1. Introduction

Three-dimensional (3D) (bio)printing is a cutting-edge technology for the precise deposition of (bio)materials onto specified locations with a high resolution. This process involves fabricating objects layer-by-layer using a printer head, nozzle, or similar technology [

1]. The convergence of additive manufacturing with biomaterials has introduced new paradigms in the field of biotechnology. The emergence of new printing materials and various 3D printers that integrate sensing layers with complex scaffold geometries has opened new avenues for biosensor development [

2,

3]. 3D bioprinting now extends to critical applications, including embedding active biomolecular recognition elements into 3D printed objects for (bio)sensing [

2,

3,

4,

5], applications in tissue engineering [

6], wound healing [

6], and the production of various medical implants and models [

7]. The major challenges commonly encountered during printing processes when working with bio-based hydrogels are structural collapse and loss of shape fidelity, depending on the viscoelastic property of the printing material [

8]. Rapidly solidifying ‘inks’ are desirable for printing to prevent the deformation of the printed structure. An ideal hydrogel ink should flow through a nozzle during printing and retain its shape after printing and curing; this requires custom materials with tailored properties to be formulated for each application. Therefore, many hydrogels with varying viscosities have been adapted for 3D printing via microextrusion [

9].

Hydrogels, particularly those derived from natural polymers, such as alginate, gelatin, and chitosan, are widely utilized in bioprinting because of their biocompatibility and ability in an aqueous environment, which is essential for cell viability and growth [

10,

11]. Hydrogels are hydrophilic 3D polymeric networks with a high degree of flexibility and ability to absorb and retain large amounts of aqueous liquids while retaining mechanical stability [

1,

12,

13]. Physical hydrogels have several advantages, such as easy preparation and sol-gel transition [

13,

14]. However, such hydrogels often exhibit mechanical weaknesses in terms of gelation and printability, which limits their application in additive manufacturing processes. Therefore, significant efforts have been directed toward enhancing the mechanical properties of hydrogels, thereby improving their printability and functionality in tissue engineering. For instance, using a composite approach, alginate-gelatin composite bioinks, together with the incorporation of nanoparticles, have significantly improved mechanical strength, enhancing printability and cellular support in tissue engineering applications [

15].

There are numerous challenges associated with working with conventional hydrogels, such as dynamic rheological behavior under different printing conditions, which leads to a loss of printing fidelity and structural integrity post-printing [

16,

17]. To address such challenges, efforts such as the use of composite polymers and blending of inorganic nanoparticles with biopolymers are being made for structural and functional enhancement. In addition, the use of sacrificial copolymers and printing into sacrificial support baths, whereby the sacrificial copolymer and support bath are removed after printing, is being actively investigated[

18,

19]. Furthermore, tissue engineering applications that cultivate electrically excitable cells (such as cardiomyocytes, neurons, and myocytes) would benefit from improved cell adhesion, cell-cell communication, proliferation, and differentiation when the hydrogel is made conductive [

20,

21]. However, a critical research question remains to be answered: how can we engineer a hydrogel that retains the biocompatibility, printability, and rheological properties of alginate while enhancing its electrical conductivity properties?

Research on conductive hydrogels is advancing because of their potential applications in various fields including bioelectronics, drug delivery systems, tissue engineering, and biosensors [

3]. Despite these advances, current hydrogel-based bioinks fail to fully support the cultivation and electrical stimulation of electrically excitable cells, such as neurons and cardiomyocytes, owing to insufficient electrical conductivity. This need limits the potential of 3D bioprinted tissues to mimic the native electroactive tissues. Therefore, continuous research efforts are directed towards incorporating conductive materials into hydrogel bioinks by doping the hydrogel with intrinsically conductive materials (ICMs), such as polypyrrole, poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene): poly(styrene sulfonate) (PEDOT: PSS) [

22,

23], graphene oxide [

24], polythiophene, and nanoparticles. While the incorporation of ICMs into hydrogels has been explored and shown to enhance the electrical properties while maintaining the unique characteristics of the hydrogels, such as flexibility and biocompatibility [

24], conductive hydrogels prepared via doping ICMs are presented with a significant setback: uncontrolled leaching of the conductive unit from the hydrogel due to the non-covalent nature of the incorporation [

25]. Thus, we hypothesized that covalently binding the intrinsically conductive unit to the alginate polymer could lead to a stable 3D printable electrically conductive hydrogel.

Sodium alginate is an ideal biopolymer candidate because of its excellent biocompatibility, non-toxicity, and ability to rapidly form 3D hydrogels upon interaction with divalent cations [

26]. Furthermore, its thixotropic properties, including its shear-thinning behavior and viscosity recovery [

27], make it particularly suitable for 3D printing applications, either as a standalone material or in combination with other polymers.

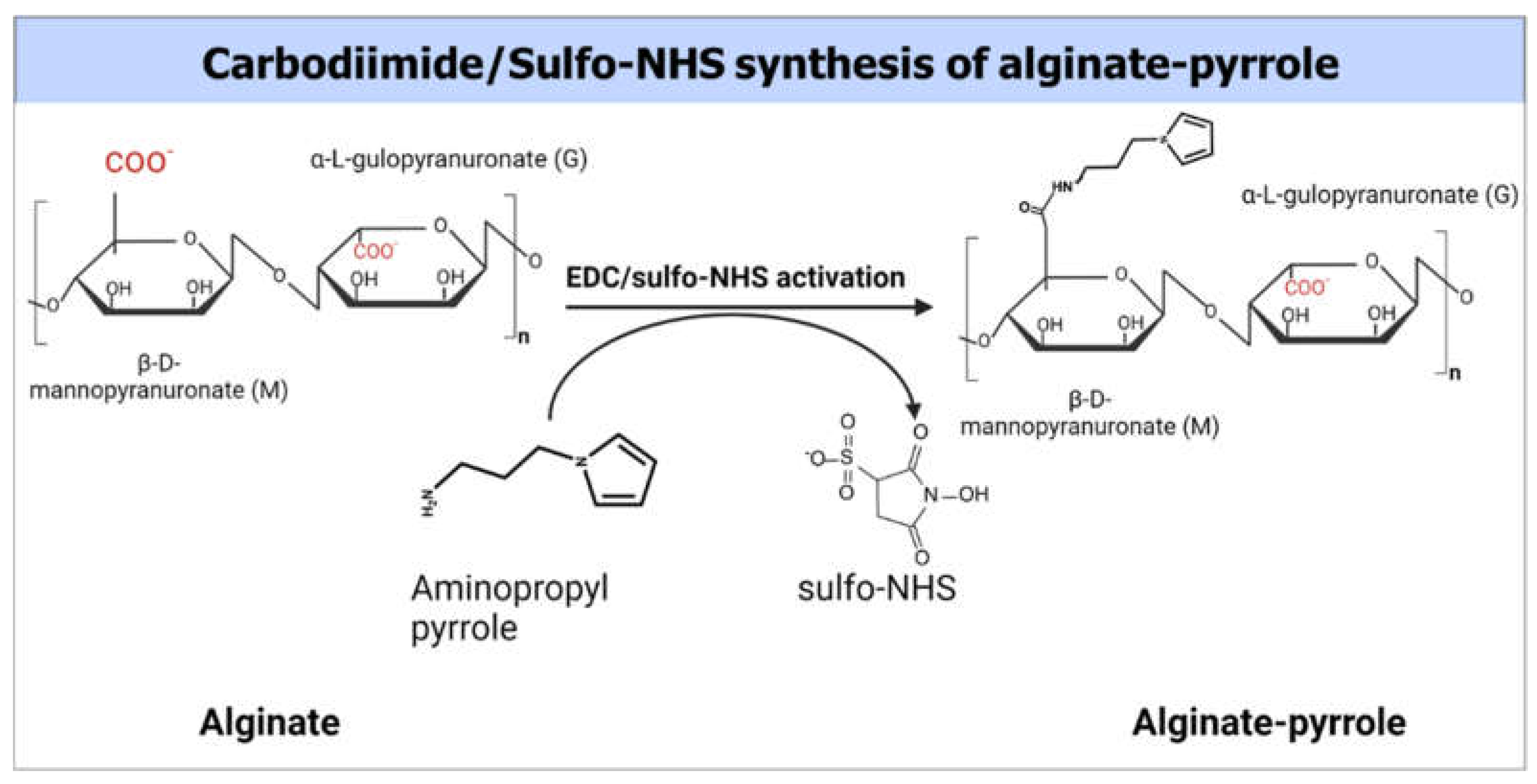

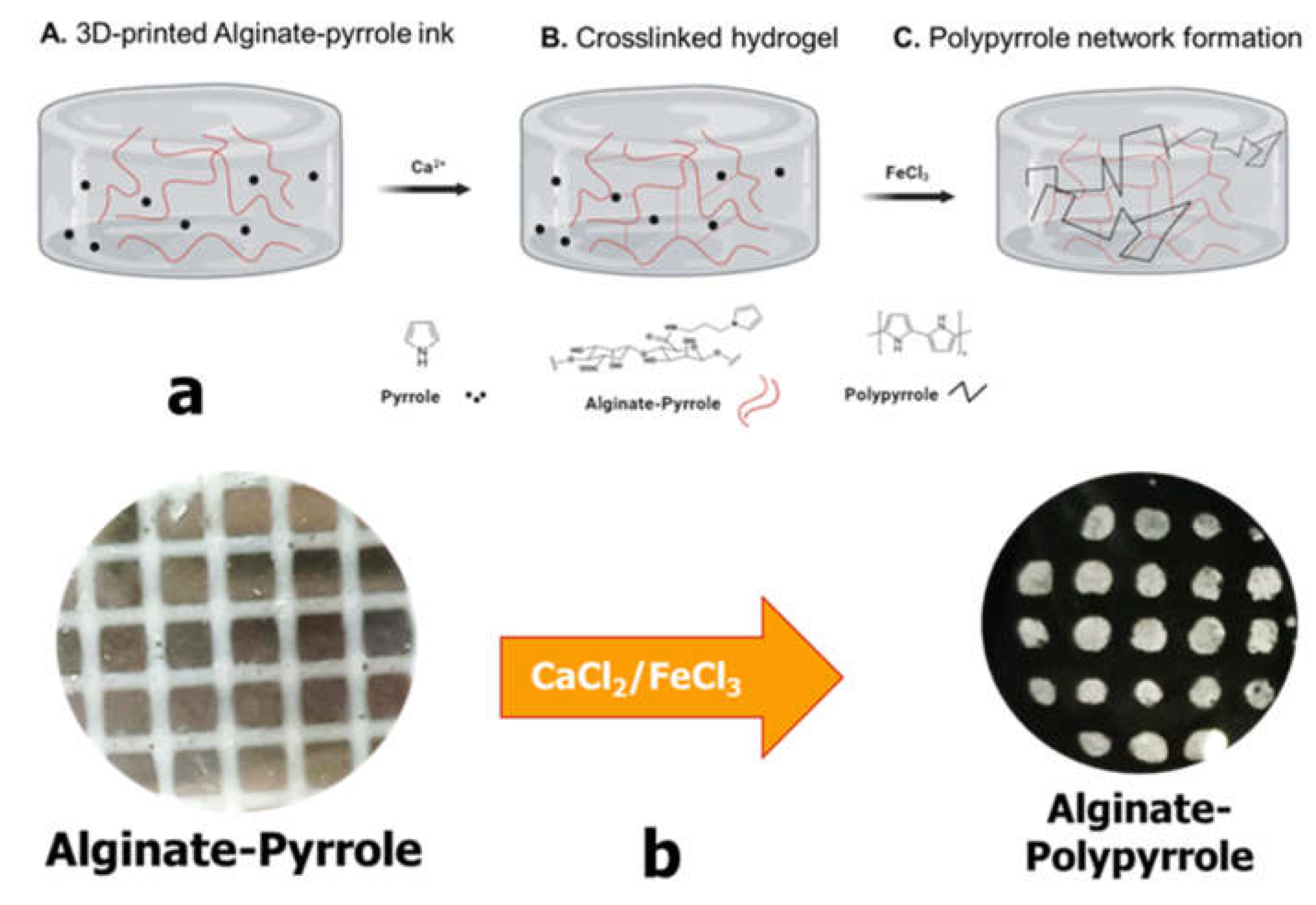

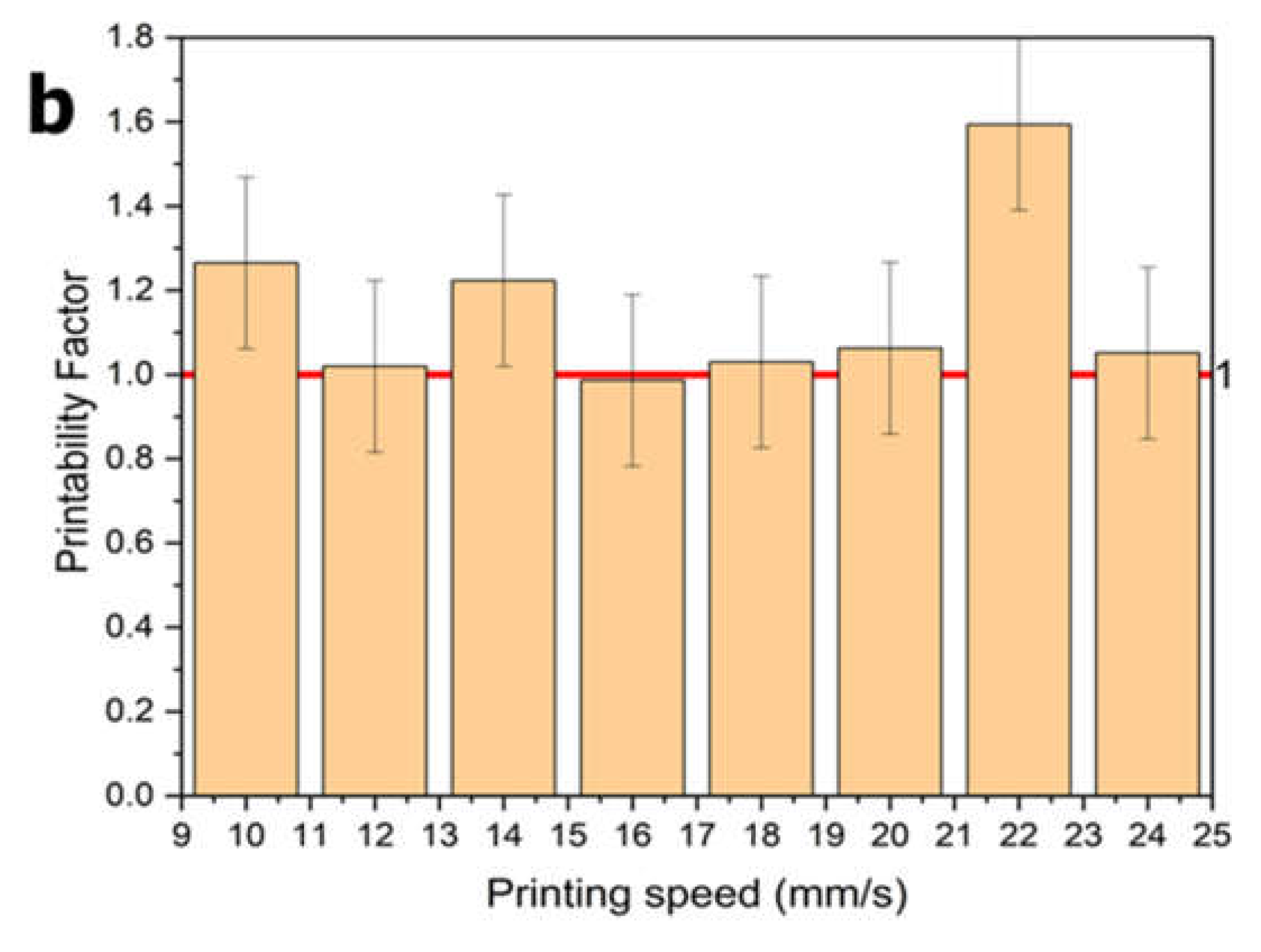

Despite their documented advantages, alginate hydrogels, like other biopolymer-based hydrogels, lack sufficient electrical conductivity, limiting their widespread application in bioelectronics, biosensors, and electroactive tissue scaffolds. Thus, we propose the integration of polypyrrole into alginate hydrogels to confer electrical properties to alginate while maintaining its rheological features, making it amenable to 3D bioprinting. This study introduces a new approach for creating an electrically conductive alginate-based composite hydrogel by covalently binding sodium alginate to a pyrrole monomer, from which conductive polypyrrole is chemically synthesized either in situ or ex situ. Specifically, an N-substituted pyrrole derivative, aminopropyl pyrrole, was synthesized and conjugated with alginate using carbodiimide chemistry. The resulting alginate-pyrrole conjugate was characterized by its rheological properties, electrical conductivity, and 3D printability.

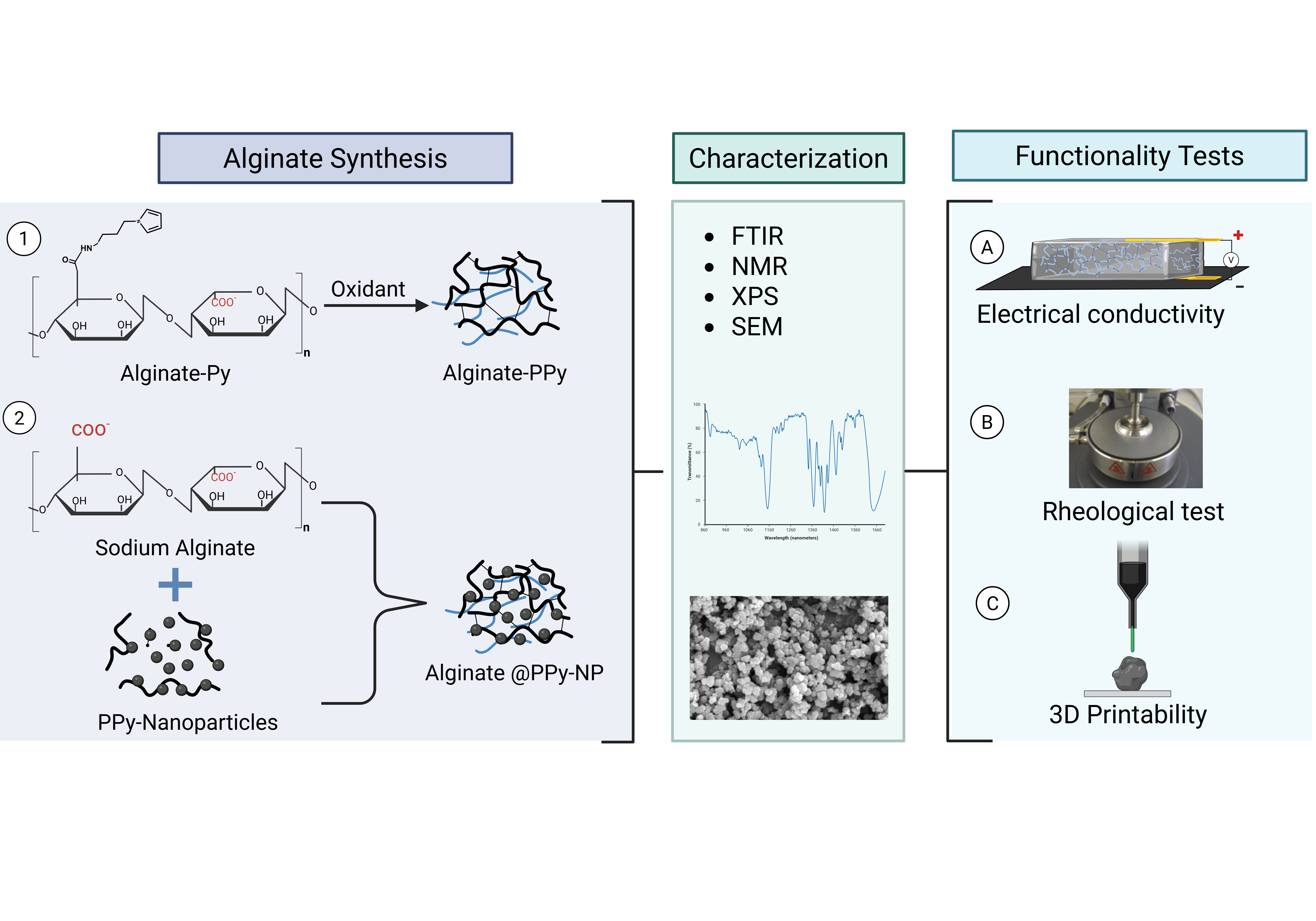

Wright et al. showed the printability of alginate mixed with pyrrole monomer, which was subsequently polymerized into polypyrrole, and reported uncontrolled leaching of polypyrrole and the brittleness of the resulting hydrogel [

25]. Therefore, two strategies were explored in this study to incorporate polypyrrole into the alginate matrix: (1) oxidative polymerization of pyrrole directly within the 3D printed alginate-pyrrole network (

in situ polymerization), referred to as alginate-PPy, and (2) pre-synthesis of polypyrrole nanoparticles (PPy-NP), which were subsequently blended with alginate (as alginate@PPy-NP) prior to 3D printing. This is the first time that this approach has been employed to create an alginate-polypyrrole-based conductive hydrogel. The effects of these strategies on the printability, mechanical integrity, and electrical properties of hydrogels were examined. Notably, the electrical conductivity increased with pyrrole content in both cases, and both types of alginate-polypyrrole were 3D printable, while alginate mixed with already-made polypyrrole nanoparticles displayed appreciably higher compressibility, without leaching out of the ICMs, highlighting the potential of this covalently functionalized alginate as an electrically conductive bio-ink.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

1-(2-cyanoethyl)-pyrrole, ether, LiAlH4, low-viscosity sodium alginate (A2158-250G), 1-ethyl-[3-(dimethyl amino)propyl]-3-ethyl carbodiimide HCl (EDAC; E-1769), 2-[N-morpholino] ethane sulfonic acid (MES) buffer (M-8250), ammonium persulfate, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (P-3813), calcium chloride (C-5426), and N-hydroxysulfo-succinimide (NHSS; 24510) were of analytical grade.

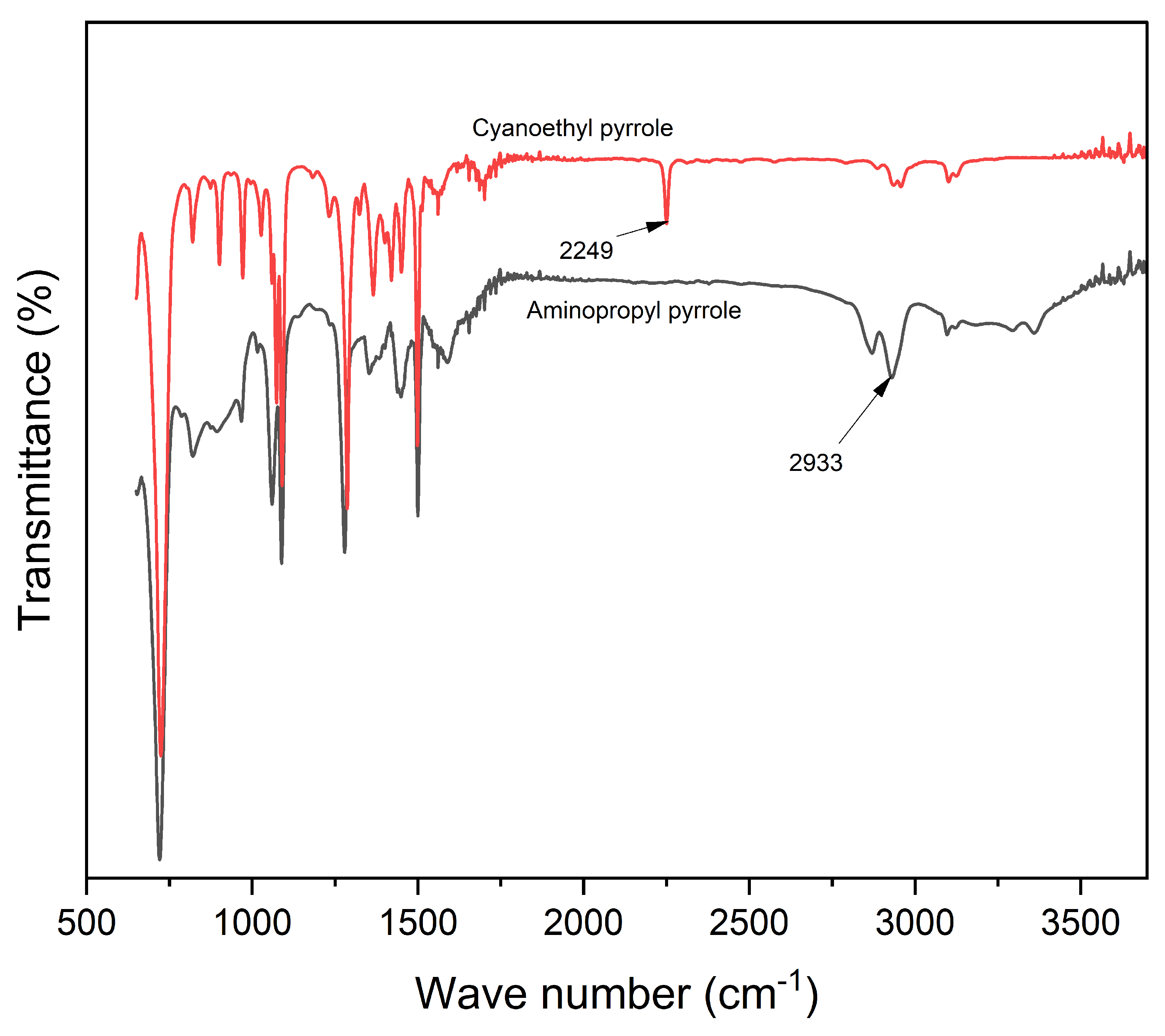

2.2. Synthesis of Aminopropyl Pyrrole

A solution of 1-(2-cyanoethyl) pyrrole (0.02 mol) was added dropwise to anhydrous ether (15 mL) in a suspension of LiAlH

4 (0.05 mol), prepared in anhydrous ether (150 mL), refluxed for 10 h, and cooled. The excess hydride was quenched by successive addition of water (1.7 mL), a solution of 15% (w/v) NaOH (1.7 mL), and water (5.1 mL), and then heated at 40 °C for two h. The resulting solution was filtered through celite and the filtrate was evaporated to dryness. The synthesis of N-(3-aminopropyl)-pyrrole was confirmed by ¹H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl₃) δ: 6.70 (s, 2H, H–α), 6.24 (s, 2H, H–β), 3.25 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H, –CH₂–NH₂), 2.65 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, –CH₂–CH₂–NH₂), 1.85 (m, 2H, –CH₂–CH₂–CH₂–) (supplementary section

Figure S1), FTIR (

Figure 2), and mass (supplementary section,

Figure S2) spectroscopies.

Figure 1.

Covalent conjugation of pyrrole monomers to sodium alginate

Figure 1.

Covalent conjugation of pyrrole monomers to sodium alginate

2.3. Synthesis of Alginate-Pyrrole

An alginate solution (2.5% w/v) was prepared by dissolving 500 mg of alginate in 20 ml of double-distilled water (DDW) with a resistivity of 18.2 MΩ and sterile filtered through a 0.22 µm filter (Stericup and Steritop EMD Millipore Corp., Billerica, USA). To the filtered alginate solution, 852 mg MES buffer and 400 mg NaCl were added and stirred well, and the pH was adjusted to 6.5. Next, the carboxyl groups of the alginate were activated using 1 mmol of EDAC and 0.5 mmol NHSS as a co-reactant (the calculation was for the ratios of reagents that would produce a theoretical 50% molar modification of the number of carboxylic groups of alginates) and stirred for 3 h at room temperature. mmol) of N-(3-aminopropyl) pyrrole (480 mg, 3 mmol) were added to a solution of activated alginate and stirred overnight at room temperature (

Figure 1). The resulting polymer composite was dialyzed against doubly distilled water using a 3.5 kDa MWCO membrane (Spectrum Lab Membrane Filtration Products, Inc., TX, U.S.A.), with the water changed twice a day for 3 days. The dialysate was then lyophilized. The extent of pyrrole incorporation was determined by UV-vis spectroscopy using a pedestal function of NanoDrop ONE

C desktop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). Briefly, the extent of alginate modification by

N-(3-aminopropyl)-pyrrole was determined by dissolving the pyrrole-alginate samples to produce a 0.01% (w/v) pyrrole-alginate solution and measuring the absorbance. The extent of alginate modification was determined from the calibration curve by measuring the absorbance of different amounts of

N-(3-aminopropyl)-pyrrole in 0.01% (w/v) alginate solution. A standard solution of alginate at a concentration of 0.01% (w/v) was used as blank (

Supplementary Figure S5).

2.4. Attenuated Total Reflection Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR).

Infrared spectra of the synthesized aminopropyl pyrrole and alginate-pyrrole were recorded using a Smart iTR™ Diamond ATR-FTIR sampling accessory and Nicolet 6700 spectrometer to characterize the functional groups of the synthetic products. All measurements were performed using a built-in diamond-attenuated total-reflection (ATR) crystal. The FTIR spectra were acquired over the range of 4000–650 cm−1 at a resolution of 4 cm−1 and represented an average of 36 scans. The spectrum of the clean, dry diamond ATR crystal in ambient atmosphere (air) was used as the background for the infrared measurements.

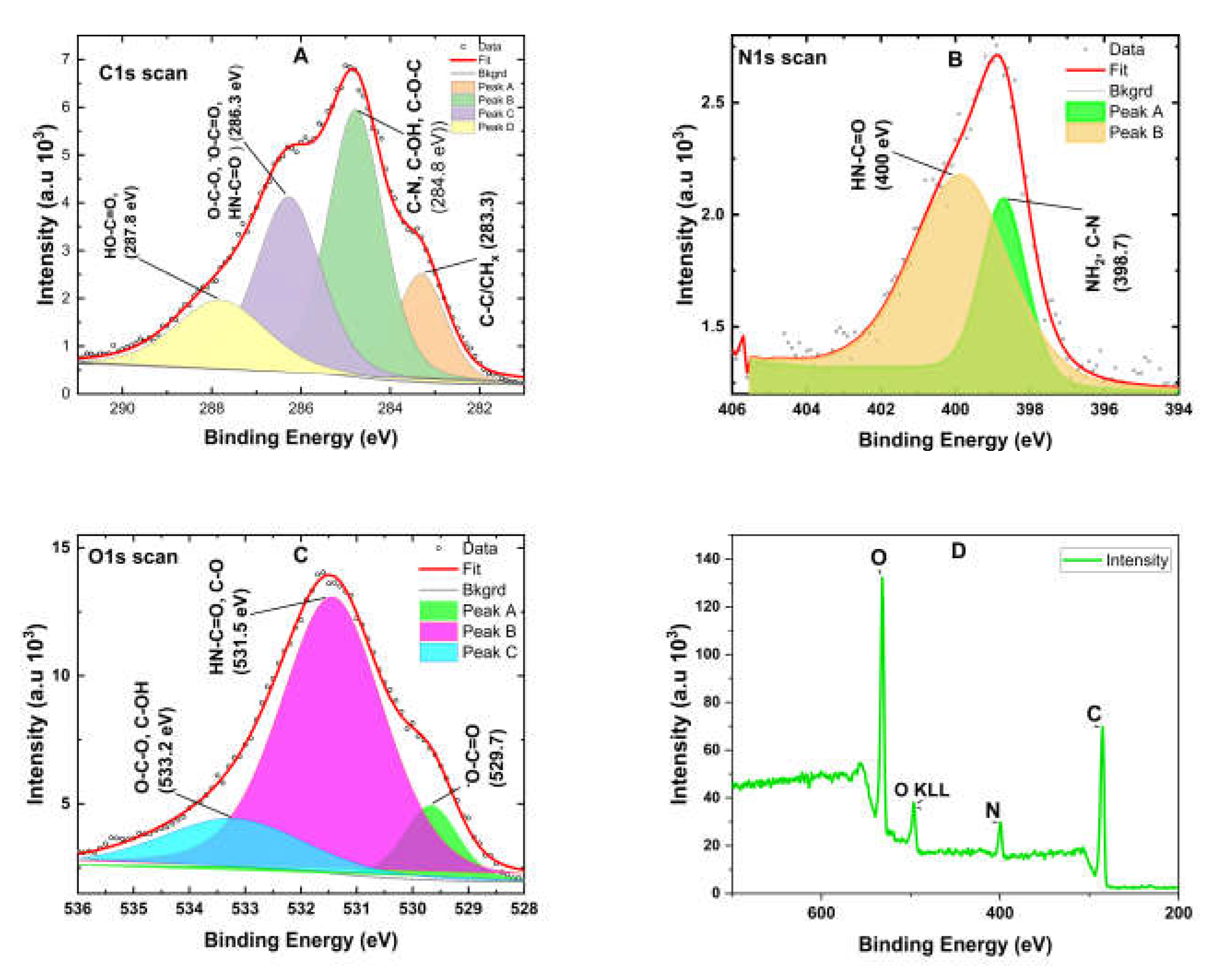

2.5. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) Analysis

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was conducted on lyophilized samples of alginate-pyrrole and alginate using an “ESCALAB Xi+” instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The ionization energies of oxygen, nitrogen, and carbon present in the lyophilized samples were recorded as previously described for alginate [

28]. The analysis was performed at an ambient pressure < 1 × 10

-10 mbar. An aluminum Kα radiation source (1486.68 eV) was used for photoelectron emission at room temperature, and spectra were collected at an angle of 90° from the X-ray source. A low-energy electron flood gun was employed to minimize surface charging and measurements were performed with a spot diameter of 650 µm. Spectral analysis was performed using the Avantage software version 6.6.0, provided by Thermo Fisher Scientific). High-resolution spectra of the C1s, O1s, and N1s peaks and a survey spectrum at a pass energy of 20 eV were obtained.

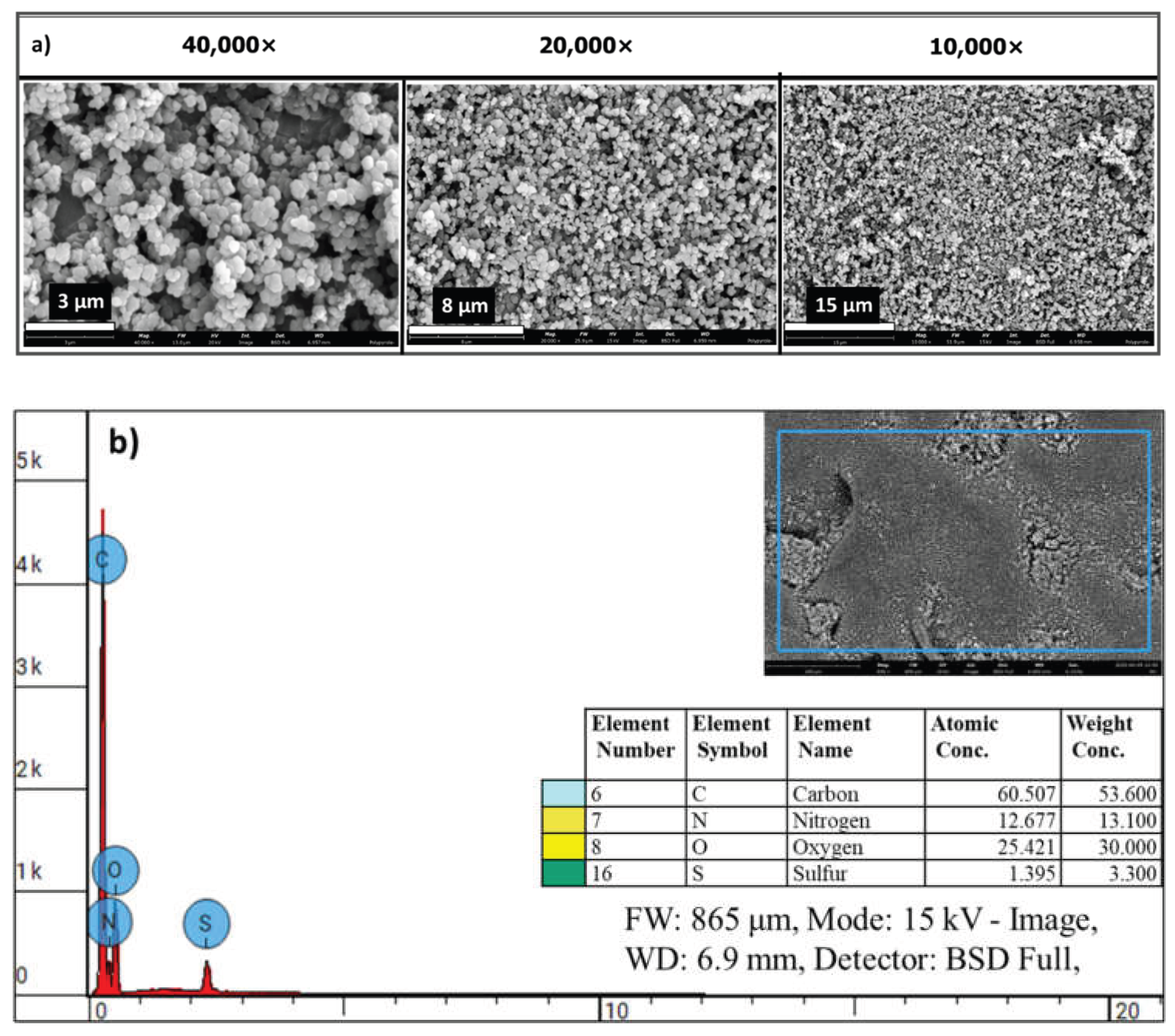

2.6. Chemical Synthesis of Polypyrrole Nanoparticles (PPy-NP)

Polypyrrole (PPy) was synthesized via chemical oxidative polymerization using ammonium persulfate (APS) as the oxidant with a monomer-to-oxidant molar ratio of 1:1.5. The final APS concentration was 212 mM, and the reaction was conducted at 4 °C for 120 min. Briefly, 1.0 mL of pyrrole monomer (14.4 mmol) was added to 50 mL of ice-cold deionized water (DDW) under continuous stirring. Separately, 4.83 g APS (21.6 mmol) was dissolved in 10 mL DDW and added dropwise to the pyrrole solution. The total reaction volume was adjusted to 100 mL using DDW and the mixture was magnetically stirred. Aliquots of 5 mL were withdrawn at defined time intervals to monitor the polymerization progress via UV-Vis spectroscopy at 460 nm (

Supplementary Figure S4). Following polymerization, the black precipitate of PPy was collected by vacuum filtration, thoroughly washed with DDW and ethanol to remove residual monomers and oxidants, and dried under vacuum at 50 °C overnight. The surface morphology of the synthesized PPy was examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Samples were sputter-coated with gold and imaged at various magnifications to assess surface features and particle aggregation (

Figure 12).

2.7. Preparation of Alginate-Pyrrole as Bioink

2.7.1. Alginate-Pyrrole/Pyrrole (Alginate-Py) as Bioink

To create an optimal ink formulation, different stoichiometric ratios of pyrrole in alginate were prepared (

Table 1) using double-distilled water (DDW) with a resistivity of 18.2 MΩ. Lyophilized alginate-pyrrole and sodium alginate were separately dissolved in double-distilled water to a final concentration of 2.5% (w/v) under stirring for 2 h. Primary crosslinking of the alginate was achieved by mixing 1.2 ml of alginate-pyrrole, 1.2 ml of alginate, 0.3 ml of CaCl

2 (0.1 M), and 0.021 ml of pyrrole monomer (14.125 M), using a homogenizer to equally distribute the calcium ions throughout the solution (

Table 1). The mixture was then stirred at RT until further use. The partially crosslinked alginate-pyrrole/pyrrole was transferred to a sterile syringe.

For the cell-laden bioink, 0.28 ml of Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing 2.6 × 106 cells/ml of isolated GFP-expressing fibroblasts mixed with DMEM was loaded into an additional sterile syringe, which was immediately connected to the alginate-pyrrole/pyrrole-loaded syringe through a Luer-to-Luer connector. The solutions were mixed by gently pushing the pistons back and forth for 1 min until they were homogeneously mixed. The final bioink solution consisted of 2% alginate-pyrrole (w/v), 0.01 M CaCl2 (or 0.36% w/v calcium gluconate), and 2.6 × 106 cells/mL.

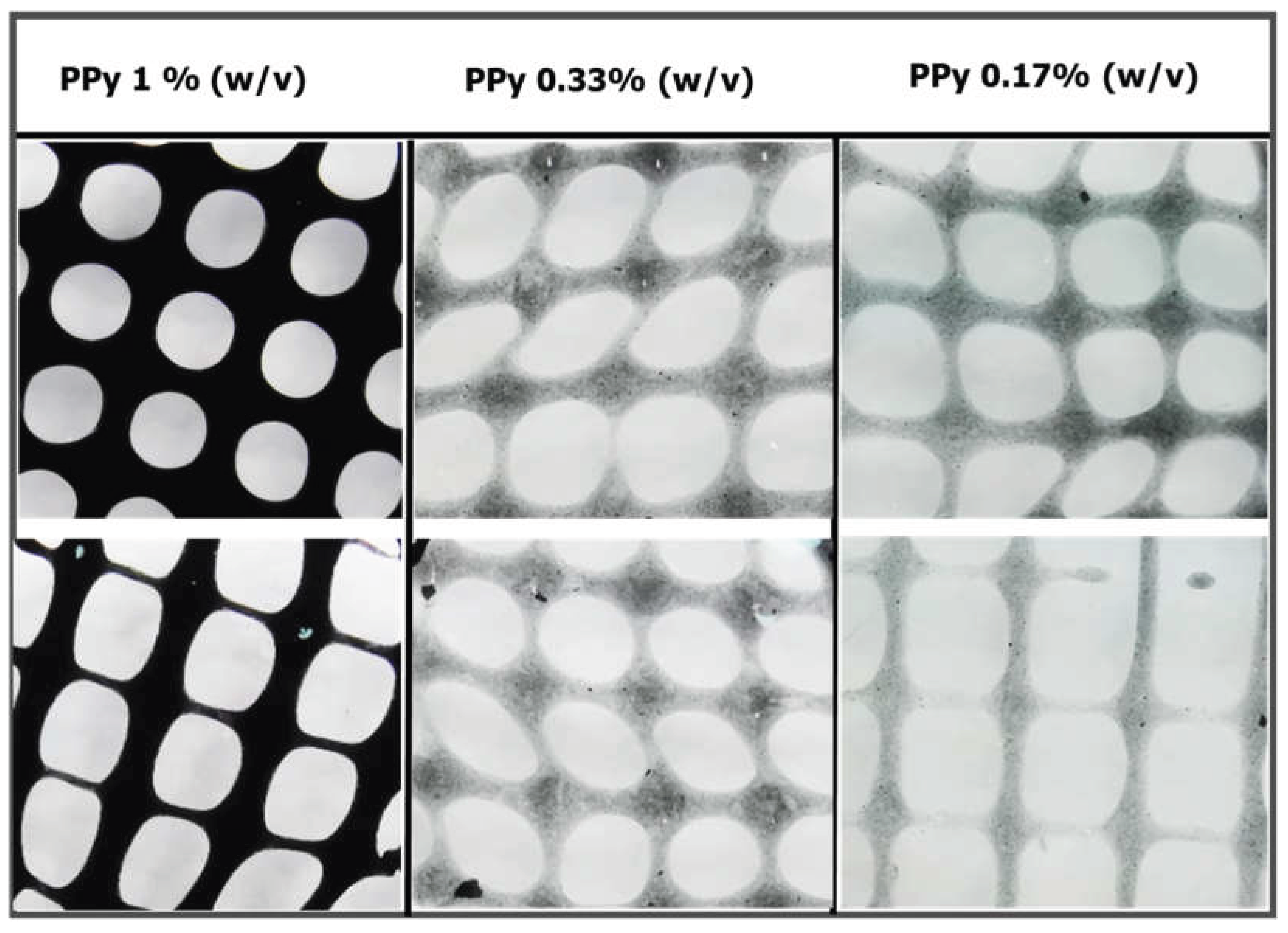

2.7.2. Alginate@polypyrrole Nanoparticles (alginate@PPy-NP) as Bioink

The possibility of blending PPy-NP into an alginate hydrogel as a bioink (alginate@PPy-NP) for 3D printing was explored. Different solutions of 3 ml (2% w/v) alginate containing PPy-NP at final concentrations of 1, 0.33, and 0.17% w/v, corresponding to solutions with PPy-NP/alginate ratios of 8.3, 16.7, and 50% w/w, respectively, were prepared. The primary crosslinking was performed by dropwise addition of 0.05 M CaCl2 to reach a final concentration of 0.01 M and was stirred overnight and subsequently used for 3D printing or further processed for rheological testing and electrical conductivity testing.

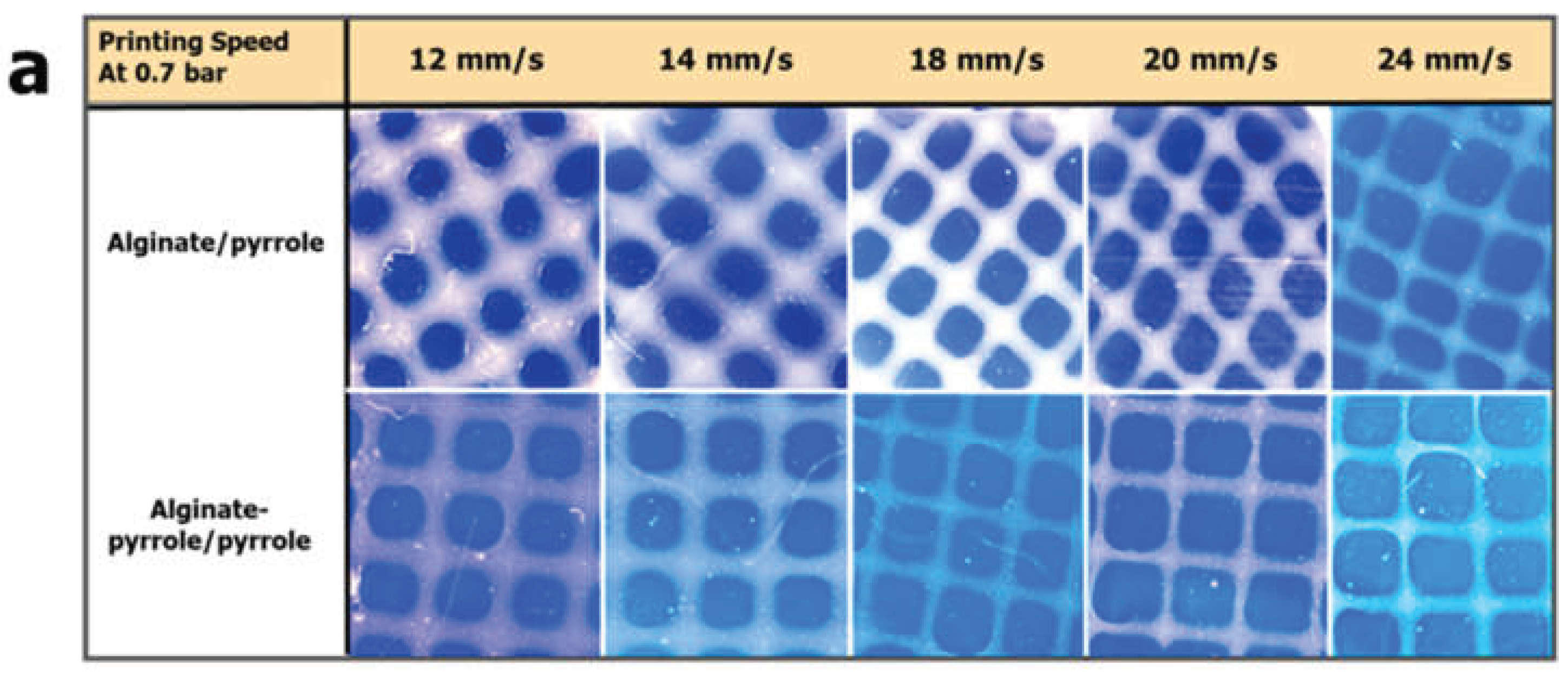

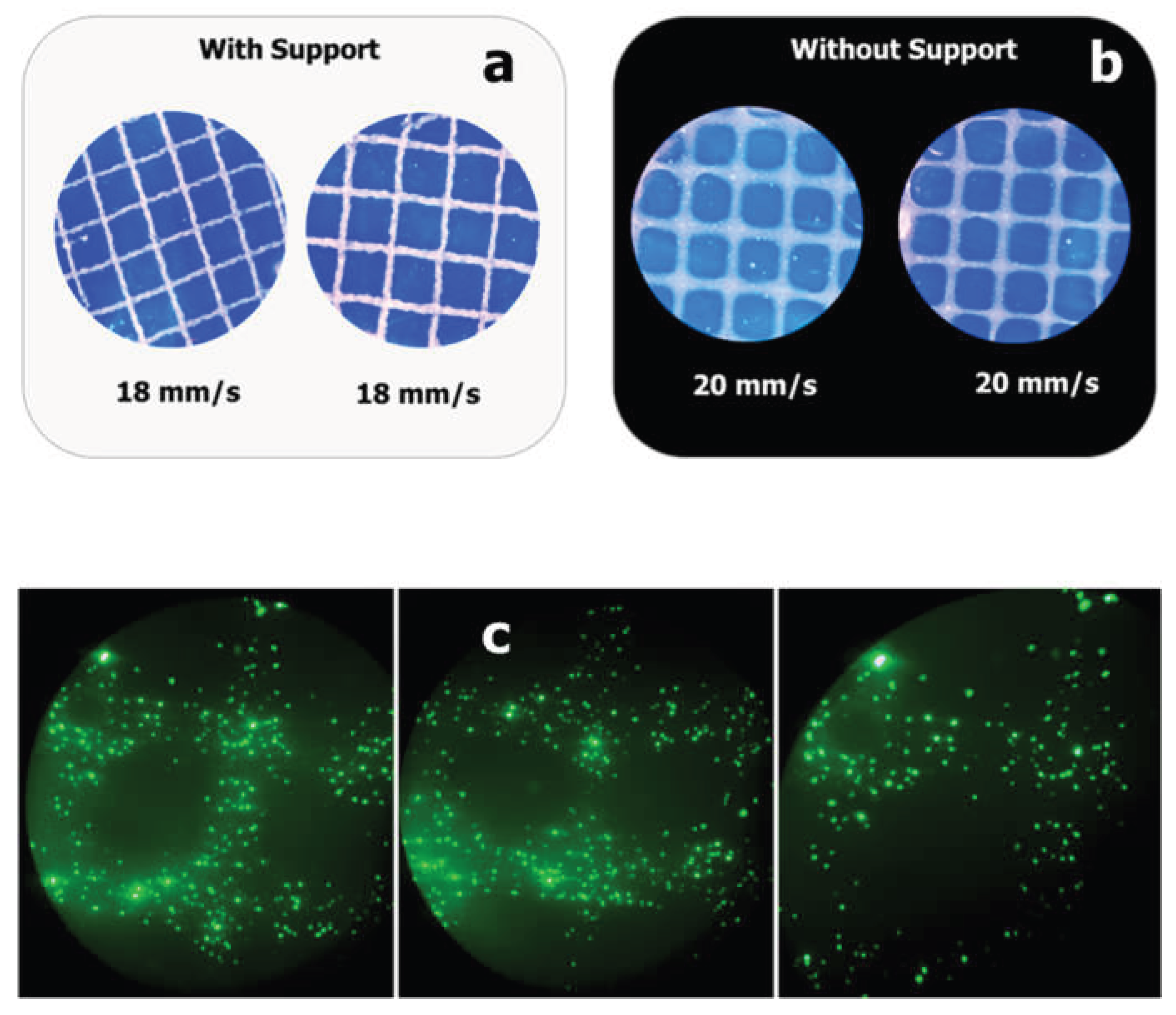

2.8. 3D Printing of Alginate-Pyrrole Conjugate and Alginate@polypyrrole Composites

Basic 3D models of the scaffold construct were designed and spliced using Perfectory RP and software supplied by the Envision TEC 3D bio-plotter. Using the VisualMachine BP interface software (V2.2; EnvisionTEC GmbH), the designs were printed using a 3D Bioplotter Manufacturer Series system (EnvisionTEC GmbH). Scaffolds were 11 mm × 11 × 2.5 mm with an inner strand distance of 2.25 mm and inner strand angles of 0° and 90°. The strands were dispensed layer by layer using pneumatic pressure in a piston-based system through 25-gauge blunt dispense needles (EFD Nordson, Switzerland). The printing parameters were optimized in terms of the printing speed and pressure in the range of 10-22 millimeter per second and 0.5-1.0 bar respectively.

Prior to bioprinting, as previously described [

19], the bioink was deposited into a sterilized 30 mL printer cylindrical cartridge sealed with a fitted plunger utilizing a Luer-to-Luer connector. The printer cartridge was subsequently sealed and centrifuged for 1 min at 150 g to eliminate any remaining air bubbles. A sterile 25-gauge needle tip was attached to the cartridge and a cap connecting the print head to the barrel was affixed. The barrel was placed in the low-temperature head of the bioprinter (EnvisionTEC 3D-bioplotter Developer Series, Germany), set to 25°C. The bioink solution was allowed to equilibrate to the printing head temperature for 30 min prior to bioprinting. The 3D printing was conducted by extrusion over the range of 0.5-0.8 bar and printing speed of 10-22 mm/s, followed by secondary crosslinking with 0.1 M CaCl

2. In addition, the possibility of printing using the freeform reversible embedding of suspended hydrogels (FRESH), as described by Hinton et al. [

18], was evaluated.

To eliminate the gelatin support bath, the bioprinted constructs were incubated for 1 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. The constructs were then washed and incubated for 10 min at 37°C in DMEM supplemented with 0.1 M CaCl2 to further crosslink the 3D-bioprinted constructs, after which the constructs were incubated in DMEM supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in a new 12-well plate.

2.8.1. Semi-Quantification of Printability

The printability of the alginate-polypyrrole inks to achieve square-shaped pores was quantified from light microscopy images using the ImageJ software. The printability of the bioink was determined according to the method described by Ouyang et al. [

29], based on the understanding of the circularity (C) of an enclosed area. The circularity of an enclosed area is defined as

Where L is the perimeter and A is the area.

The circles exhibit the highest circularity (

C = 1). The closer the value of C is to one, the closer the shape is to a circle. For a square shape, the circularity is

π/4 [

29]. Because the model designed in this study was square, the bioink printability (Pr) based on the square shape was defined according to the following equation [

29]

In this study, the printability factor (Pf) is defined as

In this context, three statuses of Pf are defined as follows: Pf < 1 corresponds to under-gelation and usually rounded pore corners because of the fusion of layers and swelling; Pf = 1 corresponds to proper gelation with ideal square-shaped pores; and Pf > 1 corresponds to over-gelation, causing shrinkage of the construct [

30].

2.9. Rheological Characterization

The Viscoelastic behavior of the alginate and alginate-pyrrole solutions and hydrogels was assessed using a stress-controlled advanced rheometer (AR 2000; TA Instruments). A 40 mm diameter 3°58 steel cone geometry with a truncation gap height of 104 μm was used. The storage modulus (G′), loss modulus (G″), and complex viscosity (|η∗|) were recorded as a function of time through oscillatory measurements in a frequency range of 0.1–10 Hz, and the strain was determined to be in the linear viscoelastic region. In addition, the apparent viscosities (Pa · s) of the hydrogel solutions were assessed at shear rates between 0.1 − 150 s−1. Compressibility was measured using a rheometer (TA Instruments, model AR 2000) operated in flat-plate mode with a 40 mm diameter in an increasing normal force.

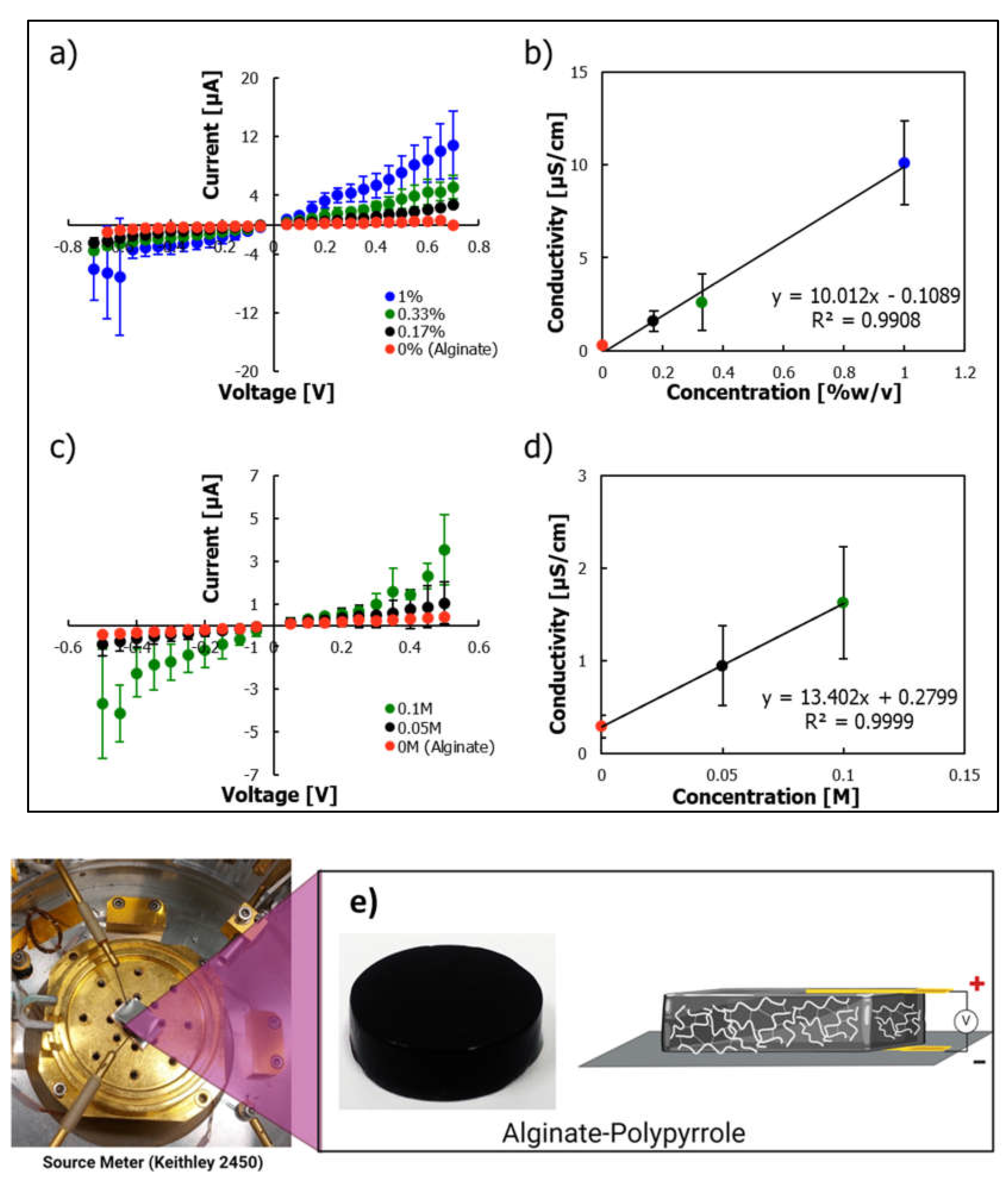

2.10. Electrical Conductivity Characterization

Electrical measurements were performed using a sandwich configuration. A partially crosslinked alginate, alginate-Py (later polymerized to alginate-PPy after crosslinking), and alginate@PPy-NP hydrogel were individually cast into a custom-made mold to fully crosslink overnight by adding a crosslinker (150 mM calcium ions). A hydrogel with a volume of 1 cm³ was placed on a stainless-steel plate (1 × 1 cm²), and a second stainless-steel plate was placed on top of the hydrogel. Prior to device assembly, the stainless steel plates underwent a thorough cleaning process involving sequential sonication in acetone, methanol, isopropyl alcohol (IPA), and deionized water (DDW) for 15 min each, followed by nitrogen drying.

The device was placed in a probe station (JANIS ST-500, USA) and tightly secured by applying pressure to the top probe. Current-voltage (I-V) measurements were conducted using a Keithley 2635 Source-Meter Unit, with data acquisition controlled by a custom MATLAB program. The measurements spanned a voltage range from -1 V to 1 V in 0.05 V increments. At least three devices were tested for each sample type, to ensure reproducibility.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

A two-way or one-way ANOVA, followed by a Tukey multiple comparisons test, was conducted using GraphPad Prism version 8.0.2 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA,

www.graphpad.com, accessed on 26 November 2024)

4. Discussion

In the category of conducting polymers, polypyrrole (PPy) is widely used because of its advantages such as low-cost preparation, excellent conductivity, and large surface area. PPy, a conductive polymer, facilitates the immobilization of various metallic nanoparticles on the surface of electrodes through π−π stacking, electrostatic interactions, or entrapment procedures [

37]. In this study, we synthesized an N-substituted pyrrole (aminopropyl pyrrole) and its covalent conjugation to alginate, which can be polymerized in situ into an alginate-polypyrrole (alginate-PPy) conjugate. In addition, polypyrrole nanoparticles (PPy-NPs) were chemically synthesized and blended with alginate to produce a stable conductive alginate polypyrrole composite (alginate@PPy-NP), which was used independently together with alginate-PPy as inks for extrusion-based 3D printing.

Spectroscopic analysis confirmed the successful incorporation of PPy into the alginate matrix via both

in situ polymerization and nanoparticle embedding. FTIR, mass spectrometry (

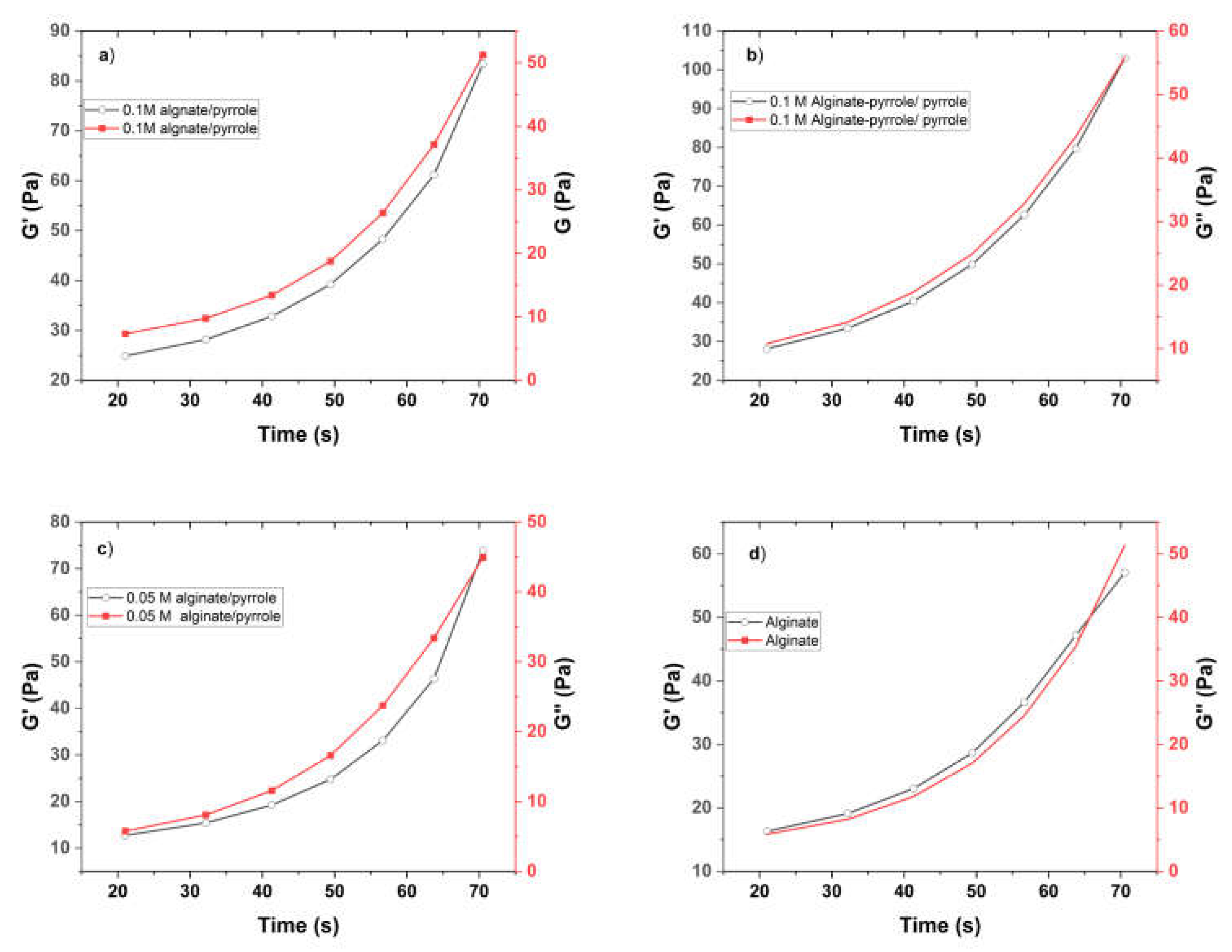

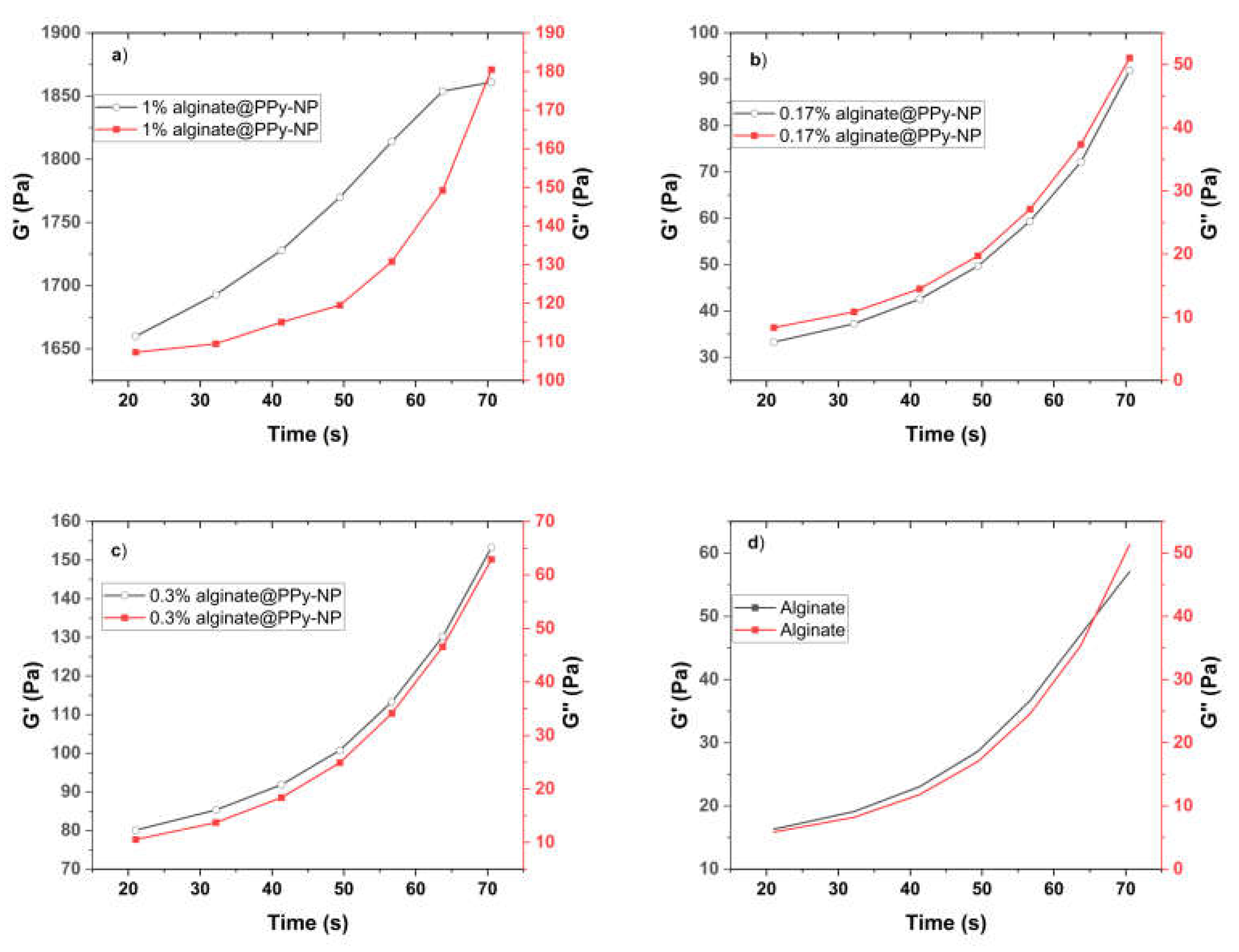

Supplementary Figure S2), and NMR confirmed the success of aminopropyl pyrrole synthesis, while X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) revealed characteristic binding energies for C–C, C–O, and N–H species, confirming the presence of polypyrrole and its interaction with the alginate backbone. Rheological measurements demonstrated that both the alginate-PPy and alginate@PPy-NP systems exhibited time-dependent increases in the storage modulus (G′) and reductions in the complex viscosity (|η*|), indicating progressive gelation (

Figure 5). The

in situ polymerized alginate-PPy system showed moderate improvements in viscoelasticity, whereas the alginate@PPy-NP system exhibited more substantial enhancements, particularly at 1% (w/v) PPy-NP. A higher G' indicates that the hydrogel exhibits greater elasticity and structural integrity, which is crucial for mechanical stability and resilience applications [

38,

39]. This characteristic is particularly beneficial in applications, such as 3D printing and tissue scaffolding, where mechanical stability and resilience are necessary to support printing fidelity, cellular activity, and tissue regeneration. [

40]. The ability of hydrogels to maintain their structural integrity under load is further emphasized by studies showing that higher G' correlates with increased gel strength and reduced water absorbency under pressure [

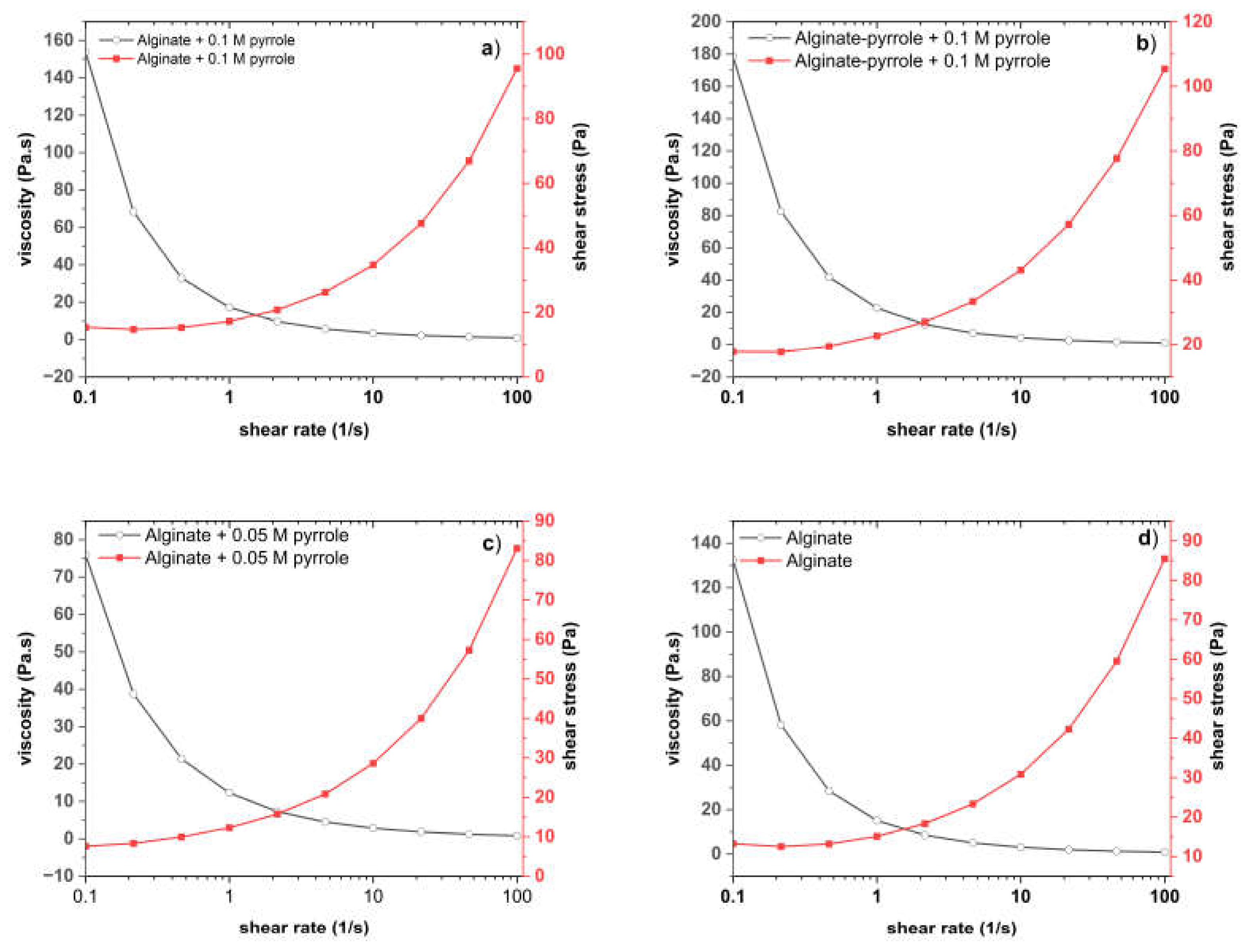

40]. This concentration-dependent behavior suggests that the nanoparticles acted as physical crosslinkers, promoting network densification and elastic recovery. Shear-thinning behavior was observed across all formulations, which was favorable for extrusion-based bioprinting.

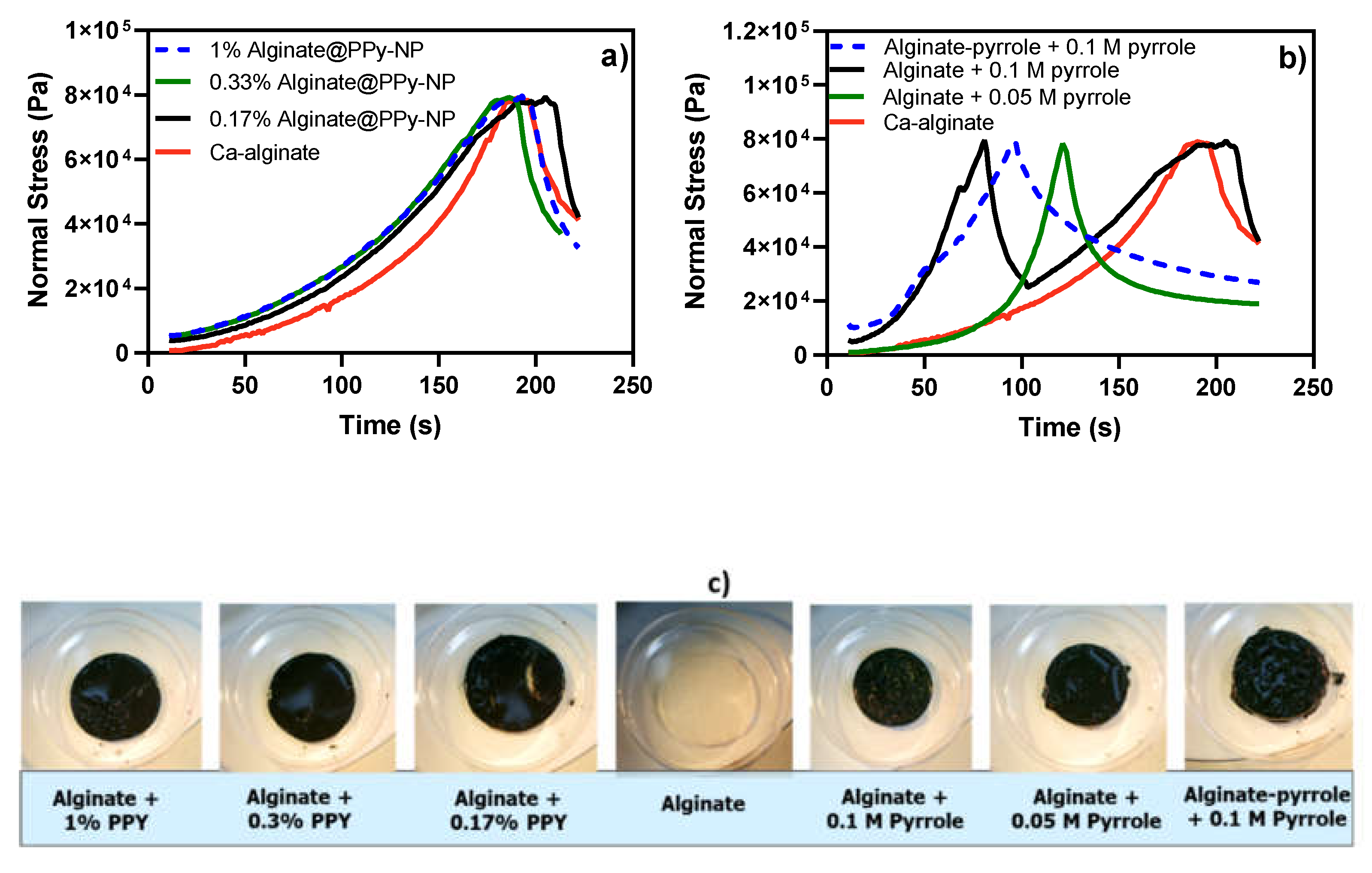

Mechanical analysis using compressibility tests further supported these rheological findings (

Figure 7). The alginate@PPy-NP hydrogels (

Figure 7a) showed a clear concentration-dependent increase in compressive strength and deformation resistance, with the 1% NP variant achieving the highest mechanical robustness. In contrast, alginate-PPy hydrogels displayed symmetric stress–strain profiles, indicative of homogenous, yet brittle networks. Notably, the deformation pattern of alginate@PPy-NP extended beyond 180 s, whereas alginate-PPy (

Figure 7b) exhibited earlier yielding, reflecting differences in the network architecture. A higher cross-linking density generally leads to an increased compressive modulus, which enhances the ability of the hydrogel to resist deformation under the applied loads. As shown in

Figure 7, the compressive stress for both types of alginate-PPy (or alginate@PPy-NP) was 80 kPa, with a permanent deformation setting at different times. Alginate@PPy-NP resulted in a more elastic composite hydrogel than the composite alginate-polypyrrole. These results suggest potential nanoparticle-mediated reinforcement of the hydrogels, consistent with prior reports of enhanced compressive performance in nanocomposite hydrogels [

38,

41]. Conversely, the alginate-PPy system (

Figure 7b) shows moderate improvements in mechanical integrity, with a single symmetric stress–strain peak that shifts slightly with increasing pyrrole content. Alginate-PPy exhibited a sharp deformation pattern over a relatively short time (less than 100 s), whereas alginate@PPy-NP exhibited a curve-like deformation behavior beyond 180 s. This is similar to the report by Wright et al. [

25], who reported that

in situ generated polypyrrole resulted in a brittle hydrogel film at certain concentrations.

Conductive hydrogels can be engineered by incorporating conductive materials such as conductive polymers or nanoparticles into the hydrogel matrix. In this study, we demonstrated the possibility of improving the electrical conductivity of hydrogels through covalent addition of a conductive polypyrrole polymer. Electrical characterization showed that the integration of PPy imparted conductivity to the hydrogels, with a clear trend of increasing conductivity with increasing PPy content (

Figure 8). Different oxidants, such as hydrogen peroxide, ferric chloride, and ammonium persulfate (APS), have been used to synthesize polypyrrole from its monomer precursor. Ferric chloride and APS gave a fast reaction rate (

Figure S4), and because ferric ions, as multivalent cations, can interfere with alginate crosslinking, APS was selected as the preferred oxidant to prepare polypyrrole [

42] due of its compatibility with alginate crosslinking, avoiding interference from Fe³⁺ ions. Polypyrrole-incorporated alginate displayed electrical conductivity that increased with increasing polypyrrole content. The observed conductivity shown in

Figure 7b falls within the range of the conductivity observed in polysaccharide-based hydrogels. Guo et al. [

43] noted that the conductivity of pure chitosan was approximately 3.13 x 10

-8 S/cm, which increased to 2.97 x 10

-5 S/cm with the addition of 10% aniline as an intrinsically conducting unit [

43]. Crosslinked alginate gels conduct electricity via movement of mobile ions within the gel, which is enhanced by the introduction of a polypyrrole backbone with conjugated π-electrons. These electroconductive features render the material suitable for electrically active tissue-engineering applications.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) confirmed the nanoscale morphology of the chemically synthesized conductive PPy-NPs, revealing uniform spherical particles (

Figure 12a) with rough surfaces, stable integration within the alginate matrix, and elemental distribution (

Figure 12b). The influence of these nanoparticles is evident in extrusion-based 3D printing and enhanced mechanical properties. The alginate@PPy-NP constructs, particularly at 1% loading, exhibited high shape fidelity with well-defined pores and minimal filament spreading (

Figure 13). Lower concentrations resulted in a poorer resolution and structural collapse. Printability was further optimized by primary ionic crosslinking with 10 mM Ca²⁺, which improved ink viscosity and extrusion stability. Additionally, printing within a support bath preserved the grid geometry, even at higher speeds, similar to unsupported printing. This demonstrates the robustness of printability amenable to different 3D printing applications in tissue engineering.

Putting all together, the integration of polypyrrole into alginate via covalent polymerization or nanoparticle dispersion significantly enhanced the physicochemical and functional properties of the resulting electrically conductive hydrogels. These modifications improve the rheological behavior, mechanical integrity, electrical conductivity, and print fidelity, all of which are critical parameters for bioprinting applications. The ability to tailor these properties through pyrrole concentration and formulation method makes these bioinks promising candidates for extrusion-based tissue engineering, particularly in scenarios requiring both mechanical robustness and electrical activity, such as in neural or bone tissue regeneration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.P. and R.S.M.; methodology, A.A.P., O.K, H.M, AKB.; investigation, A.A.P, H.M., A.K.B., O.K.; resources, R.S.M., N.A., S.C..; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.P.; writing—review and editing, A.A.P., H.M, O.K., A.K.B., R.S.M., N.A., S.C.; visualization, A.A.P., H.M.; supervision, R.S.M., N.A., S.C..; project administration, R.S.M., N.A., S.C.; funding acquisition, R.S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.