1. Introduction

Urinary infections are one of the main infections that affect humans. A urinary infection is considered to be the existence of microorganisms in any part of the urinary system, with the exception of the distal component of the urethra, where some microorganisms may exist without resulting in infection.

There are several reasons that justify these high values, such as the close proximity between the urethra and the anus and the direct contact with the external environment through the urethra (1). In the case of women, for anatomical but also hormonal reasons, the probability of developing urinary infections is much higher than that of men, and it is estimated that they may have at least one urinary infection throughout their lives (2). There are also other conditions that can increase the likelihood of acquiring a urinary infection, such as diabetes mellitus, urinary incontinence, anatomical defects in the urinary system, immobility, urinary retention, increasing age and immunosuppression (3). Urinary infections can occur via the ascending route (ascent of microorganisms through the urethra), the most common being the hematogenous route (very associated with newborns) and the lymphatic route (a rare situation associated with intestinal infections) (4).

Enterobacteria are always the most prevalent bacteria in urinary tract infections, with emphasis on Escherichia coli. Although this is the most prevalent bacteria, its values vary, and in community-acquired infections they are much higher while in healthcare-associated infections they are lower – in this type of infections there are many more strains involved, since that we talk about a hospital flora. In second place, Klebsiella pneumoniae usually appears as the most prevalent bacteria (5).

The treatment of bacterial urinary infections is done through the use of antibiotics, after carrying out a urine culture. This analysis allows urine to be collected and analyzed, in order to identify the microorganism causing the urinary infection and the respective antibiotic test, identifying those that are sensitive to resistance. Currently, there are other microbiological techniques, which cover the area of molecular biology and whose main objective is to reduce the time required for a urine culture result, which will never be less than 48 hours (6). The reference technique is still urine culture, but these developments should make it possible to reduce the time that classical microbiology needs to respond and thus contribute to mitigating one of the major associated problems, which involves the need for empirical therapy, whenever there is no other alternative. clinic that can be used while awaiting the microbiological result (7).

From a physiological point of view, pregnancy is a state that can also contribute to an increase in urinary infections. In fact, urinary tract infections are the most common among pregnant women and can be associated with an increased risk of death or morbidity, both maternal and fetal (8). Among the various associated explanations, emphasis is placed on the expansion of the uterus and the hormonal component, which leads to a decrease in urine flow and greater retention (9). There is therefore an increased likelihood of bacteria in the urinary tract, resulting not only in symptomatic bacteriuria (in which identification is facilitated because the pregnant woman's symptoms lead her to seek support), but there may also be asymptomatic bacteriuria, with the presence of bacteria in the urinary tract, but without the characteristic symptoms (10,11). It is therefore essential that all pregnant women are screened for the presence of bacteria in the urine and that whenever this is detected, associated therapy should occur, since even asymptomatic bacteriuria presents a risk of progression to pyelonephritis or other associated complications (11). After this treatment, recommended by most guidelines as being limited to three days of antibiotic therapy, follow-up must be maintained. The treatment of urinary infections in pregnant women is of crucial importance and imperative, considering the negative impact and evolution that the infection will have if not resolved in a timely manner (12,13).

Similar to the general population, Escherichia coli is also the most prevalent bacteria associated with urinary infections in pregnant women (14). Experimental work using animals suggests that Escherichia coli may be associated with the induction of early labor, however this model has not yet been proven in humans (14). The objetives were Characterize urinary infections associated with pregnant women; Study the most prevalent strains in urinary infections in pregnant women; Analyze the antibiogram of the most prevalent strains in infections in pregnant women.

2. Materials and Methods

A retrospective observational study was carried out on all positive urine cultures from pregnant women between January 2018 and December 2022 at a Hospital Center in the Center of Portugal, totaling 201 samples. Data were collected with computer support, including age, origin (urgency, hospitalization or consultation), previous antibiotic therapy (yes or no), catheterization (yes or no), isolated bacteria (strain) and tested antibiotic therapy (sensitive or resistant).

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software, version 29.0.1 for Mac IOS. Descriptive statistics and inferential statistics were used to compare groups, using the t test for independent samples (normal distribution) or the Mann-Whitney U test (non-normal distribution).

This work is part of the ITUCIP study (Urinary Tract Infections in the Interior Center of Portugal).

3. Results

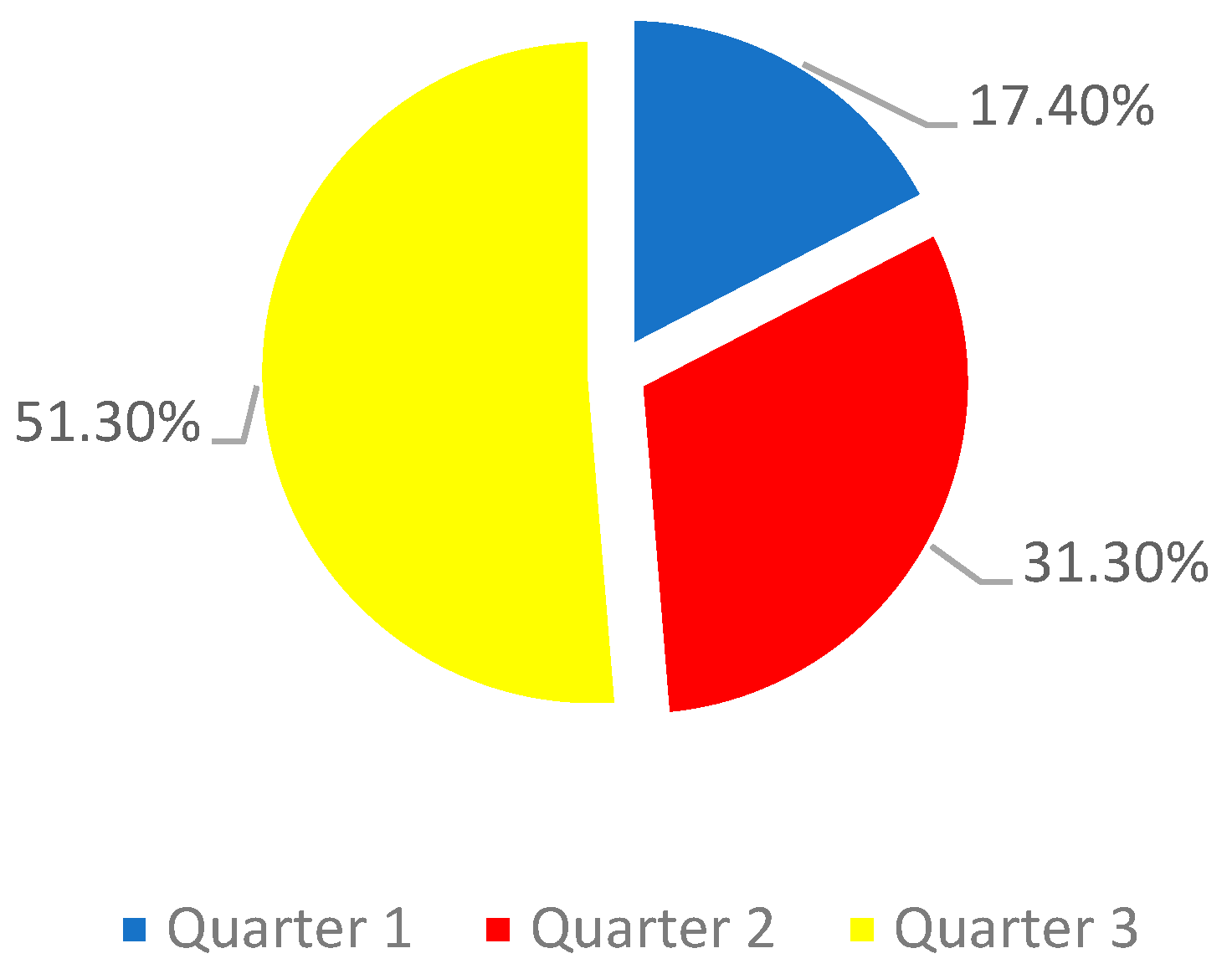

The study sample consisted of 201 pregnant women, with an average age of 32.3 years. The majority of pregnant women were in the third trimester of pregnancy (graph 1)

Graph 1.

Sample distribution by quarter.

Graph 1.

Sample distribution by quarter.

Only one of the women had a catheter (0.49%) and was in the third trimester of pregnancy. 1.9% of pregnant women were receiving prior antibiotic therapy at the time of urine collection for urine culture. Of these, 50% were in the third quarter, 25% in the second quarter and 25% in the first quarter.

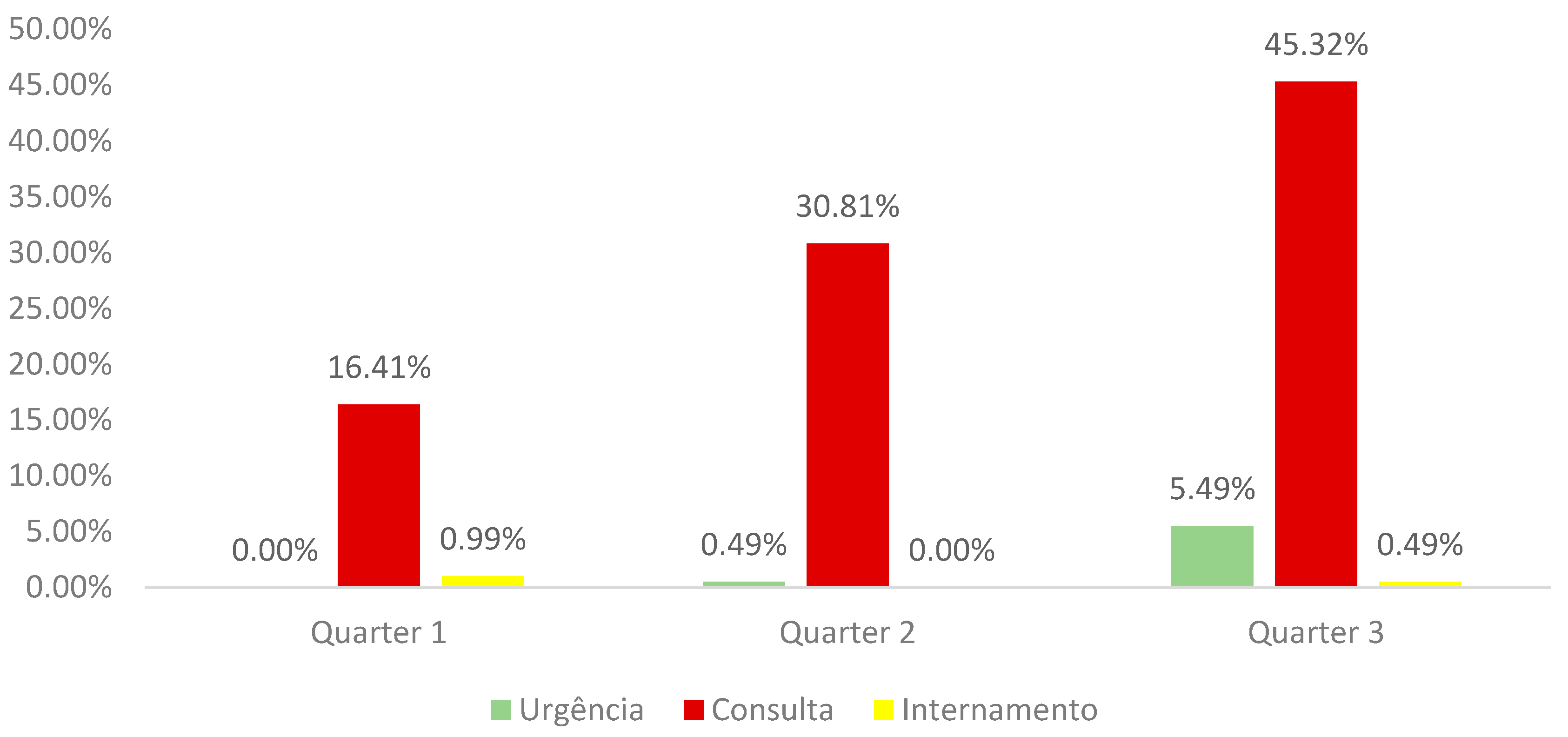

92.52% of pregnant women came from the Outpatient Clinic, 5.98% from the Emergency Department and 1.5% from the Inpatient Department. Analyzing this data by quarter we observed (graph 2):

Graph 2.

Distribution of the sample by trimester of pregnancy and service of origin.

Graph 2.

Distribution of the sample by trimester of pregnancy and service of origin.

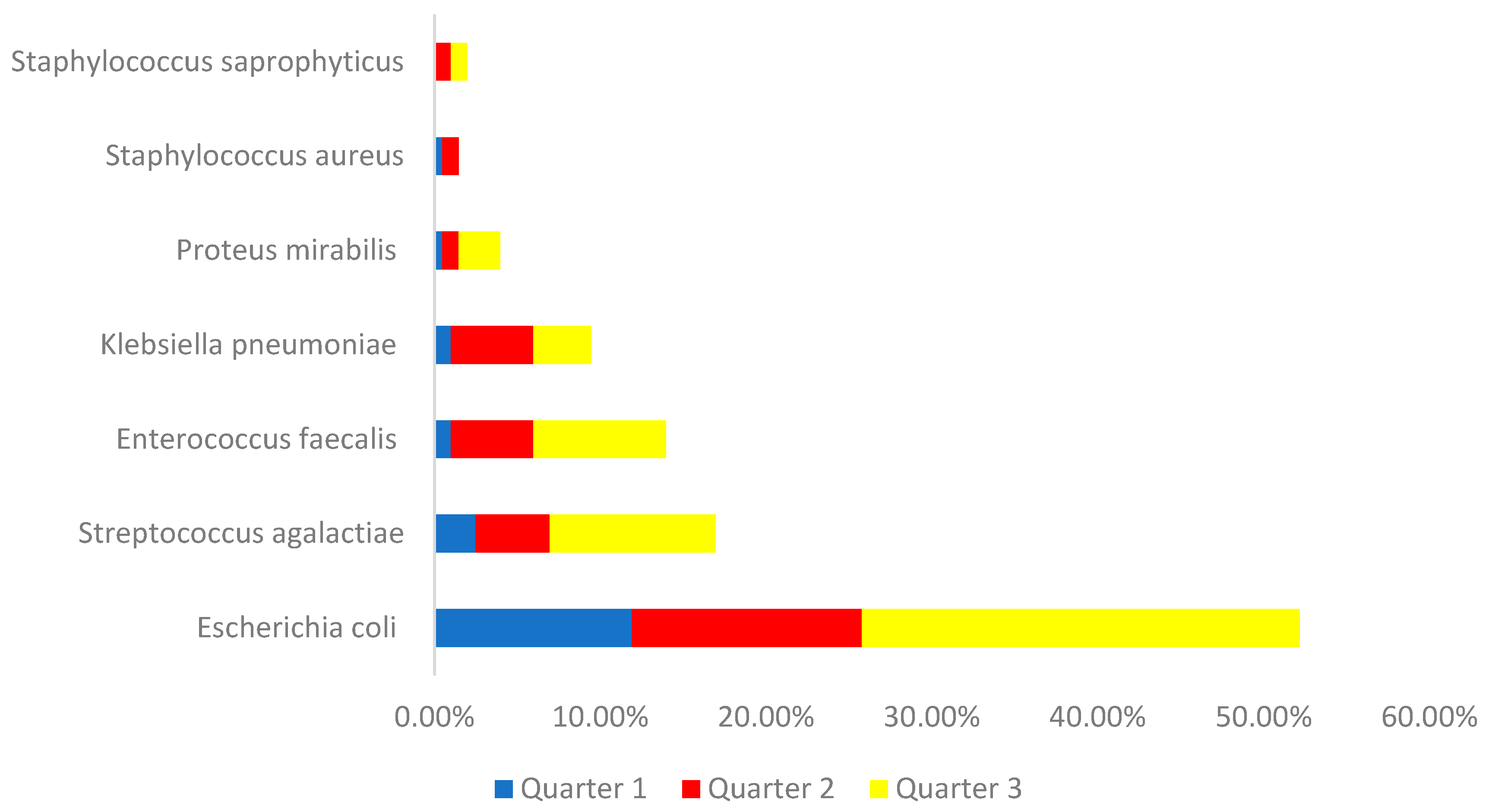

Regarding the strains identified, we found that 52.4% of urine cultures showed Escherichia coli, 16.9% Streptococcus agalactiae, 13.9% Enterococcus faecalis, 9.5% Klebisella pneumoniae, 3.9% Proteus mirabilis, 1.9 % Staphylococcus saprophyticus and 1.5% Staphylococcus aureus. Analyzing by quarter, we can see what is shown in graph 3.

Graph 3.

Distribution of the sample by identified bacteria and quarter of pregnancy.

Graph 3.

Distribution of the sample by identified bacteria and quarter of pregnancy.

Analyzing the interaction of the two most isolated bacteria in relation to the antibiotics tested in the last year analyzed (2022), particularly in relation to resistant strains, what appears in table 1:

Table 1.

Resistance of Escherichia coli and Streptococcus agalactie to antibiotics in 2022.

Table 1.

Resistance of Escherichia coli and Streptococcus agalactie to antibiotics in 2022.

| |

Escherichia coli |

Streptococcus agalactiae |

| Amoxicilina/Ácido Clavulânico |

32,6% |

|

| Cefuroxima Axetil |

18,2% |

|

| Ceftazidima/Avibactam |

7,2% |

|

| Nitrofurantoína |

24,4% |

|

| Trimetoprim/Sulfametoxazol |

26,7% |

0,0% |

| Ertapenem |

0,0% |

0,0% |

| Benzilpenicilina |

|

0,0% |

| Meticilina |

|

6,9% |

| Clotrimazol |

|

0,0% |

| Vancomicina |

|

67,4% |

| Imipenen |

|

41,1% |

4. Discussion

The work under analysis here included 201 urine cultures from pregnant women who were admitted over a period of four years to a Hospital in the Center of the Country. We observed that the average age of the individuals is 32.3 years, higher than the values indicated according to PorData for the first pregnancy in Portuguese women, which is 30.8 years for the first child (PorData, 2022)(15). There is, however, no way with the data studied to understand whether women are pregnant with their first child or not, but by comparing only the average age value obtained in the study we can say that there will be several in the process of second and/or third pregnancies.

Urinary infections represent a very important type of pathology in pregnant women, as structural and hormonal changes contribute to an increased risk (16).

The need for pregnant women to be screened for the possibility of having a urinary tract infection is highly valued and highlighted by scientific literature, whether older or more recent, as there are several reports of asymptomatic infections. In these cases, the pregnant woman does not have characteristic symptoms that would lead her to seek medical support, however the existence of asymptomatic bacteriuria can carry the same risks as a symptomatic urinary infection (17,18). Even asymptomatic bacteriuria should be treated in the same way as a symptomatic urinary infection, as the consequences can be exactly the same (19).

Only one woman was bandaged and came from hospitalization. This pregnant woman's urine culture was identified with Proteus mirabilis, clearly a bacterium closely associated with gallstone processes due to its physiological characteristics, particularly due to its ability to adhere to surfaces (20).

A very positive highlight is the fact that the vast majority of pregnant women come from External Consultation, which reveals great continuous monitoring by the Health Institution, thus avoiding the need to resort to the emergency service, which only had a prevalence of 5 98%, 91.8% of these pregnant women are in the third trimester of pregnancy.

The majority of pregnant women were in the third trimester and there are studies that show that the existence of a urinary tract infection during this period of pregnancy is positively associated with the risk of pre-eclampsia (21). It is also important to highlight that 17.4% of pregnant women were in the first trimester when they were diagnosed with a urinary tract infection, and the literature also shows that urinary infections during this period contribute to an increased risk of pre-eclampsia (22) . We thus see that, regardless of the moment of pregnancy, the need for these women to be closely monitored until the end of pregnancy is preponderant, considering the cross-sectional increase in risk.

Evaluating the strains most identified in positive urine cultures from pregnant women, we found that Escherichia coli was the most prevalent, as is the case in almost all similar studies. In second place is Streptococcus agalactiae, and in third place is Enterococcus facecalis, with Klebsiella only in fourth place. Klebsiella pneumoniae is usually the second most identified strain in this type of population (23). A note for a 2022 study carried out on pregnant women, in which Streptococcus agalactiae appears as the most prevalent bacteria, followed by Escherichia coli (24).

Considering the difficulties in treating urinary infections in pregnant women, attempts have been made to determine guidelines, in the sense that their implementation can contribute, in a clear and operational way, to the treatment of the pathology, with the minimum possible negative impact, whether on the mother and baby, as possible complications are very well documented and include everything from premature birth to situations of high severity and risk of death (25). The duration of treatment should always be minimized as much as possible, without jeopardizing its effectiveness (26). The use of antibiotics during pregnancy can be associated with short or long-term effects, both on newborns and women, and should therefore always be considered carefully. In general, studies show safety in the use of vancomycin, beta lactams, nitrofurantoin, metronidazole, clindamycin and phosphomycin, with tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones being avoided (27). It should also be noted that the antibiogram provided by the laboratory is general, and the prescription must then be adapted by the specialist, considering the pregnant woman's conditions, and some of the drugs may not be eligible for the pregnant woman's clinical situation.

All strains of Escherichia coli are sensitive to just one antibiotic – Ertapenem, and for the remaining five tested, values range from 7.2% resistance to Ceftazidime/Avibactam and 32.6% to Amoxicillin/Clavulanic Acid. Ceftazidime/Avibactam has been shown to be an antibiotic with low resistance values (less than 5%) in several similar studies, including in complicated urinary infections (28, 29). With regard to Amoxicillin/Clavulanic Acid, a progressive increase in resistance has been observed, as demonstrated in a 2021 study, where the sensitivity values of Escherichia coli in 2005 were 90%, falling to less than 45% in the year 2017 (30). In a study carried out in Croatia, the increase in resistance to Amoxicillin/Clavulanic Acid by Escherichia coli is associated with the massive use of this antibiotic, with its use even being restricted, as a way of contributing to the reduction of resistance (31).

Ertapenem, a cabapenem that shares the basis of action with Imipenem and Meropenem, has been shown to be less effective with non-fermenting bacteria (32). It proved to be an antibiotic that can be very useful, since no strain of Escherichia coli and Streptococcus agalactiae was resistant in the year 2022. Indeed, it is an antibiotic that has performed well, showing low resistance values (33).

Streptococcus agalactiae strains were completely sensitive to four antibiotics, with the most worrying values of resistance associated with Vancomycin, in which more than 67% of the strains are resistant, a very high value compared to other similar studies, which present much lower values (34). On the other hand, no strain of Streptococcus agalactiae showed resistance to Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole, a result contrary to other studies, with resistance levels greater than 50% (35). Although all strains of Streptococcus agalactiae are sensitive to Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole, this antibiotic should be avoided, particularly during the first trimester of pregnancy, due to the risk of the “antifolate” effect, associated with the neuronal tube (36).

5. Conclusions

By carrying out this study, it was possible to observe that the majority of pregnant women were in the third trimester of pregnancy and had come from the External Consultation. The two most isolated strains were Escherichia coli and Streptococcus agalactiae. Regarding the interaction with the antibiotics tested in 2022, it is observed that all strains of Escherichia coli are susceptible to Ertapenem, while all strains of Streprococcus agalactiae are susceptible to four antibiotics - Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole, Ertapenem, Benzylpenicillin and Clotrimazole. This study thus allows us to better understand both the overview of the main strains that contribute to urinary infections in pregnant women and their spectrum of interaction with antibiotics

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Francisco Rodrigues and Miguel Castelo Branco; methodology, Francisco Rodrigues; software, Patrícia Coelho; validation, Francisco Rodrigues, Patrícia Coelho, Miguel Castelo Branco; formal analysis, Miguel Castelo Branco; investigation, Francisco Rodrigues; data curation, Patrícia Coelho; writing - preparation of the original draft, Francisco Rodrigues; writing - review and editing, Miguel Castelo Branco; visualization, Patrícia Coelho; supervision, Miguel Castelo Branco; project coordination, Francisco Rodrigues. All authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This work was approved by the Ethics Committee and the Data Protection Officer of the University of Beira Interior, and all ethical precepts were scrupulously respected by the Researchers. Informed consent was waived given the retrospective nature and the fact that no user identifying data was used.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, L.; Foxman, B. . Molecular epidemiology of Escherichia coli mediated urinary tract infections. Frontiers in bioscience: a journal and virtual library. 2003, 8, e235–e244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, M.; Vehreschild, M.J.G.T.; Wagenlehner, F. Management of uncomplicated recurrent urinary tract infections. BJU international. 2022, 129, 668–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litza, J.A.; Brill, J.R. Urinary tract infections. Primary care. 2010, 37, 491–viii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korzeniowski, O.M. Urinary tract infection in the impaired host. The Medical clinics of North America. 1991, 75, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salh, K.K. Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacteria Causing Urinary Tract Infections. Combinatorial chemistry & high throughput screening. 2022, 25, 1219–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojno, K.J.; Baunoch, D.; Luke, N.; Opel, M.; Korman, H.; Kelly, C.; Jafri SM, A.; Keating, P.; Hazelton, D.; Hindu, S.; Makhloouf, B.; Wenzler, D.; Sabry, M.; Burks, F.; Penaranda, M.; Smith, D.E.; Korman, A.; Sirls, L. . Multiplex PCR Based Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) Analysis Compared to Traditional Urine Culture in Identifying Significant Pathogens in Symptomatic Patients. Urology. 2020, 136, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.W.; Culbreath, K.D.; Mehrotra, A.; Gilligan, P.H. Reflect urine culture cancellation in the emergency department. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2014, 46, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalinderi, K.; Delkos, D.; Kalinderis, M.; Athanasiadis, A.; Kalogiannidis, I. Urinary tract infection during pregnancy: current concepts on a common multifaceted problem. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology: the journal of the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2018, 38, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietropaolo, A. Urinary Tract Infections: Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Journal of clinical medicine. 2023, 12, 5058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnarr, J.; Smaill, F. Asymptomatic bacteriuria and symptomatic urinary tract infections in pregnancy. European journal of clinical investigation. 2008, 38 Suppl 2, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, A.P.; Schaeffer, A.J. Urinary Tract Infection and Bacteriuria in Pregnancy. The Urologic clinics of North America. 2015, 42, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macejko, A.M.; Schaeffer, A.J. Asymptomatic bacteriuria and symptomatic urinary tract infections during pregnancy. The Urologic clinics of North America. 2007, 34, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales, M.; Corrales-Acosta, E.; Corrales-Riveros, J.G. Which Antibiotic for Urinary Tract Infections in Pregnancy? A Literature Review of International Guidelines. Journal of clinical medicine. 2022, 11, 7226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovalle, A.; Levancini, M. Urinary tract infections in pregnancy. Current opinion in urology. 2001, 11, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/portugal/idade+media+da+mae+ao+nascimento+do+primeiro+filho-805.

- Ansaldi, Y.; Martinez de Tejada Weber, B. Urinary tract infections in pregnancy. Clinical microbiology and infection: the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2023, 29, 1249–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fede, T.; Valente, S.; Bertasi, M. Evaluation of a prospective study on the urinary tract infections in pregnancy. Clinical and experimental obstetrics & gynecology. 1983, 10, 131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Sgayer, I.; Shamalov, G.; Assi, S.; Glikman, D.; Lowenstein, L.; Frank Wolf, M. Bacteriology and clinical outcomes of urine mixed bacterial growth in pregnancy. International urogynecology journal Advance online publication. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaill, F.M.; Vazquez, J.C. Antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2019, CD000490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbruster, C.E.; Mobley, H.L.T.; Pearson, M.M. Pathogenesis of Proteus mirabilis Infection. EcoSal Plus. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easter, S.R.; Cantonwine, D.E.; Zera, C.A.; Lim, K.H.; Parry, S.I.; McElrath, T.F. Urinary tract infection during pregnancy, angiogenic factor profiles, and risk of preeclampsia. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2016, 214, 387.e1–387e3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavi-Zahedkalaei, A.; Kazemi, M.; Zolfaghari, P.; Rashidan, M.; Sohrabi, M.B. Association Between Urinary Tract Infection in the First Trimester and Risk of Preeclampsia: A Case-Control Study. International journal of women's health. 2020, 12, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosana, Y.; Ocviyanti, D.; Halim, M.; Harlinda, F.Y.; Amran, R.; Akbar, W.; Billy, M.; Akhmad, S.R.P. Urinary Tract Infections among Indonesian Pregnant Women and Its Susceptibility Pattern. Infectious diseases in obstetrics and gynecology. 2020, 9681632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandran, L.; Jacob, L.; Al Awadhi, R.; Yahya, L.O.; Catroon, K.M.; Soundararajan, L.P.; Wani, S.; Alabadla, S.; Hussein, Y.A. Urinary Tract Infection in Pregnancy and Its Effects on Maternal and Perinatal Outcome: A Retrospective Study. Cureus. 2022, 14, e21500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina-Muñoz, J.S.; Cuadrado-Angulo, J.; Grillo-Ardila, C.F.; Angel-Müller, E.; Cortés, J.A.; Leal-Castro, A.L.; Vallejo-Ortega, M.T. Consensus for the treatment of upper urinary tract infections during pregnancy. Consenso para el tratamiento de la infección de vías urinarias altas durante la gestación. Revista colombiana de obstetricia y ginecología. 2023, 74, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajkowski, K.; Broś-Konopielko, M.; Teliga-Czajkowska, J. Urinary tract infection in women. Przeglad menopauzalny = Menopause review. 2021, 20, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bookstaver, P.B.; Bland, C.M.; Griffin, B.; Stover, K.R.; Eiland, L.S.; McLaughlin, M. A Review of Antibiotic Use in Pregnancy. Pharmacotherapy. 2015, 35, 1052–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, B.D.; Thuras, P.; Porter, S.B.; Clabots, C.; Johnsona, J.R. Activity of cefiderocol, ceftazidime-avibactam, and eravacycline against extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli clinical isolates (2012-20017) in relation to phylogenetic background, sequence type 131 subclones, blaCTX-M genotype, and coresistance. Diagnostic microbiology and infectious disease. 2021, 100, 115314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, A.; Welch, E.; Hunter, A.; Trautner, B.W. Antimicrobial Treatment Options for Difficult-to-Treat Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria Causing Cystitis, Pyelonephritis, and Prostatitis: A Narrative Review. Drugs. 2022, 82, 407–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanstokstraeten, R.; Belasri, N.; Demuyser, T.; Crombé, F.; Barbé, K.; Piérard, D. A comparison of E. coli susceptibility for amoxicillin/clavulanic acid according to EUCAST and CLSI guidelines. European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases : official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology. 2021, 40, 2371–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimica Matanovic, S.; Bergman, U.; Vukovic, D.; Wettermark, B.; Vlahovic-Palcevski, V. Impact of restricted amoxicillin/clavulanic acid use on Escherichia coli resistance--antibiotic DU90% profiles with bacterial resistance rates: a visual presentation. International journal of antimicrobial agents. 2010, 36, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livermore, D.M.; Sefton, A.M.; Scott, G.M. Properties and potential of ertapenem. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2003, 52, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wald-Dickler, N.; Lee, T.C.; Tangpraphaphorn, S.; Butler-Wu, S.M.; Wang, N.; Degener, T.; Kan, C.; Phillips, M.C.; Cho, E.; Canamar, C.; Holtom, P.; Spellberg, B. Fosfomycin vs Ertapenem for Outpatient Treatment of Complicated Urinary Tract Infections: A Multicenter, Retrospective Cohort Study. Open forum infectious diseases. 2021, 9, ofab620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigvava, S.; Kharebava, S.; Giorgobiani, T.; Dvalidze, T.; Goderdzishvili, M. IDENTIFICATION AND ANTIBIOTIC SUSCEPTIBILITY PATTERNS OF STREPTOCOCCUS AGALACTIAE. Georgian medical news. 2019, (297), 149–153. [Google Scholar]

- Akpaka, P.E.; Henry, K.; Thompson, R.; Unakal, C. Colonization of Streptococcus agalactiae among pregnant patients in Trinidad and Tobago. IJID regions. 2022, 3, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Bozzo, P.; Einarson, A.; Koren, G. Urinary tract infections in pregnancy. Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien. 2008, 54, 853–854. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).