifying the set of parameters

that minimize an objective function

while ensuring the constraints of the physical phenomenon (

and

). Each parameter

can vary in a range defined between a lower bound

and an upper bound

in accordance to the parameters constraints. Therefore, an optimization problem is generally expressed with the mathematical formulation shown in Equation (

1).

The aim of this work is the introduction of a novel battery parameter estimation approach based on a multi-objective function that also integrates the mechanical deformation of the battery during its operating conditions. To achieve this goal, it is necessary to develop an appropriate model that accurately describes the battery behavior and to properly asses the optimization problem defining objective functions, parameters and constraints as deeply described in this work. The optimization is performed using the BOBYQA algorithm [

16], which is especially useful when the first derivative of the objective function is not available and each simulation is computationally expensive, requiring an efficient optimization strategy. A more detailed overview of the electro-chemo-mechanical model and the optimization algorithm is provided in the following sections.

2.1. Doyle-Fuller-Newman Model

The DFN model provides a physics-based framework that captures the coupled electrical and chemical species transport phenomena that occur within the battery. Based on the porous electrode and concentrated solution theories, the model accounts for key processes such as lithium-ion diffusion in the solid and electrolyte phases and charge transfer kinetics at the electrode-electrolyte interface. It also captures the multiscale behavior arising from lithium diffusion within the active material particles. The DFN model is also referred to as the Pseudo-Two-Dimensional (P2D) model. This name arises from its formulation: it resolves a one-dimensional spatial domain along the electrode thickness, and at each position within this domain, it incorporates a second dimension representing lithium diffusion within spherical particles. The P2D governing equations and the corresponding boundary conditions are listed in

Table 1.

The superscript

eff refers to the correction applied to the diffusion coefficients, conductivities, and reaction rates, accounting for porosity and tortuosity in each domain [

17], as well as thermal dependence when the temperature differs from the reference value [

18].

2.2. Mechanical Deformation

The electrodes of lithium-ion batteries are composed of porous composite structures that include active material particles, conductive additives, and a polymeric binder. The active material serves as a host for lithium ions, which are reversibly inserted and extracted during charge and discharge. These processes are called intercalation and deintercalation, respectively. As lithium ions intercalate into or deintercalate from the host structure, they cause lattice configuration changes, leading to microscopic volume expansion or contraction.

The lattice structure strain can be characterized through XRD techniques by measuring the variation of the lattice parameters as a function of the corresponding state of lithiation of the electrode. The state of lithiation is the ratio between the actual and the maximum amount of lithium concentration that can be hosted from the active material (

y is the cathode state of lithiation while

x is the anode one as reported in Equation (

2)).

The maximum lithium concentration depends on the lithiated active material crystal’s density

and molar mass

as shown in Equation (

3) [

19].

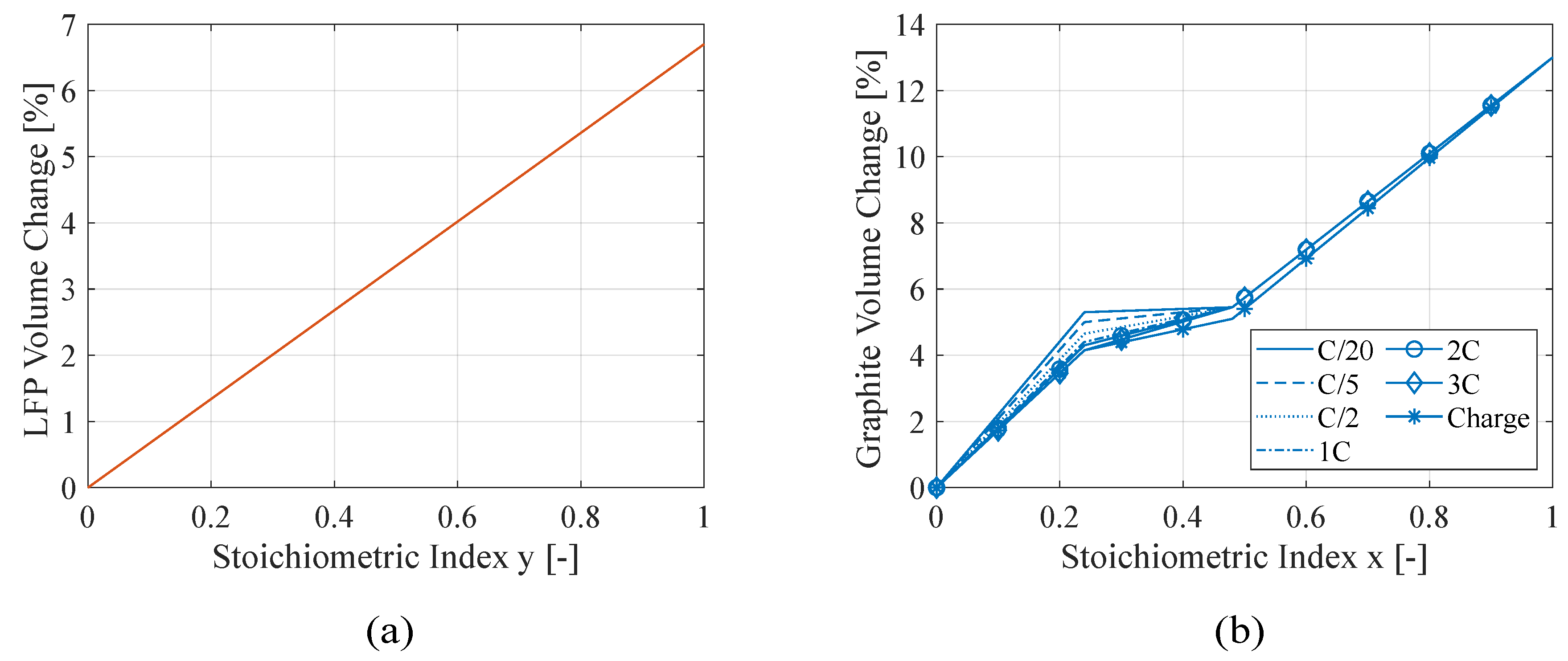

During lithiation, active materials exhibit phase transitions from their delithiated configuration to the fully lithiated one. LFP undergoes through a single phase transition from

to

. Instead, graphite (

) manifests multiple phase transitions before reaching its fully lithiated stage

[

11,

20]. In addition, graphite stage transition is not symmetric during its lithiation-delithiation cycle. This is mainly due to the presence of the stage IIL during lithium extraction. In fact, this stage is only present at low discharge current rates and gradually fades increasing the discharge current. Therefore, there is a lithiation window where stages II, IIL and III coexist; lower discharge rates increase the stage IIL volume fraction and smooth the volume change from stage II to III, due to the lower density of stage IIL. From the XRD measurement on LFP [

21] and graphite [

20,

22], the crystal volume change as function of the state of lithiation are shown in

Figure 1.

The lattice parameters exhibit directional dependence in their deformation due to the intrinsic anisotropy of the lattice structure. Although, this anisotropic nature is mitigated by the random orientation of the crystals within the particle. Thus, considering the volumetric strain, the active material particle deforms consistently with its crystal lattice.

Then, at the upper scale the electrode volume change

depends on the

particles volumetric deformation

and on a possible reduction in porosity accounted through a volumetric expansion parameter

g [

23] as shown in Equation (

4). In addition, the volume of the

particles constitute the overall active material volume leading to Equation (

5).

Therefore, the volumetric strain of the electrode is obtained dividing the Equation (

4) by the initial volume of the single particle

and accounting for Equation (

5) as reported in Equation (

6). Since the battery is assumed to be free to expand, the reduction in porosity is considered negligible adopting the assumption of

[

11].

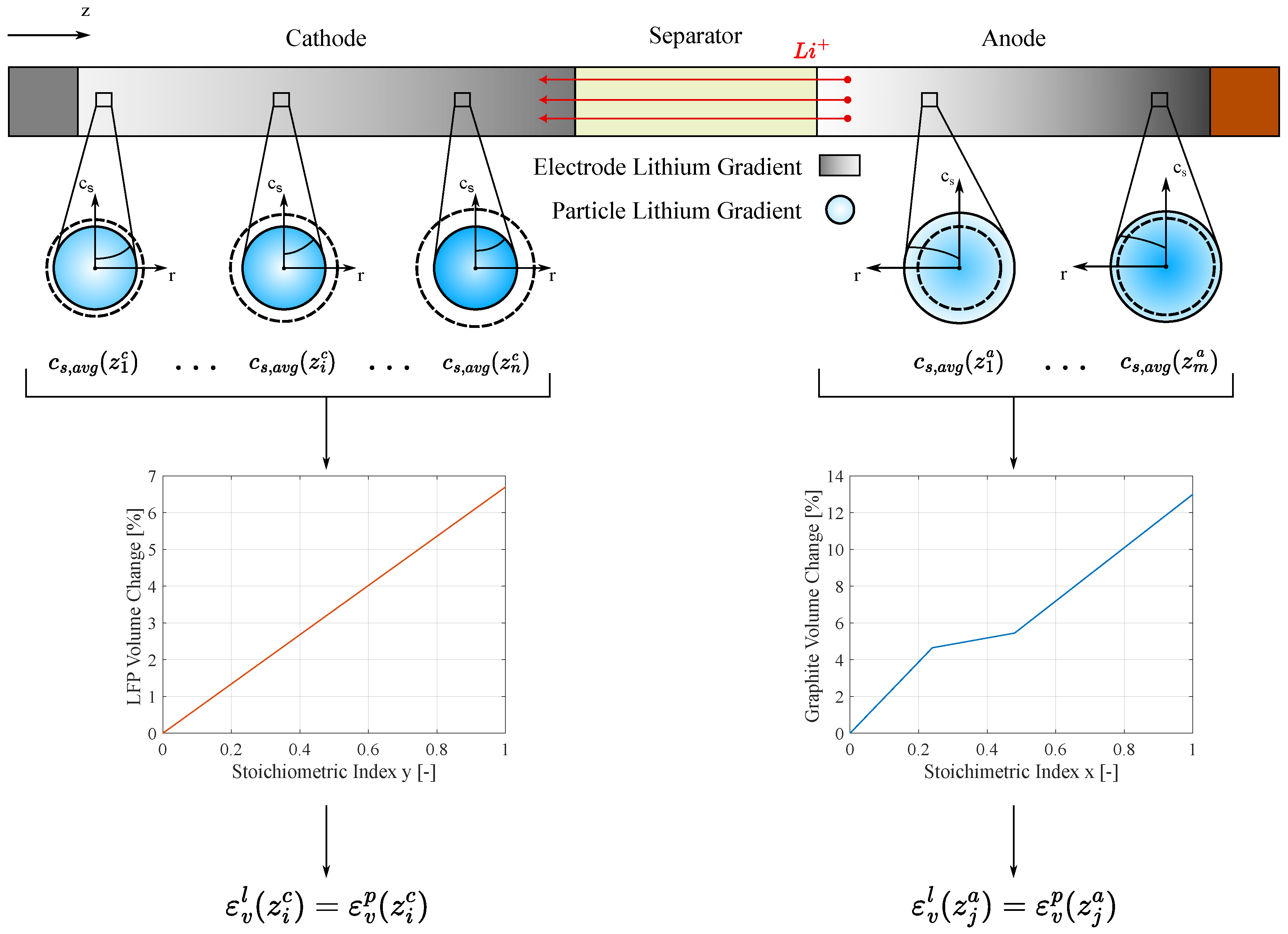

The previous equations hold under the assumption that all

particles deform uniformly. However, this is not entirely accurate due to lithium diffusion along the electrode thickness. In reality, during battery operation, the lithiated electrode has more lithium content near the separator while the delithiated one has higher lithium concentration near the current collector. In fact, the lithium-ions diffusion is less constrained in the separator area (

Figure 2).

Equation (

6) remains valid if

represents the average deformation of the particles across the electrode thickness. To achieve this, the P2D model is used to extract the lithium concentration

at different positions along this direction. The concentration is then averaged over the particle radius (

) to determine the crystal lattice strain of the material, thus the particle strain

as shown in

Figure 2. Finally, the particle strain is averaged across the electrode thickness to obtain the overall mean particle deformation

.

The volumetric strain propagates across the battery scales, resulting in a macroscopic thickness change that is evaluated accounting for the deformation of both the electrodes and the presence of

N layers [

24,

25]. Due to the small thickness of the electrode with respect to the in-plane geometry, the volumetric strain of the electrode is assumed to be responsible just of the out-of-plane strain (

) [

11] resulting in the overall battery thickness change modeled as presented in Equation (

7).

2.3. Objective Function

Once the electro-chemo-mechanical behavior of the battery is modeled, the objective function for the parameter estimation can be set. Least-Square Objective Function () has been used to measure and minimize the difference between observed data points and the model’s predicted values. This approach is very useful for curve fitting since it evaluates the sum of squared errors, computed over all data points, preventing positive and negative errors from canceling out and ensuring that larger deviations are penalized more heavily, improving convergence.

In a time-dependent curve fitting, considering

the variable at the i-th time step, the

is computed as presented in Equation (

8).

A multi-objective function approach is needed to evaluate the integration of the battery deformation in parameters estimation. Therefore, two LSOFs need to be computed in order to account both the electrochemical measurements of the voltage profile and the mechanical measurements of the battery deformation.

Due to the different scales of the electrochemical objective function

and the mechanical one

, Equations (

9) and (

10) have been normalized with respect to the square of the minimum voltage and maximum deformation – measured at the end of the test – respectively. Additionally, also the battery capacity

C is controlled with the same quadratic approach obtaining the objective functions reported in Equations (

11)–(

13) which constitute the multi-objective problem statement presented in Equation (

14) as a vector of objective functions.

Depending on the same set of parameters

coming from the same multiphysics modeling, the objective functions cannot be minimized at the same time and independently. Therefore, the multi-objective problem is solved using a scalarization approach to reduce computational complexity and enable variations in the weighting of the objective functions with respect to the Pareto technique [

26,

27]. Thus, a single objective function is obtained in Equations (

15) and (

16) where

is the weights vector of the objective functions. Weighting factors are eventually applied to prioritize certain objective functions over others. During the electrochemical-only parameter estimation

to ignore the mechanical objective function.

2.4. Optimization Algorithm

Since the optimization problem involves multiple objectives, the derivative of with respect to the control variables is not easily obtainable: the presence of several objectives complicates the calculation of a unique and continuous gradient, making gradient-based algorithms unsuitable. In addition, changes in geometry often lead to remeshing, which may introduce discontinuities or non-differentiable behavior in the objective function. As a result, the computed gradients may be inaccurate or undefined. Therefore, a derivative-free algorithm is more appropriate for addressing this type of problem. The drawback is the slower convergence of the optimization process.

Among the derivative-free algorithm implemented in COMSOL Multiphysics, BOBYQA (Bound Optimization BY Quadratic Approximation) is the only one that uses a quadrative interpolation model to approximate the objective function. Unlike gradient-based methods, BOBYQA constructs and updates a local quadratic model

using only objective function evaluations. In particular, the quadratic model is built to interpolate the objective function at a set of

m points

, with

as shown in Equation (

17). The interpolation points

are strategically chosen and updated as stated by Powell in his work [

16].

Then, the quadratic approximation of the objective function has the form presented in Equation (

18) where

c is a scalar constant,

g is the estimated gradient,

H is an approximated Hessian matrix and

is the evaluation point at the k-th iteration.

To determine the next point to evaluate, BOBYQA minimizes the quadratic model

within a neighborhood of the current point

, known as the

trust region. This area is defined by a radius

, which bounds the maximum allowed step from the current iteration. The trust-region subproblem is expressed in Equation (

19).

After evaluating the objective function at the new candidate point, the radius is updated depending on the agreement between the predicted decrease in and the actual decrease in . If the model prediction is sufficiently accurate, is expanded to allow broader exploration; otherwise, it is reduced to focus on a more local region, enhancing model reliability but risking to miss the global minimum.

In parallel, the quadratic model itself is updated to maintain interpolation accuracy: whenever a new function evaluation is accepted and one of the existing interpolation points is replaced, the curvature of the model – represented by the Hessian approximation H – must also be updated. This update ensures that the new model still satisfies the interpolation conditions at the updated set of points.

2.5. Error Analysis and Models Comparison

Once the parameters are estimated using the least squares method, the Root Mean Square Errors (RMSEs) of the fitted curves is computed and the reliability of the parameters estimates is evaluated using the covariance matrix. For

n parameters

, the covariance matrix

C is expressed as shown in Equation (

20).

The diagonal elements represent the variances of the individual parameter estimates, indicating the variability in each estimation. The off-diagonal elements represent the covariance between pairs of parameters, reflecting their linear relationship.

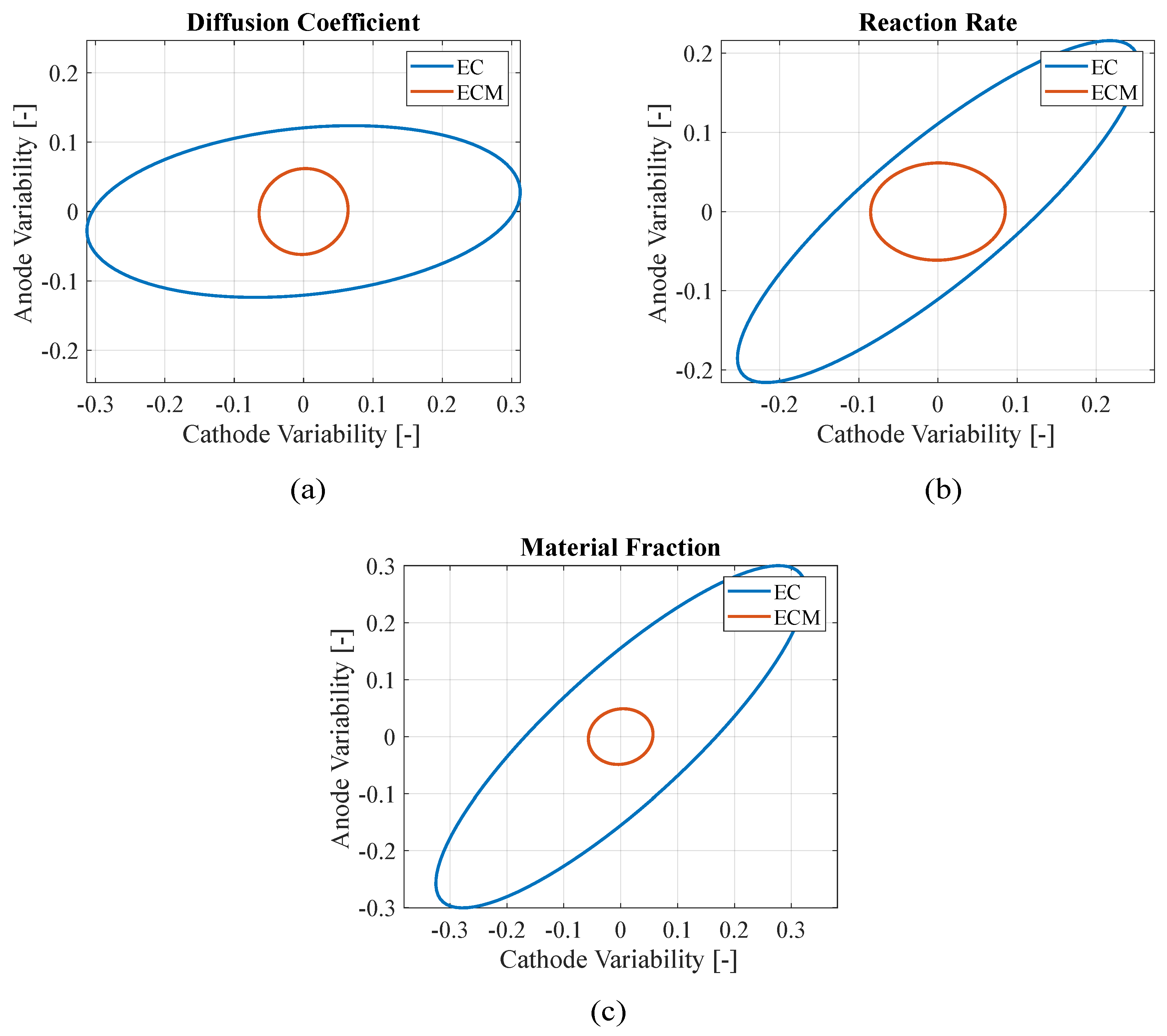

In this model, during the optimization process, each iteration produces a set of parameters that typically improves or maintains the objective function value. These intermediate estimates can be interpreted as a set of plausible solutions within the parameter space. By treating them as empirical samples, it is possible to compute a covariance matrix that captures the spread and correlation of the parameters across iterations. The empirical covariance matrix can then be used to construct confidence (or error) ellipses for selected pairs of parameters. These ellipses are derived from the submatrices of the covariance matrix , which are symmetric and positive definite. The rescaling of the parameters is needed because of the difference in order of magnitude and units of measures of the estimated parameters.

The orientation of the ellipse is determined by the covariance between the two parameters. Specifically, the orientation of the ellipse can be described by an angle , measured with respect to the x-axis: the closer is to °, the stronger the correlation between the parameters, while ° or ° indicates no correlation. On the other hand, larger ellipse indicates higher variances in the estimated parameters across iterations, suggesting that the algorithm has explored a broader region of the parameter space. While this may reflect a more thorough search of the objective function landscape, it can also be a sign of reduced convergence toward stable parameter values. For this reason, the confidence ellipses – which provide a qualitative representation of the parameter uncertainty and correlation given by the optimization model – should be considered together with the RMSE values to enable a more comprehensive comparison between the electrochemical and the electro-chemo-mechanical approach.

3. Experiment

Three commercial LFP/graphite prismatic LIB samples undergo electrical, thermal, and mechanical characterization to evaluate their performance. The tests consist of measuring voltage, temperature, and deformation responses under different charge and discharge currents. Charge rates vary from C/20 to C/2, while discharge rates range from C/20 to 3C, in accordance with manufacturer specifications. Each charge/discharge test is conducted within a state of charge (SOC) range of 0%–100% and repeated five times on the same battery sample. A dedicated testing setup with laser sensors is used to monitor battery deformation during operation by measuring thickness variations, as reported in a previous study by the authors [

28]. The measured voltage and thickness change, averaged over the tested samples, constitute the dataset used for parameter estimation through the optimization algorithm.

4. Results

4.1. Parameters and Constraints

Certain battery parameters can be measured or evaluated experimentally with relatively simple tests and can therefore be considered known or fixed during the estimation procedure, which helps to reduce the complexity of the simulation. In contrast, some electrochemical parameters – such as diffusion coefficients and reaction rates – require more advanced and complex experimental procedures for accurate identification, and their values reported in the literature often span a wide range. Other physical parameters, such as electrode thickness and the number of electrode layers, can only be determined after battery teardown.

Therefore, alongside the comparison between electrochemical and electro-chemo-mechanical parameter estimation, two distinct scenarios are analyzed:

Battery Teardown – the battery has been disassembled and parameters such as electrode thickness and the number of layers are known. In this case, the set of parameters to be estimated comprises the diffusion coefficients, the reaction rates and the active material fractions of the two electrodes as shown in Equation (

21)

-

No Battery Teardown – the battery has not been disassembled and also the thickness of the electrodes and the number of layers are unknown. The extended set of parameters is presented in Equation (

22).

In this case, it is necessary to constrain the overall battery thickness computed by the model

– accounting also for the separator thickness

and the current collectors ones

and

(Equation (

23)) – to remain within a specified tolerance range around the experimental value

as shown in Equation (

24).

Then, the parameters sets

and

are estimated by fitting experimental curves obtained from constant current cycles with 100% depth of discharge (DOD) at

current rate. In both scenarios, the stoichiometric windows are calculated with differential voltage analysis (DVA) at low current rates. The stoichiometric indexes corresponding to

(

and

) are imposed as fixed initial values during discharge while

and

are constrained around their corresponding experimental value with a certain tolerance (

and

respectively) as shown in Equation (

25).

However, the estimation cannot be considered complete: the diffusion coefficients are current-dependent [

18] and the contact resistance

– which is another challenging parameter to assess – is voltage-insensitive at low current rates, namely its value does not influence the voltage when the current is low. Therefore, the experimental data at

discharge current rate are then used to assess

and extrapolate the diffusion coefficient behavior

by linearly fitting the estimated

and

.

Among the other parameters – considered fixed in the optimization process – there are material properties like the molar mass

and the crystal density

of the active materials lattice structure, the corresponding maximum lithium concentration that can be obtained as stated in Equation (

3), electrolyte properties, solid-phase conductivity and the active material particle radius. Electrolyte parameters have low influence on the results, thus are taken from literature. The influence of the active material particle radius on the results is correlated with the diffusion coefficient, making trivial the estimation of both parameters. The fixed parameters are reported in

Table 2.

4.2. Teardown Configuration

In this configuration, the electrode thickness and the number of layers are known through SEM analysis conducted after battery teardown as shown in an authors previous work [

11]. The estimation procedure need initial guess values as starting point for the parameters to be estimated. The initial values of the diffusion coefficients and reaction rates are chosen from common values reported in literature while their lower bound is one order of magnitude lower and their upper bound is one order of magnitude higher. On the other hand, the initial value of the active material fraction is evaluated from the electrode capacity at low discharge rates – in which the stoichiometric window is known – from the relation expressed in Equation (

26). The parameters ranges and their final estimated values with the electrochemical (EC) and the electro-chemo-mechanical (ECM) approaches are reported in

Table 3.

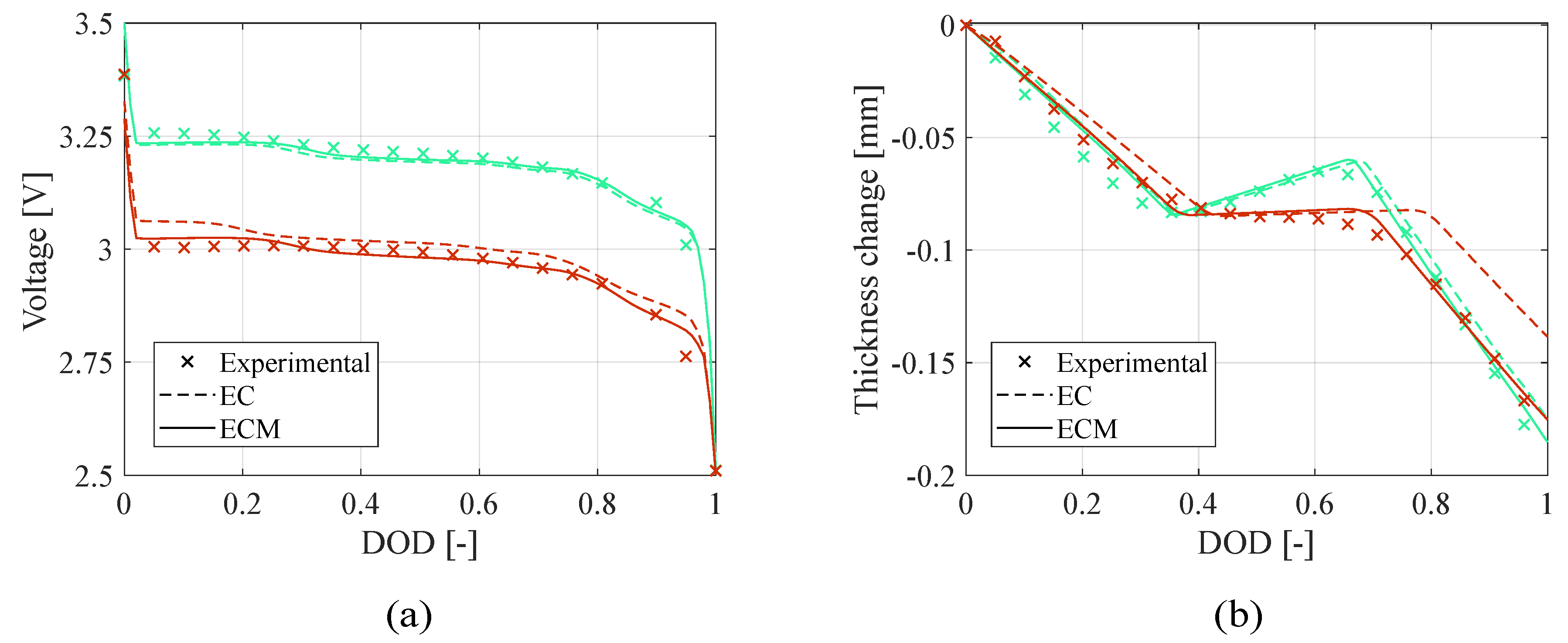

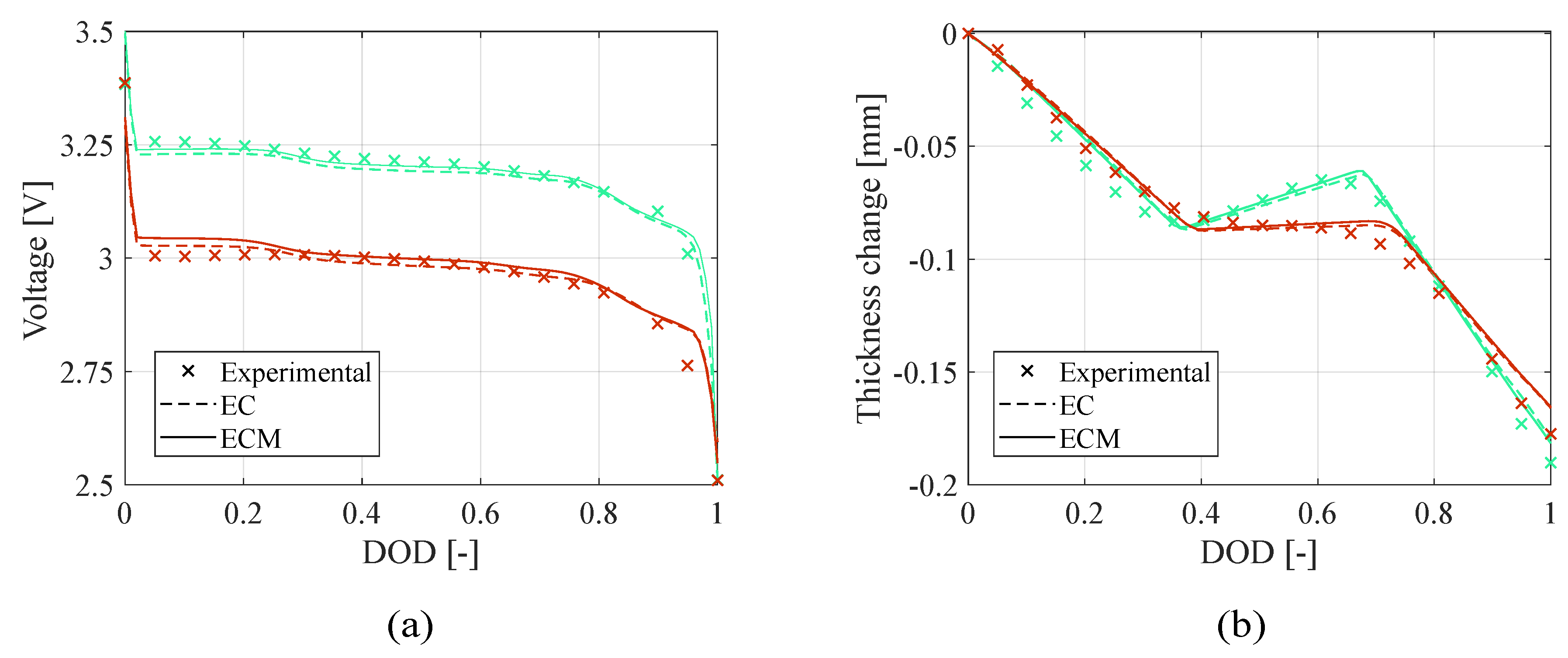

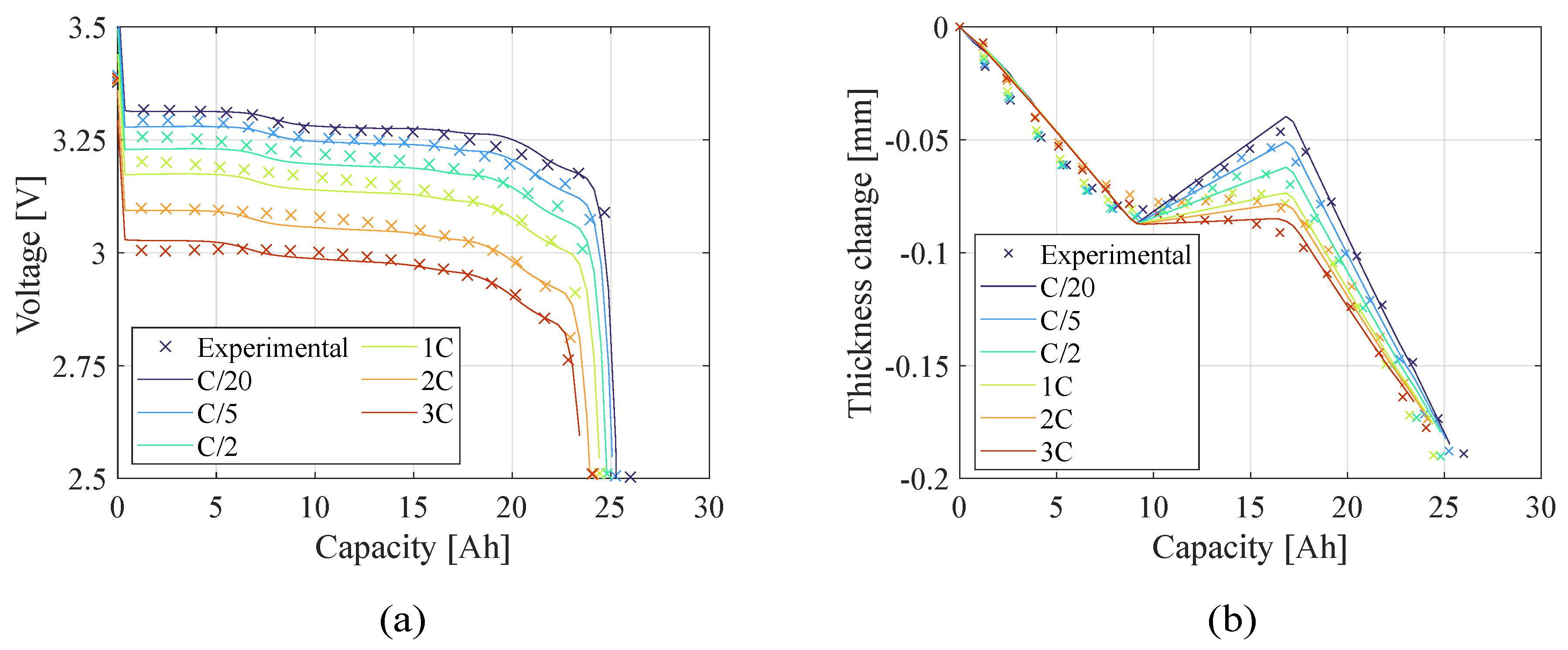

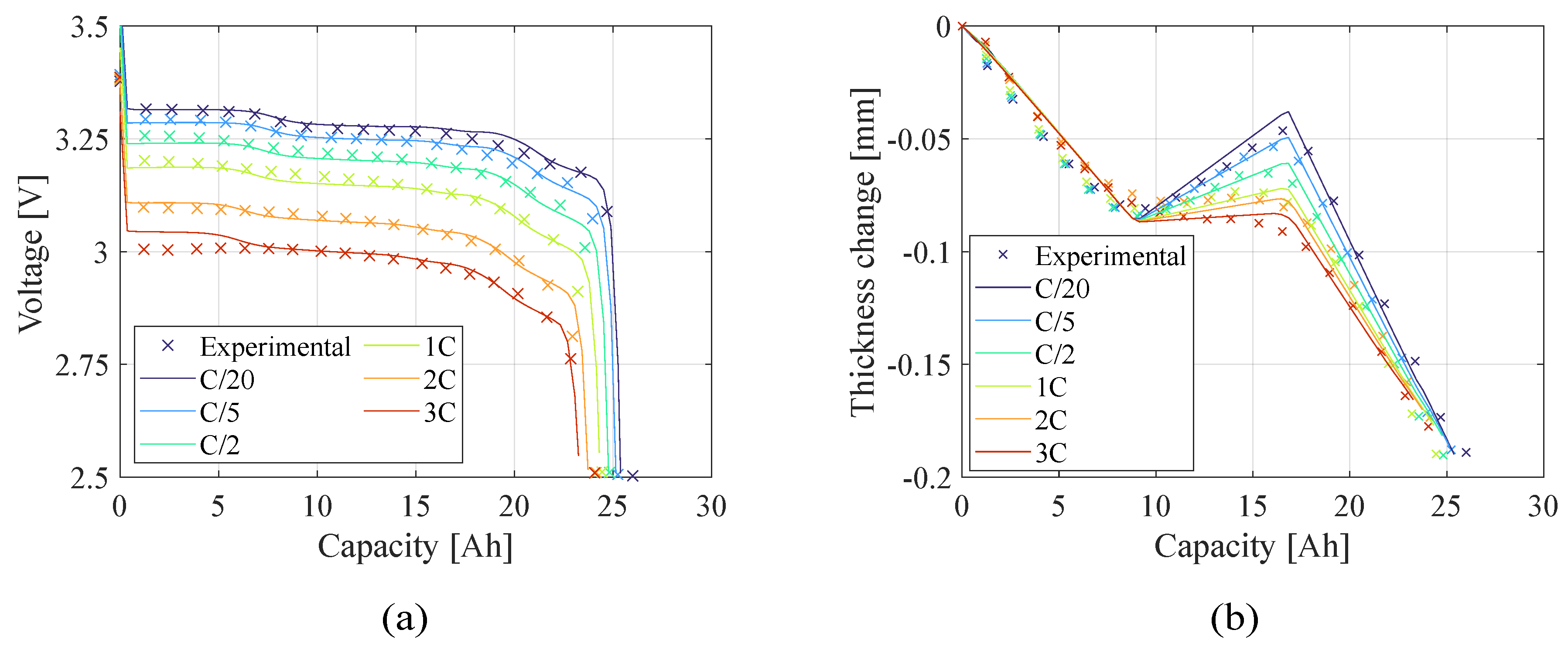

Figure 3 shows the voltage profile and the thickness change obtained at the end of the optimization process with the two estimation approaches in teardown scenario. Furthermore, in

Table 4 are reported the corresponding Root Mean Square Errors (RMSEs) as sum of the RMSEs computed at

and at

: the electro-chemo-mechanical (ECM) approach leads to more accurate prediction of the battery behavior presenting significantly lower errors; in fact, the electrochemical (EC) approach converges faster due to the simplicity of the objective function but leads to less accurate estimate. In addition,

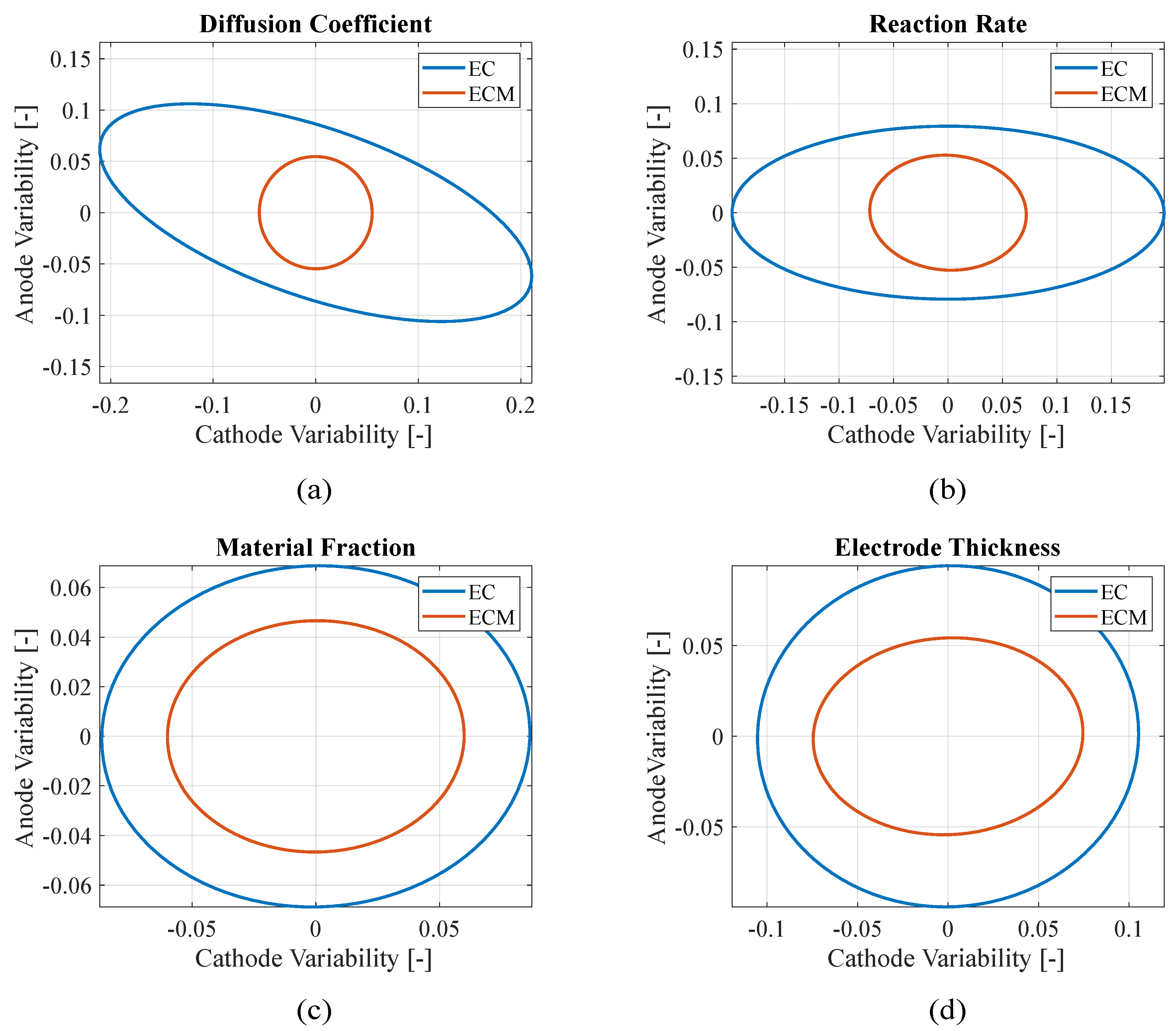

Figure 4 presents the confidence ellipses of paired parameters to compare the stability of the two approaches: adding the mechanical constraints makes the algorithm more reliable reducing the parameters variability with respect to using just electrochemical objective functions. In fact, smaller ellipses indicate that the parameters present lower variances through the iterations, which is a sign of improved convergence toward the final value. However, small ellipses may also result from the algorithm converging rapidly to a local minimum of the objective function without exploring a wide range of the possible parameters. For this reason, the confidence ellipses should be interpreted alongside the RMSEs to better assess the overall quality and reliability of the model. In this case, the electrochemical-only approach lead both to higher RMSEs and larger ellipses with respect to the electrochemical-mechanical approach, making the parameters identification with the latter approach more reliable.

4.3. No Teardown Configuration

In this configuration, even the electrode thickness and the number of layers must be estimated. While this increases the computational complexity, it also enables the estimation of such parameters without the need of the battery teardown. To assess the robustness of the model, the initial values for the electrode thickness are deliberately set slightly different from the measured ones. However, as shown in

Table 5, the end values of these parameters are strictly close to the one imposed in the teardown condition.

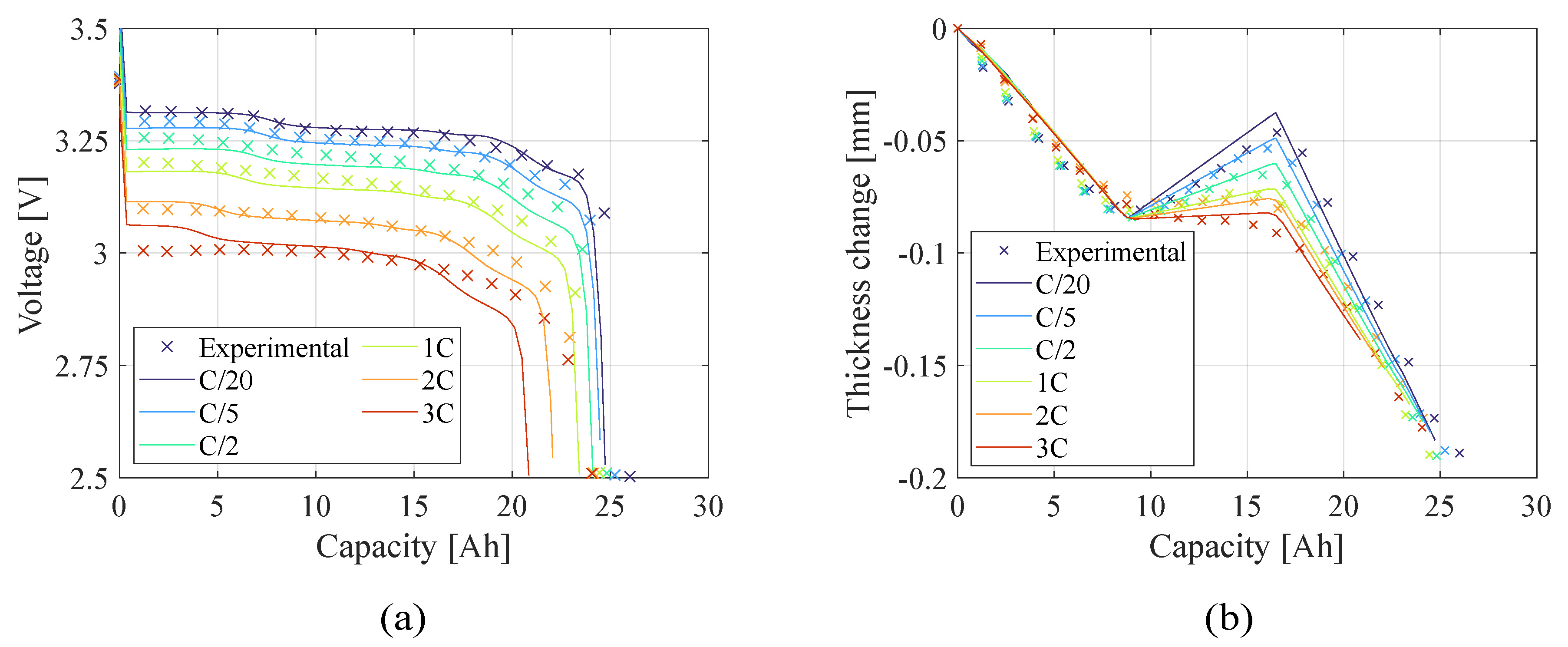

Figure 5 shows the voltage profile and the thickness change obtained at the end of the optimization process while

Table 6 reports the corresponding RMSEs in the configuration without battery teardown. In this scenario, the difference between the two model is negligible both in the estimation and therefore in the committed error: adding new capacity-sensitive parameters to be estimated avoids the wrong convergence reached in the previous scenario. However, in this case, the main difference between the two models stands in their capability of generating reliable solutions. In fact, even in this scenario, the electro-chemo-mechanical approach is able to increase the reliability of the estimation as presented in

Figure 6 comparing the area of the error ellipses between the two models.

4.4. Validation

The obtained parameters are then used to validate the reliability of the estimation computing the model at different discharge current rates and comparing the results with the experimental values.

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 present the teardown scenario with the electrochemical and electro-chemo-mechanical estimated parameters, respectively. In the teardown scenario, as shown in

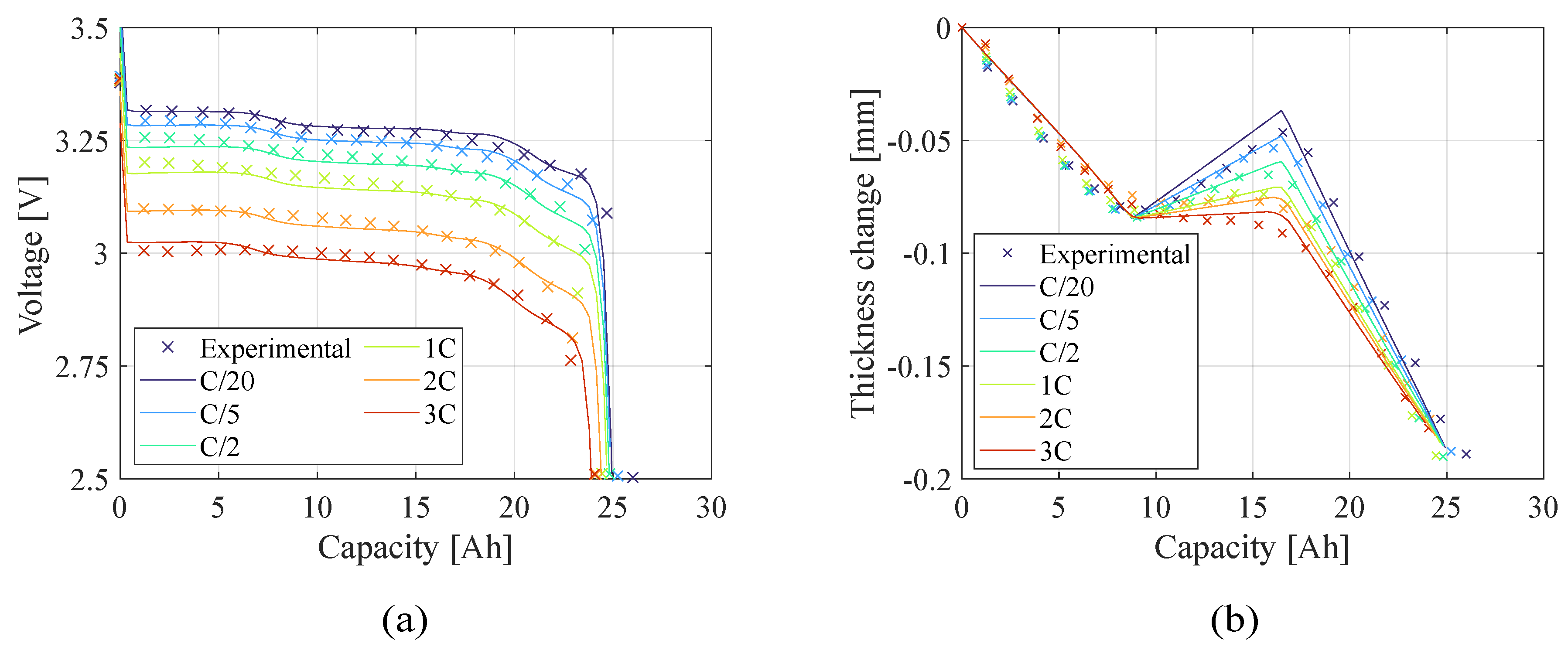

Section 4.2, the electrochemical-only approach converged to less accurate parameters resulting in a less accurate prediction of the battery behavior at different current rates. Conversely, with the same initial conditions, the electro-chemo-mechanical approach reaches better results. In the no-teardown scenario (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10.), there is no significant difference in representing the battery behavior between the two estimation models because the number of the capacity sensitive parameters increased. The advantage of using the electro-chemo-mechanical approach stands in the reliability of its estimates.

5. Conclusion

In this work, a parameter estimation framework has been developed by integrating both electrochemical and mechanical measurements into the parameter estimation process. The inclusion of mechanical data, such as the battery thickness change, introduces additional constraints that significantly enhance the identifiability of key parameters, particularly those related to diffusion and reaction kinetics.

Two scenarios were considered: one where the battery underwent teardown to measure electrode thicknesses and the number of layers, and one without teardown. In the first case, the electrochemical-only estimation, constrained by fewer free parameters, converged to incorrect solutions while the electro-chemo-mechanical approach reached satisfying estimates with lower RMSEs and parameter variability. In the second case, when teardown was not performed and more parameters could be varied, the electrochemical approach yielded better estimates but still showed higher uncertainty compared to the electro-chemo-mechanical method. Integrating mechanical data consistently improve accuracy and robustness, reducing parameter variability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S, D.C. and F.P.; methodology, S.S.; software, S.S.; validation, S.S. and D.C.; formal analysis, D.C.; investigation, S.S, D.C. and F.P.; resources, A.S.; data curation, D.C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; writing—review and editing, D.C.; visualization, S.S; supervision, A.S.; project administration, A.S.; funding acquisition, A.S.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or supplementary material

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LIB |

Lithium-Ion Batterie |

| LSOF |

Least Square Objective Function |

| DFN |

Doyle-Fuller-Newmann |

| P2D |

Pseudo-Two-Dimensional |

| PDE |

Partial Differential Equation |

| EC |

Electrochemical |

| ECM |

Electro-chemo-mechanical |

| GA |

Genetic Algorithm |

| RMSE |

Root Mean Square Error |

References

- Martelli, S.; Mocera, F.; Somà, A. Carbon footprint of an orchard tractor through a life-cycle assessment approach. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1210. [CrossRef]

- Martelli, S.; Martini, V.; Mocera, F.; Soma’, A. Life Cycle Assessment Comparison of Orchard Tractors Powered by Diesel and Hydrogen Fuel Cell. Energies 2024, 17, 4599. [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.K.; Mathew, M.; Janhunen, S.; Panchal, S.; Raahemifar, K.; Fraser, R.; Fowler, M. A comprehensive equivalent circuit model for lithium-ion batteries, incorporating the effects of state of health, state of charge, and temperature on model parameters. Journal of Energy Storage 2021, 43, 103252. [CrossRef]

- Doyle, M.; Fuller, T.F.; Newman, J. Modeling of galvanostatic charge and discharge of the lithium/polymer/insertion cell. Journal of the Electrochemical society 1993, 140, 1526. [CrossRef]

- Khalik, Z.; Donkers, M.; Sturm, J.; Bergveld, H. Parameter estimation of the Doyle–Fuller–Newman model for Lithium-ion batteries by parameter normalization, grouping, and sensitivity analysis. Journal of Power Sources 2021, 499, 229901. [CrossRef]

- Jin, N.; Danilov, D.; Hof, P.; Donkers, M. Parameter estimation of an electrochemistry-based lithium-ion battery model using a two-step procedure and a parameter sensitivity analysis. International Journal of Energy Research 2018, 42. [CrossRef]

- Miguel, E.; Plett, G.L.; Trimboli, M.S.; Oca, L.; Iraola, U.; Bekaert, E. Review of computational parameter estimation methods for electrochemical models. Journal of Energy Storage 2021, 44, 103388. [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.; Onori, S. COBRAPRO: A MATLAB toolbox for Physics-based Battery Modeling and Co-simulation Parameter Optimization, 2024, [arXiv:eess.SY/2404.10022].

- Planden, B.; Courtier, N.E.; Robinson, M.; Khetarpal, A.; Planella, F.B.; Howey, D.A. PyBOP: A Python package for battery model optimisation and parameterisation, 2024, [arXiv:eess.SY/2412.15859].

- Zhang, L.; Wang, L.; Hinds, G.; Lyu, C.; Zheng, J.; Li, J. Multi-objective optimization of lithium-ion battery model using genetic algorithm approach. Journal of Power Sources 2014, 270, 367–378. [CrossRef]

- Clerici, D.; Mocera, F.; Soma, A. Electrochemical–mechanical multi-scale model and validation with thickness change measurements in prismatic lithium-ion batteries. Journal of Power Sources 2022, 542, 231735. [CrossRef]

- Mohtat, P.; Lee, S.; Sulzer, V.; Siegel, J.B.; Stefanopoulou, A.G. Differential Expansion and Voltage Model for Li-ion Batteries at Practical Charging Rates. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 2020, 167, 110561. [CrossRef]

- Rieger, B.; Schlueter, S.; Erhard, S.V.; Schmalz, J.; Reinhart, G.; Jossen, A. Multi-scale investigation of thickness changes in a commercial pouch type lithium-ion battery. Journal of Energy Storage 2016, 6, 213–221. [CrossRef]

- Sauerteig, D.; Hanselmann, N.; Arzberger, A.; Reinshagen, H.; Ivanov, S.; Bund, A. Electrochemical-mechanical coupled modeling and parameterization of swelling and ionic transport in lithium-ion batteries. Journal of Power Sources 2018, 378, 235–247. [CrossRef]

- Clerici, D.; Pistorio, F.; Scalzo, S.; Martelli, S.; Mocera, F.; Somà, A. Mechanical Multiscale Lithium-Ion Battery Modeling for Optimized Battery Pack Design. Engineering Proceedings 2025, 85. [CrossRef]

- Powell, M.J.D. The BOBYQA algorithm for bound constrained optimization without derivatives. 2009.

- Sun, W.; Li, Q.; Xiao, P.; Carbone, P. Determination of the tortuosity of a Li-ion battery separator. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 97, 112940. [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, A.; Dumitrescu, M.A.; Destro, M.; Santarelli, M. Inverse parameter determination in the development of an optimized lithium iron phosphate – Graphite battery discharge model. Journal of Power Sources 2016, 307, 160–172. [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.A.; O’Kane, S.E.J.; Brosa Planella, F.; Houx, J.L.; O’Regan, K.; Zyskin, M.; Edge, J.; Monroe, C.W.; Cooper, S.J.; Howey, D.A.; et al. Review of parameterisation and a novel database (LiionDB) for continuum Li-ion battery models. Progress in Energy 2022, 4, 032004. [CrossRef]

- Didier, C.; Pang, W.K.; Guo, Z.; Schmid, S.; Peterson, V.K. Phase Evolution and Intermittent Disorder in Electrochemically Lithiated Graphite Determined Using in Operando Neutron Diffraction. Chemistry of Materials 2020, 32, 2518–2531. [CrossRef]

- Padhi, A.K.; Nanjundaswamy, K.S.; Goodenough, J.B. Phospho-olivines as positive-electrode materials for rechargeable lithium batteries. Journal of the electrochemical society 1997, 144, 1188. [CrossRef]

- Schweidler, S.; de Biasi, L.; Schiele, A.; Hartmann, P.; Brezesinski, T.; Janek, J. Volume changes of graphite anodes revisited: a combined operando X-ray diffraction and in situ pressure analysis study. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2018, 122, 8829–8835. [CrossRef]

- Gomadam, P.M.; Weidner, J.W. Modeling volume changes in porous electrodes. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 2005, 153, A179. [CrossRef]

- Clerici, D. Mechanics of Lithium-Ion Batteries-A Modelling and Experimental Perspective 2024.

- Clerici, D.; Pistorio, F.; Mocera, F.; Somà, A. Mechanical characterization and modelling of lithium-ion batteries. Transportation Research Procedia 2023, 70, 276–283. [CrossRef]

- Zitzler, E.; Thiele, L. Multiobjective evolutionary algorithms: a comparative case study and the strength Pareto approach. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 1999, 3, 257–271. [CrossRef]

- Zitzler, E.; Deb, K.; Thiele, L. Comparison of Multiobjective Evolutionary Algorithms: Empirical Results. Evolutionary computation 2000, 8, 173–95. [CrossRef]

- Clerici, D.; Martelli, S.; Mocera, F.; Somà, A. Mechanical characterization of lithium-ion batteries with different chemistries and formats. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 84, 110899. [CrossRef]

- Northrop, P.W.C.; Ramadesigan, V.; De, S.; Subramanian, V.R. Publisher’s Note: Coordinate Transformation, Orthogonal Collocation, Model Reformulation and Simulation of Electrochemical-Thermal Behavior of Lithium-Ion Battery Stacks: [J. Electrochem. Soc., 158, A1461 (2011)]. Journal of the Electrochemical Society 2011, 159, S5. [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J. Modeling Diffusion-Induced Stress in Li-Ion Cells with Porous Electrodes. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 2010, 157, A366. [CrossRef]

- Doyle, M.; Fuentes, Y. Computer Simulations of a Lithium-Ion Polymer Battery and Implications for Higher Capacity Next-Generation Battery Designs. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 2003, 150, A706. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Crystal lattice strain of (a) LFP and (b) graphite as a function of lithium content expressed with the state of lithiation of the electrode.

Figure 1.

Crystal lattice strain of (a) LFP and (b) graphite as a function of lithium content expressed with the state of lithiation of the electrode.

Figure 2.

Electrochemical-mechanical model framework: from the lithium concentration obtained from P2D model to the particle deformation at different position along the electrode thickness direction (z). The superscript c and a stand for cathode and anode while l and p stand for lattice and particle, respectively. n and m denote the number of discretization points.

Figure 2.

Electrochemical-mechanical model framework: from the lithium concentration obtained from P2D model to the particle deformation at different position along the electrode thickness direction (z). The superscript c and a stand for cathode and anode while l and p stand for lattice and particle, respectively. n and m denote the number of discretization points.

Figure 3.

Teardown scenario - Comparison of (a) voltage profile and (b) thickness change between the experimental data and the model computed with the electrochemical (EC) and electro-chemo-mechanical (ECM) estimated parameters.

Figure 3.

Teardown scenario - Comparison of (a) voltage profile and (b) thickness change between the experimental data and the model computed with the electrochemical (EC) and electro-chemo-mechanical (ECM) estimated parameters.

Figure 4.

Teardown scenario - Comparison between electrochemical (EC) and electro-chemo-mechanical (ECM) estimation variability of (a) diffusion coefficients, (b) reaction rates and (c) material fractions of the electrodes.

Figure 4.

Teardown scenario - Comparison between electrochemical (EC) and electro-chemo-mechanical (ECM) estimation variability of (a) diffusion coefficients, (b) reaction rates and (c) material fractions of the electrodes.

Figure 5.

Teardown scenario - Comparison of (a) voltage profile and (b) thickness change between the experimental data and the model computed with the electrochemical (EC) and electro-chemo-mechanical (ECM) estimated parameters.

Figure 5.

Teardown scenario - Comparison of (a) voltage profile and (b) thickness change between the experimental data and the model computed with the electrochemical (EC) and electro-chemo-mechanical (ECM) estimated parameters.

Figure 6.

No teardown scenario - Comparison between electrochemical (EC) and electro-chemo-mechanical (ECM) estimation variability of (a) diffusion coefficients, (b) reaction rates, (c) material fractions and (d) thickness of the electrodes.

Figure 6.

No teardown scenario - Comparison between electrochemical (EC) and electro-chemo-mechanical (ECM) estimation variability of (a) diffusion coefficients, (b) reaction rates, (c) material fractions and (d) thickness of the electrodes.

Figure 7.

Teardown scenario - Comparison of (a) voltage profile and (b) thickness change between the experimental data and the model computed with the electrochemical (EC) estimated parameters.

Figure 7.

Teardown scenario - Comparison of (a) voltage profile and (b) thickness change between the experimental data and the model computed with the electrochemical (EC) estimated parameters.

Figure 8.

Teardown scenario - Comparison of (a) voltage profile and (b) thickness change between the experimental data and the model computed with the electro-chemo-mechanical (ECM) estimated parameters.

Figure 8.

Teardown scenario - Comparison of (a) voltage profile and (b) thickness change between the experimental data and the model computed with the electro-chemo-mechanical (ECM) estimated parameters.

Figure 9.

No teardown scenario - Comparison of (a) voltage profile and (b) thickness change between the experimental data and the model computed with the electrochemical (EC) estimated parameters.

Figure 9.

No teardown scenario - Comparison of (a) voltage profile and (b) thickness change between the experimental data and the model computed with the electrochemical (EC) estimated parameters.

Figure 10.

No teardown scenario - Comparison of (a) voltage profile and (b) thickness change between the experimental data and the model computed with the electro-chemo-mechanical (ECM) estimated parameters.

Figure 10.

No teardown scenario - Comparison of (a) voltage profile and (b) thickness change between the experimental data and the model computed with the electro-chemo-mechanical (ECM) estimated parameters.

Table 1.

Governing equations of the P2D model for LIBs. The subscripts n, p, and s stand for the negative electrode, positive electrode and separator, respectively.

Table 1.

Governing equations of the P2D model for LIBs. The subscripts n, p, and s stand for the negative electrode, positive electrode and separator, respectively.

| Description |

Governing equations |

Boundary conditions |

| Mass conservation |

| Active material particles,

|

|

|

|

| Electrolyte,

|

|

|

|

| Charge conservation |

| Active material particles,

|

|

|

|

| Electrolyte,

|

|

|

|

| Reaction kinetics |

| Butler-Volmer |

|

|

- |

| Exchange current |

|

|

- |

| Overpotential

|

|

|

|

- |

Table 2.

Fixed parameters: l, from the literature; c, calculated; m, measured.

Table 2.

Fixed parameters: l, from the literature; c, calculated; m, measured.

| Parameter |

Symbol |

Cathode |

Separator |

Anode |

Unit |

| Molar mass |

|

c

|

− |

79 c

|

|

| Crystal density |

|

3600 l

|

− |

2260 l

|

|

| Maximum concentration |

|

22820 c

|

− |

28600 c

|

|

| Electrolyte diffusivity |

|

l [29] |

l [29] |

l [29] |

|

| Solid-phase conductivity |

|

6 l [18] |

− |

100 l [30] |

|

| Transference number |

|

|

l [18] |

|

− |

| Bruggeman coefficient |

|

|

l [31] |

|

− |

| Particle radius |

|

m

|

− |

10 m

|

|

Table 3.

Teardown scenario - Parameters bound and comparison between the electrochemical (EC) and electro-chemo-mechanical (ECM) estimate.

Table 3.

Teardown scenario - Parameters bound and comparison between the electrochemical (EC) and electro-chemo-mechanical (ECM) estimate.

| Current Rate |

Symbol |

Initial Value |

Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

EC Estimate |

ECM Estimate |

Unit |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

− |

|

|

|

|

|

|

− |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 4.

Teardown scenario - RMSEs of the voltage profile, thickness change and capacity.

Table 4.

Teardown scenario - RMSEs of the voltage profile, thickness change and capacity.

| Property |

RMSE - EC |

RMSE - ECM |

Unit |

| Voltage |

0.0692 |

0.0052 |

V |

| Thickness change |

0.0258 |

0.0091 |

|

| Capacity |

3.92 |

0.174 |

|

Table 5.

No teardown scenario - Parameters bound and comparison between the electrochemical (EC) and electro-chemo-mechanical (ECM) estimate.

Table 5.

No teardown scenario - Parameters bound and comparison between the electrochemical (EC) and electro-chemo-mechanical (ECM) estimate.

| Current Rate |

Symbol |

Initial Value |

Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

EC Estimate |

ECM Estimate |

Unit |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

− |

|

|

|

|

|

|

− |

|

67 |

50 |

100 |

|

|

|

|

57 |

50 |

100 |

|

61 |

|

| N |

140 |

135 |

145 |

143 |

143 |

− |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 6.

No teardown scenario - RMSEs of the voltage profile, thickness change and capacity.

Table 6.

No teardown scenario - RMSEs of the voltage profile, thickness change and capacity.

| Property |

EC |

ECM |

Unit |

| Voltage |

0.057 |

0.063 |

V |

| Thickness change |

0.0126 |

0.0120 |

|

| Capacity |

0.65 |

0.84 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).