1. Introduction

The identification of influential nodes [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6] in complex networks [

7,

8,

9] remains a persistent challenge, with critical applications spanning targeted advertising on social platforms, source localization in rumor propagation, and the selection of high-impact researchers.

In the context of scientific influence assessment, the

H-index [

10] has emerged as a widely adopted metric to quantify both the quality and productivity of research output. Originally proposed by J. E. Hirsch to characterize individual scientific contributions, the

H-index has since been extended to evaluate academic institutions and journals [

11]. By integrating measures of publication quality (impact factor) and quantity (publication count), it addresses the limitations of traditional metrics that prioritize only one dimension.

Over the past two decades,

H-index has been attracting the attention of many researchers from the field of scientometrics [

12], who proposed various improvements in different perspectives [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. These advancements fall into three primary categories:

(I).Normalization and Averaging: Methods such as normalizing the H-index by the number of authors [

14], by the publication year [

15], by the disciplinary field [

16], as well as averaging with citation counts[

17] or geometric mean [

18].

(II).Incorporation of Additional Information: Approaches that integrate auxiliary data, including the author’s position in bylines [

19], the shape of citing functions [

20], subdomain distributions within a scientist’s citation profile[

21], the collaboration distance between citing and cited authors [

22], excess citations beyond

citations for papers [

23], and the the inclusion of uncited papers [

24].

(III).Temporal Evolution Analysis: Studies examining the H-index’s trajectory over a researcher’s career, such as predictive models via regression analysis [

25,

26] and time window evaluations [

27].

These improvements, though valuable, are closely tied to the intrinsic properties of papers and authors, making their generalization to broader complex networks challenging.

Notably, the

H-index has also captured the interest of scholars in complex networks since Lü

et al. [

28] revealed the

H-index relationship to degree and coreness. Specifically, Lü

et al. [

28] defined an

H-operator on a group of numbers via

H-index. They proved that the coreness – a centrality measure introduced by Kitsak

et al. – is the limit of the iteration of the

H-operator. This seminal work [

28] has sparked widespread attention. On the one hand, it has been extended to directed networks [

29] and weighted networks [

30]. On the other hand,, it has reinvigorated interest in coreness, a computationally efficient centrality metric. Despite its utility, coreness has inherent limitations, such as limited discrimination power and coarse-grained resolution. To address these, several refinements have been proposed, including: mixed degree [

31], shortest distance-based coreness [

32], community-based coreness [

33], coreness without redundant links [

34], and two-step coreness [

35].

This paper investigates the limitations of the H-index in capturing the influence of weak nodes – nodes with small degrees but high-degree neighbors. Our analysis is driven by the observation that the H-index, which counts the number of neighbors with degree, underestimates the influence of weak nodes. For example, consider two nodes: Node u has neighbors with degrees , yielding . Node v has neighbors with degrees , also yielding . Although node v is a weak node (low degree but surrounded by high-degree neighbors), it is more influential in information propagation than node v. This illustrates a critical shortcoming of the H-index: it assigns equal influence to nodes with structurally distinct neighbor sets.

The k-core decomposition, derived by iteratively applying the H-index to a node’s neighbors, exacerbates this bias. Weak nodes are systematically underestimated in k-core analyses due to their low intrinsic degrees, despite their high-degree neighbors.

To estimate the influence of weak nodes during information spreading, we propose a new centrality, -index, which is the maximum number of neighbors with at least times the same number of degree. This formulation emphasizes relative neighbor quality (via ) over absolute degree thresholds, enabling nuanced influence quantification.

Building on the -index, we define g-core, a hierarchical decomposition that partitions the network based on -index values. This method better captures the influence of weak nodes compared to traditional k-core.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides theoretical background on the

H-index, k-core, and collective influence centrality.

Section 3 introduces

-index,

g-core and local

g-core.

Section 4 presents experiments validating the superiority of

-index and

g-core.

Section 5 discusses future research directions.

2. Classical Centrality

2.1. Notations

Let denote an undirected symmetric network, where V and E represent the set of nodes and the set of edges in G, respectively. The adjacency matrix encodes connectivity, where is the number of nodes in G, and if nodes u and v are connected, i.e., , and otherwise. The neighborhood of a node v is defined as the set of nodes directly connected to v. For a node v, let denote its degree, i.e., .

2.2. H-index Centrality

Definition 1.

Let be a finite non-empty set of positive real numbers. Define the subset as:

The H-operator, denoted , is the maximum value y such that .

Definition 2.

Let v be a node in a graph G, and let denote its neighborhood. The H-index of v, denoted , is defined as:

where is the degree of node u.

2.3. Coreness Centrality

Coreness centrality is a network topological measure derived from k-core decomposition. It evaluates a node’s importance based on its position within the hierarchical core structure of a network. Nodes with higher coreness values occupy denser, more central regions of the network, playing critical roles in maintaining global connectivity and influence.

The k-core is obtained through iterative degree-based pruning:

(1). Start with the original graph .

(2). Iteratively remove all nodes with degree less than k along with their incident edges.

(3). Repeat until no nodes with degree less than k remain.

The resulting subgraph is the k-core. A node v is assigned a coreness if it belongs to the k-core but not the -core. This hierarchical decomposition ensures that nodes in higher k-cores are more deeply embedded within the network’s core structure.

2.4. Closeness Centrality

Closeness centrality measures a node’s centrality based on its average distance to all other nodes in the network. It quantifies how quickly a node can reach others, reflecting its efficiency in spreading information or influence. Nodes with high closeness centrality are "close" to others, meaning they have short average path lengths to all nodes.

The closeness centrality

of a node

v in a connected graph

with

n nodes is defined as:

where

is the shortest path length between nodes

u and

v, and

normalizes the measure to account for the number of other nodes in the network.

2.5. Collective Influence Centrality

Collective Influence (CI) is a method developed by Morone and Makse [

36] for identifying highly influential nodes in complex networks. CI quantifies a node’s influence by measuring the extent of damage inflicted on the network’s giant connected component upon the node’s removal. The formal definition of CI is given by:

where

represents the degree of node

i,

denotes the set of nodes at a

l-hop distance from node

u, and

is the degree of node

j.

2.6. Betweenness Centrality

Betweenness centrality is a measure of a node’s centrality in a network based on the extent to which it lies on the shortest paths between pairs of other nodes. It quantifies a node’s role as a "bridge" or intermediary in facilitating communication, information flow, or interactions across the network. Nodes with high betweenness centrality are critical for maintaining connectivity and controlling the flow of resources, as their removal can significantly disrupt network interactions.

The betweenness centrality

of a node

u in a graph

with

n nodes is defined as:

where

is the total number of shortest paths from node

s to node

t, and

is the number of those shortest paths that pass through node

u.

3. -Index, -Core and Local -Core on Symmetric Networks

Definition 3. Let be a finite set of positive real numbers, be a real number, and . An -operator is defined as the maximum value y such that .

Definition 4.

Given a node with neighbors , the -index of v, denoted , is defined as:

where denotes the degree of node u.

Definition 5.

Let be a simple undirected symmetric network. For any node , the -sequence of v, denoted , is recursively defined as:

By this definition, the

-index corresponds to the cardinality of the set

. This yields the following inequality:

From the definition of the

-index, it is evident that the

H-index is a specific instance of the

-index. Specifically, when

, the

H-index coincides with the

-index, i.e.,

. Furthermore, when

, the

-sequence

converges to its coreness

, as established by Lü et al. [

28].

Theorem 1.

For any node in the network , if , then the following equation holds

where denotes the limit of the -sequence for node v.

Proof. We prove that the -sequence is strictly monotonic decreasing whenever .

(1)

Base Case (): By the definition of the

-sequence,

Since

(the initial degree of node

u), we have:

This implies , establishing the base case.

(2)

Inductive Step: Assume that for some

,

. By the definition of the

-sequence:

Since

for all

(by the inductive hypothesis), and

is a monotonic decreasing function, it follows that:

Thus, the inequality holds for , completing the inductive step.

(3) Conclusion: By induction, the -sequence is strictly monotonic decreasing for all whenever .

(4)

Convergence to Zero: Since the sequence

is strictly decreasing and bounded below by 0 (as shown in equation (

1)), the Monotone Convergence Theorem ensures:

Thus, as required. □

|

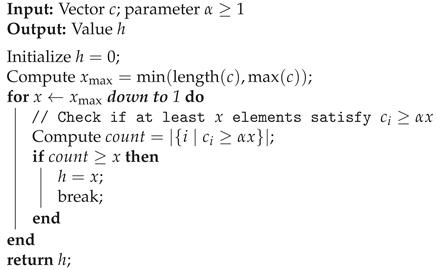

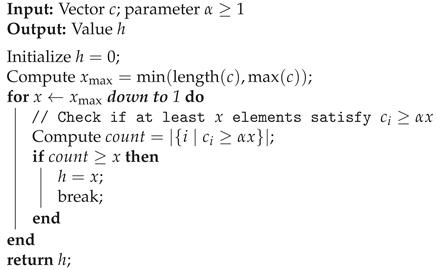

Algorithm 1:H_alpha_Operator |

|

|

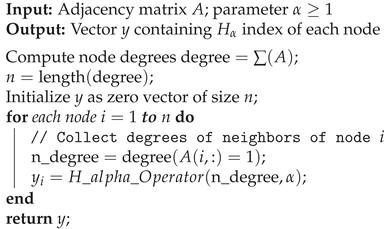

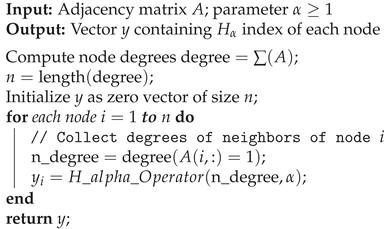

Algorithm 2:H_alpha _Index |

|

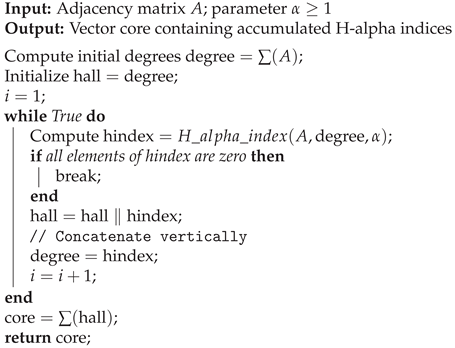

The -operator and - index have been implemented and reference them as Algorithms 1 and 2. The -operator computes a thresholded value h for a given vector c and a parameter . It iteratively evaluates the maximum integer x such that at least x elements in c satisfy the condition . This process identifies a critical point where the density of values in c relative to -scaled thresholds is maximized. The algorithm terminates once the condition is met or exhausts the search range, ensuring computational efficiency by limiting the search to . The output h quantifies the structural resilience or dominance of values in c under the specified -weighted constraint, applicable in scenarios requiring threshold-based analysis of data distributions.

The -index algorithm evaluates the influence of a node in a network by leveraging its neighborhood structure. Given an adjacency matrix A and parameter , it first extracts node degrees degree from A. For each node i, it computes the degrees of its immediate neighbors n_degree and applies the H-alpha operator to this subset. The resulting represents the H-alpha index of node i, reflecting the interplay between the node’s connectivity and the -scaled thresholding of its neighbors’ degrees. This metric provides insights into how local network properties propagate globally, enabling the identification of nodes whose influence is contingent on both their direct connections and the collective behavior of their neighbors.

Classically, the

H-sequence

converges to its coreness

[

28]. However, when extended to the

-index framework, the iterative sequence converges to zero (See Theorem 1), presenting challenges in generalizing the k-core concept. To address this, we propose accumulating the iterative values during the convergence process, as later termination at zero indicates stronger coreness. This leads to the following definition of

g-core, where the summation of values quantifies the structural centrality.

Definition 6.

The g-core of a node v is defined as

Furthermore, to incorporate neighborhood influence, we introduce the local g-core, which integrates the coreness metrics of adjacent nodes, enabling localized structural analysis.

Definition 7.

Local g-core of a node v is defined as

where is a parameter compromising between the node v and its neighbors.

|

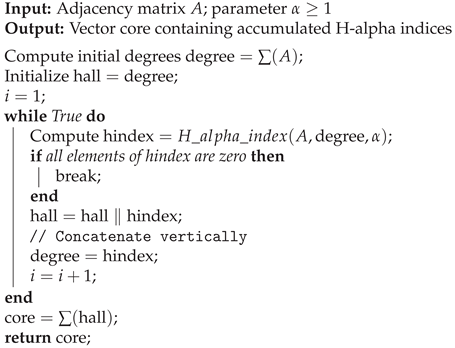

Algorithm 3:g-core Calculation |

|

The g-core has been implemented in Algorithm 3. The g-core algorithm iteratively refines the structural properties of a network through successive applications of the H-alpha index. Starting with initial node degrees, it computes the H-alpha index vector hindex and updates the degree vector for the next iteration. This process continues until all elements in hindex become zero, signifying that the network’s structural constraints under -scaled thresholds are fully exhausted. The algorithm accumulates intermediate results into a matrix hall, and the final output core is obtained by summing all rows of hall. This cumulative measure captures the network’s progressive degradation under iterative -based filtering, offering a quantitative framework to assess robustness or vulnerability in complex systems.

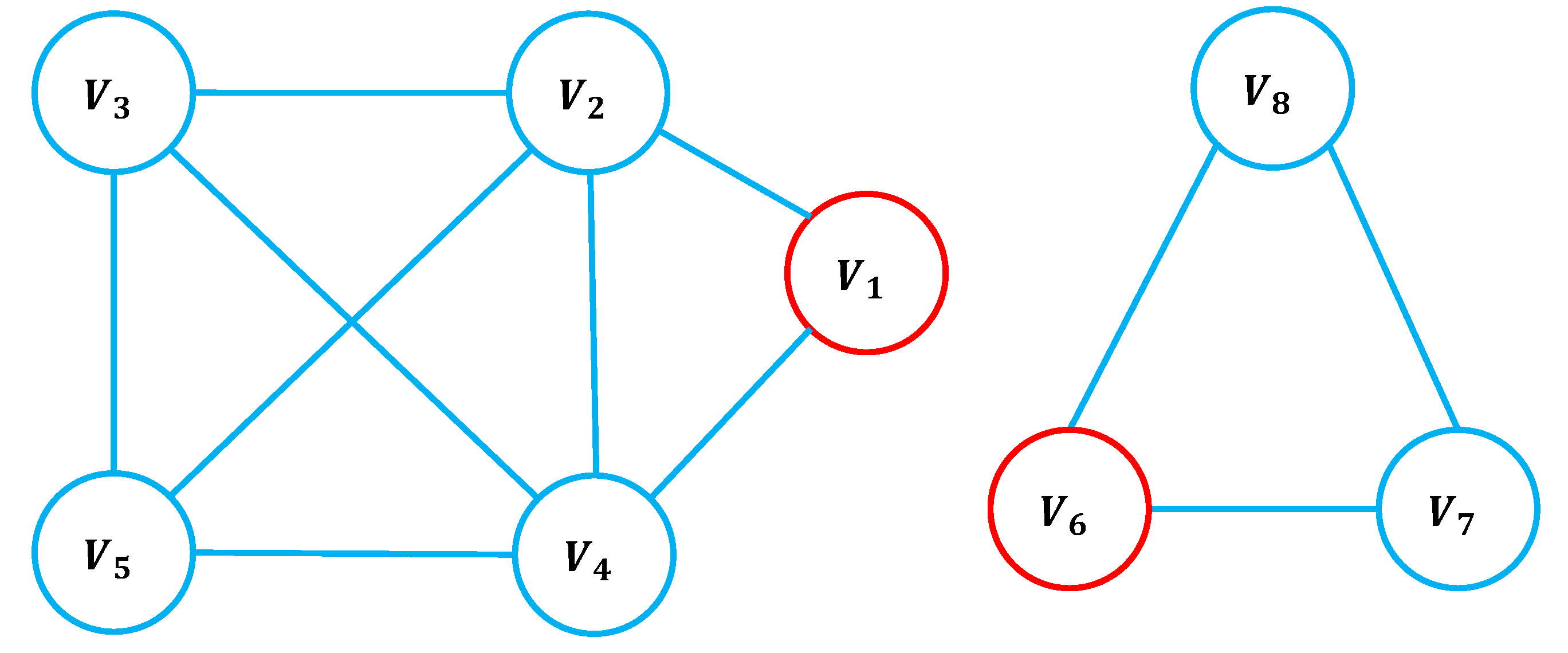

Table 1 presents the

-sequence and

g-core values for the nodes in

Figure 1. Node

in

Figure 1 has neighbors with degrees

, whereas node

has neighbors with degrees

. Despite node

being structurally more influential than node

, their

H-indices are equal. This highlights a limitation of the

H-index and traditional coreness metrics: they fail to distinguish the true influence of nodes based on neighborhood diversity. In contrast, the

g-core and

-index values of

are strictly greater than those of

, demonstrating their capacity to more effectively capture the structural significance of nodes with heterogeneous neighborhood properties.

Table 1.

The H-index, coreness, -sequence and g-core, where .

Table 1.

The H-index, coreness, -sequence and g-core, where .

| Node |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

g-core |

5 |

7 |

6 |

7 |

6 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

|

H-index |

2 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

| coreness |

2 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

Figure 1.

Example network illustrating the -index and g-core. The g-core values for nodes and are 5 and 3, respectively.

Figure 1.

Example network illustrating the -index and g-core. The g-core values for nodes and are 5 and 3, respectively.

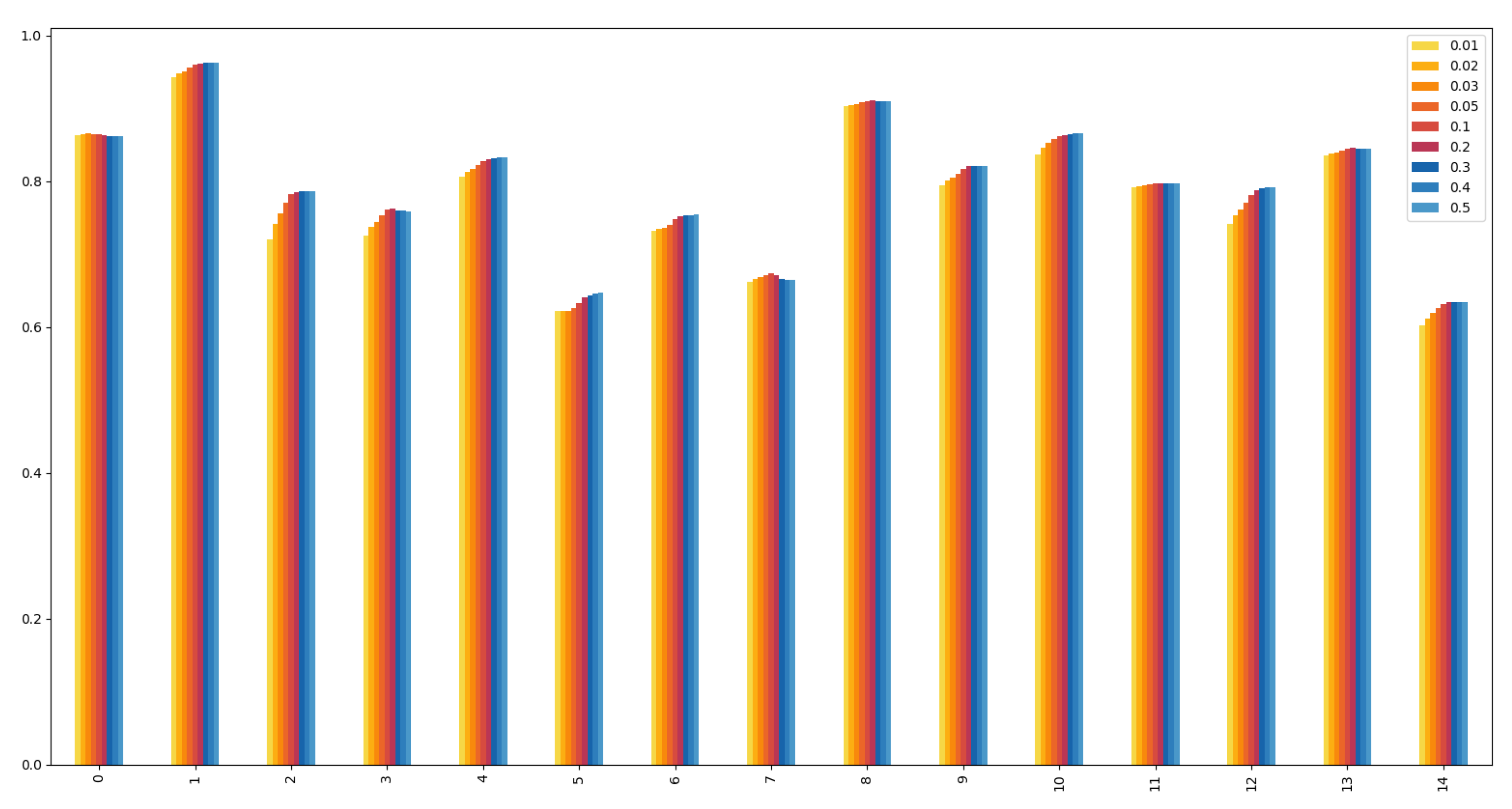

Figure 2.

Kendall’s tau coefficients of local

g-core on the fifteen real networks when

and

. For each network, the infected probability is set as

The fifteen networks from left to right are in the same order as the networks in

Table 2.

Figure 2.

Kendall’s tau coefficients of local

g-core on the fifteen real networks when

and

. For each network, the infected probability is set as

The fifteen networks from left to right are in the same order as the networks in

Table 2.

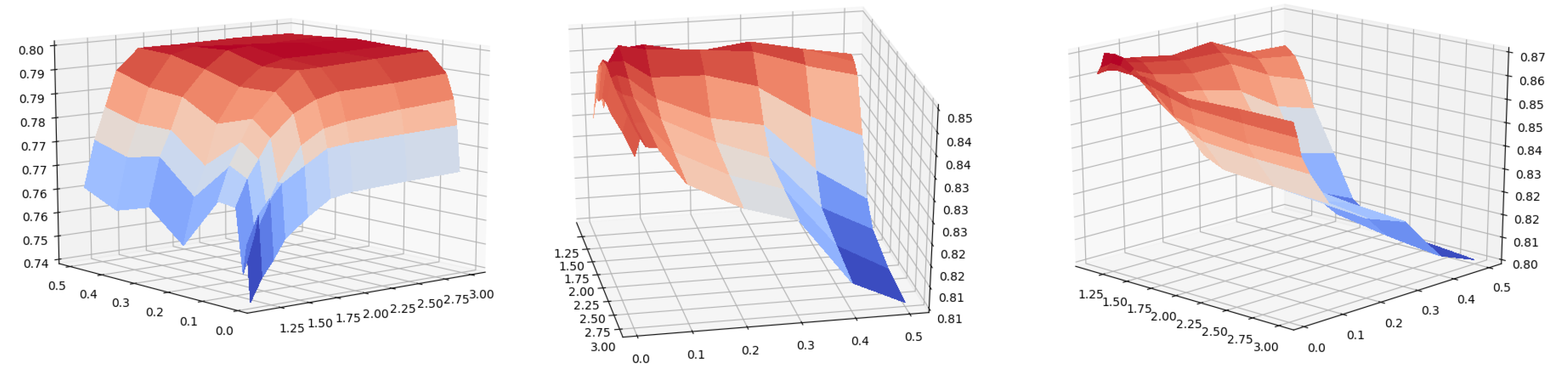

Figure 3.

Kendall’s tau coefficients of local g-core on the fifteen real networks when and . For each network, the infected probability is set as

Figure 3.

Kendall’s tau coefficients of local g-core on the fifteen real networks when and . For each network, the infected probability is set as

Figure 4.

Kendall’s tau coefficients of local g-core on the network Celegns when and . From left to right, the infected probability is set as .

Figure 4.

Kendall’s tau coefficients of local g-core on the network Celegns when and . From left to right, the infected probability is set as .

Table 2.

Basic topological features of nine real networks. and denote the number of nodes and the number the links, respectively. <k> and <d> represent the average degree and the average shortest distance, respectively. C is the clustering coefficient, and r is the assortative coefficient.

Table 2.

Basic topological features of nine real networks. and denote the number of nodes and the number the links, respectively. <k> and <d> represent the average degree and the average shortest distance, respectively. C is the clustering coefficient, and r is the assortative coefficient.

| Networks |

|

|

<k> |

<d> |

C |

r |

| Celegans |

297 |

2148 |

14.46 |

2.46 |

0.308 |

-0.163 |

| USAir |

332 |

2126 |

12.81 |

2.74 |

0.749 |

-0.208 |

| SmaGr |

379 |

914 |

4.82 |

6.04 |

0.798 |

-0.082 |

| Metabolic |

453 |

2025 |

8.94 |

2.66 |

0.646 |

-0.226 |

| SciMet |

1059 |

914 |

4.82 |

6.04 |

0.798 |

-0.082 |

| Email |

1133 |

5441 |

9.62 |

3.60 |

0.254 |

0.078 |

| Moreno |

1773 |

9131 |

10.30 |

3.38 |

0.721 |

-0.049 |

| NS |

1589 |

2742 |

3.451 |

7.14 |

0.80 |

-0.082 |

| Yeast |

2375 |

11693 |

9.85 |

5.09 |

0.388 |

0.454 |

| Kohonen |

4469 |

12718 |

5.69 |

3.67 |

0.211 |

-0.121 |

| Router |

5022 |

6258 |

2.49 |

6.45 |

0.033 |

-0.138 |

| PGP |

10680 |

24316 |

4.55 |

7.48 |

0.266 |

0.238 |

| Sex |

15810 |

38540 |

4.88 |

5.79 |

0.000 |

-0.115 |

| Condmat |

27519 |

116181 |

8.44 |

5.76 |

0.655 |

0.166 |

| EmailEnron |

36692 |

183831 |

10.02 |

3.24 |

0.497 |

-0.111 |

Table 3.

Kendall’s tau coefficients comparing nine centralities. For each network, the infection probability is set as , with parameters and . The maximum value in each row is highlighted in boldface to indicate the best performance. Abbreviations: CN (coreness), CC (closeness), BT (betweenness), CI (collective influence), -index (), GC (g-core), and LGC (local g-core).

Table 3.

Kendall’s tau coefficients comparing nine centralities. For each network, the infection probability is set as , with parameters and . The maximum value in each row is highlighted in boldface to indicate the best performance. Abbreviations: CN (coreness), CC (closeness), BT (betweenness), CI (collective influence), -index (), GC (g-core), and LGC (local g-core).

| Networks |

Degree |

H-index |

CN |

CC |

BT |

CI |

|

GC |

LGC |

| Celegans |

0.82 |

0.85 |

0.81 |

0.59 |

0.64 |

0.84 |

0.85 |

0.86 |

0.86 |

| Email |

0.88 |

0.91 |

0.88 |

0.78 |

0.68 |

0.91 |

0.91 |

0.93 |

0.96 |

| Kohonen |

0.64 |

0.66 |

0.67 |

0.73 |

0.51 |

0.69 |

0.67 |

0.68 |

0.79 |

| Metabolic |

0.65 |

0.69 |

0.71 |

0.55 |

0.45 |

0.70 |

0.69 |

0.72 |

0.76 |

| Moreno |

0.68 |

0.71 |

0.71 |

0.76 |

0.55 |

0.81 |

0.74 |

0.80 |

0.83 |

| NS |

0.46 |

0.48 |

0.44 |

0.40 |

0.30 |

0.64 |

0.53 |

0.62 |

0.64 |

| PGP |

0.45 |

0.47 |

0.47 |

0.68 |

0.30 |

0.55 |

0.50 |

0.73 |

0.75 |

| Router |

0.33 |

0.31 |

0.32 |

0.61 |

0.32 |

0.38 |

0.33 |

0.66 |

0.67 |

| SciMet |

0.84 |

0.88 |

0.87 |

0.79 |

0.66 |

0.85 |

0.88 |

0.90 |

0.91 |

| SmaGr |

0.73 |

0.76 |

0.76 |

0.66 |

0.60 |

0.78 |

0.77 |

0.78 |

0.82 |

| USAir |

0.75 |

0.78 |

0.78 |

0.78 |

0.57 |

0.80 |

0.79 |

0.83 |

0.86 |

| Yeast |

0.66 |

0.69 |

0.69 |

0.66 |

0.37 |

0.76 |

0.70 |

0.79 |

0.80 |

| Sex |

0.52 |

0.57 |

0.59 |

0.74 |

0.45 |

0.60 |

0.61 |

0.72 |

0.79 |

| Condmat |

0.63 |

0.68 |

0.67 |

0.73 |

0.37 |

0.79 |

0.71 |

0.84 |

0.85 |

| EmailEnron |

0.49 |

0.50 |

0.50 |

0.60 |

0.43 |

0.58 |

0.53 |

0.58 |

0.63 |

Table 4.

Imprecision values comparing nine centralities. For each network, the infection probability is set as , with parameters and . The maximum value in each row is highlighted in boldface to indicate the best performance. Abbreviations: CN (coreness), CC (closeness), BT (betweenness), CI (collective influence), -index (), GC (g-core), and LGC (local g-core).

Table 4.

Imprecision values comparing nine centralities. For each network, the infection probability is set as , with parameters and . The maximum value in each row is highlighted in boldface to indicate the best performance. Abbreviations: CN (coreness), CC (closeness), BT (betweenness), CI (collective influence), -index (), GC (g-core), and LGC (local g-core).

| Networks |

Degree |

H-index |

CN |

CC |

BT |

CI |

|

GC |

LGC |

| Celegans |

0.0103 |

0.0119 |

0.1508 |

0.0470 |

0.0255 |

0.0103 |

0.0161 |

0.0100 |

0.0032 |

| Email |

0.0048 |

0.0050 |

0.0301 |

0.0198 |

0.0393 |

0.0046 |

0.0081 |

0.0023 |

0.0004 |

| Kohonen |

0.1558 |

0.1376 |

0.1365 |

0.1648 |

0.2603 |

0.1025 |

0.1308 |

0.1204 |

0.0795 |

| Metabolic |

0.0556 |

0.0164 |

0.0268 |

0.0370 |

0.1995 |

0.0338 |

0.0158 |

0.0126 |

0.0187 |

| Moreno |

0.0289 |

0.0112 |

0.0160 |

0.0385 |

0.1748 |

0.0214 |

0.0140 |

0.0094 |

0.0099 |

| NS |

0.1597 |

0.2134 |

0.2477 |

0.2068 |

0.2174 |

0.0955 |

0.2001 |

0.1717 |

0.1404 |

| PGP |

0.1268 |

0.0911 |

0.1157 |

0.1866 |

0.5298 |

0.0427 |

0.0861 |

0.0302 |

0.0316 |

| Router |

0.1385 |

0.1330 |

0.1304 |

0.1379 |

0.1957 |

0.0650 |

0.1255 |

0.0710 |

0.0555 |

| SciMet |

0.0248 |

0.0086 |

0.0310 |

0.0835 |

0.1044 |

0.0210 |

0.0110 |

0.0067 |

0.0059 |

| SmaGr |

0.0330 |

0.0100 |

0.0434 |

0.1020 |

0.0988 |

0.0221 |

0.0220 |

0.0148 |

0.0141 |

| USAir |

0.0062 |

0.0057 |

0.0063 |

0.0218 |

0.1875 |

0.0062 |

0.0057 |

0.0027 |

0.0027 |

| Yeast |

0.0825 |

0.0779 |

0.0858 |

0.3466 |

0.6353 |

0.0448 |

0.0768 |

0.0026 |

0.0090 |

| Sex |

0.1363 |

0.0772 |

0.0494 |

0.0772 |

0.2434 |

0.0428 |

0.0714 |

0.0267 |

0.0243 |

| Condmat |

0.0730 |

0.0254 |

0.0802 |

0.0744 |

0.2735 |

0.0253 |

0.0214 |

0.0142 |

0.0100 |

| EmailEnron |

0.0502 |

0.0254 |

0.0204 |

0.0492 |

0.2551 |

0.0245 |

0.0238 |

0.0196 |

0.0154 |