Submitted:

14 May 2025

Posted:

15 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample Selection

Study Population and Sampling

Sample Size

Inclusion Criteria

Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Collection Tools

2.4. Data Analysis

Microbiological Studies

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Participants

3.2. Prevalence of UTIs Among Pregnant Women: Sociodemographic, Obstetric, and Clinical Factors

3.3. Risk Factors for UTIs During Pregnancy

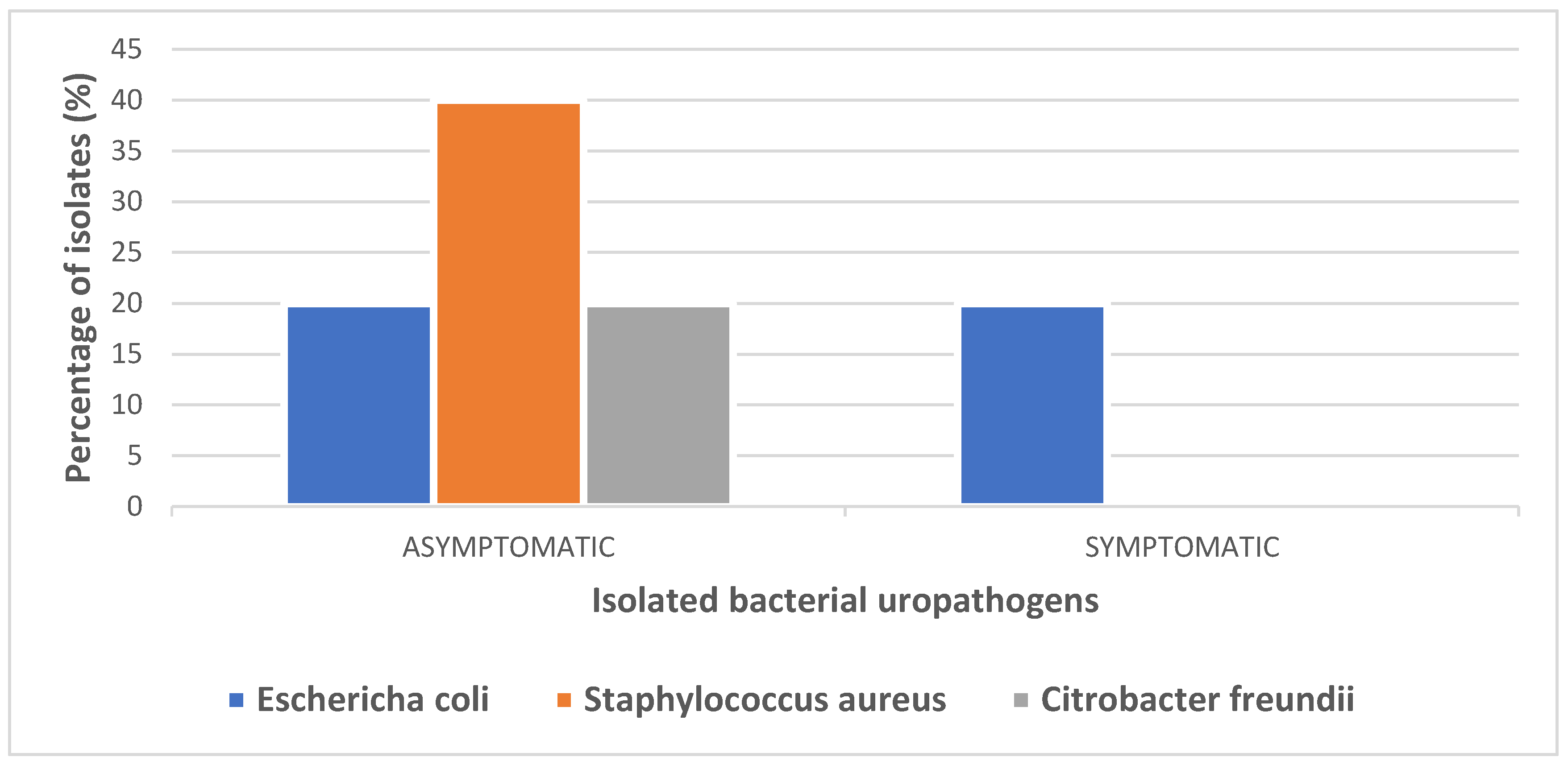

3.4. Bacterial Pathogens Isolated from Urine Cultures

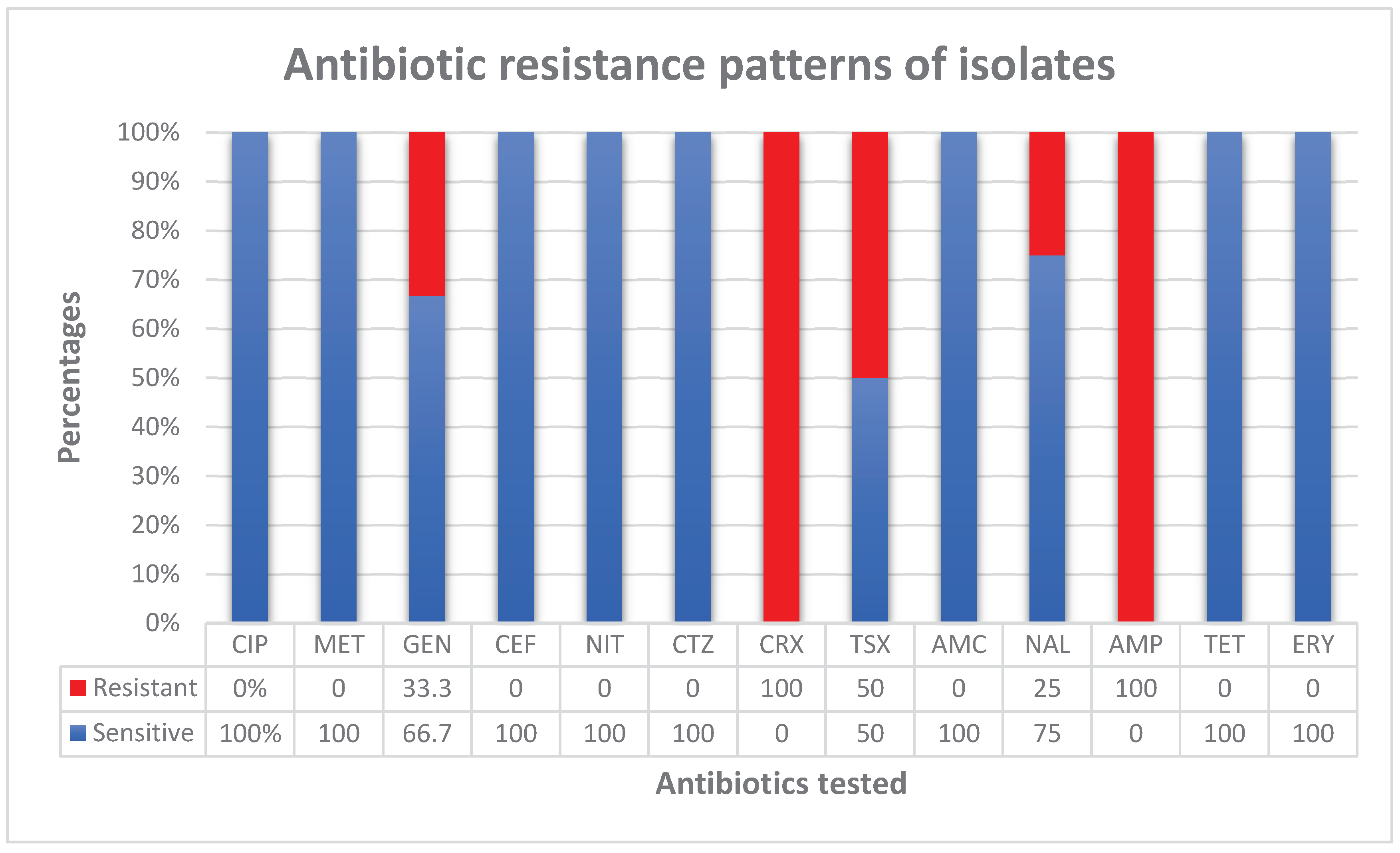

3.5. Prevalence of AMR and Its Patterns

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

List of Abbreviations

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| E. coli | Escherichia coli |

| S. aureus | Staphylococcus aureus |

| C. freundii | Citrobacter freundii |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| USD | United States Dollars |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| UTI | Urinary tract infection |

| EUA | European Urology Association |

| ASB | Asymptomatic bacteriuria |

| MDR | Multidrug resistant |

| ANC | Antenatal clinic |

| EFSTH | Edward Francis Small Teaching Hospital |

| KGH | Kanifing General Hospital |

| BMCHH | Bundung Maternal and Child Health Hospital |

| CFU | Colony forming units |

| GMD | Gambian Dalasi |

| LMICs | Low- to middle-income countries |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| CLED | Cysteine lactose electrolyte-deficient agar |

| MAC | MacConkey agar |

| MHA | Mueller‒Hinton agar |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

References

- Chelkeba, L.; Fanta, K.; Mulugeta, T.; Melaku, T. Bacterial profile and antimicrobial resistance patterns of common bacteria among pregnant women with bacteriuria in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 306, 663–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salari, N.; Khoshbakht, Y.; Hemmati, M.; Khodayari, Y.; Khaleghi, A.; Jafari, F.; Shohaimi, S.; Mohammadi, M. Global prevalence of urinary tract infection in pregnant mothers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Heal. 2023, 224, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis,” Lancet, vol. 399, pp. 629–55, 2022.

- B. M. A and S. M, “A Systematic Review on Drug Resistant Urinary Tract Infection Among Pregnant Women in Developing Countries in Africa and Asia; 2005–2016,” Infect. Drug Resist., vol. 13, pp. 1465–77, 2020.

- J. Marcon, C. G. Stief, and G. Magistro, “Harnwegsinfektionen: Was ist gesichert in der Therapie?,” Internist, vol. Dec;58(12):1242–9, 2017.

- Johnson, B.; Stephen, B.M.; Joseph, N.; Asiphas, O.; Musa, K.; Taseera, K. Prevalence and bacteriology of culture-positive urinary tract infection among pregnant women with suspected urinary tract infection at Mbarara regional referral hospital, South-Western Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azami, M.; Jaafari, Z.; Masoumi, M.; Shohani, M.; Badfar, G.; Mahmudi, L.; Abbasalizadeh, S. The etiology and prevalence of urinary tract infection and asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant women in Iran: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. BMC Urol. 2019, 19, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Aydoğmuş and E. Kaya Kiliç, “Determination of antibiotic resistance rates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates, which are the causative agents of urinary tract infection in pregnant women,” Anatol. Curr Med JACMJacmj, vol. 27;5(2):97–101, Mar. 2023.

- Abushaheen, M.A.; Fatani, A.J.; Alosaimi, M.; Mansy, W.; George, M.; Acharya, S.; Rathod, S.; Divakar, D.D.; Jhugroo, C.; et al. Antimicrobial resistance, mechanisms and its clinical significance. Dis. Mon. 2020, 66, 100971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndmason, L.M.; Marbou, W.J.; Kuete, V. Urinary tract infections, bacterial resistance and immunological status: a cross sectional study in pregnant and non-pregnant women at Mbouda Ad-Lucem Hospital. Afr. Heal. Sci. 2019, 19, 1525–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedze-Kpodo, R.K.; Feglo, P.K.; Agboli, E.; Asmah, R.H.; Kwadzokpui, P.K. Genotypic characterization of extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing urinary isolates among pregnant women in Ho municipality, Ghana. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Lawati, H.; Blair, B.M.; Larnard, J. Urinary Tract Infections: Core Curriculum 2024. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2024, 83, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darboe, S.; Mirasol, R.; Adejuyigbe, B.; Muhammad, A.K.; Nadjm, B.; Maurice, A.D.S.; Dogan, T.L.; Ceesay, B.; Umukoro, S.; Okomo, U.; et al. Using an Antibiogram Profile to Improve Infection Control and Rational Antimicrobial Therapy in an Urban Hospital in The Gambia, Strategies and Lessons for Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebbeh, A.; Dsane-Aidoo, P.; Sanyang, K.; Darboe, S.M.K.; Fofana, N.; Ameme, D.; Sanyang, A.M.; Darboe, K.S.; Darboe, S.; Sanneh, B.; et al. Antibiotics susceptibility patterns of uropathogenic bacteria: a cross-sectional analytic study at Kanifing General Hospital, The Gambia. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sifri, Z.; Chokshi, A.; Cennimo, D.; Horng, H. Global contributors to antibiotic resistance. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2019, 11, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A.J. A, N. M, and A. A. N, “The threat of antimicrobial resistance in developing countries: causes and control strategies,” Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control, vol. 6, no. 47, 2017.

- E. Britannica, “The Gambia summary” [Internet] [Internet.” 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.britannica.com/summary/The-Gambia.

- C. C. Serdar, M. Cihan, D. Yücel, and M. A. Serdar, “Sample size, power and effect size revisited: simplified and practical approaches in preclinical, clinical and laboratory studies,” Biochem Med Zagreb, vol. 15;31(1):010502, Feb. 2021.

- M. Ali and A. M.S, “Prevalence of Urinary Tract Infection among Pregnant Women in Kano, Nothern Nigeria,” Arch. Reprod. Med. Sex. Health, vol. 2, no. Issue 1, pp. 23–9, 2019.

- Balakrishnan, S.; Derese, B.; Kedir, H.; Teklemariam, Z.; Weldegebreal, F. Bacterial profile of urinary tract infection and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern among pregnant women attending at Antenatal Clinic in Dil Chora Referral Hospital, Dire Dawa, Eastern Ethiopia. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2016, 12, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Cheesbrough, District Laboratory Practice in Tropical Countries, 2nd ed. London, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- P. M. Tille, Bailey & Scott’s diagnostic microbiology, Fifteenth Edition. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier, 2022.

- B. A. W, K. W. M, S. J. C, and T. M, “Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method,” Am. J. Clin. Pathol., vol. 45, no. 4, pp. 493–6, 1966.

- C.L.S.I., Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 27th ed., vol. 37. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2019.

- Rosana, Y.; Ocviyanti, D.; Halim, M.; Harlinda, F.Y.; Amran, R.; Akbar, W.; Billy, M.; Akhmad, S.R.P. Urinary Tract Infections among Indonesian Pregnant Women and Its Susceptibility Pattern. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 2020, 9681632–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, S.; Lohiya, A.; Kapil, A.; Gupta, S. Urinary tract infection among pregnant women at a secondary level hospital in Northern India. Indian J. Public Heal. 2017, 61, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tula, A.; Mikru, A.; Alemayehu, T.; Dobo, B. Bacterial Profile and Antibiotic Susceptibility Pattern of Urinary Tract Infection among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Care at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Southern Ethiopia. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med Microbiol. 2020, 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejali, M.; Ahmadi, S.S. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Urinary Tract Infection among Pregnant Women in Shahrekord, Iran. Int. J. epidemiologic Res. 2019, 6, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orji, O.; Dlamini, Z.; Wise, A.J. Urinary bacterial profile and antibiotic susceptibility pattern among pregnant women in Rahima Moosa Mother and Child Hospital, Johannesburg. South. Afr. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 37, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nteziyaremye, J.; Iramiot, S.J.; Nekaka, R.; Musaba, M.W.; Wandabwa, J.; Kisegerwa, E.; Kiondo, P. Asymptomatic bacteriuria among pregnant women attending antenatal care at Mbale Hospital, Eastern Uganda. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0230523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.R.; Omar, H.H.H.; Abd-Allah, I.M. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Urinary Tract Infection among Pregnant Women in Ismailia City, Egypt. IOSR J. Nurs. Heal. Sci. 2017, 6, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. R. Oyedeji, G. O. Daramola, H. A. Edogun, O. O. Ogunfolakan, H. A. Egbebi, and A. O. Ojerinde, “Polybacteria in Urinary Tract Infection among Antenatal Patients.” Attending University Teaching Hospital Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State, Nigeria.

- H. ohamoud, S. Tadesse, and A. Derbie, “Antimicrobial resistance and ESBL profile of Uropathogens among pregnant women at Edna Adan Hospital, Hargeisa, Somaliland,” Ethiop J Health Sci, vol. May;31(3):645–52, 2021.

- Negussie, G.A. Worku, and E. Beyene, “Bacterial identification and drug susceptibility pattern of urinary tract infection in pregnant Women at Karamara Hospital Jigjiga, Eastern Ethiopia,” Afr. J. Bacteriol. Res., vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 15–22, Jul. 2018.

- T. N. C, O. E. C, N. C. C, E. E. C, N. N. T, and M. E, “Clinical presentation, risk factors and pathogens involved in bacteriuria of pregnant women attending antenatal clinic of 3 hospitals in a developing country: a cross sectional analytic study,” BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, vol. Dec;19(1):143, 2019.

- Fosu, K.; Quansah, E.; Dadzie, I. Antimicrobial Profile and Asymptomatic Urinary Tract Infections among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Clinic in Bolgatanga Regional Hospital, Ghana. Microbiol. Res. J. Int. 2019, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matalka, A.; Al-Husban, N.; Alkuran, O.; Almuhaisen, L.; Basha, A.; Eid, M.; Elmuhtaseb, M.S.; Al Oweidat, K. Spectrum of uropathogens and their susceptibility to antimicrobials in pregnant women: a retrospective analysis of 5-year hospital data. J. Int. Med Res. 2021, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L. A.-K. MM, “Urinary Tract Infection among Pregnant Women and its Associated Risk Factors: A Cross-Sectional Study,” Biomed Pharmacol J, vol. 31;12(04):2003–10, Dec. 2019.

- A.O. Forson, W. B. Tsidi, D. Nana-Adjei, M. N. Quarchie, and N. Obeng-Nkrumah, “Escherichia coli bacteriuria in pregnant women in Ghana: antibiotic resistance patterns and virulence factors,” BMC Res Notes, vol. Dec;11(1):901, 2018.

- Karikari, A.B.; Saba, C.K.S.; Yamik, D.Y. Assessment of asymptomatic bacteriuria and sterile pyuria among antenatal attendants in hospitals in northern Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Nwachukwu, “Prevalence of urinary tract infections in pregnant women in Onitsha.” Nigeria. [Online]. Available: https://medcraveonline.com/JBMOA/prevalence-of-urinary-tract-infections-in-pregnant-women-in-onitsha-nigeria.

- Oli, A.N.; Akabueze, V.B.; Ezeudu, C.E.; Eleje, G.U.; Ejiofor, O.S.; Ezebialu, I.U.; Oguejiofor, C.B.; Ekejindu, I.M.; Emechebe, G.O.; Okeke, K.N. Bacteriology and Antibiogram of Urinary Tract Infection Among Female Patients in a Tertiary Health Facility in South Eastern Nigeria. Open Microbiol. J. 2017, 11, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wabe, Y.A.; Reda, D.Y.; Abreham, E.T.; Gobene, D.B.; Ali, M.M. Prevalence of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria, Associated Factors and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profile of Bacteria Among Pregnant Women Attending Saint Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2020, ume 16, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, H.D.; Diório, G.R.M.; Peres, S.V.; Francisco, R.P.V.; Galletta, M.A.K. Bacterial profile and prevalence of urinary tract infections in pregnant women in Latin America: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Younis, S. Ajroud, E. L. H. A, U. A. S, and E. R. A, “Prevalence of Urinary Tract Infection among Pregnant Women and Its Risk Factor in Derna City,” Sch. Int. J. Obstet. Gynecol., vol. Aug;2(8):219–23, 2019.

- Ejerssa, A.W.; Gadisa, D.A.; Orjino, T.A. Prevalence of bacterial uropathogens and their antimicrobial susceptibility patterns among pregnant women in Eastern Ethiopia: hospital-based cross-sectional study. BMC Women's Heal. 2021, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeta, K.I.; Michelo, C.; Jacobs, C. Antimicrobial Resistance among Pregnant Women with Urinary Tract Infections Attending Antenatal Clinic at Levy Mwanawasa University Teaching Hospital (LMUTH), Lusaka, Zambia. Int. J. Microbiol. 2021, 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koffi, K.A.; Aka, E.K.; Apollinaire, H.; Britoh, A.M.; Konan, J.M.P. Epidemiological, bacteriological profile and bacterial resistance of urinary tract infections at pregnant woman in prenatal consultation in African setting. Int. J. Reprod. Contraception, Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 9, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taye, S.; Getachew, M.; Desalegn, Z.; Biratu, A.; Mubashir, K. Bacterial profile, antibiotic susceptibility pattern and associated factors among pregnant women with Urinary Tract Infection in Goba and Sinana Woredas, Bale Zone, Southeast Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales, M.; Corrales-Acosta, E.; Corrales-Riveros, J.G. Which Antibiotic for Urinary Tract Infections in Pregnancy? A Literature Review of International Guidelines. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 7226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Kadri, H.M.; El-Metwally, A.A.; Al Sudairy, A.A.; Al-Dahash, R.A.; Al Khateeb, B.F.; Al Johani, S.M. Antimicrobial resistance among pregnant women with urinary tract infections is on rise: Findings from meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Infect. Public Heal. 2024, 17, 102467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu, D.; Abula, T.; Zewdu, T.; Berhanu, M.; Sahilu, T. Asymptomatic Bacteriuria, antimicrobial susceptibility pattern and associated risk factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Assosa General Hospital, Western Ethiopia. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Bizuwork, H. K. Bizuwork, H. Alemayehu, G. Medhin, W. Amogne, and T. Eguale, “Asymptomatic Bacteriuria among Pregnant Women in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Prevalence, Causal Agents, and Their Antimicrobial Susceptibility,” Int. J. Microbiol., vol. 2021, pp. 1–8, Jul. 2021.

- Ali, A.H.; Reda, D.Y.; Ormago, M.D. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of urinary tract infection among pregnant women attending Hargeisa Group Hospital, Hargeisa, Somaliland. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karikari, A.B.; Saba, C.K.S.; Yamik, D.Y. Assessment of asymptomatic bacteriuria and sterile pyuria among antenatal attendants in hospitals in northern Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Pandey, S.; Maheshwari, U.; Singh, M.; Srivastava, J.; Bose, S. Prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria and antimicrobial resistance profile among pregnant females in a Tertiary Care Hospital. Indian J. Community Med. 2021, 46, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngong, I.N.; Fru-Cho, J.; Yung, M.A.; Akoachere, J.-F.K.T. Prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibility pattern and associated risk factors for urinary tract infections in pregnant women attending ANC in some integrated health centers in the Buea Health District. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmat, U.; Mumtaz, M.Z.; Malik, A. Rising prevalence of multidrug-resistant uropathogenic bacteria from urinary tract infections in pregnant women. J. Taibah Univ. Med Sci. 2021, 16, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darboe, S.; Dobreniecki, S.; Jarju, S.; Jallow, M.; Mohammed, N.I.; Wathuo, M.; Ceesay, B.; Tweed, S.; Roy, R.B.; Okomo, U.; et al. Prevalence of Panton-Valentine Leukocidin (PVL) and Antimicrobial Resistance in Community-Acquired Clinical Staphylococcus aureus in an Urban Gambian Hospital: A 11-Year Period Retrospective Pilot Study. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onanuga, A.; Omeje, M.C.; Eboh, D.D. Carriage of multi-drug resistant urobacteria by asymptomatic pregnant women in yenagoa, bayelsa state, nigeria. Afr. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 12, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| VARIABLE | PARTICIPANTS (n=100) | |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | |

|

Hospital KGH BMCHH EFSTH |

52 34 14 |

52 34 14 |

|

Age Less than 20 20–24 25–29 30–34 35–39 40 and above |

6 26 28 21 16 3 |

6 26 28 21 16 3 |

|

Residence Urban Rural |

100 0 |

100 0 |

|

Level of education No formal education Primary (1-6) Secondary (7-12) Tertiary |

23 11 49 17 |

23 11 49 17 |

|

Occupation Housewife Student Self employed Employee (Government or private) |

48 9 29 14 |

48 9 29 14 |

|

Marital status Single Married |

2 98 |

2 98 |

|

Gravidity Primigravida Multigravida |

31 69 |

31 69 |

|

Parity Nullipara Primipara Multipara |

33 23 44 |

33 23 44 |

|

Estimated Gestational Age 1st trimester 2nd trimester 3rd trimester |

7 30 63 |

7 30 63 |

|

History of UTI Yes No |

37 63 |

37 63 |

| History of catheterization | 0 | 0 |

|

History of antibiotic use without prescription Yes No |

29 71 |

29 71 |

|

Comorbidity present Diabetes mellitus HIV/AIDS Renal disease Others |

1 0 0 10 |

1 0 0 10 |

|

Symptomatic Yes No |

7 93 |

7 93 |

| VARIABLE | PARTICIPANTS (n=100) | CULTURE STATUS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | POSITIVE no (%) (n=5) | NEGATIVE no (%) (n=95) | p value (X2) | |

|

Hospital KGH BMCHH EFSTH |

52 34 14 |

52 34 14 |

0 (0) 4 (80) 1 (20) |

52 (54.7) 30 (31.6) 13 (13.7) |

0.046 |

|

Age Less than 20 20–24 25–29 30–34 35–39 40 and above |

6 26 28 21 16 3 |

6 26 28 21 16 3 |

1 (20) 1 (20) 1 (20) 2 (40) 0 (0) 0 (0) |

5 (5.3) 25 (26.3) 27 (28.4) 19 (20) 16 (16.8) 3 (3.2) |

0.363 |

|

Residence Urban Rural |

97 3 |

97 3 |

5 (100) 0 (0) |

92 (96.8) 3 (3.2) |

0.687 |

|

Level of education No formal education Primary (1-6) Secondary (7-12) Tertiary |

23 11 49 17 |

23 11 49 17 |

2 (40) 0 (0) 2 (40) 1 (20) |

21 (22.1) 11 (11.6) 47 (49.5) 16 (16.8) |

0.716 |

|

Occupation Housewife Student Self employed Employee (Government or private) |

48 9 29 14 |

48 9 29 14 |

4 (80) 0 (0) 1 (10) 0 (0) |

44 (46.3) 9 (9.5) 28 (29.5) 14 (14.7) |

0.437 |

|

Marital status Single Married |

2 98 |

2 98 |

0 (0) 5 (100) |

2 (2.1) 93 (97.9) |

0.743 |

|

Gravidity Primigravida Multigravida |

31 69 |

31 69 |

1 (20) 4 (80) |

30 (31.6) 65 (68.4) |

0.687 |

|

Parity Nullipara Primipara Multipara |

33 23 44 |

33 23 44 |

1 (20) 3 (60) 1 (20) |

32 (33.7) 20 (21) 43 (45.3) |

0.129 |

|

Estimated Gestational Age 1st trimester 2nd trimester 3rd trimester |

7 30 63 |

7 30 63 |

0 (0) 3 (60) 2 (40) |

7 (7.4) 27 (28.4) 61 (64.2) |

0.303 |

|

History of UTI Yes No |

37 63 |

37 63 |

2 (40) 3 (60) |

35 (36.8) 60(63.2) |

0.887 |

| History of catheterization | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

|

History of antibiotic use without prescription Yes No |

29 71 |

29 71 |

2 (40) 3 (60) |

27 (28.4) 68 (71.6) |

0.841 |

|

History of diabetes mellitus Yes No |

1 99 |

1 99 |

0 (0) 5 (100) |

1 (1.1) 94 (98.9) |

0.818 |

|

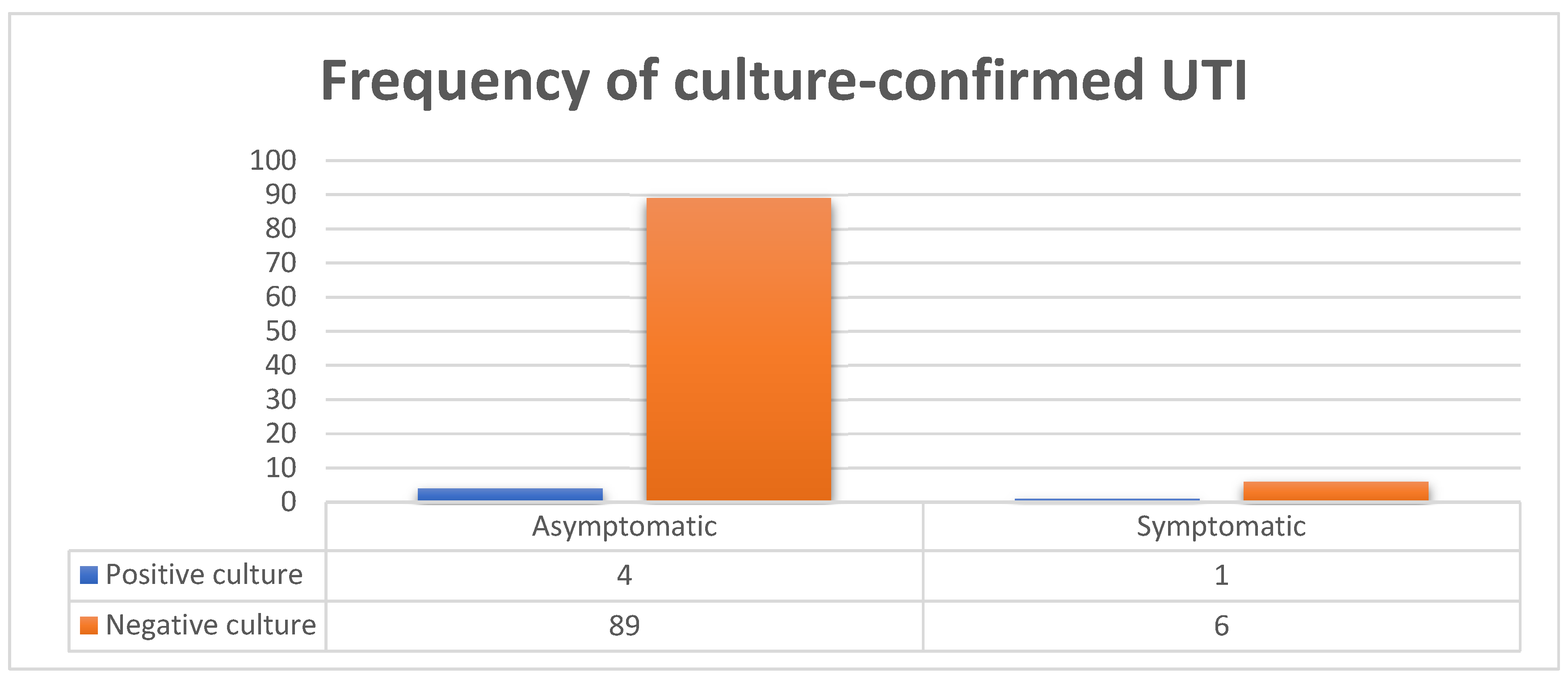

Symptomatic Yes No |

7 93 |

7 93 |

1 (20) 4 (80) |

6 (6.3) 89 (93.7) |

0.242 |

| BACTERIAL ISOLATES | ASYMPTOMATIC | SYMPTOMATIC | TOTAL(n=100) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | 1 | 1 | 2(40%) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 2 | 0 | 2(40%) |

| Citrobacter freundii | 1 | 0 | 1(20%) |

| TOTAL | 4 | 1 | 5(100%) |

| BACTERIAL ISOLATES | Escherichia coli | Staphylococcus aureus | Citrobacter freundii | TOTAL | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | |||||

| SUSCEPTIBILITY | S | R | S | R | S | R | S | R | |

| ANTIBIOTICS TESTED/NO OF ISOLATES | CIP | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - |

| MET | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | |

| GEN | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | |

| CEF | 2 | 0 | - | - | 1 | 0 | 3 | - | |

| NIT | 2 | 0 | 1 | - | 1 | 0 | 4 | - | |

| CTZ | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | |

| CRX | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | |

| TSX | 1 | - | - | - | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| AMC | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | 2 | - | |

| NAL | 2 | 0 | 1 | - | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |

| AMP | - | 1 | - | - | 0 | 1 | - | 2 | |

| TET | 1 | - | 2 | 0 | - | - | 3 | - | |

| ERY | - | - | 2 | 0 | - | - | 2 | - | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).